User login

Inverse Distribution of Pink Macules and Patches

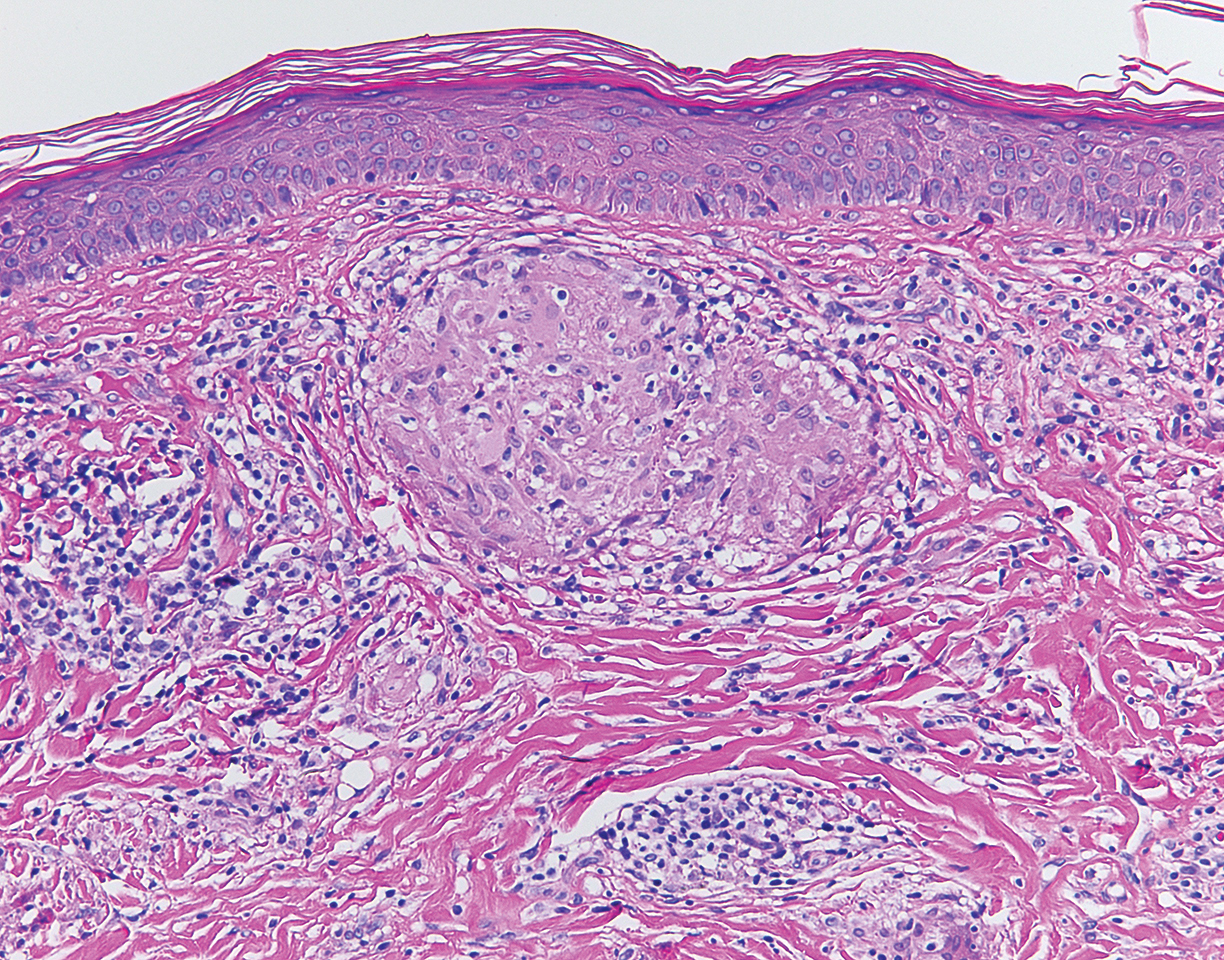

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

Punch biopsies from the right axilla (Figure) and right abdomen as well as a tangential biopsy from the left volar wrist papule showed an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate with focal palisading of histiocytes around central regions with collagen alteration and increased mucin. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli smear both were negative for organisms; these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of granuloma annulare (GA).

Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. It most commonly appears as asymptomatic, flesh-colored, pink or violaceous annular patches or thin plaques favoring the trunk and extremities. Granuloma annulare has many documented presentations including generalized, patch, subcutaneous, and perforating forms. It can present as macules, papules, nodules, patches, or plaques. Reported associations include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, solid organ tumors, systemic infection, and thyroid disease.1 Granuloma annulare can occur in any age group but is most common between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2

Diagnosis most often is made clinically and can be confirmed by histopathology. Histologic examination most commonly shows histiocytes within the dermis that palisade around a central area of mucin deposition between degenerating collagen fibers. The histiocytes of GA stain positive with vimentin, lysozyme, and CD68. The increased mucin stains with colloidal iron and Alcian blue. Multinucleated giant cells and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate also are commonly seen.3

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has a wide range of presentations but usually occurs as hyperpigmented plaques and patches with dermal atrophy. Psoriasis can present in an inverse distribution but will show epidermal changes including scale. Sarcoidosis presents as multiple erythematous plaques and papules and also can be accompanied by erythema nodosum. Tinea corporis likely would have resolved with antifungal treatment.

Many different treatments have been described as effective, including cryosurgery, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, immune modulators, phototherapy, and oral corticosteroids.1 We started our patient on triple-antibiotic therapy with rifampin 600 mg, minocycline 100 mg, and ofloxacin 400 mg all once monthly for 6 months, which has been shown to be efficacious in treating GA.4 The patient returned for follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation. At that time, she had faint pink patches on the waist and medial upper thighs, and the axillary lesions had cleared. In the interim, she developed more classic GA lesions—pink to violaceous smooth papules with no overlying epidermal changes—on the volar wrists and dorsal feet. These lesions were asymptomatic, and she currently is not undergoing any further treatment.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. The granulomatous reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016:198-203.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treated with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:787-789.

A 73-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic progressive rash on the left wrist, waist, groin, and inner thighs of 2 months’ duration. Her primary care provider prescribed clotrimazole and fluconazole with no improvement. Review of systems was negative. Medications included omeprazole, candesartan hydrochlorothiazide, potassium chloride, and levothyroxine. Physical examination revealed many scattered, pink to violaceous macules and patches in the axillae (sparing the vaults) and inguinal folds as well as on the waist and medial upper thighs. The lesions were without scale or other epidermal change. She also had a pink papule on the left volar wrist. A Wood lamp examination was unremarkable, and punch biopsies were performed.

Coalescing Papules on Bilateral Mastectomy Scars

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

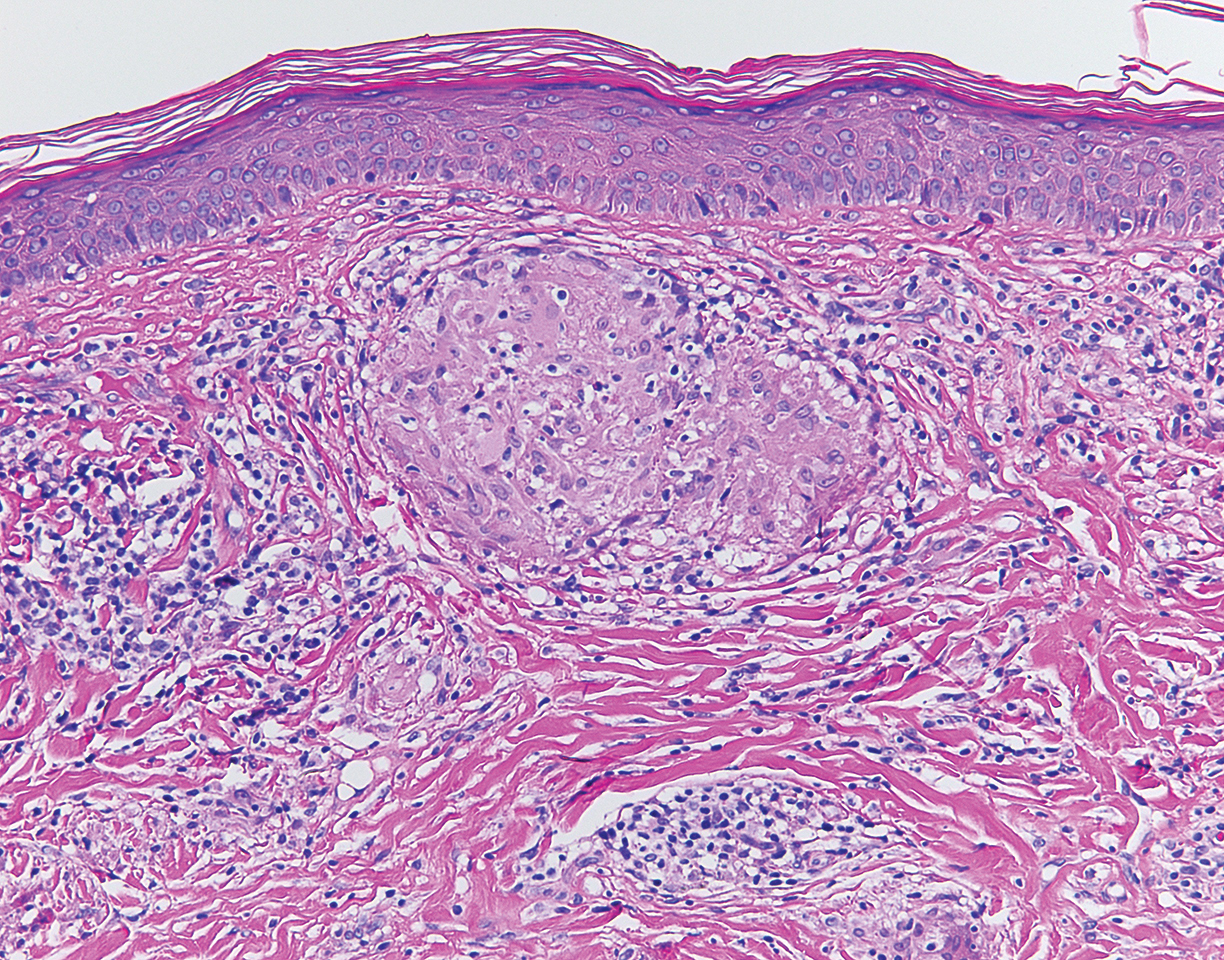

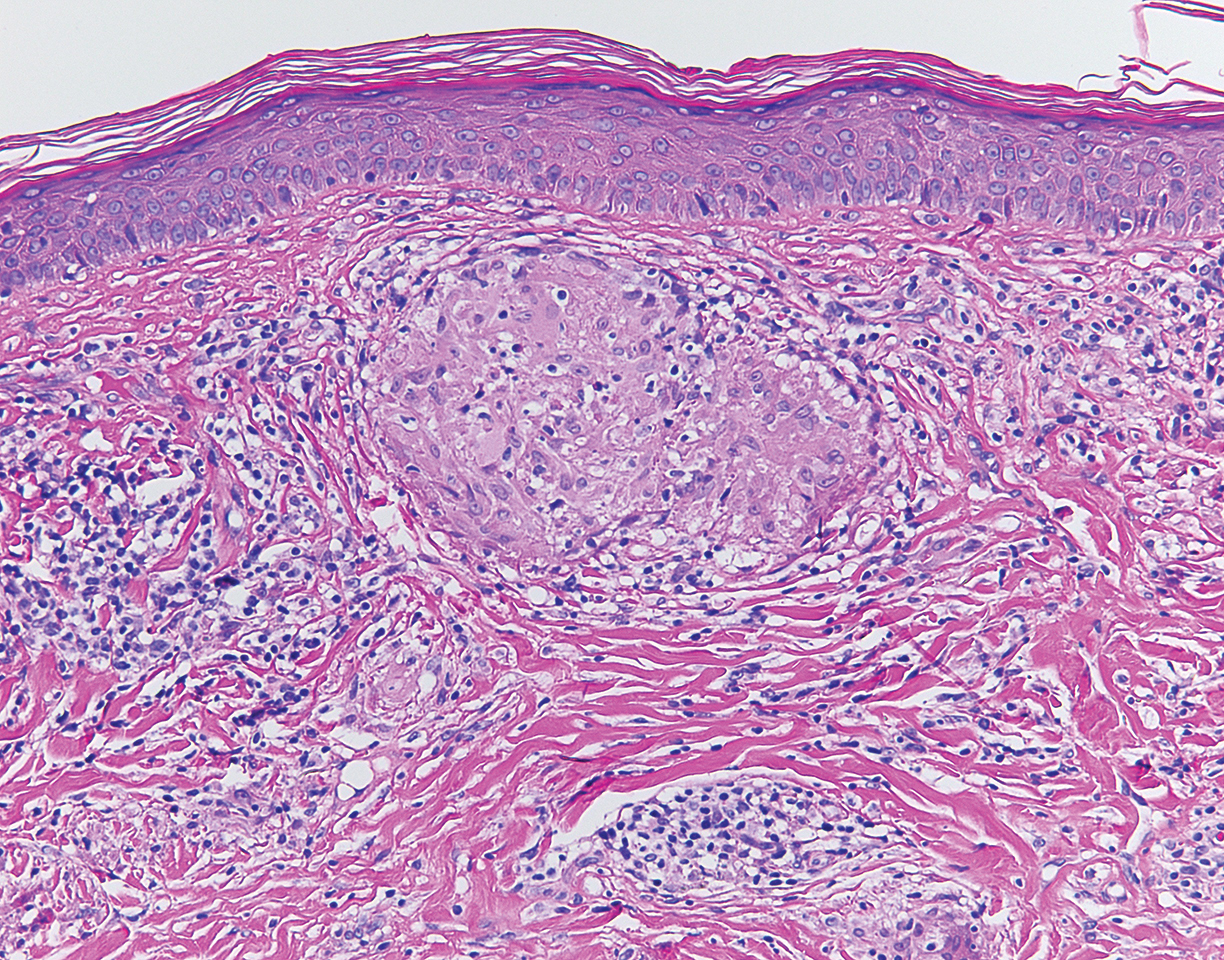

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

A 57-year-old woman with triple-negative ductal breast cancer presented with a mildly pruritic rash on bilateral mastectomy scars of 3 to 4 months' duration. More than a year prior to presentation, she was diagnosed with breast cancer and treated with a bilateral mastectomy and chemotherapy. On physical examination, faintly yellow, slightly indurated, coalescing papules with red rims were present on the bilateral mastectomy scars, with the scar on the left side appearing worse than the right. She previously had not sought treatment.