User login

Antipsychotic Use Spikes in Medicaid-Enrolled Children

Antipsychotic use in children aged 3-18 years increased by 62% between 2002 and 2007, according to Medicaid data from about 15 million children in the United States.

Although the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in children has grown in recent decades, evidence supporting their effectiveness for many conditions is limited, said Meredith Matone of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and her colleagues, including Dr. David M. Rubin, codirector of policy lab at the hospital and an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

"In light of recent research indicating rising use of antipsychotics in children coupled with concurrent research demonstrating significant side effects of these medications, it felt like a critical next step to understand who the populations of users were and how this population may have changed over the course of the last decade," she said in an interview. The findings were published online (Health Services Research Sept. 5 [doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01461.x]).

To examine the relationship between diagnosis and prescription of SGAs, the researchers reviewed Medicaid data from children in 50 states and the District of Columbia between 2002 and 2007.

Overall, 354,000 children were using SGAs in 2007. Of these, 39% were diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 11% with bipolar disorder, 12% with ADHD and bipolar, and 38% with other conditions.

In 2007, 50% of children taking antipsychotics had a diagnosis of ADHD, and in 14%, ADHD was their only mental health diagnosis. Approximately two-thirds (65%) of the antipsychotic prescriptions for children were for off-label use of the drugs. "The lack of safety and efficacy data is especially significant given a growing body of research indicating serious adverse side effects of antipsychotics in children," the researchers noted.

The study points out that neither the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry nor the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends second-generation antipsychotics for ADHD management.

Ms. Matone and her colleagues said they had expected to see use of the medications for diagnoses associated with diagnoses such as ADHD and conduct disorder – despite the lack of Food and Drug Administration approval of the drugs for those indications. "However, the size of this population of off-label users and its growth over time was surprising," Ms. Matone said.

"For clinicians, these findings reinforce the importance of both understanding safety concerns associated with pediatric antipsychotic use and being informed about the efficacy and availability of alternative non-pharmacologic treatment therapies.

"There is also a need for information sharing with parents about treatment decisions involving off-label medication use, safety concerns, and alternative treatment approaches," she said.

In addition, further research is needed to explore the indication for antipsychotic use in patients with behavioral problems such as ADHD, the researchers noted.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by a fellowship from the Stoneleigh Foundation to Dr. Rubin.

Antipsychotic use in children aged 3-18 years increased by 62% between 2002 and 2007, according to Medicaid data from about 15 million children in the United States.

Although the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in children has grown in recent decades, evidence supporting their effectiveness for many conditions is limited, said Meredith Matone of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and her colleagues, including Dr. David M. Rubin, codirector of policy lab at the hospital and an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

"In light of recent research indicating rising use of antipsychotics in children coupled with concurrent research demonstrating significant side effects of these medications, it felt like a critical next step to understand who the populations of users were and how this population may have changed over the course of the last decade," she said in an interview. The findings were published online (Health Services Research Sept. 5 [doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01461.x]).

To examine the relationship between diagnosis and prescription of SGAs, the researchers reviewed Medicaid data from children in 50 states and the District of Columbia between 2002 and 2007.

Overall, 354,000 children were using SGAs in 2007. Of these, 39% were diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 11% with bipolar disorder, 12% with ADHD and bipolar, and 38% with other conditions.

In 2007, 50% of children taking antipsychotics had a diagnosis of ADHD, and in 14%, ADHD was their only mental health diagnosis. Approximately two-thirds (65%) of the antipsychotic prescriptions for children were for off-label use of the drugs. "The lack of safety and efficacy data is especially significant given a growing body of research indicating serious adverse side effects of antipsychotics in children," the researchers noted.

The study points out that neither the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry nor the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends second-generation antipsychotics for ADHD management.

Ms. Matone and her colleagues said they had expected to see use of the medications for diagnoses associated with diagnoses such as ADHD and conduct disorder – despite the lack of Food and Drug Administration approval of the drugs for those indications. "However, the size of this population of off-label users and its growth over time was surprising," Ms. Matone said.

"For clinicians, these findings reinforce the importance of both understanding safety concerns associated with pediatric antipsychotic use and being informed about the efficacy and availability of alternative non-pharmacologic treatment therapies.

"There is also a need for information sharing with parents about treatment decisions involving off-label medication use, safety concerns, and alternative treatment approaches," she said.

In addition, further research is needed to explore the indication for antipsychotic use in patients with behavioral problems such as ADHD, the researchers noted.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by a fellowship from the Stoneleigh Foundation to Dr. Rubin.

Antipsychotic use in children aged 3-18 years increased by 62% between 2002 and 2007, according to Medicaid data from about 15 million children in the United States.

Although the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in children has grown in recent decades, evidence supporting their effectiveness for many conditions is limited, said Meredith Matone of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and her colleagues, including Dr. David M. Rubin, codirector of policy lab at the hospital and an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

"In light of recent research indicating rising use of antipsychotics in children coupled with concurrent research demonstrating significant side effects of these medications, it felt like a critical next step to understand who the populations of users were and how this population may have changed over the course of the last decade," she said in an interview. The findings were published online (Health Services Research Sept. 5 [doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01461.x]).

To examine the relationship between diagnosis and prescription of SGAs, the researchers reviewed Medicaid data from children in 50 states and the District of Columbia between 2002 and 2007.

Overall, 354,000 children were using SGAs in 2007. Of these, 39% were diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 11% with bipolar disorder, 12% with ADHD and bipolar, and 38% with other conditions.

In 2007, 50% of children taking antipsychotics had a diagnosis of ADHD, and in 14%, ADHD was their only mental health diagnosis. Approximately two-thirds (65%) of the antipsychotic prescriptions for children were for off-label use of the drugs. "The lack of safety and efficacy data is especially significant given a growing body of research indicating serious adverse side effects of antipsychotics in children," the researchers noted.

The study points out that neither the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry nor the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends second-generation antipsychotics for ADHD management.

Ms. Matone and her colleagues said they had expected to see use of the medications for diagnoses associated with diagnoses such as ADHD and conduct disorder – despite the lack of Food and Drug Administration approval of the drugs for those indications. "However, the size of this population of off-label users and its growth over time was surprising," Ms. Matone said.

"For clinicians, these findings reinforce the importance of both understanding safety concerns associated with pediatric antipsychotic use and being informed about the efficacy and availability of alternative non-pharmacologic treatment therapies.

"There is also a need for information sharing with parents about treatment decisions involving off-label medication use, safety concerns, and alternative treatment approaches," she said.

In addition, further research is needed to explore the indication for antipsychotic use in patients with behavioral problems such as ADHD, the researchers noted.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by a fellowship from the Stoneleigh Foundation to Dr. Rubin.

FROM HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH

Major Finding: In 2007, 50% of children taking antipsychotics had a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Data Source: The findings are based on Medicaid data from about 15 million children in 50 states and the District of Columbia between 2002 and 2007.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by a fellowship from the Stoneleigh Foundation to coauthor Dr. Rubin.

Flu Vaccination Called an 'Ethical and Professional Responsibility'

WASHINGTON – Approximately 42% of the U.S. population and 67% of health care workers received influenza vaccinations last year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the CDC’s 2010 recommendation for universal flu vaccination for everyone aged 6 months and older, "we seem to be on track in protecting the nation against influenza," Dr. William Schaffner, past president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, said at a press conference.

But there is room for improvement, and clinicians play a key role, said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a professor and chair of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

"I believe that the immunization of the health care provider community is both an ethical and professional responsibility," he said. "It is for two reasons: The first and most important is a patient safety issue, so we do not transmit our influenza infection to our patients."

"The other reason is, when influenza strikes, we need to be vertical, not horizontal," he continued. "We need to be ready to provide health care during that period of great community stress."

"There are many factors that make it easier than ever for everyone to receive flu vaccination," including a plentiful vaccine supply and a variety of venues, including workplaces, where individuals can be vaccinated, said Dr. Schaffner. Proper handwashing, cough and sneeze etiquette, and the prompt use of antivirals also are important to prevent and limit the spread of the flu.

"A physician’s recommendation can be the deciding factor for patients who are sitting on the fence" about getting a flu vaccination, said Litjen Tan, Ph.D., director of medicine and public health for the American Medical Association.

Recent CDC data indicate that pregnant women whose doctors recommended flu vaccination were five times as likely to get a vaccination, and 44% of adults above age 65 who didn’t intend to get vaccinated did so when a doctor recommended it, Dr. Tan said.

"Every physician has an opportunity this flu season to remind their patients to get vaccinated," he said. "Physicians such as cardiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, pulmonologists, and endocrinologists, who all have high-risk patients, should encourage their patients to seek influenza vaccinations as soon as they are available."

Approximately 85 million doses of flu vaccine have been distributed so far this season, with more on the way, for a total of about 135 million doses, said Dr. Daniel Jernigan, deputy director of the influenza division in the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

"The best time to get vaccinated is before the flu season starts," he said. "It is hard to know when the flu will start and where it will start," but vaccination is still recommended throughout the flu season.

This year's vaccine contains a new A virus and a new B virus.

"The few strains we have seen so far match what’s in the vaccine," Dr. Jernigan said.

Although last year’s flu season was the mildest since 1982, clinicians should not be complacent about vaccination for themselves and their patients, said Dr. Howard Koh, assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

"The last few years have demonstrated that the flu is predictably unpredictable," Dr. Koh said. The flu pandemic of 2009-2010 was followed by an unusually mild flu season in 2011-2012, but flu-related hospitalizations and deaths occur every year.

"We can’t look to the past to predict the future," he emphasized.

Dr. Koh highlighted data on the recent progress in vaccination coverage, which appeared in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report online Sept. 27 (2012;61:753-63).

Overall, 52% of children aged 6 months to 17 years were vaccinated during the 2011-2012 season, approximately the same rate as the previous year, with a rate of 75% among children aged 6 months to 23 months.

However, vaccination of adolescents remains a challenge; 34% of children aged 13-17 years were vaccinated, said Dr. Koh. Adults aged 65 years and older had a 65% vaccination rate last year, but this was a drop from 74% in 2008-2009.

Vaccination coverage among pregnant women was consistent with the previous year, at 47%, remaining significantly higher than the 30% rate before the 2008-2009 flu season.

For the second year in a row, no racial or ethnic disparities were seen in vaccination rates for children, although these disparities persist among adults, Dr. Koh said.

The press conference was sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. For the complete report on flu vaccination in health care personnel and in pregnant women, visit the MMWR website here.

WASHINGTON – Approximately 42% of the U.S. population and 67% of health care workers received influenza vaccinations last year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the CDC’s 2010 recommendation for universal flu vaccination for everyone aged 6 months and older, "we seem to be on track in protecting the nation against influenza," Dr. William Schaffner, past president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, said at a press conference.

But there is room for improvement, and clinicians play a key role, said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a professor and chair of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

"I believe that the immunization of the health care provider community is both an ethical and professional responsibility," he said. "It is for two reasons: The first and most important is a patient safety issue, so we do not transmit our influenza infection to our patients."

"The other reason is, when influenza strikes, we need to be vertical, not horizontal," he continued. "We need to be ready to provide health care during that period of great community stress."

"There are many factors that make it easier than ever for everyone to receive flu vaccination," including a plentiful vaccine supply and a variety of venues, including workplaces, where individuals can be vaccinated, said Dr. Schaffner. Proper handwashing, cough and sneeze etiquette, and the prompt use of antivirals also are important to prevent and limit the spread of the flu.

"A physician’s recommendation can be the deciding factor for patients who are sitting on the fence" about getting a flu vaccination, said Litjen Tan, Ph.D., director of medicine and public health for the American Medical Association.

Recent CDC data indicate that pregnant women whose doctors recommended flu vaccination were five times as likely to get a vaccination, and 44% of adults above age 65 who didn’t intend to get vaccinated did so when a doctor recommended it, Dr. Tan said.

"Every physician has an opportunity this flu season to remind their patients to get vaccinated," he said. "Physicians such as cardiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, pulmonologists, and endocrinologists, who all have high-risk patients, should encourage their patients to seek influenza vaccinations as soon as they are available."

Approximately 85 million doses of flu vaccine have been distributed so far this season, with more on the way, for a total of about 135 million doses, said Dr. Daniel Jernigan, deputy director of the influenza division in the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

"The best time to get vaccinated is before the flu season starts," he said. "It is hard to know when the flu will start and where it will start," but vaccination is still recommended throughout the flu season.

This year's vaccine contains a new A virus and a new B virus.

"The few strains we have seen so far match what’s in the vaccine," Dr. Jernigan said.

Although last year’s flu season was the mildest since 1982, clinicians should not be complacent about vaccination for themselves and their patients, said Dr. Howard Koh, assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

"The last few years have demonstrated that the flu is predictably unpredictable," Dr. Koh said. The flu pandemic of 2009-2010 was followed by an unusually mild flu season in 2011-2012, but flu-related hospitalizations and deaths occur every year.

"We can’t look to the past to predict the future," he emphasized.

Dr. Koh highlighted data on the recent progress in vaccination coverage, which appeared in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report online Sept. 27 (2012;61:753-63).

Overall, 52% of children aged 6 months to 17 years were vaccinated during the 2011-2012 season, approximately the same rate as the previous year, with a rate of 75% among children aged 6 months to 23 months.

However, vaccination of adolescents remains a challenge; 34% of children aged 13-17 years were vaccinated, said Dr. Koh. Adults aged 65 years and older had a 65% vaccination rate last year, but this was a drop from 74% in 2008-2009.

Vaccination coverage among pregnant women was consistent with the previous year, at 47%, remaining significantly higher than the 30% rate before the 2008-2009 flu season.

For the second year in a row, no racial or ethnic disparities were seen in vaccination rates for children, although these disparities persist among adults, Dr. Koh said.

The press conference was sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. For the complete report on flu vaccination in health care personnel and in pregnant women, visit the MMWR website here.

WASHINGTON – Approximately 42% of the U.S. population and 67% of health care workers received influenza vaccinations last year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the CDC’s 2010 recommendation for universal flu vaccination for everyone aged 6 months and older, "we seem to be on track in protecting the nation against influenza," Dr. William Schaffner, past president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, said at a press conference.

But there is room for improvement, and clinicians play a key role, said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a professor and chair of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

"I believe that the immunization of the health care provider community is both an ethical and professional responsibility," he said. "It is for two reasons: The first and most important is a patient safety issue, so we do not transmit our influenza infection to our patients."

"The other reason is, when influenza strikes, we need to be vertical, not horizontal," he continued. "We need to be ready to provide health care during that period of great community stress."

"There are many factors that make it easier than ever for everyone to receive flu vaccination," including a plentiful vaccine supply and a variety of venues, including workplaces, where individuals can be vaccinated, said Dr. Schaffner. Proper handwashing, cough and sneeze etiquette, and the prompt use of antivirals also are important to prevent and limit the spread of the flu.

"A physician’s recommendation can be the deciding factor for patients who are sitting on the fence" about getting a flu vaccination, said Litjen Tan, Ph.D., director of medicine and public health for the American Medical Association.

Recent CDC data indicate that pregnant women whose doctors recommended flu vaccination were five times as likely to get a vaccination, and 44% of adults above age 65 who didn’t intend to get vaccinated did so when a doctor recommended it, Dr. Tan said.

"Every physician has an opportunity this flu season to remind their patients to get vaccinated," he said. "Physicians such as cardiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, pulmonologists, and endocrinologists, who all have high-risk patients, should encourage their patients to seek influenza vaccinations as soon as they are available."

Approximately 85 million doses of flu vaccine have been distributed so far this season, with more on the way, for a total of about 135 million doses, said Dr. Daniel Jernigan, deputy director of the influenza division in the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

"The best time to get vaccinated is before the flu season starts," he said. "It is hard to know when the flu will start and where it will start," but vaccination is still recommended throughout the flu season.

This year's vaccine contains a new A virus and a new B virus.

"The few strains we have seen so far match what’s in the vaccine," Dr. Jernigan said.

Although last year’s flu season was the mildest since 1982, clinicians should not be complacent about vaccination for themselves and their patients, said Dr. Howard Koh, assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

"The last few years have demonstrated that the flu is predictably unpredictable," Dr. Koh said. The flu pandemic of 2009-2010 was followed by an unusually mild flu season in 2011-2012, but flu-related hospitalizations and deaths occur every year.

"We can’t look to the past to predict the future," he emphasized.

Dr. Koh highlighted data on the recent progress in vaccination coverage, which appeared in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report online Sept. 27 (2012;61:753-63).

Overall, 52% of children aged 6 months to 17 years were vaccinated during the 2011-2012 season, approximately the same rate as the previous year, with a rate of 75% among children aged 6 months to 23 months.

However, vaccination of adolescents remains a challenge; 34% of children aged 13-17 years were vaccinated, said Dr. Koh. Adults aged 65 years and older had a 65% vaccination rate last year, but this was a drop from 74% in 2008-2009.

Vaccination coverage among pregnant women was consistent with the previous year, at 47%, remaining significantly higher than the 30% rate before the 2008-2009 flu season.

For the second year in a row, no racial or ethnic disparities were seen in vaccination rates for children, although these disparities persist among adults, Dr. Koh said.

The press conference was sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. For the complete report on flu vaccination in health care personnel and in pregnant women, visit the MMWR website here.

FROM A NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES INFLUENZA PRESS CONFERENCE

Don't Rush to Intervene in Pediatric Epiglottitis

WASHINGTON – Managing pediatric epiglottitis without intervention resulted in significantly shortened hospital stays and lower costs, based on data from 820 children.

"Due to the increasing rarity of this disease, suspicion for the diagnosis must remain high for prompt recognition and treatment," said Dr. Marci J. Neidich of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The use of intubation and tracheotomy to treat epiglottitis in children continues to decline, with a trend toward conservative management, she noted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

To assess the predictive factors for intervention, Dr. Neidich and her colleagues reviewed data from 820 patients in the Kids’ Inpatient Databases for 2006 and 2009 who were treated for acute epiglottitis with and without obstruction.

Overall, 705 children (86%) were managed conservatively and 115 (14%) required intervention (defined as either a tracheotomy or intubation).

Conservative management of epiglottitis in children resulted in a significantly shorter length of hospital stay compared with intervention (an average of 4 days vs. 11 days). The average cost was significantly lower as well ($18,487 vs. $83,037).

Patients were significantly more likely to be managed conservatively in urgent admission compared with emergent cases, and in urban nonteaching hospitals compared with urban teaching hospitals.

Other significant predictors of conservative management included being in a hospital not primarily for children versus a children’s unit or children’s hospital, and being in a small or medium-sized hospital compared with a large hospital.

There were no significant differences in age, race, or sex between the nonintervention and intervention groups. Approximately one-third were female, and approximately 42% were white. The average age was 6 years in the intervention group and 8 years in the nonintervention group. Mortality was less than 10 patients.

The results suggest that most children with epiglottitis can be managed conservatively for a lower cost and with shorter hospital stays and lower mortality rates, said Dr. Neidich. However, additional studies are needed to investigate which patients would be appropriate for intervention versus conservative management, she said.

Dr. Neidich reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Managing pediatric epiglottitis without intervention resulted in significantly shortened hospital stays and lower costs, based on data from 820 children.

"Due to the increasing rarity of this disease, suspicion for the diagnosis must remain high for prompt recognition and treatment," said Dr. Marci J. Neidich of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The use of intubation and tracheotomy to treat epiglottitis in children continues to decline, with a trend toward conservative management, she noted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

To assess the predictive factors for intervention, Dr. Neidich and her colleagues reviewed data from 820 patients in the Kids’ Inpatient Databases for 2006 and 2009 who were treated for acute epiglottitis with and without obstruction.

Overall, 705 children (86%) were managed conservatively and 115 (14%) required intervention (defined as either a tracheotomy or intubation).

Conservative management of epiglottitis in children resulted in a significantly shorter length of hospital stay compared with intervention (an average of 4 days vs. 11 days). The average cost was significantly lower as well ($18,487 vs. $83,037).

Patients were significantly more likely to be managed conservatively in urgent admission compared with emergent cases, and in urban nonteaching hospitals compared with urban teaching hospitals.

Other significant predictors of conservative management included being in a hospital not primarily for children versus a children’s unit or children’s hospital, and being in a small or medium-sized hospital compared with a large hospital.

There were no significant differences in age, race, or sex between the nonintervention and intervention groups. Approximately one-third were female, and approximately 42% were white. The average age was 6 years in the intervention group and 8 years in the nonintervention group. Mortality was less than 10 patients.

The results suggest that most children with epiglottitis can be managed conservatively for a lower cost and with shorter hospital stays and lower mortality rates, said Dr. Neidich. However, additional studies are needed to investigate which patients would be appropriate for intervention versus conservative management, she said.

Dr. Neidich reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

WASHINGTON – Managing pediatric epiglottitis without intervention resulted in significantly shortened hospital stays and lower costs, based on data from 820 children.

"Due to the increasing rarity of this disease, suspicion for the diagnosis must remain high for prompt recognition and treatment," said Dr. Marci J. Neidich of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The use of intubation and tracheotomy to treat epiglottitis in children continues to decline, with a trend toward conservative management, she noted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

To assess the predictive factors for intervention, Dr. Neidich and her colleagues reviewed data from 820 patients in the Kids’ Inpatient Databases for 2006 and 2009 who were treated for acute epiglottitis with and without obstruction.

Overall, 705 children (86%) were managed conservatively and 115 (14%) required intervention (defined as either a tracheotomy or intubation).

Conservative management of epiglottitis in children resulted in a significantly shorter length of hospital stay compared with intervention (an average of 4 days vs. 11 days). The average cost was significantly lower as well ($18,487 vs. $83,037).

Patients were significantly more likely to be managed conservatively in urgent admission compared with emergent cases, and in urban nonteaching hospitals compared with urban teaching hospitals.

Other significant predictors of conservative management included being in a hospital not primarily for children versus a children’s unit or children’s hospital, and being in a small or medium-sized hospital compared with a large hospital.

There were no significant differences in age, race, or sex between the nonintervention and intervention groups. Approximately one-third were female, and approximately 42% were white. The average age was 6 years in the intervention group and 8 years in the nonintervention group. Mortality was less than 10 patients.

The results suggest that most children with epiglottitis can be managed conservatively for a lower cost and with shorter hospital stays and lower mortality rates, said Dr. Neidich. However, additional studies are needed to investigate which patients would be appropriate for intervention versus conservative management, she said.

Dr. Neidich reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY - HEAD AND NECK SURGERY FOUNDATION

Major Finding: Managing pediatric epiglottitis without intervention significantly shortened hospital stays (4 days vs. 11 days) and cut costs ($18,487 vs. $83,037) compared with intervention.

Data Source: The data come from a review of 820 patients in the Kids’ Inpatient Databases for 2006 and 2009 who were treated for acute epiglottitis with and without obstruction.

Disclosures: Dr. Neidich said she had no relevant financial conflicts.

CCR7 Predicts Cervical Metastasis in Oral Cancer

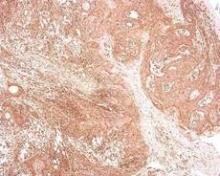

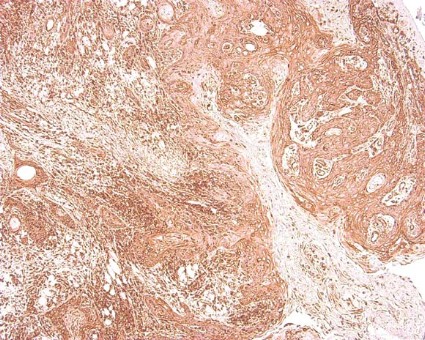

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY-HEAD AND NECK SURGERY FOUNDATION

Don't Screen Healthy Women for Ovarian Cancer

Clinicians need not screen women for ovarian cancer if they are otherwise healthy and have no known genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 that could increase their ovarian cancer risk, according to a recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine and on the USPSTF website on Sept. 11.

After reviewing data from randomized, controlled trials between 2008 and 2011, a USPSTF Task Force determined that the number of deaths from ovarian cancer in U.S. women was not significantly reduced by annual screening with transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 testing.

In addition, the data revealed a high rate of false-positive results in asymptomatic women, who then may undergo unnecessary surgery and other harm, the USPSTF said in its statement.

In the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, a randomized, controlled trial of 78,216 women in the United States, there was no significant difference in the number of ovarian cancer cases diagnosed in women randomized to annual screening vs. usual care (212 vs. 176) over 13 years. No significant differences were seen in the number of cancer deaths between the two groups. One-third of the women with false-positive results underwent oophorectomies, with nearly 21 major complications per 100 surgeries performed on the basis of false-positive results.

Data from another recent trial, the Shizuoka Cohort Study of Ovarian Cancer Screening, suggested that approximately 33 surgeries would be needed to diagnose 1 case of ovarian cancer detected by routine screening. More data are pending from an ongoing trial, the U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS).

Based on the available data, "There is adequate evidence that there is no mortality benefit to routine screening for ovarian cancer with transvaginal ultrasonography or single-threshold serum CA-125 testing, and that the harms of such screening are at least moderate," according to the USPSTF.

"Final results from UKCTOCS should provide more information about the relative benefits and harms of an algorithm-based approach to screening for ovarian cancer," the Task Force stated.

Neither the American Cancer Society nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend screening asymptomatic, average-risk women for ovarian cancer, according to a USPSTF press release about the new recommendation.

The recommendation is a grade D, which the USPSTF defines as "moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits," and providers therefore are discouraged from using the service.

This recommendation does not apply to women who are considered at high risk for ovarian cancer. Populations at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer include women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations, Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer), or a family history of ovarian cancer. A family history "generally means having two or more first- or second-degree relatives with a history of ovarian cancer or a combination of breast and ovarian cancer; for women of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, it means having a first-degree relative (or two second-degree relatives on the same side of the family) with breast or ovarian cancer," according to the USPSTF statement.

As one of the top five leading causes of cancer death among women, it is important that methods of screening and early detection of ovarian cancer be continually evaluated. Because of the lack of symptoms until metastatic disease is present, the majority of women are diagnosed with advanced-stage (stage IIIC) disease. For this reason, it is important that screening focus on asymptomatic women in an attempt to diagnose at an earlier stage and thus provide an opportunity for improved survival, according to Dr. Georgia A. McCann and Dr. Ritu Salani.

Based on the evidence reviewed, the USPSTF recommendation against screening asymptomatic women with CA-125 and pelvic ultrasound is valid and should be considered definitive. Furthermore, these recommendations reiterate the results of previous studies and, once again, report that screening does not provide an improvement in the detection of early-stage disease or translate to a survival advantage. Thus, screening asymptomatic women with current technologies does little more than provide false reassurance for women with normal findings and result in potentially unnecessary surgery (with a high complication rate) in women with abnormal findings.

However, the lack of screening tests amplifies the importance of asking patients about possible genetic predisposition by obtaining a thorough family history, as well as reviewing ovarian cancer symptoms such as abdominal bloating, abdominal/pelvic pain, early satiety, and changes in bowel/bladder function. If patients are found to be high risk or symptomatic, it is imperative that we, as health care providers, engage in the appropriate evaluation and management.

Given the morbidity and mortality of this disease, it is vital that research continues on the early detection of ovarian cancer. New biomarkers, improvements in imaging, and an enhanced understanding of genetics may allow for better screening methods to be evaluated soon. In the interim, providers should be aware of the pitfalls of ovarian cancer screening and continue to educate patients on the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Dr McCann and Dr. Salani of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, commented on the USPSTF findings. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

As one of the top five leading causes of cancer death among women, it is important that methods of screening and early detection of ovarian cancer be continually evaluated. Because of the lack of symptoms until metastatic disease is present, the majority of women are diagnosed with advanced-stage (stage IIIC) disease. For this reason, it is important that screening focus on asymptomatic women in an attempt to diagnose at an earlier stage and thus provide an opportunity for improved survival, according to Dr. Georgia A. McCann and Dr. Ritu Salani.

Based on the evidence reviewed, the USPSTF recommendation against screening asymptomatic women with CA-125 and pelvic ultrasound is valid and should be considered definitive. Furthermore, these recommendations reiterate the results of previous studies and, once again, report that screening does not provide an improvement in the detection of early-stage disease or translate to a survival advantage. Thus, screening asymptomatic women with current technologies does little more than provide false reassurance for women with normal findings and result in potentially unnecessary surgery (with a high complication rate) in women with abnormal findings.

However, the lack of screening tests amplifies the importance of asking patients about possible genetic predisposition by obtaining a thorough family history, as well as reviewing ovarian cancer symptoms such as abdominal bloating, abdominal/pelvic pain, early satiety, and changes in bowel/bladder function. If patients are found to be high risk or symptomatic, it is imperative that we, as health care providers, engage in the appropriate evaluation and management.

Given the morbidity and mortality of this disease, it is vital that research continues on the early detection of ovarian cancer. New biomarkers, improvements in imaging, and an enhanced understanding of genetics may allow for better screening methods to be evaluated soon. In the interim, providers should be aware of the pitfalls of ovarian cancer screening and continue to educate patients on the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Dr McCann and Dr. Salani of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, commented on the USPSTF findings. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

As one of the top five leading causes of cancer death among women, it is important that methods of screening and early detection of ovarian cancer be continually evaluated. Because of the lack of symptoms until metastatic disease is present, the majority of women are diagnosed with advanced-stage (stage IIIC) disease. For this reason, it is important that screening focus on asymptomatic women in an attempt to diagnose at an earlier stage and thus provide an opportunity for improved survival, according to Dr. Georgia A. McCann and Dr. Ritu Salani.

Based on the evidence reviewed, the USPSTF recommendation against screening asymptomatic women with CA-125 and pelvic ultrasound is valid and should be considered definitive. Furthermore, these recommendations reiterate the results of previous studies and, once again, report that screening does not provide an improvement in the detection of early-stage disease or translate to a survival advantage. Thus, screening asymptomatic women with current technologies does little more than provide false reassurance for women with normal findings and result in potentially unnecessary surgery (with a high complication rate) in women with abnormal findings.

However, the lack of screening tests amplifies the importance of asking patients about possible genetic predisposition by obtaining a thorough family history, as well as reviewing ovarian cancer symptoms such as abdominal bloating, abdominal/pelvic pain, early satiety, and changes in bowel/bladder function. If patients are found to be high risk or symptomatic, it is imperative that we, as health care providers, engage in the appropriate evaluation and management.

Given the morbidity and mortality of this disease, it is vital that research continues on the early detection of ovarian cancer. New biomarkers, improvements in imaging, and an enhanced understanding of genetics may allow for better screening methods to be evaluated soon. In the interim, providers should be aware of the pitfalls of ovarian cancer screening and continue to educate patients on the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Dr McCann and Dr. Salani of the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, commented on the USPSTF findings. They said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Clinicians need not screen women for ovarian cancer if they are otherwise healthy and have no known genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 that could increase their ovarian cancer risk, according to a recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine and on the USPSTF website on Sept. 11.

After reviewing data from randomized, controlled trials between 2008 and 2011, a USPSTF Task Force determined that the number of deaths from ovarian cancer in U.S. women was not significantly reduced by annual screening with transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 testing.

In addition, the data revealed a high rate of false-positive results in asymptomatic women, who then may undergo unnecessary surgery and other harm, the USPSTF said in its statement.

In the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, a randomized, controlled trial of 78,216 women in the United States, there was no significant difference in the number of ovarian cancer cases diagnosed in women randomized to annual screening vs. usual care (212 vs. 176) over 13 years. No significant differences were seen in the number of cancer deaths between the two groups. One-third of the women with false-positive results underwent oophorectomies, with nearly 21 major complications per 100 surgeries performed on the basis of false-positive results.

Data from another recent trial, the Shizuoka Cohort Study of Ovarian Cancer Screening, suggested that approximately 33 surgeries would be needed to diagnose 1 case of ovarian cancer detected by routine screening. More data are pending from an ongoing trial, the U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS).

Based on the available data, "There is adequate evidence that there is no mortality benefit to routine screening for ovarian cancer with transvaginal ultrasonography or single-threshold serum CA-125 testing, and that the harms of such screening are at least moderate," according to the USPSTF.

"Final results from UKCTOCS should provide more information about the relative benefits and harms of an algorithm-based approach to screening for ovarian cancer," the Task Force stated.

Neither the American Cancer Society nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend screening asymptomatic, average-risk women for ovarian cancer, according to a USPSTF press release about the new recommendation.

The recommendation is a grade D, which the USPSTF defines as "moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits," and providers therefore are discouraged from using the service.

This recommendation does not apply to women who are considered at high risk for ovarian cancer. Populations at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer include women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations, Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer), or a family history of ovarian cancer. A family history "generally means having two or more first- or second-degree relatives with a history of ovarian cancer or a combination of breast and ovarian cancer; for women of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, it means having a first-degree relative (or two second-degree relatives on the same side of the family) with breast or ovarian cancer," according to the USPSTF statement.

Clinicians need not screen women for ovarian cancer if they are otherwise healthy and have no known genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 that could increase their ovarian cancer risk, according to a recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine and on the USPSTF website on Sept. 11.

After reviewing data from randomized, controlled trials between 2008 and 2011, a USPSTF Task Force determined that the number of deaths from ovarian cancer in U.S. women was not significantly reduced by annual screening with transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 testing.

In addition, the data revealed a high rate of false-positive results in asymptomatic women, who then may undergo unnecessary surgery and other harm, the USPSTF said in its statement.

In the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, a randomized, controlled trial of 78,216 women in the United States, there was no significant difference in the number of ovarian cancer cases diagnosed in women randomized to annual screening vs. usual care (212 vs. 176) over 13 years. No significant differences were seen in the number of cancer deaths between the two groups. One-third of the women with false-positive results underwent oophorectomies, with nearly 21 major complications per 100 surgeries performed on the basis of false-positive results.

Data from another recent trial, the Shizuoka Cohort Study of Ovarian Cancer Screening, suggested that approximately 33 surgeries would be needed to diagnose 1 case of ovarian cancer detected by routine screening. More data are pending from an ongoing trial, the U.K. Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS).

Based on the available data, "There is adequate evidence that there is no mortality benefit to routine screening for ovarian cancer with transvaginal ultrasonography or single-threshold serum CA-125 testing, and that the harms of such screening are at least moderate," according to the USPSTF.

"Final results from UKCTOCS should provide more information about the relative benefits and harms of an algorithm-based approach to screening for ovarian cancer," the Task Force stated.

Neither the American Cancer Society nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend screening asymptomatic, average-risk women for ovarian cancer, according to a USPSTF press release about the new recommendation.

The recommendation is a grade D, which the USPSTF defines as "moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits," and providers therefore are discouraged from using the service.

This recommendation does not apply to women who are considered at high risk for ovarian cancer. Populations at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer include women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations, Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer), or a family history of ovarian cancer. A family history "generally means having two or more first- or second-degree relatives with a history of ovarian cancer or a combination of breast and ovarian cancer; for women of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, it means having a first-degree relative (or two second-degree relatives on the same side of the family) with breast or ovarian cancer," according to the USPSTF statement.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

New Data Bolster Current Guidelines for Surveillance After Polypectomy (copy 1)

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.

The task force is composed of GI specialists representing the three major GI professional organizations: American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), American Gastroenterological Association Institute (AGAI), and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Overall, the recommendations have not changed, but the task force reviewed the most recent literature and found additional evidence to support several categories of surveillance and screening intervals for adults with average risk of CRC at the time of a baseline screening.

Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 10-year interval for individuals with no polyps, and a 5- to 10-year interval for those with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. New evidence also supports a 3-year interval for patients with 3-10 tubular adenomas of any size, and also 3 years for patients with one or more tubular adenomas 10 mm or larger. In addition, data reported since 2006 support a 3-year surveillance interval for patients with one or more villous adenomas.

Recommendations that remain unchanged without additional evidence are a 10-year surveillance interval for individuals with hyperplastic polyps in the rectum or sigmoid, an interval of less than 3 years for those with more than 10 adenomas, and an interval of 3 years in cases of an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, serrated lesions are now included as part of the surveillance schedule after a baseline colonoscopy. Individuals with one or more sessile serrated polyps less than 10 mm in size and no dysplasia should be rescreened after 5 years. Those with one or more sessile serrated polyps 10 mm or larger, or any sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, or a traditional serrated adenoma should be rescreened after 3 years.

Individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) should be rescreened after 1 year. Serrated polyposis syndrome is defined as meeting one of three criteria (in agreement with the World Health Organization definition): at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid, with at least two measuring 10 mm or larger; any serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid in patients with a family history of SPS; and more than 20 serrated polyps of any size throughout the colon.

The authors noted that the quality of the evidence supporting the current guidelines is low, and will require updates. "There are no longitudinal studies available on which to base surveillance intervals after resection," they said.

In addition, given new evidence about the increased risk of colonoscopy with advancing age, surveillance and screening should be discontinued when the risks outweigh the benefits, according to the guidelines. "The United States Preventive Services Task Forces determined that screening should not be continued after age 85 years because risk could exceed potential benefit," the task force noted. "It is the opinion of the MSTF that the decision to continue surveillance should be individualized, based on an assessment of benefit, risk, and co-morbidities."

However, "the guidelines are dynamic, and will be revised in the future, based on new evidence. This new evidence should include information about the quality of the baseline examinations," the authors said. "The task force recommends that all endoscopists monitor key quality indicators as part of a colonoscopy screening and surveillance program," they noted.

Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.

The task force is composed of GI specialists representing the three major GI professional organizations: American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), American Gastroenterological Association Institute (AGAI), and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Overall, the recommendations have not changed, but the task force reviewed the most recent literature and found additional evidence to support several categories of surveillance and screening intervals for adults with average risk of CRC at the time of a baseline screening.

Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 10-year interval for individuals with no polyps, and a 5- to 10-year interval for those with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. New evidence also supports a 3-year interval for patients with 3-10 tubular adenomas of any size, and also 3 years for patients with one or more tubular adenomas 10 mm or larger. In addition, data reported since 2006 support a 3-year surveillance interval for patients with one or more villous adenomas.

Recommendations that remain unchanged without additional evidence are a 10-year surveillance interval for individuals with hyperplastic polyps in the rectum or sigmoid, an interval of less than 3 years for those with more than 10 adenomas, and an interval of 3 years in cases of an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, serrated lesions are now included as part of the surveillance schedule after a baseline colonoscopy. Individuals with one or more sessile serrated polyps less than 10 mm in size and no dysplasia should be rescreened after 5 years. Those with one or more sessile serrated polyps 10 mm or larger, or any sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, or a traditional serrated adenoma should be rescreened after 3 years.

Individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) should be rescreened after 1 year. Serrated polyposis syndrome is defined as meeting one of three criteria (in agreement with the World Health Organization definition): at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid, with at least two measuring 10 mm or larger; any serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid in patients with a family history of SPS; and more than 20 serrated polyps of any size throughout the colon.

The authors noted that the quality of the evidence supporting the current guidelines is low, and will require updates. "There are no longitudinal studies available on which to base surveillance intervals after resection," they said.

In addition, given new evidence about the increased risk of colonoscopy with advancing age, surveillance and screening should be discontinued when the risks outweigh the benefits, according to the guidelines. "The United States Preventive Services Task Forces determined that screening should not be continued after age 85 years because risk could exceed potential benefit," the task force noted. "It is the opinion of the MSTF that the decision to continue surveillance should be individualized, based on an assessment of benefit, risk, and co-morbidities."

However, "the guidelines are dynamic, and will be revised in the future, based on new evidence. This new evidence should include information about the quality of the baseline examinations," the authors said. "The task force recommends that all endoscopists monitor key quality indicators as part of a colonoscopy screening and surveillance program," they noted.

Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.

The task force is composed of GI specialists representing the three major GI professional organizations: American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), American Gastroenterological Association Institute (AGAI), and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Overall, the recommendations have not changed, but the task force reviewed the most recent literature and found additional evidence to support several categories of surveillance and screening intervals for adults with average risk of CRC at the time of a baseline screening.

Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 10-year interval for individuals with no polyps, and a 5- to 10-year interval for those with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. New evidence also supports a 3-year interval for patients with 3-10 tubular adenomas of any size, and also 3 years for patients with one or more tubular adenomas 10 mm or larger. In addition, data reported since 2006 support a 3-year surveillance interval for patients with one or more villous adenomas.

Recommendations that remain unchanged without additional evidence are a 10-year surveillance interval for individuals with hyperplastic polyps in the rectum or sigmoid, an interval of less than 3 years for those with more than 10 adenomas, and an interval of 3 years in cases of an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, serrated lesions are now included as part of the surveillance schedule after a baseline colonoscopy. Individuals with one or more sessile serrated polyps less than 10 mm in size and no dysplasia should be rescreened after 5 years. Those with one or more sessile serrated polyps 10 mm or larger, or any sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, or a traditional serrated adenoma should be rescreened after 3 years.

Individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) should be rescreened after 1 year. Serrated polyposis syndrome is defined as meeting one of three criteria (in agreement with the World Health Organization definition): at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid, with at least two measuring 10 mm or larger; any serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid in patients with a family history of SPS; and more than 20 serrated polyps of any size throughout the colon.

The authors noted that the quality of the evidence supporting the current guidelines is low, and will require updates. "There are no longitudinal studies available on which to base surveillance intervals after resection," they said.

In addition, given new evidence about the increased risk of colonoscopy with advancing age, surveillance and screening should be discontinued when the risks outweigh the benefits, according to the guidelines. "The United States Preventive Services Task Forces determined that screening should not be continued after age 85 years because risk could exceed potential benefit," the task force noted. "It is the opinion of the MSTF that the decision to continue surveillance should be individualized, based on an assessment of benefit, risk, and co-morbidities."

However, "the guidelines are dynamic, and will be revised in the future, based on new evidence. This new evidence should include information about the quality of the baseline examinations," the authors said. "The task force recommends that all endoscopists monitor key quality indicators as part of a colonoscopy screening and surveillance program," they noted.

Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Major Finding: Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 5- to 10-year interval for individuals with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size.

Data Source: The data come from a review of English-language articles published between 2005 and 2011.

Disclosures: Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

Post-Polypectomy Surveillance Guidelines Updated

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.

The task force is composed of GI specialists representing the three major GI professional organizations: the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Overall, the recommendations have not changed, but the task force reviewed the most recent literature and found additional evidence to support several categories of surveillance and screening intervals for adults with average risk of CRC at the time of a baseline screening.

Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 10-year interval for individuals with no polyps, and a 5- to 10-year interval for those with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. New evidence also supports a 3-year interval for patients with 3-10 tubular adenomas of any size, and also 3 years for patients with one or more tubular adenomas 10 mm or larger. In addition, data reported since 2006 support a 3-year surveillance interval for patients with one or more villous adenomas.

Recommendations that remain unchanged without additional evidence are a 10-year surveillance interval for individuals with hyperplastic polyps in the rectum or sigmoid, an interval of less than 3 years for those with more than 10 adenomas, and an interval of 3 years in cases of an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, serrated lesions are now included as part of the surveillance schedule after a baseline colonoscopy. Individuals with one or more sessile serrated polyps less than 10 mm in size and no dysplasia should be rescreened after 5 years. Those with one or more sessile serrated polyps 10 mm or larger, or any sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, or a traditional serrated adenoma should be rescreened after 3 years.

Individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) should be rescreened after 1 year. Serrated polyposis syndrome is defined as meeting one of three criteria (in agreement with the World Health Organization definition): at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid, with at least two measuring 10 mm or larger; any serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid in patients with a family history of SPS; and more than 20 serrated polyps of any size throughout the colon.

The authors noted that the quality of the evidence supporting the current guidelines is low, and will require updates. "There are no longitudinal studies available on which to base surveillance intervals after resection," they said.

In addition, given new evidence about the increased risk of colonoscopy with advancing age, surveillance and screening should be discontinued when the risks outweigh the benefits, according to the guidelines. "The United States Preventive Services Task Forces determined that screening should not be continued after age 85 years because risk could exceed potential benefit," the task force noted. "It is the opinion of the MSTF that the decision to continue surveillance should be individualized, based on an assessment of benefit, risk, and co-morbidities."

However, "the guidelines are dynamic, and will be revised in the future, based on new evidence. This new evidence should include information about the quality of the baseline examinations," the authors said. "The task force recommends that all endoscopists monitor key quality indicators as part of a colonoscopy screening and surveillance program," they noted.

Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.

The task force is composed of GI specialists representing the three major GI professional organizations: the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Overall, the recommendations have not changed, but the task force reviewed the most recent literature and found additional evidence to support several categories of surveillance and screening intervals for adults with average risk of CRC at the time of a baseline screening.

Recommendations supported by new evidence include a 10-year interval for individuals with no polyps, and a 5- to 10-year interval for those with one or two tubular adenomas less than 10 mm in size. New evidence also supports a 3-year interval for patients with 3-10 tubular adenomas of any size, and also 3 years for patients with one or more tubular adenomas 10 mm or larger. In addition, data reported since 2006 support a 3-year surveillance interval for patients with one or more villous adenomas.

Recommendations that remain unchanged without additional evidence are a 10-year surveillance interval for individuals with hyperplastic polyps in the rectum or sigmoid, an interval of less than 3 years for those with more than 10 adenomas, and an interval of 3 years in cases of an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, serrated lesions are now included as part of the surveillance schedule after a baseline colonoscopy. Individuals with one or more sessile serrated polyps less than 10 mm in size and no dysplasia should be rescreened after 5 years. Those with one or more sessile serrated polyps 10 mm or larger, or any sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, or a traditional serrated adenoma should be rescreened after 3 years.

Individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) should be rescreened after 1 year. Serrated polyposis syndrome is defined as meeting one of three criteria (in agreement with the World Health Organization definition): at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid, with at least two measuring 10 mm or larger; any serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid in patients with a family history of SPS; and more than 20 serrated polyps of any size throughout the colon.

The authors noted that the quality of the evidence supporting the current guidelines is low, and will require updates. "There are no longitudinal studies available on which to base surveillance intervals after resection," they said.

In addition, given new evidence about the increased risk of colonoscopy with advancing age, surveillance and screening should be discontinued when the risks outweigh the benefits, according to the guidelines. "The United States Preventive Services Task Forces determined that screening should not be continued after age 85 years because risk could exceed potential benefit," the task force noted. "It is the opinion of the MSTF that the decision to continue surveillance should be individualized, based on an assessment of benefit, risk, and co-morbidities."

However, "the guidelines are dynamic, and will be revised in the future, based on new evidence. This new evidence should include information about the quality of the baseline examinations," the authors said. "The task force recommends that all endoscopists monitor key quality indicators as part of a colonoscopy screening and surveillance program," they noted.

Lead author Dr. David Lieberman has served on the advisory boards of Given Imaging and Exact Sciences.

Adults with no polyps at baseline colonoscopy and average risk for colorectal cancer can still wait 10 years until their next colonoscopy, according to updated surveillance guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. The guidelines were published in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

New concerns, including the risk of interval colorectal cancer (CRC), the risk of proximal colorectal cancer, and the role of serrated polyps in carcinogenesis prompted an update to the guidelines, which were last revised in 2006, according to lead author Dr. David A. Lieberman of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and his colleagues.