User login

Gina Henderson has been editor of Clinical Psychiatry News since 2002. Before that, she worked as an editor at Emerge magazine and The Kansas City Star, and as an instructor/assistant professor at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, in Columbia. Gina graduated cum laude from Washington University in St. Louis, and earned a master's degree in journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, Chicago.

COVID-19 & Mental Health

On Thursday, April 23, 2020, MDedge Psychiatry hosted a Twitter conversation at #MDedgeChats on COVID-19 and mental health.

Two psychiatrists affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, Dinah Miller, MD (@shrinkrapdinah), and Elizabeth Ryznar, MD (@RyznarMD), hosted the conversation. Throughout the conversation several themes emerged. One is that COVID-19 illustrates the connections between housing and health, and another is that stigma tied to being COVID positive is leading to suicidality, particularly in Haiti. The discussants also talked about the importance of self-care.

Questions asked during the Twitter chat:

- How are your pre-pandemic patients doing during this crisis?

- How has COVID-19 affected inpatient and outpatient care for you?

- How are our most vulnerable populations being affected by COVID-19?

- How are you doing personally and professionally as medical professionals during the pandemic?

- What psychiatric manifestations are you seeing in your patients who have had COVID-19?

The following is an edited version of the discussion. For the full experience, visit our Twitter archive, you can still join the conversation.

Some experts are predicting that the magnitude of the mental health fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will be profound. They also have concerns that physical distancing and increased unemployment forced by the pandemic will lead to a rise in suicide risk, particularly for at-risk populations.1

For psychiatric patients, COVID-19 is expected to leave behind higher levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia.2

And for health care workers on the front lines, the mental health toll could lead to stress, burnout, and worse.

Clinicians are also dealing with shortages of PPE and medical equipment, worrying about their safety and that of their families, while trying to save lives amid great uncertainty about SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Most recently an emergency department physician in New York who was recovering from COVID-19 herself reportedly recently ended her own life, according to her father, who is a physician.

As Dr. Sarah Candler said in a previous twitter chat with MDedge Internal Medicine, “Good doctors take care of themselves, too.” Be kind to yourself during this global crisis.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is always available at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Resources

- Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic

- Brief examines the COVID-19 crisis’ implications for Americans’ mental health

- COVID-19: Helping health care workers on the front lines

- Overcoming COVID-related stress

- Confessions of an outpatient psychiatrist during the pandemic

- Psychiatric patients may be among the hardest hit

- Experts hasten to head off mental health crisis

- Podcast: Physician Suicide

1Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20):30171-1.

2Brain, Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 27. doi: 10.10116/j.bbi.2020.04.069).

On Thursday, April 23, 2020, MDedge Psychiatry hosted a Twitter conversation at #MDedgeChats on COVID-19 and mental health.

Two psychiatrists affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, Dinah Miller, MD (@shrinkrapdinah), and Elizabeth Ryznar, MD (@RyznarMD), hosted the conversation. Throughout the conversation several themes emerged. One is that COVID-19 illustrates the connections between housing and health, and another is that stigma tied to being COVID positive is leading to suicidality, particularly in Haiti. The discussants also talked about the importance of self-care.

Questions asked during the Twitter chat:

- How are your pre-pandemic patients doing during this crisis?

- How has COVID-19 affected inpatient and outpatient care for you?

- How are our most vulnerable populations being affected by COVID-19?

- How are you doing personally and professionally as medical professionals during the pandemic?

- What psychiatric manifestations are you seeing in your patients who have had COVID-19?

The following is an edited version of the discussion. For the full experience, visit our Twitter archive, you can still join the conversation.

Some experts are predicting that the magnitude of the mental health fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will be profound. They also have concerns that physical distancing and increased unemployment forced by the pandemic will lead to a rise in suicide risk, particularly for at-risk populations.1

For psychiatric patients, COVID-19 is expected to leave behind higher levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia.2

And for health care workers on the front lines, the mental health toll could lead to stress, burnout, and worse.

Clinicians are also dealing with shortages of PPE and medical equipment, worrying about their safety and that of their families, while trying to save lives amid great uncertainty about SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Most recently an emergency department physician in New York who was recovering from COVID-19 herself reportedly recently ended her own life, according to her father, who is a physician.

As Dr. Sarah Candler said in a previous twitter chat with MDedge Internal Medicine, “Good doctors take care of themselves, too.” Be kind to yourself during this global crisis.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is always available at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Resources

- Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic

- Brief examines the COVID-19 crisis’ implications for Americans’ mental health

- COVID-19: Helping health care workers on the front lines

- Overcoming COVID-related stress

- Confessions of an outpatient psychiatrist during the pandemic

- Psychiatric patients may be among the hardest hit

- Experts hasten to head off mental health crisis

- Podcast: Physician Suicide

1Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20):30171-1.

2Brain, Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 27. doi: 10.10116/j.bbi.2020.04.069).

On Thursday, April 23, 2020, MDedge Psychiatry hosted a Twitter conversation at #MDedgeChats on COVID-19 and mental health.

Two psychiatrists affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, Dinah Miller, MD (@shrinkrapdinah), and Elizabeth Ryznar, MD (@RyznarMD), hosted the conversation. Throughout the conversation several themes emerged. One is that COVID-19 illustrates the connections between housing and health, and another is that stigma tied to being COVID positive is leading to suicidality, particularly in Haiti. The discussants also talked about the importance of self-care.

Questions asked during the Twitter chat:

- How are your pre-pandemic patients doing during this crisis?

- How has COVID-19 affected inpatient and outpatient care for you?

- How are our most vulnerable populations being affected by COVID-19?

- How are you doing personally and professionally as medical professionals during the pandemic?

- What psychiatric manifestations are you seeing in your patients who have had COVID-19?

The following is an edited version of the discussion. For the full experience, visit our Twitter archive, you can still join the conversation.

Some experts are predicting that the magnitude of the mental health fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will be profound. They also have concerns that physical distancing and increased unemployment forced by the pandemic will lead to a rise in suicide risk, particularly for at-risk populations.1

For psychiatric patients, COVID-19 is expected to leave behind higher levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia.2

And for health care workers on the front lines, the mental health toll could lead to stress, burnout, and worse.

Clinicians are also dealing with shortages of PPE and medical equipment, worrying about their safety and that of their families, while trying to save lives amid great uncertainty about SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Most recently an emergency department physician in New York who was recovering from COVID-19 herself reportedly recently ended her own life, according to her father, who is a physician.

As Dr. Sarah Candler said in a previous twitter chat with MDedge Internal Medicine, “Good doctors take care of themselves, too.” Be kind to yourself during this global crisis.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is always available at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Resources

- Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic

- Brief examines the COVID-19 crisis’ implications for Americans’ mental health

- COVID-19: Helping health care workers on the front lines

- Overcoming COVID-related stress

- Confessions of an outpatient psychiatrist during the pandemic

- Psychiatric patients may be among the hardest hit

- Experts hasten to head off mental health crisis

- Podcast: Physician Suicide

1Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20):30171-1.

2Brain, Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 27. doi: 10.10116/j.bbi.2020.04.069).

December 2017: Click for Credit

Here are 5 articles in the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. When Is It Really Recurrent Strep Throat?

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lHFh8i

Expires September 21, 2018

2. Revised Bethesda System Resets Thyroid Malignancy Risks

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2iSLOvM

Expires August 10, 2018

3. Tips for Avoiding Potentially Dangerous Patients

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lH1Fi7

Expires August 10, 2018

4. Study Findings Support Uncapping MELD Score

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2xOA7sI

Expires September 12, 2018

5. 'Motivational Pharmacotherapy' Engages Latino Patients With Depression

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2zs2ly4

Expires August 14, 2018

Here are 5 articles in the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. When Is It Really Recurrent Strep Throat?

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lHFh8i

Expires September 21, 2018

2. Revised Bethesda System Resets Thyroid Malignancy Risks

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2iSLOvM

Expires August 10, 2018

3. Tips for Avoiding Potentially Dangerous Patients

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lH1Fi7

Expires August 10, 2018

4. Study Findings Support Uncapping MELD Score

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2xOA7sI

Expires September 12, 2018

5. 'Motivational Pharmacotherapy' Engages Latino Patients With Depression

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2zs2ly4

Expires August 14, 2018

Here are 5 articles in the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. When Is It Really Recurrent Strep Throat?

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lHFh8i

Expires September 21, 2018

2. Revised Bethesda System Resets Thyroid Malignancy Risks

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2iSLOvM

Expires August 10, 2018

3. Tips for Avoiding Potentially Dangerous Patients

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2lH1Fi7

Expires August 10, 2018

4. Study Findings Support Uncapping MELD Score

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2xOA7sI

Expires September 12, 2018

5. 'Motivational Pharmacotherapy' Engages Latino Patients With Depression

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2zs2ly4

Expires August 14, 2018

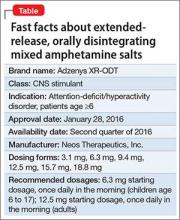

Extended-release, orally disintegrating mixed amphetamine salts for ADHD: New formulation

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

APA-IPS: Disaster psychiatry – Nepal, Ebola, and beyond

NEW YORK – After the earthquake in Nepal earlier this year, Disaster Psychiatry Outreach sent in volunteers who found preexisting issues that made their mental health response challenging at best, Dr. Ram Suresh Mahato reported at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Nepal was recovering from armed conflict that lasted from 1996 to 2006 and resulted in what some have called a “postconflict identity crisis” (Int J Educ Dev. 2014;34:42-50). The caste system in the country was abolished in 1963, but social inequality continued to persist. In addition, more than 60 languages are spoken in Nepal, and at least 25% of the population lives below the poverty line, said Dr. Mahato, a Disaster Psychiatry Outreach (DPO) volunteer who was part of the needs-assessment team dispatched to the country in May.

Other complicating factors included high rates of domestic violence. Nepali women are at greater risk of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress than are males (Lancet. 2008 May;371[9625]:1664) and (J Affect Disord. 2007 Sep;102[1-3]:219-25), and a culture of silence prevails, Dr. Mahato said. The literature describes informal social networks in Nepal in which community members share their distress and symptoms, “as well as traditional (shamanistic) healing practices for those suffering mental health complaints in relation to political violence” (Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jan;70[1]:35-44).

Dr. Mahato spoke at a workshop, sponsored by DPO, aimed at urging psychiatrists to be prepared in providing mental health services to disaster survivors across the globe and here at home. “The room was full last year,” said Dr. Sander Koyfman, DPO’s president, referring to the intense interest in Ebola at the height of the outbreak in 2014. “This year, it’s more of a challenge, as interest wanes from disaster to disaster,” but their organization would like to “sustain the desire in mental health providers and disaster responders to learn how to help most effectively,” Dr. Koyfman said in an interview.

The presentation focused on the mental health aspects of the Ebola response and the more recent DPO work following the earthquake in Nepal that killed 10,000 people. In a striking similarity, about 10,900 people died in the wake of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and its rolling impact across many regions. (In May, the World Health Organization declared Liberia free of Ebola but said on Oct. 14 that a preliminary study published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that the virus can persist in the semen of some survivors for at least 9 months.)

Vulnerable suffer most

Over the last 10 years, more than 1.4 million people have been injured and about 23 million have been left homeless across the globe because of man-made and natural disasters, according to a 2015 United Nations report. “Overall, more than 1.5 billion people have been affected by disasters in various ways, with women, children, and people in vulnerable situations disproportionately affected,” the report says.

DPO, a New York–based nonprofit, launched in 1998, has sent volunteers to an average of one disaster per year, said Dr. Koyfman, also medical director for EmblemHealth Insurance, New York.

“We at DPO learn to caution folks and say, ‘Look, it’s important and it’s critical to do everything you can, but do appreciate one thing: The key is what happens 3 to 6 months from today,’ ” he said. “The mental health component will happen then. This is very different from a typical disaster mentality.”

Before the earthquake in Nepal, manpower and resources were limited: The country has about 80 psychiatrists, or about 1 for every million people, said Dr. Mahato, chief psychiatry resident, PGY-4, at Mount Sinai/Elmhurst Hospital Center, New York. After the earthquake and more than 300 aftershocks, about 2.8 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. The DPO team partnered with the Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal by visiting affected districts and participating in health camps. “The challenges we saw involved developing communication and training materials in a culturally appropriate framework,” Dr. Mahato said.

Portable intervention used

One intervention used by DPO teams in Nepal was Psychological First Aid (PFA), Dr. Javier Garcia said.

PFA has grown in popularity and acceptance, especially when it became increasingly clear after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, that psychological debriefing was not as universally useful or safe modality as it was once thought to be, said Dr. Garcia of Richmond University Medical Center, New York.

In contrast, PFA is an intervention based on principles of resilience that focuses on safety, calming, connectedness, self-community, efficacy, and hope. “PFA assumes that people can have maladaptive reactions,” Dr. Garcia said. “ But is designed to reduce the initial distress and foster short- and long-term adaptive functioning.” He said all first responders, including fire, police and crisis response teams, health care professionals, and paraprofessionals can be trained to use PFA. In fact, another model of PFA was created for school staff in the 1990s in response to school shootings.

The first goal after a disaster is to ensure physical safety. After that, teams try to protect those traumatized from additional trauma. Emotionally overwhelmed and disoriented survivors must be stabilized, and medications generally are not recommended during this part of the process. Medications might be helpful in cases involving addiction or sleep, but such cases are exceptions, Dr. Garcia said. In general, the same strict clinical criteria for use of psychiatric medications are applicable in postdisaster environments and are specific to the episode and the individual. PFA attempts to be culturally informed and delivered in a flexible manner, Dr. Garcia said. “It’s evidence informed but not evidence based. So, we need more research.”

PFA, along with effective risk communications, frequently are the mainstay of an effective mental health response. Where PFA informs the “what” of the mental health conversation, risk communications, as Dr. Grant H. Brenner pointed out at the meeting, is the key “how” of getting the right message out the right way. Dr. Brenner, DPO board member, is a faculty member of Mount Sinai Hospital, director of the William Alanson White Institute Trauma Service, and an editor of Creating Spiritual and Psychological Resilience: Integrating Care in Disaster Relief Work (New York: Routledge, 2009).

After the Ebola work on the ground, volunteers often found complicated terrain in the United States. As the example of the single New York City Ebola patient showed, medical and psychological preparedness and the ability of the authorities to effectively communicate safety information to the public were tested. DPO worked with a nonprofit group called More Than Me to offer mental health support services to returning volunteers and to the few people who were under quarantine orders in New York.

Each disaster is different, but a few common themes are apparent. “There’s huge value in presence and human touch,” Dr. Koyfman said.

DPO offers training sessions for new volunteers. Psychiatrists interested in volunteering can send a message to [email protected] or call 646-867-3514. For more on risk communication, check out the information on emergency preparedness and response provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other useful resources are the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster and Resiliency in the Face of Disaster and Terrorism: 10 Things to Do to Survive (Personhood Press, 2005).

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

NEW YORK – After the earthquake in Nepal earlier this year, Disaster Psychiatry Outreach sent in volunteers who found preexisting issues that made their mental health response challenging at best, Dr. Ram Suresh Mahato reported at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Nepal was recovering from armed conflict that lasted from 1996 to 2006 and resulted in what some have called a “postconflict identity crisis” (Int J Educ Dev. 2014;34:42-50). The caste system in the country was abolished in 1963, but social inequality continued to persist. In addition, more than 60 languages are spoken in Nepal, and at least 25% of the population lives below the poverty line, said Dr. Mahato, a Disaster Psychiatry Outreach (DPO) volunteer who was part of the needs-assessment team dispatched to the country in May.

Other complicating factors included high rates of domestic violence. Nepali women are at greater risk of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress than are males (Lancet. 2008 May;371[9625]:1664) and (J Affect Disord. 2007 Sep;102[1-3]:219-25), and a culture of silence prevails, Dr. Mahato said. The literature describes informal social networks in Nepal in which community members share their distress and symptoms, “as well as traditional (shamanistic) healing practices for those suffering mental health complaints in relation to political violence” (Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jan;70[1]:35-44).

Dr. Mahato spoke at a workshop, sponsored by DPO, aimed at urging psychiatrists to be prepared in providing mental health services to disaster survivors across the globe and here at home. “The room was full last year,” said Dr. Sander Koyfman, DPO’s president, referring to the intense interest in Ebola at the height of the outbreak in 2014. “This year, it’s more of a challenge, as interest wanes from disaster to disaster,” but their organization would like to “sustain the desire in mental health providers and disaster responders to learn how to help most effectively,” Dr. Koyfman said in an interview.

The presentation focused on the mental health aspects of the Ebola response and the more recent DPO work following the earthquake in Nepal that killed 10,000 people. In a striking similarity, about 10,900 people died in the wake of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and its rolling impact across many regions. (In May, the World Health Organization declared Liberia free of Ebola but said on Oct. 14 that a preliminary study published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that the virus can persist in the semen of some survivors for at least 9 months.)

Vulnerable suffer most

Over the last 10 years, more than 1.4 million people have been injured and about 23 million have been left homeless across the globe because of man-made and natural disasters, according to a 2015 United Nations report. “Overall, more than 1.5 billion people have been affected by disasters in various ways, with women, children, and people in vulnerable situations disproportionately affected,” the report says.

DPO, a New York–based nonprofit, launched in 1998, has sent volunteers to an average of one disaster per year, said Dr. Koyfman, also medical director for EmblemHealth Insurance, New York.

“We at DPO learn to caution folks and say, ‘Look, it’s important and it’s critical to do everything you can, but do appreciate one thing: The key is what happens 3 to 6 months from today,’ ” he said. “The mental health component will happen then. This is very different from a typical disaster mentality.”

Before the earthquake in Nepal, manpower and resources were limited: The country has about 80 psychiatrists, or about 1 for every million people, said Dr. Mahato, chief psychiatry resident, PGY-4, at Mount Sinai/Elmhurst Hospital Center, New York. After the earthquake and more than 300 aftershocks, about 2.8 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. The DPO team partnered with the Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal by visiting affected districts and participating in health camps. “The challenges we saw involved developing communication and training materials in a culturally appropriate framework,” Dr. Mahato said.

Portable intervention used

One intervention used by DPO teams in Nepal was Psychological First Aid (PFA), Dr. Javier Garcia said.

PFA has grown in popularity and acceptance, especially when it became increasingly clear after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, that psychological debriefing was not as universally useful or safe modality as it was once thought to be, said Dr. Garcia of Richmond University Medical Center, New York.

In contrast, PFA is an intervention based on principles of resilience that focuses on safety, calming, connectedness, self-community, efficacy, and hope. “PFA assumes that people can have maladaptive reactions,” Dr. Garcia said. “ But is designed to reduce the initial distress and foster short- and long-term adaptive functioning.” He said all first responders, including fire, police and crisis response teams, health care professionals, and paraprofessionals can be trained to use PFA. In fact, another model of PFA was created for school staff in the 1990s in response to school shootings.

The first goal after a disaster is to ensure physical safety. After that, teams try to protect those traumatized from additional trauma. Emotionally overwhelmed and disoriented survivors must be stabilized, and medications generally are not recommended during this part of the process. Medications might be helpful in cases involving addiction or sleep, but such cases are exceptions, Dr. Garcia said. In general, the same strict clinical criteria for use of psychiatric medications are applicable in postdisaster environments and are specific to the episode and the individual. PFA attempts to be culturally informed and delivered in a flexible manner, Dr. Garcia said. “It’s evidence informed but not evidence based. So, we need more research.”

PFA, along with effective risk communications, frequently are the mainstay of an effective mental health response. Where PFA informs the “what” of the mental health conversation, risk communications, as Dr. Grant H. Brenner pointed out at the meeting, is the key “how” of getting the right message out the right way. Dr. Brenner, DPO board member, is a faculty member of Mount Sinai Hospital, director of the William Alanson White Institute Trauma Service, and an editor of Creating Spiritual and Psychological Resilience: Integrating Care in Disaster Relief Work (New York: Routledge, 2009).

After the Ebola work on the ground, volunteers often found complicated terrain in the United States. As the example of the single New York City Ebola patient showed, medical and psychological preparedness and the ability of the authorities to effectively communicate safety information to the public were tested. DPO worked with a nonprofit group called More Than Me to offer mental health support services to returning volunteers and to the few people who were under quarantine orders in New York.

Each disaster is different, but a few common themes are apparent. “There’s huge value in presence and human touch,” Dr. Koyfman said.

DPO offers training sessions for new volunteers. Psychiatrists interested in volunteering can send a message to [email protected] or call 646-867-3514. For more on risk communication, check out the information on emergency preparedness and response provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other useful resources are the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster and Resiliency in the Face of Disaster and Terrorism: 10 Things to Do to Survive (Personhood Press, 2005).

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

NEW YORK – After the earthquake in Nepal earlier this year, Disaster Psychiatry Outreach sent in volunteers who found preexisting issues that made their mental health response challenging at best, Dr. Ram Suresh Mahato reported at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Nepal was recovering from armed conflict that lasted from 1996 to 2006 and resulted in what some have called a “postconflict identity crisis” (Int J Educ Dev. 2014;34:42-50). The caste system in the country was abolished in 1963, but social inequality continued to persist. In addition, more than 60 languages are spoken in Nepal, and at least 25% of the population lives below the poverty line, said Dr. Mahato, a Disaster Psychiatry Outreach (DPO) volunteer who was part of the needs-assessment team dispatched to the country in May.

Other complicating factors included high rates of domestic violence. Nepali women are at greater risk of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress than are males (Lancet. 2008 May;371[9625]:1664) and (J Affect Disord. 2007 Sep;102[1-3]:219-25), and a culture of silence prevails, Dr. Mahato said. The literature describes informal social networks in Nepal in which community members share their distress and symptoms, “as well as traditional (shamanistic) healing practices for those suffering mental health complaints in relation to political violence” (Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jan;70[1]:35-44).

Dr. Mahato spoke at a workshop, sponsored by DPO, aimed at urging psychiatrists to be prepared in providing mental health services to disaster survivors across the globe and here at home. “The room was full last year,” said Dr. Sander Koyfman, DPO’s president, referring to the intense interest in Ebola at the height of the outbreak in 2014. “This year, it’s more of a challenge, as interest wanes from disaster to disaster,” but their organization would like to “sustain the desire in mental health providers and disaster responders to learn how to help most effectively,” Dr. Koyfman said in an interview.

The presentation focused on the mental health aspects of the Ebola response and the more recent DPO work following the earthquake in Nepal that killed 10,000 people. In a striking similarity, about 10,900 people died in the wake of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and its rolling impact across many regions. (In May, the World Health Organization declared Liberia free of Ebola but said on Oct. 14 that a preliminary study published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that the virus can persist in the semen of some survivors for at least 9 months.)

Vulnerable suffer most

Over the last 10 years, more than 1.4 million people have been injured and about 23 million have been left homeless across the globe because of man-made and natural disasters, according to a 2015 United Nations report. “Overall, more than 1.5 billion people have been affected by disasters in various ways, with women, children, and people in vulnerable situations disproportionately affected,” the report says.

DPO, a New York–based nonprofit, launched in 1998, has sent volunteers to an average of one disaster per year, said Dr. Koyfman, also medical director for EmblemHealth Insurance, New York.

“We at DPO learn to caution folks and say, ‘Look, it’s important and it’s critical to do everything you can, but do appreciate one thing: The key is what happens 3 to 6 months from today,’ ” he said. “The mental health component will happen then. This is very different from a typical disaster mentality.”

Before the earthquake in Nepal, manpower and resources were limited: The country has about 80 psychiatrists, or about 1 for every million people, said Dr. Mahato, chief psychiatry resident, PGY-4, at Mount Sinai/Elmhurst Hospital Center, New York. After the earthquake and more than 300 aftershocks, about 2.8 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. The DPO team partnered with the Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal by visiting affected districts and participating in health camps. “The challenges we saw involved developing communication and training materials in a culturally appropriate framework,” Dr. Mahato said.

Portable intervention used

One intervention used by DPO teams in Nepal was Psychological First Aid (PFA), Dr. Javier Garcia said.

PFA has grown in popularity and acceptance, especially when it became increasingly clear after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, that psychological debriefing was not as universally useful or safe modality as it was once thought to be, said Dr. Garcia of Richmond University Medical Center, New York.

In contrast, PFA is an intervention based on principles of resilience that focuses on safety, calming, connectedness, self-community, efficacy, and hope. “PFA assumes that people can have maladaptive reactions,” Dr. Garcia said. “ But is designed to reduce the initial distress and foster short- and long-term adaptive functioning.” He said all first responders, including fire, police and crisis response teams, health care professionals, and paraprofessionals can be trained to use PFA. In fact, another model of PFA was created for school staff in the 1990s in response to school shootings.

The first goal after a disaster is to ensure physical safety. After that, teams try to protect those traumatized from additional trauma. Emotionally overwhelmed and disoriented survivors must be stabilized, and medications generally are not recommended during this part of the process. Medications might be helpful in cases involving addiction or sleep, but such cases are exceptions, Dr. Garcia said. In general, the same strict clinical criteria for use of psychiatric medications are applicable in postdisaster environments and are specific to the episode and the individual. PFA attempts to be culturally informed and delivered in a flexible manner, Dr. Garcia said. “It’s evidence informed but not evidence based. So, we need more research.”

PFA, along with effective risk communications, frequently are the mainstay of an effective mental health response. Where PFA informs the “what” of the mental health conversation, risk communications, as Dr. Grant H. Brenner pointed out at the meeting, is the key “how” of getting the right message out the right way. Dr. Brenner, DPO board member, is a faculty member of Mount Sinai Hospital, director of the William Alanson White Institute Trauma Service, and an editor of Creating Spiritual and Psychological Resilience: Integrating Care in Disaster Relief Work (New York: Routledge, 2009).

After the Ebola work on the ground, volunteers often found complicated terrain in the United States. As the example of the single New York City Ebola patient showed, medical and psychological preparedness and the ability of the authorities to effectively communicate safety information to the public were tested. DPO worked with a nonprofit group called More Than Me to offer mental health support services to returning volunteers and to the few people who were under quarantine orders in New York.

Each disaster is different, but a few common themes are apparent. “There’s huge value in presence and human touch,” Dr. Koyfman said.

DPO offers training sessions for new volunteers. Psychiatrists interested in volunteering can send a message to [email protected] or call 646-867-3514. For more on risk communication, check out the information on emergency preparedness and response provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other useful resources are the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster and Resiliency in the Face of Disaster and Terrorism: 10 Things to Do to Survive (Personhood Press, 2005).

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE INSTITUTE ON PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

APA-IPS: Gun ownership is a public health issue

NEW YORK – The prevalence of guns in the United States is a public health issue that must be addressed head-on by clinicians – including psychiatrists, experts said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Part of the challenge is bridging the cultural disconnect between some psychiatrists and patients. About 10% of psychiatrists own guns, but the ownership rate among U.S. households ranges from 40%-50%, said Dr. John Rozel, a psychiatrist affiliated with the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh. “Most of us psychiatrists might not intrinsically get it.”

Facing the ubiquity of guns in American life might be a good place to start. The United States has more than 270,000,000 civilian-owned firearms, which is more than the next 18 countries combined, Dr. Rozel said, quoting 2007 data from the global Small Arms Survey. “Wouldn’t it be great if you could get your hands on access to mental health care” as fast as you can get your hands on a gun?

The secure place of guns within American life requires “radical acceptance” on the part of psychiatrists, Dr. Abhishek Jain said at the session.

“The Second Amendment is not going anywhere,” said Dr. Jain, also a psychiatrist with the clinic. “Keep in mind how much buying [of guns] there is in your jurisdiction. Pay attention to your own state laws. Variability is considerable.”

An understanding of these laws needs to occur while recognizing that the public is largely misinformed about the tendency of people with mental illness to turn to violence. “Little population-level evidence supports the notion that individuals diagnosed with mental illness are more likely than anyone else to commit gun crimes,” Dr. Jonathan M. Metzl and Kenneth T. MacLeish, Ph.D., wrote in a recent review (Am J Public Health. 2015 Feb;105[2]:240-9). “Databases that track gun homicides, such as the National Center for Health Statistics, similarly show that fewer than 5% of the 120,000 gun-related killings in the United States between 2001 and 2010 were perpetrated by people diagnosed with mental illness,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People with mental illness are more likely to hurt themselves than others. Furthermore, tighter gun laws are associated with lower rates of suicide. A recent study found a connection between more stringent laws involving waiting periods, universal background checks, gun locks, and open carrying regulations in four states and a drop in suicide rates (Am J Public Health. 2015;105[10]:2049-58). “We should talk about individual safety,” Dr. Jain said.

Talking with your patients about guns

Dr. Layla Soliman encouraged developing a working knowledge about some of the fine points of guns, such as how they work. “After every tragedy, we see [in the comments section of online articles] ‘why can’t psychiatrists stop these people?’ We’re part of the discussion, whether we want to be or not,” said Dr. Soliman, a psychiatric attending on the inpatient unit at the hospital.

Asking all patients about the role of guns in their lives should be routine, she said. “We are trained to do this [as part of] a checklist. We have to ask in the same way we ask about past violence [and] substance use.” Document these conversations with patients defensively, Dr. Soliman said. “I would suggest an integrated risk assessment in your documentation.”

Dr. Rozel agreed. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons from our colleagues in pediatrics [and] how they talk with patients about vaccinations,” he said. Dr. Rozel is trained as a child psychiatrist and holds a master of studies in law degree.

Using motivational interviewing is a good way to get patients to open up about their access to guns and how they view them. “It’s about collaboration, not confrontation,” Dr. Rozel said. “It’s about accepting their reality [and] not imposing our will on them. They may not want to have this conversation. Express empathy [by saying]: ‘I don’t want to take any unnecessary chances with your life.’ ”

Dr. Rozel, Dr. Jain, and Dr. Soliman are also assistant professors of psychiatry at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. They said they had no disclosures.

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

NEW YORK – The prevalence of guns in the United States is a public health issue that must be addressed head-on by clinicians – including psychiatrists, experts said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Part of the challenge is bridging the cultural disconnect between some psychiatrists and patients. About 10% of psychiatrists own guns, but the ownership rate among U.S. households ranges from 40%-50%, said Dr. John Rozel, a psychiatrist affiliated with the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh. “Most of us psychiatrists might not intrinsically get it.”

Facing the ubiquity of guns in American life might be a good place to start. The United States has more than 270,000,000 civilian-owned firearms, which is more than the next 18 countries combined, Dr. Rozel said, quoting 2007 data from the global Small Arms Survey. “Wouldn’t it be great if you could get your hands on access to mental health care” as fast as you can get your hands on a gun?

The secure place of guns within American life requires “radical acceptance” on the part of psychiatrists, Dr. Abhishek Jain said at the session.

“The Second Amendment is not going anywhere,” said Dr. Jain, also a psychiatrist with the clinic. “Keep in mind how much buying [of guns] there is in your jurisdiction. Pay attention to your own state laws. Variability is considerable.”

An understanding of these laws needs to occur while recognizing that the public is largely misinformed about the tendency of people with mental illness to turn to violence. “Little population-level evidence supports the notion that individuals diagnosed with mental illness are more likely than anyone else to commit gun crimes,” Dr. Jonathan M. Metzl and Kenneth T. MacLeish, Ph.D., wrote in a recent review (Am J Public Health. 2015 Feb;105[2]:240-9). “Databases that track gun homicides, such as the National Center for Health Statistics, similarly show that fewer than 5% of the 120,000 gun-related killings in the United States between 2001 and 2010 were perpetrated by people diagnosed with mental illness,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People with mental illness are more likely to hurt themselves than others. Furthermore, tighter gun laws are associated with lower rates of suicide. A recent study found a connection between more stringent laws involving waiting periods, universal background checks, gun locks, and open carrying regulations in four states and a drop in suicide rates (Am J Public Health. 2015;105[10]:2049-58). “We should talk about individual safety,” Dr. Jain said.

Talking with your patients about guns

Dr. Layla Soliman encouraged developing a working knowledge about some of the fine points of guns, such as how they work. “After every tragedy, we see [in the comments section of online articles] ‘why can’t psychiatrists stop these people?’ We’re part of the discussion, whether we want to be or not,” said Dr. Soliman, a psychiatric attending on the inpatient unit at the hospital.

Asking all patients about the role of guns in their lives should be routine, she said. “We are trained to do this [as part of] a checklist. We have to ask in the same way we ask about past violence [and] substance use.” Document these conversations with patients defensively, Dr. Soliman said. “I would suggest an integrated risk assessment in your documentation.”

Dr. Rozel agreed. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons from our colleagues in pediatrics [and] how they talk with patients about vaccinations,” he said. Dr. Rozel is trained as a child psychiatrist and holds a master of studies in law degree.

Using motivational interviewing is a good way to get patients to open up about their access to guns and how they view them. “It’s about collaboration, not confrontation,” Dr. Rozel said. “It’s about accepting their reality [and] not imposing our will on them. They may not want to have this conversation. Express empathy [by saying]: ‘I don’t want to take any unnecessary chances with your life.’ ”

Dr. Rozel, Dr. Jain, and Dr. Soliman are also assistant professors of psychiatry at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. They said they had no disclosures.

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

NEW YORK – The prevalence of guns in the United States is a public health issue that must be addressed head-on by clinicians – including psychiatrists, experts said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

Part of the challenge is bridging the cultural disconnect between some psychiatrists and patients. About 10% of psychiatrists own guns, but the ownership rate among U.S. households ranges from 40%-50%, said Dr. John Rozel, a psychiatrist affiliated with the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh. “Most of us psychiatrists might not intrinsically get it.”

Facing the ubiquity of guns in American life might be a good place to start. The United States has more than 270,000,000 civilian-owned firearms, which is more than the next 18 countries combined, Dr. Rozel said, quoting 2007 data from the global Small Arms Survey. “Wouldn’t it be great if you could get your hands on access to mental health care” as fast as you can get your hands on a gun?

The secure place of guns within American life requires “radical acceptance” on the part of psychiatrists, Dr. Abhishek Jain said at the session.

“The Second Amendment is not going anywhere,” said Dr. Jain, also a psychiatrist with the clinic. “Keep in mind how much buying [of guns] there is in your jurisdiction. Pay attention to your own state laws. Variability is considerable.”

An understanding of these laws needs to occur while recognizing that the public is largely misinformed about the tendency of people with mental illness to turn to violence. “Little population-level evidence supports the notion that individuals diagnosed with mental illness are more likely than anyone else to commit gun crimes,” Dr. Jonathan M. Metzl and Kenneth T. MacLeish, Ph.D., wrote in a recent review (Am J Public Health. 2015 Feb;105[2]:240-9). “Databases that track gun homicides, such as the National Center for Health Statistics, similarly show that fewer than 5% of the 120,000 gun-related killings in the United States between 2001 and 2010 were perpetrated by people diagnosed with mental illness,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People with mental illness are more likely to hurt themselves than others. Furthermore, tighter gun laws are associated with lower rates of suicide. A recent study found a connection between more stringent laws involving waiting periods, universal background checks, gun locks, and open carrying regulations in four states and a drop in suicide rates (Am J Public Health. 2015;105[10]:2049-58). “We should talk about individual safety,” Dr. Jain said.

Talking with your patients about guns

Dr. Layla Soliman encouraged developing a working knowledge about some of the fine points of guns, such as how they work. “After every tragedy, we see [in the comments section of online articles] ‘why can’t psychiatrists stop these people?’ We’re part of the discussion, whether we want to be or not,” said Dr. Soliman, a psychiatric attending on the inpatient unit at the hospital.

Asking all patients about the role of guns in their lives should be routine, she said. “We are trained to do this [as part of] a checklist. We have to ask in the same way we ask about past violence [and] substance use.” Document these conversations with patients defensively, Dr. Soliman said. “I would suggest an integrated risk assessment in your documentation.”

Dr. Rozel agreed. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons from our colleagues in pediatrics [and] how they talk with patients about vaccinations,” he said. Dr. Rozel is trained as a child psychiatrist and holds a master of studies in law degree.

Using motivational interviewing is a good way to get patients to open up about their access to guns and how they view them. “It’s about collaboration, not confrontation,” Dr. Rozel said. “It’s about accepting their reality [and] not imposing our will on them. They may not want to have this conversation. Express empathy [by saying]: ‘I don’t want to take any unnecessary chances with your life.’ ”

Dr. Rozel, Dr. Jain, and Dr. Soliman are also assistant professors of psychiatry at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. They said they had no disclosures.

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE INSTITUTE ON PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

FDA approves Aristada for acute exacerbation of schizophrenia

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aripiprazole lauroxil, a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic, for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the drug, which came Oct. 5, was based on results of a 12-week multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 622 patients aged 18-70 years, with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia who had been stabilized with oral aripiprazole (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76[8]:1085-90).

Patients who received 441-mg or 882-mg injections of aripiprazole lauroxil every 4 weeks experienced significant reductions in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores from baseline to day 85, compared with those on placebo. The secondary efficacy outcome was improvement in the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvementscore at day 85. Insomnia, akathisia, headache, and anxiety were the most common adverse side effects.

Aripiprazole lauroxil, which will be marketed as Aristada, should be administered every 4-6 weeks. The drug joins two other long-acting injectables for treating schizophrenia – olanzapine (Zyprexa Relprevv) and aripiprazole (Abilify Maintena).

“Having a variety of treatment options and dosage forms available for patients with mental illness is important so that a treatment plan can be tailored to meet the patient’s needs,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Like other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada will have a boxed warning about the increased risk of death associated with the off-label use of these drugs for treating older patients with psychosis tied to dementia. Aristada is manufactured by Alkermes.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aripiprazole lauroxil, a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic, for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the drug, which came Oct. 5, was based on results of a 12-week multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 622 patients aged 18-70 years, with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia who had been stabilized with oral aripiprazole (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76[8]:1085-90).

Patients who received 441-mg or 882-mg injections of aripiprazole lauroxil every 4 weeks experienced significant reductions in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores from baseline to day 85, compared with those on placebo. The secondary efficacy outcome was improvement in the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvementscore at day 85. Insomnia, akathisia, headache, and anxiety were the most common adverse side effects.

Aripiprazole lauroxil, which will be marketed as Aristada, should be administered every 4-6 weeks. The drug joins two other long-acting injectables for treating schizophrenia – olanzapine (Zyprexa Relprevv) and aripiprazole (Abilify Maintena).

“Having a variety of treatment options and dosage forms available for patients with mental illness is important so that a treatment plan can be tailored to meet the patient’s needs,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Like other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada will have a boxed warning about the increased risk of death associated with the off-label use of these drugs for treating older patients with psychosis tied to dementia. Aristada is manufactured by Alkermes.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aripiprazole lauroxil, a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic, for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the drug, which came Oct. 5, was based on results of a 12-week multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 622 patients aged 18-70 years, with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia who had been stabilized with oral aripiprazole (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76[8]:1085-90).

Patients who received 441-mg or 882-mg injections of aripiprazole lauroxil every 4 weeks experienced significant reductions in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores from baseline to day 85, compared with those on placebo. The secondary efficacy outcome was improvement in the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvementscore at day 85. Insomnia, akathisia, headache, and anxiety were the most common adverse side effects.

Aripiprazole lauroxil, which will be marketed as Aristada, should be administered every 4-6 weeks. The drug joins two other long-acting injectables for treating schizophrenia – olanzapine (Zyprexa Relprevv) and aripiprazole (Abilify Maintena).

“Having a variety of treatment options and dosage forms available for patients with mental illness is important so that a treatment plan can be tailored to meet the patient’s needs,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, director of the division of psychiatry products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Like other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada will have a boxed warning about the increased risk of death associated with the off-label use of these drugs for treating older patients with psychosis tied to dementia. Aristada is manufactured by Alkermes.

VIDEO: Three veterans describe impact of mindfulness therapy

Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy teaches patients to be in the present moment in nonjudgmental, accepting ways. Researchers at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center decided to compare a mindfulness intervention with present-centered group therapy of 116 veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Those in the mindfulness group had eight weekly 2.5-hour sessions and one day-long retreat. Veterans in the present-centered group attended nine weekly 1.5-hour group sessions focusing on current problems. The results found that the veterans who used the mindfulness techniques experienced a greater decrease in the severity of their PTSD symptoms than did those in the other group.

In this video, Melissa A. Polusny, Ph.D., and Dr. Kelvin O. Lim, both of the medical center, talk with three veterans with PTSD about how mindfulness changed their quality of life and helped them find peace of mind.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy teaches patients to be in the present moment in nonjudgmental, accepting ways. Researchers at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center decided to compare a mindfulness intervention with present-centered group therapy of 116 veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Those in the mindfulness group had eight weekly 2.5-hour sessions and one day-long retreat. Veterans in the present-centered group attended nine weekly 1.5-hour group sessions focusing on current problems. The results found that the veterans who used the mindfulness techniques experienced a greater decrease in the severity of their PTSD symptoms than did those in the other group.

In this video, Melissa A. Polusny, Ph.D., and Dr. Kelvin O. Lim, both of the medical center, talk with three veterans with PTSD about how mindfulness changed their quality of life and helped them find peace of mind.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy teaches patients to be in the present moment in nonjudgmental, accepting ways. Researchers at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center decided to compare a mindfulness intervention with present-centered group therapy of 116 veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Those in the mindfulness group had eight weekly 2.5-hour sessions and one day-long retreat. Veterans in the present-centered group attended nine weekly 1.5-hour group sessions focusing on current problems. The results found that the veterans who used the mindfulness techniques experienced a greater decrease in the severity of their PTSD symptoms than did those in the other group.

In this video, Melissa A. Polusny, Ph.D., and Dr. Kelvin O. Lim, both of the medical center, talk with three veterans with PTSD about how mindfulness changed their quality of life and helped them find peace of mind.