User login

Bimatoprost-Induced Iris Hyperpigmentation: Beauty in the Darkened Eye of the Beholder

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

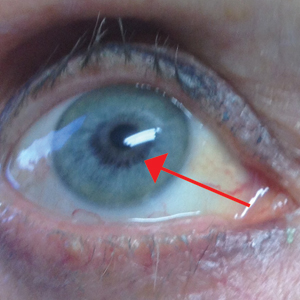

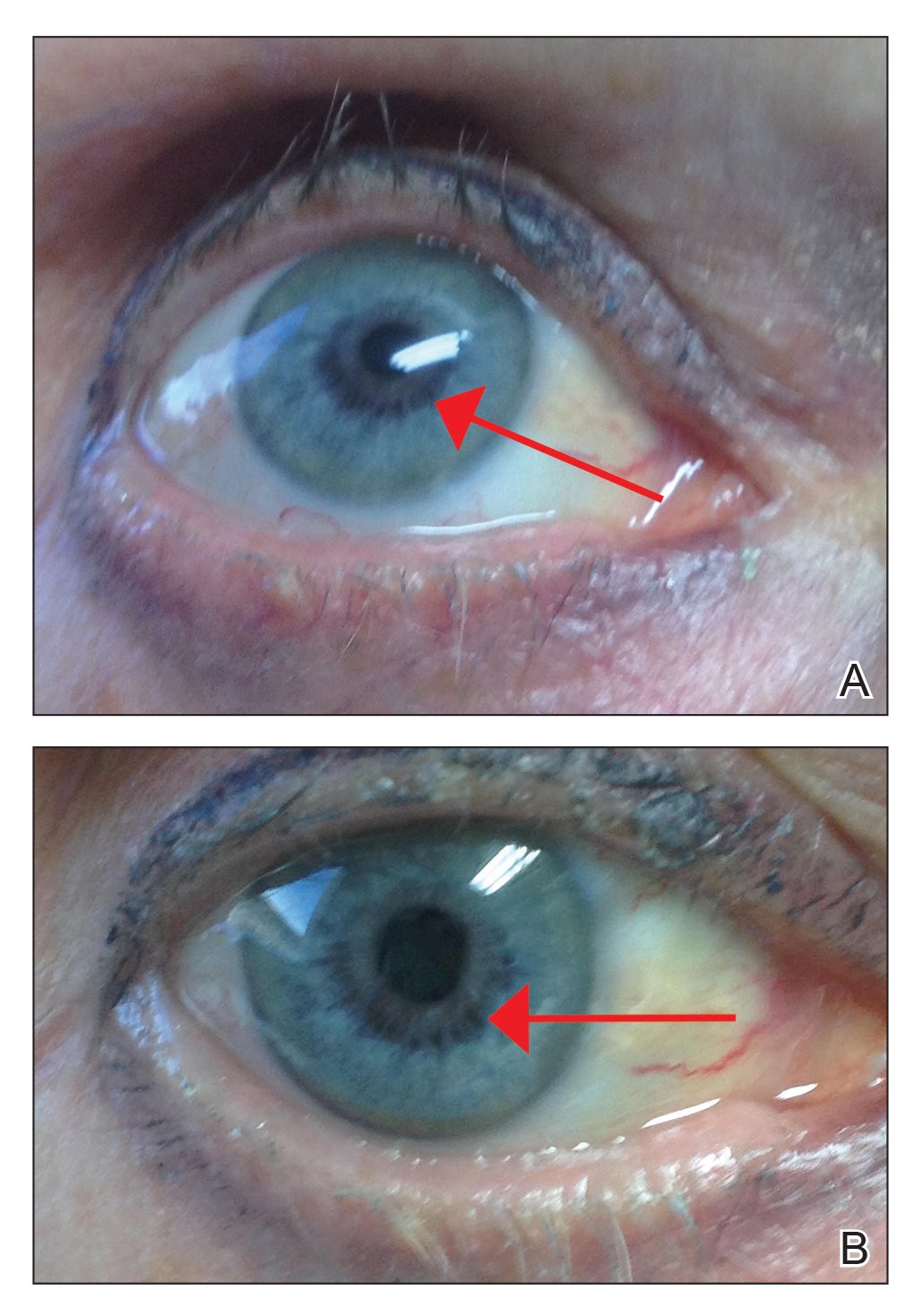

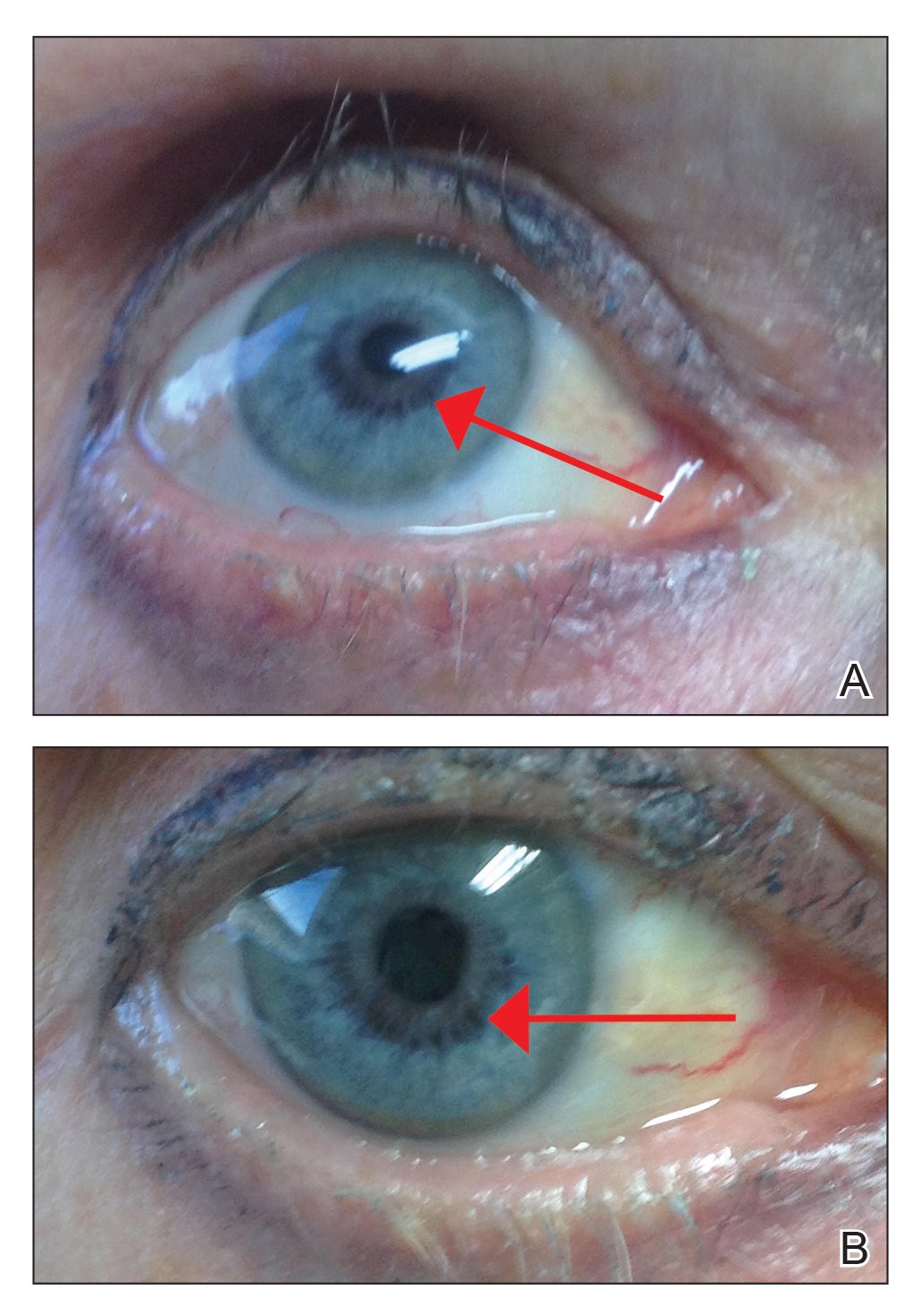

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

Practice Points

- Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2008 as an eyelash solution with an eyelid applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.

- Iris hyperpigmentation can occur when bimatoprost eye drops are applied to the eyes for treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma, but reports associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution are rare.

- It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information to avoid potential adverse events. The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye.

Concomitant Fibrofolliculoma and Trichodiscoma on the Abdomen

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas typically present on the head or neck as smooth, flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules. These two entities are considered to constitute two separate time points on a spectrum of histopathologic changes in mantleoma differentiation.1 Histologically, both are benign hamartomas of the pilosebaceous subunit and collectively are known as mantleomas. We present an unusual case of a concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen.

Case Report

An asymptomatic 54-year-old man presented for a routine full-body skin examination. A solitary, 2×1-cm, subcutaneous, doughy, mobile nodule was found on the left side of the abdomen with an overlying 2-mm yellow fleshy papule. The patient declined excision of the lesion, and it was recommended that he return for follow-up 3 months later.

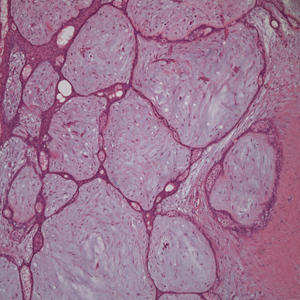

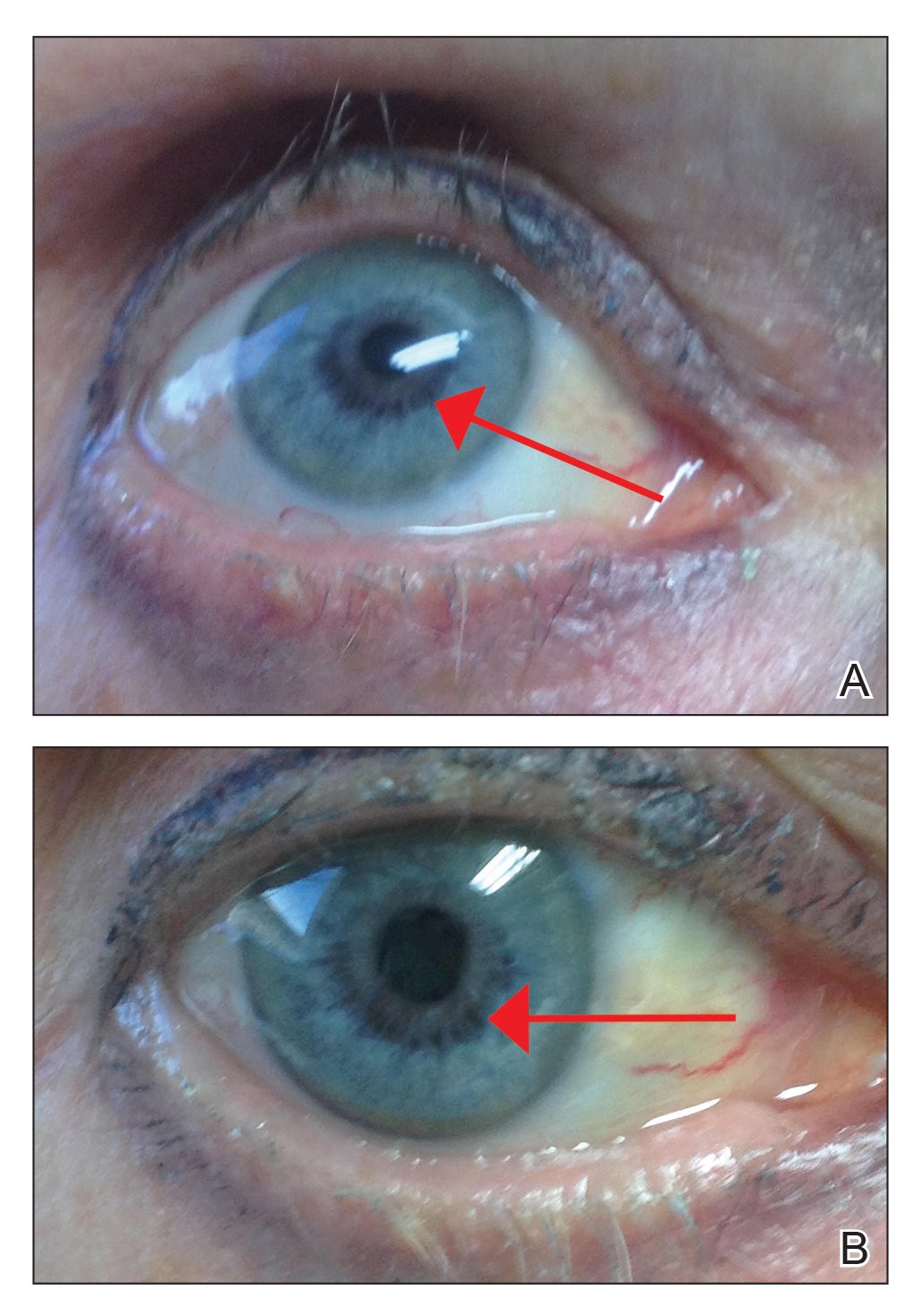

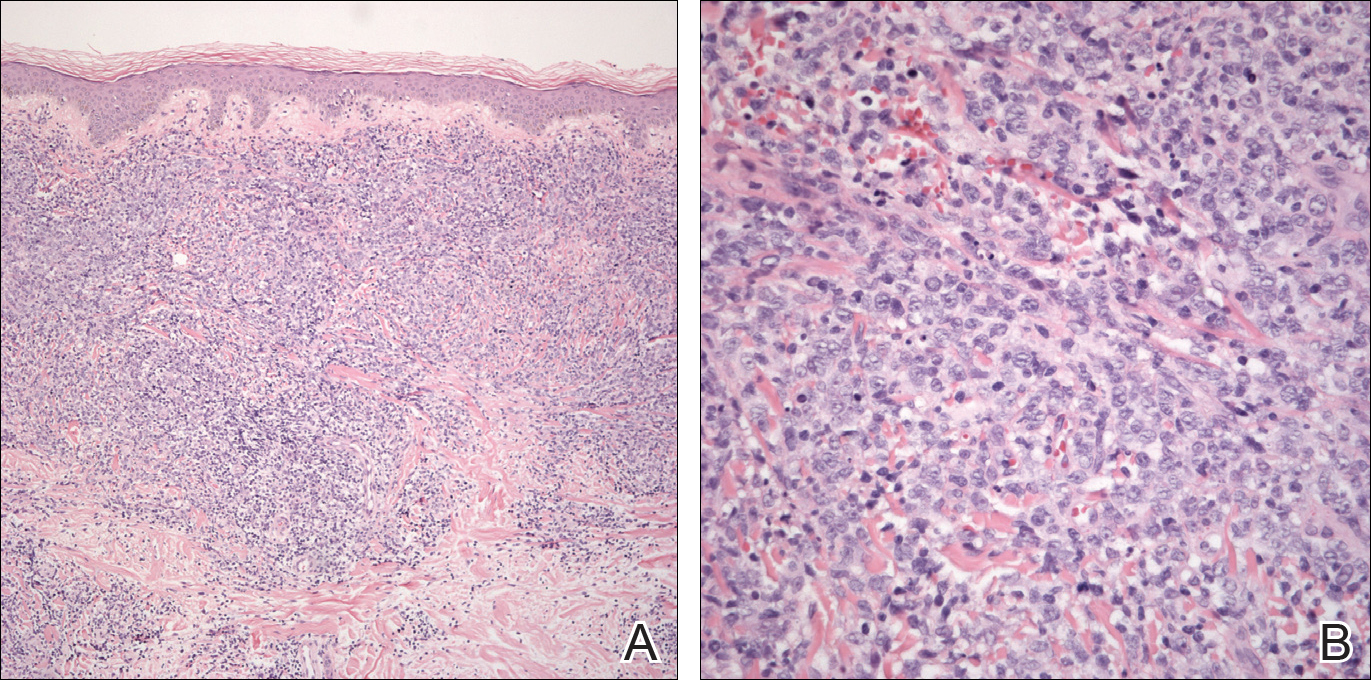

The patient did not present for follow-up until 4.5 years later, at which point the lesion had grown to 3.0×2.5 cm in size. An excision was performed, at which time the lesion was noted to be cystic, extruding an oily, yellow-white liquid. Bacterial culture was negative. Histopathologic sections showed a dome-shaped papule with connection to the overlying epidermis. Epithelial extensions from the infundibular epithelium formed a fenestrated pattern surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma (Figure, A and B). The differential diagnosis at this time included an epidermal inclusion cyst, fibroma, intradermal nevus, verruca, hemangioma, angiofibroma, and lipoma.2-4

The same lesion cut in a different plane of sectioning showed an expansile dermal nodule comprising clusters of sebaceous lobules surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma. Within the second lesion, fibrous and stromal components predominated over epithelial components (Figure, C). A diagnosis of fibrofolliculoma showing features of a trichodiscoma arising in the unusual location of the abdomen was made.

Comment

Solitary fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules that generally present on the face, specifically on the chin, nose, cheeks, ears, and eyebrows without considerable symptoms.2,4,5 Clinically, fibrofolliculomas are indistinguishable from trichodiscomas but demonstrate different features on biopsy.1,5

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are well known for their association with Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome when they present concomitantly and typically arise earlier in the third decade of life than solitary fibrofolliculomas; however, there have been reports of solitary fibrofolliculomas in patients aged 1 to 36 years.4,6 The triad of BHD syndrome consists of multiple fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons, and it is acquired in an autosomal-dominant manner, unlike solitary fibrofolliculomas, which typically are not inherited. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FLCN gene that codes for the tumor-suppressor protein folliculin, which when mutated can cause unregulated proliferation of cells.7 Solitary fibrofolliculomas and the multiple fibrofolliculomas seen in BHD syndrome are histologically similar.

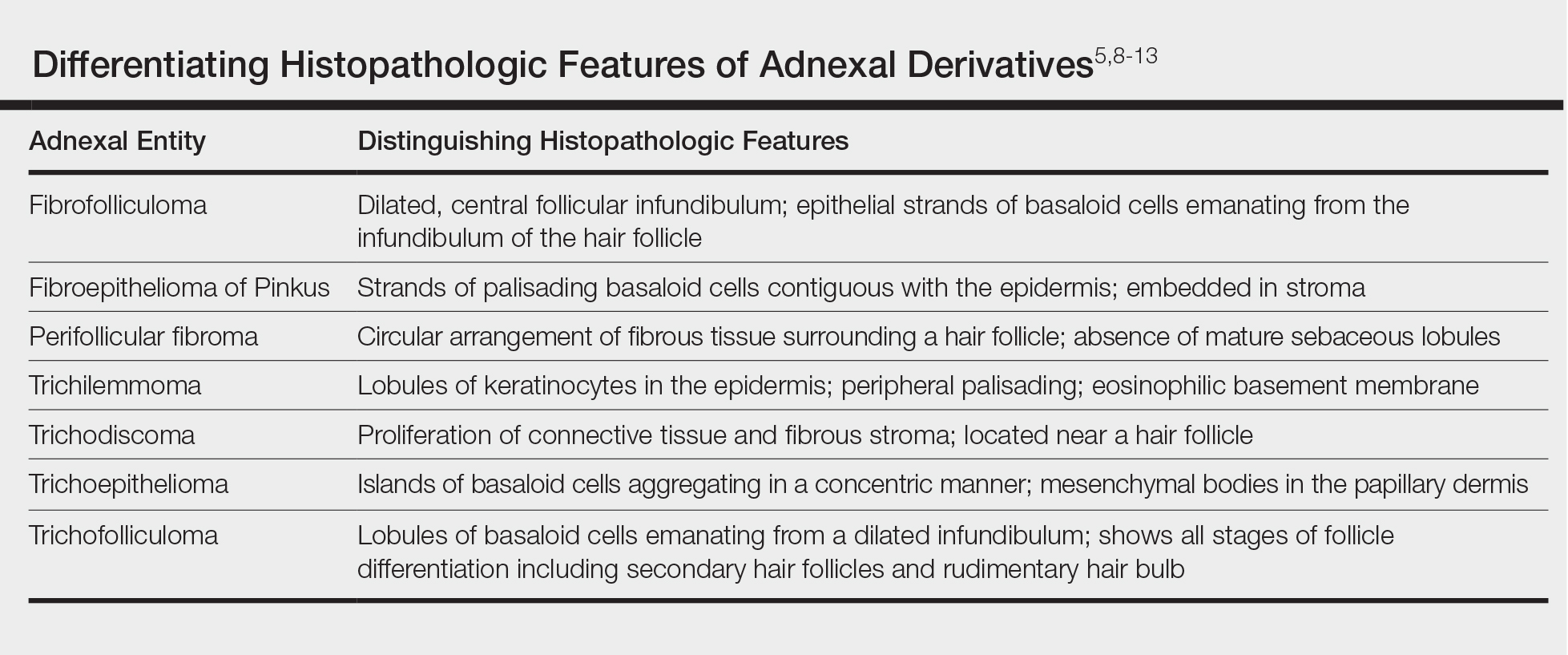

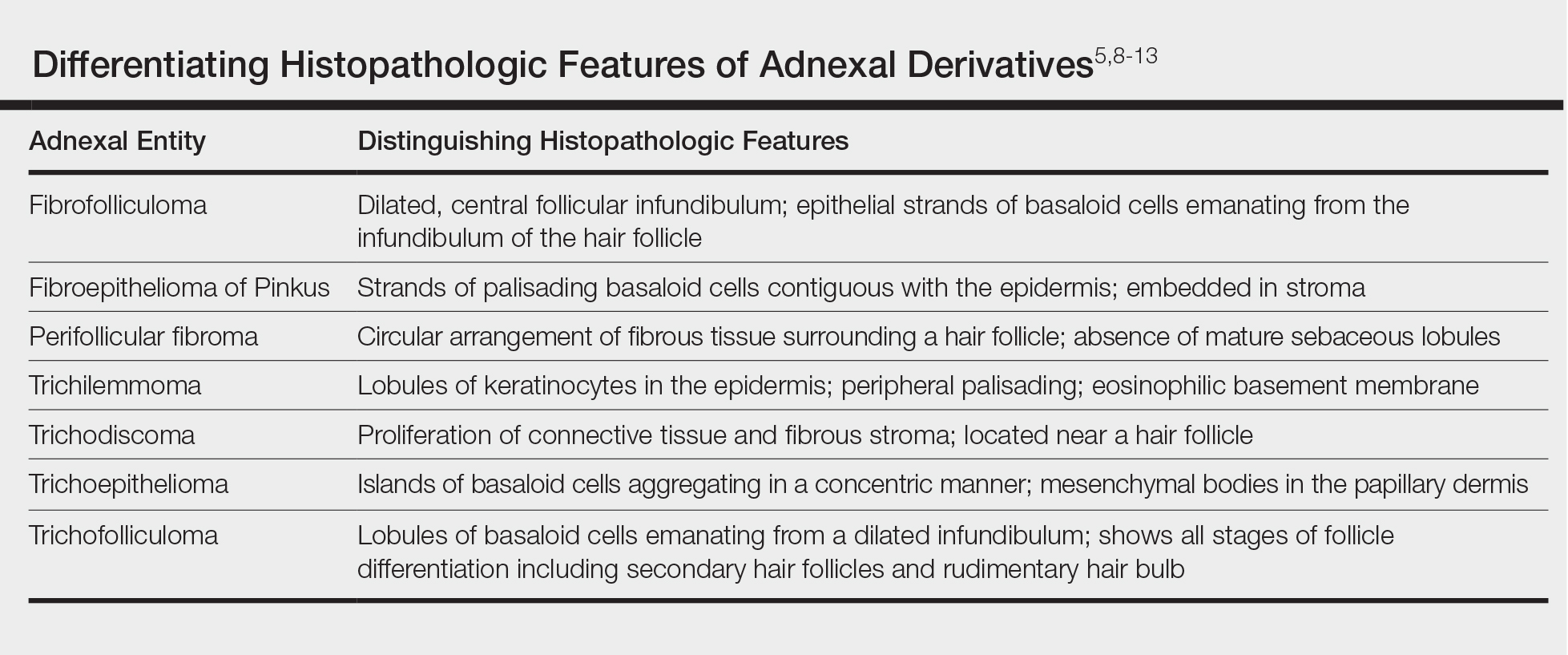

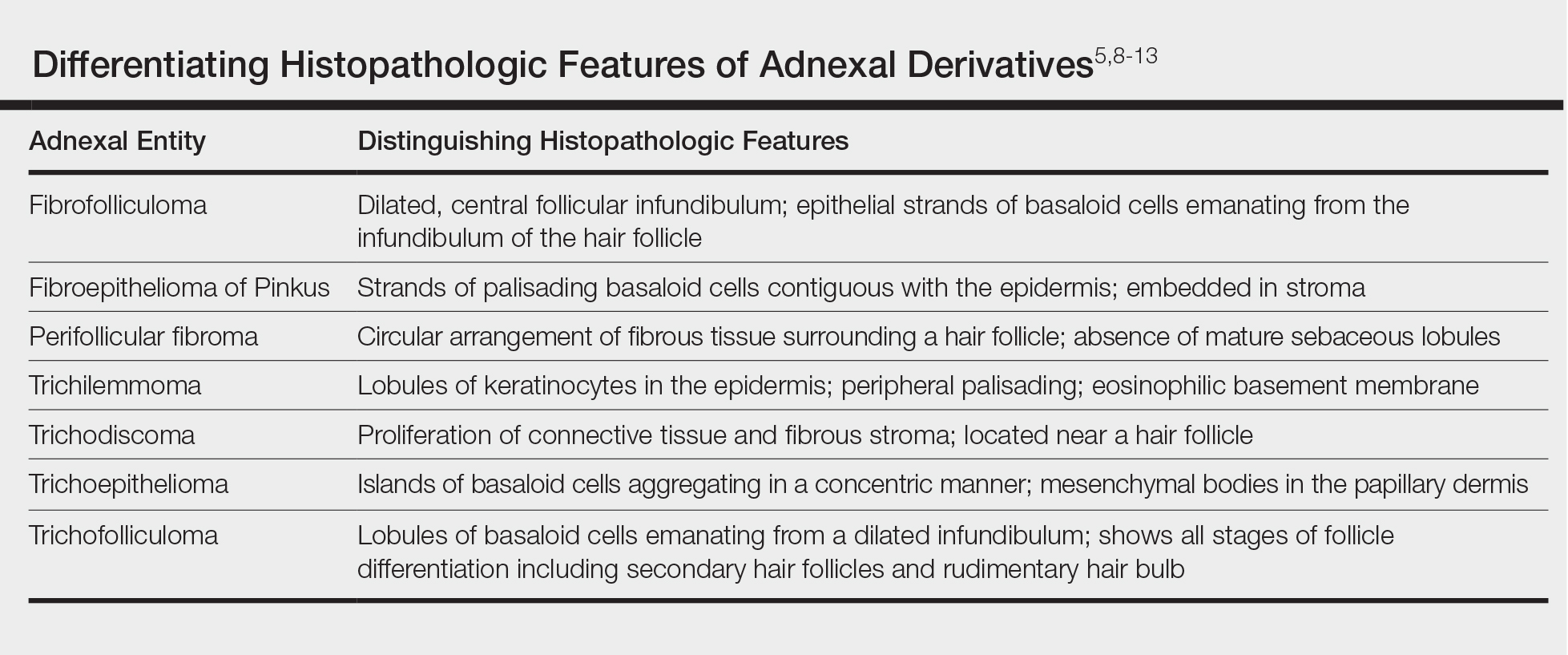

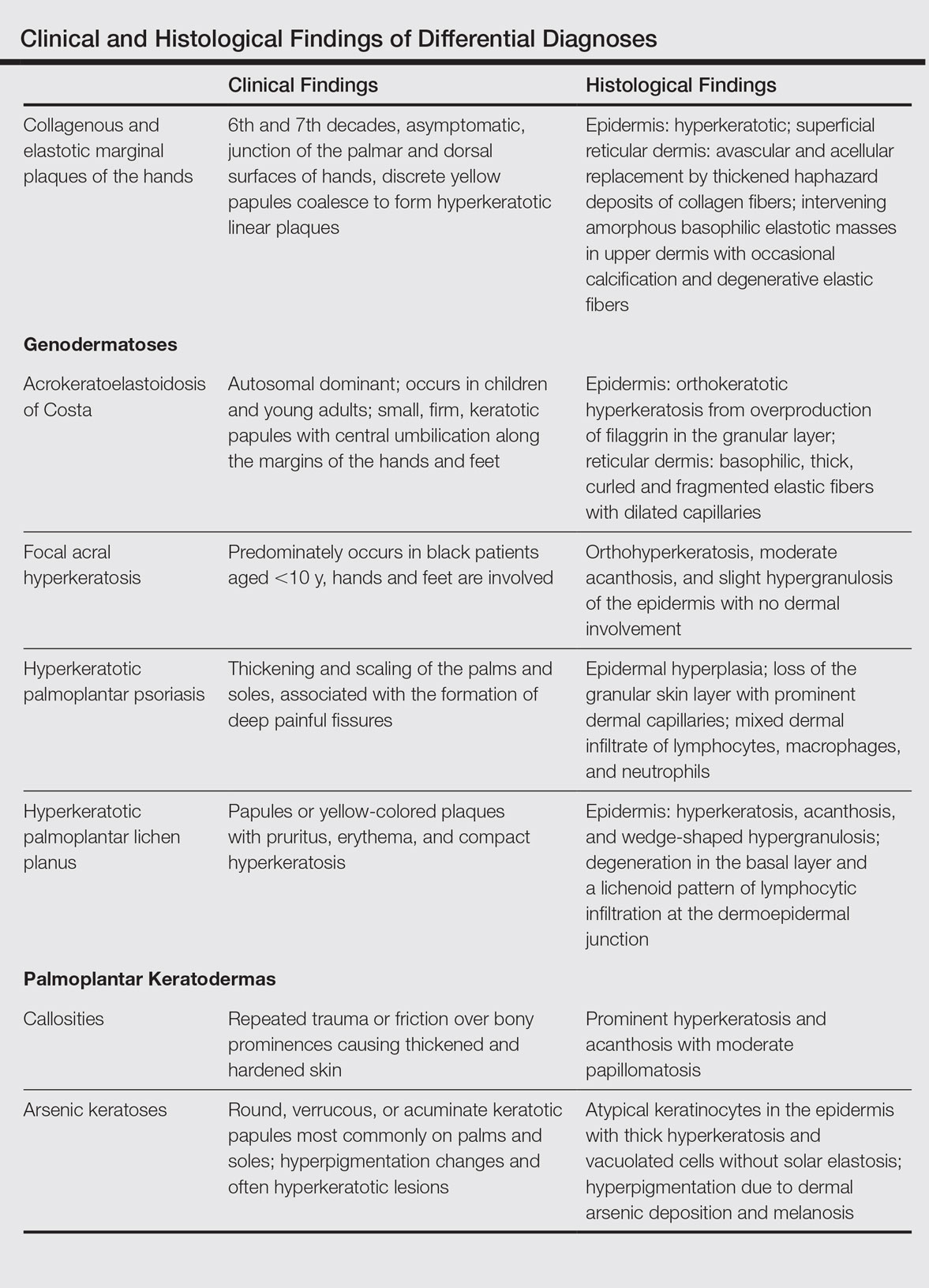

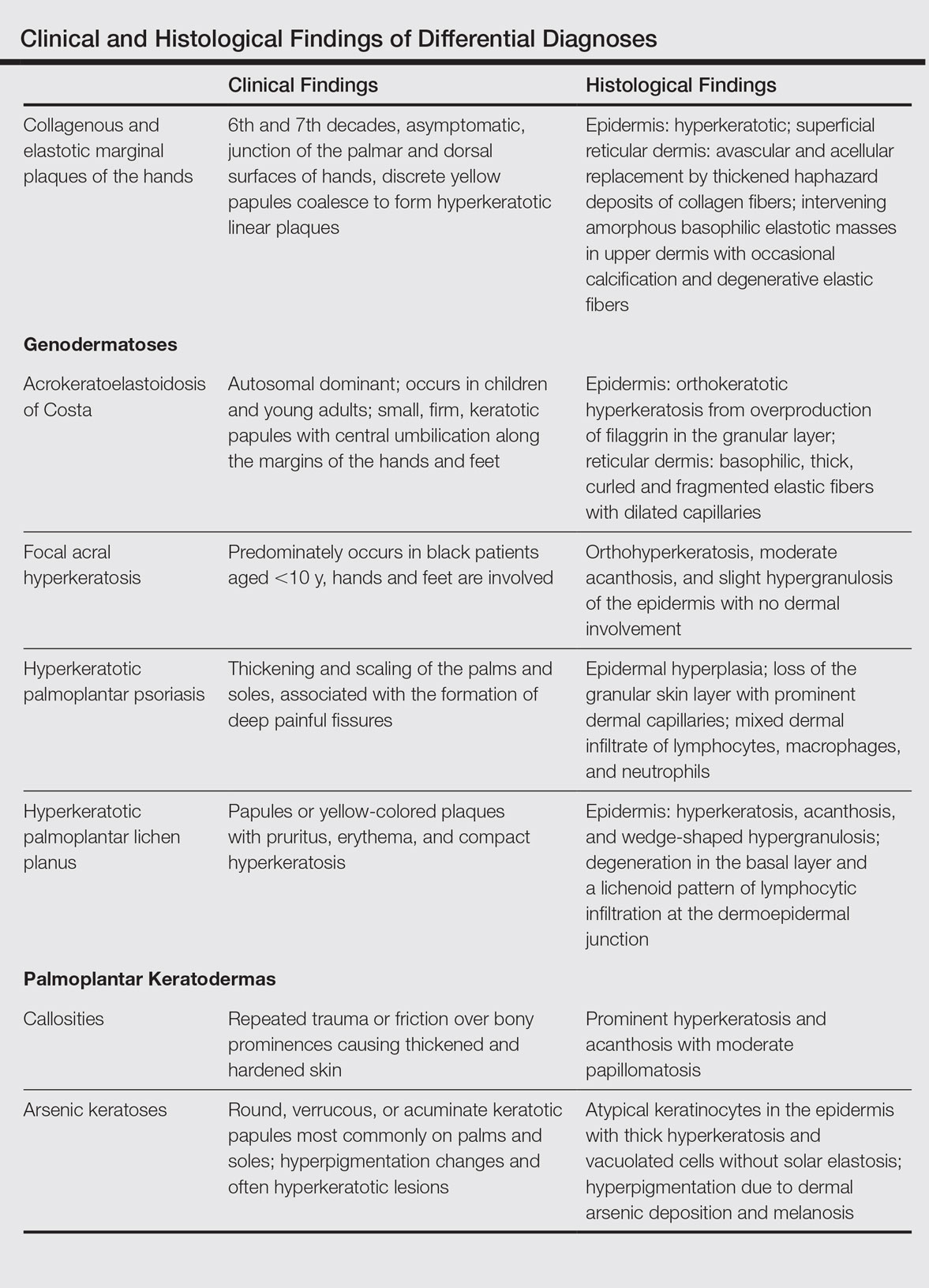

Fibrofolliculoma can be clinically indistinguishable from fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, perifollicular fibroma, trichilemmoma, trichodiscoma, trichoepithelioma, and trichofolliculoma. All typically present clinically as flesh-colored papules,1 although histologic distinction can be made (Table).5,8-13

Fibrofolliculoma is a benign hamartoma that arises from the pilosebaceous follicle and consists of an expansion of the fibrous root sheath, which typically surrounds the hair follicle along with proliferating bands or ribbons of perifollicular connective tissue. As such, the hair follicle may be dilated and filled with keratin in the expanded infundibulum.8 Follicles also may be surrounded by a myxoid stroma.2 In contrast, trichodiscoma is characterized by connective tissue with mature sebaceous lobules in the periphery. It has a myxoid stroma, as opposed to the more fibrous stroma seen in fibrofolliculomas.

Reports have examined the staining patterns of fibrofolliculomas, which show characteristics similar to those of other hair follicle hamartomas, including trichodiscomas.10 The connective tissue and epithelial components that constitute a fibrofolliculoma show different staining patterns. The connective tissue component stains positive for CD34 spindle cells, factor XIIIa, and nestin (a marker of angiogenesis). CD117 (c-kit) expression in the stroma, a marker of fibrocytes, is a feature of both fibrofolliculoma and perifollicular fibromas. The epithelial component, consisting of the hair follicle itself, stains positive for CK15. CK15 expression has been reported in undifferentiated sebocytes of the mantle and in the hair follicle.10 Immunohistochemical staining supports the notion that fibrofolliculomas contain connective tissue and epithelial components and helps to compare and contrast them to those of other hair follicle hamartomas.

Ackerman et al1 considered both fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas to be hamartomas of the epithelial hair follicle. The exact etiology of each of these hamartomas is unknown, but the undifferentiated epithelial strands protruding from the hair follicle in a fibrofolliculoma lie in close proximity to sebaceous glands. Furthermore, the authors postulated that fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas constitute a spectrum that encompasses the differentiation process of a mantleoma, with fibrofolliculoma representing the beginning of mantleoma differentiation and trichodiscoma representing the end. This end stage of follicular differentiation is one in which there is a predominant stroma and the previously undifferentiated epithelium has formed into sebaceous ducts and lobules in the stroma.1

Most cases of fibrofolliculoma and/or trichodiscoma arise in areas of dense sebaceous follicle concentration (eg, face), further supporting the hypothesis that sebaceous gland proliferation contributes to fibrofolliculoma.14 The case described here, with the fibrofolliculoma arising on the abdomen in conjunction with a trichodiscoma, is therefore worth noting because its location differs from what has been observed in previously reported cases.4

There are both surgical and medical options for treatment of fibrofolliculoma. Although surgical excision is an option for a single lesion, patients with multiple fibrofolliculomas or BHD may prefer removal with the combined CO2 laser and erbium-doped YAG laser.15

Conclusion

We present a rare case of concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma arising on the unusual location of the abdomen. This report highlights the histopathologic features of multiple adnexal tumors and emphasizes the importance of biopsy for differentiating fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma.

- Ackerman AB, Chongchitnant N, DeViragh P. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

- Scully K, Bargman H, Assaad D. Solitary fibrofolliculoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:361-363.

- Chang JK, Lee DC, Chang MH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma in the eyelid. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:169-171.

- Starink TM, Brownstein MH. Fibrofolliculoma: solitary and multiple types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:493-496.

- Cho EU, Lee JD, Cho SH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma on the concha of the ear. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:616-628.

- Mo HJ, Park CK, Yi JY. A case of solitary fibrofolliculoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:602-604.

- Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:157-164.

- Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1674-1677.

- Foucar K, Rosen TH, Foucar E, et al. Fibrofolliculoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cutis. 1981;28:429-432.

- Misago NO, Kimura TE, Narisawa YU. Fibrofolliculoma/trichodiscoma and fibrous papule (perifollicular fibroma/angiofibroma): a revaluation of the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:943-951.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 1):S108-S111.

- Lee Y, Su H, Chen H. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. a case report. Dermatologica Sinica. 2002;20:142-146.

- Nam JH, Min JH, Lee GY, et al. A case of perifollicular fibroma. Ann Dermatol. 2011:23:236-238.

- Vernooij M, Claessens T, Luijten M, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and the skin. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:381-385.

- Jacob CI, Dover JS. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: treatment of cutaneous manifestations with laser skin resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:98-99.

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas typically present on the head or neck as smooth, flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules. These two entities are considered to constitute two separate time points on a spectrum of histopathologic changes in mantleoma differentiation.1 Histologically, both are benign hamartomas of the pilosebaceous subunit and collectively are known as mantleomas. We present an unusual case of a concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen.

Case Report

An asymptomatic 54-year-old man presented for a routine full-body skin examination. A solitary, 2×1-cm, subcutaneous, doughy, mobile nodule was found on the left side of the abdomen with an overlying 2-mm yellow fleshy papule. The patient declined excision of the lesion, and it was recommended that he return for follow-up 3 months later.

The patient did not present for follow-up until 4.5 years later, at which point the lesion had grown to 3.0×2.5 cm in size. An excision was performed, at which time the lesion was noted to be cystic, extruding an oily, yellow-white liquid. Bacterial culture was negative. Histopathologic sections showed a dome-shaped papule with connection to the overlying epidermis. Epithelial extensions from the infundibular epithelium formed a fenestrated pattern surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma (Figure, A and B). The differential diagnosis at this time included an epidermal inclusion cyst, fibroma, intradermal nevus, verruca, hemangioma, angiofibroma, and lipoma.2-4

The same lesion cut in a different plane of sectioning showed an expansile dermal nodule comprising clusters of sebaceous lobules surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma. Within the second lesion, fibrous and stromal components predominated over epithelial components (Figure, C). A diagnosis of fibrofolliculoma showing features of a trichodiscoma arising in the unusual location of the abdomen was made.

Comment

Solitary fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules that generally present on the face, specifically on the chin, nose, cheeks, ears, and eyebrows without considerable symptoms.2,4,5 Clinically, fibrofolliculomas are indistinguishable from trichodiscomas but demonstrate different features on biopsy.1,5

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are well known for their association with Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome when they present concomitantly and typically arise earlier in the third decade of life than solitary fibrofolliculomas; however, there have been reports of solitary fibrofolliculomas in patients aged 1 to 36 years.4,6 The triad of BHD syndrome consists of multiple fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons, and it is acquired in an autosomal-dominant manner, unlike solitary fibrofolliculomas, which typically are not inherited. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FLCN gene that codes for the tumor-suppressor protein folliculin, which when mutated can cause unregulated proliferation of cells.7 Solitary fibrofolliculomas and the multiple fibrofolliculomas seen in BHD syndrome are histologically similar.

Fibrofolliculoma can be clinically indistinguishable from fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, perifollicular fibroma, trichilemmoma, trichodiscoma, trichoepithelioma, and trichofolliculoma. All typically present clinically as flesh-colored papules,1 although histologic distinction can be made (Table).5,8-13

Fibrofolliculoma is a benign hamartoma that arises from the pilosebaceous follicle and consists of an expansion of the fibrous root sheath, which typically surrounds the hair follicle along with proliferating bands or ribbons of perifollicular connective tissue. As such, the hair follicle may be dilated and filled with keratin in the expanded infundibulum.8 Follicles also may be surrounded by a myxoid stroma.2 In contrast, trichodiscoma is characterized by connective tissue with mature sebaceous lobules in the periphery. It has a myxoid stroma, as opposed to the more fibrous stroma seen in fibrofolliculomas.

Reports have examined the staining patterns of fibrofolliculomas, which show characteristics similar to those of other hair follicle hamartomas, including trichodiscomas.10 The connective tissue and epithelial components that constitute a fibrofolliculoma show different staining patterns. The connective tissue component stains positive for CD34 spindle cells, factor XIIIa, and nestin (a marker of angiogenesis). CD117 (c-kit) expression in the stroma, a marker of fibrocytes, is a feature of both fibrofolliculoma and perifollicular fibromas. The epithelial component, consisting of the hair follicle itself, stains positive for CK15. CK15 expression has been reported in undifferentiated sebocytes of the mantle and in the hair follicle.10 Immunohistochemical staining supports the notion that fibrofolliculomas contain connective tissue and epithelial components and helps to compare and contrast them to those of other hair follicle hamartomas.

Ackerman et al1 considered both fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas to be hamartomas of the epithelial hair follicle. The exact etiology of each of these hamartomas is unknown, but the undifferentiated epithelial strands protruding from the hair follicle in a fibrofolliculoma lie in close proximity to sebaceous glands. Furthermore, the authors postulated that fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas constitute a spectrum that encompasses the differentiation process of a mantleoma, with fibrofolliculoma representing the beginning of mantleoma differentiation and trichodiscoma representing the end. This end stage of follicular differentiation is one in which there is a predominant stroma and the previously undifferentiated epithelium has formed into sebaceous ducts and lobules in the stroma.1

Most cases of fibrofolliculoma and/or trichodiscoma arise in areas of dense sebaceous follicle concentration (eg, face), further supporting the hypothesis that sebaceous gland proliferation contributes to fibrofolliculoma.14 The case described here, with the fibrofolliculoma arising on the abdomen in conjunction with a trichodiscoma, is therefore worth noting because its location differs from what has been observed in previously reported cases.4

There are both surgical and medical options for treatment of fibrofolliculoma. Although surgical excision is an option for a single lesion, patients with multiple fibrofolliculomas or BHD may prefer removal with the combined CO2 laser and erbium-doped YAG laser.15

Conclusion

We present a rare case of concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma arising on the unusual location of the abdomen. This report highlights the histopathologic features of multiple adnexal tumors and emphasizes the importance of biopsy for differentiating fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma.

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas typically present on the head or neck as smooth, flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules. These two entities are considered to constitute two separate time points on a spectrum of histopathologic changes in mantleoma differentiation.1 Histologically, both are benign hamartomas of the pilosebaceous subunit and collectively are known as mantleomas. We present an unusual case of a concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma on the abdomen.

Case Report

An asymptomatic 54-year-old man presented for a routine full-body skin examination. A solitary, 2×1-cm, subcutaneous, doughy, mobile nodule was found on the left side of the abdomen with an overlying 2-mm yellow fleshy papule. The patient declined excision of the lesion, and it was recommended that he return for follow-up 3 months later.

The patient did not present for follow-up until 4.5 years later, at which point the lesion had grown to 3.0×2.5 cm in size. An excision was performed, at which time the lesion was noted to be cystic, extruding an oily, yellow-white liquid. Bacterial culture was negative. Histopathologic sections showed a dome-shaped papule with connection to the overlying epidermis. Epithelial extensions from the infundibular epithelium formed a fenestrated pattern surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma (Figure, A and B). The differential diagnosis at this time included an epidermal inclusion cyst, fibroma, intradermal nevus, verruca, hemangioma, angiofibroma, and lipoma.2-4

The same lesion cut in a different plane of sectioning showed an expansile dermal nodule comprising clusters of sebaceous lobules surrounding a fibrous and mucinous stroma. Within the second lesion, fibrous and stromal components predominated over epithelial components (Figure, C). A diagnosis of fibrofolliculoma showing features of a trichodiscoma arising in the unusual location of the abdomen was made.

Comment

Solitary fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules that generally present on the face, specifically on the chin, nose, cheeks, ears, and eyebrows without considerable symptoms.2,4,5 Clinically, fibrofolliculomas are indistinguishable from trichodiscomas but demonstrate different features on biopsy.1,5

Fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas are well known for their association with Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome when they present concomitantly and typically arise earlier in the third decade of life than solitary fibrofolliculomas; however, there have been reports of solitary fibrofolliculomas in patients aged 1 to 36 years.4,6 The triad of BHD syndrome consists of multiple fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons, and it is acquired in an autosomal-dominant manner, unlike solitary fibrofolliculomas, which typically are not inherited. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FLCN gene that codes for the tumor-suppressor protein folliculin, which when mutated can cause unregulated proliferation of cells.7 Solitary fibrofolliculomas and the multiple fibrofolliculomas seen in BHD syndrome are histologically similar.

Fibrofolliculoma can be clinically indistinguishable from fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, perifollicular fibroma, trichilemmoma, trichodiscoma, trichoepithelioma, and trichofolliculoma. All typically present clinically as flesh-colored papules,1 although histologic distinction can be made (Table).5,8-13

Fibrofolliculoma is a benign hamartoma that arises from the pilosebaceous follicle and consists of an expansion of the fibrous root sheath, which typically surrounds the hair follicle along with proliferating bands or ribbons of perifollicular connective tissue. As such, the hair follicle may be dilated and filled with keratin in the expanded infundibulum.8 Follicles also may be surrounded by a myxoid stroma.2 In contrast, trichodiscoma is characterized by connective tissue with mature sebaceous lobules in the periphery. It has a myxoid stroma, as opposed to the more fibrous stroma seen in fibrofolliculomas.

Reports have examined the staining patterns of fibrofolliculomas, which show characteristics similar to those of other hair follicle hamartomas, including trichodiscomas.10 The connective tissue and epithelial components that constitute a fibrofolliculoma show different staining patterns. The connective tissue component stains positive for CD34 spindle cells, factor XIIIa, and nestin (a marker of angiogenesis). CD117 (c-kit) expression in the stroma, a marker of fibrocytes, is a feature of both fibrofolliculoma and perifollicular fibromas. The epithelial component, consisting of the hair follicle itself, stains positive for CK15. CK15 expression has been reported in undifferentiated sebocytes of the mantle and in the hair follicle.10 Immunohistochemical staining supports the notion that fibrofolliculomas contain connective tissue and epithelial components and helps to compare and contrast them to those of other hair follicle hamartomas.

Ackerman et al1 considered both fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas to be hamartomas of the epithelial hair follicle. The exact etiology of each of these hamartomas is unknown, but the undifferentiated epithelial strands protruding from the hair follicle in a fibrofolliculoma lie in close proximity to sebaceous glands. Furthermore, the authors postulated that fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas constitute a spectrum that encompasses the differentiation process of a mantleoma, with fibrofolliculoma representing the beginning of mantleoma differentiation and trichodiscoma representing the end. This end stage of follicular differentiation is one in which there is a predominant stroma and the previously undifferentiated epithelium has formed into sebaceous ducts and lobules in the stroma.1

Most cases of fibrofolliculoma and/or trichodiscoma arise in areas of dense sebaceous follicle concentration (eg, face), further supporting the hypothesis that sebaceous gland proliferation contributes to fibrofolliculoma.14 The case described here, with the fibrofolliculoma arising on the abdomen in conjunction with a trichodiscoma, is therefore worth noting because its location differs from what has been observed in previously reported cases.4

There are both surgical and medical options for treatment of fibrofolliculoma. Although surgical excision is an option for a single lesion, patients with multiple fibrofolliculomas or BHD may prefer removal with the combined CO2 laser and erbium-doped YAG laser.15

Conclusion

We present a rare case of concomitant fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma arising on the unusual location of the abdomen. This report highlights the histopathologic features of multiple adnexal tumors and emphasizes the importance of biopsy for differentiating fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma.

- Ackerman AB, Chongchitnant N, DeViragh P. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

- Scully K, Bargman H, Assaad D. Solitary fibrofolliculoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:361-363.

- Chang JK, Lee DC, Chang MH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma in the eyelid. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:169-171.

- Starink TM, Brownstein MH. Fibrofolliculoma: solitary and multiple types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:493-496.

- Cho EU, Lee JD, Cho SH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma on the concha of the ear. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:616-628.

- Mo HJ, Park CK, Yi JY. A case of solitary fibrofolliculoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:602-604.

- Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:157-164.

- Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1674-1677.

- Foucar K, Rosen TH, Foucar E, et al. Fibrofolliculoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cutis. 1981;28:429-432.

- Misago NO, Kimura TE, Narisawa YU. Fibrofolliculoma/trichodiscoma and fibrous papule (perifollicular fibroma/angiofibroma): a revaluation of the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:943-951.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 1):S108-S111.

- Lee Y, Su H, Chen H. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. a case report. Dermatologica Sinica. 2002;20:142-146.

- Nam JH, Min JH, Lee GY, et al. A case of perifollicular fibroma. Ann Dermatol. 2011:23:236-238.

- Vernooij M, Claessens T, Luijten M, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and the skin. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:381-385.

- Jacob CI, Dover JS. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: treatment of cutaneous manifestations with laser skin resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:98-99.

- Ackerman AB, Chongchitnant N, DeViragh P. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

- Scully K, Bargman H, Assaad D. Solitary fibrofolliculoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:361-363.

- Chang JK, Lee DC, Chang MH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma in the eyelid. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:169-171.

- Starink TM, Brownstein MH. Fibrofolliculoma: solitary and multiple types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:493-496.

- Cho EU, Lee JD, Cho SH. A solitary fibrofolliculoma on the concha of the ear. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:616-628.

- Mo HJ, Park CK, Yi JY. A case of solitary fibrofolliculoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:602-604.

- Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:157-164.

- Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1674-1677.

- Foucar K, Rosen TH, Foucar E, et al. Fibrofolliculoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cutis. 1981;28:429-432.

- Misago NO, Kimura TE, Narisawa YU. Fibrofolliculoma/trichodiscoma and fibrous papule (perifollicular fibroma/angiofibroma): a revaluation of the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:943-951.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 1):S108-S111.

- Lee Y, Su H, Chen H. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. a case report. Dermatologica Sinica. 2002;20:142-146.

- Nam JH, Min JH, Lee GY, et al. A case of perifollicular fibroma. Ann Dermatol. 2011:23:236-238.

- Vernooij M, Claessens T, Luijten M, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and the skin. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:381-385.

- Jacob CI, Dover JS. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: treatment of cutaneous manifestations with laser skin resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:98-99.

Practice Points

- Fibrofolliculoma and trichodiscoma are flesh-colored adnexal tumors that arise from or around hair follicles.

- It is important to recognize these entities, as they can be related to Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.

A Rare Case of Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old woman presented with a painful lesion on the left lower leg that was getting larger and more edematous and erythematous over the last 5 months. She experienced numbness and burning of the left lower leg 1 year prior to the development of the lesion. A review of her medical history revealed an otherwise healthy woman with no constitutional symptoms of fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or chest pain. The patient did not exhibit mucosal, genital, or nail involvement. Physical examination revealed a group of four 1-cm, ill-defined, irregularly bordered, violaceous plaques on the left anterior tibial leg with faint surrounding erythematous to violaceous patches (Figure 1). The plaques were tender to palpation with no bleeding or drainage.

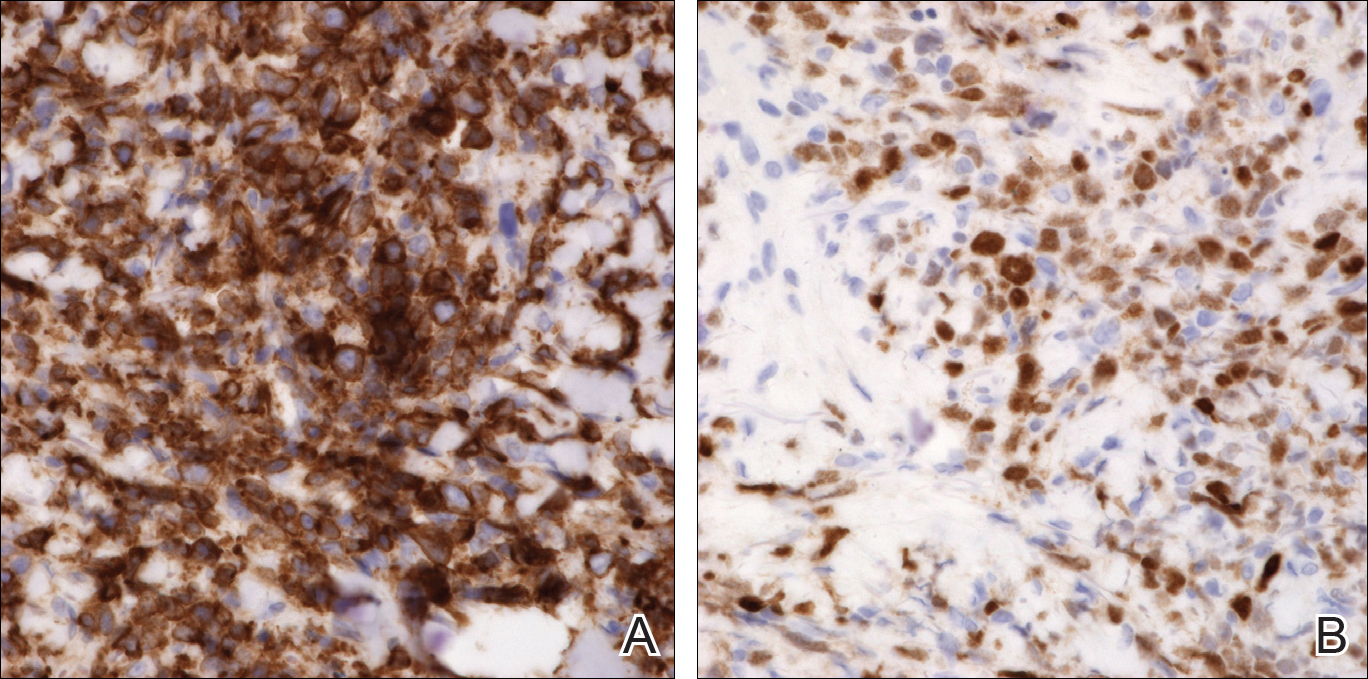

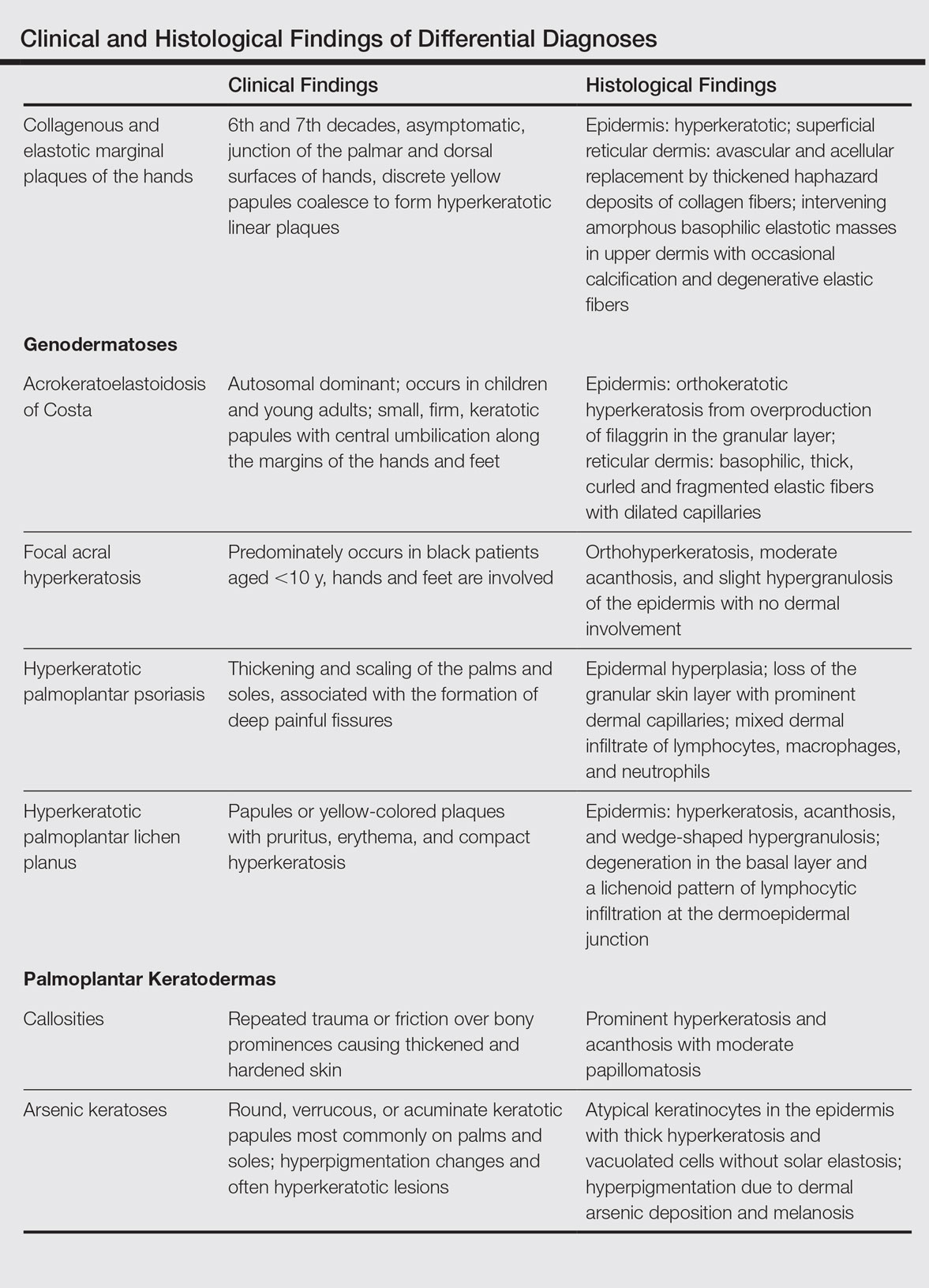

An 8.0-mm punch biopsy of the lesion was obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining on low-power magnification demonstrated a diffuse lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis and subcutis. Notable sparing of the subepidermal area (free grenz zone) was present (Figure 2A). On higher power, centroblasts and immunoblasts were visualized alongside extravasated red blood cells (Figure 2B). A diagnosis of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCLLT) was made. Various immunohistochemical stains confirmed the diagnosis, including B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)(Figure 3A) and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1)(Figure 3B), which were highly positive in our patient. The patient had a negative bone marrow biopsy and positron emission tomography scan. She was started on rituximab infusions and multiple radiation treatments. At 2-year follow-up the lymphoma continued to recur despite radiation therapy.

COMMENT

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Primary cutaneous DLBCLLT is an intermediately aggressive form of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) that accounts for approximately 10% to 20% of all primary CBCLs and 1% to 3% of all cutaneous lymphomas.1 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type primarily affects elderly patients (median age, 70 years). Women are more commonly affected. Clinically, primary cutaneous DLBCLLT presents as red-brown to bluish nodules or tumors on one or both distal legs.

Histopathology

The diagnosis of DLBCLLT is best made histologically. There is a dense inflammatory infiltrate present in the dermis and subcutis that may extend upward into the dermoepidermal junction. Often a subepidermal free grenz zone may be seen, and adnexal structures may be destroyed. This infiltrate is composed of confluent sheets of large round cells including centroblasts and immunoblasts.2 Centroblasts are large cells that have nuclei with several small nucleoli adhering to the membrane, while immunoblasts are large round cells containing nuclei with large central nucleoli. Both centroblasts and immunoblasts stain positively for BCL-2. Centrocytes typically are absent. Staining for BCL-2 can be important in distinguishing DLBCLLT from other forms of CBCL. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type also can demonstrate clusters of large atypical cells in the epidermis simulating epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. Neoplastic cells in this condition may express monoclonal surface and cytoplasmic immunoglobulins. Primary cutaneous DLBCLLT typically is positive for B-cell markers CD20 and CD79a. Additionally, MUM-1/IRF4 (interferon regulatory factor 4) and forkhead box protein 1 (FOXP1) are strongly expressed by most patients, which helps distinguish it from other forms of CBCL.

Treatment

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type is a relatively aggressive form of CBCL that requires more aggressive treatment than the conservative watchful waiting of some of the more indolent forms of primary CBCL. One regimen involves using cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone plus rituximab. Local chemotherapy or radiation with rituximab is another treatment option.1,2 In patients with severe comorbidities, rituximab alone may be administered. The prognosis for DLBCLLT is not as favorable as other types of primary CBCL, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of approximately 50%.2

Differential Diagnosis

Lymphomas are malignancies of the lymphocytes that may be subdivided depending on the organ of origin. Both primary nodal lymphomas and primary cutaneous lymphomas exist. Primary nodal lymphomas arise from the lymph nodes and are divided into Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. There are 2 major types of primary cutaneous lymphomas: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and CBCL. Most primary cutaneous lymphomas are CTCLs, accounting for 75% to 80%.3

Pseudolymphoma

Pseudolymphoma is an inflammatory condition that may histologically mimic cutaneous lymphoma but has a benign clinical course. Pseudolymphoma is not a specific disease but rather is a reactive lymphoproliferative response to a known or unknown stimulus.4 Pseudolymphoma can be broken down into 2 or 3 major categories: cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma; cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphoma; and debatably lymphomatoid papulosis, a chronic, self-remitting, papulonecrotic condition that resembles lymphoma histologically but clinically appears benign. It is unknown if lymphomatoid papulosis represents a pseudolymphoma or a true lymphoma. Lymphomatoid papulosis may represent an early indolent form of CTCL.4

Pseudolymphomas can be triggered by a variety of causes. Most cases are idiopathic, and a causative stimulus is never identified. Drugs are known to cause many cases of pseudolymphoma, either by a causing a hypersensitivity reaction or by depressing immunosurveillance.5 Pseudolymphomas may result from exogenous stimuli such as jewelry, tattoo dyes, injectable fillers (eg, silicone), insect bites, vaccines, and trauma.6,7 Lastly, infections in the form of Borrelia, varicella, and molluscum contagiosum can potentially cause pseudolymphomas.4

Clinically, pseudolymphomas may demonstrate a B-cell or T-cell pattern. In cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphomas, asymptomatic solitary erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored nodules appear on the face, followed by the chest and arms. Cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphomas present with erythematous patches that are more likely to be symptomatic.4

Histologically, pseudolymphomas also are classified as demonstrating B-cell or T-cell patterns. The nodular inflammatory infiltrate of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma corresponds with its clinically apparent nodules. It can be distinguished from lymphoma in that it is not solely a lymphocytic infiltrate but rather a mixed infiltrate including histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Additionally, cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma does not penetrate the dermis as deeply as CBCL.8 Cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphoma is more difficult to distinguish from CTCL because it also demonstrates a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with epidermotropism.9

Treatment must address the underlying cause of pseudolymphoma for resolution. Other treatment options include surgery, cryotherapy, local radiotherapy, topical steroids, and topical immunomodulators. Spontaneous resolution also can occur. The prognosis is better when a known trigger is eliminated, though idiopathic pseudolymphomas may be chronic in nature. It is important to rule out concurrent cutaneous lymphoma or rare transformation into cutaneous lymphoma.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a diverse group of neoplasms that account for most cutaneous lymphomas seen by dermatologists. In 1806, the first case of CTCL in the form of mycosis fungoides (MF) was described by Jean Louis Alibert. Mycosis fungoides represents the most common form of CTCL, accounting for approximately 50% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas.10 Mycosis fungoides was named after its morphological resemblance to mushrooms. Although not all cases exhibit a classic progression, MF is known for its stepwise progression from patch stage to tumor stage.

Clinically, lesions typically begin as patches that progress to plaques and finally tumors. This progression may not always occur and often can take years to decades to progress. Patches are characterized by erythematous, finely scaling lesions that may be easily confused with eczema or psoriasis. Lesions occur primarily in a swimming trunk distribution.

Mycosis fungoides histologically demonstrates a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, which occurs when lymphocytes infiltrate the epidermis without spongiosis. These lymphocytes are larger, darker, and more angulated than normal lymphocytes. Intraepidermal nests of these atypical lymphocytes creating Pautrier microabscesses may be present. Tumor-stage lesions demonstrate diminished epidermotropism with dense sheets of lymphocytes in the dermis, and fat cells with cerebriform nuclei are present.

Therapies for MF may control the disease but may not prolong patients’ lives. Topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, and radiotherapy are options for skin-targeting therapies. Systemic chemotherapy and biological response modifiers also are viable treatment options. Prognosis for MF is poor.

There are a few notable variants of MF that are important to consider. Sézary syndrome is an erythrodermic variant of MF characterized by atypical Sézary cells. Clinically, it presents with generalized erythroderma with leonine facies, facial edema, and alopecia with associated symptoms of burning and pruritus. Histologically, Sézary syndrome is similar to MF with an increased CD4:CD8 ratio.10 Sézary syndrome may be treated with methotrexate or photopheresis, but the prognosis remains poor with an average survival of 5 years.

Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma

There are 5 types of primary CBCL: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other; precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma; and primary cutaneous DLBCLLT, which was seen in our patient.11

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent neoplastic proliferation in the skin. Clinically, it presents with solitary or grouped pinkish purple papules, plaques, or nodules on the trunk with surrounding patches of erythema.3 Lesions located on the back are referred to as Crosti lymphoma. Histopathology reveals a lymphocytic infiltrate with a diffuse follicular pattern and large round centroblasts, centrocytes, and immunoblasts with epidermal sparing. Tumor cells stain positively for κ or λ light chains, as well as CD20, CD79a, and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6); however, staining for the protein product of BCL-2 may be negative, which differentiates this form of CBCL from primary nodal B-cell lymphoma. Staining for MUM-1 may be negative, which contrasts with the strong expression seen in DLBCLLT. The follicular pattern of follicle center lymphoma stains positive for CD10, but the diffuse pattern may be CD10 negative. The prognosis for primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is favorable, but the recurrence rate is up to 50%.3 Treatment includes local radiotherapy or surgical excision.

Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is another indolent primary CBCL subtype that is closely related to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas and arises in areas of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and Borrelia infection. Clinically, it presents with recurrent, asymptomatic, red-brown papules, plaques, and nodules of the arms and legs. Histologically, there is a patchy infiltrate in the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the epidermis with pale-staining cells with indented nuclei, along with plasma cells and eosinophils. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma typically does not demonstrate epidermotropism. Centrocyte cells stain positively for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-2. The prognosis of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is favorable. Treatment is similar to primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with surgical excision, radiotherapy, and surveillance being the main modalities.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other is an intermediately aggressive form of primary CBCL that is thought to be related to primary cutaneous DLBCLLT. Clinically, it presents with indurated erythematous to violaceous plaques on the trunk and thighs that may resemble a vascular tumor or panniculitis.2,12 Histopathologically, this form of lymphoma presents with a round cell morphology without BCL-2 expression, which distinguishes it from DLBCLLT. If limited to skin, the prognosis is better than the systemic form but is still less favorable than other forms of CBCL.

Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is an extremely rare type of CBCL that potentially can occur in the skin. It primarily affects children and young adults. Clinically, it presents as a solitary large erythematous tumor of the head. Histol

CONCLUSION

We present a rare case of primary cutaneous DLBCLLT. Our case demonstrates the classic presentation of primary cutaneous DLBCLLT in a 74-year-old woman with a tumor on the lower left leg. Histologically, a dense dermal and subcutis infiltrate of centroblasts and immunoblasts with a grenz zone was present. Immunostaining in our patient was consistent with characteristic findings in the literature, staining highly positive for BCL-2 and MUM-1. Primary cutaneous DLBCLLT is an extremely rare and unique form of cutaneous lymphoma that can have potentially fatal consequences if undiagnosed; therefore, clinicians must take great care to make the correct diagnosis based on a knowledge of the clinical and immunohistochemical findings of DLBCLLT.

- Sokol L, Naghashpour M, Glass LF. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: recent advances in diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2012;19:236-244.

- Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144-1150.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:2768-3785.

- Brodell RT, Santa Cruz DJ. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:719-734.