User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

Minimal Dissection Reduces Herniation After Pediatric Fundoplication

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

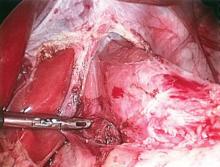

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

Minimal Dissection Reduces Herniation After Pediatric Fundoplication

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.

Thus far, they have enrolled 35 patients in a randomized trial aiming for a total enrollment of 120 patients. Half will get the sutures; the other half will not. But all the children will leave the OR with their esophageal attachments intact.

"The second we closed the study, that was the last time we took down a membrane," Dr. St. Peter said.

He and Dr. Moss said they have no conflicts of interest. The trial received no outside funding.

Major Finding: The risk of postop fundal wrap herniation is greatly reduced when the esophagus is not freed from the phrenoesophageal membrane during pediatric fundoplication.

Data Source: Prospective, randomized trial involving 177 children.

Disclosures: Dr. St. Peter said he has no conflicts of interest; the study received no outside funding.

Study Casts Doubt on Need for High-Dose Perioperative Steroids

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Study Casts Doubt on Need for High-Dose Perioperative Steroids

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – For the past several decades, surgical patients have been given supraphysiologic perioperative steroid doses to prevent cardiovascular collapse, but results of a recent pilot study suggest it’s time to rethink the high-dose dogma.

There were two case reports in the 1950s of cardiovascular collapse and death in patients who were abruptly taken off steroids just before surgery (JAMA 1952;149:1542-3; Ann. Intern. Med. 1953;39:116-26).

"We don’t know what exactly happened to those patients, [but] if you look at a lot of the surgical textbooks, they’ll recommend high-dose steroids," sometimes in the range of 100-mg IV hydrocortisone every 8 hours, explained Dr. Karen Zaghiyan, a surgery resident at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview.

The problem is that steroids pose risks such as wound infection and delayed healing, plus hypertension, hyperglycemia, and psychosis, among others.

Until now, there’s been "no good evidence to support [the move] one way or the other," Dr. Zaghiyan said.

She and her colleagues at Cedars-Sinai eschewed high-dose perioperative steroids in 26 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients who underwent 32 colorectal procedures, including 10 ileocolic resections and 9 ileal pouch anal anastomoses. Dr. Zaghiyan presented the results of their study at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The patients’ median age was 40 years, and 19 were men.

In all, 22 operations were done on patients who had been off steroids 1-12 months (median, 6 months); those patients got no perioperative steroids. Ten operations were done on patients taking 5-40 mg of prednisone daily (median, 23 mg); those patients remained on the IV hydrocortisone equivalent of their customary dose, followed by a postoperative taper.

There was no cardiovascular collapse in the perioperative period, and there was no need for vasopressors or steroid rescue. Although there were hemodynamic problems, they did not appear to be related to adrenal insufficiency.

Three patients became hypotensive because of operative or postoperative bleeding; their systolic blood pressure dropped below 90 mmHg, but they responded to transfusions. Another case of hypotension responded to fluid bolus; a fifth resolved on its own and may have been the result of a faulty blood pressure reading.

Heart rates temporarily topped 120 beats per minute in five patients and fell below 60 bpm in eight; the tachy- and bradycardia were not associated with hypotension, and resolved without intervention.

Temperatures climbed above 100.4° F in nine patients, but fevers resolved with simple cooling measures or acetaminophen. There was no hypothermia.

If any of those problems were caused by adrenal insufficiency, resolving them would have required steroids, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

"Steroid-treated IBD patients undergoing major colorectal surgery appear to have no clinically significant hemodynamic instability when treated with low-dose perioperative steroids. Management of these patients with perioperative low-dose steroids appears to be safe," Dr. Zaghiyan concluded.

The findings did not surprise Dr. Stefan Holubar, a colorectal surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., who has been trying low-dose steroids in his own IBD surgical cases.

"I thought [this study] was really fantastic. It adds some evidence" to a practice that is gaining acceptance among colorectal surgeons after "being adopted from the transplant literature. It hasn’t really been studied in colorectal surgery," Dr. Holubar said.

"I think we overtreat patients with steroids," but although it may be okay to give low-dose steroids, it may be inappropriate to give nothing, he said, adding that more research is needed.

Dr. Zaghiyan and her colleagues have begun to enroll 120 IBD patients into a prospective trial that will randomize patients to low- or high-dose perioperative steroids. In addition to hemodynamic instability, they will investigate more subtle signs of adrenal insufficiency, including nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.

They plan to publish their interim results later this year.

Dr. Zaghiyan and Dr. Holubar said they have no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Major Finding: IBD patients did not develop hemodynamic instability related to adrenal insufficiency when they underwent colorectal surgery without high-dose perioperative steroids.

Data Source: Retrospective study of 26 steroid-dependent or recently dependent patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Zaghiyan said she has no conflicts of interest.

Cadaver Artery Grafts May Help Save Limbs

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.

The findings add weight to the small body of literature showing that homografts can help in such cases.

The patients’ average age was 71 years, and five were men. Comorbidities included peripheral vascular disease (12 patients), diabetes (7), foot infections or gangrene (10), foot ischemia but no wound (2), and an infected Gore-Tex graft (1).

Dr. Naoum said he chose arterial homografts instead of vein homografts to cut down potential graft complications; arteries have more uniform diameters and no valves.

Four patients got femoral below-the-knee popliteal grafts; four had femoral- to anterior-tibial-artery grafts; and three had femoral- to posterior-tibial-artery grafts. Two patients received femoral- to peroneal-artery grafts.

Only patients who could tolerate the surgery, which is a longer and more complicated procedure than leg amputation, and who were currently ambulatory underwent the procedure.

"There is no point using these homografts to preserve limbs if patients are not walking," Dr Naoum noted.

The grafts cost about $3,000 and range in length from about 25 to 35 cm, depending on the donor.

"We like to ask for the longest piece possible," to avoid splicing. "However, we get what is available based on the diameter requested and blood-type match," Dr. Naoum said.

Once thawed per supplier directions, the homografts handle like any other graft tissue. Suturing is standard.

Dr. Naoum said he and some of his colleagues like to tunnel the grafts under subcutaneous fat instead of anatomically, to minimize compression. They also prefer to arterialize the graft before making the distal anastomoses to elongate the graft for better sizing and to work out any kinks, he said.

Patients were told to stop smoking after their operations (five of them smoked), and they were put on aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), and a statin, if they were not on one already. There’s no evidence that antirejection drugs are needed, Dr. Naoum said.

Two patients later needed toe amputations, and four required transmetatarsal amputations.

The 18-month patency rate was less than the perhaps 75% patency rate that would be expected had they been grafted with their own veins. Even so, the restored blood flow "was enough to allow the wounds to heal," Dr. Naoum said.

He said he plans to continue studying the use of arterial homografts to better define factors associated with good outcomes.

"What is needed is a greater experience to identify patients who will benefit most from such procedures, and those in whom an amputation may obviate a bypass that will not last," he said.

Dr. Naoum is also curious about why the grafts fail; two patients needed angioplasty to keep their grafts open, and thrombectomy was performed in one.

Cryopreservation makes cells thicker, perhaps causing intimal tears and scarring. Poor runoff is also a problem. If distal vessels can’t handle the new blood flow, pressure builds up in the graft, leading to clots and other problems, he said.

Dr. Naoum said that he was a consultant for CryoLife Inc., a major supplier of arterial homografts, in 2009, but is no longer involved with the company. He said he received no discounts on the grafts used in the case series.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.

The findings add weight to the small body of literature showing that homografts can help in such cases.

The patients’ average age was 71 years, and five were men. Comorbidities included peripheral vascular disease (12 patients), diabetes (7), foot infections or gangrene (10), foot ischemia but no wound (2), and an infected Gore-Tex graft (1).

Dr. Naoum said he chose arterial homografts instead of vein homografts to cut down potential graft complications; arteries have more uniform diameters and no valves.

Four patients got femoral below-the-knee popliteal grafts; four had femoral- to anterior-tibial-artery grafts; and three had femoral- to posterior-tibial-artery grafts. Two patients received femoral- to peroneal-artery grafts.

Only patients who could tolerate the surgery, which is a longer and more complicated procedure than leg amputation, and who were currently ambulatory underwent the procedure.

"There is no point using these homografts to preserve limbs if patients are not walking," Dr Naoum noted.

The grafts cost about $3,000 and range in length from about 25 to 35 cm, depending on the donor.

"We like to ask for the longest piece possible," to avoid splicing. "However, we get what is available based on the diameter requested and blood-type match," Dr. Naoum said.

Once thawed per supplier directions, the homografts handle like any other graft tissue. Suturing is standard.

Dr. Naoum said he and some of his colleagues like to tunnel the grafts under subcutaneous fat instead of anatomically, to minimize compression. They also prefer to arterialize the graft before making the distal anastomoses to elongate the graft for better sizing and to work out any kinks, he said.

Patients were told to stop smoking after their operations (five of them smoked), and they were put on aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), and a statin, if they were not on one already. There’s no evidence that antirejection drugs are needed, Dr. Naoum said.

Two patients later needed toe amputations, and four required transmetatarsal amputations.

The 18-month patency rate was less than the perhaps 75% patency rate that would be expected had they been grafted with their own veins. Even so, the restored blood flow "was enough to allow the wounds to heal," Dr. Naoum said.

He said he plans to continue studying the use of arterial homografts to better define factors associated with good outcomes.

"What is needed is a greater experience to identify patients who will benefit most from such procedures, and those in whom an amputation may obviate a bypass that will not last," he said.

Dr. Naoum is also curious about why the grafts fail; two patients needed angioplasty to keep their grafts open, and thrombectomy was performed in one.

Cryopreservation makes cells thicker, perhaps causing intimal tears and scarring. Poor runoff is also a problem. If distal vessels can’t handle the new blood flow, pressure builds up in the graft, leading to clots and other problems, he said.

Dr. Naoum said that he was a consultant for CryoLife Inc., a major supplier of arterial homografts, in 2009, but is no longer involved with the company. He said he received no discounts on the grafts used in the case series.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.

The findings add weight to the small body of literature showing that homografts can help in such cases.

The patients’ average age was 71 years, and five were men. Comorbidities included peripheral vascular disease (12 patients), diabetes (7), foot infections or gangrene (10), foot ischemia but no wound (2), and an infected Gore-Tex graft (1).

Dr. Naoum said he chose arterial homografts instead of vein homografts to cut down potential graft complications; arteries have more uniform diameters and no valves.

Four patients got femoral below-the-knee popliteal grafts; four had femoral- to anterior-tibial-artery grafts; and three had femoral- to posterior-tibial-artery grafts. Two patients received femoral- to peroneal-artery grafts.

Only patients who could tolerate the surgery, which is a longer and more complicated procedure than leg amputation, and who were currently ambulatory underwent the procedure.

"There is no point using these homografts to preserve limbs if patients are not walking," Dr Naoum noted.

The grafts cost about $3,000 and range in length from about 25 to 35 cm, depending on the donor.

"We like to ask for the longest piece possible," to avoid splicing. "However, we get what is available based on the diameter requested and blood-type match," Dr. Naoum said.

Once thawed per supplier directions, the homografts handle like any other graft tissue. Suturing is standard.

Dr. Naoum said he and some of his colleagues like to tunnel the grafts under subcutaneous fat instead of anatomically, to minimize compression. They also prefer to arterialize the graft before making the distal anastomoses to elongate the graft for better sizing and to work out any kinks, he said.

Patients were told to stop smoking after their operations (five of them smoked), and they were put on aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), and a statin, if they were not on one already. There’s no evidence that antirejection drugs are needed, Dr. Naoum said.

Two patients later needed toe amputations, and four required transmetatarsal amputations.

The 18-month patency rate was less than the perhaps 75% patency rate that would be expected had they been grafted with their own veins. Even so, the restored blood flow "was enough to allow the wounds to heal," Dr. Naoum said.

He said he plans to continue studying the use of arterial homografts to better define factors associated with good outcomes.

"What is needed is a greater experience to identify patients who will benefit most from such procedures, and those in whom an amputation may obviate a bypass that will not last," he said.

Dr. Naoum is also curious about why the grafts fail; two patients needed angioplasty to keep their grafts open, and thrombectomy was performed in one.

Cryopreservation makes cells thicker, perhaps causing intimal tears and scarring. Poor runoff is also a problem. If distal vessels can’t handle the new blood flow, pressure builds up in the graft, leading to clots and other problems, he said.

Dr. Naoum said that he was a consultant for CryoLife Inc., a major supplier of arterial homografts, in 2009, but is no longer involved with the company. He said he received no discounts on the grafts used in the case series.

FROM THE ANNUAL ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Cadaver Artery Grafts May Help Save Limbs

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.

The findings add weight to the small body of literature showing that homografts can help in such cases.

The patients’ average age was 71 years, and five were men. Comorbidities included peripheral vascular disease (12 patients), diabetes (7), foot infections or gangrene (10), foot ischemia but no wound (2), and an infected Gore-Tex graft (1).

Dr. Naoum said he chose arterial homografts instead of vein homografts to cut down potential graft complications; arteries have more uniform diameters and no valves.

Four patients got femoral below-the-knee popliteal grafts; four had femoral- to anterior-tibial-artery grafts; and three had femoral- to posterior-tibial-artery grafts. Two patients received femoral- to peroneal-artery grafts.

Only patients who could tolerate the surgery, which is a longer and more complicated procedure than leg amputation, and who were currently ambulatory underwent the procedure.

"There is no point using these homografts to preserve limbs if patients are not walking," Dr Naoum noted.

The grafts cost about $3,000 and range in length from about 25 to 35 cm, depending on the donor.

"We like to ask for the longest piece possible," to avoid splicing. "However, we get what is available based on the diameter requested and blood-type match," Dr. Naoum said.

Once thawed per supplier directions, the homografts handle like any other graft tissue. Suturing is standard.

Dr. Naoum said he and some of his colleagues like to tunnel the grafts under subcutaneous fat instead of anatomically, to minimize compression. They also prefer to arterialize the graft before making the distal anastomoses to elongate the graft for better sizing and to work out any kinks, he said.

Patients were told to stop smoking after their operations (five of them smoked), and they were put on aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), and a statin, if they were not on one already. There’s no evidence that antirejection drugs are needed, Dr. Naoum said.

Two patients later needed toe amputations, and four required transmetatarsal amputations.

The 18-month patency rate was less than the perhaps 75% patency rate that would be expected had they been grafted with their own veins. Even so, the restored blood flow "was enough to allow the wounds to heal," Dr. Naoum said.

He said he plans to continue studying the use of arterial homografts to better define factors associated with good outcomes.

"What is needed is a greater experience to identify patients who will benefit most from such procedures, and those in whom an amputation may obviate a bypass that will not last," he said.

Dr. Naoum is also curious about why the grafts fail; two patients needed angioplasty to keep their grafts open, and thrombectomy was performed in one.

Cryopreservation makes cells thicker, perhaps causing intimal tears and scarring. Poor runoff is also a problem. If distal vessels can’t handle the new blood flow, pressure builds up in the graft, leading to clots and other problems, he said.

Dr. Naoum said that he was a consultant for CryoLife Inc., a major supplier of arterial homografts, in 2009, but is no longer involved with the company. He said he received no discounts on the grafts used in the case series.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.

The findings add weight to the small body of literature showing that homografts can help in such cases.

The patients’ average age was 71 years, and five were men. Comorbidities included peripheral vascular disease (12 patients), diabetes (7), foot infections or gangrene (10), foot ischemia but no wound (2), and an infected Gore-Tex graft (1).

Dr. Naoum said he chose arterial homografts instead of vein homografts to cut down potential graft complications; arteries have more uniform diameters and no valves.

Four patients got femoral below-the-knee popliteal grafts; four had femoral- to anterior-tibial-artery grafts; and three had femoral- to posterior-tibial-artery grafts. Two patients received femoral- to peroneal-artery grafts.

Only patients who could tolerate the surgery, which is a longer and more complicated procedure than leg amputation, and who were currently ambulatory underwent the procedure.

"There is no point using these homografts to preserve limbs if patients are not walking," Dr Naoum noted.

The grafts cost about $3,000 and range in length from about 25 to 35 cm, depending on the donor.

"We like to ask for the longest piece possible," to avoid splicing. "However, we get what is available based on the diameter requested and blood-type match," Dr. Naoum said.

Once thawed per supplier directions, the homografts handle like any other graft tissue. Suturing is standard.

Dr. Naoum said he and some of his colleagues like to tunnel the grafts under subcutaneous fat instead of anatomically, to minimize compression. They also prefer to arterialize the graft before making the distal anastomoses to elongate the graft for better sizing and to work out any kinks, he said.

Patients were told to stop smoking after their operations (five of them smoked), and they were put on aspirin, Plavix (clopidogrel), and a statin, if they were not on one already. There’s no evidence that antirejection drugs are needed, Dr. Naoum said.

Two patients later needed toe amputations, and four required transmetatarsal amputations.

The 18-month patency rate was less than the perhaps 75% patency rate that would be expected had they been grafted with their own veins. Even so, the restored blood flow "was enough to allow the wounds to heal," Dr. Naoum said.

He said he plans to continue studying the use of arterial homografts to better define factors associated with good outcomes.

"What is needed is a greater experience to identify patients who will benefit most from such procedures, and those in whom an amputation may obviate a bypass that will not last," he said.

Dr. Naoum is also curious about why the grafts fail; two patients needed angioplasty to keep their grafts open, and thrombectomy was performed in one.

Cryopreservation makes cells thicker, perhaps causing intimal tears and scarring. Poor runoff is also a problem. If distal vessels can’t handle the new blood flow, pressure builds up in the graft, leading to clots and other problems, he said.

Dr. Naoum said that he was a consultant for CryoLife Inc., a major supplier of arterial homografts, in 2009, but is no longer involved with the company. He said he received no discounts on the grafts used in the case series.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Cryopreserved arterial homografts show promise for reperfusion in patients with severe vascular disease whose only other option may be a below- or above-the-knee amputation, results of a retrospective case series suggested.

Dr. Joseph Naoum and his colleagues in the division of vascular surgery at Methodist Hospital in Houston successfully used cryopreserved arterial homografts–arteries harvested from cadavers and frozen–to reperfuse feet in 13 such patients.

After 18 months, the cumulative patency rate was 58.6%, Dr. Naoum said at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

"If we had not used arterial homografts, [these patients] would have certainly required below-the-knee or above-the-knee amputations," Dr. Naoum said in an interview.