User login

When is it safe to forego a CT in kids with head trauma?

Use these newly derived and validated clinical prediction rules to decide which kids need a CT scan after head injury.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An anxious mother rushes into your office carrying her 22-month-old son, who fell and hit his head an hour ago. The child has an egg-sized lump on his forehead. Upon questioning his mom about the incident, you learn that the boy fell from a seated position on a chair, which was about 2 feet off the ground. He did not lose consciousness and has no palpable skull fracture—and has been behaving normally ever since. Nonetheless, his mother wants to know if she should take the boy to the emergency department (ED) for a computed tomography (CT) head scan, “just to be safe.” What should you tell her?

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality. In the United States, pediatric head trauma is responsible for 7200 deaths, 60,000 hospitalizations, and more than 600,000 ED visits annually. 2 CT is the diagnostic standard when significant injury from head trauma is suspected, and more than half of all children brought to EDs as a result of head trauma undergo CT scanning. 3

CT is not risk free

CT scans are not benign, however. In addition to the risks associated with sedation, diagnostic radiation is a carcinogen. It is estimated that between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 5000 head CT scans results in a lethal malignancy, and the younger the child, the greater the risk. 4 Thus, when a child incurs a head injury, it is vital to weigh the potential benefit of imaging (discovering a serious, but treatable, injury) and the risk (CT-induced cancer).

Clinical prediction rules for head imaging in children have traditionally been less reliable than those for adults, especially for preverbal children. Guidelines agree that for children with moderate or severe head injury or with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤13, CT is definitely recommended. 5 The guidelines are less clear regarding the necessity of CT imaging for children with a GCS of 14 or 15.

Eight head trauma clinical prediction rules for kids existed as of December 2008, and they differed considerably in population characteristics, predictors, outcomes, and performance. Only 2 of the 8 prediction rules were derived from high-quality studies, and none were validated in a population separate from their derivation group. 6 A high-quality, high-performing, validated rule was needed to identify children at low risk for serious, treatable head injury—for whom head CT would be unnecessary.

STUDY SUMMARY: Large study yields 2 validated age-based rules

Researchers from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) conducted a prospective cohort study to first derive, and then to validate, clinical prediction rules to identify children at very low risk for clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI). They defined ciTBI as death as a result of TBI, need for neurosurgical intervention, intubation of >24 hours, or hospitalization for >2 nights for TBI.

Twenty-five North American EDs enrolled patients younger than 18 years with GCS scores of 14 or 15 who presented within 24 hours of head trauma. Patients were excluded if the mechanism of injury was trivial (ie, ground-level falls or walking or running into stationary objects with no signs or symptoms of head trauma other than scalp abrasions or lacerations). Also excluded were children who had incurred a penetrating trauma, had a known brain tumor or preexisting neurologic disorder that complicated assessment, or had undergone imaging for the head injury at an outside facility. Of 57,030 potential participants, 42,412 patients qualified for the study.

Because the researchers set out to develop 2 pediatric clinical prediction rules—1 for children <2 years of age (preverbal) and 1 for kids ≥2—they divided participants into these age groups. Both groups were further divided into derivation cohorts (8502 preverbal patients and 25,283 patients ≥2 years) and validation cohorts (2216 and 6411 patients, respectively).

Based on their clinical assessment, emergency physicians obtained CT scans for a total of 14,969 children and found ciTBIs in 376—35% and 0.9% of the 42,412 study participants, respectively. Sixty patients required neurosurgery. Investigators ascertained outcomes for the 65% of participants who did not undergo CT imaging via telephone, medical record, and morgue record follow-up; 96 patients returned to a participating health care facility for subsequent care and CT scanning as a result. Of those 96, 5 patients were found to have a TBI. One child had a ciTBI and was hospitalized for 2 nights for a cerebral contusion.

The investigators used established prediction rule methods and Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines to derive the rules. They assigned a relative cost of 500 to 1 for failure to identify a patient with ciTBI vs incorrect classification of a patient who did not have a ciTBI.

Negative finding=0 of 6 predictors

The rules that were derived and validated on the basis of this study are more detailed than previous pediatric prediction rules. For children <2 years, the new standard features 6 factors: altered mental status, palpable skull fracture, loss of consciousness (LOC) for ≥5 seconds, nonfrontal scalp hematoma, severe injury mechanism, and acting abnormally (according to the parents).

The prediction rule for children ≥2 years has 6 criteria, as well, with some key differences. While it, too, includes altered mental status and severe injury mechanism, it also includes clinical signs of basilar skull fracture, any LOC, a history of vomiting, and severe headache. The criteria are further defined, as follows:

Altered mental status: GCS <15, agitation, somnolence, repetitive questions, or slow response to verbal communication.

Severe injury mechanism: Motor vehicle crash with patient ejection, death of another passenger, or vehicle rollover; pedestrian or bicyclist without a helmet struck by a motor vehicle; falls of >3 feet for children <2 years and >5 feet for children ≥2; or head struck by a high-impact object.

Clinical signs of basilar skull fracture: Retroauricular bruising—Battle’s sign (peri-orbital bruising)—raccoon eyes, hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea or rhinorrhea.

In both prediction rules, a child is considered negative and, therefore, not in need of a CT scan, only if he or she has none of the 6 clinical predictors of ciTBI.

New rules are highly predictive

In the validation cohorts, the rule for children <2 years had a 100% negative predictive value for ciTBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 99.7-100) and a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 86.3-100). The rule for the older children had a negative predictive value of 99.95% (95% CI, 99.81-99.99) and a sensitivity of 96.8% (95% CI, 89-99.6).

In a child who has no clinical predictors, the risk of ciTBI is negligible—and, considering the risk of malignancy from CT scanning, imaging is not recommended. Recommendations for how to proceed if a child has any predictive factors depend on the clinical scenario and age of the patient. In children with a GCS score of 14 or with other signs of altered mental status or palpable skull fracture in those <2 years, or signs of basilar skull fracture in kids ≥2, the risk of ciTBI is slightly greater than 4%. CT is definitely recommended.

In children with a GCS score of 15 and a severe mechanism of injury or any other isolated prediction factor (LOC >5 seconds, non-frontal hematoma, or not acting normally according to a parent in kids <2; any history of LOC, severe headache, or history of vomiting in patients ≥2), the risk of ciTBI is less than 1%. For these children, either CT or observation may be appropriate, as determined by other factors, including clinician experience and patient/parent preference. CT scanning should be given greater consideration in patients who have multiple findings, worsening symptoms, or are <3 months old.

WHAT’S NEW: Rules shed light on hazy areas

These new PECARN rules perform much better than previous pediatric clinical predictors and differ in several ways from the 8 older pediatric head CT imaging rules. The key provisions are the same—if a child has a change in mental status with palpable or visible signs of skull fracture, proceed to imaging. However, this study clarifies which of the other predictors are most important. A severe mechanism of injury is important for all ages. For younger, preverbal children, a nonfrontal hematoma and a parental report of abnormal behavior are important predictors; vomiting or a LOC for <5 seconds is not. For children ≥2 years, vomiting, headache, and any LOC are important; a hematoma is not.

CAVEATS: Clinical decision making is still key

The PECARN rules should guide, rather than dictate, clinical decision making. They use a narrow definition of “clinically important” TBI outcomes—basically death, neurosurgery to prevent death, or prolonged observation to prevent neurosurgery. There are other important, albeit less dire, clinical decisions associated with TBI for which a brain CT may be useful—determining if a high school athlete can safely complete the football season or whether a child should receive anticonvulsant medication to decrease the likelihood of posttraumatic seizures.

We worry, too, that some providers may be tempted to use the rules for after-hours telephone triage. However, clinical assessment of the presence of signs of skull fracture, basilar or otherwise, requires in-person assessment by an experienced clinician.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Over- (or under-) reliance on the rules

The PECARN decision rules should simplify head trauma assessment in children. Physicians should first check for altered mental status and signs of skull fracture and immediately send the patient for imaging if either is present. Otherwise, physicians should continue the assessment—looking for the other clinical predictors and ordering a brain CT if 1 or more are found. However, risk of ciTBI is only 1% when only 1 prediction criterion is present. These cases require careful consideration of the potential benefit and risk.

Some emergency physicians may resist using a checklist approach, even one as useful as the PECARN decision guide, and continue to rely solely on their clinical judgment. And some parents are likely to insist on a CT scan for reassurance that there is no TBI, despite the absence of any clinical predictors.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of either the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to thank Sarah-Anne Schumann, MD, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, for her guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

2. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: assessing outcomes in children. CDC; 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/tbi_report/index.htm . Accessed December 3, 2009.

3. Klassen TP, Reed MH, Stiell IG, et al. Variation in utilization of computed tomography scanning for the investigation of minor head trauma in children: a Canadian experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:739-744.

4. Brenner DJ. Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:228-231.

5. National Guideline Clearing House, ACR Appropriateness Criteria, 2008. Available at: www.guidelines.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=13670&nbr=007004&string=head+AND+trauma . Accessed December 3, 2009.

6. Maguire JL, Boutis K, Uleryk EM, et al. Should a head-injured child receive a head CT scan? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e145-e154.

Use these newly derived and validated clinical prediction rules to decide which kids need a CT scan after head injury.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An anxious mother rushes into your office carrying her 22-month-old son, who fell and hit his head an hour ago. The child has an egg-sized lump on his forehead. Upon questioning his mom about the incident, you learn that the boy fell from a seated position on a chair, which was about 2 feet off the ground. He did not lose consciousness and has no palpable skull fracture—and has been behaving normally ever since. Nonetheless, his mother wants to know if she should take the boy to the emergency department (ED) for a computed tomography (CT) head scan, “just to be safe.” What should you tell her?

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality. In the United States, pediatric head trauma is responsible for 7200 deaths, 60,000 hospitalizations, and more than 600,000 ED visits annually. 2 CT is the diagnostic standard when significant injury from head trauma is suspected, and more than half of all children brought to EDs as a result of head trauma undergo CT scanning. 3

CT is not risk free

CT scans are not benign, however. In addition to the risks associated with sedation, diagnostic radiation is a carcinogen. It is estimated that between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 5000 head CT scans results in a lethal malignancy, and the younger the child, the greater the risk. 4 Thus, when a child incurs a head injury, it is vital to weigh the potential benefit of imaging (discovering a serious, but treatable, injury) and the risk (CT-induced cancer).

Clinical prediction rules for head imaging in children have traditionally been less reliable than those for adults, especially for preverbal children. Guidelines agree that for children with moderate or severe head injury or with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤13, CT is definitely recommended. 5 The guidelines are less clear regarding the necessity of CT imaging for children with a GCS of 14 or 15.

Eight head trauma clinical prediction rules for kids existed as of December 2008, and they differed considerably in population characteristics, predictors, outcomes, and performance. Only 2 of the 8 prediction rules were derived from high-quality studies, and none were validated in a population separate from their derivation group. 6 A high-quality, high-performing, validated rule was needed to identify children at low risk for serious, treatable head injury—for whom head CT would be unnecessary.

STUDY SUMMARY: Large study yields 2 validated age-based rules

Researchers from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) conducted a prospective cohort study to first derive, and then to validate, clinical prediction rules to identify children at very low risk for clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI). They defined ciTBI as death as a result of TBI, need for neurosurgical intervention, intubation of >24 hours, or hospitalization for >2 nights for TBI.

Twenty-five North American EDs enrolled patients younger than 18 years with GCS scores of 14 or 15 who presented within 24 hours of head trauma. Patients were excluded if the mechanism of injury was trivial (ie, ground-level falls or walking or running into stationary objects with no signs or symptoms of head trauma other than scalp abrasions or lacerations). Also excluded were children who had incurred a penetrating trauma, had a known brain tumor or preexisting neurologic disorder that complicated assessment, or had undergone imaging for the head injury at an outside facility. Of 57,030 potential participants, 42,412 patients qualified for the study.

Because the researchers set out to develop 2 pediatric clinical prediction rules—1 for children <2 years of age (preverbal) and 1 for kids ≥2—they divided participants into these age groups. Both groups were further divided into derivation cohorts (8502 preverbal patients and 25,283 patients ≥2 years) and validation cohorts (2216 and 6411 patients, respectively).

Based on their clinical assessment, emergency physicians obtained CT scans for a total of 14,969 children and found ciTBIs in 376—35% and 0.9% of the 42,412 study participants, respectively. Sixty patients required neurosurgery. Investigators ascertained outcomes for the 65% of participants who did not undergo CT imaging via telephone, medical record, and morgue record follow-up; 96 patients returned to a participating health care facility for subsequent care and CT scanning as a result. Of those 96, 5 patients were found to have a TBI. One child had a ciTBI and was hospitalized for 2 nights for a cerebral contusion.

The investigators used established prediction rule methods and Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines to derive the rules. They assigned a relative cost of 500 to 1 for failure to identify a patient with ciTBI vs incorrect classification of a patient who did not have a ciTBI.

Negative finding=0 of 6 predictors

The rules that were derived and validated on the basis of this study are more detailed than previous pediatric prediction rules. For children <2 years, the new standard features 6 factors: altered mental status, palpable skull fracture, loss of consciousness (LOC) for ≥5 seconds, nonfrontal scalp hematoma, severe injury mechanism, and acting abnormally (according to the parents).

The prediction rule for children ≥2 years has 6 criteria, as well, with some key differences. While it, too, includes altered mental status and severe injury mechanism, it also includes clinical signs of basilar skull fracture, any LOC, a history of vomiting, and severe headache. The criteria are further defined, as follows:

Altered mental status: GCS <15, agitation, somnolence, repetitive questions, or slow response to verbal communication.

Severe injury mechanism: Motor vehicle crash with patient ejection, death of another passenger, or vehicle rollover; pedestrian or bicyclist without a helmet struck by a motor vehicle; falls of >3 feet for children <2 years and >5 feet for children ≥2; or head struck by a high-impact object.

Clinical signs of basilar skull fracture: Retroauricular bruising—Battle’s sign (peri-orbital bruising)—raccoon eyes, hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea or rhinorrhea.

In both prediction rules, a child is considered negative and, therefore, not in need of a CT scan, only if he or she has none of the 6 clinical predictors of ciTBI.

New rules are highly predictive

In the validation cohorts, the rule for children <2 years had a 100% negative predictive value for ciTBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 99.7-100) and a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 86.3-100). The rule for the older children had a negative predictive value of 99.95% (95% CI, 99.81-99.99) and a sensitivity of 96.8% (95% CI, 89-99.6).

In a child who has no clinical predictors, the risk of ciTBI is negligible—and, considering the risk of malignancy from CT scanning, imaging is not recommended. Recommendations for how to proceed if a child has any predictive factors depend on the clinical scenario and age of the patient. In children with a GCS score of 14 or with other signs of altered mental status or palpable skull fracture in those <2 years, or signs of basilar skull fracture in kids ≥2, the risk of ciTBI is slightly greater than 4%. CT is definitely recommended.

In children with a GCS score of 15 and a severe mechanism of injury or any other isolated prediction factor (LOC >5 seconds, non-frontal hematoma, or not acting normally according to a parent in kids <2; any history of LOC, severe headache, or history of vomiting in patients ≥2), the risk of ciTBI is less than 1%. For these children, either CT or observation may be appropriate, as determined by other factors, including clinician experience and patient/parent preference. CT scanning should be given greater consideration in patients who have multiple findings, worsening symptoms, or are <3 months old.

WHAT’S NEW: Rules shed light on hazy areas

These new PECARN rules perform much better than previous pediatric clinical predictors and differ in several ways from the 8 older pediatric head CT imaging rules. The key provisions are the same—if a child has a change in mental status with palpable or visible signs of skull fracture, proceed to imaging. However, this study clarifies which of the other predictors are most important. A severe mechanism of injury is important for all ages. For younger, preverbal children, a nonfrontal hematoma and a parental report of abnormal behavior are important predictors; vomiting or a LOC for <5 seconds is not. For children ≥2 years, vomiting, headache, and any LOC are important; a hematoma is not.

CAVEATS: Clinical decision making is still key

The PECARN rules should guide, rather than dictate, clinical decision making. They use a narrow definition of “clinically important” TBI outcomes—basically death, neurosurgery to prevent death, or prolonged observation to prevent neurosurgery. There are other important, albeit less dire, clinical decisions associated with TBI for which a brain CT may be useful—determining if a high school athlete can safely complete the football season or whether a child should receive anticonvulsant medication to decrease the likelihood of posttraumatic seizures.

We worry, too, that some providers may be tempted to use the rules for after-hours telephone triage. However, clinical assessment of the presence of signs of skull fracture, basilar or otherwise, requires in-person assessment by an experienced clinician.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Over- (or under-) reliance on the rules

The PECARN decision rules should simplify head trauma assessment in children. Physicians should first check for altered mental status and signs of skull fracture and immediately send the patient for imaging if either is present. Otherwise, physicians should continue the assessment—looking for the other clinical predictors and ordering a brain CT if 1 or more are found. However, risk of ciTBI is only 1% when only 1 prediction criterion is present. These cases require careful consideration of the potential benefit and risk.

Some emergency physicians may resist using a checklist approach, even one as useful as the PECARN decision guide, and continue to rely solely on their clinical judgment. And some parents are likely to insist on a CT scan for reassurance that there is no TBI, despite the absence of any clinical predictors.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of either the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to thank Sarah-Anne Schumann, MD, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, for her guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

Use these newly derived and validated clinical prediction rules to decide which kids need a CT scan after head injury.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An anxious mother rushes into your office carrying her 22-month-old son, who fell and hit his head an hour ago. The child has an egg-sized lump on his forehead. Upon questioning his mom about the incident, you learn that the boy fell from a seated position on a chair, which was about 2 feet off the ground. He did not lose consciousness and has no palpable skull fracture—and has been behaving normally ever since. Nonetheless, his mother wants to know if she should take the boy to the emergency department (ED) for a computed tomography (CT) head scan, “just to be safe.” What should you tell her?

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality. In the United States, pediatric head trauma is responsible for 7200 deaths, 60,000 hospitalizations, and more than 600,000 ED visits annually. 2 CT is the diagnostic standard when significant injury from head trauma is suspected, and more than half of all children brought to EDs as a result of head trauma undergo CT scanning. 3

CT is not risk free

CT scans are not benign, however. In addition to the risks associated with sedation, diagnostic radiation is a carcinogen. It is estimated that between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 5000 head CT scans results in a lethal malignancy, and the younger the child, the greater the risk. 4 Thus, when a child incurs a head injury, it is vital to weigh the potential benefit of imaging (discovering a serious, but treatable, injury) and the risk (CT-induced cancer).

Clinical prediction rules for head imaging in children have traditionally been less reliable than those for adults, especially for preverbal children. Guidelines agree that for children with moderate or severe head injury or with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤13, CT is definitely recommended. 5 The guidelines are less clear regarding the necessity of CT imaging for children with a GCS of 14 or 15.

Eight head trauma clinical prediction rules for kids existed as of December 2008, and they differed considerably in population characteristics, predictors, outcomes, and performance. Only 2 of the 8 prediction rules were derived from high-quality studies, and none were validated in a population separate from their derivation group. 6 A high-quality, high-performing, validated rule was needed to identify children at low risk for serious, treatable head injury—for whom head CT would be unnecessary.

STUDY SUMMARY: Large study yields 2 validated age-based rules

Researchers from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) conducted a prospective cohort study to first derive, and then to validate, clinical prediction rules to identify children at very low risk for clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI). They defined ciTBI as death as a result of TBI, need for neurosurgical intervention, intubation of >24 hours, or hospitalization for >2 nights for TBI.

Twenty-five North American EDs enrolled patients younger than 18 years with GCS scores of 14 or 15 who presented within 24 hours of head trauma. Patients were excluded if the mechanism of injury was trivial (ie, ground-level falls or walking or running into stationary objects with no signs or symptoms of head trauma other than scalp abrasions or lacerations). Also excluded were children who had incurred a penetrating trauma, had a known brain tumor or preexisting neurologic disorder that complicated assessment, or had undergone imaging for the head injury at an outside facility. Of 57,030 potential participants, 42,412 patients qualified for the study.

Because the researchers set out to develop 2 pediatric clinical prediction rules—1 for children <2 years of age (preverbal) and 1 for kids ≥2—they divided participants into these age groups. Both groups were further divided into derivation cohorts (8502 preverbal patients and 25,283 patients ≥2 years) and validation cohorts (2216 and 6411 patients, respectively).

Based on their clinical assessment, emergency physicians obtained CT scans for a total of 14,969 children and found ciTBIs in 376—35% and 0.9% of the 42,412 study participants, respectively. Sixty patients required neurosurgery. Investigators ascertained outcomes for the 65% of participants who did not undergo CT imaging via telephone, medical record, and morgue record follow-up; 96 patients returned to a participating health care facility for subsequent care and CT scanning as a result. Of those 96, 5 patients were found to have a TBI. One child had a ciTBI and was hospitalized for 2 nights for a cerebral contusion.

The investigators used established prediction rule methods and Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines to derive the rules. They assigned a relative cost of 500 to 1 for failure to identify a patient with ciTBI vs incorrect classification of a patient who did not have a ciTBI.

Negative finding=0 of 6 predictors

The rules that were derived and validated on the basis of this study are more detailed than previous pediatric prediction rules. For children <2 years, the new standard features 6 factors: altered mental status, palpable skull fracture, loss of consciousness (LOC) for ≥5 seconds, nonfrontal scalp hematoma, severe injury mechanism, and acting abnormally (according to the parents).

The prediction rule for children ≥2 years has 6 criteria, as well, with some key differences. While it, too, includes altered mental status and severe injury mechanism, it also includes clinical signs of basilar skull fracture, any LOC, a history of vomiting, and severe headache. The criteria are further defined, as follows:

Altered mental status: GCS <15, agitation, somnolence, repetitive questions, or slow response to verbal communication.

Severe injury mechanism: Motor vehicle crash with patient ejection, death of another passenger, or vehicle rollover; pedestrian or bicyclist without a helmet struck by a motor vehicle; falls of >3 feet for children <2 years and >5 feet for children ≥2; or head struck by a high-impact object.

Clinical signs of basilar skull fracture: Retroauricular bruising—Battle’s sign (peri-orbital bruising)—raccoon eyes, hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea or rhinorrhea.

In both prediction rules, a child is considered negative and, therefore, not in need of a CT scan, only if he or she has none of the 6 clinical predictors of ciTBI.

New rules are highly predictive

In the validation cohorts, the rule for children <2 years had a 100% negative predictive value for ciTBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 99.7-100) and a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 86.3-100). The rule for the older children had a negative predictive value of 99.95% (95% CI, 99.81-99.99) and a sensitivity of 96.8% (95% CI, 89-99.6).

In a child who has no clinical predictors, the risk of ciTBI is negligible—and, considering the risk of malignancy from CT scanning, imaging is not recommended. Recommendations for how to proceed if a child has any predictive factors depend on the clinical scenario and age of the patient. In children with a GCS score of 14 or with other signs of altered mental status or palpable skull fracture in those <2 years, or signs of basilar skull fracture in kids ≥2, the risk of ciTBI is slightly greater than 4%. CT is definitely recommended.

In children with a GCS score of 15 and a severe mechanism of injury or any other isolated prediction factor (LOC >5 seconds, non-frontal hematoma, or not acting normally according to a parent in kids <2; any history of LOC, severe headache, or history of vomiting in patients ≥2), the risk of ciTBI is less than 1%. For these children, either CT or observation may be appropriate, as determined by other factors, including clinician experience and patient/parent preference. CT scanning should be given greater consideration in patients who have multiple findings, worsening symptoms, or are <3 months old.

WHAT’S NEW: Rules shed light on hazy areas

These new PECARN rules perform much better than previous pediatric clinical predictors and differ in several ways from the 8 older pediatric head CT imaging rules. The key provisions are the same—if a child has a change in mental status with palpable or visible signs of skull fracture, proceed to imaging. However, this study clarifies which of the other predictors are most important. A severe mechanism of injury is important for all ages. For younger, preverbal children, a nonfrontal hematoma and a parental report of abnormal behavior are important predictors; vomiting or a LOC for <5 seconds is not. For children ≥2 years, vomiting, headache, and any LOC are important; a hematoma is not.

CAVEATS: Clinical decision making is still key

The PECARN rules should guide, rather than dictate, clinical decision making. They use a narrow definition of “clinically important” TBI outcomes—basically death, neurosurgery to prevent death, or prolonged observation to prevent neurosurgery. There are other important, albeit less dire, clinical decisions associated with TBI for which a brain CT may be useful—determining if a high school athlete can safely complete the football season or whether a child should receive anticonvulsant medication to decrease the likelihood of posttraumatic seizures.

We worry, too, that some providers may be tempted to use the rules for after-hours telephone triage. However, clinical assessment of the presence of signs of skull fracture, basilar or otherwise, requires in-person assessment by an experienced clinician.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Over- (or under-) reliance on the rules

The PECARN decision rules should simplify head trauma assessment in children. Physicians should first check for altered mental status and signs of skull fracture and immediately send the patient for imaging if either is present. Otherwise, physicians should continue the assessment—looking for the other clinical predictors and ordering a brain CT if 1 or more are found. However, risk of ciTBI is only 1% when only 1 prediction criterion is present. These cases require careful consideration of the potential benefit and risk.

Some emergency physicians may resist using a checklist approach, even one as useful as the PECARN decision guide, and continue to rely solely on their clinical judgment. And some parents are likely to insist on a CT scan for reassurance that there is no TBI, despite the absence of any clinical predictors.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of either the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to thank Sarah-Anne Schumann, MD, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, for her guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

2. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: assessing outcomes in children. CDC; 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/tbi_report/index.htm . Accessed December 3, 2009.

3. Klassen TP, Reed MH, Stiell IG, et al. Variation in utilization of computed tomography scanning for the investigation of minor head trauma in children: a Canadian experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:739-744.

4. Brenner DJ. Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:228-231.

5. National Guideline Clearing House, ACR Appropriateness Criteria, 2008. Available at: www.guidelines.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=13670&nbr=007004&string=head+AND+trauma . Accessed December 3, 2009.

6. Maguire JL, Boutis K, Uleryk EM, et al. Should a head-injured child receive a head CT scan? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e145-e154.

1. Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160-1170.

2. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: assessing outcomes in children. CDC; 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/tbi_report/index.htm . Accessed December 3, 2009.

3. Klassen TP, Reed MH, Stiell IG, et al. Variation in utilization of computed tomography scanning for the investigation of minor head trauma in children: a Canadian experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:739-744.

4. Brenner DJ. Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:228-231.

5. National Guideline Clearing House, ACR Appropriateness Criteria, 2008. Available at: www.guidelines.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=13670&nbr=007004&string=head+AND+trauma . Accessed December 3, 2009.

6. Maguire JL, Boutis K, Uleryk EM, et al. Should a head-injured child receive a head CT scan? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e145-e154.

Copyright © 2010 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.

Initiating antidepressant therapy? Try these 2 drugs first

When you initiate antidepressant therapy for patients who have not been treated for depression previously, select either sertraline or escitalopram. A large meta-analysis found these medications to be superior to other “new-generation” antidepressants.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of 117 high-quality studies.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746-758.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Mrs. D is a 45-year-old patient whom you’ve treated for type 2 diabetes for several years. On her latest visit, she reports a loss of energy and difficulty sleeping and wonders if they could be related to the diabetes. As you explore further and question Mrs. D about these symptoms, she becomes tearful—and tells you she has episodes of sadness and no longer enjoys things the way she used to. Although she has no past history of depression, when you suggest that her symptoms may be an indication of depression, she readily agrees.

You discuss treatment options, including antidepressants and therapy. Mrs. D decides to try medication. But with so many antidepressants on the market, how do you determine which to choose?

Major depression is the fourth leading cause of disease globally, according to the World Health Organization.2 Depression is common in the United States as well, and primary care physicians are often the ones who are diagnosing and treating it. In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recently expanded its recommendation that primary care providers screen adults for depression, to include adolescents ages 12 to 18 years.3 When depression is diagnosed, physicians must help patients decide on an initial treatment plan.

All antidepressants are not equal

Options for initial treatment of unipolar major depression include psychotherapy and the use of an antidepressant. For mild and moderate depression, psychotherapy alone is as effective as medication. Combined psychotherapy and antidepressants are more effective than either treatment alone for all degrees of depression.4

The ideal medication for depression would be a drug with a high level of effectiveness and a low side-effect profile; until now, however, there has been little evidence to support 1 antidepressant over another. Previous meta-analyses have concluded that there are no significant differences in either efficacy or acceptability among the various second-generation antidepressants on the market.5,6 Thus, physicians have historically made initial monotherapy treatment decisions based on side effects and cost.7,8 The meta-analysis we report on here tells a different story, providing strong evidence that some antidepressants are more effective and better tolerated than others.

STUDY SUMMARY: Meta-analysis reveals 2 “best” drugs

Cipriani et al1 conducted a systematic review and multiple-treatments meta-analysis of 117 prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Taken together, the RCTs evaluated the comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 second-generation antidepressants: bupropion, citalopram, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, mirtazapine, paroxetine, reboxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. The methodology of this meta-analysis differed from that of traditional meta-analyses by allowing the integration of data from both direct and indirect comparisons. (An indirect comparison is one in which drugs from different trials are assessed by combining the results of their effectiveness and comparing the combined finding with the effectiveness of a drug that all the trials have in common.) Previous studies, based only on direct comparisons, yielded inconsistent results.

The studies included in this meta-analysis were all RCTs in which 1 of these 12 antidepressants was tested against 1, or several, other second-generation antidepressants as monotherapy for the acute treatment phase of unipolar major depression. The authors excluded placebo-controlled trials in order to evaluate efficacy and acceptability of the study medications relative to other commonly used antidepressants. They defined acute treatment as 8 weeks of antidepressant therapy, with a range of 6 to 12 weeks. The primary outcomes studied were response to treatment and dropout rate.

Response to treatment (efficacy) was constructed as a Yes or No variable; a positive response was defined as a reduction of ≥50% in symptom score on either the Hamilton depression rating scale or the Montgomery-Asberg rating scale, or a rating of “improved” or “very much improved” on the clinical global impression at 8 weeks. Efficacy was calculated on an intention-to-treat basis; if data were missing for a participant, that person was classified as a nonresponder.

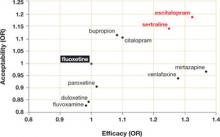

Dropout rate was used to represent acceptability, as the authors believed it to be a more clinically meaningful measure than either side effects or symptom scores. Comparative efficacy and acceptability were analyzed. Fluoxetine—the first of the second-generation antidepressants—was used as the reference medication. The ( FIGURE ) shows the outcomes for 9 of the antidepressants, compared with those of fluoxetine. The other 2 antidepressants, milnacipran and reboxetine, are omitted because they are not available in the United States.

The overall meta-analysis included 25,928 individuals, with 24,595 in the efficacy analysis and 24,693 in the acceptability analysis. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the participants were women. The mean duration of follow-up was 8.1 weeks, and mean sample size per study was 110. Studies of women with postpartum depression were excluded.

Escitalopram and sertraline stand out. Overall, escitalopram, mirtazapine, sertraline, and venlafaxine were significantly more efficacious than fluoxetine or the other medications. Bupropion, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline were better tolerated than the other antidepressants. Escitalopram and sertraline were found to have the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

Efficacy results. Fifty-nine percent of participants responded to sertraline, vs a 52% response rate for fluoxetine (number needed to treat [NNT]=14). Similarly, 52% of participants responded to escitalopram, compared with 47% of those taking fluoxetine (NNT=20).

Acceptability results. In terms of dropout rate, 28% of participants discontinued fluoxetine, vs 24% of patients taking sertraline. This means that 25 patients would need to be treated with sertraline, rather than fluoxetine, to avoid 1 discontinuation. In the comparison of fluoxetine vs escitalopram, 25% discontinued fluoxetine, compared with 24% who discontinued escitalopram.

The efficacy and acceptability of sertraline and escitalopram compared with other second-generation antidepressant medications show similar trends.

The generic advantage. The investigators recommend sertraline as the best choice for an initial antidepressant because it is available in generic form and is therefore lower in cost. They further recommend that sertraline, instead of fluoxetine or placebo, be the new standard against which other antidepressants are compared.

FIGURE

Sertraline and escitalopram come out on top

Using fluoxetine as the reference medication, the researchers analyzed various second-generation antidepressants. Sertraline and escitalopram had the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

OR, odds ratio.

Source: Cipriani A et al. Lancet. 2009.1

WHAT’S NEW?: Antidepressant choice is evidence-based

We now have solid evidence for choosing sertraline or escitalopram as the first medication to use when treating a patient with newly diagnosed depression. This represents a practice change because antidepressants that are less effective and less acceptable have been chosen more frequently than either of these medications. That conclusion is based on our analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey database for outpatient and ambulatory clinic visits in 2005-2006 (the most recent data available). We conducted this analysis to determine which of the second-generation antidepressants were prescribed most for initial monotherapy of major depression.

Our finding: An estimated 4 million patients ages 18 years and older diagnosed with depression in the course of the study year received new prescriptions for a single antidepressant. Six medications accounted for 90% of the prescriptions, in the following order:

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- venlafaxine (Effexor)

- sertraline (Zoloft).

Sertraline and escitalopram, the drugs shown to be most effective and acceptable in the Cipriani meta-analysis, accounted for 11.8% and 14.5% of the prescriptions, respectively.

CAVEATS: Meta-analysis looked only at acute treatment phase

The results of this study are limited to initial therapy as measured at 8 weeks. Little long-term outcome data are available; response to initial therapy may not be a predictor of full remission or long-term success. Current guidelines suggest maintenance of the initial successful therapy, often with increasing intervals between visits, to prevent relapse.9

This study does not add new insight into long-term response rates. Nor does it deal with choice of a replacement or second antidepressant for nonresponders or those who cannot tolerate the initial drug.

What’s more, the study covers drug treatment alone, which may not be the best initial treatment for depression. Psychotherapy, in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy, when available, is equally effective, has fewer potential physiologic side effects, and may produce longer-lasting results.10,11

Little is known about study design

The authors of this study had access only to limited information about inclusion criteria and the composition of initial study populations or settings. There is a difference between a trial designed to evaluate the “efficacy” of an intervention (“the beneficial and harmful effects of an intervention under controlled circumstances”) and the “effectiveness” of an intervention (the “beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention under usual circumstances”).12 It is not clear which of the 117 studies were efficacy studies and which were effectiveness studies. This may limit the overall generalizability of the study results to a primary care population.

Studies included in this meta-analysis were selected exclusively from published literature. There is some evidence that there is a bias toward the publication of studies with positive results, which may have the effect of overstating the effectiveness of a given antidepressant.13 However, we have no reason to believe that this bias would favor any particular drug.

Most of the included studies were sponsored by drug companies. Notably, pharmaceutical companies have the option of continuing to conduct trials of medications until a study results in a positive finding for their medication, with no penalty for the suppression of equivocal or negative results (negative publication bias). Under current FDA guidelines, there is little transparency to the consumer as to how many trials have been undertaken and the direction of the results, published or unpublished.14

We doubt that either publication bias or the design and sponsorship of the studies included in this meta-analysis present significant threats to the validity of these findings over other sources upon which guidelines rely, given that these issues are common to much of the research on pharmacologic therapy. We also doubt that the compensation of the authors by pharmaceutical companies would bias the outcome of the study in this instance. One of the authors (TAF) received compensation from Pfizer, the maker of Zoloft, which is also available as generic sertraline. None of the authors received compensation from Forest Pharmaceuticals, the makers of Lexapro (escitalopram).

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: No major barriers are anticipated

Both sertraline and escitalopram are covered by most health insurers. As noted above, sertraline is available in generic formulation, and is therefore much less expensive than escitalopram. In a check of online drug prices, we found a prescription for a 3-month supply of Lexapro (10 mg) to cost about $250; a 3-month supply of generic sertraline (100 mg) from the same sources would cost approximately $35 (www.pharmcychecker.com). Both Pfizer, the maker of Zoloft, and Forest Pharmaceuticals, the maker of Lexapro, have patient assistance programs to make these medications available to low-income, uninsured patients.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR02499 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to acknowledge Sofia Medvedev, PhD, of the University HealthSystem Consortium in Oak Brook, Ill, for analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data and the UHC Clinical Database.

1. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746-758.

2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996.

3. Williams SB, O’Connor EA, Eder M, et al. Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e716-e735.

4. Timonen M, Liukkonen T. Management of depression in adults. BMJ. 2008;336:435-439.

5. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Thieda P, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Depression. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 7. (Prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016.) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2007. Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Accessed May 18, 2009.

6. Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, et al. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:415-426.

7. Adams SM, Miller KE, Zylstra RG. Pharmacologic management of adult depression. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:785-792.

8. Qaseem A, Snow V, Denberg TD, et al. Using second-generation antidepressants to treat depressive disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:725-733.

9. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:409-416.

10. deMello MF, de Jesus MJ, Bacaltchuk J, et al. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75-82.

11. APA Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, second edition. Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/content.aspx?aID=48727. Accessed June 16, 2009.

12. Sackett D. An introduction to performing therapeutic trials. In: Haynes RB, Sackett DL, et al, eds. Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

13. Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

14. Mathew SJ, Charney DS. Publication bias and the efficacy of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:140-145.

PURLs methodology This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

When you initiate antidepressant therapy for patients who have not been treated for depression previously, select either sertraline or escitalopram. A large meta-analysis found these medications to be superior to other “new-generation” antidepressants.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of 117 high-quality studies.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746-758.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Mrs. D is a 45-year-old patient whom you’ve treated for type 2 diabetes for several years. On her latest visit, she reports a loss of energy and difficulty sleeping and wonders if they could be related to the diabetes. As you explore further and question Mrs. D about these symptoms, she becomes tearful—and tells you she has episodes of sadness and no longer enjoys things the way she used to. Although she has no past history of depression, when you suggest that her symptoms may be an indication of depression, she readily agrees.

You discuss treatment options, including antidepressants and therapy. Mrs. D decides to try medication. But with so many antidepressants on the market, how do you determine which to choose?

Major depression is the fourth leading cause of disease globally, according to the World Health Organization.2 Depression is common in the United States as well, and primary care physicians are often the ones who are diagnosing and treating it. In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recently expanded its recommendation that primary care providers screen adults for depression, to include adolescents ages 12 to 18 years.3 When depression is diagnosed, physicians must help patients decide on an initial treatment plan.

All antidepressants are not equal

Options for initial treatment of unipolar major depression include psychotherapy and the use of an antidepressant. For mild and moderate depression, psychotherapy alone is as effective as medication. Combined psychotherapy and antidepressants are more effective than either treatment alone for all degrees of depression.4

The ideal medication for depression would be a drug with a high level of effectiveness and a low side-effect profile; until now, however, there has been little evidence to support 1 antidepressant over another. Previous meta-analyses have concluded that there are no significant differences in either efficacy or acceptability among the various second-generation antidepressants on the market.5,6 Thus, physicians have historically made initial monotherapy treatment decisions based on side effects and cost.7,8 The meta-analysis we report on here tells a different story, providing strong evidence that some antidepressants are more effective and better tolerated than others.

STUDY SUMMARY: Meta-analysis reveals 2 “best” drugs

Cipriani et al1 conducted a systematic review and multiple-treatments meta-analysis of 117 prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Taken together, the RCTs evaluated the comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 second-generation antidepressants: bupropion, citalopram, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, mirtazapine, paroxetine, reboxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. The methodology of this meta-analysis differed from that of traditional meta-analyses by allowing the integration of data from both direct and indirect comparisons. (An indirect comparison is one in which drugs from different trials are assessed by combining the results of their effectiveness and comparing the combined finding with the effectiveness of a drug that all the trials have in common.) Previous studies, based only on direct comparisons, yielded inconsistent results.

The studies included in this meta-analysis were all RCTs in which 1 of these 12 antidepressants was tested against 1, or several, other second-generation antidepressants as monotherapy for the acute treatment phase of unipolar major depression. The authors excluded placebo-controlled trials in order to evaluate efficacy and acceptability of the study medications relative to other commonly used antidepressants. They defined acute treatment as 8 weeks of antidepressant therapy, with a range of 6 to 12 weeks. The primary outcomes studied were response to treatment and dropout rate.

Response to treatment (efficacy) was constructed as a Yes or No variable; a positive response was defined as a reduction of ≥50% in symptom score on either the Hamilton depression rating scale or the Montgomery-Asberg rating scale, or a rating of “improved” or “very much improved” on the clinical global impression at 8 weeks. Efficacy was calculated on an intention-to-treat basis; if data were missing for a participant, that person was classified as a nonresponder.

Dropout rate was used to represent acceptability, as the authors believed it to be a more clinically meaningful measure than either side effects or symptom scores. Comparative efficacy and acceptability were analyzed. Fluoxetine—the first of the second-generation antidepressants—was used as the reference medication. The ( FIGURE ) shows the outcomes for 9 of the antidepressants, compared with those of fluoxetine. The other 2 antidepressants, milnacipran and reboxetine, are omitted because they are not available in the United States.

The overall meta-analysis included 25,928 individuals, with 24,595 in the efficacy analysis and 24,693 in the acceptability analysis. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the participants were women. The mean duration of follow-up was 8.1 weeks, and mean sample size per study was 110. Studies of women with postpartum depression were excluded.

Escitalopram and sertraline stand out. Overall, escitalopram, mirtazapine, sertraline, and venlafaxine were significantly more efficacious than fluoxetine or the other medications. Bupropion, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline were better tolerated than the other antidepressants. Escitalopram and sertraline were found to have the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

Efficacy results. Fifty-nine percent of participants responded to sertraline, vs a 52% response rate for fluoxetine (number needed to treat [NNT]=14). Similarly, 52% of participants responded to escitalopram, compared with 47% of those taking fluoxetine (NNT=20).

Acceptability results. In terms of dropout rate, 28% of participants discontinued fluoxetine, vs 24% of patients taking sertraline. This means that 25 patients would need to be treated with sertraline, rather than fluoxetine, to avoid 1 discontinuation. In the comparison of fluoxetine vs escitalopram, 25% discontinued fluoxetine, compared with 24% who discontinued escitalopram.

The efficacy and acceptability of sertraline and escitalopram compared with other second-generation antidepressant medications show similar trends.

The generic advantage. The investigators recommend sertraline as the best choice for an initial antidepressant because it is available in generic form and is therefore lower in cost. They further recommend that sertraline, instead of fluoxetine or placebo, be the new standard against which other antidepressants are compared.

FIGURE

Sertraline and escitalopram come out on top

Using fluoxetine as the reference medication, the researchers analyzed various second-generation antidepressants. Sertraline and escitalopram had the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

OR, odds ratio.

Source: Cipriani A et al. Lancet. 2009.1

WHAT’S NEW?: Antidepressant choice is evidence-based

We now have solid evidence for choosing sertraline or escitalopram as the first medication to use when treating a patient with newly diagnosed depression. This represents a practice change because antidepressants that are less effective and less acceptable have been chosen more frequently than either of these medications. That conclusion is based on our analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey database for outpatient and ambulatory clinic visits in 2005-2006 (the most recent data available). We conducted this analysis to determine which of the second-generation antidepressants were prescribed most for initial monotherapy of major depression.

Our finding: An estimated 4 million patients ages 18 years and older diagnosed with depression in the course of the study year received new prescriptions for a single antidepressant. Six medications accounted for 90% of the prescriptions, in the following order:

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- venlafaxine (Effexor)

- sertraline (Zoloft).

Sertraline and escitalopram, the drugs shown to be most effective and acceptable in the Cipriani meta-analysis, accounted for 11.8% and 14.5% of the prescriptions, respectively.

CAVEATS: Meta-analysis looked only at acute treatment phase

The results of this study are limited to initial therapy as measured at 8 weeks. Little long-term outcome data are available; response to initial therapy may not be a predictor of full remission or long-term success. Current guidelines suggest maintenance of the initial successful therapy, often with increasing intervals between visits, to prevent relapse.9

This study does not add new insight into long-term response rates. Nor does it deal with choice of a replacement or second antidepressant for nonresponders or those who cannot tolerate the initial drug.

What’s more, the study covers drug treatment alone, which may not be the best initial treatment for depression. Psychotherapy, in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy, when available, is equally effective, has fewer potential physiologic side effects, and may produce longer-lasting results.10,11

Little is known about study design

The authors of this study had access only to limited information about inclusion criteria and the composition of initial study populations or settings. There is a difference between a trial designed to evaluate the “efficacy” of an intervention (“the beneficial and harmful effects of an intervention under controlled circumstances”) and the “effectiveness” of an intervention (the “beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention under usual circumstances”).12 It is not clear which of the 117 studies were efficacy studies and which were effectiveness studies. This may limit the overall generalizability of the study results to a primary care population.

Studies included in this meta-analysis were selected exclusively from published literature. There is some evidence that there is a bias toward the publication of studies with positive results, which may have the effect of overstating the effectiveness of a given antidepressant.13 However, we have no reason to believe that this bias would favor any particular drug.

Most of the included studies were sponsored by drug companies. Notably, pharmaceutical companies have the option of continuing to conduct trials of medications until a study results in a positive finding for their medication, with no penalty for the suppression of equivocal or negative results (negative publication bias). Under current FDA guidelines, there is little transparency to the consumer as to how many trials have been undertaken and the direction of the results, published or unpublished.14

We doubt that either publication bias or the design and sponsorship of the studies included in this meta-analysis present significant threats to the validity of these findings over other sources upon which guidelines rely, given that these issues are common to much of the research on pharmacologic therapy. We also doubt that the compensation of the authors by pharmaceutical companies would bias the outcome of the study in this instance. One of the authors (TAF) received compensation from Pfizer, the maker of Zoloft, which is also available as generic sertraline. None of the authors received compensation from Forest Pharmaceuticals, the makers of Lexapro (escitalopram).

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: No major barriers are anticipated

Both sertraline and escitalopram are covered by most health insurers. As noted above, sertraline is available in generic formulation, and is therefore much less expensive than escitalopram. In a check of online drug prices, we found a prescription for a 3-month supply of Lexapro (10 mg) to cost about $250; a 3-month supply of generic sertraline (100 mg) from the same sources would cost approximately $35 (www.pharmcychecker.com). Both Pfizer, the maker of Zoloft, and Forest Pharmaceuticals, the maker of Lexapro, have patient assistance programs to make these medications available to low-income, uninsured patients.

Acknowledgements

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR02499 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to acknowledge Sofia Medvedev, PhD, of the University HealthSystem Consortium in Oak Brook, Ill, for analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data and the UHC Clinical Database.

When you initiate antidepressant therapy for patients who have not been treated for depression previously, select either sertraline or escitalopram. A large meta-analysis found these medications to be superior to other “new-generation” antidepressants.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of 117 high-quality studies.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746-758.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Mrs. D is a 45-year-old patient whom you’ve treated for type 2 diabetes for several years. On her latest visit, she reports a loss of energy and difficulty sleeping and wonders if they could be related to the diabetes. As you explore further and question Mrs. D about these symptoms, she becomes tearful—and tells you she has episodes of sadness and no longer enjoys things the way she used to. Although she has no past history of depression, when you suggest that her symptoms may be an indication of depression, she readily agrees.

You discuss treatment options, including antidepressants and therapy. Mrs. D decides to try medication. But with so many antidepressants on the market, how do you determine which to choose?

Major depression is the fourth leading cause of disease globally, according to the World Health Organization.2 Depression is common in the United States as well, and primary care physicians are often the ones who are diagnosing and treating it. In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recently expanded its recommendation that primary care providers screen adults for depression, to include adolescents ages 12 to 18 years.3 When depression is diagnosed, physicians must help patients decide on an initial treatment plan.

All antidepressants are not equal

Options for initial treatment of unipolar major depression include psychotherapy and the use of an antidepressant. For mild and moderate depression, psychotherapy alone is as effective as medication. Combined psychotherapy and antidepressants are more effective than either treatment alone for all degrees of depression.4

The ideal medication for depression would be a drug with a high level of effectiveness and a low side-effect profile; until now, however, there has been little evidence to support 1 antidepressant over another. Previous meta-analyses have concluded that there are no significant differences in either efficacy or acceptability among the various second-generation antidepressants on the market.5,6 Thus, physicians have historically made initial monotherapy treatment decisions based on side effects and cost.7,8 The meta-analysis we report on here tells a different story, providing strong evidence that some antidepressants are more effective and better tolerated than others.

STUDY SUMMARY: Meta-analysis reveals 2 “best” drugs

Cipriani et al1 conducted a systematic review and multiple-treatments meta-analysis of 117 prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Taken together, the RCTs evaluated the comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 second-generation antidepressants: bupropion, citalopram, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, mirtazapine, paroxetine, reboxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. The methodology of this meta-analysis differed from that of traditional meta-analyses by allowing the integration of data from both direct and indirect comparisons. (An indirect comparison is one in which drugs from different trials are assessed by combining the results of their effectiveness and comparing the combined finding with the effectiveness of a drug that all the trials have in common.) Previous studies, based only on direct comparisons, yielded inconsistent results.

The studies included in this meta-analysis were all RCTs in which 1 of these 12 antidepressants was tested against 1, or several, other second-generation antidepressants as monotherapy for the acute treatment phase of unipolar major depression. The authors excluded placebo-controlled trials in order to evaluate efficacy and acceptability of the study medications relative to other commonly used antidepressants. They defined acute treatment as 8 weeks of antidepressant therapy, with a range of 6 to 12 weeks. The primary outcomes studied were response to treatment and dropout rate.

Response to treatment (efficacy) was constructed as a Yes or No variable; a positive response was defined as a reduction of ≥50% in symptom score on either the Hamilton depression rating scale or the Montgomery-Asberg rating scale, or a rating of “improved” or “very much improved” on the clinical global impression at 8 weeks. Efficacy was calculated on an intention-to-treat basis; if data were missing for a participant, that person was classified as a nonresponder.

Dropout rate was used to represent acceptability, as the authors believed it to be a more clinically meaningful measure than either side effects or symptom scores. Comparative efficacy and acceptability were analyzed. Fluoxetine—the first of the second-generation antidepressants—was used as the reference medication. The ( FIGURE ) shows the outcomes for 9 of the antidepressants, compared with those of fluoxetine. The other 2 antidepressants, milnacipran and reboxetine, are omitted because they are not available in the United States.

The overall meta-analysis included 25,928 individuals, with 24,595 in the efficacy analysis and 24,693 in the acceptability analysis. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the participants were women. The mean duration of follow-up was 8.1 weeks, and mean sample size per study was 110. Studies of women with postpartum depression were excluded.

Escitalopram and sertraline stand out. Overall, escitalopram, mirtazapine, sertraline, and venlafaxine were significantly more efficacious than fluoxetine or the other medications. Bupropion, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline were better tolerated than the other antidepressants. Escitalopram and sertraline were found to have the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

Efficacy results. Fifty-nine percent of participants responded to sertraline, vs a 52% response rate for fluoxetine (number needed to treat [NNT]=14). Similarly, 52% of participants responded to escitalopram, compared with 47% of those taking fluoxetine (NNT=20).

Acceptability results. In terms of dropout rate, 28% of participants discontinued fluoxetine, vs 24% of patients taking sertraline. This means that 25 patients would need to be treated with sertraline, rather than fluoxetine, to avoid 1 discontinuation. In the comparison of fluoxetine vs escitalopram, 25% discontinued fluoxetine, compared with 24% who discontinued escitalopram.

The efficacy and acceptability of sertraline and escitalopram compared with other second-generation antidepressant medications show similar trends.

The generic advantage. The investigators recommend sertraline as the best choice for an initial antidepressant because it is available in generic form and is therefore lower in cost. They further recommend that sertraline, instead of fluoxetine or placebo, be the new standard against which other antidepressants are compared.

FIGURE

Sertraline and escitalopram come out on top

Using fluoxetine as the reference medication, the researchers analyzed various second-generation antidepressants. Sertraline and escitalopram had the best combination of efficacy and acceptability.

OR, odds ratio.

Source: Cipriani A et al. Lancet. 2009.1

WHAT’S NEW?: Antidepressant choice is evidence-based

We now have solid evidence for choosing sertraline or escitalopram as the first medication to use when treating a patient with newly diagnosed depression. This represents a practice change because antidepressants that are less effective and less acceptable have been chosen more frequently than either of these medications. That conclusion is based on our analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey database for outpatient and ambulatory clinic visits in 2005-2006 (the most recent data available). We conducted this analysis to determine which of the second-generation antidepressants were prescribed most for initial monotherapy of major depression.

Our finding: An estimated 4 million patients ages 18 years and older diagnosed with depression in the course of the study year received new prescriptions for a single antidepressant. Six medications accounted for 90% of the prescriptions, in the following order:

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- venlafaxine (Effexor)

- sertraline (Zoloft).

Sertraline and escitalopram, the drugs shown to be most effective and acceptable in the Cipriani meta-analysis, accounted for 11.8% and 14.5% of the prescriptions, respectively.

CAVEATS: Meta-analysis looked only at acute treatment phase

The results of this study are limited to initial therapy as measured at 8 weeks. Little long-term outcome data are available; response to initial therapy may not be a predictor of full remission or long-term success. Current guidelines suggest maintenance of the initial successful therapy, often with increasing intervals between visits, to prevent relapse.9

This study does not add new insight into long-term response rates. Nor does it deal with choice of a replacement or second antidepressant for nonresponders or those who cannot tolerate the initial drug.

What’s more, the study covers drug treatment alone, which may not be the best initial treatment for depression. Psychotherapy, in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy, when available, is equally effective, has fewer potential physiologic side effects, and may produce longer-lasting results.10,11

Little is known about study design