User login

Lack of Significant Anti-inflammatory Activity With Clindamycin in the Treatment of Rosacea: Results of 2 Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Trials

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

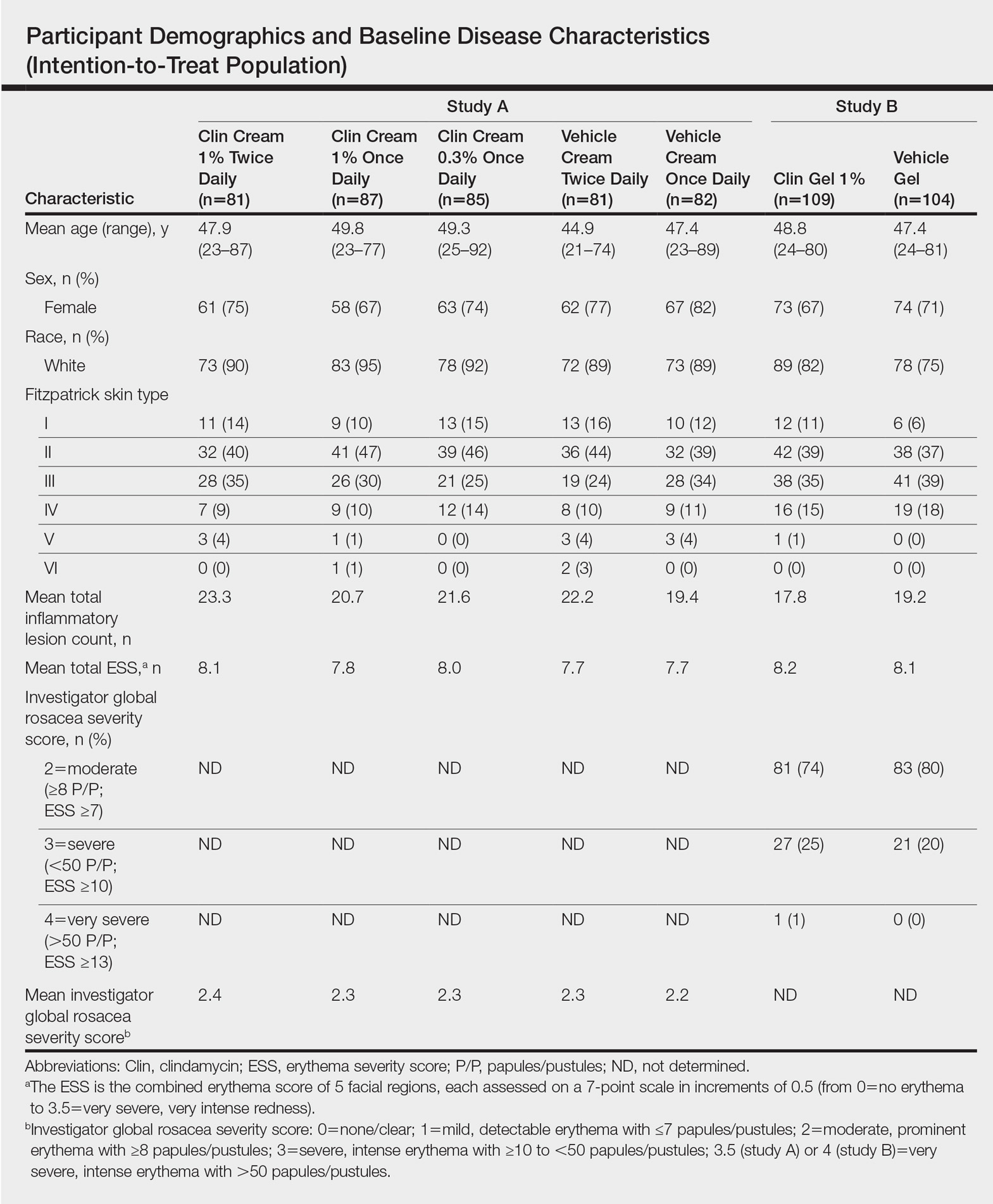

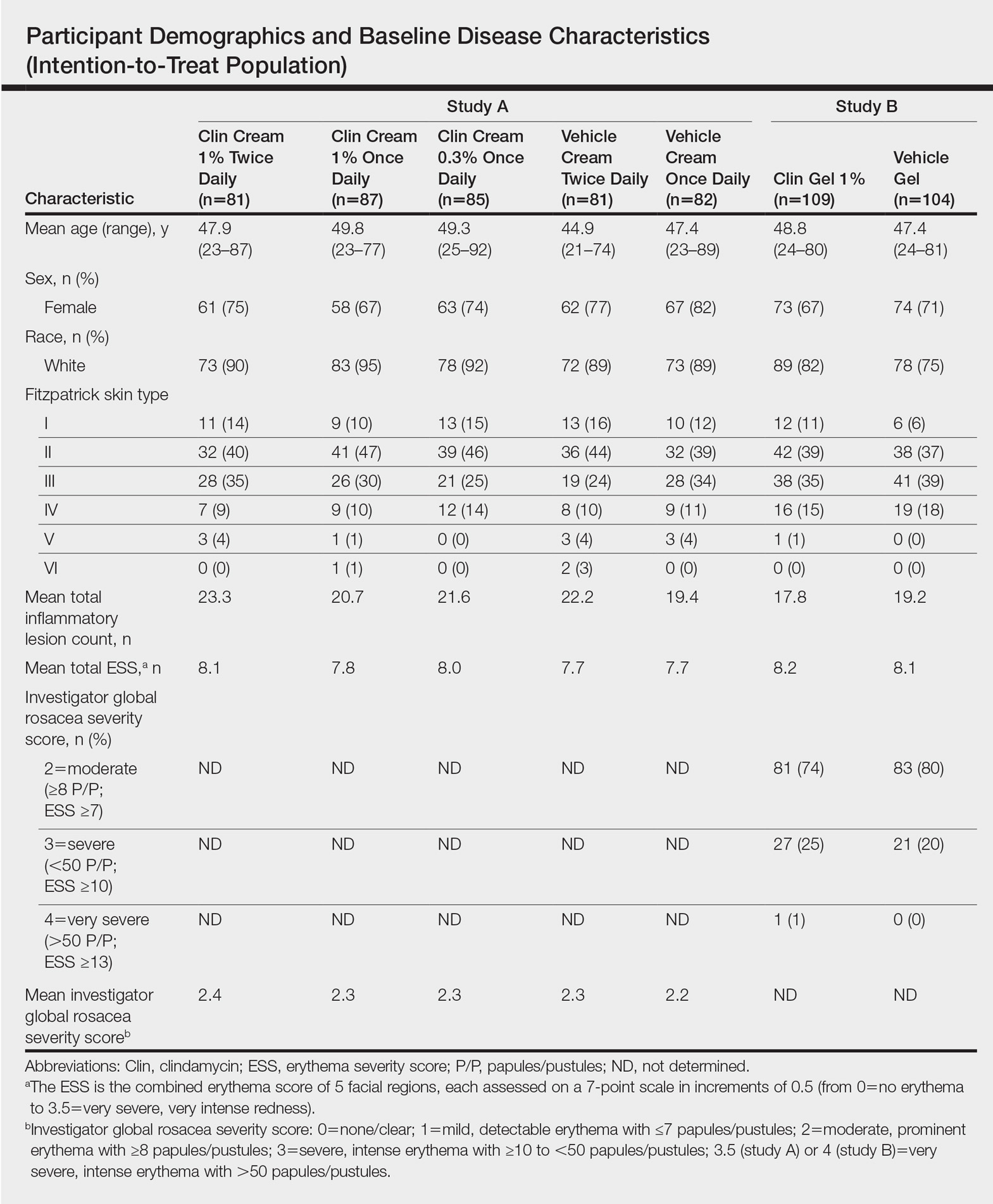

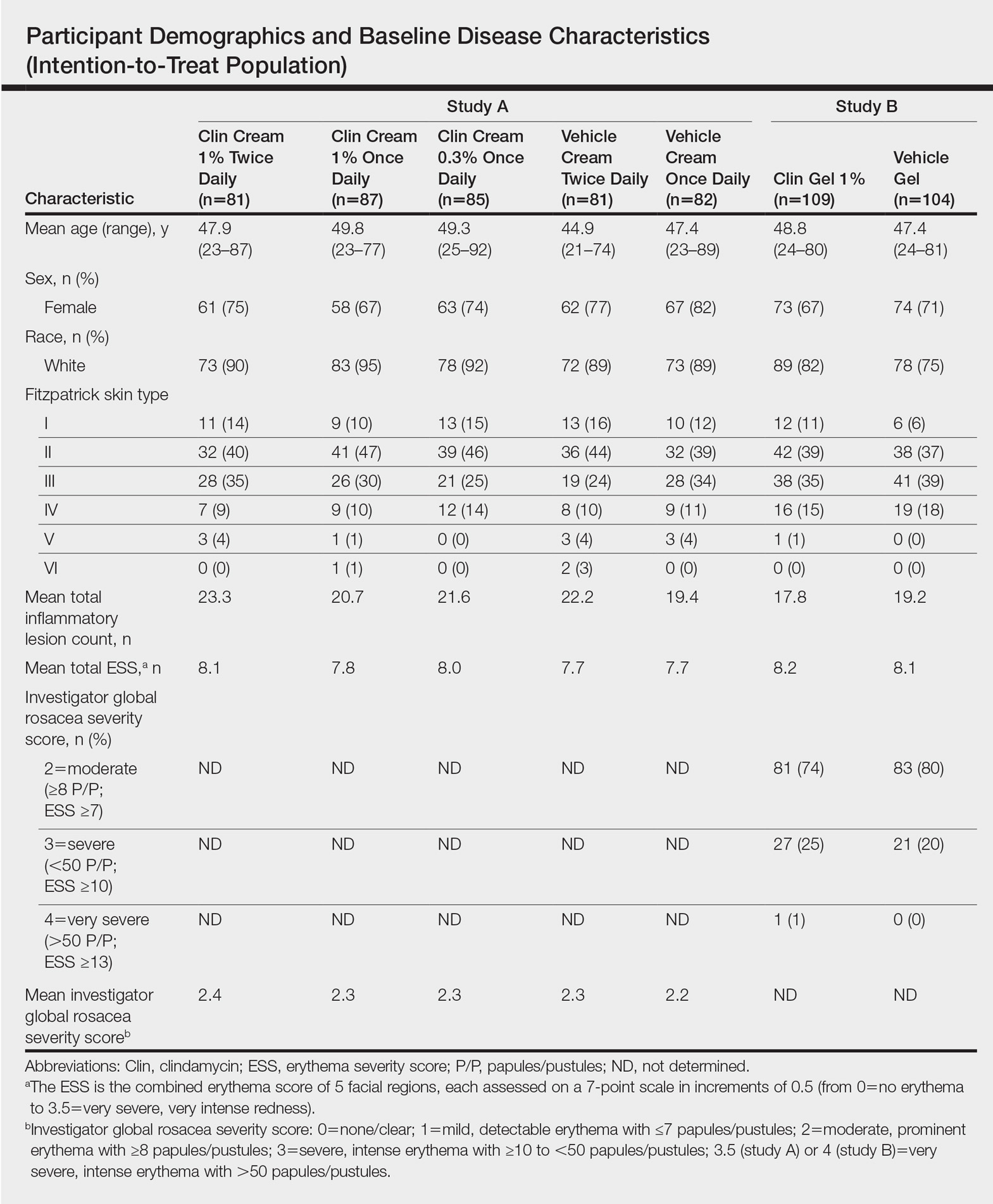

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

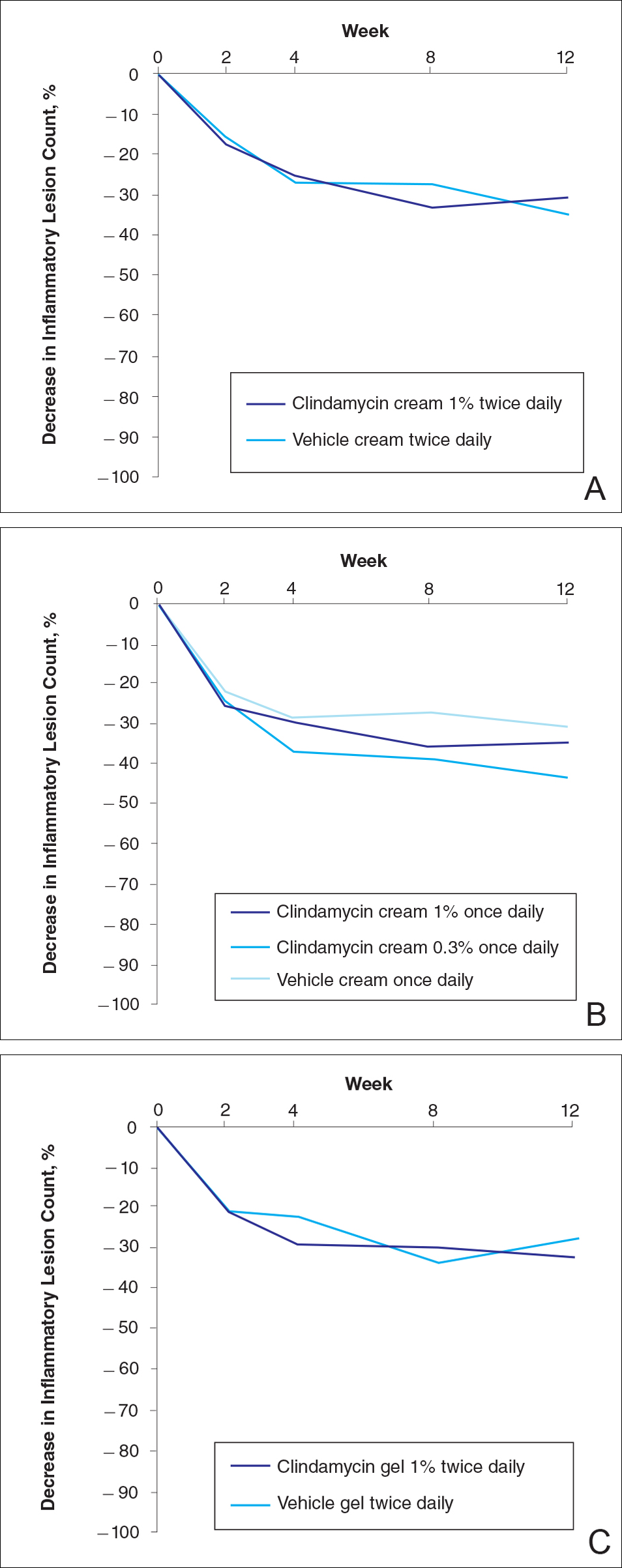

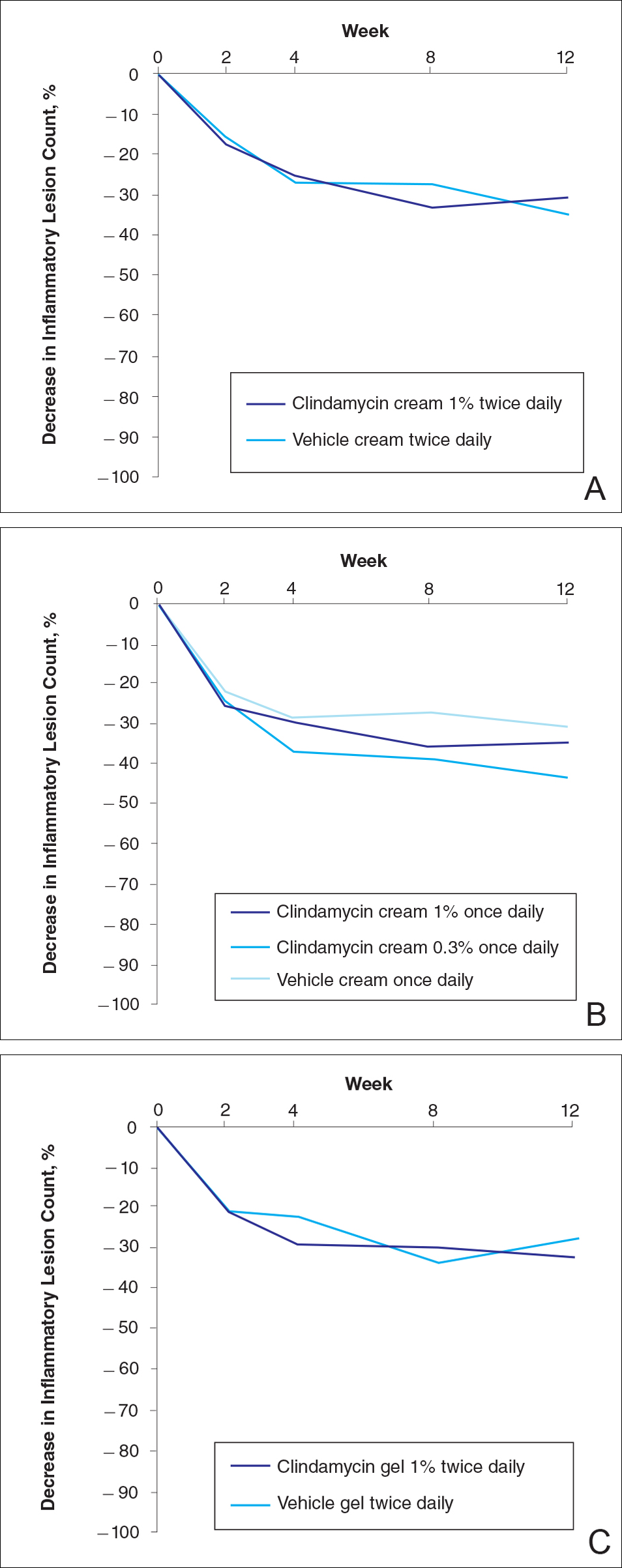

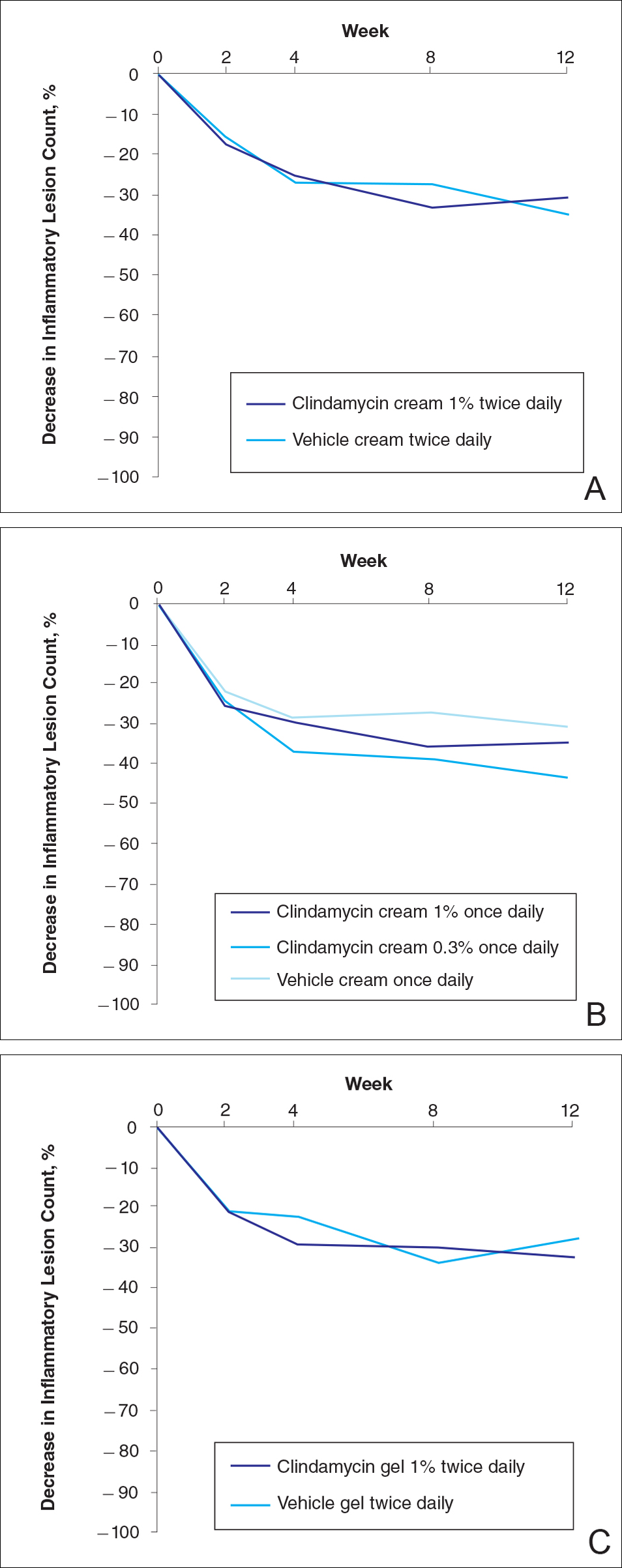

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

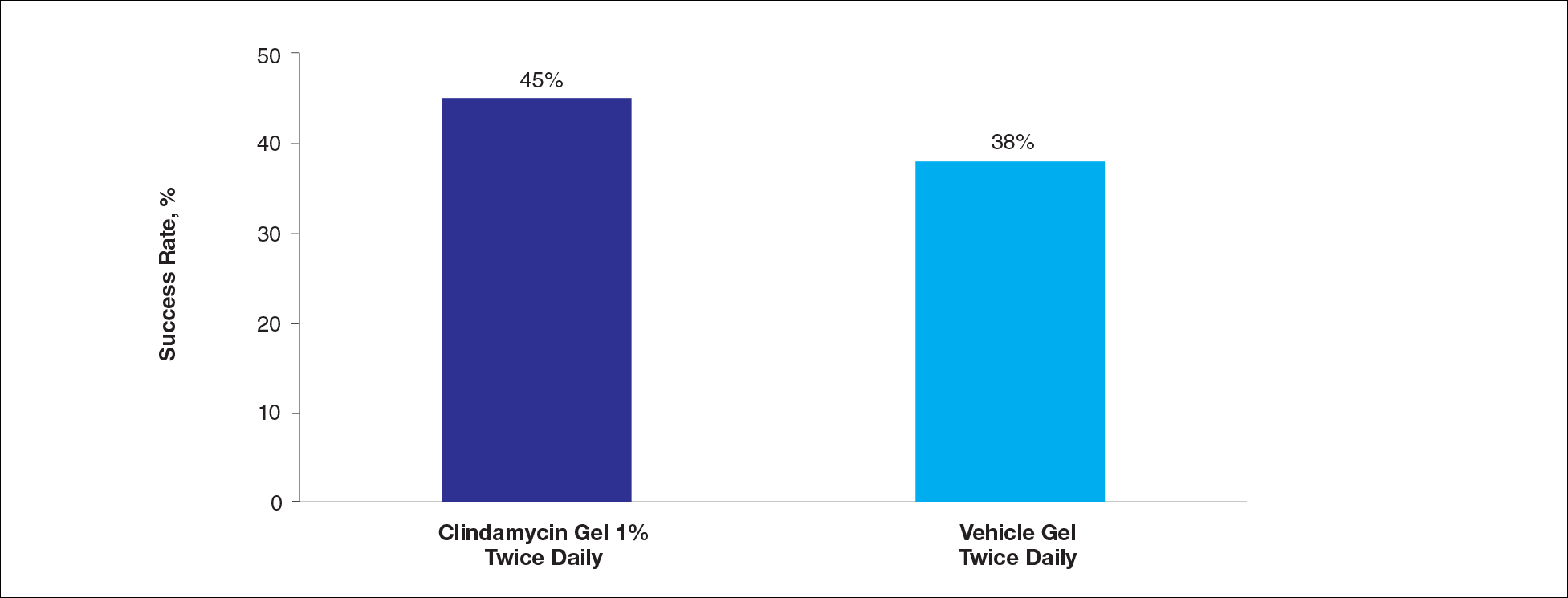

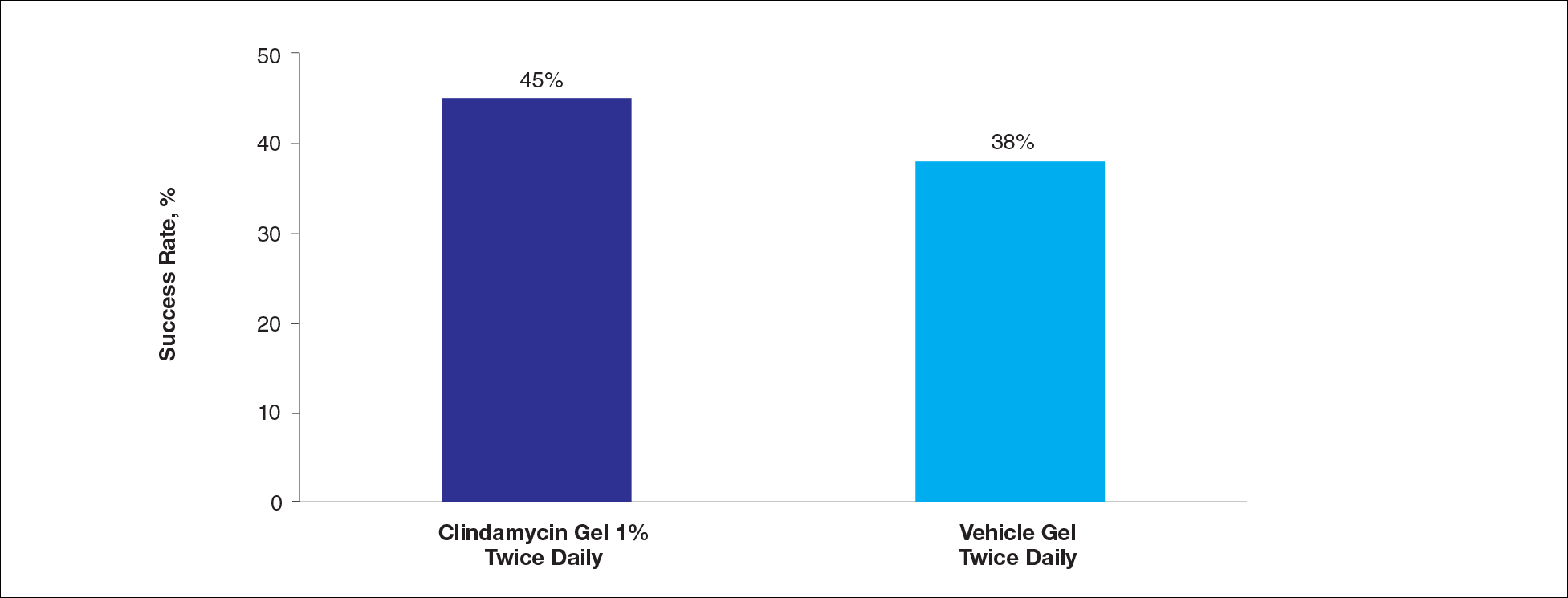

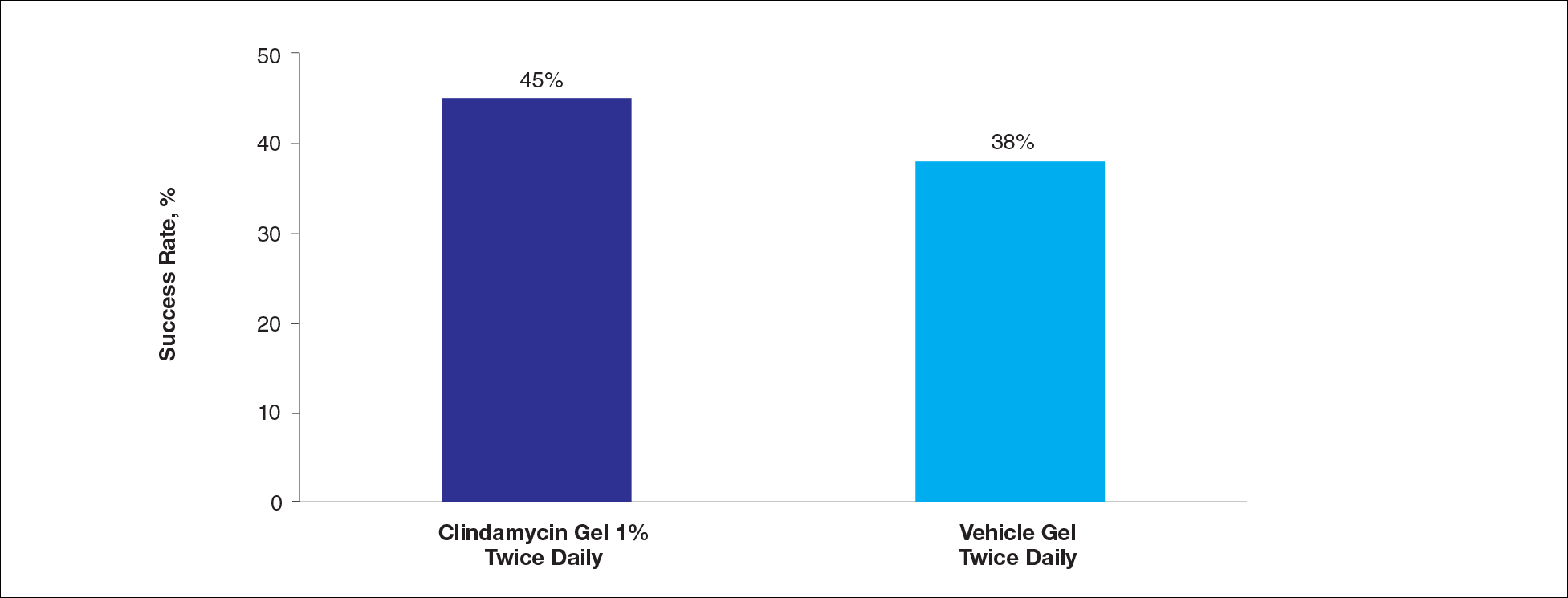

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

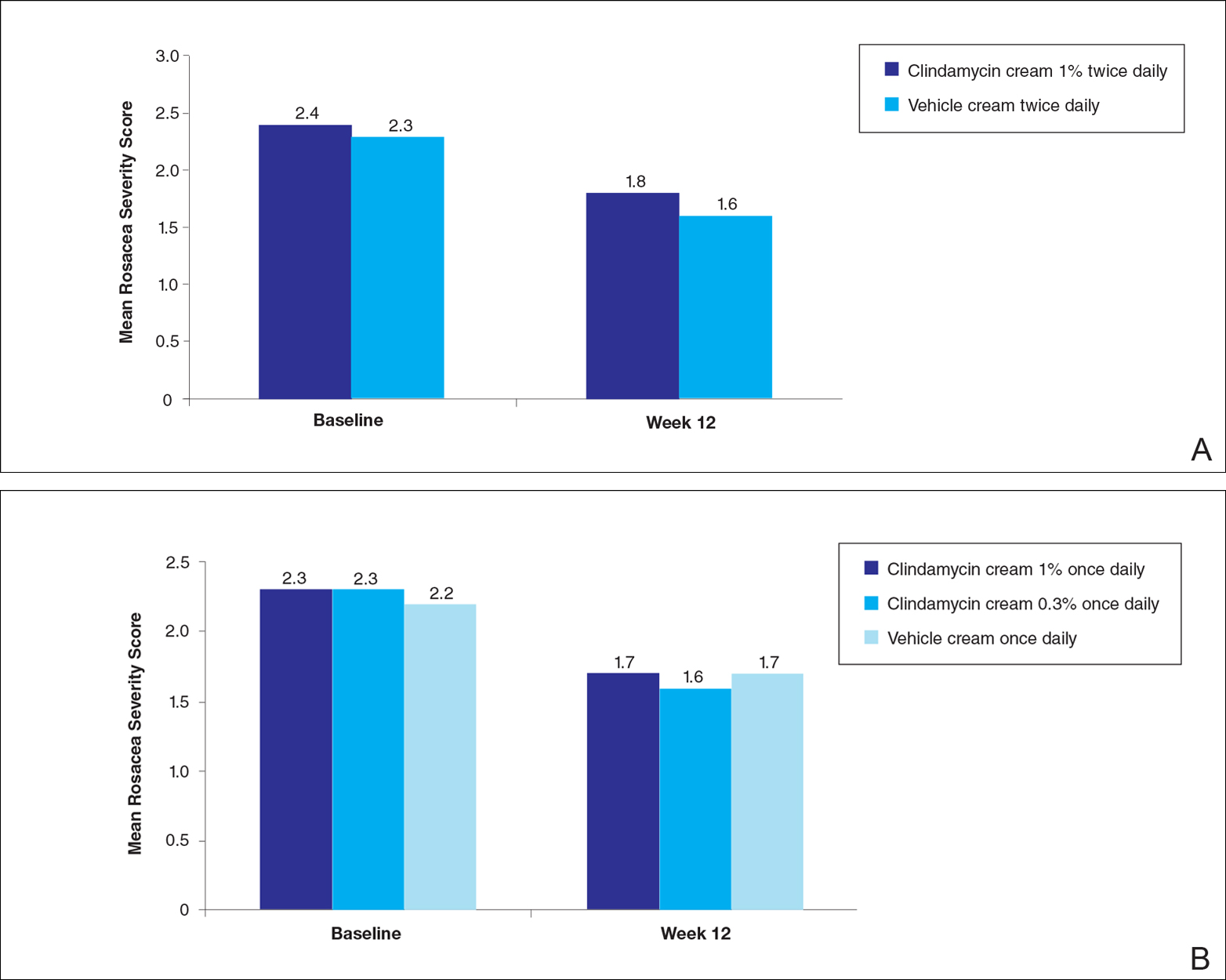

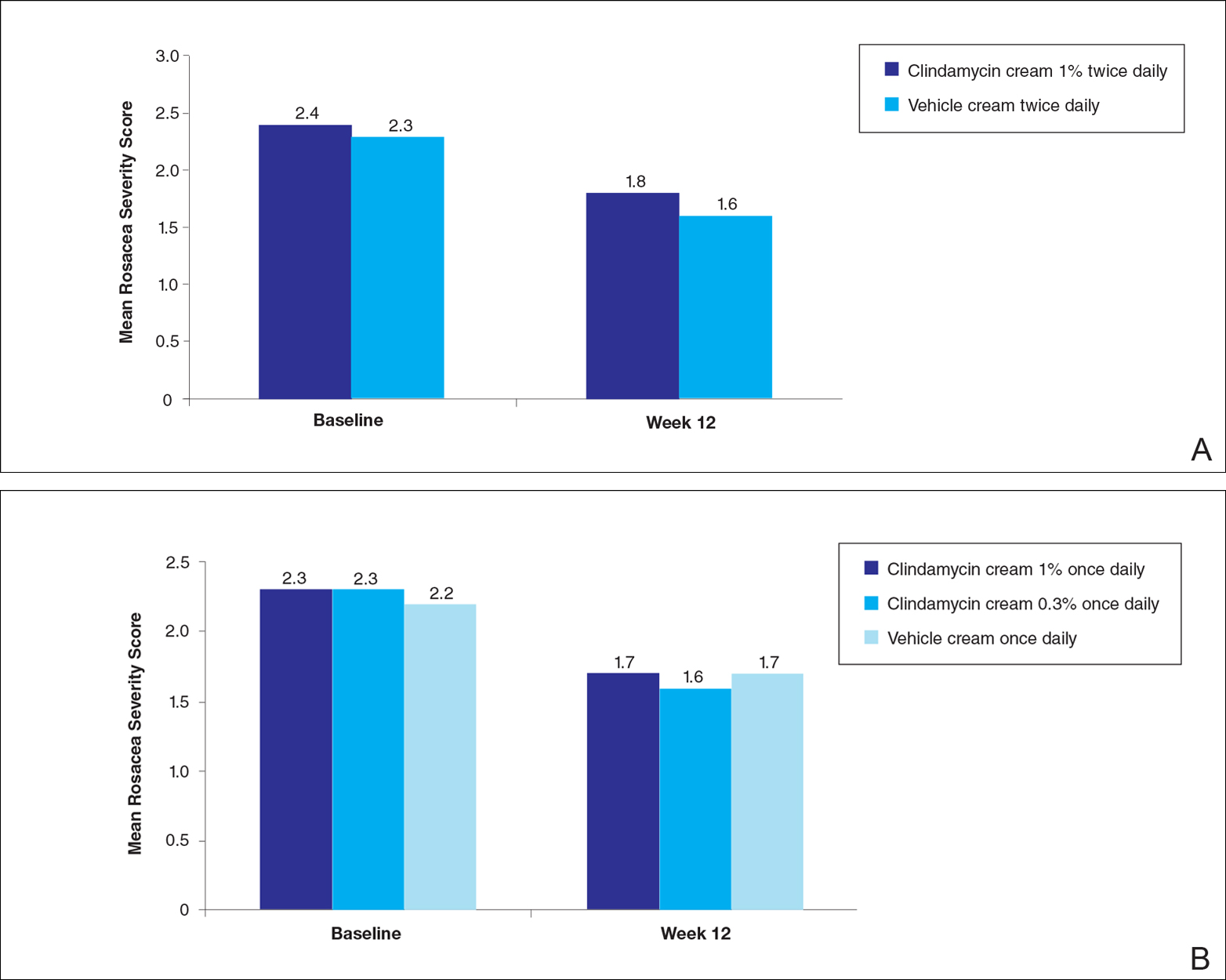

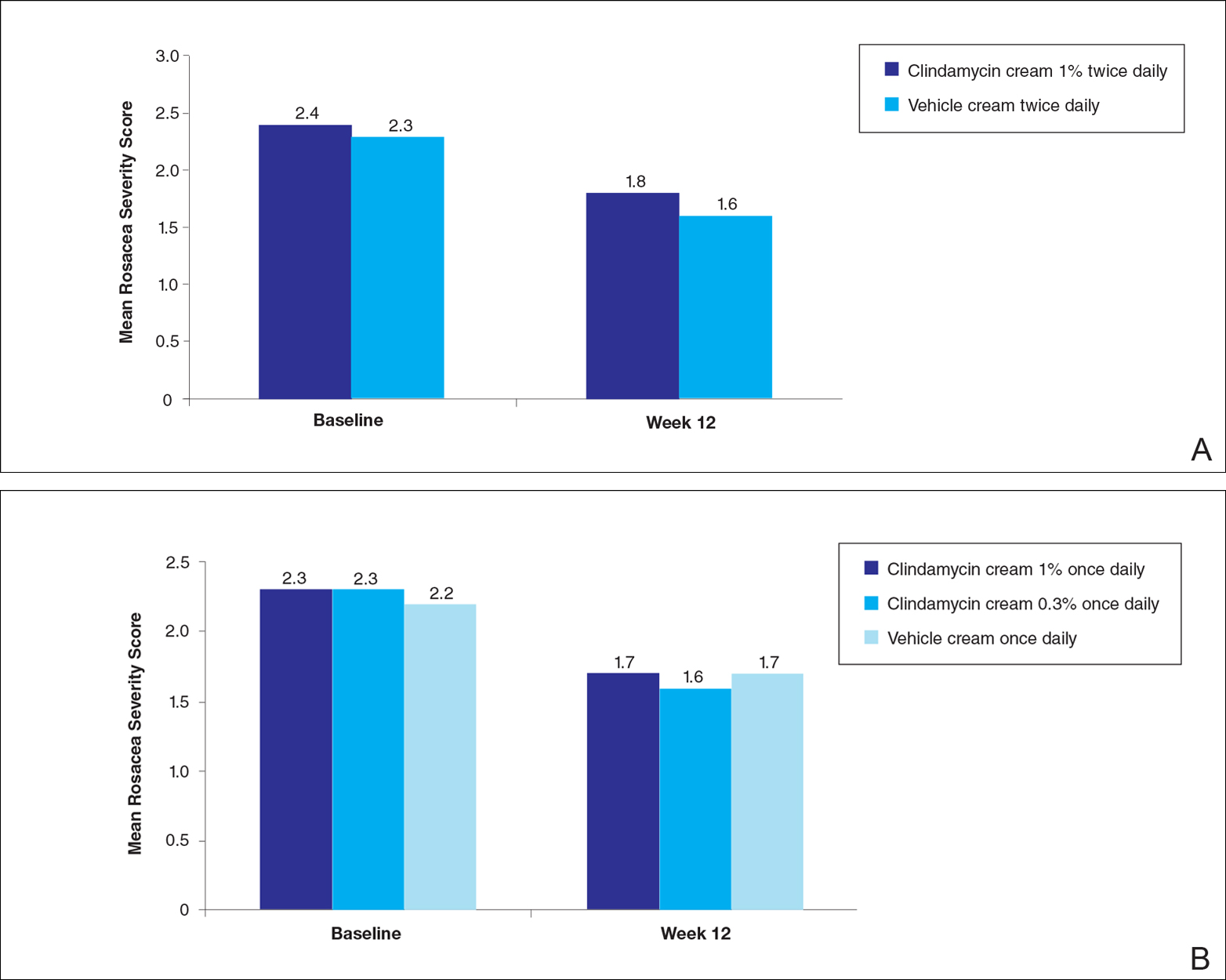

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

Practice Points

- Clindamycin cream 0.3% and 1% and clindamycin gel 1% were no more effective than their respective vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

- Clindamycin may have no intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity in rosacea.

Primary Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection Following Squamous Cell Carcinoma Excision

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

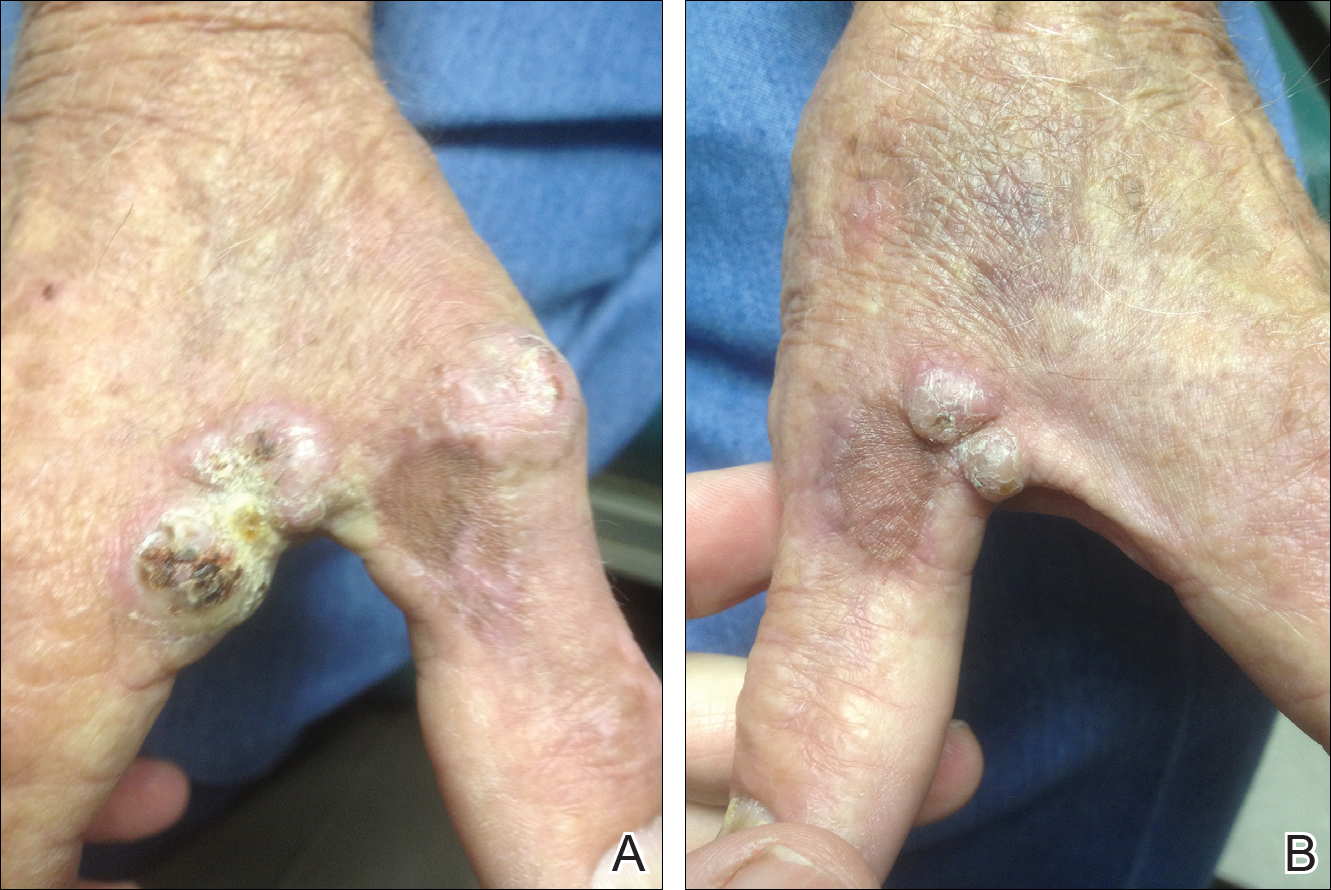

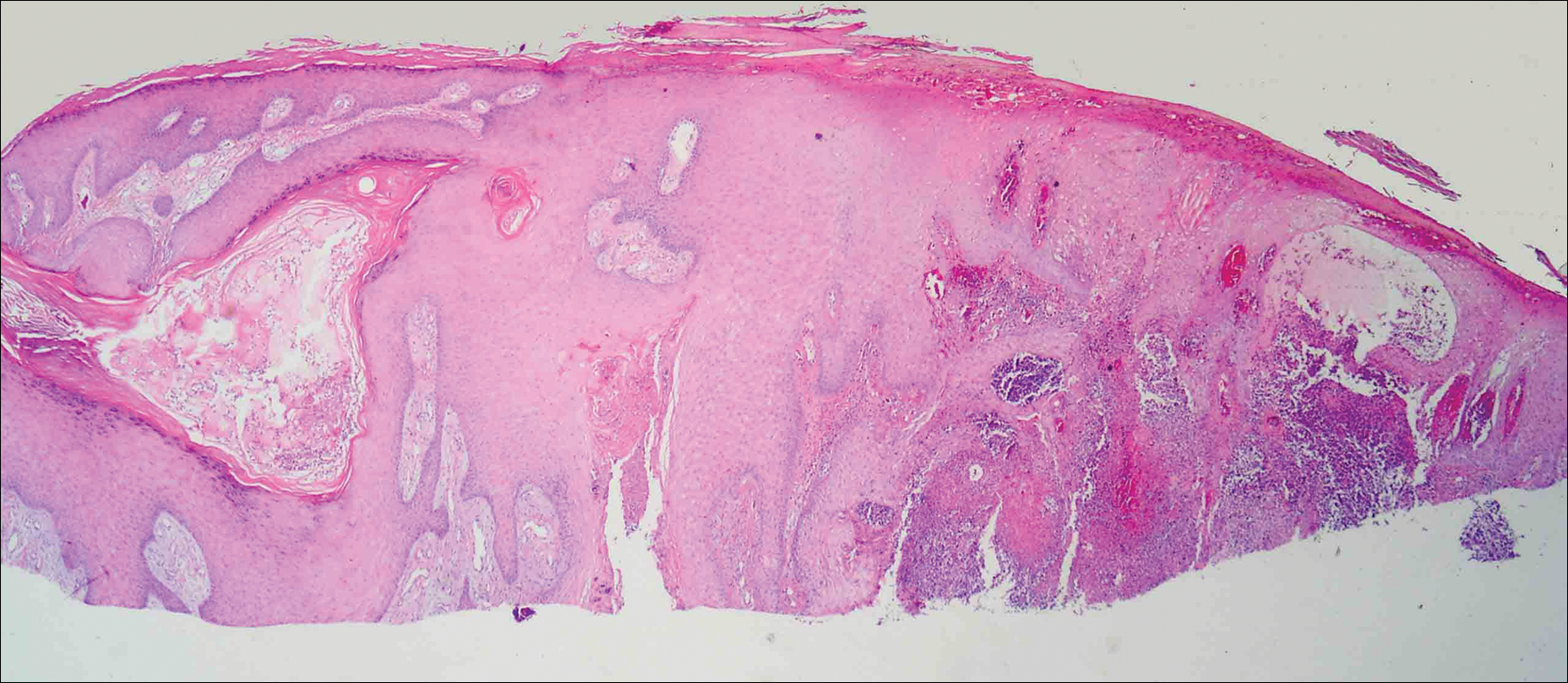

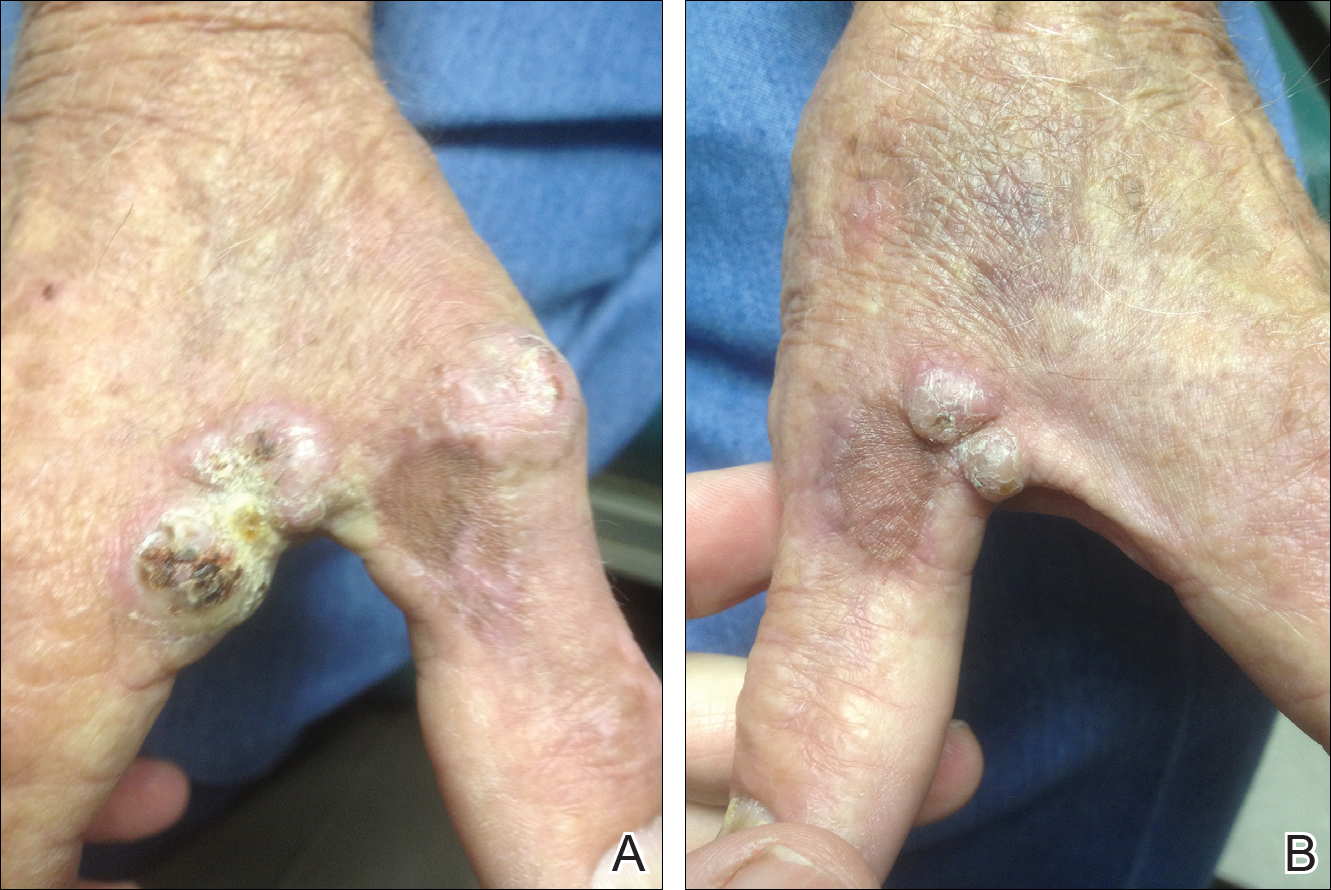

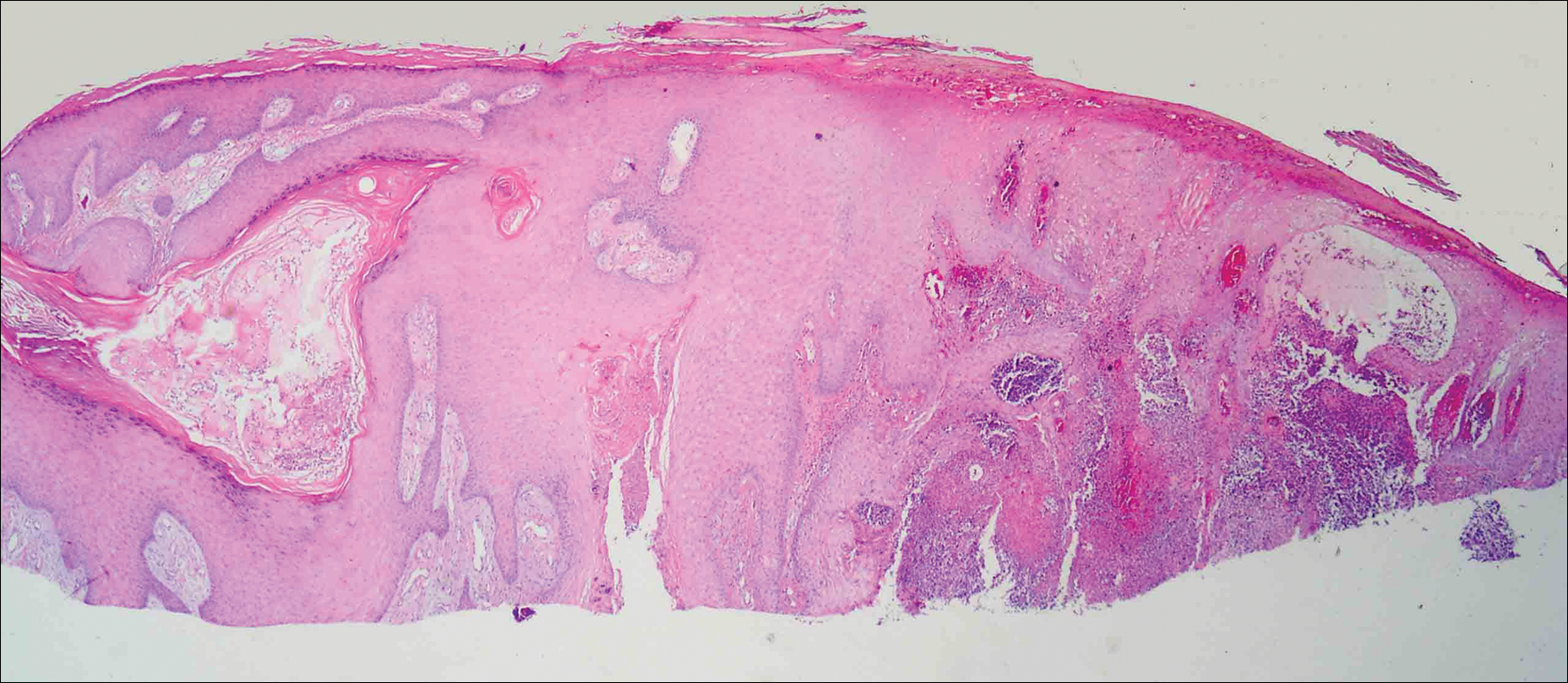

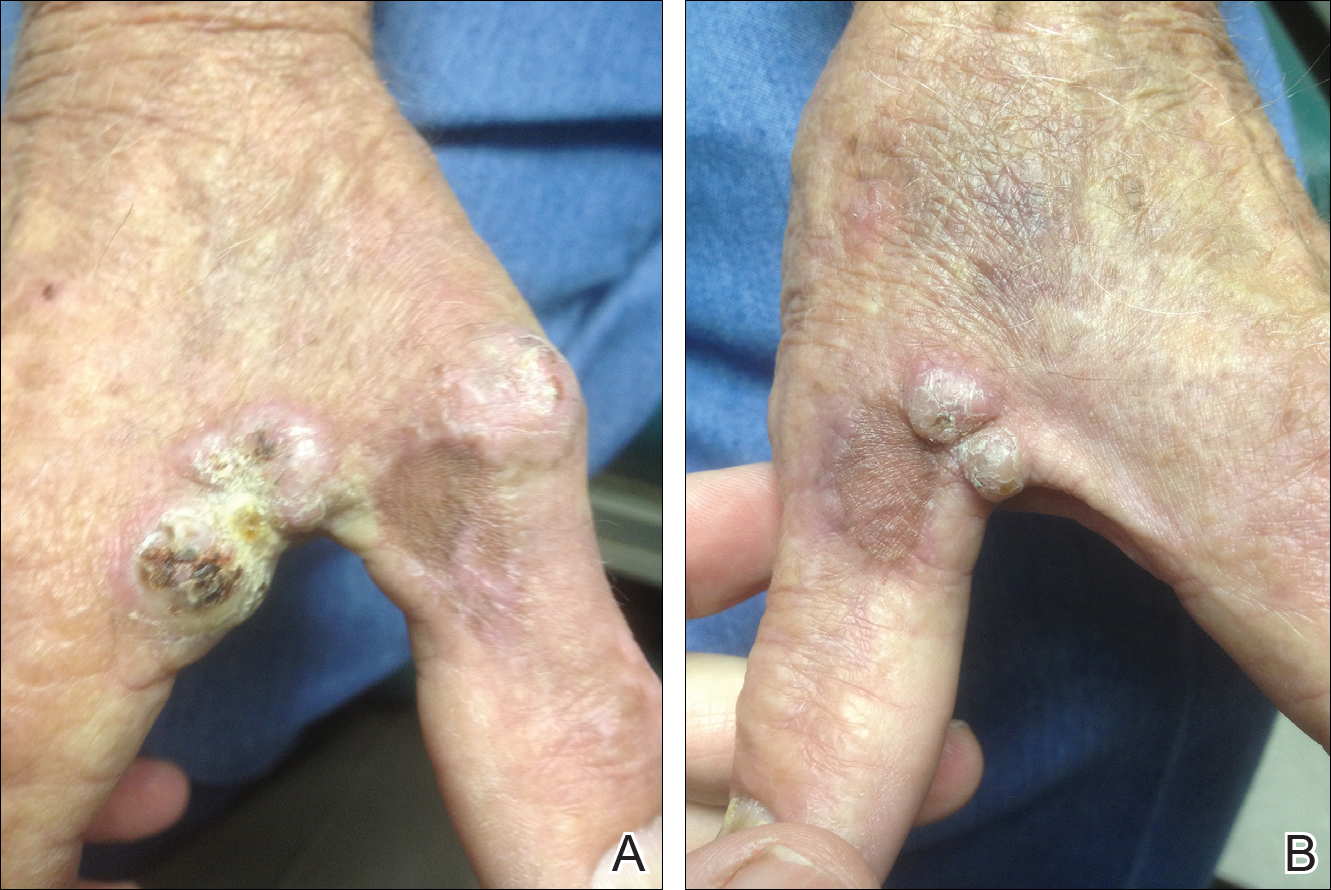

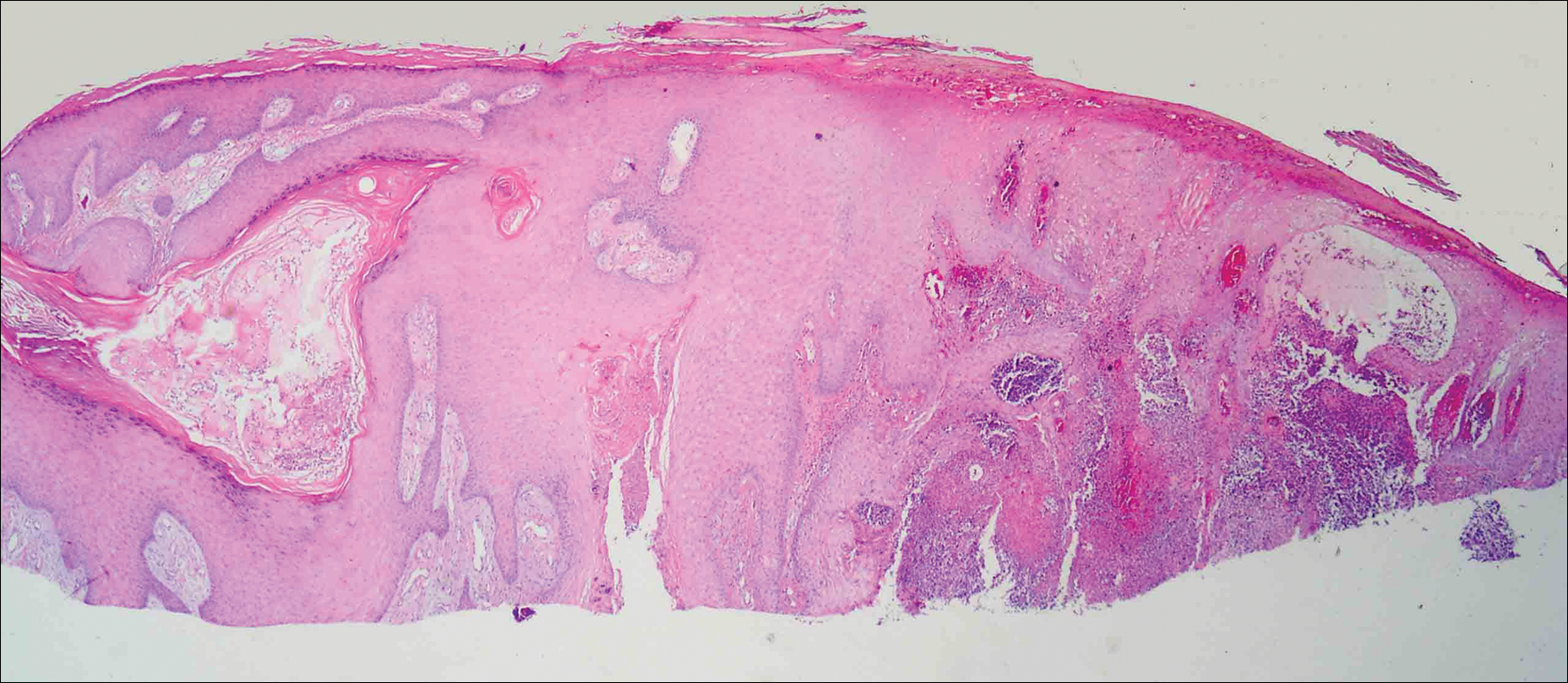

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.

- Dommasch E, Gelfand JM. Is there truly a risk of lymphoma from biologic therapies? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:418-430.

- Yonekura N, Yokota S, Yonekura K, et al. Interferon-γ downregulates Hsp27 expression and suppresses the negative regulation of cell death in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:313-322.

- Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:67-70.

- Dorman S, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon γ receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113-2121.

- Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, et al. Novel mutation in the interferon-γ receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137-139.

- Toyoda H, Ido M, Nakanishi K, et al. Multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in a patient with interferon γ receptor 2 (IFNγR2) deficiency [published online June 18, 2010]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:631-634.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.