User login

Skin of Color in Preclinical Medical Education: A Cross-Institutional Comparison and A Call to Action

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods

Participants—Three US medical schools, a blend of private and public medical schools located across different geographic boundaries, agreed to participate in the study. All 3 institutions were current members of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium, whose primary goal is to create the medical school of the future and transform physician training.18 All 32 member institutions of the AMA consortium were contacted to request their participation in the study. As part of the consortium, these institutions have vowed to collectively work to develop and share the best models for educational advancement to improve care for patients, populations, and communities18 and would expectedly provide a more racially and ethnically inclusive curriculum than an institution not accountable to a group dedicated to identifying the best ways to deliver care for increasingly diverse communities.

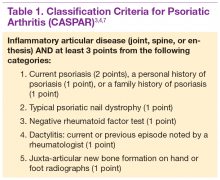

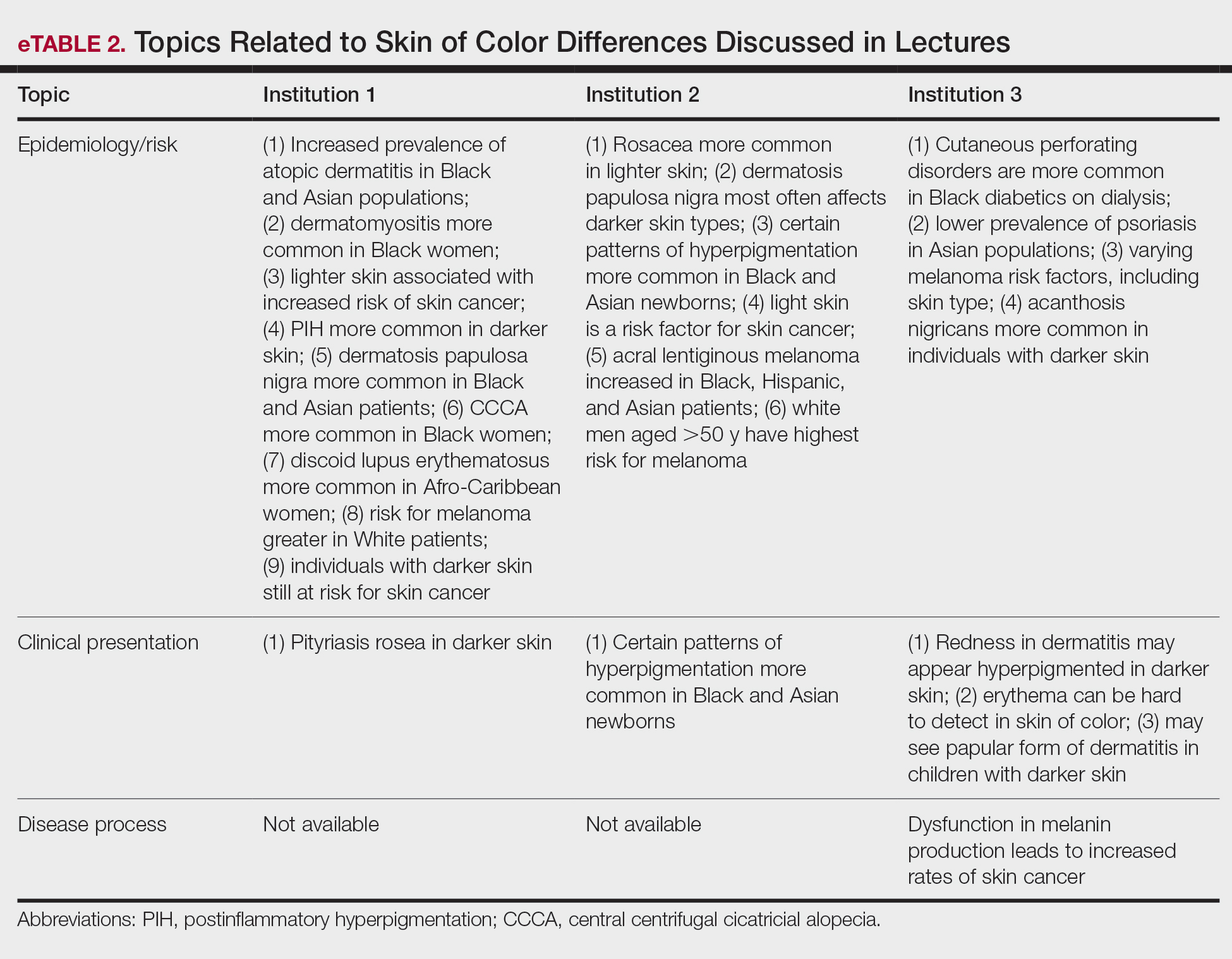

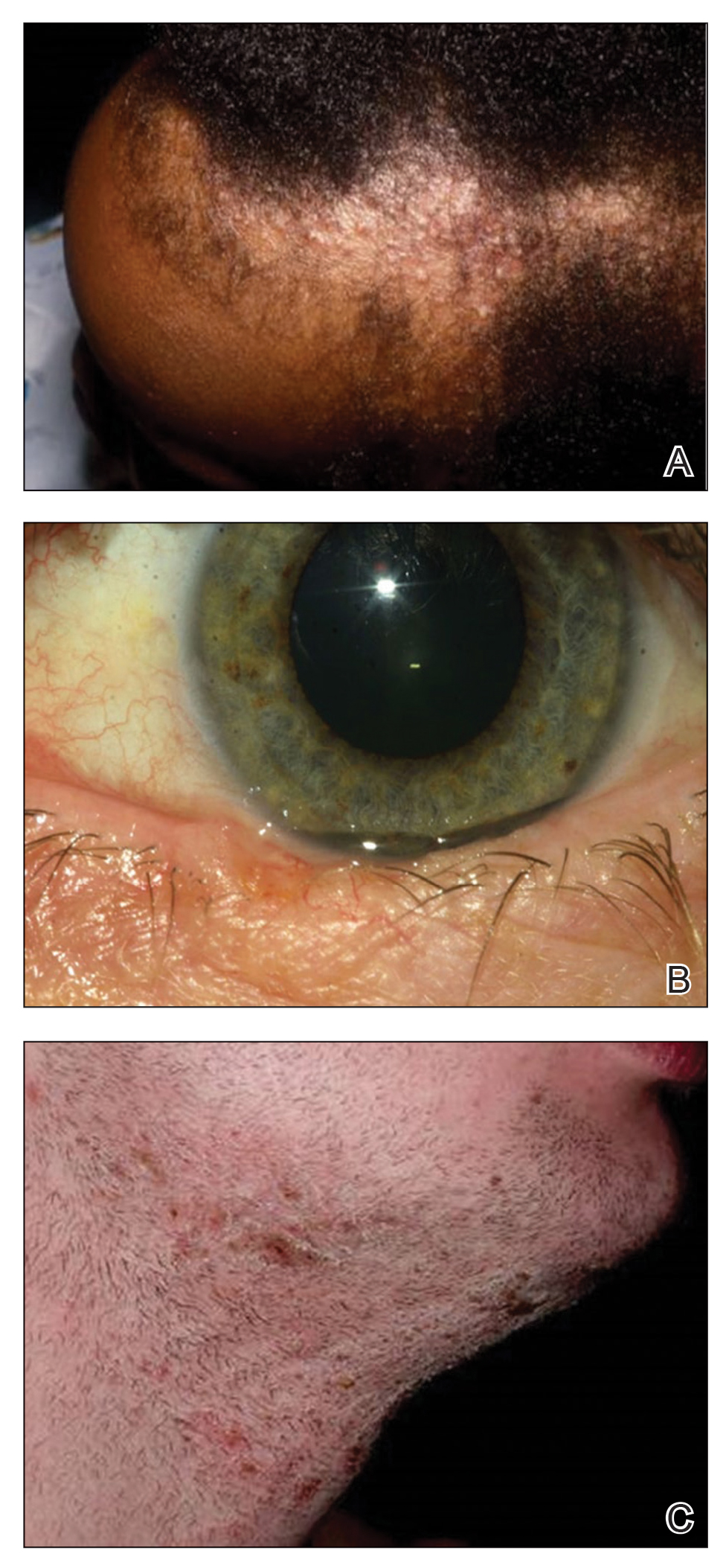

Data Collection—Lectures were included if they were presented during dermatology preclinical courses in the 2015 to 2016 academic year. An uninvolved third party removed the names and identities of instructors to preserve anonymity. Two independent coders from different institutions extracted the data—lecture title, total number of clinical and histologic images, and number of skin of color images—from each of the anonymized lectures using a standardized coding form. We documented differences in skin of color noted in lectures and the disease context for the discussed differences, such as variations in clinical presentation, disease process, epidemiology/risk, and treatment between different skin phenotypes or ethnic groups. Photographs in which the coders were unable to differentiate whether the patient had skin of color were designated as indeterminate or unclear. Photographs appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI19 were categorically designated as skin of color, and those appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were described as not skin of color; however, images appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin type III often were classified as not skin of color or indeterminate and occasionally skin of color. The Figure shows examples of images classified as skin of color, indeterminate, and not skin of color. Photographs often were classified as indeterminate due to poor lighting, close-up view photographs, or highlighted pathology obscuring the surrounding skin. We excluded duplicate photographs and histologic images from the analyses.

We also reviewed 19 conditions previously highlighted by the SOCS as areas of importance to skin of color patients.20 The coders tracked how many of these conditions were noted in each lecture. Duplicate discussion of these conditions was not included in the analyses. Any discrepancies between coders were resolved through additional slide review and discussion. The final coded data with the agreed upon changes were used for statistical analyses. Recent national demographic data from the US Census Bureau in 2019 describe approximately 39.9% of the population as belonging to racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic/Latinx White.21 Consequently, the standard for adequate representation for skin of color photographs was set at 35% for the purpose of this study.

Results

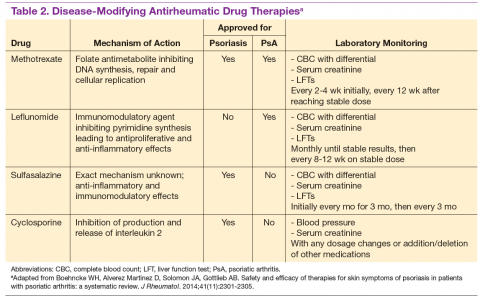

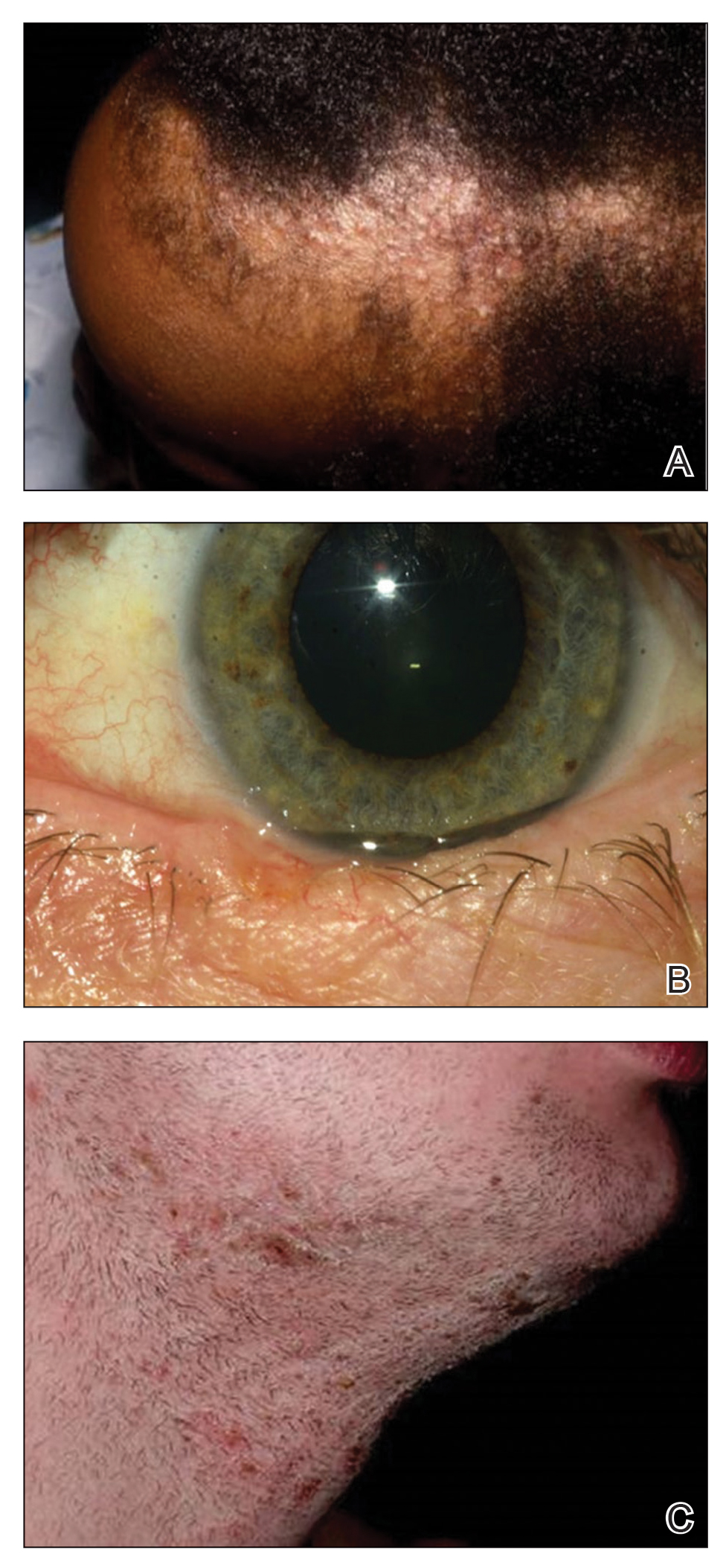

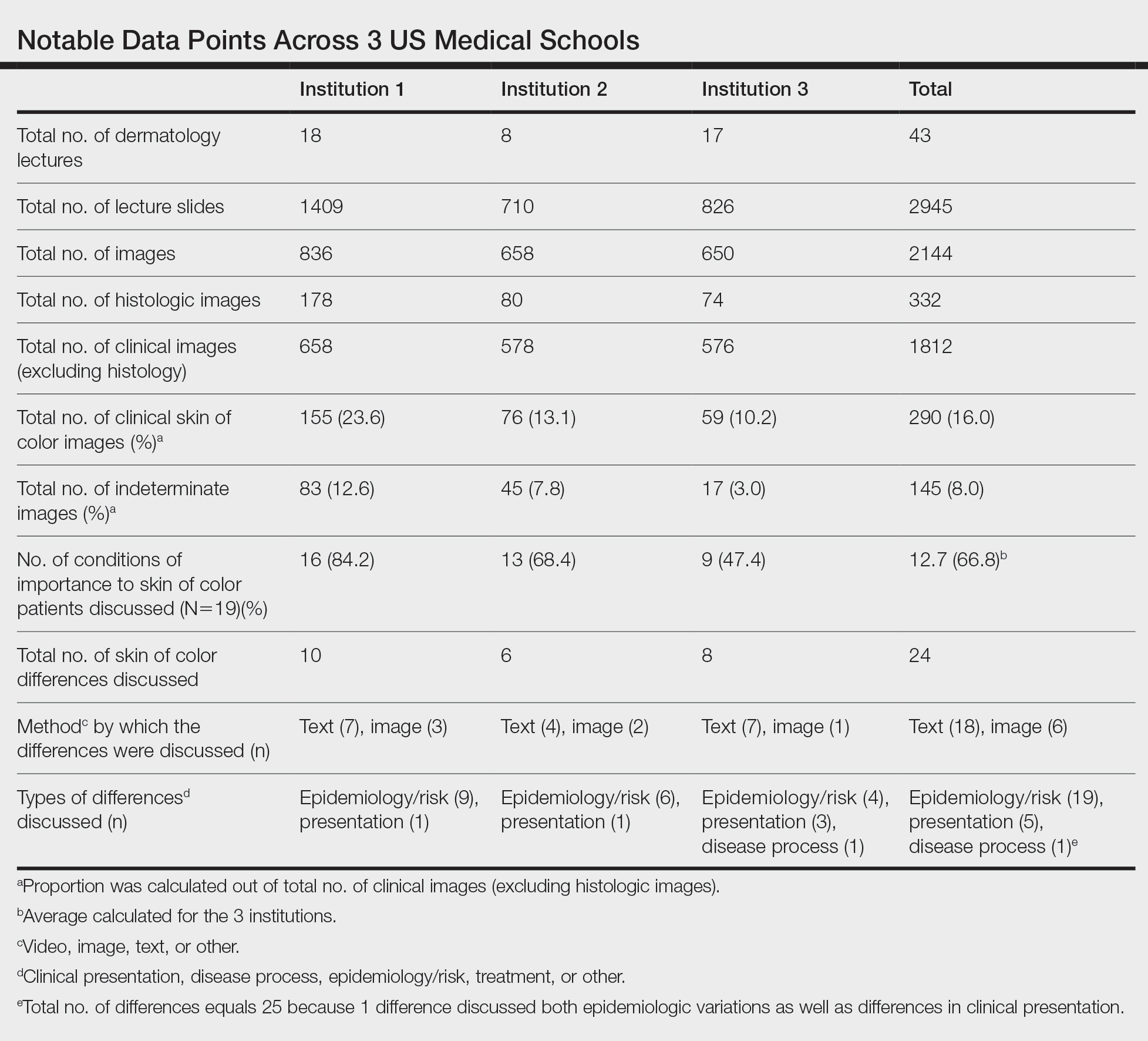

Across all 3 institutions included in the study, the proportion of the total number of clinical photographs showing skin of color was 16% (290/1812). Eight percent of the total photographs (145/1812) were noted to be indeterminate (Table). For institution 1, 23.6% of photographs (155/658) showed skin of color, and 12.6% (83/658) were indeterminate. For institution 2, 13.1% (76/578) showed skin of color and 7.8% (45/578) were indeterminate. For institution 3, 10.2% (59/576) showed skin of color and 3% (17/576) were indeterminate.

Institutions 1, 2, and 3 had 18, 8, and 17 total dermatology lectures, respectively. Of the 19 conditions designated as areas of importance to skin of color patients by the SOCS, 16 (84.2%) were discussed by institution 1, 11 (57.9%) by institution 2, and 9 (47.4%) by institution 3 (eTable 1). Institution 3 did not include photographs of skin of color patients in its acne, psoriasis, or cutaneous malignancy lectures. Institution 1 also did not include any skin of color patients in its malignancy lecture. Lectures that focused on pigmentary disorders, atopic dermatitis, infectious conditions, and benign cutaneous neoplasms were more likely to display photographs of skin of color patients; for example, lectures that discussed infectious conditions, such as superficial mycoses, herpes viruses, human papillomavirus, syphilis, and atypical mycobacterial infections, were consistently among those with higher proportions of photographs of skin of color patients.

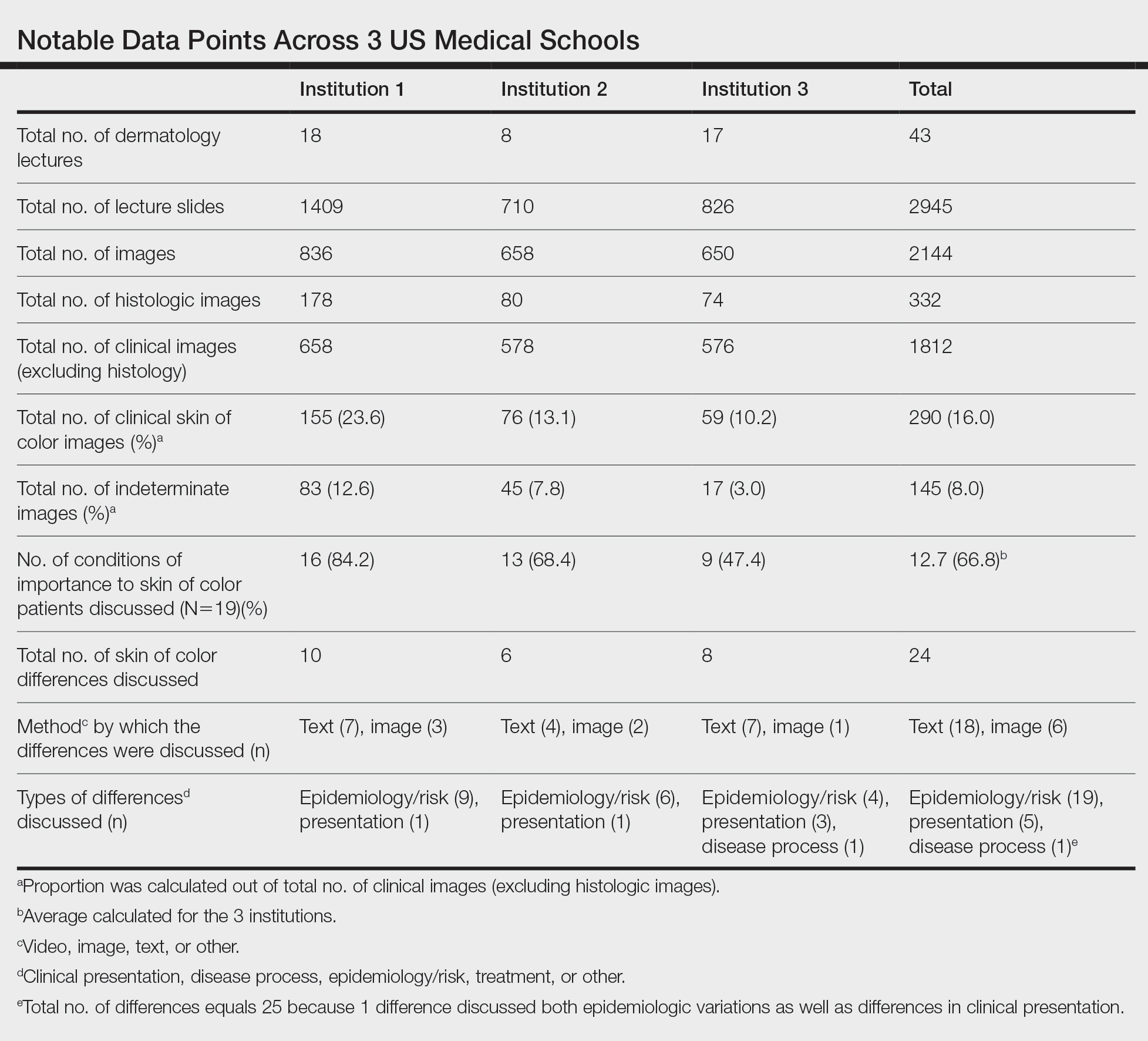

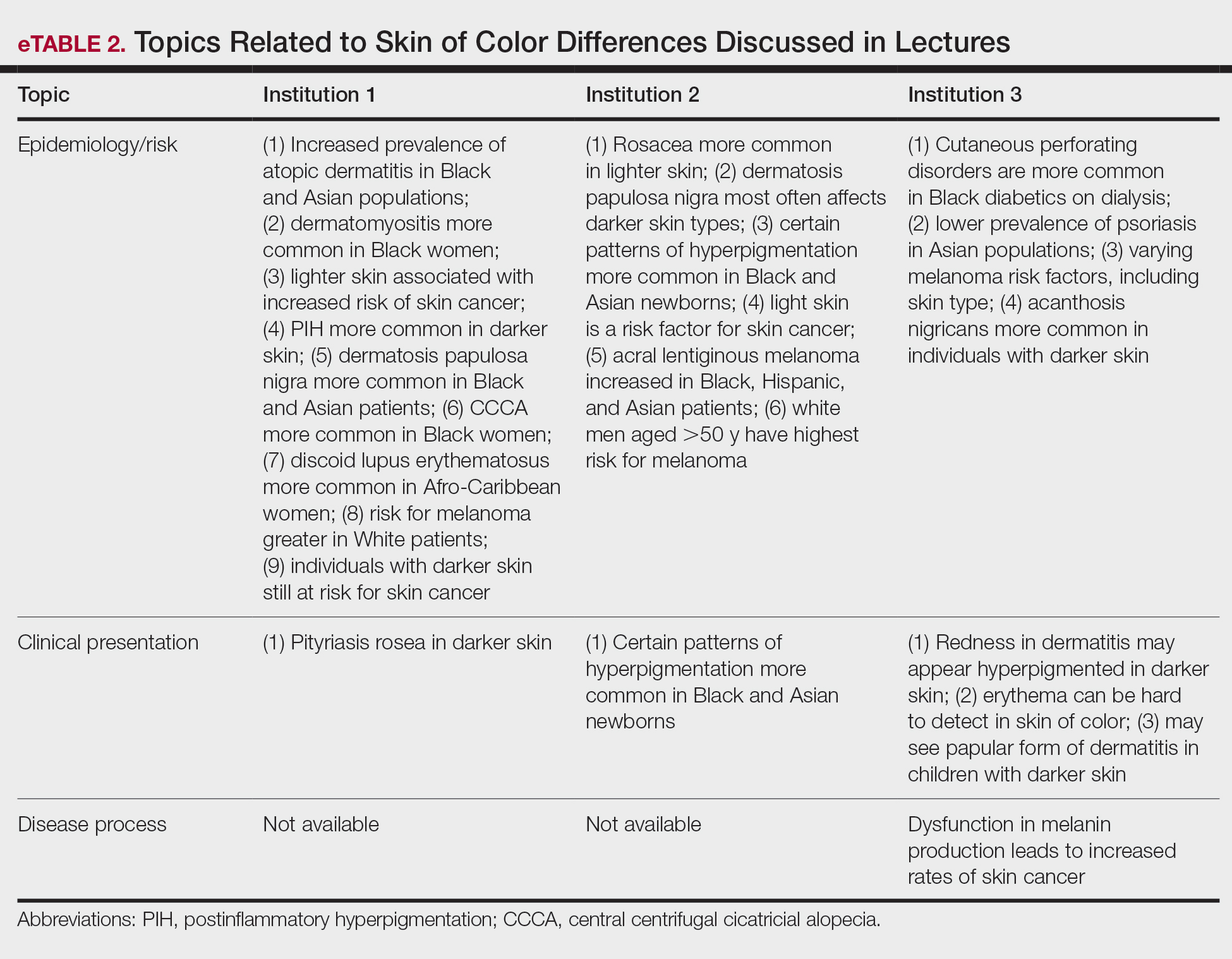

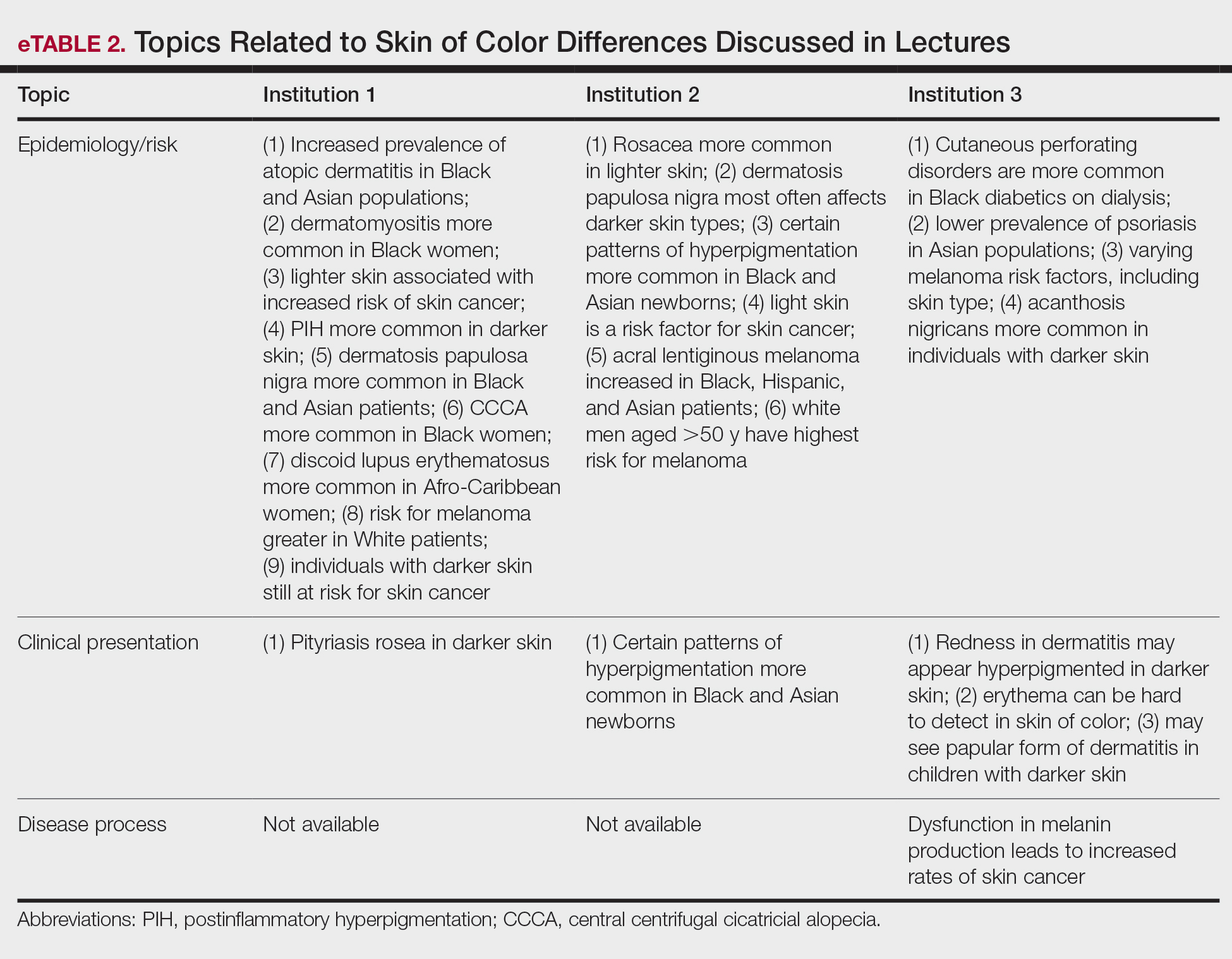

Throughout the entire preclinical dermatology course at all 3 institutions, of 2945 lecture slides, only 24 (0.8%) unique differences were noted between skin color and non–skin of color patients, with 10 total differences noted by institution 1, 6 by institution 2, and 8 by institution 3 (Table). The majority of these differences (19/24) were related to epidemiologic differences in prevalence among varying racial/ethnic groups, with only 5 instances highlighting differences in clinical presentation. There was only a single instance that elaborated on the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of the discussed difference. Of all 24 unique differences discussed, 8 were related to skin cancer, 3 were related to dermatitis, and 2 were related to the difference in manifestation of erythema in patients with darker skin (eTable 2).

Comment

The results of this study demonstrated that skin of color is underrepresented in the preclinical dermatology curriculum at these 3 institutions. Although only 16% of all included clinical photographs were of skin of color, individuals with skin of color will soon represent more than half of the total US population within the next 2 decades.1 To increase representation of skin of color patients, teaching faculty should consciously and deliberately include more photographs of skin of color patients for a wider variety of common conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, in addition to those that tend to disparately affect skin of color patients, such as pseudofolliculitis barbae or melasma. Furthermore, they also can incorporate more detailed discussions about important differences seen in skin of color patients.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Psoriasis Lectures—At institution 3, there were no skin of color patients included in the psoriasis lecture, even though there is considerable data in the literature indicating notable differences in the clinical presentation, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in skin of color patients.11,22 There are multiple nuances in psoriasis manifestation in patients with skin of color, including less-conspicuous erythema in darker skin, higher degrees of dyspigmentation, and greater body surface area involvement. For Black patients with scalp psoriasis, the impact of hair texture, styling practices, and washing frequency are additional considerations that may impact disease severity and selection of topical therapy.11 The lack of inclusion of any skin of color patients in the psoriasis lecture at one institution further underscores the pressing need to prioritize communities of color in medical education.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Cutaneous Malignancy Lectures—Similarly, while a lecturer at institution 2 noted that acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a considerable proportion of melanoma among skin of color patients,23 there was no mention of how melanoma generally is substantially more deadly in this population, potentially due to decreased awareness and inconsistent screening.24 Furthermore, at institutions 1 and 3, there were no photographs or discussion of skin of color patients during the cutaneous malignancy lectures. Evidence shows that more emphasis is needed for melanoma screening and awareness in skin of color populations to improve survival outcomes,24 and this begins with educating not only future dermatologists but all future physicians as well. The failure to include photographs of skin of color patients in discussions or lectures regarding cutaneous malignancies may serve to further perpetuate the harmful misperception that individuals with skin of color are unaffected by skin cancer.25,26

Analysis of Skin of Color Photographs in Infectious Disease Lectures—In addition, lectures discussing infectious etiologies were among those with the highest proportion of skin of color photographs. This relatively disproportionate representation of skin of color compared to the other lectures may contribute to the development of harmful stereotypes or the stigmatization of skin of color patients. Although skin of color should continue to be represented in similar lectures, teaching faculty should remain mindful of the potential unintended impact from lectures including relatively disproportionate amounts of skin of color, particularly when other lectures may have sparse to absent representation of skin of color.

More Photographs Available for Education—Overall, our findings may help to inform changes to preclinical dermatology medical education at other institutions to create more inclusive and representative curricula for skin of color patients. The ability of instructors to provide visual representation of various dermatologic conditions may be limited by the photographs available in certain textbooks with few examples of patients with skin of color; however, concerns regarding the lack of skin of color representation in dermatology training is not a novel discussion.17 Although it is the responsibility of all dermatologists to advocate for the inclusion of skin of color, many dermatologists of color have been leading the way in this movement for decades, publishing several textbooks to document various skin conditions in those with darker skin types and discuss unique considerations for patients with skin of color.27-29 Images from these textbooks can be utilized by programs to increase representation of skin of color in dermatology training. There also are multiple expanding online dermatologic databases, such as VisualDx, with an increasing focus on skin of color patients, some of which allow users to filter images by degree of skin pigmentation.30 Moreover, instructors also can work to diversify their curricula by highlighting more of the SOCS conditions of importance to skin of color patients, which have since been renamed and highlighted on the Patient Dermatology Education section of the SOCS website.20 These conditions, while not completely comprehensive, provide a useful starting point for medical educators to reevaluate for potential areas of improvement and inclusion.

There are several potential strategies that can be used to better represent skin of color in dermatologic preclinical medical education, including increasing awareness, especially among dermatology teaching faculty, of existing disparities in the representation of skin of color in the preclinical curricula. Additionally, all dermatology teaching materials could be reviewed at the department level prior to being disseminated to medical students to assess for instances in which skin of color could be prioritized for discussion or varying disease presentations in skin of color could be demonstrated. Finally, teaching faculty may consider photographing more clinical images of their skin of color patients to further develop a catalog of diverse images that can be used to teach students.

Study Limitations—Our study was unable to account for verbal discussion of skin of color not otherwise denoted or captured in lecture slides. Additional limitations include the utilization of Fitzpatrick skin types to describe and differentiate varying skin tones, as the Fitzpatrick scale originally was developed as a method to describe an individual’s response to UV exposure.19 The inability to further delineate the representation of darker skin types, such as those that may be classified as Fitzpatrick skin types V or VI,19 compared to those with lighter skin of color also was a limiting factor. This study was unable to assess for discussion of other common conditions affecting skin of color patients that were not listed as one of the priority conditions by SOCS. Photographs that were designated as indeterminate were difficult to elucidate as skin of color; however, it is possible that instructors may have verbally described these images as skin of color during lectures. Nonetheless, it may be beneficial for learners if teaching faculty were to clearly label instances where skin of color patients are shown or when notable differences are present.

Conclusion

Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of audio data from lectures, syllabi, and small group teaching materials from preclinical courses to more accurately assess representation of skin of color in dermatology training. Additionally, future studies also may expand to include images from lectures of overlapping clinical specialties, particularly infectious disease and rheumatology, to provide a broader assessment of skin of color exposure. Furthermore, repeat assessment may be beneficial to assess the longitudinal effectiveness of curricular changes at the institutions included in this study, comparing older lectures to more recent, updated lectures. This study also may be replicated at other medical schools to allow for wider comparison of curricula.

Acknowledgment—The authors wish to thank the institutions that offered and agreed to participate in this study with the hopes of improving medical education.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Published March 2015. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Learn more about SOCS. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed September 14, 2021. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(suppl 2):S41-S62.

- Berardesca E, Maibach H. Ethnic skin: overview of structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S139-S142.

- Callender VD, Surin-Lord SS, Davis EC, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Grimes PE, Stockton T. Pigmentary disorders in blacks. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:271-281.

- Halder RM, Nootheti PK. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S143-S148.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin: special considerations for therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:184-195.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Ramsay DL, Mayer F. National survey of undergraduate dermatologic medical education. Arch Dermatol.1985;121:1529-1530.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii.

- Knable A, Hood AF, Pearson TG. Undergraduate medical education in dermatology: report from the AAD Interdisciplinary Education Committee, Subcommittee on Undergraduate Medical Education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:467-470.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16-19.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Skin of Color Society. Patient dermatology education. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/patient-dermatology-education

- QuickFacts: United States. US Census Bureau website. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Pipitone M, Robinson JK, Camara C, et al. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: a Hispanic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:118-123.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Taylor SSC, Serrano AMA, Kelly AP, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Dadzie OE, Petit A, Alexis AF, eds. Ethnic Dermatology: Principles and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG, eds. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Springer; 2014.

- VisualDx. New VisualDx feature: skin of color sort. Published October 14, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.visualdx.com/blog/new-visualdx-feature-skin-of-color-sort/

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods

Participants—Three US medical schools, a blend of private and public medical schools located across different geographic boundaries, agreed to participate in the study. All 3 institutions were current members of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium, whose primary goal is to create the medical school of the future and transform physician training.18 All 32 member institutions of the AMA consortium were contacted to request their participation in the study. As part of the consortium, these institutions have vowed to collectively work to develop and share the best models for educational advancement to improve care for patients, populations, and communities18 and would expectedly provide a more racially and ethnically inclusive curriculum than an institution not accountable to a group dedicated to identifying the best ways to deliver care for increasingly diverse communities.

Data Collection—Lectures were included if they were presented during dermatology preclinical courses in the 2015 to 2016 academic year. An uninvolved third party removed the names and identities of instructors to preserve anonymity. Two independent coders from different institutions extracted the data—lecture title, total number of clinical and histologic images, and number of skin of color images—from each of the anonymized lectures using a standardized coding form. We documented differences in skin of color noted in lectures and the disease context for the discussed differences, such as variations in clinical presentation, disease process, epidemiology/risk, and treatment between different skin phenotypes or ethnic groups. Photographs in which the coders were unable to differentiate whether the patient had skin of color were designated as indeterminate or unclear. Photographs appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI19 were categorically designated as skin of color, and those appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were described as not skin of color; however, images appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin type III often were classified as not skin of color or indeterminate and occasionally skin of color. The Figure shows examples of images classified as skin of color, indeterminate, and not skin of color. Photographs often were classified as indeterminate due to poor lighting, close-up view photographs, or highlighted pathology obscuring the surrounding skin. We excluded duplicate photographs and histologic images from the analyses.

We also reviewed 19 conditions previously highlighted by the SOCS as areas of importance to skin of color patients.20 The coders tracked how many of these conditions were noted in each lecture. Duplicate discussion of these conditions was not included in the analyses. Any discrepancies between coders were resolved through additional slide review and discussion. The final coded data with the agreed upon changes were used for statistical analyses. Recent national demographic data from the US Census Bureau in 2019 describe approximately 39.9% of the population as belonging to racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic/Latinx White.21 Consequently, the standard for adequate representation for skin of color photographs was set at 35% for the purpose of this study.

Results

Across all 3 institutions included in the study, the proportion of the total number of clinical photographs showing skin of color was 16% (290/1812). Eight percent of the total photographs (145/1812) were noted to be indeterminate (Table). For institution 1, 23.6% of photographs (155/658) showed skin of color, and 12.6% (83/658) were indeterminate. For institution 2, 13.1% (76/578) showed skin of color and 7.8% (45/578) were indeterminate. For institution 3, 10.2% (59/576) showed skin of color and 3% (17/576) were indeterminate.

Institutions 1, 2, and 3 had 18, 8, and 17 total dermatology lectures, respectively. Of the 19 conditions designated as areas of importance to skin of color patients by the SOCS, 16 (84.2%) were discussed by institution 1, 11 (57.9%) by institution 2, and 9 (47.4%) by institution 3 (eTable 1). Institution 3 did not include photographs of skin of color patients in its acne, psoriasis, or cutaneous malignancy lectures. Institution 1 also did not include any skin of color patients in its malignancy lecture. Lectures that focused on pigmentary disorders, atopic dermatitis, infectious conditions, and benign cutaneous neoplasms were more likely to display photographs of skin of color patients; for example, lectures that discussed infectious conditions, such as superficial mycoses, herpes viruses, human papillomavirus, syphilis, and atypical mycobacterial infections, were consistently among those with higher proportions of photographs of skin of color patients.

Throughout the entire preclinical dermatology course at all 3 institutions, of 2945 lecture slides, only 24 (0.8%) unique differences were noted between skin color and non–skin of color patients, with 10 total differences noted by institution 1, 6 by institution 2, and 8 by institution 3 (Table). The majority of these differences (19/24) were related to epidemiologic differences in prevalence among varying racial/ethnic groups, with only 5 instances highlighting differences in clinical presentation. There was only a single instance that elaborated on the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of the discussed difference. Of all 24 unique differences discussed, 8 were related to skin cancer, 3 were related to dermatitis, and 2 were related to the difference in manifestation of erythema in patients with darker skin (eTable 2).

Comment

The results of this study demonstrated that skin of color is underrepresented in the preclinical dermatology curriculum at these 3 institutions. Although only 16% of all included clinical photographs were of skin of color, individuals with skin of color will soon represent more than half of the total US population within the next 2 decades.1 To increase representation of skin of color patients, teaching faculty should consciously and deliberately include more photographs of skin of color patients for a wider variety of common conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, in addition to those that tend to disparately affect skin of color patients, such as pseudofolliculitis barbae or melasma. Furthermore, they also can incorporate more detailed discussions about important differences seen in skin of color patients.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Psoriasis Lectures—At institution 3, there were no skin of color patients included in the psoriasis lecture, even though there is considerable data in the literature indicating notable differences in the clinical presentation, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in skin of color patients.11,22 There are multiple nuances in psoriasis manifestation in patients with skin of color, including less-conspicuous erythema in darker skin, higher degrees of dyspigmentation, and greater body surface area involvement. For Black patients with scalp psoriasis, the impact of hair texture, styling practices, and washing frequency are additional considerations that may impact disease severity and selection of topical therapy.11 The lack of inclusion of any skin of color patients in the psoriasis lecture at one institution further underscores the pressing need to prioritize communities of color in medical education.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Cutaneous Malignancy Lectures—Similarly, while a lecturer at institution 2 noted that acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a considerable proportion of melanoma among skin of color patients,23 there was no mention of how melanoma generally is substantially more deadly in this population, potentially due to decreased awareness and inconsistent screening.24 Furthermore, at institutions 1 and 3, there were no photographs or discussion of skin of color patients during the cutaneous malignancy lectures. Evidence shows that more emphasis is needed for melanoma screening and awareness in skin of color populations to improve survival outcomes,24 and this begins with educating not only future dermatologists but all future physicians as well. The failure to include photographs of skin of color patients in discussions or lectures regarding cutaneous malignancies may serve to further perpetuate the harmful misperception that individuals with skin of color are unaffected by skin cancer.25,26

Analysis of Skin of Color Photographs in Infectious Disease Lectures—In addition, lectures discussing infectious etiologies were among those with the highest proportion of skin of color photographs. This relatively disproportionate representation of skin of color compared to the other lectures may contribute to the development of harmful stereotypes or the stigmatization of skin of color patients. Although skin of color should continue to be represented in similar lectures, teaching faculty should remain mindful of the potential unintended impact from lectures including relatively disproportionate amounts of skin of color, particularly when other lectures may have sparse to absent representation of skin of color.

More Photographs Available for Education—Overall, our findings may help to inform changes to preclinical dermatology medical education at other institutions to create more inclusive and representative curricula for skin of color patients. The ability of instructors to provide visual representation of various dermatologic conditions may be limited by the photographs available in certain textbooks with few examples of patients with skin of color; however, concerns regarding the lack of skin of color representation in dermatology training is not a novel discussion.17 Although it is the responsibility of all dermatologists to advocate for the inclusion of skin of color, many dermatologists of color have been leading the way in this movement for decades, publishing several textbooks to document various skin conditions in those with darker skin types and discuss unique considerations for patients with skin of color.27-29 Images from these textbooks can be utilized by programs to increase representation of skin of color in dermatology training. There also are multiple expanding online dermatologic databases, such as VisualDx, with an increasing focus on skin of color patients, some of which allow users to filter images by degree of skin pigmentation.30 Moreover, instructors also can work to diversify their curricula by highlighting more of the SOCS conditions of importance to skin of color patients, which have since been renamed and highlighted on the Patient Dermatology Education section of the SOCS website.20 These conditions, while not completely comprehensive, provide a useful starting point for medical educators to reevaluate for potential areas of improvement and inclusion.

There are several potential strategies that can be used to better represent skin of color in dermatologic preclinical medical education, including increasing awareness, especially among dermatology teaching faculty, of existing disparities in the representation of skin of color in the preclinical curricula. Additionally, all dermatology teaching materials could be reviewed at the department level prior to being disseminated to medical students to assess for instances in which skin of color could be prioritized for discussion or varying disease presentations in skin of color could be demonstrated. Finally, teaching faculty may consider photographing more clinical images of their skin of color patients to further develop a catalog of diverse images that can be used to teach students.

Study Limitations—Our study was unable to account for verbal discussion of skin of color not otherwise denoted or captured in lecture slides. Additional limitations include the utilization of Fitzpatrick skin types to describe and differentiate varying skin tones, as the Fitzpatrick scale originally was developed as a method to describe an individual’s response to UV exposure.19 The inability to further delineate the representation of darker skin types, such as those that may be classified as Fitzpatrick skin types V or VI,19 compared to those with lighter skin of color also was a limiting factor. This study was unable to assess for discussion of other common conditions affecting skin of color patients that were not listed as one of the priority conditions by SOCS. Photographs that were designated as indeterminate were difficult to elucidate as skin of color; however, it is possible that instructors may have verbally described these images as skin of color during lectures. Nonetheless, it may be beneficial for learners if teaching faculty were to clearly label instances where skin of color patients are shown or when notable differences are present.

Conclusion

Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of audio data from lectures, syllabi, and small group teaching materials from preclinical courses to more accurately assess representation of skin of color in dermatology training. Additionally, future studies also may expand to include images from lectures of overlapping clinical specialties, particularly infectious disease and rheumatology, to provide a broader assessment of skin of color exposure. Furthermore, repeat assessment may be beneficial to assess the longitudinal effectiveness of curricular changes at the institutions included in this study, comparing older lectures to more recent, updated lectures. This study also may be replicated at other medical schools to allow for wider comparison of curricula.

Acknowledgment—The authors wish to thank the institutions that offered and agreed to participate in this study with the hopes of improving medical education.

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods

Participants—Three US medical schools, a blend of private and public medical schools located across different geographic boundaries, agreed to participate in the study. All 3 institutions were current members of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium, whose primary goal is to create the medical school of the future and transform physician training.18 All 32 member institutions of the AMA consortium were contacted to request their participation in the study. As part of the consortium, these institutions have vowed to collectively work to develop and share the best models for educational advancement to improve care for patients, populations, and communities18 and would expectedly provide a more racially and ethnically inclusive curriculum than an institution not accountable to a group dedicated to identifying the best ways to deliver care for increasingly diverse communities.

Data Collection—Lectures were included if they were presented during dermatology preclinical courses in the 2015 to 2016 academic year. An uninvolved third party removed the names and identities of instructors to preserve anonymity. Two independent coders from different institutions extracted the data—lecture title, total number of clinical and histologic images, and number of skin of color images—from each of the anonymized lectures using a standardized coding form. We documented differences in skin of color noted in lectures and the disease context for the discussed differences, such as variations in clinical presentation, disease process, epidemiology/risk, and treatment between different skin phenotypes or ethnic groups. Photographs in which the coders were unable to differentiate whether the patient had skin of color were designated as indeterminate or unclear. Photographs appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI19 were categorically designated as skin of color, and those appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were described as not skin of color; however, images appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin type III often were classified as not skin of color or indeterminate and occasionally skin of color. The Figure shows examples of images classified as skin of color, indeterminate, and not skin of color. Photographs often were classified as indeterminate due to poor lighting, close-up view photographs, or highlighted pathology obscuring the surrounding skin. We excluded duplicate photographs and histologic images from the analyses.

We also reviewed 19 conditions previously highlighted by the SOCS as areas of importance to skin of color patients.20 The coders tracked how many of these conditions were noted in each lecture. Duplicate discussion of these conditions was not included in the analyses. Any discrepancies between coders were resolved through additional slide review and discussion. The final coded data with the agreed upon changes were used for statistical analyses. Recent national demographic data from the US Census Bureau in 2019 describe approximately 39.9% of the population as belonging to racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic/Latinx White.21 Consequently, the standard for adequate representation for skin of color photographs was set at 35% for the purpose of this study.

Results

Across all 3 institutions included in the study, the proportion of the total number of clinical photographs showing skin of color was 16% (290/1812). Eight percent of the total photographs (145/1812) were noted to be indeterminate (Table). For institution 1, 23.6% of photographs (155/658) showed skin of color, and 12.6% (83/658) were indeterminate. For institution 2, 13.1% (76/578) showed skin of color and 7.8% (45/578) were indeterminate. For institution 3, 10.2% (59/576) showed skin of color and 3% (17/576) were indeterminate.

Institutions 1, 2, and 3 had 18, 8, and 17 total dermatology lectures, respectively. Of the 19 conditions designated as areas of importance to skin of color patients by the SOCS, 16 (84.2%) were discussed by institution 1, 11 (57.9%) by institution 2, and 9 (47.4%) by institution 3 (eTable 1). Institution 3 did not include photographs of skin of color patients in its acne, psoriasis, or cutaneous malignancy lectures. Institution 1 also did not include any skin of color patients in its malignancy lecture. Lectures that focused on pigmentary disorders, atopic dermatitis, infectious conditions, and benign cutaneous neoplasms were more likely to display photographs of skin of color patients; for example, lectures that discussed infectious conditions, such as superficial mycoses, herpes viruses, human papillomavirus, syphilis, and atypical mycobacterial infections, were consistently among those with higher proportions of photographs of skin of color patients.

Throughout the entire preclinical dermatology course at all 3 institutions, of 2945 lecture slides, only 24 (0.8%) unique differences were noted between skin color and non–skin of color patients, with 10 total differences noted by institution 1, 6 by institution 2, and 8 by institution 3 (Table). The majority of these differences (19/24) were related to epidemiologic differences in prevalence among varying racial/ethnic groups, with only 5 instances highlighting differences in clinical presentation. There was only a single instance that elaborated on the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of the discussed difference. Of all 24 unique differences discussed, 8 were related to skin cancer, 3 were related to dermatitis, and 2 were related to the difference in manifestation of erythema in patients with darker skin (eTable 2).

Comment

The results of this study demonstrated that skin of color is underrepresented in the preclinical dermatology curriculum at these 3 institutions. Although only 16% of all included clinical photographs were of skin of color, individuals with skin of color will soon represent more than half of the total US population within the next 2 decades.1 To increase representation of skin of color patients, teaching faculty should consciously and deliberately include more photographs of skin of color patients for a wider variety of common conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, in addition to those that tend to disparately affect skin of color patients, such as pseudofolliculitis barbae or melasma. Furthermore, they also can incorporate more detailed discussions about important differences seen in skin of color patients.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Psoriasis Lectures—At institution 3, there were no skin of color patients included in the psoriasis lecture, even though there is considerable data in the literature indicating notable differences in the clinical presentation, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in skin of color patients.11,22 There are multiple nuances in psoriasis manifestation in patients with skin of color, including less-conspicuous erythema in darker skin, higher degrees of dyspigmentation, and greater body surface area involvement. For Black patients with scalp psoriasis, the impact of hair texture, styling practices, and washing frequency are additional considerations that may impact disease severity and selection of topical therapy.11 The lack of inclusion of any skin of color patients in the psoriasis lecture at one institution further underscores the pressing need to prioritize communities of color in medical education.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Cutaneous Malignancy Lectures—Similarly, while a lecturer at institution 2 noted that acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a considerable proportion of melanoma among skin of color patients,23 there was no mention of how melanoma generally is substantially more deadly in this population, potentially due to decreased awareness and inconsistent screening.24 Furthermore, at institutions 1 and 3, there were no photographs or discussion of skin of color patients during the cutaneous malignancy lectures. Evidence shows that more emphasis is needed for melanoma screening and awareness in skin of color populations to improve survival outcomes,24 and this begins with educating not only future dermatologists but all future physicians as well. The failure to include photographs of skin of color patients in discussions or lectures regarding cutaneous malignancies may serve to further perpetuate the harmful misperception that individuals with skin of color are unaffected by skin cancer.25,26

Analysis of Skin of Color Photographs in Infectious Disease Lectures—In addition, lectures discussing infectious etiologies were among those with the highest proportion of skin of color photographs. This relatively disproportionate representation of skin of color compared to the other lectures may contribute to the development of harmful stereotypes or the stigmatization of skin of color patients. Although skin of color should continue to be represented in similar lectures, teaching faculty should remain mindful of the potential unintended impact from lectures including relatively disproportionate amounts of skin of color, particularly when other lectures may have sparse to absent representation of skin of color.

More Photographs Available for Education—Overall, our findings may help to inform changes to preclinical dermatology medical education at other institutions to create more inclusive and representative curricula for skin of color patients. The ability of instructors to provide visual representation of various dermatologic conditions may be limited by the photographs available in certain textbooks with few examples of patients with skin of color; however, concerns regarding the lack of skin of color representation in dermatology training is not a novel discussion.17 Although it is the responsibility of all dermatologists to advocate for the inclusion of skin of color, many dermatologists of color have been leading the way in this movement for decades, publishing several textbooks to document various skin conditions in those with darker skin types and discuss unique considerations for patients with skin of color.27-29 Images from these textbooks can be utilized by programs to increase representation of skin of color in dermatology training. There also are multiple expanding online dermatologic databases, such as VisualDx, with an increasing focus on skin of color patients, some of which allow users to filter images by degree of skin pigmentation.30 Moreover, instructors also can work to diversify their curricula by highlighting more of the SOCS conditions of importance to skin of color patients, which have since been renamed and highlighted on the Patient Dermatology Education section of the SOCS website.20 These conditions, while not completely comprehensive, provide a useful starting point for medical educators to reevaluate for potential areas of improvement and inclusion.

There are several potential strategies that can be used to better represent skin of color in dermatologic preclinical medical education, including increasing awareness, especially among dermatology teaching faculty, of existing disparities in the representation of skin of color in the preclinical curricula. Additionally, all dermatology teaching materials could be reviewed at the department level prior to being disseminated to medical students to assess for instances in which skin of color could be prioritized for discussion or varying disease presentations in skin of color could be demonstrated. Finally, teaching faculty may consider photographing more clinical images of their skin of color patients to further develop a catalog of diverse images that can be used to teach students.

Study Limitations—Our study was unable to account for verbal discussion of skin of color not otherwise denoted or captured in lecture slides. Additional limitations include the utilization of Fitzpatrick skin types to describe and differentiate varying skin tones, as the Fitzpatrick scale originally was developed as a method to describe an individual’s response to UV exposure.19 The inability to further delineate the representation of darker skin types, such as those that may be classified as Fitzpatrick skin types V or VI,19 compared to those with lighter skin of color also was a limiting factor. This study was unable to assess for discussion of other common conditions affecting skin of color patients that were not listed as one of the priority conditions by SOCS. Photographs that were designated as indeterminate were difficult to elucidate as skin of color; however, it is possible that instructors may have verbally described these images as skin of color during lectures. Nonetheless, it may be beneficial for learners if teaching faculty were to clearly label instances where skin of color patients are shown or when notable differences are present.

Conclusion

Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of audio data from lectures, syllabi, and small group teaching materials from preclinical courses to more accurately assess representation of skin of color in dermatology training. Additionally, future studies also may expand to include images from lectures of overlapping clinical specialties, particularly infectious disease and rheumatology, to provide a broader assessment of skin of color exposure. Furthermore, repeat assessment may be beneficial to assess the longitudinal effectiveness of curricular changes at the institutions included in this study, comparing older lectures to more recent, updated lectures. This study also may be replicated at other medical schools to allow for wider comparison of curricula.

Acknowledgment—The authors wish to thank the institutions that offered and agreed to participate in this study with the hopes of improving medical education.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Published March 2015. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Learn more about SOCS. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed September 14, 2021. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(suppl 2):S41-S62.

- Berardesca E, Maibach H. Ethnic skin: overview of structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S139-S142.

- Callender VD, Surin-Lord SS, Davis EC, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Grimes PE, Stockton T. Pigmentary disorders in blacks. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:271-281.

- Halder RM, Nootheti PK. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S143-S148.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin: special considerations for therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:184-195.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Ramsay DL, Mayer F. National survey of undergraduate dermatologic medical education. Arch Dermatol.1985;121:1529-1530.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii.

- Knable A, Hood AF, Pearson TG. Undergraduate medical education in dermatology: report from the AAD Interdisciplinary Education Committee, Subcommittee on Undergraduate Medical Education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:467-470.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16-19.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Skin of Color Society. Patient dermatology education. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/patient-dermatology-education

- QuickFacts: United States. US Census Bureau website. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Pipitone M, Robinson JK, Camara C, et al. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: a Hispanic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:118-123.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Taylor SSC, Serrano AMA, Kelly AP, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Dadzie OE, Petit A, Alexis AF, eds. Ethnic Dermatology: Principles and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG, eds. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Springer; 2014.

- VisualDx. New VisualDx feature: skin of color sort. Published October 14, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.visualdx.com/blog/new-visualdx-feature-skin-of-color-sort/

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Published March 2015. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Learn more about SOCS. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed September 14, 2021. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(suppl 2):S41-S62.

- Berardesca E, Maibach H. Ethnic skin: overview of structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S139-S142.

- Callender VD, Surin-Lord SS, Davis EC, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Grimes PE, Stockton T. Pigmentary disorders in blacks. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:271-281.

- Halder RM, Nootheti PK. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S143-S148.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin: special considerations for therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:184-195.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Ramsay DL, Mayer F. National survey of undergraduate dermatologic medical education. Arch Dermatol.1985;121:1529-1530.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii.

- Knable A, Hood AF, Pearson TG. Undergraduate medical education in dermatology: report from the AAD Interdisciplinary Education Committee, Subcommittee on Undergraduate Medical Education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:467-470.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16-19.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Skin of Color Society. Patient dermatology education. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/patient-dermatology-education

- QuickFacts: United States. US Census Bureau website. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Pipitone M, Robinson JK, Camara C, et al. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: a Hispanic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:118-123.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Taylor SSC, Serrano AMA, Kelly AP, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Dadzie OE, Petit A, Alexis AF, eds. Ethnic Dermatology: Principles and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG, eds. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Springer; 2014.

- VisualDx. New VisualDx feature: skin of color sort. Published October 14, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.visualdx.com/blog/new-visualdx-feature-skin-of-color-sort/

Practice Points

- The United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color.

- Our study results strongly suggest that skin of color may be seriously underrepresented in medical education and can guide modifications to preclinical dermatology medical education to develop a more comprehensive and inclusive curriculum.

- Efforts should be made to increase images and discussion of skin of color in preclinical didactics.

Management of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in a Multidisciplinary Rheumatology/Dermatology Clinic

Psoriasis is a commonly encountered systemic condition, usually presenting with chronic erythematous plaques with an overlying silvery white scale.1 Extracutaneous manifestations, such as joint or spine (axial) involvement, can occur along with this skin disorder. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, heterogeneous disorder characterized by inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriasis.2,3 Until recently treatment of PsA has been limited to a few medications.

Continuing investigations into the pathogenesis of PsA have revealed new treatment options, targeting molecules at the cellular level. Over the past few years, additional medications have been approved, giving providers more options in treating patients with psoriasis and PsA. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach by both rheumatologists and dermatologists in evaluating and managing patients at VA clinics has helped optimize care of these patients by providing timely evaluation and treatment at the same visit.

Psoriasis Presentation and Diagnosis

Genetic predisposition and certain environmental factors (trauma, infection, medications) are known to trigger psoriasis, which can present in many forms.4 Chronic plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common skin pattern with a classic presentation of sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale.4 It affects the scalp, lower back, umbilicus, genitals, and extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees. Guttate psoriasis is recognized by its multiple small papules and plaques in a droplike pattern. Pustular psoriasis usually presents with widespread pustules. On the other hand, erythrodermic psoriasis manifests as diffuse erythema involving multiple skin areas.4 Erythematous psoriatic plaques, which are predominantly in the intertriginous areas or skin folds (inguinal, perineal, genital, intergluteal, axillary, or inframammary), are known as inverse psoriasis.

A psoriasis diagnosis is made by taking a history and a physical examination. Rarely, a skin biopsy of the lesions will be required for an atypical presentation. The course of the disease is unpredictable, variable, and dependent on the type of psoriasis. Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic condition, whereas guttate psoriasis is often self-limited.4 A poorer prognosis is seen in patients with erythrodermic and generalized pustular psoriasis.4

Psoriatic Arthritis Presentation, Classification, and Diagnosis

Prevalence of PsA is not known, but it is estimated to be from 0.3% to 1% of the U.S. population. In the psoriasis population, PsA is reported to range from 7% to 42%,3 although more recently, these numbers have been found to be in the 15% to 25% range (unpublished observations). This type of inflammatory arthritis can develop at any age but usually is seen between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with men being affected equally or a little more than are women.3 Clinical symptoms usually include pain and stiffness of affected joints, > 30 minutes of morning stiffness, and fatigue.

The presentation of joint involvement can vary widely. Five subtypes of arthritis were identified by Moll and Wright in 1973, which included arthritis with predominant distal interphalangeal involvement, arthritis mutilans, symmetric polyarthritis (> 5 joints), asymmetric oligoarthritis (1-4 joints), and predominant spondylitis (axial).5 Patients with PsA may also have evidence of spondylitis (inflammation of vertebra) or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) with back pain > 3 months, hip or buttock pain, nighttime pain, or pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest.6 The cervical spine is more frequently involved than is the lumbar spine in patients with PsA.3

Psoriatic arthritis can have a diverse presentation not only with the affected joints, but also involving nails, tendons, and ligaments. An entire digit of the hand or foot can become swollen, known as dactylitis, or “sausage digit.” Inflammation at the insertion of tendons or ligaments, known as enthesitis, is also seen in PsA. Most common sites include the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and ligamentous insertions around the pelvic bones.3 Nail changes that are typically seen in patients with psoriasis can be seen in PsA as well, including pitting, ridging, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis.3 Ocular inflammation which is classically seen with other spondyloarthropathies, can be seen in patients with PsA as well, frequently manifesting as conjunctivitis.2,3

Psoriatic arthritis is commonly classified under the broader category of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, given the low frequency of a positive rheumatoid factor.3 Currently, there are no laboratory tests that can help with a PsA diagnosis.3 Acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may be elevated, indicating active inflammation.

Radiographic data, such as X-rays of the hands and feet, can confirm the clinical distribution of joint involvement and show evidence of erosive changes. Further destructive changes include osteolysis (bone resorption) that may cause the classic pencil-in-cup deformity, typically seen in arthritis mutilans (Figure 1).3 Other radiographic evidence of PsA can include proliferative changes with new bone formation seen along the shaft of the metacarpal and metatarsal bones.3 Patients with axial involvement can have evidence of asymmetric sacroiliitis, which can be seen on radiographs. Asymmetric syndesmophytes, or bony outgrowths, can also be seen throughout the axial spine.3

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical presentation of a patient with the help of laboratory work and radiographs. Other forms of arthritis (such as rheumatoid arthritis, crystal arthropathies, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis) should be excluded. Given the varied presentation of PsA, classification criteria have been developed to assist in clinical research. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) have been developed and validated as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis and a source for clinical research (Table 1).7 Musculoskeletal pain in patients with psoriasis can be due to causes other than PsA, such as osteoarthritis and gout. A close working relationship in a combined rheumatology/dermatology clinic is vital to providing optimal diagnostic and treatment care for patients with psoriasis and PsA.8

The etiology of PsA is currently unknown, although many genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors have been identified that play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. In this setting, immunologically mediated processes that cause inflammation occur in the synovium of joints, enthesium, bone, and skin of patients with PsA.9 Studies have shown that activated T cells and T-cell–derived cytokines play an important role in cartilage degradation, joint damage, and stimulating bone resorption.9

One particular proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), has been the target for many treatment modalities for several years. With new and ongoing research into the PsA pathogenesis, other treatment options have been discovered, targeting different cytokines and T cells that are involved in the disease process. This has led to drug trials and recent FDA approvals of several new medications, which provide further options for clinicians in managing and treating PsA.

Management of Psoriasis

Choice of therapy is determined by the extent and severity of psoriasis (body surface area [BSA] involvement) as well as the patient’s comorbidities and preferences.4 Providers have a wide spectrum of effective therapies to prescribe, both topically and systemically. Topical therapy options include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 and analogs (calcipotriene), anthralin, tar, tazarotene (third-generation retinoid), and calcineurin inhibitors (tacromlimus).4 Phototherapy with or without saltwater baths helps improve skin lesions.

These treatments are beneficial for all patients with psoriasis, but the disease can be controlled with monotherapy in patients with mild-to-moderate disease (< 10% BSA). Limiting these treatment options are some long-term effects of the medications because of the potential for toxicity as well as decreasing efficacy of the medication over time.4 For patients with more BSA involvement (> 10%), systemic treatment options include methotrexate (MTX), systemic retinoids (acitretin), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine), and biologics. Many of these systemic treatment options overlap for patients with both psoriasis and PsA, and topical treatments can be used adjunctively to better control the skin disease.

Management of Psoriatic Arthritis

It is important to identify PsA and begin treatment early, because it has been shown that patients tend to fare better in their disease course if treated early.10 Once a diagnosis of PsA is made, disease activity needs to be determined by clinical examination and radiographs of joints. Scoring systems, by assessing bone erosions and deformities on joint radiographs, can aide with this assessment. Based on these, PsA can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. Several disease activity measures that have been developed for clinical trials in monitoring of disease activity can be used as an aide in the office setting. These tools are still being studied to determine the optimal measure of disease activity.

NSAIDs and Glucocorticoids