User login

Recommendations for Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Recommendations for Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic scarring inflammatory skin condition of the follicular epithelium that impacts 1% to 4% of the general population (eFigure).1-3 This statistic likely is an underrepresentation of the affected population due to missed and delayed diagnoses.1 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been identified as having one of the strongest negative impacts on patients’ lives based on studied skin diseases.4 Its recurrent nature can negatively impact both the patient’s physical and mental state.3 Due to the debilitating effects of HS, we aimed to create updated recommendations for empiric antibotics based on affected anatomic locations in an effort to improve patient quality of life.

Methods

An institutional review board–approved retrospective medical chart review of 485 patients diagnosed with HS and evaluated at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston from January 2006 to December 2021 was conducted. Males and females of all ages (including pregnant and pediatric patients) were included. Only patients for whom anatomic locations of HS lesions or culture sites were not documented were excluded from the analysis. Locations of cultures were categorized into 5 groups: axilla; groin; buttocks; inframammary; and multiple sites of involvement, which included any combination of 2 or more sites. Types of bacteria collected from cultures and recorded included Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and other Gram-negative species. Sensitivity profiles also were analyzed for the most commonly cultured bacteria to create recommendations on antibiotic use based on the anatomic location of the lesions. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis.

Results

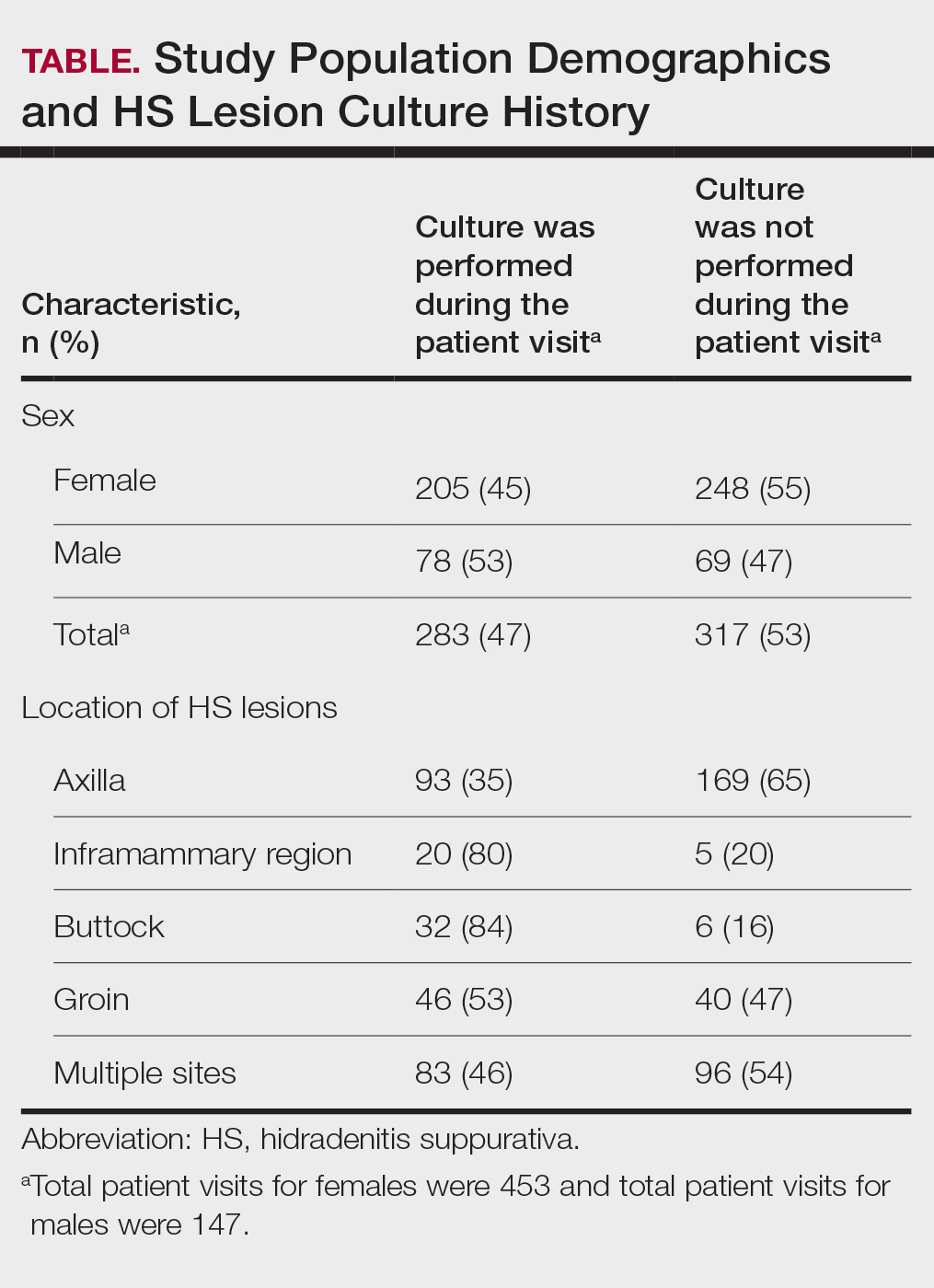

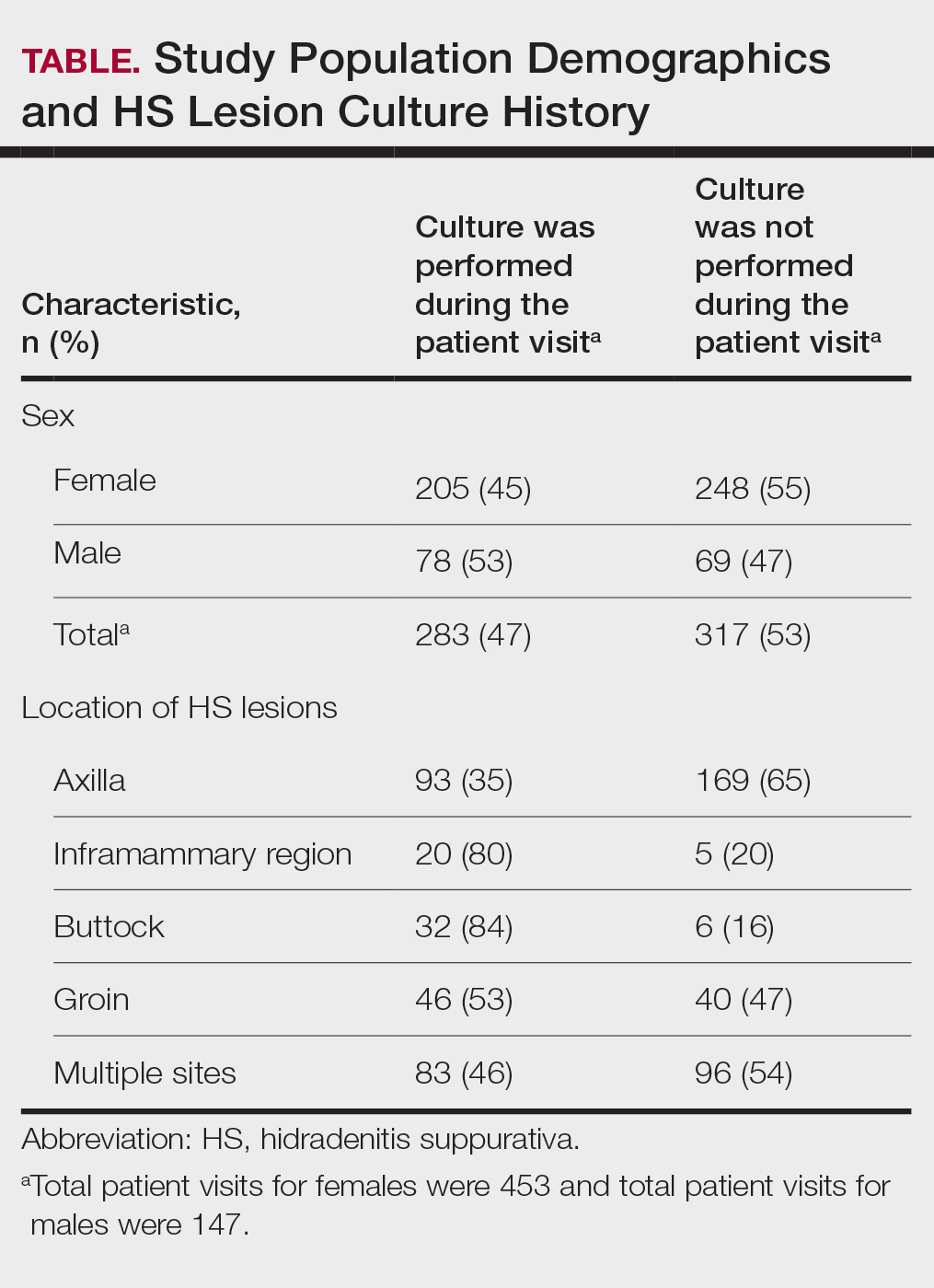

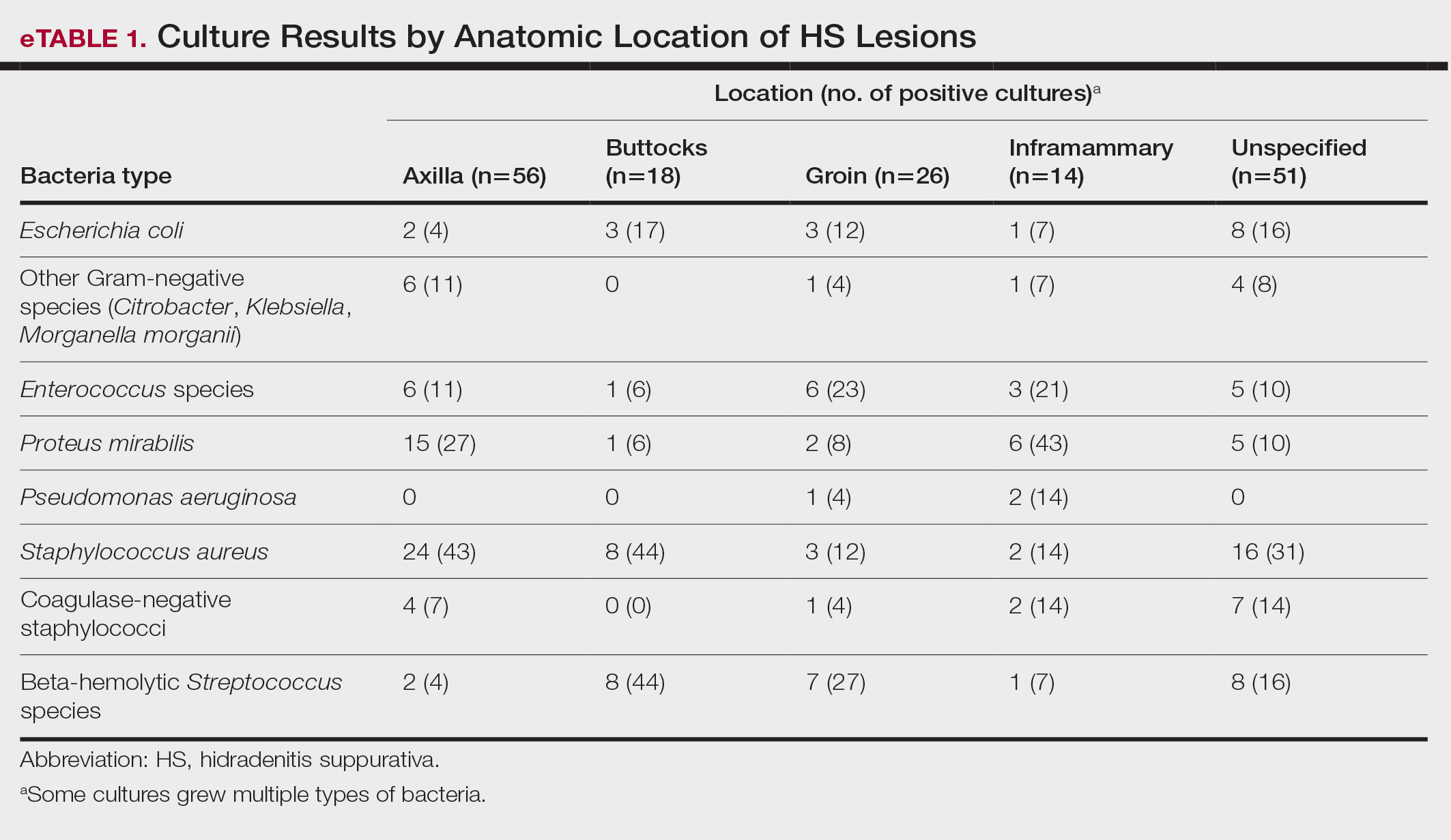

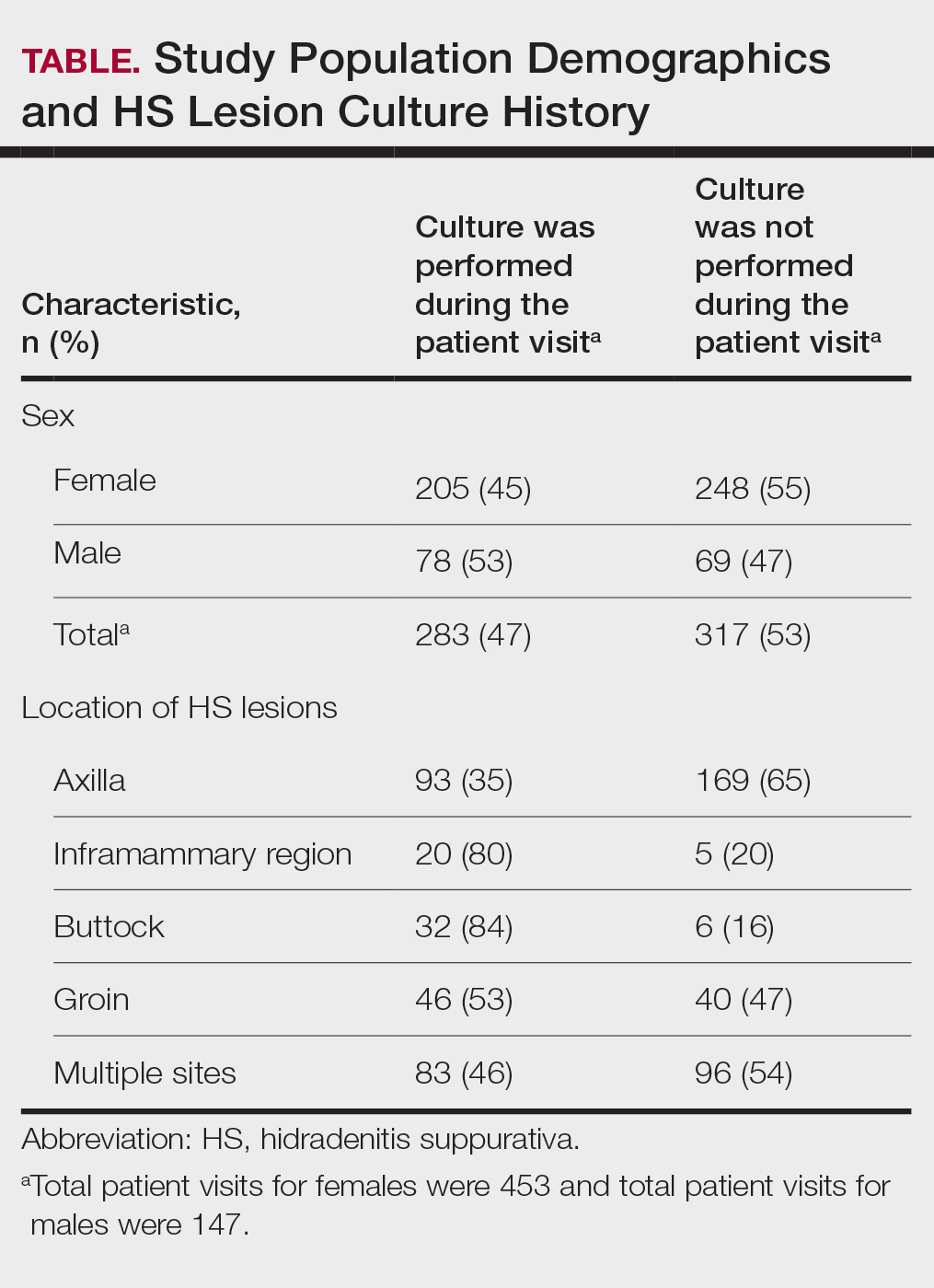

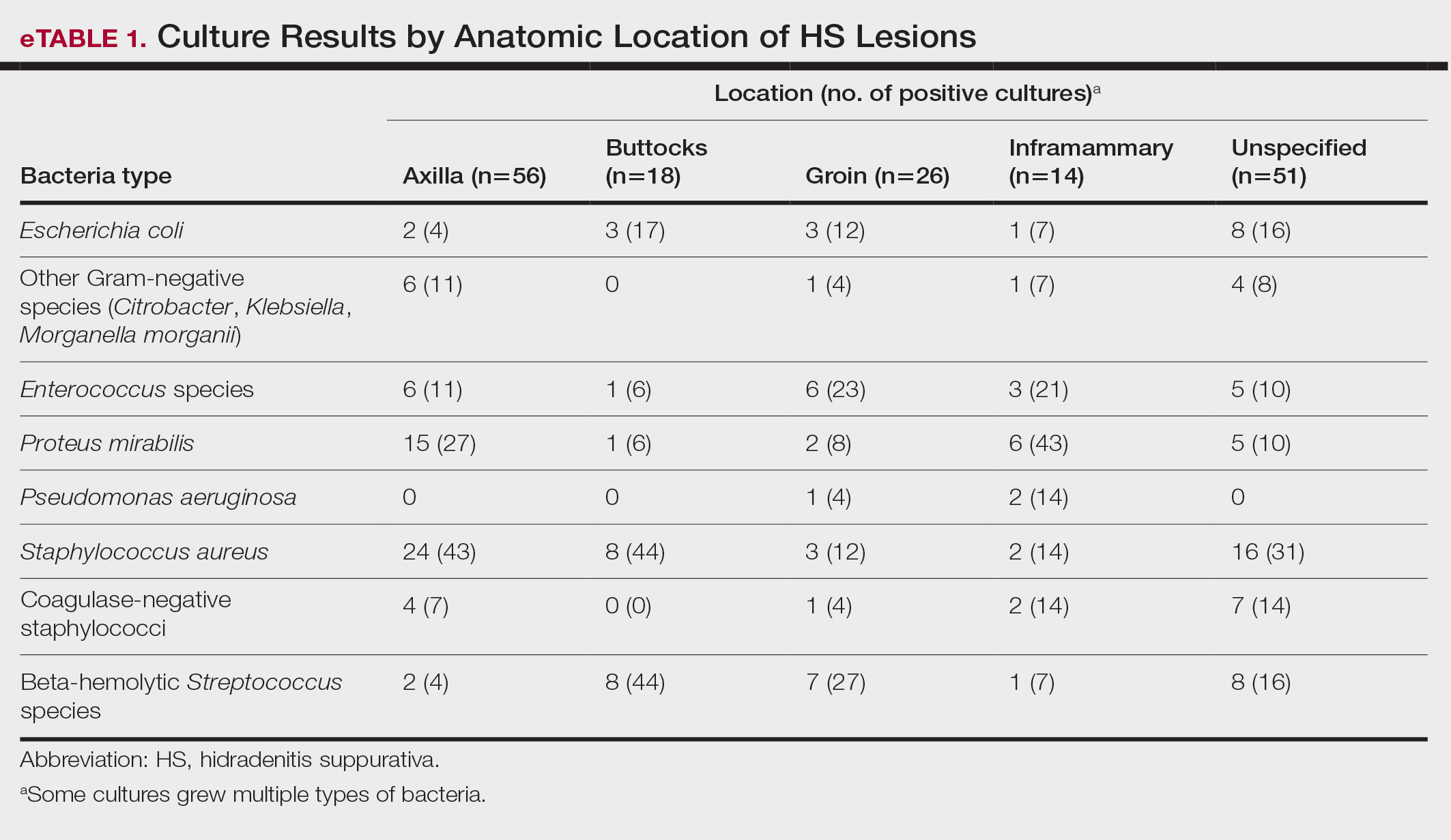

The analysis included 485 patients comprising 600 visits. Seventy-five percent (363/485) of the study population was female. The axilla was the most common anatomic location for HS lesions followed by multiple sites of involvement. In total, 283 cultures were performed; males were 1.1 times more likely than females to be cultured. While cultures were most frequently obtained in patients with axillary lesions only (93/262 [35%]) or from multiple sites of involvement (83/179 [46%]) as this was the most common presentation of HS in our patient population, cultures were more likely to be obtained when patients presented with only buttock (32/38 [84%]) and inframammary (20/25 [80%]) lesions (Table).

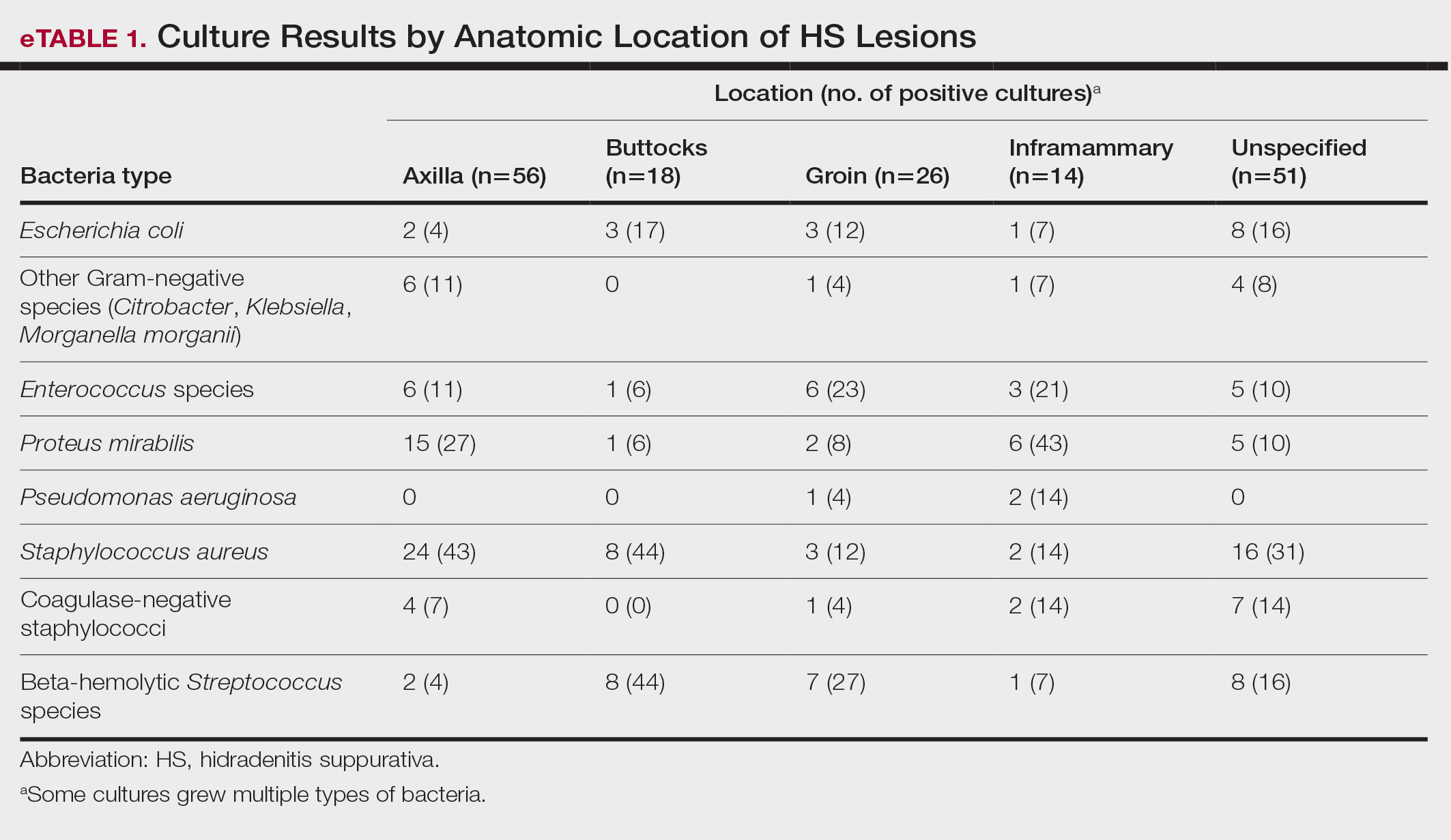

Staphylococcus aureus was the most commonly cultured bacteria in general (53/283 [19%]) as well as for HS located the axilla (24/56 [43%]) and in multiple sites (16/51 [31%]). Proteus mirabilis (29/283 [10%]) was the second most commonly cultured bacteria overall and was cultured most often in the axilla (15/56 [27%]) and inframammary region (6/14 [43%]). These were followed by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species (26/283 [9%]) and Enterococcus species (21/283 [7%]), which was second to P mirabilis as the most commonly cultured bacteria in the inframammary region (6/14 [43%])(eTable 1).

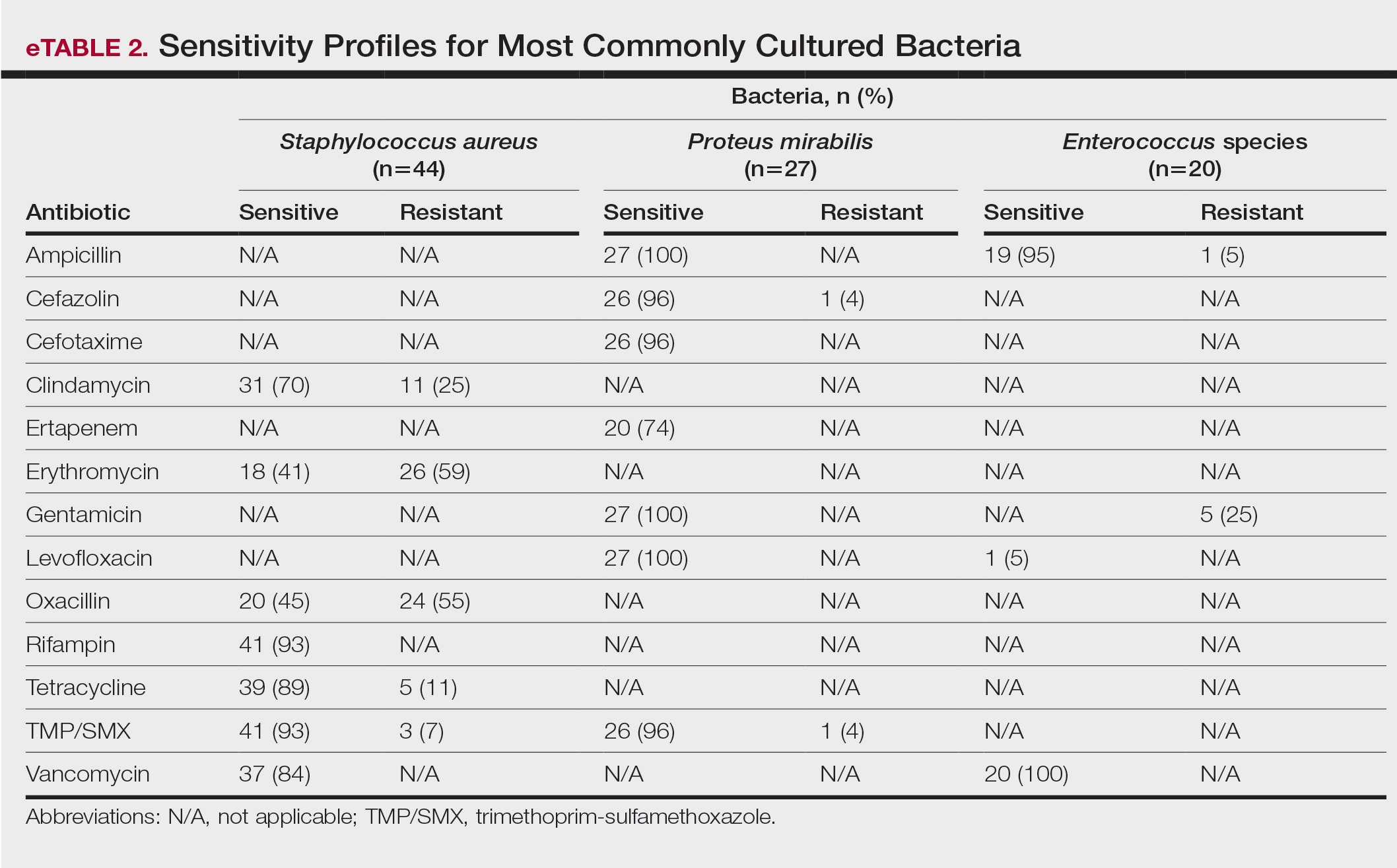

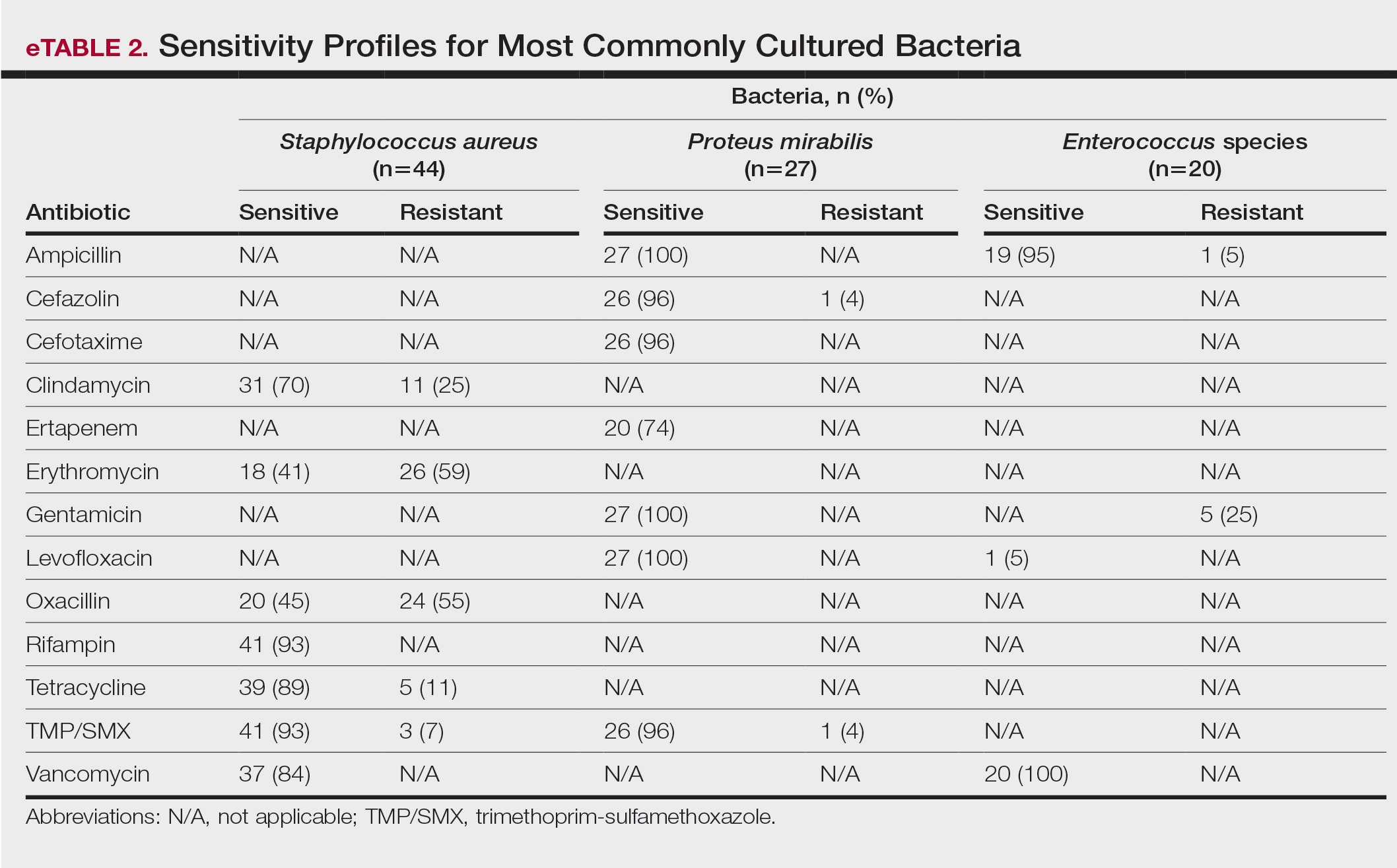

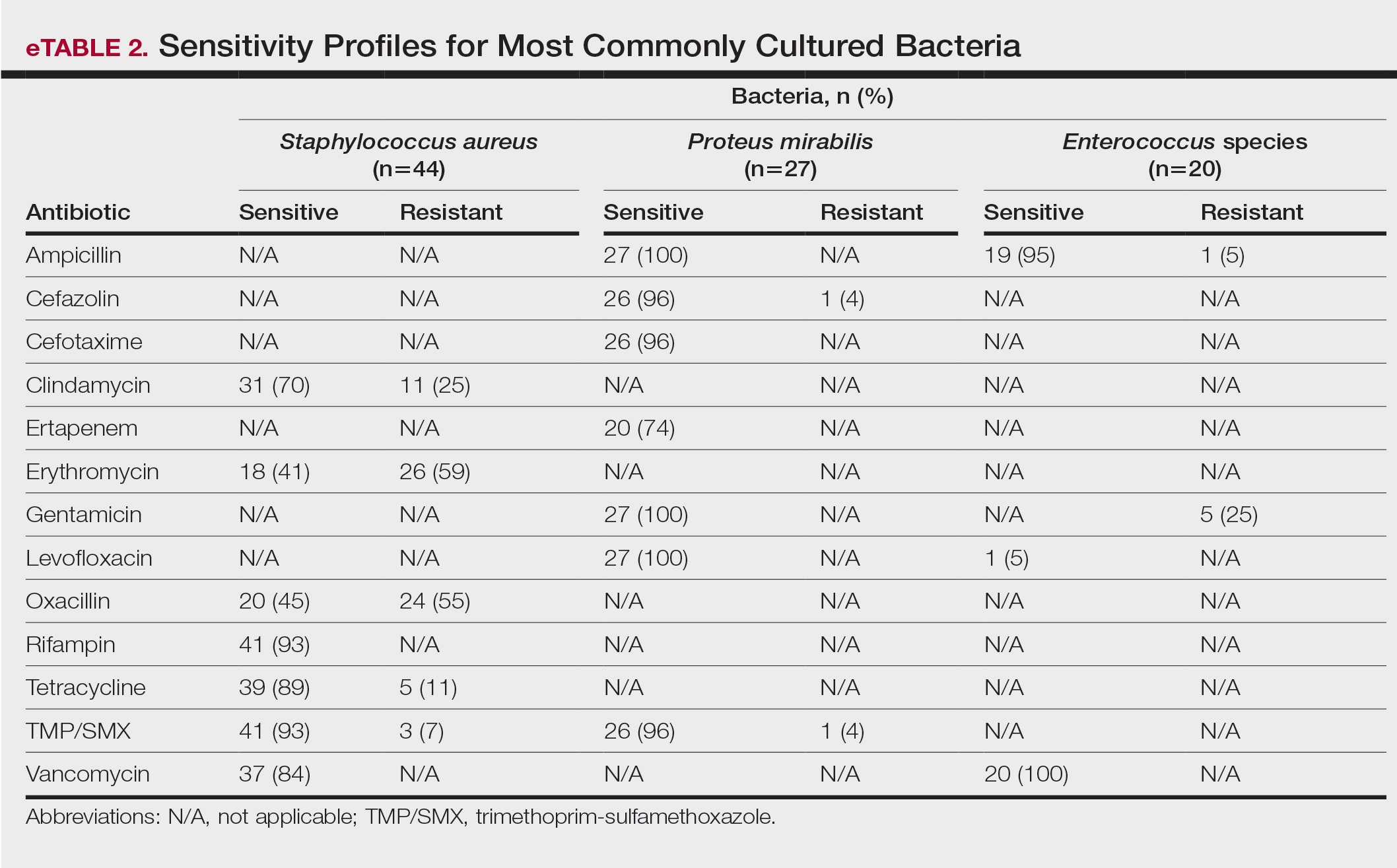

eTable 2 shows the sensitivity profiles for the most commonly cultured bacteria: S aureus, P mirabilis, and Enterococcus species. Staphylococcus aureus located in the axilla, buttocks, and groin was most sensitive to rifampin (41/44 [93%]), TMP/SMX (41/44 [93%]), and tetracycline (39/44 [89%]) and most resistant to erythromycin (26/44 [59%]) and oxacillin (24/44 [55%]). Proteus mirabilis in the inframammary region was most sensitive to ampicillin (27/27 [100%]), gentamicin (27/27 [100%]), levofloxacin (27/27 [100%]), and TMP/SMX (26/27 [96%]). Enterococcus species were most sensitive to vancomycin (20/20 [100%]) and ampicillin (19/20 [95%]) and most resistant to gentamicin (5/20 [25%]).

Comment

To treat HS, it is important to understand the cause of the condition. Although the pathogenesis of HS has many unknowns, bacterial colonization and biofilms are thought to play a role. Lipopolysaccharides found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are pathogen-associated molecular patterns that present to the toll-like receptors of the human immune system. Once the toll-like receptors recognize the pathogen-associated molecular patterns, macrophages and keratinocytes are activated and release proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Persistent presentation of bacteria to the immune system increases immune-cell recruitment and worsens chronic inflammation in patients with HS. Evidence has revealed that bacteria initiate and sustain the inflammation seen in patients with HS; therefore, reducing the amount of bacteria could alleviate some of the symptoms of HS.5 It is important to continue learning about the pathophysiology of this disease as well as formulating tailored treatments to minimize patient discomfort and improve quality of life.

Based on the findings of the current study and the safety profile of the medication, tetracyclines may be considered for first-line empiric therapy in patients with HS involving the axilla only, buttocks only, or multiple sites. For additional coverage of P mirabilis in the axilla or inframammary region, TMP/SMX monotherapy or tetracycline plus ampicillin may be considered. For inframammary lesions only, empiric treatment with ampicillin or TMP/ SMX is recommended. For HS lesions in the groin area, coverage of Enterococcus species with ampicillin should be considered. Patients with multiple sites of involvement that include the inframammary or groin regions similarly should receive empiric antibiotics that cover both S aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, such as TMP/SMX or tetracycline and ampicillin, respectively; if the multiple sites do not include the inframammary or groin regions, Gram-negative coverage may not be indicated. Based on our findings, standardization of treatment for patients with HS can allow for earlier and potentially more effective treatment.

In a similar study conducted in 2016, bacteria species were isolated from the axilla, groin, and gluteus/perineum in patients with HS.5 In that study, the most prominent bacteria in the axilla was CoNS; in the groin, P mirabilis and E coli; and in the gluteus/perineum, E coli and CoNS. These results differed from ours, which found S aureus as the abundant bacteria in these areas. In the 2016 study, the highest rates of resistance were found for penicillin G, erythromycin, clindamycin, and ampicillin.5 In contrast, the current study found high sensitivities for clindamycin and ampicillin, but our results support the finding of high resistance for erythromycin. These differences could be accounted for by the lower sample size of patients in the 2016 study: 68 patients were analyzed for sensitivity results, and 171 patients were analyzed for frequency of bacterial species in patients with HS.5

Our study is limited by its relatively small sample size. Additionally, all patients were seen at 1 of 2 clinic sites, located in League City and Galveston, Texas, and the data from this geographic area may not be applicable to patients seen in different climates.

Conclusion

Outcomes for patients with HS improve with early intervention; however, HS treatment may be delayed by selection of ineffective antibiotic therapy. Our study provides clinicians with recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment based on anatomic location of HS lesions and culture sensitivity profiles. Utilizing tailored antibiotic therapy on initial clinical evaluation may increase early disease control and improve morbidity and disease outcomes, thereby increasing patient quality of life.

- Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-563.

- Yazdanyar S, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of cause and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:118-123.

- Hessam S, Sand M, Georgas D, et al. Microbial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria found in inflammatory hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016; 29:161-167.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic scarring inflammatory skin condition of the follicular epithelium that impacts 1% to 4% of the general population (eFigure).1-3 This statistic likely is an underrepresentation of the affected population due to missed and delayed diagnoses.1 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been identified as having one of the strongest negative impacts on patients’ lives based on studied skin diseases.4 Its recurrent nature can negatively impact both the patient’s physical and mental state.3 Due to the debilitating effects of HS, we aimed to create updated recommendations for empiric antibotics based on affected anatomic locations in an effort to improve patient quality of life.

Methods

An institutional review board–approved retrospective medical chart review of 485 patients diagnosed with HS and evaluated at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston from January 2006 to December 2021 was conducted. Males and females of all ages (including pregnant and pediatric patients) were included. Only patients for whom anatomic locations of HS lesions or culture sites were not documented were excluded from the analysis. Locations of cultures were categorized into 5 groups: axilla; groin; buttocks; inframammary; and multiple sites of involvement, which included any combination of 2 or more sites. Types of bacteria collected from cultures and recorded included Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and other Gram-negative species. Sensitivity profiles also were analyzed for the most commonly cultured bacteria to create recommendations on antibiotic use based on the anatomic location of the lesions. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis.

Results

The analysis included 485 patients comprising 600 visits. Seventy-five percent (363/485) of the study population was female. The axilla was the most common anatomic location for HS lesions followed by multiple sites of involvement. In total, 283 cultures were performed; males were 1.1 times more likely than females to be cultured. While cultures were most frequently obtained in patients with axillary lesions only (93/262 [35%]) or from multiple sites of involvement (83/179 [46%]) as this was the most common presentation of HS in our patient population, cultures were more likely to be obtained when patients presented with only buttock (32/38 [84%]) and inframammary (20/25 [80%]) lesions (Table).

Staphylococcus aureus was the most commonly cultured bacteria in general (53/283 [19%]) as well as for HS located the axilla (24/56 [43%]) and in multiple sites (16/51 [31%]). Proteus mirabilis (29/283 [10%]) was the second most commonly cultured bacteria overall and was cultured most often in the axilla (15/56 [27%]) and inframammary region (6/14 [43%]). These were followed by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species (26/283 [9%]) and Enterococcus species (21/283 [7%]), which was second to P mirabilis as the most commonly cultured bacteria in the inframammary region (6/14 [43%])(eTable 1).

eTable 2 shows the sensitivity profiles for the most commonly cultured bacteria: S aureus, P mirabilis, and Enterococcus species. Staphylococcus aureus located in the axilla, buttocks, and groin was most sensitive to rifampin (41/44 [93%]), TMP/SMX (41/44 [93%]), and tetracycline (39/44 [89%]) and most resistant to erythromycin (26/44 [59%]) and oxacillin (24/44 [55%]). Proteus mirabilis in the inframammary region was most sensitive to ampicillin (27/27 [100%]), gentamicin (27/27 [100%]), levofloxacin (27/27 [100%]), and TMP/SMX (26/27 [96%]). Enterococcus species were most sensitive to vancomycin (20/20 [100%]) and ampicillin (19/20 [95%]) and most resistant to gentamicin (5/20 [25%]).

Comment

To treat HS, it is important to understand the cause of the condition. Although the pathogenesis of HS has many unknowns, bacterial colonization and biofilms are thought to play a role. Lipopolysaccharides found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are pathogen-associated molecular patterns that present to the toll-like receptors of the human immune system. Once the toll-like receptors recognize the pathogen-associated molecular patterns, macrophages and keratinocytes are activated and release proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Persistent presentation of bacteria to the immune system increases immune-cell recruitment and worsens chronic inflammation in patients with HS. Evidence has revealed that bacteria initiate and sustain the inflammation seen in patients with HS; therefore, reducing the amount of bacteria could alleviate some of the symptoms of HS.5 It is important to continue learning about the pathophysiology of this disease as well as formulating tailored treatments to minimize patient discomfort and improve quality of life.

Based on the findings of the current study and the safety profile of the medication, tetracyclines may be considered for first-line empiric therapy in patients with HS involving the axilla only, buttocks only, or multiple sites. For additional coverage of P mirabilis in the axilla or inframammary region, TMP/SMX monotherapy or tetracycline plus ampicillin may be considered. For inframammary lesions only, empiric treatment with ampicillin or TMP/ SMX is recommended. For HS lesions in the groin area, coverage of Enterococcus species with ampicillin should be considered. Patients with multiple sites of involvement that include the inframammary or groin regions similarly should receive empiric antibiotics that cover both S aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, such as TMP/SMX or tetracycline and ampicillin, respectively; if the multiple sites do not include the inframammary or groin regions, Gram-negative coverage may not be indicated. Based on our findings, standardization of treatment for patients with HS can allow for earlier and potentially more effective treatment.

In a similar study conducted in 2016, bacteria species were isolated from the axilla, groin, and gluteus/perineum in patients with HS.5 In that study, the most prominent bacteria in the axilla was CoNS; in the groin, P mirabilis and E coli; and in the gluteus/perineum, E coli and CoNS. These results differed from ours, which found S aureus as the abundant bacteria in these areas. In the 2016 study, the highest rates of resistance were found for penicillin G, erythromycin, clindamycin, and ampicillin.5 In contrast, the current study found high sensitivities for clindamycin and ampicillin, but our results support the finding of high resistance for erythromycin. These differences could be accounted for by the lower sample size of patients in the 2016 study: 68 patients were analyzed for sensitivity results, and 171 patients were analyzed for frequency of bacterial species in patients with HS.5

Our study is limited by its relatively small sample size. Additionally, all patients were seen at 1 of 2 clinic sites, located in League City and Galveston, Texas, and the data from this geographic area may not be applicable to patients seen in different climates.

Conclusion

Outcomes for patients with HS improve with early intervention; however, HS treatment may be delayed by selection of ineffective antibiotic therapy. Our study provides clinicians with recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment based on anatomic location of HS lesions and culture sensitivity profiles. Utilizing tailored antibiotic therapy on initial clinical evaluation may increase early disease control and improve morbidity and disease outcomes, thereby increasing patient quality of life.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic scarring inflammatory skin condition of the follicular epithelium that impacts 1% to 4% of the general population (eFigure).1-3 This statistic likely is an underrepresentation of the affected population due to missed and delayed diagnoses.1 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been identified as having one of the strongest negative impacts on patients’ lives based on studied skin diseases.4 Its recurrent nature can negatively impact both the patient’s physical and mental state.3 Due to the debilitating effects of HS, we aimed to create updated recommendations for empiric antibotics based on affected anatomic locations in an effort to improve patient quality of life.

Methods

An institutional review board–approved retrospective medical chart review of 485 patients diagnosed with HS and evaluated at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston from January 2006 to December 2021 was conducted. Males and females of all ages (including pregnant and pediatric patients) were included. Only patients for whom anatomic locations of HS lesions or culture sites were not documented were excluded from the analysis. Locations of cultures were categorized into 5 groups: axilla; groin; buttocks; inframammary; and multiple sites of involvement, which included any combination of 2 or more sites. Types of bacteria collected from cultures and recorded included Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and other Gram-negative species. Sensitivity profiles also were analyzed for the most commonly cultured bacteria to create recommendations on antibiotic use based on the anatomic location of the lesions. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis.

Results

The analysis included 485 patients comprising 600 visits. Seventy-five percent (363/485) of the study population was female. The axilla was the most common anatomic location for HS lesions followed by multiple sites of involvement. In total, 283 cultures were performed; males were 1.1 times more likely than females to be cultured. While cultures were most frequently obtained in patients with axillary lesions only (93/262 [35%]) or from multiple sites of involvement (83/179 [46%]) as this was the most common presentation of HS in our patient population, cultures were more likely to be obtained when patients presented with only buttock (32/38 [84%]) and inframammary (20/25 [80%]) lesions (Table).

Staphylococcus aureus was the most commonly cultured bacteria in general (53/283 [19%]) as well as for HS located the axilla (24/56 [43%]) and in multiple sites (16/51 [31%]). Proteus mirabilis (29/283 [10%]) was the second most commonly cultured bacteria overall and was cultured most often in the axilla (15/56 [27%]) and inframammary region (6/14 [43%]). These were followed by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species (26/283 [9%]) and Enterococcus species (21/283 [7%]), which was second to P mirabilis as the most commonly cultured bacteria in the inframammary region (6/14 [43%])(eTable 1).

eTable 2 shows the sensitivity profiles for the most commonly cultured bacteria: S aureus, P mirabilis, and Enterococcus species. Staphylococcus aureus located in the axilla, buttocks, and groin was most sensitive to rifampin (41/44 [93%]), TMP/SMX (41/44 [93%]), and tetracycline (39/44 [89%]) and most resistant to erythromycin (26/44 [59%]) and oxacillin (24/44 [55%]). Proteus mirabilis in the inframammary region was most sensitive to ampicillin (27/27 [100%]), gentamicin (27/27 [100%]), levofloxacin (27/27 [100%]), and TMP/SMX (26/27 [96%]). Enterococcus species were most sensitive to vancomycin (20/20 [100%]) and ampicillin (19/20 [95%]) and most resistant to gentamicin (5/20 [25%]).

Comment

To treat HS, it is important to understand the cause of the condition. Although the pathogenesis of HS has many unknowns, bacterial colonization and biofilms are thought to play a role. Lipopolysaccharides found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are pathogen-associated molecular patterns that present to the toll-like receptors of the human immune system. Once the toll-like receptors recognize the pathogen-associated molecular patterns, macrophages and keratinocytes are activated and release proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Persistent presentation of bacteria to the immune system increases immune-cell recruitment and worsens chronic inflammation in patients with HS. Evidence has revealed that bacteria initiate and sustain the inflammation seen in patients with HS; therefore, reducing the amount of bacteria could alleviate some of the symptoms of HS.5 It is important to continue learning about the pathophysiology of this disease as well as formulating tailored treatments to minimize patient discomfort and improve quality of life.

Based on the findings of the current study and the safety profile of the medication, tetracyclines may be considered for first-line empiric therapy in patients with HS involving the axilla only, buttocks only, or multiple sites. For additional coverage of P mirabilis in the axilla or inframammary region, TMP/SMX monotherapy or tetracycline plus ampicillin may be considered. For inframammary lesions only, empiric treatment with ampicillin or TMP/ SMX is recommended. For HS lesions in the groin area, coverage of Enterococcus species with ampicillin should be considered. Patients with multiple sites of involvement that include the inframammary or groin regions similarly should receive empiric antibiotics that cover both S aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, such as TMP/SMX or tetracycline and ampicillin, respectively; if the multiple sites do not include the inframammary or groin regions, Gram-negative coverage may not be indicated. Based on our findings, standardization of treatment for patients with HS can allow for earlier and potentially more effective treatment.

In a similar study conducted in 2016, bacteria species were isolated from the axilla, groin, and gluteus/perineum in patients with HS.5 In that study, the most prominent bacteria in the axilla was CoNS; in the groin, P mirabilis and E coli; and in the gluteus/perineum, E coli and CoNS. These results differed from ours, which found S aureus as the abundant bacteria in these areas. In the 2016 study, the highest rates of resistance were found for penicillin G, erythromycin, clindamycin, and ampicillin.5 In contrast, the current study found high sensitivities for clindamycin and ampicillin, but our results support the finding of high resistance for erythromycin. These differences could be accounted for by the lower sample size of patients in the 2016 study: 68 patients were analyzed for sensitivity results, and 171 patients were analyzed for frequency of bacterial species in patients with HS.5

Our study is limited by its relatively small sample size. Additionally, all patients were seen at 1 of 2 clinic sites, located in League City and Galveston, Texas, and the data from this geographic area may not be applicable to patients seen in different climates.

Conclusion

Outcomes for patients with HS improve with early intervention; however, HS treatment may be delayed by selection of ineffective antibiotic therapy. Our study provides clinicians with recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment based on anatomic location of HS lesions and culture sensitivity profiles. Utilizing tailored antibiotic therapy on initial clinical evaluation may increase early disease control and improve morbidity and disease outcomes, thereby increasing patient quality of life.

- Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-563.

- Yazdanyar S, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of cause and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:118-123.

- Hessam S, Sand M, Georgas D, et al. Microbial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria found in inflammatory hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016; 29:161-167.

- Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-561; quiz 562-563.

- Yazdanyar S, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of cause and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:118-123.

- Hessam S, Sand M, Georgas D, et al. Microbial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria found in inflammatory hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016; 29:161-167.

Recommendations for Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Recommendations for Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa

PRACTICE POINTS

- The inflammation seen in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is initiated and sustained by bacteria; therefore, reducing the number of bacteria may alleviate some of the symptoms of HS.

- For HS involving the axillae or buttocks, tetracyclines should be recommended as first-line empiric therapy.

- Patients with HS with multiple sites affected that include the inframammary or groin regions should receive empiric antibiotics that cover both Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or tetracycline plus ampicillin.

The Dermatologist Nose Best: Correlation of Nose-Picking Habits and <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i>–Related Dermatologic Disease

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

Practice Points

- Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of approximately 20% to 80% of humans and can play a large factor in dermatologic disease.

- Staphylococcus aureus decolonization practices for at-risk dermatology patients may overlook the role that nose-picking plays.