User login

Subungual Hemorrhage From an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

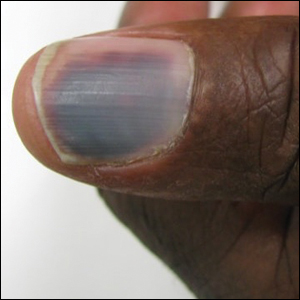

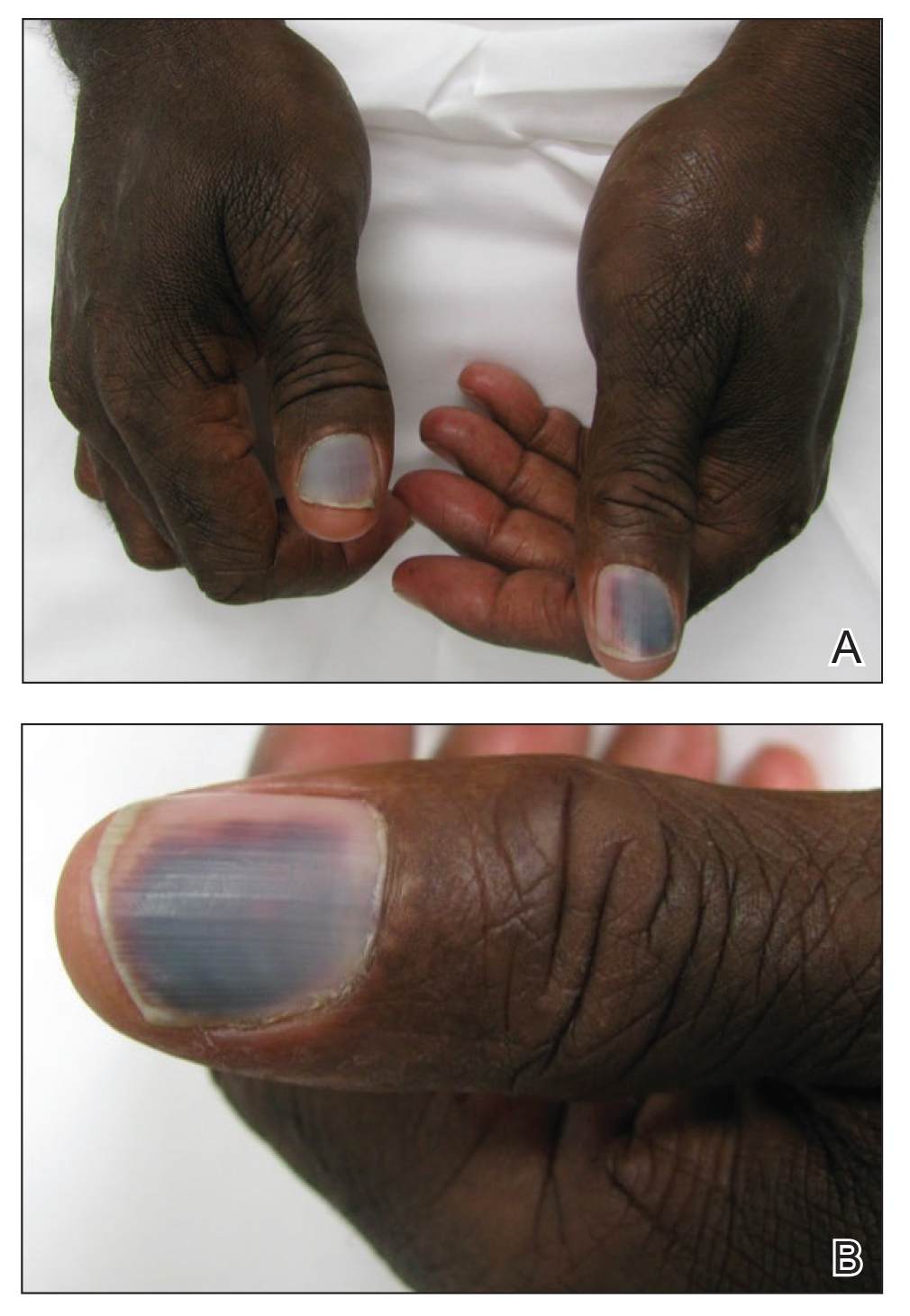

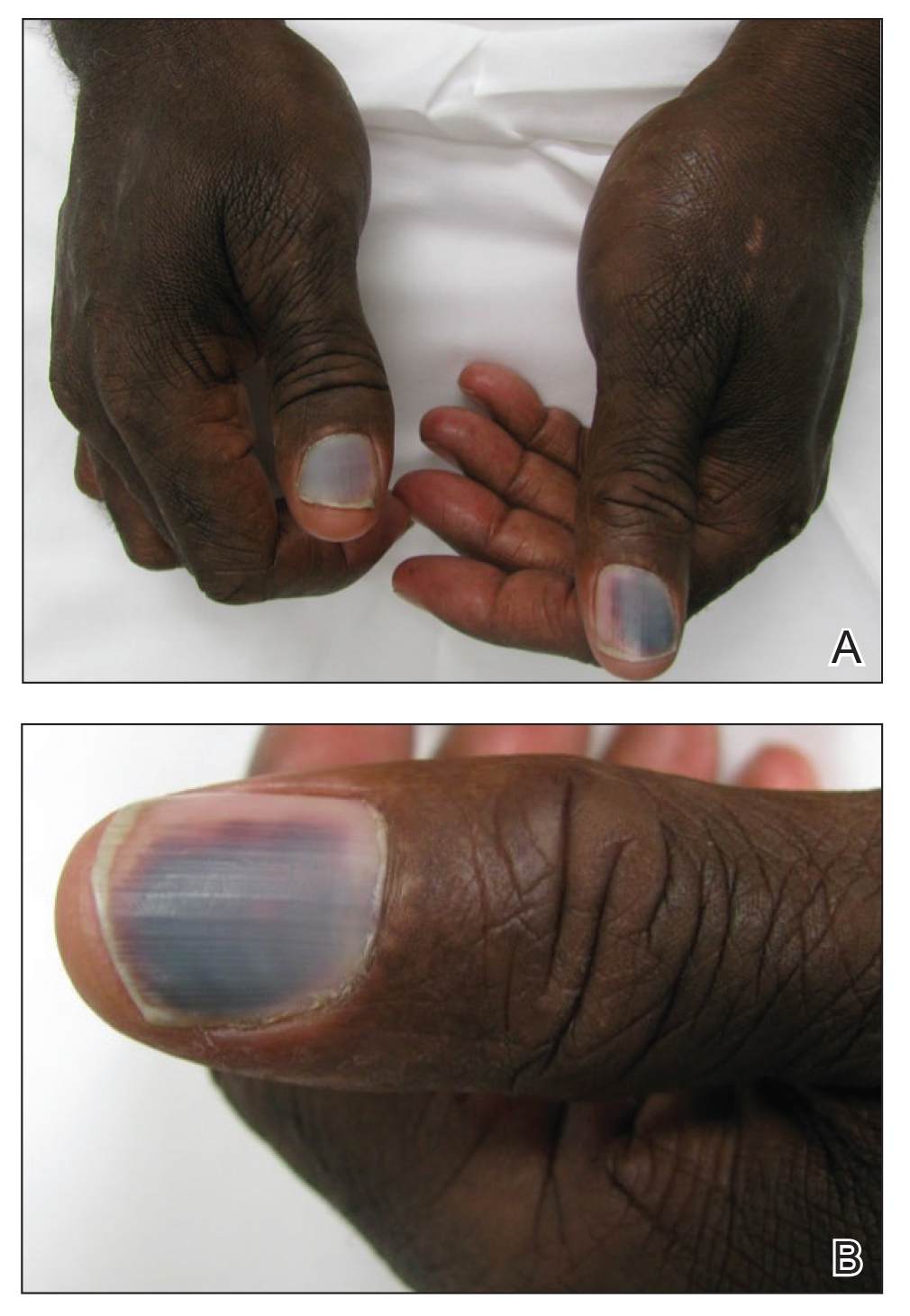

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

Practice Points

- Subungual hemorrhage is a potential adverse side effect of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors.

- Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition may lead to enhanced fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate as well as a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin, predisposing patients to nail toxicity.

Perifollicular Papules on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

A 40-year-old black man presented with numerous perifollicular flesh-colored papules on the back, chest, abdomen, and proximal aspect of the arms of 6 years' duration. He described these lesions as persistent, nonpainful, and nonpruritic. He previously was treated with an unknown cream without any benefit. These lesions were cosmetically bothersome.