User login

Edema Affecting the Penis and Scrotum

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

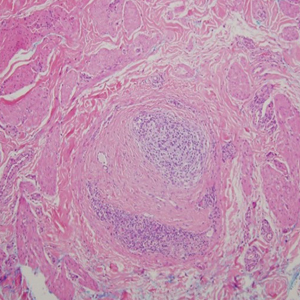

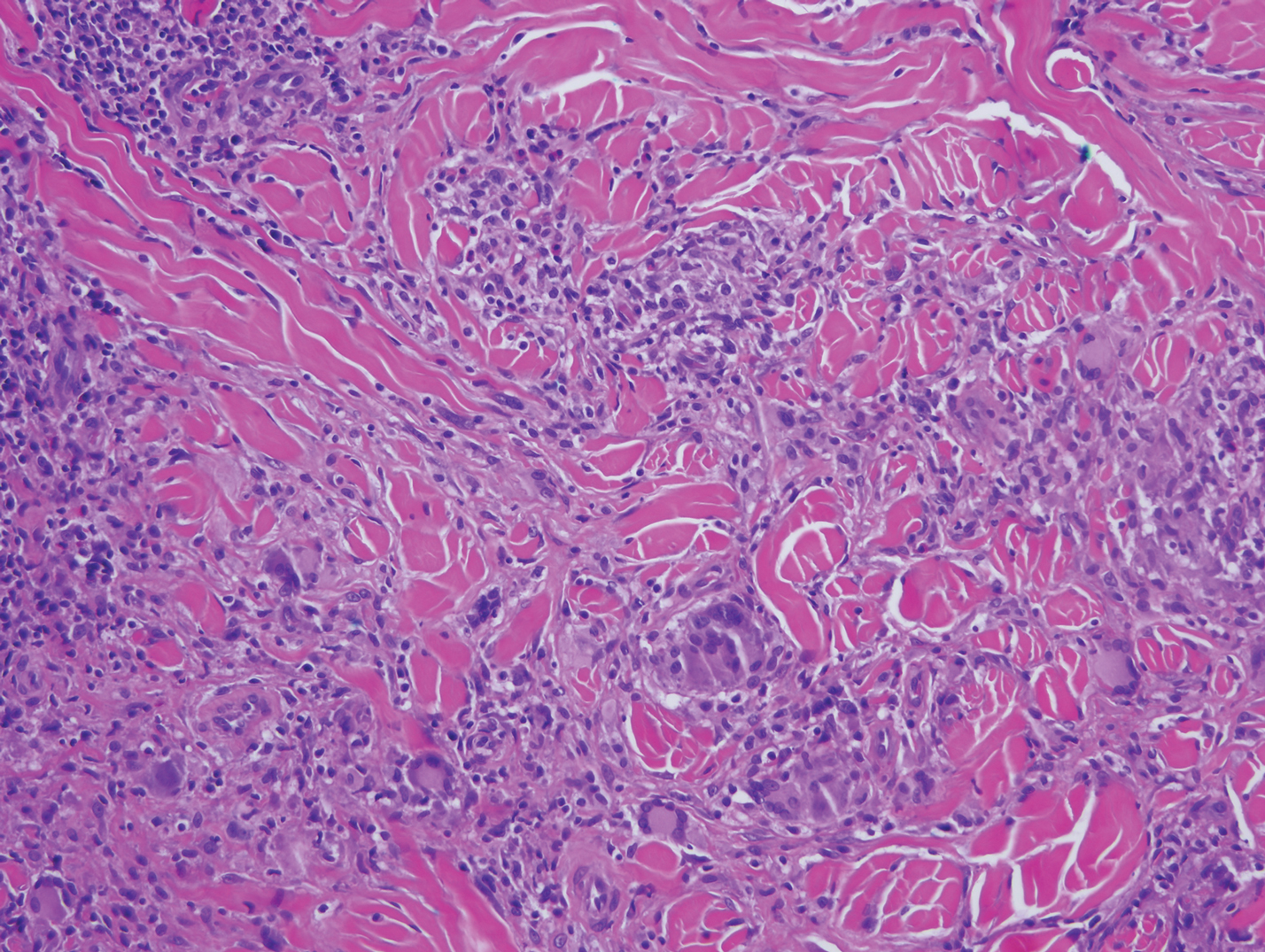

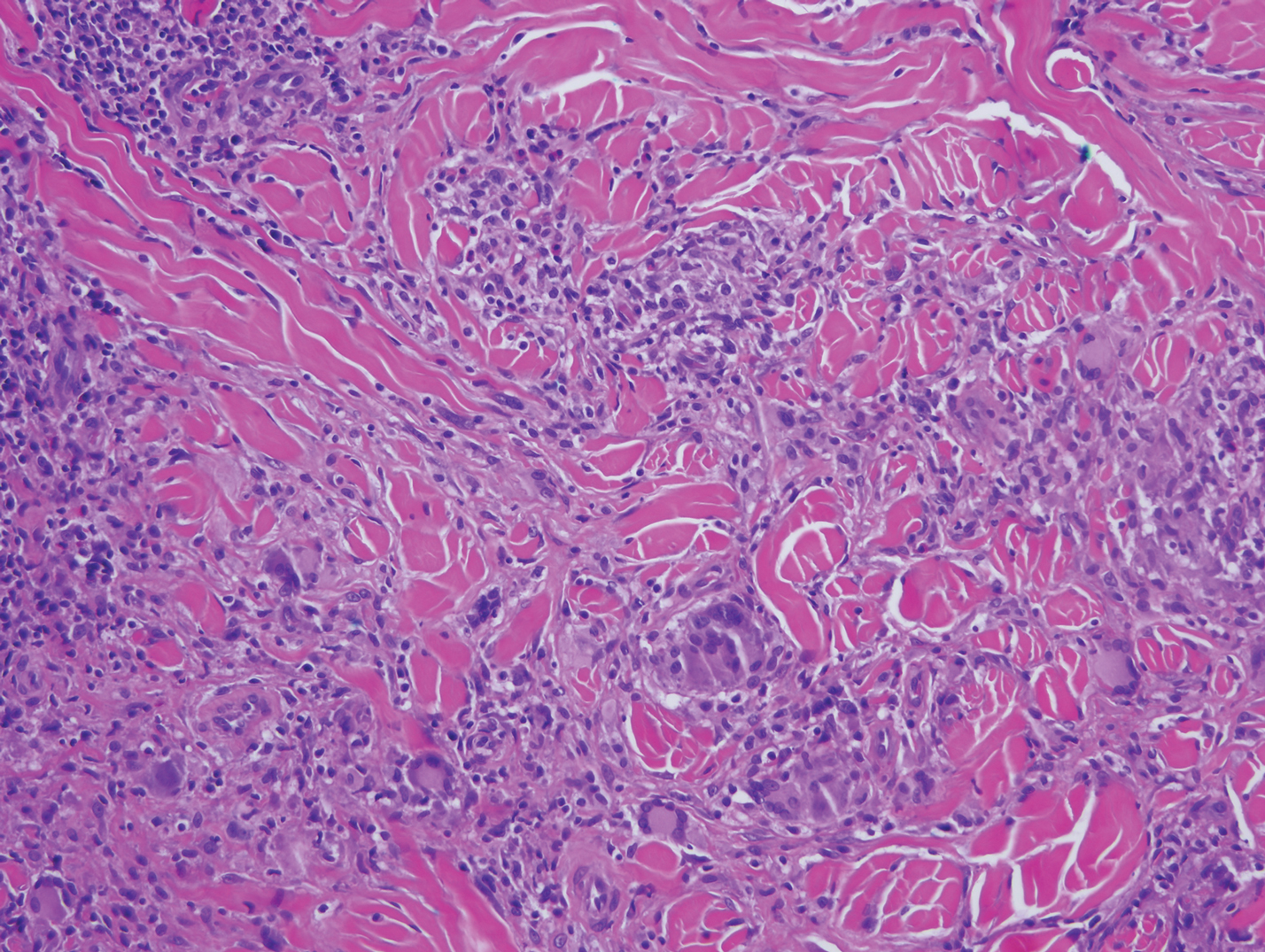

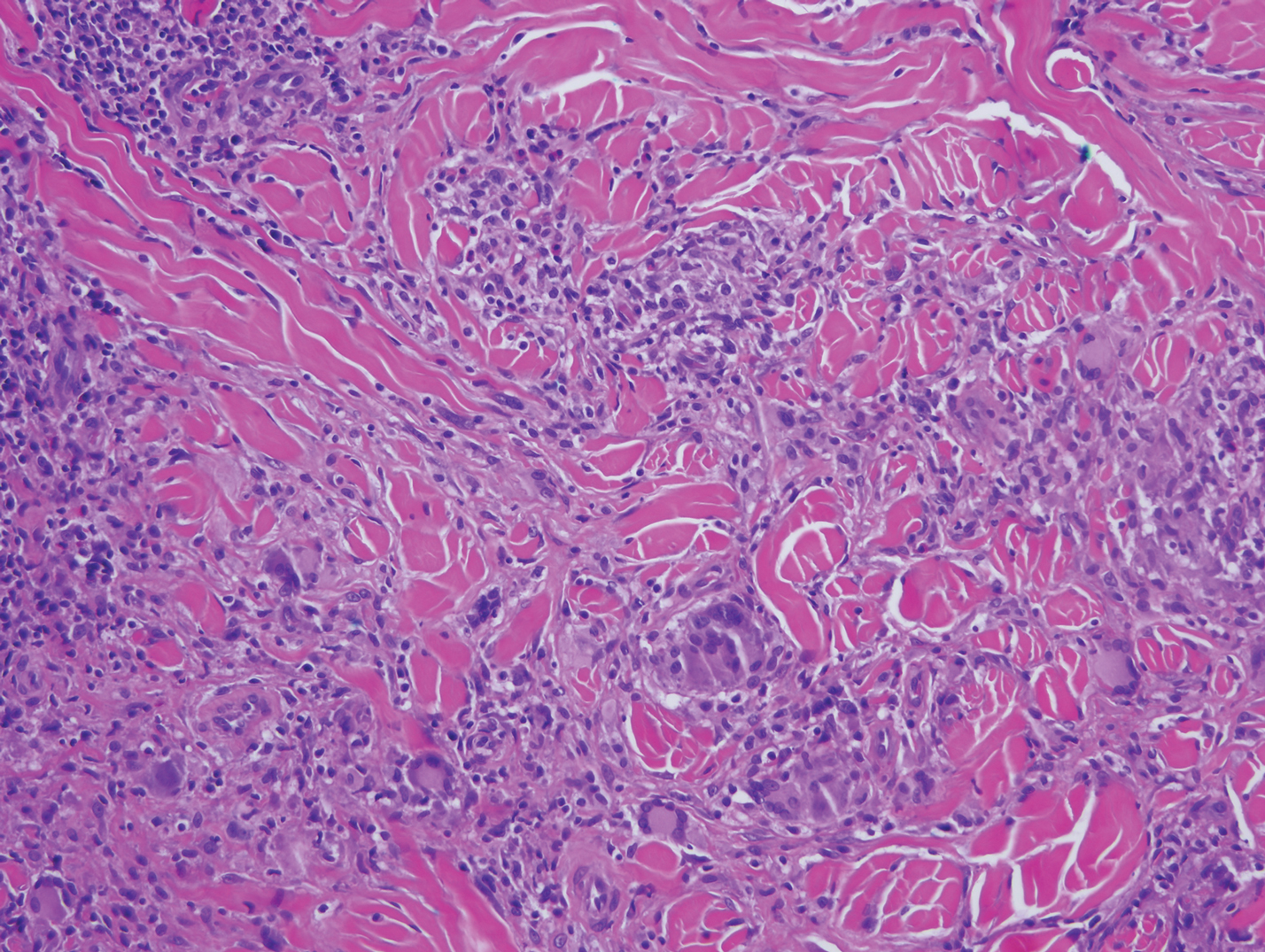

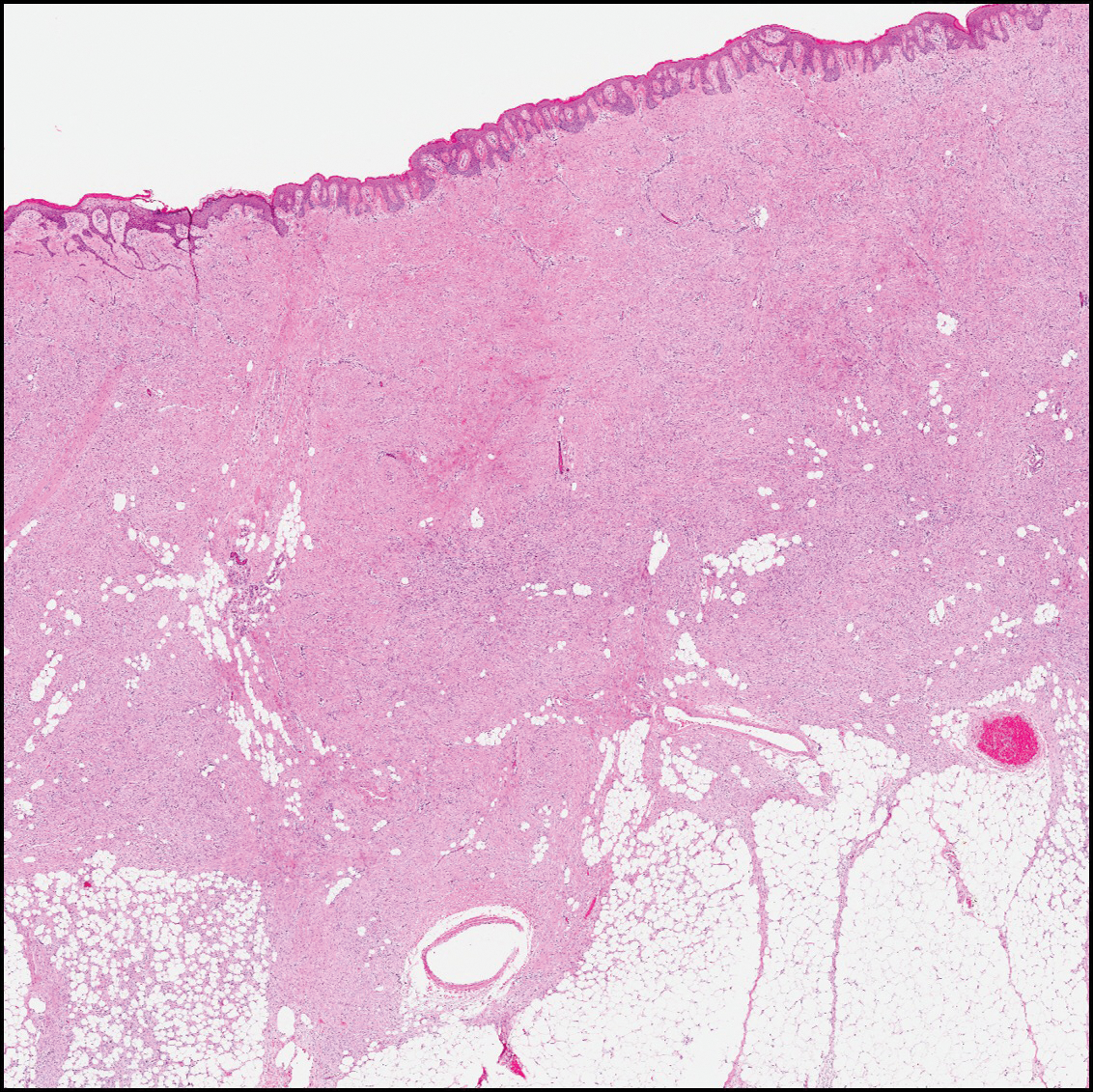

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

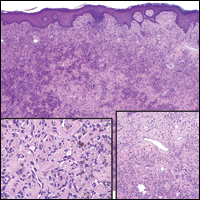

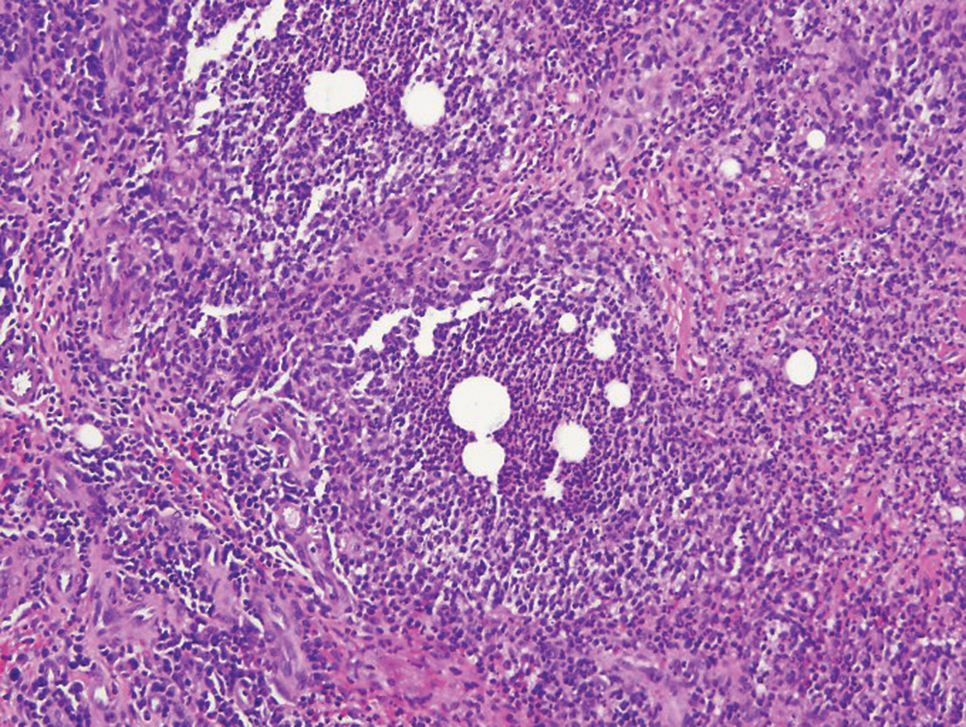

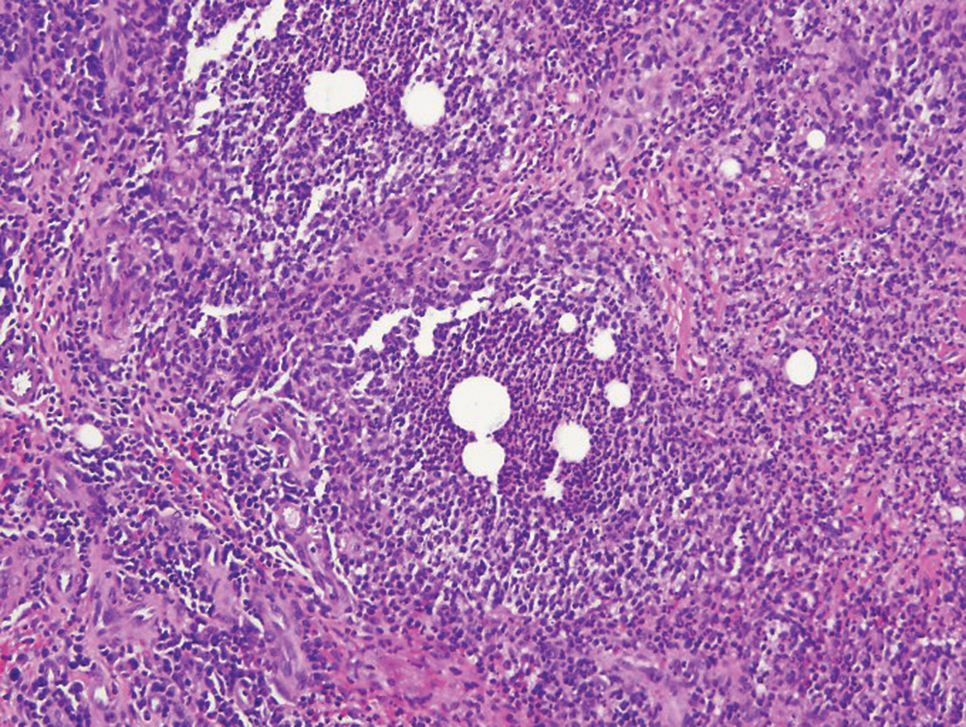

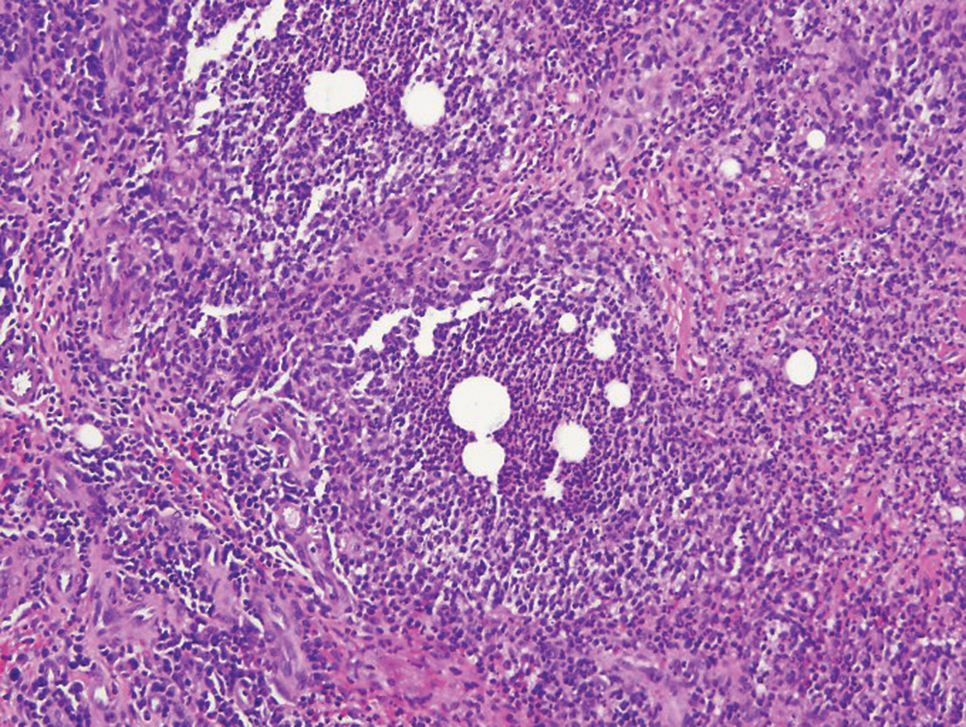

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

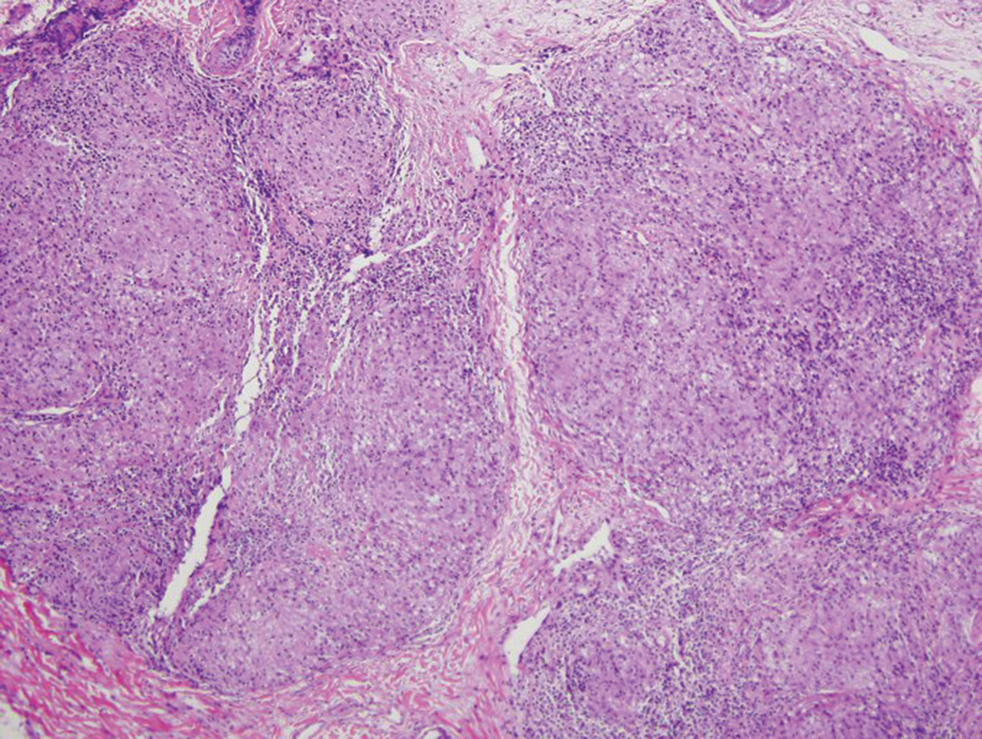

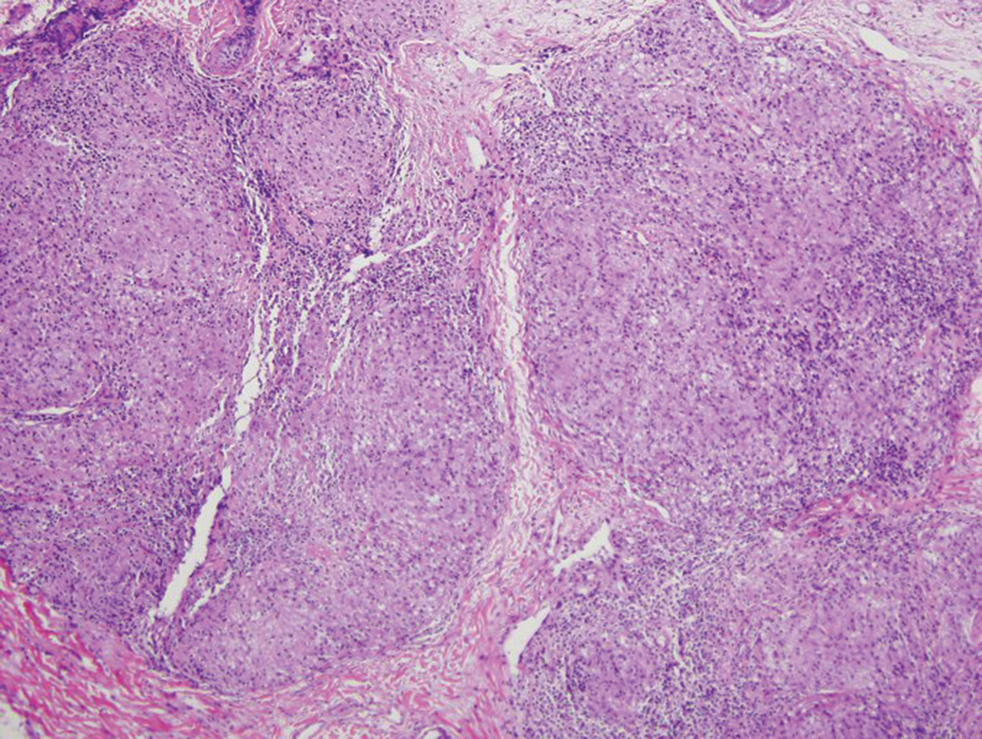

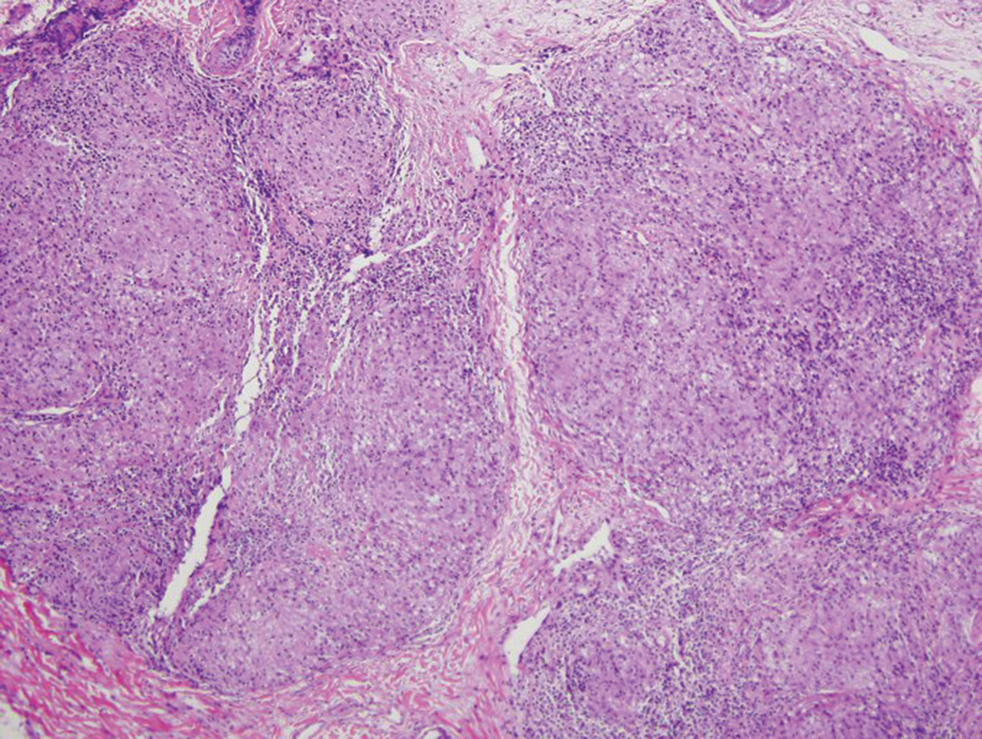

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

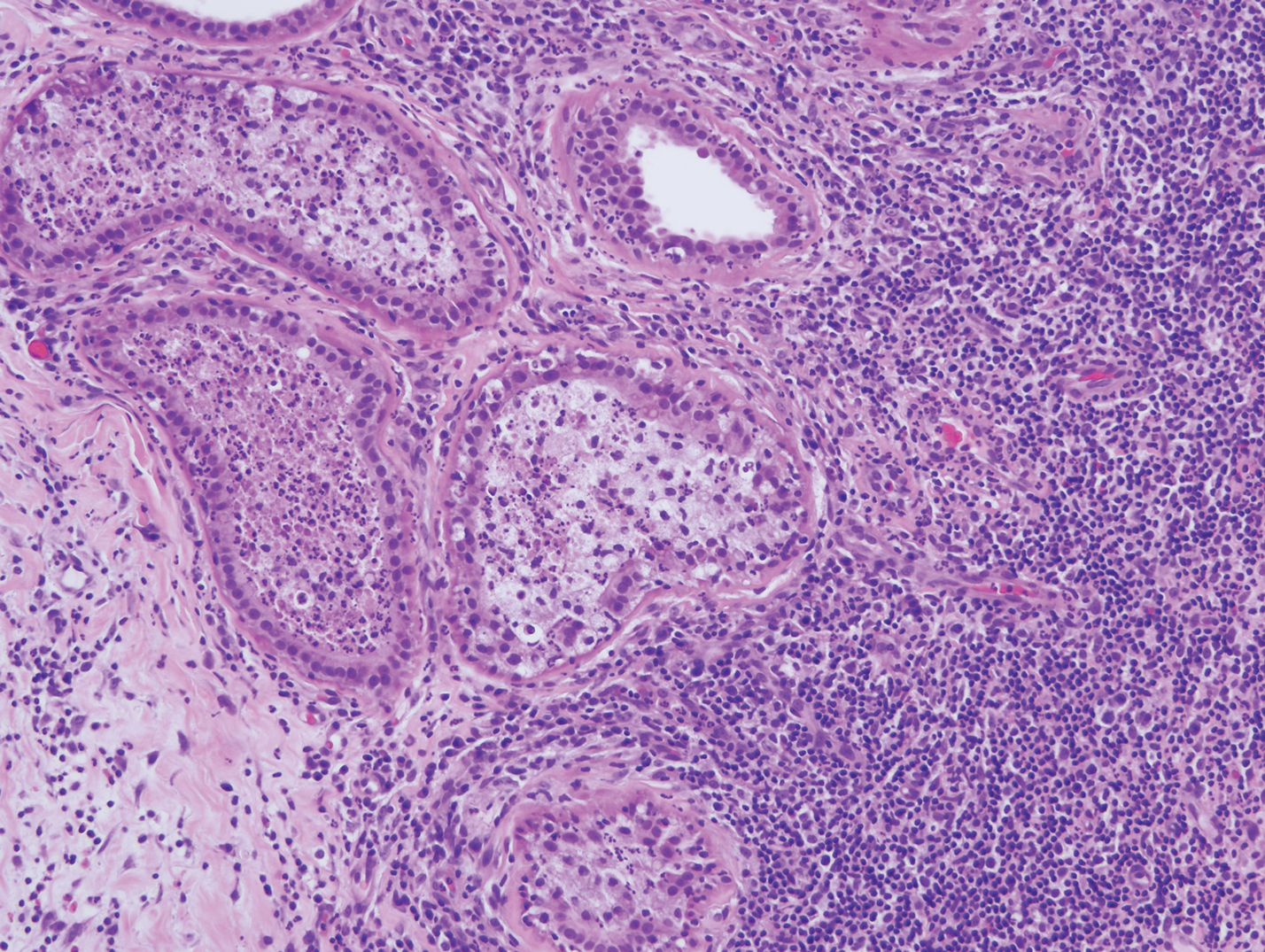

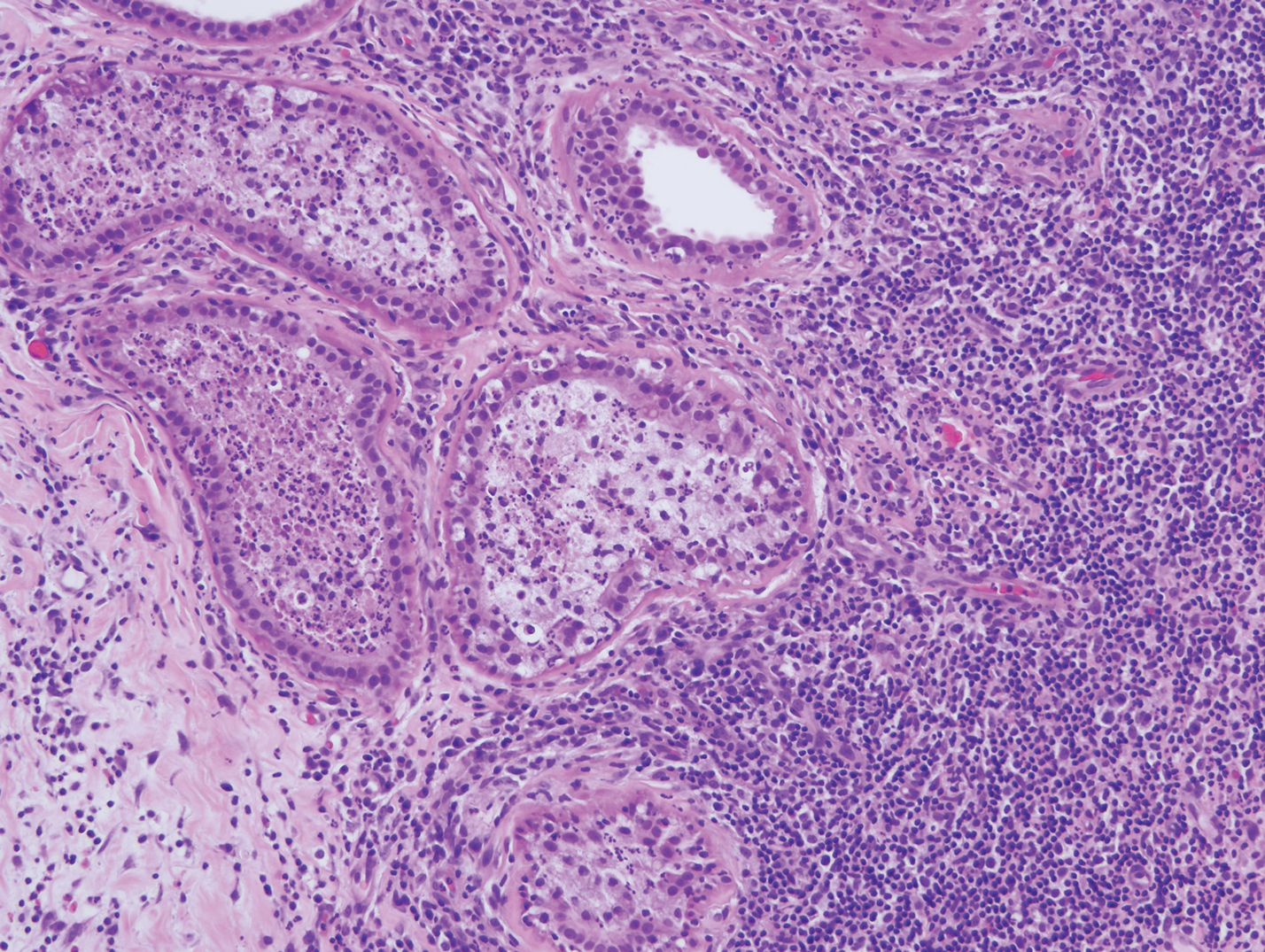

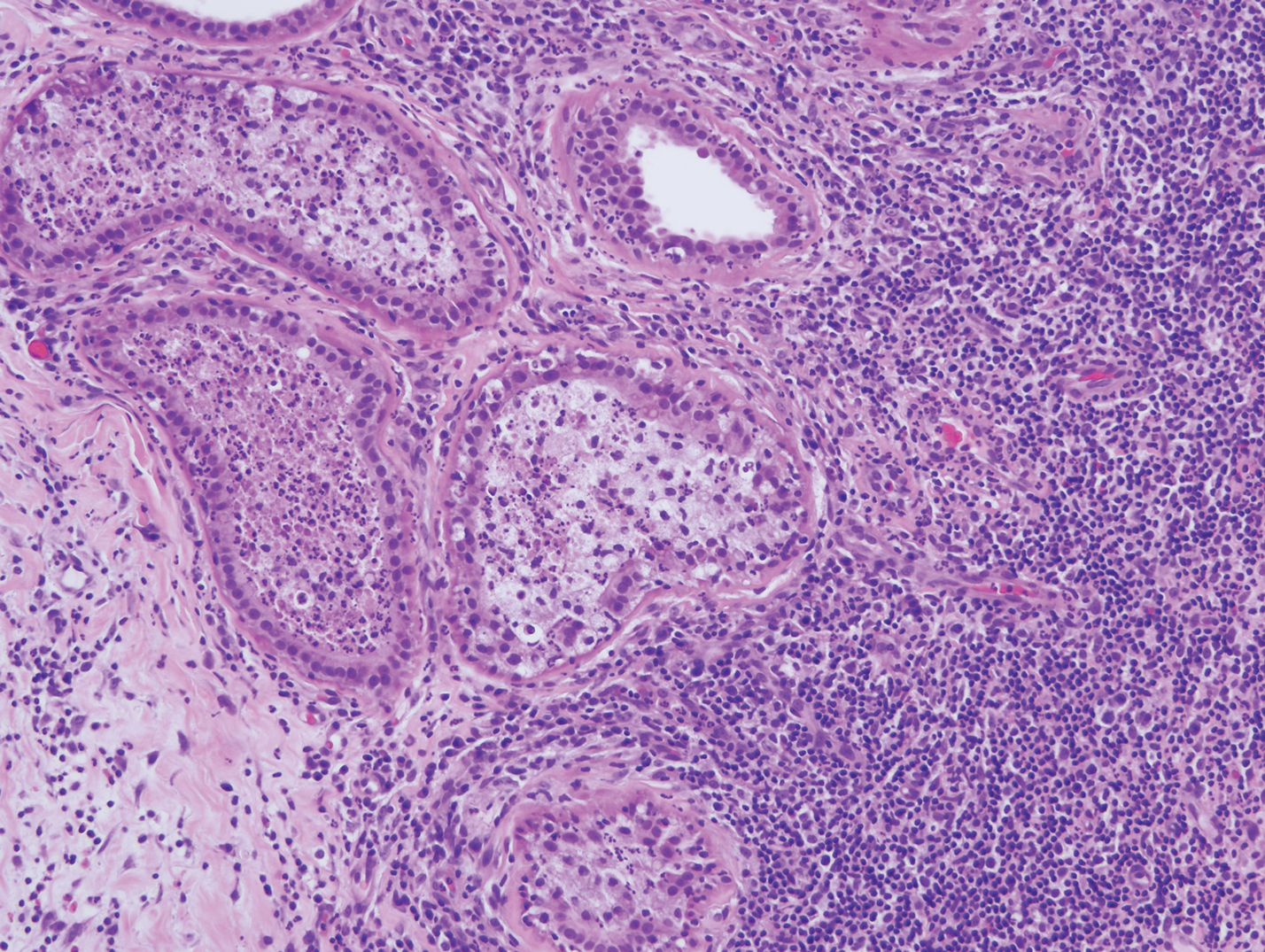

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

A 44-year-old man presented for evaluation of self-described "skin ripping" on the penis with penile and scrotal edema of 1 year's duration. He had a history of bowel symptoms and anorectal fistula of 3 years' duration. Purulent penile drainage and inguinal lymphadenopathy were noted on physical examination. Excisional biopsies of the scrotum and penis were performed. Special stains for organisms were negative.

Solitary Nodule With White Hairs

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

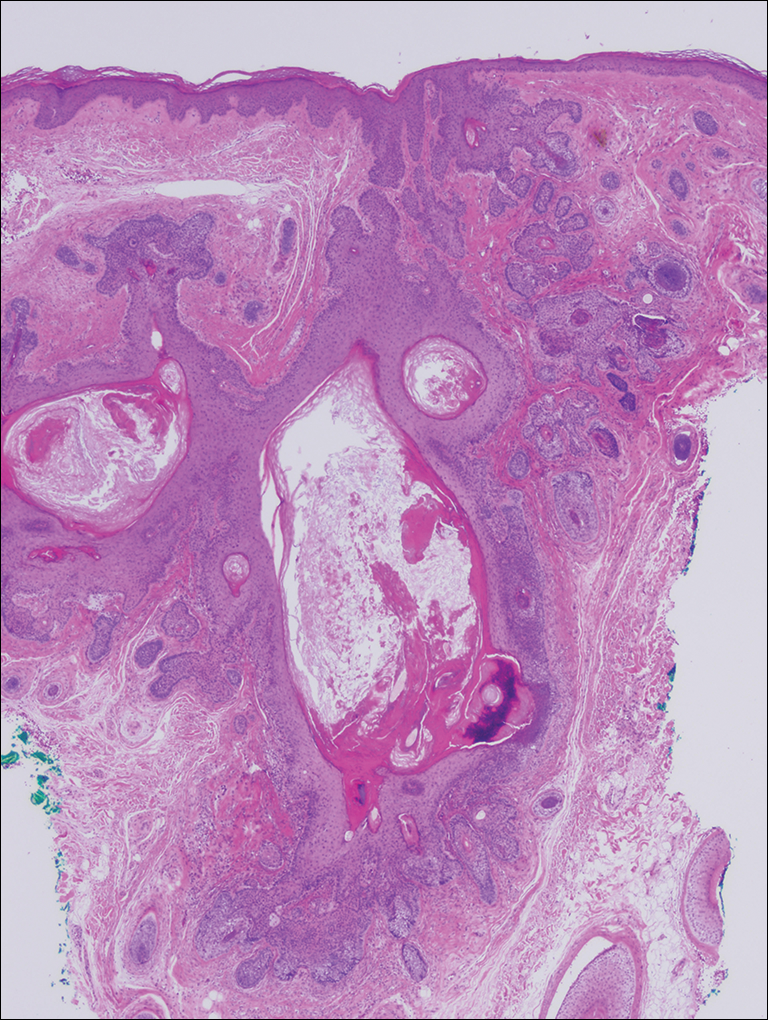

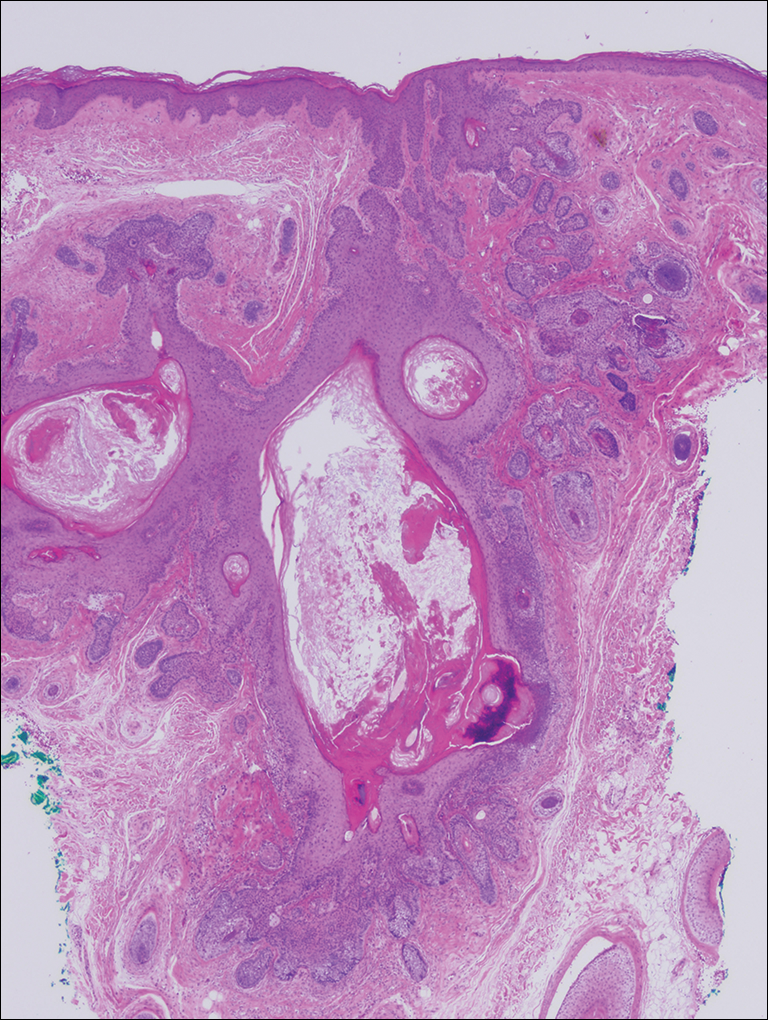

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

A 72-year-old man presented with a new asymptomatic 0.7-cm flesh-colored papule with a central tuft of white hairs on the posterior scalp. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm diagnosis.

Large Hyperpigmented Nodule on the Leg

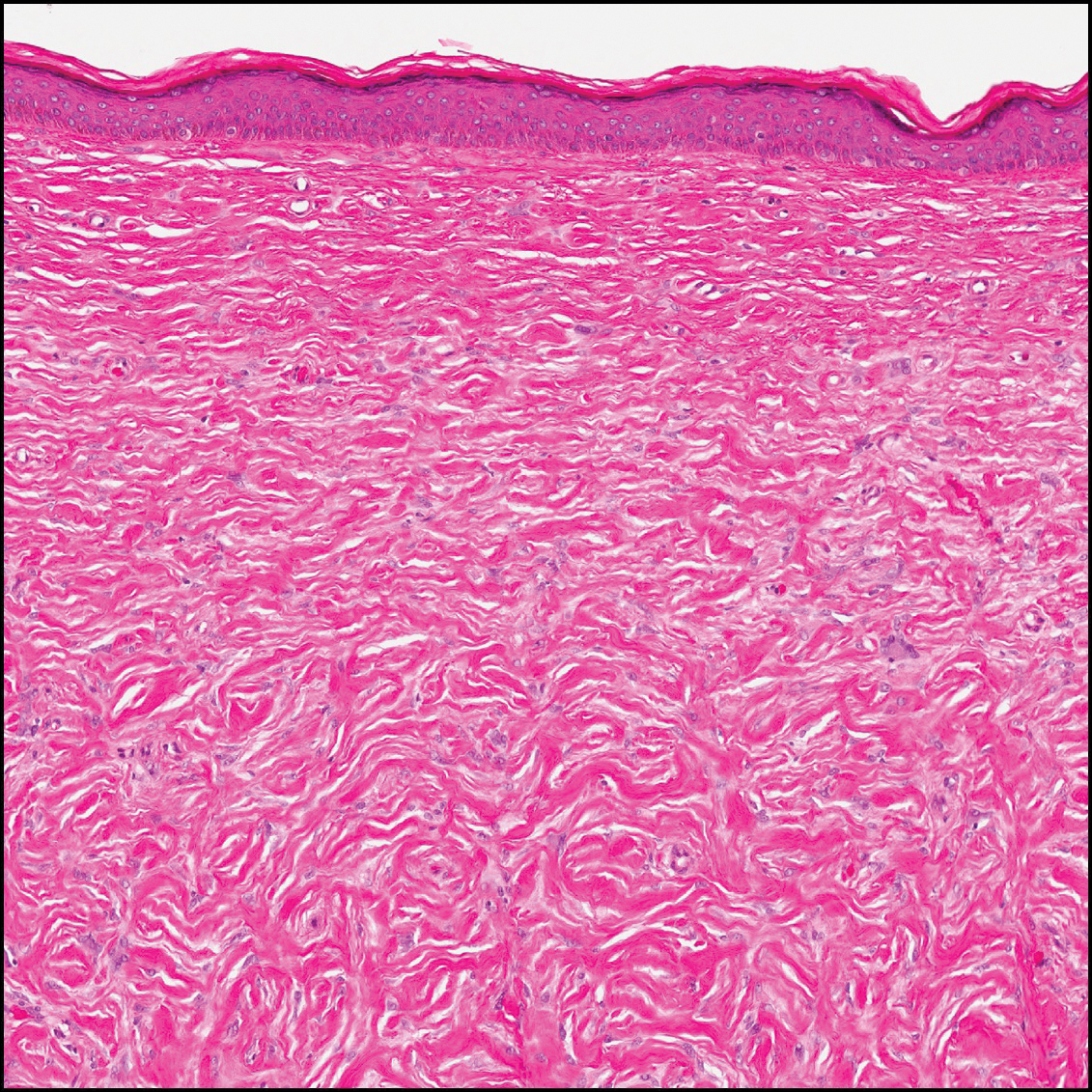

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

A 61-year-old woman presented with a 2.5-cm hyperpigmented exophytic nodule on the anterior aspect of the left shin of approximately 2 years' duration. The patient initially noticed a small lesion following a bee sting, but it subsequently grew over the ensuing 2 years. A shave biopsy was obtained.