User login

North American Blastomycosis in an Immunocompromised Patient

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

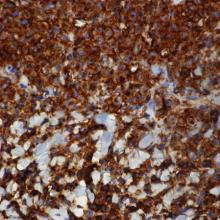

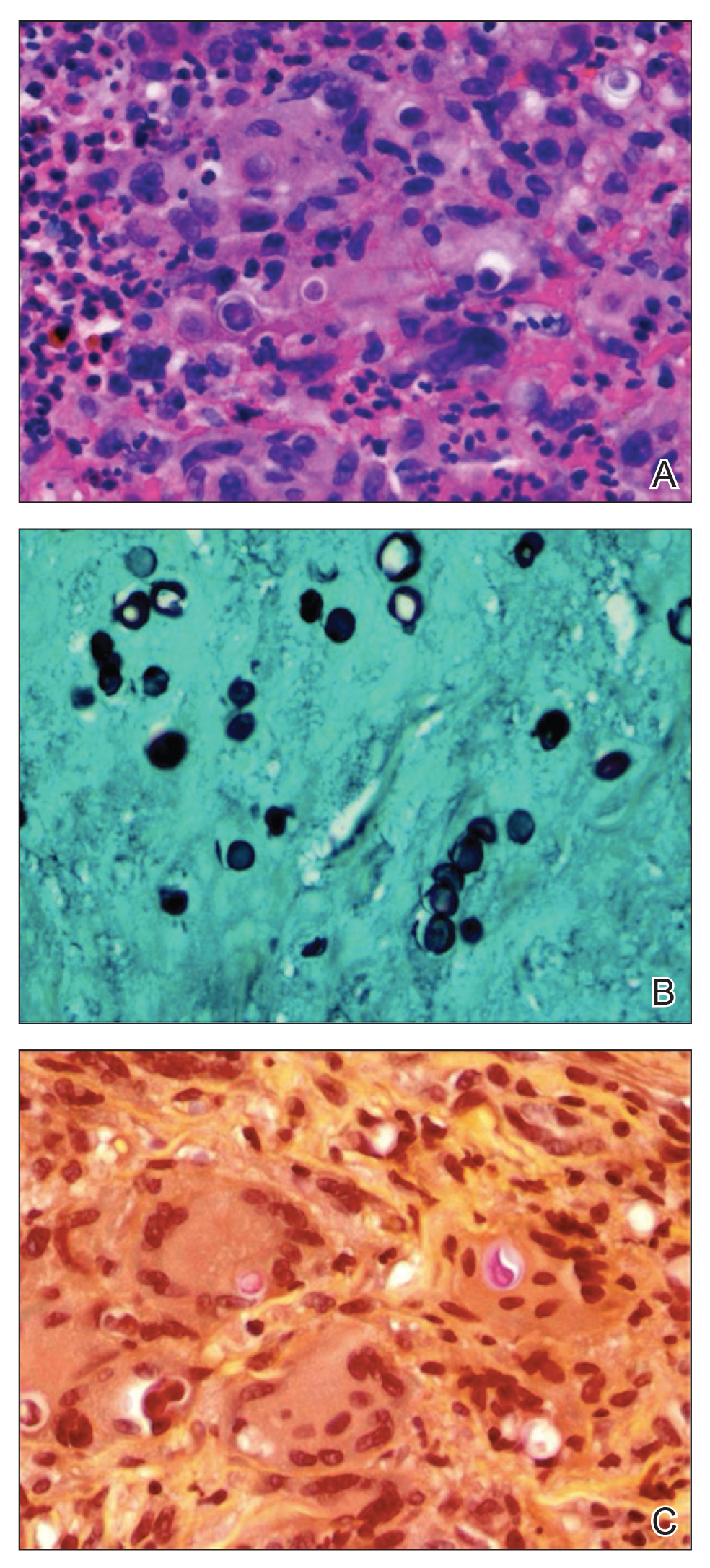

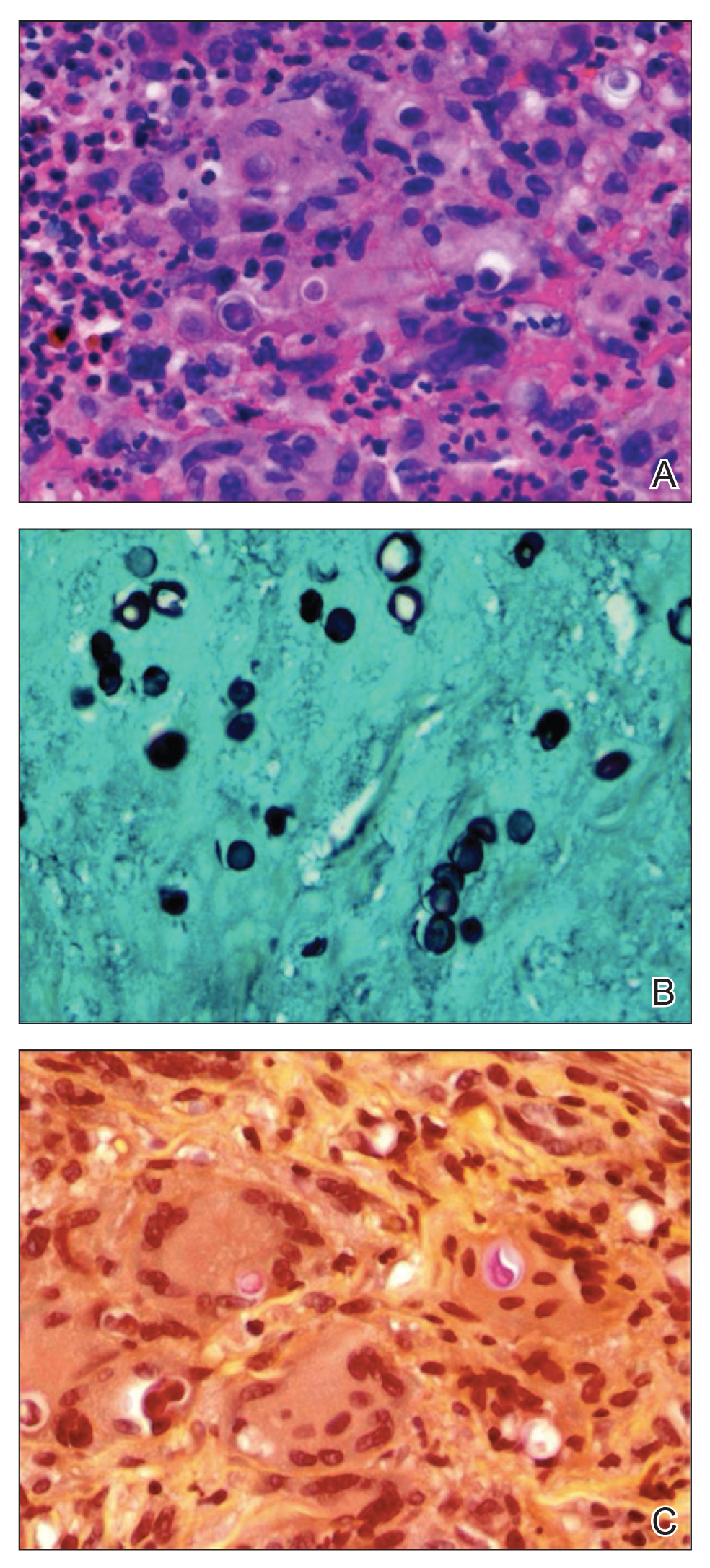

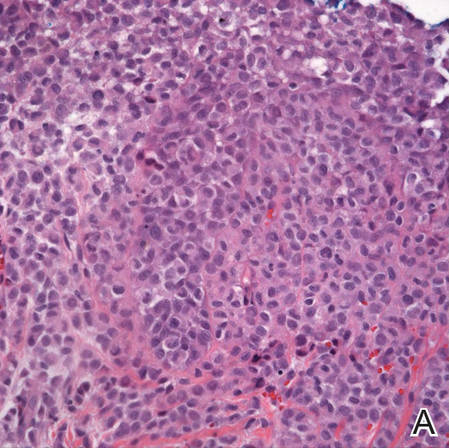

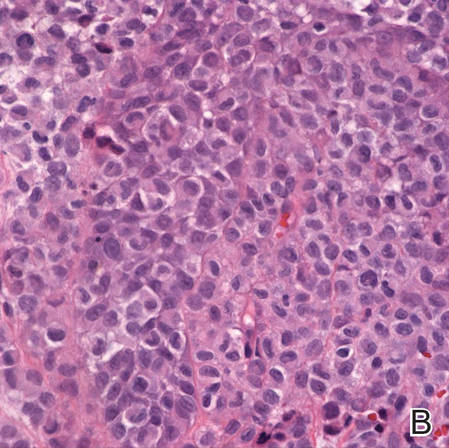

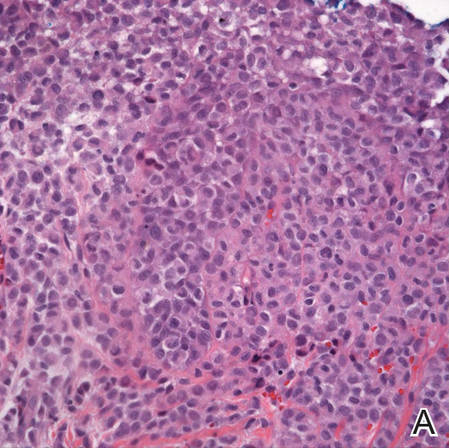

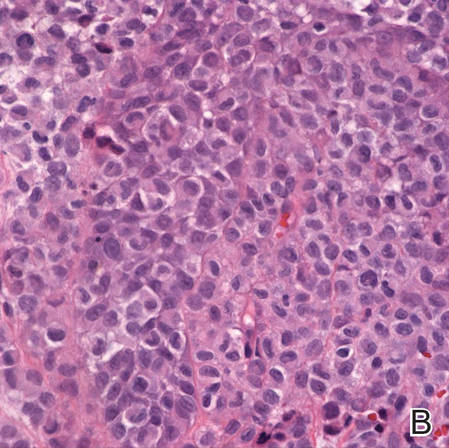

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2

Treatment

Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent. There are no randomized, blinded trials comparing antifungal agents, and data on the treatment of blastomycosis in patients infected with HIV are limited. Amphotericin B 3 mg/kg every 24 hours is recommended in life-threatening systemic disease and CNS disease as well as in patients with immune suppression, including AIDS.4 In a retrospective study of 326 patients with blastomycosis, those receiving amphotericin B had a cure rate of 86.5% with a relapse rate of 3.9%; patients receiving ketoconazole had a cure rate of 81.7% with a relapse rate of 14%.4 Although data are limited, chronic suppressive therapy generally is recommended in patients with HIV who have been treated for blastomycosis. Fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole are all used as chronic suppressive therapy; however, given the higher relapse rate observed with ketoconazole, itraconazole is preferred. Because neither ketoconazole nor itraconazole penetrates the blood-brain barrier, these drugs are not recommended in cases of CNS involvement. Patients with CNS disease or intolerance to itraconazole should be treated with fluconazole for chronic suppression.3

- Wheat J, Wheat H, Connolly P, et al. Cross-reactivity in Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen assays of urine samples from patients with endemic mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1169-1171.

- Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:847-853.

- Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310-1316. Cited by: Aberg JA. Blastomycosis and HIV. HIV In Site Knowledge Base Chapter. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-05-02-09#SIX. Published April 2003. Updated January 2006. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- Chapman SW, Bradsher RW Jr, Campbell GD Jr, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679-683.

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2

Treatment

Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent. There are no randomized, blinded trials comparing antifungal agents, and data on the treatment of blastomycosis in patients infected with HIV are limited. Amphotericin B 3 mg/kg every 24 hours is recommended in life-threatening systemic disease and CNS disease as well as in patients with immune suppression, including AIDS.4 In a retrospective study of 326 patients with blastomycosis, those receiving amphotericin B had a cure rate of 86.5% with a relapse rate of 3.9%; patients receiving ketoconazole had a cure rate of 81.7% with a relapse rate of 14%.4 Although data are limited, chronic suppressive therapy generally is recommended in patients with HIV who have been treated for blastomycosis. Fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole are all used as chronic suppressive therapy; however, given the higher relapse rate observed with ketoconazole, itraconazole is preferred. Because neither ketoconazole nor itraconazole penetrates the blood-brain barrier, these drugs are not recommended in cases of CNS involvement. Patients with CNS disease or intolerance to itraconazole should be treated with fluconazole for chronic suppression.3

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2

Treatment

Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent. There are no randomized, blinded trials comparing antifungal agents, and data on the treatment of blastomycosis in patients infected with HIV are limited. Amphotericin B 3 mg/kg every 24 hours is recommended in life-threatening systemic disease and CNS disease as well as in patients with immune suppression, including AIDS.4 In a retrospective study of 326 patients with blastomycosis, those receiving amphotericin B had a cure rate of 86.5% with a relapse rate of 3.9%; patients receiving ketoconazole had a cure rate of 81.7% with a relapse rate of 14%.4 Although data are limited, chronic suppressive therapy generally is recommended in patients with HIV who have been treated for blastomycosis. Fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole are all used as chronic suppressive therapy; however, given the higher relapse rate observed with ketoconazole, itraconazole is preferred. Because neither ketoconazole nor itraconazole penetrates the blood-brain barrier, these drugs are not recommended in cases of CNS involvement. Patients with CNS disease or intolerance to itraconazole should be treated with fluconazole for chronic suppression.3

- Wheat J, Wheat H, Connolly P, et al. Cross-reactivity in Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen assays of urine samples from patients with endemic mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1169-1171.

- Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:847-853.

- Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310-1316. Cited by: Aberg JA. Blastomycosis and HIV. HIV In Site Knowledge Base Chapter. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-05-02-09#SIX. Published April 2003. Updated January 2006. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- Chapman SW, Bradsher RW Jr, Campbell GD Jr, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679-683.

- Wheat J, Wheat H, Connolly P, et al. Cross-reactivity in Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen assays of urine samples from patients with endemic mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1169-1171.

- Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:847-853.

- Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310-1316. Cited by: Aberg JA. Blastomycosis and HIV. HIV In Site Knowledge Base Chapter. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-05-02-09#SIX. Published April 2003. Updated January 2006. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- Chapman SW, Bradsher RW Jr, Campbell GD Jr, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679-683.

Practice Points

- Blastomycosis generally produces a pulmonary form of the disease and, to a lesser extent, extrapulmonary forms, such as cutaneous, osteoarticular, and genitourinary.

- Blastomycosis can be diagnosed by culture, direct visualization of the yeast in affected tissue, antigen testing, or a combination of these methods.

- After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period.

Collagenous and Elastotic Marginal Plaques of the Hands

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

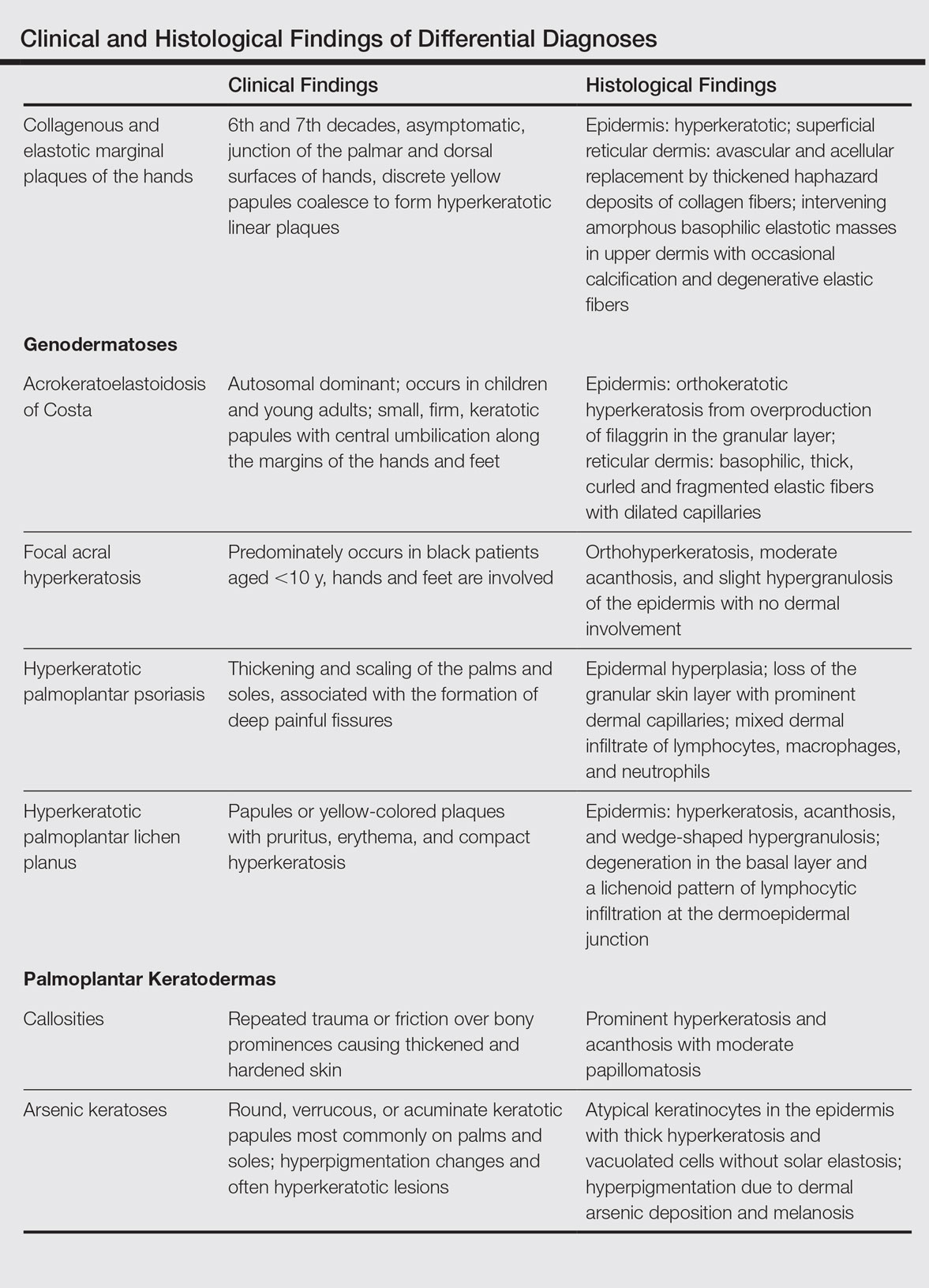

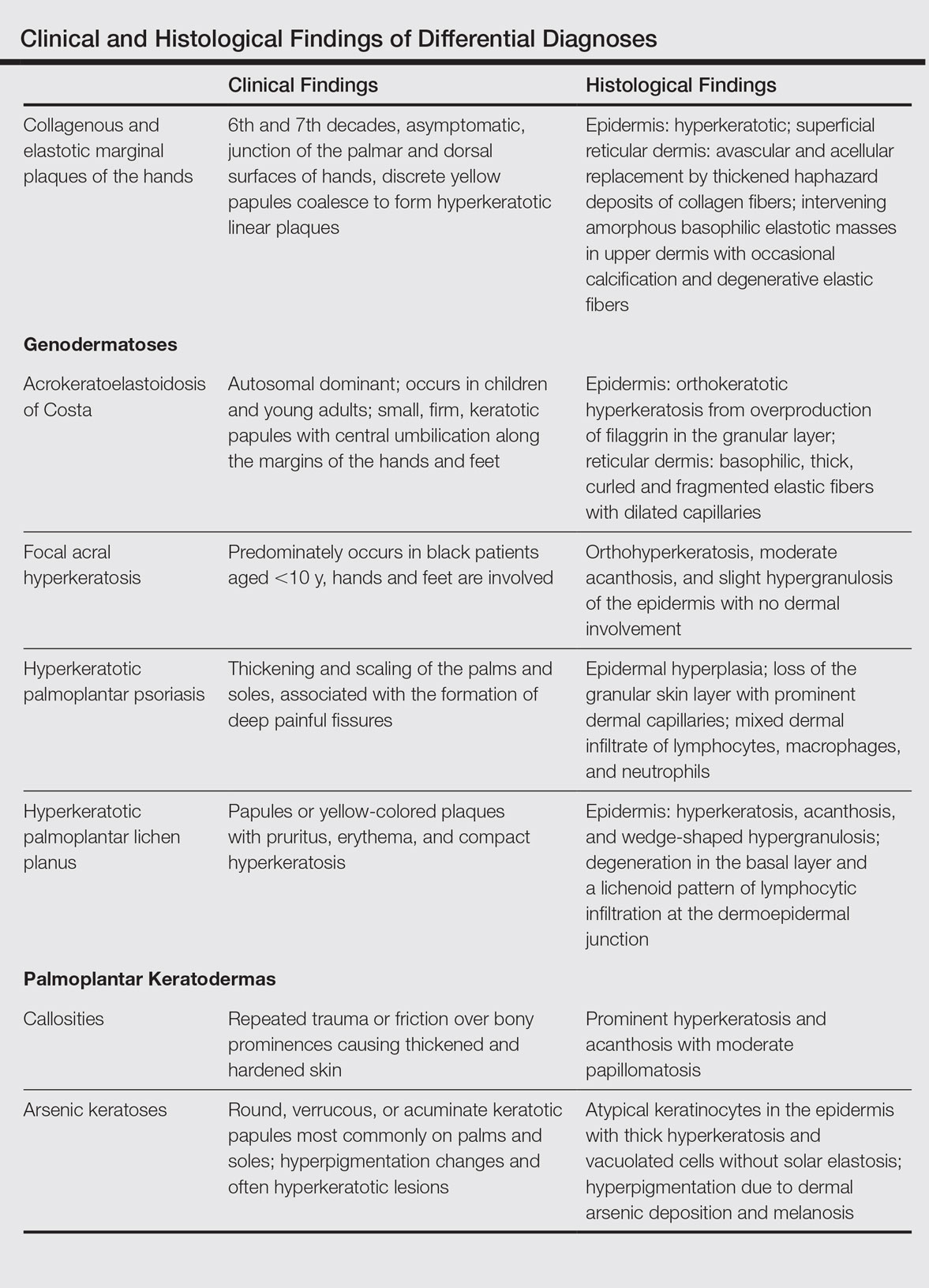

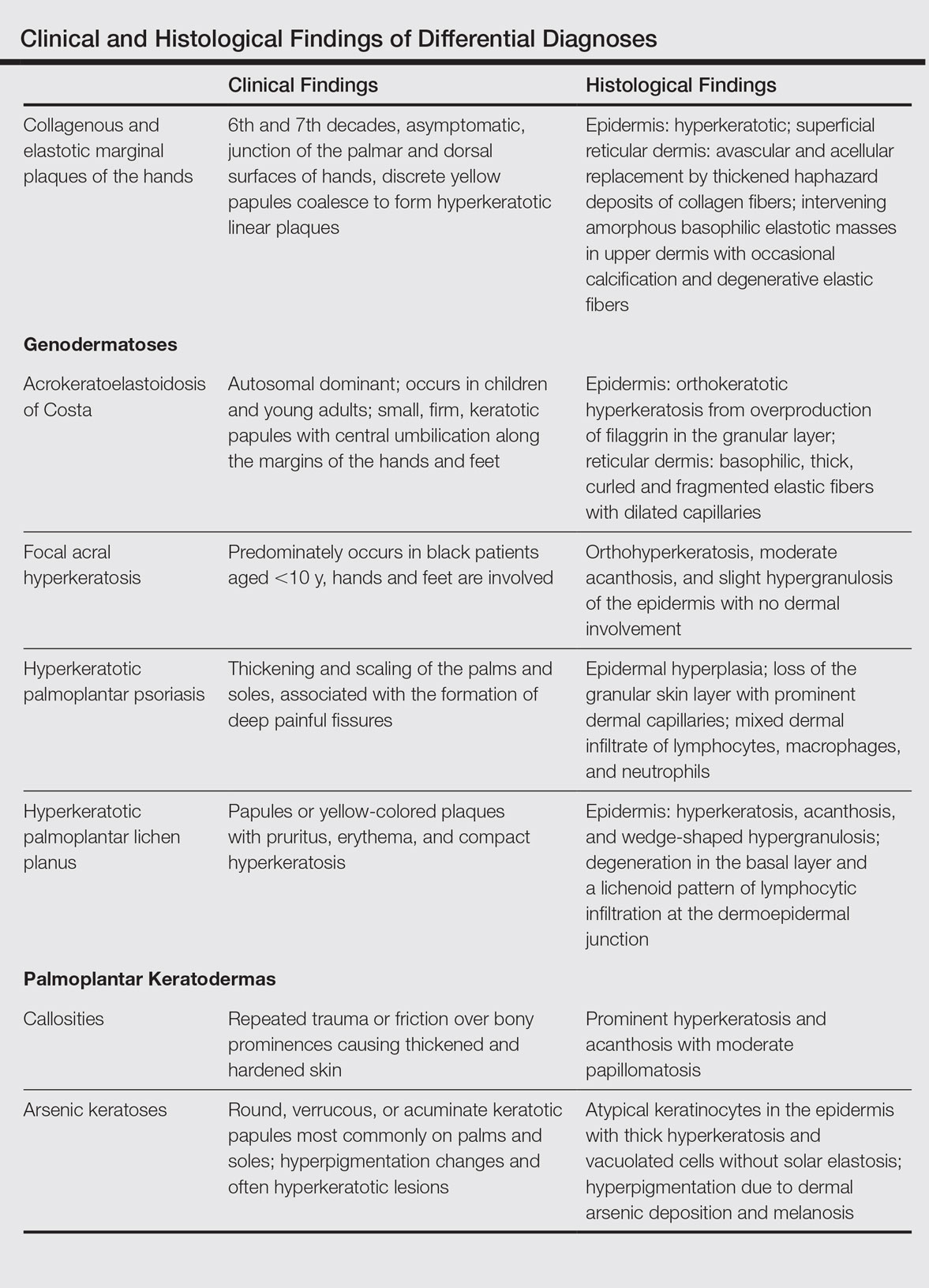

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

Practice Points

- The etiology of collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.

- It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It should be separated from other diseases and avoid being misdiagnosed as a malignant lesion.

Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis: An Underreported Entity

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as histiocytosis X, is a general term that describes a group of rare disorders characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells.1 Central to immune surveillance and the elimination of foreign substances from the body, Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and found in the epidermis but are capable of migrating from the skin to the lymph nodes. In LCH, these cells congregate on bone tissue, particularly in the head and neck region, causing a multitude of problems.2

The spectrum of LCH includes 4 variants: congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHR)(also known as Hashimoto-Pritzker disease), Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (also known as pulmonary histiocytosis X)(Table). Despite the various clinical presentations and levels of severity, all variants are caused by the proliferation of Langerhans cells. We present a case of CSHR in a 6-month-old male infant that was initially diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum. We believe the actual incidence of CSHR may be underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition.

Case Report

A 6-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic by his pediatrician with a generalized cutaneous eruption of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption, which followed a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection, was characterized by multiple flesh-colored to erythematous, umbilicated papules distributed along the postauricular region, scalp (Figure 1A), abdomen (Figure 1B), and anterior aspect of the neck. Due to his recent illness, the patient was diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by the referring pediatrician that was treated symptomatically with hydrocortisone lotion, Schamberg’s cream formulated in our office (a compound mixture of zinc oxide, menthol, calcium hydroxide solution, and olive oil), and pediatric diphenhydramine as needed. During a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, a more potent topical corticosteroid and a low-dose systemic corticosteroid was prescribed for 1 week due to development of new lesions and exacerbation of existing lesions. On follow-up 1 week later, the lesions on the trunk had improved, but the patient had developed new lesions on the scalp that differed from prior findings in that they were darker (more erythematous to brown) and firmer (papules and nodules).

|

| |

Figure 1. Multiple fleshcolored to erythematous, umbilicated papules on the frontal scalp (A) and erythematous papules on the abdomen (B). | ||

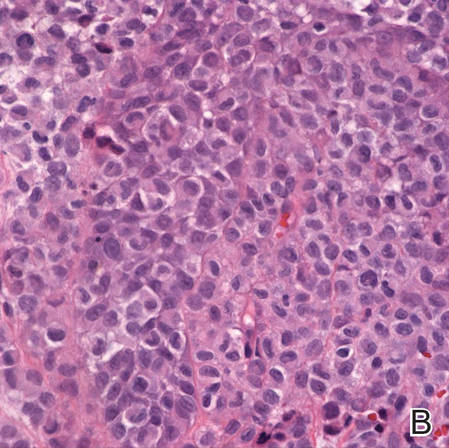

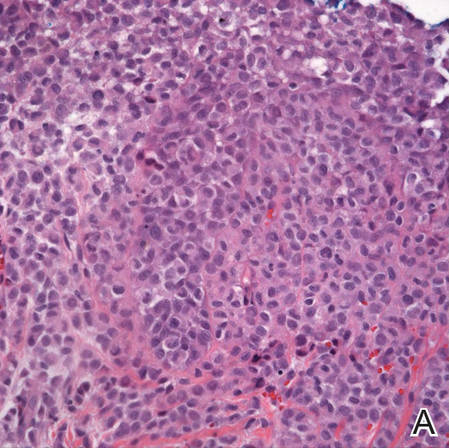

A shave biopsy was obtained from the frontal scalp to rule out LCH. Histologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen revealed an atypical cellular infiltrate effacing the dermoepidermal junction and extensive epidermotropism. Focal erosion of the epidermis and an acute inflammatory exudate were visible. The nuclei of the cellular infiltrate were enlarged and hyperchromatic with a characteristic reniform appearance and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). The cells were admixed with scattered eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells.

|

| |

Figure 2. Low-power view of dermal mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100), and high-power view of enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with a characteristic reniform appearance admixed with eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells (B) (H&E, original magnification ×400). | ||

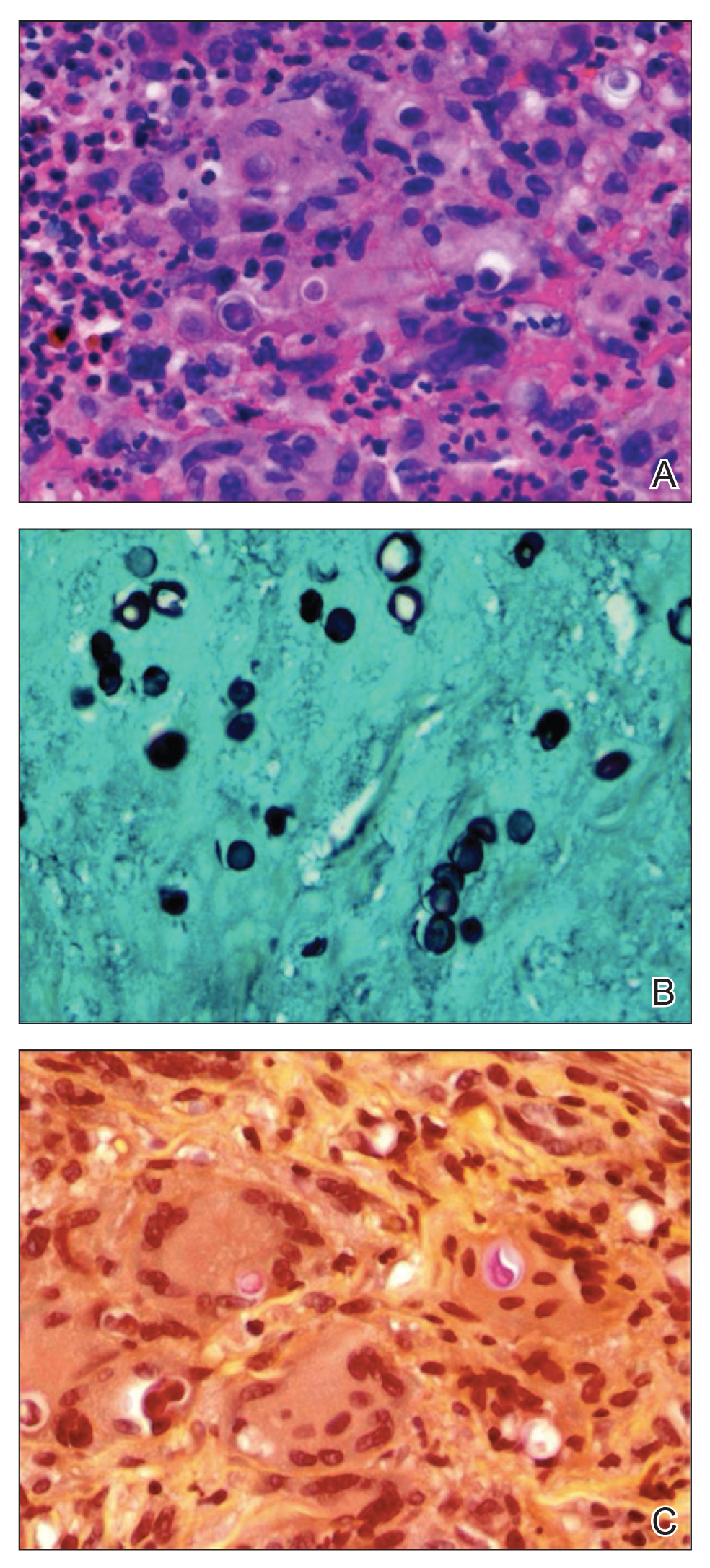

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was strongly positive for both CD1a and S-100 expression (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with LCH. Clinicopathologic correlation strongly favored the diagnosis of CSHR.

Comment

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, benign, congenital variant of LCH that spontaneously resolves with no systemic involvement. The more aggressive forms typically manifest at birth or during the first 2 months of life and regress within 3 to 4 months.5 Since CSHR was first described in 1973 by Hashimoto and Pritzker,5 more than 100 cases have been reported, but the true incidence is believed to be higher than reported given the high rate of spontaneous resolution and the low rate of clinical recognition.2 The first reported case of CSHR occurred in a female infant who presented at birth with multiple, diffusely distributed, red-brown papules that were 2 to 4 mm in diameter. Although the patient received no treatment, the exanthem completely resolved within 3.5 months without recurrence at 14-year follow-up.5 Most often, CSHR presents as multiple papules or nodules with occasional disseminated crusting and is followed within a few months by a dramatic and spontaneous regression. Lesions may heal with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pseudo-Darier sign, the propensity to urticate from physical manipulation, has been reported in some lesions with an increased number of mast cells.6 Extensive superficial nasal and oral mucosal erosions have been reported in 2 cases.7 Solitary lesions have been reported in 25% of cases.8

The etiology of CSHR remains unknown, though neoplastic, viral, and immunologic origins have been suggested. There have been reports that human herpesvirus 6 may contribute to the development of LCH.9 It may be postulated that our patient’s presentation of CSHR was potentiated by his recent upper respiratory tract illness. In the literature, CSHR is distributed equally among males and females. Prevalence is higher in the white population than in other racial groups.5

Although CSHR is a benign cutaneous variant of LCH, there have been reports of patients with disseminated and extracutaneous involvement. In 1 rare case, CSHR reportedly involved the eyes, producing multiple, bilateral, well-circumscribed, diffuse, yellow-white lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium throughout the posterior pole of the eyes.10 The retinal lesions spontaneously regressed along with the skin manifestations. Additionally, it was reported that a neonate in Thailand presented with CSHR at birth and 1 month later developed multiple lung cysts that had completely regressed 11 months later.11 One study reported that initial diagnoses of LCH in 18 patients with only cutaneous involvement eventually progressed to systemic LCH, requiring further management.12 When LCH is suspected, a thorough physical examination, including hematologic and coagulation evaluation, liver function tests, musculoskeletal examination, and consultation with specialists if necessary, is recommended.13

There are 3 additional variants of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease is an acute form of LCH that accounts for 10% of all LCH cases and typically presents in children younger than 2 years. It involves multiple organs, including the bones, lungs, liver, and lymph nodes.14 Affected patients usually present with fever; hepatosplenomegaly; anemia; lymphadenopathy; extensive lytic skull lesions; and a generalized cutaneous eruption, appearing as a maculopapular scaling rash with underlying purpura on the scalp, neck, axilla, and trunk.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating a thinning of the epidermis and a collection of reticulum cells in the dermis.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is treated with radiation and chemotherapy; if left untreated, the disease is fatal.4

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic form of LCH, is most commonly seen in children aged 2 to 6 years and accounts for 15% to 20% of all LCH cases. This LCH variant presents with a classic triad of diabetes insipidus (resulting from erosion into the sella turcica), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos.15 Hand-Schüller-Christian disease also affects the oral cavity, producing nodular ulcerations of the hard palate, trouble swallowing, and halitosis.4 The involvement of lytic bone lesions of the mastoid process and petrous portions of the temporal bones may cause recurrent or chronic otitis media and otitis externa. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical excision. The mortality rate is 30%.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most prevalent variant of LCH, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases. Characterized by Langerhans cell granulomatous infiltration of the lungs and painful cystic bone lesions, eosinophilic granuloma primarily presents in the third or fourth decades of life.16 Some studies suggest an epidemiologic association with tobacco use.17 In the preliminary stages of this disease, Langerhans cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts infiltrate and form nodules on the terminal bronchioles in the upper and middle lung zones, damaging the airway walls.18 Fibrotic scarring progresses, ultimately resulting in alveolar destruction.10 The common signs and symptoms of eosinophilic granuloma are a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, spontaneous pneumothorax, fever, peripheral edema, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.14 The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma is variable. Although some patients progress to end-stage fibrotic lung disease requiring lung transplant, there have been reports of complete remission following cessation of cigarette smoking.17

Langerhans cells travel from the bone marrow to the epidermis where they express the CD1a protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell. Elevated levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukins have been seen in patients with LCH.1 Their role in the pathogenesis of this disease remains unknown, but the elevated levels of cytokines may indicate the lack of an efficient immune system.

Histologically, hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections demonstrate an infiltrate of histiocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and an increased number of mast cells involving the papillary and reticular dermis. Infiltrating Langerhans cells have concave reniform nuclei18 and stain positive for CD1a, S-100, and CD68 antigens.15 In 10% to 30% of CSHR cases, Birbeck granules can be seen on electron microscopy and tend to transform into laminated dense bodies, signifying the degenerative changes seen in CSHR.15 The various forms of LCH exhibit no significant differences in the expression of the epithelial cadherin, the phosphorylated histone H3, and the Ki-67 proteins, indicating that they are simply different forms of the same disease represented on a spectrum.15

Conclusion

The actual incidence of CSHR may be notably underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition. A subtype of LCH, CSHR is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although CSHR generally follows a benign clinical course, a thorough workup and evaluation for systemic disease with close follow-up is recommended after diagnosis due to the potential of LCH to involve multiple organs and to relapse at a later date after apparent regression.

1. Hussein MR. Skin-limited Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in children. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:504-511.

2. Nakahigashi K, Ohta M, Sakai R, et al. Late-onset self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: pediatric case of Hashimoto-Pritzker type Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:205-209.

3. Pant C, Madonia P, Bahna SL, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a case of Letterer Siwe disease. J La State Med Soc. 2009;161:211-212.

4. Ferreira LM, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Letterer-Siwe disease–the importance of dermatological diagnosis in two cases [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:405-409.

5. Hashimoto K, Pritzker MS. Electron microscopic study of reticulohistiocytoma. an unusual case of congenital, self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:263-270.

6. Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children’s Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

7. Le Bidre E, Lorette G, Delage M, et al. Extensive, erosive congenital self-healing cell histiocytosis [published online December 22, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:835-836.

8. Weiss T, Weber L, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, et al. Solitary cutaneous dendritic cell tumor in a child: role of dendritic cell markers for the diagnosis of skin Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:838-844.

9. Csire M, Mikala G, Jákó J, et al. Persistent long-term human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection in a patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis [published online July 3, 2007]. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13:157-160.

10. Zaenglein AL, Steele MA, Kamino H, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with eye involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:135-137.

11. Chunharas A, Pabunruang W, Hongeng S. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis with pulmonary involvement: spontaneous regression. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(suppl 4):S1309-S1313.

12. Minkov M, Prosch H, Steiner M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in neonates. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:802-807.

13. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291-295.

14. Stacher E, Beham-Schmid C, Terpe HJ, et al. Pulmonary histiocytic sarcoma mimicking pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a young adult presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax: a potential diagnostic pitfall [published online June 27, 2009]. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:187-190.

15. Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Monnier P, et al. Multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (Hand-Schüller-Christian disease) in an adult: a case report and review of the literature [published online October 10, 2003]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:326-330.

16. Noonan V, Kabani S, Alibhai K. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). J Mass Dent Soc. 2011;60:35.

17. Podbielski FJ, Worley TA, Korn JM, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the lung and rib. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:194-195.

18. Rosso DA, Ripoli MF, Roy A, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are elevated in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:480-483.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as histiocytosis X, is a general term that describes a group of rare disorders characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells.1 Central to immune surveillance and the elimination of foreign substances from the body, Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and found in the epidermis but are capable of migrating from the skin to the lymph nodes. In LCH, these cells congregate on bone tissue, particularly in the head and neck region, causing a multitude of problems.2

The spectrum of LCH includes 4 variants: congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHR)(also known as Hashimoto-Pritzker disease), Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (also known as pulmonary histiocytosis X)(Table). Despite the various clinical presentations and levels of severity, all variants are caused by the proliferation of Langerhans cells. We present a case of CSHR in a 6-month-old male infant that was initially diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum. We believe the actual incidence of CSHR may be underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition.

Case Report

A 6-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic by his pediatrician with a generalized cutaneous eruption of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption, which followed a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection, was characterized by multiple flesh-colored to erythematous, umbilicated papules distributed along the postauricular region, scalp (Figure 1A), abdomen (Figure 1B), and anterior aspect of the neck. Due to his recent illness, the patient was diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by the referring pediatrician that was treated symptomatically with hydrocortisone lotion, Schamberg’s cream formulated in our office (a compound mixture of zinc oxide, menthol, calcium hydroxide solution, and olive oil), and pediatric diphenhydramine as needed. During a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, a more potent topical corticosteroid and a low-dose systemic corticosteroid was prescribed for 1 week due to development of new lesions and exacerbation of existing lesions. On follow-up 1 week later, the lesions on the trunk had improved, but the patient had developed new lesions on the scalp that differed from prior findings in that they were darker (more erythematous to brown) and firmer (papules and nodules).

|

| |

Figure 1. Multiple fleshcolored to erythematous, umbilicated papules on the frontal scalp (A) and erythematous papules on the abdomen (B). | ||

A shave biopsy was obtained from the frontal scalp to rule out LCH. Histologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen revealed an atypical cellular infiltrate effacing the dermoepidermal junction and extensive epidermotropism. Focal erosion of the epidermis and an acute inflammatory exudate were visible. The nuclei of the cellular infiltrate were enlarged and hyperchromatic with a characteristic reniform appearance and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). The cells were admixed with scattered eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells.

|

| |

Figure 2. Low-power view of dermal mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100), and high-power view of enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with a characteristic reniform appearance admixed with eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells (B) (H&E, original magnification ×400). | ||

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was strongly positive for both CD1a and S-100 expression (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with LCH. Clinicopathologic correlation strongly favored the diagnosis of CSHR.

Comment

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, benign, congenital variant of LCH that spontaneously resolves with no systemic involvement. The more aggressive forms typically manifest at birth or during the first 2 months of life and regress within 3 to 4 months.5 Since CSHR was first described in 1973 by Hashimoto and Pritzker,5 more than 100 cases have been reported, but the true incidence is believed to be higher than reported given the high rate of spontaneous resolution and the low rate of clinical recognition.2 The first reported case of CSHR occurred in a female infant who presented at birth with multiple, diffusely distributed, red-brown papules that were 2 to 4 mm in diameter. Although the patient received no treatment, the exanthem completely resolved within 3.5 months without recurrence at 14-year follow-up.5 Most often, CSHR presents as multiple papules or nodules with occasional disseminated crusting and is followed within a few months by a dramatic and spontaneous regression. Lesions may heal with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pseudo-Darier sign, the propensity to urticate from physical manipulation, has been reported in some lesions with an increased number of mast cells.6 Extensive superficial nasal and oral mucosal erosions have been reported in 2 cases.7 Solitary lesions have been reported in 25% of cases.8

The etiology of CSHR remains unknown, though neoplastic, viral, and immunologic origins have been suggested. There have been reports that human herpesvirus 6 may contribute to the development of LCH.9 It may be postulated that our patient’s presentation of CSHR was potentiated by his recent upper respiratory tract illness. In the literature, CSHR is distributed equally among males and females. Prevalence is higher in the white population than in other racial groups.5

Although CSHR is a benign cutaneous variant of LCH, there have been reports of patients with disseminated and extracutaneous involvement. In 1 rare case, CSHR reportedly involved the eyes, producing multiple, bilateral, well-circumscribed, diffuse, yellow-white lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium throughout the posterior pole of the eyes.10 The retinal lesions spontaneously regressed along with the skin manifestations. Additionally, it was reported that a neonate in Thailand presented with CSHR at birth and 1 month later developed multiple lung cysts that had completely regressed 11 months later.11 One study reported that initial diagnoses of LCH in 18 patients with only cutaneous involvement eventually progressed to systemic LCH, requiring further management.12 When LCH is suspected, a thorough physical examination, including hematologic and coagulation evaluation, liver function tests, musculoskeletal examination, and consultation with specialists if necessary, is recommended.13

There are 3 additional variants of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease is an acute form of LCH that accounts for 10% of all LCH cases and typically presents in children younger than 2 years. It involves multiple organs, including the bones, lungs, liver, and lymph nodes.14 Affected patients usually present with fever; hepatosplenomegaly; anemia; lymphadenopathy; extensive lytic skull lesions; and a generalized cutaneous eruption, appearing as a maculopapular scaling rash with underlying purpura on the scalp, neck, axilla, and trunk.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating a thinning of the epidermis and a collection of reticulum cells in the dermis.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is treated with radiation and chemotherapy; if left untreated, the disease is fatal.4

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic form of LCH, is most commonly seen in children aged 2 to 6 years and accounts for 15% to 20% of all LCH cases. This LCH variant presents with a classic triad of diabetes insipidus (resulting from erosion into the sella turcica), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos.15 Hand-Schüller-Christian disease also affects the oral cavity, producing nodular ulcerations of the hard palate, trouble swallowing, and halitosis.4 The involvement of lytic bone lesions of the mastoid process and petrous portions of the temporal bones may cause recurrent or chronic otitis media and otitis externa. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical excision. The mortality rate is 30%.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most prevalent variant of LCH, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases. Characterized by Langerhans cell granulomatous infiltration of the lungs and painful cystic bone lesions, eosinophilic granuloma primarily presents in the third or fourth decades of life.16 Some studies suggest an epidemiologic association with tobacco use.17 In the preliminary stages of this disease, Langerhans cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts infiltrate and form nodules on the terminal bronchioles in the upper and middle lung zones, damaging the airway walls.18 Fibrotic scarring progresses, ultimately resulting in alveolar destruction.10 The common signs and symptoms of eosinophilic granuloma are a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, spontaneous pneumothorax, fever, peripheral edema, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.14 The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma is variable. Although some patients progress to end-stage fibrotic lung disease requiring lung transplant, there have been reports of complete remission following cessation of cigarette smoking.17

Langerhans cells travel from the bone marrow to the epidermis where they express the CD1a protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell. Elevated levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukins have been seen in patients with LCH.1 Their role in the pathogenesis of this disease remains unknown, but the elevated levels of cytokines may indicate the lack of an efficient immune system.