User login

Mpox (Monkeypox) Clinical Pearls

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

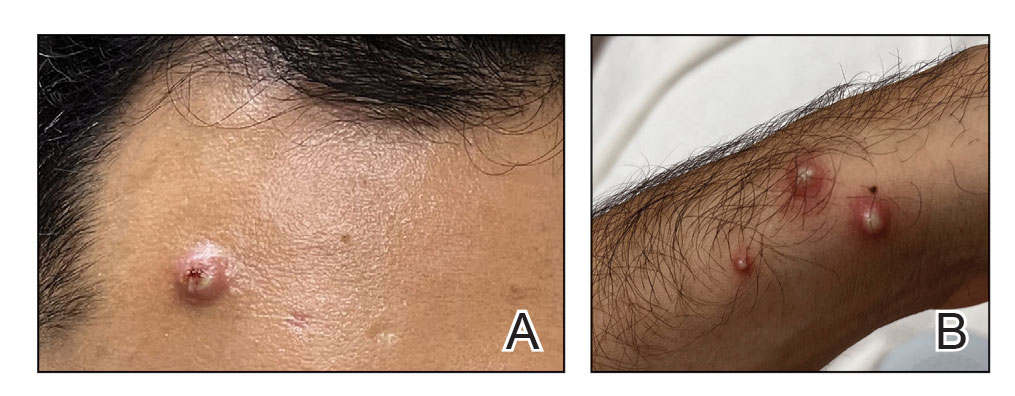

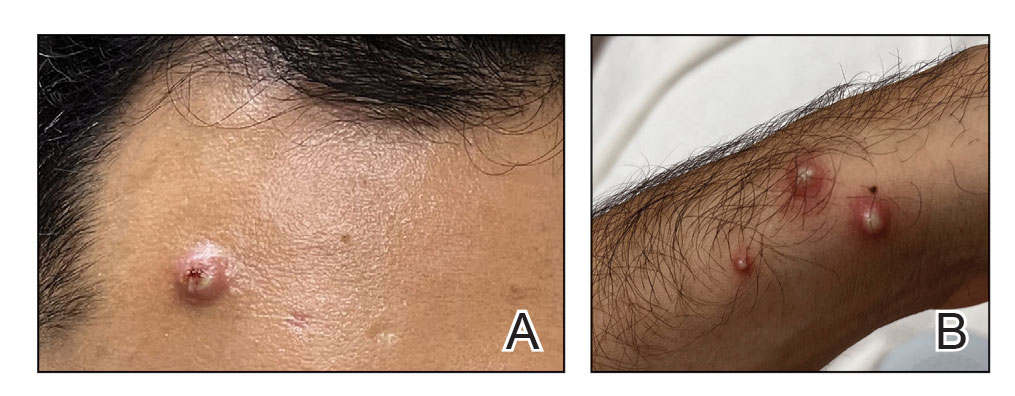

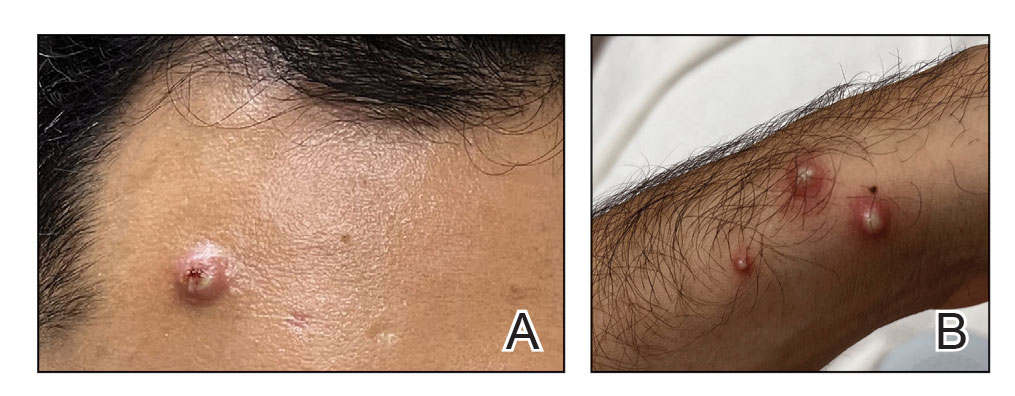

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

The 2022 mpox (monkeypox) virus outbreak represents the latest example of how infectious diseases with previously limited reach can spread in a globalized society. More than 86,000 cases have been reported worldwide, with more than 30,000 cases in the United States as of March 15, 2023.1 Herein, we summarize the key features of mpox infection for the dermatologist.

Mpox Transmission

The mpox virus is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Orthopoxvirus genus and Poxviridae family.2,3 There are 2 types of the mpox virus: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). Clade I causes more severe disease (10% mortality rate), while clade II is associated with lower mortality (1%–3%) and has been split into subclades of IIa (exhibits zoonotic transmission) and IIb (exhibits human-to-human spread).3,4 The current outbreak is caused by clade IIb, and patients typically have no travel history to classic endemic regions.5,6

In endemic countries, mpox transmission is zoonotic from small forest animals. In nonendemic countries, sporadic cases rarely have been reported, including a cluster in the United States in 2003 related to pet prairie dogs. In stark contrast, human-to-human transmission is occurring in the current epidemic mainly via intimate skin-to-skin contact and possibly via sexual fluids, meeting the criteria for a sexually transmitted infection. However, nonsexual transmission does still occur, though it is less common.7 Many of the reported cases so far are in young to middle-aged men who have sex with men (MSM).2,8 However, it is crucial to understand that mpox is not exclusive to the MSM population; the virus has been transmitted to heterosexual males, females, children, and even household pets of infected individuals.2,9,10 Labeling mpox as exclusive to the MSM community is both inaccurate and inappropriately stigmatizing.

Cutaneous Presentation and Diagnosis of Mpox

Mpox has an incubation time of approximately 9 days (range, 7–21 days), after which affected persons develop macular lesions that evolve over 2 to 4 weeks into papules, vesicles, and deep-seated pustules before crusting over and resolving with possible residual scarring.2,3,5,9,11,12 Palmoplantar involvement is a key feature.11 Although in some cases there will be multiple lesions with centrifugal progression, the lesions also may be few in number, with some patients presenting with a single lesion in the anogenital region or on the face, hand, or foot (Figure).6,9 Systemic symptoms such as prodromal fever, lymphadenopathy, and headache are common but not universal.9,13 Potential complications include penile edema, proctitis, bacterial superinfection, tonsillitis, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, and pneumonia.5,9,13

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose mpox infection. The differential diagnosis includes smallpox; varicella-zoster virus (primary or reactivation); secondary syphilis; measles; herpes simplex virus; molluscum contagiosum; hand, foot, and mouth disease; and disseminated gonococcal infection.2,3 For lesions confined to the genital area, sexually transmitted infections (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum) as well as non–sexually related acute genital ulcers (Lipschütz ulcers) should be considered.2

Certain clinical features may help in distinguishing mpox from other diseases. Mpox exhibits synchronous progression and centrifugal distribution when multiple lesions are present; in contrast, the lesions of primary varicella (chickenpox) appear in multiple different stages, and those of localized herpes zoster (shingles) exhibit a dermatomal distribution. When these features are present, mpox causes a greater degree of lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms than primary varicella.3Clinical diagnosis of mpox is more than 90% sensitive but only 9% to 26% specific.3 To confirm the diagnosis, a viral swab vigorously obtained from active skin lesions should be sent in viral transport media for mpox DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction testing, which is available from major laboratories.2,3 Other supportive tests include serum studies for anti–mpox virus immunoglobulins and immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens on skin biopsy specimens.2 When evaluating suspected and confirmed mpox cases, dermatologists should wear a gown, gloves, a fitted N95 mask, and eye protection to prevent infection.5

Treating Mpox

Symptomatic mpox infection can last for up to 2 to 5 weeks.3 The patient is no longer infectious once the lesions have crusted over.3,11 The majority of cases require supportive care only.2,3,5,14 However, mpox remains a potentially fatal disease, with 38 deaths to date in the current outbreak.1 High-risk populations include children younger than 8 years, pregnant women, and individuals who are immunocompromised.15 Tecovirimat, an antiviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox, is available via the expanded access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol to treat severe mpox cases but is not widely available in the United States.6,16-18 Brincidofovir, a prodrug of the antiviral cidofovir, possesses single-patient emergency use Investigational New Drug (e-IND) status for treatment of mpox but also is not widely available in the United States.17 Intravenous vaccinia immune globulin is under consideration for high-risk individuals, but little is known regarding its efficacy against mpox.5,16,17

Two smallpox vaccines—JYNNEOS (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Bio Solutions)—are available for both preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis against mpox virus.19 At this time, only JYNNEOS is FDA approved for the prevention of mpox; ACAM2000 can be used against mpox under the FDA’s EA-IND protocol, which involves additional requirements, including informed consent from the patient.20 ACAM2000 is a live, replication-competent vaccine that carries a warning of increased risk for side effects in patients with cardiac disease, pregnancy, immunocompromise, and a history or presence of eczema and other skin conditions.3,21,22 JYNNEOS is a live but replication-deficient virus and therefore does not carry these warnings.3,21,22

Final Thoughts

Mpox is no longer an obscure illness occurring in limited geographic areas. Dermatologists must remain highly vigilant when evaluating any patient for new-onset vesicular or pustular eruptions to combat this ongoing public health threat. This issue of Cutis® also features a thorough mpox update on the clinical presentation, vaccine guidance, and management.23

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 121, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/

- Srivastava G. Human monkeypox disease [published online August 10, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.08.009

- Bryer J, Freeman EE, Rosenbach M. Monkeypox emerges on a global scale: a historical review and dermatologic primer [published online July 8, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.007

- Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:E2220415120. doi:10.1073 /pnas.2220415120

- Guarner J, Del Rio C, Malani PN. Monkeypox in 2022—what clinicians need to know. JAMA. 2022;328:139-140. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10802

- Looi MK. Monkeypox: what we know about the 2022 outbreak so far [published online August 23, 2022]. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2058

- Allan-Blitz LT, Gandhi M, Adamson P, et al. A position statement on mpox as a sexually transmitted disease [published online December 22, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac960

- Cabanillas B, Murdaca G, Guemari A, et al. A compilation answering 50 questions on monkeypox virus and the current monkeypox outbreak. Allergy. 2023;78:639-662. doi:10.1111/all.15633

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study [published online August 8, 2022]. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2

- Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022;400:658-659. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(22)01487-8

- Ramdass P, Mullick S, Farber HF. Viral skin diseases. Prim Care. 2015;42:517-67. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.006

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: Clinical Recognition. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc .gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

- Mpox Cases by Age and Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox /response/2022/demographics.html

- Kawsar A, Hussain K, Roberts N. The return of monkeypox: key pointers for dermatologists [published online July 29, 2022]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.15357

- Khanna U, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Current outbreak of monkeypox— essentials for the dermatologist [published online June 23, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1170

- Fox T, Gould S, Princy N, et al. Therapeutics for treating mpox in humans. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;3:CD015769. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD015769

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated March 3, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians /treatment.html#anchor_1666886364947

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for tecovirimat use. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www .cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Vaccines During the 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/health-departments/vaccine-considerations.html

- Key Facts About Vaccines to Prevent Monkeypox Disease. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/key-facts-aboutvaccines-prevent-monkeypox-disease

- Smallpox: Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/vaccines.html

- ACAM2000. Package insert. Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc; 2019.

- Cices A, Prasad S, Akselrad M, et al. Mpox update: clinical presentation, vaccination guidance, and management. Cutis. 2023;111:197-202. doi:10.12788/cutis.0745

What Neglected Tropical Diseases Teach Us About Stigma

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

Recognizing and Preventing Arbovirus Infections

What do patients need to know about arboviruses?

Dengue is the most common arbovirus worldwide, with more than 300 million individuals infected each year, most of them asymptomatic carriers. It is the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from Southeast Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Dengue symptoms typically begin 3 to 12 days after exposure and may include fever; headache; conjunctivitis; and a biphasic rash that begins with blanching macular erythema, which patients may mistake for sunburn, followed by a morbilliform to petechial rash with islands of sparing (white islands in a sea of red). Severe dengue (formerly known as dengue hemorrhagic fever) may present with dramatic skin and mucosal hemorrhage including purpura, hemorrhagic bullae, and bleeding from orifices and injection sites, with associated thrombocytopenia and hypotension (dengue shock syndrome). Patients with onset of such symptoms need to go to the emergency department for inpatient management.

Individuals living in the United States should be particularly aware of West Nile virus, with infections reported in all US states in 2017, except Alaska and Hawaii thus far. Transmitted by the bite of the Culex mosquito, most infections are symptomatic; however, up to 20% of patients may present with nonspecific symptoms such as mild febrile or flulike symptoms, nonspecific morbilliform rash, and headaches, and up to 1% of patients may develop encephalitis or meningitis, with approximately 10% mortality rates.

What are your go-to treatments?

Arboviral infections generally are self-limited and there are no specific treatments available. Supportive care, including fluid resuscitation, and analgesia (if needed for joint, muscle, or bone pain) are the mainstays of management. Diagnoses generally are confirmed via viral polymerase chain reaction from serum (<7 days), IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (>4 days), or IgG serologies for later presentations.

Patients should avoid the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if there is a possibility of dengue virus infection, as they may potentiate the risk for hemorrhagic complications in patients with severe dengue. Instead, acetaminophen is recommended for analgesia and antipyretic purposes, if needed.

How do you recommend patients prevent infection while traveling?

Primary prevention of infection and secondary prevention of transmission are important. Although mosquito bed netting is helpful in preventing some mosquito-borne viruses, many arboviruses (ie, dengue, Zika, chikun-gunya) are transmitted by primarily daytime-biting Aedes mosquitoes. In an endemic area, travelers should try to stay within air-conditioned buildings with intact window and door screens. When outdoors, wear long sleeves and pants and use Environmental Protection Agency-registered mosquito repellents. Conventional repellents include the following:

- DEET: concentrations 10% to 30% are safe for children 2 months and older and pregnant women; concentrations around 10% are effective for periods of approximately 2 hours; as the concentration of DEET increases, the duration of protection increases.

- Picaridin: concentrations of 5% to 20%; effective for 4 to 8 hours depending on the concentration; most effective concentration is 20%; is not effective against ticks.

Biopesticide repellents include the following:

- IR3535 (ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate): concentration 10% to 30% has been used as an insect repellent in Europe for 20 years with no substantial adverse effects.

- 2-undecanone: a natural compound from leaves and stems of the wild tomato plant; is a biopesticide product less toxic than conventional pesticides.

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD (the synthesized version of OLE): concentration 30%; "pure" oil of lemon eucalyptus (essential oil not formulated as a repellent) is not recommended.

- Natural oils (eg, soybean, lemongrass, citronella, cedar, peppermint, lavender, geranium) are exempted from Environmental Protection Agency registration; duration of effectiveness is estimated between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

Products that combine sunscreen and repellent are not recommended because sunscreen may need to be reapplied, increasing the toxicity of the repellent. Use separate products, applying sunscreen first and then applying the repellent.

Permethrin-treated clothing may provide an additional measure of protection, though in some endemic areas, resistance has been reported.

Because sexual transmission has been reported for Zika virus (between both male and female partners), any known or possibly infected persons should use condoms. Durations of abstinence or protected sex recommendations vary by situation and more detailed recommendations can be found from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant women and women trying to get pregnant should take preventive measures with respect to Zika due to the possibility of the virus causing severe birth defects (congenital Zika syndrome) including microcephaly, joint deformities, ocular damage, and hypertonia.

What do patients need to know about arboviruses?

Dengue is the most common arbovirus worldwide, with more than 300 million individuals infected each year, most of them asymptomatic carriers. It is the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from Southeast Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Dengue symptoms typically begin 3 to 12 days after exposure and may include fever; headache; conjunctivitis; and a biphasic rash that begins with blanching macular erythema, which patients may mistake for sunburn, followed by a morbilliform to petechial rash with islands of sparing (white islands in a sea of red). Severe dengue (formerly known as dengue hemorrhagic fever) may present with dramatic skin and mucosal hemorrhage including purpura, hemorrhagic bullae, and bleeding from orifices and injection sites, with associated thrombocytopenia and hypotension (dengue shock syndrome). Patients with onset of such symptoms need to go to the emergency department for inpatient management.

Individuals living in the United States should be particularly aware of West Nile virus, with infections reported in all US states in 2017, except Alaska and Hawaii thus far. Transmitted by the bite of the Culex mosquito, most infections are symptomatic; however, up to 20% of patients may present with nonspecific symptoms such as mild febrile or flulike symptoms, nonspecific morbilliform rash, and headaches, and up to 1% of patients may develop encephalitis or meningitis, with approximately 10% mortality rates.

What are your go-to treatments?

Arboviral infections generally are self-limited and there are no specific treatments available. Supportive care, including fluid resuscitation, and analgesia (if needed for joint, muscle, or bone pain) are the mainstays of management. Diagnoses generally are confirmed via viral polymerase chain reaction from serum (<7 days), IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (>4 days), or IgG serologies for later presentations.

Patients should avoid the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if there is a possibility of dengue virus infection, as they may potentiate the risk for hemorrhagic complications in patients with severe dengue. Instead, acetaminophen is recommended for analgesia and antipyretic purposes, if needed.

How do you recommend patients prevent infection while traveling?

Primary prevention of infection and secondary prevention of transmission are important. Although mosquito bed netting is helpful in preventing some mosquito-borne viruses, many arboviruses (ie, dengue, Zika, chikun-gunya) are transmitted by primarily daytime-biting Aedes mosquitoes. In an endemic area, travelers should try to stay within air-conditioned buildings with intact window and door screens. When outdoors, wear long sleeves and pants and use Environmental Protection Agency-registered mosquito repellents. Conventional repellents include the following:

- DEET: concentrations 10% to 30% are safe for children 2 months and older and pregnant women; concentrations around 10% are effective for periods of approximately 2 hours; as the concentration of DEET increases, the duration of protection increases.

- Picaridin: concentrations of 5% to 20%; effective for 4 to 8 hours depending on the concentration; most effective concentration is 20%; is not effective against ticks.

Biopesticide repellents include the following:

- IR3535 (ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate): concentration 10% to 30% has been used as an insect repellent in Europe for 20 years with no substantial adverse effects.

- 2-undecanone: a natural compound from leaves and stems of the wild tomato plant; is a biopesticide product less toxic than conventional pesticides.

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD (the synthesized version of OLE): concentration 30%; "pure" oil of lemon eucalyptus (essential oil not formulated as a repellent) is not recommended.

- Natural oils (eg, soybean, lemongrass, citronella, cedar, peppermint, lavender, geranium) are exempted from Environmental Protection Agency registration; duration of effectiveness is estimated between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

Products that combine sunscreen and repellent are not recommended because sunscreen may need to be reapplied, increasing the toxicity of the repellent. Use separate products, applying sunscreen first and then applying the repellent.

Permethrin-treated clothing may provide an additional measure of protection, though in some endemic areas, resistance has been reported.

Because sexual transmission has been reported for Zika virus (between both male and female partners), any known or possibly infected persons should use condoms. Durations of abstinence or protected sex recommendations vary by situation and more detailed recommendations can be found from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant women and women trying to get pregnant should take preventive measures with respect to Zika due to the possibility of the virus causing severe birth defects (congenital Zika syndrome) including microcephaly, joint deformities, ocular damage, and hypertonia.

What do patients need to know about arboviruses?

Dengue is the most common arbovirus worldwide, with more than 300 million individuals infected each year, most of them asymptomatic carriers. It is the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from Southeast Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Dengue symptoms typically begin 3 to 12 days after exposure and may include fever; headache; conjunctivitis; and a biphasic rash that begins with blanching macular erythema, which patients may mistake for sunburn, followed by a morbilliform to petechial rash with islands of sparing (white islands in a sea of red). Severe dengue (formerly known as dengue hemorrhagic fever) may present with dramatic skin and mucosal hemorrhage including purpura, hemorrhagic bullae, and bleeding from orifices and injection sites, with associated thrombocytopenia and hypotension (dengue shock syndrome). Patients with onset of such symptoms need to go to the emergency department for inpatient management.

Individuals living in the United States should be particularly aware of West Nile virus, with infections reported in all US states in 2017, except Alaska and Hawaii thus far. Transmitted by the bite of the Culex mosquito, most infections are symptomatic; however, up to 20% of patients may present with nonspecific symptoms such as mild febrile or flulike symptoms, nonspecific morbilliform rash, and headaches, and up to 1% of patients may develop encephalitis or meningitis, with approximately 10% mortality rates.

What are your go-to treatments?

Arboviral infections generally are self-limited and there are no specific treatments available. Supportive care, including fluid resuscitation, and analgesia (if needed for joint, muscle, or bone pain) are the mainstays of management. Diagnoses generally are confirmed via viral polymerase chain reaction from serum (<7 days), IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (>4 days), or IgG serologies for later presentations.

Patients should avoid the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if there is a possibility of dengue virus infection, as they may potentiate the risk for hemorrhagic complications in patients with severe dengue. Instead, acetaminophen is recommended for analgesia and antipyretic purposes, if needed.

How do you recommend patients prevent infection while traveling?

Primary prevention of infection and secondary prevention of transmission are important. Although mosquito bed netting is helpful in preventing some mosquito-borne viruses, many arboviruses (ie, dengue, Zika, chikun-gunya) are transmitted by primarily daytime-biting Aedes mosquitoes. In an endemic area, travelers should try to stay within air-conditioned buildings with intact window and door screens. When outdoors, wear long sleeves and pants and use Environmental Protection Agency-registered mosquito repellents. Conventional repellents include the following:

- DEET: concentrations 10% to 30% are safe for children 2 months and older and pregnant women; concentrations around 10% are effective for periods of approximately 2 hours; as the concentration of DEET increases, the duration of protection increases.

- Picaridin: concentrations of 5% to 20%; effective for 4 to 8 hours depending on the concentration; most effective concentration is 20%; is not effective against ticks.

Biopesticide repellents include the following:

- IR3535 (ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate): concentration 10% to 30% has been used as an insect repellent in Europe for 20 years with no substantial adverse effects.

- 2-undecanone: a natural compound from leaves and stems of the wild tomato plant; is a biopesticide product less toxic than conventional pesticides.

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD (the synthesized version of OLE): concentration 30%; "pure" oil of lemon eucalyptus (essential oil not formulated as a repellent) is not recommended.

- Natural oils (eg, soybean, lemongrass, citronella, cedar, peppermint, lavender, geranium) are exempted from Environmental Protection Agency registration; duration of effectiveness is estimated between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

Products that combine sunscreen and repellent are not recommended because sunscreen may need to be reapplied, increasing the toxicity of the repellent. Use separate products, applying sunscreen first and then applying the repellent.

Permethrin-treated clothing may provide an additional measure of protection, though in some endemic areas, resistance has been reported.

Because sexual transmission has been reported for Zika virus (between both male and female partners), any known or possibly infected persons should use condoms. Durations of abstinence or protected sex recommendations vary by situation and more detailed recommendations can be found from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant women and women trying to get pregnant should take preventive measures with respect to Zika due to the possibility of the virus causing severe birth defects (congenital Zika syndrome) including microcephaly, joint deformities, ocular damage, and hypertonia.