User login

Inverse Distribution of Pink Macules and Patches

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

A 73-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic progressive rash on the left wrist, waist, groin, and inner thighs of 2 months’ duration. Her primary care provider prescribed clotrimazole and fluconazole with no improvement. Review of systems was negative. Medications included omeprazole, candesartan hydrochlorothiazide, potassium chloride, and levothyroxine. Physical examination revealed many scattered, pink to violaceous macules and patches in the axillae (sparing the vaults) and inguinal folds as well as on the waist and medial upper thighs. The lesions were without scale or other epidermal change. She also had a pink papule on the left volar wrist. A Wood lamp examination was unremarkable, and punch biopsies were performed.

Verrucous Plaque on the Leg

Blastomycosis

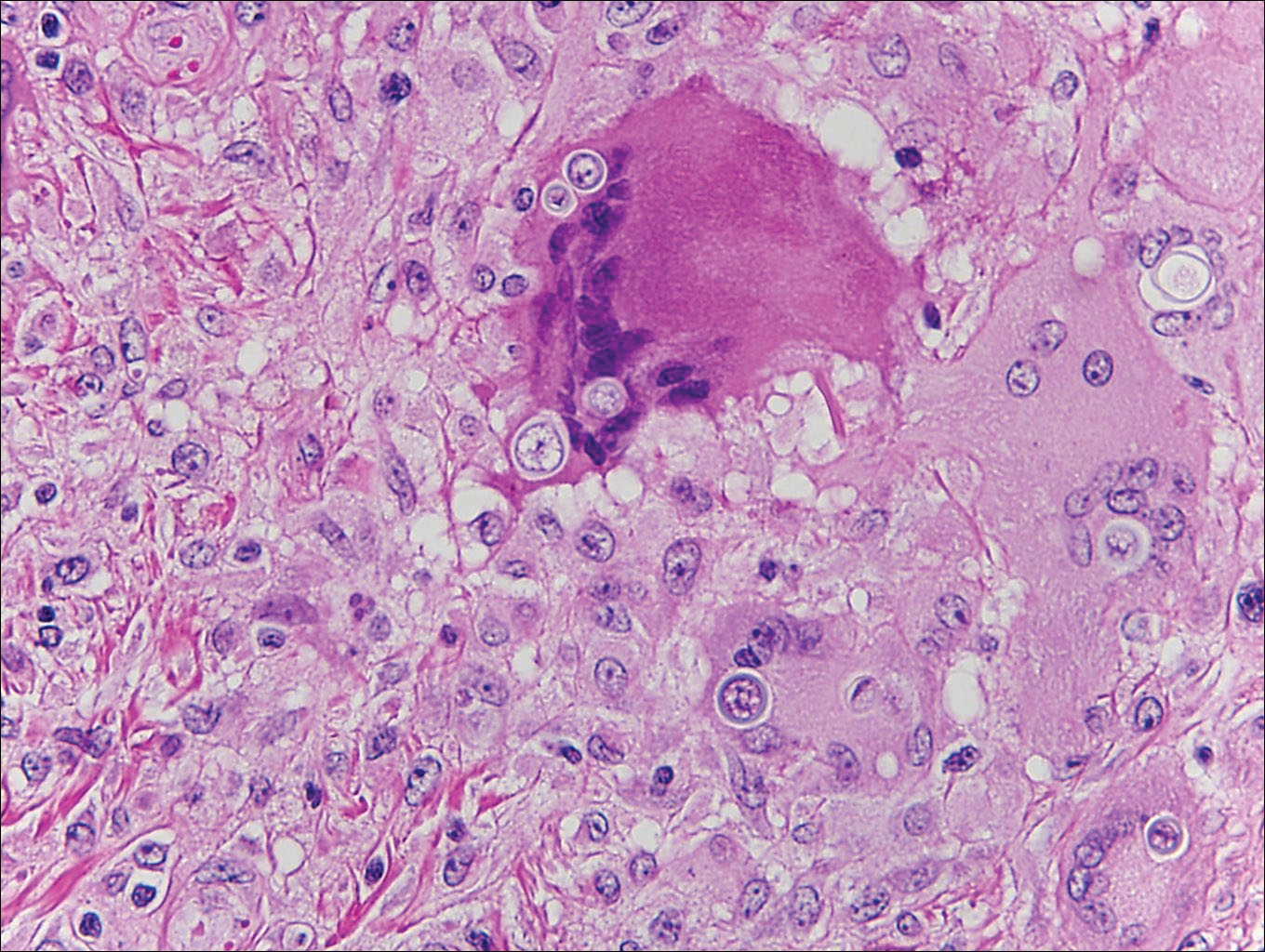

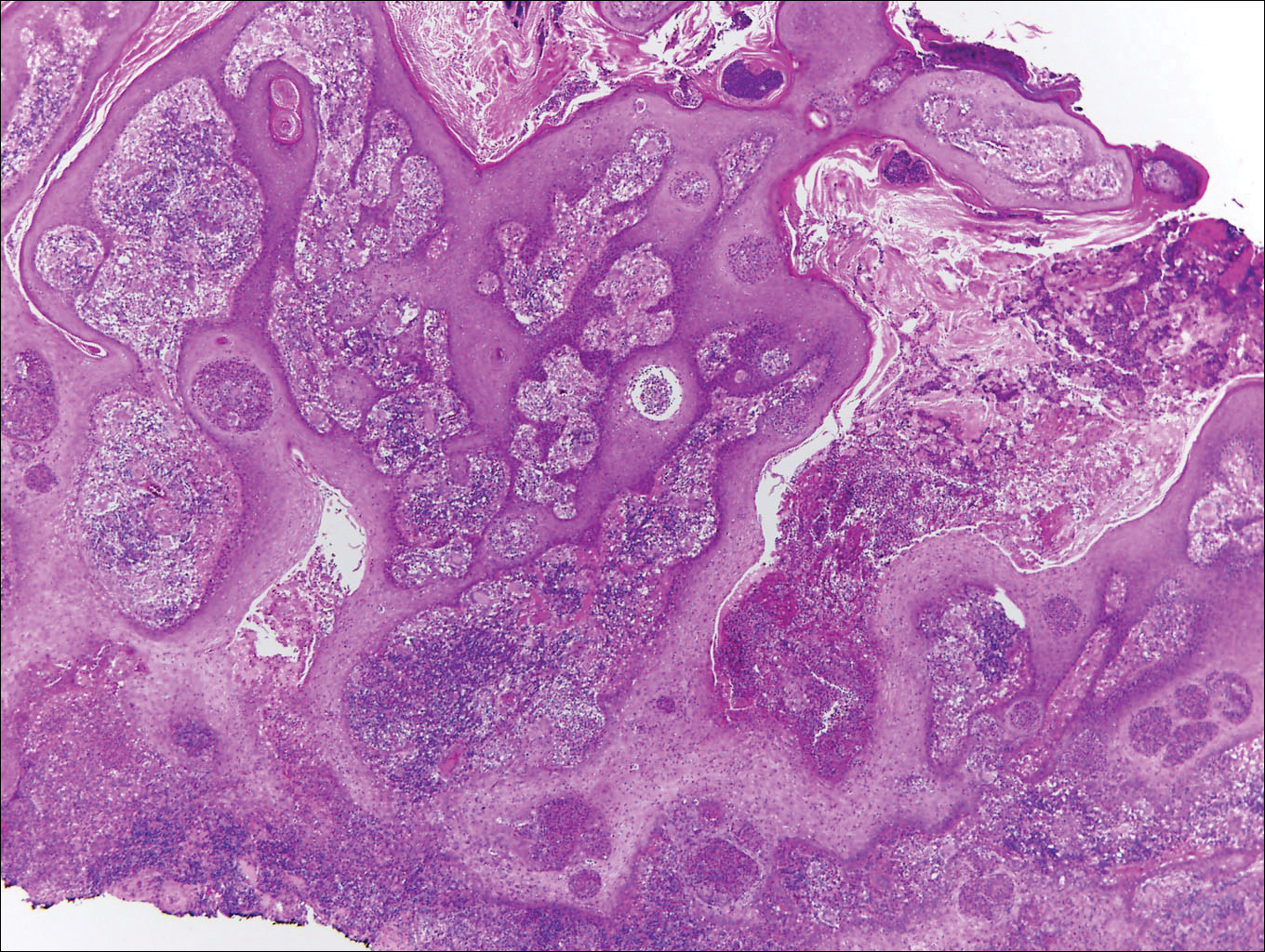

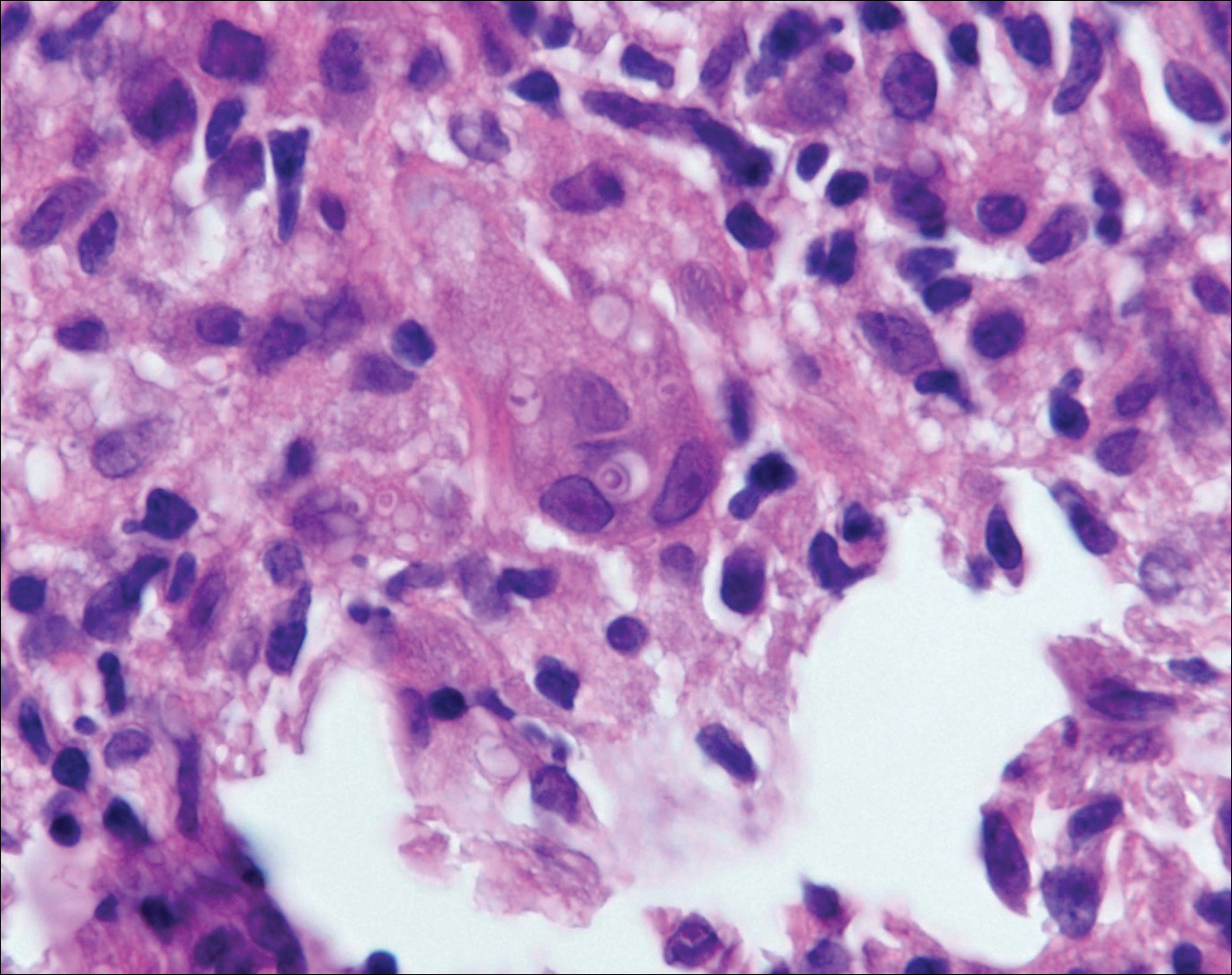

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

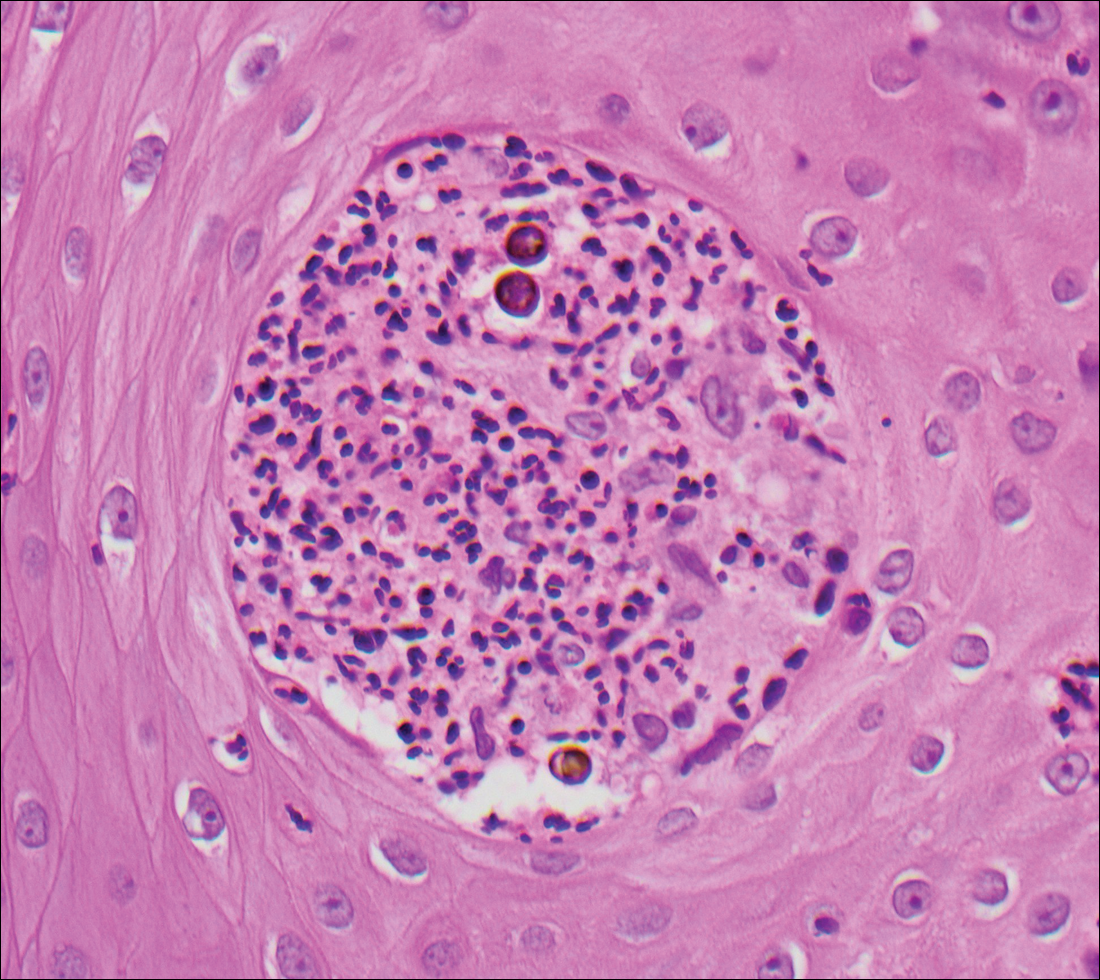

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic in the Midwestern and southeastern United States where it occurs environmentally in wood and soil. Unlike many fungal infections, blastomycosis most often develops in immunocompetent hosts. Infection is usually acquired via inhalation,1 and cutaneous disease typically is secondary to pulmonary infection. Although not common, traumatic inoculation also can cause cutaneous blastomycosis. Skin lesions include crusted verrucous nodules and plaques with elevated borders.1,2 Histologic features include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 1), and a neutrophilic and granulomatous dermal infiltrate. Organisms often are found within histiocytes (quiz image) or small abscesses. The yeasts usually are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with a thick cell wall and occasionally display broad-based budding.

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora, and Rhinocladiella species,3 which are present in soil and vegetable debris in tropical and subtropical regions. Infection typically occurs in the foot or lower leg from traumatic inoculation, such as a thorn or splinter injury.2 Histologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis; and sclerotic (Medlar) bodies, which are 5 to 12 µm in diameter, round, brown, sometimes septate cells resembling copper pennies (Figure 2).2

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is found in soil in the southwestern United States. Infection most often occurs via inhalation of airborne arthrospores.2 Cutaneous lesions occasionally are observed following dissemination or rarely following primary inoculation injury. They may present as papules, nodules, pustules, plaques, and ulcers, with the face being the most commonly affected site.1 Histologically, coccidioidomycosis is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, suppurative and granulomatous dermatitis, and large spherules (up to 100 µm in diameter) containing numerous small endospores (Figure 3).

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus found in soil, fruit, and pigeon droppings throughout the world.2,3 The most common route of infection is via the respiratory tract. Systemic spread and central nervous system involvement may occur in immunocompromised hosts.2 Skin involvement is uncommon and may present on the head and neck with umbilicated papules, pustules, nodules, plaques, or ulcers. Histologically, Cryptococcus is a spherical yeast, often 4 to 20 µm in diameter. Replication is by narrow-based budding. A characteristic feature is a mucoid capsule, which retracts during processing, leaving a clear space around the yeast (Figure 4). When present, the mucoid capsule can be highlighted on mucicarmine or Alcian blue staining. Histologic variants of cryptococcosis include granulomatous (high host immune response), gelatinous (low host immune response), and suppurative types.3

Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which occurs in soil and bird and bat droppings, with exposure primarily via inhalation. Cutaneous histoplasmosis is almost always a feature of disseminated disease, which occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals.1 Skin lesions may present as macules, papules, indurated plaques, ulcers, purpura, panniculitis, and subcutaneous nodules.2 Histologically, there is a granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutis. Yeasts are small (2-4 µm in diameter) and are observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figure 5) where they appear as basophilic dots, sometimes surrounded by an artifactual clear space (pseudocapsule).2

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak A, Ko C. Requisites in Dermatology: General Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009.