User login

Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies

Introduction

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines hospitalists as physicians whose primary professional focus is the comprehensive general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to Hospital Medicine.1 It is estimated that there are up to 2500 pediatric hospitalists in the United States, with continued growth due to the converging needs for a dedicated focus on patient safety, quality improvement, hospital throughput, and inpatient teaching.2‐9 (Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM), as defined today, has been practiced in the United States for at least 30 years10 and continues to evolve as an area of specialization, with the refinement of a distinct knowledgebase and skill set focused on the provision of high quality general pediatric care in the inpatient setting. PHM is the latest site‐specific specialty to emerge from the field of general pediatrics it's development analogous to the evolution of critical care or emergency medicine during previous decades.11 Adult hospital medicine has defined itself within the field of general internal medicine12 and has recently received approval to provide a recognized focus of practice exam in 2010 for those re‐certifying with the American Board of Internal Medicine,13 PHM is creating an identity as a subspecialty practice with distinct focus on inpatient care for children within the larger context of general pediatric care.8, 14

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies were created to help define the roles and expectations for pediatric hospitalists, regardless of practice setting. The intent is to provide a unified approach toward identifying the specific body of knowledge and measurable skills needed to assure delivery of the highest quality of care for all hospitalized pediatric patients. Most children requiring hospitalization in the United States are hospitalized in community settings where subspecialty support is more limited and many pediatric services may be unavailable. Children with complex, chronic medical problems, however, are more likely to be hospitalized at a tertiary care or academic institutions. In order to unify pediatric hospitalists who work in different practice environments, the PHM Core Competencies were constructed to represent the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and systems improvements that all pediatric hospitalists can be expected to acquire and maintain.

Furthermore, the content of the PHM Core Competencies reflect the fact that children are a vulnerable population. Their care requires attention to many elements which distinguishes it from that given to the majority of the adult population: dependency, differences in developmental physiology and behavior, occurrence of congenital genetic disorders and age‐based clinical conditions, impact of chronic disease states on whole child development, and weight‐based medication dosing often with limited guidance from pediatric studies, to name a few. Awareness of these needs must be heightened when a child enters the hospital where diagnoses, procedures, and treatments often include use of high‐risk modalities and require coordination of care across multiple providers.

Pediatric hospitalists commonly work to improve the systems of care in which they operate and therefore both clinical and non‐clinical topics are included. The 54 chapters address the fundamental and most common components of inpatient care but are not an extensive review of all aspects of inpatient medicine encountered by those caring for hospitalized children. Finally, the PHM Core Competencies are not intended for use in assessing proficiency immediately post‐residency, but do provide a framework for the education and evaluation of both physicians‐in‐training and practicing hospitalists. Meeting these competencies is anticipated to take from one to three years of active practice in pediatric hospital medicine, and may be reached through a combination of practice experience, course work, self‐directed work, and/or formalized training.

Methods

Timeline

In 2002, SHM convened an educational summit from which there was a resolution to create core competencies. Following the summit, the SHM Pediatric Core Curriculum Task Force (CCTF) was created, which included 12 pediatric hospitalists practicing in academic and community facilities, as well as teaching and non‐teaching settings, and occupying leadership positions within institutions of varied size and geographic location. Shortly thereafter, in November 2003, approximately 130 pediatric hospitalists attended the first PHM meeting in San Antonio, Texas.11 At this meeting, with support from leaders in pediatric emergency medicine, first discussions regarding PHM scope of practice were held.

Formal development of the competencies began in 2005 in parallel to but distinct from SHM's adult work, which culminated in The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development published in 2006. The CCTF divided into three groups, focused on clinical, procedural, and systems‐based topics. Face‐to‐face meetings were held at the SHM annual meetings, with most work being completed by phone and electronically in the interim periods. In 2007, due to the overlapping interests of the three core pediatric societies, the work was transferred to leaders within the APA. In 2008 the work was transferred back to the leadership within SHM. Since that time, external reviewers were solicited, new chapters created, sections re‐aligned, internal and external reviewer comments incorporated, and final edits for taxonomy, content, and formatting were completed (Table 1).

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Feb 2002 | SHM Educational Summit held and CCTF created |

| Oct 2003 | 1st PHM meeting held in San Antonio |

| 2003‐2007 | Chapter focus determined; contributors engaged |

| 2007‐2008 | APA PHM Special Interest Group (SIG) review; creation of separate PHM Fellowship Competencies (not in this document) |

| Aug 2008‐Oct 2008 | SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF members resume work; editorial review |

| Oct 2008‐Mar 2009 | Internal review: PHM Fellowship Director, AAP, APA, and SHM section/committee leader, and key national PHM leader reviews solicited and returned |

| Mar 2009 | PHM Fellowship Director comments addressed; editorial review |

| Mar‐Apr 2009 | External reviewers solicited from national agencies and societies relevant to PHM |

| Apr‐July 2009 | External reviewer comments returned |

| July‐Oct 2009 | Contributor review of all comments; editorial review, sections revised |

| Oct 2009 | Final review: Chapters to SHM subcommittees and Board |

Areas of Focused Practice

The PHM Core Competencies were conceptualized similarly to the SHM adult core competencies. Initial sections were divided into clinical conditions, procedures, and systems. However as content developed and reviewer comments were addressed, the four final sections were modified to those noted in Table 2. For the Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions, the goal was to select conditions most commonly encountered by pediatric hospitalists. Non‐surgical diagnosis‐related group (DRG) conditions were selected from the following sources: The Joint Commission's (TJC) Oryx Performance Measures Report15‐16 (asthma, abdominal pain, acute gastroenteritis, simple pneumonia); Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System Dataset (CHCA PHIS, Shawnee Mission, KS), and relevant publications on common pediatric hospitalizations.17 These data were compared to billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing free‐standing children's and community hospitals, teaching and non‐teaching settings, and urban and rural locations. The 22 clinical conditions chosen by the CCTF were those most relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.

| Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions | Specialized Clinical Services | Core Skills | Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute abdominal pain and the acute abdomen | Neonatal fever | Child abuse and neglect | Bladder catheterization/suprapubic bladder tap | Advocacy |

| Apparent life‐threatening event | Neonatal jaundice | Hospice and palliative care | Electrocardiogram interpretation | Business practices |

| Asthma | Pneumonia | Leading a healthcare team | Feeding tubes | Communication |

| Bone and joint infections | Respiratory failure | Newborn care and delivery room management | Fluids and electrolyte management | Continuous quality improvement |

| Bronchiolitis | Seizures | Technology‐dependent children | Intravenous access and phlebotomy | Cost‐effective care |

| Central nervous system infections | Shock | Transport of the critically ill child | Lumbar puncture | Education |

| Diabetes mellitus | Sickle cell disease | Non‐invasive monitoring | Ethics | |

| Failure to thrive | Skin and soft tissue infection | Nutrition | Evidence‐based medicine | |

| Fever of unknown origin | Toxic ingestion | Oxygen delivery and airway management | Health information systems | |

| Gastroenteritis | Upper airway infections | Pain management | Legal issues/risk management | |

| Kawasaki disease | Urinary tract infections | Pediatric advanced life support | Patient safety |

The Specialized Clinical Servicessection addresses important components of care that are not DRG‐based and reflect the unique needs of hospitalized children, as assessed by the CCTF, editors, and contributors. Core Skillswere chosen based on the HCUP Factbook 2 Procedures,18 billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing the same settings listed above, and critical input from reviewers. Depending on the individual setting, pediatric hospitalists may require skills in areas not found in these 11 chapters, such as chest tube placement or ventilator management. The list is therefore not exhaustive, but rather representative of skills most pediatric hospitalists should maintain.

The Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Healthchapters are likely the most dissimilar to any core content taught in traditional residency programs. While residency graduates are versed in some components listed in these chapters, comprehensive education in most of these competencies is currently lacking. Improvement of healthcare systems is an essential element of pediatric hospital medicine, and unifies all pediatric hospitalists regardless of practice environment or patient population. Therefore, this section includes chapters that not only focus on systems of care, but also on advancing child health through advocacy, research, education, evidence‐based medicine, and ethical practice. These chapters were drawn from a combination of several sources: expectations of external agencies (TJC, Center for Medicaid and Medicare) related to the specific nonclinical work in which pediatric hospitalists are integrally involved; expectations for advocacy as best defined by the AAP and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI); the six core competency domains mandated by the Accrediting Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), and hospital medical staff offices as part of Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE) and Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE)16; and assessment of responsibilities and leadership roles fulfilled by pediatric hospitalists in all venues. In keeping with the intent of the competencies to be timeless, the competency elements call out the need to attend to the changing goals of these groups as well as those of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the Alliance for Pediatric Quality (which consists of ABP, AAP, TJC, CHCA, NACHRI), and local hospital systems leaders.

Contributors and Review

The CCTF selected section (associate) editors from SHM based on established expertise in each area, with input from the SHM Pediatric and Education Committees and the SHM Board. As a collaborative effort, authors for various chapters were solicited in consultation with experts from the AAP, APA, and SHM, and included non‐hospitalists with reputations as experts in various fields. Numerous SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF conference calls were held to review hospital and academic appointments, presentations given, and affiliations relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine. This vetting process resulted in a robust author list representing diverse geographic and practice settings. Contributors were provided with structure (Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Systems subsections) and content (timeless, competency based) guidelines.

The review process was rigorous, and included both internal and external reviewers. The APA review in 2007 included the PHM Special Interest Group as well as the PHM Fellowship Directors (Table 1). After return to SHM and further editing, the internal review commenced which focused on content and scope. The editors addressed the resulting suggestions and worked to standardize formatting and use of Bloom's taxonomy.19 A list of common terms and phrases were created to add consistency between chapters. External reviewers were first mailed a letter requesting interest, which was followed up by emails, letters, and phone calls to encourage feedback. External review included 29 solicited agencies and societies (Table 3), with overall response rate of 66% (41% for Groups I and II). Individual contributors then reviewed comments specific to their chapters, with associate editor overview of their respective sections. The editors reviewed each chapter individually multiple times throughout the 2007‐2009 years, contacting individual contributors and reviewers by email and phone. Editors concluded a final comprehensive review of all chapters in late 2009.

| I. Academic and certifying societies |

| Academic Pediatric Association |

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Pediatric Residency Review Committee |

| American Academy of Family Physicians |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Board |

| American Academy of Pediatrics National Committee on Hospital Care |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American Board of Family Medicine |

| American Board of Pediatrics |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Pediatric Society |

| Association of American Medical Colleges |

| Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs (AMSPDC) |

| Association of Pediatric Program Directors |

| Council on Teaching Hospitals |

| Society of Pediatric Research |

| II. Stakeholder agencies |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Hospital Association (AHA) |

| American Nurses Association |

| American Society of Health‐System Pharmacists |

| Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA) |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement |

| National Association for Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI) |

| National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) |

| National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) |

| National Quality Forum |

| Quality Resources International |

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

| The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Hospitals and Organizations (TJC) |

| III. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowship directors |

| Boston Children's |

| Children's Hospital Los Angeles |

| Children's National D.C. |

| Emory |

| Hospital for Sick Kids Toronto |

| Rady Children's San Diego University of California San Diego |

| Riley Children's Hospital Indiana |

| University of South Florida, All Children's Hospital |

| Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine |

| IV. SHM, APA, AAP Leadership and committee chairs |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine |

| Academic Pediatric Association PHM Special Interest Group |

| SHM Board |

| SHM Education Committee |

| SHM Family Practice Committee |

| SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee |

| SHM IT Task Force |

| SHM Journal Editorial Board |

| SHM Palliative Care Task Force |

| SHM Practice Analysis Committee |

| SHM Public Policy Committee |

| SHM Research Committee |

Chapter Content

Each of the 54 chapters within the four sections of these competencies is presented in the educational theory of learning domains: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, with a final Systems domain added to reflect the emphasis of hospitalist practice on improving healthcare systems. Each chapter is designed to stand alone, which may assist with development of curriculum at individual practice locations. Certain key phrases are apparent throughout, such as lead, coordinate, or participate in and work with hospital and community leaders to which were designed to note the varied roles in different practice settings. Some chapters specifically comment on the application of competency bullets given the unique and differing roles and expectations of pediatric hospitalists, such as research and education. Chapters state specific proficiencies expected wherever possible, with phrases and wording selected to help guide learning activities to achieve the competency.

Application and Future Directions

Although pediatric hospitalists care for children in many settings, these core competencies address the common expectations for any venue. Pediatric hospital medicine requires skills in acute care clinical medicine that attend to the changing needs of hospitalized children. The core of pediatric hospital medicine is dedicated to the care of children in the geographic hospital environment between emergency medicine and tertiary pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Pediatric hospitalists provide care in related clinical service programs that are linked to hospital systems. In performing these activities, pediatric hospitalists consistently partner with ambulatory providers and subspecialists to render coordinated care across the continuum for a given child. Pediatric hospital medicine is an interdisciplinary practice, with focus on processes of care and clinical quality outcomes based in evidence. Engagement in local, state, and national initiatives to improve child health outcomes is a cornerstone of pediatric hospitalists' practice. These competencies provide the framework for creation of curricula that can reflect local issues and react to changing evidence.

As providers of systems‐based care, pediatric hospitalists are called upon more and more to render care and provide leadership in clinical arenas that are integral to healthcare organizations, such as home health care, sub‐acute care facilities, and hospice and palliative care programs. The practice of pediatric hospital medicine has evolved to its current state through efforts of many represented in the competencies as contributors, associate editors, editors, and reviewers. Pediatric hospitalists are committed to leading change in healthcare for hospitalized children, and are positioned well to address the interests and needs of community and urban, teaching and non‐teaching facilities, and the children and families they serve. These competencies reflect the areas of focused practice which, similar to pediatric emergency medicine, will no doubt be refined but not fundamentally changed in future years. The intent, we hope, is clear: to provide excellence in clinical care, accountability for practice, and lead improvements in healthcare for hospitalized children.

- Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). Definition of a Hospitalist. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=General_Information 2009.

- .Pediatric Hospitalists Membership Numbers. In.Philadelphia:Society of Hospital Medicine, PA 19130;2009.

- , .The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?.Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- , .The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

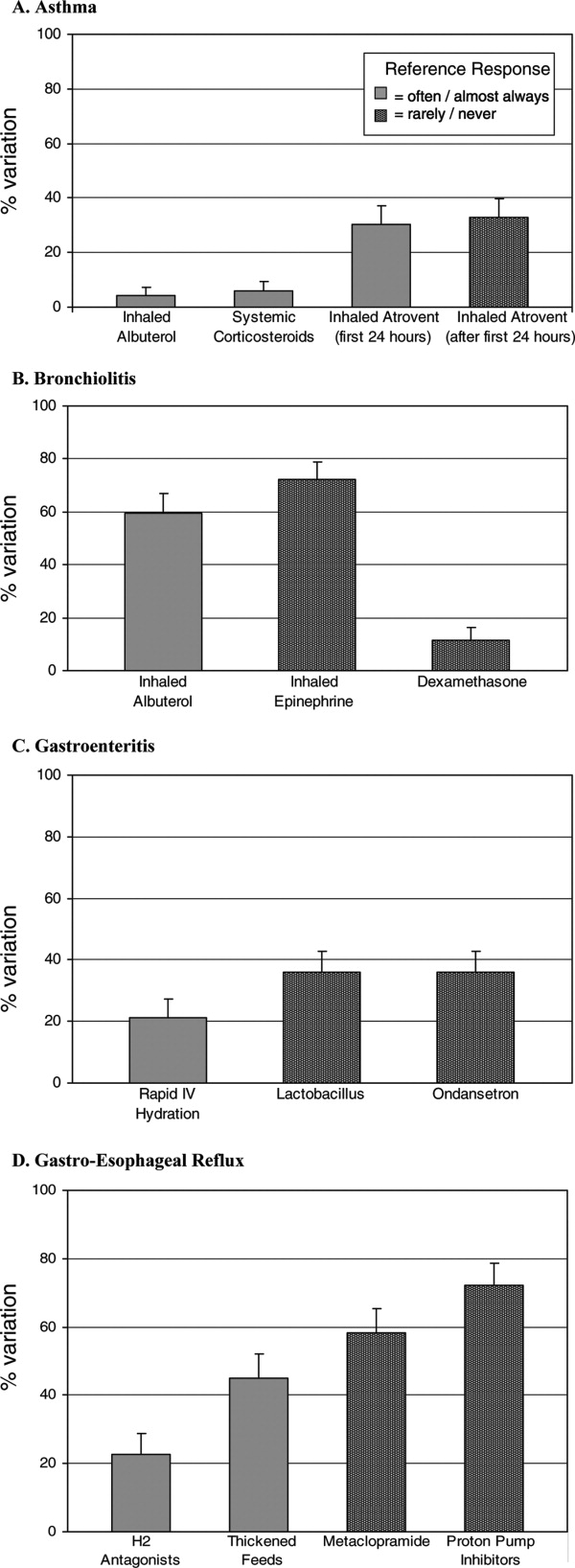

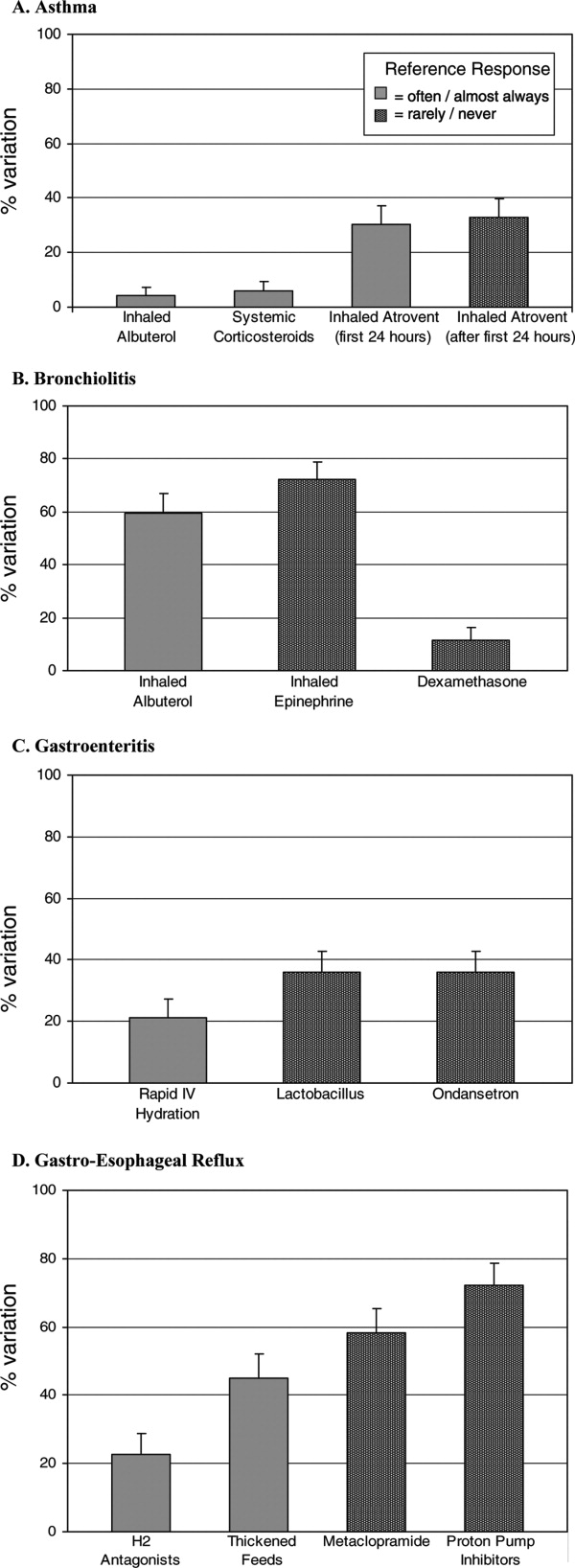

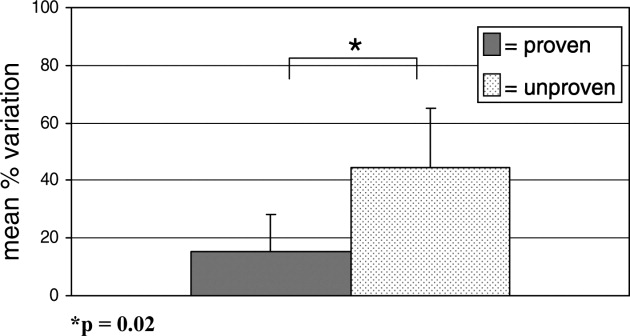

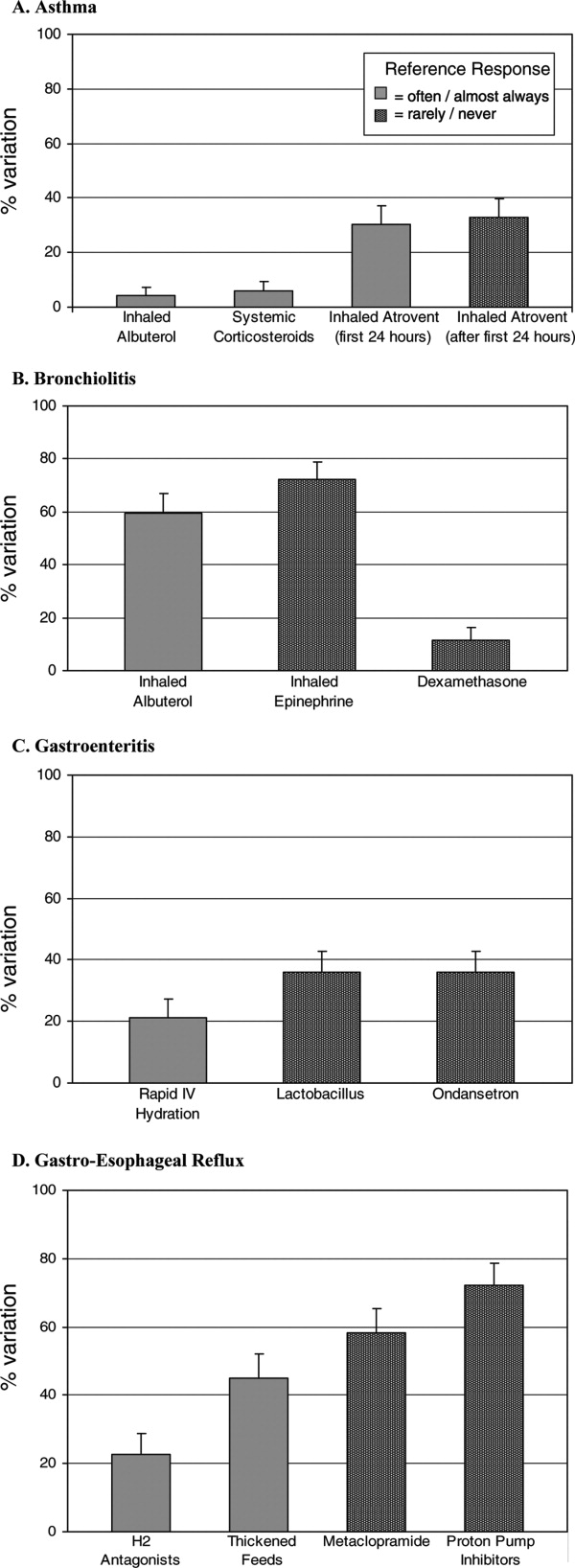

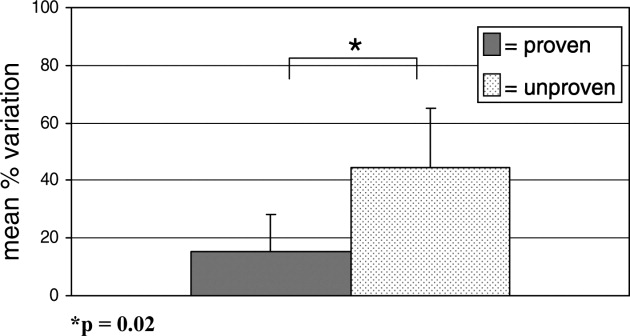

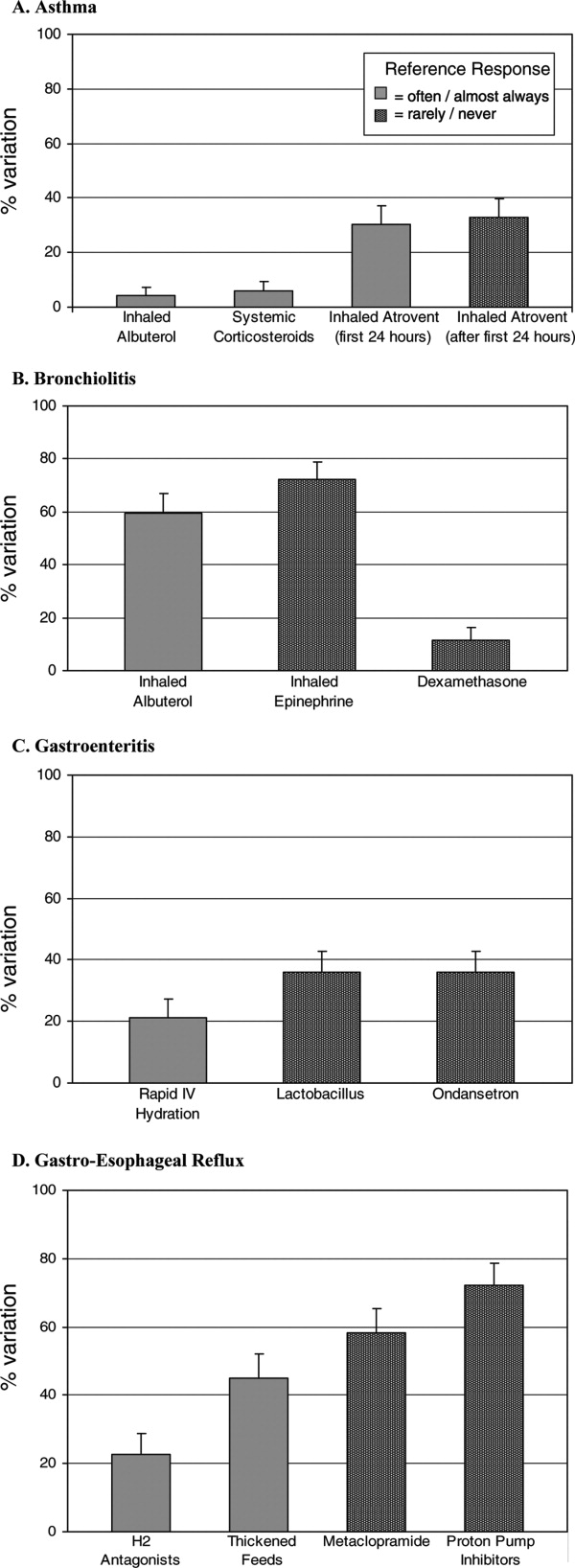

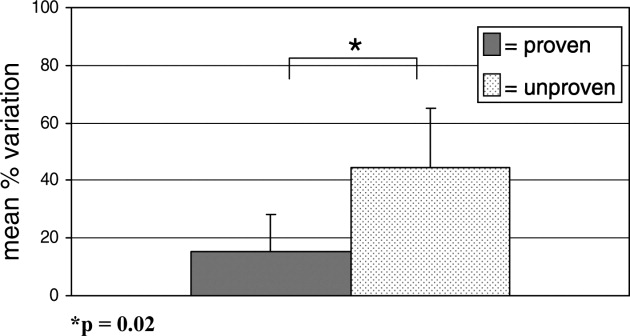

- , , , , .Variation in pediatric hospitalists' use of proven and unproven therapies: A study from the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network.J Hosp Med.2008;3(4):292–298.

- , , .Pediatric hospitalists: Training, current practice, and career goals.J Hosp Med.2009;4(3):179–186.

- , .Standardize to excellence: improving the quality and safety of care with clinical pathways.Pediatr Clin North Am.2009;56(4):893–904.

- .Evolution of a new specialty ‐ a twenty year pediatric hospitalist experience [Abstract]. In:National Association of Inpatient Physicians (now Society of Hospital Medicine).New Orleans, Louisiana;1999.

- , , , , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- , , , , e.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development.J Hosp Med.2006;1(Suppl 1).

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and answers regarding ABIM recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine through maintenance of certification. http://www.abim.org/news/news/focused‐practice‐hospital‐medicine‐qa.aspx. Published 2010. Accessed January 6,2010.

- .Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine.N Engl J Med.2008;358(21):2301–2302.

- The Joint Commission. Performance measurement initiatives. http://www. jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/. Published 2010. Accessed December 5,2010.

- The Joint Commission. Standards frequently asked questions: comprehensive accreditation manual for critical access hospitals (CAMCAH). http://www.jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/CriticalAccess Hospitals/Standards/09_FAQs/default.htm. Accessed December 5,2008; December 14, 2009.

- , , , , .Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States.Pediatrics.2008;121(2):244–252.

- , , , .Procedures in U.S. hospitals, 1997.HCUP fact book no. 2. In:agency for healthcare research and quality,Rockville, MD;2001.

- Anderson L, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, Mayer RE, Pintrich PR, et al., editors.A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. In: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Pearson Education USA;2001.

Introduction

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines hospitalists as physicians whose primary professional focus is the comprehensive general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to Hospital Medicine.1 It is estimated that there are up to 2500 pediatric hospitalists in the United States, with continued growth due to the converging needs for a dedicated focus on patient safety, quality improvement, hospital throughput, and inpatient teaching.2‐9 (Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM), as defined today, has been practiced in the United States for at least 30 years10 and continues to evolve as an area of specialization, with the refinement of a distinct knowledgebase and skill set focused on the provision of high quality general pediatric care in the inpatient setting. PHM is the latest site‐specific specialty to emerge from the field of general pediatrics it's development analogous to the evolution of critical care or emergency medicine during previous decades.11 Adult hospital medicine has defined itself within the field of general internal medicine12 and has recently received approval to provide a recognized focus of practice exam in 2010 for those re‐certifying with the American Board of Internal Medicine,13 PHM is creating an identity as a subspecialty practice with distinct focus on inpatient care for children within the larger context of general pediatric care.8, 14

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies were created to help define the roles and expectations for pediatric hospitalists, regardless of practice setting. The intent is to provide a unified approach toward identifying the specific body of knowledge and measurable skills needed to assure delivery of the highest quality of care for all hospitalized pediatric patients. Most children requiring hospitalization in the United States are hospitalized in community settings where subspecialty support is more limited and many pediatric services may be unavailable. Children with complex, chronic medical problems, however, are more likely to be hospitalized at a tertiary care or academic institutions. In order to unify pediatric hospitalists who work in different practice environments, the PHM Core Competencies were constructed to represent the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and systems improvements that all pediatric hospitalists can be expected to acquire and maintain.

Furthermore, the content of the PHM Core Competencies reflect the fact that children are a vulnerable population. Their care requires attention to many elements which distinguishes it from that given to the majority of the adult population: dependency, differences in developmental physiology and behavior, occurrence of congenital genetic disorders and age‐based clinical conditions, impact of chronic disease states on whole child development, and weight‐based medication dosing often with limited guidance from pediatric studies, to name a few. Awareness of these needs must be heightened when a child enters the hospital where diagnoses, procedures, and treatments often include use of high‐risk modalities and require coordination of care across multiple providers.

Pediatric hospitalists commonly work to improve the systems of care in which they operate and therefore both clinical and non‐clinical topics are included. The 54 chapters address the fundamental and most common components of inpatient care but are not an extensive review of all aspects of inpatient medicine encountered by those caring for hospitalized children. Finally, the PHM Core Competencies are not intended for use in assessing proficiency immediately post‐residency, but do provide a framework for the education and evaluation of both physicians‐in‐training and practicing hospitalists. Meeting these competencies is anticipated to take from one to three years of active practice in pediatric hospital medicine, and may be reached through a combination of practice experience, course work, self‐directed work, and/or formalized training.

Methods

Timeline

In 2002, SHM convened an educational summit from which there was a resolution to create core competencies. Following the summit, the SHM Pediatric Core Curriculum Task Force (CCTF) was created, which included 12 pediatric hospitalists practicing in academic and community facilities, as well as teaching and non‐teaching settings, and occupying leadership positions within institutions of varied size and geographic location. Shortly thereafter, in November 2003, approximately 130 pediatric hospitalists attended the first PHM meeting in San Antonio, Texas.11 At this meeting, with support from leaders in pediatric emergency medicine, first discussions regarding PHM scope of practice were held.

Formal development of the competencies began in 2005 in parallel to but distinct from SHM's adult work, which culminated in The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development published in 2006. The CCTF divided into three groups, focused on clinical, procedural, and systems‐based topics. Face‐to‐face meetings were held at the SHM annual meetings, with most work being completed by phone and electronically in the interim periods. In 2007, due to the overlapping interests of the three core pediatric societies, the work was transferred to leaders within the APA. In 2008 the work was transferred back to the leadership within SHM. Since that time, external reviewers were solicited, new chapters created, sections re‐aligned, internal and external reviewer comments incorporated, and final edits for taxonomy, content, and formatting were completed (Table 1).

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Feb 2002 | SHM Educational Summit held and CCTF created |

| Oct 2003 | 1st PHM meeting held in San Antonio |

| 2003‐2007 | Chapter focus determined; contributors engaged |

| 2007‐2008 | APA PHM Special Interest Group (SIG) review; creation of separate PHM Fellowship Competencies (not in this document) |

| Aug 2008‐Oct 2008 | SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF members resume work; editorial review |

| Oct 2008‐Mar 2009 | Internal review: PHM Fellowship Director, AAP, APA, and SHM section/committee leader, and key national PHM leader reviews solicited and returned |

| Mar 2009 | PHM Fellowship Director comments addressed; editorial review |

| Mar‐Apr 2009 | External reviewers solicited from national agencies and societies relevant to PHM |

| Apr‐July 2009 | External reviewer comments returned |

| July‐Oct 2009 | Contributor review of all comments; editorial review, sections revised |

| Oct 2009 | Final review: Chapters to SHM subcommittees and Board |

Areas of Focused Practice

The PHM Core Competencies were conceptualized similarly to the SHM adult core competencies. Initial sections were divided into clinical conditions, procedures, and systems. However as content developed and reviewer comments were addressed, the four final sections were modified to those noted in Table 2. For the Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions, the goal was to select conditions most commonly encountered by pediatric hospitalists. Non‐surgical diagnosis‐related group (DRG) conditions were selected from the following sources: The Joint Commission's (TJC) Oryx Performance Measures Report15‐16 (asthma, abdominal pain, acute gastroenteritis, simple pneumonia); Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System Dataset (CHCA PHIS, Shawnee Mission, KS), and relevant publications on common pediatric hospitalizations.17 These data were compared to billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing free‐standing children's and community hospitals, teaching and non‐teaching settings, and urban and rural locations. The 22 clinical conditions chosen by the CCTF were those most relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.

| Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions | Specialized Clinical Services | Core Skills | Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute abdominal pain and the acute abdomen | Neonatal fever | Child abuse and neglect | Bladder catheterization/suprapubic bladder tap | Advocacy |

| Apparent life‐threatening event | Neonatal jaundice | Hospice and palliative care | Electrocardiogram interpretation | Business practices |

| Asthma | Pneumonia | Leading a healthcare team | Feeding tubes | Communication |

| Bone and joint infections | Respiratory failure | Newborn care and delivery room management | Fluids and electrolyte management | Continuous quality improvement |

| Bronchiolitis | Seizures | Technology‐dependent children | Intravenous access and phlebotomy | Cost‐effective care |

| Central nervous system infections | Shock | Transport of the critically ill child | Lumbar puncture | Education |

| Diabetes mellitus | Sickle cell disease | Non‐invasive monitoring | Ethics | |

| Failure to thrive | Skin and soft tissue infection | Nutrition | Evidence‐based medicine | |

| Fever of unknown origin | Toxic ingestion | Oxygen delivery and airway management | Health information systems | |

| Gastroenteritis | Upper airway infections | Pain management | Legal issues/risk management | |

| Kawasaki disease | Urinary tract infections | Pediatric advanced life support | Patient safety |

The Specialized Clinical Servicessection addresses important components of care that are not DRG‐based and reflect the unique needs of hospitalized children, as assessed by the CCTF, editors, and contributors. Core Skillswere chosen based on the HCUP Factbook 2 Procedures,18 billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing the same settings listed above, and critical input from reviewers. Depending on the individual setting, pediatric hospitalists may require skills in areas not found in these 11 chapters, such as chest tube placement or ventilator management. The list is therefore not exhaustive, but rather representative of skills most pediatric hospitalists should maintain.

The Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Healthchapters are likely the most dissimilar to any core content taught in traditional residency programs. While residency graduates are versed in some components listed in these chapters, comprehensive education in most of these competencies is currently lacking. Improvement of healthcare systems is an essential element of pediatric hospital medicine, and unifies all pediatric hospitalists regardless of practice environment or patient population. Therefore, this section includes chapters that not only focus on systems of care, but also on advancing child health through advocacy, research, education, evidence‐based medicine, and ethical practice. These chapters were drawn from a combination of several sources: expectations of external agencies (TJC, Center for Medicaid and Medicare) related to the specific nonclinical work in which pediatric hospitalists are integrally involved; expectations for advocacy as best defined by the AAP and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI); the six core competency domains mandated by the Accrediting Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), and hospital medical staff offices as part of Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE) and Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE)16; and assessment of responsibilities and leadership roles fulfilled by pediatric hospitalists in all venues. In keeping with the intent of the competencies to be timeless, the competency elements call out the need to attend to the changing goals of these groups as well as those of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the Alliance for Pediatric Quality (which consists of ABP, AAP, TJC, CHCA, NACHRI), and local hospital systems leaders.

Contributors and Review

The CCTF selected section (associate) editors from SHM based on established expertise in each area, with input from the SHM Pediatric and Education Committees and the SHM Board. As a collaborative effort, authors for various chapters were solicited in consultation with experts from the AAP, APA, and SHM, and included non‐hospitalists with reputations as experts in various fields. Numerous SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF conference calls were held to review hospital and academic appointments, presentations given, and affiliations relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine. This vetting process resulted in a robust author list representing diverse geographic and practice settings. Contributors were provided with structure (Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Systems subsections) and content (timeless, competency based) guidelines.

The review process was rigorous, and included both internal and external reviewers. The APA review in 2007 included the PHM Special Interest Group as well as the PHM Fellowship Directors (Table 1). After return to SHM and further editing, the internal review commenced which focused on content and scope. The editors addressed the resulting suggestions and worked to standardize formatting and use of Bloom's taxonomy.19 A list of common terms and phrases were created to add consistency between chapters. External reviewers were first mailed a letter requesting interest, which was followed up by emails, letters, and phone calls to encourage feedback. External review included 29 solicited agencies and societies (Table 3), with overall response rate of 66% (41% for Groups I and II). Individual contributors then reviewed comments specific to their chapters, with associate editor overview of their respective sections. The editors reviewed each chapter individually multiple times throughout the 2007‐2009 years, contacting individual contributors and reviewers by email and phone. Editors concluded a final comprehensive review of all chapters in late 2009.

| I. Academic and certifying societies |

| Academic Pediatric Association |

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Pediatric Residency Review Committee |

| American Academy of Family Physicians |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Board |

| American Academy of Pediatrics National Committee on Hospital Care |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American Board of Family Medicine |

| American Board of Pediatrics |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Pediatric Society |

| Association of American Medical Colleges |

| Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs (AMSPDC) |

| Association of Pediatric Program Directors |

| Council on Teaching Hospitals |

| Society of Pediatric Research |

| II. Stakeholder agencies |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Hospital Association (AHA) |

| American Nurses Association |

| American Society of Health‐System Pharmacists |

| Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA) |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement |

| National Association for Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI) |

| National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) |

| National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) |

| National Quality Forum |

| Quality Resources International |

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

| The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Hospitals and Organizations (TJC) |

| III. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowship directors |

| Boston Children's |

| Children's Hospital Los Angeles |

| Children's National D.C. |

| Emory |

| Hospital for Sick Kids Toronto |

| Rady Children's San Diego University of California San Diego |

| Riley Children's Hospital Indiana |

| University of South Florida, All Children's Hospital |

| Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine |

| IV. SHM, APA, AAP Leadership and committee chairs |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine |

| Academic Pediatric Association PHM Special Interest Group |

| SHM Board |

| SHM Education Committee |

| SHM Family Practice Committee |

| SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee |

| SHM IT Task Force |

| SHM Journal Editorial Board |

| SHM Palliative Care Task Force |

| SHM Practice Analysis Committee |

| SHM Public Policy Committee |

| SHM Research Committee |

Chapter Content

Each of the 54 chapters within the four sections of these competencies is presented in the educational theory of learning domains: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, with a final Systems domain added to reflect the emphasis of hospitalist practice on improving healthcare systems. Each chapter is designed to stand alone, which may assist with development of curriculum at individual practice locations. Certain key phrases are apparent throughout, such as lead, coordinate, or participate in and work with hospital and community leaders to which were designed to note the varied roles in different practice settings. Some chapters specifically comment on the application of competency bullets given the unique and differing roles and expectations of pediatric hospitalists, such as research and education. Chapters state specific proficiencies expected wherever possible, with phrases and wording selected to help guide learning activities to achieve the competency.

Application and Future Directions

Although pediatric hospitalists care for children in many settings, these core competencies address the common expectations for any venue. Pediatric hospital medicine requires skills in acute care clinical medicine that attend to the changing needs of hospitalized children. The core of pediatric hospital medicine is dedicated to the care of children in the geographic hospital environment between emergency medicine and tertiary pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Pediatric hospitalists provide care in related clinical service programs that are linked to hospital systems. In performing these activities, pediatric hospitalists consistently partner with ambulatory providers and subspecialists to render coordinated care across the continuum for a given child. Pediatric hospital medicine is an interdisciplinary practice, with focus on processes of care and clinical quality outcomes based in evidence. Engagement in local, state, and national initiatives to improve child health outcomes is a cornerstone of pediatric hospitalists' practice. These competencies provide the framework for creation of curricula that can reflect local issues and react to changing evidence.

As providers of systems‐based care, pediatric hospitalists are called upon more and more to render care and provide leadership in clinical arenas that are integral to healthcare organizations, such as home health care, sub‐acute care facilities, and hospice and palliative care programs. The practice of pediatric hospital medicine has evolved to its current state through efforts of many represented in the competencies as contributors, associate editors, editors, and reviewers. Pediatric hospitalists are committed to leading change in healthcare for hospitalized children, and are positioned well to address the interests and needs of community and urban, teaching and non‐teaching facilities, and the children and families they serve. These competencies reflect the areas of focused practice which, similar to pediatric emergency medicine, will no doubt be refined but not fundamentally changed in future years. The intent, we hope, is clear: to provide excellence in clinical care, accountability for practice, and lead improvements in healthcare for hospitalized children.

Introduction

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines hospitalists as physicians whose primary professional focus is the comprehensive general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to Hospital Medicine.1 It is estimated that there are up to 2500 pediatric hospitalists in the United States, with continued growth due to the converging needs for a dedicated focus on patient safety, quality improvement, hospital throughput, and inpatient teaching.2‐9 (Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM), as defined today, has been practiced in the United States for at least 30 years10 and continues to evolve as an area of specialization, with the refinement of a distinct knowledgebase and skill set focused on the provision of high quality general pediatric care in the inpatient setting. PHM is the latest site‐specific specialty to emerge from the field of general pediatrics it's development analogous to the evolution of critical care or emergency medicine during previous decades.11 Adult hospital medicine has defined itself within the field of general internal medicine12 and has recently received approval to provide a recognized focus of practice exam in 2010 for those re‐certifying with the American Board of Internal Medicine,13 PHM is creating an identity as a subspecialty practice with distinct focus on inpatient care for children within the larger context of general pediatric care.8, 14

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies were created to help define the roles and expectations for pediatric hospitalists, regardless of practice setting. The intent is to provide a unified approach toward identifying the specific body of knowledge and measurable skills needed to assure delivery of the highest quality of care for all hospitalized pediatric patients. Most children requiring hospitalization in the United States are hospitalized in community settings where subspecialty support is more limited and many pediatric services may be unavailable. Children with complex, chronic medical problems, however, are more likely to be hospitalized at a tertiary care or academic institutions. In order to unify pediatric hospitalists who work in different practice environments, the PHM Core Competencies were constructed to represent the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and systems improvements that all pediatric hospitalists can be expected to acquire and maintain.

Furthermore, the content of the PHM Core Competencies reflect the fact that children are a vulnerable population. Their care requires attention to many elements which distinguishes it from that given to the majority of the adult population: dependency, differences in developmental physiology and behavior, occurrence of congenital genetic disorders and age‐based clinical conditions, impact of chronic disease states on whole child development, and weight‐based medication dosing often with limited guidance from pediatric studies, to name a few. Awareness of these needs must be heightened when a child enters the hospital where diagnoses, procedures, and treatments often include use of high‐risk modalities and require coordination of care across multiple providers.

Pediatric hospitalists commonly work to improve the systems of care in which they operate and therefore both clinical and non‐clinical topics are included. The 54 chapters address the fundamental and most common components of inpatient care but are not an extensive review of all aspects of inpatient medicine encountered by those caring for hospitalized children. Finally, the PHM Core Competencies are not intended for use in assessing proficiency immediately post‐residency, but do provide a framework for the education and evaluation of both physicians‐in‐training and practicing hospitalists. Meeting these competencies is anticipated to take from one to three years of active practice in pediatric hospital medicine, and may be reached through a combination of practice experience, course work, self‐directed work, and/or formalized training.

Methods

Timeline

In 2002, SHM convened an educational summit from which there was a resolution to create core competencies. Following the summit, the SHM Pediatric Core Curriculum Task Force (CCTF) was created, which included 12 pediatric hospitalists practicing in academic and community facilities, as well as teaching and non‐teaching settings, and occupying leadership positions within institutions of varied size and geographic location. Shortly thereafter, in November 2003, approximately 130 pediatric hospitalists attended the first PHM meeting in San Antonio, Texas.11 At this meeting, with support from leaders in pediatric emergency medicine, first discussions regarding PHM scope of practice were held.

Formal development of the competencies began in 2005 in parallel to but distinct from SHM's adult work, which culminated in The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development published in 2006. The CCTF divided into three groups, focused on clinical, procedural, and systems‐based topics. Face‐to‐face meetings were held at the SHM annual meetings, with most work being completed by phone and electronically in the interim periods. In 2007, due to the overlapping interests of the three core pediatric societies, the work was transferred to leaders within the APA. In 2008 the work was transferred back to the leadership within SHM. Since that time, external reviewers were solicited, new chapters created, sections re‐aligned, internal and external reviewer comments incorporated, and final edits for taxonomy, content, and formatting were completed (Table 1).

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Feb 2002 | SHM Educational Summit held and CCTF created |

| Oct 2003 | 1st PHM meeting held in San Antonio |

| 2003‐2007 | Chapter focus determined; contributors engaged |

| 2007‐2008 | APA PHM Special Interest Group (SIG) review; creation of separate PHM Fellowship Competencies (not in this document) |

| Aug 2008‐Oct 2008 | SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF members resume work; editorial review |

| Oct 2008‐Mar 2009 | Internal review: PHM Fellowship Director, AAP, APA, and SHM section/committee leader, and key national PHM leader reviews solicited and returned |

| Mar 2009 | PHM Fellowship Director comments addressed; editorial review |

| Mar‐Apr 2009 | External reviewers solicited from national agencies and societies relevant to PHM |

| Apr‐July 2009 | External reviewer comments returned |

| July‐Oct 2009 | Contributor review of all comments; editorial review, sections revised |

| Oct 2009 | Final review: Chapters to SHM subcommittees and Board |

Areas of Focused Practice

The PHM Core Competencies were conceptualized similarly to the SHM adult core competencies. Initial sections were divided into clinical conditions, procedures, and systems. However as content developed and reviewer comments were addressed, the four final sections were modified to those noted in Table 2. For the Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions, the goal was to select conditions most commonly encountered by pediatric hospitalists. Non‐surgical diagnosis‐related group (DRG) conditions were selected from the following sources: The Joint Commission's (TJC) Oryx Performance Measures Report15‐16 (asthma, abdominal pain, acute gastroenteritis, simple pneumonia); Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System Dataset (CHCA PHIS, Shawnee Mission, KS), and relevant publications on common pediatric hospitalizations.17 These data were compared to billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing free‐standing children's and community hospitals, teaching and non‐teaching settings, and urban and rural locations. The 22 clinical conditions chosen by the CCTF were those most relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.

| Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions | Specialized Clinical Services | Core Skills | Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute abdominal pain and the acute abdomen | Neonatal fever | Child abuse and neglect | Bladder catheterization/suprapubic bladder tap | Advocacy |

| Apparent life‐threatening event | Neonatal jaundice | Hospice and palliative care | Electrocardiogram interpretation | Business practices |

| Asthma | Pneumonia | Leading a healthcare team | Feeding tubes | Communication |

| Bone and joint infections | Respiratory failure | Newborn care and delivery room management | Fluids and electrolyte management | Continuous quality improvement |

| Bronchiolitis | Seizures | Technology‐dependent children | Intravenous access and phlebotomy | Cost‐effective care |

| Central nervous system infections | Shock | Transport of the critically ill child | Lumbar puncture | Education |

| Diabetes mellitus | Sickle cell disease | Non‐invasive monitoring | Ethics | |

| Failure to thrive | Skin and soft tissue infection | Nutrition | Evidence‐based medicine | |

| Fever of unknown origin | Toxic ingestion | Oxygen delivery and airway management | Health information systems | |

| Gastroenteritis | Upper airway infections | Pain management | Legal issues/risk management | |

| Kawasaki disease | Urinary tract infections | Pediatric advanced life support | Patient safety |

The Specialized Clinical Servicessection addresses important components of care that are not DRG‐based and reflect the unique needs of hospitalized children, as assessed by the CCTF, editors, and contributors. Core Skillswere chosen based on the HCUP Factbook 2 Procedures,18 billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing the same settings listed above, and critical input from reviewers. Depending on the individual setting, pediatric hospitalists may require skills in areas not found in these 11 chapters, such as chest tube placement or ventilator management. The list is therefore not exhaustive, but rather representative of skills most pediatric hospitalists should maintain.

The Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Healthchapters are likely the most dissimilar to any core content taught in traditional residency programs. While residency graduates are versed in some components listed in these chapters, comprehensive education in most of these competencies is currently lacking. Improvement of healthcare systems is an essential element of pediatric hospital medicine, and unifies all pediatric hospitalists regardless of practice environment or patient population. Therefore, this section includes chapters that not only focus on systems of care, but also on advancing child health through advocacy, research, education, evidence‐based medicine, and ethical practice. These chapters were drawn from a combination of several sources: expectations of external agencies (TJC, Center for Medicaid and Medicare) related to the specific nonclinical work in which pediatric hospitalists are integrally involved; expectations for advocacy as best defined by the AAP and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI); the six core competency domains mandated by the Accrediting Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), and hospital medical staff offices as part of Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE) and Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE)16; and assessment of responsibilities and leadership roles fulfilled by pediatric hospitalists in all venues. In keeping with the intent of the competencies to be timeless, the competency elements call out the need to attend to the changing goals of these groups as well as those of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the Alliance for Pediatric Quality (which consists of ABP, AAP, TJC, CHCA, NACHRI), and local hospital systems leaders.

Contributors and Review

The CCTF selected section (associate) editors from SHM based on established expertise in each area, with input from the SHM Pediatric and Education Committees and the SHM Board. As a collaborative effort, authors for various chapters were solicited in consultation with experts from the AAP, APA, and SHM, and included non‐hospitalists with reputations as experts in various fields. Numerous SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF conference calls were held to review hospital and academic appointments, presentations given, and affiliations relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine. This vetting process resulted in a robust author list representing diverse geographic and practice settings. Contributors were provided with structure (Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Systems subsections) and content (timeless, competency based) guidelines.

The review process was rigorous, and included both internal and external reviewers. The APA review in 2007 included the PHM Special Interest Group as well as the PHM Fellowship Directors (Table 1). After return to SHM and further editing, the internal review commenced which focused on content and scope. The editors addressed the resulting suggestions and worked to standardize formatting and use of Bloom's taxonomy.19 A list of common terms and phrases were created to add consistency between chapters. External reviewers were first mailed a letter requesting interest, which was followed up by emails, letters, and phone calls to encourage feedback. External review included 29 solicited agencies and societies (Table 3), with overall response rate of 66% (41% for Groups I and II). Individual contributors then reviewed comments specific to their chapters, with associate editor overview of their respective sections. The editors reviewed each chapter individually multiple times throughout the 2007‐2009 years, contacting individual contributors and reviewers by email and phone. Editors concluded a final comprehensive review of all chapters in late 2009.

| I. Academic and certifying societies |

| Academic Pediatric Association |

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Pediatric Residency Review Committee |

| American Academy of Family Physicians |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Board |

| American Academy of Pediatrics National Committee on Hospital Care |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American Board of Family Medicine |

| American Board of Pediatrics |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Pediatric Society |

| Association of American Medical Colleges |

| Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs (AMSPDC) |

| Association of Pediatric Program Directors |

| Council on Teaching Hospitals |

| Society of Pediatric Research |

| II. Stakeholder agencies |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| American Association of Critical Care Nursing |

| American College of Emergency Physicians |

| American Hospital Association (AHA) |

| American Nurses Association |

| American Society of Health‐System Pharmacists |

| Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA) |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement |

| National Association for Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI) |

| National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) |

| National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) |

| National Quality Forum |

| Quality Resources International |

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

| The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Hospitals and Organizations (TJC) |

| III. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowship directors |

| Boston Children's |

| Children's Hospital Los Angeles |

| Children's National D.C. |

| Emory |

| Hospital for Sick Kids Toronto |

| Rady Children's San Diego University of California San Diego |

| Riley Children's Hospital Indiana |

| University of South Florida, All Children's Hospital |

| Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine |

| IV. SHM, APA, AAP Leadership and committee chairs |

| American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine |

| Academic Pediatric Association PHM Special Interest Group |

| SHM Board |

| SHM Education Committee |

| SHM Family Practice Committee |

| SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee |

| SHM IT Task Force |

| SHM Journal Editorial Board |

| SHM Palliative Care Task Force |

| SHM Practice Analysis Committee |

| SHM Public Policy Committee |

| SHM Research Committee |

Chapter Content

Each of the 54 chapters within the four sections of these competencies is presented in the educational theory of learning domains: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, with a final Systems domain added to reflect the emphasis of hospitalist practice on improving healthcare systems. Each chapter is designed to stand alone, which may assist with development of curriculum at individual practice locations. Certain key phrases are apparent throughout, such as lead, coordinate, or participate in and work with hospital and community leaders to which were designed to note the varied roles in different practice settings. Some chapters specifically comment on the application of competency bullets given the unique and differing roles and expectations of pediatric hospitalists, such as research and education. Chapters state specific proficiencies expected wherever possible, with phrases and wording selected to help guide learning activities to achieve the competency.

Application and Future Directions

Although pediatric hospitalists care for children in many settings, these core competencies address the common expectations for any venue. Pediatric hospital medicine requires skills in acute care clinical medicine that attend to the changing needs of hospitalized children. The core of pediatric hospital medicine is dedicated to the care of children in the geographic hospital environment between emergency medicine and tertiary pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Pediatric hospitalists provide care in related clinical service programs that are linked to hospital systems. In performing these activities, pediatric hospitalists consistently partner with ambulatory providers and subspecialists to render coordinated care across the continuum for a given child. Pediatric hospital medicine is an interdisciplinary practice, with focus on processes of care and clinical quality outcomes based in evidence. Engagement in local, state, and national initiatives to improve child health outcomes is a cornerstone of pediatric hospitalists' practice. These competencies provide the framework for creation of curricula that can reflect local issues and react to changing evidence.

As providers of systems‐based care, pediatric hospitalists are called upon more and more to render care and provide leadership in clinical arenas that are integral to healthcare organizations, such as home health care, sub‐acute care facilities, and hospice and palliative care programs. The practice of pediatric hospital medicine has evolved to its current state through efforts of many represented in the competencies as contributors, associate editors, editors, and reviewers. Pediatric hospitalists are committed to leading change in healthcare for hospitalized children, and are positioned well to address the interests and needs of community and urban, teaching and non‐teaching facilities, and the children and families they serve. These competencies reflect the areas of focused practice which, similar to pediatric emergency medicine, will no doubt be refined but not fundamentally changed in future years. The intent, we hope, is clear: to provide excellence in clinical care, accountability for practice, and lead improvements in healthcare for hospitalized children.

- Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). Definition of a Hospitalist. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=General_Information 2009.

- .Pediatric Hospitalists Membership Numbers. In.Philadelphia:Society of Hospital Medicine, PA 19130;2009.

- , .The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?.Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- , .The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- , , , , .Variation in pediatric hospitalists' use of proven and unproven therapies: A study from the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network.J Hosp Med.2008;3(4):292–298.

- , , .Pediatric hospitalists: Training, current practice, and career goals.J Hosp Med.2009;4(3):179–186.

- , .Standardize to excellence: improving the quality and safety of care with clinical pathways.Pediatr Clin North Am.2009;56(4):893–904.

- .Evolution of a new specialty ‐ a twenty year pediatric hospitalist experience [Abstract]. In:National Association of Inpatient Physicians (now Society of Hospital Medicine).New Orleans, Louisiana;1999.

- , , , , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- , , , , e.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development.J Hosp Med.2006;1(Suppl 1).

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and answers regarding ABIM recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine through maintenance of certification. http://www.abim.org/news/news/focused‐practice‐hospital‐medicine‐qa.aspx. Published 2010. Accessed January 6,2010.

- .Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine.N Engl J Med.2008;358(21):2301–2302.

- The Joint Commission. Performance measurement initiatives. http://www. jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/. Published 2010. Accessed December 5,2010.

- The Joint Commission. Standards frequently asked questions: comprehensive accreditation manual for critical access hospitals (CAMCAH). http://www.jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/CriticalAccess Hospitals/Standards/09_FAQs/default.htm. Accessed December 5,2008; December 14, 2009.

- , , , , .Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States.Pediatrics.2008;121(2):244–252.

- , , , .Procedures in U.S. hospitals, 1997.HCUP fact book no. 2. In:agency for healthcare research and quality,Rockville, MD;2001.

- Anderson L, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, Mayer RE, Pintrich PR, et al., editors.A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. In: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Pearson Education USA;2001.

- Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). Definition of a Hospitalist. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=General_Information 2009.

- .Pediatric Hospitalists Membership Numbers. In.Philadelphia:Society of Hospital Medicine, PA 19130;2009.

- , .The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?.Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- , .The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- , , , , .Variation in pediatric hospitalists' use of proven and unproven therapies: A study from the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network.J Hosp Med.2008;3(4):292–298.

- , , .Pediatric hospitalists: Training, current practice, and career goals.J Hosp Med.2009;4(3):179–186.

- , .Standardize to excellence: improving the quality and safety of care with clinical pathways.Pediatr Clin North Am.2009;56(4):893–904.

- .Evolution of a new specialty ‐ a twenty year pediatric hospitalist experience [Abstract]. In:National Association of Inpatient Physicians (now Society of Hospital Medicine).New Orleans, Louisiana;1999.

- , , , , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- , , , , e.The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development.J Hosp Med.2006;1(Suppl 1).

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and answers regarding ABIM recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine through maintenance of certification. http://www.abim.org/news/news/focused‐practice‐hospital‐medicine‐qa.aspx. Published 2010. Accessed January 6,2010.

- .Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine.N Engl J Med.2008;358(21):2301–2302.

- The Joint Commission. Performance measurement initiatives. http://www. jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/. Published 2010. Accessed December 5,2010.

- The Joint Commission. Standards frequently asked questions: comprehensive accreditation manual for critical access hospitals (CAMCAH). http://www.jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/CriticalAccess Hospitals/Standards/09_FAQs/default.htm. Accessed December 5,2008; December 14, 2009.

- , , , , .Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States.Pediatrics.2008;121(2):244–252.

- , , , .Procedures in U.S. hospitals, 1997.HCUP fact book no. 2. In:agency for healthcare research and quality,Rockville, MD;2001.

- Anderson L, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, Mayer RE, Pintrich PR, et al., editors.A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. In: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Pearson Education USA;2001.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies

Introduction

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines hospitalists as physicians whose primary professional focus is the comprehensive general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to Hospital Medicine.1 It is estimated that there are up to 2500 pediatric hospitalists in the United States, with continued growth due to the converging needs for a dedicated focus on patient safety, quality improvement, hospital throughput, and inpatient teaching.2‐9 (Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM), as defined today, has been practiced in the United States for at least 30 years10 and continues to evolve as an area of specialization, with the refinement of a distinct knowledgebase and skill set focused on the provision of high quality general pediatric care in the inpatient setting. PHM is the latest site‐specific specialty to emerge from the field of general pediatrics it's development analogous to the evolution of critical care or emergency medicine during previous decades.11 Adult hospital medicine has defined itself within the field of general internal medicine12 and has recently received approval to provide a recognized focus of practice exam in 2010 for those re‐certifying with the American Board of Internal Medicine,13 PHM is creating an identity as a subspecialty practice with distinct focus on inpatient care for children within the larger context of general pediatric care.8, 14

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies were created to help define the roles and expectations for pediatric hospitalists, regardless of practice setting. The intent is to provide a unified approach toward identifying the specific body of knowledge and measurable skills needed to assure delivery of the highest quality of care for all hospitalized pediatric patients. Most children requiring hospitalization in the United States are hospitalized in community settings where subspecialty support is more limited and many pediatric services may be unavailable. Children with complex, chronic medical problems, however, are more likely to be hospitalized at a tertiary care or academic institutions. In order to unify pediatric hospitalists who work in different practice environments, the PHM Core Competencies were constructed to represent the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and systems improvements that all pediatric hospitalists can be expected to acquire and maintain.

Furthermore, the content of the PHM Core Competencies reflect the fact that children are a vulnerable population. Their care requires attention to many elements which distinguishes it from that given to the majority of the adult population: dependency, differences in developmental physiology and behavior, occurrence of congenital genetic disorders and age‐based clinical conditions, impact of chronic disease states on whole child development, and weight‐based medication dosing often with limited guidance from pediatric studies, to name a few. Awareness of these needs must be heightened when a child enters the hospital where diagnoses, procedures, and treatments often include use of high‐risk modalities and require coordination of care across multiple providers.

Pediatric hospitalists commonly work to improve the systems of care in which they operate and therefore both clinical and non‐clinical topics are included. The 54 chapters address the fundamental and most common components of inpatient care but are not an extensive review of all aspects of inpatient medicine encountered by those caring for hospitalized children. Finally, the PHM Core Competencies are not intended for use in assessing proficiency immediately post‐residency, but do provide a framework for the education and evaluation of both physicians‐in‐training and practicing hospitalists. Meeting these competencies is anticipated to take from one to three years of active practice in pediatric hospital medicine, and may be reached through a combination of practice experience, course work, self‐directed work, and/or formalized training.

Methods

Timeline

In 2002, SHM convened an educational summit from which there was a resolution to create core competencies. Following the summit, the SHM Pediatric Core Curriculum Task Force (CCTF) was created, which included 12 pediatric hospitalists practicing in academic and community facilities, as well as teaching and non‐teaching settings, and occupying leadership positions within institutions of varied size and geographic location. Shortly thereafter, in November 2003, approximately 130 pediatric hospitalists attended the first PHM meeting in San Antonio, Texas.11 At this meeting, with support from leaders in pediatric emergency medicine, first discussions regarding PHM scope of practice were held.

Formal development of the competencies began in 2005 in parallel to but distinct from SHM's adult work, which culminated in The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development published in 2006. The CCTF divided into three groups, focused on clinical, procedural, and systems‐based topics. Face‐to‐face meetings were held at the SHM annual meetings, with most work being completed by phone and electronically in the interim periods. In 2007, due to the overlapping interests of the three core pediatric societies, the work was transferred to leaders within the APA. In 2008 the work was transferred back to the leadership within SHM. Since that time, external reviewers were solicited, new chapters created, sections re‐aligned, internal and external reviewer comments incorporated, and final edits for taxonomy, content, and formatting were completed (Table 1).

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Feb 2002 | SHM Educational Summit held and CCTF created |

| Oct 2003 | 1st PHM meeting held in San Antonio |

| 2003‐2007 | Chapter focus determined; contributors engaged |

| 2007‐2008 | APA PHM Special Interest Group (SIG) review; creation of separate PHM Fellowship Competencies (not in this document) |

| Aug 2008‐Oct 2008 | SHM Pediatric Committee and CCTF members resume work; editorial review |

| Oct 2008‐Mar 2009 | Internal review: PHM Fellowship Director, AAP, APA, and SHM section/committee leader, and key national PHM leader reviews solicited and returned |

| Mar 2009 | PHM Fellowship Director comments addressed; editorial review |

| Mar‐Apr 2009 | External reviewers solicited from national agencies and societies relevant to PHM |

| Apr‐July 2009 | External reviewer comments returned |

| July‐Oct 2009 | Contributor review of all comments; editorial review, sections revised |

| Oct 2009 | Final review: Chapters to SHM subcommittees and Board |

Areas of Focused Practice

The PHM Core Competencies were conceptualized similarly to the SHM adult core competencies. Initial sections were divided into clinical conditions, procedures, and systems. However as content developed and reviewer comments were addressed, the four final sections were modified to those noted in Table 2. For the Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions, the goal was to select conditions most commonly encountered by pediatric hospitalists. Non‐surgical diagnosis‐related group (DRG) conditions were selected from the following sources: The Joint Commission's (TJC) Oryx Performance Measures Report15‐16 (asthma, abdominal pain, acute gastroenteritis, simple pneumonia); Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System Dataset (CHCA PHIS, Shawnee Mission, KS), and relevant publications on common pediatric hospitalizations.17 These data were compared to billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing free‐standing children's and community hospitals, teaching and non‐teaching settings, and urban and rural locations. The 22 clinical conditions chosen by the CCTF were those most relevant to the practice of pediatric hospital medicine.

| Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions | Specialized Clinical Services | Core Skills | Healthcare Systems: Supporting and Advancing Child Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute abdominal pain and the acute abdomen | Neonatal fever | Child abuse and neglect | Bladder catheterization/suprapubic bladder tap | Advocacy |

| Apparent life‐threatening event | Neonatal Jaundice | Hospice and palliative care | Electrocardiogram interpretation | Business practices |

| Asthma | Pneumonia | Leading a healthcare team | Feeding Tubes | Communication |

| Bone and joint infections | Respiratory Failure | Newborn care and delivery room management | Fluids and Electrolyte Management | Continuous quality improvement |

| Bronchiolitis | Seizures | Technology dependent children | Intravenous access and phlebotomy | Cost‐effective care |

| Central nervous system infections | Shock | Transport of the critically ill child | Lumbar puncture | Education |

| Diabetes mellitus | Sickle cell disease | Non‐invasive monitoring | Ethics | |

| Failure to thrive | Skin and soft tissue infection | Nutrition | Evidence based medicine | |

| Fever of unknown origin | Toxic ingestion | Oxygen delivery and airway management | Health Information Systems | |

| Gastroenteritis | Upper airway infections | Pain management | Legal issues/risk management | |

| Kawasaki disease | Urinary Tract infections | Pediatric Advanced Life Support | Patient safety |

The Specialized Clinical Servicessection addresses important components of care that are not DRG‐based and reflect the unique needs of hospitalized children, as assessed by the CCTF, editors, and contributors. Core Skillswere chosen based on the HCUP Factbook 2 Procedures,18 billing data from randomly‐selected practicing hospitalists representing the same settings listed above, and critical input from reviewers. Depending on the individual setting, pediatric hospitalists may require skills in areas not found in these 11 chapters, such as chest tube placement or ventilator management. The list is therefore not exhaustive, but rather representative of skills most pediatric hospitalists should maintain.