User login

Renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

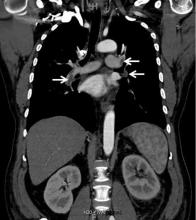

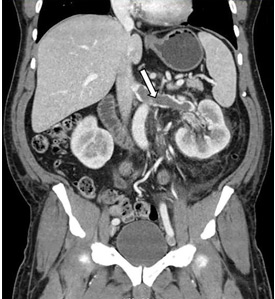

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

An unusual complication of peritoneal dialysis

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

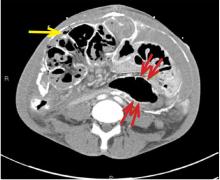

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

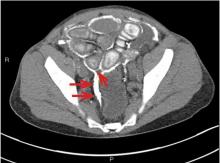

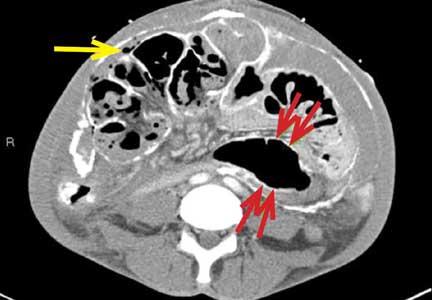

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271