User login

Katie Lennon is editor of MDedge's Family Practice News and Internal Medicine News. She has also served as editor of CHEST Physician; a staff writer for Financial Times publications; and a reporter for the Princeton Packet, Ocean County Observer, and South Bend Tribune. She is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Ind. Follow her on Twitter @KatieWLennon.

Editor’s note on 50th Anniversary series

While this is the last piece in a series, my intention is for it to read more like the opening of a new book on family medicine, rather than an ending to a story about the specialty.

April Lockley, DO, represents a new generation of family physicians who began their careers in the 21st century, and she is hopeful that the experiences of practicing family medicine and being the patient of a family physician will change in several ways.

Among her desires for the future, is to be able to write a prescription for a medication or physical therapy to a patient who is able “to fill the prescription without having to worry about the financial implications of paying for it,” she writes. She also hopes “patients can seek out care without the fear of discrimination or racism through an increasingly diverse work force.”

In her article, Dr. Lockley both expresses how she wants family medicine to change and what she already finds satisfying about being a family physician.

I hope you enjoyed reading about the professional journeys of Dr. Lockley and other family physicians who have written commentaries or interviewed for articles in Family Practice News’ 50th Anniversary series this year.

To revisit any of these articles, go to the 50th Anniversary bucket on mdedge.com/familymedicine.

Thank you for continuing to read Family Practice News, and I hope to celebrate more milestones with you in the future.

[email protected]

While this is the last piece in a series, my intention is for it to read more like the opening of a new book on family medicine, rather than an ending to a story about the specialty.

April Lockley, DO, represents a new generation of family physicians who began their careers in the 21st century, and she is hopeful that the experiences of practicing family medicine and being the patient of a family physician will change in several ways.

Among her desires for the future, is to be able to write a prescription for a medication or physical therapy to a patient who is able “to fill the prescription without having to worry about the financial implications of paying for it,” she writes. She also hopes “patients can seek out care without the fear of discrimination or racism through an increasingly diverse work force.”

In her article, Dr. Lockley both expresses how she wants family medicine to change and what she already finds satisfying about being a family physician.

I hope you enjoyed reading about the professional journeys of Dr. Lockley and other family physicians who have written commentaries or interviewed for articles in Family Practice News’ 50th Anniversary series this year.

To revisit any of these articles, go to the 50th Anniversary bucket on mdedge.com/familymedicine.

Thank you for continuing to read Family Practice News, and I hope to celebrate more milestones with you in the future.

[email protected]

While this is the last piece in a series, my intention is for it to read more like the opening of a new book on family medicine, rather than an ending to a story about the specialty.

April Lockley, DO, represents a new generation of family physicians who began their careers in the 21st century, and she is hopeful that the experiences of practicing family medicine and being the patient of a family physician will change in several ways.

Among her desires for the future, is to be able to write a prescription for a medication or physical therapy to a patient who is able “to fill the prescription without having to worry about the financial implications of paying for it,” she writes. She also hopes “patients can seek out care without the fear of discrimination or racism through an increasingly diverse work force.”

In her article, Dr. Lockley both expresses how she wants family medicine to change and what she already finds satisfying about being a family physician.

I hope you enjoyed reading about the professional journeys of Dr. Lockley and other family physicians who have written commentaries or interviewed for articles in Family Practice News’ 50th Anniversary series this year.

To revisit any of these articles, go to the 50th Anniversary bucket on mdedge.com/familymedicine.

Thank you for continuing to read Family Practice News, and I hope to celebrate more milestones with you in the future.

[email protected]

‘Residents’ Viewpoint’ revisited

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

Patient contact with primary care physicians declines in study

––

The reasons for this less frequent contact and the ramifications for patients and doctors practicing primary care are unclear, according to various experts. But some offered possible explanations for the changes, with patients’ increased participation in high deductible plans and shortages in primary care physicians (PCPs) being among the most often cited.

The findings, which were published online Jan. 11 in Annals of Family Medicine, were derived from researchers using a repeated cross-sectional study of the 2002-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to characterize trends in primary care use. This survey, which collected information about medical care utilization from individuals and families, included 243,919 participants who were interviewed five times over 2 years. The authors defined primary care physician contact as “in-person visit or contact with a primary care physician (primarily telephone calls) with a reported specialty of family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, general pediatrics, or general practice physician.” According to the paper, “the proportion of individuals with any primary care physician contact was determined for both the population and by age group using logistic regression models,” and negative binomial regression models were used to determine the number of contacts among people with visits during 2-year periods.

The study authors, Michael E. Johansen, MD, MS, and Joshua D. Niforatos, MD, MTS, said their study suggests that previously reported decreases in primary care contact was caused by fewer contacts per patient “as opposed to an absolute decrease in the number of patients in contact with primary care.”

Harold B. Betton, MD, PhD, who practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark., questioned this claim.

“In my reading, the authors concluded that people are seeing their primary care physicians fewer times than in the past, which suggests something is happening,” Dr. Betton said in an interview. “The fact that fewer visits are occurring may be due to multiple things, i.e., urgent care visits, visits to physician extenders – physician assistants and advanced practice nurses – or emergency room visits.”

"The paper draws observational conclusions and I fail to see the merit in the observation without knowing what the respondents were asked and not asked," he added.

Other primary care physicians suggested patients’ participation in alternative pay models and high-deductible plans have played a factor in the declines.

“Most of us have gone from fee-for-service, volume-based care to more value-based care,” Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. The data reflect that trend, “whereas we were rewarded more for the number of people we were seeing, now we are trying to get towards more of the value that we provide,” suggested Dr. Stewart, who also practices family medicine with Cooperative Health in Columbia, S.C.

“Given the rise of high-deductible plans and copays, it is not surprising that younger patients, a generally healthier population, might well decrease their visits to a primary care physician. I would suspect that data for patients over 50 might well be different,” William E. Golden, MD, who is medical director at the Arkansas Department of Health & Human Services, noted in an interview.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, also cited greater participation in high-deductible plans as a possible factor that could be leading some patients to forgo visits, as well as increased financial insecurity, rendering it expensive to have the visit and also to take time from work for the visit.

“I would wonder if some of this is also due to how overloaded most primary care offices are so that instead of stopping accepting new patients or shedding patients, it is just harder for existing patients to be seen,” said Dr. Barrett, who is a general internist and associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. “Some of this could be from administrative burden – 2 hours per hour of clinic – and consequently reducing clinical time,” continued Dr. Barrett, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, which is affiliated with Family Practice News.

Other experts pointed to data showing an insufficient supply of PCPs as a potential explanation for the new study’s findings. The Health Resources and Services Organization, for example, reported that 83 million Americans live in primary care “health professional shortage areas,” as of Jan. 24, 2021, on their website.

New data

“The rate of any contact with a [PCP] for patients in the population over multiple 2-year periods decreased by 2.5% over the study period (adjusted odds ratio, 0.99 per panel; 95% [confidence interval], 0.98-0.99; P < .001),” wrote Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos. The rate of contact for patients aged 18-39 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < .001) and patients aged 40-64 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.99-1.00; P = .002), specifically, also fell. These decreased contact rates correspond “to a predicted cumulative 5% absolute decrease for the younger group and a 2% absolute decrease for the older group,” the authors added.

“The number of contacts with a [PCP] decreased among individuals with any contact by 0.5 contacts over 2 years (P < .001). A decrease in the number of [PCP] contacts was observed across all age groups (P < .001 for all), with the largest absolute decrease among individuals with higher contact rates (aged less than 4 years and aged greater than 64 years),” according to the paper.

Outlook for PCPs

Physicians questioned about how concerning these data are for the future of PCPs and their ability to keep their practices running were hesitant to speculate, because of uncertainty about the causes of the study findings.

“A quote from the paper indicates that the respondents were interviewed five times over 2 years; however, without a copy of the questionnaire it is impossible to know what they were asked and not asked,” said Dr. Betton, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News and runs his own private practice. “In addition, it is impossible for the reader to know whether they understood what a primary care physician was to do.

“To draw a conclusion that PCP visits are falling off per patient per provider is only helpful if patients are opting out of the primary care model of practice and opting in for point-of-care [urgent] care,” Dr. Betton added.

Internist Alan Nelson, MD, said he was also undecided about whether the findings of the study are good or bad news for the physician specialty of primary care.

“Similar findings have been reported by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. They certainly merit further investigation,” noted Dr. Nelson, who is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. “Is it because primary care physicians are too busy to see additional patients? Is it because nonphysician practitioners seem to be more caring? Should residency training be modified, and if so, how? In the meantime, I would not be surprised if the trend continues, at least in the short term.”

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the Primary Care Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that advocates to strengthen primary care and make it more responsive to patient needs and preferences, on the other hand, reacted with a concerned outlook for primary care.

This study and others show that “the U.S. health care system is moving away from a primary care orientation, and that is concerning,” Ms. Greiner said in an interview. “Health systems that are more oriented toward primary care have better population health outcomes, do better on measures of equity across different population groups, and are less costly.”

Authors’ take

“Future research is needed to determine whether fewer contacts per patient resulted in clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across disease processes,” wrote Dr. Johansen, who is a family medicine doctor affiliated with OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant in Columbus and with the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University, Dublin, and Dr. Niforatos, who is affiliated with the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The study’s limitations included reliance on self-reported categorization of PCP versus specialty care physician contact, insufficient accounting for nurse practitioner and physician assistant contact, and improved contact reporting having started in 2013, they said.

How to grow patient contact

For those PCPs looking to grow their visits and patient contact, Dr. Golden suggested they strengthen their medical home model in their practice.

“Medical home models help and transform practice operations. The Arkansas model is a multipayer model – private, Medicaid and CPC+ (Medicare),” said Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. It includes community-based doctors, not Federally Qualified Health Centers, and “requires 24/7 live voice access that promotes regular contact with patients and can reduce dependency on ER and urgent care center visits.”

“Greater use of patient portals and email communications facilitate access and patient engagement with their PCP,” Dr. Golden explained.

“Over the last 6 years, the Arkansas [patient-centered medical home] initiatives have altered culture and made our practice sites stronger to withstand COVID and other challenges. As our sites became more patient centered and incorporated behavioral health options, patients perceived greater value in the functionality of primary care” he said.

Dr. Barrett proposed PCPs participate in team-based care “for professional sustainability and also for patients to continue to experience high-quality, person-centered care.” She added that “telemedicine can also help practices maintain and increase patients, as it can lessen burden on patients and clinicians – if it is done right.”

“More flexible clinic hours is also key – after usual business hours and on weekends – but I would recommend in lieu of usual weekday hours and for those who can make it work with their family and other duties,” Dr. Barrett said. “Evening or Saturday morning clinic isn’t an option for everyone, but it is an option for many some of the time, and it would be great for access to care if it were available in more locations.”

Pandemic effect

The data examined by Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos predates the pandemic, but PCPs interviewed by this news organization have seen declining patient contact occur in 2020 as well.

In fact, a survey of 1,485 mostly physician primary care practitioners that began after the pandemic onset found that 43% of participants have fewer in-person visits, motivated largely by patient preferences (66%) and safety concerns (74%). This ongoing survey, which was conducted by the Larry Green Center in partnership with the Primary Care Collaborative, also indicated that, while 25% of participants saw a total increase in patient volume, more than half of primary care practitioners reported that chronic and wellness visits are down, 53% and 55%, respectively.

“Sometimes we have to go looking for our patients when we have not seen them in a while,” Dr. Stewart noted. “We saw that with COVID because people were fearful of coming into our offices, and we had to have some outreach.”

The study authors had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Barrett, Dr. Betton, Dr. Golden, Dr. Nelson, and Dr. Stewart had no relevant disclosures.

Jake Remaly contributed to this article.

––

The reasons for this less frequent contact and the ramifications for patients and doctors practicing primary care are unclear, according to various experts. But some offered possible explanations for the changes, with patients’ increased participation in high deductible plans and shortages in primary care physicians (PCPs) being among the most often cited.

The findings, which were published online Jan. 11 in Annals of Family Medicine, were derived from researchers using a repeated cross-sectional study of the 2002-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to characterize trends in primary care use. This survey, which collected information about medical care utilization from individuals and families, included 243,919 participants who were interviewed five times over 2 years. The authors defined primary care physician contact as “in-person visit or contact with a primary care physician (primarily telephone calls) with a reported specialty of family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, general pediatrics, or general practice physician.” According to the paper, “the proportion of individuals with any primary care physician contact was determined for both the population and by age group using logistic regression models,” and negative binomial regression models were used to determine the number of contacts among people with visits during 2-year periods.

The study authors, Michael E. Johansen, MD, MS, and Joshua D. Niforatos, MD, MTS, said their study suggests that previously reported decreases in primary care contact was caused by fewer contacts per patient “as opposed to an absolute decrease in the number of patients in contact with primary care.”

Harold B. Betton, MD, PhD, who practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark., questioned this claim.

“In my reading, the authors concluded that people are seeing their primary care physicians fewer times than in the past, which suggests something is happening,” Dr. Betton said in an interview. “The fact that fewer visits are occurring may be due to multiple things, i.e., urgent care visits, visits to physician extenders – physician assistants and advanced practice nurses – or emergency room visits.”

"The paper draws observational conclusions and I fail to see the merit in the observation without knowing what the respondents were asked and not asked," he added.

Other primary care physicians suggested patients’ participation in alternative pay models and high-deductible plans have played a factor in the declines.

“Most of us have gone from fee-for-service, volume-based care to more value-based care,” Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. The data reflect that trend, “whereas we were rewarded more for the number of people we were seeing, now we are trying to get towards more of the value that we provide,” suggested Dr. Stewart, who also practices family medicine with Cooperative Health in Columbia, S.C.

“Given the rise of high-deductible plans and copays, it is not surprising that younger patients, a generally healthier population, might well decrease their visits to a primary care physician. I would suspect that data for patients over 50 might well be different,” William E. Golden, MD, who is medical director at the Arkansas Department of Health & Human Services, noted in an interview.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, also cited greater participation in high-deductible plans as a possible factor that could be leading some patients to forgo visits, as well as increased financial insecurity, rendering it expensive to have the visit and also to take time from work for the visit.

“I would wonder if some of this is also due to how overloaded most primary care offices are so that instead of stopping accepting new patients or shedding patients, it is just harder for existing patients to be seen,” said Dr. Barrett, who is a general internist and associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. “Some of this could be from administrative burden – 2 hours per hour of clinic – and consequently reducing clinical time,” continued Dr. Barrett, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, which is affiliated with Family Practice News.

Other experts pointed to data showing an insufficient supply of PCPs as a potential explanation for the new study’s findings. The Health Resources and Services Organization, for example, reported that 83 million Americans live in primary care “health professional shortage areas,” as of Jan. 24, 2021, on their website.

New data

“The rate of any contact with a [PCP] for patients in the population over multiple 2-year periods decreased by 2.5% over the study period (adjusted odds ratio, 0.99 per panel; 95% [confidence interval], 0.98-0.99; P < .001),” wrote Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos. The rate of contact for patients aged 18-39 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < .001) and patients aged 40-64 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.99-1.00; P = .002), specifically, also fell. These decreased contact rates correspond “to a predicted cumulative 5% absolute decrease for the younger group and a 2% absolute decrease for the older group,” the authors added.

“The number of contacts with a [PCP] decreased among individuals with any contact by 0.5 contacts over 2 years (P < .001). A decrease in the number of [PCP] contacts was observed across all age groups (P < .001 for all), with the largest absolute decrease among individuals with higher contact rates (aged less than 4 years and aged greater than 64 years),” according to the paper.

Outlook for PCPs

Physicians questioned about how concerning these data are for the future of PCPs and their ability to keep their practices running were hesitant to speculate, because of uncertainty about the causes of the study findings.

“A quote from the paper indicates that the respondents were interviewed five times over 2 years; however, without a copy of the questionnaire it is impossible to know what they were asked and not asked,” said Dr. Betton, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News and runs his own private practice. “In addition, it is impossible for the reader to know whether they understood what a primary care physician was to do.

“To draw a conclusion that PCP visits are falling off per patient per provider is only helpful if patients are opting out of the primary care model of practice and opting in for point-of-care [urgent] care,” Dr. Betton added.

Internist Alan Nelson, MD, said he was also undecided about whether the findings of the study are good or bad news for the physician specialty of primary care.

“Similar findings have been reported by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. They certainly merit further investigation,” noted Dr. Nelson, who is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. “Is it because primary care physicians are too busy to see additional patients? Is it because nonphysician practitioners seem to be more caring? Should residency training be modified, and if so, how? In the meantime, I would not be surprised if the trend continues, at least in the short term.”

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the Primary Care Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that advocates to strengthen primary care and make it more responsive to patient needs and preferences, on the other hand, reacted with a concerned outlook for primary care.

This study and others show that “the U.S. health care system is moving away from a primary care orientation, and that is concerning,” Ms. Greiner said in an interview. “Health systems that are more oriented toward primary care have better population health outcomes, do better on measures of equity across different population groups, and are less costly.”

Authors’ take

“Future research is needed to determine whether fewer contacts per patient resulted in clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across disease processes,” wrote Dr. Johansen, who is a family medicine doctor affiliated with OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant in Columbus and with the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University, Dublin, and Dr. Niforatos, who is affiliated with the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The study’s limitations included reliance on self-reported categorization of PCP versus specialty care physician contact, insufficient accounting for nurse practitioner and physician assistant contact, and improved contact reporting having started in 2013, they said.

How to grow patient contact

For those PCPs looking to grow their visits and patient contact, Dr. Golden suggested they strengthen their medical home model in their practice.

“Medical home models help and transform practice operations. The Arkansas model is a multipayer model – private, Medicaid and CPC+ (Medicare),” said Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. It includes community-based doctors, not Federally Qualified Health Centers, and “requires 24/7 live voice access that promotes regular contact with patients and can reduce dependency on ER and urgent care center visits.”

“Greater use of patient portals and email communications facilitate access and patient engagement with their PCP,” Dr. Golden explained.

“Over the last 6 years, the Arkansas [patient-centered medical home] initiatives have altered culture and made our practice sites stronger to withstand COVID and other challenges. As our sites became more patient centered and incorporated behavioral health options, patients perceived greater value in the functionality of primary care” he said.

Dr. Barrett proposed PCPs participate in team-based care “for professional sustainability and also for patients to continue to experience high-quality, person-centered care.” She added that “telemedicine can also help practices maintain and increase patients, as it can lessen burden on patients and clinicians – if it is done right.”

“More flexible clinic hours is also key – after usual business hours and on weekends – but I would recommend in lieu of usual weekday hours and for those who can make it work with their family and other duties,” Dr. Barrett said. “Evening or Saturday morning clinic isn’t an option for everyone, but it is an option for many some of the time, and it would be great for access to care if it were available in more locations.”

Pandemic effect

The data examined by Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos predates the pandemic, but PCPs interviewed by this news organization have seen declining patient contact occur in 2020 as well.

In fact, a survey of 1,485 mostly physician primary care practitioners that began after the pandemic onset found that 43% of participants have fewer in-person visits, motivated largely by patient preferences (66%) and safety concerns (74%). This ongoing survey, which was conducted by the Larry Green Center in partnership with the Primary Care Collaborative, also indicated that, while 25% of participants saw a total increase in patient volume, more than half of primary care practitioners reported that chronic and wellness visits are down, 53% and 55%, respectively.

“Sometimes we have to go looking for our patients when we have not seen them in a while,” Dr. Stewart noted. “We saw that with COVID because people were fearful of coming into our offices, and we had to have some outreach.”

The study authors had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Barrett, Dr. Betton, Dr. Golden, Dr. Nelson, and Dr. Stewart had no relevant disclosures.

Jake Remaly contributed to this article.

––

The reasons for this less frequent contact and the ramifications for patients and doctors practicing primary care are unclear, according to various experts. But some offered possible explanations for the changes, with patients’ increased participation in high deductible plans and shortages in primary care physicians (PCPs) being among the most often cited.

The findings, which were published online Jan. 11 in Annals of Family Medicine, were derived from researchers using a repeated cross-sectional study of the 2002-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to characterize trends in primary care use. This survey, which collected information about medical care utilization from individuals and families, included 243,919 participants who were interviewed five times over 2 years. The authors defined primary care physician contact as “in-person visit or contact with a primary care physician (primarily telephone calls) with a reported specialty of family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, general pediatrics, or general practice physician.” According to the paper, “the proportion of individuals with any primary care physician contact was determined for both the population and by age group using logistic regression models,” and negative binomial regression models were used to determine the number of contacts among people with visits during 2-year periods.

The study authors, Michael E. Johansen, MD, MS, and Joshua D. Niforatos, MD, MTS, said their study suggests that previously reported decreases in primary care contact was caused by fewer contacts per patient “as opposed to an absolute decrease in the number of patients in contact with primary care.”

Harold B. Betton, MD, PhD, who practices family medicine in Little Rock, Ark., questioned this claim.

“In my reading, the authors concluded that people are seeing their primary care physicians fewer times than in the past, which suggests something is happening,” Dr. Betton said in an interview. “The fact that fewer visits are occurring may be due to multiple things, i.e., urgent care visits, visits to physician extenders – physician assistants and advanced practice nurses – or emergency room visits.”

"The paper draws observational conclusions and I fail to see the merit in the observation without knowing what the respondents were asked and not asked," he added.

Other primary care physicians suggested patients’ participation in alternative pay models and high-deductible plans have played a factor in the declines.

“Most of us have gone from fee-for-service, volume-based care to more value-based care,” Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. The data reflect that trend, “whereas we were rewarded more for the number of people we were seeing, now we are trying to get towards more of the value that we provide,” suggested Dr. Stewart, who also practices family medicine with Cooperative Health in Columbia, S.C.

“Given the rise of high-deductible plans and copays, it is not surprising that younger patients, a generally healthier population, might well decrease their visits to a primary care physician. I would suspect that data for patients over 50 might well be different,” William E. Golden, MD, who is medical director at the Arkansas Department of Health & Human Services, noted in an interview.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, also cited greater participation in high-deductible plans as a possible factor that could be leading some patients to forgo visits, as well as increased financial insecurity, rendering it expensive to have the visit and also to take time from work for the visit.

“I would wonder if some of this is also due to how overloaded most primary care offices are so that instead of stopping accepting new patients or shedding patients, it is just harder for existing patients to be seen,” said Dr. Barrett, who is a general internist and associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. “Some of this could be from administrative burden – 2 hours per hour of clinic – and consequently reducing clinical time,” continued Dr. Barrett, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, which is affiliated with Family Practice News.

Other experts pointed to data showing an insufficient supply of PCPs as a potential explanation for the new study’s findings. The Health Resources and Services Organization, for example, reported that 83 million Americans live in primary care “health professional shortage areas,” as of Jan. 24, 2021, on their website.

New data

“The rate of any contact with a [PCP] for patients in the population over multiple 2-year periods decreased by 2.5% over the study period (adjusted odds ratio, 0.99 per panel; 95% [confidence interval], 0.98-0.99; P < .001),” wrote Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos. The rate of contact for patients aged 18-39 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < .001) and patients aged 40-64 years (aOR, 0.99 per panel; 95% CI, 0.99-1.00; P = .002), specifically, also fell. These decreased contact rates correspond “to a predicted cumulative 5% absolute decrease for the younger group and a 2% absolute decrease for the older group,” the authors added.

“The number of contacts with a [PCP] decreased among individuals with any contact by 0.5 contacts over 2 years (P < .001). A decrease in the number of [PCP] contacts was observed across all age groups (P < .001 for all), with the largest absolute decrease among individuals with higher contact rates (aged less than 4 years and aged greater than 64 years),” according to the paper.

Outlook for PCPs

Physicians questioned about how concerning these data are for the future of PCPs and their ability to keep their practices running were hesitant to speculate, because of uncertainty about the causes of the study findings.

“A quote from the paper indicates that the respondents were interviewed five times over 2 years; however, without a copy of the questionnaire it is impossible to know what they were asked and not asked,” said Dr. Betton, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News and runs his own private practice. “In addition, it is impossible for the reader to know whether they understood what a primary care physician was to do.

“To draw a conclusion that PCP visits are falling off per patient per provider is only helpful if patients are opting out of the primary care model of practice and opting in for point-of-care [urgent] care,” Dr. Betton added.

Internist Alan Nelson, MD, said he was also undecided about whether the findings of the study are good or bad news for the physician specialty of primary care.

“Similar findings have been reported by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. They certainly merit further investigation,” noted Dr. Nelson, who is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. “Is it because primary care physicians are too busy to see additional patients? Is it because nonphysician practitioners seem to be more caring? Should residency training be modified, and if so, how? In the meantime, I would not be surprised if the trend continues, at least in the short term.”

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the Primary Care Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that advocates to strengthen primary care and make it more responsive to patient needs and preferences, on the other hand, reacted with a concerned outlook for primary care.

This study and others show that “the U.S. health care system is moving away from a primary care orientation, and that is concerning,” Ms. Greiner said in an interview. “Health systems that are more oriented toward primary care have better population health outcomes, do better on measures of equity across different population groups, and are less costly.”

Authors’ take

“Future research is needed to determine whether fewer contacts per patient resulted in clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across disease processes,” wrote Dr. Johansen, who is a family medicine doctor affiliated with OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant in Columbus and with the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University, Dublin, and Dr. Niforatos, who is affiliated with the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The study’s limitations included reliance on self-reported categorization of PCP versus specialty care physician contact, insufficient accounting for nurse practitioner and physician assistant contact, and improved contact reporting having started in 2013, they said.

How to grow patient contact

For those PCPs looking to grow their visits and patient contact, Dr. Golden suggested they strengthen their medical home model in their practice.

“Medical home models help and transform practice operations. The Arkansas model is a multipayer model – private, Medicaid and CPC+ (Medicare),” said Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. It includes community-based doctors, not Federally Qualified Health Centers, and “requires 24/7 live voice access that promotes regular contact with patients and can reduce dependency on ER and urgent care center visits.”

“Greater use of patient portals and email communications facilitate access and patient engagement with their PCP,” Dr. Golden explained.

“Over the last 6 years, the Arkansas [patient-centered medical home] initiatives have altered culture and made our practice sites stronger to withstand COVID and other challenges. As our sites became more patient centered and incorporated behavioral health options, patients perceived greater value in the functionality of primary care” he said.

Dr. Barrett proposed PCPs participate in team-based care “for professional sustainability and also for patients to continue to experience high-quality, person-centered care.” She added that “telemedicine can also help practices maintain and increase patients, as it can lessen burden on patients and clinicians – if it is done right.”

“More flexible clinic hours is also key – after usual business hours and on weekends – but I would recommend in lieu of usual weekday hours and for those who can make it work with their family and other duties,” Dr. Barrett said. “Evening or Saturday morning clinic isn’t an option for everyone, but it is an option for many some of the time, and it would be great for access to care if it were available in more locations.”

Pandemic effect

The data examined by Dr. Johansen and Dr. Niforatos predates the pandemic, but PCPs interviewed by this news organization have seen declining patient contact occur in 2020 as well.

In fact, a survey of 1,485 mostly physician primary care practitioners that began after the pandemic onset found that 43% of participants have fewer in-person visits, motivated largely by patient preferences (66%) and safety concerns (74%). This ongoing survey, which was conducted by the Larry Green Center in partnership with the Primary Care Collaborative, also indicated that, while 25% of participants saw a total increase in patient volume, more than half of primary care practitioners reported that chronic and wellness visits are down, 53% and 55%, respectively.

“Sometimes we have to go looking for our patients when we have not seen them in a while,” Dr. Stewart noted. “We saw that with COVID because people were fearful of coming into our offices, and we had to have some outreach.”

The study authors had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Barrett, Dr. Betton, Dr. Golden, Dr. Nelson, and Dr. Stewart had no relevant disclosures.

Jake Remaly contributed to this article.

FROM ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

Family Practice News celebrates 50 years

This year, in each issue and on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine throughout 2021.

We plan to address the biggest breakthroughs and most influential people in family medicine over the past 50 years. The publication will also share family physicians’ expectations and hopes for the specialty in the coming years.

Are there any topics you think would be valuable to cover in light of this major milestone? The editorial staff welcomes your suggestions. Please share them by emailing us at [email protected].

Happy New Year, and thank you for supporting us for so many years!

This year, in each issue and on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine throughout 2021.

We plan to address the biggest breakthroughs and most influential people in family medicine over the past 50 years. The publication will also share family physicians’ expectations and hopes for the specialty in the coming years.

Are there any topics you think would be valuable to cover in light of this major milestone? The editorial staff welcomes your suggestions. Please share them by emailing us at [email protected].

Happy New Year, and thank you for supporting us for so many years!

This year, in each issue and on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine throughout 2021.

We plan to address the biggest breakthroughs and most influential people in family medicine over the past 50 years. The publication will also share family physicians’ expectations and hopes for the specialty in the coming years.

Are there any topics you think would be valuable to cover in light of this major milestone? The editorial staff welcomes your suggestions. Please share them by emailing us at [email protected].

Happy New Year, and thank you for supporting us for so many years!

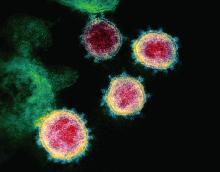

WHO: Asymptomatic COVID-19 spread deemed ‘rare’

An official with the World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that it appears to be “rare” that an asymptomatic individual can pass SARS-CoV-2 to someone else.

“From the data we have, it still seems to be rare that an asymptomatic person actually transmits onward to a secondary individual,” Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, WHO’s COVID-19 technical lead and an infectious disease epidemiologist, said June 8 at a news briefing from the agency’s Geneva headquarters.