User login

Use of Fecal Immunochemical Testing in Acute Patient Care in a Safety Net Hospital System

From Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Drs. Spezia-Lindner, Montealegre, Muldrew, and Suarez) and Harris Health System, Houston, TX (Shanna L. Harris, Maria Daheri, and Drs. Muldrew and Suarez).

Abstract

Objective: To characterize and analyze the prevalence, indications for, and outcomes of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in acute patient care within a safety net health care system’s emergency departments (EDs) and inpatient settings.

Design: Retrospective cohort study derived from administrative data.

Setting: A large, urban, safety net health care delivery system in Texas. The data gathered were from the health care system’s 2 primary hospitals and their associated EDs. This health care system utilizes FIT exclusively for fecal occult blood testing.

Participants: Adults ≥18 years who underwent FIT in the ED or inpatient setting between August 2016 and March 2017. Chart review abstractions were performed on a sample (n = 382) from the larger subset.

Measurements: Primary data points included total FITs performed in acute patient care during the study period, basic demographic data, FIT indications, FIT result, receipt of invasive diagnostic follow-up, and result of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Multivariable log-binomial regression was used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) to assess the association between FIT result and receipt of diagnostic follow-up. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result.

Results: During the 8-month study period, 2718 FITs were performed in the ED and inpatient setting, comprising 5.7% of system-wide FITs. Of the 382 patients included in the chart review who underwent acute care FIT, a majority had their test performed in the ED (304, 79.6%), 133 of which were positive (34.8%). The most common indication for FIT was evidence of overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (207, 54.2%), followed by anemia (84, 22.0%). While a positive FIT result was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72; P < 0.001), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00; P = 0.003). Of patients who underwent FIT and received diagnostic follow-up (n = 110), 48.2% were FIT negative. These patients were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86). Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 (1.0%) were subsequently diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC). Of those 4 patients, 1 (25%) was FIT positive.

Conclusion: FIT is being utilized in acute patient care outside of its established indication for CRC screening in asymptomatic, average-risk adults. Our study demonstrates that FIT is not useful in acute patient care.

Keywords: FOBT; FIT; fecal immunochemical testing; inpatient.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States. It is estimated that in 2020, 147,950 individuals will be diagnosed with invasive CRC and 53,200 will die from it.1 While the overall incidence has been declining for decades, it is rising in young adults.2–4 Screening using direct visualization procedures (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy) and stool-based tests has been demonstrated to improve detection of precancerous and early cancerous lesions, thereby reducing CRC mortality.5 However, screening rates in the United States are suboptimal, with only 68.8% of adults aged 50 to 75 years screened according to guidelines in 2018.6Stool-based testing is a well-established and validated screening measure for CRC in asymptomatic individuals at average risk. Its widespread use in this population has been shown to cost-effectively screen for CRC among adults 50 years of age and older.5,7 Presently, the 2 most commonly used stool-based assays in the US health care system are guaiac-based tests (guaiac fecal occult blood test [gFOBT], Hemoccult) and

Despite the exclusive validation of FOBTs for use in CRC screening, studies have demonstrated that they are commonly used for a multitude of additional indications in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings, most aimed at detecting or confirming GI blood loss. This may lead to inappropriate patient management, including the receipt of unnecessary follow-up procedures, which can incur significant costs to the patient and the health system.13-19 These costs may be particularly burdensome in safety net health systems (ie, those that offer access to care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay), which serve a large proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals in the United States.20,21 To our knowledge, no published study to date has specifically investigated the role of FIT in acute patient management.

This study characterizes the use of FIT in acute patient care within a large, urban, safety net health care system. Through a retrospective review of administrative data and patient charts, we evaluated FIT use prevalence, indications, and patient outcomes in the ED and inpatient settings.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in a large, urban, county-based integrated delivery system in Houston, Texas, that provides health care services to one of the largest uninsured and underinsured populations in the country.22 The health system includes 2 main hospitals and more than 20 ambulatory care clinics. Within its ambulatory care clinics, the health system implements a population-based screening strategy using stool-based testing. All adults aged 50 years or older who are due for FIT are identified through the health-maintenance module of the electronic medical record (EMR) and offered a take-home FIT. The health system utilizes FIT exclusively (OC-Light S FIT, Polymedco, Cortlandt Manor, NY); no guaiac-based assays are available.

Design and Data Collection

We began by using administrative records to determine the proportion of FITs conducted health system-wide that were ordered and completed in the acute care setting over the study period (August 2016-March 2017). Specifically, we used aggregate quality metric reports, which quantify the number of FITs conducted at each health system clinic and hospital each month, to calculate the proportion of FITs done in the ED and inpatient hospital setting.

We then conducted a retrospective cohort study of 382 adult patients who received FIT in the EDs and inpatient wards in both of the health system’s hospitals over the study period. All data were collected by retrospective chart review in Epic (Madison, WI) EMRs. Sampling was performed by selecting the medical record numbers corresponding to the first 50 completed FITs chronologically each month over the 8-month period, with a total of 400 charts reviewed.

Data collected included basic patient demographics, location of FIT ordering (ED vs inpatient), primary service ordering FIT, FIT indication, FIT result, and receipt and results of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Demographics collected included age, biological sex, race (self-selected), and insurance coverage.

FIT indication was determined based on resident or attending physician notes. The history of present illness, physical exam, and assessment and plan section of notes were reviewed by the lead author for a specific statement of indication for FIT or for evidence of clinical presentation for which FIT could reasonably be ordered. Indications were iteratively reviewed and collapsed into 6 different categories: anemia, iron deficiency with or without anemia, overt GIB, suspected GIB/miscellaneous, non-bloody diarrhea, and no indication identified. Overt GIB was defined as reported or witnessed hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, bright red blood per rectum, or melena irrespective of time frame (current or remote) or chronicity (acute, subacute, or chronic). In cases where signs of overt bleed were not witnessed by medical professionals, determination of conditions such as melena or coffee-ground emesis were made based on health care providers’ assessment of patient history as documented in his or her notes. Suspected GIB/miscellaneous was defined with the following parameters: any new drop in hemoglobin, abdominal pain, anorectal pain, non-bloody vomiting, hemoptysis, isolated rising blood urea nitrogen, or patient noticing blood on self, clothing, or in the commode without an identified source. Patients who were anemic and found to have iron deficiency on recent lab studies (within 6 months) were reflexively categorized into iron deficiency with or without anemia as opposed to the “anemia” category, which was comprised of any anemia without recent iron studies or non-iron deficient anemia. FIT result was determined by test result entry in Epic, with results either reading positive or negative.

Diagnostic follow-up, for our purposes, was defined as receipt of an invasive procedure or surgery, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, diagnostic and/or therapeutic abdominal surgical intervention, or any combination of these. Results of diagnostic follow-up were coded as normal or abnormal. A normal result was determined if all procedures performed were listed as normal or as “no pathological findings” on the operative or endoscopic report. Any reported pathologic findings on the operative/endoscopic report were coded as abnormal.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions were used to describe demographic characteristics of patients who received a FIT in acute hospital settings. Bivariable tables and Chi-square tests were used to compare indications and outcomes for FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients. The association between receipt of an invasive diagnostic follow-up (outcome) and the results of an inpatient FIT (predictor) was assessed using multivariable log-binomial regression to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Log-binomial regression was used over logistic regression given that adjusted odds ratios generated by logistic regression often overestimate the association between the risk factor and the outcome when the outcome is common,23 as in the case of diagnostic follow-up. The model was adjusted for variables selected a priori, specifically, age, gender, and FIT indication. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result (negative vs positive).

Results

During the 8-month study period, there were 2718 FITs ordered and completed in the acute care setting, compared to 44,662 FITs ordered and completed in the outpatient setting (5.7% performed during acute care).

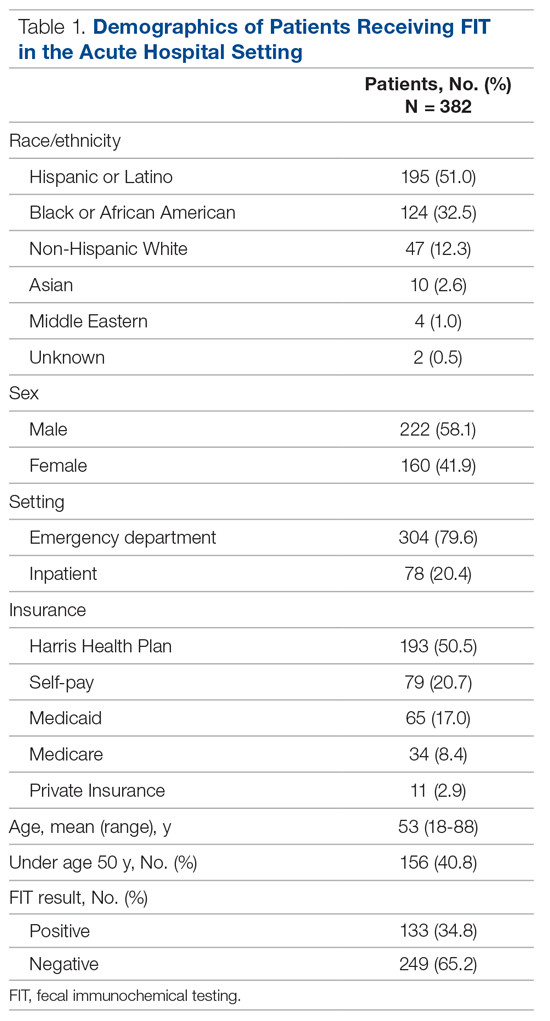

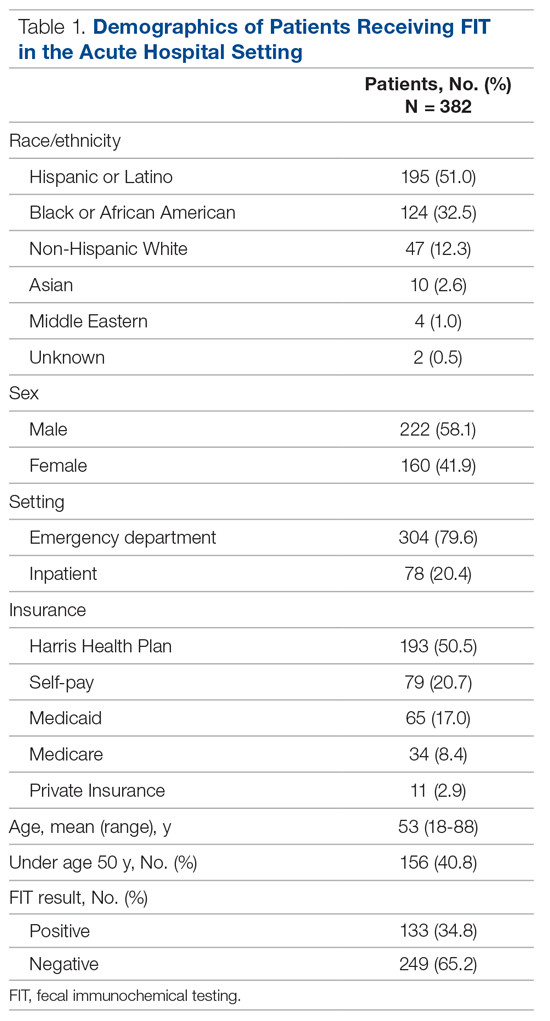

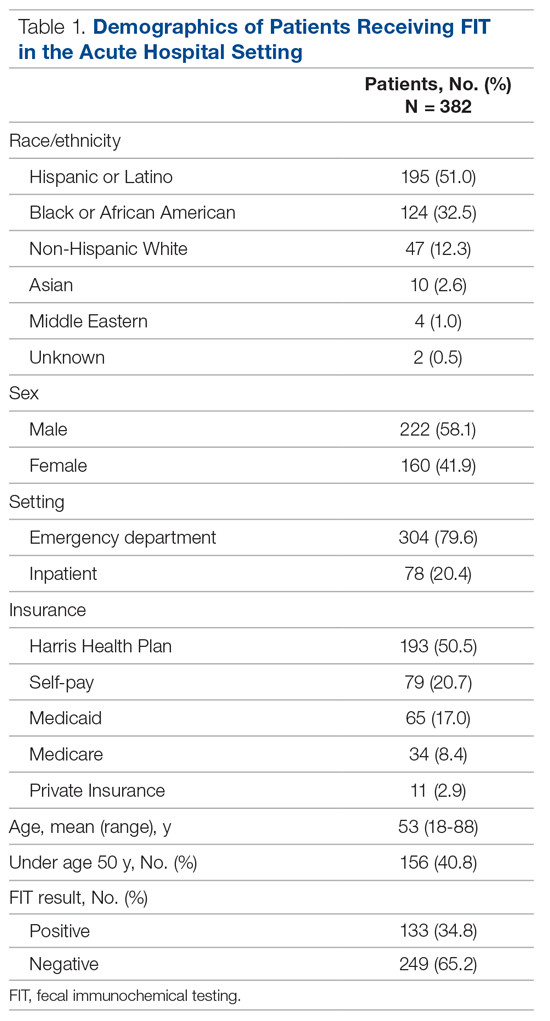

Among the 400 charts reviewed, 7 were excluded from the analysis because they were duplicates from the same patient, and 11 were excluded due to insufficient information in the patient’s medical record, resulting in 382 patients included in the analysis. Patient demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Patients were predominantly Hispanic/Latino or Black/African American (51.0% and 32.5%, respectively), a majority had insurance through the county health system (50.5%), and most were male (58.1%). The average age of those receiving FIT was 52 years (standard deviation, 14.8 years), with 40.8% being under the age of 50. For a majority of patients, FIT was ordered in the ED by emergency medicine providers (79.8%). The remaining FITs were ordered by providers in 12 different inpatient departments. Of the FITs ordered, 35.1% were positive.

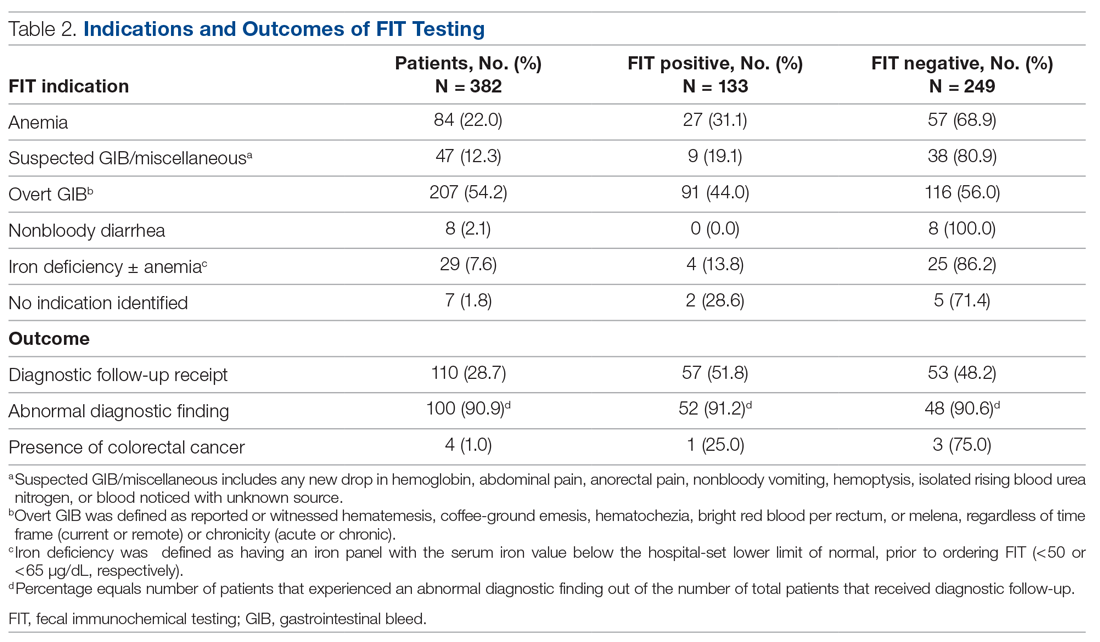

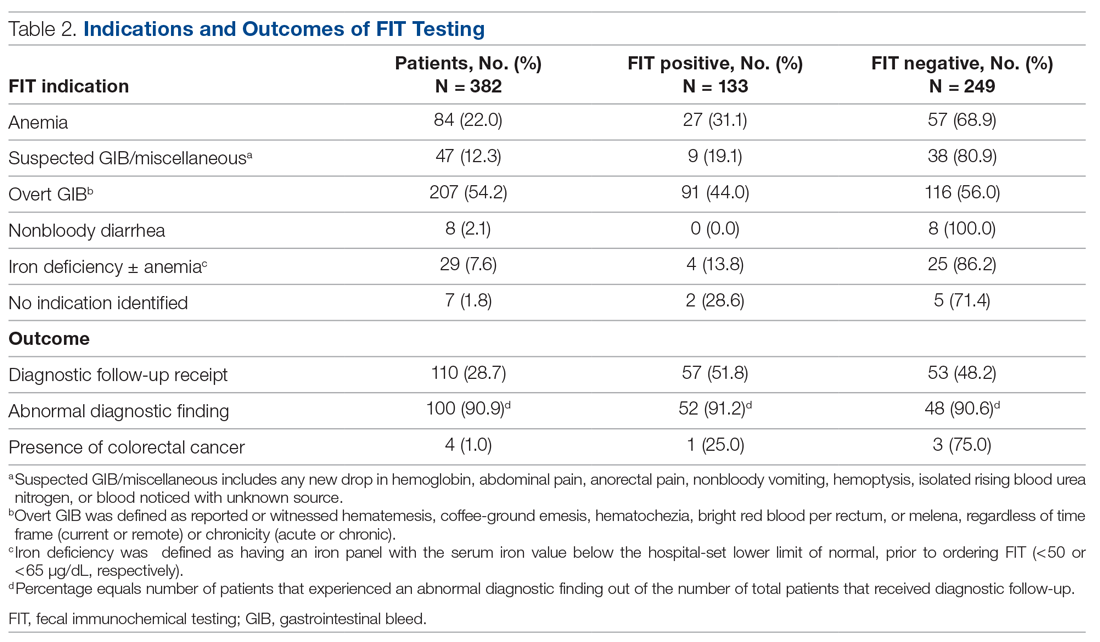

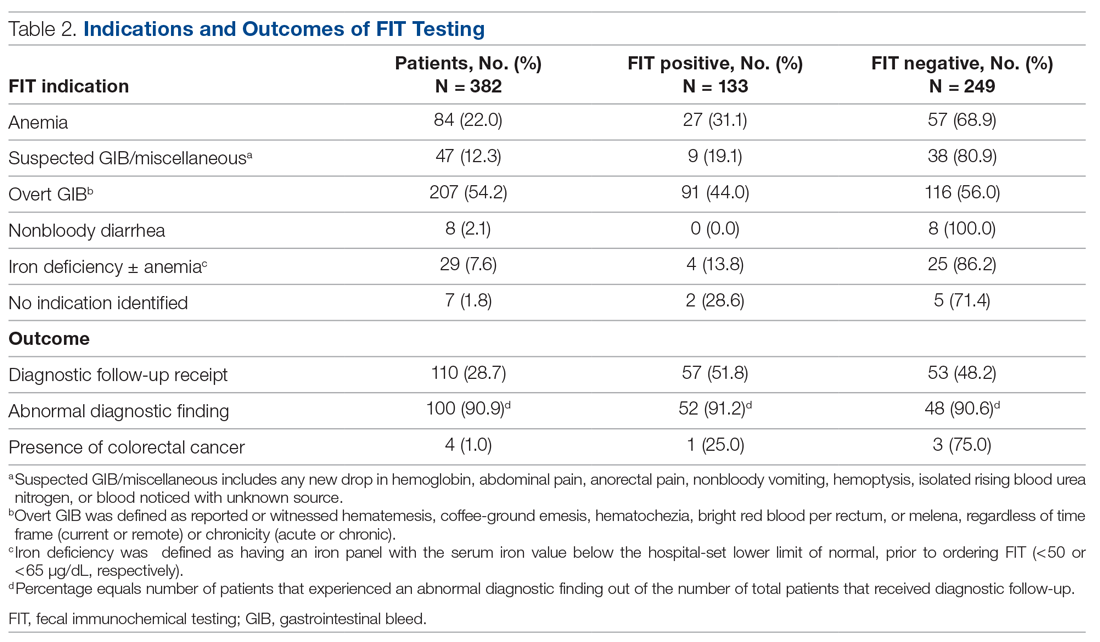

Indications for ordering FIT are listed in Table 2. The largest proportion of FITs were ordered for overt signs of GIB (54.2%), followed by anemia (22.0%), suspected GIB/miscellaneous reasons (12.3%), iron deficiency with or without anemia (7.6%), and non-bloody diarrhea (2.1%). In 1.8% of cases, no indication for FIT was found in the EMR. No FITs were ordered for the indication of CRC detection. Of these indication categories, overt GIB yielded the highest percentage of FIT positive results (44.0%), and non-bloody diarrhea yielded the lowest (0%).

A total of 110 patients (28.7%) underwent FIT and received invasive diagnostic follow-up. Of these 110 patients, 57 (51.8%) underwent EGD (2 of whom had further surgical intervention), 21 (19.1%) underwent colonoscopy (1 of whom had further surgical intervention), 25 (22.7%) underwent dual EGD and colonoscopy, 1 (0.9%) underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, and 6 (5.5%) directly underwent abdominal surgical intervention. There was a significantly higher rate of diagnostic follow-up for FIT-positive vs FIT-negative patients (42.9% vs 21.3%; P < 0.001). However, of the 110 patients who underwent subsequent diagnostic follow-up, 48.2% were FIT negative. FIT-negative patients who received diagnostic follow-up were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86).

Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 were diagnosed with CRC through diagnostic follow-up (1.0%). Of those 4 patients, 1 was FIT positive.

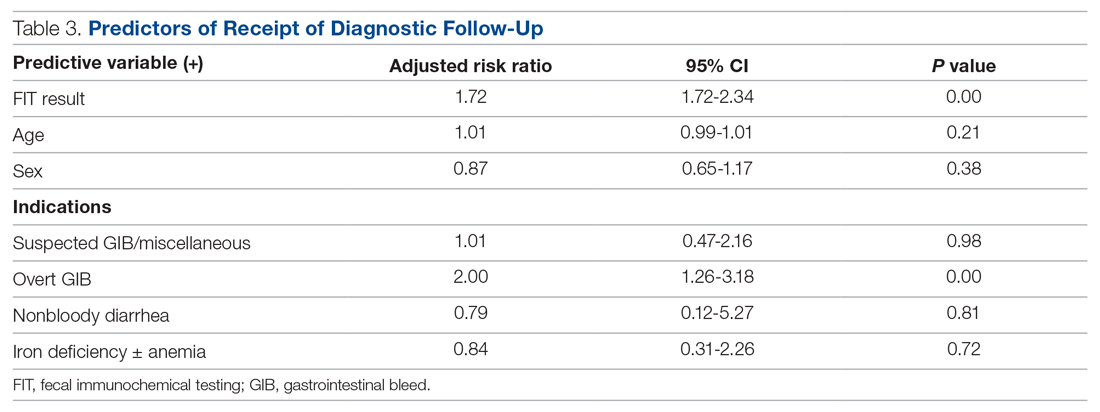

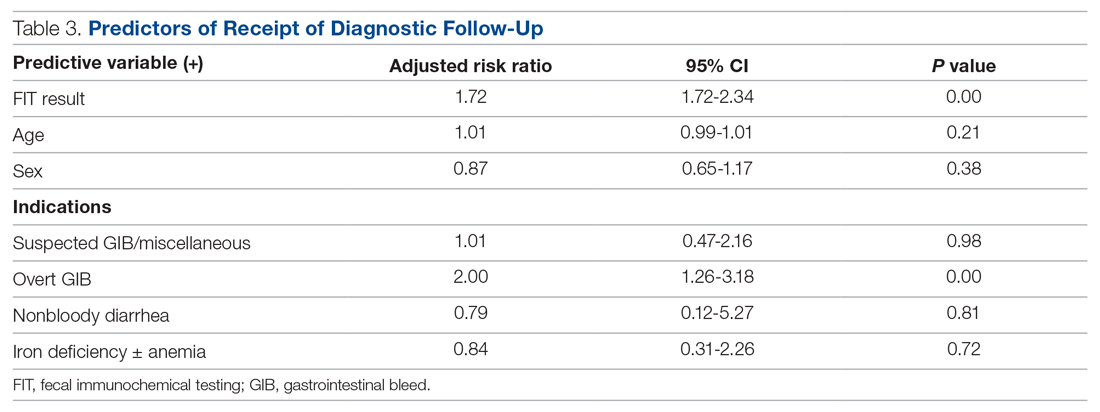

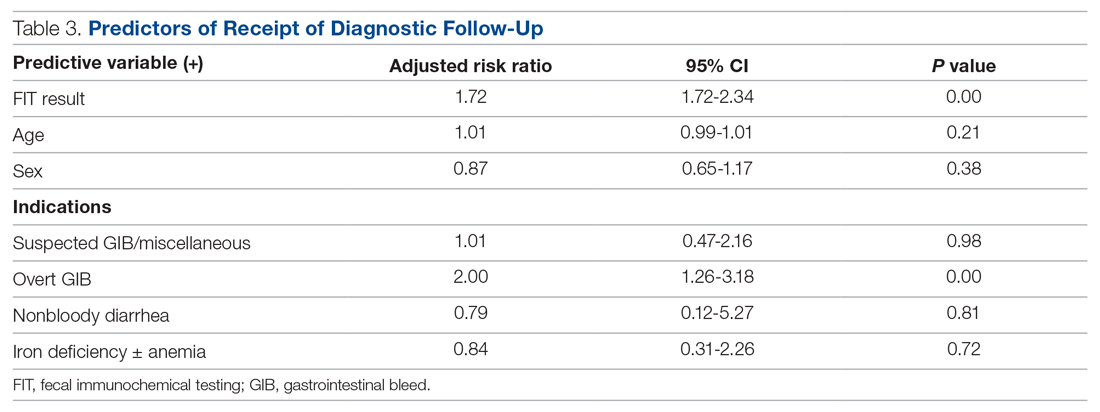

The results of the multivariable analyses to evaluate predictors of diagnostic colonoscopy are described in Table 3. Variables in the final model were FITresult, age, and FIT indication. After adjusting for other variables in the model, receipt of diagnostic follow-up was significantly associated with having a positive FIT (adjusted RR, 1.72; P < 0.001) and an overt GIB as an indication (adjusted RR, 2.00; P < 0.01).

Discussion

During the time frame of our study, 5.7% of all FITs ordered within our health system were ordered in the acute patient care setting at our hospitals. The most common indication was overt GIB, which was the indication for 54.2% of patients. Of note, none of the FITs ordered in the acute patient care setting were ordered for CRC screening. These findings support the evidence in the literature that stool-based screening tests, including FIT, are commonly used in US health care systems for diagnostic purposes and risk stratification in acute patient care to detect GIBs.13-18

Our data suggest that FIT was not a clinically useful test in determining a patient’s need for diagnostic follow-up. While having a positive FIT was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00). This salient finding is evidence that a thorough clinical history and physical exam may more strongly predict whether a patient will undergo endoscopy or other follow-up than a FIT result. These findings support other studies in the literature that have called into question the utility of FOBTs in these acute settings.13-19 Under such circumstances, FOBTs have been shown to rarely influence patient management and thus represent an unnecessary expense.13–17 Additionally, in some cases, FOBT use in these settings may negatively affect patient outcomes. Such adverse effects include delaying treatment until results are returned or obfuscating indicated management with the results (eg, a patient with indications for colonoscopy not being referred due to a negative FOBT).13,14,17

We found that, for patients who subsequently went on to have diagnostic follow-up (most commonly endoscopy), there was no difference in the likelihood of FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients to have an abnormality discovered (91.2% vs 90.6%; P = 0.86). This analysis demonstrates no post-hoc support for FIT positivity as a predictor of presence of pathology in patients who were discriminately selected for diagnostic follow-up on clinical grounds by gastroenterologists and surgeons. It does, however, further support that clinical judgment about the need for diagnostic follow-up—irrespective of FIT result—has a very high yield for discovery of pathology in the acute setting.

There are multiple reasons why FOBTs, and specifically FIT, contribute little in management decisions for patients with suspected GI blood loss. Use of FIT raises concern for both false-negatives and false-positives when used outside of its indication. Regarding false- negatives, FIT is an unreliable test for detection of blood loss from the upper GI tract. As FITs utilize antibodies to detect the presence of globin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, it is expected that FIT would fail to detect many cases of upper GI bleeding, as globin is broken down in the upper GI tract.24 This fact is part of what has made FIT a more effective CRC screening test than its guaiac-based counterparts—it has greater specificity for lower GI tract blood loss compared to tests relying on detection of heme.8 While guaiac-based assays like Hemoccult have also been shown to be poor tests in acute patient care, they may more frequently, though still unreliably, detect blood of upper GI origin. We believe that part of the ongoing use of FIT in patients with a suspected upper GIB may be from lack of understanding among providers on the mechanistic difference between gFOBTs and FITs, even though gFOBTs also yield highly unreliable results.

FIT does not have the same risk of false-positive results that guaiac-based tests have, which can yield positive results with extra-intestinal blood ingestion, aspirin, or alcohol use; insignificant GI bleeding; and consumption of peroxidase-containing foods.13,17,25 However, from a clinical standpoint, there are several scenarios of insignificant bleeding that would yield a positive FIT result, such as hemorrhoids, which are common in the US population.26,27 Additionally, in the ED, where most FITs were performed in our study, it is possible that samples for FITs are being obtained via digital rectal exam (DRE) given patients’ acuity of medical conditions and time constraints. However, FIT has been validated when using a formed stool sample. Obtaining FIT via DRE may lead to microtrauma to the rectum, which could hypothetically yield a positive FIT.

Strengths of this study include its use of in-depth chart data on a large number of FIT-positive patients, which allowed us to discern indications, outcomes, and other clinical data that may have influenced clinical decision-making. Additionally, whereas other studies that address FOBT use in acute patient care have focused on guaiac-based assays, our findings regarding the lack of utility of FIT are novel and have particular relevance as FITs continue to grow in popularity. Nonetheless, there are certain limitations future research should seek to address. In this study, the diagnostic follow-up result was coded by presence or absence of pathologic findings but did not qualify findings by severity or attempt to determine whether the pathology noted on diagnostic follow-up was the definitive source of the suspected GI bleed. These variables could help determine whether there was a difference in severity of bleeding between FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients and could potentially be studied with a prospective research design. Our own study was not designed to address the question of whether FIT result informs patient management decisions. To answer this directly, interviews would have to be conducted with those making the follow-up decision (ie, endoscopists and surgeons). Additionally, this study was not adequately powered to make determinations on the efficacy of FIT in the acute care setting for detection of CRC. As mentioned, only 1 of the 4 patients (25%) who went on to be diagnosed with CRC on follow-up was initially FIT-positive. This would require further investigation.

Conclusion

FIT is being utilized for diagnostic purposes in the acute care of symptomatic patients, which is a misuse of an established screening test for CRC. While our study was not designed to answer whether and how often a FIT result informs subsequent patient management, our results indicate that FIT is an ineffective diagnostic and risk-stratification tool when used in the acute care setting. Our findings add to existing evidence that indicates FOBTs should not be used in acute patient care.

Taken as a whole, the results of our study add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating no role for FOBTs, and specifically FIT, in acute patient care. In light of this evidence, some health care systems have already demonstrated success with system-wide disinvestment from the test in acute patient care settings, with one group publishing about their disinvestment process.28 After completion of our study, our preliminary data were presented to leadership from the internal medicine, emergency medicine, and laboratory divisions within our health care delivery system to galvanize complete disinvestment of FIT from acute care at our hospitals, a policy that was put into effect in July 2019.

Corresponding author: Nathaniel J. Spezia-Lindner, MD, Baylor College of Medicine, 7200 Cambridge St, BCM 903, Ste A10.197, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, CPRIT (PP170094, PDs: ML Jibaja-Weiss and JR Montealegre).

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. 10.1CA Cancer 10.1J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30.

2. Howlader NN, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute; 2017:1-2.

3. Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. 10.1J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322.

4. Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. 10.25JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):17-22.

5. Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 10.25JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576-2594.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. October 22, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

7. Hewitson P, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer using the fecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. 10.25Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(1):CD001216.

8. Bujanda L, Lanas Á, Quintero E, et al. Effect of aspirin and antiplatelet drugs on the outcome of the fecal immunochemical test. 10.25Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(7):683-689.

9. Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. 10.25J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462-1470.

10. Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Lepage C, et al. Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests are superior to guaiac-based tests for the detection of colorectal neoplasms. 10.25Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(15):2254-2258.

11. Hol L, Wilschut JA, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing at different cut-off levels. 10.25Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1103-1110.

12. Levi Z, Birkenfeld S, Vilkin A, et al. A higher detection rate for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyp for screening with immunochemical fecal occult blood test than guaiac fecal occult blood test, despite lower compliance rate. A prospective, controlled, feasibility study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(10):2415-2424.

13. Friedman A, Chan A, Chin LC, et al. Use and abuse of faecal occult blood tests in an acute hospital inpatient setting. Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):107-111.

14. Narula N, Ulic D, Al-Dabbagh R, et al. Fecal occult blood testing as a diagnostic test in symptomatic patients is not useful: a retrospective chart review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(8):421-426.

15. Ip S, Sokoro AA, Kaita L, et al. Use of fecal occult blood testing in hospitalized patients: results of an audit. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(9):489-494.

16. Mosadeghi S, Ren H, Catungal J, et al. Utilization of fecal occult blood test in the acute hospital setting and its impact on clinical management and outcomes. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62(2):91-95.

17. van Rijn AF, Stroobants AK, Deutekom M, et al. Inappropriate use of the faecal occult blood test in a university hospital in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1266-1269.

18. Sharma VK, Komanduri S, Nayyar S, et al. An audit of the utility of in-patient fecal occult blood testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):1256-1260.

19. Chiang TH, Lee YC, Tu CH, et al. Performance of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test in predicting lesions in the lower gastrointestinal tract. CMAJ. 2011;183(13):1474-1481.

20. Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM. Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1790-1796.

21. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Halm EA. National use of safety net clinics for primary care among adults with non-Medicaid insurance in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151610.

22. United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Selected Economic Characteristics. 2019. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03%20Texas&g=0400000US48&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03&hidePreview=true

23. McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940-943.

24. Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):699-718.

25. Macrae FA, St John DJ. Relationship between patterns of bleeding and Hemoccult sensitivity in patients with colorectal cancers or adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1982;82(5 pt 1):891-898.

26. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380-386.

27. Fleming JL, Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, et al. Influence of aspirin and ethanol on fecal blood levels as determined by using the HemoQuant assay. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62(3):159-163.

28. Gupta A, Tang Z, Agrawal D. Eliminating in-hospital fecal occult blood testing: our experience with disinvestment. Am J Med. 2018;131(7):760-763.

From Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Drs. Spezia-Lindner, Montealegre, Muldrew, and Suarez) and Harris Health System, Houston, TX (Shanna L. Harris, Maria Daheri, and Drs. Muldrew and Suarez).

Abstract

Objective: To characterize and analyze the prevalence, indications for, and outcomes of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in acute patient care within a safety net health care system’s emergency departments (EDs) and inpatient settings.

Design: Retrospective cohort study derived from administrative data.

Setting: A large, urban, safety net health care delivery system in Texas. The data gathered were from the health care system’s 2 primary hospitals and their associated EDs. This health care system utilizes FIT exclusively for fecal occult blood testing.

Participants: Adults ≥18 years who underwent FIT in the ED or inpatient setting between August 2016 and March 2017. Chart review abstractions were performed on a sample (n = 382) from the larger subset.

Measurements: Primary data points included total FITs performed in acute patient care during the study period, basic demographic data, FIT indications, FIT result, receipt of invasive diagnostic follow-up, and result of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Multivariable log-binomial regression was used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) to assess the association between FIT result and receipt of diagnostic follow-up. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result.

Results: During the 8-month study period, 2718 FITs were performed in the ED and inpatient setting, comprising 5.7% of system-wide FITs. Of the 382 patients included in the chart review who underwent acute care FIT, a majority had their test performed in the ED (304, 79.6%), 133 of which were positive (34.8%). The most common indication for FIT was evidence of overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (207, 54.2%), followed by anemia (84, 22.0%). While a positive FIT result was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72; P < 0.001), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00; P = 0.003). Of patients who underwent FIT and received diagnostic follow-up (n = 110), 48.2% were FIT negative. These patients were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86). Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 (1.0%) were subsequently diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC). Of those 4 patients, 1 (25%) was FIT positive.

Conclusion: FIT is being utilized in acute patient care outside of its established indication for CRC screening in asymptomatic, average-risk adults. Our study demonstrates that FIT is not useful in acute patient care.

Keywords: FOBT; FIT; fecal immunochemical testing; inpatient.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States. It is estimated that in 2020, 147,950 individuals will be diagnosed with invasive CRC and 53,200 will die from it.1 While the overall incidence has been declining for decades, it is rising in young adults.2–4 Screening using direct visualization procedures (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy) and stool-based tests has been demonstrated to improve detection of precancerous and early cancerous lesions, thereby reducing CRC mortality.5 However, screening rates in the United States are suboptimal, with only 68.8% of adults aged 50 to 75 years screened according to guidelines in 2018.6Stool-based testing is a well-established and validated screening measure for CRC in asymptomatic individuals at average risk. Its widespread use in this population has been shown to cost-effectively screen for CRC among adults 50 years of age and older.5,7 Presently, the 2 most commonly used stool-based assays in the US health care system are guaiac-based tests (guaiac fecal occult blood test [gFOBT], Hemoccult) and

Despite the exclusive validation of FOBTs for use in CRC screening, studies have demonstrated that they are commonly used for a multitude of additional indications in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings, most aimed at detecting or confirming GI blood loss. This may lead to inappropriate patient management, including the receipt of unnecessary follow-up procedures, which can incur significant costs to the patient and the health system.13-19 These costs may be particularly burdensome in safety net health systems (ie, those that offer access to care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay), which serve a large proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals in the United States.20,21 To our knowledge, no published study to date has specifically investigated the role of FIT in acute patient management.

This study characterizes the use of FIT in acute patient care within a large, urban, safety net health care system. Through a retrospective review of administrative data and patient charts, we evaluated FIT use prevalence, indications, and patient outcomes in the ED and inpatient settings.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in a large, urban, county-based integrated delivery system in Houston, Texas, that provides health care services to one of the largest uninsured and underinsured populations in the country.22 The health system includes 2 main hospitals and more than 20 ambulatory care clinics. Within its ambulatory care clinics, the health system implements a population-based screening strategy using stool-based testing. All adults aged 50 years or older who are due for FIT are identified through the health-maintenance module of the electronic medical record (EMR) and offered a take-home FIT. The health system utilizes FIT exclusively (OC-Light S FIT, Polymedco, Cortlandt Manor, NY); no guaiac-based assays are available.

Design and Data Collection

We began by using administrative records to determine the proportion of FITs conducted health system-wide that were ordered and completed in the acute care setting over the study period (August 2016-March 2017). Specifically, we used aggregate quality metric reports, which quantify the number of FITs conducted at each health system clinic and hospital each month, to calculate the proportion of FITs done in the ED and inpatient hospital setting.

We then conducted a retrospective cohort study of 382 adult patients who received FIT in the EDs and inpatient wards in both of the health system’s hospitals over the study period. All data were collected by retrospective chart review in Epic (Madison, WI) EMRs. Sampling was performed by selecting the medical record numbers corresponding to the first 50 completed FITs chronologically each month over the 8-month period, with a total of 400 charts reviewed.

Data collected included basic patient demographics, location of FIT ordering (ED vs inpatient), primary service ordering FIT, FIT indication, FIT result, and receipt and results of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Demographics collected included age, biological sex, race (self-selected), and insurance coverage.

FIT indication was determined based on resident or attending physician notes. The history of present illness, physical exam, and assessment and plan section of notes were reviewed by the lead author for a specific statement of indication for FIT or for evidence of clinical presentation for which FIT could reasonably be ordered. Indications were iteratively reviewed and collapsed into 6 different categories: anemia, iron deficiency with or without anemia, overt GIB, suspected GIB/miscellaneous, non-bloody diarrhea, and no indication identified. Overt GIB was defined as reported or witnessed hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, bright red blood per rectum, or melena irrespective of time frame (current or remote) or chronicity (acute, subacute, or chronic). In cases where signs of overt bleed were not witnessed by medical professionals, determination of conditions such as melena or coffee-ground emesis were made based on health care providers’ assessment of patient history as documented in his or her notes. Suspected GIB/miscellaneous was defined with the following parameters: any new drop in hemoglobin, abdominal pain, anorectal pain, non-bloody vomiting, hemoptysis, isolated rising blood urea nitrogen, or patient noticing blood on self, clothing, or in the commode without an identified source. Patients who were anemic and found to have iron deficiency on recent lab studies (within 6 months) were reflexively categorized into iron deficiency with or without anemia as opposed to the “anemia” category, which was comprised of any anemia without recent iron studies or non-iron deficient anemia. FIT result was determined by test result entry in Epic, with results either reading positive or negative.

Diagnostic follow-up, for our purposes, was defined as receipt of an invasive procedure or surgery, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, diagnostic and/or therapeutic abdominal surgical intervention, or any combination of these. Results of diagnostic follow-up were coded as normal or abnormal. A normal result was determined if all procedures performed were listed as normal or as “no pathological findings” on the operative or endoscopic report. Any reported pathologic findings on the operative/endoscopic report were coded as abnormal.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions were used to describe demographic characteristics of patients who received a FIT in acute hospital settings. Bivariable tables and Chi-square tests were used to compare indications and outcomes for FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients. The association between receipt of an invasive diagnostic follow-up (outcome) and the results of an inpatient FIT (predictor) was assessed using multivariable log-binomial regression to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Log-binomial regression was used over logistic regression given that adjusted odds ratios generated by logistic regression often overestimate the association between the risk factor and the outcome when the outcome is common,23 as in the case of diagnostic follow-up. The model was adjusted for variables selected a priori, specifically, age, gender, and FIT indication. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result (negative vs positive).

Results

During the 8-month study period, there were 2718 FITs ordered and completed in the acute care setting, compared to 44,662 FITs ordered and completed in the outpatient setting (5.7% performed during acute care).

Among the 400 charts reviewed, 7 were excluded from the analysis because they were duplicates from the same patient, and 11 were excluded due to insufficient information in the patient’s medical record, resulting in 382 patients included in the analysis. Patient demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Patients were predominantly Hispanic/Latino or Black/African American (51.0% and 32.5%, respectively), a majority had insurance through the county health system (50.5%), and most were male (58.1%). The average age of those receiving FIT was 52 years (standard deviation, 14.8 years), with 40.8% being under the age of 50. For a majority of patients, FIT was ordered in the ED by emergency medicine providers (79.8%). The remaining FITs were ordered by providers in 12 different inpatient departments. Of the FITs ordered, 35.1% were positive.

Indications for ordering FIT are listed in Table 2. The largest proportion of FITs were ordered for overt signs of GIB (54.2%), followed by anemia (22.0%), suspected GIB/miscellaneous reasons (12.3%), iron deficiency with or without anemia (7.6%), and non-bloody diarrhea (2.1%). In 1.8% of cases, no indication for FIT was found in the EMR. No FITs were ordered for the indication of CRC detection. Of these indication categories, overt GIB yielded the highest percentage of FIT positive results (44.0%), and non-bloody diarrhea yielded the lowest (0%).

A total of 110 patients (28.7%) underwent FIT and received invasive diagnostic follow-up. Of these 110 patients, 57 (51.8%) underwent EGD (2 of whom had further surgical intervention), 21 (19.1%) underwent colonoscopy (1 of whom had further surgical intervention), 25 (22.7%) underwent dual EGD and colonoscopy, 1 (0.9%) underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, and 6 (5.5%) directly underwent abdominal surgical intervention. There was a significantly higher rate of diagnostic follow-up for FIT-positive vs FIT-negative patients (42.9% vs 21.3%; P < 0.001). However, of the 110 patients who underwent subsequent diagnostic follow-up, 48.2% were FIT negative. FIT-negative patients who received diagnostic follow-up were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86).

Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 were diagnosed with CRC through diagnostic follow-up (1.0%). Of those 4 patients, 1 was FIT positive.

The results of the multivariable analyses to evaluate predictors of diagnostic colonoscopy are described in Table 3. Variables in the final model were FITresult, age, and FIT indication. After adjusting for other variables in the model, receipt of diagnostic follow-up was significantly associated with having a positive FIT (adjusted RR, 1.72; P < 0.001) and an overt GIB as an indication (adjusted RR, 2.00; P < 0.01).

Discussion

During the time frame of our study, 5.7% of all FITs ordered within our health system were ordered in the acute patient care setting at our hospitals. The most common indication was overt GIB, which was the indication for 54.2% of patients. Of note, none of the FITs ordered in the acute patient care setting were ordered for CRC screening. These findings support the evidence in the literature that stool-based screening tests, including FIT, are commonly used in US health care systems for diagnostic purposes and risk stratification in acute patient care to detect GIBs.13-18

Our data suggest that FIT was not a clinically useful test in determining a patient’s need for diagnostic follow-up. While having a positive FIT was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00). This salient finding is evidence that a thorough clinical history and physical exam may more strongly predict whether a patient will undergo endoscopy or other follow-up than a FIT result. These findings support other studies in the literature that have called into question the utility of FOBTs in these acute settings.13-19 Under such circumstances, FOBTs have been shown to rarely influence patient management and thus represent an unnecessary expense.13–17 Additionally, in some cases, FOBT use in these settings may negatively affect patient outcomes. Such adverse effects include delaying treatment until results are returned or obfuscating indicated management with the results (eg, a patient with indications for colonoscopy not being referred due to a negative FOBT).13,14,17

We found that, for patients who subsequently went on to have diagnostic follow-up (most commonly endoscopy), there was no difference in the likelihood of FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients to have an abnormality discovered (91.2% vs 90.6%; P = 0.86). This analysis demonstrates no post-hoc support for FIT positivity as a predictor of presence of pathology in patients who were discriminately selected for diagnostic follow-up on clinical grounds by gastroenterologists and surgeons. It does, however, further support that clinical judgment about the need for diagnostic follow-up—irrespective of FIT result—has a very high yield for discovery of pathology in the acute setting.

There are multiple reasons why FOBTs, and specifically FIT, contribute little in management decisions for patients with suspected GI blood loss. Use of FIT raises concern for both false-negatives and false-positives when used outside of its indication. Regarding false- negatives, FIT is an unreliable test for detection of blood loss from the upper GI tract. As FITs utilize antibodies to detect the presence of globin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, it is expected that FIT would fail to detect many cases of upper GI bleeding, as globin is broken down in the upper GI tract.24 This fact is part of what has made FIT a more effective CRC screening test than its guaiac-based counterparts—it has greater specificity for lower GI tract blood loss compared to tests relying on detection of heme.8 While guaiac-based assays like Hemoccult have also been shown to be poor tests in acute patient care, they may more frequently, though still unreliably, detect blood of upper GI origin. We believe that part of the ongoing use of FIT in patients with a suspected upper GIB may be from lack of understanding among providers on the mechanistic difference between gFOBTs and FITs, even though gFOBTs also yield highly unreliable results.

FIT does not have the same risk of false-positive results that guaiac-based tests have, which can yield positive results with extra-intestinal blood ingestion, aspirin, or alcohol use; insignificant GI bleeding; and consumption of peroxidase-containing foods.13,17,25 However, from a clinical standpoint, there are several scenarios of insignificant bleeding that would yield a positive FIT result, such as hemorrhoids, which are common in the US population.26,27 Additionally, in the ED, where most FITs were performed in our study, it is possible that samples for FITs are being obtained via digital rectal exam (DRE) given patients’ acuity of medical conditions and time constraints. However, FIT has been validated when using a formed stool sample. Obtaining FIT via DRE may lead to microtrauma to the rectum, which could hypothetically yield a positive FIT.

Strengths of this study include its use of in-depth chart data on a large number of FIT-positive patients, which allowed us to discern indications, outcomes, and other clinical data that may have influenced clinical decision-making. Additionally, whereas other studies that address FOBT use in acute patient care have focused on guaiac-based assays, our findings regarding the lack of utility of FIT are novel and have particular relevance as FITs continue to grow in popularity. Nonetheless, there are certain limitations future research should seek to address. In this study, the diagnostic follow-up result was coded by presence or absence of pathologic findings but did not qualify findings by severity or attempt to determine whether the pathology noted on diagnostic follow-up was the definitive source of the suspected GI bleed. These variables could help determine whether there was a difference in severity of bleeding between FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients and could potentially be studied with a prospective research design. Our own study was not designed to address the question of whether FIT result informs patient management decisions. To answer this directly, interviews would have to be conducted with those making the follow-up decision (ie, endoscopists and surgeons). Additionally, this study was not adequately powered to make determinations on the efficacy of FIT in the acute care setting for detection of CRC. As mentioned, only 1 of the 4 patients (25%) who went on to be diagnosed with CRC on follow-up was initially FIT-positive. This would require further investigation.

Conclusion

FIT is being utilized for diagnostic purposes in the acute care of symptomatic patients, which is a misuse of an established screening test for CRC. While our study was not designed to answer whether and how often a FIT result informs subsequent patient management, our results indicate that FIT is an ineffective diagnostic and risk-stratification tool when used in the acute care setting. Our findings add to existing evidence that indicates FOBTs should not be used in acute patient care.

Taken as a whole, the results of our study add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating no role for FOBTs, and specifically FIT, in acute patient care. In light of this evidence, some health care systems have already demonstrated success with system-wide disinvestment from the test in acute patient care settings, with one group publishing about their disinvestment process.28 After completion of our study, our preliminary data were presented to leadership from the internal medicine, emergency medicine, and laboratory divisions within our health care delivery system to galvanize complete disinvestment of FIT from acute care at our hospitals, a policy that was put into effect in July 2019.

Corresponding author: Nathaniel J. Spezia-Lindner, MD, Baylor College of Medicine, 7200 Cambridge St, BCM 903, Ste A10.197, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, CPRIT (PP170094, PDs: ML Jibaja-Weiss and JR Montealegre).

From Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Drs. Spezia-Lindner, Montealegre, Muldrew, and Suarez) and Harris Health System, Houston, TX (Shanna L. Harris, Maria Daheri, and Drs. Muldrew and Suarez).

Abstract

Objective: To characterize and analyze the prevalence, indications for, and outcomes of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in acute patient care within a safety net health care system’s emergency departments (EDs) and inpatient settings.

Design: Retrospective cohort study derived from administrative data.

Setting: A large, urban, safety net health care delivery system in Texas. The data gathered were from the health care system’s 2 primary hospitals and their associated EDs. This health care system utilizes FIT exclusively for fecal occult blood testing.

Participants: Adults ≥18 years who underwent FIT in the ED or inpatient setting between August 2016 and March 2017. Chart review abstractions were performed on a sample (n = 382) from the larger subset.

Measurements: Primary data points included total FITs performed in acute patient care during the study period, basic demographic data, FIT indications, FIT result, receipt of invasive diagnostic follow-up, and result of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Multivariable log-binomial regression was used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) to assess the association between FIT result and receipt of diagnostic follow-up. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result.

Results: During the 8-month study period, 2718 FITs were performed in the ED and inpatient setting, comprising 5.7% of system-wide FITs. Of the 382 patients included in the chart review who underwent acute care FIT, a majority had their test performed in the ED (304, 79.6%), 133 of which were positive (34.8%). The most common indication for FIT was evidence of overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (207, 54.2%), followed by anemia (84, 22.0%). While a positive FIT result was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72; P < 0.001), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00; P = 0.003). Of patients who underwent FIT and received diagnostic follow-up (n = 110), 48.2% were FIT negative. These patients were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86). Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 (1.0%) were subsequently diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC). Of those 4 patients, 1 (25%) was FIT positive.

Conclusion: FIT is being utilized in acute patient care outside of its established indication for CRC screening in asymptomatic, average-risk adults. Our study demonstrates that FIT is not useful in acute patient care.

Keywords: FOBT; FIT; fecal immunochemical testing; inpatient.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States. It is estimated that in 2020, 147,950 individuals will be diagnosed with invasive CRC and 53,200 will die from it.1 While the overall incidence has been declining for decades, it is rising in young adults.2–4 Screening using direct visualization procedures (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy) and stool-based tests has been demonstrated to improve detection of precancerous and early cancerous lesions, thereby reducing CRC mortality.5 However, screening rates in the United States are suboptimal, with only 68.8% of adults aged 50 to 75 years screened according to guidelines in 2018.6Stool-based testing is a well-established and validated screening measure for CRC in asymptomatic individuals at average risk. Its widespread use in this population has been shown to cost-effectively screen for CRC among adults 50 years of age and older.5,7 Presently, the 2 most commonly used stool-based assays in the US health care system are guaiac-based tests (guaiac fecal occult blood test [gFOBT], Hemoccult) and

Despite the exclusive validation of FOBTs for use in CRC screening, studies have demonstrated that they are commonly used for a multitude of additional indications in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings, most aimed at detecting or confirming GI blood loss. This may lead to inappropriate patient management, including the receipt of unnecessary follow-up procedures, which can incur significant costs to the patient and the health system.13-19 These costs may be particularly burdensome in safety net health systems (ie, those that offer access to care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay), which serve a large proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals in the United States.20,21 To our knowledge, no published study to date has specifically investigated the role of FIT in acute patient management.

This study characterizes the use of FIT in acute patient care within a large, urban, safety net health care system. Through a retrospective review of administrative data and patient charts, we evaluated FIT use prevalence, indications, and patient outcomes in the ED and inpatient settings.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in a large, urban, county-based integrated delivery system in Houston, Texas, that provides health care services to one of the largest uninsured and underinsured populations in the country.22 The health system includes 2 main hospitals and more than 20 ambulatory care clinics. Within its ambulatory care clinics, the health system implements a population-based screening strategy using stool-based testing. All adults aged 50 years or older who are due for FIT are identified through the health-maintenance module of the electronic medical record (EMR) and offered a take-home FIT. The health system utilizes FIT exclusively (OC-Light S FIT, Polymedco, Cortlandt Manor, NY); no guaiac-based assays are available.

Design and Data Collection

We began by using administrative records to determine the proportion of FITs conducted health system-wide that were ordered and completed in the acute care setting over the study period (August 2016-March 2017). Specifically, we used aggregate quality metric reports, which quantify the number of FITs conducted at each health system clinic and hospital each month, to calculate the proportion of FITs done in the ED and inpatient hospital setting.

We then conducted a retrospective cohort study of 382 adult patients who received FIT in the EDs and inpatient wards in both of the health system’s hospitals over the study period. All data were collected by retrospective chart review in Epic (Madison, WI) EMRs. Sampling was performed by selecting the medical record numbers corresponding to the first 50 completed FITs chronologically each month over the 8-month period, with a total of 400 charts reviewed.

Data collected included basic patient demographics, location of FIT ordering (ED vs inpatient), primary service ordering FIT, FIT indication, FIT result, and receipt and results of invasive diagnostic follow-up. Demographics collected included age, biological sex, race (self-selected), and insurance coverage.

FIT indication was determined based on resident or attending physician notes. The history of present illness, physical exam, and assessment and plan section of notes were reviewed by the lead author for a specific statement of indication for FIT or for evidence of clinical presentation for which FIT could reasonably be ordered. Indications were iteratively reviewed and collapsed into 6 different categories: anemia, iron deficiency with or without anemia, overt GIB, suspected GIB/miscellaneous, non-bloody diarrhea, and no indication identified. Overt GIB was defined as reported or witnessed hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, bright red blood per rectum, or melena irrespective of time frame (current or remote) or chronicity (acute, subacute, or chronic). In cases where signs of overt bleed were not witnessed by medical professionals, determination of conditions such as melena or coffee-ground emesis were made based on health care providers’ assessment of patient history as documented in his or her notes. Suspected GIB/miscellaneous was defined with the following parameters: any new drop in hemoglobin, abdominal pain, anorectal pain, non-bloody vomiting, hemoptysis, isolated rising blood urea nitrogen, or patient noticing blood on self, clothing, or in the commode without an identified source. Patients who were anemic and found to have iron deficiency on recent lab studies (within 6 months) were reflexively categorized into iron deficiency with or without anemia as opposed to the “anemia” category, which was comprised of any anemia without recent iron studies or non-iron deficient anemia. FIT result was determined by test result entry in Epic, with results either reading positive or negative.

Diagnostic follow-up, for our purposes, was defined as receipt of an invasive procedure or surgery, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, diagnostic and/or therapeutic abdominal surgical intervention, or any combination of these. Results of diagnostic follow-up were coded as normal or abnormal. A normal result was determined if all procedures performed were listed as normal or as “no pathological findings” on the operative or endoscopic report. Any reported pathologic findings on the operative/endoscopic report were coded as abnormal.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions were used to describe demographic characteristics of patients who received a FIT in acute hospital settings. Bivariable tables and Chi-square tests were used to compare indications and outcomes for FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients. The association between receipt of an invasive diagnostic follow-up (outcome) and the results of an inpatient FIT (predictor) was assessed using multivariable log-binomial regression to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Log-binomial regression was used over logistic regression given that adjusted odds ratios generated by logistic regression often overestimate the association between the risk factor and the outcome when the outcome is common,23 as in the case of diagnostic follow-up. The model was adjusted for variables selected a priori, specifically, age, gender, and FIT indication. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportion of abnormal findings on diagnostic follow-up by FIT result (negative vs positive).

Results

During the 8-month study period, there were 2718 FITs ordered and completed in the acute care setting, compared to 44,662 FITs ordered and completed in the outpatient setting (5.7% performed during acute care).

Among the 400 charts reviewed, 7 were excluded from the analysis because they were duplicates from the same patient, and 11 were excluded due to insufficient information in the patient’s medical record, resulting in 382 patients included in the analysis. Patient demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Patients were predominantly Hispanic/Latino or Black/African American (51.0% and 32.5%, respectively), a majority had insurance through the county health system (50.5%), and most were male (58.1%). The average age of those receiving FIT was 52 years (standard deviation, 14.8 years), with 40.8% being under the age of 50. For a majority of patients, FIT was ordered in the ED by emergency medicine providers (79.8%). The remaining FITs were ordered by providers in 12 different inpatient departments. Of the FITs ordered, 35.1% were positive.

Indications for ordering FIT are listed in Table 2. The largest proportion of FITs were ordered for overt signs of GIB (54.2%), followed by anemia (22.0%), suspected GIB/miscellaneous reasons (12.3%), iron deficiency with or without anemia (7.6%), and non-bloody diarrhea (2.1%). In 1.8% of cases, no indication for FIT was found in the EMR. No FITs were ordered for the indication of CRC detection. Of these indication categories, overt GIB yielded the highest percentage of FIT positive results (44.0%), and non-bloody diarrhea yielded the lowest (0%).

A total of 110 patients (28.7%) underwent FIT and received invasive diagnostic follow-up. Of these 110 patients, 57 (51.8%) underwent EGD (2 of whom had further surgical intervention), 21 (19.1%) underwent colonoscopy (1 of whom had further surgical intervention), 25 (22.7%) underwent dual EGD and colonoscopy, 1 (0.9%) underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, and 6 (5.5%) directly underwent abdominal surgical intervention. There was a significantly higher rate of diagnostic follow-up for FIT-positive vs FIT-negative patients (42.9% vs 21.3%; P < 0.001). However, of the 110 patients who underwent subsequent diagnostic follow-up, 48.2% were FIT negative. FIT-negative patients who received diagnostic follow-up were just as likely to have an abnormal finding as FIT-positive patients (90.6% vs 91.2%; P = 0.86).

Of the 382 patients in the study, 4 were diagnosed with CRC through diagnostic follow-up (1.0%). Of those 4 patients, 1 was FIT positive.

The results of the multivariable analyses to evaluate predictors of diagnostic colonoscopy are described in Table 3. Variables in the final model were FITresult, age, and FIT indication. After adjusting for other variables in the model, receipt of diagnostic follow-up was significantly associated with having a positive FIT (adjusted RR, 1.72; P < 0.001) and an overt GIB as an indication (adjusted RR, 2.00; P < 0.01).

Discussion

During the time frame of our study, 5.7% of all FITs ordered within our health system were ordered in the acute patient care setting at our hospitals. The most common indication was overt GIB, which was the indication for 54.2% of patients. Of note, none of the FITs ordered in the acute patient care setting were ordered for CRC screening. These findings support the evidence in the literature that stool-based screening tests, including FIT, are commonly used in US health care systems for diagnostic purposes and risk stratification in acute patient care to detect GIBs.13-18

Our data suggest that FIT was not a clinically useful test in determining a patient’s need for diagnostic follow-up. While having a positive FIT was significantly associated with obtaining a diagnostic exam in multivariate analysis (RR, 1.72), having signs of overt GI bleeding was a stronger predictor of diagnostic follow-up (RR, 2.00). This salient finding is evidence that a thorough clinical history and physical exam may more strongly predict whether a patient will undergo endoscopy or other follow-up than a FIT result. These findings support other studies in the literature that have called into question the utility of FOBTs in these acute settings.13-19 Under such circumstances, FOBTs have been shown to rarely influence patient management and thus represent an unnecessary expense.13–17 Additionally, in some cases, FOBT use in these settings may negatively affect patient outcomes. Such adverse effects include delaying treatment until results are returned or obfuscating indicated management with the results (eg, a patient with indications for colonoscopy not being referred due to a negative FOBT).13,14,17

We found that, for patients who subsequently went on to have diagnostic follow-up (most commonly endoscopy), there was no difference in the likelihood of FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients to have an abnormality discovered (91.2% vs 90.6%; P = 0.86). This analysis demonstrates no post-hoc support for FIT positivity as a predictor of presence of pathology in patients who were discriminately selected for diagnostic follow-up on clinical grounds by gastroenterologists and surgeons. It does, however, further support that clinical judgment about the need for diagnostic follow-up—irrespective of FIT result—has a very high yield for discovery of pathology in the acute setting.

There are multiple reasons why FOBTs, and specifically FIT, contribute little in management decisions for patients with suspected GI blood loss. Use of FIT raises concern for both false-negatives and false-positives when used outside of its indication. Regarding false- negatives, FIT is an unreliable test for detection of blood loss from the upper GI tract. As FITs utilize antibodies to detect the presence of globin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, it is expected that FIT would fail to detect many cases of upper GI bleeding, as globin is broken down in the upper GI tract.24 This fact is part of what has made FIT a more effective CRC screening test than its guaiac-based counterparts—it has greater specificity for lower GI tract blood loss compared to tests relying on detection of heme.8 While guaiac-based assays like Hemoccult have also been shown to be poor tests in acute patient care, they may more frequently, though still unreliably, detect blood of upper GI origin. We believe that part of the ongoing use of FIT in patients with a suspected upper GIB may be from lack of understanding among providers on the mechanistic difference between gFOBTs and FITs, even though gFOBTs also yield highly unreliable results.

FIT does not have the same risk of false-positive results that guaiac-based tests have, which can yield positive results with extra-intestinal blood ingestion, aspirin, or alcohol use; insignificant GI bleeding; and consumption of peroxidase-containing foods.13,17,25 However, from a clinical standpoint, there are several scenarios of insignificant bleeding that would yield a positive FIT result, such as hemorrhoids, which are common in the US population.26,27 Additionally, in the ED, where most FITs were performed in our study, it is possible that samples for FITs are being obtained via digital rectal exam (DRE) given patients’ acuity of medical conditions and time constraints. However, FIT has been validated when using a formed stool sample. Obtaining FIT via DRE may lead to microtrauma to the rectum, which could hypothetically yield a positive FIT.

Strengths of this study include its use of in-depth chart data on a large number of FIT-positive patients, which allowed us to discern indications, outcomes, and other clinical data that may have influenced clinical decision-making. Additionally, whereas other studies that address FOBT use in acute patient care have focused on guaiac-based assays, our findings regarding the lack of utility of FIT are novel and have particular relevance as FITs continue to grow in popularity. Nonetheless, there are certain limitations future research should seek to address. In this study, the diagnostic follow-up result was coded by presence or absence of pathologic findings but did not qualify findings by severity or attempt to determine whether the pathology noted on diagnostic follow-up was the definitive source of the suspected GI bleed. These variables could help determine whether there was a difference in severity of bleeding between FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients and could potentially be studied with a prospective research design. Our own study was not designed to address the question of whether FIT result informs patient management decisions. To answer this directly, interviews would have to be conducted with those making the follow-up decision (ie, endoscopists and surgeons). Additionally, this study was not adequately powered to make determinations on the efficacy of FIT in the acute care setting for detection of CRC. As mentioned, only 1 of the 4 patients (25%) who went on to be diagnosed with CRC on follow-up was initially FIT-positive. This would require further investigation.

Conclusion

FIT is being utilized for diagnostic purposes in the acute care of symptomatic patients, which is a misuse of an established screening test for CRC. While our study was not designed to answer whether and how often a FIT result informs subsequent patient management, our results indicate that FIT is an ineffective diagnostic and risk-stratification tool when used in the acute care setting. Our findings add to existing evidence that indicates FOBTs should not be used in acute patient care.

Taken as a whole, the results of our study add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating no role for FOBTs, and specifically FIT, in acute patient care. In light of this evidence, some health care systems have already demonstrated success with system-wide disinvestment from the test in acute patient care settings, with one group publishing about their disinvestment process.28 After completion of our study, our preliminary data were presented to leadership from the internal medicine, emergency medicine, and laboratory divisions within our health care delivery system to galvanize complete disinvestment of FIT from acute care at our hospitals, a policy that was put into effect in July 2019.

Corresponding author: Nathaniel J. Spezia-Lindner, MD, Baylor College of Medicine, 7200 Cambridge St, BCM 903, Ste A10.197, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, CPRIT (PP170094, PDs: ML Jibaja-Weiss and JR Montealegre).

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. 10.1CA Cancer 10.1J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30.

2. Howlader NN, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute; 2017:1-2.

3. Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. 10.1J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322.

4. Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. 10.25JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):17-22.

5. Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 10.25JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576-2594.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. October 22, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

7. Hewitson P, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer using the fecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. 10.25Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(1):CD001216.

8. Bujanda L, Lanas Á, Quintero E, et al. Effect of aspirin and antiplatelet drugs on the outcome of the fecal immunochemical test. 10.25Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(7):683-689.

9. Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. 10.25J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462-1470.

10. Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Lepage C, et al. Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests are superior to guaiac-based tests for the detection of colorectal neoplasms. 10.25Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(15):2254-2258.

11. Hol L, Wilschut JA, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing at different cut-off levels. 10.25Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1103-1110.

12. Levi Z, Birkenfeld S, Vilkin A, et al. A higher detection rate for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyp for screening with immunochemical fecal occult blood test than guaiac fecal occult blood test, despite lower compliance rate. A prospective, controlled, feasibility study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(10):2415-2424.

13. Friedman A, Chan A, Chin LC, et al. Use and abuse of faecal occult blood tests in an acute hospital inpatient setting. Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):107-111.

14. Narula N, Ulic D, Al-Dabbagh R, et al. Fecal occult blood testing as a diagnostic test in symptomatic patients is not useful: a retrospective chart review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(8):421-426.

15. Ip S, Sokoro AA, Kaita L, et al. Use of fecal occult blood testing in hospitalized patients: results of an audit. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(9):489-494.

16. Mosadeghi S, Ren H, Catungal J, et al. Utilization of fecal occult blood test in the acute hospital setting and its impact on clinical management and outcomes. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62(2):91-95.

17. van Rijn AF, Stroobants AK, Deutekom M, et al. Inappropriate use of the faecal occult blood test in a university hospital in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1266-1269.

18. Sharma VK, Komanduri S, Nayyar S, et al. An audit of the utility of in-patient fecal occult blood testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):1256-1260.

19. Chiang TH, Lee YC, Tu CH, et al. Performance of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test in predicting lesions in the lower gastrointestinal tract. CMAJ. 2011;183(13):1474-1481.

20. Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM. Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1790-1796.

21. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Halm EA. National use of safety net clinics for primary care among adults with non-Medicaid insurance in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151610.

22. United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Selected Economic Characteristics. 2019. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03%20Texas&g=0400000US48&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03&hidePreview=true

23. McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940-943.

24. Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):699-718.

25. Macrae FA, St John DJ. Relationship between patterns of bleeding and Hemoccult sensitivity in patients with colorectal cancers or adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1982;82(5 pt 1):891-898.

26. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380-386.

27. Fleming JL, Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, et al. Influence of aspirin and ethanol on fecal blood levels as determined by using the HemoQuant assay. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62(3):159-163.

28. Gupta A, Tang Z, Agrawal D. Eliminating in-hospital fecal occult blood testing: our experience with disinvestment. Am J Med. 2018;131(7):760-763.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. 10.1CA Cancer 10.1J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30.

2. Howlader NN, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute; 2017:1-2.

3. Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. 10.1J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8):djw322.

4. Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. 10.25JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):17-22.

5. Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 10.25JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576-2594.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of colorectal cancer screening tests. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. October 22, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm

7. Hewitson P, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer using the fecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. 10.25Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(1):CD001216.

8. Bujanda L, Lanas Á, Quintero E, et al. Effect of aspirin and antiplatelet drugs on the outcome of the fecal immunochemical test. 10.25Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(7):683-689.

9. Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. 10.25J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462-1470.

10. Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Lepage C, et al. Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests are superior to guaiac-based tests for the detection of colorectal neoplasms. 10.25Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(15):2254-2258.

11. Hol L, Wilschut JA, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing at different cut-off levels. 10.25Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1103-1110.

12. Levi Z, Birkenfeld S, Vilkin A, et al. A higher detection rate for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyp for screening with immunochemical fecal occult blood test than guaiac fecal occult blood test, despite lower compliance rate. A prospective, controlled, feasibility study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(10):2415-2424.

13. Friedman A, Chan A, Chin LC, et al. Use and abuse of faecal occult blood tests in an acute hospital inpatient setting. Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):107-111.

14. Narula N, Ulic D, Al-Dabbagh R, et al. Fecal occult blood testing as a diagnostic test in symptomatic patients is not useful: a retrospective chart review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(8):421-426.

15. Ip S, Sokoro AA, Kaita L, et al. Use of fecal occult blood testing in hospitalized patients: results of an audit. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(9):489-494.

16. Mosadeghi S, Ren H, Catungal J, et al. Utilization of fecal occult blood test in the acute hospital setting and its impact on clinical management and outcomes. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62(2):91-95.

17. van Rijn AF, Stroobants AK, Deutekom M, et al. Inappropriate use of the faecal occult blood test in a university hospital in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1266-1269.

18. Sharma VK, Komanduri S, Nayyar S, et al. An audit of the utility of in-patient fecal occult blood testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):1256-1260.

19. Chiang TH, Lee YC, Tu CH, et al. Performance of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test in predicting lesions in the lower gastrointestinal tract. CMAJ. 2011;183(13):1474-1481.

20. Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM. Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1790-1796.

21. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Halm EA. National use of safety net clinics for primary care among adults with non-Medicaid insurance in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151610.

22. United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Selected Economic Characteristics. 2019. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03%20Texas&g=0400000US48&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03&hidePreview=true

23. McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940-943.

24. Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):699-718.

25. Macrae FA, St John DJ. Relationship between patterns of bleeding and Hemoccult sensitivity in patients with colorectal cancers or adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1982;82(5 pt 1):891-898.

26. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380-386.

27. Fleming JL, Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, et al. Influence of aspirin and ethanol on fecal blood levels as determined by using the HemoQuant assay. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62(3):159-163.

28. Gupta A, Tang Z, Agrawal D. Eliminating in-hospital fecal occult blood testing: our experience with disinvestment. Am J Med. 2018;131(7):760-763.

Cracking the clinician educator code in gastroenterology