User login

Closing the racial gap in minimally invasive gyn hysterectomy and myomectomy

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

Discharges Against Medical Advice

Patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA) for a variety of reasons. The AMA rate is approximately 1% nationally but substantially higher at safety-net hospitals and has rapidly increased over the past decade.1-5 The principle that patients have the right to make choices about their healthcare, up to and including whether to leave the hospital against the advice of medical staff, is well-established law and a foundation of medical ethics.6 In practice, however, AMA discharges are often emotionally charged for both patients and providers, and, in the high-stress setting of AMA discharge, providers may be confused about their roles.7-9

The demographics of patients who leave AMA have been well described. Compared with conventionally discharged patients, AMA patients are younger, more likely to be male, and more likely a marginalized ethnic or racial minority.10-14 Patients with mental illnesses and addiction issues are overrepresented in AMA discharges, and complicated capacity assessments and limited resources may strain providers.7,8,15,16 Studies have repeatedly shown higher rates of readmission and mortality for AMA patients than for conventionally discharged patients.17-21 Whether AMA discharge is a marker for other prognostic factors that bode poorly for patients or contributes to negative outcomes, data suggest this group of patients is vulnerable, having mortality rates up to 40% higher 1 year after discharge, relative to conventionally discharged patients.12

Several models of standardized best practice approaches for AMA have been proposed by bioethicists.6,22,23 Although details of these approaches vary, all involve assessing the patient’s decision-making capacity, clarifying the risks of AMA discharge, addressing factors that might be prompting the discharge, formulating an alternative outpatient treatment plan or “next best” option, and documenting extensively. A recent study found patients often gave advance warning of an AMA discharge, but physicians rarely prepared by arranging follow-up care.8 The investigators hypothesized that providers might not have known what they were permitted to arrange for AMA patients, or might have thought that providing “second best” options went against their principles. The investigators noted that nurses might have become aware of AMA risk sooner than physicians did but could not act on this awareness by preparing medications and arranging follow-up.

Translating models of best practice care for AMA patients into clinical practice requires buy-in from bedside providers, not just bioethicists. Given the study findings that providers have misconceptions about their roles in the AMA discharge,7 it is prudent to investigate providers’ current practices, beliefs, and concerns about AMA discharges before introducing a new approach.

The present authors conducted a mixed-methods cross-sectional study of the state of AMA discharges at Highland Hospital (Oakland, California), a 236-bed county hospital and trauma center serving a primarily underserved urban patient population. The aim of this study was to assess current provider practices for AMA discharges and provider perceptions and knowledge about AMA discharges, ultimately to help direct future educational interventions with medical providers or hospital policy changes needed to improve the quality of AMA discharges.

METHODS

Phase 1 of this study involved identifying AMA patients through a review of data from Highland Hospital’s electronic medical records for 2014. These data included discharge status (eg, AMA vs other discharge types). The hospital’s floor clerk distinguishes between absent without official leave (AWOL; the patient leaves without notifying a provider) and AMA discharge. Discharges designated AWOL were excluded from the analyses.

In phase 2, a structured chart review (Appendix A) was performed for all patients identified during phase 1 as being discharged AMA in 2014. In these reviews, further assessment was made of patient and visit characteristics in hospitalizations that ended in AMA discharge, and of providers’ documentation of AMA discharges—that is, whether several factors were documented (capacity; predischarge indication that patient might leave AMA; reason for AMA; and indications that discharge medications, transportation, and follow-up were arranged). These visit factors were reviewed because the literature has identified them as being important markers for AMA discharge safety.6,8 Two research assistants, under the guidance of Dr. Stearns, reviewed the charts. To ensure agreement across chart reviews with respect to subjective questions (eg, whether capacity was adequately documented), the group reviewed the first 10 consecutive charts together; there was full agreement on how to classify the data of interest. Throughout the study, whenever a research assistant asked how to classify particular patient data, Dr. Stearns reviewed the data, and the research team made a decision together. Additional data, for AMA patients and for all patients admitted to Highland Hospital, were obtained from the hospital’s data warehouse, which pools data from within the health system.

Phase 3 involved surveying healthcare providers who were involved in patient care on the internal medicine and trauma surgery services at the hospital. These providers were selected because chart review revealed that the vast majority of patients who left AMA in 2014 were on one of these services. Surveys (Appendix B) asked participant providers to identify their role at the hospital, to provide a self-assessment of competence in various aspects of AMA discharge, to voice opinions about provider responsibilities in arranging follow-up for AMA patients, and to make suggestions about the AMA process. The authors designed these surveys, which included questions about aspects of care that have been highlighted in the AMA discharge literature as being important for AMA discharge safety.6,8,22,23 Surveys were distributed to providers at internal medicine and trauma surgery department meetings and nursing conferences. Data (without identifying information) were analyzed, and survey responses kept anonymous.

The Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board approved this project. Providers were given the option of writing their name and contact information at the top of the survey in order to be entered into a drawing to receive a prize for completion.

We performed statistical analyses of the patient charts and physician survey data using Stata (version 14.0, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). We analyzed both patient- and encounter-level data. In demographic analyses, this approach prevented duplicate counting of patients who left AMA multiple times. Patient-level analyses compared the demographic characteristics of AMA patients and patients discharged conventionally from the hospital in 2014. In addition, patients with either 1 or multiple AMA discharges were compared to identify characteristics that might be linked to highest risk of recurrent AMA discharge in the hope that early identification of these patients might facilitate providers’ early awareness and preparation for follow-up care or hospitalization alternatives. We used ANOVAs for continuous variables and tests of proportions for categorical variables. On the encounter level, analyses examined data about each admission (eg, AMA forms signed, follow-up arrangements made, capacity documented, etc.) for all AMA discharges. We employed chi square tests to identify variations in healthcare provider survey responses. A P value < 0.05 was used as the significance cut-off point.

Staged logistic regression analyses, adjusted for demographic characteristics, were performed to assess the association between risk of leaving AMA (yes or no) and demographic characteristics and the association between risk of leaving AMA more than once (yes or no) and health-related characteristics.

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical, and Utilization Characteristics

Of the 12,036 Highland Hospital admissions in 2014, 319 (2.7%) ended with an AMA discharge. Of the 8207 individual patients discharged, 268 left AMA once, and 29 left AMA multiple times. Further review of the Admissions, Discharges, and Transfers Report generated from the electronic medical record revealed that 15 AWOL discharges were misclassified as AMA discharges.

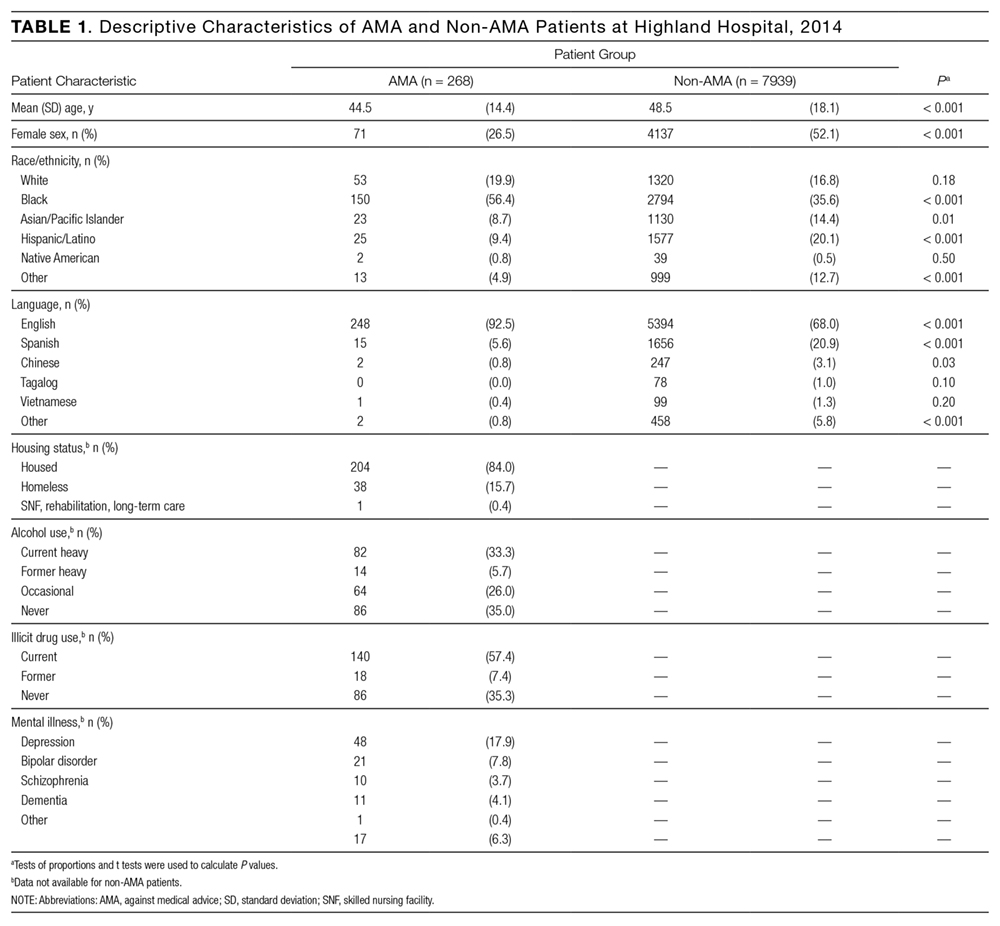

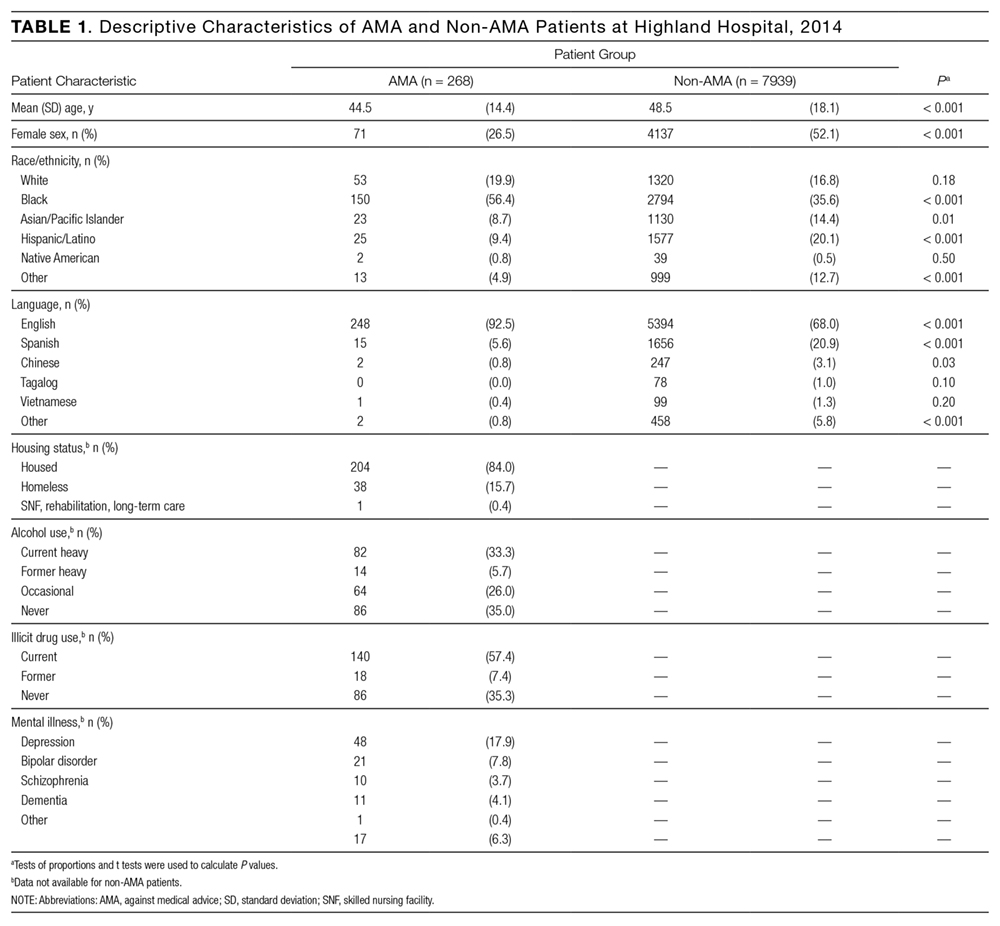

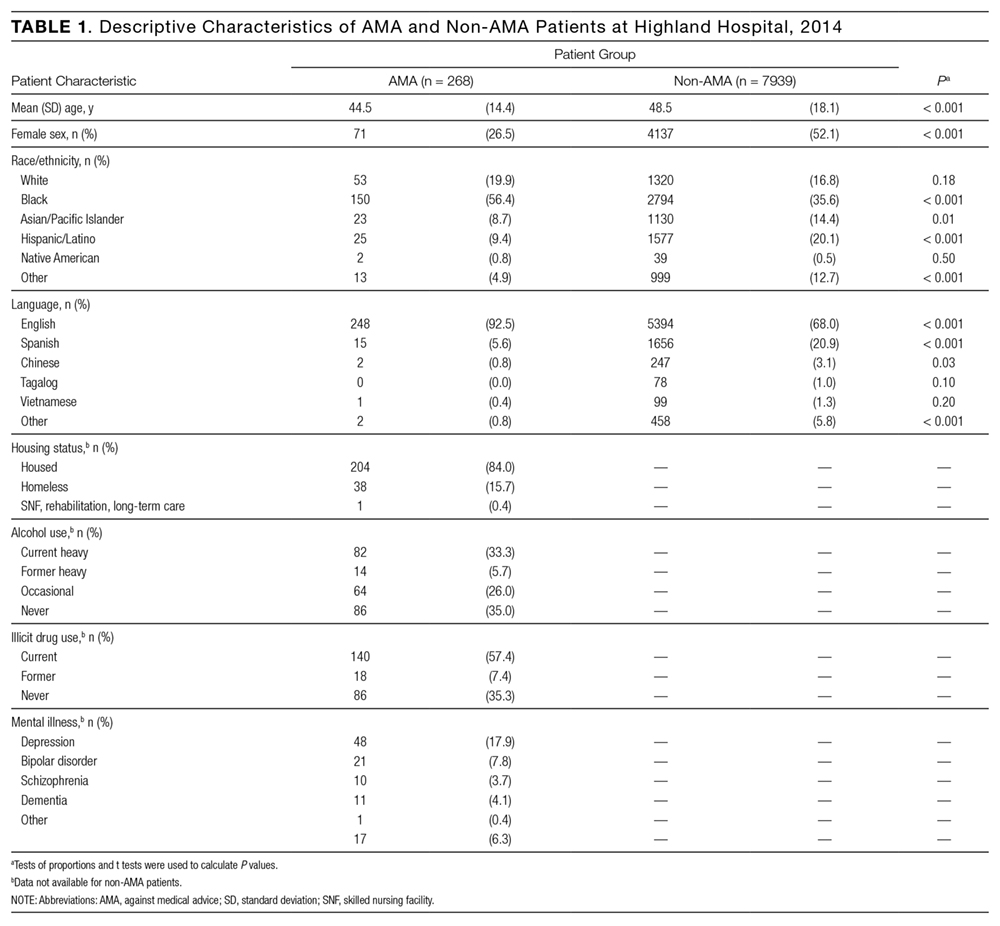

Compared with patients discharged conventionally, AMA patients were significantly younger; more likely to be male, to self-identify as Black/African American, and to be English-speaking; and less likely to self-identify as Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic/Latino or to be Chinese- or Spanish-speaking (Table 1). They were also more likely than all patients admitted to Highland to be homeless (15.7% vs 8.7%; P < 0.01). Multivariate regression analysis revealed persistent age and sex disparities, but racial disparities were mitigated in adjusted analyses (Appendix C). Language disparities persisted only for Spanish speakers, who had a significantly lower rate of AMA discharge, even in adjusted analyses.

The majority of AMA patients were on the internal medicine service (63.5%) or the trauma surgery service (24.8%). Regarding admission diagnosis, 17.2% of AMA patients were admitted for infections, 5.0% for drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, 38.9% for acute noninfectious illnesses, 16.7% for decompensation of chronic disease, 18.4% for injuries or trauma, and 3.8% for pregnancy complications or labor. Compared with patients who left AMA once, patients who left AMA multiple times had higher rates of heavy alcohol use (53.9% vs 30.9%; P = 0.01) and illicit drug use (88.5% vs 53.7%; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, the increased odds of leaving AMA more than once persisted for current heavy illicit drug users compared with patients who had never engaged in illicit drug use.

Discharge Characteristics and Documentation

Providers documented a patient’s plan to leave AMA before actual discharge 17.3% of the time. The documented plan to leave had to indicate that the patient was actually considering leaving. For example, “Patient is eager to go home” was not enough to qualify as a plan, but “Patient is thinking of leaving” qualified. For 84.3% of AMA discharges, the hospital’s AMA form was signed and was included in the medical record. Documentation showed that medications were prescribed for AMA patients 21.4% of the time, follow-up was arranged 25.7% of the time, and follow-up was pending arrangement 14.8% of the time. The majority of AMA patients (71.4%) left during daytime hours. In 29.6% of AMA discharges, providers documented AMA patients had decision-making capacity.

Readmission After AMA Discharge

Of the 268 AMA patients, 67.7% were not readmitted within the 6 months after AMA, 24.5% had 1 or 2 readmissions, and the rest had 3 or more readmissions (1 patient had 15). In addition, 35.8% returned to the emergency department within 30 days, and 16.4% were readmitted within 30 days. In 2014, the hospital’s overall 30-day readmission rate was 10.8%. Of the patients readmitted within 6 months after AMA, 23.5% left AMA again at the next visit, 9.4% left AWOL, and 67.1% were discharged conventionally.

Drivers of Premature Discharge

Qualitative analysis of the 35.5% of patient charts documenting a reason for leaving the hospital revealed 3 broad, interrelated themes (Figure 1). The first theme, dissatisfaction with hospital care, included chart notations such as “His wife couldn’t sleep in the hospital room” and “Not satisfied with all-liquid diet.” The second theme, urgent personal issues, included comments such as “He has a very important court date for his children” and “He needed to take care of immigration forms.” The third theme, mental health and substance abuse issues, included notations such as “He wants to go smoke” and “Severe anxiety and prison flashbacks.”

Provider Self-Assessment and Beliefs

The survey was completed by 178 healthcare providers: 49.4% registered nurses, 19.1% trainee physicians, 20.8% attending physicians, and 10.7% other providers, including chaplains, social workers, and clerks. Regarding self-assessment of competency in AMA discharges, 94% of providers agreed they were comfortable assessing capacity, and 94% agreed they were comfortable talking with patients about the risks of leaving AMA (Figure 2). Nurses were more likely than trainee physicians to agree they knew what to do for patients who lacked capacity (74% vs 49%; P = 0.02). Most providers (70%) agreed they usually knew why their patients were leaving AMA; in this self-assessment, there were no significant differences between types of providers.

Regarding follow-up, attending physicians and trainee physicians demonstrated more agreement than nurses that AMA patients should receive medications and follow-up (94% and 84% vs 64%; P < 0.05). Nurses were more likely than attending physicians to say patients should lose their rights to hospital follow-up because of leaving AMA (38% vs 6%; P < 0.01). A minority of providers (37%) agreed transportation should be arranged. Addiction was the most common driver of AMA discharge (35%), followed by familial obligations (19%), dissatisfaction with hospital care (16%), and financial concerns (15%).

DISCUSSION

The demographic characteristics of AMA patients in this study are similar to those identified in other studies, showing overrepresentation of young male patients.12,14 Homeless patients were also overrepresented in the AMA discharge population at Highland Hospital—a finding that has not been consistently reported in prior studies, and that warrants further examination. In adjusted analyses, Spanish speakers had a lower rate of AMA discharge, and there were no racial variations. This is consistent with another study’s finding: that racial disparities in AMA discharge rates were largely attributable to confounders.24 Language differences may result from failure of staff to fully explain the option of AMA discharge to non-English speakers, or from fear of immigration consequences after AMA discharge. Further investigation of patient experiences is needed to identify factors that contribute to demographic variations in AMA discharge rates.25,26

Of the patients who left AMA multiple times, nearly all were actively using illicit drugs. In a recent study conducted at a safety-net hospital in Vancouver, Canada, 43% of patients with illicit drug use and at least 1 hospitalization left AMA at least once during the 6-year study period.11 Many factors might explain this correlation—addiction itself, poor pain control for patients with addiction issues, fears about incarceration, and poor treatment of drug users by healthcare staff.15 Although the medical literature highlights deficits in pain control for patients addicted to opiates, proposed solutions are sparse and focus on perioperative pain control and physician prescribing practices.27,28 At safety-net hospitals in which addiction is a factor in many hospitalizations, there is opportunity for new research in inpatient pain control for patients with substance dependence. In addition, harm reduction strategies—such as methadone maintenance for hospitalized patients with opiate dependence and abscess clinics as hospitalization alternatives for injection-associated infection treatment—may be key in improving safety for patients.11,15,29

Comparing the provider survey and chart review results highlights discordance between provider beliefs and clinical practice. Healthcare providers at Highland Hospital considered themselves competent in assessing capacity and talking with patients about the risks of AMA discharge. In practice, however, capacity was documented in less than a third of AMA discharges. Although the majority of providers thought medications and follow-up should be arranged for patients, arrangements were seldom made. This may be partially attributable to limited resources for making these arrangements. Average time to “third next available” primary care appointment within the county health system that includes Highland was 44.6 days for established patients during the period of study; for new primary care patients, the average wait for an appointment was 2 to 3 months. Highland has a same-day clinic, but inpatient providers are discouraged from using it as a postdischarge clinic for patients who would be better served in primary care. Medications and transportation are easily arranged during daytime hours but are not immediately available at night. In addition, some of this discrepancy may be attributable to the limited documentation rather than to provider failure to achieve their own benchmarks of quality care for AMA patients.

Documentation in AMA discharges is key for multiple reasons. Most AMA patients in this study signed an AMA form, and it could be that the rate of documenting decision-making capacity was low because providers thought a signed AMA form was adequate documentation of capacity and informed consent. In numerous court cases, however, these forms were found to be insufficient evidence of informed consent (lacking other supportive documentation) and possibly to go against the public good.30 In addition, high rates of repeat emergency department visits and readmissions for AMA patients, demonstrated here and in other studies, highlight the importance of careful documentation in informing subsequent providers about hospital returnees’ ongoing issues.17-19