User login

What family physicians can do to combat bullying

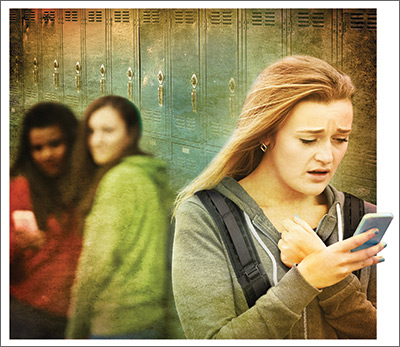

CASE › Stacey, a 12-year-old girl with mild persistent asthma, presents to her family physician (FP) with her mother for her annual well visit. Stacey reports no complaints, but has visited twice recently for acute exacerbations of her asthma, which had previously been well-controlled. When reviewing her social history, Stacey reports that she started her second year of middle school 3 months ago. When asked if she enjoys school, Stacey looks down and says, “School is fine.” Her mother quickly adds that Stacey has quit the school cheerleading team—much to the coach’s dismay—and is having difficulty in her math class, a class in which she normally excels. Stacey appears embarrassed that her mother has brought these things up. Her mother says that at the beginning of the year, 2 girls began picking on Stacey, calling her names and making fun of her on social media and in front of other students.

For many years, bullying was trivialized. Some viewed it as a universal childhood experience; others considered it a rite of passage.1,2 It was not examined as a public health issue until the 1970s. In fact, no legislation addressing bullying or “peer abuse” existed in the United States until the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo, in 1999. Within 3 years of the Columbine tragedy, the number of state laws that mentioned bullying went from zero to 15; within 10 years of Columbine, 41 states had laws addressing bullying,1 and by 2015, every state, the District of Columbia, and some territories had a bullying law in place.3

As research and advocacy regarding bullying has grown, its impact on the health of children, adolescents, and even adults has become more apparent. In a 2001 study of school-associated violent deaths in the United States between 1994 and 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that among students, homicide perpetrators were more than twice as likely as homicide victims to have been bullied by peers.4 Given that homicide is the third leading cause of death in people ages 15 to 24,5 past exposure to bullying may be a significant contributing factor to mortality in this age group.4

In addition to a correlation with homicidal behavior, those involved in bullying—whether as the bully or victim—are at risk for a wide range of symptoms, conditions, and problems including poor psychosocial adjustment, depression, anxiety, suicide (the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 and 15-24 age groups5), academic decline, psychosomatic manifestations, fighting, alcohol use, smoking, and difficulty with the management of chronic diseases.6-10 Not only does being a victim of bullying have a direct impact on a child’s current mental and physical well-being, but it can have lasting psychological and behavioral effects that can follow children well into adulthood.7 The significant impact of bullying on individuals and society as a whole mandates a multifaceted approach that begins in your exam room. What follows is practical advice on screening, counseling, and working with schools and the community at large to curb the bullying epidemic.

Clarifying the problem: The CDC’s definition

Recognizing that varying definitions of bullying were being used in research studies that looked at violent or aggressive behaviors in youth, the CDC published a consensus statement in 2014 that proposed the following definition for bullying:11 any unwanted aggressive behavior by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. This expanded on an earlier definition by Olweus12,13 that also identified a longitudinal nature and power imbalance as key features.

Types of bullying. Direct bullying entails blatant attacks on a targeted young person, while indirect bullying involves communication with others about the targeted individual (eg, spreading harmful rumors). Bullying may be physical, verbal, or relational (eg, excluding someone from their usual social circle, denying friendship, the silent treatment, writing mean letters, eye rolling, etc.) and may involve damage to property. Boys tend toward more direct bullying behaviors, while girls more often engage in indirect bullying, which may be more challenging for both adults and other students to recognize.12,13 With increased use of technology and social media by adolescents, cyberbullying has become increasingly more prevalent, with its effects on adolescent health and academics being every bit as profound as those of traditional bullying.14

About 1 in 4/5 students suffer. The prevalence of bullying ranges by country and culture. The vast majority of early bullying research was conducted in Norway, which found that approximately 15% of students in elementary and secondary schools were involved in bullying in some capacity.12 In a study involving over 200,000 adolescents from 40 European countries, 26% of adolescents reported being involved in bullying, ranging from 8.6% to 45.2% for boys and 4.8% to 35.8% for girls.15 Variations in prevalence may be due to cultural differences in the acts of bullying or differences in interpretation of the term “bullying.”1,15

In the United States, a 2001 survey of more than 15,000 students in public and private schools (grades 6-10) asked the students about their involvement in bullying: 13% said they'd been a bully, 10.6% a victim, and 6.3% said they'd been both.6 There was no significant difference in the frequency of self-reported bullying among urban, suburban, or rural settings.

Despite efforts to educate the public about bullying and work with schools to intervene and prevent bullying, incidence remains largely unchanged. In 2013, the National Crime Victimization Survey reported that approximately 22% of adolescents ages 12 through 18 were victims of bullying.16 Similarly, the CDC's 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System reported that 20.2% of high school students experienced bullying on school property.17

Screening: Best practices

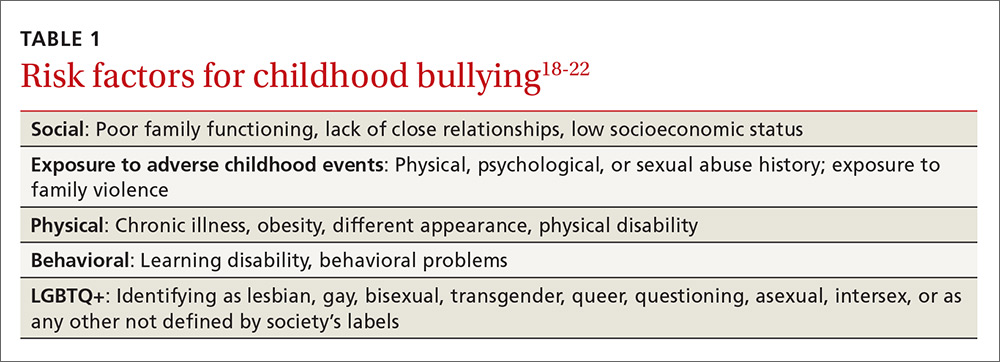

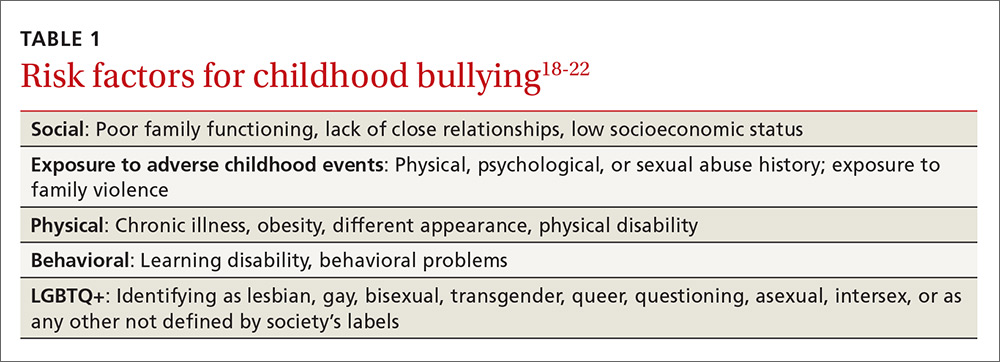

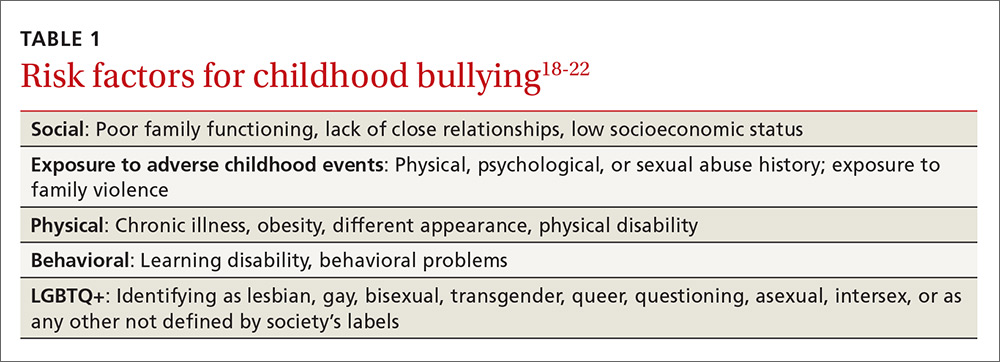

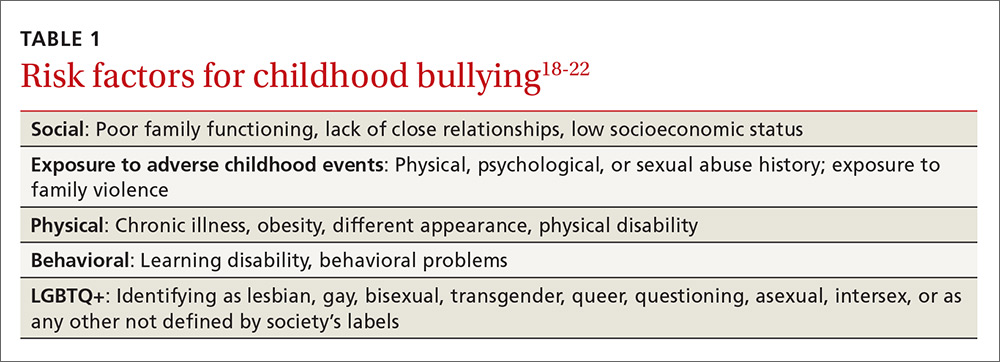

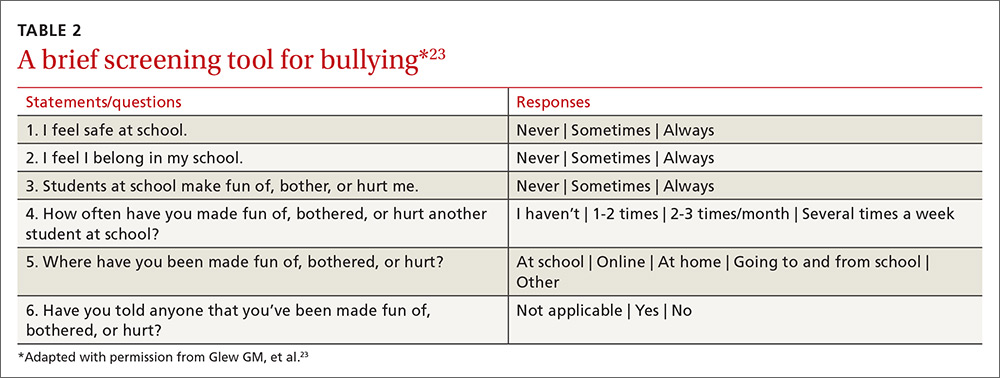

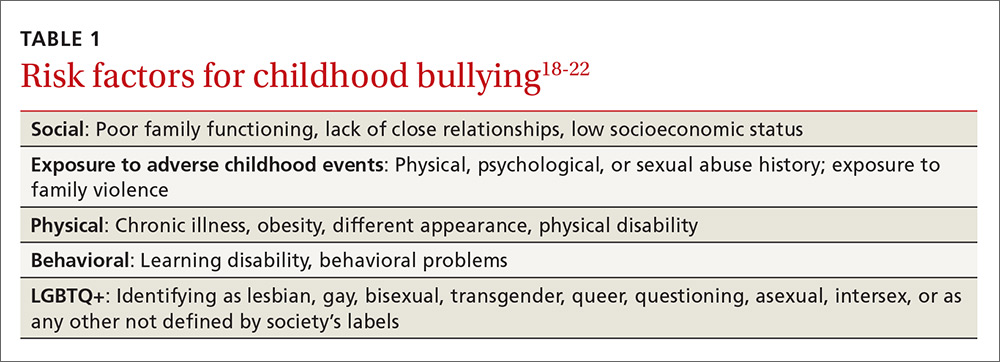

The FP’s role begins with screening children at risk for bullying (TABLE 118-22) or those whose complaints suggest that they may be victims of bullying.

Start screening when children enter elementary school

Given that providers’ time is limited for every patient visit, it is important to address bullying at times that are most likely to yield impactful results. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the topic of bullying be introduced at the 6-year-old well-child visit (a typical age for entry to elementary school).7 Views in the literature are inconsistent regarding when and how to address bullying at other time points. One approach is to pre-screen those with risk factors associated with bullying (TABLE 118-22), and to focus screening on those with warning signs of bullying, which include mood disorders, psychosomatic or behavioral symptoms, substance abuse, self-harm behaviors, suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, a decline in academic performance, and reports of school truancy. Parental concerns, such as when a child suddenly needs more money for lunch, is having aggressive outbursts, or is exhibiting unexplained physical injuries, should also be regarded as cues to screen.9

Screen patients in high-risk groups

A number of groups of children are at high risk for bullying and warrant targeted screening efforts.

- Children with special health needs. Research has shown that children with special health needs are at increased risk for being bullied.18 In fact, the presence of a chronic disease may increase the risk for bullying, and bullying often negatively impacts chronic disease management. As a result, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion with patients who have a chronic disease and who are not responding as expected to medical management or who experience deterioration after being previously well-controlled.18

- Children who are under- or overweight. Similarly, bullying based on a child's weight is a phenomenon that has been recognized to have a significant impact on children’s emotional health.19

- Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ peers to attempt suicide when exposed to a hostile social environment, such as that created by bullying.20

Screening need not be complicated

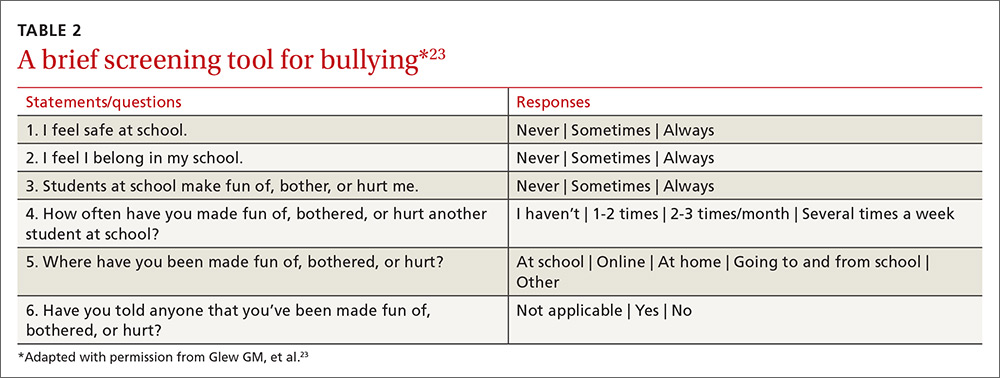

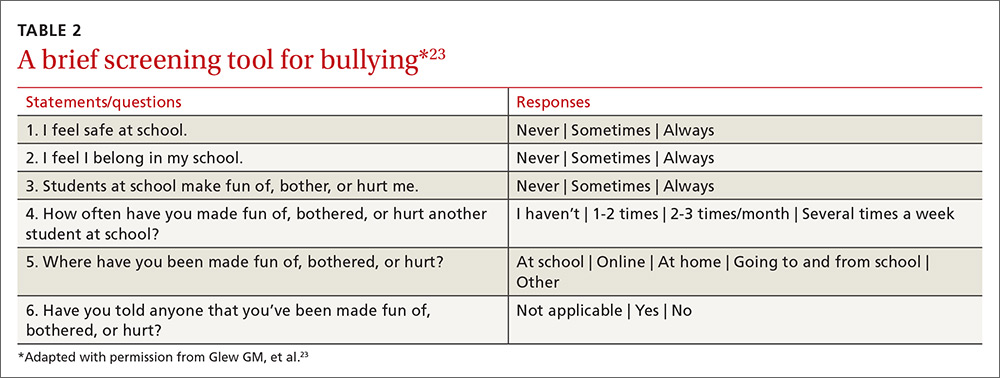

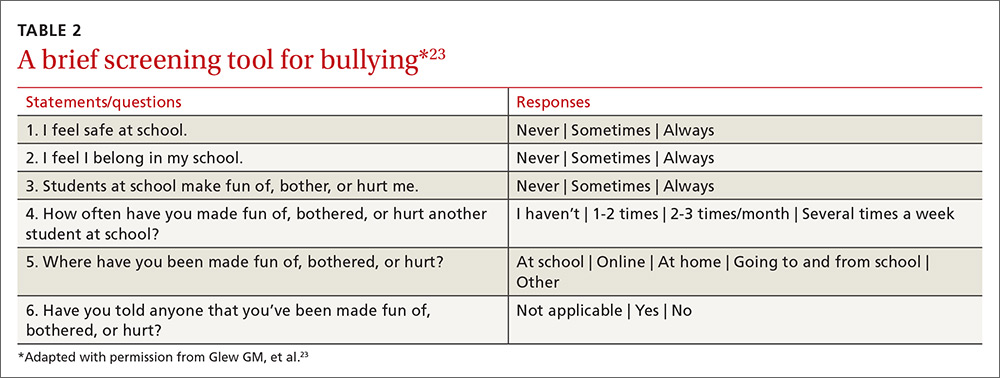

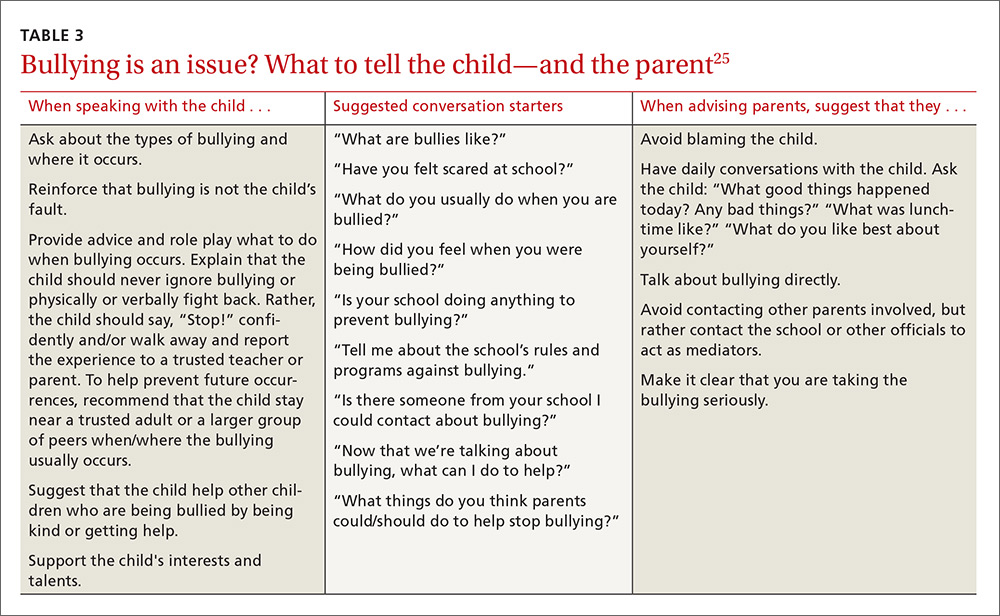

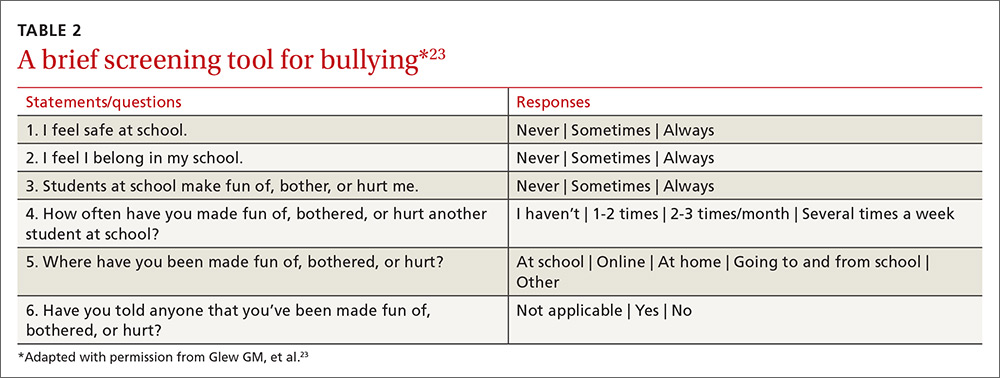

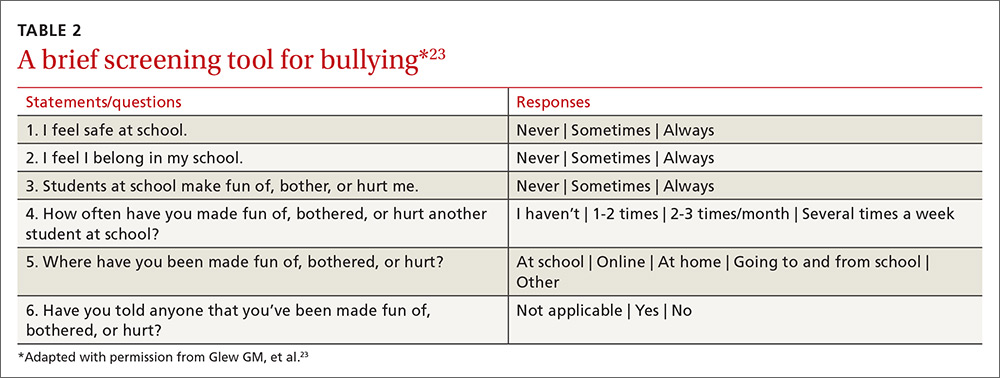

One screening approach is simply to ask patients, “Are you being bullied?” followed by such questions as, “How often are you bullied?” or “How long have you been bullied?” Asking about the setting of the bullying (Does it happen at school? Traveling to/from school? Online?) and other details may help guide interventions and the provision of resources.9 Another approach is to provide patients with some type of written survey (see TABLE 223 for an example) to encourage responses that patients might be reluctant to disclose verbally.23,24 (See “Barriers to screening.")

SIDEBAR

Barriers to screeningScreening for any condition presupposes a response. Ideally, family physicians should be prepared to provide basic counseling, resources, and, if necessary, treatment, if a patient screens positive for bullying. But screening for violence or bullying can be difficult, and evidence-based guidelines for screening and intervention are lacking, leaving many primary care practitioners feeling ill-equipped to meaningfully respond.

One study of the use of a screening tool aimed at intimate partner violence (IPV) showed that even with the availability of a screening tool, health care providers’ use of the tool was inconsistent and referral practices were ineffective.1 Providers cited the following limiting factors in screening for IPV: 1) a lack of immediate referral availability, 2) a lack of time during the office visit, and 3) a lack of confidence in the ability to screen.1 These same issues may be barriers to screening for bullying.

1. Ramachandran DV, Covarrubias L, Watson C, et al. How you screen is as important as whether you screen: a qualitative analysis of violence screening practices in reproductive health clinics. J Community Health. 2013;38:856-863.

Provider and parental interventions

Interventions often entail counseling the patient and the family about bullying and its effects, empowering victims and their caregivers, and screening for bullying comorbidities and correlates.2 Refer patients to behavioral health specialists when there is evidence of pervasive effects on mood, behavior, or social development, but keep in mind that counseling can begin in your own exam room.

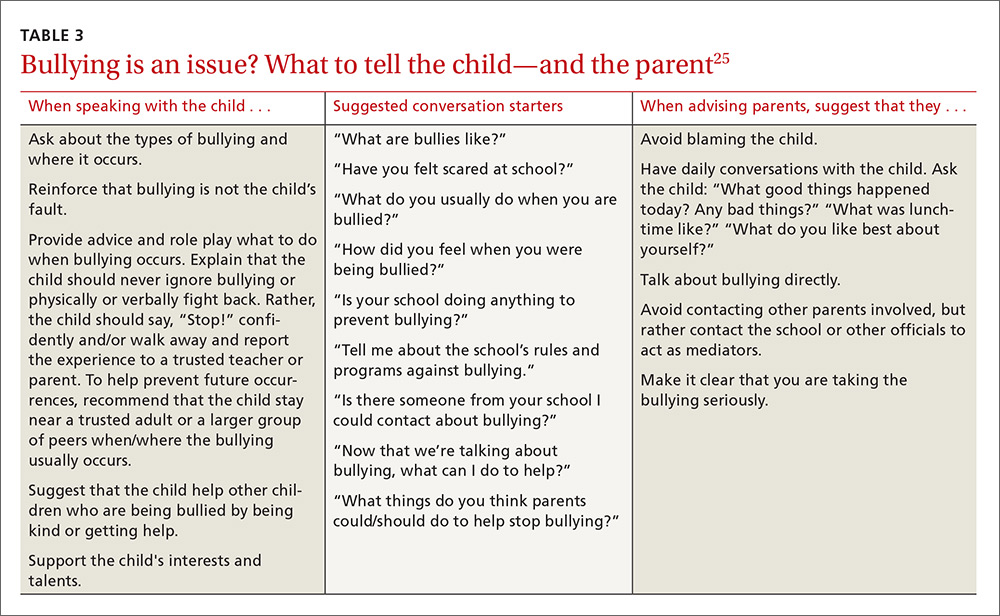

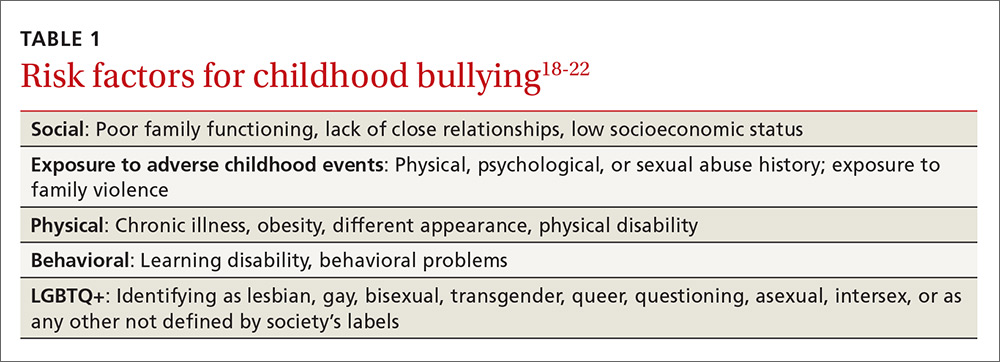

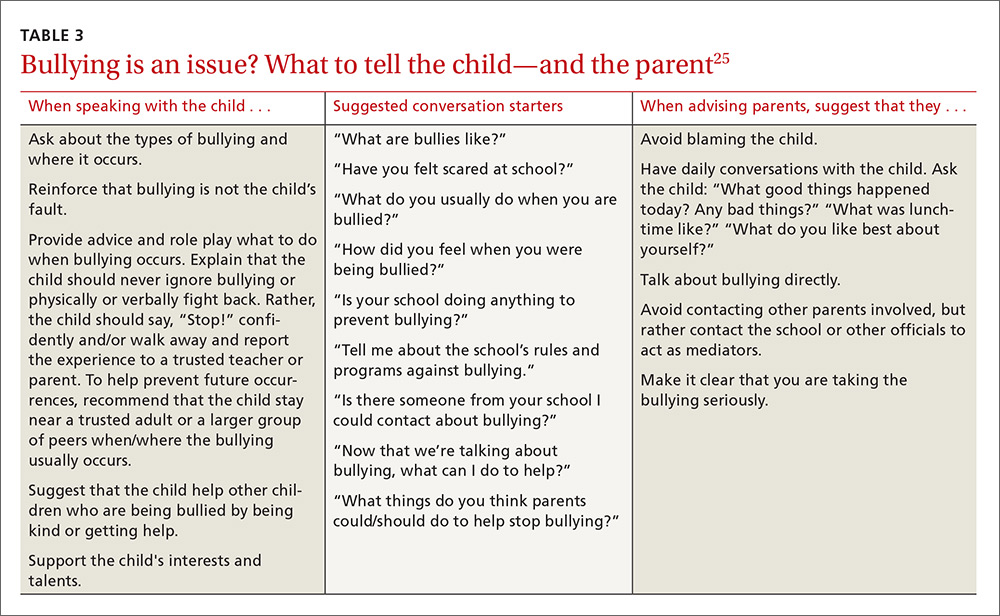

Effective discussion starters. Affirming the problem and its unacceptability, talking about the different types of bullying and where bullying may occur, and asking about patient perceptions of bullying can be effective discussion starters. FPs should help patients identify bullying, open lines of communication between children and their parents and between parents and other caregivers, and demonstrate respect and kindness in their approach to discussing the topic. Encourage children to speak with trusted adults when exposed to bullying. Talk to them about standing up to bullies (saying “stop” confidently or walking away from difficult situations) and staying safe by staying near adults or groups of peers when bullies are present (TABLE 325).

Empowering caregivers. Encourage parents to spend time each day talking with their child about the child’s time away from home (TABLE 325). Counsel parents/caregivers to expand their role. Knowing a child’s friends, encouraging the child academically, and increasing communication are all associated with lower risks of bullying.26 Similarly, parental oversight of Internet and social media use is associated with decreased participation in cyberbullying.27

In addition, the Positive Parenting telephone-based parenting education curriculum has been shown to decrease bullying, physical fighting, physical injuries, and victimization of children.28 The research-based, family strengthening program emphasizes 3 core elements of authoritative parenting: nurturance, discipline, and respect or granting of psychologic autonomy. The program entails 15- to 30-minute weekly phone conversations between parents and educators, as well as videos and a manual.

Are community programs in place—or are they needed?

Many schools have robust, state-mandated programs in place to identify bullying and provide support for students who are victims of bullying. (See “NJ’s harassment and bullying protocol: A case in point.”) Explaining this to victims and their families may help them come forward and seek assistance. FPs who want to advocate for their patients should start with local schools to support such programs and link students at risk with school counselors.

SIDEBAR

NJ's harassment and bullying protocol: A case in pointThere is no federal law that specifically applies to bullying, but all 50 states have some type of anti-bullying legislation on the books, and 40 of those states have additional detailed policies in place addressing the subject.1

New Jersey, for example, began enforcing one of the toughest harassment, intimidation, and bullying (HIB) protocols in the country back in September 20112 in the wake of the death of Rutgers University freshman Tyler Clementi, who committed suicide after his roommate allegedly shot a video of him with another man and posted it to the Internet.3 Among many other things, New Jersey’s legislation stipulates in its Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights4 that:

› Every school/district have plans in place that clearly define, prevent, prohibit, and promptly deal with acts of harassment, intimidation, or bullying, on school grounds, at school-sponsored functions, and on school buses.

› Plans must include a description of the type of behavior expected from each student and the consequences and remedial action for a person who commits an act of harassment, intimidation, or bullying. Student perpetrators may be suspended or expelled if convicted of any type of bullying, whether it be for teasing or something more severe.

› All school employees must act on any incidents of bullying reported to, or witnessed by, them and report such incidents on the same day to the school principal.

› Plans must include provisions and deadlines for investigating and resolving all matters in a timely fashion; investigations into allegations of bullying must be launched within one day.

› Every case of bullying must be reported to the state. Schools are graded by the state on their compliance with anti-bullying standards and policies and their handling of incidents.

› Schools must appoint safety teams made up of parents, teachers, and staff, and school personnel and students must receive extensive anti-bullying training.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Stopbullying.gov. Policies and laws. Available at: https://www.stopbullying.gov/laws/index.html.

Accessed January 5, 2017.

2. State of New Jersey Department of Education. An overview of amendments to laws on harassment, intimidation, and bullying. Available at: http://www.state.nj.us/education/students/safety/behavior/hib/overview.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.

3. Cohen A. Case study: Why New Jersey’s antibullying law should be a model for other states. Time. September 6, 2011. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2011/09/06/why-new-jerseys-antibullying-law-should-be-a-model-for-other-states/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. New Jersey Legislature. Anti-bullying Bill of Rights Act. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2010/Bills/PL10/122.PDF. Accessed January 5, 2017.

If programs are lacking in your community, there is much you can do to educate yourself about successful programs and advise local community organizations and schools about them. Among the most successful and well-studied interventions for thwarting the bullying epidemic have been school-based community ones. The most studied of these is the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP), which is based on 4 principles:1,29

- Adults both at home and at school should take a positive and encouraging interest in students.

- Unacceptable behavior should have strict and well-known limits.

- Sanctions should be applied consistently and should be non-hostile in nature.

- Adults both at home and in the educational environment should act as authorities.

In short, the program focuses on greater awareness and involvement on the part of adults, and employing measures at the school level (eg, surveys, better supervision during break and lunch times), the class level (eg, rules against bullying, regular class meetings with students), and the individual level (eg, serious talks with bullies, victims, parents of involved students).

Research has shown that the OBPP reduces bullying behaviors by as much as 50%, reduces vandalism and truancy, and reduces the number of new victims.12 Limits to the more widespread implementation of the OBPP have consisted mainly of the inability to appropriately train adults, including teachers and other school personnel in educational settings. Despite these limitations, the OBPP has been praised and endorsed by numerous groups, including the US Department of Justice.30

Other non-curricular, school-based programs exist, such as the School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). This program is a school-wide prevention strategy aimed at: 1) reducing behavior problems that lead to office discipline referrals and suspensions, and 2) changing perceptions of school safety. (For more information, see https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=385 and https://www.pbis.org/school/swpbis-for-beginners.)31

The research-based Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) Middle School Program (http://www.cfchildren.org/second-step/middle-school)32 focuses on the often difficult middle school years. The program helps schools teach and model essential communication, coping, and decision-making skills to help adolescents navigate around common pitfalls such as peer pressure, substance abuse, and bullying (both in-person and online). The program aims to reduce aggression and provide support for a more inclusive environment that helps students stay in school, make good choices, and experience social and academic success.

The Positive Action Program (https://www.positiveaction.net/research/primer),33 which is predicated on the notion that we feel good about ourselves when we do positive things, features scripted lessons and kits of materials (eg, posters, games, worksheets, puzzles) appropriate for each grade level.

CASE › Stacey’s visit to her FP’s office has presented several clues that she may be a victim of bullying. Her mild persistent asthma appears to no longer be as well controlled as it was in the past. Direct questioning has revealed that 2 girls at school have been making fun of Stacey when she uses her inhaled corticosteroid in the morning before class, so she has stopped using it. These same students are on her cheerleading team, so she quit the team to avoid them. Her school-related anxiety is so great that she no longer pays attention in math class and is constantly worried that something is being posted about her online.

Stacy’s FP responds to this information with a multifaceted approach. In the exam room, he screens Stacy for depression. While she is negative and denies any suicidal ideation, Stacy is clearly having anxiety, so the FP refers Stacey to a counselor at a local mental health clinic. With Stacy’s permission, the FP discusses the issue with her mother and they decide together with Stacy that she should talk to a teacher at school about the ongoing bullying. Because this was not the first time that the FP has heard this from a child in the community, the FP plans to attend an upcoming school board meeting to advocate for an evidence-based bullying prevention program to help curb the ongoing problem facing his patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert McClowry, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Jefferson Family Medicine Associates, 833 Chestnut East, 3rd Floor, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA, 19107-4414; [email protected].

1. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:124-134.

2. Lyznicki JM, McCaffree MA, Robinowitz CB, et al. Childhood bullying: implications for physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1723-1730.

3. Temkin D. All 50 states now have a bullying law. Now what? The Huffington Post. April 27, 2015. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/deborah-temkin/all-50-states-now-have-a_b_7153114.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. Anderson M, Kaufman J, Simon TR, et al. School-associated violent deaths in the United States, 1994-1999. JAMA. 2001;286:2695-2702.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS). Ten leading causes of death and injury. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

6. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094-2100.

7. Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—Role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics. 2009;124:393-402.

8. Klein DA, Myhre KK, Ahrendt DM. Bullying among adolescents: a challenge in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:87-92.

9. Lamb J, Pepler DJ, Craig W. Approach to bullying and victimization. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:356-360.

10. Spector ND, Kelly SF. Pediatrician’s role in screening and treatment: bullying, prediabetes, oral health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:661-670.

11. Gladden RM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hamburger ME, et al. Bullying surveillance among youths: uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Department of Education; 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

12. Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:1171-1190.

13. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

14. Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:S13-S20.

15. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):216-224.

16. US Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics (2015). Student reports of bullying and cyberbullying: results from the 2013 School Crime Supplement to the National Victimization Survey. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2015056. Accessed November 9, 2016.

17. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-174.

18. Van Cleave J, Davis MM. Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1212-e1219.

19. Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:733-738.

20. Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896-903.

21. Song LY, Singer MI, Anglin TM. Violence exposure and emotional trauma as contributors to adolescents’ violent behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:531-536.

22. Singer MI, Anglin TM, Song LY, et al. Adolescents’ exposure to violence and associated symptoms of psychological trauma. JAMA. 1995;273:477-482.

23. Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, et al. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1026-1031.

24. Waseem M, Ryan M, Foster CB, et al. Assessment and management of bullied children in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:389-398.

25. US Department of Health and Human Services. stopbullying.gov. Available at: https//www.stopbullying.gov. Accessed January 5, 2017.

26. Shetgiri R, Lin H, Avila RM, et al. Parental characteristics associated with bullying perpetration in US children aged 10 to 17 years. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2280-2286.

27. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:711-722.

28. Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, et al. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e392-e399.

29. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

30. Mihalic SF. Blueprints for Violence Prevention: Report. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2004.

31. Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:149-156.

32. Espelage DL, Low S, Polanin JR, et al. The impact of a middle school program to reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:180-186.

33. Lewis KM, Schure MB, Bavarian N, et al. Problem behavior and urban, low-income youth: a randomized controlled trial of positive action in Chicago. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:622-630.

CASE › Stacey, a 12-year-old girl with mild persistent asthma, presents to her family physician (FP) with her mother for her annual well visit. Stacey reports no complaints, but has visited twice recently for acute exacerbations of her asthma, which had previously been well-controlled. When reviewing her social history, Stacey reports that she started her second year of middle school 3 months ago. When asked if she enjoys school, Stacey looks down and says, “School is fine.” Her mother quickly adds that Stacey has quit the school cheerleading team—much to the coach’s dismay—and is having difficulty in her math class, a class in which she normally excels. Stacey appears embarrassed that her mother has brought these things up. Her mother says that at the beginning of the year, 2 girls began picking on Stacey, calling her names and making fun of her on social media and in front of other students.

For many years, bullying was trivialized. Some viewed it as a universal childhood experience; others considered it a rite of passage.1,2 It was not examined as a public health issue until the 1970s. In fact, no legislation addressing bullying or “peer abuse” existed in the United States until the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo, in 1999. Within 3 years of the Columbine tragedy, the number of state laws that mentioned bullying went from zero to 15; within 10 years of Columbine, 41 states had laws addressing bullying,1 and by 2015, every state, the District of Columbia, and some territories had a bullying law in place.3

As research and advocacy regarding bullying has grown, its impact on the health of children, adolescents, and even adults has become more apparent. In a 2001 study of school-associated violent deaths in the United States between 1994 and 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that among students, homicide perpetrators were more than twice as likely as homicide victims to have been bullied by peers.4 Given that homicide is the third leading cause of death in people ages 15 to 24,5 past exposure to bullying may be a significant contributing factor to mortality in this age group.4

In addition to a correlation with homicidal behavior, those involved in bullying—whether as the bully or victim—are at risk for a wide range of symptoms, conditions, and problems including poor psychosocial adjustment, depression, anxiety, suicide (the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 and 15-24 age groups5), academic decline, psychosomatic manifestations, fighting, alcohol use, smoking, and difficulty with the management of chronic diseases.6-10 Not only does being a victim of bullying have a direct impact on a child’s current mental and physical well-being, but it can have lasting psychological and behavioral effects that can follow children well into adulthood.7 The significant impact of bullying on individuals and society as a whole mandates a multifaceted approach that begins in your exam room. What follows is practical advice on screening, counseling, and working with schools and the community at large to curb the bullying epidemic.

Clarifying the problem: The CDC’s definition

Recognizing that varying definitions of bullying were being used in research studies that looked at violent or aggressive behaviors in youth, the CDC published a consensus statement in 2014 that proposed the following definition for bullying:11 any unwanted aggressive behavior by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. This expanded on an earlier definition by Olweus12,13 that also identified a longitudinal nature and power imbalance as key features.

Types of bullying. Direct bullying entails blatant attacks on a targeted young person, while indirect bullying involves communication with others about the targeted individual (eg, spreading harmful rumors). Bullying may be physical, verbal, or relational (eg, excluding someone from their usual social circle, denying friendship, the silent treatment, writing mean letters, eye rolling, etc.) and may involve damage to property. Boys tend toward more direct bullying behaviors, while girls more often engage in indirect bullying, which may be more challenging for both adults and other students to recognize.12,13 With increased use of technology and social media by adolescents, cyberbullying has become increasingly more prevalent, with its effects on adolescent health and academics being every bit as profound as those of traditional bullying.14

About 1 in 4/5 students suffer. The prevalence of bullying ranges by country and culture. The vast majority of early bullying research was conducted in Norway, which found that approximately 15% of students in elementary and secondary schools were involved in bullying in some capacity.12 In a study involving over 200,000 adolescents from 40 European countries, 26% of adolescents reported being involved in bullying, ranging from 8.6% to 45.2% for boys and 4.8% to 35.8% for girls.15 Variations in prevalence may be due to cultural differences in the acts of bullying or differences in interpretation of the term “bullying.”1,15

In the United States, a 2001 survey of more than 15,000 students in public and private schools (grades 6-10) asked the students about their involvement in bullying: 13% said they'd been a bully, 10.6% a victim, and 6.3% said they'd been both.6 There was no significant difference in the frequency of self-reported bullying among urban, suburban, or rural settings.

Despite efforts to educate the public about bullying and work with schools to intervene and prevent bullying, incidence remains largely unchanged. In 2013, the National Crime Victimization Survey reported that approximately 22% of adolescents ages 12 through 18 were victims of bullying.16 Similarly, the CDC's 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System reported that 20.2% of high school students experienced bullying on school property.17

Screening: Best practices

The FP’s role begins with screening children at risk for bullying (TABLE 118-22) or those whose complaints suggest that they may be victims of bullying.

Start screening when children enter elementary school

Given that providers’ time is limited for every patient visit, it is important to address bullying at times that are most likely to yield impactful results. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the topic of bullying be introduced at the 6-year-old well-child visit (a typical age for entry to elementary school).7 Views in the literature are inconsistent regarding when and how to address bullying at other time points. One approach is to pre-screen those with risk factors associated with bullying (TABLE 118-22), and to focus screening on those with warning signs of bullying, which include mood disorders, psychosomatic or behavioral symptoms, substance abuse, self-harm behaviors, suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, a decline in academic performance, and reports of school truancy. Parental concerns, such as when a child suddenly needs more money for lunch, is having aggressive outbursts, or is exhibiting unexplained physical injuries, should also be regarded as cues to screen.9

Screen patients in high-risk groups

A number of groups of children are at high risk for bullying and warrant targeted screening efforts.

- Children with special health needs. Research has shown that children with special health needs are at increased risk for being bullied.18 In fact, the presence of a chronic disease may increase the risk for bullying, and bullying often negatively impacts chronic disease management. As a result, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion with patients who have a chronic disease and who are not responding as expected to medical management or who experience deterioration after being previously well-controlled.18

- Children who are under- or overweight. Similarly, bullying based on a child's weight is a phenomenon that has been recognized to have a significant impact on children’s emotional health.19

- Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ peers to attempt suicide when exposed to a hostile social environment, such as that created by bullying.20

Screening need not be complicated

One screening approach is simply to ask patients, “Are you being bullied?” followed by such questions as, “How often are you bullied?” or “How long have you been bullied?” Asking about the setting of the bullying (Does it happen at school? Traveling to/from school? Online?) and other details may help guide interventions and the provision of resources.9 Another approach is to provide patients with some type of written survey (see TABLE 223 for an example) to encourage responses that patients might be reluctant to disclose verbally.23,24 (See “Barriers to screening.")

SIDEBAR

Barriers to screeningScreening for any condition presupposes a response. Ideally, family physicians should be prepared to provide basic counseling, resources, and, if necessary, treatment, if a patient screens positive for bullying. But screening for violence or bullying can be difficult, and evidence-based guidelines for screening and intervention are lacking, leaving many primary care practitioners feeling ill-equipped to meaningfully respond.

One study of the use of a screening tool aimed at intimate partner violence (IPV) showed that even with the availability of a screening tool, health care providers’ use of the tool was inconsistent and referral practices were ineffective.1 Providers cited the following limiting factors in screening for IPV: 1) a lack of immediate referral availability, 2) a lack of time during the office visit, and 3) a lack of confidence in the ability to screen.1 These same issues may be barriers to screening for bullying.

1. Ramachandran DV, Covarrubias L, Watson C, et al. How you screen is as important as whether you screen: a qualitative analysis of violence screening practices in reproductive health clinics. J Community Health. 2013;38:856-863.

Provider and parental interventions

Interventions often entail counseling the patient and the family about bullying and its effects, empowering victims and their caregivers, and screening for bullying comorbidities and correlates.2 Refer patients to behavioral health specialists when there is evidence of pervasive effects on mood, behavior, or social development, but keep in mind that counseling can begin in your own exam room.

Effective discussion starters. Affirming the problem and its unacceptability, talking about the different types of bullying and where bullying may occur, and asking about patient perceptions of bullying can be effective discussion starters. FPs should help patients identify bullying, open lines of communication between children and their parents and between parents and other caregivers, and demonstrate respect and kindness in their approach to discussing the topic. Encourage children to speak with trusted adults when exposed to bullying. Talk to them about standing up to bullies (saying “stop” confidently or walking away from difficult situations) and staying safe by staying near adults or groups of peers when bullies are present (TABLE 325).

Empowering caregivers. Encourage parents to spend time each day talking with their child about the child’s time away from home (TABLE 325). Counsel parents/caregivers to expand their role. Knowing a child’s friends, encouraging the child academically, and increasing communication are all associated with lower risks of bullying.26 Similarly, parental oversight of Internet and social media use is associated with decreased participation in cyberbullying.27

In addition, the Positive Parenting telephone-based parenting education curriculum has been shown to decrease bullying, physical fighting, physical injuries, and victimization of children.28 The research-based, family strengthening program emphasizes 3 core elements of authoritative parenting: nurturance, discipline, and respect or granting of psychologic autonomy. The program entails 15- to 30-minute weekly phone conversations between parents and educators, as well as videos and a manual.

Are community programs in place—or are they needed?

Many schools have robust, state-mandated programs in place to identify bullying and provide support for students who are victims of bullying. (See “NJ’s harassment and bullying protocol: A case in point.”) Explaining this to victims and their families may help them come forward and seek assistance. FPs who want to advocate for their patients should start with local schools to support such programs and link students at risk with school counselors.

SIDEBAR

NJ's harassment and bullying protocol: A case in pointThere is no federal law that specifically applies to bullying, but all 50 states have some type of anti-bullying legislation on the books, and 40 of those states have additional detailed policies in place addressing the subject.1

New Jersey, for example, began enforcing one of the toughest harassment, intimidation, and bullying (HIB) protocols in the country back in September 20112 in the wake of the death of Rutgers University freshman Tyler Clementi, who committed suicide after his roommate allegedly shot a video of him with another man and posted it to the Internet.3 Among many other things, New Jersey’s legislation stipulates in its Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights4 that:

› Every school/district have plans in place that clearly define, prevent, prohibit, and promptly deal with acts of harassment, intimidation, or bullying, on school grounds, at school-sponsored functions, and on school buses.

› Plans must include a description of the type of behavior expected from each student and the consequences and remedial action for a person who commits an act of harassment, intimidation, or bullying. Student perpetrators may be suspended or expelled if convicted of any type of bullying, whether it be for teasing or something more severe.

› All school employees must act on any incidents of bullying reported to, or witnessed by, them and report such incidents on the same day to the school principal.

› Plans must include provisions and deadlines for investigating and resolving all matters in a timely fashion; investigations into allegations of bullying must be launched within one day.

› Every case of bullying must be reported to the state. Schools are graded by the state on their compliance with anti-bullying standards and policies and their handling of incidents.

› Schools must appoint safety teams made up of parents, teachers, and staff, and school personnel and students must receive extensive anti-bullying training.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Stopbullying.gov. Policies and laws. Available at: https://www.stopbullying.gov/laws/index.html.

Accessed January 5, 2017.

2. State of New Jersey Department of Education. An overview of amendments to laws on harassment, intimidation, and bullying. Available at: http://www.state.nj.us/education/students/safety/behavior/hib/overview.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.

3. Cohen A. Case study: Why New Jersey’s antibullying law should be a model for other states. Time. September 6, 2011. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2011/09/06/why-new-jerseys-antibullying-law-should-be-a-model-for-other-states/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. New Jersey Legislature. Anti-bullying Bill of Rights Act. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2010/Bills/PL10/122.PDF. Accessed January 5, 2017.

If programs are lacking in your community, there is much you can do to educate yourself about successful programs and advise local community organizations and schools about them. Among the most successful and well-studied interventions for thwarting the bullying epidemic have been school-based community ones. The most studied of these is the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP), which is based on 4 principles:1,29

- Adults both at home and at school should take a positive and encouraging interest in students.

- Unacceptable behavior should have strict and well-known limits.

- Sanctions should be applied consistently and should be non-hostile in nature.

- Adults both at home and in the educational environment should act as authorities.

In short, the program focuses on greater awareness and involvement on the part of adults, and employing measures at the school level (eg, surveys, better supervision during break and lunch times), the class level (eg, rules against bullying, regular class meetings with students), and the individual level (eg, serious talks with bullies, victims, parents of involved students).

Research has shown that the OBPP reduces bullying behaviors by as much as 50%, reduces vandalism and truancy, and reduces the number of new victims.12 Limits to the more widespread implementation of the OBPP have consisted mainly of the inability to appropriately train adults, including teachers and other school personnel in educational settings. Despite these limitations, the OBPP has been praised and endorsed by numerous groups, including the US Department of Justice.30

Other non-curricular, school-based programs exist, such as the School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). This program is a school-wide prevention strategy aimed at: 1) reducing behavior problems that lead to office discipline referrals and suspensions, and 2) changing perceptions of school safety. (For more information, see https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=385 and https://www.pbis.org/school/swpbis-for-beginners.)31

The research-based Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) Middle School Program (http://www.cfchildren.org/second-step/middle-school)32 focuses on the often difficult middle school years. The program helps schools teach and model essential communication, coping, and decision-making skills to help adolescents navigate around common pitfalls such as peer pressure, substance abuse, and bullying (both in-person and online). The program aims to reduce aggression and provide support for a more inclusive environment that helps students stay in school, make good choices, and experience social and academic success.

The Positive Action Program (https://www.positiveaction.net/research/primer),33 which is predicated on the notion that we feel good about ourselves when we do positive things, features scripted lessons and kits of materials (eg, posters, games, worksheets, puzzles) appropriate for each grade level.

CASE › Stacey’s visit to her FP’s office has presented several clues that she may be a victim of bullying. Her mild persistent asthma appears to no longer be as well controlled as it was in the past. Direct questioning has revealed that 2 girls at school have been making fun of Stacey when she uses her inhaled corticosteroid in the morning before class, so she has stopped using it. These same students are on her cheerleading team, so she quit the team to avoid them. Her school-related anxiety is so great that she no longer pays attention in math class and is constantly worried that something is being posted about her online.

Stacy’s FP responds to this information with a multifaceted approach. In the exam room, he screens Stacy for depression. While she is negative and denies any suicidal ideation, Stacy is clearly having anxiety, so the FP refers Stacey to a counselor at a local mental health clinic. With Stacy’s permission, the FP discusses the issue with her mother and they decide together with Stacy that she should talk to a teacher at school about the ongoing bullying. Because this was not the first time that the FP has heard this from a child in the community, the FP plans to attend an upcoming school board meeting to advocate for an evidence-based bullying prevention program to help curb the ongoing problem facing his patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert McClowry, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Jefferson Family Medicine Associates, 833 Chestnut East, 3rd Floor, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA, 19107-4414; [email protected].

CASE › Stacey, a 12-year-old girl with mild persistent asthma, presents to her family physician (FP) with her mother for her annual well visit. Stacey reports no complaints, but has visited twice recently for acute exacerbations of her asthma, which had previously been well-controlled. When reviewing her social history, Stacey reports that she started her second year of middle school 3 months ago. When asked if she enjoys school, Stacey looks down and says, “School is fine.” Her mother quickly adds that Stacey has quit the school cheerleading team—much to the coach’s dismay—and is having difficulty in her math class, a class in which she normally excels. Stacey appears embarrassed that her mother has brought these things up. Her mother says that at the beginning of the year, 2 girls began picking on Stacey, calling her names and making fun of her on social media and in front of other students.

For many years, bullying was trivialized. Some viewed it as a universal childhood experience; others considered it a rite of passage.1,2 It was not examined as a public health issue until the 1970s. In fact, no legislation addressing bullying or “peer abuse” existed in the United States until the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo, in 1999. Within 3 years of the Columbine tragedy, the number of state laws that mentioned bullying went from zero to 15; within 10 years of Columbine, 41 states had laws addressing bullying,1 and by 2015, every state, the District of Columbia, and some territories had a bullying law in place.3

As research and advocacy regarding bullying has grown, its impact on the health of children, adolescents, and even adults has become more apparent. In a 2001 study of school-associated violent deaths in the United States between 1994 and 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that among students, homicide perpetrators were more than twice as likely as homicide victims to have been bullied by peers.4 Given that homicide is the third leading cause of death in people ages 15 to 24,5 past exposure to bullying may be a significant contributing factor to mortality in this age group.4

In addition to a correlation with homicidal behavior, those involved in bullying—whether as the bully or victim—are at risk for a wide range of symptoms, conditions, and problems including poor psychosocial adjustment, depression, anxiety, suicide (the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 and 15-24 age groups5), academic decline, psychosomatic manifestations, fighting, alcohol use, smoking, and difficulty with the management of chronic diseases.6-10 Not only does being a victim of bullying have a direct impact on a child’s current mental and physical well-being, but it can have lasting psychological and behavioral effects that can follow children well into adulthood.7 The significant impact of bullying on individuals and society as a whole mandates a multifaceted approach that begins in your exam room. What follows is practical advice on screening, counseling, and working with schools and the community at large to curb the bullying epidemic.

Clarifying the problem: The CDC’s definition

Recognizing that varying definitions of bullying were being used in research studies that looked at violent or aggressive behaviors in youth, the CDC published a consensus statement in 2014 that proposed the following definition for bullying:11 any unwanted aggressive behavior by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. This expanded on an earlier definition by Olweus12,13 that also identified a longitudinal nature and power imbalance as key features.

Types of bullying. Direct bullying entails blatant attacks on a targeted young person, while indirect bullying involves communication with others about the targeted individual (eg, spreading harmful rumors). Bullying may be physical, verbal, or relational (eg, excluding someone from their usual social circle, denying friendship, the silent treatment, writing mean letters, eye rolling, etc.) and may involve damage to property. Boys tend toward more direct bullying behaviors, while girls more often engage in indirect bullying, which may be more challenging for both adults and other students to recognize.12,13 With increased use of technology and social media by adolescents, cyberbullying has become increasingly more prevalent, with its effects on adolescent health and academics being every bit as profound as those of traditional bullying.14

About 1 in 4/5 students suffer. The prevalence of bullying ranges by country and culture. The vast majority of early bullying research was conducted in Norway, which found that approximately 15% of students in elementary and secondary schools were involved in bullying in some capacity.12 In a study involving over 200,000 adolescents from 40 European countries, 26% of adolescents reported being involved in bullying, ranging from 8.6% to 45.2% for boys and 4.8% to 35.8% for girls.15 Variations in prevalence may be due to cultural differences in the acts of bullying or differences in interpretation of the term “bullying.”1,15

In the United States, a 2001 survey of more than 15,000 students in public and private schools (grades 6-10) asked the students about their involvement in bullying: 13% said they'd been a bully, 10.6% a victim, and 6.3% said they'd been both.6 There was no significant difference in the frequency of self-reported bullying among urban, suburban, or rural settings.

Despite efforts to educate the public about bullying and work with schools to intervene and prevent bullying, incidence remains largely unchanged. In 2013, the National Crime Victimization Survey reported that approximately 22% of adolescents ages 12 through 18 were victims of bullying.16 Similarly, the CDC's 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System reported that 20.2% of high school students experienced bullying on school property.17

Screening: Best practices

The FP’s role begins with screening children at risk for bullying (TABLE 118-22) or those whose complaints suggest that they may be victims of bullying.

Start screening when children enter elementary school

Given that providers’ time is limited for every patient visit, it is important to address bullying at times that are most likely to yield impactful results. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the topic of bullying be introduced at the 6-year-old well-child visit (a typical age for entry to elementary school).7 Views in the literature are inconsistent regarding when and how to address bullying at other time points. One approach is to pre-screen those with risk factors associated with bullying (TABLE 118-22), and to focus screening on those with warning signs of bullying, which include mood disorders, psychosomatic or behavioral symptoms, substance abuse, self-harm behaviors, suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, a decline in academic performance, and reports of school truancy. Parental concerns, such as when a child suddenly needs more money for lunch, is having aggressive outbursts, or is exhibiting unexplained physical injuries, should also be regarded as cues to screen.9

Screen patients in high-risk groups

A number of groups of children are at high risk for bullying and warrant targeted screening efforts.

- Children with special health needs. Research has shown that children with special health needs are at increased risk for being bullied.18 In fact, the presence of a chronic disease may increase the risk for bullying, and bullying often negatively impacts chronic disease management. As a result, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion with patients who have a chronic disease and who are not responding as expected to medical management or who experience deterioration after being previously well-controlled.18

- Children who are under- or overweight. Similarly, bullying based on a child's weight is a phenomenon that has been recognized to have a significant impact on children’s emotional health.19

- Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ peers to attempt suicide when exposed to a hostile social environment, such as that created by bullying.20

Screening need not be complicated

One screening approach is simply to ask patients, “Are you being bullied?” followed by such questions as, “How often are you bullied?” or “How long have you been bullied?” Asking about the setting of the bullying (Does it happen at school? Traveling to/from school? Online?) and other details may help guide interventions and the provision of resources.9 Another approach is to provide patients with some type of written survey (see TABLE 223 for an example) to encourage responses that patients might be reluctant to disclose verbally.23,24 (See “Barriers to screening.")

SIDEBAR

Barriers to screeningScreening for any condition presupposes a response. Ideally, family physicians should be prepared to provide basic counseling, resources, and, if necessary, treatment, if a patient screens positive for bullying. But screening for violence or bullying can be difficult, and evidence-based guidelines for screening and intervention are lacking, leaving many primary care practitioners feeling ill-equipped to meaningfully respond.

One study of the use of a screening tool aimed at intimate partner violence (IPV) showed that even with the availability of a screening tool, health care providers’ use of the tool was inconsistent and referral practices were ineffective.1 Providers cited the following limiting factors in screening for IPV: 1) a lack of immediate referral availability, 2) a lack of time during the office visit, and 3) a lack of confidence in the ability to screen.1 These same issues may be barriers to screening for bullying.

1. Ramachandran DV, Covarrubias L, Watson C, et al. How you screen is as important as whether you screen: a qualitative analysis of violence screening practices in reproductive health clinics. J Community Health. 2013;38:856-863.

Provider and parental interventions

Interventions often entail counseling the patient and the family about bullying and its effects, empowering victims and their caregivers, and screening for bullying comorbidities and correlates.2 Refer patients to behavioral health specialists when there is evidence of pervasive effects on mood, behavior, or social development, but keep in mind that counseling can begin in your own exam room.

Effective discussion starters. Affirming the problem and its unacceptability, talking about the different types of bullying and where bullying may occur, and asking about patient perceptions of bullying can be effective discussion starters. FPs should help patients identify bullying, open lines of communication between children and their parents and between parents and other caregivers, and demonstrate respect and kindness in their approach to discussing the topic. Encourage children to speak with trusted adults when exposed to bullying. Talk to them about standing up to bullies (saying “stop” confidently or walking away from difficult situations) and staying safe by staying near adults or groups of peers when bullies are present (TABLE 325).

Empowering caregivers. Encourage parents to spend time each day talking with their child about the child’s time away from home (TABLE 325). Counsel parents/caregivers to expand their role. Knowing a child’s friends, encouraging the child academically, and increasing communication are all associated with lower risks of bullying.26 Similarly, parental oversight of Internet and social media use is associated with decreased participation in cyberbullying.27

In addition, the Positive Parenting telephone-based parenting education curriculum has been shown to decrease bullying, physical fighting, physical injuries, and victimization of children.28 The research-based, family strengthening program emphasizes 3 core elements of authoritative parenting: nurturance, discipline, and respect or granting of psychologic autonomy. The program entails 15- to 30-minute weekly phone conversations between parents and educators, as well as videos and a manual.

Are community programs in place—or are they needed?

Many schools have robust, state-mandated programs in place to identify bullying and provide support for students who are victims of bullying. (See “NJ’s harassment and bullying protocol: A case in point.”) Explaining this to victims and their families may help them come forward and seek assistance. FPs who want to advocate for their patients should start with local schools to support such programs and link students at risk with school counselors.

SIDEBAR

NJ's harassment and bullying protocol: A case in pointThere is no federal law that specifically applies to bullying, but all 50 states have some type of anti-bullying legislation on the books, and 40 of those states have additional detailed policies in place addressing the subject.1

New Jersey, for example, began enforcing one of the toughest harassment, intimidation, and bullying (HIB) protocols in the country back in September 20112 in the wake of the death of Rutgers University freshman Tyler Clementi, who committed suicide after his roommate allegedly shot a video of him with another man and posted it to the Internet.3 Among many other things, New Jersey’s legislation stipulates in its Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights4 that:

› Every school/district have plans in place that clearly define, prevent, prohibit, and promptly deal with acts of harassment, intimidation, or bullying, on school grounds, at school-sponsored functions, and on school buses.

› Plans must include a description of the type of behavior expected from each student and the consequences and remedial action for a person who commits an act of harassment, intimidation, or bullying. Student perpetrators may be suspended or expelled if convicted of any type of bullying, whether it be for teasing or something more severe.

› All school employees must act on any incidents of bullying reported to, or witnessed by, them and report such incidents on the same day to the school principal.

› Plans must include provisions and deadlines for investigating and resolving all matters in a timely fashion; investigations into allegations of bullying must be launched within one day.

› Every case of bullying must be reported to the state. Schools are graded by the state on their compliance with anti-bullying standards and policies and their handling of incidents.

› Schools must appoint safety teams made up of parents, teachers, and staff, and school personnel and students must receive extensive anti-bullying training.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Stopbullying.gov. Policies and laws. Available at: https://www.stopbullying.gov/laws/index.html.

Accessed January 5, 2017.

2. State of New Jersey Department of Education. An overview of amendments to laws on harassment, intimidation, and bullying. Available at: http://www.state.nj.us/education/students/safety/behavior/hib/overview.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2017.

3. Cohen A. Case study: Why New Jersey’s antibullying law should be a model for other states. Time. September 6, 2011. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2011/09/06/why-new-jerseys-antibullying-law-should-be-a-model-for-other-states/. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. New Jersey Legislature. Anti-bullying Bill of Rights Act. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2010/Bills/PL10/122.PDF. Accessed January 5, 2017.

If programs are lacking in your community, there is much you can do to educate yourself about successful programs and advise local community organizations and schools about them. Among the most successful and well-studied interventions for thwarting the bullying epidemic have been school-based community ones. The most studied of these is the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP), which is based on 4 principles:1,29

- Adults both at home and at school should take a positive and encouraging interest in students.

- Unacceptable behavior should have strict and well-known limits.

- Sanctions should be applied consistently and should be non-hostile in nature.

- Adults both at home and in the educational environment should act as authorities.

In short, the program focuses on greater awareness and involvement on the part of adults, and employing measures at the school level (eg, surveys, better supervision during break and lunch times), the class level (eg, rules against bullying, regular class meetings with students), and the individual level (eg, serious talks with bullies, victims, parents of involved students).

Research has shown that the OBPP reduces bullying behaviors by as much as 50%, reduces vandalism and truancy, and reduces the number of new victims.12 Limits to the more widespread implementation of the OBPP have consisted mainly of the inability to appropriately train adults, including teachers and other school personnel in educational settings. Despite these limitations, the OBPP has been praised and endorsed by numerous groups, including the US Department of Justice.30

Other non-curricular, school-based programs exist, such as the School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). This program is a school-wide prevention strategy aimed at: 1) reducing behavior problems that lead to office discipline referrals and suspensions, and 2) changing perceptions of school safety. (For more information, see https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=385 and https://www.pbis.org/school/swpbis-for-beginners.)31

The research-based Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) Middle School Program (http://www.cfchildren.org/second-step/middle-school)32 focuses on the often difficult middle school years. The program helps schools teach and model essential communication, coping, and decision-making skills to help adolescents navigate around common pitfalls such as peer pressure, substance abuse, and bullying (both in-person and online). The program aims to reduce aggression and provide support for a more inclusive environment that helps students stay in school, make good choices, and experience social and academic success.

The Positive Action Program (https://www.positiveaction.net/research/primer),33 which is predicated on the notion that we feel good about ourselves when we do positive things, features scripted lessons and kits of materials (eg, posters, games, worksheets, puzzles) appropriate for each grade level.

CASE › Stacey’s visit to her FP’s office has presented several clues that she may be a victim of bullying. Her mild persistent asthma appears to no longer be as well controlled as it was in the past. Direct questioning has revealed that 2 girls at school have been making fun of Stacey when she uses her inhaled corticosteroid in the morning before class, so she has stopped using it. These same students are on her cheerleading team, so she quit the team to avoid them. Her school-related anxiety is so great that she no longer pays attention in math class and is constantly worried that something is being posted about her online.

Stacy’s FP responds to this information with a multifaceted approach. In the exam room, he screens Stacy for depression. While she is negative and denies any suicidal ideation, Stacy is clearly having anxiety, so the FP refers Stacey to a counselor at a local mental health clinic. With Stacy’s permission, the FP discusses the issue with her mother and they decide together with Stacy that she should talk to a teacher at school about the ongoing bullying. Because this was not the first time that the FP has heard this from a child in the community, the FP plans to attend an upcoming school board meeting to advocate for an evidence-based bullying prevention program to help curb the ongoing problem facing his patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert McClowry, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Jefferson Family Medicine Associates, 833 Chestnut East, 3rd Floor, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA, 19107-4414; [email protected].

1. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:124-134.

2. Lyznicki JM, McCaffree MA, Robinowitz CB, et al. Childhood bullying: implications for physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1723-1730.

3. Temkin D. All 50 states now have a bullying law. Now what? The Huffington Post. April 27, 2015. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/deborah-temkin/all-50-states-now-have-a_b_7153114.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. Anderson M, Kaufman J, Simon TR, et al. School-associated violent deaths in the United States, 1994-1999. JAMA. 2001;286:2695-2702.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS). Ten leading causes of death and injury. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

6. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094-2100.

7. Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—Role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics. 2009;124:393-402.

8. Klein DA, Myhre KK, Ahrendt DM. Bullying among adolescents: a challenge in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:87-92.

9. Lamb J, Pepler DJ, Craig W. Approach to bullying and victimization. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:356-360.

10. Spector ND, Kelly SF. Pediatrician’s role in screening and treatment: bullying, prediabetes, oral health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:661-670.

11. Gladden RM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hamburger ME, et al. Bullying surveillance among youths: uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Department of Education; 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

12. Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:1171-1190.

13. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

14. Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:S13-S20.

15. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):216-224.

16. US Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics (2015). Student reports of bullying and cyberbullying: results from the 2013 School Crime Supplement to the National Victimization Survey. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2015056. Accessed November 9, 2016.

17. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-174.

18. Van Cleave J, Davis MM. Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1212-e1219.

19. Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:733-738.

20. Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896-903.

21. Song LY, Singer MI, Anglin TM. Violence exposure and emotional trauma as contributors to adolescents’ violent behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:531-536.

22. Singer MI, Anglin TM, Song LY, et al. Adolescents’ exposure to violence and associated symptoms of psychological trauma. JAMA. 1995;273:477-482.

23. Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, et al. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1026-1031.

24. Waseem M, Ryan M, Foster CB, et al. Assessment and management of bullied children in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:389-398.

25. US Department of Health and Human Services. stopbullying.gov. Available at: https//www.stopbullying.gov. Accessed January 5, 2017.

26. Shetgiri R, Lin H, Avila RM, et al. Parental characteristics associated with bullying perpetration in US children aged 10 to 17 years. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2280-2286.

27. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:711-722.

28. Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, et al. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e392-e399.

29. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

30. Mihalic SF. Blueprints for Violence Prevention: Report. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2004.

31. Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:149-156.

32. Espelage DL, Low S, Polanin JR, et al. The impact of a middle school program to reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:180-186.

33. Lewis KM, Schure MB, Bavarian N, et al. Problem behavior and urban, low-income youth: a randomized controlled trial of positive action in Chicago. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:622-630.

1. Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:124-134.

2. Lyznicki JM, McCaffree MA, Robinowitz CB, et al. Childhood bullying: implications for physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1723-1730.

3. Temkin D. All 50 states now have a bullying law. Now what? The Huffington Post. April 27, 2015. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/deborah-temkin/all-50-states-now-have-a_b_7153114.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

4. Anderson M, Kaufman J, Simon TR, et al. School-associated violent deaths in the United States, 1994-1999. JAMA. 2001;286:2695-2702.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS). Ten leading causes of death and injury. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html. Accessed January 5, 2017.

6. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094-2100.

7. Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—Role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics. 2009;124:393-402.

8. Klein DA, Myhre KK, Ahrendt DM. Bullying among adolescents: a challenge in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:87-92.

9. Lamb J, Pepler DJ, Craig W. Approach to bullying and victimization. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:356-360.

10. Spector ND, Kelly SF. Pediatrician’s role in screening and treatment: bullying, prediabetes, oral health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:661-670.

11. Gladden RM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hamburger ME, et al. Bullying surveillance among youths: uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Department of Education; 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

12. Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:1171-1190.

13. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

14. Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:S13-S20.

15. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):216-224.

16. US Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics (2015). Student reports of bullying and cyberbullying: results from the 2013 School Crime Supplement to the National Victimization Survey. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2015056. Accessed November 9, 2016.

17. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-174.

18. Van Cleave J, Davis MM. Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1212-e1219.

19. Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:733-738.

20. Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896-903.

21. Song LY, Singer MI, Anglin TM. Violence exposure and emotional trauma as contributors to adolescents’ violent behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:531-536.

22. Singer MI, Anglin TM, Song LY, et al. Adolescents’ exposure to violence and associated symptoms of psychological trauma. JAMA. 1995;273:477-482.

23. Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, et al. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1026-1031.

24. Waseem M, Ryan M, Foster CB, et al. Assessment and management of bullied children in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:389-398.

25. US Department of Health and Human Services. stopbullying.gov. Available at: https//www.stopbullying.gov. Accessed January 5, 2017.

26. Shetgiri R, Lin H, Avila RM, et al. Parental characteristics associated with bullying perpetration in US children aged 10 to 17 years. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2280-2286.

27. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:711-722.

28. Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, et al. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e392-e399.

29. Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. Eur J Psychol Educ. 1997;12:495-510.

30. Mihalic SF. Blueprints for Violence Prevention: Report. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2004.

31. Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:149-156.

32. Espelage DL, Low S, Polanin JR, et al. The impact of a middle school program to reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:180-186.

33. Lewis KM, Schure MB, Bavarian N, et al. Problem behavior and urban, low-income youth: a randomized controlled trial of positive action in Chicago. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:622-630.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Suspect bullying when children with chronic conditions that were stable begin deteriorating for unexplained reasons or when children become non-adherent to medication regimens. C

› Empower not only patients, but also parents/caregivers, to take action and deter bullying behaviors. B

› Support school-based and community-oriented intervention programs, which have been shown to be among the most effective strategies for curbing bullying. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence