User login

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

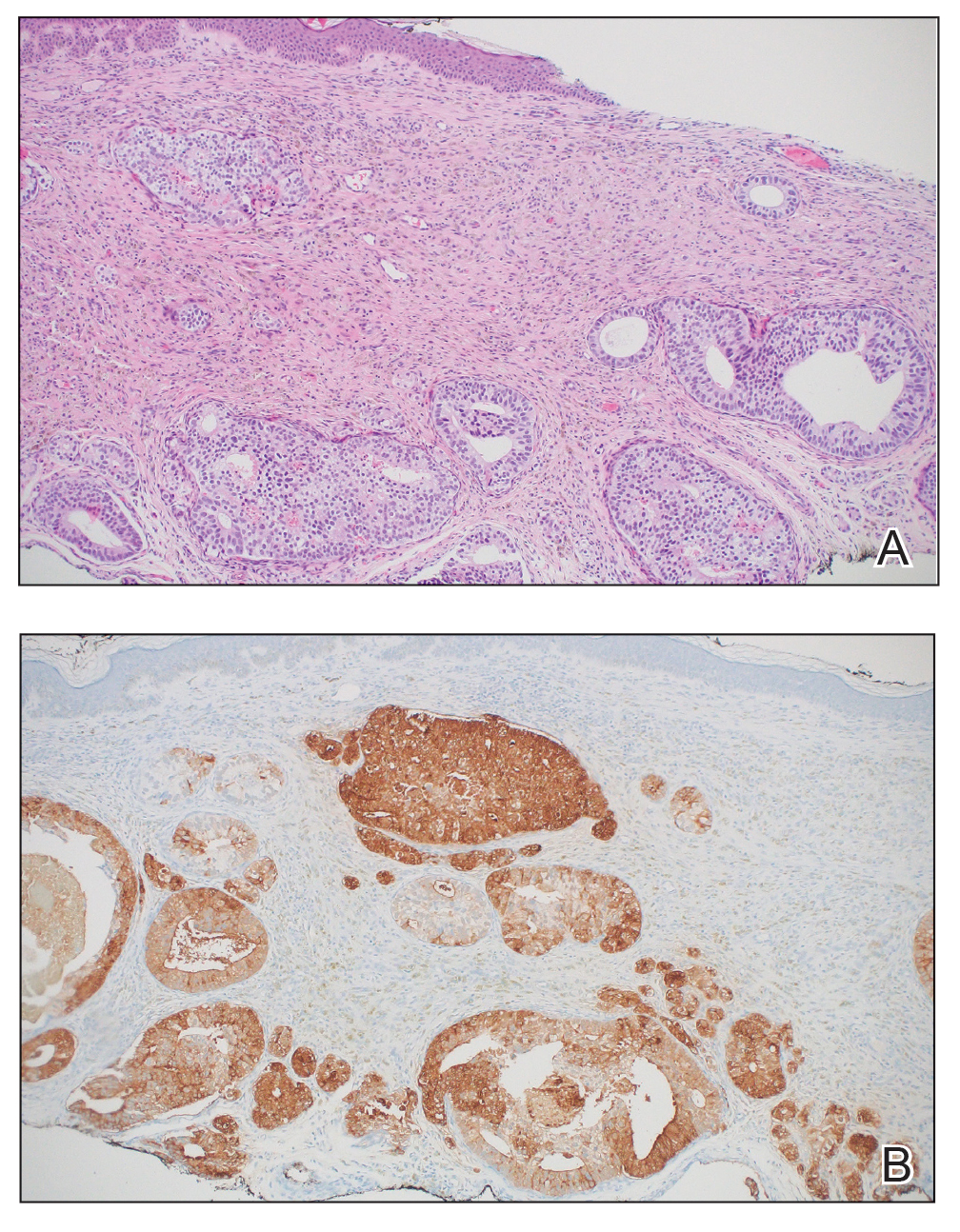

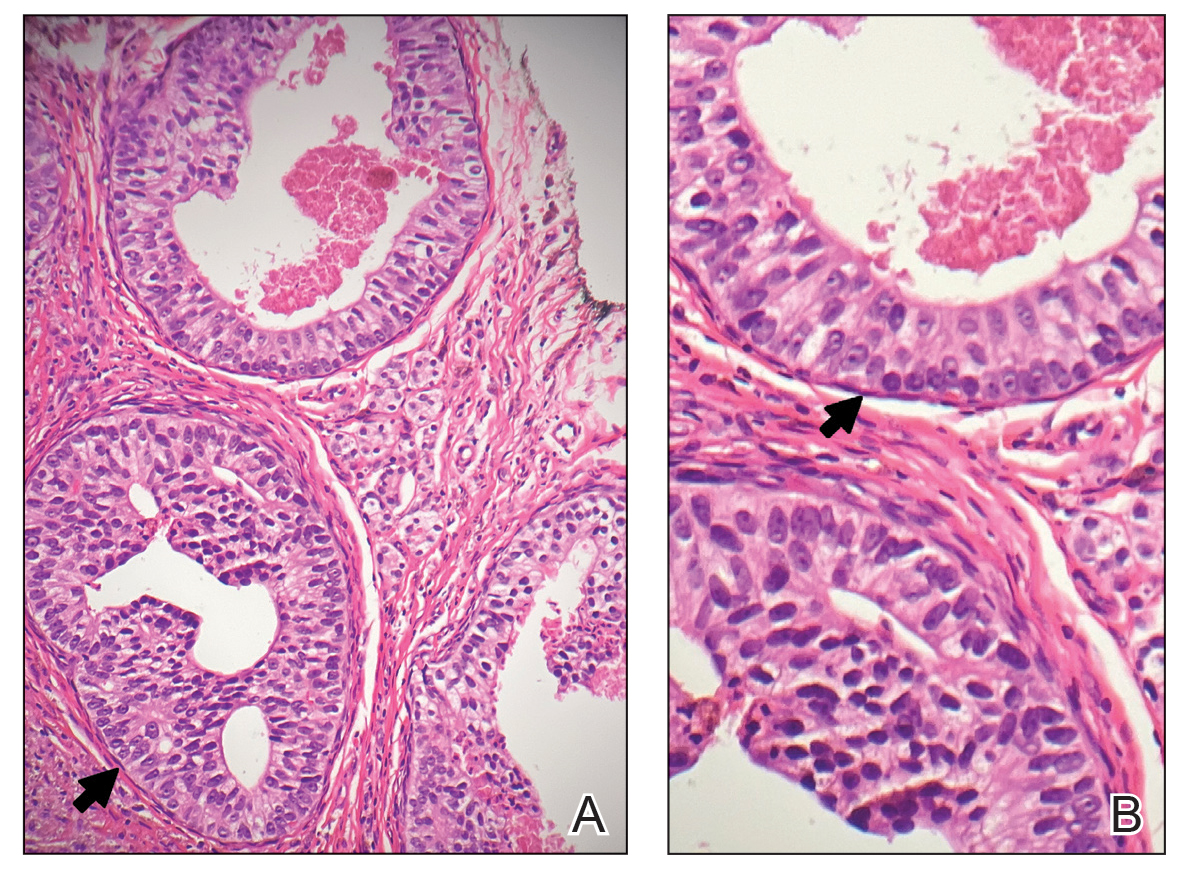

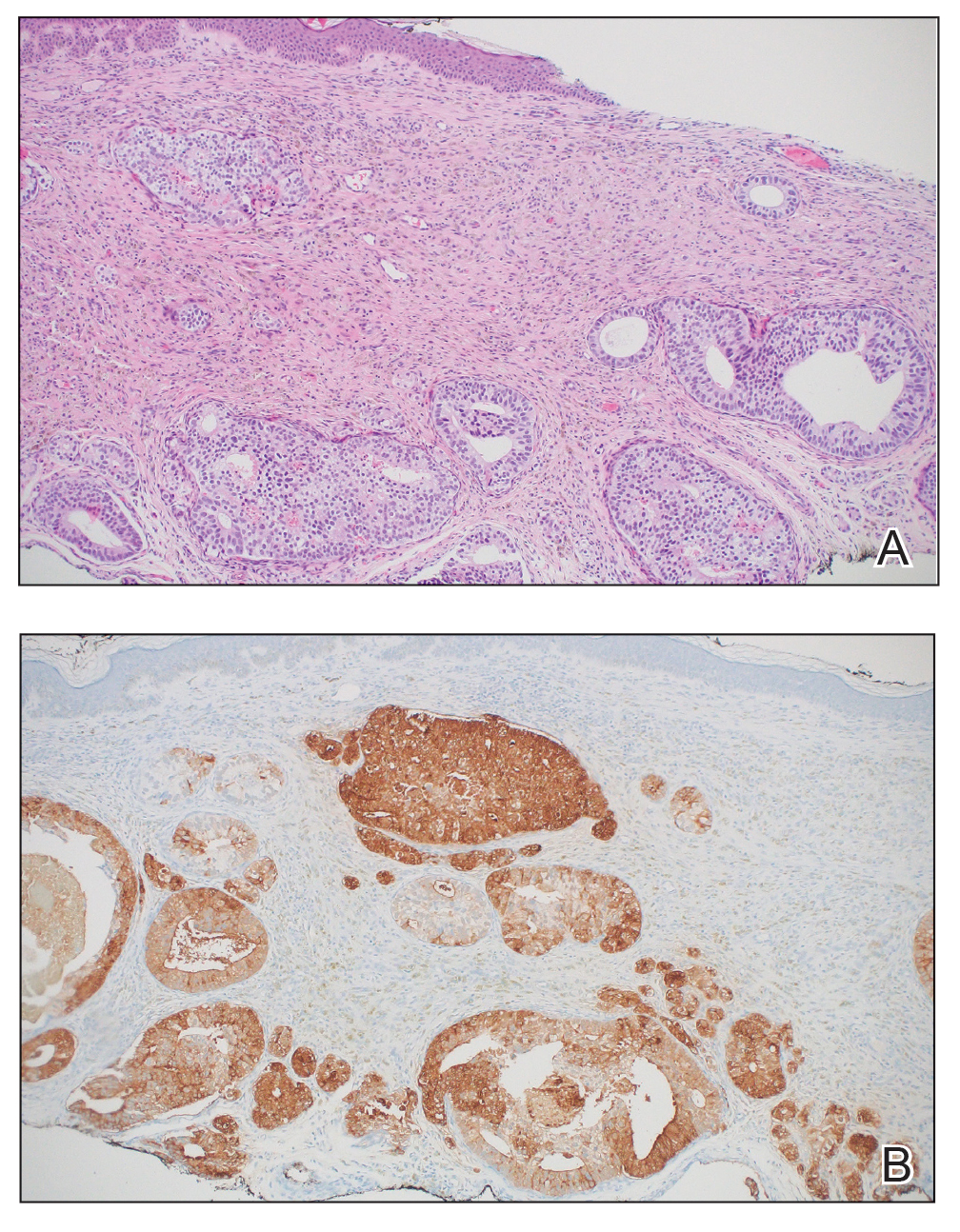

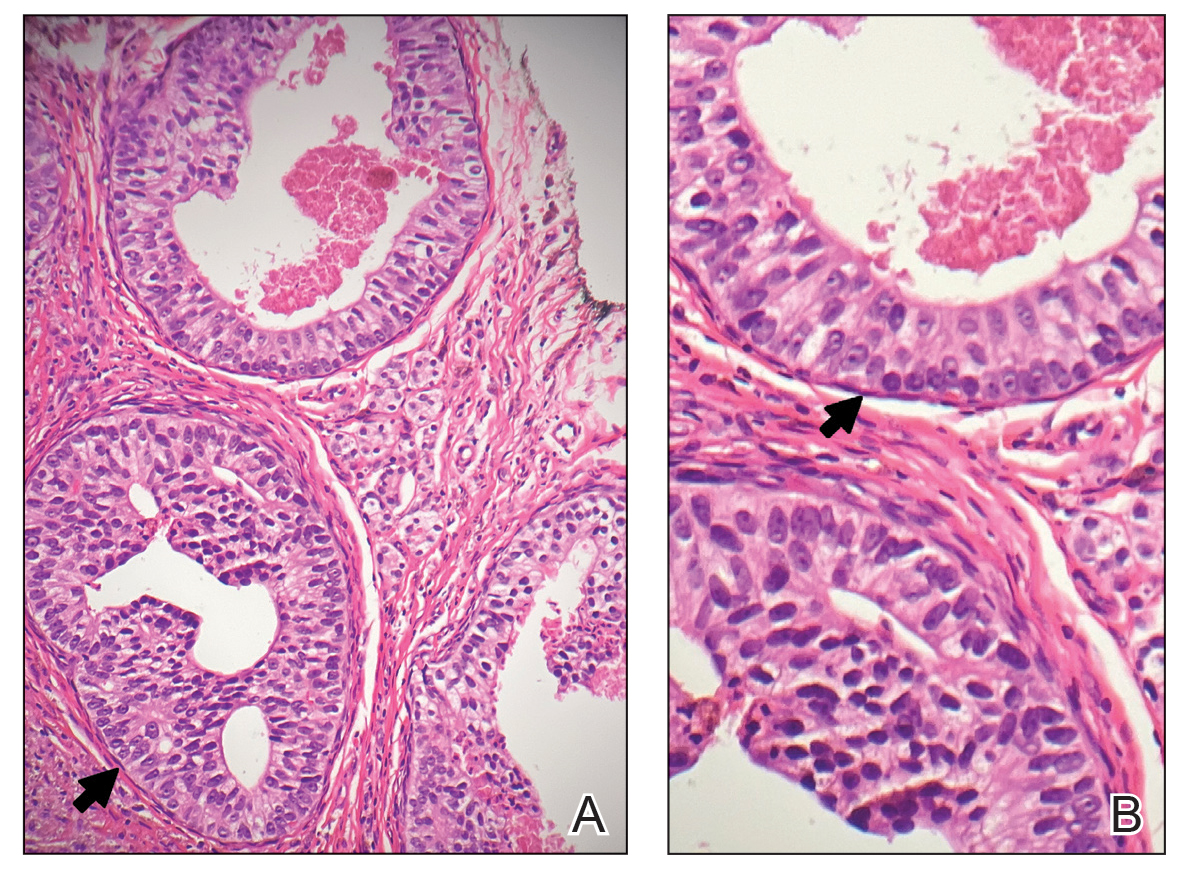

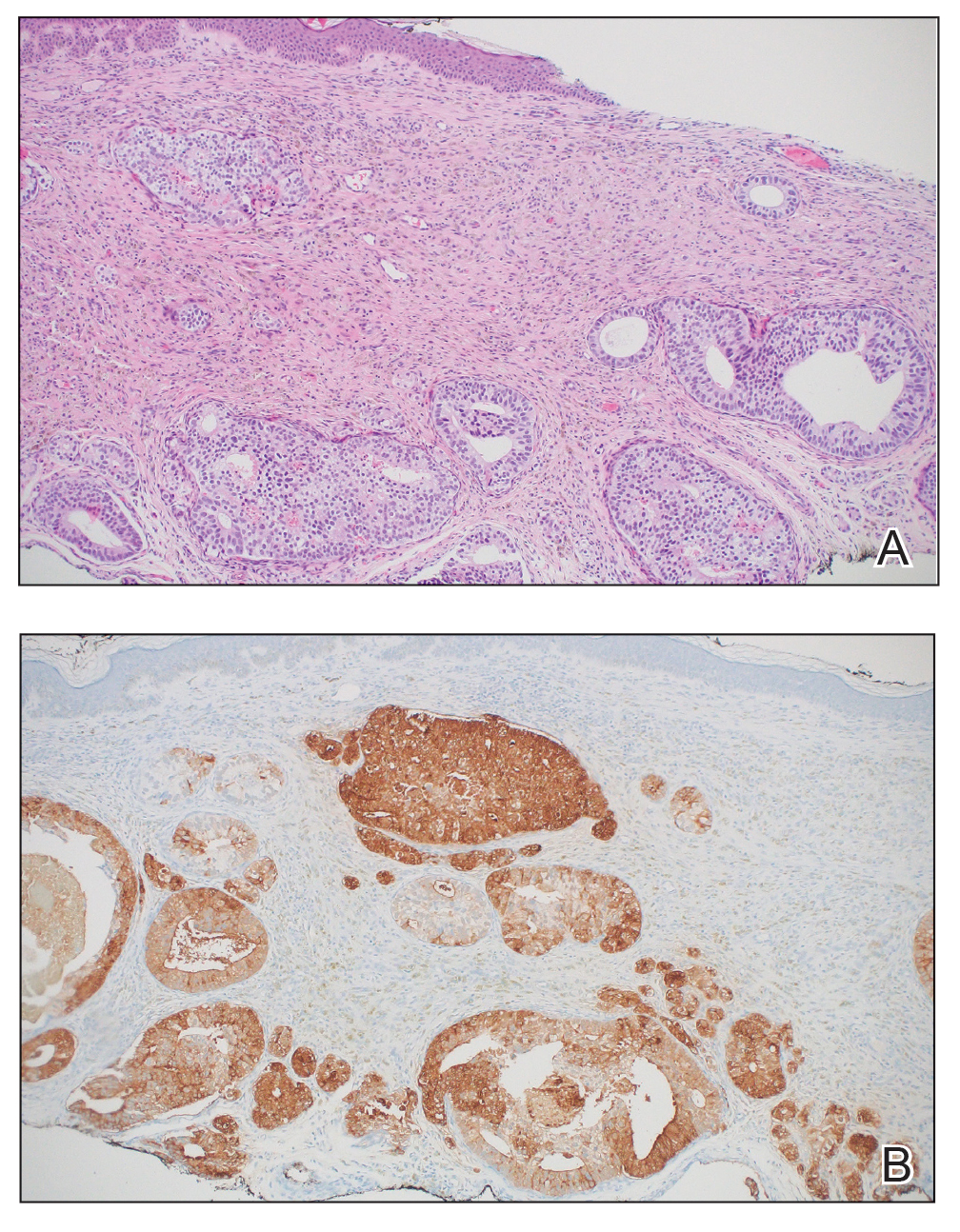

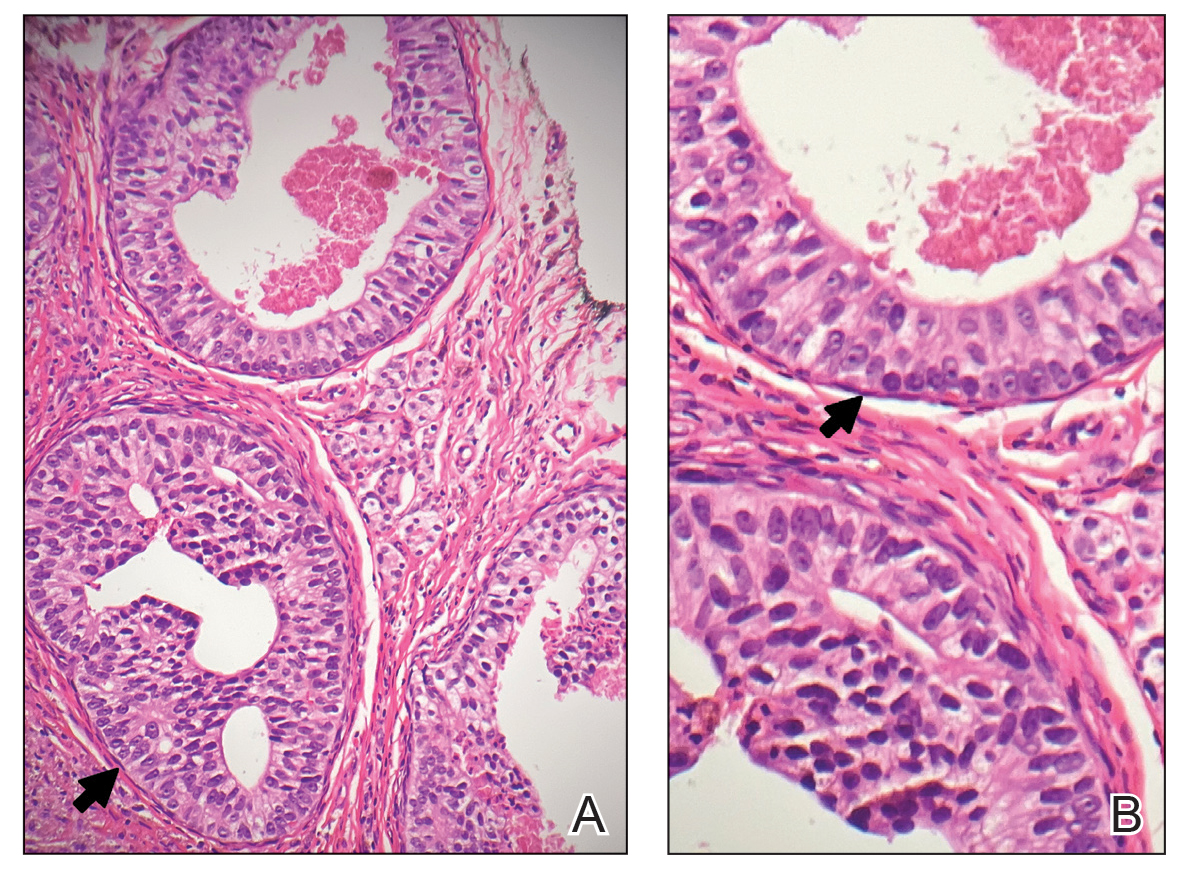

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

PRACTICE POINTS

- Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can have various manifestations and portends a poor prognosis.

- New skin lesions that develop in patients with a high clinical suspicion for prostate cancer warrant consideration of cutaneous metastasis.

A Case Series of Rare Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

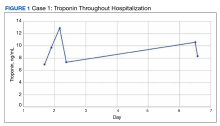

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

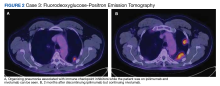

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

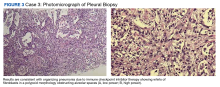

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351