User login

Bowel-Associated Dermatosis-Arthritis Syndrome in a Patient With Crohn Disease

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

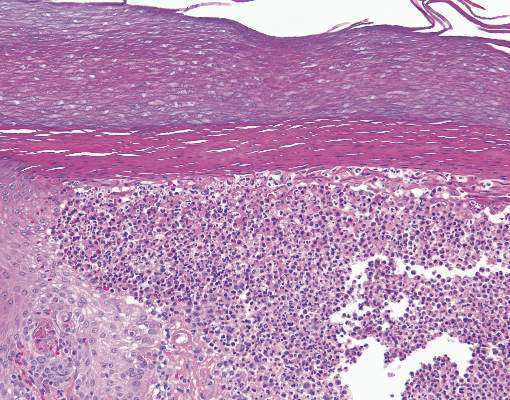

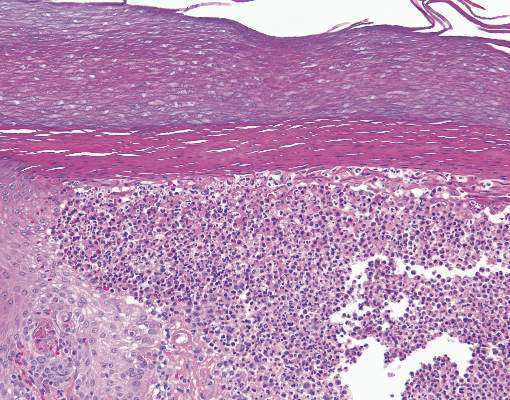

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

Scaly Plaque With Pustules and Anonychia on the Middle Finger

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

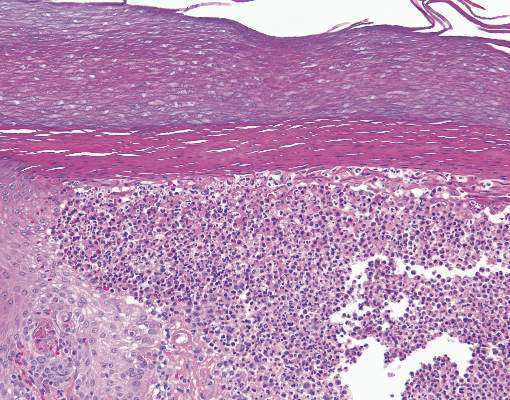

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is considered to be a form of acropustular psoriasis that presents as a sterile, pustular eruption initially affecting the fingertips and/or toes.1 The slow-growing pustules typically progress locally and can lead to onychodystrophy and/or osteolysis of the underlying bone.2,3 Most commonly affecting adult women, ACH often begins following local trauma to or infection of a single digit.4 As the disease progresses proximally, the small pustules burst, leaving a shiny, erythematous surface on which new pustules can develop. These pustules have a tendency to amalgamate, leading to the characteristic clinical finding of lakes of pus. Pustules frequently appear on the nail matrix and nail bed presenting as severe onychodystrophy and ultimately anonychia.5,6 Rarely, ACH can be associated with generalized pustular psoriasis as well as conjunctivitis, balanitis, and fissuring or annulus migrans of the tongue.2,7

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, biopsy, and bacterial and fungal cultures revealing sterile pustules.8,9 Histologic findings are similar to those seen in pustular psoriasis, demonstrating subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels with lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.10

Due to the refractory nature of the disease, there are no recommended guidelines for treatment of ACH. Most successful treatment regimens consist of topical psoriasis medications combined with systemic psoriatic therapies such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic therapy.8,11-16 Our patient achieved satisfactory clinical improvement with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily alternating with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Suchanek J. Relation of Hallopeau’s acrodermatitis continua to psoriasis. Przegl Dermatol. 1951;1:165-181.

- Adam BA, Loh CL. Acropustulosis (acrodermatitis continua) with resorption of terminal phalanges. Med J Malaysia. 1972;27:30-32.

- Mrowietz U. Pustular eruptions of palms and soles. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LS, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215-218.

- Yerushalmi J, Grunwald MH, Hallel-Halevy D, et al. Chronic pustular eruption of the thumbs. diagnosis: acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau (ACH). Arch Dermatol. 2000:136:925-930.

- Granelli U. Impetigo herpetiformis; acrodermatitis continue of Hallopeau and pustular psoriasis; etiology and pathogenesis and differential diagnosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1956;31:120-126.

- Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson B, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2005:174-210.

- Radcliff-Crocker H. Diseases of the Skin: Their Descriptions, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son, & Co; 1888.

- Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S, et al. Review: acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: evolution of treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1195-1211.

- Post CF, Hopper ME. Dermatitis repens: a report of two cases with bacteriologic studies. AMA Arc Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:220-223.

- Sehgal VN, Sharma S. The significance of Gram’s stain smear, potassium hydroxide mount, culture and microscopic pathology in the diagnosis of acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Skinmed. 2011;9:260-261.

- Mosser G, Pillekamp H, Peter RU. Suppurative acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. a differential diagnosis of paronychia. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:386-390.

- Piquero-Casals J, Fonseca de Mello AP, Dal Coleto C, et al. Using oral tetracycline and topical betamethasone valerate to treat acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Cutis. 2002;70:106-108.

- Tsuji T, Nishimura M. Topically administered fluorouracil in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:27-28.

- Van de Kerkhof PCM. In vivo effects of vitamin D3 analogs. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;(suppl 3):S25-S29.

- Kokelj F, Plozzer C, Trevisan G. Uselessness of topical calcipotriol as monotherapy for acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:153.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

A 69-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a persistent rash on the right middle finger of 5 years’ duration (left). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated scaly plaque with pustules and anonychia localized to the right middle finger (right). Fungal and bacterial cultures revealed sterile pustules. The patient was successfully treated with an occluded superpotent topical steroid alternating with a topical vitamin D analogue.