User login

Clustered Vesicles on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

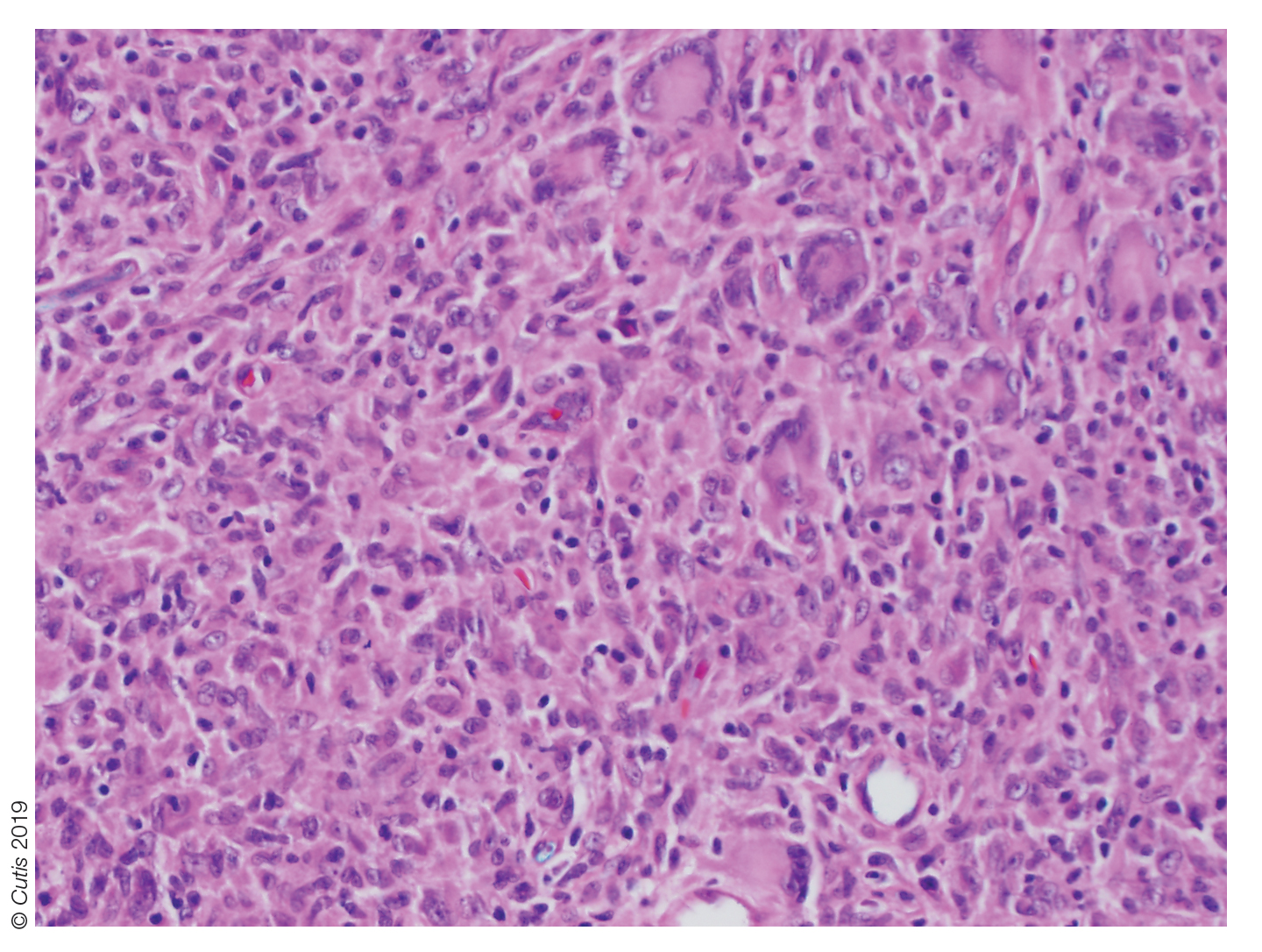

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

A 6-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the right side of the neck that was noted at birth as a small raised lesion but slowly increased over time in size and number of lesions. She reported pruritus and irritation, particularly when rubbed or scratched. There was no family history of similar skin abnormalities. Her medical history was notable for a left-sided cholesteatoma on tympanomastoidectomy. Physical examination revealed clustered vesicles on the right side of the neck with underlying erythema. The vesicles contained mostly clear fluid with a few focal areas of hemorrhagic fluid. Ultrasonography was unremarkable, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed superficial T2 hyperintense nonenhancing cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions overlying the right lateral neck with minimal extension into the superficial right supraclavicular soft tissues.

Rubbery Nodule on the Face of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

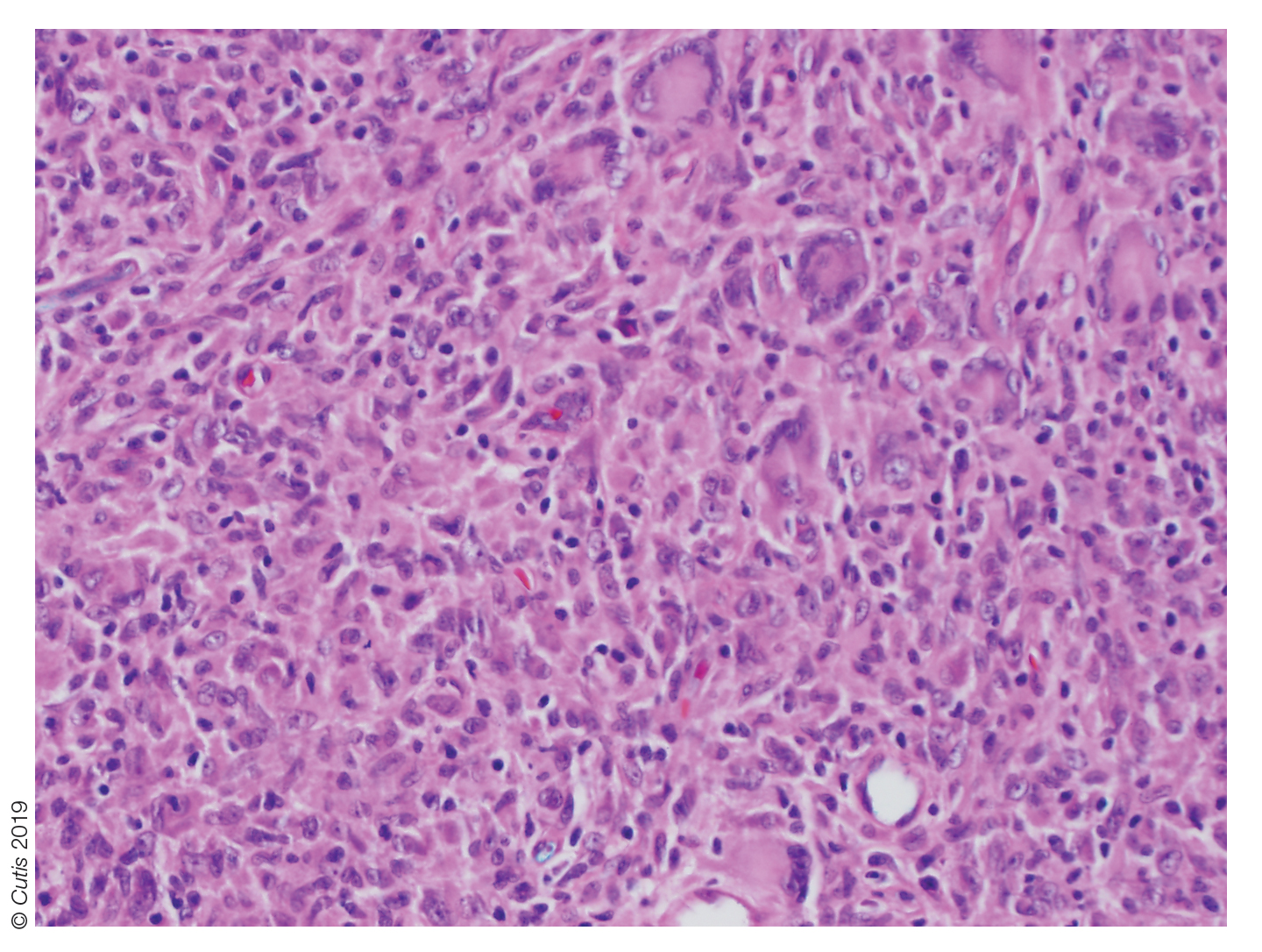

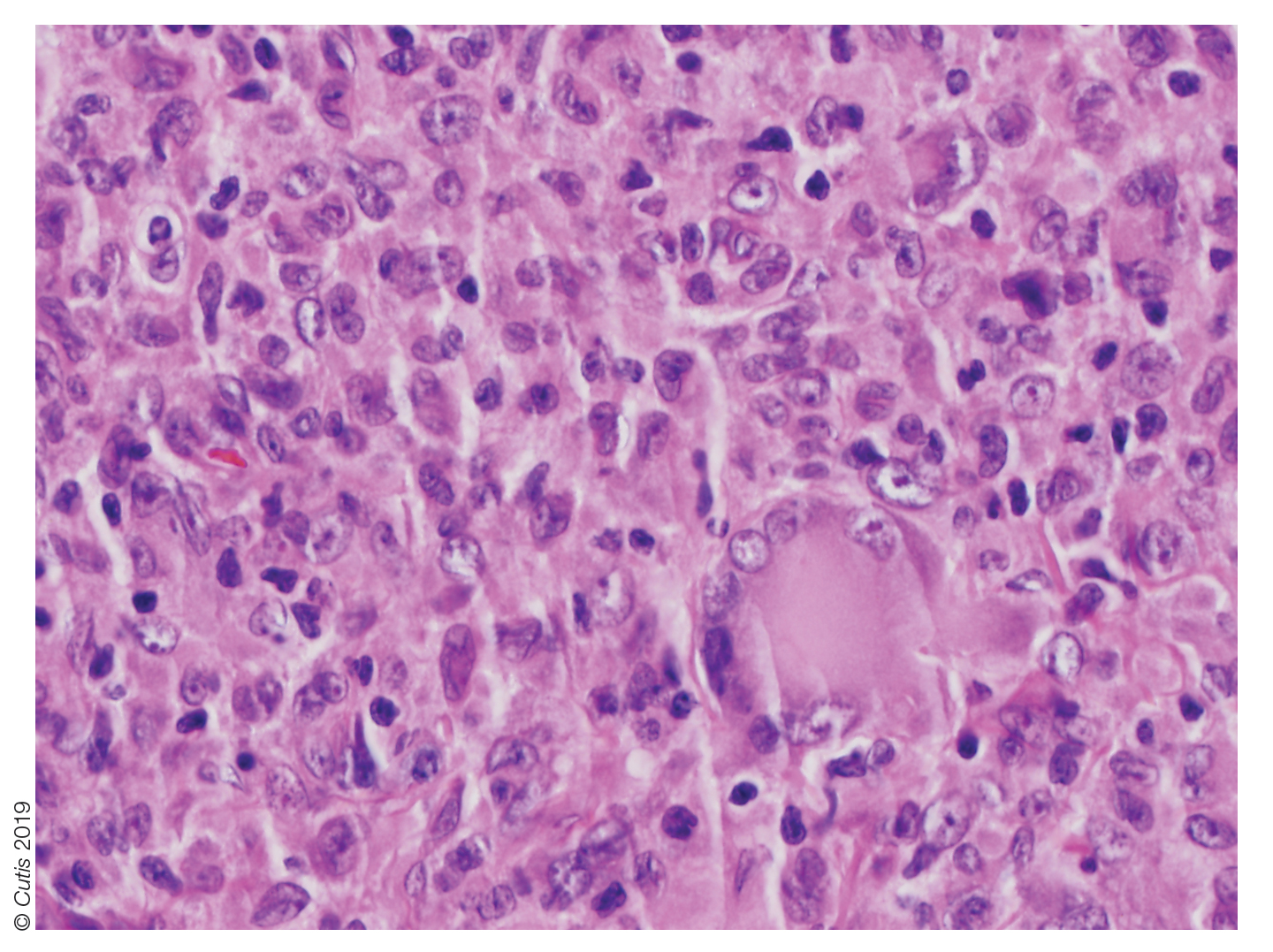

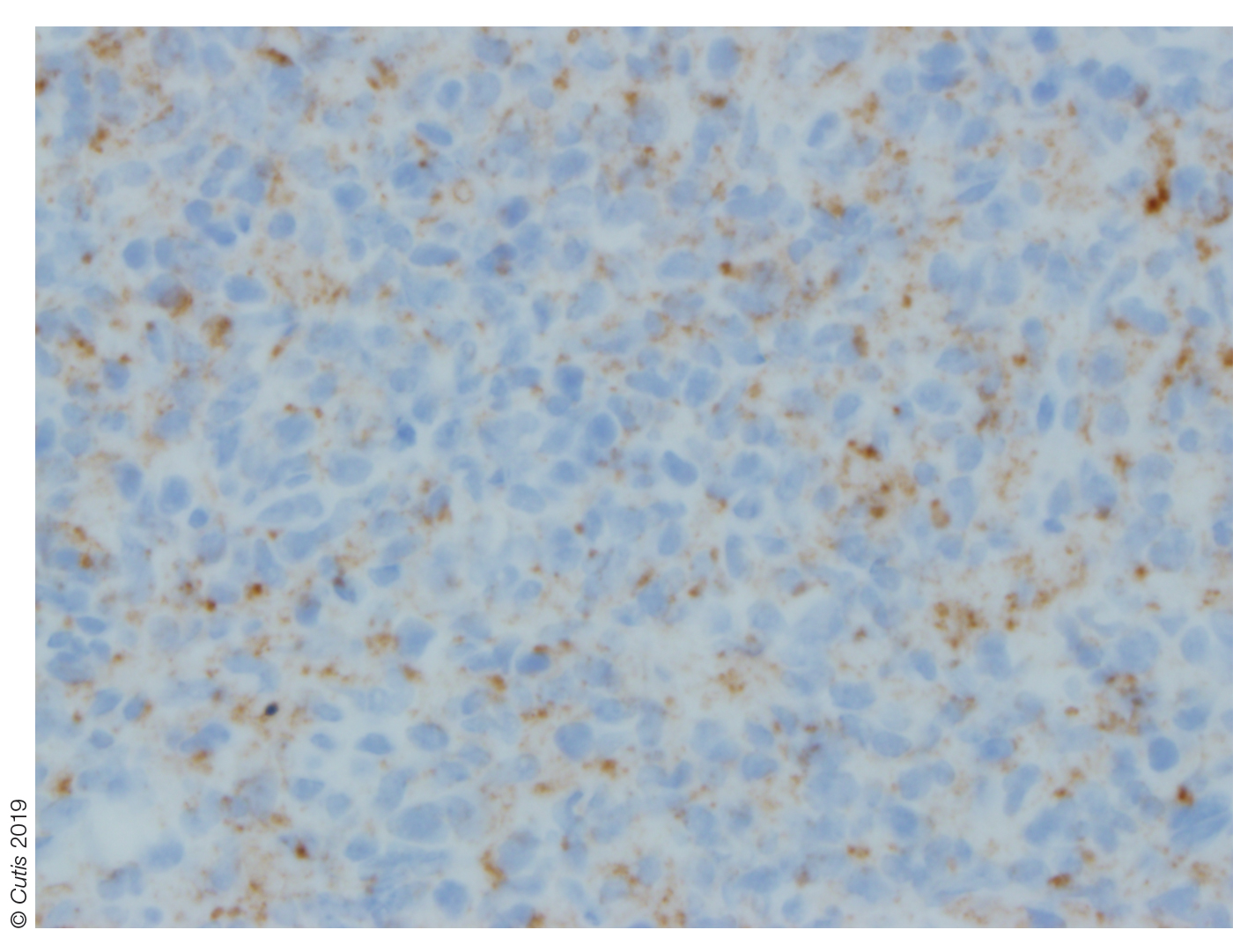

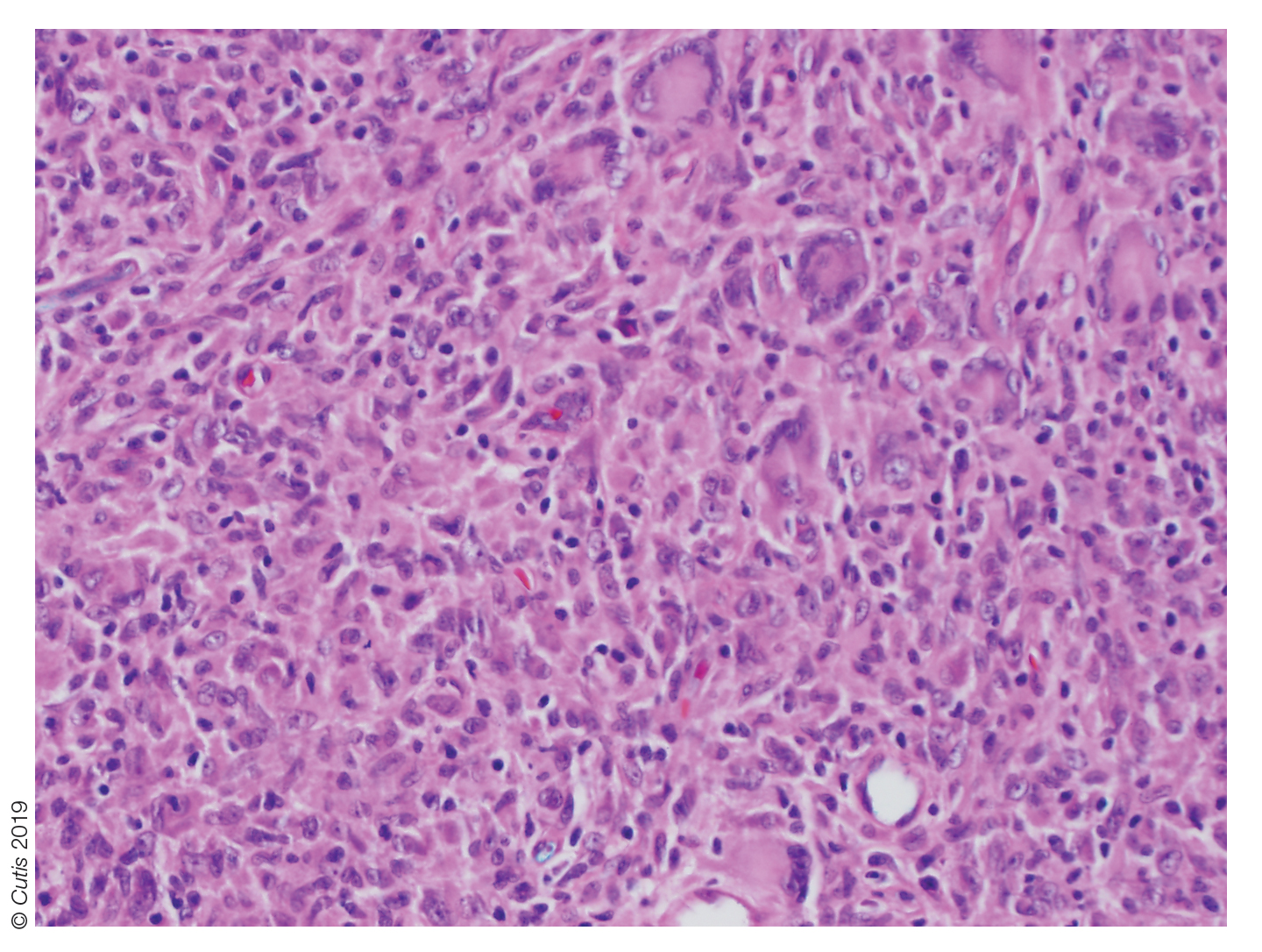

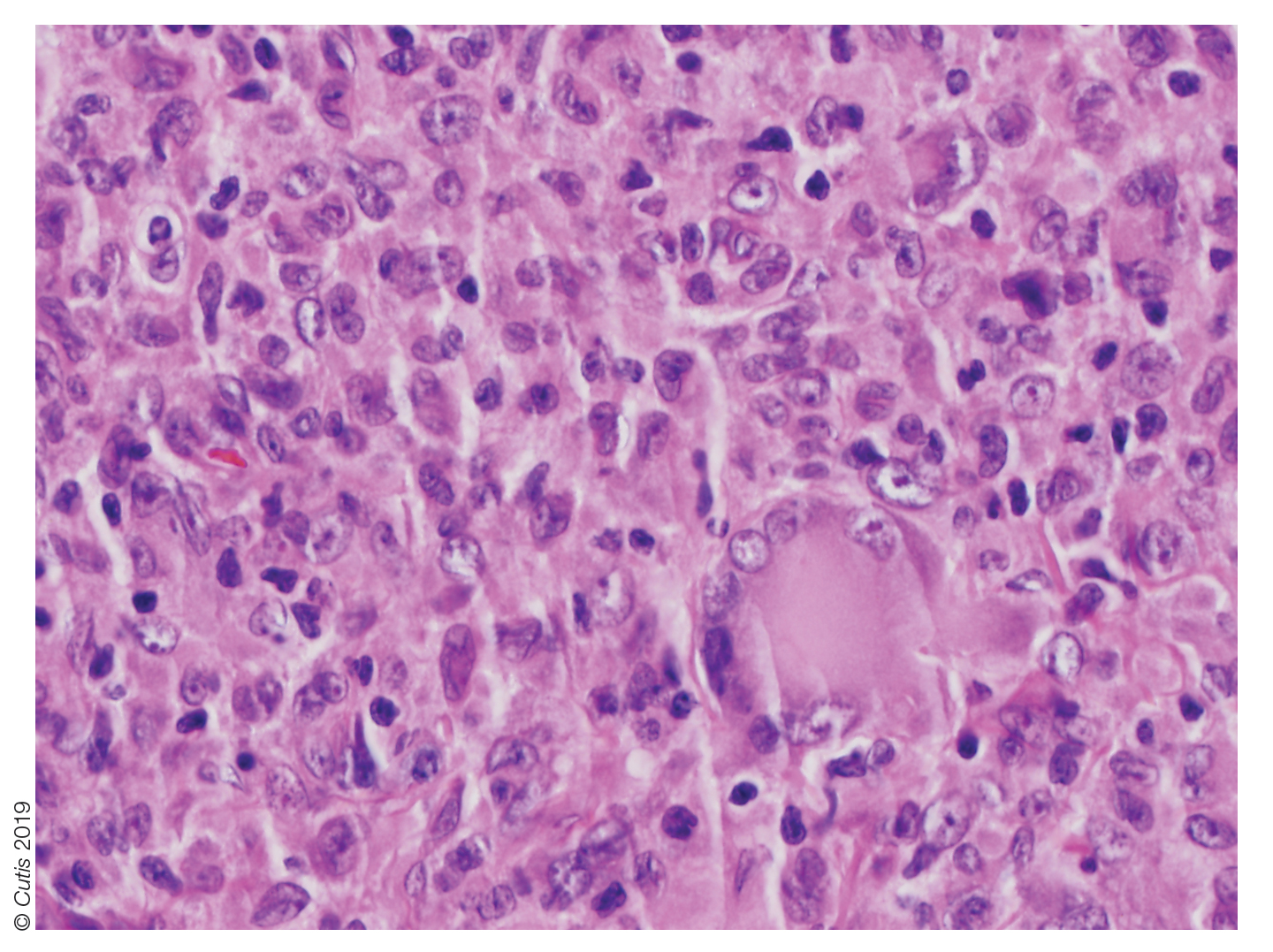

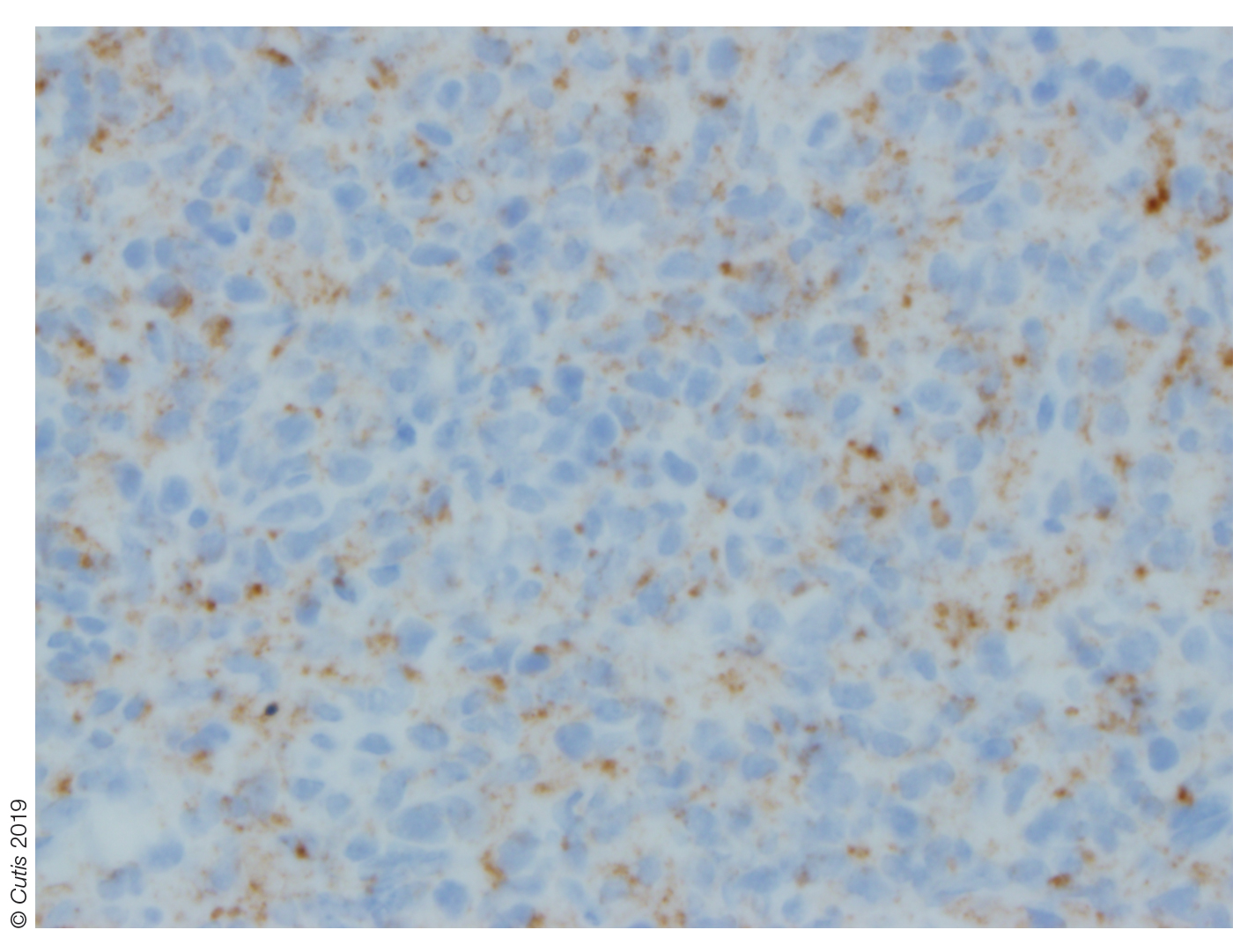

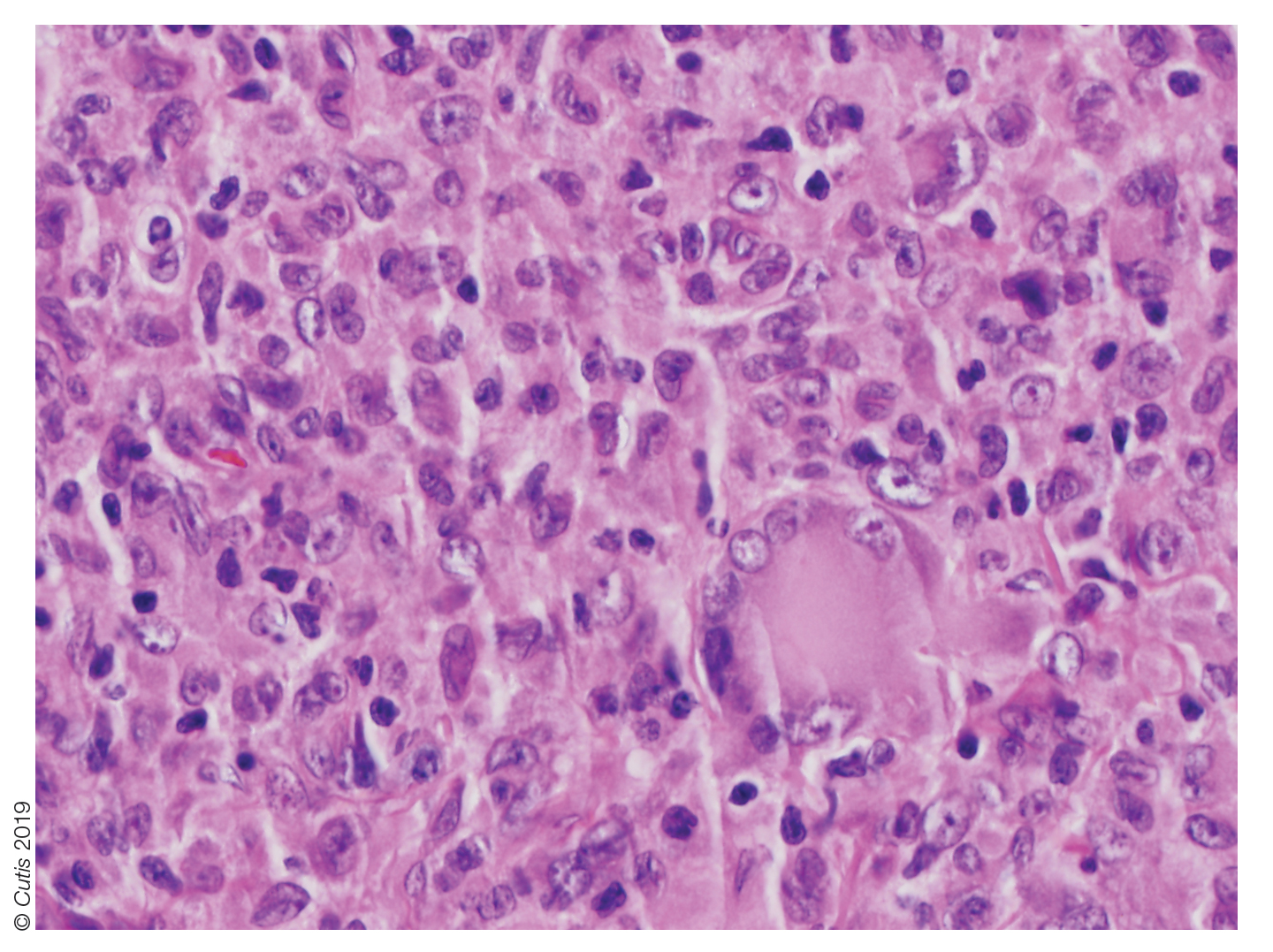

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

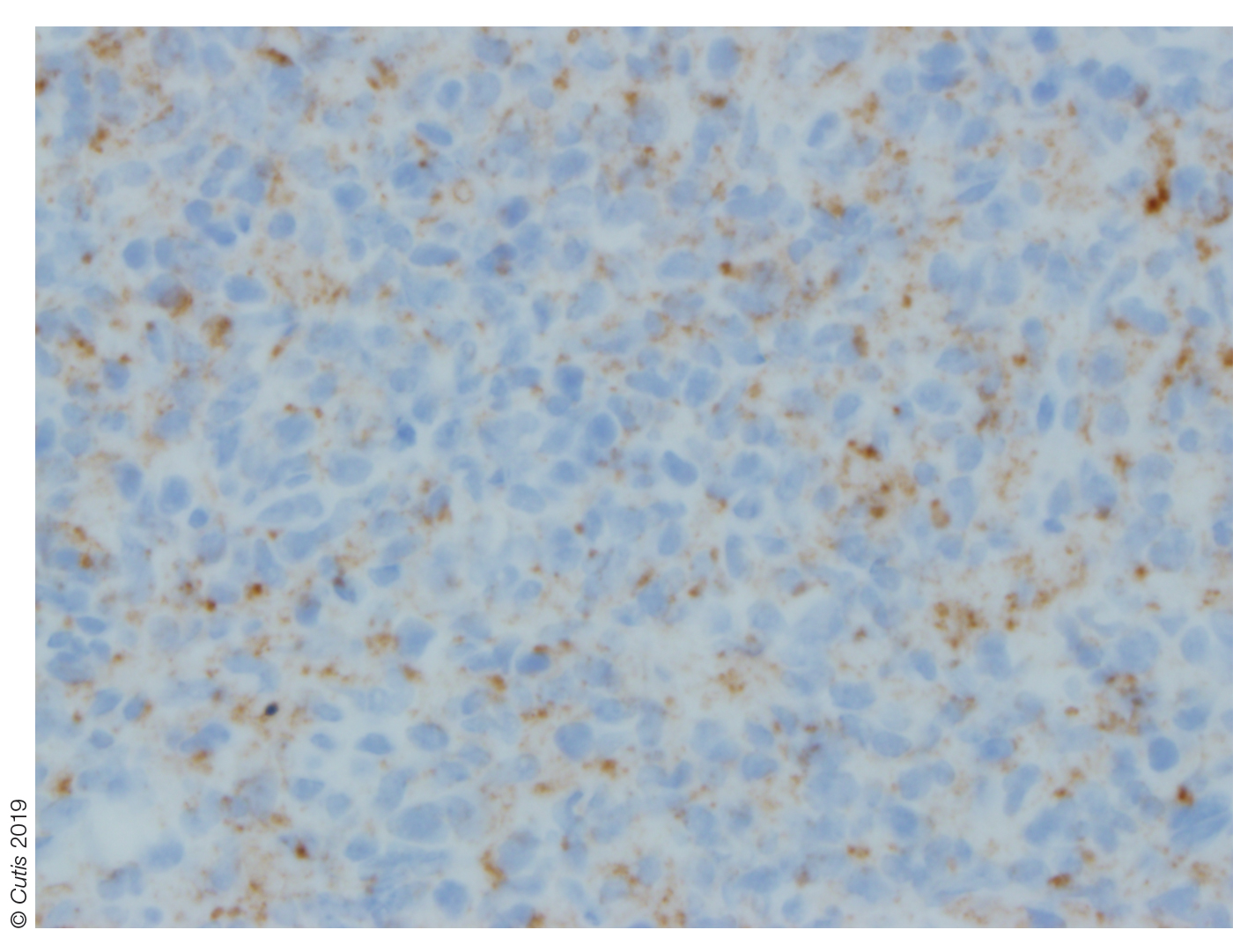

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

A 10-month-old girl presented with a facial nodule of 7 months’ duration that started as a small lesion. On physical examination, a single 10×10-mm, nontender, well-circumscribed, firm, freely mobile nodule was observed in the left infraorbital area. The patient was born full term at 37 weeks’ gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery and had no other notable findings on physical examination. Excision was performed by an oculoplastic surgeon. Pathology revealed a relatively well-circumscribed, diffuse, dermal infiltrate of cells arranged in short fascicles and a storiform pattern. The cells had abundant clear to amphophilic cytoplasm, ovoid to reniform nuclei with vesicular chromatin and focal grooves, and diffuse CD68+ immunoreactivity, as well as scattered S-100–positive cells. The patient did well with the excision and no new lesions have developed.