User login

Welcome to three new Editorial Advisory Board members!

We are pleased to welcome Dr. Joseph B. Domachowske, Dr. Howard Smart, and Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. to the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He serves on the New York State American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 1 executive committee, volunteers as his district’s immunization champion, and is an appointed member of the New York State Immunization Advisory Council. He also enjoys his work as an AAP PREP-ID editorial board member. His overlapping clinical and research interests include immunization advocacy and studies related to the treatment and prevention of viral respiratory tract infections, particularly respiratory syncytial virus. He has published more than 120 papers and book chapters in these areas. Dr. Domachowske has had the privilege of presenting on his global vaccine advocacy efforts with funding through AAP’s Shot@Life program.

Dr. Rushton Jr. is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (QTIP) network. He has practiced pediatrics in Beaufort, S.C., for 32 years and is the author of “Family Support in Community Pediatrics, Confronting the Challenge. “Dr. Rushton’s academic interests include quality improvement, community pediatrics, early brain development, home visitation, and group well child care.

Dr. Smart practices general pediatrics and adolescent medicine as a member of the Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. He is a voluntary assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and is currently chief of pediatrics at Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women & Newborns. Dr. Smart’s interests include medical informatics, health care IT, and specifically clinical decision support and the use of data to drive clinical quality improvement.

We are pleased to welcome Dr. Joseph B. Domachowske, Dr. Howard Smart, and Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. to the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He serves on the New York State American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 1 executive committee, volunteers as his district’s immunization champion, and is an appointed member of the New York State Immunization Advisory Council. He also enjoys his work as an AAP PREP-ID editorial board member. His overlapping clinical and research interests include immunization advocacy and studies related to the treatment and prevention of viral respiratory tract infections, particularly respiratory syncytial virus. He has published more than 120 papers and book chapters in these areas. Dr. Domachowske has had the privilege of presenting on his global vaccine advocacy efforts with funding through AAP’s Shot@Life program.

Dr. Rushton Jr. is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (QTIP) network. He has practiced pediatrics in Beaufort, S.C., for 32 years and is the author of “Family Support in Community Pediatrics, Confronting the Challenge. “Dr. Rushton’s academic interests include quality improvement, community pediatrics, early brain development, home visitation, and group well child care.

Dr. Smart practices general pediatrics and adolescent medicine as a member of the Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. He is a voluntary assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and is currently chief of pediatrics at Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women & Newborns. Dr. Smart’s interests include medical informatics, health care IT, and specifically clinical decision support and the use of data to drive clinical quality improvement.

We are pleased to welcome Dr. Joseph B. Domachowske, Dr. Howard Smart, and Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. to the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He serves on the New York State American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 1 executive committee, volunteers as his district’s immunization champion, and is an appointed member of the New York State Immunization Advisory Council. He also enjoys his work as an AAP PREP-ID editorial board member. His overlapping clinical and research interests include immunization advocacy and studies related to the treatment and prevention of viral respiratory tract infections, particularly respiratory syncytial virus. He has published more than 120 papers and book chapters in these areas. Dr. Domachowske has had the privilege of presenting on his global vaccine advocacy efforts with funding through AAP’s Shot@Life program.

Dr. Rushton Jr. is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics (QTIP) network. He has practiced pediatrics in Beaufort, S.C., for 32 years and is the author of “Family Support in Community Pediatrics, Confronting the Challenge. “Dr. Rushton’s academic interests include quality improvement, community pediatrics, early brain development, home visitation, and group well child care.

Dr. Smart practices general pediatrics and adolescent medicine as a member of the Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. He is a voluntary assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and is currently chief of pediatrics at Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women & Newborns. Dr. Smart’s interests include medical informatics, health care IT, and specifically clinical decision support and the use of data to drive clinical quality improvement.

Survey: ObGyns’ salaries rose slightly in 2013

The 2014 Medscape Compensation Report surveyed more than 24,000 physicians in 25 specialties. Five percent of respondents were ObGyns, whose mean income rose slightly to $243,000 in 2013 from $242,000 in 2012, up from $220,000 in 2011.1–3 The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Great Lakes and North Central regions.1

Survey findings

Men make more than women. In 2013, male ObGyns reported earning $256,000; female ObGyns reported $229,000 in mean income. However, women felt more satisfied with their salary (47% of women vs 38% of men). Regardless of gender, ObGyns were slightly less happy with their income than all physicians (50% satisfied).1

Among all female physicians, more were employed than self-employed; the opposite was true for male physicians.4 Half of all graduating physicians are now female, and demographics show that 62% of all female physicians are younger than age 45.1

Practice settings are key to income. Sixty percent of ObGyns indicated they would choose medicine again as a career; 43% would choose their own specialty. However, only 25% of ObGyns would make the same decision about practice setting.1

In 2013, employed and self-employed ObGyns reported nearly the same mean income: $243,000 versus $246,000, respectively. However, when broken down by specific practice setting, the highest earners were ObGyns who worked for health-care organizations, at $273,000. Additional 2013 mean earnings ranked by work setting were1:

- multispecialty office-based group practices, $271,000

- single-specialty office-based group practices, $255,000

- hospitals, $228,000

- solo office-based practices, $212,000

- outpatient clinics, $207,000.

In 2013, 49% of employed physicians worked in hospitals or in groups owned by a hospital, while 21% were employed by private groups. Other employment situations included community health centers, corporate laboratories, correction institutions, military bases, and nursing homes.4

ACO participation grows. In 2013, 37% of ObGyns either participated in an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) or planned on joining an ACO within the next year.1 This was an increase from 25% in 2012.2,3

In the most recent report, 2% chose concierge practices (also known as direct primary care) and 5% opted for cash-only practices.1 In 2012, only 1% of ObGyns opted for concierge practices, and 3% for cash-only practices.2,3

Related article: Is private ObGyn practice on its way out? Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

Employment over private practice? In 2013, physicians were enticed to seek employment by the financial challenges of private practice (38%); not having to be concerned about administrative issues (29%); and working shorter and more regular hours (19%). Other reported benefits of employment were academic opportunities, better life−work balance, more vacation time, and no loss of income during vacation. More than half (53%) of employed physicians who were previously self-employed felt that patient care was superior now that they were employed, and 37% thought it was about the same.4

Related article: Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. Deborah Reale (News for your Practice; August 2013)

Career satisfaction

ObGyns were close to the bottom among all physicians (48%) when it came to overall career satisfaction, tied with nephrologists, surgeons, and pulmonologists. The most satisfied physicians were dermatologists (65%); the least satisfied were plastic surgeons (45%).1

What drives you? In 2013, more ObGyns (41%) than all physicians (33%) reported that the most rewarding part of their job was their relationships with patients. Thirty percent of ObGyns chose being good at their jobs; 8% chose making good money; and 2% found nothing rewarding about the job.1

How much patient time do you spend? The majority (58%) of ObGyns reported spending more than 40 hours per week with patients and 16 minutes or less (66%) per patient.1 In 2012, 60% of ObGyn respondents reported spending 16 minutes or less per patient.2,3

Anticipating the effects of the Affordable Care Act

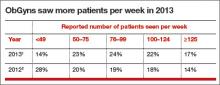

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), an organization’s revenue will still be determined largely by the volume generated by physicians. The percentage of ObGyns who saw 50 to 124 patients per week increased from 57% in 2012 to 69% in 2013 (TABLE).1,2

In 2013, 53% of ObGyns still were undecided about health-insurance exchange participation—the same percentage as all survey respondents. Among ObGyns, 30% would participate, and 17% would not participate.1

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines. Lucia DiVenere, MA (Practice Management; January 2014)

Almost half (49%) of ObGyns expect their income under the ACA to decrease. About 45% of ObGyns did not foresee any change, and 5% believed their incomes would increase (1% didn’t know) under the ACA. ObGyns also anticipated a higher workload, a decline in quality of patient care and access, and reduced ability to make decisions.1

Almost one-third of ObGyns dropped poorly paying insurers. In 2013, 29% of ObGyns said they regularly drop insurers who pay poorly, but 46% said they keep their insurers year after year. In 2012, 26% of ObGyns said they drop insurers who pay the least or create the most trouble; 29% said they keep all insurers.2,3 Private insurance paid for 63% of patient visits to ObGyns in 2013.1

Fewer ObGyns indicated they would see Medicare and Medicaid patients. In 2013, 20% of self-employed and 5% of employed ObGyns said that they plan to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients. More employed (72%) than self-employed (46%) ObGyns reported that they would continue seeing new and current Medicare and Medicaid patients.1

Related article: Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; October 2011)

In 2012, 15% of ObGyn respondents planned to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients, but 53% of ObGyn respondents said they would continue to see current patients and would take on new Medicare or Medicaid patients.2,3

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- Peckham C. Medscape OB/GYN Compensation Report 2014. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Medscape News. Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2013. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2013/womenshealth. Accessed June 30, 2013.

- Reale D. Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):34–36.

- Kane L. Employed vs self-employed: Who is better off? Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/employed-doctors. Published March 11, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

The 2014 Medscape Compensation Report surveyed more than 24,000 physicians in 25 specialties. Five percent of respondents were ObGyns, whose mean income rose slightly to $243,000 in 2013 from $242,000 in 2012, up from $220,000 in 2011.1–3 The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Great Lakes and North Central regions.1

Survey findings

Men make more than women. In 2013, male ObGyns reported earning $256,000; female ObGyns reported $229,000 in mean income. However, women felt more satisfied with their salary (47% of women vs 38% of men). Regardless of gender, ObGyns were slightly less happy with their income than all physicians (50% satisfied).1

Among all female physicians, more were employed than self-employed; the opposite was true for male physicians.4 Half of all graduating physicians are now female, and demographics show that 62% of all female physicians are younger than age 45.1

Practice settings are key to income. Sixty percent of ObGyns indicated they would choose medicine again as a career; 43% would choose their own specialty. However, only 25% of ObGyns would make the same decision about practice setting.1

In 2013, employed and self-employed ObGyns reported nearly the same mean income: $243,000 versus $246,000, respectively. However, when broken down by specific practice setting, the highest earners were ObGyns who worked for health-care organizations, at $273,000. Additional 2013 mean earnings ranked by work setting were1:

- multispecialty office-based group practices, $271,000

- single-specialty office-based group practices, $255,000

- hospitals, $228,000

- solo office-based practices, $212,000

- outpatient clinics, $207,000.

In 2013, 49% of employed physicians worked in hospitals or in groups owned by a hospital, while 21% were employed by private groups. Other employment situations included community health centers, corporate laboratories, correction institutions, military bases, and nursing homes.4

ACO participation grows. In 2013, 37% of ObGyns either participated in an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) or planned on joining an ACO within the next year.1 This was an increase from 25% in 2012.2,3

In the most recent report, 2% chose concierge practices (also known as direct primary care) and 5% opted for cash-only practices.1 In 2012, only 1% of ObGyns opted for concierge practices, and 3% for cash-only practices.2,3

Related article: Is private ObGyn practice on its way out? Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

Employment over private practice? In 2013, physicians were enticed to seek employment by the financial challenges of private practice (38%); not having to be concerned about administrative issues (29%); and working shorter and more regular hours (19%). Other reported benefits of employment were academic opportunities, better life−work balance, more vacation time, and no loss of income during vacation. More than half (53%) of employed physicians who were previously self-employed felt that patient care was superior now that they were employed, and 37% thought it was about the same.4

Related article: Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. Deborah Reale (News for your Practice; August 2013)

Career satisfaction

ObGyns were close to the bottom among all physicians (48%) when it came to overall career satisfaction, tied with nephrologists, surgeons, and pulmonologists. The most satisfied physicians were dermatologists (65%); the least satisfied were plastic surgeons (45%).1

What drives you? In 2013, more ObGyns (41%) than all physicians (33%) reported that the most rewarding part of their job was their relationships with patients. Thirty percent of ObGyns chose being good at their jobs; 8% chose making good money; and 2% found nothing rewarding about the job.1

How much patient time do you spend? The majority (58%) of ObGyns reported spending more than 40 hours per week with patients and 16 minutes or less (66%) per patient.1 In 2012, 60% of ObGyn respondents reported spending 16 minutes or less per patient.2,3

Anticipating the effects of the Affordable Care Act

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), an organization’s revenue will still be determined largely by the volume generated by physicians. The percentage of ObGyns who saw 50 to 124 patients per week increased from 57% in 2012 to 69% in 2013 (TABLE).1,2

In 2013, 53% of ObGyns still were undecided about health-insurance exchange participation—the same percentage as all survey respondents. Among ObGyns, 30% would participate, and 17% would not participate.1

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines. Lucia DiVenere, MA (Practice Management; January 2014)

Almost half (49%) of ObGyns expect their income under the ACA to decrease. About 45% of ObGyns did not foresee any change, and 5% believed their incomes would increase (1% didn’t know) under the ACA. ObGyns also anticipated a higher workload, a decline in quality of patient care and access, and reduced ability to make decisions.1

Almost one-third of ObGyns dropped poorly paying insurers. In 2013, 29% of ObGyns said they regularly drop insurers who pay poorly, but 46% said they keep their insurers year after year. In 2012, 26% of ObGyns said they drop insurers who pay the least or create the most trouble; 29% said they keep all insurers.2,3 Private insurance paid for 63% of patient visits to ObGyns in 2013.1

Fewer ObGyns indicated they would see Medicare and Medicaid patients. In 2013, 20% of self-employed and 5% of employed ObGyns said that they plan to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients. More employed (72%) than self-employed (46%) ObGyns reported that they would continue seeing new and current Medicare and Medicaid patients.1

Related article: Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; October 2011)

In 2012, 15% of ObGyn respondents planned to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients, but 53% of ObGyn respondents said they would continue to see current patients and would take on new Medicare or Medicaid patients.2,3

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

The 2014 Medscape Compensation Report surveyed more than 24,000 physicians in 25 specialties. Five percent of respondents were ObGyns, whose mean income rose slightly to $243,000 in 2013 from $242,000 in 2012, up from $220,000 in 2011.1–3 The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Great Lakes and North Central regions.1

Survey findings

Men make more than women. In 2013, male ObGyns reported earning $256,000; female ObGyns reported $229,000 in mean income. However, women felt more satisfied with their salary (47% of women vs 38% of men). Regardless of gender, ObGyns were slightly less happy with their income than all physicians (50% satisfied).1

Among all female physicians, more were employed than self-employed; the opposite was true for male physicians.4 Half of all graduating physicians are now female, and demographics show that 62% of all female physicians are younger than age 45.1

Practice settings are key to income. Sixty percent of ObGyns indicated they would choose medicine again as a career; 43% would choose their own specialty. However, only 25% of ObGyns would make the same decision about practice setting.1

In 2013, employed and self-employed ObGyns reported nearly the same mean income: $243,000 versus $246,000, respectively. However, when broken down by specific practice setting, the highest earners were ObGyns who worked for health-care organizations, at $273,000. Additional 2013 mean earnings ranked by work setting were1:

- multispecialty office-based group practices, $271,000

- single-specialty office-based group practices, $255,000

- hospitals, $228,000

- solo office-based practices, $212,000

- outpatient clinics, $207,000.

In 2013, 49% of employed physicians worked in hospitals or in groups owned by a hospital, while 21% were employed by private groups. Other employment situations included community health centers, corporate laboratories, correction institutions, military bases, and nursing homes.4

ACO participation grows. In 2013, 37% of ObGyns either participated in an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) or planned on joining an ACO within the next year.1 This was an increase from 25% in 2012.2,3

In the most recent report, 2% chose concierge practices (also known as direct primary care) and 5% opted for cash-only practices.1 In 2012, only 1% of ObGyns opted for concierge practices, and 3% for cash-only practices.2,3

Related article: Is private ObGyn practice on its way out? Lucia DiVenere, MA (October 2011)

Employment over private practice? In 2013, physicians were enticed to seek employment by the financial challenges of private practice (38%); not having to be concerned about administrative issues (29%); and working shorter and more regular hours (19%). Other reported benefits of employment were academic opportunities, better life−work balance, more vacation time, and no loss of income during vacation. More than half (53%) of employed physicians who were previously self-employed felt that patient care was superior now that they were employed, and 37% thought it was about the same.4

Related article: Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. Deborah Reale (News for your Practice; August 2013)

Career satisfaction

ObGyns were close to the bottom among all physicians (48%) when it came to overall career satisfaction, tied with nephrologists, surgeons, and pulmonologists. The most satisfied physicians were dermatologists (65%); the least satisfied were plastic surgeons (45%).1

What drives you? In 2013, more ObGyns (41%) than all physicians (33%) reported that the most rewarding part of their job was their relationships with patients. Thirty percent of ObGyns chose being good at their jobs; 8% chose making good money; and 2% found nothing rewarding about the job.1

How much patient time do you spend? The majority (58%) of ObGyns reported spending more than 40 hours per week with patients and 16 minutes or less (66%) per patient.1 In 2012, 60% of ObGyn respondents reported spending 16 minutes or less per patient.2,3

Anticipating the effects of the Affordable Care Act

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), an organization’s revenue will still be determined largely by the volume generated by physicians. The percentage of ObGyns who saw 50 to 124 patients per week increased from 57% in 2012 to 69% in 2013 (TABLE).1,2

In 2013, 53% of ObGyns still were undecided about health-insurance exchange participation—the same percentage as all survey respondents. Among ObGyns, 30% would participate, and 17% would not participate.1

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines. Lucia DiVenere, MA (Practice Management; January 2014)

Almost half (49%) of ObGyns expect their income under the ACA to decrease. About 45% of ObGyns did not foresee any change, and 5% believed their incomes would increase (1% didn’t know) under the ACA. ObGyns also anticipated a higher workload, a decline in quality of patient care and access, and reduced ability to make decisions.1

Almost one-third of ObGyns dropped poorly paying insurers. In 2013, 29% of ObGyns said they regularly drop insurers who pay poorly, but 46% said they keep their insurers year after year. In 2012, 26% of ObGyns said they drop insurers who pay the least or create the most trouble; 29% said they keep all insurers.2,3 Private insurance paid for 63% of patient visits to ObGyns in 2013.1

Fewer ObGyns indicated they would see Medicare and Medicaid patients. In 2013, 20% of self-employed and 5% of employed ObGyns said that they plan to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients. More employed (72%) than self-employed (46%) ObGyns reported that they would continue seeing new and current Medicare and Medicaid patients.1

Related article: Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander. Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; October 2011)

In 2012, 15% of ObGyn respondents planned to stop taking new Medicare or Medicaid patients, but 53% of ObGyn respondents said they would continue to see current patients and would take on new Medicare or Medicaid patients.2,3

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- Peckham C. Medscape OB/GYN Compensation Report 2014. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Medscape News. Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2013. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2013/womenshealth. Accessed June 30, 2013.

- Reale D. Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):34–36.

- Kane L. Employed vs self-employed: Who is better off? Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/employed-doctors. Published March 11, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Peckham C. Medscape OB/GYN Compensation Report 2014. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Medscape News. Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2013. Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2013/womenshealth. Accessed June 30, 2013.

- Reale D. Mean income for ObGyns increased in 2012. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):34–36.

- Kane L. Employed vs self-employed: Who is better off? Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/employed-doctors. Published March 11, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2014.

FDA Advisory Committee recommends HPV test as primary screening tool for cervical cancer

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Microbiology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee has unanimously recommended that the cobas HPV (human papillomavirus) test be used as a first-line primary screening tool in women aged 25 years and older to assess their risk of cervical cancer based on the presence of clinically relevant high-risk HPV DNA. The committee’s recommendation indicates that the benefits outweigh the risks of the test, and that the cobas HPV test is safe and effective for the proposed indication for use.1

If approved by the FDA, the cobas HPV test would become the “first and only HPV test indicated as the first-line primary screen of cervical cancer in the United States.”2 Although the FDA is not required to follow the Advisory Committee’s recommendation, it takes the advice into consideration.

Data behind the recommendation

The Advisory Committee’s recommendation is supported by data from the ATHENA study, which included more than 47,000 women – the largest US-based registration study for cervical cancer screening. Data show that when the cobas HPV test was used as the primary test and Pap cytology as a secondary test, significantly more cervical disease was detected compared with Pap screening alone.2

“Through technological and scientific advancement, we now have a better screening tool for cervical cancer. Women around the world deserve the best tool to know their risk and reduce their chances of developing cervical cancer,” said Roland Diggelmann, COO for the Division of Roche Diagnostics, the company who developed and manufactures the test. “We look forward to working with the FDA and medical community to support the growing understanding and awareness of the role that HPV plays in cervical disease, and the importance of the cobas HPV test, which provides the necessary medical benefit to become the first-line test in a cervical cancer screening strategy.”2

How could current practice change as a result of final FDA approval?

The cobas HPV test is currently FDA-approved for co-testing with the Pap smear in women older than age 30 for cervical cancer screening, and for screening patients aged 21 and older with abnormal cervical cytology results.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, MS, chair of the cervical cancer education efforts of the Foundation for Women’s Cancer and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein Cancer Center and Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, says final approval of this testing as a primary screening tool represents significant changes to clinical practice. However, “similar to what happened when co-testing [with the cobas HPV test] was approved, it took time for scientific stakeholding groups to update clinical guidelines, then years before clinicians adopted it into routine practice.”

“Unlike a new prescription, clinical algorithms tend to be 'hard-wired' into clinicians heads, and adopting significant change is a process,” Einstein says. “It’s likely that a new cervical cancer screening testing clinical algorithm would be adopted by some clinicians early and by many clinicians over time.” He added that the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology have an interim clinical guidance document currently drafted, and those guidelines will be released soon after any decisions by the FDA.

When that time comes (assuming final FDA approval is received), Einstein says, “some clinical settings will be able to start with the more sensitive HPV test. For some patients, this will be followed by genotyping or cytology. This has been shown to be an effective strategy for honing in on the most at-risk women in a screening population.”

- FDA Executive Summary: March 12, 2014. 2014 Meeting Materials of the Microbiology Devices Panel. FDA Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/MicrobiologyDevicesPanel/UCM388564.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- FDA Advisory Committee unanimously recommends Roche's HPV Test as primary screening tool for detection of women at high risk for cervical cancer [media release]. http://www.roche.com/media/media_releases/med-cor-2014-03-13.htm. Published March 13, 2014. Accessed March 14, 2014.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Microbiology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee has unanimously recommended that the cobas HPV (human papillomavirus) test be used as a first-line primary screening tool in women aged 25 years and older to assess their risk of cervical cancer based on the presence of clinically relevant high-risk HPV DNA. The committee’s recommendation indicates that the benefits outweigh the risks of the test, and that the cobas HPV test is safe and effective for the proposed indication for use.1

If approved by the FDA, the cobas HPV test would become the “first and only HPV test indicated as the first-line primary screen of cervical cancer in the United States.”2 Although the FDA is not required to follow the Advisory Committee’s recommendation, it takes the advice into consideration.

Data behind the recommendation

The Advisory Committee’s recommendation is supported by data from the ATHENA study, which included more than 47,000 women – the largest US-based registration study for cervical cancer screening. Data show that when the cobas HPV test was used as the primary test and Pap cytology as a secondary test, significantly more cervical disease was detected compared with Pap screening alone.2

“Through technological and scientific advancement, we now have a better screening tool for cervical cancer. Women around the world deserve the best tool to know their risk and reduce their chances of developing cervical cancer,” said Roland Diggelmann, COO for the Division of Roche Diagnostics, the company who developed and manufactures the test. “We look forward to working with the FDA and medical community to support the growing understanding and awareness of the role that HPV plays in cervical disease, and the importance of the cobas HPV test, which provides the necessary medical benefit to become the first-line test in a cervical cancer screening strategy.”2

How could current practice change as a result of final FDA approval?

The cobas HPV test is currently FDA-approved for co-testing with the Pap smear in women older than age 30 for cervical cancer screening, and for screening patients aged 21 and older with abnormal cervical cytology results.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, MS, chair of the cervical cancer education efforts of the Foundation for Women’s Cancer and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein Cancer Center and Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, says final approval of this testing as a primary screening tool represents significant changes to clinical practice. However, “similar to what happened when co-testing [with the cobas HPV test] was approved, it took time for scientific stakeholding groups to update clinical guidelines, then years before clinicians adopted it into routine practice.”

“Unlike a new prescription, clinical algorithms tend to be 'hard-wired' into clinicians heads, and adopting significant change is a process,” Einstein says. “It’s likely that a new cervical cancer screening testing clinical algorithm would be adopted by some clinicians early and by many clinicians over time.” He added that the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology have an interim clinical guidance document currently drafted, and those guidelines will be released soon after any decisions by the FDA.

When that time comes (assuming final FDA approval is received), Einstein says, “some clinical settings will be able to start with the more sensitive HPV test. For some patients, this will be followed by genotyping or cytology. This has been shown to be an effective strategy for honing in on the most at-risk women in a screening population.”

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Microbiology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee has unanimously recommended that the cobas HPV (human papillomavirus) test be used as a first-line primary screening tool in women aged 25 years and older to assess their risk of cervical cancer based on the presence of clinically relevant high-risk HPV DNA. The committee’s recommendation indicates that the benefits outweigh the risks of the test, and that the cobas HPV test is safe and effective for the proposed indication for use.1

If approved by the FDA, the cobas HPV test would become the “first and only HPV test indicated as the first-line primary screen of cervical cancer in the United States.”2 Although the FDA is not required to follow the Advisory Committee’s recommendation, it takes the advice into consideration.

Data behind the recommendation

The Advisory Committee’s recommendation is supported by data from the ATHENA study, which included more than 47,000 women – the largest US-based registration study for cervical cancer screening. Data show that when the cobas HPV test was used as the primary test and Pap cytology as a secondary test, significantly more cervical disease was detected compared with Pap screening alone.2

“Through technological and scientific advancement, we now have a better screening tool for cervical cancer. Women around the world deserve the best tool to know their risk and reduce their chances of developing cervical cancer,” said Roland Diggelmann, COO for the Division of Roche Diagnostics, the company who developed and manufactures the test. “We look forward to working with the FDA and medical community to support the growing understanding and awareness of the role that HPV plays in cervical disease, and the importance of the cobas HPV test, which provides the necessary medical benefit to become the first-line test in a cervical cancer screening strategy.”2

How could current practice change as a result of final FDA approval?

The cobas HPV test is currently FDA-approved for co-testing with the Pap smear in women older than age 30 for cervical cancer screening, and for screening patients aged 21 and older with abnormal cervical cytology results.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, MS, chair of the cervical cancer education efforts of the Foundation for Women’s Cancer and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein Cancer Center and Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, says final approval of this testing as a primary screening tool represents significant changes to clinical practice. However, “similar to what happened when co-testing [with the cobas HPV test] was approved, it took time for scientific stakeholding groups to update clinical guidelines, then years before clinicians adopted it into routine practice.”

“Unlike a new prescription, clinical algorithms tend to be 'hard-wired' into clinicians heads, and adopting significant change is a process,” Einstein says. “It’s likely that a new cervical cancer screening testing clinical algorithm would be adopted by some clinicians early and by many clinicians over time.” He added that the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology have an interim clinical guidance document currently drafted, and those guidelines will be released soon after any decisions by the FDA.

When that time comes (assuming final FDA approval is received), Einstein says, “some clinical settings will be able to start with the more sensitive HPV test. For some patients, this will be followed by genotyping or cytology. This has been shown to be an effective strategy for honing in on the most at-risk women in a screening population.”

- FDA Executive Summary: March 12, 2014. 2014 Meeting Materials of the Microbiology Devices Panel. FDA Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/MicrobiologyDevicesPanel/UCM388564.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- FDA Advisory Committee unanimously recommends Roche's HPV Test as primary screening tool for detection of women at high risk for cervical cancer [media release]. http://www.roche.com/media/media_releases/med-cor-2014-03-13.htm. Published March 13, 2014. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- FDA Executive Summary: March 12, 2014. 2014 Meeting Materials of the Microbiology Devices Panel. FDA Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/MicrobiologyDevicesPanel/UCM388564.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- FDA Advisory Committee unanimously recommends Roche's HPV Test as primary screening tool for detection of women at high risk for cervical cancer [media release]. http://www.roche.com/media/media_releases/med-cor-2014-03-13.htm. Published March 13, 2014. Accessed March 14, 2014.

Hysterectomy routes and surgical outcomes in obese patients analyzed

In obese women, laparoscopic hysterectomy provided the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss when compared with vaginal hysterectomy, according to a poster presented at the 42nd AAGL Global Congress in Washington, DC, in November 2013.1

Teresa Tam, MD, Gerald Harkins, MD, and researchers at Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, reported on a retrospective cohort study conducted to compare the routes of hysterectomy and surgical outcomes in obese patients.

Of the 1,286 patients who underwent hysterectomy between December 1, 2009, and December 1, 2012, at Hershey Medical Center, 596 met the obese body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria (BMI >30 kg/m2). Mean (SD) BMI was 36.5 (5.8) kg/m2 and the mean (SD) patient age was 45 (10) years. Mean (SD) gravidity was 2.44 (1.85) and mean (SD) parity was 1.97 (1.41).

Reasons for surgery were restricted to benign indications, including leiomyoma (31%); abnormal uterine bleeding (29%); and endometriosis (17%).

The following approaches to hysterectomy were included:

- abdominal hysterectomy [total abdominal and supracervical] (AH; n = 7)

- vaginal hysterectomy (VH; n = 84)

- laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH; n = 16)

- total laparoscopic hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (TLH; n = 295)

- laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (LSH; n = 194).

Comparisons to AH were not considered in the results (n = 7). Less than 1% of the hysterectomies were abdominal cases, with majority (5 out of 7 AHs) performed being combined cases, in conjunction with colorectal service for colon or rectal malignancies. Data on preoperative indications, estimated blood loss, operating time, length of stay, and postoperative complications were compared.

The largest differences in median (SD) operating time were between TLH and LAVH (80 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001) and LSH and LAVH (90 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001).

The only statistically significant difference with regard to patients’ median (SD) length of stay was between TLH and VH (1.07 days vs 1.12 days, respectively; P = .005), but the researchers did not consider a difference of 0.05 days (1.2 hours) to be clinically relevant.

The odds of estimated blood loss of 200 mL or greater were significantly higher with VH than with TLH (35.0% vs 3.4%, respectively; odds ratio [OR] = 15.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.0–33.4; P <.001). The odds of estimated blood loss also were significantly higher with VH than with LSH (35.0% vs. 8.4%; OR = 5.9; 95% CI, 3.0–11.7; P <.001).

No association was found between high BMI and surgical complications, the authors reported. However, due to the study’s retrospective nature, Tam and Harkins note that surgeon selection bias on the route of hysterectomy could be based on concerns with operative access and outcomes in obese patients. The authors concur that more studies need to be performed comparing robotic with conventional laparoscopic routes of hysterectomy in the obese.

“In this study, laparoscopic hysterectomy offered the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss compared to the vaginal route in the obese patient population,” the authors concluded.

They noted, however, that, “Although performing hysterectomy in obese patients can be challenging, this study reaffirms that a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy is both safe and effective. Providing either a vaginal or laparoscopic modality to hysterectomy is often requested by patients, and is supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the AAGL.”

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: [email protected]

Reference

Tam T, Gupta M, Alligood-Percoco N, de los Reyes S, Davies M, Harkins G. Comparison of routes of hysterectomy and their surgical outcomes in obese patients. Poster presented at: 42nd AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Surgery; November 10–14, 2013; Washington, DC.

In obese women, laparoscopic hysterectomy provided the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss when compared with vaginal hysterectomy, according to a poster presented at the 42nd AAGL Global Congress in Washington, DC, in November 2013.1

Teresa Tam, MD, Gerald Harkins, MD, and researchers at Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, reported on a retrospective cohort study conducted to compare the routes of hysterectomy and surgical outcomes in obese patients.

Of the 1,286 patients who underwent hysterectomy between December 1, 2009, and December 1, 2012, at Hershey Medical Center, 596 met the obese body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria (BMI >30 kg/m2). Mean (SD) BMI was 36.5 (5.8) kg/m2 and the mean (SD) patient age was 45 (10) years. Mean (SD) gravidity was 2.44 (1.85) and mean (SD) parity was 1.97 (1.41).

Reasons for surgery were restricted to benign indications, including leiomyoma (31%); abnormal uterine bleeding (29%); and endometriosis (17%).

The following approaches to hysterectomy were included:

- abdominal hysterectomy [total abdominal and supracervical] (AH; n = 7)

- vaginal hysterectomy (VH; n = 84)

- laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH; n = 16)

- total laparoscopic hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (TLH; n = 295)

- laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (LSH; n = 194).

Comparisons to AH were not considered in the results (n = 7). Less than 1% of the hysterectomies were abdominal cases, with majority (5 out of 7 AHs) performed being combined cases, in conjunction with colorectal service for colon or rectal malignancies. Data on preoperative indications, estimated blood loss, operating time, length of stay, and postoperative complications were compared.

The largest differences in median (SD) operating time were between TLH and LAVH (80 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001) and LSH and LAVH (90 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001).

The only statistically significant difference with regard to patients’ median (SD) length of stay was between TLH and VH (1.07 days vs 1.12 days, respectively; P = .005), but the researchers did not consider a difference of 0.05 days (1.2 hours) to be clinically relevant.

The odds of estimated blood loss of 200 mL or greater were significantly higher with VH than with TLH (35.0% vs 3.4%, respectively; odds ratio [OR] = 15.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.0–33.4; P <.001). The odds of estimated blood loss also were significantly higher with VH than with LSH (35.0% vs. 8.4%; OR = 5.9; 95% CI, 3.0–11.7; P <.001).

No association was found between high BMI and surgical complications, the authors reported. However, due to the study’s retrospective nature, Tam and Harkins note that surgeon selection bias on the route of hysterectomy could be based on concerns with operative access and outcomes in obese patients. The authors concur that more studies need to be performed comparing robotic with conventional laparoscopic routes of hysterectomy in the obese.

“In this study, laparoscopic hysterectomy offered the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss compared to the vaginal route in the obese patient population,” the authors concluded.

They noted, however, that, “Although performing hysterectomy in obese patients can be challenging, this study reaffirms that a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy is both safe and effective. Providing either a vaginal or laparoscopic modality to hysterectomy is often requested by patients, and is supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the AAGL.”

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: [email protected]

In obese women, laparoscopic hysterectomy provided the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss when compared with vaginal hysterectomy, according to a poster presented at the 42nd AAGL Global Congress in Washington, DC, in November 2013.1

Teresa Tam, MD, Gerald Harkins, MD, and researchers at Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, reported on a retrospective cohort study conducted to compare the routes of hysterectomy and surgical outcomes in obese patients.

Of the 1,286 patients who underwent hysterectomy between December 1, 2009, and December 1, 2012, at Hershey Medical Center, 596 met the obese body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria (BMI >30 kg/m2). Mean (SD) BMI was 36.5 (5.8) kg/m2 and the mean (SD) patient age was 45 (10) years. Mean (SD) gravidity was 2.44 (1.85) and mean (SD) parity was 1.97 (1.41).

Reasons for surgery were restricted to benign indications, including leiomyoma (31%); abnormal uterine bleeding (29%); and endometriosis (17%).

The following approaches to hysterectomy were included:

- abdominal hysterectomy [total abdominal and supracervical] (AH; n = 7)

- vaginal hysterectomy (VH; n = 84)

- laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH; n = 16)

- total laparoscopic hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (TLH; n = 295)

- laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy [conventional and robotic] (LSH; n = 194).

Comparisons to AH were not considered in the results (n = 7). Less than 1% of the hysterectomies were abdominal cases, with majority (5 out of 7 AHs) performed being combined cases, in conjunction with colorectal service for colon or rectal malignancies. Data on preoperative indications, estimated blood loss, operating time, length of stay, and postoperative complications were compared.

The largest differences in median (SD) operating time were between TLH and LAVH (80 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001) and LSH and LAVH (90 min vs 137.5 min, respectively; P <.001).

The only statistically significant difference with regard to patients’ median (SD) length of stay was between TLH and VH (1.07 days vs 1.12 days, respectively; P = .005), but the researchers did not consider a difference of 0.05 days (1.2 hours) to be clinically relevant.

The odds of estimated blood loss of 200 mL or greater were significantly higher with VH than with TLH (35.0% vs 3.4%, respectively; odds ratio [OR] = 15.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 7.0–33.4; P <.001). The odds of estimated blood loss also were significantly higher with VH than with LSH (35.0% vs. 8.4%; OR = 5.9; 95% CI, 3.0–11.7; P <.001).

No association was found between high BMI and surgical complications, the authors reported. However, due to the study’s retrospective nature, Tam and Harkins note that surgeon selection bias on the route of hysterectomy could be based on concerns with operative access and outcomes in obese patients. The authors concur that more studies need to be performed comparing robotic with conventional laparoscopic routes of hysterectomy in the obese.

“In this study, laparoscopic hysterectomy offered the shortest operating time with minimal blood loss compared to the vaginal route in the obese patient population,” the authors concluded.

They noted, however, that, “Although performing hysterectomy in obese patients can be challenging, this study reaffirms that a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy is both safe and effective. Providing either a vaginal or laparoscopic modality to hysterectomy is often requested by patients, and is supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the AAGL.”

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: [email protected]

Reference

Tam T, Gupta M, Alligood-Percoco N, de los Reyes S, Davies M, Harkins G. Comparison of routes of hysterectomy and their surgical outcomes in obese patients. Poster presented at: 42nd AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Surgery; November 10–14, 2013; Washington, DC.

Reference

Tam T, Gupta M, Alligood-Percoco N, de los Reyes S, Davies M, Harkins G. Comparison of routes of hysterectomy and their surgical outcomes in obese patients. Poster presented at: 42nd AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Surgery; November 10–14, 2013; Washington, DC.

Gyns can treat men for STDs again, ABOG says

When the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG) announced in September that, with a few exceptions, gynecologists could lose their board certification if they treated men, gynecologists were forced to stop treating male patients. This decision has now been altered, and gynecologists are now allowed to treat male patients for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and to screen men for anal cancer.1

Experts in anal cancer and patient advocacy groups lobbied ABOG to revise their position based on gynecologists’ long-standing tradition of treating men and women for STDs. Anal cancer is usually caused by human papillomavirus. Although rare, the incidence of anal cancer is increasing, especially among those infected with human immunodeficiency virus.1

ABOG’s new statement reads2:

To remain certified by ABOG the care of male patients is prohibited except in the

following circumstances:

- active government service

- evaluation of fertility

- genetic counseling and testing of a couple

- evaluation and management of sexually transmitted infections

- administration of immunizations

- management of transgender conditions

- emergency, pandemic, humanitarian or disaster response care

- family planning services, not to include vasectomy

- newborn circumcision

- completion of ACGME-accredited training and certification in other specialties.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Women’s Health at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, and author of “Update on Cervical Disease” (OBG Management, May 2013), was forced to discontinue seeing male patients. He commented, “Cool heads have prevailed. This is the best decision for our patients.”1

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think!

- Grady D. Gynecologists may treat men, board says in switch. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/27/health/gynecologists-may-treat-men-board-says-in-switch.html?emc=eta1. Published November 26, 2013. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Definition of an ABOG-certified Obstetrician-Gynecologist. ABO+G Web site. http://www.abog.org/definition.asp. Revised 11/26/13. Accessed December 5, 2013.

When the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG) announced in September that, with a few exceptions, gynecologists could lose their board certification if they treated men, gynecologists were forced to stop treating male patients. This decision has now been altered, and gynecologists are now allowed to treat male patients for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and to screen men for anal cancer.1

Experts in anal cancer and patient advocacy groups lobbied ABOG to revise their position based on gynecologists’ long-standing tradition of treating men and women for STDs. Anal cancer is usually caused by human papillomavirus. Although rare, the incidence of anal cancer is increasing, especially among those infected with human immunodeficiency virus.1

ABOG’s new statement reads2:

To remain certified by ABOG the care of male patients is prohibited except in the

following circumstances:

- active government service

- evaluation of fertility

- genetic counseling and testing of a couple

- evaluation and management of sexually transmitted infections

- administration of immunizations

- management of transgender conditions

- emergency, pandemic, humanitarian or disaster response care

- family planning services, not to include vasectomy

- newborn circumcision

- completion of ACGME-accredited training and certification in other specialties.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Women’s Health at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, and author of “Update on Cervical Disease” (OBG Management, May 2013), was forced to discontinue seeing male patients. He commented, “Cool heads have prevailed. This is the best decision for our patients.”1

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think!

When the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG) announced in September that, with a few exceptions, gynecologists could lose their board certification if they treated men, gynecologists were forced to stop treating male patients. This decision has now been altered, and gynecologists are now allowed to treat male patients for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and to screen men for anal cancer.1

Experts in anal cancer and patient advocacy groups lobbied ABOG to revise their position based on gynecologists’ long-standing tradition of treating men and women for STDs. Anal cancer is usually caused by human papillomavirus. Although rare, the incidence of anal cancer is increasing, especially among those infected with human immunodeficiency virus.1

ABOG’s new statement reads2:

To remain certified by ABOG the care of male patients is prohibited except in the

following circumstances:

- active government service

- evaluation of fertility

- genetic counseling and testing of a couple

- evaluation and management of sexually transmitted infections

- administration of immunizations

- management of transgender conditions

- emergency, pandemic, humanitarian or disaster response care

- family planning services, not to include vasectomy

- newborn circumcision

- completion of ACGME-accredited training and certification in other specialties.

Mark H. Einstein, MD, professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Women’s Health at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, and author of “Update on Cervical Disease” (OBG Management, May 2013), was forced to discontinue seeing male patients. He commented, “Cool heads have prevailed. This is the best decision for our patients.”1

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think!

- Grady D. Gynecologists may treat men, board says in switch. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/27/health/gynecologists-may-treat-men-board-says-in-switch.html?emc=eta1. Published November 26, 2013. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Definition of an ABOG-certified Obstetrician-Gynecologist. ABO+G Web site. http://www.abog.org/definition.asp. Revised 11/26/13. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- Grady D. Gynecologists may treat men, board says in switch. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/27/health/gynecologists-may-treat-men-board-says-in-switch.html?emc=eta1. Published November 26, 2013. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Definition of an ABOG-certified Obstetrician-Gynecologist. ABO+G Web site. http://www.abog.org/definition.asp. Revised 11/26/13. Accessed December 5, 2013.

Helping Patients Navigate the Web

How often does this happen to you? You walk into an exam room and ask the patient what brings him in today, and the reply is something like, “Well, doc, I have stomach cancer.” You do a double-take and scan the patient’s chart, looking for test results or notes from a referring provider. Finding nothing, you ask the patient for more information on his diagnosis. To your surprise/dismay/frustration, he says, “Naw, I Googled my symptoms and that’s what I came up with.”

While you can’t control the Web-surfing your patients do before they present, you can influence their information-seeking behavior once you’ve delivered a diagnosis and/or treatment plan. You know they (and their family/caregivers) will have questions about the patient’s condition and how it can be managed for the long term. You hope they’ll come to you for answers. But since they are likely to use the resources at their fingertips, you at least want to ensure the information they receive is accurate and trustworthy.

With that in mind, we asked several Clinician Reviews board members to share the Web sites that they recommend to their patients. Some, including Cathy St. Pierre, PhD, APRN, FNP-BC, FAANP, and Ellen Mandel, DMH, MPA, PA-C, CDE, cited behemoths such as the Mayo Clinic Web site (www.mayoclinic.com/health-information), lauding it for being up to date, easy to access, and “clear and data-driven.” Other board members, as you’ll see below, suggested specialty-specific sites.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PhD, PA, may speak for many clinicians when she explains, “We offer these [resources] to patients and families as part of health education, acknowledging that learning about someone’s condition is the first step to better understanding what they are experiencing and how this may change over time—since most of what we deal with are progressive, lengthy illnesses and chronic disease management.”

If you have reliable Web-based resources that you recommend to your patients, please visit us on Facebook (www.facebook.com/ClinRev) to share them!

Alzheimer’s Disease

ADEAR—Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center

www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers

Who recommends it: Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PA, PhD

Why: Operated by the NIH/National Institute on Aging specifically to provide consumers with current, accurate, state-of-the-art information about Alzheimer’s disease and dementing illness

Also recommended: Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org); Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org); UCSF Memory Center for information on frontotemporal dementia (www.memory.ucsf.edu/ftd); Foundation for Health in Aging (www.healthinaging.org); Kaiser Family Foundation for information about Medicare, Medicaid, and health policy related to aging (www.kff.org)

Cardiology

Cardiac Arrhythmias Research and Education Foundation, Inc (CARE)

www.longqt.org

Who recommends it: Lyle W. Larson, PhD, PA-C

Why: Provides an overview of long QT syndrome (eg, management, genetics); includes links to a study registry for persons with implantable cardioverters-defibrillators who are participating in sports and a complete list of medications to avoid in this patient population. The information is collated and disseminated by health care experts in this field and is updated continuously as new data emerges.

Also recommended: CredibleMeds™ (www.crediblemeds.org)

Dermatology

American Academy of Dermatology: For the Public

www.aad.org/for-the-public

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: Provides patient information about a specific topic or diagnosis that is reliable, up to date, and in understandable language.

eMedicine

http://emedicine.medscape.com

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: The information is current and written by authoritative dermatologists or other relevant specialists. References are copious and relevant, and links in the text guide readers to equally good information on related topics.

Caveats: The only problem with eMedicine is that it’s jargon-heavy and meant only for those who are comfortable with the terminology. I reserve this suggestion for more medically erudite patients (eg, nurses or PAs).

Diabetes

DiabetesMine

www.diabetesmine.com/

Who recommends it: Christine Kessler, RN, MN, CNS, ANP, BC-ADM

Why: This is an award-winning blog by an individual with type 1 diabetes, but it has something for every diabetic patient and his/her family. Really awesome. I recommend it to my patients, and some of them blog for it!

Also recommended: American Diabetes Association (www.diabetes.org/)

Nephrology

American Association of Kidney Patients

www.aakp.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: Their information is written for and by kidney patients. It is for all patients with kidney disease, not just dialysis patients. They offer free publications that emphasize living with kidney disease; these pubs are attractive, with realistic information.

Kidney School

www.kidneyschool.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: This site offers about 16 modules, each on a different topic ranging from dialysis options to sexuality. It is for patients and allows them to pick the topic they want and view the module as often as they wish.

National Kidney Foundation

www.kidney.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: The patient section of this site contains recipes and health information. Patients can register for the Kidney Peers Program, in which they match up either as a mentor or a mentee with another kidney patient in the US. It covers the range from moderate kidney disease to kidney failure and transplant.

Also recommended: DaVita (www.davita.com); Fresenius Medical Care (www.ultracare-dialysis.com)

Orthopedics

OrthoInfo

orthoinfo.aaos.org/

Who recommends it: Mike Rudzinski, RPh, RPA-C

Why: Endorsed by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, this site offers patients information on the most common musculoskeletal conditions. Includes patient education materials with anatomic pictures and discussion. This is my “go to” site for these conditions; it offers an incredible, comprehensive overview of the condition, options for care including potential surgery, and what the patient can do to improve the condition. It is easy to use for the patient—they just click on the anatomic body part involved and a list of conditions comes up.

Rheumatology

American College of Rheumatology

www.rheumatology.org/Practice/Clinical/Patients/Information_for_Patients/

Who recommends it: Rick Pope, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, CPAAPA

Why: Vetted by the American College of Rheumatologists, whose faculty is nationwide, altruistic, and collaborative, it is chock full of resources that are the standard of thinking and care for rheumatic conditions. It includes “scary” diagnoses such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, with short, patient-specific resources that can take the sting out of the perceived notions of these diseases. The information is available in Spanish and English. The Spanish information sheets can be provided to our Hispanic population and European populations that speak primarily Spanish. This is an awesome service for those of us on the East Coast and likely more helpful in parts of the country where Spanish is spoken more commonly.

How often does this happen to you? You walk into an exam room and ask the patient what brings him in today, and the reply is something like, “Well, doc, I have stomach cancer.” You do a double-take and scan the patient’s chart, looking for test results or notes from a referring provider. Finding nothing, you ask the patient for more information on his diagnosis. To your surprise/dismay/frustration, he says, “Naw, I Googled my symptoms and that’s what I came up with.”

While you can’t control the Web-surfing your patients do before they present, you can influence their information-seeking behavior once you’ve delivered a diagnosis and/or treatment plan. You know they (and their family/caregivers) will have questions about the patient’s condition and how it can be managed for the long term. You hope they’ll come to you for answers. But since they are likely to use the resources at their fingertips, you at least want to ensure the information they receive is accurate and trustworthy.

With that in mind, we asked several Clinician Reviews board members to share the Web sites that they recommend to their patients. Some, including Cathy St. Pierre, PhD, APRN, FNP-BC, FAANP, and Ellen Mandel, DMH, MPA, PA-C, CDE, cited behemoths such as the Mayo Clinic Web site (www.mayoclinic.com/health-information), lauding it for being up to date, easy to access, and “clear and data-driven.” Other board members, as you’ll see below, suggested specialty-specific sites.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PhD, PA, may speak for many clinicians when she explains, “We offer these [resources] to patients and families as part of health education, acknowledging that learning about someone’s condition is the first step to better understanding what they are experiencing and how this may change over time—since most of what we deal with are progressive, lengthy illnesses and chronic disease management.”

If you have reliable Web-based resources that you recommend to your patients, please visit us on Facebook (www.facebook.com/ClinRev) to share them!

Alzheimer’s Disease

ADEAR—Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center

www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers

Who recommends it: Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PA, PhD

Why: Operated by the NIH/National Institute on Aging specifically to provide consumers with current, accurate, state-of-the-art information about Alzheimer’s disease and dementing illness

Also recommended: Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org); Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org); UCSF Memory Center for information on frontotemporal dementia (www.memory.ucsf.edu/ftd); Foundation for Health in Aging (www.healthinaging.org); Kaiser Family Foundation for information about Medicare, Medicaid, and health policy related to aging (www.kff.org)

Cardiology

Cardiac Arrhythmias Research and Education Foundation, Inc (CARE)

www.longqt.org

Who recommends it: Lyle W. Larson, PhD, PA-C

Why: Provides an overview of long QT syndrome (eg, management, genetics); includes links to a study registry for persons with implantable cardioverters-defibrillators who are participating in sports and a complete list of medications to avoid in this patient population. The information is collated and disseminated by health care experts in this field and is updated continuously as new data emerges.

Also recommended: CredibleMeds™ (www.crediblemeds.org)

Dermatology

American Academy of Dermatology: For the Public

www.aad.org/for-the-public

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: Provides patient information about a specific topic or diagnosis that is reliable, up to date, and in understandable language.

eMedicine

http://emedicine.medscape.com

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: The information is current and written by authoritative dermatologists or other relevant specialists. References are copious and relevant, and links in the text guide readers to equally good information on related topics.

Caveats: The only problem with eMedicine is that it’s jargon-heavy and meant only for those who are comfortable with the terminology. I reserve this suggestion for more medically erudite patients (eg, nurses or PAs).

Diabetes

DiabetesMine

www.diabetesmine.com/

Who recommends it: Christine Kessler, RN, MN, CNS, ANP, BC-ADM

Why: This is an award-winning blog by an individual with type 1 diabetes, but it has something for every diabetic patient and his/her family. Really awesome. I recommend it to my patients, and some of them blog for it!

Also recommended: American Diabetes Association (www.diabetes.org/)

Nephrology

American Association of Kidney Patients

www.aakp.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: Their information is written for and by kidney patients. It is for all patients with kidney disease, not just dialysis patients. They offer free publications that emphasize living with kidney disease; these pubs are attractive, with realistic information.

Kidney School

www.kidneyschool.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: This site offers about 16 modules, each on a different topic ranging from dialysis options to sexuality. It is for patients and allows them to pick the topic they want and view the module as often as they wish.

National Kidney Foundation

www.kidney.org

Who recommends it: Jane S. Davis, DNP, CRNP

Why: The patient section of this site contains recipes and health information. Patients can register for the Kidney Peers Program, in which they match up either as a mentor or a mentee with another kidney patient in the US. It covers the range from moderate kidney disease to kidney failure and transplant.

Also recommended: DaVita (www.davita.com); Fresenius Medical Care (www.ultracare-dialysis.com)

Orthopedics

OrthoInfo

orthoinfo.aaos.org/

Who recommends it: Mike Rudzinski, RPh, RPA-C

Why: Endorsed by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, this site offers patients information on the most common musculoskeletal conditions. Includes patient education materials with anatomic pictures and discussion. This is my “go to” site for these conditions; it offers an incredible, comprehensive overview of the condition, options for care including potential surgery, and what the patient can do to improve the condition. It is easy to use for the patient—they just click on the anatomic body part involved and a list of conditions comes up.

Rheumatology

American College of Rheumatology

www.rheumatology.org/Practice/Clinical/Patients/Information_for_Patients/

Who recommends it: Rick Pope, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, CPAAPA

Why: Vetted by the American College of Rheumatologists, whose faculty is nationwide, altruistic, and collaborative, it is chock full of resources that are the standard of thinking and care for rheumatic conditions. It includes “scary” diagnoses such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, with short, patient-specific resources that can take the sting out of the perceived notions of these diseases. The information is available in Spanish and English. The Spanish information sheets can be provided to our Hispanic population and European populations that speak primarily Spanish. This is an awesome service for those of us on the East Coast and likely more helpful in parts of the country where Spanish is spoken more commonly.

How often does this happen to you? You walk into an exam room and ask the patient what brings him in today, and the reply is something like, “Well, doc, I have stomach cancer.” You do a double-take and scan the patient’s chart, looking for test results or notes from a referring provider. Finding nothing, you ask the patient for more information on his diagnosis. To your surprise/dismay/frustration, he says, “Naw, I Googled my symptoms and that’s what I came up with.”

While you can’t control the Web-surfing your patients do before they present, you can influence their information-seeking behavior once you’ve delivered a diagnosis and/or treatment plan. You know they (and their family/caregivers) will have questions about the patient’s condition and how it can be managed for the long term. You hope they’ll come to you for answers. But since they are likely to use the resources at their fingertips, you at least want to ensure the information they receive is accurate and trustworthy.

With that in mind, we asked several Clinician Reviews board members to share the Web sites that they recommend to their patients. Some, including Cathy St. Pierre, PhD, APRN, FNP-BC, FAANP, and Ellen Mandel, DMH, MPA, PA-C, CDE, cited behemoths such as the Mayo Clinic Web site (www.mayoclinic.com/health-information), lauding it for being up to date, easy to access, and “clear and data-driven.” Other board members, as you’ll see below, suggested specialty-specific sites.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PhD, PA, may speak for many clinicians when she explains, “We offer these [resources] to patients and families as part of health education, acknowledging that learning about someone’s condition is the first step to better understanding what they are experiencing and how this may change over time—since most of what we deal with are progressive, lengthy illnesses and chronic disease management.”

If you have reliable Web-based resources that you recommend to your patients, please visit us on Facebook (www.facebook.com/ClinRev) to share them!

Alzheimer’s Disease

ADEAR—Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center

www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers

Who recommends it: Freddi I. Segal-Gidan, PA, PhD

Why: Operated by the NIH/National Institute on Aging specifically to provide consumers with current, accurate, state-of-the-art information about Alzheimer’s disease and dementing illness

Also recommended: Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org); Family Caregiver Alliance (www.caregiver.org); UCSF Memory Center for information on frontotemporal dementia (www.memory.ucsf.edu/ftd); Foundation for Health in Aging (www.healthinaging.org); Kaiser Family Foundation for information about Medicare, Medicaid, and health policy related to aging (www.kff.org)

Cardiology

Cardiac Arrhythmias Research and Education Foundation, Inc (CARE)

www.longqt.org

Who recommends it: Lyle W. Larson, PhD, PA-C

Why: Provides an overview of long QT syndrome (eg, management, genetics); includes links to a study registry for persons with implantable cardioverters-defibrillators who are participating in sports and a complete list of medications to avoid in this patient population. The information is collated and disseminated by health care experts in this field and is updated continuously as new data emerges.

Also recommended: CredibleMeds™ (www.crediblemeds.org)

Dermatology

American Academy of Dermatology: For the Public

www.aad.org/for-the-public

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: Provides patient information about a specific topic or diagnosis that is reliable, up to date, and in understandable language.

eMedicine

http://emedicine.medscape.com

Who recommends it: Joe R. Monroe, MPAS, PA

Why: The information is current and written by authoritative dermatologists or other relevant specialists. References are copious and relevant, and links in the text guide readers to equally good information on related topics.

Caveats: The only problem with eMedicine is that it’s jargon-heavy and meant only for those who are comfortable with the terminology. I reserve this suggestion for more medically erudite patients (eg, nurses or PAs).

Diabetes

DiabetesMine

www.diabetesmine.com/

Who recommends it: Christine Kessler, RN, MN, CNS, ANP, BC-ADM