User login

Video-Based Coaching for Dermatology Resident Surgical Education

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

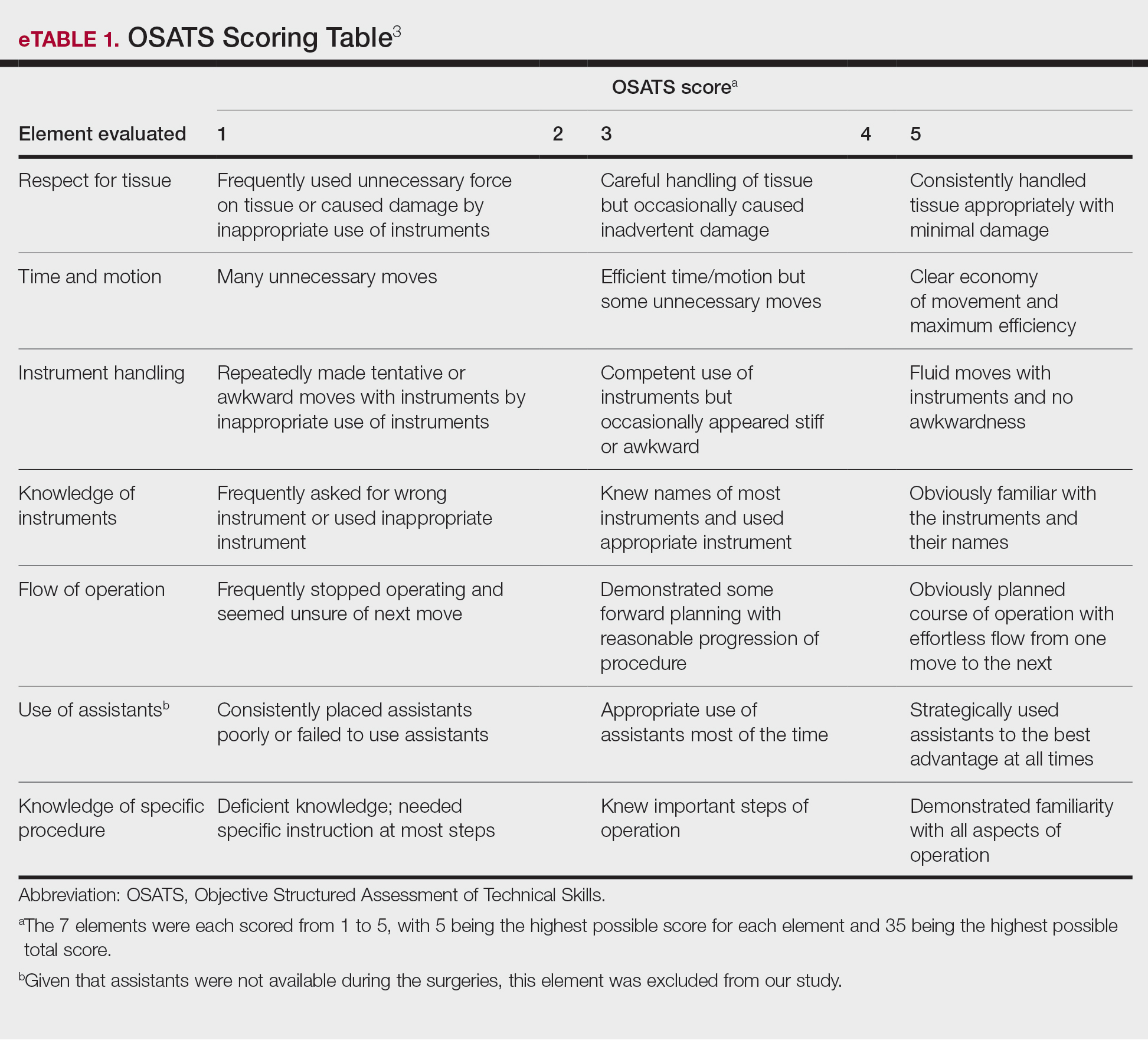

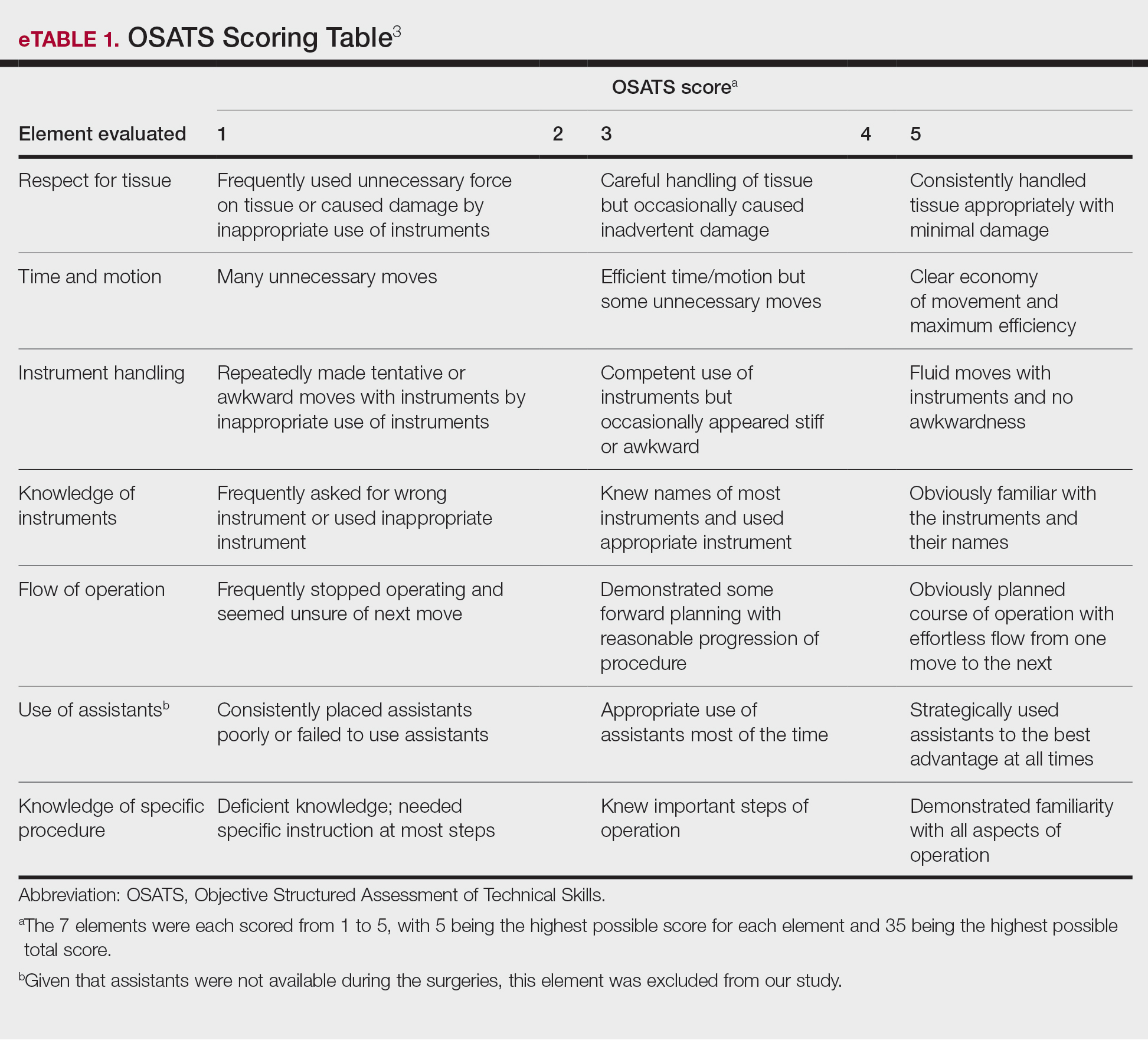

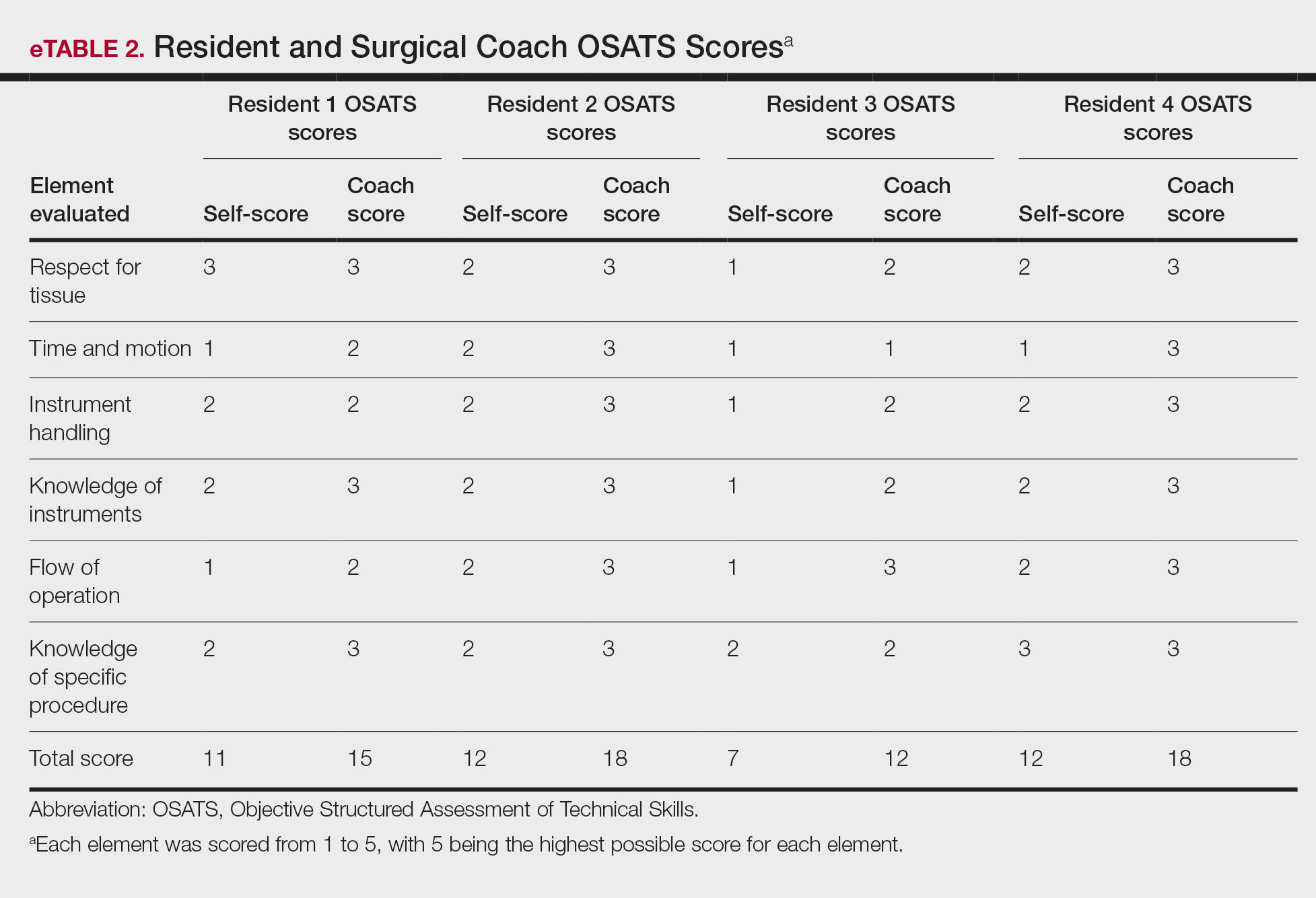

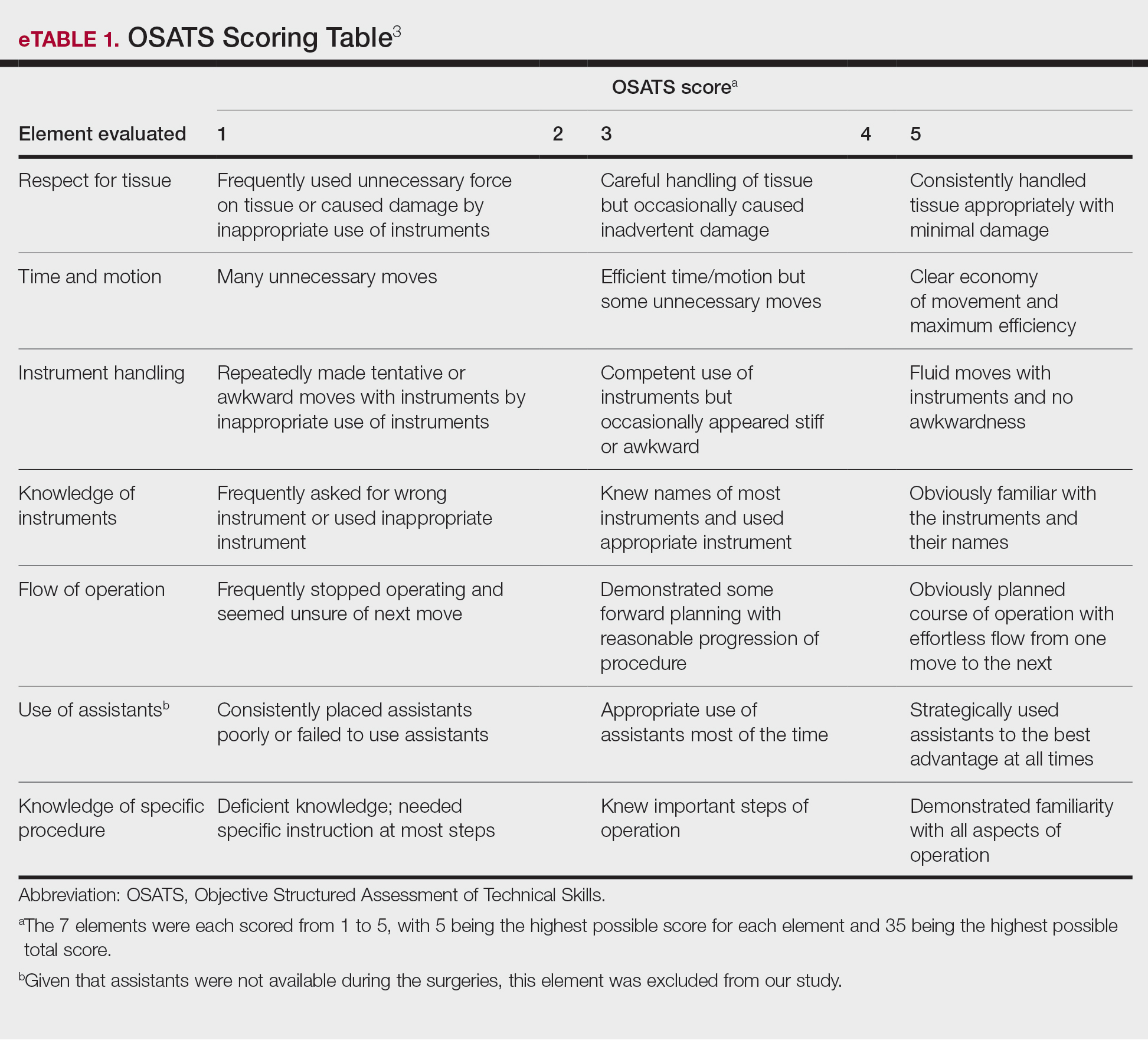

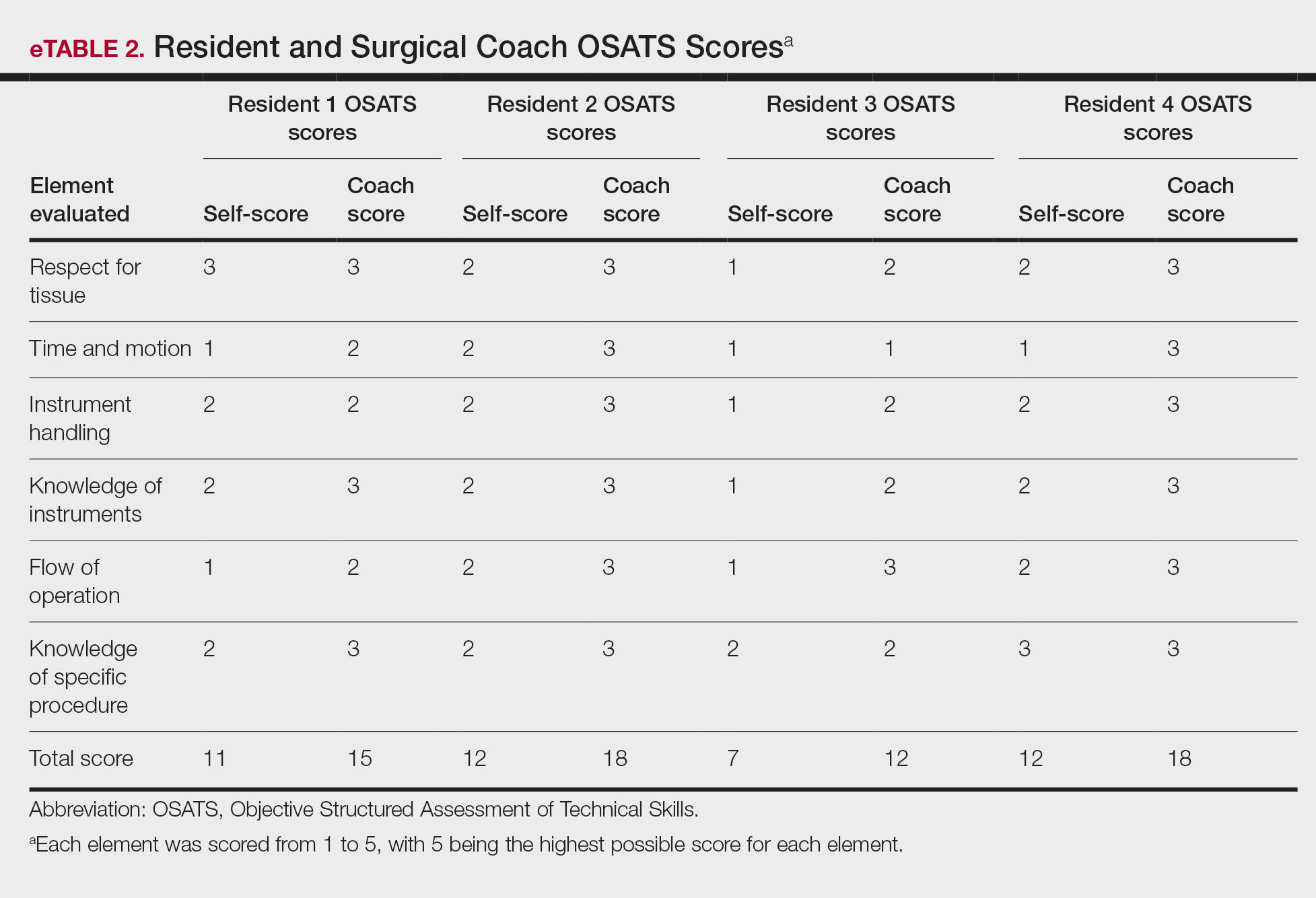

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

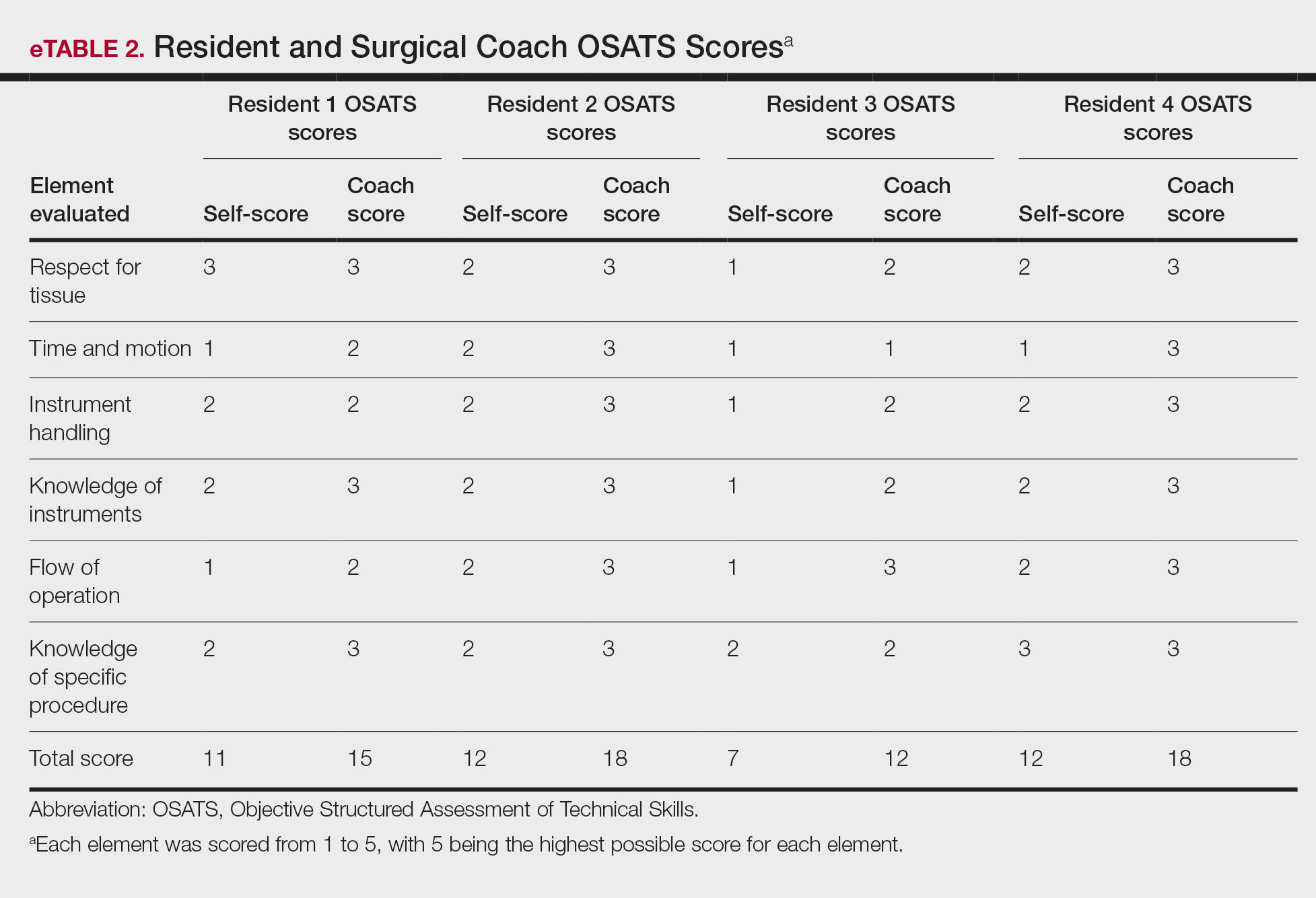

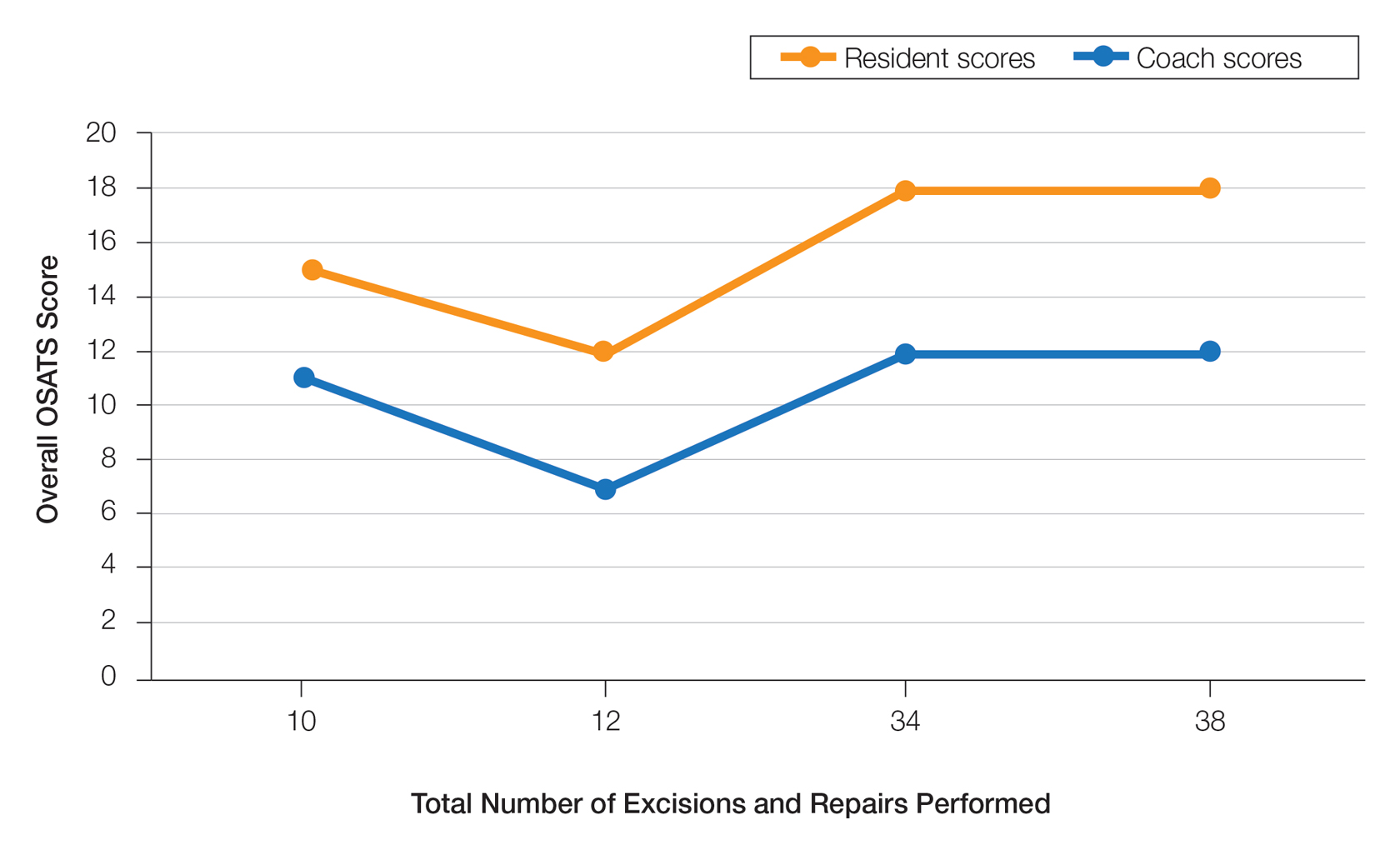

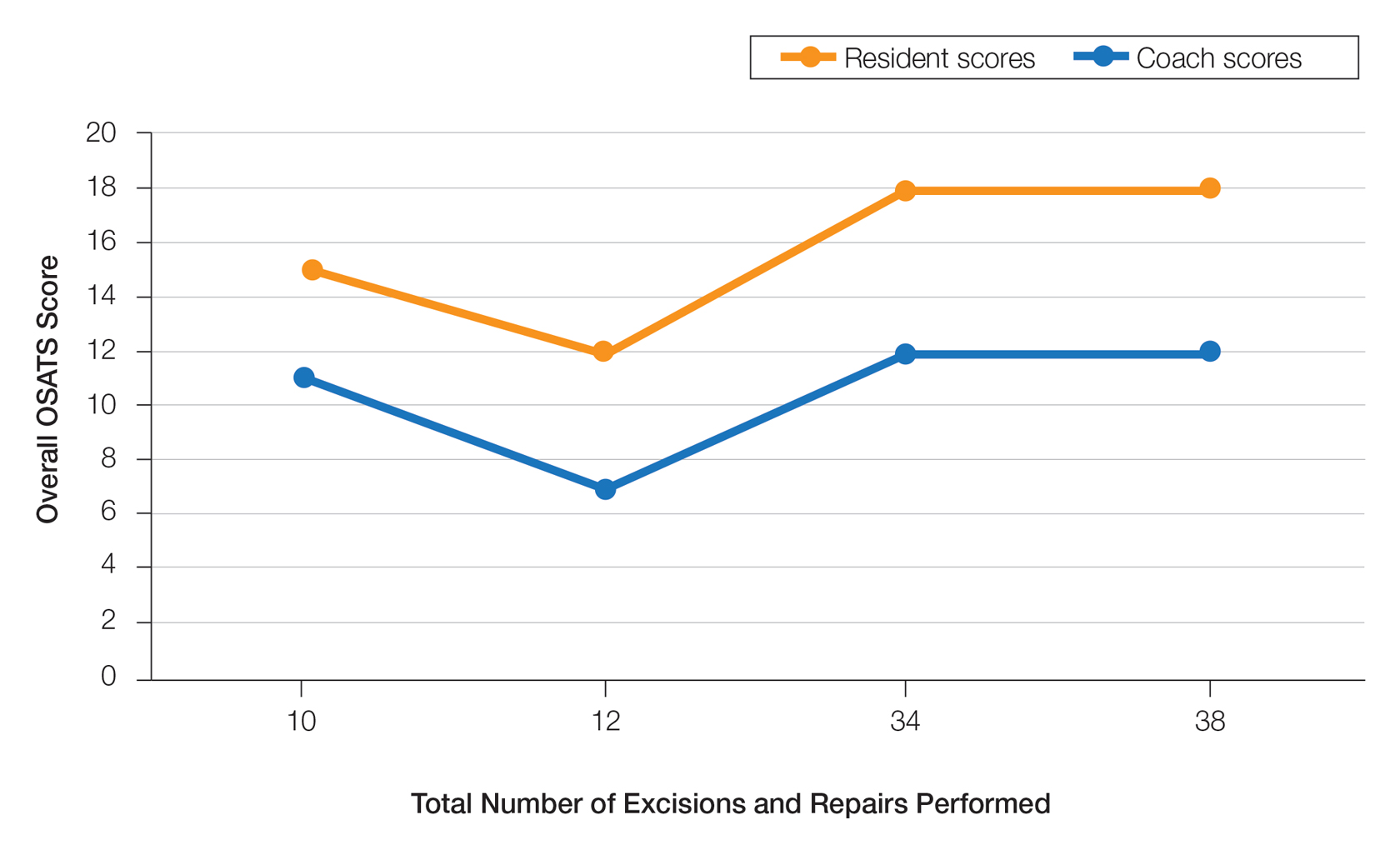

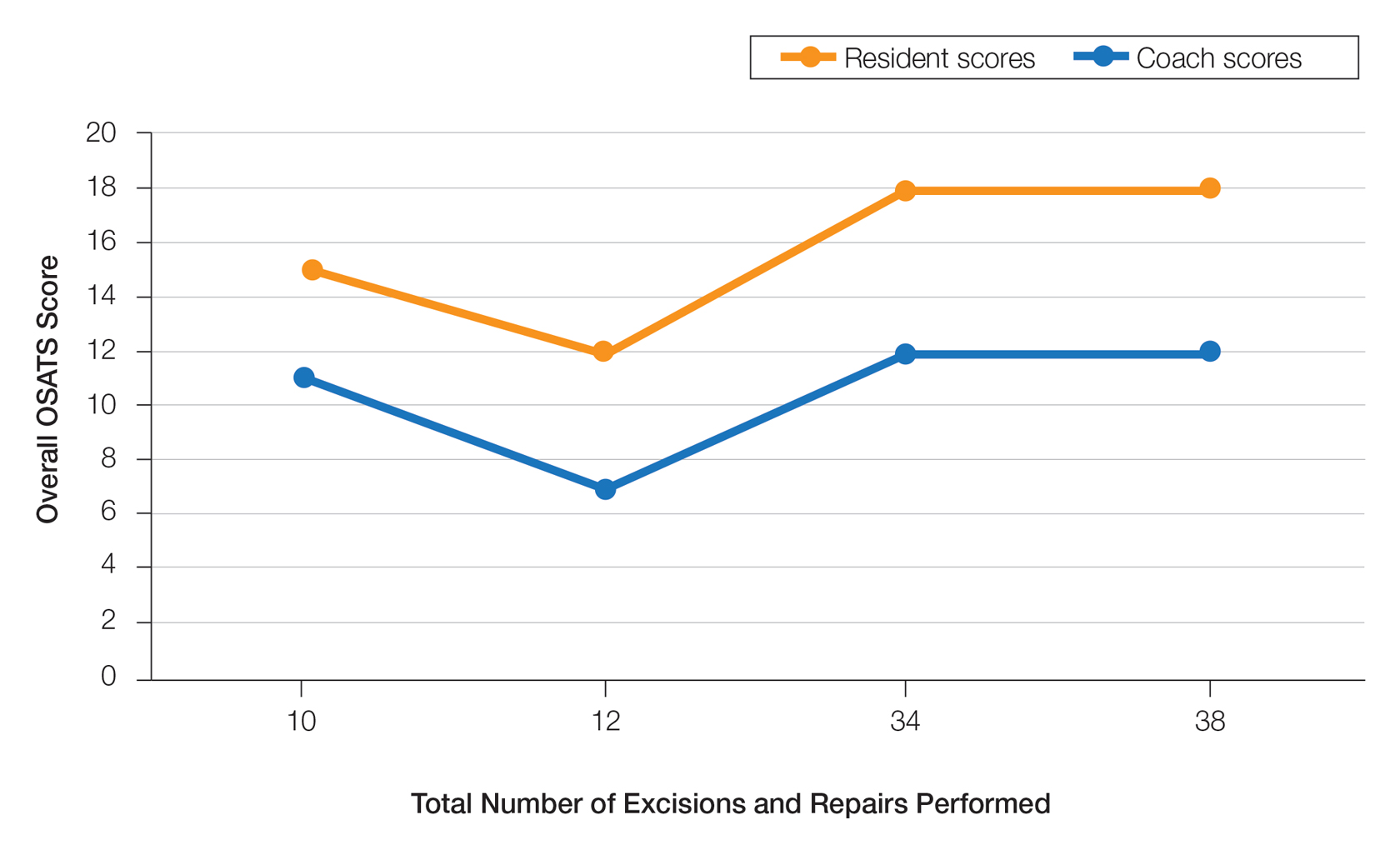

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Video-based coaching (VBC) for surgical procedures is an up-and-coming form of medical education that allows a “coach” to provide thoughtful and in-depth feedback while reviewing a recording with the surgeon in a private setting. This format has potential utility in teaching dermatology resident surgeons being coached by a dermatology faculty member.

- We performed a pilot study demonstrating that VBC can be performed easily with a minimal time investment for both the surgeon and the coach. Dermatology residents not only felt that VBC was an effective teaching method but also should become a formal part of their education.