User login

We are not as clean as we think

We must get control of hospital-related infections. There is no doubt about it. Who hasn’t had a patient almost die from septic shock because of a seemingly innocent indwelling central line or require a colectomy to save his life from overwhelming C. diff colitis?

We’ve all heard the staggering statistics about the number of patients who die needlessly in the hospital each year. It seems unreal. Yet doctors and patients alike are keenly aware of the dangers that lurk within the doors of our nation’s hospitals, and the institutions that are set up to save lives often bear full responsibility for lives lost as a result of human error and sometimes just plain carelessness.

As we are all painfully aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now withholds payments from hospitals when certain conditions are acquired during the hospitalization, even if all reasonable attempts were made to prevent those complications. Among these hospital-acquired conditions are catheter-associated urinary tract infections and vascular catheter–associated infections. Although it may have seemed unrealistic to dramatically decrease these infections, the truth is they can be minimized, and drastically so, often by simple measures.

A recent study examined the behavior of health care workers in four U.S. hospitals (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013;34:69-73 [doi:10.1086/668775]).

"Secret shopper" observers monitored 7,743 visits over 1,989 hours. They found that health care workers performed hand hygiene on exiting rooms with contact precautions 63.2% of the time, compared with 47.4% of the time when there were no contact precautions in place. Unfortunately, the low frequency with which the workers – including physicians – performed appropriate hand hygiene in this study demonstrates how far we are from truly optimizing patient safety.

The toll on human life is by far the most important consideration, but millions of dollars of lost revenue is not insignificant. In an effort to decrease the incidence of hospital-acquired infections, many hospitals have devised a variety of overt and covert strategies. Some are as obvious as a computerized reminder to consider removing a foley catheter or central line if it is no longer absolutely necessary. Others are much more obscure, such as the aforementioned secret-shopper approach.

In some institutions, the information obtained may be reported to the hospital administration and serious consequences can ensue for repeat offenders. Hospital privileges may be revoked in serious cases. So remember, whenever you exit (and enter) a patient’s room, perform appropriate hand hygiene. Someone may be watching you.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

We must get control of hospital-related infections. There is no doubt about it. Who hasn’t had a patient almost die from septic shock because of a seemingly innocent indwelling central line or require a colectomy to save his life from overwhelming C. diff colitis?

We’ve all heard the staggering statistics about the number of patients who die needlessly in the hospital each year. It seems unreal. Yet doctors and patients alike are keenly aware of the dangers that lurk within the doors of our nation’s hospitals, and the institutions that are set up to save lives often bear full responsibility for lives lost as a result of human error and sometimes just plain carelessness.

As we are all painfully aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now withholds payments from hospitals when certain conditions are acquired during the hospitalization, even if all reasonable attempts were made to prevent those complications. Among these hospital-acquired conditions are catheter-associated urinary tract infections and vascular catheter–associated infections. Although it may have seemed unrealistic to dramatically decrease these infections, the truth is they can be minimized, and drastically so, often by simple measures.

A recent study examined the behavior of health care workers in four U.S. hospitals (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013;34:69-73 [doi:10.1086/668775]).

"Secret shopper" observers monitored 7,743 visits over 1,989 hours. They found that health care workers performed hand hygiene on exiting rooms with contact precautions 63.2% of the time, compared with 47.4% of the time when there were no contact precautions in place. Unfortunately, the low frequency with which the workers – including physicians – performed appropriate hand hygiene in this study demonstrates how far we are from truly optimizing patient safety.

The toll on human life is by far the most important consideration, but millions of dollars of lost revenue is not insignificant. In an effort to decrease the incidence of hospital-acquired infections, many hospitals have devised a variety of overt and covert strategies. Some are as obvious as a computerized reminder to consider removing a foley catheter or central line if it is no longer absolutely necessary. Others are much more obscure, such as the aforementioned secret-shopper approach.

In some institutions, the information obtained may be reported to the hospital administration and serious consequences can ensue for repeat offenders. Hospital privileges may be revoked in serious cases. So remember, whenever you exit (and enter) a patient’s room, perform appropriate hand hygiene. Someone may be watching you.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

We must get control of hospital-related infections. There is no doubt about it. Who hasn’t had a patient almost die from septic shock because of a seemingly innocent indwelling central line or require a colectomy to save his life from overwhelming C. diff colitis?

We’ve all heard the staggering statistics about the number of patients who die needlessly in the hospital each year. It seems unreal. Yet doctors and patients alike are keenly aware of the dangers that lurk within the doors of our nation’s hospitals, and the institutions that are set up to save lives often bear full responsibility for lives lost as a result of human error and sometimes just plain carelessness.

As we are all painfully aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now withholds payments from hospitals when certain conditions are acquired during the hospitalization, even if all reasonable attempts were made to prevent those complications. Among these hospital-acquired conditions are catheter-associated urinary tract infections and vascular catheter–associated infections. Although it may have seemed unrealistic to dramatically decrease these infections, the truth is they can be minimized, and drastically so, often by simple measures.

A recent study examined the behavior of health care workers in four U.S. hospitals (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013;34:69-73 [doi:10.1086/668775]).

"Secret shopper" observers monitored 7,743 visits over 1,989 hours. They found that health care workers performed hand hygiene on exiting rooms with contact precautions 63.2% of the time, compared with 47.4% of the time when there were no contact precautions in place. Unfortunately, the low frequency with which the workers – including physicians – performed appropriate hand hygiene in this study demonstrates how far we are from truly optimizing patient safety.

The toll on human life is by far the most important consideration, but millions of dollars of lost revenue is not insignificant. In an effort to decrease the incidence of hospital-acquired infections, many hospitals have devised a variety of overt and covert strategies. Some are as obvious as a computerized reminder to consider removing a foley catheter or central line if it is no longer absolutely necessary. Others are much more obscure, such as the aforementioned secret-shopper approach.

In some institutions, the information obtained may be reported to the hospital administration and serious consequences can ensue for repeat offenders. Hospital privileges may be revoked in serious cases. So remember, whenever you exit (and enter) a patient’s room, perform appropriate hand hygiene. Someone may be watching you.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

DVT/PE Treatment in the Comfort of Home

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli are, unfortunately, common conditions for which we admit patients to the hospital. While sometimes, the emergency room is able to discharge low-risk patients on Coumadin (warfarin), along with an injectable agent to bridge them until their INR becomes therapeutic, these patients are often best served being admitted, or at the very least, observed.

Yet, in 2012 with the strict guidelines patients must attain to even meet admission criteria, it is imperative that we treat our patients as effectively as possibly, while ensuring their safety and comfort. If they only meet criteria for observation status, we also must be particularly mindful of how much their hospital care will affect their wallets.

And surely, I am not alone in spending large chunks of time contacting patients’ pharmacists and waiting on hold for what can seem to be an eternity in the midst of a hectic day, only to find out that their copay for the injectable agent is several hundreds of dollars, which they cannot afford, so they cannot be safely discharged home since they cannot continue treatment at home.

It’s probably obvious that I am no fan of warfarin. All the sweet little old ladies and gentlemen who are admitted with potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal hemorrhages, severe hematuria, or other sources of blood loss simply because they were put on a medication that made their INR shoot up can be really disheartening. But if the options are warfarin or the potentially lethal complications it is meant to prevent, naturally, we prescribe it without hesitation.

Needless to say, I was thrilled a few weeks ago when the Food and Drug Administration approved a drug for oral treatment of DVT/PE. Rivaroxaban is a well-established drug used for atrial fibrillation. Now it has an indication to treat deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. It can be used for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, treatment and secondary prophylaxis of both DVT and pulmonary embolism, and even postop DVT prophylaxis after hip repair or arthroplasty of the knee. And since it is not a newbie in the market, many insurance companies already cover it with a reasonable copay.

I, for one, remain elated at the implications of having a pill that will allow me to treat my patients effectively in the comfort of their own home, with no painful injections or regular visits to the lab to get their INR checked, and I know our patients will love having this option as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli are, unfortunately, common conditions for which we admit patients to the hospital. While sometimes, the emergency room is able to discharge low-risk patients on Coumadin (warfarin), along with an injectable agent to bridge them until their INR becomes therapeutic, these patients are often best served being admitted, or at the very least, observed.

Yet, in 2012 with the strict guidelines patients must attain to even meet admission criteria, it is imperative that we treat our patients as effectively as possibly, while ensuring their safety and comfort. If they only meet criteria for observation status, we also must be particularly mindful of how much their hospital care will affect their wallets.

And surely, I am not alone in spending large chunks of time contacting patients’ pharmacists and waiting on hold for what can seem to be an eternity in the midst of a hectic day, only to find out that their copay for the injectable agent is several hundreds of dollars, which they cannot afford, so they cannot be safely discharged home since they cannot continue treatment at home.

It’s probably obvious that I am no fan of warfarin. All the sweet little old ladies and gentlemen who are admitted with potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal hemorrhages, severe hematuria, or other sources of blood loss simply because they were put on a medication that made their INR shoot up can be really disheartening. But if the options are warfarin or the potentially lethal complications it is meant to prevent, naturally, we prescribe it without hesitation.

Needless to say, I was thrilled a few weeks ago when the Food and Drug Administration approved a drug for oral treatment of DVT/PE. Rivaroxaban is a well-established drug used for atrial fibrillation. Now it has an indication to treat deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. It can be used for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, treatment and secondary prophylaxis of both DVT and pulmonary embolism, and even postop DVT prophylaxis after hip repair or arthroplasty of the knee. And since it is not a newbie in the market, many insurance companies already cover it with a reasonable copay.

I, for one, remain elated at the implications of having a pill that will allow me to treat my patients effectively in the comfort of their own home, with no painful injections or regular visits to the lab to get their INR checked, and I know our patients will love having this option as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli are, unfortunately, common conditions for which we admit patients to the hospital. While sometimes, the emergency room is able to discharge low-risk patients on Coumadin (warfarin), along with an injectable agent to bridge them until their INR becomes therapeutic, these patients are often best served being admitted, or at the very least, observed.

Yet, in 2012 with the strict guidelines patients must attain to even meet admission criteria, it is imperative that we treat our patients as effectively as possibly, while ensuring their safety and comfort. If they only meet criteria for observation status, we also must be particularly mindful of how much their hospital care will affect their wallets.

And surely, I am not alone in spending large chunks of time contacting patients’ pharmacists and waiting on hold for what can seem to be an eternity in the midst of a hectic day, only to find out that their copay for the injectable agent is several hundreds of dollars, which they cannot afford, so they cannot be safely discharged home since they cannot continue treatment at home.

It’s probably obvious that I am no fan of warfarin. All the sweet little old ladies and gentlemen who are admitted with potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal hemorrhages, severe hematuria, or other sources of blood loss simply because they were put on a medication that made their INR shoot up can be really disheartening. But if the options are warfarin or the potentially lethal complications it is meant to prevent, naturally, we prescribe it without hesitation.

Needless to say, I was thrilled a few weeks ago when the Food and Drug Administration approved a drug for oral treatment of DVT/PE. Rivaroxaban is a well-established drug used for atrial fibrillation. Now it has an indication to treat deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. It can be used for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, treatment and secondary prophylaxis of both DVT and pulmonary embolism, and even postop DVT prophylaxis after hip repair or arthroplasty of the knee. And since it is not a newbie in the market, many insurance companies already cover it with a reasonable copay.

I, for one, remain elated at the implications of having a pill that will allow me to treat my patients effectively in the comfort of their own home, with no painful injections or regular visits to the lab to get their INR checked, and I know our patients will love having this option as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Moving Forward

The verdict is in. President Barack Hussein Obama won a decisive victory in his bid for reelection and the Democrats will retain control over the Senate. The proverbial "morbidly obese" lady has sung. The incessant flow of attack ads that dominated screens for months on end has ceased; the prophesying pundits have been silenced. And the American people now have a clearer vision of the future of health care in this country. Whether or not you like the outcome of the election, it is truly over. Now it’s time for politicians to get down to business serving the millions of Americans who put them in office.

It’s also time for physicians, nurses, health care executives, and every other American who directly or indirectly plays any role in the delivery of health care in this great nation to come together to boost the quality of care provided to our citizens to an unprecedented level.

Yes, it is conceivable that some physicians will have to pay higher income taxes. But when we were pulling all-nighters with overflowing coffee mug in hand cramming for medical school finals or going without sleep for 36 or more hours working on the hospital wards, we were working toward an indestructible sense of self-worth that is its own tangible reward.

Caring for those who are sick and dying and helping their loved ones is an honor that instills a feeling of value and distinction that many nonphysicians will never experience. Think back to the most memorable patient you had in those early years and imagine their fate had they not had access to medical care.

The Affordable Care Act will open doors for millions of Americans to become insured and have access to preventive services. Much of the charity care physicians already provide will become reimbursed care, helping to assuage concerns many physicians have about their earning potential.

I still believe the vast majority of us went into medicine to help people, not to become rich. People matter. Though we are not elected officials, we still stand in a unique position to influence lives and move this country forward. This is the time to make our profession shine.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

The verdict is in. President Barack Hussein Obama won a decisive victory in his bid for reelection and the Democrats will retain control over the Senate. The proverbial "morbidly obese" lady has sung. The incessant flow of attack ads that dominated screens for months on end has ceased; the prophesying pundits have been silenced. And the American people now have a clearer vision of the future of health care in this country. Whether or not you like the outcome of the election, it is truly over. Now it’s time for politicians to get down to business serving the millions of Americans who put them in office.

It’s also time for physicians, nurses, health care executives, and every other American who directly or indirectly plays any role in the delivery of health care in this great nation to come together to boost the quality of care provided to our citizens to an unprecedented level.

Yes, it is conceivable that some physicians will have to pay higher income taxes. But when we were pulling all-nighters with overflowing coffee mug in hand cramming for medical school finals or going without sleep for 36 or more hours working on the hospital wards, we were working toward an indestructible sense of self-worth that is its own tangible reward.

Caring for those who are sick and dying and helping their loved ones is an honor that instills a feeling of value and distinction that many nonphysicians will never experience. Think back to the most memorable patient you had in those early years and imagine their fate had they not had access to medical care.

The Affordable Care Act will open doors for millions of Americans to become insured and have access to preventive services. Much of the charity care physicians already provide will become reimbursed care, helping to assuage concerns many physicians have about their earning potential.

I still believe the vast majority of us went into medicine to help people, not to become rich. People matter. Though we are not elected officials, we still stand in a unique position to influence lives and move this country forward. This is the time to make our profession shine.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

The verdict is in. President Barack Hussein Obama won a decisive victory in his bid for reelection and the Democrats will retain control over the Senate. The proverbial "morbidly obese" lady has sung. The incessant flow of attack ads that dominated screens for months on end has ceased; the prophesying pundits have been silenced. And the American people now have a clearer vision of the future of health care in this country. Whether or not you like the outcome of the election, it is truly over. Now it’s time for politicians to get down to business serving the millions of Americans who put them in office.

It’s also time for physicians, nurses, health care executives, and every other American who directly or indirectly plays any role in the delivery of health care in this great nation to come together to boost the quality of care provided to our citizens to an unprecedented level.

Yes, it is conceivable that some physicians will have to pay higher income taxes. But when we were pulling all-nighters with overflowing coffee mug in hand cramming for medical school finals or going without sleep for 36 or more hours working on the hospital wards, we were working toward an indestructible sense of self-worth that is its own tangible reward.

Caring for those who are sick and dying and helping their loved ones is an honor that instills a feeling of value and distinction that many nonphysicians will never experience. Think back to the most memorable patient you had in those early years and imagine their fate had they not had access to medical care.

The Affordable Care Act will open doors for millions of Americans to become insured and have access to preventive services. Much of the charity care physicians already provide will become reimbursed care, helping to assuage concerns many physicians have about their earning potential.

I still believe the vast majority of us went into medicine to help people, not to become rich. People matter. Though we are not elected officials, we still stand in a unique position to influence lives and move this country forward. This is the time to make our profession shine.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

At Breast Cancer Month's End, Start of New Commitment

Each October, we celebrate breast cancer survivors, participate in fund-raisers for breast cancer research and awareness, and remember those lost to this brutal disease. As hospitalists, our job is to facilitate the care of our patients suffering from this disease. We admit patients with neutropenic fever after a recent bout of chemotherapy. We order palliative radiation therapy after the cancer has metastasized and causes severe pain and suffering. And, we order morphine drips when all else has failed, and our focus shifts to helping our patients pass on with the most dignity and least pain possible.

As hospitalists, our services typically come into play after the fact, not before. After the complications of chemo; after the cancer has spread; after there is nothing else we can do to prolong the lives of our patients. No doubt, what we do can make a tremendous impact on the lives of our patients, but can we do more? I believe we can.

How many seconds does it take to ask whether our female patients are up to date with their mammograms and Pap smears? Less than 10.

How many seconds would it take to dictate a brief reminder on preventive medical services, such as a screening mammogram, in our H&Ps? Less than 5.

How many women are aware that the American Cancer Society recommends breast MRI along with the yearly mammogram for certain high-risk women? Very few.

Yes, we are all very busy and sometimes it seems if anything else is added to our plates we will explode, but let’s think about the ROI for a moment. If we admit 30 women over age of 40 each month, and spend, on average, 15 seconds inquiring about and recommending routine mammography, at the end of the year we will have invested a whopping 90 minutes of our lives counseling 360 women. If out of those 360 women, 25% (90) are overdue for their mammogram, and a third heed our advice, 30 women will get a mammogram. Since the lifetime risk of breast cancer is close to 1 in 8, chances are, within a year, we could collectively play a vital role in a multitude of women getting an early diagnosis of breast cancer, and thus a high chance of a complete cure.

A few years ago, I had the gut-wrenching experience of watching someone I loved very much die an excruciating death from breast cancer in my home. She told me I could tell her story so others would be spared her fate. Essentially, she waited too long to get a mammogram.

Now I ask you to help me rewrite her story and rewrite the stories of all of our loved ones who have passed away from breast cancer. If even 100 hospitalists will commit to investing 90 minutes over the next year to recommend screening mammography to patients, and perhaps even do a breast exam on some patients when they have a little extra time, I feel confident that someone, somewhere will be spared the ravages of this vicious disease and their deaths will not be in vain.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Each October, we celebrate breast cancer survivors, participate in fund-raisers for breast cancer research and awareness, and remember those lost to this brutal disease. As hospitalists, our job is to facilitate the care of our patients suffering from this disease. We admit patients with neutropenic fever after a recent bout of chemotherapy. We order palliative radiation therapy after the cancer has metastasized and causes severe pain and suffering. And, we order morphine drips when all else has failed, and our focus shifts to helping our patients pass on with the most dignity and least pain possible.

As hospitalists, our services typically come into play after the fact, not before. After the complications of chemo; after the cancer has spread; after there is nothing else we can do to prolong the lives of our patients. No doubt, what we do can make a tremendous impact on the lives of our patients, but can we do more? I believe we can.

How many seconds does it take to ask whether our female patients are up to date with their mammograms and Pap smears? Less than 10.

How many seconds would it take to dictate a brief reminder on preventive medical services, such as a screening mammogram, in our H&Ps? Less than 5.

How many women are aware that the American Cancer Society recommends breast MRI along with the yearly mammogram for certain high-risk women? Very few.

Yes, we are all very busy and sometimes it seems if anything else is added to our plates we will explode, but let’s think about the ROI for a moment. If we admit 30 women over age of 40 each month, and spend, on average, 15 seconds inquiring about and recommending routine mammography, at the end of the year we will have invested a whopping 90 minutes of our lives counseling 360 women. If out of those 360 women, 25% (90) are overdue for their mammogram, and a third heed our advice, 30 women will get a mammogram. Since the lifetime risk of breast cancer is close to 1 in 8, chances are, within a year, we could collectively play a vital role in a multitude of women getting an early diagnosis of breast cancer, and thus a high chance of a complete cure.

A few years ago, I had the gut-wrenching experience of watching someone I loved very much die an excruciating death from breast cancer in my home. She told me I could tell her story so others would be spared her fate. Essentially, she waited too long to get a mammogram.

Now I ask you to help me rewrite her story and rewrite the stories of all of our loved ones who have passed away from breast cancer. If even 100 hospitalists will commit to investing 90 minutes over the next year to recommend screening mammography to patients, and perhaps even do a breast exam on some patients when they have a little extra time, I feel confident that someone, somewhere will be spared the ravages of this vicious disease and their deaths will not be in vain.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Each October, we celebrate breast cancer survivors, participate in fund-raisers for breast cancer research and awareness, and remember those lost to this brutal disease. As hospitalists, our job is to facilitate the care of our patients suffering from this disease. We admit patients with neutropenic fever after a recent bout of chemotherapy. We order palliative radiation therapy after the cancer has metastasized and causes severe pain and suffering. And, we order morphine drips when all else has failed, and our focus shifts to helping our patients pass on with the most dignity and least pain possible.

As hospitalists, our services typically come into play after the fact, not before. After the complications of chemo; after the cancer has spread; after there is nothing else we can do to prolong the lives of our patients. No doubt, what we do can make a tremendous impact on the lives of our patients, but can we do more? I believe we can.

How many seconds does it take to ask whether our female patients are up to date with their mammograms and Pap smears? Less than 10.

How many seconds would it take to dictate a brief reminder on preventive medical services, such as a screening mammogram, in our H&Ps? Less than 5.

How many women are aware that the American Cancer Society recommends breast MRI along with the yearly mammogram for certain high-risk women? Very few.

Yes, we are all very busy and sometimes it seems if anything else is added to our plates we will explode, but let’s think about the ROI for a moment. If we admit 30 women over age of 40 each month, and spend, on average, 15 seconds inquiring about and recommending routine mammography, at the end of the year we will have invested a whopping 90 minutes of our lives counseling 360 women. If out of those 360 women, 25% (90) are overdue for their mammogram, and a third heed our advice, 30 women will get a mammogram. Since the lifetime risk of breast cancer is close to 1 in 8, chances are, within a year, we could collectively play a vital role in a multitude of women getting an early diagnosis of breast cancer, and thus a high chance of a complete cure.

A few years ago, I had the gut-wrenching experience of watching someone I loved very much die an excruciating death from breast cancer in my home. She told me I could tell her story so others would be spared her fate. Essentially, she waited too long to get a mammogram.

Now I ask you to help me rewrite her story and rewrite the stories of all of our loved ones who have passed away from breast cancer. If even 100 hospitalists will commit to investing 90 minutes over the next year to recommend screening mammography to patients, and perhaps even do a breast exam on some patients when they have a little extra time, I feel confident that someone, somewhere will be spared the ravages of this vicious disease and their deaths will not be in vain.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Medicare of the Future

As hospitalists, we likely see a disproportionate number of Medicare patients, compared with our primary care colleagues. After all, the healthy 24-year-old newlywed who is seeking counseling on choosing a safe and effective birth control method is unlikely to end up in the emergency department three or four times a year; nor is the 40-year-old who goes to his doctor kicking and screaming because his wife demands he get a checkup at least once every few years.

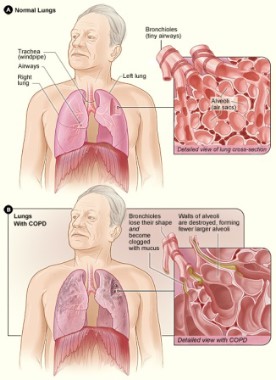

On the contrary, a typical day in the life of a hospitalist focuses on treating heart failure and COPD exacerbations (plus or minus pneumonia), and controlling the ventricular rate in our atrial fibrillation patients. Naturally, these patient are typically older, often seniors who receive Medicare. So, what will Medicare look like in the future?

There has been a lot in the news recently about vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan’s Medicare proposal. I, like many others, was ignorant of specific details of the proposal. I heard "End Medicare as we know it" and immediately my mind conjured up images of frail, elderly Americans being unable to access quality health care and systemically falling through the cracks of a scary system. Based on the interpretation and (sometimes hidden) agenda of various media, I heard wildly different takes on his plan, so I went to his website and read up on it.

In a nutshell, starting in 2023, seniors would be able to choose between private plans competing alongside the traditional fee-for-service option through a new system called the Medicare Exchange. Under this plan, Medicare would provide seniors with payments to pay for or offset the chosen plan’s premiums. In addition, to prevent insurers from structuring their offerings to weed out the sickest patients, all participating plans would be mandated to offer insurance to all seniors.

After reading his plan, I became much less apprehensive about the future of Medicare, should the Romney/Ryan ticket be successful in November. Nevertheless, I am concerned about having a voucher program to help pay for the cost of health care. Though under Ryan’s plan, the voucher amount would escalate over time, who’s to say that the cost of health insurance will not outpace even the voucher? Another concern is that since many elderly patients have decreased cognition in their twilight years, won’t they be at risk for being taken by unscrupulous businesses that always seem to find their way to any revenue stream?

And if President Obama is successful in his bid to remain in the Oval Office? What would Medicare look like then? According to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Affordable Care Act, President Obama’s signature legislation, is expected to lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries by $208 billion through 2021. And, as we all know by now, there will be lower payments to hospitals relative to hospital-acquired conditions, and, in some cases, readmissions. Meanwhile, patient safety through the Partnership for Patients takes a front seat in the ACA plan.

Regardless of who wins the White House in November, there is the potential for huge changes in Medicare. Let us hope (and pray) that the vast majority of changes will be good ones for our patients, and ourselves.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

**This column was updated on Aug. 22, 2012.

As hospitalists, we likely see a disproportionate number of Medicare patients, compared with our primary care colleagues. After all, the healthy 24-year-old newlywed who is seeking counseling on choosing a safe and effective birth control method is unlikely to end up in the emergency department three or four times a year; nor is the 40-year-old who goes to his doctor kicking and screaming because his wife demands he get a checkup at least once every few years.

On the contrary, a typical day in the life of a hospitalist focuses on treating heart failure and COPD exacerbations (plus or minus pneumonia), and controlling the ventricular rate in our atrial fibrillation patients. Naturally, these patient are typically older, often seniors who receive Medicare. So, what will Medicare look like in the future?

There has been a lot in the news recently about vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan’s Medicare proposal. I, like many others, was ignorant of specific details of the proposal. I heard "End Medicare as we know it" and immediately my mind conjured up images of frail, elderly Americans being unable to access quality health care and systemically falling through the cracks of a scary system. Based on the interpretation and (sometimes hidden) agenda of various media, I heard wildly different takes on his plan, so I went to his website and read up on it.

In a nutshell, starting in 2023, seniors would be able to choose between private plans competing alongside the traditional fee-for-service option through a new system called the Medicare Exchange. Under this plan, Medicare would provide seniors with payments to pay for or offset the chosen plan’s premiums. In addition, to prevent insurers from structuring their offerings to weed out the sickest patients, all participating plans would be mandated to offer insurance to all seniors.

After reading his plan, I became much less apprehensive about the future of Medicare, should the Romney/Ryan ticket be successful in November. Nevertheless, I am concerned about having a voucher program to help pay for the cost of health care. Though under Ryan’s plan, the voucher amount would escalate over time, who’s to say that the cost of health insurance will not outpace even the voucher? Another concern is that since many elderly patients have decreased cognition in their twilight years, won’t they be at risk for being taken by unscrupulous businesses that always seem to find their way to any revenue stream?

And if President Obama is successful in his bid to remain in the Oval Office? What would Medicare look like then? According to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Affordable Care Act, President Obama’s signature legislation, is expected to lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries by $208 billion through 2021. And, as we all know by now, there will be lower payments to hospitals relative to hospital-acquired conditions, and, in some cases, readmissions. Meanwhile, patient safety through the Partnership for Patients takes a front seat in the ACA plan.

Regardless of who wins the White House in November, there is the potential for huge changes in Medicare. Let us hope (and pray) that the vast majority of changes will be good ones for our patients, and ourselves.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

**This column was updated on Aug. 22, 2012.

As hospitalists, we likely see a disproportionate number of Medicare patients, compared with our primary care colleagues. After all, the healthy 24-year-old newlywed who is seeking counseling on choosing a safe and effective birth control method is unlikely to end up in the emergency department three or four times a year; nor is the 40-year-old who goes to his doctor kicking and screaming because his wife demands he get a checkup at least once every few years.

On the contrary, a typical day in the life of a hospitalist focuses on treating heart failure and COPD exacerbations (plus or minus pneumonia), and controlling the ventricular rate in our atrial fibrillation patients. Naturally, these patient are typically older, often seniors who receive Medicare. So, what will Medicare look like in the future?

There has been a lot in the news recently about vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan’s Medicare proposal. I, like many others, was ignorant of specific details of the proposal. I heard "End Medicare as we know it" and immediately my mind conjured up images of frail, elderly Americans being unable to access quality health care and systemically falling through the cracks of a scary system. Based on the interpretation and (sometimes hidden) agenda of various media, I heard wildly different takes on his plan, so I went to his website and read up on it.

In a nutshell, starting in 2023, seniors would be able to choose between private plans competing alongside the traditional fee-for-service option through a new system called the Medicare Exchange. Under this plan, Medicare would provide seniors with payments to pay for or offset the chosen plan’s premiums. In addition, to prevent insurers from structuring their offerings to weed out the sickest patients, all participating plans would be mandated to offer insurance to all seniors.

After reading his plan, I became much less apprehensive about the future of Medicare, should the Romney/Ryan ticket be successful in November. Nevertheless, I am concerned about having a voucher program to help pay for the cost of health care. Though under Ryan’s plan, the voucher amount would escalate over time, who’s to say that the cost of health insurance will not outpace even the voucher? Another concern is that since many elderly patients have decreased cognition in their twilight years, won’t they be at risk for being taken by unscrupulous businesses that always seem to find their way to any revenue stream?

And if President Obama is successful in his bid to remain in the Oval Office? What would Medicare look like then? According to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Affordable Care Act, President Obama’s signature legislation, is expected to lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries by $208 billion through 2021. And, as we all know by now, there will be lower payments to hospitals relative to hospital-acquired conditions, and, in some cases, readmissions. Meanwhile, patient safety through the Partnership for Patients takes a front seat in the ACA plan.

Regardless of who wins the White House in November, there is the potential for huge changes in Medicare. Let us hope (and pray) that the vast majority of changes will be good ones for our patients, and ourselves.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

**This column was updated on Aug. 22, 2012.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis for COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations are a leading cause of admission and readmission in 2012, and they consume and exact a great toll on our patients while consuming a tremendous amount of resources. According to the American Lung Association, COPD is the third- leading cause of death, and it cost an estimated $50 billion in 2010 alone.

Although the typical day in the life of a hospitalist can be hectic, it is important for us to take the time to address simple yet crucial issues that impact the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations. There are no magic bullets, but sometimes the basics can go a long way, as is the case with COPD treatment.

My colleague, pulmonologist William Han of Glen Burnie, Md., offers the following reminders:

• Smoking cessation. "Counseling patients to seek treatment as soon as possible when they experience symptoms of an exacerbation is ... of paramount importance, since steroids and antibiotics can often prevent an [emergency department] visit and a protracted hospitalization," he said. Most of us have had patients with advanced COPD who were on home oxygen and who, despite intense counseling, vowed to smoke until the day they died. Unfortunately, many of them did just that, as a result of this extraordinarily addictive habit.

• Vaccination. This is "of tremendous importance. We physicians tend to forget to check on the status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines," Dr. Han said.

• Inhaler skills. "Many patients (and their physicians) do not know the correct way to use HFAs [hydrofluoroalkane inhalers]," Dr. Han noted. Up-to-Date Inc. has an easy-to-use instruction sheet to teach patients how to use their metered dose inhaler, and there are numerous other good resources as well.

COPD exacerbations are as much of a hospitalist issue as a primary care issue. After all, when patients are at their sickest, we are on the front lines working diligently to help them get through that exacerbation and back home to their families, hoping that a long time will elapse before the next one. But despite our best efforts, there are going to be those patients who just can’t stay out of the hospital for any extended period of time.

They stopped smoking a long time ago. They are already in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. They conscientiously use their long-acting inhaled beta-agonist, long-acting inhaled anticholinergic, and inhaled glucocorticoids, and yet their rescue inhalers and nebulizers are still needed frequently. So, what else can we do?

Maybe, after we have tried all the long-established treatments, it’s time to try something new. Because antibiotics work for acute exacerbations, would prophylactic use be beneficial as well?

The authors of a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine think so (2012; 367:340-7). They noted a trial in which researchers compared a daily dose of 250 mg of azithromycin vs. placebo for 1 year, with encouraging results. The trial, which involved 1,142 volunteers, showed that the median time to the first acute exacerbation of COPD was 174 days in the placebo group vs. 266 days in the azithromycin group – quite a profound difference, considering that each acute exacerbation that required hospitalization is associated with a 30-day all-cause death rate of up to 30%, the authors noted.

Macrolides have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects in addition to bactericidal properties, which make them particularly well suited to tackling some of the pathophysiological aberrations of acute exacerbations of COPD.

Although this recommendation is not currently recommended by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease), the findings do merit further consideration. This prophylactic regimen is not for everyone, but for a select group of patients it could be beneficial. The authors even went a step further by recommending considering using 250 mg of azithromycin on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays instead of each day, as tissue concentrations should be adequate to offer significant benefit even at this alternative dosing schedule.

However, it is important to note that certain patients may be at increased risk with this prophylactic regimen, including those on medications (such as statins, Coumadin, and amiodarone) in which significant drug-drug interactions could occur. In addition, patients should be screened for a prolonged QTc interval, as macrolides can prolong the QT interval and thus predispose to torsades de pointes. Even those with other significant heart disease (such as heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) should be considered at higher-than-average risk. Patients with moderate or severe liver disease should also be excluded.

Even though hospitalists will not be following patients every 3 months for their recommended evaluation of medications, signs of ototoxicity, and EKG readings, we can still put a bug in the ear of primary care physicians to consider this approach when all else seems to fail.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Do We Really Need That CAT Scan?

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

Finally, Good News for Patients With DVT/PE

Although thromboembolism, including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a common diagnosis, it is nonetheless a very discouraging one. While it may be unpleasant for us to treat patients who suffer a DVT or acute PE, we see only a portion of what they actually endure. After discharge, chances are we will never see them again.

I often think about how burdensome it will be for my patients to have to see a doctor regularly and have their warfarin (Coumadin) dose adjusted based on the current international normalized ratio (INR), which seems to fluctuate at the drop of a dime.

Most of us have treated patients ranging from robust young men who suffered a PE after a simple arthroscopic knee procedure from a sports injury to sweet, elderly little ladies who have no meaningful transportation to and from the doctor’s office. We worry about how compliant they will be with their prescribed regimen.

When given the diagnosis and treatment, patients almost universally ask how long they will have to stay on warfarin, and many are visibly upset when given the not-so-good news that they should plan to take it for 6 months, maybe longer.

Complications of warfarin therapy are common: the hematocrit of 18 or the hard-to-control epistaxis. But since there is no Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative for managing thromboembolism for the necessary 6 months or so, we have no choice but to prescribe this drug, counsel patients on signs of occult bleeding, and hope for the best. When facing the potential for a fatal pulmonary embolism, the risk-benefit ratio is unquestionably in favor of taking this drug for the vast majority of patients.

But what about the recurrent episodes of DVT or PE after stopping anticoagulation? It is well known that the risk for recurrence persists for years after discontinuing warfarin, particularly in those who had an unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Well, for the first time in ages, there is very encouraging news we can give our patients.

An article published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, Aspirin for Preventing the Recurrence of Venous Thromboembolism, sheds light on a very simple therapy that can make a huge impact (2012; 366:1959-67). The Aspirin for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism study randomized patients who had suffered a first-ever, objectively confirmed, symptomatic unprovoked proximal DVT within 2 weeks of discontinuing vitamin K antagonist therapy. Aspirin 100 mg daily was compared with placebo for 2 years.

Researchers found that aspirin therapy, started after 6-18 months of oral anticoagulant therapy, decreased the rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism by 40% when compared with placebo, with no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding. Finally, good news for our patients with DVT/PE. Hooray!

While we will rarely be the ones discontinuing warfarin after 6 months, just letting our patients know that aspirin therapy can decrease the risk of future events can be very reassuring.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Although thromboembolism, including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a common diagnosis, it is nonetheless a very discouraging one. While it may be unpleasant for us to treat patients who suffer a DVT or acute PE, we see only a portion of what they actually endure. After discharge, chances are we will never see them again.

I often think about how burdensome it will be for my patients to have to see a doctor regularly and have their warfarin (Coumadin) dose adjusted based on the current international normalized ratio (INR), which seems to fluctuate at the drop of a dime.

Most of us have treated patients ranging from robust young men who suffered a PE after a simple arthroscopic knee procedure from a sports injury to sweet, elderly little ladies who have no meaningful transportation to and from the doctor’s office. We worry about how compliant they will be with their prescribed regimen.

When given the diagnosis and treatment, patients almost universally ask how long they will have to stay on warfarin, and many are visibly upset when given the not-so-good news that they should plan to take it for 6 months, maybe longer.

Complications of warfarin therapy are common: the hematocrit of 18 or the hard-to-control epistaxis. But since there is no Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative for managing thromboembolism for the necessary 6 months or so, we have no choice but to prescribe this drug, counsel patients on signs of occult bleeding, and hope for the best. When facing the potential for a fatal pulmonary embolism, the risk-benefit ratio is unquestionably in favor of taking this drug for the vast majority of patients.

But what about the recurrent episodes of DVT or PE after stopping anticoagulation? It is well known that the risk for recurrence persists for years after discontinuing warfarin, particularly in those who had an unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Well, for the first time in ages, there is very encouraging news we can give our patients.

An article published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, Aspirin for Preventing the Recurrence of Venous Thromboembolism, sheds light on a very simple therapy that can make a huge impact (2012; 366:1959-67). The Aspirin for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism study randomized patients who had suffered a first-ever, objectively confirmed, symptomatic unprovoked proximal DVT within 2 weeks of discontinuing vitamin K antagonist therapy. Aspirin 100 mg daily was compared with placebo for 2 years.

Researchers found that aspirin therapy, started after 6-18 months of oral anticoagulant therapy, decreased the rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism by 40% when compared with placebo, with no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding. Finally, good news for our patients with DVT/PE. Hooray!

While we will rarely be the ones discontinuing warfarin after 6 months, just letting our patients know that aspirin therapy can decrease the risk of future events can be very reassuring.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.

Although thromboembolism, including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a common diagnosis, it is nonetheless a very discouraging one. While it may be unpleasant for us to treat patients who suffer a DVT or acute PE, we see only a portion of what they actually endure. After discharge, chances are we will never see them again.

I often think about how burdensome it will be for my patients to have to see a doctor regularly and have their warfarin (Coumadin) dose adjusted based on the current international normalized ratio (INR), which seems to fluctuate at the drop of a dime.

Most of us have treated patients ranging from robust young men who suffered a PE after a simple arthroscopic knee procedure from a sports injury to sweet, elderly little ladies who have no meaningful transportation to and from the doctor’s office. We worry about how compliant they will be with their prescribed regimen.

When given the diagnosis and treatment, patients almost universally ask how long they will have to stay on warfarin, and many are visibly upset when given the not-so-good news that they should plan to take it for 6 months, maybe longer.

Complications of warfarin therapy are common: the hematocrit of 18 or the hard-to-control epistaxis. But since there is no Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative for managing thromboembolism for the necessary 6 months or so, we have no choice but to prescribe this drug, counsel patients on signs of occult bleeding, and hope for the best. When facing the potential for a fatal pulmonary embolism, the risk-benefit ratio is unquestionably in favor of taking this drug for the vast majority of patients.

But what about the recurrent episodes of DVT or PE after stopping anticoagulation? It is well known that the risk for recurrence persists for years after discontinuing warfarin, particularly in those who had an unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Well, for the first time in ages, there is very encouraging news we can give our patients.

An article published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, Aspirin for Preventing the Recurrence of Venous Thromboembolism, sheds light on a very simple therapy that can make a huge impact (2012; 366:1959-67). The Aspirin for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism study randomized patients who had suffered a first-ever, objectively confirmed, symptomatic unprovoked proximal DVT within 2 weeks of discontinuing vitamin K antagonist therapy. Aspirin 100 mg daily was compared with placebo for 2 years.

Researchers found that aspirin therapy, started after 6-18 months of oral anticoagulant therapy, decreased the rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism by 40% when compared with placebo, with no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding. Finally, good news for our patients with DVT/PE. Hooray!

While we will rarely be the ones discontinuing warfarin after 6 months, just letting our patients know that aspirin therapy can decrease the risk of future events can be very reassuring.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care.