User login

A Severe Presentation of Plasma Cell Cheilitis

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

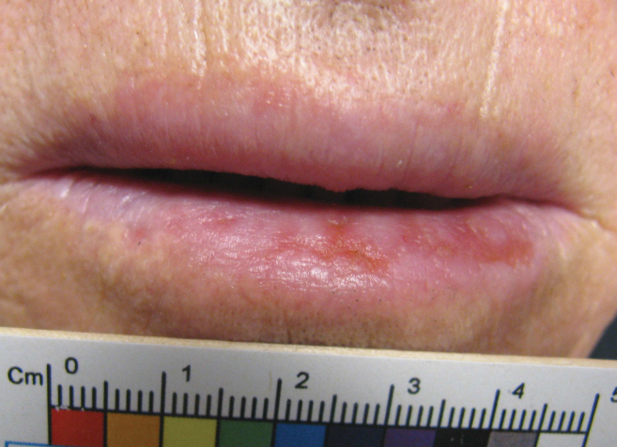

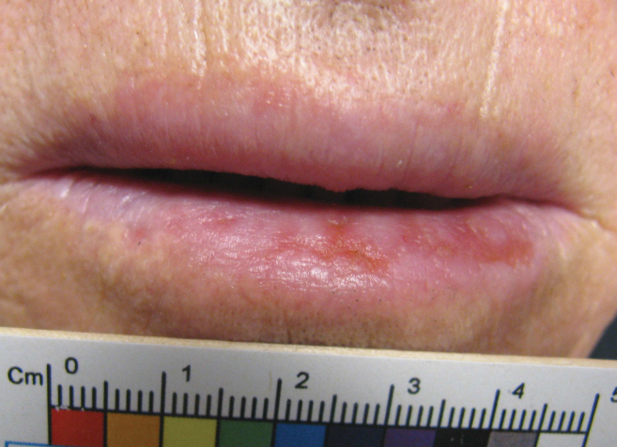

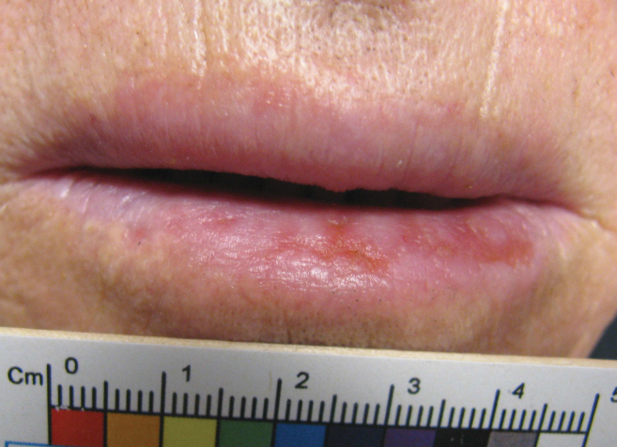

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

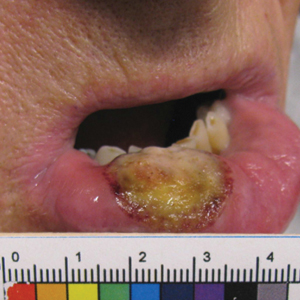

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

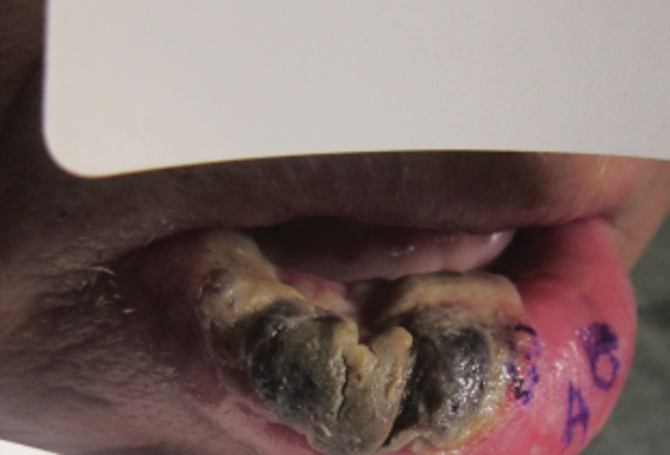

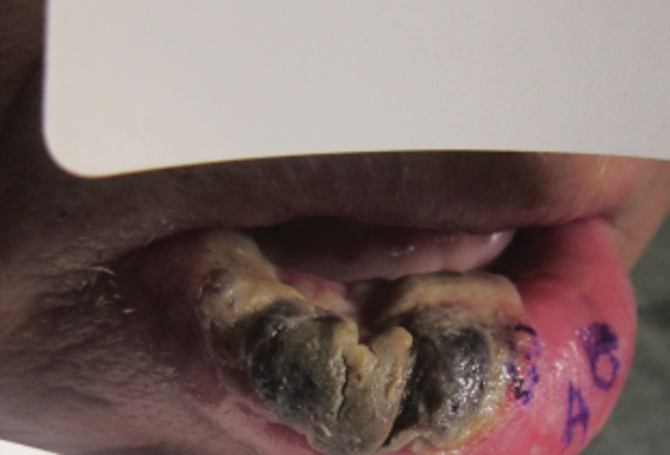

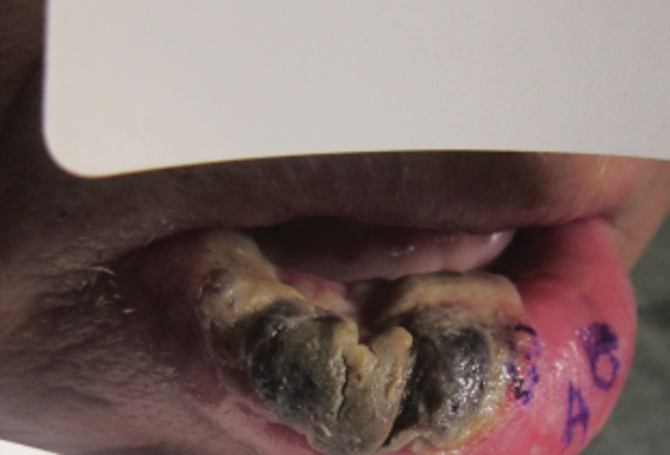

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

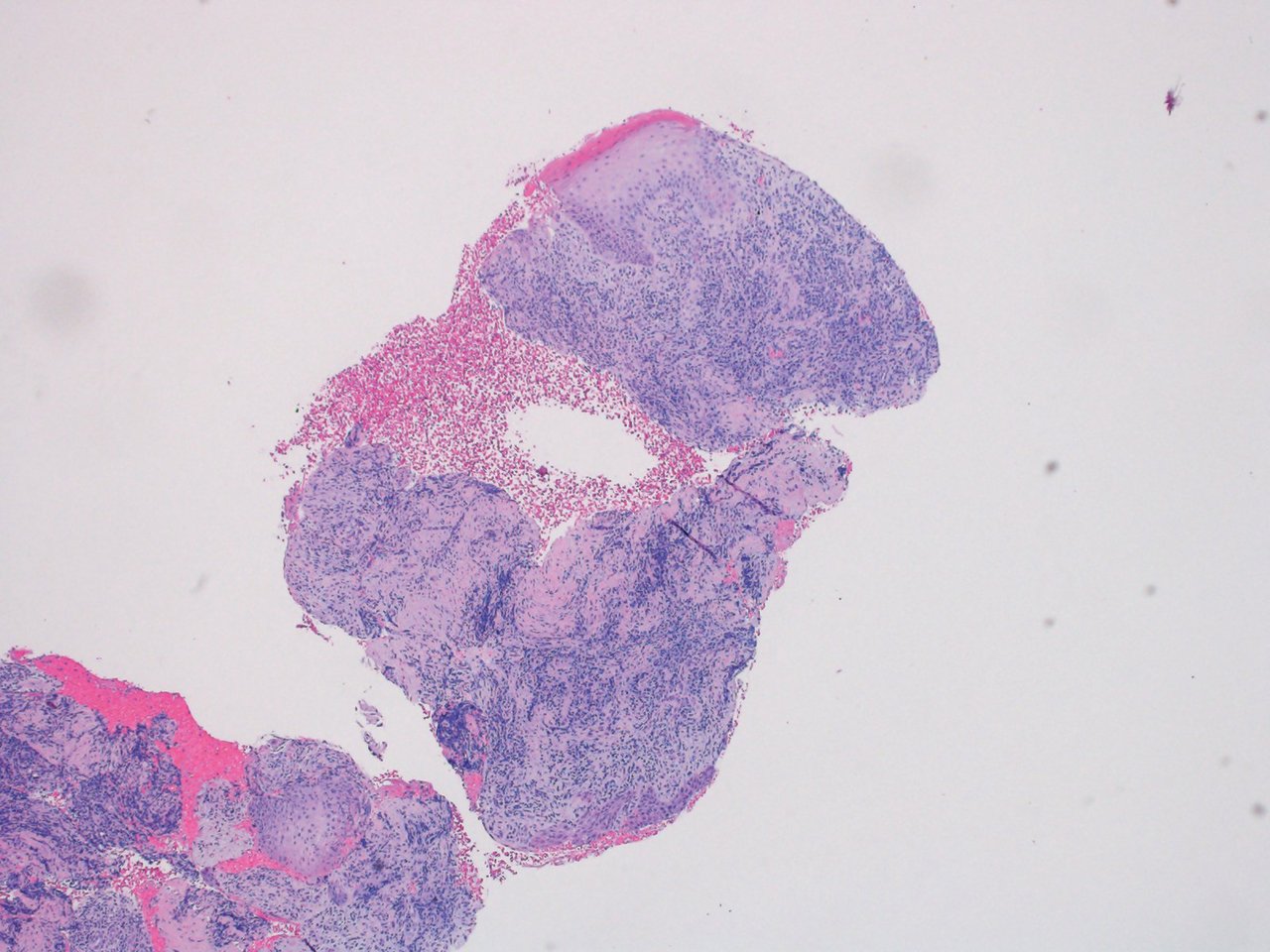

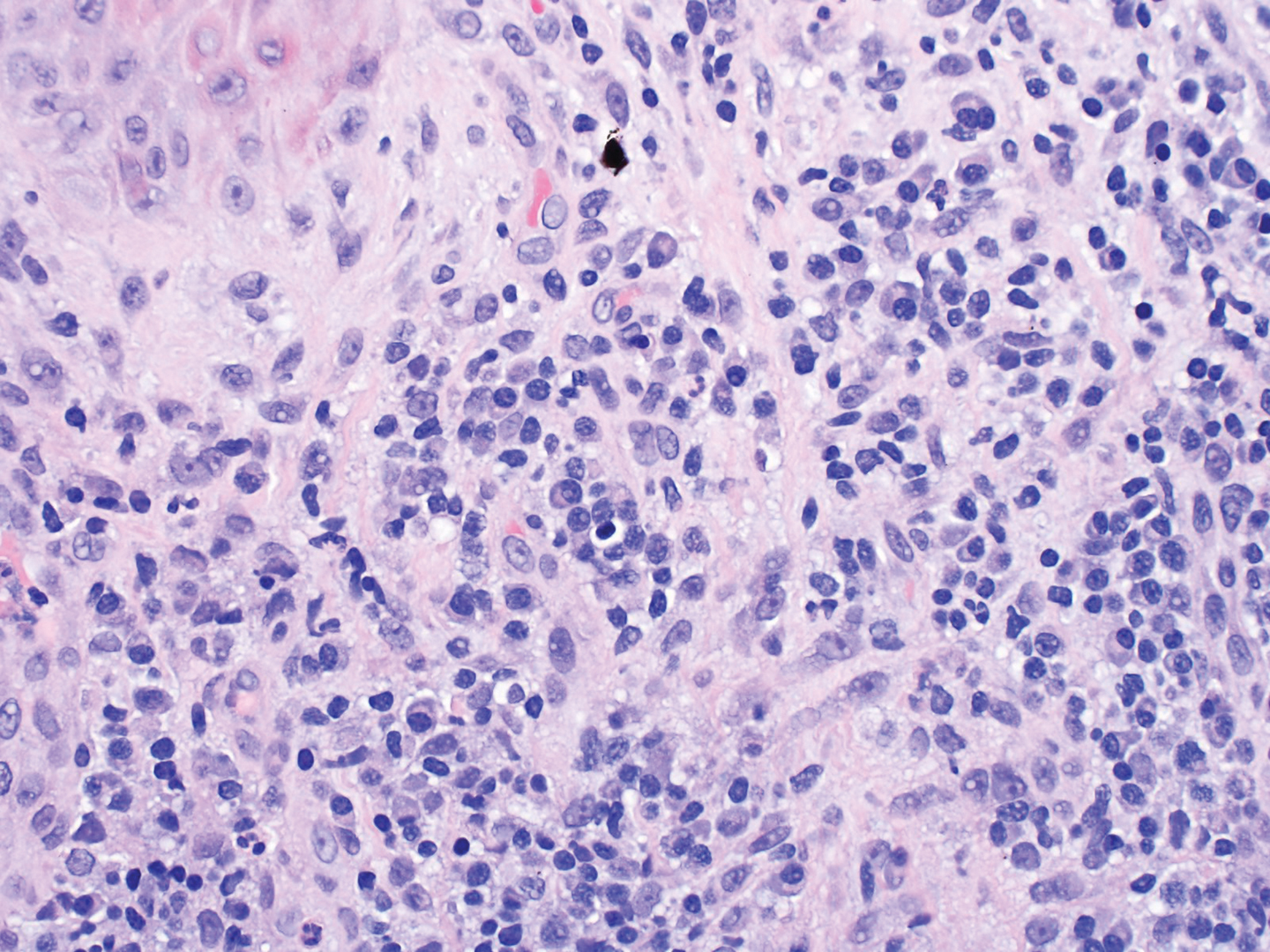

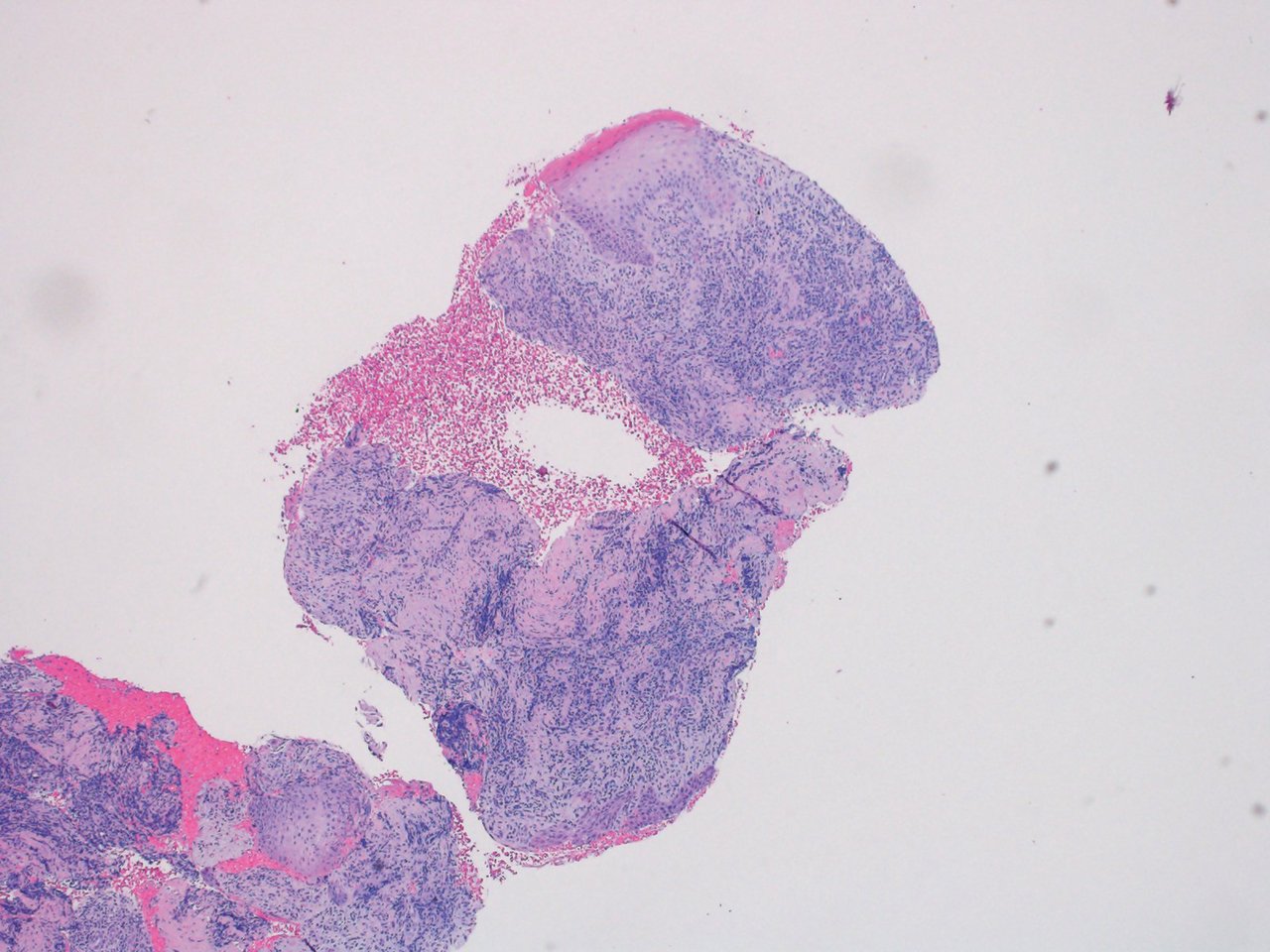

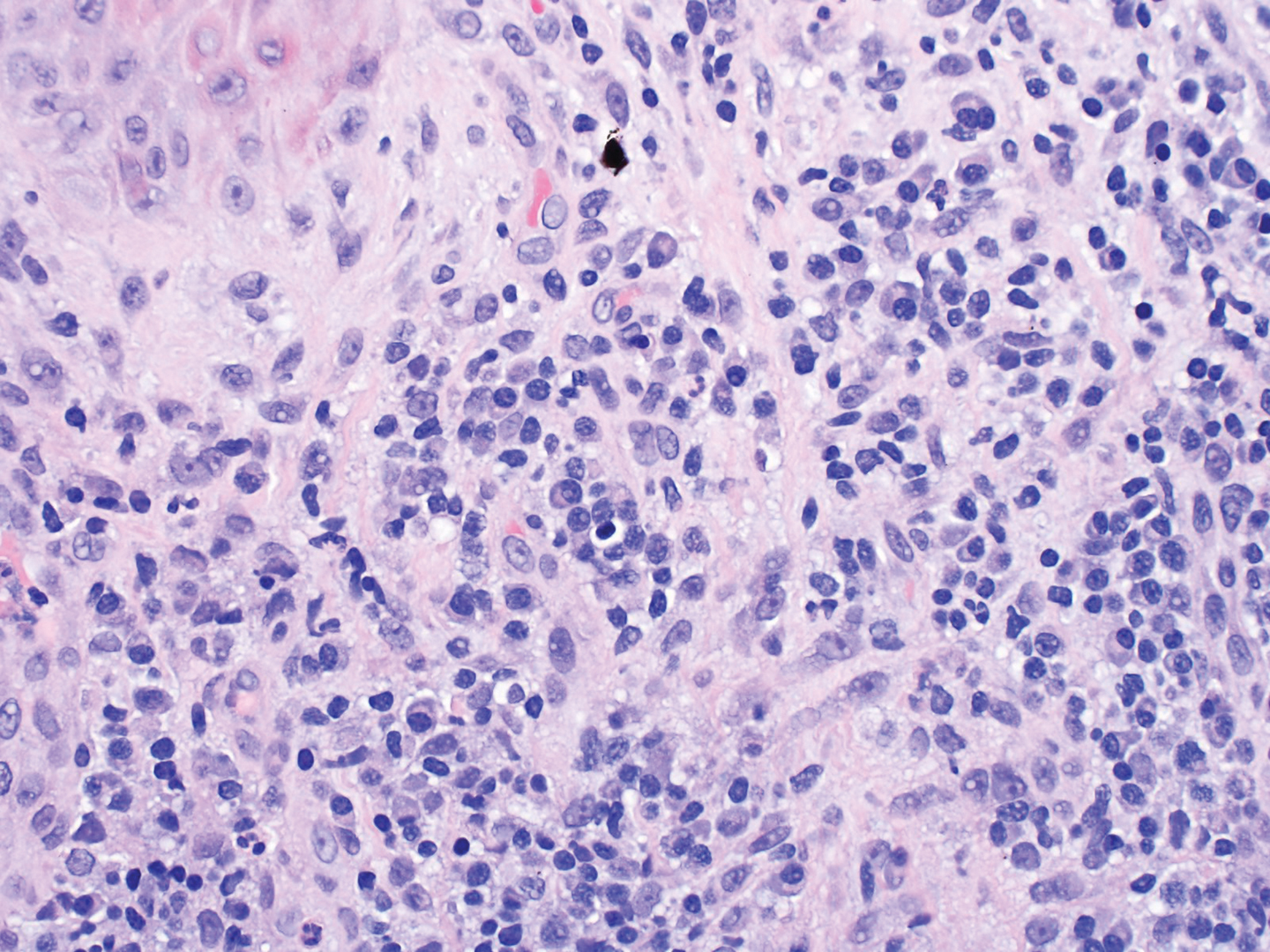

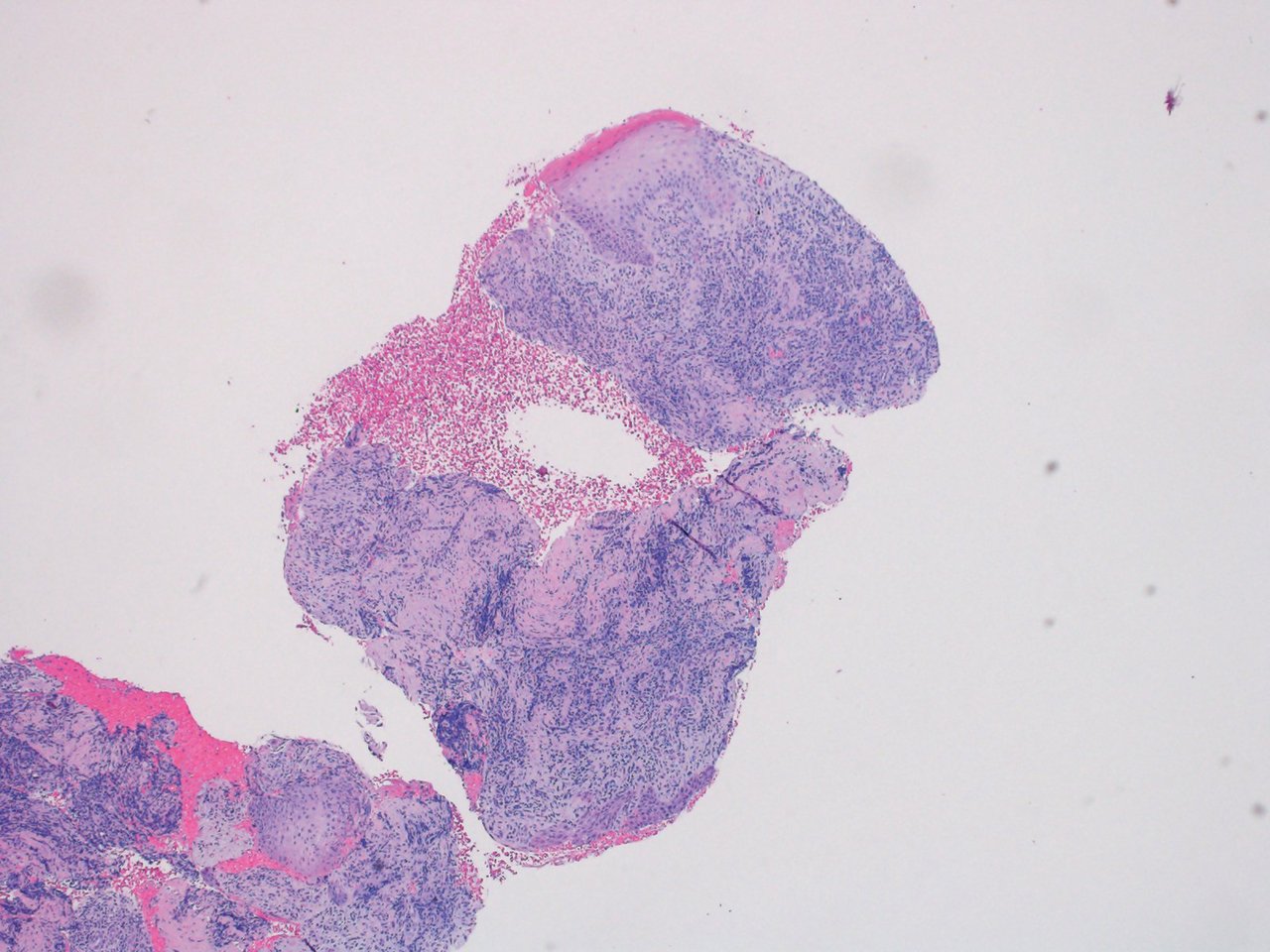

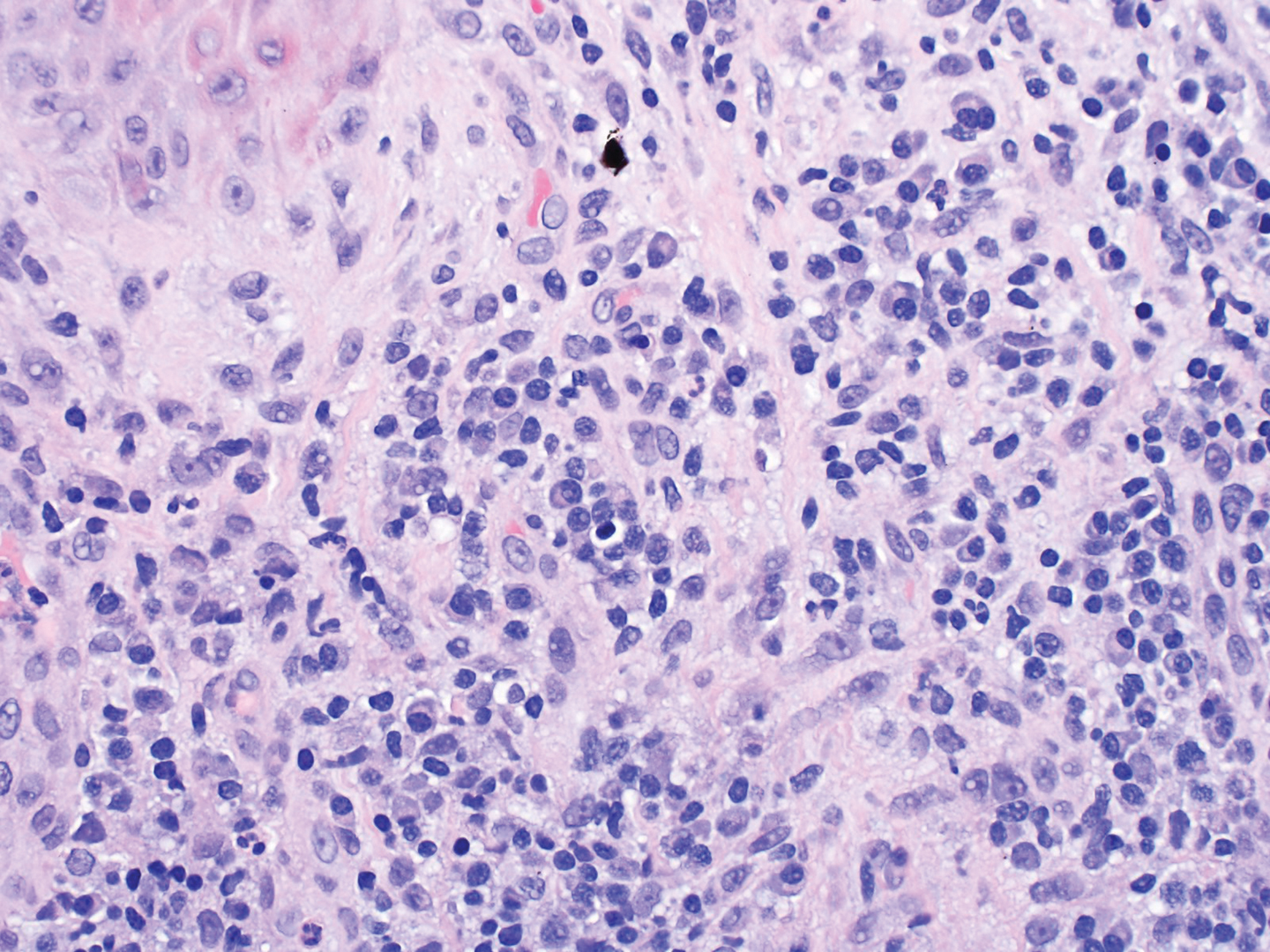

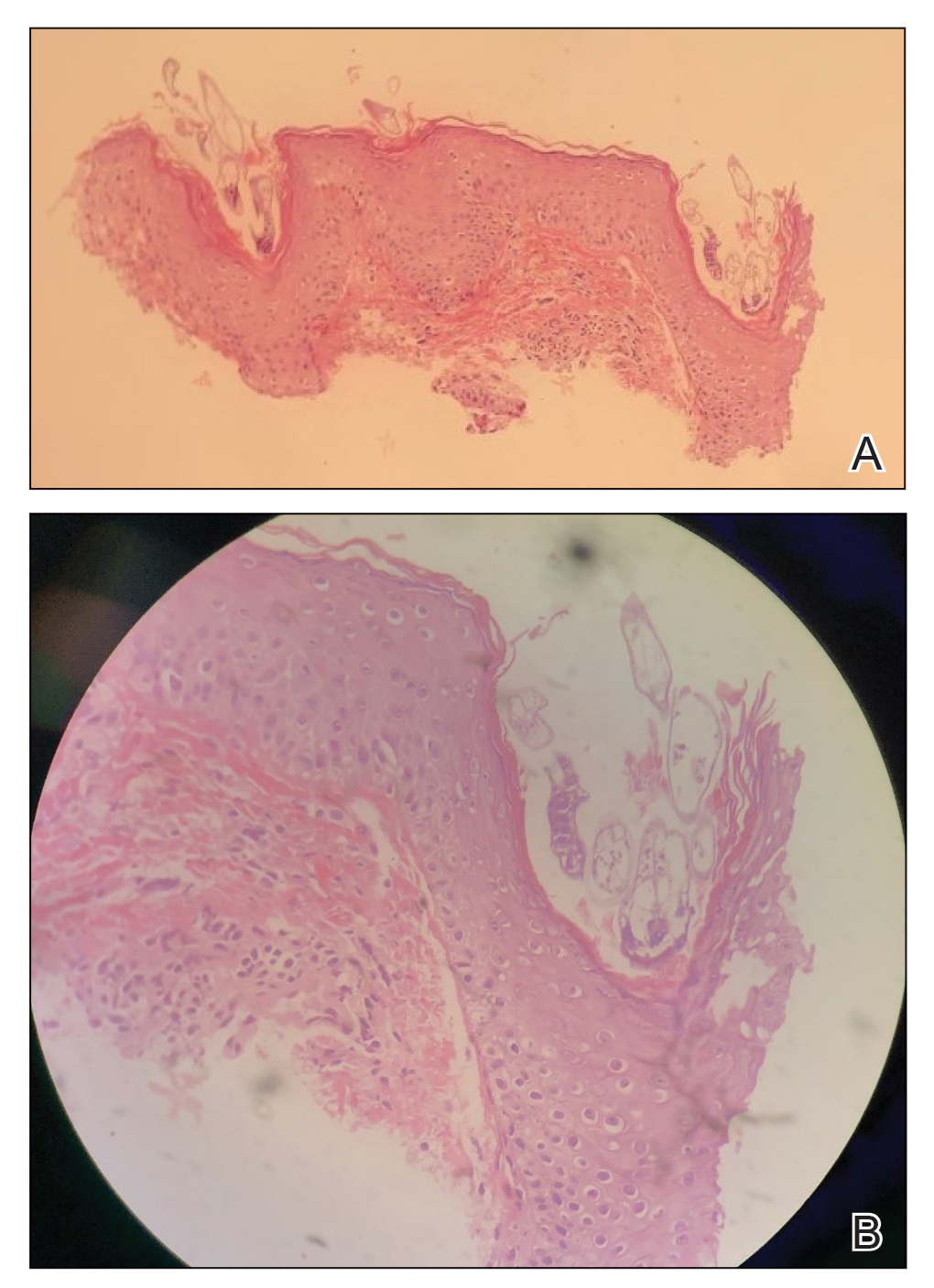

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC) is a benign condition that affects the lower lip in older individuals, presenting as a nonspecific, red-brown patch or plaque that can progress slowly to erosions and edema.

- Our patient with PCC experienced full resolution of symptoms with application of a class I topical corticosteroid.

Pruritic and Pustular Eruption on the Face

The Diagnosis: Demodicosis

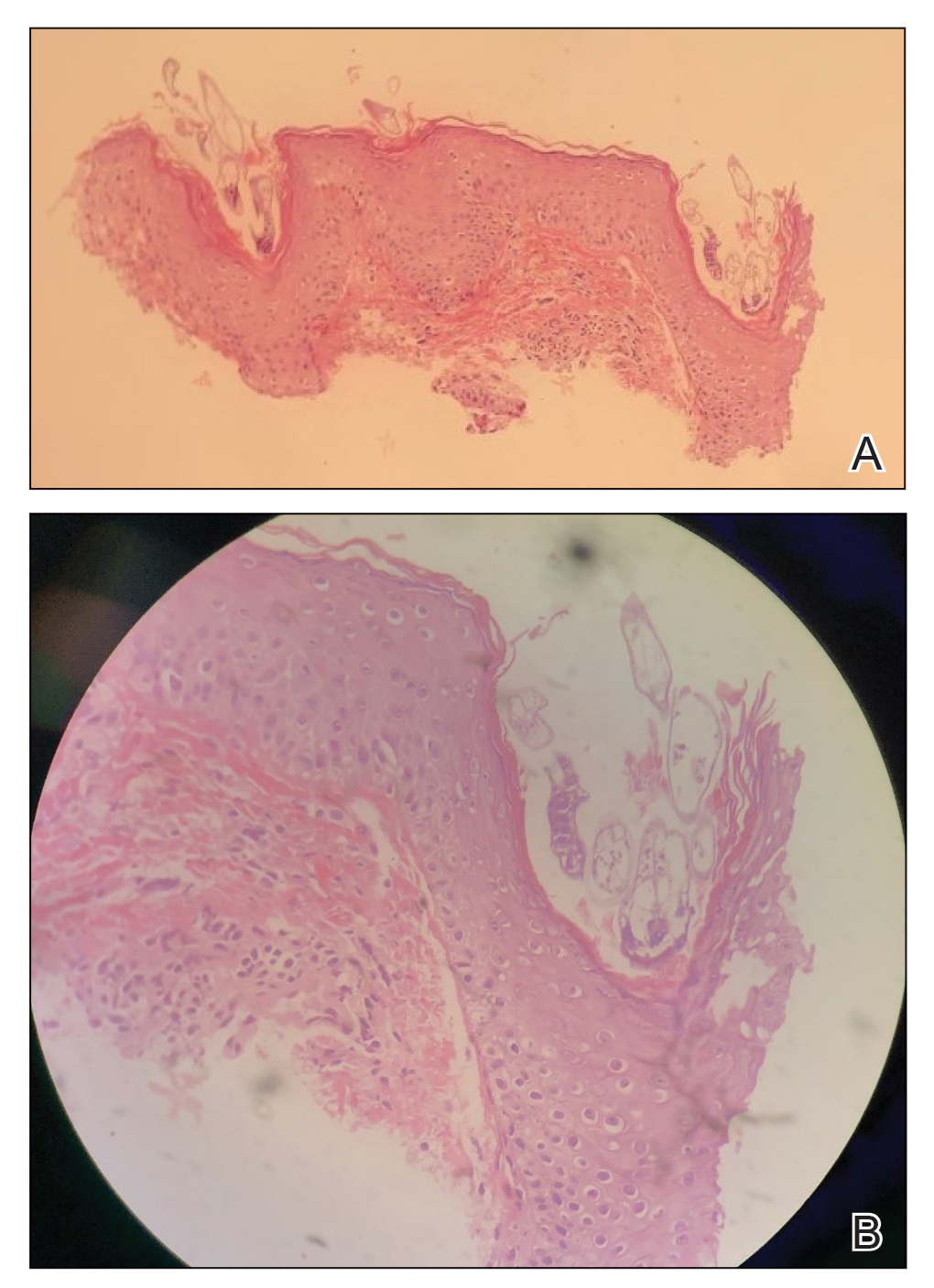

A clinical diagnosis of facial demodicosis triggered by topical corticosteroid therapy was suspected in our patient. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right forehead demonstrated a follicular infundibulum rich in Demodex folliculorum with a discrete mononuclear infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis. The patient was prescribed metronidazole gel 2% twice daily. Complete clearance of the facial rash was observed at 1-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Demodex folliculorum is a mite that parasitizes the pilosebaceous follicles of human skin, becoming pathogenic with excessive colonization.1-3 Facial demodicosis presents as pruritic papules and pustules in a pilosebaceous distribution on the face.2,3 The diagnosis of facial demodicosis can be difficult due to similarities with many other common facial rashes such as acne, rosacea, contact dermatitis, and folliculitis.

Similar to facial demodicosis, rosacea can present with erythema, papules, and pustules on the face. Patients with rosacea also have a higher prevalence and degree of Demodex mite infestation.4 However, these facial rashes can be differentiated when symptom acuity and personal and family histories are considered. In patients with a long-standing personal and/or family history of erythema, papules, and pustules, the chronicity of disease implies a diagnosis of rosacea. The acute onset of symptomatology and absence of personal or family history of rosacea in our patient favored a diagnosis of demodicosis.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is an eruption caused by Malassezia furfur, the organism implicated in tinea versicolor. It can present similarly to Demodex folliculitis with follicular papules and pustules on the forehead and back. Features that help to differentiate Pityrosporum folliculitis from Demodex folliculitis include involvement of the upper trunk and onset after antibiotic usage.5 Diagnosis of Pityrosporum folliculitis can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide preparation, which demonstrates spaghetti-and-meatball-like hyphae and spores.

Eosinophilic folliculitis is a chronic sterile folliculitis that usually presents as intensely pruritic papules and pustules on the face with an eruptive onset. There are 3 variants of disease: the classic form (also known as Ofuji disease), immunosuppression-associated disease, and infancy-associated disease.6 Eosinophilic folliculitis also may present with annular plaques and peripheral blood eosinophilia, and it is more prevalent in patients of Japanese descent. Differentiation from Demodex folliculitis can be done by histologic examination, which demonstrates spongiosis with exocytosis of eosinophils into the epithelium and a clear deficiency of infiltrating mites.6

Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, is a common condition that occurs due to occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.7 Clinically, miliaria is characterized by erythematous papules ranging from 2 to 4 mm in size that may be vesicular or pustular. Miliaria and demodicosis may have similar clinical presentations; however, several characteristic differences can be noted. Based on the pathophysiology, miliaria will not be folliculocentric, which differs from demodicosis. Additionally, miliaria most commonly occurs in areas of occlusion, such as in skin folds or on the trunk under tight clothing. Miliaria rarely can appear confluent and sunburnlike.8 Furthermore, miliaria is less common on the face, while demodicosis almost exclusively is found on the face.

We present the case of an otherwise healthy patient with acute onset of pruritic papules and pustules involving the superior face following topical corticosteroid use. Similar cases frequently are encountered by dermatologists and require broad differential diagnoses.

- Aylesworth R, Vance JC. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis in cutaneous biopsies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:583-589.

- Kligman AM, Christensen MS. Demodex folliculorum: requirements for understanding its role in human skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:8-10.

- Zomorodian K, Geramishoar M, Saadat F, et al. Facial demodicosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:121-122.

- Chang YS, Huang YC. Role of Demodex mite infestation in rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:441-447.

- Prindaville B, Belazarian L, Levin NA, et al. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a retrospective review of 110 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:511-514.

- Lankerani L, Thompson R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;86:190-194.

- Hölzle ER, Kligman AM. The pathogenesis of miliaria rubra. role of the resident microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:117-137.

- Al-Hilo MM, Al-Saedy SJ, Alwan AI. Atypical presentation of miliaria in Iraqi patients attending Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital in Baghdad: a clinical descriptive study. Am J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;1:41-46.

The Diagnosis: Demodicosis

A clinical diagnosis of facial demodicosis triggered by topical corticosteroid therapy was suspected in our patient. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right forehead demonstrated a follicular infundibulum rich in Demodex folliculorum with a discrete mononuclear infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis. The patient was prescribed metronidazole gel 2% twice daily. Complete clearance of the facial rash was observed at 1-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Demodex folliculorum is a mite that parasitizes the pilosebaceous follicles of human skin, becoming pathogenic with excessive colonization.1-3 Facial demodicosis presents as pruritic papules and pustules in a pilosebaceous distribution on the face.2,3 The diagnosis of facial demodicosis can be difficult due to similarities with many other common facial rashes such as acne, rosacea, contact dermatitis, and folliculitis.

Similar to facial demodicosis, rosacea can present with erythema, papules, and pustules on the face. Patients with rosacea also have a higher prevalence and degree of Demodex mite infestation.4 However, these facial rashes can be differentiated when symptom acuity and personal and family histories are considered. In patients with a long-standing personal and/or family history of erythema, papules, and pustules, the chronicity of disease implies a diagnosis of rosacea. The acute onset of symptomatology and absence of personal or family history of rosacea in our patient favored a diagnosis of demodicosis.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is an eruption caused by Malassezia furfur, the organism implicated in tinea versicolor. It can present similarly to Demodex folliculitis with follicular papules and pustules on the forehead and back. Features that help to differentiate Pityrosporum folliculitis from Demodex folliculitis include involvement of the upper trunk and onset after antibiotic usage.5 Diagnosis of Pityrosporum folliculitis can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide preparation, which demonstrates spaghetti-and-meatball-like hyphae and spores.

Eosinophilic folliculitis is a chronic sterile folliculitis that usually presents as intensely pruritic papules and pustules on the face with an eruptive onset. There are 3 variants of disease: the classic form (also known as Ofuji disease), immunosuppression-associated disease, and infancy-associated disease.6 Eosinophilic folliculitis also may present with annular plaques and peripheral blood eosinophilia, and it is more prevalent in patients of Japanese descent. Differentiation from Demodex folliculitis can be done by histologic examination, which demonstrates spongiosis with exocytosis of eosinophils into the epithelium and a clear deficiency of infiltrating mites.6

Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, is a common condition that occurs due to occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.7 Clinically, miliaria is characterized by erythematous papules ranging from 2 to 4 mm in size that may be vesicular or pustular. Miliaria and demodicosis may have similar clinical presentations; however, several characteristic differences can be noted. Based on the pathophysiology, miliaria will not be folliculocentric, which differs from demodicosis. Additionally, miliaria most commonly occurs in areas of occlusion, such as in skin folds or on the trunk under tight clothing. Miliaria rarely can appear confluent and sunburnlike.8 Furthermore, miliaria is less common on the face, while demodicosis almost exclusively is found on the face.

We present the case of an otherwise healthy patient with acute onset of pruritic papules and pustules involving the superior face following topical corticosteroid use. Similar cases frequently are encountered by dermatologists and require broad differential diagnoses.

The Diagnosis: Demodicosis

A clinical diagnosis of facial demodicosis triggered by topical corticosteroid therapy was suspected in our patient. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right forehead demonstrated a follicular infundibulum rich in Demodex folliculorum with a discrete mononuclear infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis. The patient was prescribed metronidazole gel 2% twice daily. Complete clearance of the facial rash was observed at 1-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Demodex folliculorum is a mite that parasitizes the pilosebaceous follicles of human skin, becoming pathogenic with excessive colonization.1-3 Facial demodicosis presents as pruritic papules and pustules in a pilosebaceous distribution on the face.2,3 The diagnosis of facial demodicosis can be difficult due to similarities with many other common facial rashes such as acne, rosacea, contact dermatitis, and folliculitis.

Similar to facial demodicosis, rosacea can present with erythema, papules, and pustules on the face. Patients with rosacea also have a higher prevalence and degree of Demodex mite infestation.4 However, these facial rashes can be differentiated when symptom acuity and personal and family histories are considered. In patients with a long-standing personal and/or family history of erythema, papules, and pustules, the chronicity of disease implies a diagnosis of rosacea. The acute onset of symptomatology and absence of personal or family history of rosacea in our patient favored a diagnosis of demodicosis.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is an eruption caused by Malassezia furfur, the organism implicated in tinea versicolor. It can present similarly to Demodex folliculitis with follicular papules and pustules on the forehead and back. Features that help to differentiate Pityrosporum folliculitis from Demodex folliculitis include involvement of the upper trunk and onset after antibiotic usage.5 Diagnosis of Pityrosporum folliculitis can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide preparation, which demonstrates spaghetti-and-meatball-like hyphae and spores.

Eosinophilic folliculitis is a chronic sterile folliculitis that usually presents as intensely pruritic papules and pustules on the face with an eruptive onset. There are 3 variants of disease: the classic form (also known as Ofuji disease), immunosuppression-associated disease, and infancy-associated disease.6 Eosinophilic folliculitis also may present with annular plaques and peripheral blood eosinophilia, and it is more prevalent in patients of Japanese descent. Differentiation from Demodex folliculitis can be done by histologic examination, which demonstrates spongiosis with exocytosis of eosinophils into the epithelium and a clear deficiency of infiltrating mites.6

Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, is a common condition that occurs due to occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.7 Clinically, miliaria is characterized by erythematous papules ranging from 2 to 4 mm in size that may be vesicular or pustular. Miliaria and demodicosis may have similar clinical presentations; however, several characteristic differences can be noted. Based on the pathophysiology, miliaria will not be folliculocentric, which differs from demodicosis. Additionally, miliaria most commonly occurs in areas of occlusion, such as in skin folds or on the trunk under tight clothing. Miliaria rarely can appear confluent and sunburnlike.8 Furthermore, miliaria is less common on the face, while demodicosis almost exclusively is found on the face.

We present the case of an otherwise healthy patient with acute onset of pruritic papules and pustules involving the superior face following topical corticosteroid use. Similar cases frequently are encountered by dermatologists and require broad differential diagnoses.

- Aylesworth R, Vance JC. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis in cutaneous biopsies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:583-589.

- Kligman AM, Christensen MS. Demodex folliculorum: requirements for understanding its role in human skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:8-10.

- Zomorodian K, Geramishoar M, Saadat F, et al. Facial demodicosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:121-122.

- Chang YS, Huang YC. Role of Demodex mite infestation in rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:441-447.

- Prindaville B, Belazarian L, Levin NA, et al. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a retrospective review of 110 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:511-514.

- Lankerani L, Thompson R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;86:190-194.

- Hölzle ER, Kligman AM. The pathogenesis of miliaria rubra. role of the resident microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:117-137.

- Al-Hilo MM, Al-Saedy SJ, Alwan AI. Atypical presentation of miliaria in Iraqi patients attending Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital in Baghdad: a clinical descriptive study. Am J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;1:41-46.

- Aylesworth R, Vance JC. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis in cutaneous biopsies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:583-589.

- Kligman AM, Christensen MS. Demodex folliculorum: requirements for understanding its role in human skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:8-10.

- Zomorodian K, Geramishoar M, Saadat F, et al. Facial demodicosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:121-122.

- Chang YS, Huang YC. Role of Demodex mite infestation in rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:441-447.

- Prindaville B, Belazarian L, Levin NA, et al. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a retrospective review of 110 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:511-514.

- Lankerani L, Thompson R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;86:190-194.

- Hölzle ER, Kligman AM. The pathogenesis of miliaria rubra. role of the resident microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:117-137.

- Al-Hilo MM, Al-Saedy SJ, Alwan AI. Atypical presentation of miliaria in Iraqi patients attending Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital in Baghdad: a clinical descriptive study. Am J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;1:41-46.

A 37-year-old man presented with a progressively pruritic and pustular eruption on the face of 2 weeks’ duration. Twenty days prior to the rash onset, he began treatment for scalp psoriasis with a mixture of salicylic acid 20 mg/mL and betamethasone dipropionate 0.5 mg/mL, which inadvertently extended to the facial area. One week after rash onset, he presented to the emergency department at a local hospital, where he was given intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg with no improvement of the rash. He had no history of skin cancer, and his family history was negative for dermatologic disease. At the time of examination, he had an erythematous eruption of follicular micropustules on the forehead, upper and lower eyelids, temples, cheeks, and mandible.