User login

Top 10 tips community hospitalists need to know for implementing a QI project

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

Top 10 things physician advisors want hospitalists to know

The practice of hospital medicine is rapidly changing. Higher-acuity patients are being admitted to hospitals already struggling with capacity, and hospitalists are being instructed to pay attention to length of stay, improve their documentation and billing, and participate in initiatives to improve hospital throughput, all while delivering high-quality patient care.

As hospitalists and SHM members who are also physician advisors, we have a unique understanding of these pressures. In this article, we answer common questions we receive from hospitalists regarding utilization management, care coordination, clinical documentation, and CMS regulations.

Why do physician advisors exist, and what do they do?

A physician advisor is hired by the hospital to act as a liaison between the hospital administration, clinical staff, and support personnel in order to ensure regulatory compliance, advise physicians on medical necessity, and assist hospital leadership in meeting overall organizational goals related to the efficient utilization of health care services.1

Given their deep knowledge of hospital systems and processes, and ability to collaborate and teach, hospitalists are well-positioned to serve in this capacity. Our primary goal as physician advisors is to help physicians continue to focus on the parts of medicine they enjoy – clinical care, education, quality improvement, research etc. – by helping to demystify complex regulatory requirements and by creating streamlined processes to make following these requirements easier.

Why does this matter?

We understand that regulatory and hospital systems issues such as patient class determination, appropriate clinical documentation, and hospital throughput and capacity management can feel tedious, and sometimes overwhelming, to busy hospitalists. While it is easy to attribute these problems solely to hospitals’ desire for increased revenue, these issues directly impact the quality of care we provide to their patients.

In addition, our entire financial system is predicated on appropriate health care resource utilization, financial reimbursement, demonstration of medical acuity, and our impact on the care of a patient. Thus, our ability to advocate for our patients and for ourselves is directly connected with this endeavor. Developing a working knowledge of regulatory and systems issues allows hospitalists to be more engaged in leadership and negotiations and allows us to advocate for resources we deem most important.

Why are clinical documentation integrity teams so important?

Accurately and specifically describing how sick your patients are helps ensure that hospitals are reimbursed appropriately, coded data is accurate for research purposes, quality metrics are attributed correctly, and patients receive the correct diagnoses.

Clarification of documentation and/or addressing “clinical validity” of a given diagnosis (e.g., acute hypoxic respiratory failure requires both hypoxia and respiratory distress) may support an increase or result in a decrease in hospital reimbursement. For example, if the reason for a patient’s admission is renal failure, renal failure with true acute hypoxic respiratory failure will be reimbursed at a rate 40% higher than renal failure without the documentation of other conditions that reflect how ill the patient really is. The patient with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (or other major comorbid condition) is genuinely sicker, thus requiring more time (length of stay) and resources (deserved higher reimbursement).

What is the two-midnight rule, and why does it matter?

In October of 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initiated the two-midnight rule, which states a Medicare patient can be an “inpatient” class if the admitting provider determines that 1) the patient requires medically necessary care which cannot be provided outside the hospital and 2) the patient is expected to stay at least 2 midnights in the hospital.

If, at the time of admission, an admitting provider thinks it is likely that the patient may be discharged prior to 2 midnights, then outpatient care with “observation” designation is appropriate. Incorrect patient class assignment may result in significant adverse consequences for hospitals, including improper patient billing, decreased hospital reimbursement, substantial risk for external auditing, violation of Medicare conditions of participation, and even loss of accreditation.

Who can I talk to if I have a question about a patient’s class? What should I do if I disagree with the class assigned to my patient?

The Utilization Management team typically consists of nurses and physician advisors specifically trained in UM. This team functions as a liaison between providers and payers (particularly Medicare and Medicaid) regarding medical necessity, appropriateness of care received, and efficiency of health care services.

When it comes to discussions about patient class, start by learning more about why the determination was made. The most common reason for patient class disagreements is simply that the documentation does not reflect the severity of illness or accurately reflect the care the patient is receiving. Your documentation should communicate that your patient needs services that only the hospital can provide, and/or they need monitoring that must be done in the hospital to meet the medical necessity criteria that CMS requires for a patient to be “inpatient” class.

If you disagree with a determination provided by the UM nurse and/or physician advisor, then the case will be presented to the hospital UM committee for further review. Two physicians from the UM committee must review the case and provide their own determinations of patient status, and whichever admission determination has two votes is the one that is appropriate.

How do I talk to patients about class determinations?

As media coverage continues about the two-midnight rule and the impact this has on patients, providers should expect more questions about class determination from their patients.

An AARP Bulletin article from 2012 advised patients to “ask [their] own doctor whether observation status is justified … and if not ask him or her to call the hospital to explain the medical reasons why they should be admitted as inpatient.”2 Patients should be informed that providers understand the implications of patient class determinations and are making these decisions as outlined by CMS.

We recommend informing patients that the decision about whether a patient is “inpatient” or “outpatient with observation” class is complex and involves taking into consideration a patient’s medical history, the severity of their current medical condition, need for diagnostic testing, and degree of health resource utilization, as well as a provider’s medical opinion of the risk of an adverse event occurring.

Is it true that observation patients receive higher hospital bills?

It is a common misperception that a designation of “observation” class means that a patient’s medical bill will be higher than “inpatient” class. In 2016, CMS changed the way observation class patients are billed so that, in most scenarios, patients do not receive a higher hospital bill when placed in “observation” class.

How do I approach a denial from a payer?

Commercial payers review all hospitalizations for medical necessity and appropriateness of care received during a patient’s hospitalization. If you receive notice that all or part of your patient’s hospital stay was denied coverage, you have the option of discussing the case with the medical director of the insurance company – this is called a peer-to-peer discussion.

We recommend reviewing the patient’s case and your documentation of the care you provided prior to the peer to peer, especially since these denials may come weeks to months after you have cared for the patient. Begin your conversation by learning why the insurance company denied coverage of the stay and then provide an accurate portrayal of the acuity of illness of the patient, and the resources your hospital used in caring for them. Consider consulting with your hospital’s physician advisor for other high-yield tips.

How can care management help with ‘nonmedical’ hospitalizations?

Care managers are your allies for all patients, especially those with complex discharge needs. Often patients admitted for “nonmedical” reasons do not have the ability to discharge to a skilled nursing facility, long-term care facility, or home due to lack of insurance coverage or resources and/or assistance. Care managers can help you creatively problem solve and coordinate care. Physician advisors are your allies in helping create system-level interventions that might avert some of these “nonmedical” admissions. Consider involving both care managers and physician advisors early in the admission to help navigate social complexities.

How can hospitalists get involved?

According to CMS, the decision on “whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital … can typically be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”3 In reality, this is not black and white. The “2 midnights” has brought a host of new challenges for hospitals, hospitalists, and patients to navigate. The Society of Hospital Medicine released an Observation White Paper in 2017 challenging the status quo and proposing comprehensive observation reform.4

We encourage hospital medicine providers to more routinely engage with their institutional physician advisors and consider joining the SHM Public Policy Committee to become more involved in advocacy, and/or consider becoming a physician advisor.

Dr. Singh is physician advisor for Utilization & CM in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the university. Dr. Anoff is director of clinical operations and director of nights for the Hospital Medicine Group at the University of Colorado at Denver. Dr. Stella is a hospitalist at Denver Health and Hospital Authority and an associate professor of medicine at the university.

References

1. What is a physician advisor? 2017 Oct 9.

2. Barry P. Medicare: Inpatient or outpatient. AARP Bulletin. 2012 Oct.

3. Goldberg TH. The long-term and post-acute care continuum. WV Med J. 2014 Nov-Dec;10(6):24-30.

4. Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee. The hospital observation care problem. Perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2017 Sep.

The practice of hospital medicine is rapidly changing. Higher-acuity patients are being admitted to hospitals already struggling with capacity, and hospitalists are being instructed to pay attention to length of stay, improve their documentation and billing, and participate in initiatives to improve hospital throughput, all while delivering high-quality patient care.

As hospitalists and SHM members who are also physician advisors, we have a unique understanding of these pressures. In this article, we answer common questions we receive from hospitalists regarding utilization management, care coordination, clinical documentation, and CMS regulations.

Why do physician advisors exist, and what do they do?

A physician advisor is hired by the hospital to act as a liaison between the hospital administration, clinical staff, and support personnel in order to ensure regulatory compliance, advise physicians on medical necessity, and assist hospital leadership in meeting overall organizational goals related to the efficient utilization of health care services.1

Given their deep knowledge of hospital systems and processes, and ability to collaborate and teach, hospitalists are well-positioned to serve in this capacity. Our primary goal as physician advisors is to help physicians continue to focus on the parts of medicine they enjoy – clinical care, education, quality improvement, research etc. – by helping to demystify complex regulatory requirements and by creating streamlined processes to make following these requirements easier.

Why does this matter?

We understand that regulatory and hospital systems issues such as patient class determination, appropriate clinical documentation, and hospital throughput and capacity management can feel tedious, and sometimes overwhelming, to busy hospitalists. While it is easy to attribute these problems solely to hospitals’ desire for increased revenue, these issues directly impact the quality of care we provide to their patients.

In addition, our entire financial system is predicated on appropriate health care resource utilization, financial reimbursement, demonstration of medical acuity, and our impact on the care of a patient. Thus, our ability to advocate for our patients and for ourselves is directly connected with this endeavor. Developing a working knowledge of regulatory and systems issues allows hospitalists to be more engaged in leadership and negotiations and allows us to advocate for resources we deem most important.

Why are clinical documentation integrity teams so important?

Accurately and specifically describing how sick your patients are helps ensure that hospitals are reimbursed appropriately, coded data is accurate for research purposes, quality metrics are attributed correctly, and patients receive the correct diagnoses.

Clarification of documentation and/or addressing “clinical validity” of a given diagnosis (e.g., acute hypoxic respiratory failure requires both hypoxia and respiratory distress) may support an increase or result in a decrease in hospital reimbursement. For example, if the reason for a patient’s admission is renal failure, renal failure with true acute hypoxic respiratory failure will be reimbursed at a rate 40% higher than renal failure without the documentation of other conditions that reflect how ill the patient really is. The patient with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (or other major comorbid condition) is genuinely sicker, thus requiring more time (length of stay) and resources (deserved higher reimbursement).

What is the two-midnight rule, and why does it matter?

In October of 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initiated the two-midnight rule, which states a Medicare patient can be an “inpatient” class if the admitting provider determines that 1) the patient requires medically necessary care which cannot be provided outside the hospital and 2) the patient is expected to stay at least 2 midnights in the hospital.

If, at the time of admission, an admitting provider thinks it is likely that the patient may be discharged prior to 2 midnights, then outpatient care with “observation” designation is appropriate. Incorrect patient class assignment may result in significant adverse consequences for hospitals, including improper patient billing, decreased hospital reimbursement, substantial risk for external auditing, violation of Medicare conditions of participation, and even loss of accreditation.

Who can I talk to if I have a question about a patient’s class? What should I do if I disagree with the class assigned to my patient?

The Utilization Management team typically consists of nurses and physician advisors specifically trained in UM. This team functions as a liaison between providers and payers (particularly Medicare and Medicaid) regarding medical necessity, appropriateness of care received, and efficiency of health care services.

When it comes to discussions about patient class, start by learning more about why the determination was made. The most common reason for patient class disagreements is simply that the documentation does not reflect the severity of illness or accurately reflect the care the patient is receiving. Your documentation should communicate that your patient needs services that only the hospital can provide, and/or they need monitoring that must be done in the hospital to meet the medical necessity criteria that CMS requires for a patient to be “inpatient” class.

If you disagree with a determination provided by the UM nurse and/or physician advisor, then the case will be presented to the hospital UM committee for further review. Two physicians from the UM committee must review the case and provide their own determinations of patient status, and whichever admission determination has two votes is the one that is appropriate.

How do I talk to patients about class determinations?

As media coverage continues about the two-midnight rule and the impact this has on patients, providers should expect more questions about class determination from their patients.

An AARP Bulletin article from 2012 advised patients to “ask [their] own doctor whether observation status is justified … and if not ask him or her to call the hospital to explain the medical reasons why they should be admitted as inpatient.”2 Patients should be informed that providers understand the implications of patient class determinations and are making these decisions as outlined by CMS.

We recommend informing patients that the decision about whether a patient is “inpatient” or “outpatient with observation” class is complex and involves taking into consideration a patient’s medical history, the severity of their current medical condition, need for diagnostic testing, and degree of health resource utilization, as well as a provider’s medical opinion of the risk of an adverse event occurring.

Is it true that observation patients receive higher hospital bills?

It is a common misperception that a designation of “observation” class means that a patient’s medical bill will be higher than “inpatient” class. In 2016, CMS changed the way observation class patients are billed so that, in most scenarios, patients do not receive a higher hospital bill when placed in “observation” class.

How do I approach a denial from a payer?

Commercial payers review all hospitalizations for medical necessity and appropriateness of care received during a patient’s hospitalization. If you receive notice that all or part of your patient’s hospital stay was denied coverage, you have the option of discussing the case with the medical director of the insurance company – this is called a peer-to-peer discussion.

We recommend reviewing the patient’s case and your documentation of the care you provided prior to the peer to peer, especially since these denials may come weeks to months after you have cared for the patient. Begin your conversation by learning why the insurance company denied coverage of the stay and then provide an accurate portrayal of the acuity of illness of the patient, and the resources your hospital used in caring for them. Consider consulting with your hospital’s physician advisor for other high-yield tips.

How can care management help with ‘nonmedical’ hospitalizations?

Care managers are your allies for all patients, especially those with complex discharge needs. Often patients admitted for “nonmedical” reasons do not have the ability to discharge to a skilled nursing facility, long-term care facility, or home due to lack of insurance coverage or resources and/or assistance. Care managers can help you creatively problem solve and coordinate care. Physician advisors are your allies in helping create system-level interventions that might avert some of these “nonmedical” admissions. Consider involving both care managers and physician advisors early in the admission to help navigate social complexities.

How can hospitalists get involved?

According to CMS, the decision on “whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital … can typically be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”3 In reality, this is not black and white. The “2 midnights” has brought a host of new challenges for hospitals, hospitalists, and patients to navigate. The Society of Hospital Medicine released an Observation White Paper in 2017 challenging the status quo and proposing comprehensive observation reform.4

We encourage hospital medicine providers to more routinely engage with their institutional physician advisors and consider joining the SHM Public Policy Committee to become more involved in advocacy, and/or consider becoming a physician advisor.

Dr. Singh is physician advisor for Utilization & CM in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the university. Dr. Anoff is director of clinical operations and director of nights for the Hospital Medicine Group at the University of Colorado at Denver. Dr. Stella is a hospitalist at Denver Health and Hospital Authority and an associate professor of medicine at the university.

References

1. What is a physician advisor? 2017 Oct 9.

2. Barry P. Medicare: Inpatient or outpatient. AARP Bulletin. 2012 Oct.

3. Goldberg TH. The long-term and post-acute care continuum. WV Med J. 2014 Nov-Dec;10(6):24-30.

4. Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee. The hospital observation care problem. Perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2017 Sep.

The practice of hospital medicine is rapidly changing. Higher-acuity patients are being admitted to hospitals already struggling with capacity, and hospitalists are being instructed to pay attention to length of stay, improve their documentation and billing, and participate in initiatives to improve hospital throughput, all while delivering high-quality patient care.

As hospitalists and SHM members who are also physician advisors, we have a unique understanding of these pressures. In this article, we answer common questions we receive from hospitalists regarding utilization management, care coordination, clinical documentation, and CMS regulations.

Why do physician advisors exist, and what do they do?

A physician advisor is hired by the hospital to act as a liaison between the hospital administration, clinical staff, and support personnel in order to ensure regulatory compliance, advise physicians on medical necessity, and assist hospital leadership in meeting overall organizational goals related to the efficient utilization of health care services.1

Given their deep knowledge of hospital systems and processes, and ability to collaborate and teach, hospitalists are well-positioned to serve in this capacity. Our primary goal as physician advisors is to help physicians continue to focus on the parts of medicine they enjoy – clinical care, education, quality improvement, research etc. – by helping to demystify complex regulatory requirements and by creating streamlined processes to make following these requirements easier.

Why does this matter?

We understand that regulatory and hospital systems issues such as patient class determination, appropriate clinical documentation, and hospital throughput and capacity management can feel tedious, and sometimes overwhelming, to busy hospitalists. While it is easy to attribute these problems solely to hospitals’ desire for increased revenue, these issues directly impact the quality of care we provide to their patients.

In addition, our entire financial system is predicated on appropriate health care resource utilization, financial reimbursement, demonstration of medical acuity, and our impact on the care of a patient. Thus, our ability to advocate for our patients and for ourselves is directly connected with this endeavor. Developing a working knowledge of regulatory and systems issues allows hospitalists to be more engaged in leadership and negotiations and allows us to advocate for resources we deem most important.

Why are clinical documentation integrity teams so important?

Accurately and specifically describing how sick your patients are helps ensure that hospitals are reimbursed appropriately, coded data is accurate for research purposes, quality metrics are attributed correctly, and patients receive the correct diagnoses.

Clarification of documentation and/or addressing “clinical validity” of a given diagnosis (e.g., acute hypoxic respiratory failure requires both hypoxia and respiratory distress) may support an increase or result in a decrease in hospital reimbursement. For example, if the reason for a patient’s admission is renal failure, renal failure with true acute hypoxic respiratory failure will be reimbursed at a rate 40% higher than renal failure without the documentation of other conditions that reflect how ill the patient really is. The patient with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (or other major comorbid condition) is genuinely sicker, thus requiring more time (length of stay) and resources (deserved higher reimbursement).

What is the two-midnight rule, and why does it matter?

In October of 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initiated the two-midnight rule, which states a Medicare patient can be an “inpatient” class if the admitting provider determines that 1) the patient requires medically necessary care which cannot be provided outside the hospital and 2) the patient is expected to stay at least 2 midnights in the hospital.

If, at the time of admission, an admitting provider thinks it is likely that the patient may be discharged prior to 2 midnights, then outpatient care with “observation” designation is appropriate. Incorrect patient class assignment may result in significant adverse consequences for hospitals, including improper patient billing, decreased hospital reimbursement, substantial risk for external auditing, violation of Medicare conditions of participation, and even loss of accreditation.

Who can I talk to if I have a question about a patient’s class? What should I do if I disagree with the class assigned to my patient?

The Utilization Management team typically consists of nurses and physician advisors specifically trained in UM. This team functions as a liaison between providers and payers (particularly Medicare and Medicaid) regarding medical necessity, appropriateness of care received, and efficiency of health care services.

When it comes to discussions about patient class, start by learning more about why the determination was made. The most common reason for patient class disagreements is simply that the documentation does not reflect the severity of illness or accurately reflect the care the patient is receiving. Your documentation should communicate that your patient needs services that only the hospital can provide, and/or they need monitoring that must be done in the hospital to meet the medical necessity criteria that CMS requires for a patient to be “inpatient” class.

If you disagree with a determination provided by the UM nurse and/or physician advisor, then the case will be presented to the hospital UM committee for further review. Two physicians from the UM committee must review the case and provide their own determinations of patient status, and whichever admission determination has two votes is the one that is appropriate.

How do I talk to patients about class determinations?

As media coverage continues about the two-midnight rule and the impact this has on patients, providers should expect more questions about class determination from their patients.

An AARP Bulletin article from 2012 advised patients to “ask [their] own doctor whether observation status is justified … and if not ask him or her to call the hospital to explain the medical reasons why they should be admitted as inpatient.”2 Patients should be informed that providers understand the implications of patient class determinations and are making these decisions as outlined by CMS.

We recommend informing patients that the decision about whether a patient is “inpatient” or “outpatient with observation” class is complex and involves taking into consideration a patient’s medical history, the severity of their current medical condition, need for diagnostic testing, and degree of health resource utilization, as well as a provider’s medical opinion of the risk of an adverse event occurring.

Is it true that observation patients receive higher hospital bills?

It is a common misperception that a designation of “observation” class means that a patient’s medical bill will be higher than “inpatient” class. In 2016, CMS changed the way observation class patients are billed so that, in most scenarios, patients do not receive a higher hospital bill when placed in “observation” class.

How do I approach a denial from a payer?

Commercial payers review all hospitalizations for medical necessity and appropriateness of care received during a patient’s hospitalization. If you receive notice that all or part of your patient’s hospital stay was denied coverage, you have the option of discussing the case with the medical director of the insurance company – this is called a peer-to-peer discussion.

We recommend reviewing the patient’s case and your documentation of the care you provided prior to the peer to peer, especially since these denials may come weeks to months after you have cared for the patient. Begin your conversation by learning why the insurance company denied coverage of the stay and then provide an accurate portrayal of the acuity of illness of the patient, and the resources your hospital used in caring for them. Consider consulting with your hospital’s physician advisor for other high-yield tips.

How can care management help with ‘nonmedical’ hospitalizations?

Care managers are your allies for all patients, especially those with complex discharge needs. Often patients admitted for “nonmedical” reasons do not have the ability to discharge to a skilled nursing facility, long-term care facility, or home due to lack of insurance coverage or resources and/or assistance. Care managers can help you creatively problem solve and coordinate care. Physician advisors are your allies in helping create system-level interventions that might avert some of these “nonmedical” admissions. Consider involving both care managers and physician advisors early in the admission to help navigate social complexities.

How can hospitalists get involved?

According to CMS, the decision on “whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital … can typically be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”3 In reality, this is not black and white. The “2 midnights” has brought a host of new challenges for hospitals, hospitalists, and patients to navigate. The Society of Hospital Medicine released an Observation White Paper in 2017 challenging the status quo and proposing comprehensive observation reform.4

We encourage hospital medicine providers to more routinely engage with their institutional physician advisors and consider joining the SHM Public Policy Committee to become more involved in advocacy, and/or consider becoming a physician advisor.

Dr. Singh is physician advisor for Utilization & CM in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the university. Dr. Anoff is director of clinical operations and director of nights for the Hospital Medicine Group at the University of Colorado at Denver. Dr. Stella is a hospitalist at Denver Health and Hospital Authority and an associate professor of medicine at the university.

References

1. What is a physician advisor? 2017 Oct 9.

2. Barry P. Medicare: Inpatient or outpatient. AARP Bulletin. 2012 Oct.

3. Goldberg TH. The long-term and post-acute care continuum. WV Med J. 2014 Nov-Dec;10(6):24-30.

4. Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee. The hospital observation care problem. Perspectives and solutions from the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2017 Sep.

Hospitalist and Internal Medicine Leaders’ Perspectives of Early Discharge Challenges at Academic Medical Centers

The discharge process is a critical bottleneck for efficient patient flow through the hospital. Delayed discharges translate into delays in admissions and other patient transitions, often leading to excess costs, patient dissatisfaction, and even patient harm.1-3 The emergency department is particularly impacted by these delays; bottlenecks there lead to overcrowding, increased overall hospital length of stay, and increased risks for bad outcomes during hospitalization.2

Academic medical centers in particular may struggle with delayed discharges. In a typical teaching hospital, a team composed of an attending physician and housestaff share responsibility for determining the discharge plan. Additionally, clinical teaching activities may affect the process and quality of discharge.4-6

The prevalence and causes of delayed discharges vary greatly.7-9 To improve efficiency around discharge, many hospitals have launched initiatives designed to discharge patients earlier in the day, including goal setting (“discharge by noon”), scheduling discharge appointments, and using quality-improvement methods, such as Lean Methodology (LEAN), to remove inefficiencies within discharge processes.10-12 However, there are few data on the prevalence and effectiveness of different strategies.

The aim of this study was to survey academic hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders to elicit their perspectives on the factors contributing to discharge timing and the relative importance and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Oversight

We obtained a list of 115 university-affiliated hospitals associated with a residency program and, in most cases, a medical school from Vizient Inc. (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium), an alliance of academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. Each member institution submits clinical data to allow for the benchmarking of outcomes to drive transparency and quality improvement.13 More than 95% of the nation’s academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals participate in this collaborative. Vizient works with members but does not set nor promote quality metrics, such as discharge timeliness. E-mail addresses for hospital medicine physician leaders (eg, division chief) of major academic medical centers were obtained from each institution via publicly available data (eg, the institution’s website). When an institution did not have a hospital medicine section, we identified the division chief of general internal medicine. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Development and Domains

We developed a 30-item survey to evaluate 5 main domains of interest: current discharge practices, degree of prioritization of early discharge on the inpatient service, barriers to timely discharge, prevalence and perceived effectiveness of implemented early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation of early-discharge initiatives.

Respondents were first asked to identify their institutions’ goals for discharge time. They were then asked to compare the priority of early-discharge initiatives to other departmental quality-improvement initiatives, such as reducing 30-day readmissions, improving interpreter use, and improving patient satisfaction. Next, respondents were asked to estimate the degree to which clinical or patient factors contributed to delays in discharge. Respondents were then asked whether specific early-discharge initiatives, such as changes to rounding practices or communication interventions, were implemented at their institutions and, if so, the perceived effectiveness of these initiatives at meeting discharge targets. We piloted the questions locally with physicians and researchers prior to finalizing the survey.

Data Collection

We sent surveys via an online platform (Research Electronic Data Capture).14 Nonresponders were sent 2 e-mail reminders and then a follow-up telephone call asking them to complete the survey. Only 1 survey per academic medical center was collected. Any respondent who completed the survey within 2 weeks of receiving it was entered to win a Kindle Fire.

Data Analysis

We summarized survey responses using descriptive statistics. Analysis was completed in IBM SPSS version 22 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Survey Respondent and Institutional Characteristics

Of the 115 institutions surveyed, we received 61 responses (response rate of 53%), with 39 (64%) respondents from divisions of hospital medicine and 22 (36%) from divisions of general internal medicine. A majority (n = 53; 87%) stated their medicine services have a combination of teaching (with residents) and nonteaching (without residents) teams. Thirty-nine (64%) reported having daily multidisciplinary rounds.

Early Discharge as a Priority

Forty-seven (77%) institutional representatives strongly agreed or agreed that early discharge was a priority, with discharge by noon being the most common target time (n = 23; 38%). Thirty (50%) respondents rated early discharge as more important than improving interpreter use for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions (n = 29; 48%) and improving patient satisfaction (n = 27; 44%).

Factors Delaying Discharge

The most common factors perceived as delaying discharge were considered external to the hospital, such as postacute care bed availability or scheduled (eg, ambulance) transport delays (n = 48; 79%), followed by patient factors such as patient transport issues (n = 44; 72%). Less commonly reported were workflow issues, such as competing primary team priorities or case manager bandwidth (n = 38; 62%; Table 1).

Initiatives to Improve Discharge

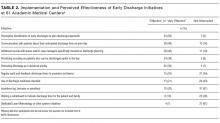

The most commonly implemented initiatives perceived as effective at improving discharge times were the preemptive identification of early discharges to plan discharge paperwork (n = 34; 56%), communication with patients about anticipated discharge time on the day prior to discharge (n = 29; 48%), and the implementation of additional rounds between physician teams and case managers specifically around discharge planning (n = 28; 46%). Initiatives not commonly implemented included regular audit of and feedback on discharge times to providers and teams (n = 21; 34%), the use of a discharge readiness checklist (n = 26; 43%), incentives such as bonuses or penalties (n = 37; 61%), the use of a whiteboard to indicate discharge times (n = 23; 38%), and dedicated quality-improvement approaches such as LEAN (n = 37; 61%; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests early discharge for medicine patients is a priority among academic institutions. Hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders in our study generally attributed delayed discharges to external factors, particularly unavailability of postacute care facilities and transportation delays. Having issues with finding postacute care placements is consistent with previous findings by Selker et al.15 and Carey et al.8 This is despite the 20-year difference between Selker et al.’s study and the current study, reflecting a continued opportunity for improvement, including stronger partnerships with local and regional postacute care facilities to expedite care transition and stronger discharge-planning efforts early in the admission process. Efforts in postacute care placement may be particularly important for Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

Our responders, hospitalist and internal medicine physician leaders, did not perceive the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees to be factors that significantly delayed patient discharge. This is in contrast to previous studies, which attributed delays in discharge to prolonged clinical decision-making related to teaching and supervision.4-6,8 This discrepancy may be due to the fact that we only surveyed single physician leaders at each institution and not residents. Our finding warrants further investigation to understand the degree to which resident skills may impact discharge planning and processes.

Institutions represented in our study have attempted a variety of initiatives promoting earlier discharge, with varying levels of perceived success. Initiatives perceived to be the most effective by hospital leaders centered on 2 main areas: (1) changing individual provider practice and (2) anticipatory discharge preparation. Interestingly, this is in discordance with the main factors labeled as causing delays in discharges, such as obtaining postacute care beds, busy case managers, and competing demands on primary teams. We hypothesize this may be because such changes require organization- or system-level changes and are perceived as more arduous than changes at the individual level. In addition, changes to individual provider behavior may be more cost- and time-effective than more systemic initiatives.

Our findings are consistent with the work published by Wertheimer and colleagues,11 who show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who may be discharged before noon the next day. In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early-discharge rate the following day.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our survey only considers the perspectives of hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders at academic medical centers that are part of the Vizient Inc. collaborative. They do not represent all academic or community-based medical centers. Although the perceived effectiveness of some initiatives was high, we did not collect empirical data to support these claims or to determine which initiative had the greatest relative impact on discharge timeliness. Lastly, we did not obtain resident, nursing, or case manager perspectives on discharge practices. Given their roles as frontline providers, we may have missed these alternative perspectives.

Our study shows there is a strong interest in increasing early discharges in an effort to improve hospital throughput and patient flow.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who completed the survey and Danielle Carrier at Vizient Inc. (formally University HealthSystem Consortium) for her assistance in obtaining data.

Disclosures

Hemali Patel, Margaret Fang, Michelle Mourad, Adrienne Green, Ryan Murphy, and James Harrison report no conflicts of interest. At the time the research was conducted, Robert Wachter reported that he is a member of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation (no compensation except travel expenses); recently chaired an advisory board to England’s National Health Service (NHS) reviewing the NHS’s digital health strategy (no compensation except travel expenses); has a contract with UCSF from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to edit a patient-safety website; receives compensation from John Wiley & Sons for writing a blog; receives royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins and McGraw-Hill Education for writing and/or editing several books; receives stock options for serving on the board of Acuity Medical Management Systems; receives a yearly stipend for serving on the board of The Doctors Company; serves on the scientific advisory boards for amino.com, PatientSafe Solutions Inc., Twine, and EarlySense (for which he receives stock options); has a small royalty stake in CareWeb, a hospital communication tool developed at UCSF; and holds the Marc and Lynne Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine and the Holly Smith Distinguished Professorship in Science and Medicine at UCSF.

1. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Impact of admission and discharge peak times on hospital overcrowding. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:82-88. PubMed

2. White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DFM. Boarding Inpatients in the Emergency Department Increases Discharged Patient Length of Stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):230-235. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. PubMed

3. Derlet RW, Richards JR. Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: complex causes and disturbing effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):63-68. PubMed

4. da Silva SA, Valácio RA, Botelho FC, Amaral CFS. Reasons for discharge delays in teaching hospitals. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014;48(2):314-321. doi:10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004971. PubMed

5. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, Curry L, Bradley EH. “Out of Sight, Out of Mind”: Housestaff Perceptions of Quality-Limiting Factors in Discharge Care at Teaching Hospitals. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376-381. doi:10.1002/jhm.1928. PubMed

6. Goldman J, Reeves S, Wu R, Silver I, MacMillan K, Kitto S. Medical Residents and Interprofessional Interactions in Discharge: An Ethnographic Exploration of Factors That Affect Negotiation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1454-1460. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3306-6. PubMed

7. Okoniewska B, Santana MJ, Groshaus H, et al. Barriers to discharge in an acute care medical teaching unit: a qualitative analysis of health providers’ perceptions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:83-89. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S72633. PubMed

8. Carey MR, Sheth H, Scott Braithwaite R. A Prospective Study of Reasons for Prolonged Hospitalizations on a General Medicine Teaching Service. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):108-115. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40269.x. PubMed

9. Kim CS, Hart AL, Paretti RF, et al. Excess Hospitalization Days in an Academic Medical Center: Perceptions of Hospitalists and Discharge Planners. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(2):e34-e42. http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2011/2011-2-vol17-n2/AJMC_11feb_Kim_WebX_e34to42/. Accessed on October 26, 2016.

10. Gershengorn HB, Kocher R, Factor P. Management Strategies to Effect Change in Intensive Care Units: Lessons from the World of Business. Part II. Quality-Improvement Strategies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):444-453. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-392AS. PubMed

11. Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: An achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi:10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

12. Manning DM, Tammel KJ, Blegen RN, et al. In-room display of day and time patient is anticipated to leave hospital: a “discharge appointment.” J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):13-16. doi:10.1002/jhm.146. PubMed

13. Networks for academic medical centers. https://www.vizientinc.com/Our-networks/Networks-for-academic-medical-centers. Accessed on July 13, 2017.

14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed

15. Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Pauker SG, Kassirer JP. The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days. Med Care. 1989;27(2):112-129. PubMed

The discharge process is a critical bottleneck for efficient patient flow through the hospital. Delayed discharges translate into delays in admissions and other patient transitions, often leading to excess costs, patient dissatisfaction, and even patient harm.1-3 The emergency department is particularly impacted by these delays; bottlenecks there lead to overcrowding, increased overall hospital length of stay, and increased risks for bad outcomes during hospitalization.2

Academic medical centers in particular may struggle with delayed discharges. In a typical teaching hospital, a team composed of an attending physician and housestaff share responsibility for determining the discharge plan. Additionally, clinical teaching activities may affect the process and quality of discharge.4-6

The prevalence and causes of delayed discharges vary greatly.7-9 To improve efficiency around discharge, many hospitals have launched initiatives designed to discharge patients earlier in the day, including goal setting (“discharge by noon”), scheduling discharge appointments, and using quality-improvement methods, such as Lean Methodology (LEAN), to remove inefficiencies within discharge processes.10-12 However, there are few data on the prevalence and effectiveness of different strategies.

The aim of this study was to survey academic hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders to elicit their perspectives on the factors contributing to discharge timing and the relative importance and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Oversight

We obtained a list of 115 university-affiliated hospitals associated with a residency program and, in most cases, a medical school from Vizient Inc. (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium), an alliance of academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. Each member institution submits clinical data to allow for the benchmarking of outcomes to drive transparency and quality improvement.13 More than 95% of the nation’s academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals participate in this collaborative. Vizient works with members but does not set nor promote quality metrics, such as discharge timeliness. E-mail addresses for hospital medicine physician leaders (eg, division chief) of major academic medical centers were obtained from each institution via publicly available data (eg, the institution’s website). When an institution did not have a hospital medicine section, we identified the division chief of general internal medicine. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Development and Domains

We developed a 30-item survey to evaluate 5 main domains of interest: current discharge practices, degree of prioritization of early discharge on the inpatient service, barriers to timely discharge, prevalence and perceived effectiveness of implemented early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation of early-discharge initiatives.

Respondents were first asked to identify their institutions’ goals for discharge time. They were then asked to compare the priority of early-discharge initiatives to other departmental quality-improvement initiatives, such as reducing 30-day readmissions, improving interpreter use, and improving patient satisfaction. Next, respondents were asked to estimate the degree to which clinical or patient factors contributed to delays in discharge. Respondents were then asked whether specific early-discharge initiatives, such as changes to rounding practices or communication interventions, were implemented at their institutions and, if so, the perceived effectiveness of these initiatives at meeting discharge targets. We piloted the questions locally with physicians and researchers prior to finalizing the survey.

Data Collection

We sent surveys via an online platform (Research Electronic Data Capture).14 Nonresponders were sent 2 e-mail reminders and then a follow-up telephone call asking them to complete the survey. Only 1 survey per academic medical center was collected. Any respondent who completed the survey within 2 weeks of receiving it was entered to win a Kindle Fire.

Data Analysis

We summarized survey responses using descriptive statistics. Analysis was completed in IBM SPSS version 22 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Survey Respondent and Institutional Characteristics

Of the 115 institutions surveyed, we received 61 responses (response rate of 53%), with 39 (64%) respondents from divisions of hospital medicine and 22 (36%) from divisions of general internal medicine. A majority (n = 53; 87%) stated their medicine services have a combination of teaching (with residents) and nonteaching (without residents) teams. Thirty-nine (64%) reported having daily multidisciplinary rounds.

Early Discharge as a Priority

Forty-seven (77%) institutional representatives strongly agreed or agreed that early discharge was a priority, with discharge by noon being the most common target time (n = 23; 38%). Thirty (50%) respondents rated early discharge as more important than improving interpreter use for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions (n = 29; 48%) and improving patient satisfaction (n = 27; 44%).

Factors Delaying Discharge

The most common factors perceived as delaying discharge were considered external to the hospital, such as postacute care bed availability or scheduled (eg, ambulance) transport delays (n = 48; 79%), followed by patient factors such as patient transport issues (n = 44; 72%). Less commonly reported were workflow issues, such as competing primary team priorities or case manager bandwidth (n = 38; 62%; Table 1).

Initiatives to Improve Discharge