User login

Healthy infant with a blistering rash

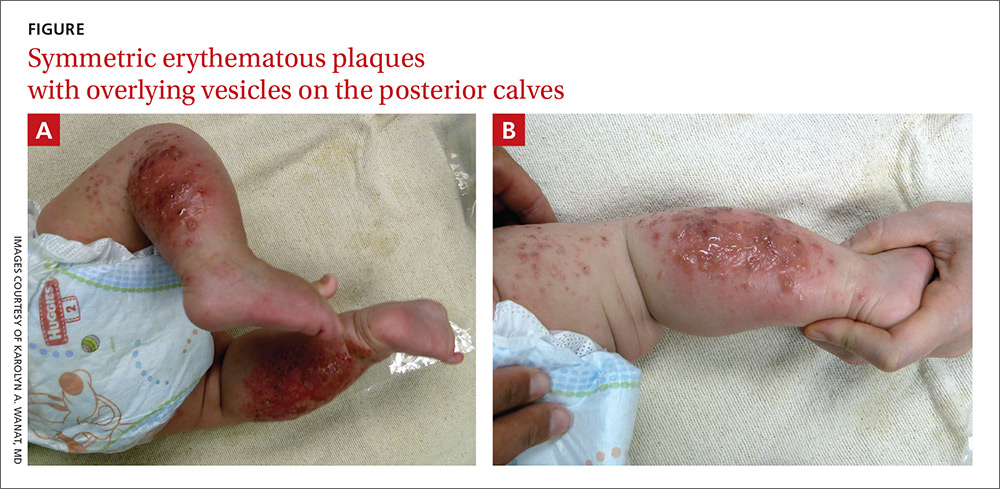

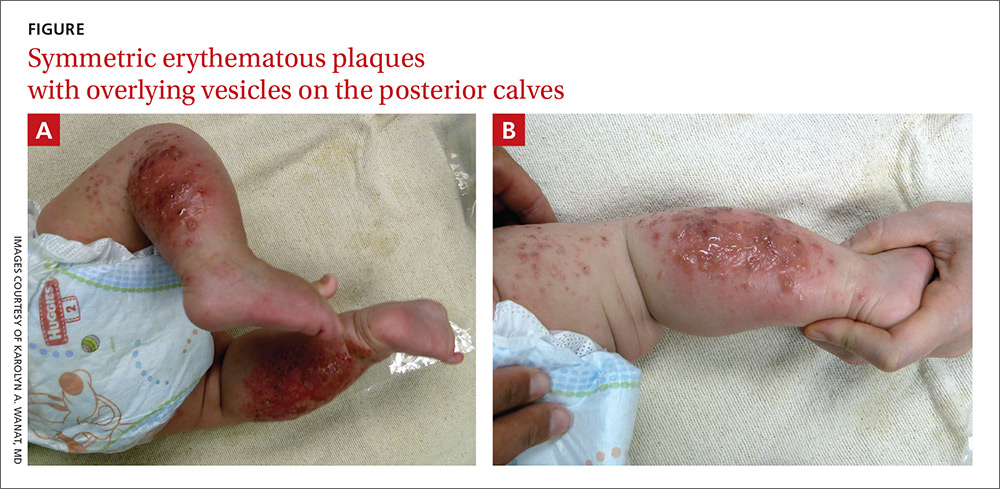

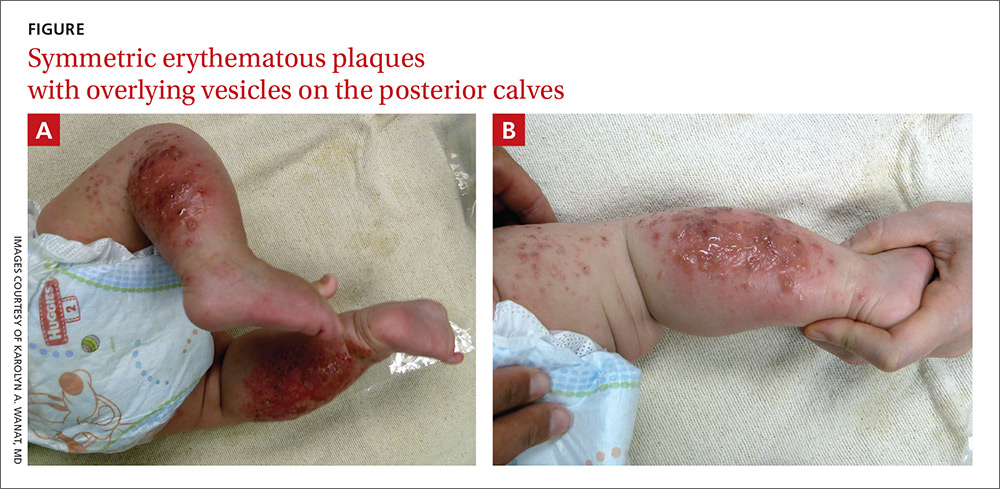

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

Pruritic Papules on the Scalp and Arms

Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) that occurs mostly in adults with a male predilection. The disease clinically favors the head and neck. Patients commonly present with pruritic papules that often are grouped, alopecia, and frequent secondary bacterial infections. Less commonly patients present with acneiform lesions and mucinorrhea. Patients often experience more pruritus in FMF than in classic MF, which can provide a good means of assessing disease activity. Disease-specific 5-year survival is approximately 70% to 80%, which is worse than classic plaque-stage MF and similar to tumor-stage MF.1

Treatment of FMF differs from classic MF in that the lesions are less responsive to skin-targeted therapies due to the perifollicular nature of dermal infiltrates. Superficial skin lesions can be treated with psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy. Other options include PUVA in combination with interferon alfa or retinoids and local radiotherapy for solitary thick tumors; however, in patients who have more infiltrative skin lesions or had PUVA therapy that failed, total skin electron beam therapy may be required.2

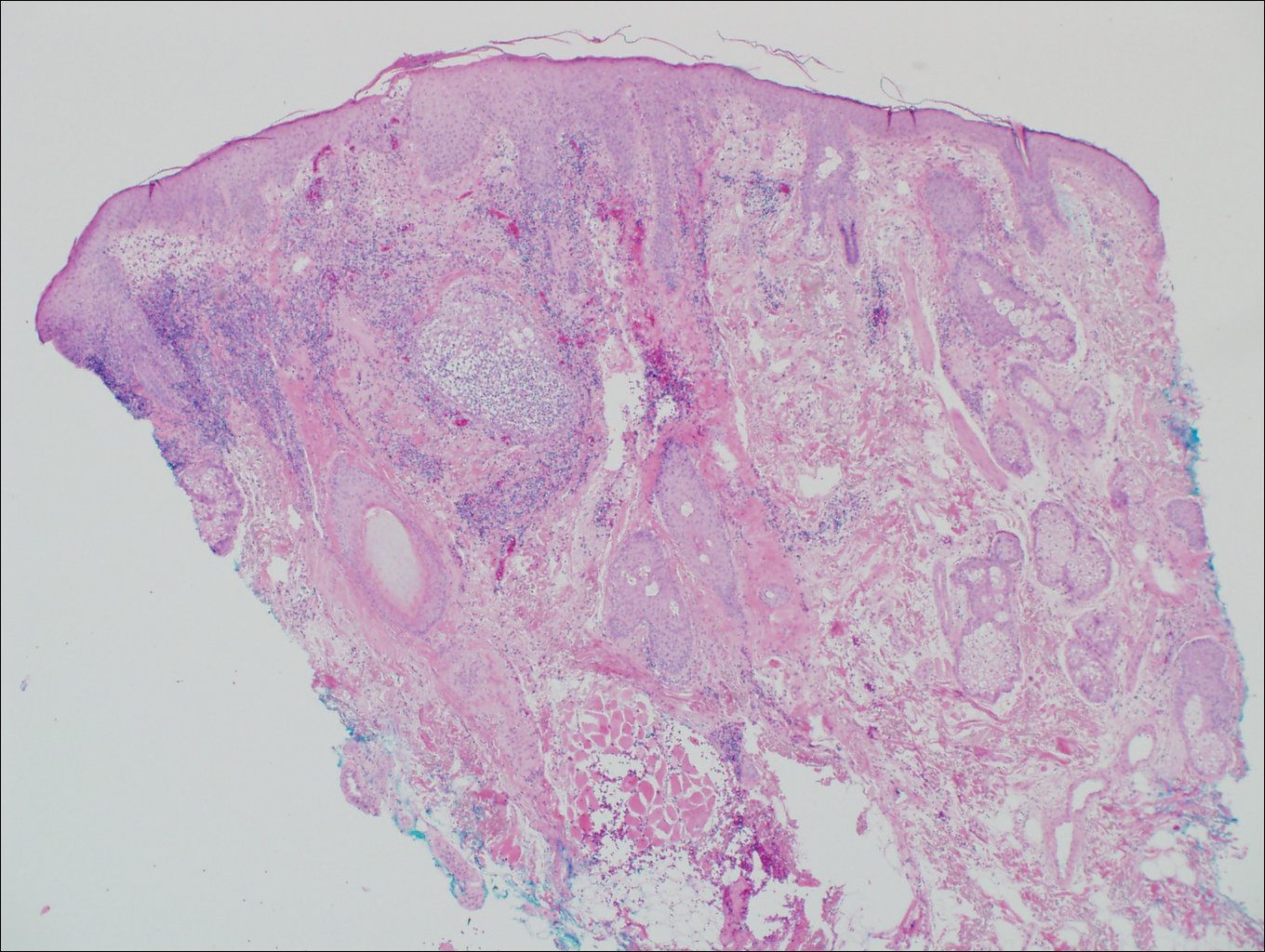

On histologic examination, there typically is perivascular and periadnexal localization of dermal infiltrates with varied involvement of the follicular epithelium and damage to hair follicles by atypical small, medium, and large hyperchromatic lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei. Mucinous degeneration of the follicular epithelium can be seen, as highlighted on Alcian blue staining, and a mixed infiltrate of eosinophils and plasma cells often is present (quiz image and Figure 1). Frequent sparing of the epidermis is noteworthy.2-4 In most cases, the neoplastic T lymphocytes are characterized by a CD3+CD4+CD8-immunophenotype as is seen in classic MF. Sometimes an admixture of CD30+ blast cells is seen.1

Histologic differential considerations for FMF include eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF), primary follicular mucinosis, lupus erythematosus, and pityrosporum folliculitis.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis has several clinical subtypes, such as classic Ofuji disease and immunosuppression-associated EPF secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. Histologically, EPF is characterized by spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium with exocytosis of a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils extending from the sebaceous gland and its duct to the infundibulum with formation of hallmark eosinophilic pustules (Figure 2). Infiltration of neutrophils in inflamed lesions generally is seen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an important differential for FMF, as follicular mucinosis has been observed in lesions of EPF.5 Both EPF and FMF can exhibit eosinophils and lymphocytes in the upper dermis, spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium, and mucinous degeneration of follicles,6 though lymphocytic atypia and relatively fewer eosinophils are suggestive of the latter.

Primary follicular mucinosis (PFM) tends to occur as a solitary lesion in younger female patients in contrast to the multiple lesions that typically appear in older male patients with FMF. Histologically, PFM usually manifests as large, cystic, mucin-filled spaces and polyclonal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate without notable cellular atypia or epidermotropism (Figure 3). Because follicular mucinosis is a common feature of FMF, its distinction from PFM can be challenging and often is aided by the absence of cellular atypia and relatively mild lymphocytic infiltrate in the latter.7

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus with its characteristic folliculocentric lymphocytic infiltration and associated dermal mucin also qualifies as a potential differential possibility for FMF; however, the perivascular and periadnexal pattern of lymphocytic infiltration as well as the localization of mucin to the reticular dermal interstitium8,9 are key histopathologic distinctions (Figure 4). Furthermore, although the histologic presentation of lupus erythematosus can be variable, it also classically shows interface dermatitis, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is the most common cause of fungal folliculitis and is caused by the Malassezia species. On histology, there typically is an unremarkable epithelium with plugged follicles and suppurative folliculitis. Serial sections of the biopsy specimen often are required to identify dilated, follicle-containing, budding yeast cells (Figure 5). Organisms are located predominantly within the infundibulum and orifice of follicular lumen, are positive for periodic acid-Schiff, and are diastase resistant.10

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides, a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis. a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198.

- DeBloom J 2nd, Severson J, Gaspari A, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:318-324.

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525-530.

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423.

- Lee JY, Tsai YM, Sheu HM. Ofuji's disease with follicular mucinosis and its differential diagnosis from alopecia mucinosa. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:307-313.

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19.

- Vincent JG, Chan MP. Specificity of dermal mucin in the diagnosis of lupus erythematosus: comparison with other dermatitides and normal skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:722-729.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

- Durdu M, Ilkit M. First step in the differential diagnosis of folliculitis: cytology. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013;39:9-25.

Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) that occurs mostly in adults with a male predilection. The disease clinically favors the head and neck. Patients commonly present with pruritic papules that often are grouped, alopecia, and frequent secondary bacterial infections. Less commonly patients present with acneiform lesions and mucinorrhea. Patients often experience more pruritus in FMF than in classic MF, which can provide a good means of assessing disease activity. Disease-specific 5-year survival is approximately 70% to 80%, which is worse than classic plaque-stage MF and similar to tumor-stage MF.1

Treatment of FMF differs from classic MF in that the lesions are less responsive to skin-targeted therapies due to the perifollicular nature of dermal infiltrates. Superficial skin lesions can be treated with psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy. Other options include PUVA in combination with interferon alfa or retinoids and local radiotherapy for solitary thick tumors; however, in patients who have more infiltrative skin lesions or had PUVA therapy that failed, total skin electron beam therapy may be required.2

On histologic examination, there typically is perivascular and periadnexal localization of dermal infiltrates with varied involvement of the follicular epithelium and damage to hair follicles by atypical small, medium, and large hyperchromatic lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei. Mucinous degeneration of the follicular epithelium can be seen, as highlighted on Alcian blue staining, and a mixed infiltrate of eosinophils and plasma cells often is present (quiz image and Figure 1). Frequent sparing of the epidermis is noteworthy.2-4 In most cases, the neoplastic T lymphocytes are characterized by a CD3+CD4+CD8-immunophenotype as is seen in classic MF. Sometimes an admixture of CD30+ blast cells is seen.1

Histologic differential considerations for FMF include eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF), primary follicular mucinosis, lupus erythematosus, and pityrosporum folliculitis.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis has several clinical subtypes, such as classic Ofuji disease and immunosuppression-associated EPF secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. Histologically, EPF is characterized by spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium with exocytosis of a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils extending from the sebaceous gland and its duct to the infundibulum with formation of hallmark eosinophilic pustules (Figure 2). Infiltration of neutrophils in inflamed lesions generally is seen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an important differential for FMF, as follicular mucinosis has been observed in lesions of EPF.5 Both EPF and FMF can exhibit eosinophils and lymphocytes in the upper dermis, spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium, and mucinous degeneration of follicles,6 though lymphocytic atypia and relatively fewer eosinophils are suggestive of the latter.

Primary follicular mucinosis (PFM) tends to occur as a solitary lesion in younger female patients in contrast to the multiple lesions that typically appear in older male patients with FMF. Histologically, PFM usually manifests as large, cystic, mucin-filled spaces and polyclonal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate without notable cellular atypia or epidermotropism (Figure 3). Because follicular mucinosis is a common feature of FMF, its distinction from PFM can be challenging and often is aided by the absence of cellular atypia and relatively mild lymphocytic infiltrate in the latter.7

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus with its characteristic folliculocentric lymphocytic infiltration and associated dermal mucin also qualifies as a potential differential possibility for FMF; however, the perivascular and periadnexal pattern of lymphocytic infiltration as well as the localization of mucin to the reticular dermal interstitium8,9 are key histopathologic distinctions (Figure 4). Furthermore, although the histologic presentation of lupus erythematosus can be variable, it also classically shows interface dermatitis, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is the most common cause of fungal folliculitis and is caused by the Malassezia species. On histology, there typically is an unremarkable epithelium with plugged follicles and suppurative folliculitis. Serial sections of the biopsy specimen often are required to identify dilated, follicle-containing, budding yeast cells (Figure 5). Organisms are located predominantly within the infundibulum and orifice of follicular lumen, are positive for periodic acid-Schiff, and are diastase resistant.10

Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) that occurs mostly in adults with a male predilection. The disease clinically favors the head and neck. Patients commonly present with pruritic papules that often are grouped, alopecia, and frequent secondary bacterial infections. Less commonly patients present with acneiform lesions and mucinorrhea. Patients often experience more pruritus in FMF than in classic MF, which can provide a good means of assessing disease activity. Disease-specific 5-year survival is approximately 70% to 80%, which is worse than classic plaque-stage MF and similar to tumor-stage MF.1

Treatment of FMF differs from classic MF in that the lesions are less responsive to skin-targeted therapies due to the perifollicular nature of dermal infiltrates. Superficial skin lesions can be treated with psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy. Other options include PUVA in combination with interferon alfa or retinoids and local radiotherapy for solitary thick tumors; however, in patients who have more infiltrative skin lesions or had PUVA therapy that failed, total skin electron beam therapy may be required.2

On histologic examination, there typically is perivascular and periadnexal localization of dermal infiltrates with varied involvement of the follicular epithelium and damage to hair follicles by atypical small, medium, and large hyperchromatic lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei. Mucinous degeneration of the follicular epithelium can be seen, as highlighted on Alcian blue staining, and a mixed infiltrate of eosinophils and plasma cells often is present (quiz image and Figure 1). Frequent sparing of the epidermis is noteworthy.2-4 In most cases, the neoplastic T lymphocytes are characterized by a CD3+CD4+CD8-immunophenotype as is seen in classic MF. Sometimes an admixture of CD30+ blast cells is seen.1

Histologic differential considerations for FMF include eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF), primary follicular mucinosis, lupus erythematosus, and pityrosporum folliculitis.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis has several clinical subtypes, such as classic Ofuji disease and immunosuppression-associated EPF secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. Histologically, EPF is characterized by spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium with exocytosis of a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils extending from the sebaceous gland and its duct to the infundibulum with formation of hallmark eosinophilic pustules (Figure 2). Infiltration of neutrophils in inflamed lesions generally is seen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an important differential for FMF, as follicular mucinosis has been observed in lesions of EPF.5 Both EPF and FMF can exhibit eosinophils and lymphocytes in the upper dermis, spongiosis of the hair follicle epithelium, and mucinous degeneration of follicles,6 though lymphocytic atypia and relatively fewer eosinophils are suggestive of the latter.

Primary follicular mucinosis (PFM) tends to occur as a solitary lesion in younger female patients in contrast to the multiple lesions that typically appear in older male patients with FMF. Histologically, PFM usually manifests as large, cystic, mucin-filled spaces and polyclonal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate without notable cellular atypia or epidermotropism (Figure 3). Because follicular mucinosis is a common feature of FMF, its distinction from PFM can be challenging and often is aided by the absence of cellular atypia and relatively mild lymphocytic infiltrate in the latter.7

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus with its characteristic folliculocentric lymphocytic infiltration and associated dermal mucin also qualifies as a potential differential possibility for FMF; however, the perivascular and periadnexal pattern of lymphocytic infiltration as well as the localization of mucin to the reticular dermal interstitium8,9 are key histopathologic distinctions (Figure 4). Furthermore, although the histologic presentation of lupus erythematosus can be variable, it also classically shows interface dermatitis, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging.

Pityrosporum folliculitis is the most common cause of fungal folliculitis and is caused by the Malassezia species. On histology, there typically is an unremarkable epithelium with plugged follicles and suppurative folliculitis. Serial sections of the biopsy specimen often are required to identify dilated, follicle-containing, budding yeast cells (Figure 5). Organisms are located predominantly within the infundibulum and orifice of follicular lumen, are positive for periodic acid-Schiff, and are diastase resistant.10

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides, a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis. a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198.

- DeBloom J 2nd, Severson J, Gaspari A, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:318-324.

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525-530.

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423.

- Lee JY, Tsai YM, Sheu HM. Ofuji's disease with follicular mucinosis and its differential diagnosis from alopecia mucinosa. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:307-313.

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19.

- Vincent JG, Chan MP. Specificity of dermal mucin in the diagnosis of lupus erythematosus: comparison with other dermatitides and normal skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:722-729.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

- Durdu M, Ilkit M. First step in the differential diagnosis of folliculitis: cytology. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013;39:9-25.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides, a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis. a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198.

- DeBloom J 2nd, Severson J, Gaspari A, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:318-324.

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525-530.

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423.

- Lee JY, Tsai YM, Sheu HM. Ofuji's disease with follicular mucinosis and its differential diagnosis from alopecia mucinosa. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:307-313.

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19.

- Vincent JG, Chan MP. Specificity of dermal mucin in the diagnosis of lupus erythematosus: comparison with other dermatitides and normal skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:722-729.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

- Durdu M, Ilkit M. First step in the differential diagnosis of folliculitis: cytology. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013;39:9-25.

A 60-year-old man presented with a 3-month history of itchy bumps on the scalp and arms. He also noticed some patches of hair loss in these areas. He had no history of other skin conditions and was otherwise healthy with no other medical comorbidities.