User login

A Prescription for Note Bloat: An Effective Progress Note Template

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has led to significant progress in the modernization of healthcare delivery. Ease of access has improved clinical efficiency, and digital data have allowed for point-of-care decision support tools ranging from predicting the 30-day risk of readmission to providing up-to-date guidelines for the care of various diseases.1,2 Documentation tools such as copy-forward and autopopulation increase the speed of documentation, and typed notes improve legibility and ease of note transmission.3,4

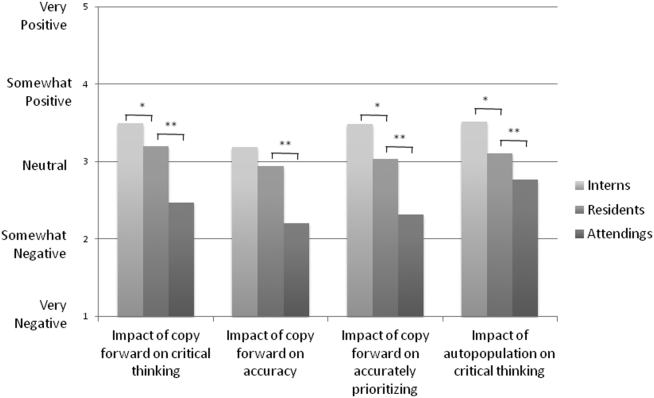

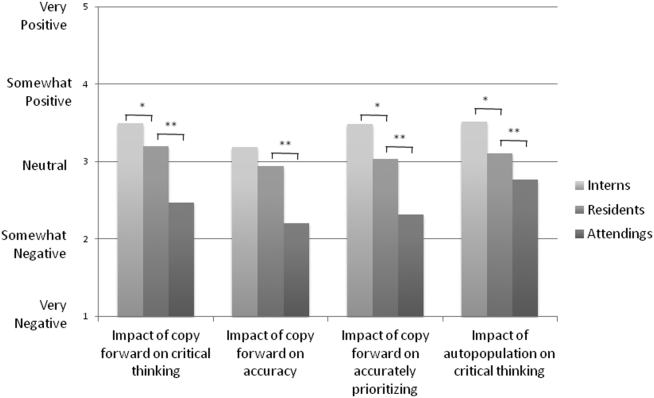

However, all of these benefits come with a potential for harm, particularly with respect to accurate and concise documentation. Many experts have described the perpetuation of false information leading to errors, copying-forward of inconsistent and outdated information, and the phenomenon of “note bloat” — physician notes that contain multiple pages of nonessential information, often leaving key aspects buried or lost.5-7 Providers seem to recognize the hazards of copy-and-paste functionality yet persist in utilizing it. In 1 survey, more than 70% of attendings and residents felt that copy and paste led to inaccurate and outdated information, yet 80% stated they would still use it.8

There is little evidence to guide institutions on ways to improve EHR documentation practices. Recent studies have shown that operative note templates improved documentation and decreased the number of missing components.9,10 In the nonoperative setting, 1 small pilot study of pediatric interns demonstrated that a bundled intervention composed of a note template and classroom teaching resulted in improvement in overall note quality and a decrease in “note clutter.”11 In a larger study of pediatric residents, a standardized and simplified note template resulted in a shorter note, although notes were completed later in the day.12 The present study seeks to build upon these efforts by investigating the effect of didactic teaching and an electronic progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness across 4 academic internal medicine residency programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective quality improvement study took place across 4 academic institutions: University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of California San Diego (UCSD), and University of Iowa, all of which use Epic EHR (Epic Corp., Madison, WI). The intervention combined brief educational conferences directed at housestaff and attendings with the implementation of an electronic progress note template. Guided by resident input, a note-writing task force at UCSF and UCLA developed a set of best practice guidelines and an aligned note template for progress notes (supplementary Appendix 1). UCSD and the University of Iowa adopted them at their respective institutions. The template’s design minimized autopopulation while encouraging providers to enter relevant data via free text fields (eg, physical exam), prompts (eg, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…”), and drop-down menus (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] prophylaxis: enoxaparin, heparin subcutaneously, etc; supplementary Appendix 2). Additionally, an inpatient checklist was included at the end of the note to serve as a reminder for key inpatient concerns and quality measures, such as Foley catheter days, discharge planning, and code status. Lectures that focused on issues with documentation in the EHR, the best practice guidelines, and a review of the note template with instructions on how to access it were presented to the housestaff. Each institution tailored the lecture to suit their culture. Housestaff were encouraged but not required to use the note template.

Selection and Grading of Progress Notes

Progress notes were eligible for the study if they were written by an intern on an internal medicine teaching service, from a patient with a hospitalization length of at least 3 days with a progress note selected from hospital day 2 or 3, and written while the patient was on the general medicine wards. The preintervention notes were authored from September 2013 to December 2013 and the postintervention notes from April 2014 to June 2014. One note was selected per patient and no more than 3 notes were selected per intern. Each institution selected the first 50 notes chronologically that met these criteria for both the preintervention and the postintervention periods, for a total of 400 notes. The note-grading tool consisted of the following 3 sections to analyze note quality: (1) a general impression of the note (eg, below average, average, above average); (2) the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9) that evaluates notes on 9 domains (up to date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely); and (3) a note competency questionnaire based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency note checklist that asked yes or no questions about best practice elements (eg, is there a relevant and focused physical exam).12

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

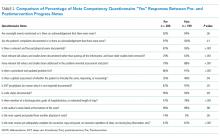

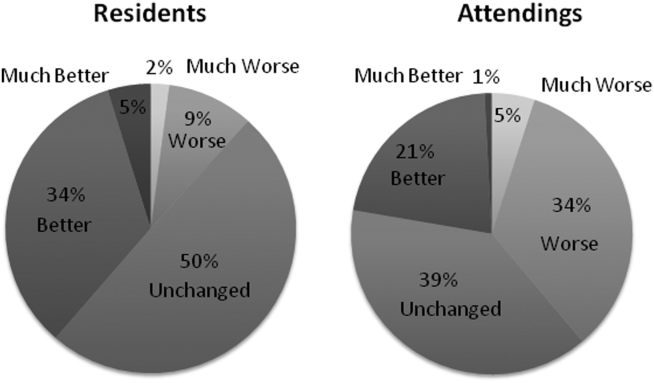

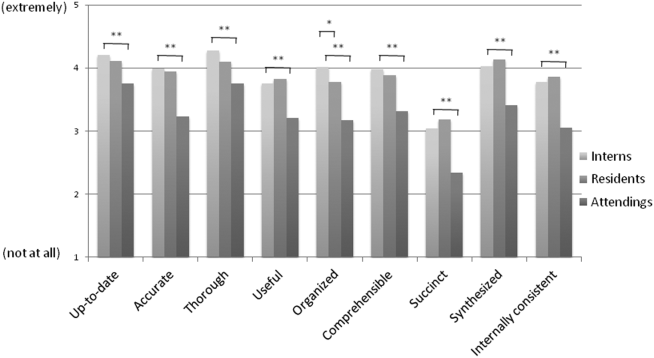

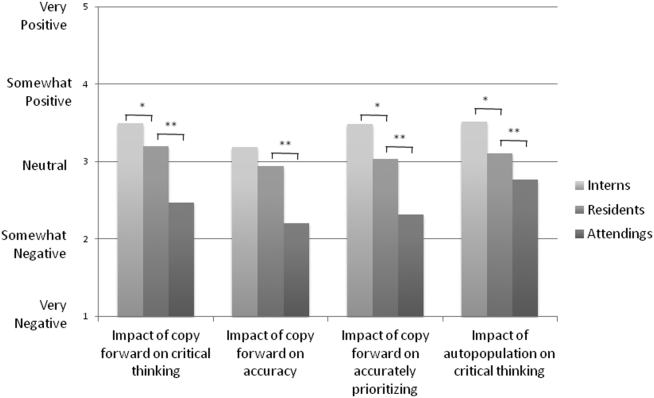

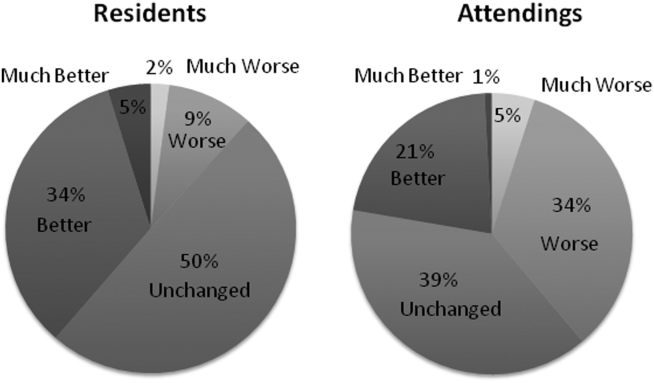

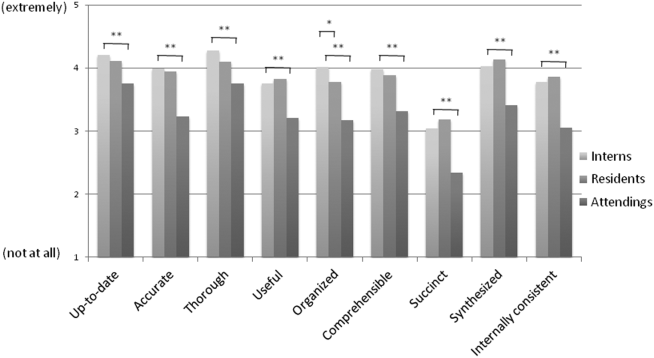

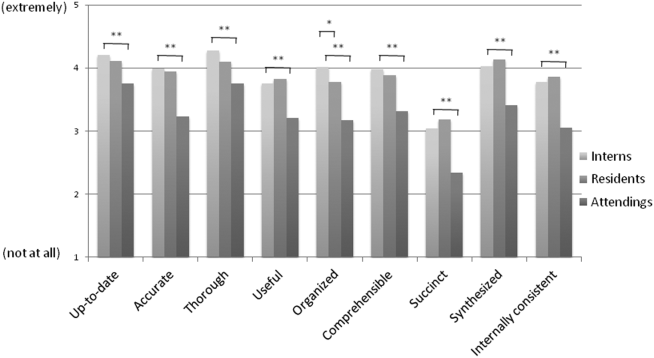

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

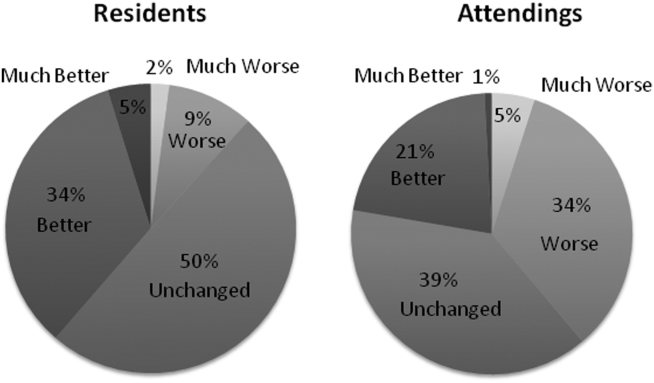

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

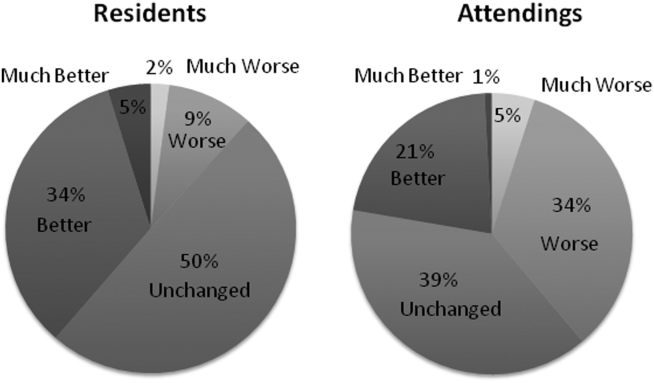

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07

DISCUSSION

A bundled intervention consisting of educational lectures and a best practice progress note template significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier completion of inpatient progress notes. These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated that a bundled note template intervention improved total note score and reduced note clutter.11 We saw a broad improvement in progress notes across all 9 domains of the PDQI-9, which corresponded with an improved general impression score. We also found statistically significant improvements in 7 of the 13 categories of the competency questionnaire.

Arguably the greatest impact of the intervention was shortening the documentation of labs and studies. Autopopulation can lead to the appearance of a comprehensive note; however, key data are often lost in a sea of numbers and imaging reports.6,14 Using simple prompts followed by free text such as, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…” reduced autopopulation and reminded housestaff to identify only the key information that affected patient care for that day, resulting in a more streamlined, clear, and high-yield note.

The time spent documenting care is an important consideration for physician workflow and for uptake of any note intervention.14-18 One study from 2016 revealed that internal medicine housestaff spend more than half of an average shift using the computer, with 52% of that time spent on documentation.17 Although functions such as autopopulation and copy-forward were created as efficiency tools, we hypothesize that they may actually prolong note writing time by leading to disorganized, distended notes that are difficult to use the following day. There was concern that limiting these “efficiency functions” might discourage housestaff from using the progress note template. It was encouraging to find that postintervention notes were signed 1.3 hours earlier in the day. This study did not measure the impact of shorter notes and earlier completion time, but in theory, this could allow interns to spend more time in direct patient care and to be at lower risk of duty hour violations.19 Furthermore, while the clinical impact of this is unknown, it is possible that timely note completion may improve patient care by making notes available earlier for consultants and other members of the care team.

We found that adding an “inpatient checklist” to the progress note template facilitated a review of key inpatient concerns and quality measures. Although we did not specifically compare before-and-after documentation of all of the components of the checklist, there appeared to be improvement in the domains measured. Notably, there was a 31% increase (P < .001) in the percentage of notes documenting the “discharge plan, goals of hospitalization, or estimated length of stay.” In the surgical literature, studies have demonstrated that incorporating checklists improves patient safety, the delivery of care, and potentially shortens the length of stay.20-22 Future studies should explore the impact of adding a checklist to the daily progress note, as there may be potential to improve both process and outcome measures.

Institution-specific data provided insightful results. UCSD encountered low template use among their interns; however, they still had evidence of improvement in note quality, though not at the same level of UCLA and UCSF. Some barriers to uptake identified were as follows: (1) interns were accustomed to import labs and studies into their note to use as their rounding report, and (2) the intervention took place late in the year when interns had developed a functional writing system that they were reluctant to change. The University of Iowa did not show significant improvement in their note quality despite a relatively high template uptake. Both of these outcomes raise the possibility that in addition to the template, there were other factors at play. Perhaps because UCSF and UCLA created the best practice guidelines and template, it was a better fit for their culture and they had more institutional buy-in. Or because the educational lectures were similar, but not standardized across institutions, some lectures may have been more effective than others. However, when evaluating the postintervention notes at UCSD and Iowa, templated notes were found to be much more likely to score higher on the PDQI-9 than nontemplated notes, which serves as evidence of the efficacy of the note template.

Some of the strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size spanning 4 institutions and the use of 3 different assessment tools for grading progress note quality (general impression score, PDQI-9, and competency note questionnaire). An additional strength is our unique finding suggesting that note writing may be more efficient by removing, rather than adding, “efficiency functions.” There were several limitations of this study. Pre- and postintervention notes were examined at different points in the same academic year, thus certain domains may have improved as interns progressed in clinical skill and comfort with documentation, independent of our intervention.21 However, our analysis of postintervention notes across the same time period revealed that use of the template was strongly associated with higher quality, shorter notes and earlier completion time arguing that the effect seen was not merely intern experience. The poor interrater reliability is also a limitation. Although the PDQI-9 was previously validated, future use of the grading tool may require more rater training for calibration or more objective wording.23 The study was not blinded, and thus, bias may have falsely elevated postintervention scores; however, we attempted to minimize bias by incorporating a more objective yes/no competency questionnaire and by having each note scored by 3 graders. Other studies have attempted to address this form of bias by printing out notes and blinding the graders. This design, however, isolates the note from all other data in the medical record, making it difficult to assess domains such as accuracy and completeness. Our inclusion of objective outcomes such as note length and time of note completion help to mitigate some of the bias.

Future research can expand on the results of this study by introducing similar progress note interventions at other institutions and/or in nonacademic environments to validate the results and expand generalizability. Longer term follow-up would be useful to determine if these effects are transient or long lasting. Similarly, it would be interesting to determine if such results are sustained even after new interns start suggesting that institutional culture can be changed. Investigators could focus on similar projects to improve other notes that are particularly at a high risk for propagating false information, such as the History and Physical or Discharge Summary. Future research should also focus on outcomes data, including whether a more efficient note can allow housestaff to spend more time with patients, decrease patient length of stay, reduce clinical errors, and improve educational time for trainees. Lastly, we should determine if interventions such as this can mitigate the widespread frustrations with electronic documentation that are associated with physician and provider burnout.15,24 One would hope that the technology could be harnessed to improve provider productivity and be effectively integrated into comprehensive patient care.

Our research makes progress toward recommendations made by the American College of Physicians “to improve accuracy of information recorded and the value of information,” and develop automated tools that “enhance documentation quality without facilitating improper behaviors.”19 Institutions should consider developing internal best practices for clinical documentation and building structured note templates.19 Our research would suggest that, combined with a small educational intervention, such templates can make progress notes more accurate and succinct, make note writing more efficient, and be harnessed to improve quality metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Pfeffer, MD, and Sitaram Vangala, MS, for their contributions to and support of this research study and manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Herzig SJ, Guess JR, Feinbloom DB, et al. Improving appropriateness of acid-suppressive medication use via computerized clinical decision support. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):41-45. PubMed

2. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Predicting all-cause readmissions using electronic health record data from the entire hospitalization: Model development and comparison. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):473-480. PubMed

3. Donati A, Gabbanelli V, Pantanetti S, et al. The impact of a clinical information system in an intensive care unit. J Clin Monit Comput. 2008;22(1):31-36. PubMed

4. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1066-1069. PubMed

5. Hartzband P, Groopman J. Off the record--avoiding the pitfalls of going electronic. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1656-1658. PubMed

6. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. Copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336. PubMed

7. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. John Lennon’s elbow. JAMA. 2012;308(5):463-464. PubMed

8. O’Donnell HC, Kaushal R, Barrón Y, Callahan MA, Adelman RD, Siegler EL. Physicians’ attitudes towards copy and pasting in electronic note writing. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):63-68. PubMed

9. Mahapatra P, Ieong E. Improving Documentation and Communication Using Operative Note Proformas. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u209122.w3712. PubMed

10. Thomson DR, Baldwin MJ, Bellini MI, Silva MA. Improving the quality of operative notes for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Assessing the impact of a standardized operation note proforma. Int J Surg. 2016;27:17-20. PubMed

11. Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):104-107. PubMed

12. Aylor M, Campbell EM, Winter C, Phillipi CA. Resident Notes in an Electronic Health Record: A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Standardized Intervention With Qualitative Analysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;6(3):257-262.

13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. PubMed

14. Chi J, Kugler J, Chu IM, et al. Medical students and the electronic health record: ‘an epic use of time’. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):891-895. PubMed

15. Martin SA, Sinsky CA. The map is not the territory: medical records and 21st century practice. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2053-2056. PubMed

16. Oxentenko AS, Manohar CU, McCoy CP, et al. Internal medicine residents’ computer use in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):529-532. PubMed

17. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How Do Residents Spend Their Shift Time? A Time and Motion Study With a Particular Focus on the Use of Computers. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):827-832. PubMed

18. Chen L, Guo U, Illipparambil LC, et al. Racing Against the Clock: Internal Medicine Residents’ Time Spent On Electronic Health Records. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):39-44. PubMed

19. Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T, Physicians MICotACo. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):301-303. PubMed

20. Treadwell JR, Lucas S, Tsou AY. Surgical checklists: a systematic review of impacts and implementation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):299-318. PubMed

21. Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings--limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:211. PubMed

22. Diaz-Montes TP, Cobb L, Ibeanu OA, Njoku P, Gerardi MA. Introduction of checklists at daily progress notes improves patient care among the gynecological oncology service. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(4):189-193. PubMed

23. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing Electronic Note Quality Using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. PubMed

24. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. PubMed

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has led to significant progress in the modernization of healthcare delivery. Ease of access has improved clinical efficiency, and digital data have allowed for point-of-care decision support tools ranging from predicting the 30-day risk of readmission to providing up-to-date guidelines for the care of various diseases.1,2 Documentation tools such as copy-forward and autopopulation increase the speed of documentation, and typed notes improve legibility and ease of note transmission.3,4

However, all of these benefits come with a potential for harm, particularly with respect to accurate and concise documentation. Many experts have described the perpetuation of false information leading to errors, copying-forward of inconsistent and outdated information, and the phenomenon of “note bloat” — physician notes that contain multiple pages of nonessential information, often leaving key aspects buried or lost.5-7 Providers seem to recognize the hazards of copy-and-paste functionality yet persist in utilizing it. In 1 survey, more than 70% of attendings and residents felt that copy and paste led to inaccurate and outdated information, yet 80% stated they would still use it.8

There is little evidence to guide institutions on ways to improve EHR documentation practices. Recent studies have shown that operative note templates improved documentation and decreased the number of missing components.9,10 In the nonoperative setting, 1 small pilot study of pediatric interns demonstrated that a bundled intervention composed of a note template and classroom teaching resulted in improvement in overall note quality and a decrease in “note clutter.”11 In a larger study of pediatric residents, a standardized and simplified note template resulted in a shorter note, although notes were completed later in the day.12 The present study seeks to build upon these efforts by investigating the effect of didactic teaching and an electronic progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness across 4 academic internal medicine residency programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective quality improvement study took place across 4 academic institutions: University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of California San Diego (UCSD), and University of Iowa, all of which use Epic EHR (Epic Corp., Madison, WI). The intervention combined brief educational conferences directed at housestaff and attendings with the implementation of an electronic progress note template. Guided by resident input, a note-writing task force at UCSF and UCLA developed a set of best practice guidelines and an aligned note template for progress notes (supplementary Appendix 1). UCSD and the University of Iowa adopted them at their respective institutions. The template’s design minimized autopopulation while encouraging providers to enter relevant data via free text fields (eg, physical exam), prompts (eg, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…”), and drop-down menus (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] prophylaxis: enoxaparin, heparin subcutaneously, etc; supplementary Appendix 2). Additionally, an inpatient checklist was included at the end of the note to serve as a reminder for key inpatient concerns and quality measures, such as Foley catheter days, discharge planning, and code status. Lectures that focused on issues with documentation in the EHR, the best practice guidelines, and a review of the note template with instructions on how to access it were presented to the housestaff. Each institution tailored the lecture to suit their culture. Housestaff were encouraged but not required to use the note template.

Selection and Grading of Progress Notes

Progress notes were eligible for the study if they were written by an intern on an internal medicine teaching service, from a patient with a hospitalization length of at least 3 days with a progress note selected from hospital day 2 or 3, and written while the patient was on the general medicine wards. The preintervention notes were authored from September 2013 to December 2013 and the postintervention notes from April 2014 to June 2014. One note was selected per patient and no more than 3 notes were selected per intern. Each institution selected the first 50 notes chronologically that met these criteria for both the preintervention and the postintervention periods, for a total of 400 notes. The note-grading tool consisted of the following 3 sections to analyze note quality: (1) a general impression of the note (eg, below average, average, above average); (2) the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9) that evaluates notes on 9 domains (up to date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely); and (3) a note competency questionnaire based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency note checklist that asked yes or no questions about best practice elements (eg, is there a relevant and focused physical exam).12

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07

DISCUSSION

A bundled intervention consisting of educational lectures and a best practice progress note template significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier completion of inpatient progress notes. These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated that a bundled note template intervention improved total note score and reduced note clutter.11 We saw a broad improvement in progress notes across all 9 domains of the PDQI-9, which corresponded with an improved general impression score. We also found statistically significant improvements in 7 of the 13 categories of the competency questionnaire.

Arguably the greatest impact of the intervention was shortening the documentation of labs and studies. Autopopulation can lead to the appearance of a comprehensive note; however, key data are often lost in a sea of numbers and imaging reports.6,14 Using simple prompts followed by free text such as, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…” reduced autopopulation and reminded housestaff to identify only the key information that affected patient care for that day, resulting in a more streamlined, clear, and high-yield note.

The time spent documenting care is an important consideration for physician workflow and for uptake of any note intervention.14-18 One study from 2016 revealed that internal medicine housestaff spend more than half of an average shift using the computer, with 52% of that time spent on documentation.17 Although functions such as autopopulation and copy-forward were created as efficiency tools, we hypothesize that they may actually prolong note writing time by leading to disorganized, distended notes that are difficult to use the following day. There was concern that limiting these “efficiency functions” might discourage housestaff from using the progress note template. It was encouraging to find that postintervention notes were signed 1.3 hours earlier in the day. This study did not measure the impact of shorter notes and earlier completion time, but in theory, this could allow interns to spend more time in direct patient care and to be at lower risk of duty hour violations.19 Furthermore, while the clinical impact of this is unknown, it is possible that timely note completion may improve patient care by making notes available earlier for consultants and other members of the care team.

We found that adding an “inpatient checklist” to the progress note template facilitated a review of key inpatient concerns and quality measures. Although we did not specifically compare before-and-after documentation of all of the components of the checklist, there appeared to be improvement in the domains measured. Notably, there was a 31% increase (P < .001) in the percentage of notes documenting the “discharge plan, goals of hospitalization, or estimated length of stay.” In the surgical literature, studies have demonstrated that incorporating checklists improves patient safety, the delivery of care, and potentially shortens the length of stay.20-22 Future studies should explore the impact of adding a checklist to the daily progress note, as there may be potential to improve both process and outcome measures.

Institution-specific data provided insightful results. UCSD encountered low template use among their interns; however, they still had evidence of improvement in note quality, though not at the same level of UCLA and UCSF. Some barriers to uptake identified were as follows: (1) interns were accustomed to import labs and studies into their note to use as their rounding report, and (2) the intervention took place late in the year when interns had developed a functional writing system that they were reluctant to change. The University of Iowa did not show significant improvement in their note quality despite a relatively high template uptake. Both of these outcomes raise the possibility that in addition to the template, there were other factors at play. Perhaps because UCSF and UCLA created the best practice guidelines and template, it was a better fit for their culture and they had more institutional buy-in. Or because the educational lectures were similar, but not standardized across institutions, some lectures may have been more effective than others. However, when evaluating the postintervention notes at UCSD and Iowa, templated notes were found to be much more likely to score higher on the PDQI-9 than nontemplated notes, which serves as evidence of the efficacy of the note template.

Some of the strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size spanning 4 institutions and the use of 3 different assessment tools for grading progress note quality (general impression score, PDQI-9, and competency note questionnaire). An additional strength is our unique finding suggesting that note writing may be more efficient by removing, rather than adding, “efficiency functions.” There were several limitations of this study. Pre- and postintervention notes were examined at different points in the same academic year, thus certain domains may have improved as interns progressed in clinical skill and comfort with documentation, independent of our intervention.21 However, our analysis of postintervention notes across the same time period revealed that use of the template was strongly associated with higher quality, shorter notes and earlier completion time arguing that the effect seen was not merely intern experience. The poor interrater reliability is also a limitation. Although the PDQI-9 was previously validated, future use of the grading tool may require more rater training for calibration or more objective wording.23 The study was not blinded, and thus, bias may have falsely elevated postintervention scores; however, we attempted to minimize bias by incorporating a more objective yes/no competency questionnaire and by having each note scored by 3 graders. Other studies have attempted to address this form of bias by printing out notes and blinding the graders. This design, however, isolates the note from all other data in the medical record, making it difficult to assess domains such as accuracy and completeness. Our inclusion of objective outcomes such as note length and time of note completion help to mitigate some of the bias.

Future research can expand on the results of this study by introducing similar progress note interventions at other institutions and/or in nonacademic environments to validate the results and expand generalizability. Longer term follow-up would be useful to determine if these effects are transient or long lasting. Similarly, it would be interesting to determine if such results are sustained even after new interns start suggesting that institutional culture can be changed. Investigators could focus on similar projects to improve other notes that are particularly at a high risk for propagating false information, such as the History and Physical or Discharge Summary. Future research should also focus on outcomes data, including whether a more efficient note can allow housestaff to spend more time with patients, decrease patient length of stay, reduce clinical errors, and improve educational time for trainees. Lastly, we should determine if interventions such as this can mitigate the widespread frustrations with electronic documentation that are associated with physician and provider burnout.15,24 One would hope that the technology could be harnessed to improve provider productivity and be effectively integrated into comprehensive patient care.

Our research makes progress toward recommendations made by the American College of Physicians “to improve accuracy of information recorded and the value of information,” and develop automated tools that “enhance documentation quality without facilitating improper behaviors.”19 Institutions should consider developing internal best practices for clinical documentation and building structured note templates.19 Our research would suggest that, combined with a small educational intervention, such templates can make progress notes more accurate and succinct, make note writing more efficient, and be harnessed to improve quality metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Pfeffer, MD, and Sitaram Vangala, MS, for their contributions to and support of this research study and manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has led to significant progress in the modernization of healthcare delivery. Ease of access has improved clinical efficiency, and digital data have allowed for point-of-care decision support tools ranging from predicting the 30-day risk of readmission to providing up-to-date guidelines for the care of various diseases.1,2 Documentation tools such as copy-forward and autopopulation increase the speed of documentation, and typed notes improve legibility and ease of note transmission.3,4

However, all of these benefits come with a potential for harm, particularly with respect to accurate and concise documentation. Many experts have described the perpetuation of false information leading to errors, copying-forward of inconsistent and outdated information, and the phenomenon of “note bloat” — physician notes that contain multiple pages of nonessential information, often leaving key aspects buried or lost.5-7 Providers seem to recognize the hazards of copy-and-paste functionality yet persist in utilizing it. In 1 survey, more than 70% of attendings and residents felt that copy and paste led to inaccurate and outdated information, yet 80% stated they would still use it.8

There is little evidence to guide institutions on ways to improve EHR documentation practices. Recent studies have shown that operative note templates improved documentation and decreased the number of missing components.9,10 In the nonoperative setting, 1 small pilot study of pediatric interns demonstrated that a bundled intervention composed of a note template and classroom teaching resulted in improvement in overall note quality and a decrease in “note clutter.”11 In a larger study of pediatric residents, a standardized and simplified note template resulted in a shorter note, although notes were completed later in the day.12 The present study seeks to build upon these efforts by investigating the effect of didactic teaching and an electronic progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness across 4 academic internal medicine residency programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective quality improvement study took place across 4 academic institutions: University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of California San Diego (UCSD), and University of Iowa, all of which use Epic EHR (Epic Corp., Madison, WI). The intervention combined brief educational conferences directed at housestaff and attendings with the implementation of an electronic progress note template. Guided by resident input, a note-writing task force at UCSF and UCLA developed a set of best practice guidelines and an aligned note template for progress notes (supplementary Appendix 1). UCSD and the University of Iowa adopted them at their respective institutions. The template’s design minimized autopopulation while encouraging providers to enter relevant data via free text fields (eg, physical exam), prompts (eg, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…”), and drop-down menus (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] prophylaxis: enoxaparin, heparin subcutaneously, etc; supplementary Appendix 2). Additionally, an inpatient checklist was included at the end of the note to serve as a reminder for key inpatient concerns and quality measures, such as Foley catheter days, discharge planning, and code status. Lectures that focused on issues with documentation in the EHR, the best practice guidelines, and a review of the note template with instructions on how to access it were presented to the housestaff. Each institution tailored the lecture to suit their culture. Housestaff were encouraged but not required to use the note template.

Selection and Grading of Progress Notes

Progress notes were eligible for the study if they were written by an intern on an internal medicine teaching service, from a patient with a hospitalization length of at least 3 days with a progress note selected from hospital day 2 or 3, and written while the patient was on the general medicine wards. The preintervention notes were authored from September 2013 to December 2013 and the postintervention notes from April 2014 to June 2014. One note was selected per patient and no more than 3 notes were selected per intern. Each institution selected the first 50 notes chronologically that met these criteria for both the preintervention and the postintervention periods, for a total of 400 notes. The note-grading tool consisted of the following 3 sections to analyze note quality: (1) a general impression of the note (eg, below average, average, above average); (2) the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9) that evaluates notes on 9 domains (up to date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely); and (3) a note competency questionnaire based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency note checklist that asked yes or no questions about best practice elements (eg, is there a relevant and focused physical exam).12

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07

DISCUSSION

A bundled intervention consisting of educational lectures and a best practice progress note template significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier completion of inpatient progress notes. These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated that a bundled note template intervention improved total note score and reduced note clutter.11 We saw a broad improvement in progress notes across all 9 domains of the PDQI-9, which corresponded with an improved general impression score. We also found statistically significant improvements in 7 of the 13 categories of the competency questionnaire.

Arguably the greatest impact of the intervention was shortening the documentation of labs and studies. Autopopulation can lead to the appearance of a comprehensive note; however, key data are often lost in a sea of numbers and imaging reports.6,14 Using simple prompts followed by free text such as, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…” reduced autopopulation and reminded housestaff to identify only the key information that affected patient care for that day, resulting in a more streamlined, clear, and high-yield note.

The time spent documenting care is an important consideration for physician workflow and for uptake of any note intervention.14-18 One study from 2016 revealed that internal medicine housestaff spend more than half of an average shift using the computer, with 52% of that time spent on documentation.17 Although functions such as autopopulation and copy-forward were created as efficiency tools, we hypothesize that they may actually prolong note writing time by leading to disorganized, distended notes that are difficult to use the following day. There was concern that limiting these “efficiency functions” might discourage housestaff from using the progress note template. It was encouraging to find that postintervention notes were signed 1.3 hours earlier in the day. This study did not measure the impact of shorter notes and earlier completion time, but in theory, this could allow interns to spend more time in direct patient care and to be at lower risk of duty hour violations.19 Furthermore, while the clinical impact of this is unknown, it is possible that timely note completion may improve patient care by making notes available earlier for consultants and other members of the care team.

We found that adding an “inpatient checklist” to the progress note template facilitated a review of key inpatient concerns and quality measures. Although we did not specifically compare before-and-after documentation of all of the components of the checklist, there appeared to be improvement in the domains measured. Notably, there was a 31% increase (P < .001) in the percentage of notes documenting the “discharge plan, goals of hospitalization, or estimated length of stay.” In the surgical literature, studies have demonstrated that incorporating checklists improves patient safety, the delivery of care, and potentially shortens the length of stay.20-22 Future studies should explore the impact of adding a checklist to the daily progress note, as there may be potential to improve both process and outcome measures.

Institution-specific data provided insightful results. UCSD encountered low template use among their interns; however, they still had evidence of improvement in note quality, though not at the same level of UCLA and UCSF. Some barriers to uptake identified were as follows: (1) interns were accustomed to import labs and studies into their note to use as their rounding report, and (2) the intervention took place late in the year when interns had developed a functional writing system that they were reluctant to change. The University of Iowa did not show significant improvement in their note quality despite a relatively high template uptake. Both of these outcomes raise the possibility that in addition to the template, there were other factors at play. Perhaps because UCSF and UCLA created the best practice guidelines and template, it was a better fit for their culture and they had more institutional buy-in. Or because the educational lectures were similar, but not standardized across institutions, some lectures may have been more effective than others. However, when evaluating the postintervention notes at UCSD and Iowa, templated notes were found to be much more likely to score higher on the PDQI-9 than nontemplated notes, which serves as evidence of the efficacy of the note template.

Some of the strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size spanning 4 institutions and the use of 3 different assessment tools for grading progress note quality (general impression score, PDQI-9, and competency note questionnaire). An additional strength is our unique finding suggesting that note writing may be more efficient by removing, rather than adding, “efficiency functions.” There were several limitations of this study. Pre- and postintervention notes were examined at different points in the same academic year, thus certain domains may have improved as interns progressed in clinical skill and comfort with documentation, independent of our intervention.21 However, our analysis of postintervention notes across the same time period revealed that use of the template was strongly associated with higher quality, shorter notes and earlier completion time arguing that the effect seen was not merely intern experience. The poor interrater reliability is also a limitation. Although the PDQI-9 was previously validated, future use of the grading tool may require more rater training for calibration or more objective wording.23 The study was not blinded, and thus, bias may have falsely elevated postintervention scores; however, we attempted to minimize bias by incorporating a more objective yes/no competency questionnaire and by having each note scored by 3 graders. Other studies have attempted to address this form of bias by printing out notes and blinding the graders. This design, however, isolates the note from all other data in the medical record, making it difficult to assess domains such as accuracy and completeness. Our inclusion of objective outcomes such as note length and time of note completion help to mitigate some of the bias.

Future research can expand on the results of this study by introducing similar progress note interventions at other institutions and/or in nonacademic environments to validate the results and expand generalizability. Longer term follow-up would be useful to determine if these effects are transient or long lasting. Similarly, it would be interesting to determine if such results are sustained even after new interns start suggesting that institutional culture can be changed. Investigators could focus on similar projects to improve other notes that are particularly at a high risk for propagating false information, such as the History and Physical or Discharge Summary. Future research should also focus on outcomes data, including whether a more efficient note can allow housestaff to spend more time with patients, decrease patient length of stay, reduce clinical errors, and improve educational time for trainees. Lastly, we should determine if interventions such as this can mitigate the widespread frustrations with electronic documentation that are associated with physician and provider burnout.15,24 One would hope that the technology could be harnessed to improve provider productivity and be effectively integrated into comprehensive patient care.

Our research makes progress toward recommendations made by the American College of Physicians “to improve accuracy of information recorded and the value of information,” and develop automated tools that “enhance documentation quality without facilitating improper behaviors.”19 Institutions should consider developing internal best practices for clinical documentation and building structured note templates.19 Our research would suggest that, combined with a small educational intervention, such templates can make progress notes more accurate and succinct, make note writing more efficient, and be harnessed to improve quality metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Pfeffer, MD, and Sitaram Vangala, MS, for their contributions to and support of this research study and manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Herzig SJ, Guess JR, Feinbloom DB, et al. Improving appropriateness of acid-suppressive medication use via computerized clinical decision support. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):41-45. PubMed

2. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Predicting all-cause readmissions using electronic health record data from the entire hospitalization: Model development and comparison. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):473-480. PubMed

3. Donati A, Gabbanelli V, Pantanetti S, et al. The impact of a clinical information system in an intensive care unit. J Clin Monit Comput. 2008;22(1):31-36. PubMed

4. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1066-1069. PubMed

5. Hartzband P, Groopman J. Off the record--avoiding the pitfalls of going electronic. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1656-1658. PubMed

6. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. Copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336. PubMed

7. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. John Lennon’s elbow. JAMA. 2012;308(5):463-464. PubMed

8. O’Donnell HC, Kaushal R, Barrón Y, Callahan MA, Adelman RD, Siegler EL. Physicians’ attitudes towards copy and pasting in electronic note writing. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):63-68. PubMed

9. Mahapatra P, Ieong E. Improving Documentation and Communication Using Operative Note Proformas. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u209122.w3712. PubMed

10. Thomson DR, Baldwin MJ, Bellini MI, Silva MA. Improving the quality of operative notes for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Assessing the impact of a standardized operation note proforma. Int J Surg. 2016;27:17-20. PubMed

11. Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):104-107. PubMed

12. Aylor M, Campbell EM, Winter C, Phillipi CA. Resident Notes in an Electronic Health Record: A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Standardized Intervention With Qualitative Analysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;6(3):257-262.

13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. PubMed

14. Chi J, Kugler J, Chu IM, et al. Medical students and the electronic health record: ‘an epic use of time’. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):891-895. PubMed

15. Martin SA, Sinsky CA. The map is not the territory: medical records and 21st century practice. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2053-2056. PubMed

16. Oxentenko AS, Manohar CU, McCoy CP, et al. Internal medicine residents’ computer use in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):529-532. PubMed

17. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How Do Residents Spend Their Shift Time? A Time and Motion Study With a Particular Focus on the Use of Computers. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):827-832. PubMed

18. Chen L, Guo U, Illipparambil LC, et al. Racing Against the Clock: Internal Medicine Residents’ Time Spent On Electronic Health Records. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):39-44. PubMed

19. Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T, Physicians MICotACo. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):301-303. PubMed

20. Treadwell JR, Lucas S, Tsou AY. Surgical checklists: a systematic review of impacts and implementation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):299-318. PubMed

21. Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings--limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:211. PubMed

22. Diaz-Montes TP, Cobb L, Ibeanu OA, Njoku P, Gerardi MA. Introduction of checklists at daily progress notes improves patient care among the gynecological oncology service. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(4):189-193. PubMed

23. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing Electronic Note Quality Using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. PubMed

24. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. PubMed

1. Herzig SJ, Guess JR, Feinbloom DB, et al. Improving appropriateness of acid-suppressive medication use via computerized clinical decision support. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):41-45. PubMed

2. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Predicting all-cause readmissions using electronic health record data from the entire hospitalization: Model development and comparison. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):473-480. PubMed

3. Donati A, Gabbanelli V, Pantanetti S, et al. The impact of a clinical information system in an intensive care unit. J Clin Monit Comput. 2008;22(1):31-36. PubMed

4. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1066-1069. PubMed

5. Hartzband P, Groopman J. Off the record--avoiding the pitfalls of going electronic. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1656-1658. PubMed

6. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. Copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336. PubMed

7. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. John Lennon’s elbow. JAMA. 2012;308(5):463-464. PubMed

8. O’Donnell HC, Kaushal R, Barrón Y, Callahan MA, Adelman RD, Siegler EL. Physicians’ attitudes towards copy and pasting in electronic note writing. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):63-68. PubMed

9. Mahapatra P, Ieong E. Improving Documentation and Communication Using Operative Note Proformas. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u209122.w3712. PubMed

10. Thomson DR, Baldwin MJ, Bellini MI, Silva MA. Improving the quality of operative notes for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Assessing the impact of a standardized operation note proforma. Int J Surg. 2016;27:17-20. PubMed

11. Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):104-107. PubMed

12. Aylor M, Campbell EM, Winter C, Phillipi CA. Resident Notes in an Electronic Health Record: A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Standardized Intervention With Qualitative Analysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;6(3):257-262.

13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. PubMed

14. Chi J, Kugler J, Chu IM, et al. Medical students and the electronic health record: ‘an epic use of time’. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):891-895. PubMed

15. Martin SA, Sinsky CA. The map is not the territory: medical records and 21st century practice. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2053-2056. PubMed

16. Oxentenko AS, Manohar CU, McCoy CP, et al. Internal medicine residents’ computer use in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):529-532. PubMed

17. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How Do Residents Spend Their Shift Time? A Time and Motion Study With a Particular Focus on the Use of Computers. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):827-832. PubMed

18. Chen L, Guo U, Illipparambil LC, et al. Racing Against the Clock: Internal Medicine Residents’ Time Spent On Electronic Health Records. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):39-44. PubMed

19. Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T, Physicians MICotACo. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):301-303. PubMed

20. Treadwell JR, Lucas S, Tsou AY. Surgical checklists: a systematic review of impacts and implementation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):299-318. PubMed

21. Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings--limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:211. PubMed

22. Diaz-Montes TP, Cobb L, Ibeanu OA, Njoku P, Gerardi MA. Introduction of checklists at daily progress notes improves patient care among the gynecological oncology service. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(4):189-193. PubMed

23. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing Electronic Note Quality Using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. PubMed

24. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Evaluation of Medical Inpatients Who Are Admitted on Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

Hospitalists face complex questions about how to evaluate and treat the large number of individuals who are admitted on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT, defined as lasting 3 months or longer) for chronic noncancer pain. A recent study at one Veterans Affairs hospital, found 26% of medical inpatients were on LTOT.1 Over the last 2 decades, use of LTOT has risen substantially in the United States, including among middle-aged and older adults.2 Concurrently, inpatient hospitalizations related to the overuse of prescription opioids, including overdose, dependence, abuse, and adverse drug events, have increased by 153%.3 Individuals on LTOT can also be hospitalized for exacerbations of the opioid-treated chronic pain condition or unrelated conditions. In addition to affecting rates of hospitalization, use of LTOT is associated with higher rates of in-hospital adverse events, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates.1,4,5

Physicians find managing chronic pain to be stressful, are often concerned about misuse and addiction, and believe their training in opioid prescribing is inadequate.6 Hospitalists report confidence in assessing and prescribing opioids for acute pain but limited success and satisfaction with treating exacerbations of chronic pain.7 Although half of all hospitalized patients receive opioids,5 little information is available to guide the care of hospitalized medical patients on LTOT for chronic noncancer pain.8,9

Our multispecialty team sought to synthesize guideline recommendations and primary literature relevant to the assessment of medical inpatients on LTOT to assist practitioners balance effective pain treatment and opioid risk reduction. This article addresses obtaining a comprehensive pain history, identifying misuse and opioid use disorders, assessing the risk of overdose and adverse drug events, gauging the risk of withdrawal, and based on such findings, appraise indications for opioid therapy. Other authors have recently published narrative reviews on the management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence and the inpatient management of opioid use disorder.10,11

METHODS

To identify primary literature, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economic Evaluations Database, key meeting abstracts, and hand searches. To identify guidelines, we searched PubMed, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, specialty societies’ websites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Canadian Medical Association, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Search terms related to opioids and chronic pain, which was last updated in October 2016.12

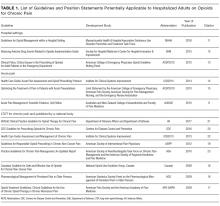

We selected English-language documents on opioids and chronic pain among adults, excluding pain in the setting of procedures, labor and delivery, life-limiting illness, or specific conditions. For primary literature, we considered intervention studies of any design that addressed pain management among hospitalized medical patients. We included guidelines and specialty society position statements published after January 1, 2009, that addressed pain in the hospital setting, acute pain in any setting, or chronic pain in the outpatient setting if published by a national body. Due to the paucity of documents specific to inpatient care, we used a narrative review format to synthesize information. Dual reviewers extracted guideline recommendations potentially relevant to medical inpatients on LTOT. We also summarize relevant assessment instruments, emphasizing very brief screening instruments, which may be more likely to be used by busy hospitalists.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Obtaining a Comprehensive Pain History

Hospitalists newly evaluating patients on LTOT often face a dual challenge: deciding if the patient has an immediate indication for additional opioids and if the current long-term opioid regimen should be altered or discontinued. In general, opioids are an accepted short-term treatment for moderate to severe acute pain but their role in chronic noncancer pain is controversial. Newly released guidelines by the CDC recommend initiating LTOT as a last resort, and the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense guidelines recommend against initiation of LTOT.22,23

A key first step, therefore, is distinguishing between acute and chronic pain. Among patients on LTOT, pain can represent a new acute pain condition, an exacerbation of chronic pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or opioid withdrawal. Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in relation to such damage.26 In contrast, chronic pain is a complex response that may not be related to actual or ongoing tissue damage, and is influenced by physiological, contextual, and psychological factors. Two acute pain guidelines and 1 chronic pain guideline recommend distinguishing acute and chronic pain,9,16,21 3 chronic pain guidelines reinforce the importance of obtaining a pain history (including timing, intensity, frequency, onset, etc),20,22,23 and 6 guidelines recommend ascertaining a history of prior pain-related treatments.9,13,14,16,20,22 Inquiring how the current pain compares with symptoms “on a good day,” what activities the patient can usually perform, and what the patient does outside the hospital to cope with pain can serve as entry into this conversation.

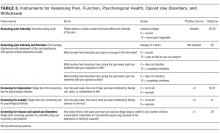

In addition to function, 5 guidelines, including 2 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend obtaining a detailed psychosocial history to identify life stressors and gain insight into the patient’s coping skills.14,16,19,20,22 Psychiatric symptoms can intensify the experience of pain or hamper coping ability. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia frequently coexist in patients with chronic pain.31 As such, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and 3 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for mental health issues including anxiety and depression.13,14,16,20,22,23 Several depression screening instruments have been validated among inpatients,32 and there are validated single-item, self-administered instruments for both depression and anxiety (Table 3).32,33

Although obtaining a comprehensive history before making treatment decisions is ideal, some patients present in extremis. In emergency departments, some guidelines endorse prompt administration of analgesics based on patient self-report, prior to establishing a diagnosis.17 Given concerns about the growing prevalence of opioid use disorders, several states now recommend emergency medicine prescribers screen for misuse before giving opioids and avoid parenteral opioids for acute exacerbations of chronic pain.34 Treatments received in emergency departments set patients’ expectations for the care they receive during hospitalization, and hospitalists may find it necessary to explain therapies appropriate for urgent management are not intended to be sustained.

Identifying Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and opioid use disorders have more than doubled over the last decade.35 Five guidelines, including 3 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend screening for opioid misuse.13,14,16,19,23 Many states mandate practitioners assess patients for substance use disorders before prescribing controlled substances.36 Instruments to identify aberrant and risky use include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure,37 Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire,38 Addiction Behaviors Checklist,39 Screening Tool for Abuse,40 and the Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Question (Table 3).41 However, the evidence for these and other tools is limited and absent for the inpatient setting.21,42

In addition to obtaining a history from the patient, 4 guidelines specific to hospital settings/acute pain and 4 chronic pain guidelines recommend practitioners access prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).13-16,19,21-24 PDMPs exist in all states except Missouri, and about half of states mandate practitioners check the PDMP database in certain circumstances.36 Studies examining the effects of PDMPs on prescribing are limited, but checking these databases can uncover concerning patterns including overlapping prescriptions or multiple prescribers.43 PDMPs can also confirm reported medication doses, for which patient report may be less reliable.

Two hospital/acute pain guidelines and 5 chronic pain guidelines also recommend urine drug testing, although differing on when and whom to test, with some favoring universal screening.11,20,23 Screening hospitalized patients may reveal substances not reported by patients, but medications administered in emergency departments can confound results. Furthermore, the commonly used immunoassay does not distinguish heroin from prescription opioids, nor detect hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, or certain benzodiazepines. Chromatography/mass spectrometry assays can but are often not available from hospital laboratories. The differential for unexpected results includes substance use, self treatment of uncontrolled pain, diversion, or laboratory error.20

If concerning opioid use is identified, 3 hospital setting/acute pain specific guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend sharing concerns with patients and assessing for a substance use disorder.9,13,16,22 Determining whether patients have an opioid use disorder that meets the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition44 can be challenging. Patients may minimize or deny symptoms or fear that the stigma of an opioid use disorder will lead to dismissive or subpar care. Additionally, substance use disorders are subject to federal confidentiality regulations, which can hamper acquisition of information from providers.45 Thus, hospitalists may find specialty consultation helpful to confirm the diagnosis.

Assessing the Risk of Overdose and Adverse Drug Events

Oversedation, respiratory depression, and death can result from iatrogenic or self-administered opioid overdose in the hospital.5 Patient factors that increase this risk among outpatients include a prior history of overdose, preexisting substance use disorders, cognitive impairment, mood and personality disorders, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, and recent abstinence from opioids.12 Medication factors include concomitant use of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, including alcohol; recent initiation of long-acting opioids; use of fentanyl patches, immediate-release fentanyl, or methadone; rapid titration; switching opioids without adequate dose reduction; pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions; and, importantly, higher doses.12,22 Two guidelines specific to acute pain and hospital settings and 5 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for use of benzodiazepines among patients on LTOT.13,14,16,18-20,22,21

The CDC guideline recommends careful assessment when doses exceed 50 mg of morphine equivalents per day and avoiding doses above 90 mg per day due to the heightened risk of overdose.22 In the hospital, 23% of patients receive doses at or above 100 mg of morphine equivalents per day,5 and concurrent use of central nervous system depressants is common. Changes in kidney and liver function during acute illness may impact opioid metabolism and contribute to overdose.

In addition to overdose, opioids are leading causes of adverse drug events during hospitalization.46 Most studies have focused on surgical patients reporting common opioid-related events as nausea/vomiting, pruritus, rash, mental status changes, respiratory depression, ileus, and urinary retention.47 Hospitalized patients may also exhibit chronic adverse effects due to LTOT. At least one-third of patients on LTOT eventually stop because of adverse effects, such as endocrinopathies, sleep disordered breathing, constipation, fractures, falls, and mental status changes.48 Patients may lack awareness that their symptoms are attributable to opioids and are willing to reduce their opioid use once informed, especially when alternatives are offered to alleviate pain.

Gauging the Risk of Withdrawal

Sudden discontinuation of LTOT by patients, practitioners, or intercurrent events can have unanticipated and undesirable consequences. Withdrawal is not only distressing for patients; it can be dangerous because patients may resort to illicit use, diversion of opioids, or masking opioid withdrawal with other substances such as alcohol. The anxiety and distress associated with withdrawal, or anticipatory fear about withdrawal, can undermine therapeutic alliance and interfere with processes of care. Reviewed guidelines did not offer recommendations regarding withdrawal risk or specific strategies for avoidance. There is no specific prior dose threshold or degree of reduction in opioids that puts patients at risk for withdrawal, in part due to patients’ beliefs, expectations, and differences in response to opioid formulations. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal have been compared to a severe case of influenza, including stomach cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, tremor and muscle twitching, sweating, restlessness, yawning, tachycardia, anxiety and irritability, bone and joint aches, runny nose, tearing, and piloerection.49 The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)49 and the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment51 are clinician-administered tools to assess opioid withdrawal similar to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised,52 to monitor for withdrawal in the inpatient setting.

Synthesizing and Appraising the Indications for Opioid Therapy