User login

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has arrived

A 50-year-old woman with hypertension presents with a history of polyarticular small-joint pain for the last 3 months. Her pain is worse in the morning, and it affects her metacarpal, proximal, and distal phalangeal joints. She describes intermittent swelling of her hands and morning stiffness lasting 15 to 30 minutes.

Her physical examination is unremarkable, with no evidence of active inflammation (synovitis), joint tenderness, restrictions in movement, or deformity. Her description of her symptoms raises suspicion for an inflammatory arthritis, but her physical examination does not support this diagnosis.

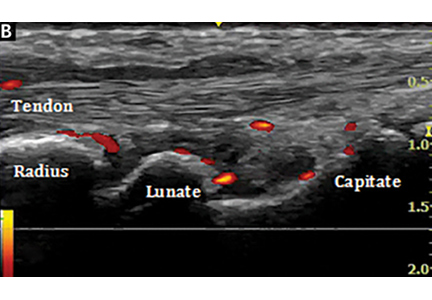

Bedside musculoskeletal ultrasonography of her wrists reveals synovial hypertrophy, and power Doppler shows active inflammation, findings consistent with synovitis (Figure 1).

This scenario illustrates how musculoskeletal ultrasonography can prevent delayed diagnosis, thus directing the ordering of appropriate laboratory studies and allowing treatment for pain relief to be started promptly.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY HAS GAINED A SOLID ROLE

Ultrasonography has gained a solid role in the care of patients with musculoskeletal conditions.

Using obtained images, as well as power Doppler to assess inflammation, the clinician can visualize superficial anatomic structures, including the skin, muscles, joints, nerves, and the cortical layer of bone. Combining the dynamic assessment with the clinical history and findings of the physical examination makes musculoskeletal ultrasonography a powerful tool for diagnosis and management.1

In this issue, Forney and Delzell2 review the clinical use of ultrasonography of the muscles and bones and its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods. They describe its gain in popularity over the last decade and its incorporation into clinical care in multiple medical subspecialties.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is performed and interpreted by specially trained sonographers. It should be viewed as a complementary procedure, not as a replacement for a thorough and systematic clinical examination.3

ADVANTAGES ARE MANY

A major advantage of musculoskeletal ultrasonography over other imaging techniques is its capacity to dynamically assess joint and tendon movements4 and to immediately interpret them in real time.

In rheumatology, where it has made the biggest impact, it can help evaluate inflammatory and noninflammatory rheumatic diseases, assess treatment response, and guide joint injections.1 It has been demonstrated to significantly improve timely diagnosis and management,5 decrease dependence on other imaging modalities, and reduce healthcare costs.6

With its easy portability, ultrasonography has also been integrated into orthopedics, podiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, sports medicine, and emergency medicine. Its role is expanding to include the assessment of the skin in systemic sclerosis, parotid and submandibular glands in Sjögren syndrome, nails in patients with psoriasis, and temporal arteries in giant cell arteritis.

A ROLE IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has entered into medical education, with an increasing number of medical schools incorporating it into their curriculum over the last few years.7 It enhances student learning of anatomy, the physical examination, and pathologic findings of rheumatic diseases.7,8 Some internal medicine residency programs have added ultrasonography to help identify anatomic structures for invasive procedures, increasing patient safety and reducing procedural complications.9

It has been incorporated into the core curriculum in many rheumatology fellowship training programs.10 Rheumatologists can now also take additional courses to enhance their skills and become certified sonographers.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has proven to be a useful adjunct to the physical examination. With its many advantages, it has gained acceptance and is now a mainstay in many subspecialties.

- Cannella AC, Kissin EY, Torralba KD, Higgs JB, Kaeley GS. Evolution of musculoskeletal ultrasound in the United States: implementation and practice in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):7–13. doi:10.1002/acr.22183

- Forney MC, Delzell PB. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography basics. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(4):283–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17014

- McAlindon T, Kissin E, Nazarian L, et al. American College of Rheumatology report on reasonable use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography in rheumatology clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64(11):1625–1640. doi:10.1002/acr.21836

- Backhaus M, Burmester GR, Gerber T, et al; Working Group for Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in the EULAR Standing Committee on International Clinical Studies including Therapeutic Trials. Guidelines for musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60(7):641–649.

- Micu MC, Alcalde M, Saenz JI, et al. Impact of musculoskeletal ultrasound in an outpatient rheumatology clinic. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(4):615–621. doi:10.1002/acr.21853

- Kay JC, Higgs JB, Battafarano DF. Utility of musculoskeletal ultrasound in a Department of Defense rheumatology practice: a four-year retrospective experience. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):14–18. doi:10.1002/acr.22127

- Dinh VA, Fu JY, Lu S, Chiem A, Fox JC, Blaivas M. Integration of ultrasound in medical education at United States medical schools. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35(2):413–419. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.05073

- Wright SA, Bell AL. Enhancement of undergraduate rheumatology teaching through the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47(10):1564–1566. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken324

- Keddis MT, Cullen MW, Reed DA, et al. Effectiveness of an ultrasound training module for internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ 2011; 11:75. doi:0.1186/1472-6920-11-75

- Torralba K, Cannella AC, Kissin EY, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound instruction in adult rheumatology fellowship programs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1002/acr.23336

A 50-year-old woman with hypertension presents with a history of polyarticular small-joint pain for the last 3 months. Her pain is worse in the morning, and it affects her metacarpal, proximal, and distal phalangeal joints. She describes intermittent swelling of her hands and morning stiffness lasting 15 to 30 minutes.

Her physical examination is unremarkable, with no evidence of active inflammation (synovitis), joint tenderness, restrictions in movement, or deformity. Her description of her symptoms raises suspicion for an inflammatory arthritis, but her physical examination does not support this diagnosis.

Bedside musculoskeletal ultrasonography of her wrists reveals synovial hypertrophy, and power Doppler shows active inflammation, findings consistent with synovitis (Figure 1).

This scenario illustrates how musculoskeletal ultrasonography can prevent delayed diagnosis, thus directing the ordering of appropriate laboratory studies and allowing treatment for pain relief to be started promptly.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY HAS GAINED A SOLID ROLE

Ultrasonography has gained a solid role in the care of patients with musculoskeletal conditions.

Using obtained images, as well as power Doppler to assess inflammation, the clinician can visualize superficial anatomic structures, including the skin, muscles, joints, nerves, and the cortical layer of bone. Combining the dynamic assessment with the clinical history and findings of the physical examination makes musculoskeletal ultrasonography a powerful tool for diagnosis and management.1

In this issue, Forney and Delzell2 review the clinical use of ultrasonography of the muscles and bones and its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods. They describe its gain in popularity over the last decade and its incorporation into clinical care in multiple medical subspecialties.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is performed and interpreted by specially trained sonographers. It should be viewed as a complementary procedure, not as a replacement for a thorough and systematic clinical examination.3

ADVANTAGES ARE MANY

A major advantage of musculoskeletal ultrasonography over other imaging techniques is its capacity to dynamically assess joint and tendon movements4 and to immediately interpret them in real time.

In rheumatology, where it has made the biggest impact, it can help evaluate inflammatory and noninflammatory rheumatic diseases, assess treatment response, and guide joint injections.1 It has been demonstrated to significantly improve timely diagnosis and management,5 decrease dependence on other imaging modalities, and reduce healthcare costs.6

With its easy portability, ultrasonography has also been integrated into orthopedics, podiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, sports medicine, and emergency medicine. Its role is expanding to include the assessment of the skin in systemic sclerosis, parotid and submandibular glands in Sjögren syndrome, nails in patients with psoriasis, and temporal arteries in giant cell arteritis.

A ROLE IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has entered into medical education, with an increasing number of medical schools incorporating it into their curriculum over the last few years.7 It enhances student learning of anatomy, the physical examination, and pathologic findings of rheumatic diseases.7,8 Some internal medicine residency programs have added ultrasonography to help identify anatomic structures for invasive procedures, increasing patient safety and reducing procedural complications.9

It has been incorporated into the core curriculum in many rheumatology fellowship training programs.10 Rheumatologists can now also take additional courses to enhance their skills and become certified sonographers.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has proven to be a useful adjunct to the physical examination. With its many advantages, it has gained acceptance and is now a mainstay in many subspecialties.

A 50-year-old woman with hypertension presents with a history of polyarticular small-joint pain for the last 3 months. Her pain is worse in the morning, and it affects her metacarpal, proximal, and distal phalangeal joints. She describes intermittent swelling of her hands and morning stiffness lasting 15 to 30 minutes.

Her physical examination is unremarkable, with no evidence of active inflammation (synovitis), joint tenderness, restrictions in movement, or deformity. Her description of her symptoms raises suspicion for an inflammatory arthritis, but her physical examination does not support this diagnosis.

Bedside musculoskeletal ultrasonography of her wrists reveals synovial hypertrophy, and power Doppler shows active inflammation, findings consistent with synovitis (Figure 1).

This scenario illustrates how musculoskeletal ultrasonography can prevent delayed diagnosis, thus directing the ordering of appropriate laboratory studies and allowing treatment for pain relief to be started promptly.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY HAS GAINED A SOLID ROLE

Ultrasonography has gained a solid role in the care of patients with musculoskeletal conditions.

Using obtained images, as well as power Doppler to assess inflammation, the clinician can visualize superficial anatomic structures, including the skin, muscles, joints, nerves, and the cortical layer of bone. Combining the dynamic assessment with the clinical history and findings of the physical examination makes musculoskeletal ultrasonography a powerful tool for diagnosis and management.1

In this issue, Forney and Delzell2 review the clinical use of ultrasonography of the muscles and bones and its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods. They describe its gain in popularity over the last decade and its incorporation into clinical care in multiple medical subspecialties.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is performed and interpreted by specially trained sonographers. It should be viewed as a complementary procedure, not as a replacement for a thorough and systematic clinical examination.3

ADVANTAGES ARE MANY

A major advantage of musculoskeletal ultrasonography over other imaging techniques is its capacity to dynamically assess joint and tendon movements4 and to immediately interpret them in real time.

In rheumatology, where it has made the biggest impact, it can help evaluate inflammatory and noninflammatory rheumatic diseases, assess treatment response, and guide joint injections.1 It has been demonstrated to significantly improve timely diagnosis and management,5 decrease dependence on other imaging modalities, and reduce healthcare costs.6

With its easy portability, ultrasonography has also been integrated into orthopedics, podiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, sports medicine, and emergency medicine. Its role is expanding to include the assessment of the skin in systemic sclerosis, parotid and submandibular glands in Sjögren syndrome, nails in patients with psoriasis, and temporal arteries in giant cell arteritis.

A ROLE IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has entered into medical education, with an increasing number of medical schools incorporating it into their curriculum over the last few years.7 It enhances student learning of anatomy, the physical examination, and pathologic findings of rheumatic diseases.7,8 Some internal medicine residency programs have added ultrasonography to help identify anatomic structures for invasive procedures, increasing patient safety and reducing procedural complications.9

It has been incorporated into the core curriculum in many rheumatology fellowship training programs.10 Rheumatologists can now also take additional courses to enhance their skills and become certified sonographers.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has proven to be a useful adjunct to the physical examination. With its many advantages, it has gained acceptance and is now a mainstay in many subspecialties.

- Cannella AC, Kissin EY, Torralba KD, Higgs JB, Kaeley GS. Evolution of musculoskeletal ultrasound in the United States: implementation and practice in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):7–13. doi:10.1002/acr.22183

- Forney MC, Delzell PB. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography basics. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(4):283–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17014

- McAlindon T, Kissin E, Nazarian L, et al. American College of Rheumatology report on reasonable use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography in rheumatology clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64(11):1625–1640. doi:10.1002/acr.21836

- Backhaus M, Burmester GR, Gerber T, et al; Working Group for Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in the EULAR Standing Committee on International Clinical Studies including Therapeutic Trials. Guidelines for musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60(7):641–649.

- Micu MC, Alcalde M, Saenz JI, et al. Impact of musculoskeletal ultrasound in an outpatient rheumatology clinic. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(4):615–621. doi:10.1002/acr.21853

- Kay JC, Higgs JB, Battafarano DF. Utility of musculoskeletal ultrasound in a Department of Defense rheumatology practice: a four-year retrospective experience. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):14–18. doi:10.1002/acr.22127

- Dinh VA, Fu JY, Lu S, Chiem A, Fox JC, Blaivas M. Integration of ultrasound in medical education at United States medical schools. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35(2):413–419. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.05073

- Wright SA, Bell AL. Enhancement of undergraduate rheumatology teaching through the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47(10):1564–1566. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken324

- Keddis MT, Cullen MW, Reed DA, et al. Effectiveness of an ultrasound training module for internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ 2011; 11:75. doi:0.1186/1472-6920-11-75

- Torralba K, Cannella AC, Kissin EY, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound instruction in adult rheumatology fellowship programs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1002/acr.23336

- Cannella AC, Kissin EY, Torralba KD, Higgs JB, Kaeley GS. Evolution of musculoskeletal ultrasound in the United States: implementation and practice in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):7–13. doi:10.1002/acr.22183

- Forney MC, Delzell PB. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography basics. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(4):283–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17014

- McAlindon T, Kissin E, Nazarian L, et al. American College of Rheumatology report on reasonable use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography in rheumatology clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64(11):1625–1640. doi:10.1002/acr.21836

- Backhaus M, Burmester GR, Gerber T, et al; Working Group for Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in the EULAR Standing Committee on International Clinical Studies including Therapeutic Trials. Guidelines for musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60(7):641–649.

- Micu MC, Alcalde M, Saenz JI, et al. Impact of musculoskeletal ultrasound in an outpatient rheumatology clinic. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(4):615–621. doi:10.1002/acr.21853

- Kay JC, Higgs JB, Battafarano DF. Utility of musculoskeletal ultrasound in a Department of Defense rheumatology practice: a four-year retrospective experience. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(1):14–18. doi:10.1002/acr.22127

- Dinh VA, Fu JY, Lu S, Chiem A, Fox JC, Blaivas M. Integration of ultrasound in medical education at United States medical schools. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35(2):413–419. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.05073

- Wright SA, Bell AL. Enhancement of undergraduate rheumatology teaching through the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47(10):1564–1566. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken324

- Keddis MT, Cullen MW, Reed DA, et al. Effectiveness of an ultrasound training module for internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ 2011; 11:75. doi:0.1186/1472-6920-11-75

- Torralba K, Cannella AC, Kissin EY, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound instruction in adult rheumatology fellowship programs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1002/acr.23336

Management of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in a Multidisciplinary Rheumatology/Dermatology Clinic

Psoriasis is a commonly encountered systemic condition, usually presenting with chronic erythematous plaques with an overlying silvery white scale.1 Extracutaneous manifestations, such as joint or spine (axial) involvement, can occur along with this skin disorder. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, heterogeneous disorder characterized by inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriasis.2,3 Until recently treatment of PsA has been limited to a few medications.

Continuing investigations into the pathogenesis of PsA have revealed new treatment options, targeting molecules at the cellular level. Over the past few years, additional medications have been approved, giving providers more options in treating patients with psoriasis and PsA. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach by both rheumatologists and dermatologists in evaluating and managing patients at VA clinics has helped optimize care of these patients by providing timely evaluation and treatment at the same visit.

Psoriasis Presentation and Diagnosis

Genetic predisposition and certain environmental factors (trauma, infection, medications) are known to trigger psoriasis, which can present in many forms.4 Chronic plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common skin pattern with a classic presentation of sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale.4 It affects the scalp, lower back, umbilicus, genitals, and extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees. Guttate psoriasis is recognized by its multiple small papules and plaques in a droplike pattern. Pustular psoriasis usually presents with widespread pustules. On the other hand, erythrodermic psoriasis manifests as diffuse erythema involving multiple skin areas.4 Erythematous psoriatic plaques, which are predominantly in the intertriginous areas or skin folds (inguinal, perineal, genital, intergluteal, axillary, or inframammary), are known as inverse psoriasis.

A psoriasis diagnosis is made by taking a history and a physical examination. Rarely, a skin biopsy of the lesions will be required for an atypical presentation. The course of the disease is unpredictable, variable, and dependent on the type of psoriasis. Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic condition, whereas guttate psoriasis is often self-limited.4 A poorer prognosis is seen in patients with erythrodermic and generalized pustular psoriasis.4

Psoriatic Arthritis Presentation, Classification, and Diagnosis

Prevalence of PsA is not known, but it is estimated to be from 0.3% to 1% of the U.S. population. In the psoriasis population, PsA is reported to range from 7% to 42%,3 although more recently, these numbers have been found to be in the 15% to 25% range (unpublished observations). This type of inflammatory arthritis can develop at any age but usually is seen between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with men being affected equally or a little more than are women.3 Clinical symptoms usually include pain and stiffness of affected joints, > 30 minutes of morning stiffness, and fatigue.

The presentation of joint involvement can vary widely. Five subtypes of arthritis were identified by Moll and Wright in 1973, which included arthritis with predominant distal interphalangeal involvement, arthritis mutilans, symmetric polyarthritis (> 5 joints), asymmetric oligoarthritis (1-4 joints), and predominant spondylitis (axial).5 Patients with PsA may also have evidence of spondylitis (inflammation of vertebra) or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) with back pain > 3 months, hip or buttock pain, nighttime pain, or pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest.6 The cervical spine is more frequently involved than is the lumbar spine in patients with PsA.3

Psoriatic arthritis can have a diverse presentation not only with the affected joints, but also involving nails, tendons, and ligaments. An entire digit of the hand or foot can become swollen, known as dactylitis, or “sausage digit.” Inflammation at the insertion of tendons or ligaments, known as enthesitis, is also seen in PsA. Most common sites include the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and ligamentous insertions around the pelvic bones.3 Nail changes that are typically seen in patients with psoriasis can be seen in PsA as well, including pitting, ridging, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis.3 Ocular inflammation which is classically seen with other spondyloarthropathies, can be seen in patients with PsA as well, frequently manifesting as conjunctivitis.2,3

Psoriatic arthritis is commonly classified under the broader category of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, given the low frequency of a positive rheumatoid factor.3 Currently, there are no laboratory tests that can help with a PsA diagnosis.3 Acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated, indicating active inflammation.

Radiographic data, such as X-rays of the hands and feet, can confirm the clinical distribution of joint involvement and show evidence of erosive changes. Further destructive changes include osteolysis (bone resorption) that may cause the classic pencil-in-cup deformity, typically seen in arthritis mutilans (Figure 1).3 Other radiographic evidence of PsA can include proliferative changes with new bone formation seen along the shaft of the metacarpal and metatarsal bones.3 Patients with axial involvement can have evidence of asymmetric sacroiliitis, which can be seen on radiographs. Asymmetric syndesmophytes, or bony outgrowths, can also be seen throughout the axial spine.3

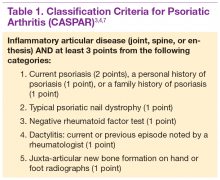

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical presentation of a patient with the help of laboratory work and radiographs. Other forms of arthritis (such as rheumatoid arthritis, crystal arthropathies, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis) should be excluded. Given the varied presentation of PsA, classification criteria have been developed to assist in clinical research. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) have been developed and validated as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis and a source for clinical research (Table 1).7 Musculoskeletal pain in patients with psoriasis can be due to causes other than PsA, such as osteoarthritis and gout. A close working relationship in a combined rheumatology/dermatology clinic is vital to providing optimal diagnostic and treatment care for patients with psoriasis and PsA.8

The etiology of PsA is currently unknown, although many genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors have been identified that play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. In this setting, immunologically mediated processes that cause inflammation occur in the synovium of joints, enthesium, bone, and skin of patients with PsA.9 Studies have shown that activated T cells and T-cell–derived cytokines play an important role in cartilage degradation, joint damage, and stimulating bone resorption.9

One particular proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), has been the target for many treatment modalities for several years. With new and ongoing research into the PsA pathogenesis, other treatment options have been discovered, targeting different cytokines and T cells that are involved in the disease process. This has led to drug trials and recent FDA approvals of several new medications, which provide further options for clinicians in managing and treating PsA.

Management of Psoriasis

Choice of therapy is determined by the extent and severity of psoriasis (body surface area [BSA] involvement) as well as the patient’s comorbidities and preferences.4 Providers have a wide spectrum of effective therapies to prescribe, both topically and systemically. Topical therapy options include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 and analogs (calcipotriene), anthralin, tar, tazarotene (third-generation retinoid), and calcineurin inhibitors (tacromlimus).4 Phototherapy with or without saltwater baths helps improve skin lesions.

These treatments are beneficial for all patients with psoriasis, but the disease can be controlled with monotherapy in patients with mild-to-moderate disease (< 10% BSA). Limiting these treatment options are some long-term effects of the medications because of the potential for toxicity as well as decreasing efficacy of the medication over time.4 For patients with more BSA involvement (> 10%), systemic treatment options include methotrexate (MTX), systemic retinoids (acitretin), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine), and biologics. Many of these systemic treatment options overlap for patients with both psoriasis and PsA, and topical treatments can be used adjunctively to better control the skin disease.

Management of Psoriatic Arthritis

It is important to identify PsA and begin treatment early, because it has been shown that patients tend to fare better in their disease course if treated early.10 Once a diagnosis of PsA is made, disease activity needs to be determined by clinical examination and radiographs of joints. Scoring systems, by assessing bone erosions and deformities on joint radiographs, can aide with this assessment. Based on these, PsA can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. Several disease activity measures that have been developed for clinical trials in monitoring of disease activity can be used as an aide in the office setting. These tools are still being studied to determine the optimal measure of disease activity.

NSAIDs and Glucocorticoids

Controlling inflammation and providing pain relief are the primary treatment goals for patients with PsA. In mild, predominantly peripheral PsA, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used, but they do not halt disease progression. If the disease is controlled and not progressing, NSAIDs may be used as the only treatment. However, if symptoms persist and/or there is more joint involvement, the next level of therapy should be sought. Intra-articular corticosteroids for symptomatic relief can be given if only a few joints are affected. Oral corticosteroids can be used occasionally in patients with multiple joint aches, but they are typically avoided or tapered slowly to avoid worsening the patient’s skin psoriasis or having it evolve into a more severe form, such as pustular psoriasis.10 All these treatments can alleviate symptoms, but they do not prevent the progression of disease.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

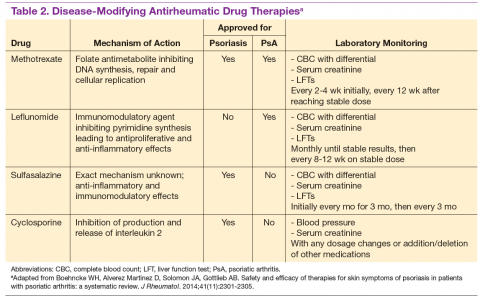

For patients who fail NSAIDs or present initially with more joint involvement (polyarthritis or > 5 swollen joints), traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be started (Table 2). Methotrexate is one of the first-line DMARD prescriptions. It is commonly used because of its effectiveness in treating both skin and joint involvement, despite limited evidence of its efficacy in controlled clinical trials for slowing the progression of joint damage in PsA.2,9-11 Methotrexate can be given orally or subcutaneously (SC) every week. Routine laboratory monitoring is required given the known effects of MTX on liver and bone marrow suppression. Clinical monitoring is needed as well due to its well-known risk for pulmonary toxicity and teratogenicity.2

Leflunomide is another traditional oral DMARD that is administered daily. It has be shown to be effective in PsA, with only a modest effect in improving skin lesions.12 Laboratory monitoring is identical to that required with MTX. Adverse effects (AEs) include diarrhea and increased risk of elevated transaminases.9 Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is also used as a traditional DMARD and shown to have an effective clinical response in treating peripheral arthritis but not in axial or skin disease.9,12 Not all studies have shown effective responses to SSZ. The primary AE is gastrointestinal, making this a frequently discontinued medication.2 Cyclosporine is more commonly used in psoriasis but can be used on its own or with MTX for treating patients with PsA.10 It is often not tolerated well and frequently discontinued, due to major AEs, including hypertension and renal dysfunction.2,10

These traditional DMARDs are usually given for 3 to 6 months.13 After this initial period, the patient’s clinical response is reassessed, and the need for changing therapy to another DMARD or biologic is determined.

Biologic Therapies

With the discovery of TNFα as a potent cytokine in inflammatory arthritis came a new class of medications that has provided patients and providers with more effective treatment options. This category of medications is known as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis). Five medications have been developed that target TNFα, each in its own way: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certrolizumab pegol. These medications were initially studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with further clinical trials performed for treatment of PsA. Each is prescribed differently: Adalimumab and certrolizumab are given SC every 2 weeks, etanercept is given weekly, and golimumab is given once a month. Infliximab is the only medication prescribed as an infusion, which is administered every 8 weeks after receiving 3 loading doses.

Studies have shown that all TNFis are effective in treating PsA: improving joint disease activity, inhibiting progression of structural damage, and improving function and overall quality of life.10 The TNFi drugs also improve psoriasis along with dactylitis, enthesitis, and nail changes.13 Patients with

axial disease benefit from TNFi, but the evidence of TNFi effectiveness is extrapolated from studies in axial spondyloarthritis.13,14 Tumor necrosis

factor inhibitors can be used as monotherapy, although there is some evidence for using TNFi drugs with MTX in PsA. Combination therapy can potentially prolong the survival of the TNFi drug or prevent formation of antidrug antibodies.14,15

The current evidence for monotherapy vs combination therapy in patients with PsA is not consistent, and no formal guidelines have been developed to guide physicians one way or another. The TNFi drugs are generally well tolerated, although the patient needs to learn how to self-inject if given the SC route. Adverse effects include infusion or injection site reactions and infections. Prior to starting a TNFi, it is prudent to screen for latent tuberculosis infection as well as hepatitis B and C, given the risk of reactivation. Clinical response is monitored for 3 months, and if remission or low disease activity is not reached, a different TNFi may be tried.13 Importantly, patients receiving infliximab without clinical improvement in 3 months may have their dose and frequency increased before switching to an alternative TNFi. Some studies show that a trial of a second TNFi has a less potent response than with a first TNFi, and the drug survival is shorter in duration.13

One of the newest biologic agents approved for treating PsA is ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody (MAB) that inhibits receptor binding of cytokines interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23. These cytokines have been identified in patients with psoriasis and PsA as further promoting inflammation. Ustekinumab recently received approval for the treatment of PsA and is given SC every 12 weeks after 2 initial doses. Further studies have also confirmed ustekinumab significantly suppressed radiographic progression of joint damage in patients with active PsA.15 Notable AEs included infections, but there have been no cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infections reported.16

The most recent FDA-approved medication for PsA is apremilast. It is a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, which causes the suppression of other proinflammatory mediators and cytokines active in the immune system.10 It is given orally, uptitrating the doses over a few days until the twice-daily maintenance dosing is achieved. It is generally well tolerated with nausea and diarrhea as the most common AEs.17 Further studies need to be conducted to assess whether this agent is able to prevent or decrease joint damage.

Other potential treatment options are currently undergoing trials to assess their efficacy and safety in treating psoriasis and/or PsA. One class targets the IL-17 cytokine pathway and includes brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody (MAB) anti-IL-17 receptor, ixekizumab and secukinumab, both MABs anti-IL-17A. Secukinumab has already received FDA approval for the treatment of plaque psoriasis (2015). Other agents currently undergoing trials are abatacept (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-Ig), a recombinant human fusion protein that blocks the co-stimulation of T cells9 and tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor.18 Early studies show patients achieving a response with these medications, but further long-term studies are needed.19

Treatment Recommendations

Treatment approaches differ for patients with only psoriasis and patients with psoriasis and PsA, although some treatment modalities overlap. Recommendations for PsA have been set for each domain affected (Figure 2). The treatment approach is based on several factors, including severity or the degree of disease activity, any joint damage, and the patient’s comorbidities. Certain comorbidities are associated with PsA—cardiovascular disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, fatty liver disease, chronic viral infections (hepatitis B or C), and kidney disease. These comorbidities can affect the choice of therapy for the patient.20,21 Other factors affecting treatment choices include patient preference regarding mode and frequency of administration of the medication, potential AEs, requirements of laboratory monitoring or regular doctor visits, and the cost of medications.10,22

In treating patients with psoriasis and PsA, a multidisciplinary approach is needed. Because skin manifestations of psoriasis usually develop prior to arthritis symptoms in most patients, primary care providers and dermatologists can routinely screen patients for arthritis.10 Rheumatologists can confirm arthritis and musculoskeletal involvement, but the treatment and management of these patients will need to be in collaboration with a dermatologist. The goal of comanagement is to choose appropriate therapies that may be able to treat both the skin and musculoskeletal manifestations.

A multidisciplinary approach can also limit polypharmacy, control costs, and reduce AEs. The existence of VA combined rheumatology and dermatology clinics makes this an invaluable experience for the veteran with direct and focused patient management. In addition to controlling disease activity, the goal of treatment is to improve function and the patient’s quality of life, halting structural joint damage to prevent disability.10 Physical and occupational therapies play an important role in PsA management as does exercise. Patients should be educated about their disease and treatment options discussed. It is also important to identify and reduce significant comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, to decrease mortality and improve life expectancy.10

Conclusion

Psoriasis is a distinct disease entity but can occur along with extracutaneous features. Patients with psoriasis need to be screened for PsA, and it is important to diagnose PsA early to begin appropriate treatment. Disease activity, severity, and any joint damage will determine therapy. Over the past decade, new treatment options have become available that provide more choices for patients than those of the standard DMARDs. The TNFis have proven to be efficacious in treating psoriasis and PsA. With a better understanding of pathogenesis of these diseases, new medications have been discovered targeting different parts of the immune system involved in dysregulation and ultimately inflammation. Additional clinical research is needed to provide physicians with more effective ways of controlling these diseases. Ultimately, the management of PsA is not solely based on medications, but the authors’ VA experience highlights the importance of a multispecialty approach to the management of psoriasis and PsA.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Schön MP, Boehncke W-H. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1899-1912.

2. Mease P, Goffe BS. Diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):1-19.

3. Clinical features of psoriatic arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2015:989-997.

4. Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol 1. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012.

5. Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3(1):55-78.

6. Mease PJ, Garg A, Helliwell PS, Park JJ, Gladman DD. Development of criteria to distinguish inflammatory from noninflammatory arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis: a report from the GRAPPA 2013 annual meeting. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(6):1249-1251.

7. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H; CASPAR Study Group. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2665-2673.

8. Mody E, Husni ME, Schur P, Qureshi AA. Multidisciplinary evaluation of patients with psoriasis presenting with musculoskeletal pain: a dermatology-rheumatology clinic experience. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(5):1050-1051.

9. Turkiewicz AM, Moreland LW. Psoriatic arthritis: current concepts on pathogenesis-oriented therapeutic options. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1051-1066.

10. Management of psoriatic arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH. Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2015:1008-1013.

11. Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):851-864.

12. Paccou J, Wendling D. Current treatment of psoriatic arthritis: update based on systemic literature review to establish French Society for Rheumatology (SFR) recommendations for managing spondyloarthropathies. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82(2):80-85.

13. Soriano ER, Acosta-Felquer ML, Luong P, Caplan L. Pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis with traditional biologic and nonbiologic DMARDs. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(5):793-806.

14. Behrens F, Cañete JD, Olivieri I, van Kuijk AW, McHugh N, Combe B. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor monotherapy vs combination with MTX in the treatment of PsA: a systemic review of the literature. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(5):915-926.

15. Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al; PSUMMIT-1 and 2 Study Groups. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1000-1006.

16. McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb A, et al; PSUMMIT 1 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):780-789.

17. Kavanaugh A, Mease P, Gomez-Reino J, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1020-1026.

18. Gao W, McGarry T, Orr C, McCormick J, Veale DJ, Fearon U.. Tofacitinib regulates

synovial inflammation in psoriatic arthritis, inhibiting STAT activation and induction of negative feedback inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015; pii: annrheumdis-2014-207201[Epub ahead of print].

19. Acosta Felquer ML, Coates LC, Soriano ER, et al. Drug therapies for peripheral joint disease in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(11):2277-2285.

20. Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT. Systematic review of treatments for psoriatic arthritis: 2014 update for the GRAPPA. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(11):2273-2276.

21. Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Eder L, et al. Comprehensive treatment of psoriatic arthritis: managing comorbidities and extraarticular manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(11):2315-2322.

22. Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Gladman DD, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA). Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(9):1387-1394.

Psoriasis is a commonly encountered systemic condition, usually presenting with chronic erythematous plaques with an overlying silvery white scale.1 Extracutaneous manifestations, such as joint or spine (axial) involvement, can occur along with this skin disorder. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, heterogeneous disorder characterized by inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriasis.2,3 Until recently treatment of PsA has been limited to a few medications.

Continuing investigations into the pathogenesis of PsA have revealed new treatment options, targeting molecules at the cellular level. Over the past few years, additional medications have been approved, giving providers more options in treating patients with psoriasis and PsA. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach by both rheumatologists and dermatologists in evaluating and managing patients at VA clinics has helped optimize care of these patients by providing timely evaluation and treatment at the same visit.

Psoriasis Presentation and Diagnosis

Genetic predisposition and certain environmental factors (trauma, infection, medications) are known to trigger psoriasis, which can present in many forms.4 Chronic plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common skin pattern with a classic presentation of sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale.4 It affects the scalp, lower back, umbilicus, genitals, and extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees. Guttate psoriasis is recognized by its multiple small papules and plaques in a droplike pattern. Pustular psoriasis usually presents with widespread pustules. On the other hand, erythrodermic psoriasis manifests as diffuse erythema involving multiple skin areas.4 Erythematous psoriatic plaques, which are predominantly in the intertriginous areas or skin folds (inguinal, perineal, genital, intergluteal, axillary, or inframammary), are known as inverse psoriasis.

A psoriasis diagnosis is made by taking a history and a physical examination. Rarely, a skin biopsy of the lesions will be required for an atypical presentation. The course of the disease is unpredictable, variable, and dependent on the type of psoriasis. Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic condition, whereas guttate psoriasis is often self-limited.4 A poorer prognosis is seen in patients with erythrodermic and generalized pustular psoriasis.4

Psoriatic Arthritis Presentation, Classification, and Diagnosis

Prevalence of PsA is not known, but it is estimated to be from 0.3% to 1% of the U.S. population. In the psoriasis population, PsA is reported to range from 7% to 42%,3 although more recently, these numbers have been found to be in the 15% to 25% range (unpublished observations). This type of inflammatory arthritis can develop at any age but usually is seen between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with men being affected equally or a little more than are women.3 Clinical symptoms usually include pain and stiffness of affected joints, > 30 minutes of morning stiffness, and fatigue.

The presentation of joint involvement can vary widely. Five subtypes of arthritis were identified by Moll and Wright in 1973, which included arthritis with predominant distal interphalangeal involvement, arthritis mutilans, symmetric polyarthritis (> 5 joints), asymmetric oligoarthritis (1-4 joints), and predominant spondylitis (axial).5 Patients with PsA may also have evidence of spondylitis (inflammation of vertebra) or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) with back pain > 3 months, hip or buttock pain, nighttime pain, or pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest.6 The cervical spine is more frequently involved than is the lumbar spine in patients with PsA.3

Psoriatic arthritis can have a diverse presentation not only with the affected joints, but also involving nails, tendons, and ligaments. An entire digit of the hand or foot can become swollen, known as dactylitis, or “sausage digit.” Inflammation at the insertion of tendons or ligaments, known as enthesitis, is also seen in PsA. Most common sites include the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and ligamentous insertions around the pelvic bones.3 Nail changes that are typically seen in patients with psoriasis can be seen in PsA as well, including pitting, ridging, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis.3 Ocular inflammation which is classically seen with other spondyloarthropathies, can be seen in patients with PsA as well, frequently manifesting as conjunctivitis.2,3

Psoriatic arthritis is commonly classified under the broader category of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, given the low frequency of a positive rheumatoid factor.3 Currently, there are no laboratory tests that can help with a PsA diagnosis.3 Acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated, indicating active inflammation.

Radiographic data, such as X-rays of the hands and feet, can confirm the clinical distribution of joint involvement and show evidence of erosive changes. Further destructive changes include osteolysis (bone resorption) that may cause the classic pencil-in-cup deformity, typically seen in arthritis mutilans (Figure 1).3 Other radiographic evidence of PsA can include proliferative changes with new bone formation seen along the shaft of the metacarpal and metatarsal bones.3 Patients with axial involvement can have evidence of asymmetric sacroiliitis, which can be seen on radiographs. Asymmetric syndesmophytes, or bony outgrowths, can also be seen throughout the axial spine.3

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical presentation of a patient with the help of laboratory work and radiographs. Other forms of arthritis (such as rheumatoid arthritis, crystal arthropathies, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis) should be excluded. Given the varied presentation of PsA, classification criteria have been developed to assist in clinical research. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) have been developed and validated as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis and a source for clinical research (Table 1).7 Musculoskeletal pain in patients with psoriasis can be due to causes other than PsA, such as osteoarthritis and gout. A close working relationship in a combined rheumatology/dermatology clinic is vital to providing optimal diagnostic and treatment care for patients with psoriasis and PsA.8

The etiology of PsA is currently unknown, although many genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors have been identified that play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. In this setting, immunologically mediated processes that cause inflammation occur in the synovium of joints, enthesium, bone, and skin of patients with PsA.9 Studies have shown that activated T cells and T-cell–derived cytokines play an important role in cartilage degradation, joint damage, and stimulating bone resorption.9

One particular proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), has been the target for many treatment modalities for several years. With new and ongoing research into the PsA pathogenesis, other treatment options have been discovered, targeting different cytokines and T cells that are involved in the disease process. This has led to drug trials and recent FDA approvals of several new medications, which provide further options for clinicians in managing and treating PsA.

Management of Psoriasis

Choice of therapy is determined by the extent and severity of psoriasis (body surface area [BSA] involvement) as well as the patient’s comorbidities and preferences.4 Providers have a wide spectrum of effective therapies to prescribe, both topically and systemically. Topical therapy options include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 and analogs (calcipotriene), anthralin, tar, tazarotene (third-generation retinoid), and calcineurin inhibitors (tacromlimus).4 Phototherapy with or without saltwater baths helps improve skin lesions.

These treatments are beneficial for all patients with psoriasis, but the disease can be controlled with monotherapy in patients with mild-to-moderate disease (< 10% BSA). Limiting these treatment options are some long-term effects of the medications because of the potential for toxicity as well as decreasing efficacy of the medication over time.4 For patients with more BSA involvement (> 10%), systemic treatment options include methotrexate (MTX), systemic retinoids (acitretin), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine), and biologics. Many of these systemic treatment options overlap for patients with both psoriasis and PsA, and topical treatments can be used adjunctively to better control the skin disease.

Management of Psoriatic Arthritis

It is important to identify PsA and begin treatment early, because it has been shown that patients tend to fare better in their disease course if treated early.10 Once a diagnosis of PsA is made, disease activity needs to be determined by clinical examination and radiographs of joints. Scoring systems, by assessing bone erosions and deformities on joint radiographs, can aide with this assessment. Based on these, PsA can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. Several disease activity measures that have been developed for clinical trials in monitoring of disease activity can be used as an aide in the office setting. These tools are still being studied to determine the optimal measure of disease activity.

NSAIDs and Glucocorticoids

Controlling inflammation and providing pain relief are the primary treatment goals for patients with PsA. In mild, predominantly peripheral PsA, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used, but they do not halt disease progression. If the disease is controlled and not progressing, NSAIDs may be used as the only treatment. However, if symptoms persist and/or there is more joint involvement, the next level of therapy should be sought. Intra-articular corticosteroids for symptomatic relief can be given if only a few joints are affected. Oral corticosteroids can be used occasionally in patients with multiple joint aches, but they are typically avoided or tapered slowly to avoid worsening the patient’s skin psoriasis or having it evolve into a more severe form, such as pustular psoriasis.10 All these treatments can alleviate symptoms, but they do not prevent the progression of disease.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

For patients who fail NSAIDs or present initially with more joint involvement (polyarthritis or > 5 swollen joints), traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be started (Table 2). Methotrexate is one of the first-line DMARD prescriptions. It is commonly used because of its effectiveness in treating both skin and joint involvement, despite limited evidence of its efficacy in controlled clinical trials for slowing the progression of joint damage in PsA.2,9-11 Methotrexate can be given orally or subcutaneously (SC) every week. Routine laboratory monitoring is required given the known effects of MTX on liver and bone marrow suppression. Clinical monitoring is needed as well due to its well-known risk for pulmonary toxicity and teratogenicity.2

Leflunomide is another traditional oral DMARD that is administered daily. It has be shown to be effective in PsA, with only a modest effect in improving skin lesions.12 Laboratory monitoring is identical to that required with MTX. Adverse effects (AEs) include diarrhea and increased risk of elevated transaminases.9 Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is also used as a traditional DMARD and shown to have an effective clinical response in treating peripheral arthritis but not in axial or skin disease.9,12 Not all studies have shown effective responses to SSZ. The primary AE is gastrointestinal, making this a frequently discontinued medication.2 Cyclosporine is more commonly used in psoriasis but can be used on its own or with MTX for treating patients with PsA.10 It is often not tolerated well and frequently discontinued, due to major AEs, including hypertension and renal dysfunction.2,10

These traditional DMARDs are usually given for 3 to 6 months.13 After this initial period, the patient’s clinical response is reassessed, and the need for changing therapy to another DMARD or biologic is determined.

Biologic Therapies

With the discovery of TNFα as a potent cytokine in inflammatory arthritis came a new class of medications that has provided patients and providers with more effective treatment options. This category of medications is known as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis). Five medications have been developed that target TNFα, each in its own way: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certrolizumab pegol. These medications were initially studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with further clinical trials performed for treatment of PsA. Each is prescribed differently: Adalimumab and certrolizumab are given SC every 2 weeks, etanercept is given weekly, and golimumab is given once a month. Infliximab is the only medication prescribed as an infusion, which is administered every 8 weeks after receiving 3 loading doses.

Studies have shown that all TNFis are effective in treating PsA: improving joint disease activity, inhibiting progression of structural damage, and improving function and overall quality of life.10 The TNFi drugs also improve psoriasis along with dactylitis, enthesitis, and nail changes.13 Patients with

axial disease benefit from TNFi, but the evidence of TNFi effectiveness is extrapolated from studies in axial spondyloarthritis.13,14 Tumor necrosis

factor inhibitors can be used as monotherapy, although there is some evidence for using TNFi drugs with MTX in PsA. Combination therapy can potentially prolong the survival of the TNFi drug or prevent formation of antidrug antibodies.14,15

The current evidence for monotherapy vs combination therapy in patients with PsA is not consistent, and no formal guidelines have been developed to guide physicians one way or another. The TNFi drugs are generally well tolerated, although the patient needs to learn how to self-inject if given the SC route. Adverse effects include infusion or injection site reactions and infections. Prior to starting a TNFi, it is prudent to screen for latent tuberculosis infection as well as hepatitis B and C, given the risk of reactivation. Clinical response is monitored for 3 months, and if remission or low disease activity is not reached, a different TNFi may be tried.13 Importantly, patients receiving infliximab without clinical improvement in 3 months may have their dose and frequency increased before switching to an alternative TNFi. Some studies show that a trial of a second TNFi has a less potent response than with a first TNFi, and the drug survival is shorter in duration.13

One of the newest biologic agents approved for treating PsA is ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody (MAB) that inhibits receptor binding of cytokines interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23. These cytokines have been identified in patients with psoriasis and PsA as further promoting inflammation. Ustekinumab recently received approval for the treatment of PsA and is given SC every 12 weeks after 2 initial doses. Further studies have also confirmed ustekinumab significantly suppressed radiographic progression of joint damage in patients with active PsA.15 Notable AEs included infections, but there have been no cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infections reported.16

The most recent FDA-approved medication for PsA is apremilast. It is a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, which causes the suppression of other proinflammatory mediators and cytokines active in the immune system.10 It is given orally, uptitrating the doses over a few days until the twice-daily maintenance dosing is achieved. It is generally well tolerated with nausea and diarrhea as the most common AEs.17 Further studies need to be conducted to assess whether this agent is able to prevent or decrease joint damage.

Other potential treatment options are currently undergoing trials to assess their efficacy and safety in treating psoriasis and/or PsA. One class targets the IL-17 cytokine pathway and includes brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody (MAB) anti-IL-17 receptor, ixekizumab and secukinumab, both MABs anti-IL-17A. Secukinumab has already received FDA approval for the treatment of plaque psoriasis (2015). Other agents currently undergoing trials are abatacept (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-Ig), a recombinant human fusion protein that blocks the co-stimulation of T cells9 and tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor.18 Early studies show patients achieving a response with these medications, but further long-term studies are needed.19

Treatment Recommendations

Treatment approaches differ for patients with only psoriasis and patients with psoriasis and PsA, although some treatment modalities overlap. Recommendations for PsA have been set for each domain affected (Figure 2). The treatment approach is based on several factors, including severity or the degree of disease activity, any joint damage, and the patient’s comorbidities. Certain comorbidities are associated with PsA—cardiovascular disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, fatty liver disease, chronic viral infections (hepatitis B or C), and kidney disease. These comorbidities can affect the choice of therapy for the patient.20,21 Other factors affecting treatment choices include patient preference regarding mode and frequency of administration of the medication, potential AEs, requirements of laboratory monitoring or regular doctor visits, and the cost of medications.10,22

In treating patients with psoriasis and PsA, a multidisciplinary approach is needed. Because skin manifestations of psoriasis usually develop prior to arthritis symptoms in most patients, primary care providers and dermatologists can routinely screen patients for arthritis.10 Rheumatologists can confirm arthritis and musculoskeletal involvement, but the treatment and management of these patients will need to be in collaboration with a dermatologist. The goal of comanagement is to choose appropriate therapies that may be able to treat both the skin and musculoskeletal manifestations.

A multidisciplinary approach can also limit polypharmacy, control costs, and reduce AEs. The existence of VA combined rheumatology and dermatology clinics makes this an invaluable experience for the veteran with direct and focused patient management. In addition to controlling disease activity, the goal of treatment is to improve function and the patient’s quality of life, halting structural joint damage to prevent disability.10 Physical and occupational therapies play an important role in PsA management as does exercise. Patients should be educated about their disease and treatment options discussed. It is also important to identify and reduce significant comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, to decrease mortality and improve life expectancy.10

Conclusion

Psoriasis is a distinct disease entity but can occur along with extracutaneous features. Patients with psoriasis need to be screened for PsA, and it is important to diagnose PsA early to begin appropriate treatment. Disease activity, severity, and any joint damage will determine therapy. Over the past decade, new treatment options have become available that provide more choices for patients than those of the standard DMARDs. The TNFis have proven to be efficacious in treating psoriasis and PsA. With a better understanding of pathogenesis of these diseases, new medications have been discovered targeting different parts of the immune system involved in dysregulation and ultimately inflammation. Additional clinical research is needed to provide physicians with more effective ways of controlling these diseases. Ultimately, the management of PsA is not solely based on medications, but the authors’ VA experience highlights the importance of a multispecialty approach to the management of psoriasis and PsA.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Psoriasis is a commonly encountered systemic condition, usually presenting with chronic erythematous plaques with an overlying silvery white scale.1 Extracutaneous manifestations, such as joint or spine (axial) involvement, can occur along with this skin disorder. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, heterogeneous disorder characterized by inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriasis.2,3 Until recently treatment of PsA has been limited to a few medications.

Continuing investigations into the pathogenesis of PsA have revealed new treatment options, targeting molecules at the cellular level. Over the past few years, additional medications have been approved, giving providers more options in treating patients with psoriasis and PsA. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach by both rheumatologists and dermatologists in evaluating and managing patients at VA clinics has helped optimize care of these patients by providing timely evaluation and treatment at the same visit.

Psoriasis Presentation and Diagnosis

Genetic predisposition and certain environmental factors (trauma, infection, medications) are known to trigger psoriasis, which can present in many forms.4 Chronic plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common skin pattern with a classic presentation of sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale.4 It affects the scalp, lower back, umbilicus, genitals, and extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees. Guttate psoriasis is recognized by its multiple small papules and plaques in a droplike pattern. Pustular psoriasis usually presents with widespread pustules. On the other hand, erythrodermic psoriasis manifests as diffuse erythema involving multiple skin areas.4 Erythematous psoriatic plaques, which are predominantly in the intertriginous areas or skin folds (inguinal, perineal, genital, intergluteal, axillary, or inframammary), are known as inverse psoriasis.

A psoriasis diagnosis is made by taking a history and a physical examination. Rarely, a skin biopsy of the lesions will be required for an atypical presentation. The course of the disease is unpredictable, variable, and dependent on the type of psoriasis. Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic condition, whereas guttate psoriasis is often self-limited.4 A poorer prognosis is seen in patients with erythrodermic and generalized pustular psoriasis.4

Psoriatic Arthritis Presentation, Classification, and Diagnosis

Prevalence of PsA is not known, but it is estimated to be from 0.3% to 1% of the U.S. population. In the psoriasis population, PsA is reported to range from 7% to 42%,3 although more recently, these numbers have been found to be in the 15% to 25% range (unpublished observations). This type of inflammatory arthritis can develop at any age but usually is seen between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with men being affected equally or a little more than are women.3 Clinical symptoms usually include pain and stiffness of affected joints, > 30 minutes of morning stiffness, and fatigue.

The presentation of joint involvement can vary widely. Five subtypes of arthritis were identified by Moll and Wright in 1973, which included arthritis with predominant distal interphalangeal involvement, arthritis mutilans, symmetric polyarthritis (> 5 joints), asymmetric oligoarthritis (1-4 joints), and predominant spondylitis (axial).5 Patients with PsA may also have evidence of spondylitis (inflammation of vertebra) or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) with back pain > 3 months, hip or buttock pain, nighttime pain, or pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest.6 The cervical spine is more frequently involved than is the lumbar spine in patients with PsA.3

Psoriatic arthritis can have a diverse presentation not only with the affected joints, but also involving nails, tendons, and ligaments. An entire digit of the hand or foot can become swollen, known as dactylitis, or “sausage digit.” Inflammation at the insertion of tendons or ligaments, known as enthesitis, is also seen in PsA. Most common sites include the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and ligamentous insertions around the pelvic bones.3 Nail changes that are typically seen in patients with psoriasis can be seen in PsA as well, including pitting, ridging, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis.3 Ocular inflammation which is classically seen with other spondyloarthropathies, can be seen in patients with PsA as well, frequently manifesting as conjunctivitis.2,3

Psoriatic arthritis is commonly classified under the broader category of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, given the low frequency of a positive rheumatoid factor.3 Currently, there are no laboratory tests that can help with a PsA diagnosis.3 Acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated, indicating active inflammation.

Radiographic data, such as X-rays of the hands and feet, can confirm the clinical distribution of joint involvement and show evidence of erosive changes. Further destructive changes include osteolysis (bone resorption) that may cause the classic pencil-in-cup deformity, typically seen in arthritis mutilans (Figure 1).3 Other radiographic evidence of PsA can include proliferative changes with new bone formation seen along the shaft of the metacarpal and metatarsal bones.3 Patients with axial involvement can have evidence of asymmetric sacroiliitis, which can be seen on radiographs. Asymmetric syndesmophytes, or bony outgrowths, can also be seen throughout the axial spine.3

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical presentation of a patient with the help of laboratory work and radiographs. Other forms of arthritis (such as rheumatoid arthritis, crystal arthropathies, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis) should be excluded. Given the varied presentation of PsA, classification criteria have been developed to assist in clinical research. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) have been developed and validated as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis and a source for clinical research (Table 1).7 Musculoskeletal pain in patients with psoriasis can be due to causes other than PsA, such as osteoarthritis and gout. A close working relationship in a combined rheumatology/dermatology clinic is vital to providing optimal diagnostic and treatment care for patients with psoriasis and PsA.8

The etiology of PsA is currently unknown, although many genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors have been identified that play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. In this setting, immunologically mediated processes that cause inflammation occur in the synovium of joints, enthesium, bone, and skin of patients with PsA.9 Studies have shown that activated T cells and T-cell–derived cytokines play an important role in cartilage degradation, joint damage, and stimulating bone resorption.9

One particular proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), has been the target for many treatment modalities for several years. With new and ongoing research into the PsA pathogenesis, other treatment options have been discovered, targeting different cytokines and T cells that are involved in the disease process. This has led to drug trials and recent FDA approvals of several new medications, which provide further options for clinicians in managing and treating PsA.

Management of Psoriasis

Choice of therapy is determined by the extent and severity of psoriasis (body surface area [BSA] involvement) as well as the patient’s comorbidities and preferences.4 Providers have a wide spectrum of effective therapies to prescribe, both topically and systemically. Topical therapy options include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 and analogs (calcipotriene), anthralin, tar, tazarotene (third-generation retinoid), and calcineurin inhibitors (tacromlimus).4 Phototherapy with or without saltwater baths helps improve skin lesions.

These treatments are beneficial for all patients with psoriasis, but the disease can be controlled with monotherapy in patients with mild-to-moderate disease (< 10% BSA). Limiting these treatment options are some long-term effects of the medications because of the potential for toxicity as well as decreasing efficacy of the medication over time.4 For patients with more BSA involvement (> 10%), systemic treatment options include methotrexate (MTX), systemic retinoids (acitretin), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine), and biologics. Many of these systemic treatment options overlap for patients with both psoriasis and PsA, and topical treatments can be used adjunctively to better control the skin disease.

Management of Psoriatic Arthritis

It is important to identify PsA and begin treatment early, because it has been shown that patients tend to fare better in their disease course if treated early.10 Once a diagnosis of PsA is made, disease activity needs to be determined by clinical examination and radiographs of joints. Scoring systems, by assessing bone erosions and deformities on joint radiographs, can aide with this assessment. Based on these, PsA can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. Several disease activity measures that have been developed for clinical trials in monitoring of disease activity can be used as an aide in the office setting. These tools are still being studied to determine the optimal measure of disease activity.

NSAIDs and Glucocorticoids

Controlling inflammation and providing pain relief are the primary treatment goals for patients with PsA. In mild, predominantly peripheral PsA, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used, but they do not halt disease progression. If the disease is controlled and not progressing, NSAIDs may be used as the only treatment. However, if symptoms persist and/or there is more joint involvement, the next level of therapy should be sought. Intra-articular corticosteroids for symptomatic relief can be given if only a few joints are affected. Oral corticosteroids can be used occasionally in patients with multiple joint aches, but they are typically avoided or tapered slowly to avoid worsening the patient’s skin psoriasis or having it evolve into a more severe form, such as pustular psoriasis.10 All these treatments can alleviate symptoms, but they do not prevent the progression of disease.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

For patients who fail NSAIDs or present initially with more joint involvement (polyarthritis or > 5 swollen joints), traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be started (Table 2). Methotrexate is one of the first-line DMARD prescriptions. It is commonly used because of its effectiveness in treating both skin and joint involvement, despite limited evidence of its efficacy in controlled clinical trials for slowing the progression of joint damage in PsA.2,9-11 Methotrexate can be given orally or subcutaneously (SC) every week. Routine laboratory monitoring is required given the known effects of MTX on liver and bone marrow suppression. Clinical monitoring is needed as well due to its well-known risk for pulmonary toxicity and teratogenicity.2

Leflunomide is another traditional oral DMARD that is administered daily. It has be shown to be effective in PsA, with only a modest effect in improving skin lesions.12 Laboratory monitoring is identical to that required with MTX. Adverse effects (AEs) include diarrhea and increased risk of elevated transaminases.9 Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is also used as a traditional DMARD and shown to have an effective clinical response in treating peripheral arthritis but not in axial or skin disease.9,12 Not all studies have shown effective responses to SSZ. The primary AE is gastrointestinal, making this a frequently discontinued medication.2 Cyclosporine is more commonly used in psoriasis but can be used on its own or with MTX for treating patients with PsA.10 It is often not tolerated well and frequently discontinued, due to major AEs, including hypertension and renal dysfunction.2,10

These traditional DMARDs are usually given for 3 to 6 months.13 After this initial period, the patient’s clinical response is reassessed, and the need for changing therapy to another DMARD or biologic is determined.

Biologic Therapies

With the discovery of TNFα as a potent cytokine in inflammatory arthritis came a new class of medications that has provided patients and providers with more effective treatment options. This category of medications is known as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis). Five medications have been developed that target TNFα, each in its own way: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certrolizumab pegol. These medications were initially studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with further clinical trials performed for treatment of PsA. Each is prescribed differently: Adalimumab and certrolizumab are given SC every 2 weeks, etanercept is given weekly, and golimumab is given once a month. Infliximab is the only medication prescribed as an infusion, which is administered every 8 weeks after receiving 3 loading doses.

Studies have shown that all TNFis are effective in treating PsA: improving joint disease activity, inhibiting progression of structural damage, and improving function and overall quality of life.10 The TNFi drugs also improve psoriasis along with dactylitis, enthesitis, and nail changes.13 Patients with

axial disease benefit from TNFi, but the evidence of TNFi effectiveness is extrapolated from studies in axial spondyloarthritis.13,14 Tumor necrosis

factor inhibitors can be used as monotherapy, although there is some evidence for using TNFi drugs with MTX in PsA. Combination therapy can potentially prolong the survival of the TNFi drug or prevent formation of antidrug antibodies.14,15