User login

Isolated Perianal Erosive Lichen Planus: A Diagnostic Challenge

To the Editor:

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple pruritic and painful perianal lesions of 1 year’s duration. The lesions had remained stable since onset, with no other reported lesions elsewhere on body, including the mucosae. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. She was taking methotrexate, folic acid, abatacept, alendronate, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. The patient reported she had been using abatacept for 3 years and lisinopril for 2 years. Her primary care physician initially treated the lesions as hemorrhoids but referred her to a gastroenterologist when they failed to improve. Gastroenterology evaluated the patient, and a colonoscopy was performed with unremarkable results. Thus, she was referred to dermatology for further evaluation.

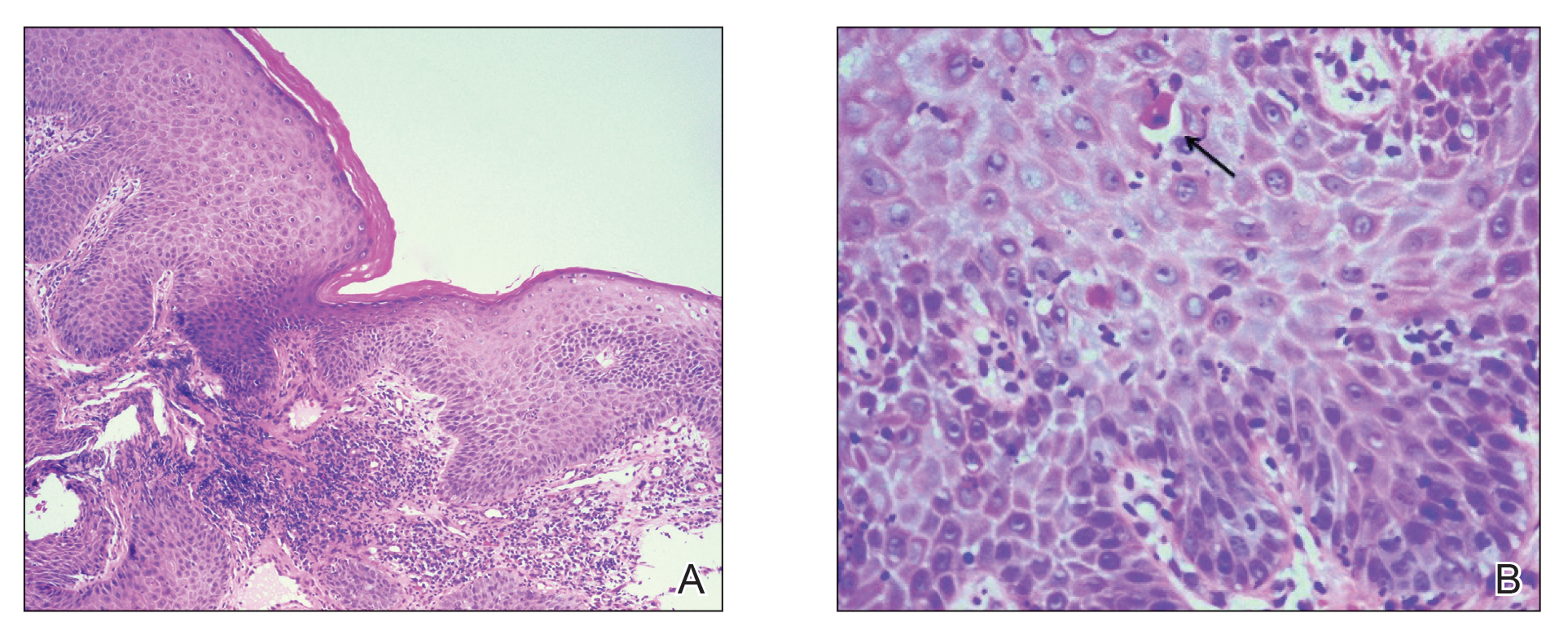

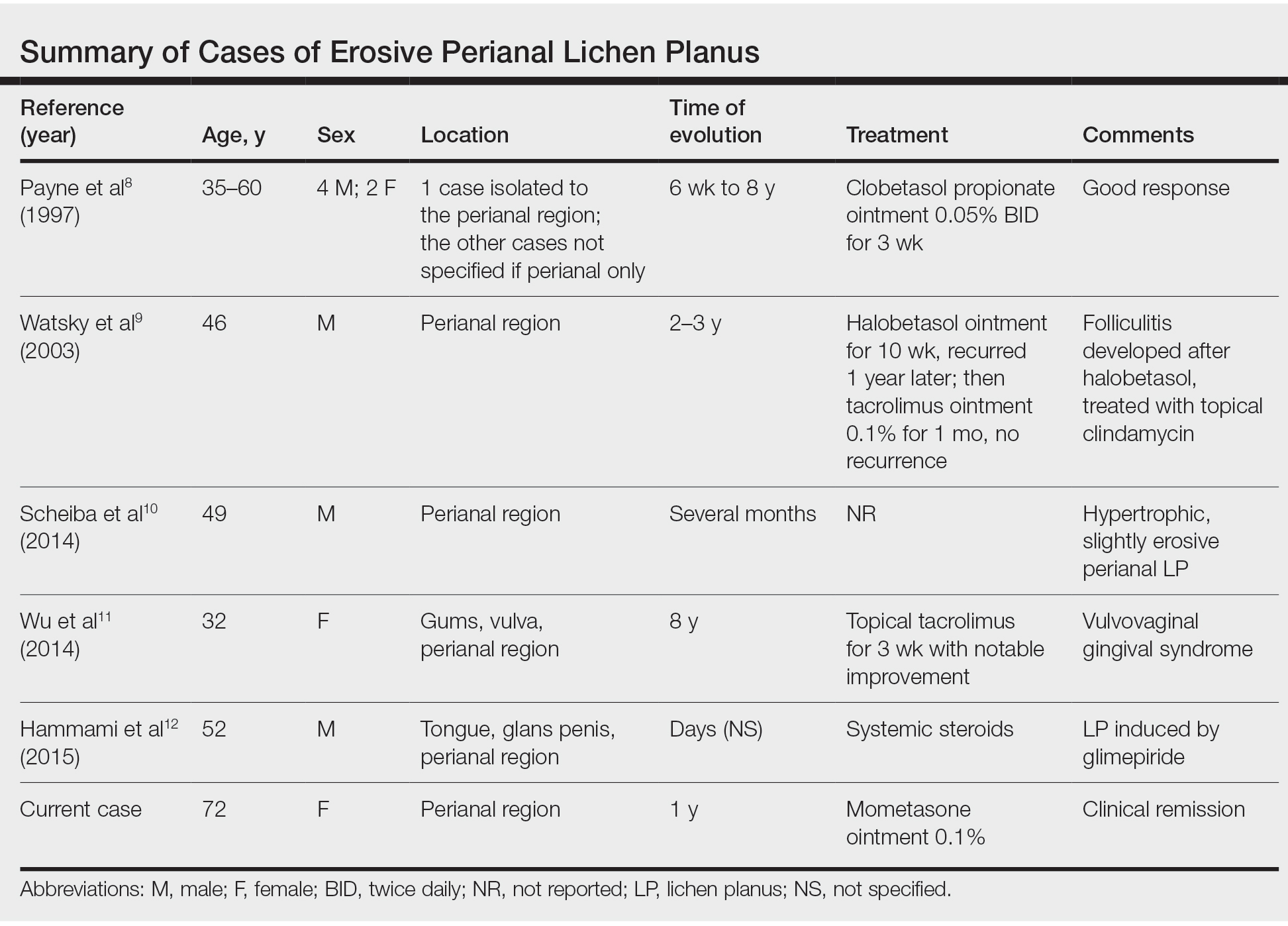

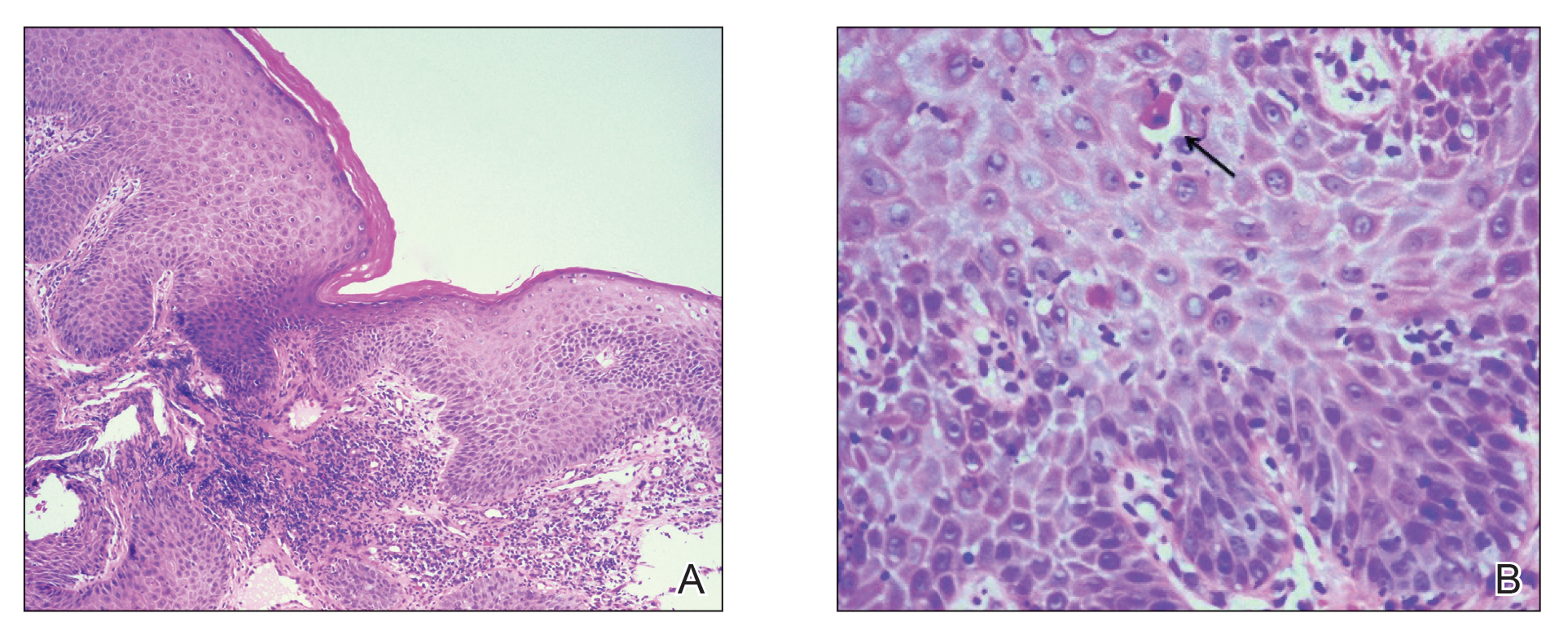

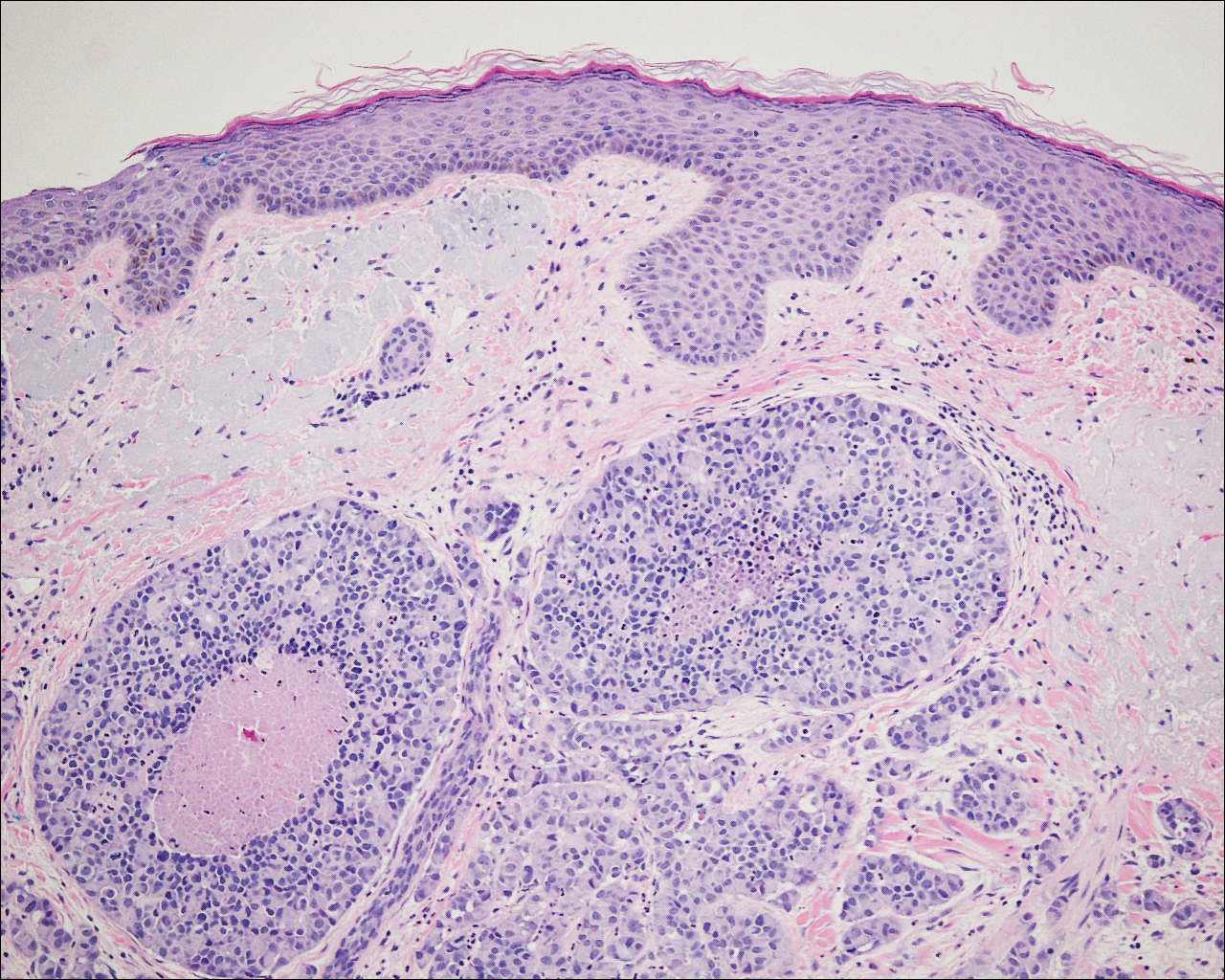

Physical examination revealed 2 tender, sharply defined, angulated erosions with irregular violaceous borders involving the perianal skin (Figure 1). A biopsy of one of the lesions was taken. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis of the epidermis with slight compact hyperkeratosis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obliterated the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of perianal erosive LP was made. The patient was prescribed mometasone ointment 0.1% daily with notable improvement after 2 months.

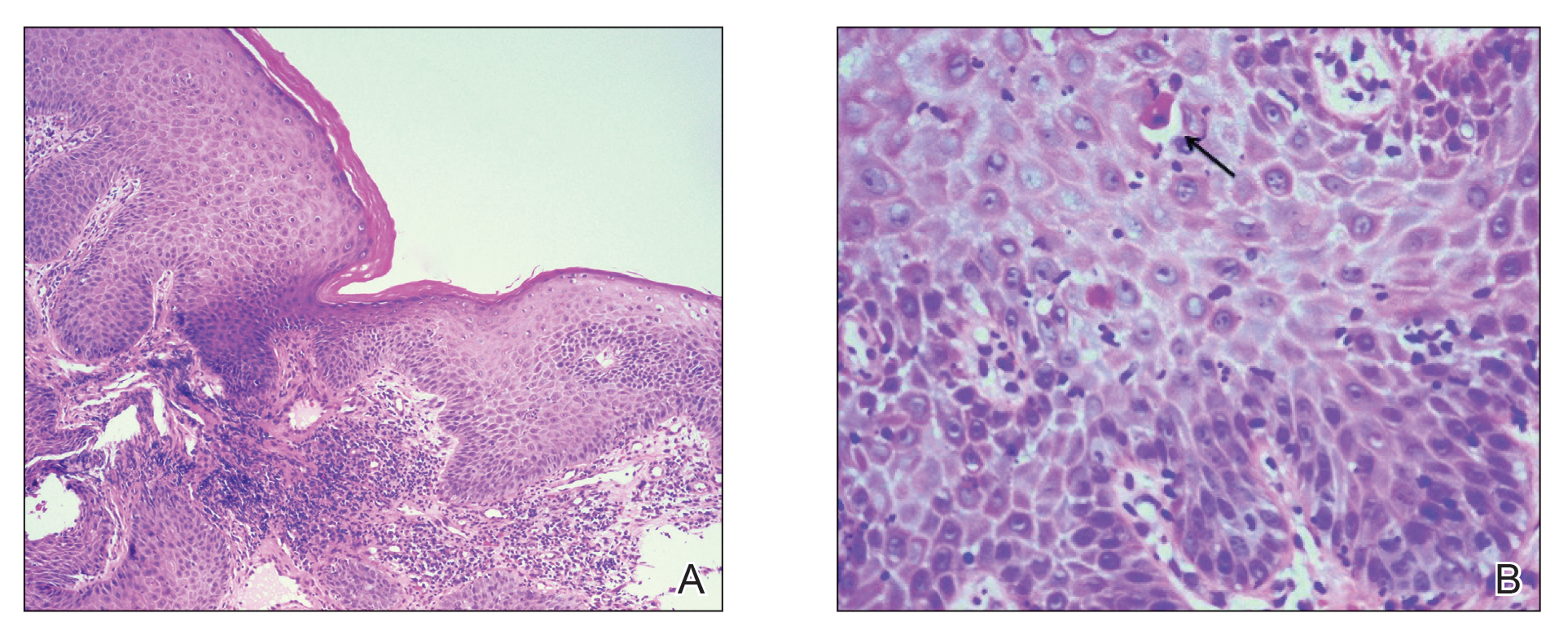

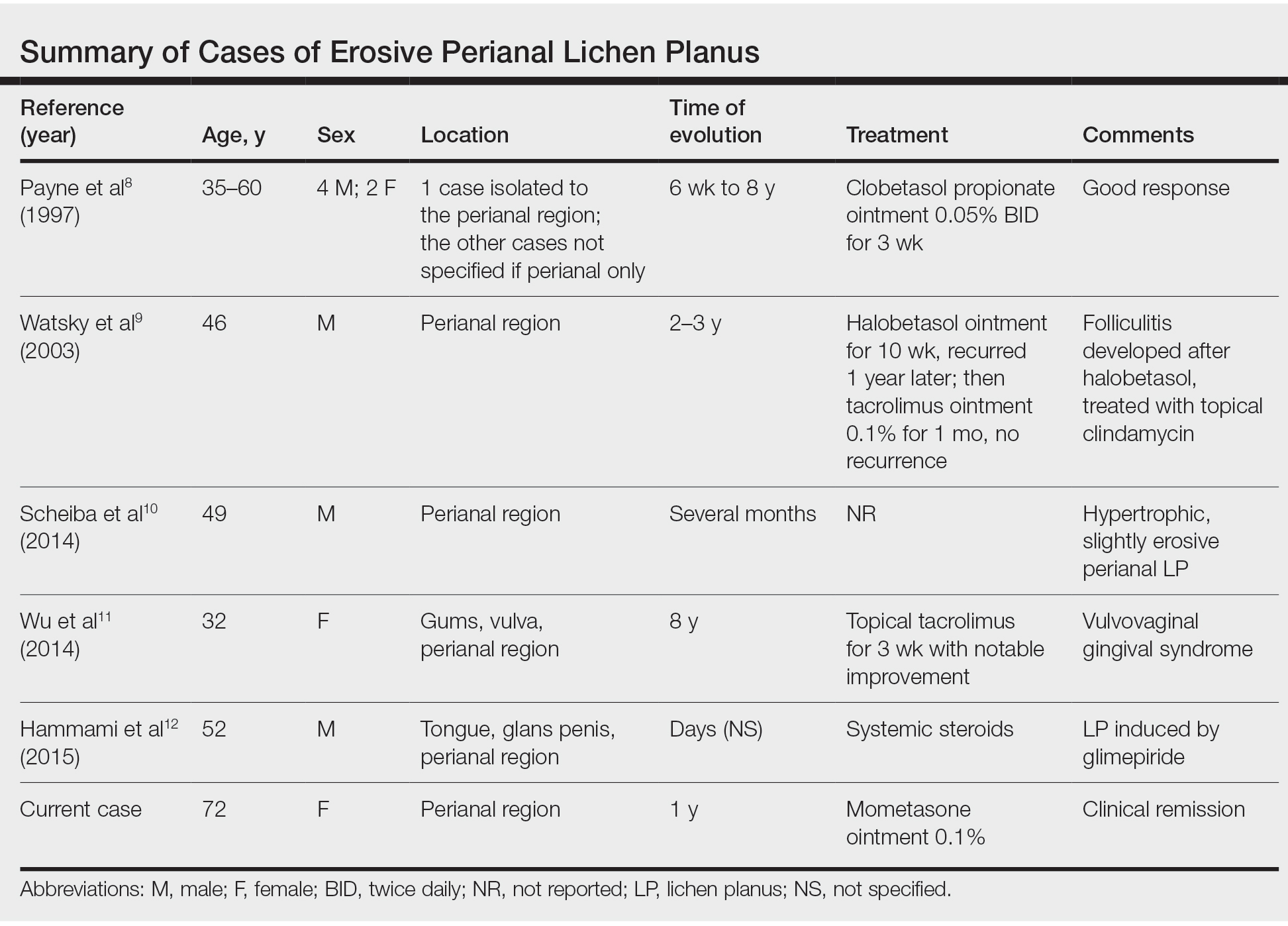

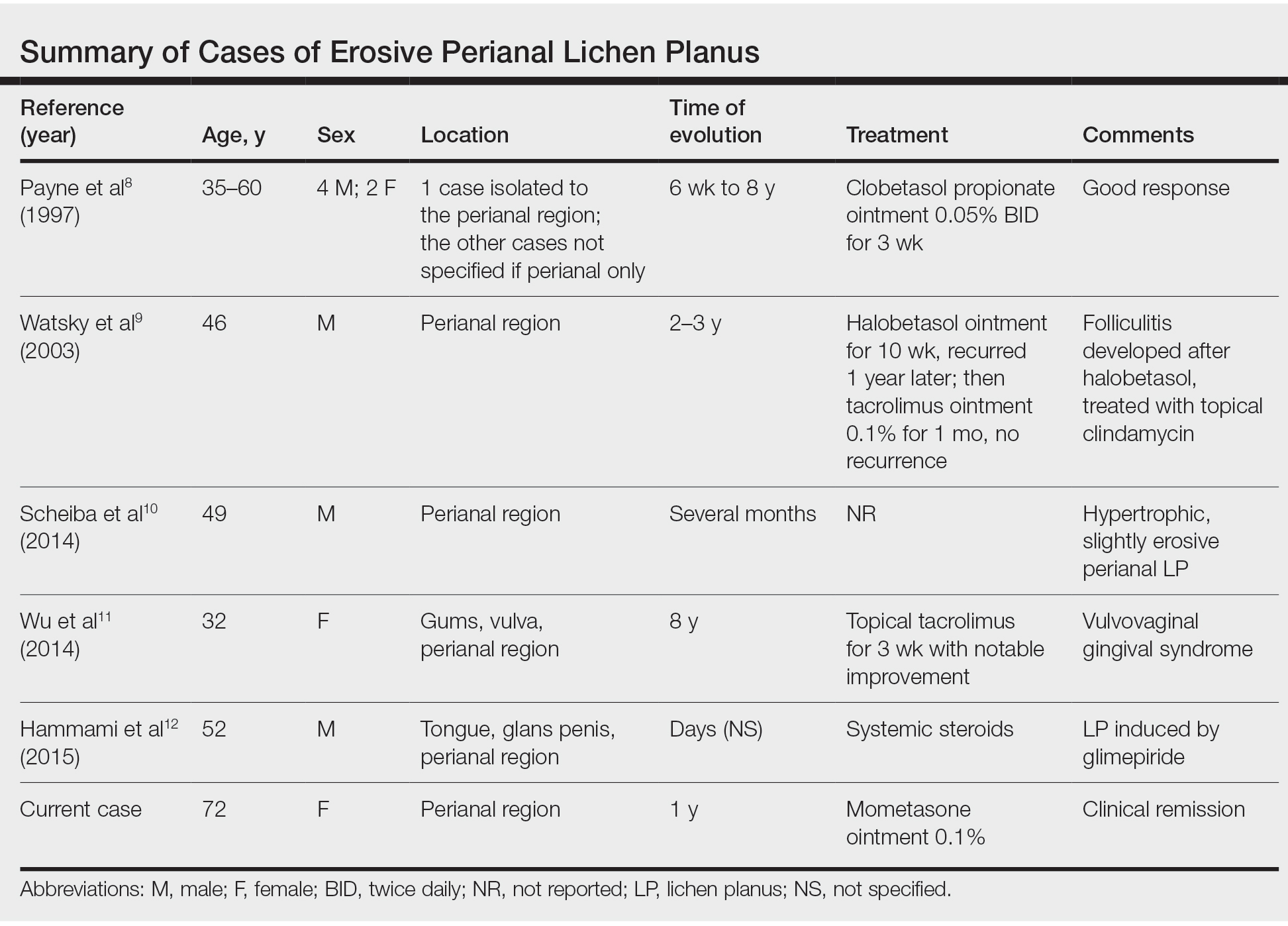

Erosive LP is an extremely rare variant of LP.1 It typically manifests as chronic painful erosions that often can progress to scarring, ulceration, and tissue destruction. Although erosive LP most commonly involves the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia and oral mucosa, it also has been reported in the palmoplantar skin, lacrimal duct, external auditory meatus, and esophagus.2-7 However, isolated perianal involvement is extremely rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erosive or ulcerative and lichen planus and perianal revealed 10 cases of perianal erosive LP, and weak data exist regarding therapy (Table).8-12 Of these cases, only 3 reported isolated perianal involvement.8-10 In most reported cases, perianal involvement manifested as extremely painful and occasionally pruritic, sharply angulated erosions and ulcers arising 0.5 to 3 cm from the anus with macerated, whitish, and violaceous borders. Most of the lesions occurred unilaterally, with only 1 case of bilateral perianal involvement.10

The differential diagnosis of perianal erosions is extensive and includes cutaneous Crohn disease, extramammary Paget disease, cutaneous malignancy, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, external hemorrhoids, lichen sclerosus, Behçet disease, lichen simplex chronicus, and drug-induced lichenoid reaction, among others. It is worth emphasizing infectious processes and cutaneous malignancies in light of our patient’s immunosuppression. Perianal cytomegalovirus has been reported in the literature in association with HIV, and it is a clinically challenging diagnosis.13 Cutaneous malignancy associated with the use of methotrexate also was considered in the differential diagnosis for our patient, given the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer with the use of immunosuppresants.14

Along with a thorough patient history and physical examination, skin biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation are key to determine the exact etiology. Histologically, LP is characterized by a lichenoid interface dermatitis with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Other distinguishing factors include irregular acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, basal cell vacuolar degeneration, and Civatte bodies. Drug-induced LP is a possibility, but it is unclear if abatacept or lisinopril may have played a role in our patient. However, absence of eosinophils and parakeratosis suggested an idiopathic rather than drug-induced etiology. In 2016, Day et al2 published a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases of perianal lichenoid dermatoses in which only 17% of lesions were LP. Of note, 90% of perianal LP lesions were of the hypertrophic variant, and none were of the erosive variant, further supporting that our case represents a rare clinical manifestation of perianal LP.

Treatment of LP varies depending on the location and subtype of the lesions and is primarily aimed at improving symptoms. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment of LP; however, there is limited evidence regarding their efficacy for mucosal LP. Although randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of different interventions on oral erosive LP are available in the literature,15 there is a paucity of studies addressing this topic for genital or perianal LP. A review of the literature regarding perianal erosive LP suggests good response to high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors with resolution of lesions within 3 to 4 weeks.11,15-18

Erosive LP is a painful variant that can cause erosions, ulcerations, and scarring. It rarely is seen in the perianal region alone and presents a diagnostic challenge. Treatment with high-potency topical steroid therapy seems to be effective in the few cases that have been reported as well as in our case. More comprehensive data from randomized controlled trials would be needed to evaluate their efficacy compared to other therapies.

- Rebora A. Erosive lichen planus: what is this? Dermatology. 2002;205:226-228; discussion 227.

- Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: a review of 60 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:210-215.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-883.

- Holmstrup P, Thorn JJ, Rindum J, et al. Malignant development of lichen planus-affected oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:219-225.

- Lewi, FM, Bogliatto F. Erosive vulval lichen planus—a diagnosis not to be missed: a clinical review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171:214-219.

- Webber NK, Setterfield JF, Lewis FM, et al. Lacrimal canalicular duct scarring in patients with lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:224-227.

- Martin L, Moriniere S, Machet MC, et al. Bilateral conductive deafness related to erosive lichen planus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:365-366.

- Payne CM, McPartlin JF, Hawley PR. Ulcerative perianal lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:479.

- Watsky KL. Erosive perianal lichen planus responsive to tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:217-218.

- Scheiba N, Toberer F, Lenhard BH, et al. Erythema and erosions of the perianal region in a 49-year-old man. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:162-165.

- Wu Y, Qiao J, Fang H. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:843-844.

- Hammami S, Ksouda K, Affes H, et al. Mucosal lichenoid drug reaction associated with glimepiride: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2301-2302.

- Meyerle JH, Turiansky GW. Perianal ulcer in a patient with AIDS. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:877-882.

- Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with the use of immunosuppressant and biologic agents in patients with a history of autoimmune disease and nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:164-172.

- Cheng S, Kirtschig G, Cooper S, et al. Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:Cd008092.

- Gunther S. Effect of retinoic acid in lichen planus of the genitalia and perianal region. Br J Vener Dis. 1973;49:553-554.

- Vente C, Reich K, Neumann C. Erosive mucosal lichen planus: response to topical treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:338-342.

- Lonsdale-Eccles AA, Velangi S. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of genital lichen planus: a prospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:390-394.

To the Editor:

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple pruritic and painful perianal lesions of 1 year’s duration. The lesions had remained stable since onset, with no other reported lesions elsewhere on body, including the mucosae. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. She was taking methotrexate, folic acid, abatacept, alendronate, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. The patient reported she had been using abatacept for 3 years and lisinopril for 2 years. Her primary care physician initially treated the lesions as hemorrhoids but referred her to a gastroenterologist when they failed to improve. Gastroenterology evaluated the patient, and a colonoscopy was performed with unremarkable results. Thus, she was referred to dermatology for further evaluation.

Physical examination revealed 2 tender, sharply defined, angulated erosions with irregular violaceous borders involving the perianal skin (Figure 1). A biopsy of one of the lesions was taken. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis of the epidermis with slight compact hyperkeratosis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obliterated the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of perianal erosive LP was made. The patient was prescribed mometasone ointment 0.1% daily with notable improvement after 2 months.

Erosive LP is an extremely rare variant of LP.1 It typically manifests as chronic painful erosions that often can progress to scarring, ulceration, and tissue destruction. Although erosive LP most commonly involves the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia and oral mucosa, it also has been reported in the palmoplantar skin, lacrimal duct, external auditory meatus, and esophagus.2-7 However, isolated perianal involvement is extremely rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erosive or ulcerative and lichen planus and perianal revealed 10 cases of perianal erosive LP, and weak data exist regarding therapy (Table).8-12 Of these cases, only 3 reported isolated perianal involvement.8-10 In most reported cases, perianal involvement manifested as extremely painful and occasionally pruritic, sharply angulated erosions and ulcers arising 0.5 to 3 cm from the anus with macerated, whitish, and violaceous borders. Most of the lesions occurred unilaterally, with only 1 case of bilateral perianal involvement.10

The differential diagnosis of perianal erosions is extensive and includes cutaneous Crohn disease, extramammary Paget disease, cutaneous malignancy, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, external hemorrhoids, lichen sclerosus, Behçet disease, lichen simplex chronicus, and drug-induced lichenoid reaction, among others. It is worth emphasizing infectious processes and cutaneous malignancies in light of our patient’s immunosuppression. Perianal cytomegalovirus has been reported in the literature in association with HIV, and it is a clinically challenging diagnosis.13 Cutaneous malignancy associated with the use of methotrexate also was considered in the differential diagnosis for our patient, given the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer with the use of immunosuppresants.14

Along with a thorough patient history and physical examination, skin biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation are key to determine the exact etiology. Histologically, LP is characterized by a lichenoid interface dermatitis with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Other distinguishing factors include irregular acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, basal cell vacuolar degeneration, and Civatte bodies. Drug-induced LP is a possibility, but it is unclear if abatacept or lisinopril may have played a role in our patient. However, absence of eosinophils and parakeratosis suggested an idiopathic rather than drug-induced etiology. In 2016, Day et al2 published a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases of perianal lichenoid dermatoses in which only 17% of lesions were LP. Of note, 90% of perianal LP lesions were of the hypertrophic variant, and none were of the erosive variant, further supporting that our case represents a rare clinical manifestation of perianal LP.

Treatment of LP varies depending on the location and subtype of the lesions and is primarily aimed at improving symptoms. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment of LP; however, there is limited evidence regarding their efficacy for mucosal LP. Although randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of different interventions on oral erosive LP are available in the literature,15 there is a paucity of studies addressing this topic for genital or perianal LP. A review of the literature regarding perianal erosive LP suggests good response to high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors with resolution of lesions within 3 to 4 weeks.11,15-18

Erosive LP is a painful variant that can cause erosions, ulcerations, and scarring. It rarely is seen in the perianal region alone and presents a diagnostic challenge. Treatment with high-potency topical steroid therapy seems to be effective in the few cases that have been reported as well as in our case. More comprehensive data from randomized controlled trials would be needed to evaluate their efficacy compared to other therapies.

To the Editor:

Erosive lichen planus (LP) often is painful, debilitating, and resistant to topical therapy making it both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of an elderly woman with isolated perianal erosive LP, a rare clinical manifestation. We also review cases of erosive perianal LP reported in the literature.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple pruritic and painful perianal lesions of 1 year’s duration. The lesions had remained stable since onset, with no other reported lesions elsewhere on body, including the mucosae. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. She was taking methotrexate, folic acid, abatacept, alendronate, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. The patient reported she had been using abatacept for 3 years and lisinopril for 2 years. Her primary care physician initially treated the lesions as hemorrhoids but referred her to a gastroenterologist when they failed to improve. Gastroenterology evaluated the patient, and a colonoscopy was performed with unremarkable results. Thus, she was referred to dermatology for further evaluation.

Physical examination revealed 2 tender, sharply defined, angulated erosions with irregular violaceous borders involving the perianal skin (Figure 1). A biopsy of one of the lesions was taken. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis of the epidermis with slight compact hyperkeratosis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that obliterated the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of perianal erosive LP was made. The patient was prescribed mometasone ointment 0.1% daily with notable improvement after 2 months.

Erosive LP is an extremely rare variant of LP.1 It typically manifests as chronic painful erosions that often can progress to scarring, ulceration, and tissue destruction. Although erosive LP most commonly involves the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia and oral mucosa, it also has been reported in the palmoplantar skin, lacrimal duct, external auditory meatus, and esophagus.2-7 However, isolated perianal involvement is extremely rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erosive or ulcerative and lichen planus and perianal revealed 10 cases of perianal erosive LP, and weak data exist regarding therapy (Table).8-12 Of these cases, only 3 reported isolated perianal involvement.8-10 In most reported cases, perianal involvement manifested as extremely painful and occasionally pruritic, sharply angulated erosions and ulcers arising 0.5 to 3 cm from the anus with macerated, whitish, and violaceous borders. Most of the lesions occurred unilaterally, with only 1 case of bilateral perianal involvement.10

The differential diagnosis of perianal erosions is extensive and includes cutaneous Crohn disease, extramammary Paget disease, cutaneous malignancy, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, external hemorrhoids, lichen sclerosus, Behçet disease, lichen simplex chronicus, and drug-induced lichenoid reaction, among others. It is worth emphasizing infectious processes and cutaneous malignancies in light of our patient’s immunosuppression. Perianal cytomegalovirus has been reported in the literature in association with HIV, and it is a clinically challenging diagnosis.13 Cutaneous malignancy associated with the use of methotrexate also was considered in the differential diagnosis for our patient, given the increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer with the use of immunosuppresants.14

Along with a thorough patient history and physical examination, skin biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation are key to determine the exact etiology. Histologically, LP is characterized by a lichenoid interface dermatitis with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Other distinguishing factors include irregular acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, basal cell vacuolar degeneration, and Civatte bodies. Drug-induced LP is a possibility, but it is unclear if abatacept or lisinopril may have played a role in our patient. However, absence of eosinophils and parakeratosis suggested an idiopathic rather than drug-induced etiology. In 2016, Day et al2 published a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases of perianal lichenoid dermatoses in which only 17% of lesions were LP. Of note, 90% of perianal LP lesions were of the hypertrophic variant, and none were of the erosive variant, further supporting that our case represents a rare clinical manifestation of perianal LP.

Treatment of LP varies depending on the location and subtype of the lesions and is primarily aimed at improving symptoms. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment of LP; however, there is limited evidence regarding their efficacy for mucosal LP. Although randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of different interventions on oral erosive LP are available in the literature,15 there is a paucity of studies addressing this topic for genital or perianal LP. A review of the literature regarding perianal erosive LP suggests good response to high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors with resolution of lesions within 3 to 4 weeks.11,15-18

Erosive LP is a painful variant that can cause erosions, ulcerations, and scarring. It rarely is seen in the perianal region alone and presents a diagnostic challenge. Treatment with high-potency topical steroid therapy seems to be effective in the few cases that have been reported as well as in our case. More comprehensive data from randomized controlled trials would be needed to evaluate their efficacy compared to other therapies.

- Rebora A. Erosive lichen planus: what is this? Dermatology. 2002;205:226-228; discussion 227.

- Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: a review of 60 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:210-215.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-883.

- Holmstrup P, Thorn JJ, Rindum J, et al. Malignant development of lichen planus-affected oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:219-225.

- Lewi, FM, Bogliatto F. Erosive vulval lichen planus—a diagnosis not to be missed: a clinical review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171:214-219.

- Webber NK, Setterfield JF, Lewis FM, et al. Lacrimal canalicular duct scarring in patients with lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:224-227.

- Martin L, Moriniere S, Machet MC, et al. Bilateral conductive deafness related to erosive lichen planus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:365-366.

- Payne CM, McPartlin JF, Hawley PR. Ulcerative perianal lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:479.

- Watsky KL. Erosive perianal lichen planus responsive to tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:217-218.

- Scheiba N, Toberer F, Lenhard BH, et al. Erythema and erosions of the perianal region in a 49-year-old man. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:162-165.

- Wu Y, Qiao J, Fang H. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:843-844.

- Hammami S, Ksouda K, Affes H, et al. Mucosal lichenoid drug reaction associated with glimepiride: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2301-2302.

- Meyerle JH, Turiansky GW. Perianal ulcer in a patient with AIDS. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:877-882.

- Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with the use of immunosuppressant and biologic agents in patients with a history of autoimmune disease and nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:164-172.

- Cheng S, Kirtschig G, Cooper S, et al. Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:Cd008092.

- Gunther S. Effect of retinoic acid in lichen planus of the genitalia and perianal region. Br J Vener Dis. 1973;49:553-554.

- Vente C, Reich K, Neumann C. Erosive mucosal lichen planus: response to topical treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:338-342.

- Lonsdale-Eccles AA, Velangi S. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of genital lichen planus: a prospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:390-394.

- Rebora A. Erosive lichen planus: what is this? Dermatology. 2002;205:226-228; discussion 227.

- Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: a review of 60 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:210-215.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-883.

- Holmstrup P, Thorn JJ, Rindum J, et al. Malignant development of lichen planus-affected oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:219-225.

- Lewi, FM, Bogliatto F. Erosive vulval lichen planus—a diagnosis not to be missed: a clinical review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171:214-219.

- Webber NK, Setterfield JF, Lewis FM, et al. Lacrimal canalicular duct scarring in patients with lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:224-227.

- Martin L, Moriniere S, Machet MC, et al. Bilateral conductive deafness related to erosive lichen planus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:365-366.

- Payne CM, McPartlin JF, Hawley PR. Ulcerative perianal lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:479.

- Watsky KL. Erosive perianal lichen planus responsive to tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:217-218.

- Scheiba N, Toberer F, Lenhard BH, et al. Erythema and erosions of the perianal region in a 49-year-old man. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:162-165.

- Wu Y, Qiao J, Fang H. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:843-844.

- Hammami S, Ksouda K, Affes H, et al. Mucosal lichenoid drug reaction associated with glimepiride: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:2301-2302.

- Meyerle JH, Turiansky GW. Perianal ulcer in a patient with AIDS. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:877-882.

- Scott FI, Mamtani R, Brensinger CM, et al. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with the use of immunosuppressant and biologic agents in patients with a history of autoimmune disease and nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:164-172.

- Cheng S, Kirtschig G, Cooper S, et al. Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:Cd008092.

- Gunther S. Effect of retinoic acid in lichen planus of the genitalia and perianal region. Br J Vener Dis. 1973;49:553-554.

- Vente C, Reich K, Neumann C. Erosive mucosal lichen planus: response to topical treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:338-342.

- Lonsdale-Eccles AA, Velangi S. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of genital lichen planus: a prospective case series. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:390-394.

Practice Points

- Erosive lichen planus (LP) is an underrecognized variant of LP presenting with painful erosions, ulcerations, and scarring.

- Although rare, perianal erosive LP should be included in the differential diagnosis of perianal erosions.

- Treatment with high-potency steroids is an effective therapeutic option resulting in notable improvement.

Cutaneous Metastasis of a Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumor

Case Report

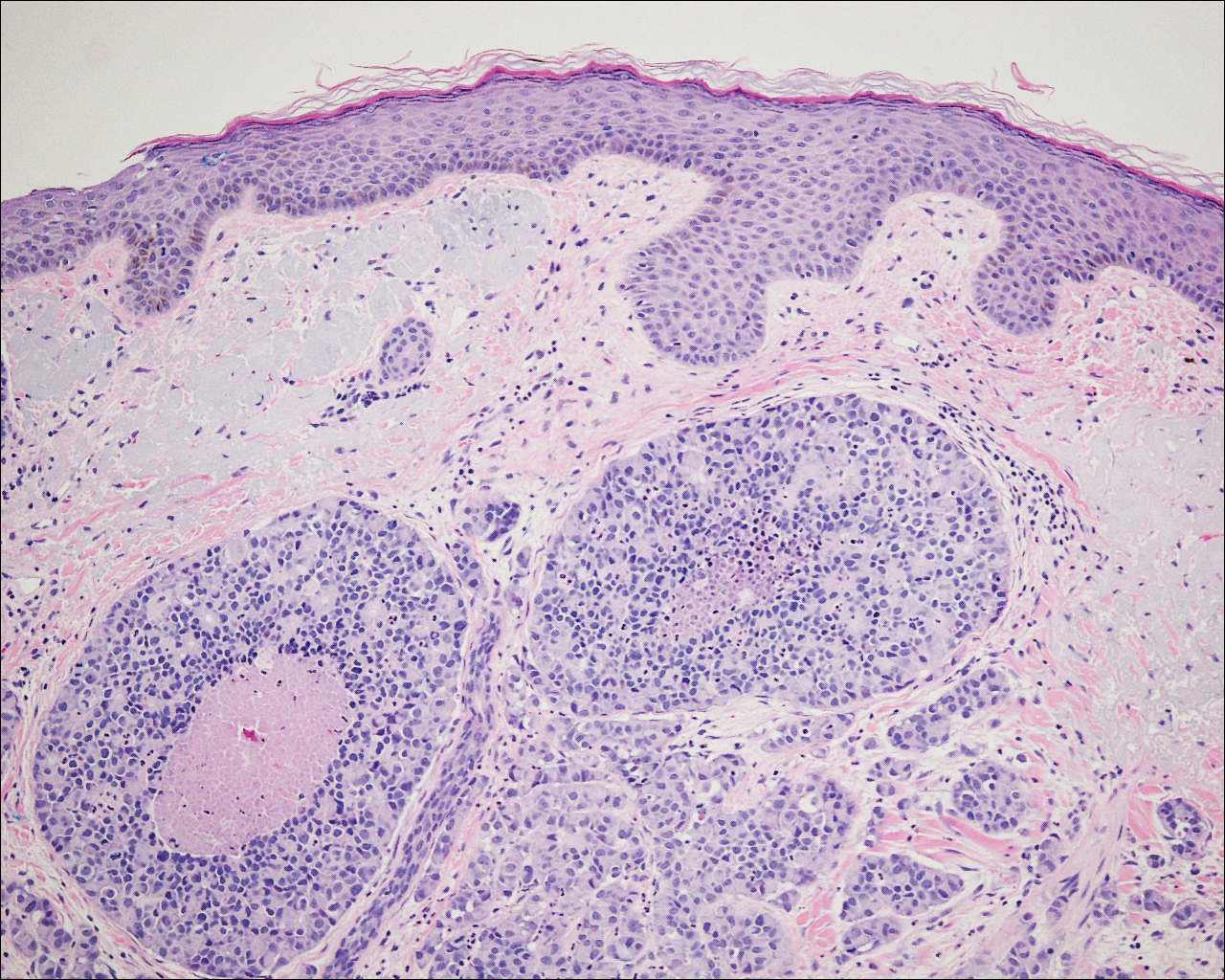

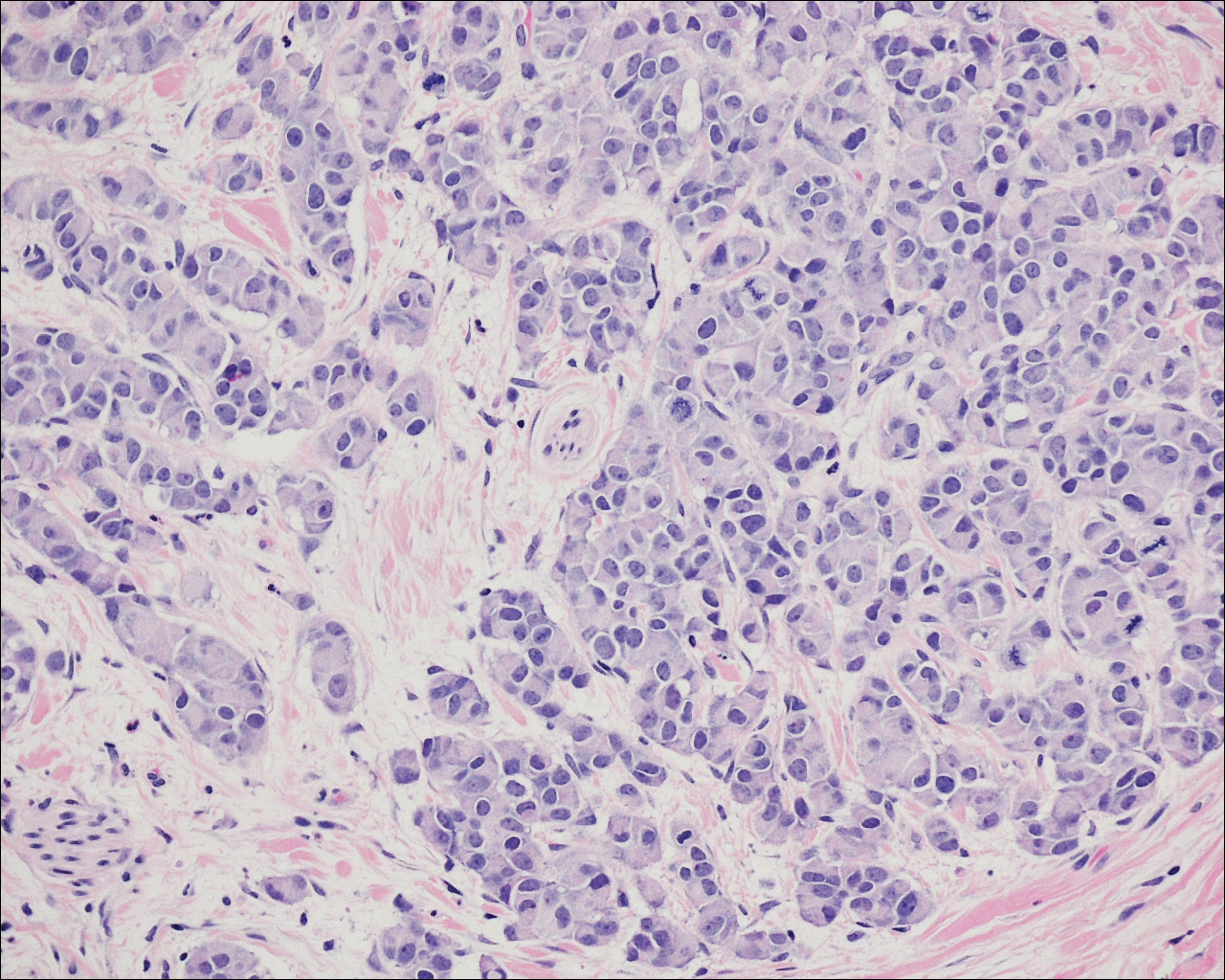

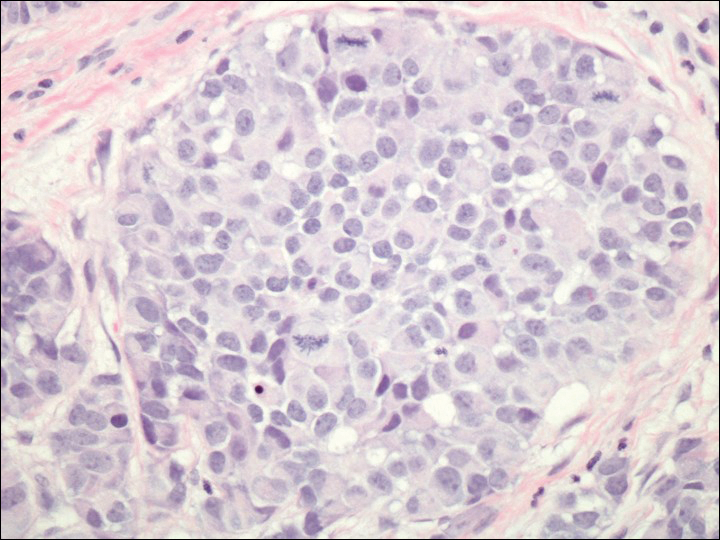

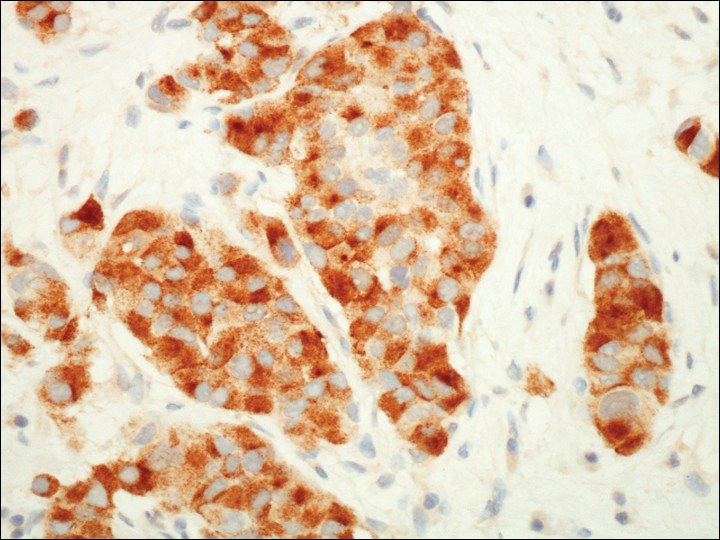

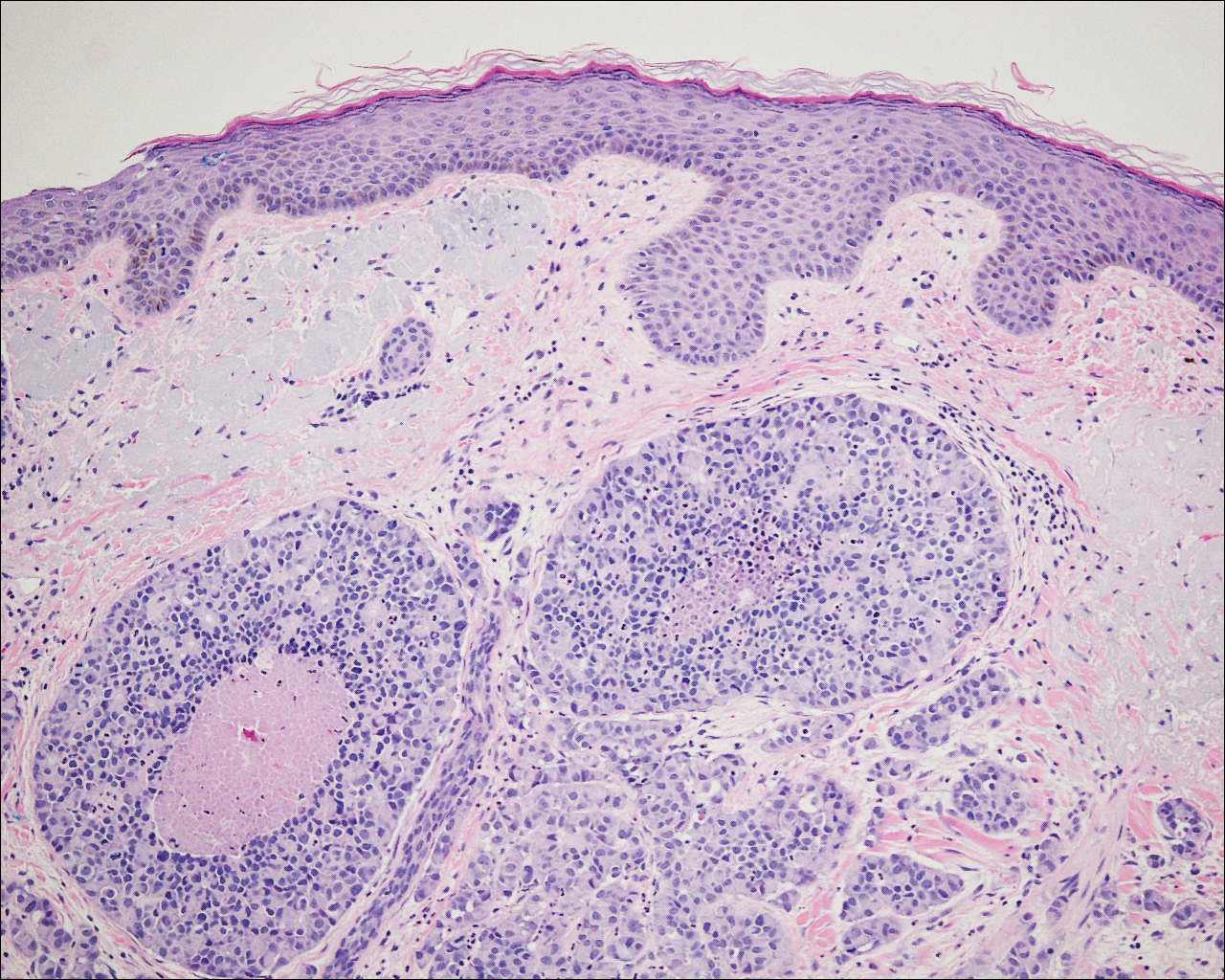

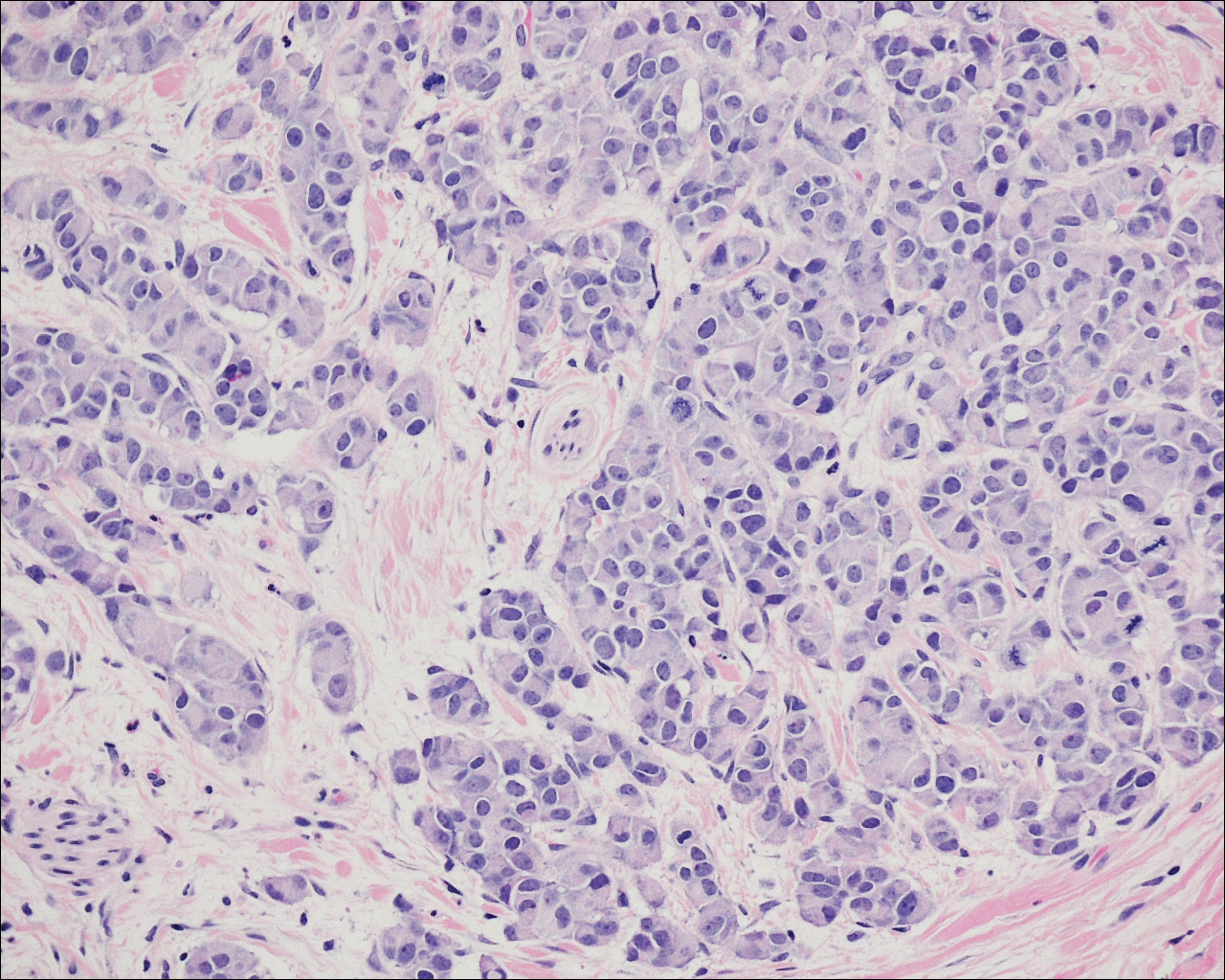

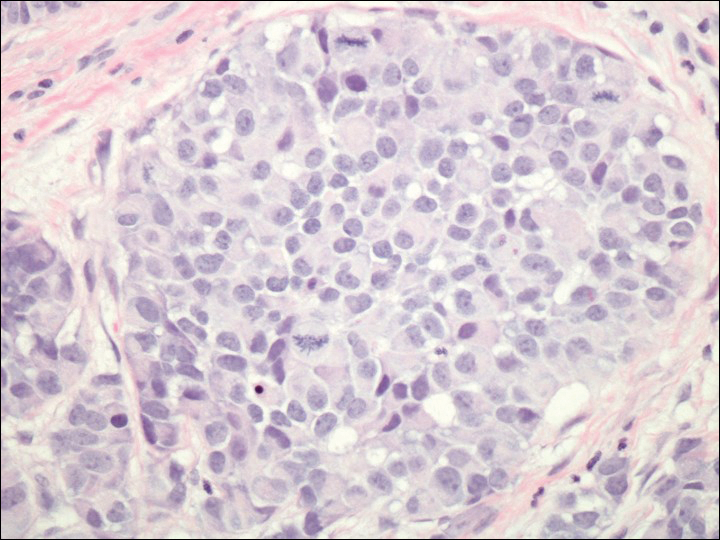

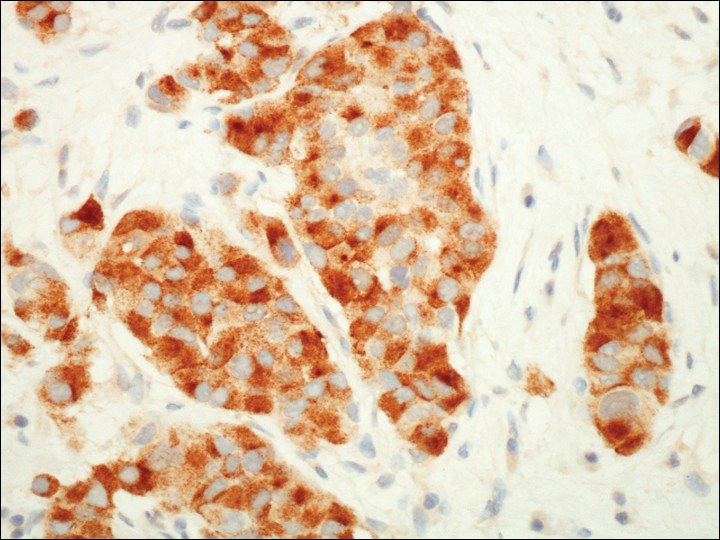

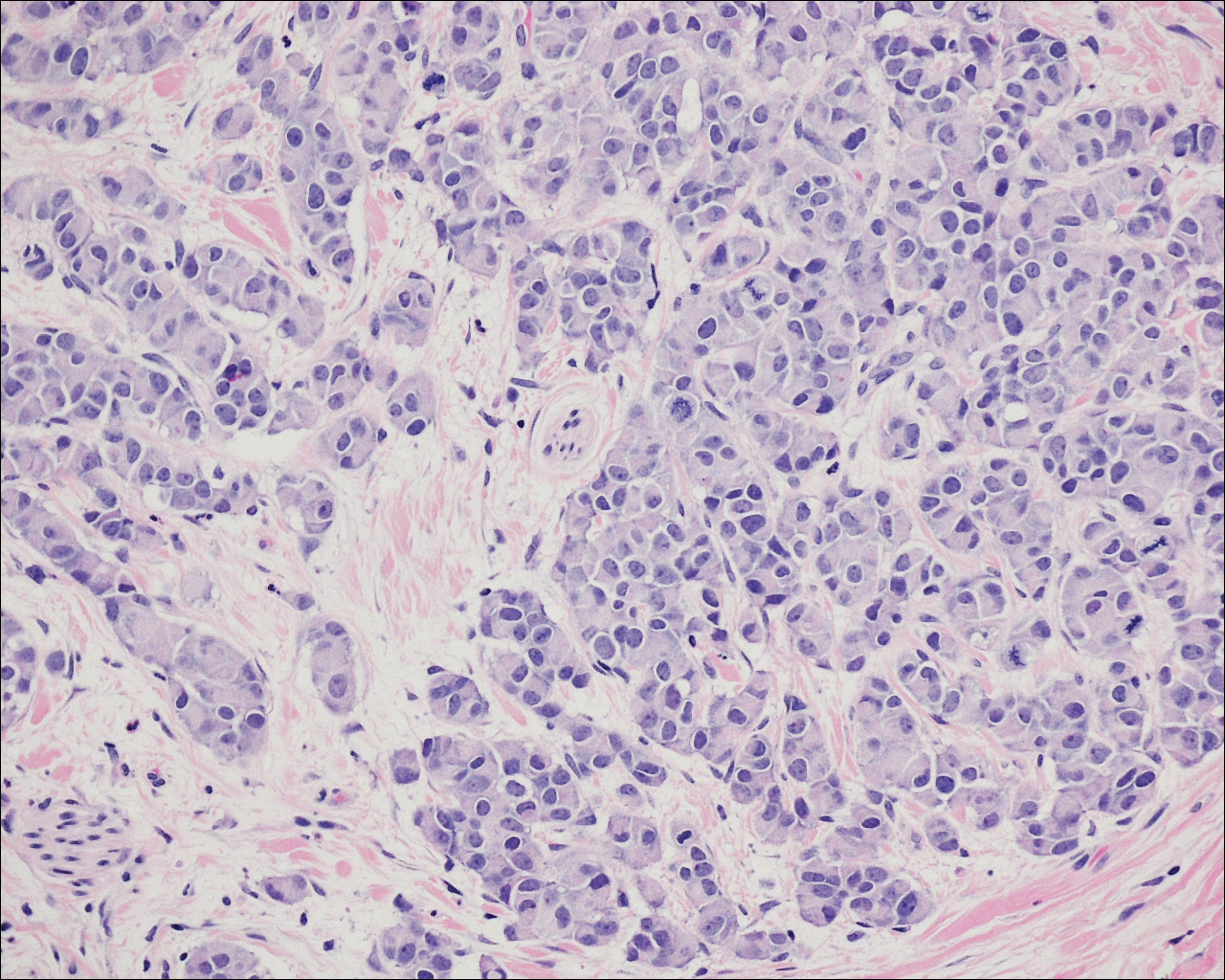

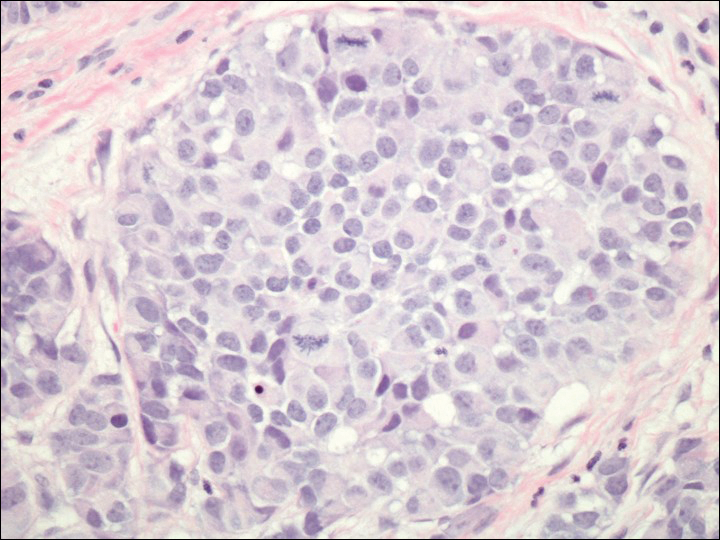

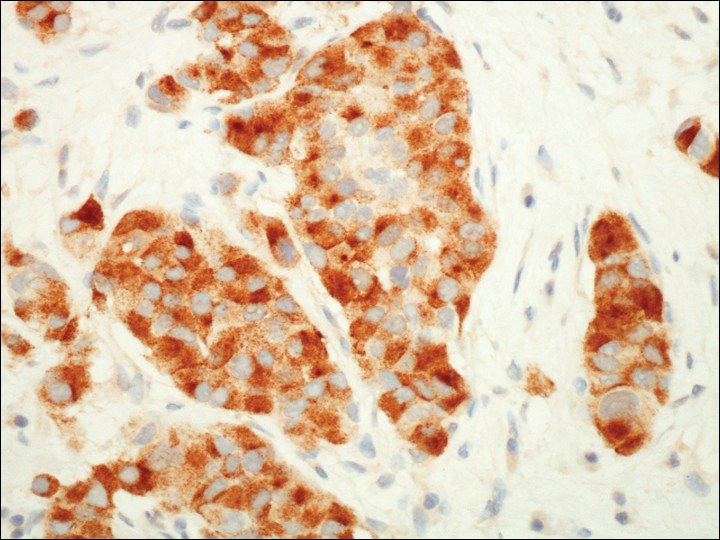

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are extremely rare, and clinical presentation can vary. They can present as firm papules ranging in color from pink to brown, can be painful, and could occur at any site.

- It is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors.

- Neoplasms within the gastrointestinal tract commonly present with carcinoid syndrome, but it also has been observed with bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.