User login

Pigmented Cystic Masses on the Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

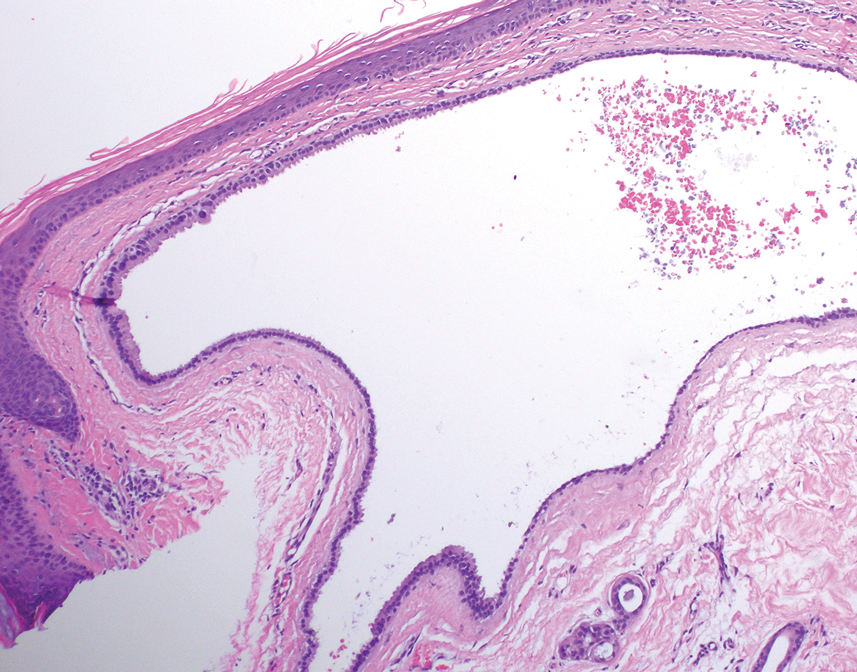

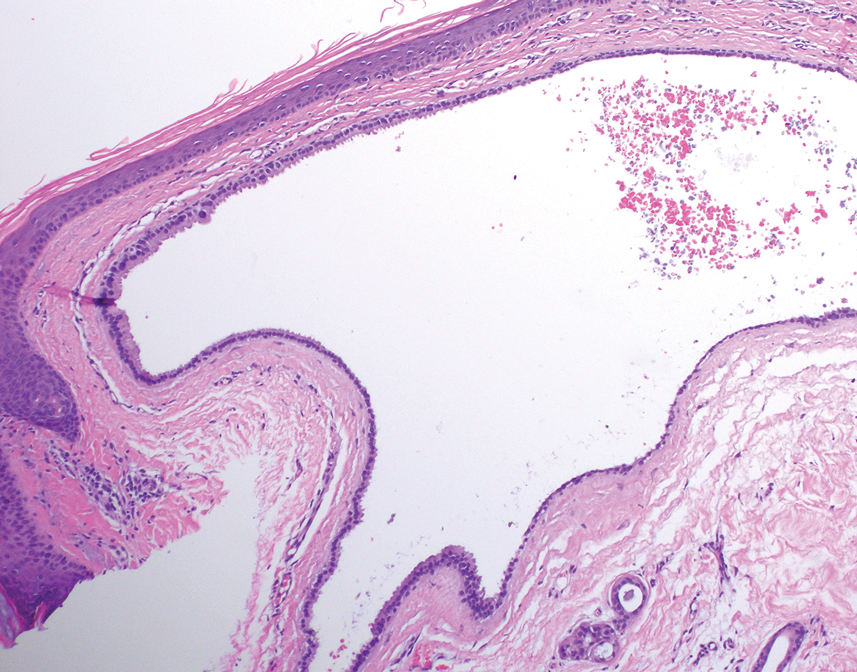

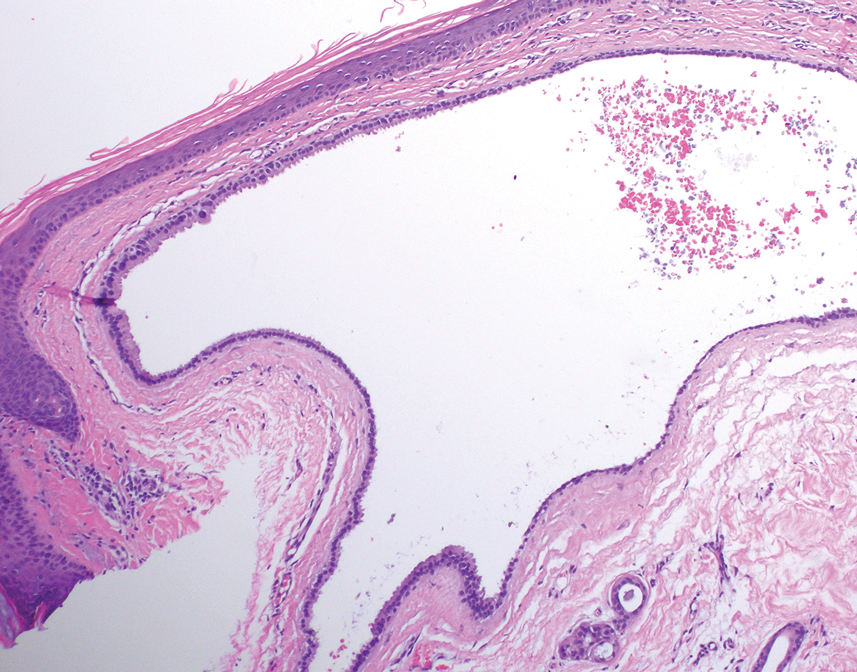

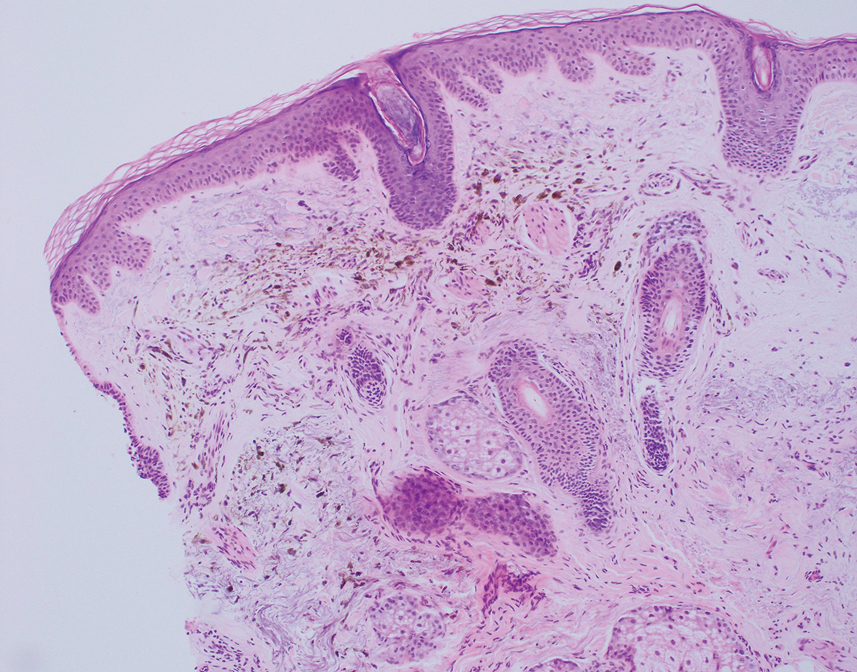

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

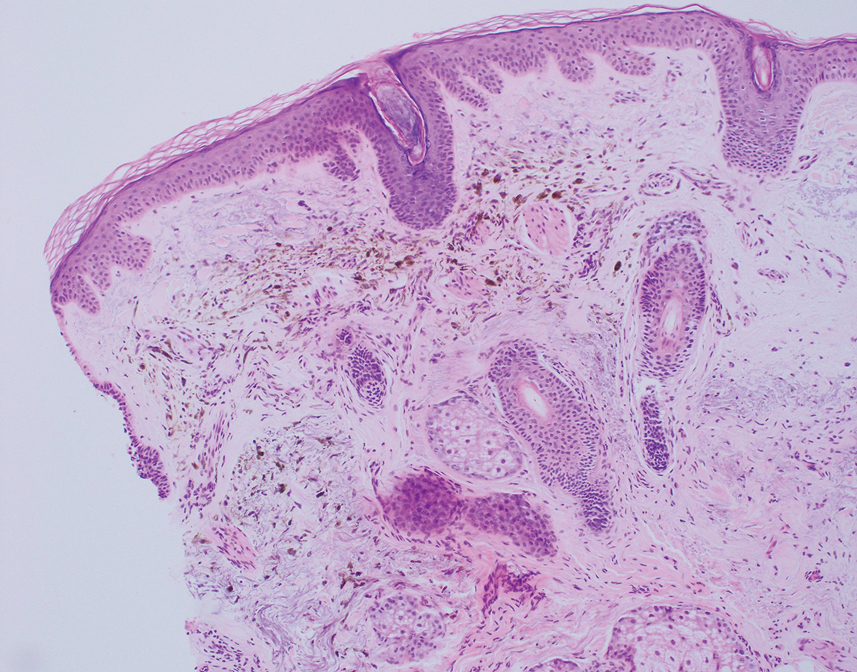

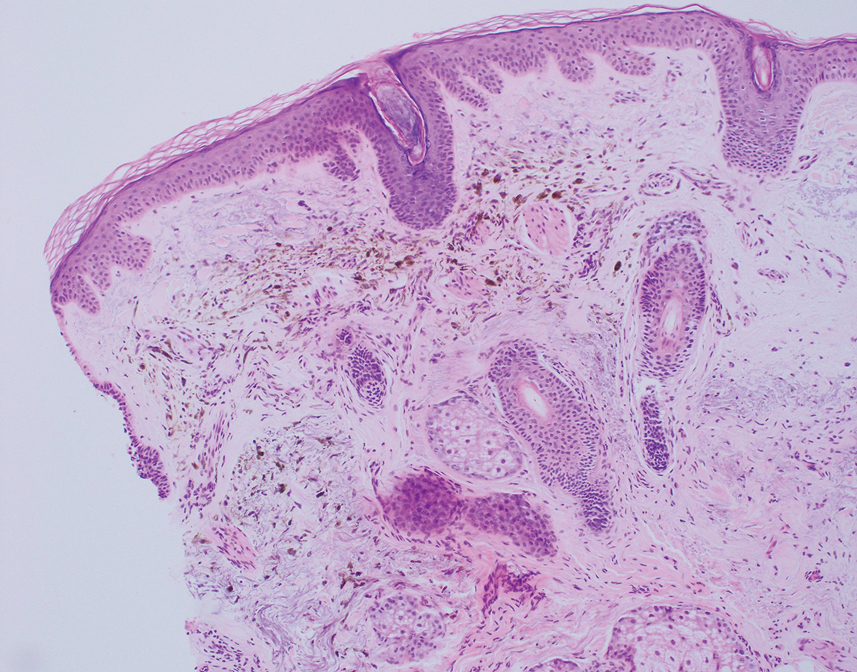

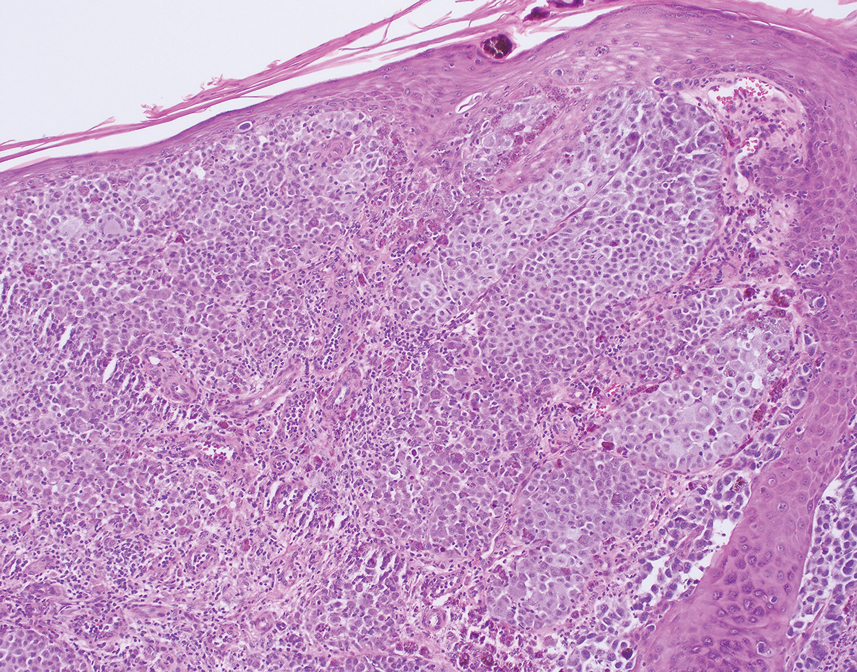

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

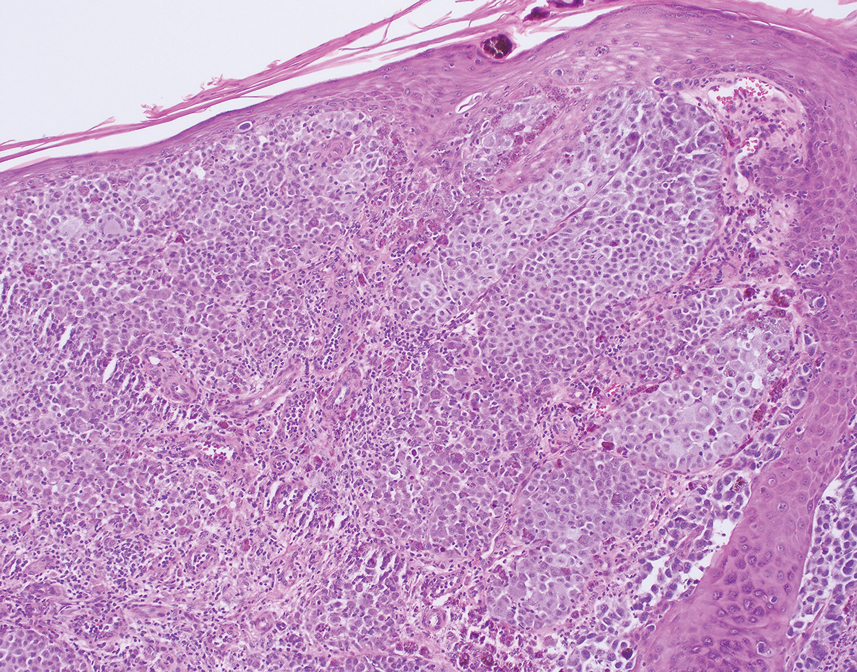

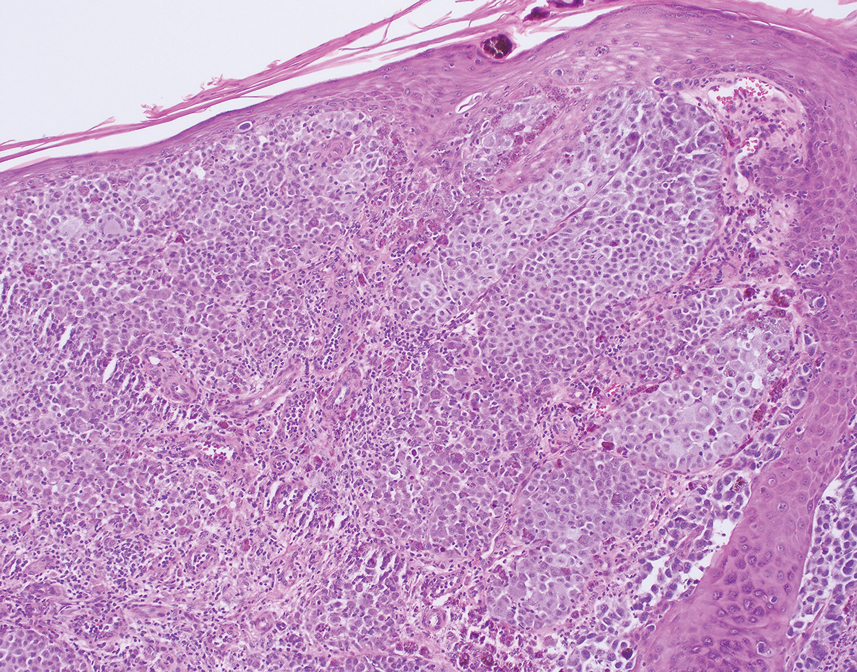

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 3 asymptomatic pigmented papules on the scalp. The patient reported that he was unaware of the lesions until they were pointed out weeks earlier by his primary care physician during a routine visit. He then was referred to dermatology for follow-up. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed clustered firm, smooth, well-circumscribed, pigmented papules on the scalp measuring 5 to 8 mm. The patient reported no personal or family history of skin cancer but stated that he spent a lot of time outdoors and had a history of 6 blistering sunburns in his life. A punch biopsy of each lesion was performed.

Management of a Child vs an Adult Presenting With Acral Lesions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Practical Review

There has been a rise in the prevalence of perniolike lesions—erythematous to violaceous, edematous papules or nodules on the fingers or toes—during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These lesions are referred to as “COVID toes.” Although several studies have suggested an association with these lesions and COVID-19, and coronavirus particles have been identified in endothelial cells of biopsies of pernio lesions, questions remain on the management, pathophysiology, and implications of these lesions.1 We provide a practical review for primary care clinicians and dermatologists on the current management, recommendations, and remaining questions, with particular attention to the distinctions for children vs adults presenting with pernio lesions.

Hypothetical Case of a Child Presenting With Acral Lesions

A 7-year-old boy presents with acute-onset, violaceous, mildly painful and pruritic macules on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to involve more toes and appear more purpuric. A review of symptoms reveals no fever, cough, fatigue, or viral symptoms. He has been staying at home for the last few weeks with his brother, mother, and father. His father is working in delivery services and is social distancing at work but not at home. His mother is concerned about the lesions, if they could be COVID toes, and if testing is needed for the patient or family. In your assessment and management of this patient, you consider the following questions.

What Is the Relationship Between These Clinical Findings and COVID-19?

Despite negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests reported in cases of chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the possibility that these lesions are an indirect result of environmental factors or behavioral changes during quarantine, the majority of studies favor an association between these chilblains lesions and COVID-19 infection.2,3 Most compellingly, COVID-19 viral particles have been identified by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in the endothelial cells of biopsies of these lesions.1 Additionally, there is evidence for possible associations of other viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19, with chilblains lesions.4,5 In sum, with the lack of any large prospective study, the weight of current evidence suggests that these perniolike skin lesions are not specific markers of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).6

Published studies differ in reporting the coincidence of perniolike lesions with typical COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and anosmia, among others. Some studies have reported that up to 63% of patients with reported perniolike lesions developed typical COVID-19 symptoms, but other studies found that no patients with these lesions developed symptoms.6-11 Studies with younger cohorts tended to report lower prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms, and within cohorts, younger patients tended to have less severe symptoms. For example, 78.8% of patients in a cohort (n=58) with an average age of 14 years did not experience COVID-19–related symptoms.6 Based on these data, it has been hypothesized that patients with chilblainslike lesions may represent a subpopulation who will have a robust interferon response that is protective from more symptomatic and severe COVID-19.12-14

Current evidence suggests that these lesions are most likely to occur between 9 days and 2 months after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.4,9,10 Most cases have been only mildly symptomatic, with an overall favorable prognosis of both lesions and any viral symptoms.8,10 The lesions typically resolve without treatment within a few days of initial onset.15,16

What Should Be the Workup and Management of These Lesions?

Given the currently available information and favorable prognosis, usually no further workup specific to the perniolike lesions is required in the case of an asymptomatic child presenting with acral lesions, and the majority of management will center around patient and parent/guardian education and reassurance. When asked by the patient’s parent, “What does it mean that my child has these lesions?”, clinicians can provide information on the possible association with COVID-19 and the excellent, self-resolving prognosis. An example of honest and reasonable phrasing with current understanding might be, “We are currently not certain if COVID-19 causes these lesions, although there are data to suggest that they are associated. There are a lot of data showing that children with these lesions either do not have any symptoms or have very mild symptoms that resolve without treatment.”

For management, important considerations include how painful the lesions are to the individual patient and how they affect quality of life. If less severe, clinicians can reassure patients and parents/guardians that the lesions will likely self-resolve without treatment. If worsening or symptomatic, clinicians can try typical treatments for chilblains, such as topical steroids, whole-body warming, and nifedipine.17-19 Obtaining a review of symptoms, including COVID-19 symptoms and general viral symptoms, is important given the rare cases of children with severe COVID-19.20,21

The question of COVID-19 testing as related to these lesions remains controversial, and currently there are still differing perspectives on the need for biopsy, PCR for COVID-19, or serologies for COVID-19 in patients presenting with these lesions. Some experts report that additional testing is not needed in the pediatric population because of the high frequency of negative testing reported to date.22,23 However, these children may be silent carriers, and until more is known about their potential to transmit the virus, testing may be considered if resources allow, particularly if the patient has a known exposure.10,12,16,24 The ultimate decision to pursue biopsy or serologic workup for COVID-19 remains up to clinical discretion with consideration of symptoms, severity, and immunocompromised household contacts. If lesions developed after infection, PCR likely will result negative, whereas serologic testing may reveal antibodies.

Hypothetical Case of an Adult Presenting With Acral Lesions and COVID-19 Symptoms

A 50-year-old man presents with acute-onset, violaceous, painful, edematous plaques on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to include the soles. A review of symptoms reveals fever (temperature, 38.4 °C [101 °F]), cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, and severe asthenia. He has had interactions with a coworker who recently tested positive for COVID-19.

How Should You Consider These Lesions in the Context of the Other Symptoms Concerning for COVID-19?

In contrast to the asymptomatic child above, this adult has chilblainslike lesions and viral symptoms. In adults, chilblainslike lesions have been associated with relatively mild COVID-19, and patients with these lesions who are otherwise asymptomatic have largely tested negative for COVID-19 by PCR and serologic antibody testing.11,25,26

True acral ischemia, which is more severe and should be differentiated from chilblains, has been reported in critically ill patients.9 Additionally, studies have found that retiform purpura is the most common cutaneous finding in patients with severe COVID-19.27 For this patient, who has an examination consistent with progressive and severe chilblainslike lesions and suspicion for COVID-19 infection, it is important to observe and monitor these lesions, as clinical progression suggestive of acral ischemia or retiform purpura should be taken seriously and may indicate worsening of the underlying disease. Early intervention with anticoagulation might be considered, though there currently is no evidence of successful treatment.28

What Causes These Lesions in a Patient With COVID-19?

The underlying pathophysiology has been proposed to be a monocytic-macrophage–induced hyperinflammatory systemic state that damages the lungs, as well as the gastrointestinal, renal, and endothelial systems. The activation of the innate immune system triggers a cytokine storm that creates a hypercoagulable state that ultimately can manifest as superficial thromboses, leading to gangrene of the extremities. Additionally, interferon response and resulting hypercytokinemia may cause direct cytopathic damage to the endothelium of arterioles and capillaries, causing the development of papulovesicular lesions that resemble the chilblainslike lesions observed in children.29 In contrast to children, who typically have no or mild COVID-19 symptoms, adults may have a delayed interferon response, which has been proposed to allow for more severe manifestations of infection.12,30

How Should an Adult With Perniolike Lesions Be Managed?

Adults with chilblainslike lesions and no other signs or symptoms of COVID-19 infection do not necessarily need be tested for COVID-19, given the reports demonstrating most patients in this clinical situation will have negative PCRs and serologies for antibodies. However, there have been several reports of adults with acro-ischemic skin findings who also had severe COVID-19, with an observed incidence of 23% in intensive care unit patients with COVID-19.27,28,31,32 If there is suspicion of infection with COVID-19, it is advisable to first obtain workup for COVID-19 and other viruses that can cause acral lesions, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus. Other pertinent laboratory tests may include D-dimer, fibrinogen, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, antithrombin activity, platelet count, neutrophil count, procalcitonin, triglycerides, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and hemoglobin. For patients with evidence of worsening acro-ischemia, regular monitoring of these values up to several times per week can allow for initiation of vascular intervention, including angiontensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, or antiplatelet drugs.32 The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies also has been associated with critically ill patients who develop digit ischemia as part of the sequelae of COVID-19 infection and therefore may act as an important marker for the potential to develop disseminated intravascular coagulation in this patient.33 Even if COVID-19 infection is not suspected, a thorough review of systems is important to look for an underlying connective tissue disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, which is associated with pernio. Associated symptoms may warrant workup with antinuclear antibodies and other appropriate autoimmune serologies.

If there is any doubt of the diagnosis, the patient is experiencing symptoms from the lesion, or the patient is experiencing other viral symptoms, it is appropriate to biopsy immediately to confirm the diagnosis. Prior studies have identified fibrin clots, angiocentric and eccrinotropic lymphocytic infiltrates, lymphocytic vasculopathy, and papillary dermal edema as the most common features in chilblainslike lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic.9

For COVID-19 testing, many studies have revealed adult patients with an acute hypercoagulable state testing positive by SARS-CoV-2 PCR. These same patients also experienced thromboembolic events shortly after testing positive for COVID-19, which suggests that patients with elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen likely will have a viral load that is sufficient to test positive for COVID-19.32,34-36 It is appropriate to test all patients with suspected COVID-19, especially adults who are more likely to experience adverse complications secondary to infection.

This patient experiencing COVID-19 symptoms with signs of acral ischemia is likely to test positive by PCR, and additional testing for serologic antibodies is unlikely to be clinically meaningful in this patient’s state. Furthermore, there is little evidence that serology is reliable because of the markedly high levels of both false-negative and false-positive results when using the available antibody testing kits.37 The latter evidence makes serology testing of little value for the general population, but particularly for patients with acute COVID-19.

Conclusion and Outstanding Questions

There is evidence suggesting an association between chilblainslike lesions and COVID-19.11,22,38,39 Children presenting with these lesions have an excellent prognosis and only need a workup or treatment if there are other symptoms, as the lesions self-resolve in the majority of reported cases.7-9 Adults presenting with these lesions and without symptoms likewise are unlikely to test positive for COVID-19, and the lesions typically resolve spontaneously or with first-line treatment. However, adults presenting with these lesions and COVID-19 symptoms should raise clinical concern for evolving skin manifestations of acro-ischemia. If the diagnosis is uncertain or systemic symptoms are concerning, biopsy, COVID-19 PCR, and other appropriate laboratory workup should be obtained.

There remains controversy and uncertainty over the relationship between these skin findings and SARS-CoV-2 infection, with clinical evidence to support both a direct relationship representing convalescent-phase cutaneous reaction as well as an indirect epiphenomenon. If there was a direct relationship, we would have expected to see a rise in the incidence of acral lesions proportionate to the rising caseload of COVID-19 after the reopening of many states in the summer of 2020. Similarly, because young adults represent the largest demographic of increasing cases and as some schools have remained open for in-person instruction during the current academic year, we also would have expected the incidence of chilblains-like lesions presenting to dermatologists and pediatricians to increase alongside these cases. Continued evaluation of emerging literature and ongoing efforts to understand the cause of this observed phenomenon will hopefully help us arrive at a future understanding of the pathophysiology of this puzzling skin manifestation.40

- Colmenero I, Santonja C, Alonso-Riaño M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of seven paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:729-737. doi:10.1111/bjd.19327

- Neri I, Virdi A, Corsini I, et al. Major cluster of paediatric “true” primary chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic: a consequence of lifestyle changes due to lockdown. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2630-2635. doi:10.1111/jdv.16751

- Hubiche T, Le Duff F, Chiaverini C, et al. Negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR in patients with chilblain-like lesions [letter]. Lancet Infect Dis. June 18, 2020. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30518-1

- Pistorius MA, Blaise S, Le Hello C, et al. Chilblains and COVID19 infection: causality or coincidence? How to proceed? J Med Vasc. 2020;45:221-223. doi:10.1016/j.jdmv.2020.05.002

- Massey PR, Jones KM. Going viral: a brief history of Chilblain-like skin lesions (“COVID toes”) amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin Oncol. 2020;47:330-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.05.012

- Docampo-Simón A, Sánchez-Pujol MJ, Juan-Carpena G, et al. Are chilblain-like acral skin lesions really indicative of COVID-19? A prospective study and literature review [letter]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e445-e446. doi:10.1111/jdv.16665

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Concato C, et al. A clinical, histopathological and laboratory study of 19 consecutive Italian paediatric patients with chilblain-like lesions: lights and shadows on the relationship with COVID-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2620-2629. doi:10.1111/jdv.16682

- Recalcati S, Barbagallo T, Frasin LA, et al. Acral cutaneous lesions in the time of COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e346-e347. doi:10.1111/jdv.16533

- Andina D, Noguera-Morel L, Bascuas-Arribas M, et al. Chilblains in children in the setting of COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:406-411. doi:10.1111/pde.14215

- Casas CG, Català A, Hernández GC, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathologic findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:489-492. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011

- Damsky W, Peterson D, King B. When interferon tiptoes through COVID-19: pernio-like lesions and their prognostic implications during SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E269-E270. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.052

- Lipsker D. A chilblain epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. A sign of natural resistance to SARS-CoV-2? Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109959. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109959

- Kaya G, Kaya A, Saurat J-H. Clinical and histopathological features and potential pathological mechanisms of skin lesions in COVID-19: review of the literature. Dermatopathology. 2020;7:3-16. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology7010002

- Pavone P, Marino S, Marino L, et al. Chilblains-like lesions and SARS-CoV-2 in children: An overview in therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14502

- Dowd PM, Rustin MH, Lanigan S. Nifedipine in the treatment of chilblains. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:923-924. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6552.923-a

- Rustin MH, Newton JA, Smith NP, et al. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: the results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long-term open trial. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:267-275. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb07792.x

- Almahameed A, Pinto DS. Pernio (chilblains). Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:128-135. doi:10.1007/s11936-008-0014-0

- Chen F, Liu ZS, Zhang FR, et al. First case of severe childhood novel coronavirus pneumonia in China [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:179-182. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.03.003

- Choi S-H, Kim HW, Kang J-M, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 in children. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:125-132. doi:10.3345/cep.2020.00535

- Piccolo V, Neri I, Manunza F, et al. Chilblain-like lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic: should we really worry? Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1026-1027. doi:10.1111/ijd.1499

- Roca-Ginés J, Torres-Navarro I, Sánchez-Arráez J, et al. Assessment of acute acral lesions in a case series of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:992-997. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2340

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Herman A, Peeters C, Verroken A, et al. Evaluation of chilblains as a manifestation of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:998-1003. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2368

- Daneshjou R, Rana J, Dickman M, et al. Pernio-like eruption associated with COVID-19 in skin of color. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:892-897. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.07.009

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0006

- Criado PR, Abdalla BMZ, de Assis IC, et al. Are the cutaneous manifestations during or due to SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 frequent or not? revision of possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:745-756. doi:10.1007/s00011-020-01370-w

- Park A, Iwasaki A. Type I and type III interferons—induction, signaling, evasion, and application to combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:870-878. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.008

- Wollina U, Karadag˘ AS, Rowland-Payne C, et al. Cutaneous signs in COVID-19 patients: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13549. doi:10.1111/dth.13549

- Alonso MN, Mata-Forte T, García-León N, et al. Incidence, characteristics, laboratory findings and outcomes in acro-ischemia in COVID-19 patients. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2020;16:467-478. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S276530

- Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q, et al. D-dimer levels on admission to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1324-1329. doi:10.1111/jth.14859

- Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089-1098. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x

- Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, et al. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153:725-733. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062

- Wichmann D, Sperhake J-P, Lütgehetmann M, et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:268-277. doi:10.7326/M20-2003

- Bastos ML, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2516. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2516

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of

COVID -19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163 - Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Characterization of acute acral skin lesions in nonhospitalized patients: a case series of 132 patients during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E61-E63. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.093

- Deutsch A, Blasiak R, Keyes A, et al. COVID toes: phenomenon or epiphenomenon? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E347-E348. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.037

There has been a rise in the prevalence of perniolike lesions—erythematous to violaceous, edematous papules or nodules on the fingers or toes—during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These lesions are referred to as “COVID toes.” Although several studies have suggested an association with these lesions and COVID-19, and coronavirus particles have been identified in endothelial cells of biopsies of pernio lesions, questions remain on the management, pathophysiology, and implications of these lesions.1 We provide a practical review for primary care clinicians and dermatologists on the current management, recommendations, and remaining questions, with particular attention to the distinctions for children vs adults presenting with pernio lesions.

Hypothetical Case of a Child Presenting With Acral Lesions

A 7-year-old boy presents with acute-onset, violaceous, mildly painful and pruritic macules on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to involve more toes and appear more purpuric. A review of symptoms reveals no fever, cough, fatigue, or viral symptoms. He has been staying at home for the last few weeks with his brother, mother, and father. His father is working in delivery services and is social distancing at work but not at home. His mother is concerned about the lesions, if they could be COVID toes, and if testing is needed for the patient or family. In your assessment and management of this patient, you consider the following questions.

What Is the Relationship Between These Clinical Findings and COVID-19?

Despite negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests reported in cases of chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the possibility that these lesions are an indirect result of environmental factors or behavioral changes during quarantine, the majority of studies favor an association between these chilblains lesions and COVID-19 infection.2,3 Most compellingly, COVID-19 viral particles have been identified by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in the endothelial cells of biopsies of these lesions.1 Additionally, there is evidence for possible associations of other viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19, with chilblains lesions.4,5 In sum, with the lack of any large prospective study, the weight of current evidence suggests that these perniolike skin lesions are not specific markers of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).6

Published studies differ in reporting the coincidence of perniolike lesions with typical COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and anosmia, among others. Some studies have reported that up to 63% of patients with reported perniolike lesions developed typical COVID-19 symptoms, but other studies found that no patients with these lesions developed symptoms.6-11 Studies with younger cohorts tended to report lower prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms, and within cohorts, younger patients tended to have less severe symptoms. For example, 78.8% of patients in a cohort (n=58) with an average age of 14 years did not experience COVID-19–related symptoms.6 Based on these data, it has been hypothesized that patients with chilblainslike lesions may represent a subpopulation who will have a robust interferon response that is protective from more symptomatic and severe COVID-19.12-14

Current evidence suggests that these lesions are most likely to occur between 9 days and 2 months after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.4,9,10 Most cases have been only mildly symptomatic, with an overall favorable prognosis of both lesions and any viral symptoms.8,10 The lesions typically resolve without treatment within a few days of initial onset.15,16

What Should Be the Workup and Management of These Lesions?

Given the currently available information and favorable prognosis, usually no further workup specific to the perniolike lesions is required in the case of an asymptomatic child presenting with acral lesions, and the majority of management will center around patient and parent/guardian education and reassurance. When asked by the patient’s parent, “What does it mean that my child has these lesions?”, clinicians can provide information on the possible association with COVID-19 and the excellent, self-resolving prognosis. An example of honest and reasonable phrasing with current understanding might be, “We are currently not certain if COVID-19 causes these lesions, although there are data to suggest that they are associated. There are a lot of data showing that children with these lesions either do not have any symptoms or have very mild symptoms that resolve without treatment.”

For management, important considerations include how painful the lesions are to the individual patient and how they affect quality of life. If less severe, clinicians can reassure patients and parents/guardians that the lesions will likely self-resolve without treatment. If worsening or symptomatic, clinicians can try typical treatments for chilblains, such as topical steroids, whole-body warming, and nifedipine.17-19 Obtaining a review of symptoms, including COVID-19 symptoms and general viral symptoms, is important given the rare cases of children with severe COVID-19.20,21

The question of COVID-19 testing as related to these lesions remains controversial, and currently there are still differing perspectives on the need for biopsy, PCR for COVID-19, or serologies for COVID-19 in patients presenting with these lesions. Some experts report that additional testing is not needed in the pediatric population because of the high frequency of negative testing reported to date.22,23 However, these children may be silent carriers, and until more is known about their potential to transmit the virus, testing may be considered if resources allow, particularly if the patient has a known exposure.10,12,16,24 The ultimate decision to pursue biopsy or serologic workup for COVID-19 remains up to clinical discretion with consideration of symptoms, severity, and immunocompromised household contacts. If lesions developed after infection, PCR likely will result negative, whereas serologic testing may reveal antibodies.

Hypothetical Case of an Adult Presenting With Acral Lesions and COVID-19 Symptoms

A 50-year-old man presents with acute-onset, violaceous, painful, edematous plaques on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to include the soles. A review of symptoms reveals fever (temperature, 38.4 °C [101 °F]), cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, and severe asthenia. He has had interactions with a coworker who recently tested positive for COVID-19.

How Should You Consider These Lesions in the Context of the Other Symptoms Concerning for COVID-19?

In contrast to the asymptomatic child above, this adult has chilblainslike lesions and viral symptoms. In adults, chilblainslike lesions have been associated with relatively mild COVID-19, and patients with these lesions who are otherwise asymptomatic have largely tested negative for COVID-19 by PCR and serologic antibody testing.11,25,26

True acral ischemia, which is more severe and should be differentiated from chilblains, has been reported in critically ill patients.9 Additionally, studies have found that retiform purpura is the most common cutaneous finding in patients with severe COVID-19.27 For this patient, who has an examination consistent with progressive and severe chilblainslike lesions and suspicion for COVID-19 infection, it is important to observe and monitor these lesions, as clinical progression suggestive of acral ischemia or retiform purpura should be taken seriously and may indicate worsening of the underlying disease. Early intervention with anticoagulation might be considered, though there currently is no evidence of successful treatment.28

What Causes These Lesions in a Patient With COVID-19?

The underlying pathophysiology has been proposed to be a monocytic-macrophage–induced hyperinflammatory systemic state that damages the lungs, as well as the gastrointestinal, renal, and endothelial systems. The activation of the innate immune system triggers a cytokine storm that creates a hypercoagulable state that ultimately can manifest as superficial thromboses, leading to gangrene of the extremities. Additionally, interferon response and resulting hypercytokinemia may cause direct cytopathic damage to the endothelium of arterioles and capillaries, causing the development of papulovesicular lesions that resemble the chilblainslike lesions observed in children.29 In contrast to children, who typically have no or mild COVID-19 symptoms, adults may have a delayed interferon response, which has been proposed to allow for more severe manifestations of infection.12,30

How Should an Adult With Perniolike Lesions Be Managed?

Adults with chilblainslike lesions and no other signs or symptoms of COVID-19 infection do not necessarily need be tested for COVID-19, given the reports demonstrating most patients in this clinical situation will have negative PCRs and serologies for antibodies. However, there have been several reports of adults with acro-ischemic skin findings who also had severe COVID-19, with an observed incidence of 23% in intensive care unit patients with COVID-19.27,28,31,32 If there is suspicion of infection with COVID-19, it is advisable to first obtain workup for COVID-19 and other viruses that can cause acral lesions, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus. Other pertinent laboratory tests may include D-dimer, fibrinogen, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, antithrombin activity, platelet count, neutrophil count, procalcitonin, triglycerides, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and hemoglobin. For patients with evidence of worsening acro-ischemia, regular monitoring of these values up to several times per week can allow for initiation of vascular intervention, including angiontensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, or antiplatelet drugs.32 The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies also has been associated with critically ill patients who develop digit ischemia as part of the sequelae of COVID-19 infection and therefore may act as an important marker for the potential to develop disseminated intravascular coagulation in this patient.33 Even if COVID-19 infection is not suspected, a thorough review of systems is important to look for an underlying connective tissue disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, which is associated with pernio. Associated symptoms may warrant workup with antinuclear antibodies and other appropriate autoimmune serologies.

If there is any doubt of the diagnosis, the patient is experiencing symptoms from the lesion, or the patient is experiencing other viral symptoms, it is appropriate to biopsy immediately to confirm the diagnosis. Prior studies have identified fibrin clots, angiocentric and eccrinotropic lymphocytic infiltrates, lymphocytic vasculopathy, and papillary dermal edema as the most common features in chilblainslike lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic.9

For COVID-19 testing, many studies have revealed adult patients with an acute hypercoagulable state testing positive by SARS-CoV-2 PCR. These same patients also experienced thromboembolic events shortly after testing positive for COVID-19, which suggests that patients with elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen likely will have a viral load that is sufficient to test positive for COVID-19.32,34-36 It is appropriate to test all patients with suspected COVID-19, especially adults who are more likely to experience adverse complications secondary to infection.

This patient experiencing COVID-19 symptoms with signs of acral ischemia is likely to test positive by PCR, and additional testing for serologic antibodies is unlikely to be clinically meaningful in this patient’s state. Furthermore, there is little evidence that serology is reliable because of the markedly high levels of both false-negative and false-positive results when using the available antibody testing kits.37 The latter evidence makes serology testing of little value for the general population, but particularly for patients with acute COVID-19.

Conclusion and Outstanding Questions

There is evidence suggesting an association between chilblainslike lesions and COVID-19.11,22,38,39 Children presenting with these lesions have an excellent prognosis and only need a workup or treatment if there are other symptoms, as the lesions self-resolve in the majority of reported cases.7-9 Adults presenting with these lesions and without symptoms likewise are unlikely to test positive for COVID-19, and the lesions typically resolve spontaneously or with first-line treatment. However, adults presenting with these lesions and COVID-19 symptoms should raise clinical concern for evolving skin manifestations of acro-ischemia. If the diagnosis is uncertain or systemic symptoms are concerning, biopsy, COVID-19 PCR, and other appropriate laboratory workup should be obtained.

There remains controversy and uncertainty over the relationship between these skin findings and SARS-CoV-2 infection, with clinical evidence to support both a direct relationship representing convalescent-phase cutaneous reaction as well as an indirect epiphenomenon. If there was a direct relationship, we would have expected to see a rise in the incidence of acral lesions proportionate to the rising caseload of COVID-19 after the reopening of many states in the summer of 2020. Similarly, because young adults represent the largest demographic of increasing cases and as some schools have remained open for in-person instruction during the current academic year, we also would have expected the incidence of chilblains-like lesions presenting to dermatologists and pediatricians to increase alongside these cases. Continued evaluation of emerging literature and ongoing efforts to understand the cause of this observed phenomenon will hopefully help us arrive at a future understanding of the pathophysiology of this puzzling skin manifestation.40

There has been a rise in the prevalence of perniolike lesions—erythematous to violaceous, edematous papules or nodules on the fingers or toes—during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These lesions are referred to as “COVID toes.” Although several studies have suggested an association with these lesions and COVID-19, and coronavirus particles have been identified in endothelial cells of biopsies of pernio lesions, questions remain on the management, pathophysiology, and implications of these lesions.1 We provide a practical review for primary care clinicians and dermatologists on the current management, recommendations, and remaining questions, with particular attention to the distinctions for children vs adults presenting with pernio lesions.

Hypothetical Case of a Child Presenting With Acral Lesions

A 7-year-old boy presents with acute-onset, violaceous, mildly painful and pruritic macules on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to involve more toes and appear more purpuric. A review of symptoms reveals no fever, cough, fatigue, or viral symptoms. He has been staying at home for the last few weeks with his brother, mother, and father. His father is working in delivery services and is social distancing at work but not at home. His mother is concerned about the lesions, if they could be COVID toes, and if testing is needed for the patient or family. In your assessment and management of this patient, you consider the following questions.

What Is the Relationship Between These Clinical Findings and COVID-19?

Despite negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests reported in cases of chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the possibility that these lesions are an indirect result of environmental factors or behavioral changes during quarantine, the majority of studies favor an association between these chilblains lesions and COVID-19 infection.2,3 Most compellingly, COVID-19 viral particles have been identified by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in the endothelial cells of biopsies of these lesions.1 Additionally, there is evidence for possible associations of other viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19, with chilblains lesions.4,5 In sum, with the lack of any large prospective study, the weight of current evidence suggests that these perniolike skin lesions are not specific markers of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).6

Published studies differ in reporting the coincidence of perniolike lesions with typical COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and anosmia, among others. Some studies have reported that up to 63% of patients with reported perniolike lesions developed typical COVID-19 symptoms, but other studies found that no patients with these lesions developed symptoms.6-11 Studies with younger cohorts tended to report lower prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms, and within cohorts, younger patients tended to have less severe symptoms. For example, 78.8% of patients in a cohort (n=58) with an average age of 14 years did not experience COVID-19–related symptoms.6 Based on these data, it has been hypothesized that patients with chilblainslike lesions may represent a subpopulation who will have a robust interferon response that is protective from more symptomatic and severe COVID-19.12-14

Current evidence suggests that these lesions are most likely to occur between 9 days and 2 months after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.4,9,10 Most cases have been only mildly symptomatic, with an overall favorable prognosis of both lesions and any viral symptoms.8,10 The lesions typically resolve without treatment within a few days of initial onset.15,16

What Should Be the Workup and Management of These Lesions?

Given the currently available information and favorable prognosis, usually no further workup specific to the perniolike lesions is required in the case of an asymptomatic child presenting with acral lesions, and the majority of management will center around patient and parent/guardian education and reassurance. When asked by the patient’s parent, “What does it mean that my child has these lesions?”, clinicians can provide information on the possible association with COVID-19 and the excellent, self-resolving prognosis. An example of honest and reasonable phrasing with current understanding might be, “We are currently not certain if COVID-19 causes these lesions, although there are data to suggest that they are associated. There are a lot of data showing that children with these lesions either do not have any symptoms or have very mild symptoms that resolve without treatment.”

For management, important considerations include how painful the lesions are to the individual patient and how they affect quality of life. If less severe, clinicians can reassure patients and parents/guardians that the lesions will likely self-resolve without treatment. If worsening or symptomatic, clinicians can try typical treatments for chilblains, such as topical steroids, whole-body warming, and nifedipine.17-19 Obtaining a review of symptoms, including COVID-19 symptoms and general viral symptoms, is important given the rare cases of children with severe COVID-19.20,21

The question of COVID-19 testing as related to these lesions remains controversial, and currently there are still differing perspectives on the need for biopsy, PCR for COVID-19, or serologies for COVID-19 in patients presenting with these lesions. Some experts report that additional testing is not needed in the pediatric population because of the high frequency of negative testing reported to date.22,23 However, these children may be silent carriers, and until more is known about their potential to transmit the virus, testing may be considered if resources allow, particularly if the patient has a known exposure.10,12,16,24 The ultimate decision to pursue biopsy or serologic workup for COVID-19 remains up to clinical discretion with consideration of symptoms, severity, and immunocompromised household contacts. If lesions developed after infection, PCR likely will result negative, whereas serologic testing may reveal antibodies.

Hypothetical Case of an Adult Presenting With Acral Lesions and COVID-19 Symptoms

A 50-year-old man presents with acute-onset, violaceous, painful, edematous plaques on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to include the soles. A review of symptoms reveals fever (temperature, 38.4 °C [101 °F]), cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, and severe asthenia. He has had interactions with a coworker who recently tested positive for COVID-19.

How Should You Consider These Lesions in the Context of the Other Symptoms Concerning for COVID-19?

In contrast to the asymptomatic child above, this adult has chilblainslike lesions and viral symptoms. In adults, chilblainslike lesions have been associated with relatively mild COVID-19, and patients with these lesions who are otherwise asymptomatic have largely tested negative for COVID-19 by PCR and serologic antibody testing.11,25,26

True acral ischemia, which is more severe and should be differentiated from chilblains, has been reported in critically ill patients.9 Additionally, studies have found that retiform purpura is the most common cutaneous finding in patients with severe COVID-19.27 For this patient, who has an examination consistent with progressive and severe chilblainslike lesions and suspicion for COVID-19 infection, it is important to observe and monitor these lesions, as clinical progression suggestive of acral ischemia or retiform purpura should be taken seriously and may indicate worsening of the underlying disease. Early intervention with anticoagulation might be considered, though there currently is no evidence of successful treatment.28

What Causes These Lesions in a Patient With COVID-19?