User login

Treatment of Grade III Acromioclavicular Separations in Professional Baseball Pitchers: A Survey of Major League Baseball Team Physicians

ABSTRACT

Despite advancements in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the treatment of grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations, particularly in throwing athletes. Twenty-eight major league baseball (MLB) orthopedic team physicians were surveyed to determine their definitive management of a grade III AC separation in the dominant arm of a professional baseball pitcher and their experience treating AC joint separations in starting pitchers and position players. Return-to-play outcomes were also evaluated. Twenty (71.4%) team physicians recommended nonoperative intervention compared to 8 (28.6%) who would have operated acutely. Eighteen (64.3%) team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation; 51 (77.3%) pitchers had been treated nonoperatively compared to 15 (22.7%) operatively. No difference was observed in the proportion of pitchers who returned to the same level of play (P = .54), had full, unrestricted range of motion (P = .23), or had full pain relief (P = .19) between the operatively and nonoperatively treated MLB pitchers. The majority (53.6%) of physicians would not include an injection if the injury was treated nonoperatively. Open coracoclavicular reconstruction (65.2%) was preferred for operative cases; 66.7% of surgeons would also include distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure. About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to throwing >12 weeks after surgery compared to after 4 to 6 weeks in nonoperatively treated cases. In conclusion, MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in professional pitchers. If operative intervention is required, ligament reconstruction with adjunct distal clavicle excision were the most commonly performed procedures.

Continue to: Despite advancements in surgucal technique...

Despite advancements in surgical technique and improved understanding of the physiology of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the preferred treatment for grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations.1-6 Nonsurgical management has demonstrated return to prior function with fewer complications.7 However, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that surgical intervention is associated with more favorable outcomes8 and should be considered in patients who place high functional demands on their shoulders.9

The reported results on professional athletes in the literature remain ambivalent. Multiple small case reports/series have reported successful nonoperative treatment of elite athletes.10-12 Not surprisingly, McFarland and colleagues13 reported in 1997 that 69% of major league baseball (MLB) team physicians preferred nonoperative treatment for a theoretical starting pitcher sustaining a grade III AC separation 1 week prior to the start of the season. In contrast, reports of an inability to throw at a pre-injury level are equally commonplace.14,15 Nevertheless, all of these studies were limited to small cohorts, as the incidence of grade III AC separations in elite throwing athletes is relatively uncommon.13,16

In this study, we re-evaluated the study performed by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 by surveying all active MLB team orthopedic surgeons. We asked them how they would treat a grade III AC separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher. The physicians were also asked about their personal experience evaluating outcomes in these elite athletes. Given our improved understanding of the anatomy, pathophysiology, and surgical techniques for treating grade III AC separations, we hypothesize that more MLB team physicians would favor operative intervention treatment in professional baseball pitchers, as their vocation places higher demands on their shoulders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire (Appendix A) was distributed to the team physicians of all 30 MLB teams. In addition to surgeon demographics, including age, years in practice, and years of taking care of an MLB team, the initial section of the questionnaire asked orthopedic surgeons how they would treat a theoretical starting pitcher who sustained a grade III AC joint separation of the dominant throwing arm 1 week prior to the start of the season. Physicians who preferred nonoperative treatment were asked whether they would use an injection (and what type), as well as when they would allow the pitcher to start a progressive interval throwing program. Physicians who preferred operative treatment were asked to rank their indications for operating, what procedure they would use (eg, open vs arthroscopic or coracoclavicular ligament repair vs reconstruction), and whether the surgical intervention would include distal clavicle excision. Both groups of physicians were also asked if their preferred treatment would change if the injury were to occur at the end of the season.

The second portion of the questionnaire asked surgeons about their experience treating AC joint separations in both starting pitchers and position players, as well as to describe the long-term outcomes of their preferred treatment, including time to return to full clearance for pitching, whether their patients returned to their prior level of play, and whether these patients had full pain relief. Finally, physicians were asked if any of the nonoperatively treated players ultimately crossed over and required operative intervention.

Continue to: Statistics...

STATISTICS

Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables, and frequencies were used for categorical variables. Linear regression was performed to determine the correlation between the physician’s training or experience in treating AC joint separations and their recommended treatment. Fischer’s exact test/chi-square analysis was used to compare categorical variables. All tests were conducted using 2-sided hypothesis testing with statistical significance set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

A total of 28 MLB team physicians completed the questionnaires from 18 of the 30 MLB teams. The average age of the responders was 50.5 years (range, 34-60 years), with an average of 18.2 years in practice (range, 2-30 years) and 10.8 years (range, 1-24 years) taking care of their current professional baseball team. About 82% of the team physicians completed a sports medicine fellowship. On average, physicians saw 16.6 (range, 5-50) grade III or higher AC joint separations per year, and operated on 4.6 (range, 0-10) per year.

Nonoperative treatment was the preferred treatment for a grade III AC joint separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher for the majority of team physicians (20/28). No correlation was observed between the physician’s age (P = .881), years in practice (P = .915), years taking care of their professional team (P = .989), percentage of practice focused on shoulders (P = .986), number of AC joint injuries seen (P = .325), or number of surgeries performed per year (P = .807) with the team physician’s preferred treatment. Compared to the proportion reported originally by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 (69%), there was no difference in the proportion of team physicians that recommended nonoperative treatment (P = 1).

If treating this injury nonoperatively, 46.4% of physicians would also use an injection, with orthobiologics (eg, platelet-rich plasma) as the most popular choice (Table 1). No consensus was provided on the timeframe to return pitchers back to a progressive interval throwing program; however, 46.67% of physicians would return pitchers 4 to 6 weeks after a nonoperatively treated injury, while 35.7% would return pitchers 7 to 12 weeks after the initial injury.

Table 1. Treatment Preferences of Grade III AC Separation by MLB Team Physicians

Nonoperativea | |

Yes injection | 13 (46.4%) |

Cortisone | 3 (23.1%) |

Orthobiologic | 10 (76.9%) |

Local anesthetic (eg, lidocaine) | 1 (7.7%) |

Intramuscular toradol | 3 (23.1%) |

No injection | 15 (53.6%) |

Operativea | |

Open coracoclavicular ligament repair | 3 (13.0%) |

Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction | 15 (65.2%) |

Arthroscopic reconstruction with graft | 6 (26.1%) |

Arthroscopic repair with implant (ie, tight-rope) | 2 (8.7%) |

Distal clavicle excisionb | 16 (66.7%) |

Would not intervene operatively | 5 (17.9%) |

|

|

aRespondents were allowed to choose more than 1 treatment in each category. bChosen as an adjunct treatment.

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; MLB, major league baseball.

Most physicians (64.3%) cited functional limitations as the most important reason for indicating operative treatment, followed by pain (21.4%), and a deformity (14.3%). About 65% preferred open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. No physician recommended the Weaver-Dunn procedure or use of hardware (eg, hook plate). Of those who preferred an operative intervention, 66.7% would also include a distal clavicle excision, which is significantly higher than the proportion reported by McFarland and colleagues13 (23%, P = .0170). About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to play >12 weeks after operative treatment.

Continue to: If the injury occurred at the end ...

If the injury occurred at the end of the season, 7 of the 20 orthopedists (35%) who recommended nonoperative treatment said they would change to an operative intervention. Eighteen of 28 responders would have the same algorithm for MLB position players. Team physicians were less likely to recommend operative intervention in position players due to less demand on the arm and increased ability to accommodate the injury by altering their throwing mechanics.

Eighteen (64%) of the team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation in his dominant arm, and 11 (39.3%) had treated >1. Collectively, team physicians had treated 15 professional pitchers operatively, and 51 nonoperatively; only 3 patients converted to operative intervention after a failed nonoperative treatment.

Of the pitchers treated operatively, 93.3% (14) of pitchers returned to their prior level of pitching. The 1 patient who failed to return to the same level of pitching retired instead of returning to play. About 80% (12) of the pitchers had full pain relief, and 93.3% (14) had full range of motion (ROM). The pitcher who failed to regain full ROM also had a concomitant rotator cuff repair. The only complication reported from an operative intervention was a pitcher who sustained a coracoid fracture 10 months postoperatively while throwing 100 mph. Of the pitchers treated nonoperatively, 96% returned to their prior level of pitching, 92.2% (47) had full complete pain relief when throwing, and 100% had full ROM. No differences were observed between the proportion of pitchers who returned to their prior level of pitching, regained full ROM, or had full pain relief in the operative and nonoperative groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Outcomes of Treatment of Grade III AC Separation in 58 Professional Baseball Players

| Operative | Nonoperative | P-value |

Return to same level of play | 14/15 (93.3%) | 49/51 (96%) | 0.54 |

Full pain relief | 12/15 (80%) | 47/51 (92.2%) | 0.19 |

Full ROM | 14/15 (93.3%) | 51/51 (100%) | 0.23 |

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; ROM, range of motion.

DISCUSSION

Controversy persists regarding the optimal management of acute grade III AC separations, with the current available evidence potentially suggesting better cosmetic and radiological results but no definite differences in clinical results.1-6,17,18 In the absence of formal clinical practice guidelines, surgeons rely on their own experience or defer to the anecdotal experience of experts in the field. Our initial hypothesis was false in this survey of MLB team physicians taking care of overhead throwing athletes at the highest level. Our results demonstrate that despite improved techniques and an increased understanding of the pathophysiology of AC joint separations, conservative management is still the preferred treatment for acute grade III AC joint separations in professional baseball pitchers. The proportion of team physicians recommending nonoperative treatment in our series was essentially equivalent to the results reported by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997, suggesting that the pendulum continues to favor conservative management initially. This status quo likely reflects both the dearth of literature suggesting a substantial benefit of acute operative repair, as well as the ability to accommodate with conservative measures after most grade III AC injuries, even at the highest level of athletic competition.

These results are also consistent with trends from the last few decades. In the 1970s, the overwhelming preference for treating an acute complete AC joint separation was surgical repair, with Powers and Bach10 reporting in a 1974 survey of 163 chairmen of orthopedic programs around the country that 91.5% advocated surgical treatment. However, surgical preference had reversed by the 1990s. Of the 187 chairmen and 59 team physicians surveyed by Cox19 in 1992, 72% and 86% respectively preferred nonoperative treatment in a theoretical 21-year-old athlete with a grade III AC separation. Nissen and Chatterjee20 reported in 2007 on a survey of all American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine surgeons (N = 577) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education orthopedic program residency directors (N = 87) that >80% of responders preferred conservative measures for this acute injury. The reversal of trends has also been corroborated by recent multicenter trials demonstrating no difference in clinical outcomes between operative and nonoperative treatment of high grade AC joint dislocations, albeit these patients were not all high level overhead throwing athletes.17,18

Continue to: The trends in surgical interventions are notable...

The trends in surgical interventions are notable within the smaller subset of patients who are indicated for operative repair. Use of hardware and primary ligament repair, while popular in the surveys conducted in the 1970s10 and 1990s13 and even present in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, were noticeably absent from our survey results, with the majority of respondents preferring open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. The role of distal clavicle excision has also expanded, from 23% of team physicians recommending it in 199713 to 57% to 59% in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, to 66.7% in our series. This trend is not surprising as several recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have demonstrated that not only do peak graft forces not increase significantly,21 the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior motion at the AC joint following ligament reconstruction is maintained despite resection of the lateral clavicle.22 Additionally, primary distal clavicle excision may prevent the development of post-traumatic arthritis at the AC joint and osteolysis of the distal clavicle as a possible pain generator in the future.23 However, some respondents cautioned against performing a concomitant distal clavicle excision, as some biomechanical data demonstrate that resecting the distal clavicle may lead to increased horizontal translation at the AC joint despite intact superior and posterior AC capsules.24 Professional baseball pitchers may also be more lax and thus prone to more instability. Primary repair or reconstruction may not always lead to complete pre-injury stability in these individuals. This subtle unrecognized instability is hard to diagnosis and may be a persistent source of pain; thus, adding a distal clavicle excision may actually exacerbate the instability.

The nuanced indications for operative intervention, such as the presence of associated lesions were not captured by our survey.25 While most team physicians cited functional limitations as their most common reason for offering surgery, several MLB orthopedic surgeons also commented on evaluating the stability of the AC joint after a grade III injury, akin to the consensus statement from the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) Upper Extremity Committee26 in 2014 that diversified the Rockwood Grade III AC joint separation into its IIIA and IIIB classifications. The ISAKOS recommendations include initial conservative management and a second evaluation (both clinical and radiographic) for grade III lesions 3 to 6 weeks after the injury. However, as professional baseball is an incredibly profitable sport with an annual revenue approaching $9.5 billion27 and pitching salaries up to $32.5 million in 2015, serious financial considerations must be given to players who wish to avoid undergoing delayed surgery.

This study has shortcomings typical of expert opinion papers. The retrospective nature of this study places the data at risk of recall bias. Objective data (eg, terminal ROM, pain relief, and return to play) were obtained from a retrospective chart review; however, no standard documentation or collection method was used given the number of surgeons involved and, thus, conclusions based on treatment outcomes are imperfect. Another major weakness of this survey is the relatively small number of patients and respondents. An a priori power analysis was not available, as this was a retrospective review. A comparative trial will be necessary to definitively support one treatment over another. Assuming a 95% return to play in the nonoperatively treated group, approximately 300 patients would be needed in a prospective 2-armed study with 80% power to detect a 10% reduction in the incidence of return to play using an alpha level of 0.05 and assuming no loss to follow-up. This sample size would be difficult to achieve in this patient population.

However, compared to past series,13 the number of professional baseball players treated by the collective experience of these MLB team physicians is the largest reported to date. As suggested above, the rarity of this condition in elite athletes precludes the ability to have matched controls to definitively determine the optimal treatment, which may explain the lack of difference in the return to play, ROM, and pain relief outcomes. Instead, we can only extrapolate based on the collective anecdotal experience of the MLB team physicians.

CONCLUSION

Despite advances in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, the majority of MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in a professional baseball pitcher. Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction was preferred for those who preferred operative intervention. An increasing number of orthopedic surgeons now consider a distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:38-44. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e318030df83.

- Ceccarelli E, Bondì R, Alviti F, Garofalo R, Miulli F, Padua R. Treatment of acute grade III acromioclavicular dislocation: A lack of evidence. J Orthop Traumatol. 2008;9(2):105-108. doi:10.1007/s10195-008-0013-7.

- Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, Hing CB. Operative versus non-operative management following rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):19-27. doi:10.1007/s10195-011-0127-1.

- Beitzel K, Cote MP, Apostolakos J, et al. Current concepts in the treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):387-397. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.023.

- Korsten K, Gunning AC, Leenen LP. Operative or conservative treatment in patients with rockwood type III acromioclavicular dislocation: a systematic review and update of current literature. Int Orthop. 2014;38(4):831-838. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2143-7.

- Modi CS, Beazley J, Zywiel MG, Lawrence TM, Veillette CJ. Controversies relating to the management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(12):1595-1602. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.31802.

- Reid D, Polson K, Johnson L. Acromioclavicular joint separations grades I-III: a review of the literature and development of best practice guidelines. Sports Med. 2012;42(8):681-696. doi:10.2165/11633460-000000000-00000.

- Farber AJ, Cascio BM, Wilckens JH. Type III acromioclavicular separation: rationale for anatomical reconstruction. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(7):349-355.

- Li X, Ma R, Bedi A, Dines DM, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):73-84. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00734.

- Powers JA, Bach PJ. Acromioclavicular separations. Closed or open treatment? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;104(104):213-223. doi:10.1097/00003086-197410000-00024.

- Glick JM, Milburn LJ, Haggerty JF, Nishimoto D. Dislocated acromioclavicular joint: follow-up study of 35 unreduced acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5(6):264-270. doi:10.1177/036354657700500614.

- Watson ST, Wyland DJ. Return to play after nonoperative management for a severe type III acromioclavicular separation in the throwing shoulder of a collegiate pitcher. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43(1):99-103. doi:10.1080/00913847.2015.1001937.

- McFarland EG, Blivin SJ, Doehring CB, Curl LA, Silberstein C. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations in professional throwing athletes: results of a survey. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(11):771-774.

- Wojtys EM, Nelson G. Conservative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268(268):112-119.

- Galpin RD, Hawkins RJ, Grainger RW. A comparative analysis of operative versus nonoperative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;193(193):150-155. doi:10.1097/00003086-198503000-00020.

- Pallis M, Cameron KL, Svoboda SJ, Owens BD. Epidemiology of acromioclavicular joint injury in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2072-2077. doi:10.1177/0363546512450162.

- Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of nonoperative versus operative treatment of acute acromio-clavicular joint dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(11):479-487. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000437.

- Joukainen A, Kröger H, Niemitukia L, Mäkelä EA, Väätäinen U. Results of operative and nonoperative treatment of rockwood types III and V acromioclavicular joint dislocation: a prospective, randomized trial with an 18- to 20-year follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114560130. doi:10.1177/2325967114560130.

- Cox JS. Current method of treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Orthopedics. 1992;15(9):1041-1044.

- Nissen CW, Chatterjee A. Type III acromioclavicular separation: results of a recent survey on its management. Am J Orthop. 2007;36(2):89-93.

- Kowalsky MS, Kremenic IJ, Orishimo KF, McHugh MP, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ. The effect of distal clavicle excision on in situ graft forces in coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2313-2319. doi:10.1177/0363546510374447.

- Beaver AB, Parks BG, Hinton RY. Biomechanical analysis of distal clavicle excision with acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1684-1688. doi:10.1177/0363546513488750.

- Mumford EB. Acromioclavicular dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:799-802.

- Beitzel K, Sablan N, Chowaniec DM, et al. Sequential resection of the distal clavicle and its effects on horizontal acromioclavicular joint translation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):681-685. doi:10.1177/0363546511428880.

- Arrigoni P, Brady PC, Zottarelli L, et al. Associated lesions requiring additional surgical treatment in grade 3 acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):6-10. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.006.

- Beitzel K, Mazzocca AD, Bak K, et al. ISAKOS upper extremity committee consensus statement on the need for diversification of the rockwood classification for acromioclavicular joint injuries. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):271-278. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.11.005.

- Brown M. MLB sees record revenues for 2015, up $500 million and approaching $9.5 billion. Forbes Web site. http://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2015/12/04/mlb-sees-record-revenu.... Published December 4, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2016.

ABSTRACT

Despite advancements in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the treatment of grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations, particularly in throwing athletes. Twenty-eight major league baseball (MLB) orthopedic team physicians were surveyed to determine their definitive management of a grade III AC separation in the dominant arm of a professional baseball pitcher and their experience treating AC joint separations in starting pitchers and position players. Return-to-play outcomes were also evaluated. Twenty (71.4%) team physicians recommended nonoperative intervention compared to 8 (28.6%) who would have operated acutely. Eighteen (64.3%) team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation; 51 (77.3%) pitchers had been treated nonoperatively compared to 15 (22.7%) operatively. No difference was observed in the proportion of pitchers who returned to the same level of play (P = .54), had full, unrestricted range of motion (P = .23), or had full pain relief (P = .19) between the operatively and nonoperatively treated MLB pitchers. The majority (53.6%) of physicians would not include an injection if the injury was treated nonoperatively. Open coracoclavicular reconstruction (65.2%) was preferred for operative cases; 66.7% of surgeons would also include distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure. About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to throwing >12 weeks after surgery compared to after 4 to 6 weeks in nonoperatively treated cases. In conclusion, MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in professional pitchers. If operative intervention is required, ligament reconstruction with adjunct distal clavicle excision were the most commonly performed procedures.

Continue to: Despite advancements in surgucal technique...

Despite advancements in surgical technique and improved understanding of the physiology of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the preferred treatment for grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations.1-6 Nonsurgical management has demonstrated return to prior function with fewer complications.7 However, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that surgical intervention is associated with more favorable outcomes8 and should be considered in patients who place high functional demands on their shoulders.9

The reported results on professional athletes in the literature remain ambivalent. Multiple small case reports/series have reported successful nonoperative treatment of elite athletes.10-12 Not surprisingly, McFarland and colleagues13 reported in 1997 that 69% of major league baseball (MLB) team physicians preferred nonoperative treatment for a theoretical starting pitcher sustaining a grade III AC separation 1 week prior to the start of the season. In contrast, reports of an inability to throw at a pre-injury level are equally commonplace.14,15 Nevertheless, all of these studies were limited to small cohorts, as the incidence of grade III AC separations in elite throwing athletes is relatively uncommon.13,16

In this study, we re-evaluated the study performed by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 by surveying all active MLB team orthopedic surgeons. We asked them how they would treat a grade III AC separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher. The physicians were also asked about their personal experience evaluating outcomes in these elite athletes. Given our improved understanding of the anatomy, pathophysiology, and surgical techniques for treating grade III AC separations, we hypothesize that more MLB team physicians would favor operative intervention treatment in professional baseball pitchers, as their vocation places higher demands on their shoulders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire (Appendix A) was distributed to the team physicians of all 30 MLB teams. In addition to surgeon demographics, including age, years in practice, and years of taking care of an MLB team, the initial section of the questionnaire asked orthopedic surgeons how they would treat a theoretical starting pitcher who sustained a grade III AC joint separation of the dominant throwing arm 1 week prior to the start of the season. Physicians who preferred nonoperative treatment were asked whether they would use an injection (and what type), as well as when they would allow the pitcher to start a progressive interval throwing program. Physicians who preferred operative treatment were asked to rank their indications for operating, what procedure they would use (eg, open vs arthroscopic or coracoclavicular ligament repair vs reconstruction), and whether the surgical intervention would include distal clavicle excision. Both groups of physicians were also asked if their preferred treatment would change if the injury were to occur at the end of the season.

The second portion of the questionnaire asked surgeons about their experience treating AC joint separations in both starting pitchers and position players, as well as to describe the long-term outcomes of their preferred treatment, including time to return to full clearance for pitching, whether their patients returned to their prior level of play, and whether these patients had full pain relief. Finally, physicians were asked if any of the nonoperatively treated players ultimately crossed over and required operative intervention.

Continue to: Statistics...

STATISTICS

Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables, and frequencies were used for categorical variables. Linear regression was performed to determine the correlation between the physician’s training or experience in treating AC joint separations and their recommended treatment. Fischer’s exact test/chi-square analysis was used to compare categorical variables. All tests were conducted using 2-sided hypothesis testing with statistical significance set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

A total of 28 MLB team physicians completed the questionnaires from 18 of the 30 MLB teams. The average age of the responders was 50.5 years (range, 34-60 years), with an average of 18.2 years in practice (range, 2-30 years) and 10.8 years (range, 1-24 years) taking care of their current professional baseball team. About 82% of the team physicians completed a sports medicine fellowship. On average, physicians saw 16.6 (range, 5-50) grade III or higher AC joint separations per year, and operated on 4.6 (range, 0-10) per year.

Nonoperative treatment was the preferred treatment for a grade III AC joint separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher for the majority of team physicians (20/28). No correlation was observed between the physician’s age (P = .881), years in practice (P = .915), years taking care of their professional team (P = .989), percentage of practice focused on shoulders (P = .986), number of AC joint injuries seen (P = .325), or number of surgeries performed per year (P = .807) with the team physician’s preferred treatment. Compared to the proportion reported originally by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 (69%), there was no difference in the proportion of team physicians that recommended nonoperative treatment (P = 1).

If treating this injury nonoperatively, 46.4% of physicians would also use an injection, with orthobiologics (eg, platelet-rich plasma) as the most popular choice (Table 1). No consensus was provided on the timeframe to return pitchers back to a progressive interval throwing program; however, 46.67% of physicians would return pitchers 4 to 6 weeks after a nonoperatively treated injury, while 35.7% would return pitchers 7 to 12 weeks after the initial injury.

Table 1. Treatment Preferences of Grade III AC Separation by MLB Team Physicians

Nonoperativea | |

Yes injection | 13 (46.4%) |

Cortisone | 3 (23.1%) |

Orthobiologic | 10 (76.9%) |

Local anesthetic (eg, lidocaine) | 1 (7.7%) |

Intramuscular toradol | 3 (23.1%) |

No injection | 15 (53.6%) |

Operativea | |

Open coracoclavicular ligament repair | 3 (13.0%) |

Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction | 15 (65.2%) |

Arthroscopic reconstruction with graft | 6 (26.1%) |

Arthroscopic repair with implant (ie, tight-rope) | 2 (8.7%) |

Distal clavicle excisionb | 16 (66.7%) |

Would not intervene operatively | 5 (17.9%) |

|

|

aRespondents were allowed to choose more than 1 treatment in each category. bChosen as an adjunct treatment.

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; MLB, major league baseball.

Most physicians (64.3%) cited functional limitations as the most important reason for indicating operative treatment, followed by pain (21.4%), and a deformity (14.3%). About 65% preferred open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. No physician recommended the Weaver-Dunn procedure or use of hardware (eg, hook plate). Of those who preferred an operative intervention, 66.7% would also include a distal clavicle excision, which is significantly higher than the proportion reported by McFarland and colleagues13 (23%, P = .0170). About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to play >12 weeks after operative treatment.

Continue to: If the injury occurred at the end ...

If the injury occurred at the end of the season, 7 of the 20 orthopedists (35%) who recommended nonoperative treatment said they would change to an operative intervention. Eighteen of 28 responders would have the same algorithm for MLB position players. Team physicians were less likely to recommend operative intervention in position players due to less demand on the arm and increased ability to accommodate the injury by altering their throwing mechanics.

Eighteen (64%) of the team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation in his dominant arm, and 11 (39.3%) had treated >1. Collectively, team physicians had treated 15 professional pitchers operatively, and 51 nonoperatively; only 3 patients converted to operative intervention after a failed nonoperative treatment.

Of the pitchers treated operatively, 93.3% (14) of pitchers returned to their prior level of pitching. The 1 patient who failed to return to the same level of pitching retired instead of returning to play. About 80% (12) of the pitchers had full pain relief, and 93.3% (14) had full range of motion (ROM). The pitcher who failed to regain full ROM also had a concomitant rotator cuff repair. The only complication reported from an operative intervention was a pitcher who sustained a coracoid fracture 10 months postoperatively while throwing 100 mph. Of the pitchers treated nonoperatively, 96% returned to their prior level of pitching, 92.2% (47) had full complete pain relief when throwing, and 100% had full ROM. No differences were observed between the proportion of pitchers who returned to their prior level of pitching, regained full ROM, or had full pain relief in the operative and nonoperative groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Outcomes of Treatment of Grade III AC Separation in 58 Professional Baseball Players

| Operative | Nonoperative | P-value |

Return to same level of play | 14/15 (93.3%) | 49/51 (96%) | 0.54 |

Full pain relief | 12/15 (80%) | 47/51 (92.2%) | 0.19 |

Full ROM | 14/15 (93.3%) | 51/51 (100%) | 0.23 |

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; ROM, range of motion.

DISCUSSION

Controversy persists regarding the optimal management of acute grade III AC separations, with the current available evidence potentially suggesting better cosmetic and radiological results but no definite differences in clinical results.1-6,17,18 In the absence of formal clinical practice guidelines, surgeons rely on their own experience or defer to the anecdotal experience of experts in the field. Our initial hypothesis was false in this survey of MLB team physicians taking care of overhead throwing athletes at the highest level. Our results demonstrate that despite improved techniques and an increased understanding of the pathophysiology of AC joint separations, conservative management is still the preferred treatment for acute grade III AC joint separations in professional baseball pitchers. The proportion of team physicians recommending nonoperative treatment in our series was essentially equivalent to the results reported by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997, suggesting that the pendulum continues to favor conservative management initially. This status quo likely reflects both the dearth of literature suggesting a substantial benefit of acute operative repair, as well as the ability to accommodate with conservative measures after most grade III AC injuries, even at the highest level of athletic competition.

These results are also consistent with trends from the last few decades. In the 1970s, the overwhelming preference for treating an acute complete AC joint separation was surgical repair, with Powers and Bach10 reporting in a 1974 survey of 163 chairmen of orthopedic programs around the country that 91.5% advocated surgical treatment. However, surgical preference had reversed by the 1990s. Of the 187 chairmen and 59 team physicians surveyed by Cox19 in 1992, 72% and 86% respectively preferred nonoperative treatment in a theoretical 21-year-old athlete with a grade III AC separation. Nissen and Chatterjee20 reported in 2007 on a survey of all American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine surgeons (N = 577) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education orthopedic program residency directors (N = 87) that >80% of responders preferred conservative measures for this acute injury. The reversal of trends has also been corroborated by recent multicenter trials demonstrating no difference in clinical outcomes between operative and nonoperative treatment of high grade AC joint dislocations, albeit these patients were not all high level overhead throwing athletes.17,18

Continue to: The trends in surgical interventions are notable...

The trends in surgical interventions are notable within the smaller subset of patients who are indicated for operative repair. Use of hardware and primary ligament repair, while popular in the surveys conducted in the 1970s10 and 1990s13 and even present in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, were noticeably absent from our survey results, with the majority of respondents preferring open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. The role of distal clavicle excision has also expanded, from 23% of team physicians recommending it in 199713 to 57% to 59% in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, to 66.7% in our series. This trend is not surprising as several recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have demonstrated that not only do peak graft forces not increase significantly,21 the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior motion at the AC joint following ligament reconstruction is maintained despite resection of the lateral clavicle.22 Additionally, primary distal clavicle excision may prevent the development of post-traumatic arthritis at the AC joint and osteolysis of the distal clavicle as a possible pain generator in the future.23 However, some respondents cautioned against performing a concomitant distal clavicle excision, as some biomechanical data demonstrate that resecting the distal clavicle may lead to increased horizontal translation at the AC joint despite intact superior and posterior AC capsules.24 Professional baseball pitchers may also be more lax and thus prone to more instability. Primary repair or reconstruction may not always lead to complete pre-injury stability in these individuals. This subtle unrecognized instability is hard to diagnosis and may be a persistent source of pain; thus, adding a distal clavicle excision may actually exacerbate the instability.

The nuanced indications for operative intervention, such as the presence of associated lesions were not captured by our survey.25 While most team physicians cited functional limitations as their most common reason for offering surgery, several MLB orthopedic surgeons also commented on evaluating the stability of the AC joint after a grade III injury, akin to the consensus statement from the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) Upper Extremity Committee26 in 2014 that diversified the Rockwood Grade III AC joint separation into its IIIA and IIIB classifications. The ISAKOS recommendations include initial conservative management and a second evaluation (both clinical and radiographic) for grade III lesions 3 to 6 weeks after the injury. However, as professional baseball is an incredibly profitable sport with an annual revenue approaching $9.5 billion27 and pitching salaries up to $32.5 million in 2015, serious financial considerations must be given to players who wish to avoid undergoing delayed surgery.

This study has shortcomings typical of expert opinion papers. The retrospective nature of this study places the data at risk of recall bias. Objective data (eg, terminal ROM, pain relief, and return to play) were obtained from a retrospective chart review; however, no standard documentation or collection method was used given the number of surgeons involved and, thus, conclusions based on treatment outcomes are imperfect. Another major weakness of this survey is the relatively small number of patients and respondents. An a priori power analysis was not available, as this was a retrospective review. A comparative trial will be necessary to definitively support one treatment over another. Assuming a 95% return to play in the nonoperatively treated group, approximately 300 patients would be needed in a prospective 2-armed study with 80% power to detect a 10% reduction in the incidence of return to play using an alpha level of 0.05 and assuming no loss to follow-up. This sample size would be difficult to achieve in this patient population.

However, compared to past series,13 the number of professional baseball players treated by the collective experience of these MLB team physicians is the largest reported to date. As suggested above, the rarity of this condition in elite athletes precludes the ability to have matched controls to definitively determine the optimal treatment, which may explain the lack of difference in the return to play, ROM, and pain relief outcomes. Instead, we can only extrapolate based on the collective anecdotal experience of the MLB team physicians.

CONCLUSION

Despite advances in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, the majority of MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in a professional baseball pitcher. Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction was preferred for those who preferred operative intervention. An increasing number of orthopedic surgeons now consider a distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

ABSTRACT

Despite advancements in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the treatment of grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations, particularly in throwing athletes. Twenty-eight major league baseball (MLB) orthopedic team physicians were surveyed to determine their definitive management of a grade III AC separation in the dominant arm of a professional baseball pitcher and their experience treating AC joint separations in starting pitchers and position players. Return-to-play outcomes were also evaluated. Twenty (71.4%) team physicians recommended nonoperative intervention compared to 8 (28.6%) who would have operated acutely. Eighteen (64.3%) team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation; 51 (77.3%) pitchers had been treated nonoperatively compared to 15 (22.7%) operatively. No difference was observed in the proportion of pitchers who returned to the same level of play (P = .54), had full, unrestricted range of motion (P = .23), or had full pain relief (P = .19) between the operatively and nonoperatively treated MLB pitchers. The majority (53.6%) of physicians would not include an injection if the injury was treated nonoperatively. Open coracoclavicular reconstruction (65.2%) was preferred for operative cases; 66.7% of surgeons would also include distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure. About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to throwing >12 weeks after surgery compared to after 4 to 6 weeks in nonoperatively treated cases. In conclusion, MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in professional pitchers. If operative intervention is required, ligament reconstruction with adjunct distal clavicle excision were the most commonly performed procedures.

Continue to: Despite advancements in surgucal technique...

Despite advancements in surgical technique and improved understanding of the physiology of throwing mechanics, controversy persists regarding the preferred treatment for grade III acromioclavicular (AC) joint separations.1-6 Nonsurgical management has demonstrated return to prior function with fewer complications.7 However, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that surgical intervention is associated with more favorable outcomes8 and should be considered in patients who place high functional demands on their shoulders.9

The reported results on professional athletes in the literature remain ambivalent. Multiple small case reports/series have reported successful nonoperative treatment of elite athletes.10-12 Not surprisingly, McFarland and colleagues13 reported in 1997 that 69% of major league baseball (MLB) team physicians preferred nonoperative treatment for a theoretical starting pitcher sustaining a grade III AC separation 1 week prior to the start of the season. In contrast, reports of an inability to throw at a pre-injury level are equally commonplace.14,15 Nevertheless, all of these studies were limited to small cohorts, as the incidence of grade III AC separations in elite throwing athletes is relatively uncommon.13,16

In this study, we re-evaluated the study performed by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 by surveying all active MLB team orthopedic surgeons. We asked them how they would treat a grade III AC separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher. The physicians were also asked about their personal experience evaluating outcomes in these elite athletes. Given our improved understanding of the anatomy, pathophysiology, and surgical techniques for treating grade III AC separations, we hypothesize that more MLB team physicians would favor operative intervention treatment in professional baseball pitchers, as their vocation places higher demands on their shoulders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire (Appendix A) was distributed to the team physicians of all 30 MLB teams. In addition to surgeon demographics, including age, years in practice, and years of taking care of an MLB team, the initial section of the questionnaire asked orthopedic surgeons how they would treat a theoretical starting pitcher who sustained a grade III AC joint separation of the dominant throwing arm 1 week prior to the start of the season. Physicians who preferred nonoperative treatment were asked whether they would use an injection (and what type), as well as when they would allow the pitcher to start a progressive interval throwing program. Physicians who preferred operative treatment were asked to rank their indications for operating, what procedure they would use (eg, open vs arthroscopic or coracoclavicular ligament repair vs reconstruction), and whether the surgical intervention would include distal clavicle excision. Both groups of physicians were also asked if their preferred treatment would change if the injury were to occur at the end of the season.

The second portion of the questionnaire asked surgeons about their experience treating AC joint separations in both starting pitchers and position players, as well as to describe the long-term outcomes of their preferred treatment, including time to return to full clearance for pitching, whether their patients returned to their prior level of play, and whether these patients had full pain relief. Finally, physicians were asked if any of the nonoperatively treated players ultimately crossed over and required operative intervention.

Continue to: Statistics...

STATISTICS

Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables, and frequencies were used for categorical variables. Linear regression was performed to determine the correlation between the physician’s training or experience in treating AC joint separations and their recommended treatment. Fischer’s exact test/chi-square analysis was used to compare categorical variables. All tests were conducted using 2-sided hypothesis testing with statistical significance set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

A total of 28 MLB team physicians completed the questionnaires from 18 of the 30 MLB teams. The average age of the responders was 50.5 years (range, 34-60 years), with an average of 18.2 years in practice (range, 2-30 years) and 10.8 years (range, 1-24 years) taking care of their current professional baseball team. About 82% of the team physicians completed a sports medicine fellowship. On average, physicians saw 16.6 (range, 5-50) grade III or higher AC joint separations per year, and operated on 4.6 (range, 0-10) per year.

Nonoperative treatment was the preferred treatment for a grade III AC joint separation in a starting professional baseball pitcher for the majority of team physicians (20/28). No correlation was observed between the physician’s age (P = .881), years in practice (P = .915), years taking care of their professional team (P = .989), percentage of practice focused on shoulders (P = .986), number of AC joint injuries seen (P = .325), or number of surgeries performed per year (P = .807) with the team physician’s preferred treatment. Compared to the proportion reported originally by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997 (69%), there was no difference in the proportion of team physicians that recommended nonoperative treatment (P = 1).

If treating this injury nonoperatively, 46.4% of physicians would also use an injection, with orthobiologics (eg, platelet-rich plasma) as the most popular choice (Table 1). No consensus was provided on the timeframe to return pitchers back to a progressive interval throwing program; however, 46.67% of physicians would return pitchers 4 to 6 weeks after a nonoperatively treated injury, while 35.7% would return pitchers 7 to 12 weeks after the initial injury.

Table 1. Treatment Preferences of Grade III AC Separation by MLB Team Physicians

Nonoperativea | |

Yes injection | 13 (46.4%) |

Cortisone | 3 (23.1%) |

Orthobiologic | 10 (76.9%) |

Local anesthetic (eg, lidocaine) | 1 (7.7%) |

Intramuscular toradol | 3 (23.1%) |

No injection | 15 (53.6%) |

Operativea | |

Open coracoclavicular ligament repair | 3 (13.0%) |

Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction | 15 (65.2%) |

Arthroscopic reconstruction with graft | 6 (26.1%) |

Arthroscopic repair with implant (ie, tight-rope) | 2 (8.7%) |

Distal clavicle excisionb | 16 (66.7%) |

Would not intervene operatively | 5 (17.9%) |

|

|

aRespondents were allowed to choose more than 1 treatment in each category. bChosen as an adjunct treatment.

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; MLB, major league baseball.

Most physicians (64.3%) cited functional limitations as the most important reason for indicating operative treatment, followed by pain (21.4%), and a deformity (14.3%). About 65% preferred open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. No physician recommended the Weaver-Dunn procedure or use of hardware (eg, hook plate). Of those who preferred an operative intervention, 66.7% would also include a distal clavicle excision, which is significantly higher than the proportion reported by McFarland and colleagues13 (23%, P = .0170). About 90% of physicians would return pitchers to play >12 weeks after operative treatment.

Continue to: If the injury occurred at the end ...

If the injury occurred at the end of the season, 7 of the 20 orthopedists (35%) who recommended nonoperative treatment said they would change to an operative intervention. Eighteen of 28 responders would have the same algorithm for MLB position players. Team physicians were less likely to recommend operative intervention in position players due to less demand on the arm and increased ability to accommodate the injury by altering their throwing mechanics.

Eighteen (64%) of the team physicians had treated at least 1 professional pitcher with a grade III AC separation in his dominant arm, and 11 (39.3%) had treated >1. Collectively, team physicians had treated 15 professional pitchers operatively, and 51 nonoperatively; only 3 patients converted to operative intervention after a failed nonoperative treatment.

Of the pitchers treated operatively, 93.3% (14) of pitchers returned to their prior level of pitching. The 1 patient who failed to return to the same level of pitching retired instead of returning to play. About 80% (12) of the pitchers had full pain relief, and 93.3% (14) had full range of motion (ROM). The pitcher who failed to regain full ROM also had a concomitant rotator cuff repair. The only complication reported from an operative intervention was a pitcher who sustained a coracoid fracture 10 months postoperatively while throwing 100 mph. Of the pitchers treated nonoperatively, 96% returned to their prior level of pitching, 92.2% (47) had full complete pain relief when throwing, and 100% had full ROM. No differences were observed between the proportion of pitchers who returned to their prior level of pitching, regained full ROM, or had full pain relief in the operative and nonoperative groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Outcomes of Treatment of Grade III AC Separation in 58 Professional Baseball Players

| Operative | Nonoperative | P-value |

Return to same level of play | 14/15 (93.3%) | 49/51 (96%) | 0.54 |

Full pain relief | 12/15 (80%) | 47/51 (92.2%) | 0.19 |

Full ROM | 14/15 (93.3%) | 51/51 (100%) | 0.23 |

Abbreviations: AC, acromioclavicular; ROM, range of motion.

DISCUSSION

Controversy persists regarding the optimal management of acute grade III AC separations, with the current available evidence potentially suggesting better cosmetic and radiological results but no definite differences in clinical results.1-6,17,18 In the absence of formal clinical practice guidelines, surgeons rely on their own experience or defer to the anecdotal experience of experts in the field. Our initial hypothesis was false in this survey of MLB team physicians taking care of overhead throwing athletes at the highest level. Our results demonstrate that despite improved techniques and an increased understanding of the pathophysiology of AC joint separations, conservative management is still the preferred treatment for acute grade III AC joint separations in professional baseball pitchers. The proportion of team physicians recommending nonoperative treatment in our series was essentially equivalent to the results reported by McFarland and colleagues13 in 1997, suggesting that the pendulum continues to favor conservative management initially. This status quo likely reflects both the dearth of literature suggesting a substantial benefit of acute operative repair, as well as the ability to accommodate with conservative measures after most grade III AC injuries, even at the highest level of athletic competition.

These results are also consistent with trends from the last few decades. In the 1970s, the overwhelming preference for treating an acute complete AC joint separation was surgical repair, with Powers and Bach10 reporting in a 1974 survey of 163 chairmen of orthopedic programs around the country that 91.5% advocated surgical treatment. However, surgical preference had reversed by the 1990s. Of the 187 chairmen and 59 team physicians surveyed by Cox19 in 1992, 72% and 86% respectively preferred nonoperative treatment in a theoretical 21-year-old athlete with a grade III AC separation. Nissen and Chatterjee20 reported in 2007 on a survey of all American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine surgeons (N = 577) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education orthopedic program residency directors (N = 87) that >80% of responders preferred conservative measures for this acute injury. The reversal of trends has also been corroborated by recent multicenter trials demonstrating no difference in clinical outcomes between operative and nonoperative treatment of high grade AC joint dislocations, albeit these patients were not all high level overhead throwing athletes.17,18

Continue to: The trends in surgical interventions are notable...

The trends in surgical interventions are notable within the smaller subset of patients who are indicated for operative repair. Use of hardware and primary ligament repair, while popular in the surveys conducted in the 1970s10 and 1990s13 and even present in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, were noticeably absent from our survey results, with the majority of respondents preferring open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. The role of distal clavicle excision has also expanded, from 23% of team physicians recommending it in 199713 to 57% to 59% in Nissen and Chatterjee’s20 2007 survey, to 66.7% in our series. This trend is not surprising as several recent cadaveric biomechanical studies have demonstrated that not only do peak graft forces not increase significantly,21 the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior motion at the AC joint following ligament reconstruction is maintained despite resection of the lateral clavicle.22 Additionally, primary distal clavicle excision may prevent the development of post-traumatic arthritis at the AC joint and osteolysis of the distal clavicle as a possible pain generator in the future.23 However, some respondents cautioned against performing a concomitant distal clavicle excision, as some biomechanical data demonstrate that resecting the distal clavicle may lead to increased horizontal translation at the AC joint despite intact superior and posterior AC capsules.24 Professional baseball pitchers may also be more lax and thus prone to more instability. Primary repair or reconstruction may not always lead to complete pre-injury stability in these individuals. This subtle unrecognized instability is hard to diagnosis and may be a persistent source of pain; thus, adding a distal clavicle excision may actually exacerbate the instability.

The nuanced indications for operative intervention, such as the presence of associated lesions were not captured by our survey.25 While most team physicians cited functional limitations as their most common reason for offering surgery, several MLB orthopedic surgeons also commented on evaluating the stability of the AC joint after a grade III injury, akin to the consensus statement from the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) Upper Extremity Committee26 in 2014 that diversified the Rockwood Grade III AC joint separation into its IIIA and IIIB classifications. The ISAKOS recommendations include initial conservative management and a second evaluation (both clinical and radiographic) for grade III lesions 3 to 6 weeks after the injury. However, as professional baseball is an incredibly profitable sport with an annual revenue approaching $9.5 billion27 and pitching salaries up to $32.5 million in 2015, serious financial considerations must be given to players who wish to avoid undergoing delayed surgery.

This study has shortcomings typical of expert opinion papers. The retrospective nature of this study places the data at risk of recall bias. Objective data (eg, terminal ROM, pain relief, and return to play) were obtained from a retrospective chart review; however, no standard documentation or collection method was used given the number of surgeons involved and, thus, conclusions based on treatment outcomes are imperfect. Another major weakness of this survey is the relatively small number of patients and respondents. An a priori power analysis was not available, as this was a retrospective review. A comparative trial will be necessary to definitively support one treatment over another. Assuming a 95% return to play in the nonoperatively treated group, approximately 300 patients would be needed in a prospective 2-armed study with 80% power to detect a 10% reduction in the incidence of return to play using an alpha level of 0.05 and assuming no loss to follow-up. This sample size would be difficult to achieve in this patient population.

However, compared to past series,13 the number of professional baseball players treated by the collective experience of these MLB team physicians is the largest reported to date. As suggested above, the rarity of this condition in elite athletes precludes the ability to have matched controls to definitively determine the optimal treatment, which may explain the lack of difference in the return to play, ROM, and pain relief outcomes. Instead, we can only extrapolate based on the collective anecdotal experience of the MLB team physicians.

CONCLUSION

Despite advances in surgical technique and understanding of throwing mechanics, the majority of MLB team physicians preferred nonoperative management for an acute grade III AC joint separation in a professional baseball pitcher. Open coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction was preferred for those who preferred operative intervention. An increasing number of orthopedic surgeons now consider a distal clavicle excision as an adjunct procedure.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:38-44. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e318030df83.

- Ceccarelli E, Bondì R, Alviti F, Garofalo R, Miulli F, Padua R. Treatment of acute grade III acromioclavicular dislocation: A lack of evidence. J Orthop Traumatol. 2008;9(2):105-108. doi:10.1007/s10195-008-0013-7.

- Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, Hing CB. Operative versus non-operative management following rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):19-27. doi:10.1007/s10195-011-0127-1.

- Beitzel K, Cote MP, Apostolakos J, et al. Current concepts in the treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):387-397. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.023.

- Korsten K, Gunning AC, Leenen LP. Operative or conservative treatment in patients with rockwood type III acromioclavicular dislocation: a systematic review and update of current literature. Int Orthop. 2014;38(4):831-838. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2143-7.

- Modi CS, Beazley J, Zywiel MG, Lawrence TM, Veillette CJ. Controversies relating to the management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(12):1595-1602. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.31802.

- Reid D, Polson K, Johnson L. Acromioclavicular joint separations grades I-III: a review of the literature and development of best practice guidelines. Sports Med. 2012;42(8):681-696. doi:10.2165/11633460-000000000-00000.

- Farber AJ, Cascio BM, Wilckens JH. Type III acromioclavicular separation: rationale for anatomical reconstruction. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(7):349-355.

- Li X, Ma R, Bedi A, Dines DM, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):73-84. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00734.

- Powers JA, Bach PJ. Acromioclavicular separations. Closed or open treatment? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;104(104):213-223. doi:10.1097/00003086-197410000-00024.

- Glick JM, Milburn LJ, Haggerty JF, Nishimoto D. Dislocated acromioclavicular joint: follow-up study of 35 unreduced acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5(6):264-270. doi:10.1177/036354657700500614.

- Watson ST, Wyland DJ. Return to play after nonoperative management for a severe type III acromioclavicular separation in the throwing shoulder of a collegiate pitcher. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43(1):99-103. doi:10.1080/00913847.2015.1001937.

- McFarland EG, Blivin SJ, Doehring CB, Curl LA, Silberstein C. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations in professional throwing athletes: results of a survey. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(11):771-774.

- Wojtys EM, Nelson G. Conservative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268(268):112-119.

- Galpin RD, Hawkins RJ, Grainger RW. A comparative analysis of operative versus nonoperative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;193(193):150-155. doi:10.1097/00003086-198503000-00020.

- Pallis M, Cameron KL, Svoboda SJ, Owens BD. Epidemiology of acromioclavicular joint injury in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2072-2077. doi:10.1177/0363546512450162.

- Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of nonoperative versus operative treatment of acute acromio-clavicular joint dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(11):479-487. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000437.

- Joukainen A, Kröger H, Niemitukia L, Mäkelä EA, Väätäinen U. Results of operative and nonoperative treatment of rockwood types III and V acromioclavicular joint dislocation: a prospective, randomized trial with an 18- to 20-year follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114560130. doi:10.1177/2325967114560130.

- Cox JS. Current method of treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Orthopedics. 1992;15(9):1041-1044.

- Nissen CW, Chatterjee A. Type III acromioclavicular separation: results of a recent survey on its management. Am J Orthop. 2007;36(2):89-93.

- Kowalsky MS, Kremenic IJ, Orishimo KF, McHugh MP, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ. The effect of distal clavicle excision on in situ graft forces in coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2313-2319. doi:10.1177/0363546510374447.

- Beaver AB, Parks BG, Hinton RY. Biomechanical analysis of distal clavicle excision with acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1684-1688. doi:10.1177/0363546513488750.

- Mumford EB. Acromioclavicular dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:799-802.

- Beitzel K, Sablan N, Chowaniec DM, et al. Sequential resection of the distal clavicle and its effects on horizontal acromioclavicular joint translation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):681-685. doi:10.1177/0363546511428880.

- Arrigoni P, Brady PC, Zottarelli L, et al. Associated lesions requiring additional surgical treatment in grade 3 acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):6-10. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.006.

- Beitzel K, Mazzocca AD, Bak K, et al. ISAKOS upper extremity committee consensus statement on the need for diversification of the rockwood classification for acromioclavicular joint injuries. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):271-278. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.11.005.

- Brown M. MLB sees record revenues for 2015, up $500 million and approaching $9.5 billion. Forbes Web site. http://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2015/12/04/mlb-sees-record-revenu.... Published December 4, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2016.

- Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:38-44. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e318030df83.

- Ceccarelli E, Bondì R, Alviti F, Garofalo R, Miulli F, Padua R. Treatment of acute grade III acromioclavicular dislocation: A lack of evidence. J Orthop Traumatol. 2008;9(2):105-108. doi:10.1007/s10195-008-0013-7.

- Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, Hing CB. Operative versus non-operative management following rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):19-27. doi:10.1007/s10195-011-0127-1.

- Beitzel K, Cote MP, Apostolakos J, et al. Current concepts in the treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):387-397. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.023.

- Korsten K, Gunning AC, Leenen LP. Operative or conservative treatment in patients with rockwood type III acromioclavicular dislocation: a systematic review and update of current literature. Int Orthop. 2014;38(4):831-838. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2143-7.

- Modi CS, Beazley J, Zywiel MG, Lawrence TM, Veillette CJ. Controversies relating to the management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(12):1595-1602. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.31802.

- Reid D, Polson K, Johnson L. Acromioclavicular joint separations grades I-III: a review of the literature and development of best practice guidelines. Sports Med. 2012;42(8):681-696. doi:10.2165/11633460-000000000-00000.

- Farber AJ, Cascio BM, Wilckens JH. Type III acromioclavicular separation: rationale for anatomical reconstruction. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(7):349-355.

- Li X, Ma R, Bedi A, Dines DM, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):73-84. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00734.

- Powers JA, Bach PJ. Acromioclavicular separations. Closed or open treatment? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;104(104):213-223. doi:10.1097/00003086-197410000-00024.

- Glick JM, Milburn LJ, Haggerty JF, Nishimoto D. Dislocated acromioclavicular joint: follow-up study of 35 unreduced acromioclavicular dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5(6):264-270. doi:10.1177/036354657700500614.

- Watson ST, Wyland DJ. Return to play after nonoperative management for a severe type III acromioclavicular separation in the throwing shoulder of a collegiate pitcher. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43(1):99-103. doi:10.1080/00913847.2015.1001937.

- McFarland EG, Blivin SJ, Doehring CB, Curl LA, Silberstein C. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations in professional throwing athletes: results of a survey. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(11):771-774.

- Wojtys EM, Nelson G. Conservative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268(268):112-119.

- Galpin RD, Hawkins RJ, Grainger RW. A comparative analysis of operative versus nonoperative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;193(193):150-155. doi:10.1097/00003086-198503000-00020.

- Pallis M, Cameron KL, Svoboda SJ, Owens BD. Epidemiology of acromioclavicular joint injury in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2072-2077. doi:10.1177/0363546512450162.

- Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of nonoperative versus operative treatment of acute acromio-clavicular joint dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(11):479-487. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000437.

- Joukainen A, Kröger H, Niemitukia L, Mäkelä EA, Väätäinen U. Results of operative and nonoperative treatment of rockwood types III and V acromioclavicular joint dislocation: a prospective, randomized trial with an 18- to 20-year follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114560130. doi:10.1177/2325967114560130.

- Cox JS. Current method of treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Orthopedics. 1992;15(9):1041-1044.

- Nissen CW, Chatterjee A. Type III acromioclavicular separation: results of a recent survey on its management. Am J Orthop. 2007;36(2):89-93.

- Kowalsky MS, Kremenic IJ, Orishimo KF, McHugh MP, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ. The effect of distal clavicle excision on in situ graft forces in coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2313-2319. doi:10.1177/0363546510374447.

- Beaver AB, Parks BG, Hinton RY. Biomechanical analysis of distal clavicle excision with acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1684-1688. doi:10.1177/0363546513488750.

- Mumford EB. Acromioclavicular dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23:799-802.

- Beitzel K, Sablan N, Chowaniec DM, et al. Sequential resection of the distal clavicle and its effects on horizontal acromioclavicular joint translation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):681-685. doi:10.1177/0363546511428880.

- Arrigoni P, Brady PC, Zottarelli L, et al. Associated lesions requiring additional surgical treatment in grade 3 acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):6-10. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.006.

- Beitzel K, Mazzocca AD, Bak K, et al. ISAKOS upper extremity committee consensus statement on the need for diversification of the rockwood classification for acromioclavicular joint injuries. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):271-278. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.11.005.

- Brown M. MLB sees record revenues for 2015, up $500 million and approaching $9.5 billion. Forbes Web site. http://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2015/12/04/mlb-sees-record-revenu.... Published December 4, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2016.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- There was no difference in return to previous level of play between professional pitchers treated nonoperatively and operatively for grade III AC separation.

- MLB team physicians prefer nonoperative management for acute grade III AC joint separation in professional pitchers.

- The majority of MLB physicians do not use injections for nonoperative treatment of grade III AC separations; however, use of orthobiologics (eg, PRP) is becoming more commonplace.

- Persistent functional limitations and pain are the most common surgical indications for treatment of grade III AC separation in high level throwing athletes.

- If operative intervention is indicated for grade III AC separation, open coracoclavicular reconstruction and adjunct distal clavicle excision are preferred by most MLB team physicians.

Patient-Specific Guides/Instrumentation in Shoulder Arthroplasty

ABSTRACT

Optimal outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty RSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple cadaver studies have demonstrated improved accuracy of implant positioning with use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation compared to traditional methods. At this time, there are 3 commercially available single use patient-specific instrumentation systems and 1 commercially available reusable patient-specific instrumentation system. Currently though, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research has been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-dimensional planning software. Future work is necessary to elucidate the ideal indications for the use of patient-specific guides and instrumentation, but it is likely, particularly in the setting of advanced glenoid deformity, that these systems will improve a surgeon's ability to put the implant in the best position possible.

Continue to: Optimal functional recovery...

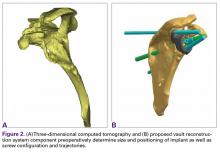

Optimal functional recovery and implant longevity following both total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) depend, in large part, on proper placement of the glenoid component. Glenoid component malpositioning has an adverse effect on shoulder stability, range of motion (ROM), impingement, and glenoid implant longevity.

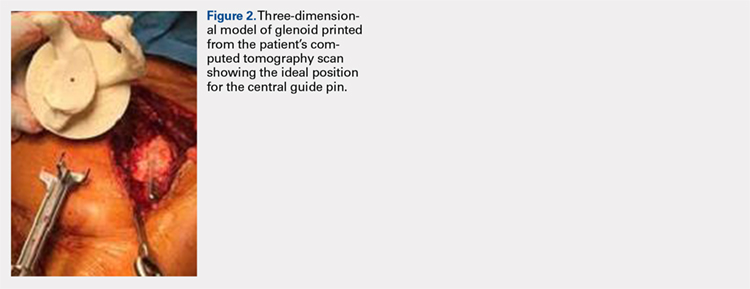

Traditionally, glenoid component positioning has been done manually by the surgeons based on their review of preoperative films and knowledge of glenoid anatomy. Anatomic studies have demonstrated high individual variability in the version of the native glenoid, thus making ideal placement of the initial glenoid guide pin difficult using standard guide pin guides.1

The following 2 methods have been described for improving the accuracy of glenoid guide pin insertion and subsequent glenoid implant placement: (1) computerized navigation and (2) patient-specific guides/instrumentation. Although navigated shoulder systems have demonstrated improved accuracy in glenoid placement compared with traditional methods, navigated systems require often large and expensive systems for implementation. The majority of them also require placement of guide pins or arrays on scapular bony landmarks, likely leading to an increase in operative time and possible iatrogenic complications, including fracture and pin site infections.

This review focuses on the use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation in shoulder arthroplasty. This includes the topic of proper glenoid and glenosphere placement as well as patient-specific guides/instrumentation and their accuracy.

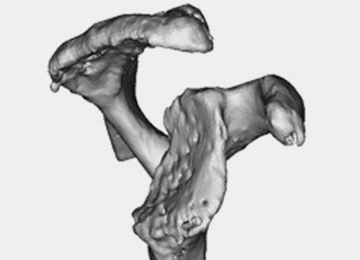

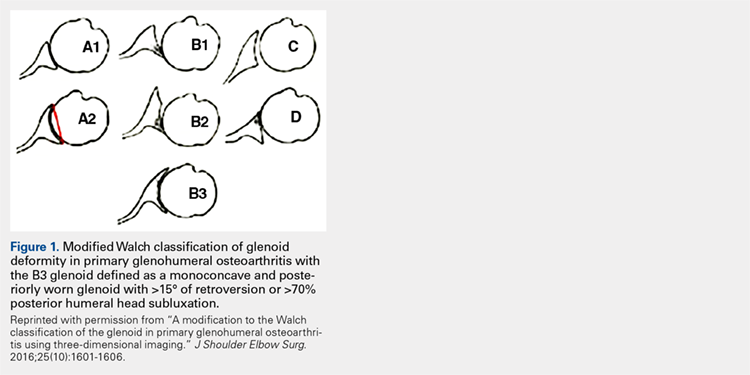

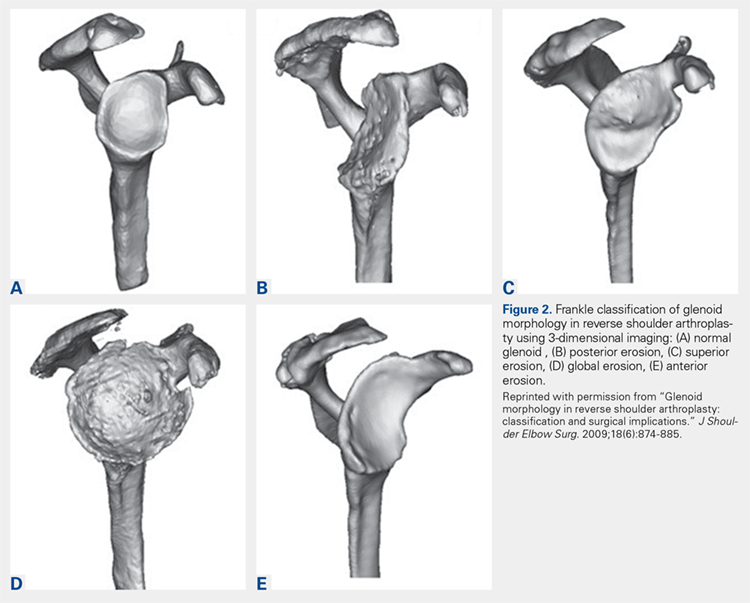

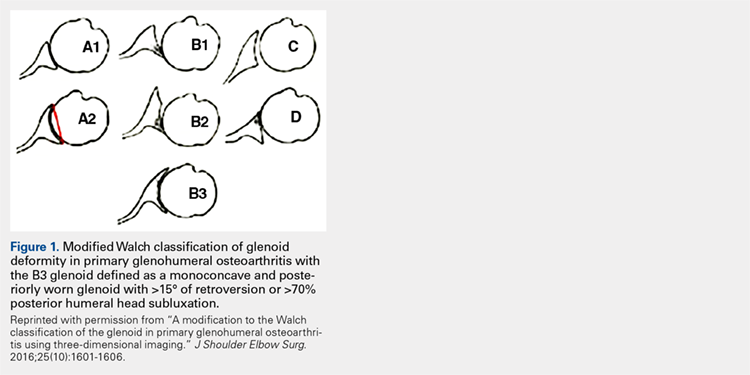

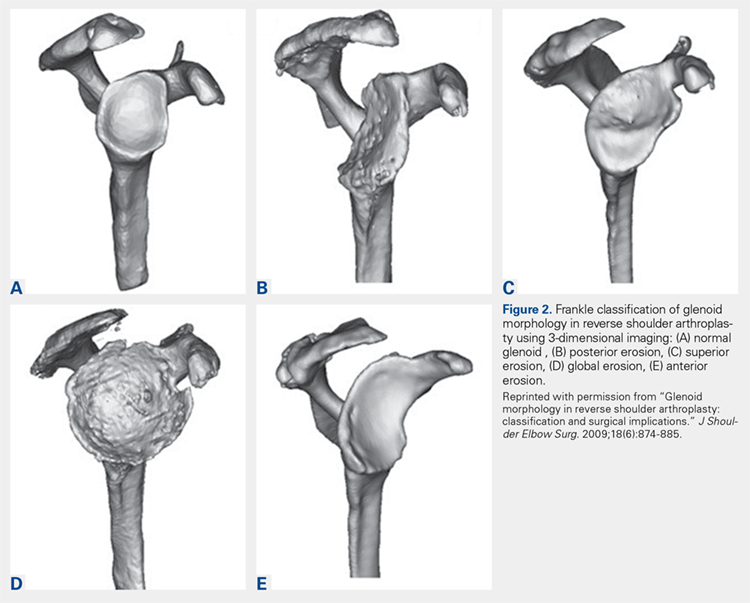

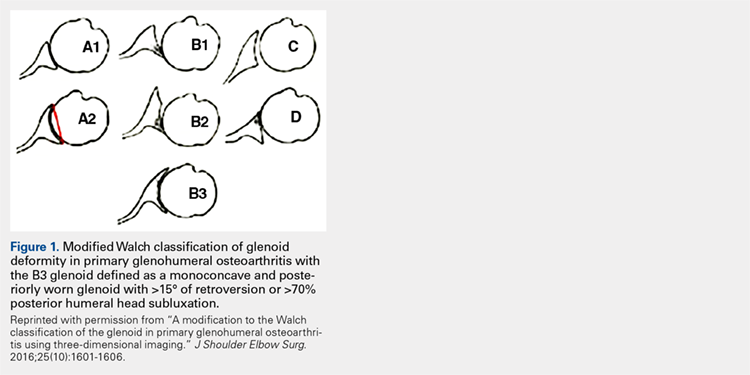

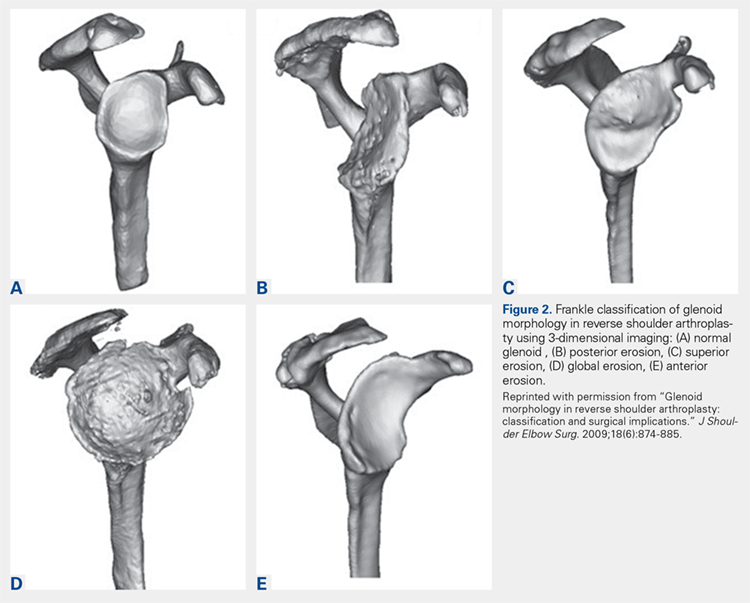

GLENOID PLACEMENT

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis is the most common indication for TSA2 and commonly results in glenoid deformity. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of 45 arthritic shoulders and 19 normal shoulders, Mullaji and colleagues3 reported that the anteroposterior dimensions of the glenoid were increased by an average of 5 mm to 8 mm in osteoarthritic shoulders and by an average of 6 mm in rheumatoid arthritic shoulders compared to those in normal shoulders. A retrospective review of serial CT scans performed preoperatively on 113 osteoarthritic shoulders by Walch and colleagues4 demonstrated an average retroversion of 16°, and it has been the basis for the commonly used Walch classification of glenoid wear in osteoarthritis. Increased glenoid wear and increased glenoid retroversion make the proper restoration of glenoid version, inclination, and offset during shoulder arthroplasty more difficult and lead to increased glenoid component malpositioning.

Continue to: The ideal placement of the glenoid...