User login

Hospitalist’s regulatory roundup: Medicare penalties adding up for doctors, hospitals

October marks the start of a new fiscal year for the federal government and with it comes a host of new and revised regulatory requirements for hospitalists and hospitals.

Medicare officials are using some carrots – but mostly sticks – to get hospitals and doctors to improve quality and lower costs. Some of the programs levy financial penalties on hospitals but affect the day-to-day work of hospitalists, while others affect physicians at the individual level.

"There’s a lot of confusion and lack of knowledge about what’s occurring at the physician level and what’s occurring at the hospital level," said Dr. Patrick J. Torcson, a member of the board of directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Carrots, sticks for hospitalists

Two programs will touch hospitalists – and their wallets – directly. Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), a voluntary pay-for-reporting program, has been around since 2007 offering small incentives for participation, but it will soon begin penalizing physicians who don’t report on quality. Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are also phasing in the physician value-based modifier, which will begin adjusting physician payments up or down depending on the quality and cost of the care they provide.

CMS will use PQRS reporting as the basis for the new modifier, making participation in the older program a top priority for all physicians, Dr. Torcson said.

This year, physicians who successfully report quality measures through PQRS can earn a 0.5% bonus on their total allowable Medicare Part B charges. The same bonus will be in place for 2014. But starting in 2015, Medicare will assess a 1.5% penalty on physicians who fail to report successfully. That payment penalty increases to 2% in 2016.

But the PQRS has been criticized as being cumbersome and not especially relevant for hospitalists.

"I think many physicians hoped it would go away," Dr. Torcson said. "It hasn’t. It has expanded."

Hospitalists are currently required to report on at least three quality measures through the program. But Medicare is proposing to require physicians to report on at least nine measures starting in 2014. CMS will issue a final regulation outlining changes to the PQRS in November.

The SHM has recommended instead that CMS limit the expansion to no more than six quality measures to keep from ramping up the program too fast.

In comments to the agency, SHM also noted that the PQRS quality measures, while improving, still do not accurately reflect the scope of care provided by hospitalists. For instance, about half of the measures that hospitalists can report on are related to stroke care, though stoke care is not a primary practice focus for many hospital medicine programs.

Many hospitalists have ignored the PQRS so far, Dr. Torcson said, because the added time and effort of reporting on quality measures outweighed the value of the 0.5% bonus, on average about $500 per physician. But he urged physicians to rethink participation in light of the rollout of the new value-based modifier program.

Value-based modifier coming soon

The physician value-based payment modifier was part of the 2008 Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act and was expanded as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The program seeks to pay physicians more for providing high-quality, low-cost care. But the budget-neutral program will pay less for low-quality, high-cost care. Physician groups could see payment cuts of between 1% and 2% in 2016, based on their performance. Physicians who don’t report on quality measures through the PQRS will get an automatic 1% pay cut under the value-based modifier program.

The value-based modifier already is affecting physicians who work in groups of 100 or more eligible providers. While payments won’t be affected until 2015, CMS will base its adjustments on the data reported to the PQRS in 2013. The program will expand to cover physician groups of 10 or more in 2016, though the measurement on cost and quality will occur in 2014. Payments for all physicians will be subject to the modifier by 2017, based on performance during 2015.

"Physician-level pay for reporting is well underway and now actual pay for performance is here," Dr. Torcson said. "Engagement, familiarity, and participation in the PQRS is really going to be the key for physicians. It’s not too late."

CMS is providing some tools to help physicians understand their performance on cost and quality. The agency is producing annual Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs) that will show the individual physician’s past performance on the measures chosen by CMS. The reports are scheduled to go out to groups of 25 or more eligible professionals this fall. All physicians should start receiving the reports sometime in 2014.

But hospitalists should look closely at their reports, Dr. Torcson said. CMS is still figuring out how to classify the work done by hospitalists. Currently, CMS compares hospitalists’ cost and quality data to general internists even though hospitalized patients have a very different quality and cost profile.

"That’s something where there are still ongoing focused advocacy efforts by SHM to make sure that the attribution and the measurement methodology takes into account the hospitalist model," he said.

Hospitals under pressure, too

But hospitalists have more them just themselves to worry about. Often it’s the hospitalist who is the point person for quality and efficiency in their institution. And Medicare has an array of hospital-focused carrots and sticks, as well.

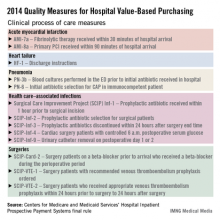

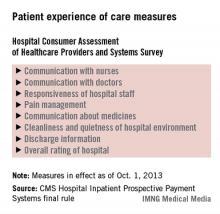

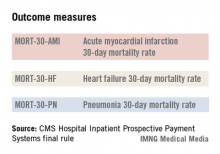

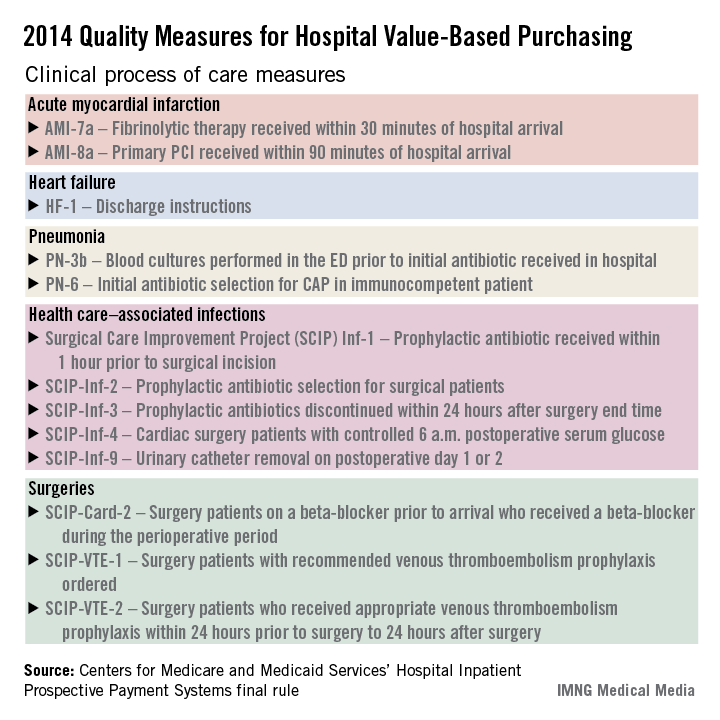

The hospital value-based purchasing program is already in full swing. For fiscal year 2014, which begins in October 2013, hospitals will have 1.25% of their base operating charges at risk in the program. The program bases payment on a group of clinical process measures, patient satisfaction, and selected mortality measures.

Additionally, Medicare is doubling the maximum penalties for its from 1% to 2% of base operating payments starting this month. The penalties apply to hospitals that have excess 30-day readmissions for pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. CMS is also expected to add more conditions to the list. Total hip and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease will be added to the list of conditions in October 2014.

CMS is also launching a new Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program in October 2014. In this program, which was authorized under the Affordable Care Act, hospitals with the most HACs will see their payments reduced by 1%. During the first year, hospitals will be judged based on several indicators including:

• Pressure ulcer rate.

• Iatrogenic pneumothorax rate.

• Central venous catheter–related blood stream infection rate.

• Postoperative hip fracture rate.

• Postoperative pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis rate.

• Postoperative sepsis rate.

• Wound dehiscence rate.

• Accidental puncture and laceration rate.

• Central line–associated blood stream infection.

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infection.

• Hospitals’ scores will be risk adjusted based on age, sex, and comorbidities.

More regulatory changes

CMS is also making some changes that will impact how hospitalists admit patients. Over the summer, Medicare officials issued a regulation that changes the criteria for when to admit a patient to hospital, as covered under Medicare Part A, and when to place them under observation status under Part B. The new criteria are based on the amount of time the physician expects the patient to spend as an inpatient.

Starting on Oct. 1, 2013, Medicare contractors will assume that a hospital stay is covered under Part A if the physician expects the patient to stay as an inpatient in the hospital for at least 2 midnights. CMS also emphasized in the rule that the inpatient stay does not begin until the patient is formally admitted by a physician.

What can hospitalists do to prepare?

While new regulatory requirements continue to hit hospitals year after year, Dr. Torcson said hospitalists are well prepared to handle the changes.

"The whole purpose and success and value of hospitalists is being the physician champions for the hospital-level performance agenda around core measures, readmissions, hospital-acquired conditions, and medical necessity documentation," he said. "That’s something that hospitalists have been preparing for from day 1, going back to the ’90s."

He urged hospitalists to redouble their efforts as hospital champions for quality.

"Concentrating on the hospital-level performance agenda is really going to be the key for hospital medicine programs to continue to be successful," Dr. Torcson said.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

October marks the start of a new fiscal year for the federal government and with it comes a host of new and revised regulatory requirements for hospitalists and hospitals.

Medicare officials are using some carrots – but mostly sticks – to get hospitals and doctors to improve quality and lower costs. Some of the programs levy financial penalties on hospitals but affect the day-to-day work of hospitalists, while others affect physicians at the individual level.

"There’s a lot of confusion and lack of knowledge about what’s occurring at the physician level and what’s occurring at the hospital level," said Dr. Patrick J. Torcson, a member of the board of directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Carrots, sticks for hospitalists

Two programs will touch hospitalists – and their wallets – directly. Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), a voluntary pay-for-reporting program, has been around since 2007 offering small incentives for participation, but it will soon begin penalizing physicians who don’t report on quality. Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are also phasing in the physician value-based modifier, which will begin adjusting physician payments up or down depending on the quality and cost of the care they provide.

CMS will use PQRS reporting as the basis for the new modifier, making participation in the older program a top priority for all physicians, Dr. Torcson said.

This year, physicians who successfully report quality measures through PQRS can earn a 0.5% bonus on their total allowable Medicare Part B charges. The same bonus will be in place for 2014. But starting in 2015, Medicare will assess a 1.5% penalty on physicians who fail to report successfully. That payment penalty increases to 2% in 2016.

But the PQRS has been criticized as being cumbersome and not especially relevant for hospitalists.

"I think many physicians hoped it would go away," Dr. Torcson said. "It hasn’t. It has expanded."

Hospitalists are currently required to report on at least three quality measures through the program. But Medicare is proposing to require physicians to report on at least nine measures starting in 2014. CMS will issue a final regulation outlining changes to the PQRS in November.

The SHM has recommended instead that CMS limit the expansion to no more than six quality measures to keep from ramping up the program too fast.

In comments to the agency, SHM also noted that the PQRS quality measures, while improving, still do not accurately reflect the scope of care provided by hospitalists. For instance, about half of the measures that hospitalists can report on are related to stroke care, though stoke care is not a primary practice focus for many hospital medicine programs.

Many hospitalists have ignored the PQRS so far, Dr. Torcson said, because the added time and effort of reporting on quality measures outweighed the value of the 0.5% bonus, on average about $500 per physician. But he urged physicians to rethink participation in light of the rollout of the new value-based modifier program.

Value-based modifier coming soon

The physician value-based payment modifier was part of the 2008 Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act and was expanded as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The program seeks to pay physicians more for providing high-quality, low-cost care. But the budget-neutral program will pay less for low-quality, high-cost care. Physician groups could see payment cuts of between 1% and 2% in 2016, based on their performance. Physicians who don’t report on quality measures through the PQRS will get an automatic 1% pay cut under the value-based modifier program.

The value-based modifier already is affecting physicians who work in groups of 100 or more eligible providers. While payments won’t be affected until 2015, CMS will base its adjustments on the data reported to the PQRS in 2013. The program will expand to cover physician groups of 10 or more in 2016, though the measurement on cost and quality will occur in 2014. Payments for all physicians will be subject to the modifier by 2017, based on performance during 2015.

"Physician-level pay for reporting is well underway and now actual pay for performance is here," Dr. Torcson said. "Engagement, familiarity, and participation in the PQRS is really going to be the key for physicians. It’s not too late."

CMS is providing some tools to help physicians understand their performance on cost and quality. The agency is producing annual Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs) that will show the individual physician’s past performance on the measures chosen by CMS. The reports are scheduled to go out to groups of 25 or more eligible professionals this fall. All physicians should start receiving the reports sometime in 2014.

But hospitalists should look closely at their reports, Dr. Torcson said. CMS is still figuring out how to classify the work done by hospitalists. Currently, CMS compares hospitalists’ cost and quality data to general internists even though hospitalized patients have a very different quality and cost profile.

"That’s something where there are still ongoing focused advocacy efforts by SHM to make sure that the attribution and the measurement methodology takes into account the hospitalist model," he said.

Hospitals under pressure, too

But hospitalists have more them just themselves to worry about. Often it’s the hospitalist who is the point person for quality and efficiency in their institution. And Medicare has an array of hospital-focused carrots and sticks, as well.

The hospital value-based purchasing program is already in full swing. For fiscal year 2014, which begins in October 2013, hospitals will have 1.25% of their base operating charges at risk in the program. The program bases payment on a group of clinical process measures, patient satisfaction, and selected mortality measures.

Additionally, Medicare is doubling the maximum penalties for its from 1% to 2% of base operating payments starting this month. The penalties apply to hospitals that have excess 30-day readmissions for pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. CMS is also expected to add more conditions to the list. Total hip and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease will be added to the list of conditions in October 2014.

CMS is also launching a new Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program in October 2014. In this program, which was authorized under the Affordable Care Act, hospitals with the most HACs will see their payments reduced by 1%. During the first year, hospitals will be judged based on several indicators including:

• Pressure ulcer rate.

• Iatrogenic pneumothorax rate.

• Central venous catheter–related blood stream infection rate.

• Postoperative hip fracture rate.

• Postoperative pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis rate.

• Postoperative sepsis rate.

• Wound dehiscence rate.

• Accidental puncture and laceration rate.

• Central line–associated blood stream infection.

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infection.

• Hospitals’ scores will be risk adjusted based on age, sex, and comorbidities.

More regulatory changes

CMS is also making some changes that will impact how hospitalists admit patients. Over the summer, Medicare officials issued a regulation that changes the criteria for when to admit a patient to hospital, as covered under Medicare Part A, and when to place them under observation status under Part B. The new criteria are based on the amount of time the physician expects the patient to spend as an inpatient.

Starting on Oct. 1, 2013, Medicare contractors will assume that a hospital stay is covered under Part A if the physician expects the patient to stay as an inpatient in the hospital for at least 2 midnights. CMS also emphasized in the rule that the inpatient stay does not begin until the patient is formally admitted by a physician.

What can hospitalists do to prepare?

While new regulatory requirements continue to hit hospitals year after year, Dr. Torcson said hospitalists are well prepared to handle the changes.

"The whole purpose and success and value of hospitalists is being the physician champions for the hospital-level performance agenda around core measures, readmissions, hospital-acquired conditions, and medical necessity documentation," he said. "That’s something that hospitalists have been preparing for from day 1, going back to the ’90s."

He urged hospitalists to redouble their efforts as hospital champions for quality.

"Concentrating on the hospital-level performance agenda is really going to be the key for hospital medicine programs to continue to be successful," Dr. Torcson said.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

October marks the start of a new fiscal year for the federal government and with it comes a host of new and revised regulatory requirements for hospitalists and hospitals.

Medicare officials are using some carrots – but mostly sticks – to get hospitals and doctors to improve quality and lower costs. Some of the programs levy financial penalties on hospitals but affect the day-to-day work of hospitalists, while others affect physicians at the individual level.

"There’s a lot of confusion and lack of knowledge about what’s occurring at the physician level and what’s occurring at the hospital level," said Dr. Patrick J. Torcson, a member of the board of directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Carrots, sticks for hospitalists

Two programs will touch hospitalists – and their wallets – directly. Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), a voluntary pay-for-reporting program, has been around since 2007 offering small incentives for participation, but it will soon begin penalizing physicians who don’t report on quality. Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are also phasing in the physician value-based modifier, which will begin adjusting physician payments up or down depending on the quality and cost of the care they provide.

CMS will use PQRS reporting as the basis for the new modifier, making participation in the older program a top priority for all physicians, Dr. Torcson said.

This year, physicians who successfully report quality measures through PQRS can earn a 0.5% bonus on their total allowable Medicare Part B charges. The same bonus will be in place for 2014. But starting in 2015, Medicare will assess a 1.5% penalty on physicians who fail to report successfully. That payment penalty increases to 2% in 2016.

But the PQRS has been criticized as being cumbersome and not especially relevant for hospitalists.

"I think many physicians hoped it would go away," Dr. Torcson said. "It hasn’t. It has expanded."

Hospitalists are currently required to report on at least three quality measures through the program. But Medicare is proposing to require physicians to report on at least nine measures starting in 2014. CMS will issue a final regulation outlining changes to the PQRS in November.

The SHM has recommended instead that CMS limit the expansion to no more than six quality measures to keep from ramping up the program too fast.

In comments to the agency, SHM also noted that the PQRS quality measures, while improving, still do not accurately reflect the scope of care provided by hospitalists. For instance, about half of the measures that hospitalists can report on are related to stroke care, though stoke care is not a primary practice focus for many hospital medicine programs.

Many hospitalists have ignored the PQRS so far, Dr. Torcson said, because the added time and effort of reporting on quality measures outweighed the value of the 0.5% bonus, on average about $500 per physician. But he urged physicians to rethink participation in light of the rollout of the new value-based modifier program.

Value-based modifier coming soon

The physician value-based payment modifier was part of the 2008 Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act and was expanded as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The program seeks to pay physicians more for providing high-quality, low-cost care. But the budget-neutral program will pay less for low-quality, high-cost care. Physician groups could see payment cuts of between 1% and 2% in 2016, based on their performance. Physicians who don’t report on quality measures through the PQRS will get an automatic 1% pay cut under the value-based modifier program.

The value-based modifier already is affecting physicians who work in groups of 100 or more eligible providers. While payments won’t be affected until 2015, CMS will base its adjustments on the data reported to the PQRS in 2013. The program will expand to cover physician groups of 10 or more in 2016, though the measurement on cost and quality will occur in 2014. Payments for all physicians will be subject to the modifier by 2017, based on performance during 2015.

"Physician-level pay for reporting is well underway and now actual pay for performance is here," Dr. Torcson said. "Engagement, familiarity, and participation in the PQRS is really going to be the key for physicians. It’s not too late."

CMS is providing some tools to help physicians understand their performance on cost and quality. The agency is producing annual Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs) that will show the individual physician’s past performance on the measures chosen by CMS. The reports are scheduled to go out to groups of 25 or more eligible professionals this fall. All physicians should start receiving the reports sometime in 2014.

But hospitalists should look closely at their reports, Dr. Torcson said. CMS is still figuring out how to classify the work done by hospitalists. Currently, CMS compares hospitalists’ cost and quality data to general internists even though hospitalized patients have a very different quality and cost profile.

"That’s something where there are still ongoing focused advocacy efforts by SHM to make sure that the attribution and the measurement methodology takes into account the hospitalist model," he said.

Hospitals under pressure, too

But hospitalists have more them just themselves to worry about. Often it’s the hospitalist who is the point person for quality and efficiency in their institution. And Medicare has an array of hospital-focused carrots and sticks, as well.

The hospital value-based purchasing program is already in full swing. For fiscal year 2014, which begins in October 2013, hospitals will have 1.25% of their base operating charges at risk in the program. The program bases payment on a group of clinical process measures, patient satisfaction, and selected mortality measures.

Additionally, Medicare is doubling the maximum penalties for its from 1% to 2% of base operating payments starting this month. The penalties apply to hospitals that have excess 30-day readmissions for pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. CMS is also expected to add more conditions to the list. Total hip and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease will be added to the list of conditions in October 2014.

CMS is also launching a new Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program in October 2014. In this program, which was authorized under the Affordable Care Act, hospitals with the most HACs will see their payments reduced by 1%. During the first year, hospitals will be judged based on several indicators including:

• Pressure ulcer rate.

• Iatrogenic pneumothorax rate.

• Central venous catheter–related blood stream infection rate.

• Postoperative hip fracture rate.

• Postoperative pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis rate.

• Postoperative sepsis rate.

• Wound dehiscence rate.

• Accidental puncture and laceration rate.

• Central line–associated blood stream infection.

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infection.

• Hospitals’ scores will be risk adjusted based on age, sex, and comorbidities.

More regulatory changes

CMS is also making some changes that will impact how hospitalists admit patients. Over the summer, Medicare officials issued a regulation that changes the criteria for when to admit a patient to hospital, as covered under Medicare Part A, and when to place them under observation status under Part B. The new criteria are based on the amount of time the physician expects the patient to spend as an inpatient.

Starting on Oct. 1, 2013, Medicare contractors will assume that a hospital stay is covered under Part A if the physician expects the patient to stay as an inpatient in the hospital for at least 2 midnights. CMS also emphasized in the rule that the inpatient stay does not begin until the patient is formally admitted by a physician.

What can hospitalists do to prepare?

While new regulatory requirements continue to hit hospitals year after year, Dr. Torcson said hospitalists are well prepared to handle the changes.

"The whole purpose and success and value of hospitalists is being the physician champions for the hospital-level performance agenda around core measures, readmissions, hospital-acquired conditions, and medical necessity documentation," he said. "That’s something that hospitalists have been preparing for from day 1, going back to the ’90s."

He urged hospitalists to redouble their efforts as hospital champions for quality.

"Concentrating on the hospital-level performance agenda is really going to be the key for hospital medicine programs to continue to be successful," Dr. Torcson said.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Medicare to pay more for warfarin-reversal treatment

Medicare officials have approved a bonus payment to encourage the use of a new drug that rapidly reverses warfarin therapy in adults with acute major bleeding.

Starting on Oct. 1, Medicare will provide a maximum add-on payment of $1,587.50 for the use of Kcentra (prothrombin complex concentrate, human) in the inpatient hospital setting. The add-on payment is about 50% of the average cost of the treatment. The add-on payment, which will continue for at least 2 years, will be provided when the cost of care exceeds the Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-DRG) payment.

Kcentra is a replacement therapy for fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for patients with an acquired coagulation factor deficiency who are experiencing a severe bleed caused by warfarin. The drug’s maker, CSL Behring, said Kcentra is a good alternative for immunoglobulin A–deficient patients who cannot have FFP, as well as for Jehovah’s witnesses and other patients whose religious beliefs prevent them from accepting transfusions of plasma.

Kcentra, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April (2013), is available as a lyophilized powder that must be reconstituted with sterile water prior to administration as an intravenous infusion. It is dosed based on factor IX units.

Medicare approved the bonus payment as part of the "new technology add-on payment policy" first implemented in 2001, which is aimed at ensuring that Medicare beneficiaries have timely access to new, but expensive drugs and devices. The add-on payments are granted for products that are both innovative and inadequately paid for under the Medicare DRG payment system.

In the fiscal year 2014, Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule, published on Aug. 19, Medicare officials wrote that Kcentra is a "substantial clinical improvement over existing technologies" by providing a rapid resolution a patient’s blood clotting deficiency while decreasing the risk of exposure to blood borne pathogens and other transfusion-associated complications.

Medicare officials have approved a bonus payment to encourage the use of a new drug that rapidly reverses warfarin therapy in adults with acute major bleeding.

Starting on Oct. 1, Medicare will provide a maximum add-on payment of $1,587.50 for the use of Kcentra (prothrombin complex concentrate, human) in the inpatient hospital setting. The add-on payment is about 50% of the average cost of the treatment. The add-on payment, which will continue for at least 2 years, will be provided when the cost of care exceeds the Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-DRG) payment.

Kcentra is a replacement therapy for fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for patients with an acquired coagulation factor deficiency who are experiencing a severe bleed caused by warfarin. The drug’s maker, CSL Behring, said Kcentra is a good alternative for immunoglobulin A–deficient patients who cannot have FFP, as well as for Jehovah’s witnesses and other patients whose religious beliefs prevent them from accepting transfusions of plasma.

Kcentra, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April (2013), is available as a lyophilized powder that must be reconstituted with sterile water prior to administration as an intravenous infusion. It is dosed based on factor IX units.

Medicare approved the bonus payment as part of the "new technology add-on payment policy" first implemented in 2001, which is aimed at ensuring that Medicare beneficiaries have timely access to new, but expensive drugs and devices. The add-on payments are granted for products that are both innovative and inadequately paid for under the Medicare DRG payment system.

In the fiscal year 2014, Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule, published on Aug. 19, Medicare officials wrote that Kcentra is a "substantial clinical improvement over existing technologies" by providing a rapid resolution a patient’s blood clotting deficiency while decreasing the risk of exposure to blood borne pathogens and other transfusion-associated complications.

Medicare officials have approved a bonus payment to encourage the use of a new drug that rapidly reverses warfarin therapy in adults with acute major bleeding.

Starting on Oct. 1, Medicare will provide a maximum add-on payment of $1,587.50 for the use of Kcentra (prothrombin complex concentrate, human) in the inpatient hospital setting. The add-on payment is about 50% of the average cost of the treatment. The add-on payment, which will continue for at least 2 years, will be provided when the cost of care exceeds the Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-DRG) payment.

Kcentra is a replacement therapy for fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for patients with an acquired coagulation factor deficiency who are experiencing a severe bleed caused by warfarin. The drug’s maker, CSL Behring, said Kcentra is a good alternative for immunoglobulin A–deficient patients who cannot have FFP, as well as for Jehovah’s witnesses and other patients whose religious beliefs prevent them from accepting transfusions of plasma.

Kcentra, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April (2013), is available as a lyophilized powder that must be reconstituted with sterile water prior to administration as an intravenous infusion. It is dosed based on factor IX units.

Medicare approved the bonus payment as part of the "new technology add-on payment policy" first implemented in 2001, which is aimed at ensuring that Medicare beneficiaries have timely access to new, but expensive drugs and devices. The add-on payments are granted for products that are both innovative and inadequately paid for under the Medicare DRG payment system.

In the fiscal year 2014, Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule, published on Aug. 19, Medicare officials wrote that Kcentra is a "substantial clinical improvement over existing technologies" by providing a rapid resolution a patient’s blood clotting deficiency while decreasing the risk of exposure to blood borne pathogens and other transfusion-associated complications.

Medicare drops certification requirement for bariatric surgery

Medicare is dropping its requirement that bariatric surgery facilities be certified.

In a controversial move, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced Sept. 24 that the evidence is sufficient to conclude that certification does not improve health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. As a result, the agency will no longer make certification a condition of Medicare coverage.

The decision reverses the agency’s February 2006 requirements. Since then, Medicare has covered bariatric procedures only when performed at facilities that were either certified by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) as a Level 1 Bariatric Surgery Center or certified by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) as a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence.

In their announcement, CMS officials said they were leaning in this direction in June when they proposed to lift the certification requirement and asked for public comments.

The response overwhelmingly supported certification. Of the 483 comments received, only 92 favored eliminating the certification requirement.

The change was opposed by physician groups including the ASMBS and the ACS, which operate the certification programs referenced in the previous CMS coverage policy. The groups warned the CMS that dropping the certification requirement would put the safety of vulnerable Medicare patients at risk.

Dr. Jaime Ponce, ASMBS President, said in a statement that he was "disappointed" in the Medicare decision but encouraged that private insurers such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, Cigna, and Optum/United Healthcare continue to support accreditation.

The CMS agreed that there is a role for accreditation programs going forward, but said that they are not necessary to ensure safe outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries.

"The removal of a coverage requirement does not require facilities to discontinue practices which they find beneficial," according to the decision memo.

Facilities may choose to continue with certification in order to distinguish themselves from the competition, for instance.

"While CMS agrees with the value of the multidisciplinary team approach and structure, we do not believe that every valued endeavor needs to be buttressed by a Medicare mandate," the memo states. "We expect all facilities to strive to provide the proper equipment and services to meet the needs of its patient population."

CMS officials reviewed nine studies to determine if certification meaningfully improved health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. The results were "mixed," the agency said, but overall the evidence showed "no consistent statistical or clinically meaningful difference." Further, nothing in the literature suggested a worsening of outcomes without certification.

The factors that led to the original certification requirements – the rapid growth in bariatric procedures and concerns about higher mortality rates – have changed, the CMS wrote.

The policy switch was requested by health services researchers at the University of Michigan led by Dr. John D. Birkmeyer, professor of surgery and director of the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The scientists asserted that certified facilities were no safer than noncertified ones and that mortality and serious complication rates for bariatric surgery had declined across the country.

The CMS coverage decision did not make changes to the bariatric procedures covered by the agency. Medicare will continue to cover open and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; and open and laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for Medicare beneficiaries with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater in those with at least one comorbidity related to obesity who previously have been unsuccessful with medical treatment for obesity.

Medicare is dropping its requirement that bariatric surgery facilities be certified.

In a controversial move, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced Sept. 24 that the evidence is sufficient to conclude that certification does not improve health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. As a result, the agency will no longer make certification a condition of Medicare coverage.

The decision reverses the agency’s February 2006 requirements. Since then, Medicare has covered bariatric procedures only when performed at facilities that were either certified by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) as a Level 1 Bariatric Surgery Center or certified by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) as a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence.

In their announcement, CMS officials said they were leaning in this direction in June when they proposed to lift the certification requirement and asked for public comments.

The response overwhelmingly supported certification. Of the 483 comments received, only 92 favored eliminating the certification requirement.

The change was opposed by physician groups including the ASMBS and the ACS, which operate the certification programs referenced in the previous CMS coverage policy. The groups warned the CMS that dropping the certification requirement would put the safety of vulnerable Medicare patients at risk.

Dr. Jaime Ponce, ASMBS President, said in a statement that he was "disappointed" in the Medicare decision but encouraged that private insurers such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, Cigna, and Optum/United Healthcare continue to support accreditation.

The CMS agreed that there is a role for accreditation programs going forward, but said that they are not necessary to ensure safe outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries.

"The removal of a coverage requirement does not require facilities to discontinue practices which they find beneficial," according to the decision memo.

Facilities may choose to continue with certification in order to distinguish themselves from the competition, for instance.

"While CMS agrees with the value of the multidisciplinary team approach and structure, we do not believe that every valued endeavor needs to be buttressed by a Medicare mandate," the memo states. "We expect all facilities to strive to provide the proper equipment and services to meet the needs of its patient population."

CMS officials reviewed nine studies to determine if certification meaningfully improved health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. The results were "mixed," the agency said, but overall the evidence showed "no consistent statistical or clinically meaningful difference." Further, nothing in the literature suggested a worsening of outcomes without certification.

The factors that led to the original certification requirements – the rapid growth in bariatric procedures and concerns about higher mortality rates – have changed, the CMS wrote.

The policy switch was requested by health services researchers at the University of Michigan led by Dr. John D. Birkmeyer, professor of surgery and director of the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The scientists asserted that certified facilities were no safer than noncertified ones and that mortality and serious complication rates for bariatric surgery had declined across the country.

The CMS coverage decision did not make changes to the bariatric procedures covered by the agency. Medicare will continue to cover open and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; and open and laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for Medicare beneficiaries with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater in those with at least one comorbidity related to obesity who previously have been unsuccessful with medical treatment for obesity.

Medicare is dropping its requirement that bariatric surgery facilities be certified.

In a controversial move, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced Sept. 24 that the evidence is sufficient to conclude that certification does not improve health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. As a result, the agency will no longer make certification a condition of Medicare coverage.

The decision reverses the agency’s February 2006 requirements. Since then, Medicare has covered bariatric procedures only when performed at facilities that were either certified by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) as a Level 1 Bariatric Surgery Center or certified by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) as a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence.

In their announcement, CMS officials said they were leaning in this direction in June when they proposed to lift the certification requirement and asked for public comments.

The response overwhelmingly supported certification. Of the 483 comments received, only 92 favored eliminating the certification requirement.

The change was opposed by physician groups including the ASMBS and the ACS, which operate the certification programs referenced in the previous CMS coverage policy. The groups warned the CMS that dropping the certification requirement would put the safety of vulnerable Medicare patients at risk.

Dr. Jaime Ponce, ASMBS President, said in a statement that he was "disappointed" in the Medicare decision but encouraged that private insurers such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, Cigna, and Optum/United Healthcare continue to support accreditation.

The CMS agreed that there is a role for accreditation programs going forward, but said that they are not necessary to ensure safe outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries.

"The removal of a coverage requirement does not require facilities to discontinue practices which they find beneficial," according to the decision memo.

Facilities may choose to continue with certification in order to distinguish themselves from the competition, for instance.

"While CMS agrees with the value of the multidisciplinary team approach and structure, we do not believe that every valued endeavor needs to be buttressed by a Medicare mandate," the memo states. "We expect all facilities to strive to provide the proper equipment and services to meet the needs of its patient population."

CMS officials reviewed nine studies to determine if certification meaningfully improved health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. The results were "mixed," the agency said, but overall the evidence showed "no consistent statistical or clinically meaningful difference." Further, nothing in the literature suggested a worsening of outcomes without certification.

The factors that led to the original certification requirements – the rapid growth in bariatric procedures and concerns about higher mortality rates – have changed, the CMS wrote.

The policy switch was requested by health services researchers at the University of Michigan led by Dr. John D. Birkmeyer, professor of surgery and director of the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The scientists asserted that certified facilities were no safer than noncertified ones and that mortality and serious complication rates for bariatric surgery had declined across the country.

The CMS coverage decision did not make changes to the bariatric procedures covered by the agency. Medicare will continue to cover open and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; and open and laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for Medicare beneficiaries with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater in those with at least one comorbidity related to obesity who previously have been unsuccessful with medical treatment for obesity.

FDA rolls out unique ID system for medical devices

The Food and Drug Administration is moving forward with plans to create a unique identification system for medical devices over the next several years.

In a final rule published Sept. 24, the agency outlined a schedule for placing a unique ID number on most medical devices over 7 years and launching a publicly searchable database with all of the product information.

The new Unique Device Identification (UDI) system requires medical device manufacturers to create a unique number for every version or model of a device. The number will include the lot or batch number, device expiration date, and manufacturing date. That information will then be incorporated into the Global Unique Device Identification Database (GUDID), run by the FDA. The new database will not store identifying patient information, according to the agency.

The new system should help to improve adverse event reporting, allow for faster recalls, and reduce counterfeiting and device diversion, according to the FDA.

"A consistent and clear way to identify medical devices will result in more reliable data on how medical devices are used," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. "In turn, this can promote safe device use by providers and patients as well as faster, more innovative, and less costly device development."

While there are no requirements for physicians under the new regulations, FDA officials wrote that they anticipate physicians and other providers will include the unique identifiers in patients’ electronic health records and personal health records to help improve postmarket surveillance, adverse event reporting, and recalls.

Manufacturers of high-risk medical devices, those in class III, are required to place the identifiers on the label and packaging by Sept. 24, 2014. They must also submit information to GUDID within 1 year. Manufacturers of implantable, life-supporting, and life-sustaining devices have until Sept. 24, 2015, to comply.

For moderate-risk devices (class II), manufacturers have 3 years to transition their labeling; and for low-risk devices (class I) they have 5 years. For certain class I and unclassified devices, the compliance date is pushed out to 2020.

The FDA noted that many low-risk devices are exempt from some or all of the labeling requirements in the final rule.

The final rule was called an improvement over a July 2012 proposed rule by the medical device industry. The Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) said the final rule made some key changes, such as not requiring that the ID number be marked directly on implants and allowing manufacturers an extra 3 years for devices that are already out in circulation. The FDA is also allowing firms that produce class III devices to petition for a 1-year extension if the extra time is necessary to protect public health.

Implementing the UDI system will be "costly and challenging," Janet Trunzo, senior executive vice president for technology and regulatory affairs at AdvaMed, said in a statement. "It is imperative that it is implemented correctly the first time, and that its ongoing use is practical, economical, and of value to patients, health care providers, industry, and FDA."

The Pew Charitable Trusts, a watchdog group, applauded the FDA for getting the UDI system off the ground. But the final rule is only the first step, Josh Rising, director of Pew’s medical devices initiative, said in a statement. Hospitals, health plans, and physicians need to integrate the identifiers into patients’ health records and insurance billing transactions before the benefits can be fully realized, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration is moving forward with plans to create a unique identification system for medical devices over the next several years.

In a final rule published Sept. 24, the agency outlined a schedule for placing a unique ID number on most medical devices over 7 years and launching a publicly searchable database with all of the product information.

The new Unique Device Identification (UDI) system requires medical device manufacturers to create a unique number for every version or model of a device. The number will include the lot or batch number, device expiration date, and manufacturing date. That information will then be incorporated into the Global Unique Device Identification Database (GUDID), run by the FDA. The new database will not store identifying patient information, according to the agency.

The new system should help to improve adverse event reporting, allow for faster recalls, and reduce counterfeiting and device diversion, according to the FDA.

"A consistent and clear way to identify medical devices will result in more reliable data on how medical devices are used," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. "In turn, this can promote safe device use by providers and patients as well as faster, more innovative, and less costly device development."

While there are no requirements for physicians under the new regulations, FDA officials wrote that they anticipate physicians and other providers will include the unique identifiers in patients’ electronic health records and personal health records to help improve postmarket surveillance, adverse event reporting, and recalls.

Manufacturers of high-risk medical devices, those in class III, are required to place the identifiers on the label and packaging by Sept. 24, 2014. They must also submit information to GUDID within 1 year. Manufacturers of implantable, life-supporting, and life-sustaining devices have until Sept. 24, 2015, to comply.

For moderate-risk devices (class II), manufacturers have 3 years to transition their labeling; and for low-risk devices (class I) they have 5 years. For certain class I and unclassified devices, the compliance date is pushed out to 2020.

The FDA noted that many low-risk devices are exempt from some or all of the labeling requirements in the final rule.

The final rule was called an improvement over a July 2012 proposed rule by the medical device industry. The Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) said the final rule made some key changes, such as not requiring that the ID number be marked directly on implants and allowing manufacturers an extra 3 years for devices that are already out in circulation. The FDA is also allowing firms that produce class III devices to petition for a 1-year extension if the extra time is necessary to protect public health.

Implementing the UDI system will be "costly and challenging," Janet Trunzo, senior executive vice president for technology and regulatory affairs at AdvaMed, said in a statement. "It is imperative that it is implemented correctly the first time, and that its ongoing use is practical, economical, and of value to patients, health care providers, industry, and FDA."

The Pew Charitable Trusts, a watchdog group, applauded the FDA for getting the UDI system off the ground. But the final rule is only the first step, Josh Rising, director of Pew’s medical devices initiative, said in a statement. Hospitals, health plans, and physicians need to integrate the identifiers into patients’ health records and insurance billing transactions before the benefits can be fully realized, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration is moving forward with plans to create a unique identification system for medical devices over the next several years.

In a final rule published Sept. 24, the agency outlined a schedule for placing a unique ID number on most medical devices over 7 years and launching a publicly searchable database with all of the product information.

The new Unique Device Identification (UDI) system requires medical device manufacturers to create a unique number for every version or model of a device. The number will include the lot or batch number, device expiration date, and manufacturing date. That information will then be incorporated into the Global Unique Device Identification Database (GUDID), run by the FDA. The new database will not store identifying patient information, according to the agency.

The new system should help to improve adverse event reporting, allow for faster recalls, and reduce counterfeiting and device diversion, according to the FDA.

"A consistent and clear way to identify medical devices will result in more reliable data on how medical devices are used," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. "In turn, this can promote safe device use by providers and patients as well as faster, more innovative, and less costly device development."

While there are no requirements for physicians under the new regulations, FDA officials wrote that they anticipate physicians and other providers will include the unique identifiers in patients’ electronic health records and personal health records to help improve postmarket surveillance, adverse event reporting, and recalls.

Manufacturers of high-risk medical devices, those in class III, are required to place the identifiers on the label and packaging by Sept. 24, 2014. They must also submit information to GUDID within 1 year. Manufacturers of implantable, life-supporting, and life-sustaining devices have until Sept. 24, 2015, to comply.

For moderate-risk devices (class II), manufacturers have 3 years to transition their labeling; and for low-risk devices (class I) they have 5 years. For certain class I and unclassified devices, the compliance date is pushed out to 2020.

The FDA noted that many low-risk devices are exempt from some or all of the labeling requirements in the final rule.

The final rule was called an improvement over a July 2012 proposed rule by the medical device industry. The Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) said the final rule made some key changes, such as not requiring that the ID number be marked directly on implants and allowing manufacturers an extra 3 years for devices that are already out in circulation. The FDA is also allowing firms that produce class III devices to petition for a 1-year extension if the extra time is necessary to protect public health.

Implementing the UDI system will be "costly and challenging," Janet Trunzo, senior executive vice president for technology and regulatory affairs at AdvaMed, said in a statement. "It is imperative that it is implemented correctly the first time, and that its ongoing use is practical, economical, and of value to patients, health care providers, industry, and FDA."

The Pew Charitable Trusts, a watchdog group, applauded the FDA for getting the UDI system off the ground. But the final rule is only the first step, Josh Rising, director of Pew’s medical devices initiative, said in a statement. Hospitals, health plans, and physicians need to integrate the identifiers into patients’ health records and insurance billing transactions before the benefits can be fully realized, he said.

FDA to regulate few medical apps

Officials at the Food and Drug Administration have no plans to regulate mobile applications that let consumers compare their symptoms to a list of medical conditions, link patients to a portal with their own health information, or allow patients to measure and track their own vital signs.

But the agency has identified a limited scope of mobile medical apps that it intends to regulate because they function as medical devices and pose a potential safety risk if they malfunction. For instance, a mobile app that uses either internal or external sensors to create an electronic stethoscope would be regulated as a medical device.

The FDA issued a 43-page guidance document on Sept. 23 outlining its regulatory approach and listing examples of what will be regulated, what probably won’t be regulated, and what is not considered a medical app.

In general, the FDA plans to regulate mobile apps that act as an extension of a medical device by displaying, storing, analyzing, or transmitting patient-specific medical data. Also, the agency will regulate apps that transform a mobile platform into a device, such as the attachment of electrocardiographic (ECG) electrodes to a mobile platform to measure, store, or display ECG signals.

Mobile apps will be regulated if they perform patient-specific diagnoses or make treatment recommendations. This type of app might use patient data to calculate a drug dosage or create a dosage plan for radiation therapy.

The agency does not plan to regulate apps that help patients self-manage their health conditions, provide tools for patients to track their health information, automate simple tasks for providers, or allow patients and providers to interact with a personal health record or an electronic health record.

"Although many mobile apps pertain to health, of which many may be medical devices, we are only continuing our oversight for a very small subset of those mobile apps that are medical devices," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said during a press briefing. "We believe this approach will promote innovation, while protecting patient safety, by focusing on those mobile apps that pose greater risk to patients."

But even if an app is deemed a mobile medical app by the FDA, the agency does not intend to regulate apps that pose minimal risks to consumers. For instance, a mobile app that prompts consumers to enter which herbs or drugs they would like to take concurrently and provides drug interaction information could be considered a medical device, according to the guidance document. But because it poses a low risk to the public, the agency does not intend to regulate it at this time.

The FDA first issued draft guidance on mobile medical apps in July 2011. This final guidance document represents the agency’s current thinking on the topic, but it is not binding on either the agency or the public.

"Regulating mobile apps is nothing new for us," Dr. Shuren said. Over the past 15 years, the FDA has cleared more than 75 apps, with about 20 of those receiving approval in the past year.

The guidance also makes clear that physicians who create mobile medical apps, or who customize a medical app for their own professional use, are not subject to regulation as long as they aren’t promoting it for general use by others. Even if the physician allows the app to be used by others in a group practice, he or she is still not considered a manufacturer under the FDA guidance.

The guidance does not apply to clinical decision support software. That software will be addressed as part of a larger health information technology regulatory framework that the FDA is working on in collaboration with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Officials at the Food and Drug Administration have no plans to regulate mobile applications that let consumers compare their symptoms to a list of medical conditions, link patients to a portal with their own health information, or allow patients to measure and track their own vital signs.

But the agency has identified a limited scope of mobile medical apps that it intends to regulate because they function as medical devices and pose a potential safety risk if they malfunction. For instance, a mobile app that uses either internal or external sensors to create an electronic stethoscope would be regulated as a medical device.

The FDA issued a 43-page guidance document on Sept. 23 outlining its regulatory approach and listing examples of what will be regulated, what probably won’t be regulated, and what is not considered a medical app.

In general, the FDA plans to regulate mobile apps that act as an extension of a medical device by displaying, storing, analyzing, or transmitting patient-specific medical data. Also, the agency will regulate apps that transform a mobile platform into a device, such as the attachment of electrocardiographic (ECG) electrodes to a mobile platform to measure, store, or display ECG signals.

Mobile apps will be regulated if they perform patient-specific diagnoses or make treatment recommendations. This type of app might use patient data to calculate a drug dosage or create a dosage plan for radiation therapy.

The agency does not plan to regulate apps that help patients self-manage their health conditions, provide tools for patients to track their health information, automate simple tasks for providers, or allow patients and providers to interact with a personal health record or an electronic health record.

"Although many mobile apps pertain to health, of which many may be medical devices, we are only continuing our oversight for a very small subset of those mobile apps that are medical devices," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said during a press briefing. "We believe this approach will promote innovation, while protecting patient safety, by focusing on those mobile apps that pose greater risk to patients."

But even if an app is deemed a mobile medical app by the FDA, the agency does not intend to regulate apps that pose minimal risks to consumers. For instance, a mobile app that prompts consumers to enter which herbs or drugs they would like to take concurrently and provides drug interaction information could be considered a medical device, according to the guidance document. But because it poses a low risk to the public, the agency does not intend to regulate it at this time.

The FDA first issued draft guidance on mobile medical apps in July 2011. This final guidance document represents the agency’s current thinking on the topic, but it is not binding on either the agency or the public.

"Regulating mobile apps is nothing new for us," Dr. Shuren said. Over the past 15 years, the FDA has cleared more than 75 apps, with about 20 of those receiving approval in the past year.

The guidance also makes clear that physicians who create mobile medical apps, or who customize a medical app for their own professional use, are not subject to regulation as long as they aren’t promoting it for general use by others. Even if the physician allows the app to be used by others in a group practice, he or she is still not considered a manufacturer under the FDA guidance.

The guidance does not apply to clinical decision support software. That software will be addressed as part of a larger health information technology regulatory framework that the FDA is working on in collaboration with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Officials at the Food and Drug Administration have no plans to regulate mobile applications that let consumers compare their symptoms to a list of medical conditions, link patients to a portal with their own health information, or allow patients to measure and track their own vital signs.

But the agency has identified a limited scope of mobile medical apps that it intends to regulate because they function as medical devices and pose a potential safety risk if they malfunction. For instance, a mobile app that uses either internal or external sensors to create an electronic stethoscope would be regulated as a medical device.

The FDA issued a 43-page guidance document on Sept. 23 outlining its regulatory approach and listing examples of what will be regulated, what probably won’t be regulated, and what is not considered a medical app.

In general, the FDA plans to regulate mobile apps that act as an extension of a medical device by displaying, storing, analyzing, or transmitting patient-specific medical data. Also, the agency will regulate apps that transform a mobile platform into a device, such as the attachment of electrocardiographic (ECG) electrodes to a mobile platform to measure, store, or display ECG signals.

Mobile apps will be regulated if they perform patient-specific diagnoses or make treatment recommendations. This type of app might use patient data to calculate a drug dosage or create a dosage plan for radiation therapy.

The agency does not plan to regulate apps that help patients self-manage their health conditions, provide tools for patients to track their health information, automate simple tasks for providers, or allow patients and providers to interact with a personal health record or an electronic health record.

"Although many mobile apps pertain to health, of which many may be medical devices, we are only continuing our oversight for a very small subset of those mobile apps that are medical devices," Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said during a press briefing. "We believe this approach will promote innovation, while protecting patient safety, by focusing on those mobile apps that pose greater risk to patients."

But even if an app is deemed a mobile medical app by the FDA, the agency does not intend to regulate apps that pose minimal risks to consumers. For instance, a mobile app that prompts consumers to enter which herbs or drugs they would like to take concurrently and provides drug interaction information could be considered a medical device, according to the guidance document. But because it poses a low risk to the public, the agency does not intend to regulate it at this time.

The FDA first issued draft guidance on mobile medical apps in July 2011. This final guidance document represents the agency’s current thinking on the topic, but it is not binding on either the agency or the public.

"Regulating mobile apps is nothing new for us," Dr. Shuren said. Over the past 15 years, the FDA has cleared more than 75 apps, with about 20 of those receiving approval in the past year.

The guidance also makes clear that physicians who create mobile medical apps, or who customize a medical app for their own professional use, are not subject to regulation as long as they aren’t promoting it for general use by others. Even if the physician allows the app to be used by others in a group practice, he or she is still not considered a manufacturer under the FDA guidance.

The guidance does not apply to clinical decision support software. That software will be addressed as part of a larger health information technology regulatory framework that the FDA is working on in collaboration with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Uninsured number holds steady during ACA implementation lull

About 48 million Americans lacked health insurance in 2012, a figure not significantly changed from 2011, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau on Sept. 17.

But the percentage of Americans who had health coverage rose slightly in 2012, compared with 2011. The most recent figures from the Census Bureau show that 84.6% of Americans had health insurance in 2012, compared with 84.3% in the previous year. Gains in coverage came largely from government programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and military health care programs.

Private insurance coverage held steady between 2011 and 2012, with 64% of Americans getting their coverage from those plans. Most private coverage was employer-sponsored.

The percentage of Americans whose health coverage came from government-sponsored programs increased for the sixth consecutive year, growing to 33%. Though Medicaid coverage stayed about the same at about 16%, Medicare coverage rose from 15.2% to 15.7% between 2011 and 2012. That uptick is likely due to the first wave of baby boomers entering the Medicare program, said David S. Johnson, Ph.D., chief of the social, economic, and housing statistics division of the U.S. Census Bureau.

The rate of uninsured among children under age 18 fell from 9.4% (7.0 million) to 8.9% (6.6 million) between 2011 and 2012.

However, the uninsured rate was statistically unchanged in all other age groups, including young adults aged 19-25 years. Since 2009, the uninsured rate for young adults had dropped 4.2%, putting it on par with adults aged 26-34 years. The recent decline has been attributed to the Affordable Care Act provision that allows young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance as dependents up to age 26. But now that the provision has been in effect for a few years, the bulk of the declines have been realized, Dr. Johnson said.

The ACA has also required states to maintain their eligibility levels for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), said Edwin Park, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "Medicaid and CHIP have either increased or stayed steady and, particularly in the case of kids, that has more than offset declines in private coverage," he said.

But the most dramatic impacts of the ACA won’t be seen until 2014, when the health insurance exchanges open and some states expand their Medicaid eligibility, Mr. Park said. He cited Congressional Budget Office estimates that about 13 million individuals who otherwise would be uninsured would gain coverage in 2014, with the number rising to about 25 million by 2016. But due to the 1-year lag in census data, data on the extent of the insurance uptake won’t be available until 2015, he said.

The current census findings are based on data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

About 48 million Americans lacked health insurance in 2012, a figure not significantly changed from 2011, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau on Sept. 17.

But the percentage of Americans who had health coverage rose slightly in 2012, compared with 2011. The most recent figures from the Census Bureau show that 84.6% of Americans had health insurance in 2012, compared with 84.3% in the previous year. Gains in coverage came largely from government programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and military health care programs.

Private insurance coverage held steady between 2011 and 2012, with 64% of Americans getting their coverage from those plans. Most private coverage was employer-sponsored.

The percentage of Americans whose health coverage came from government-sponsored programs increased for the sixth consecutive year, growing to 33%. Though Medicaid coverage stayed about the same at about 16%, Medicare coverage rose from 15.2% to 15.7% between 2011 and 2012. That uptick is likely due to the first wave of baby boomers entering the Medicare program, said David S. Johnson, Ph.D., chief of the social, economic, and housing statistics division of the U.S. Census Bureau.

The rate of uninsured among children under age 18 fell from 9.4% (7.0 million) to 8.9% (6.6 million) between 2011 and 2012.

However, the uninsured rate was statistically unchanged in all other age groups, including young adults aged 19-25 years. Since 2009, the uninsured rate for young adults had dropped 4.2%, putting it on par with adults aged 26-34 years. The recent decline has been attributed to the Affordable Care Act provision that allows young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance as dependents up to age 26. But now that the provision has been in effect for a few years, the bulk of the declines have been realized, Dr. Johnson said.

The ACA has also required states to maintain their eligibility levels for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), said Edwin Park, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "Medicaid and CHIP have either increased or stayed steady and, particularly in the case of kids, that has more than offset declines in private coverage," he said.

But the most dramatic impacts of the ACA won’t be seen until 2014, when the health insurance exchanges open and some states expand their Medicaid eligibility, Mr. Park said. He cited Congressional Budget Office estimates that about 13 million individuals who otherwise would be uninsured would gain coverage in 2014, with the number rising to about 25 million by 2016. But due to the 1-year lag in census data, data on the extent of the insurance uptake won’t be available until 2015, he said.

The current census findings are based on data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

About 48 million Americans lacked health insurance in 2012, a figure not significantly changed from 2011, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau on Sept. 17.

But the percentage of Americans who had health coverage rose slightly in 2012, compared with 2011. The most recent figures from the Census Bureau show that 84.6% of Americans had health insurance in 2012, compared with 84.3% in the previous year. Gains in coverage came largely from government programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and military health care programs.

Private insurance coverage held steady between 2011 and 2012, with 64% of Americans getting their coverage from those plans. Most private coverage was employer-sponsored.

The percentage of Americans whose health coverage came from government-sponsored programs increased for the sixth consecutive year, growing to 33%. Though Medicaid coverage stayed about the same at about 16%, Medicare coverage rose from 15.2% to 15.7% between 2011 and 2012. That uptick is likely due to the first wave of baby boomers entering the Medicare program, said David S. Johnson, Ph.D., chief of the social, economic, and housing statistics division of the U.S. Census Bureau.

The rate of uninsured among children under age 18 fell from 9.4% (7.0 million) to 8.9% (6.6 million) between 2011 and 2012.

However, the uninsured rate was statistically unchanged in all other age groups, including young adults aged 19-25 years. Since 2009, the uninsured rate for young adults had dropped 4.2%, putting it on par with adults aged 26-34 years. The recent decline has been attributed to the Affordable Care Act provision that allows young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance as dependents up to age 26. But now that the provision has been in effect for a few years, the bulk of the declines have been realized, Dr. Johnson said.

The ACA has also required states to maintain their eligibility levels for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), said Edwin Park, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "Medicaid and CHIP have either increased or stayed steady and, particularly in the case of kids, that has more than offset declines in private coverage," he said.

But the most dramatic impacts of the ACA won’t be seen until 2014, when the health insurance exchanges open and some states expand their Medicaid eligibility, Mr. Park said. He cited Congressional Budget Office estimates that about 13 million individuals who otherwise would be uninsured would gain coverage in 2014, with the number rising to about 25 million by 2016. But due to the 1-year lag in census data, data on the extent of the insurance uptake won’t be available until 2015, he said.

The current census findings are based on data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

HHS releases tools for patient consent to share data electronically

As more medical practices exchange patients’ health information electronically with hospitals and other providers, physicians have a new problem on their hands: how to explain the process to patients and gain their consent to share the information.

Federal health officials have developed some tools – including customizable patient videos – that aim to simplify the process by creating a standardized explanation of the data exchange process and patient options for sharing their medical information.

The effort, known as meaningful consent, deals specifically with information shared through health information exchange organizations (HIEs). These third-party organizations help health care providers in several ways, including directly exchanging information and orders, allowing providers to request specific patient information, or allowing consumers to aggregate their own data online to share with specific providers.

While state laws and regulations create a patchwork of different requirements for when patient consent is required to release information for treatment, federal officials are encouraging physicians to develop a "meaningful consent" process that includes education about how the information is shared, gives patients time to review the educational materials, and allows them to change or revoke their consent at any time.

The HHS Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) recently conducted a pilot project to test the use of tablet computers to educate patients about their options in sharing information through an HIE. The project, which was completed in March 2013, found that patients were most interested in who could access their information, whether sensitive health information would be shared, how the information would be protected from misuse, and why it needed to be shared at all.

"As patients become more engaged in their health care, it’s vitally important that they understand more about various aspects of their choices when it relates to sharing their health in the electronic health information exchange environment," Joy Pritts, ONC’s chief privacy officer, said in a statement.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY