User login

Chronic Retiform Purpura of the Abdomen and Thighs: A Fatal Case of Intravascular Large Cell Lymphoma

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

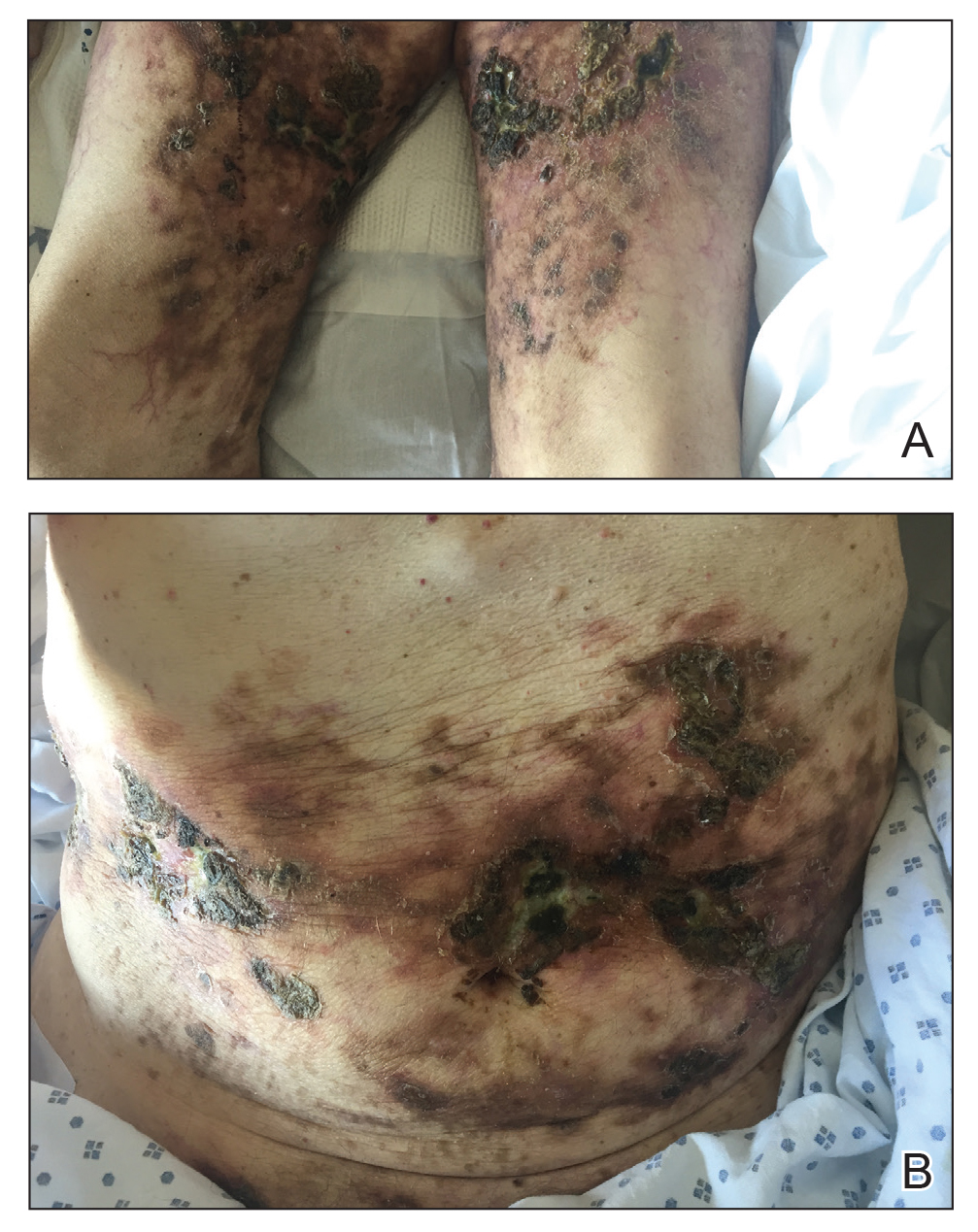

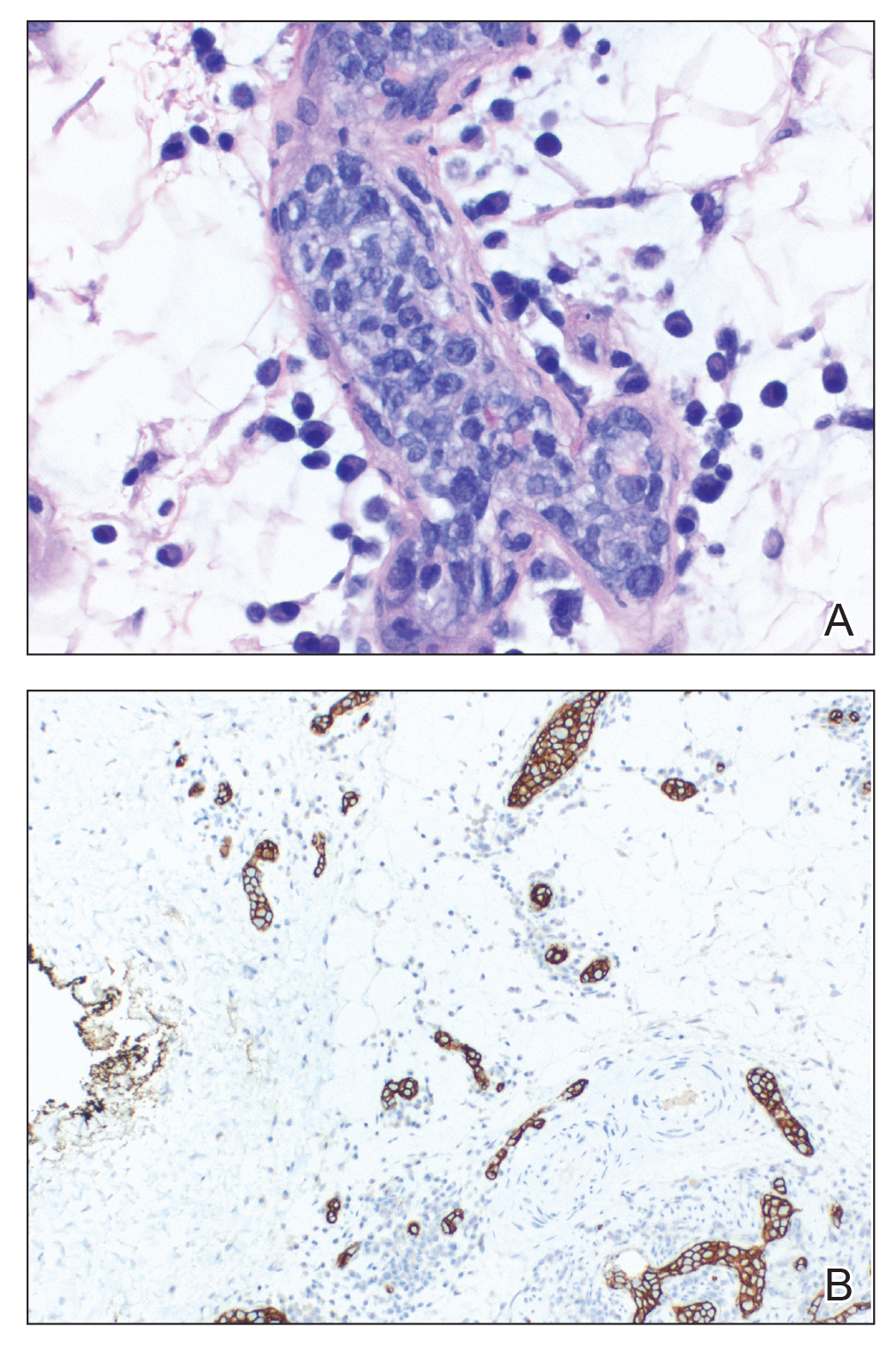

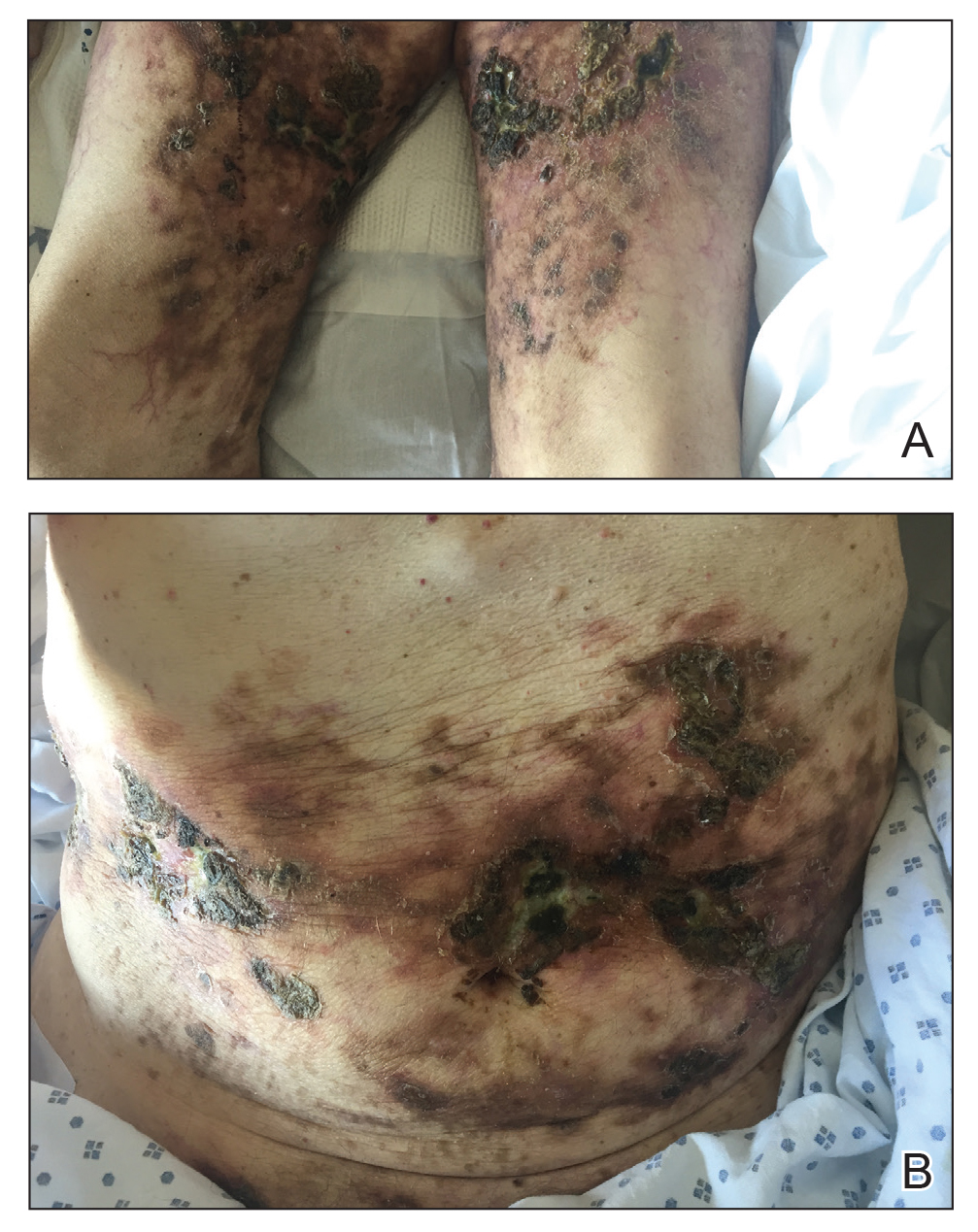

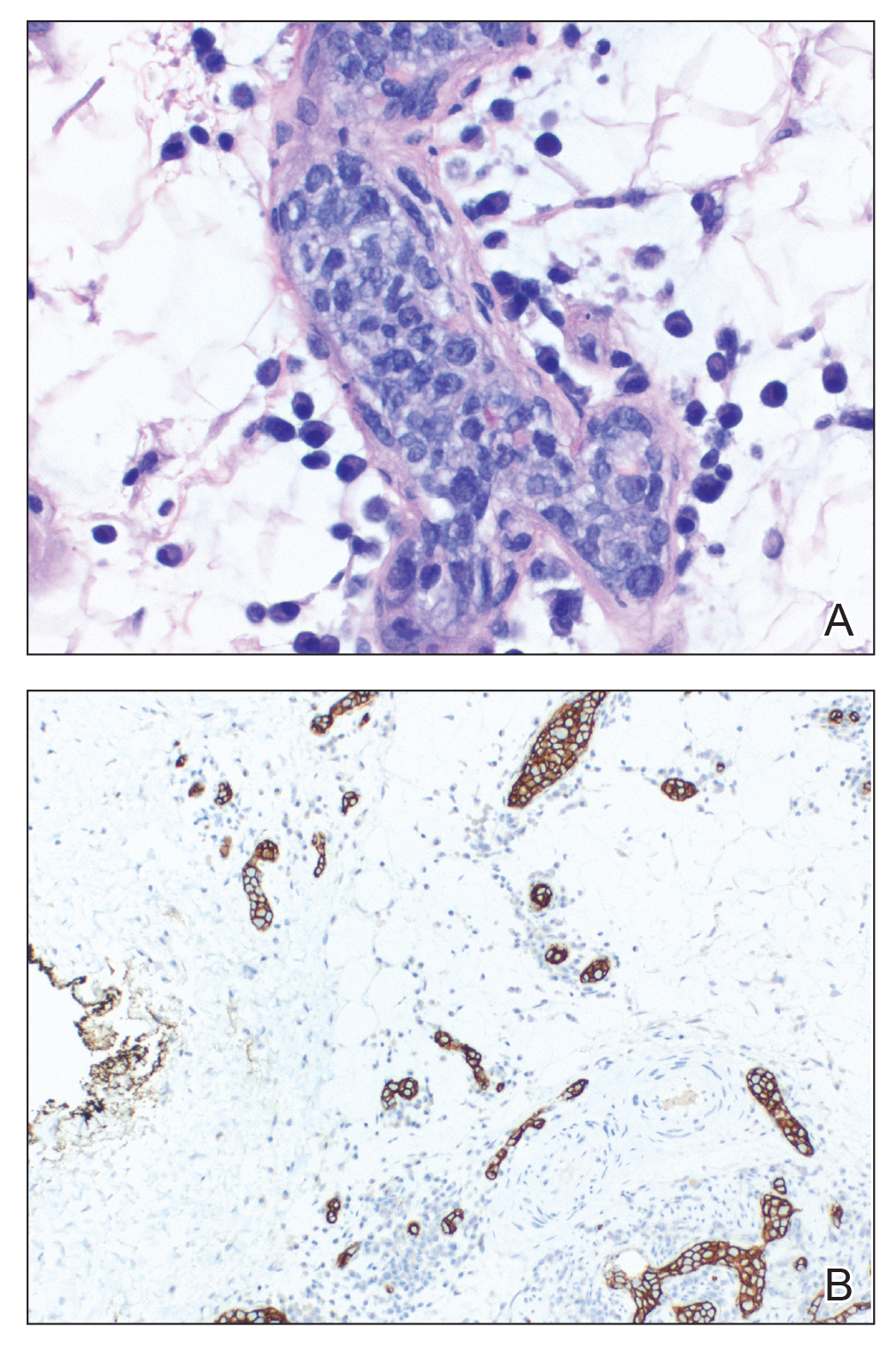

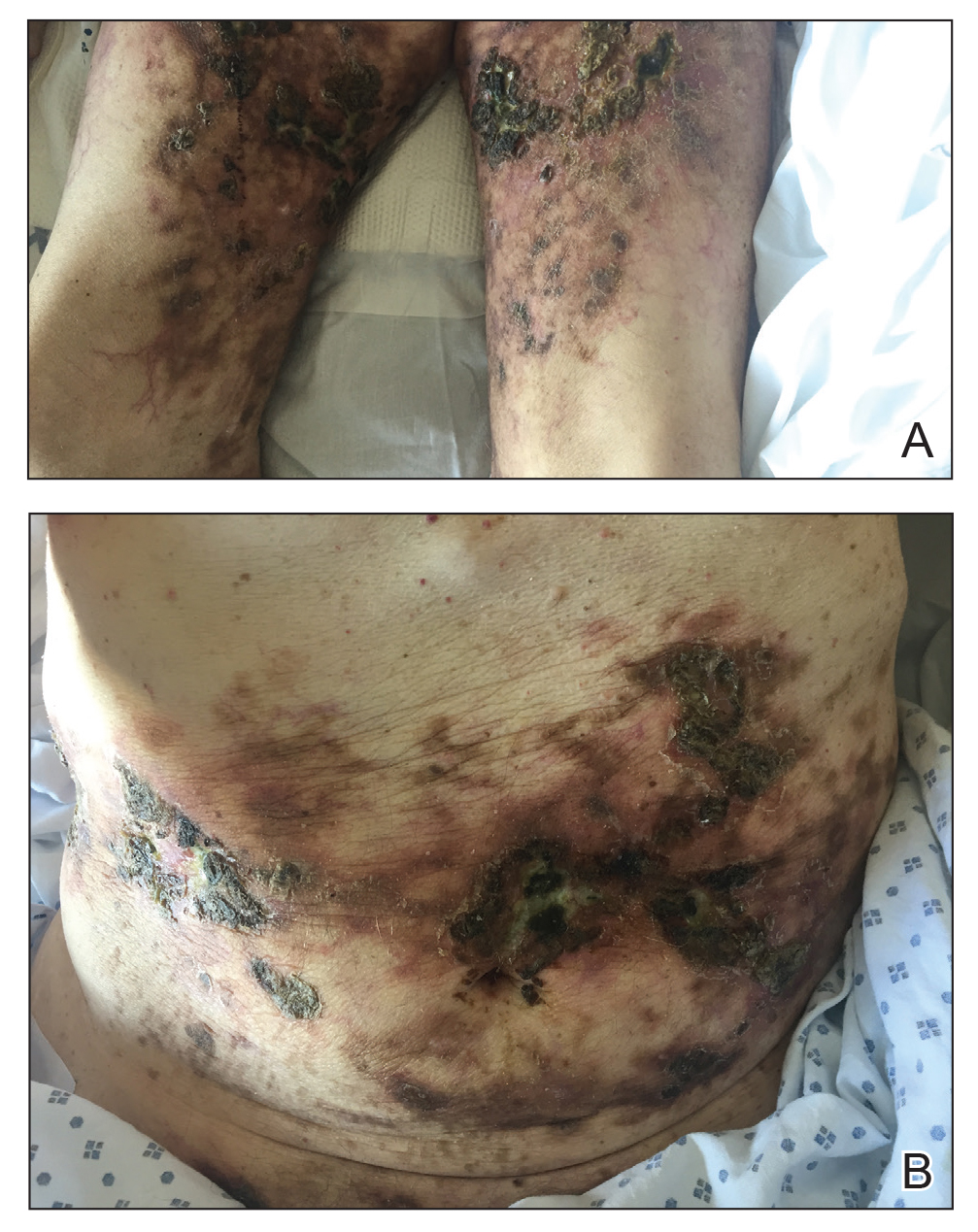

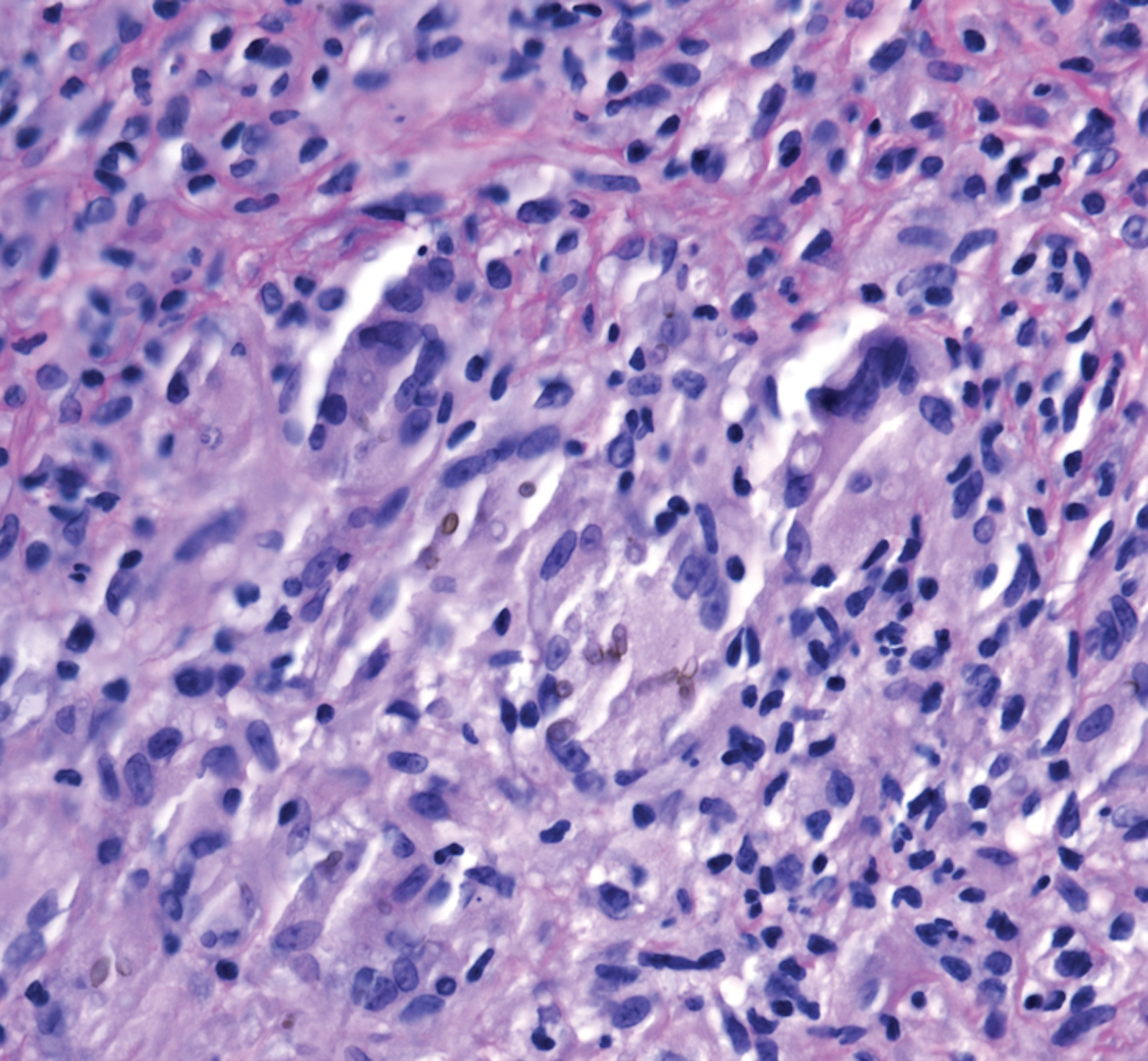

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

Practice Points

- Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a life-threatening malignancy that can present with retiform purpura and other symptoms of vascular occlusion.

- The diagnosis of ILCL can be challenging because of the presence of distractors, and multiple biopsies may be required to establish pathology.

Recurrent Cutaneous Exophiala Phaeohyphomycosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

To the Editor:

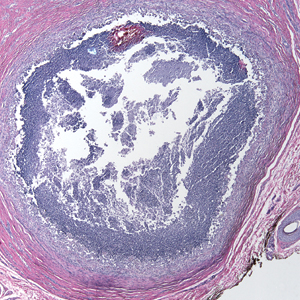

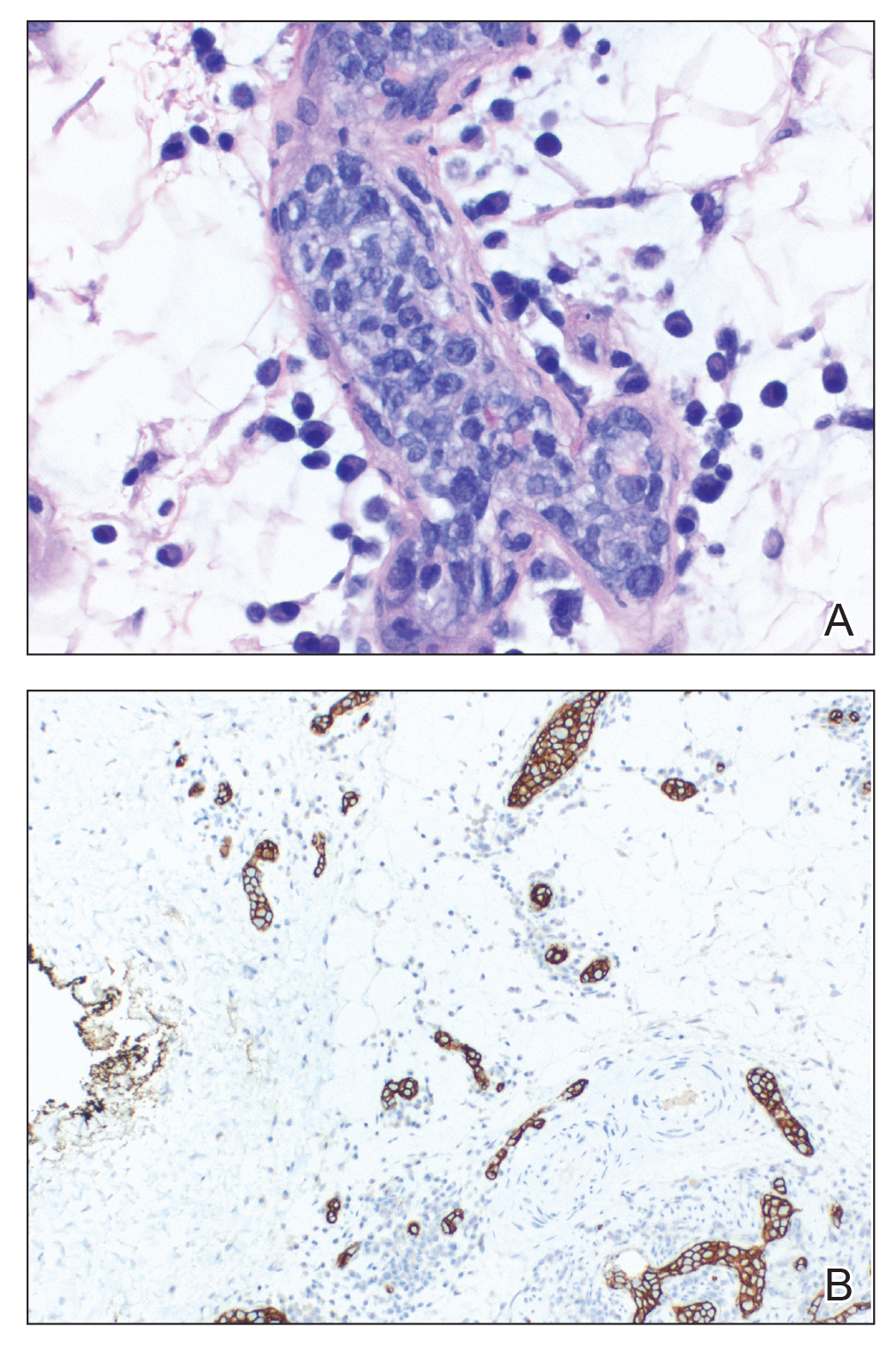

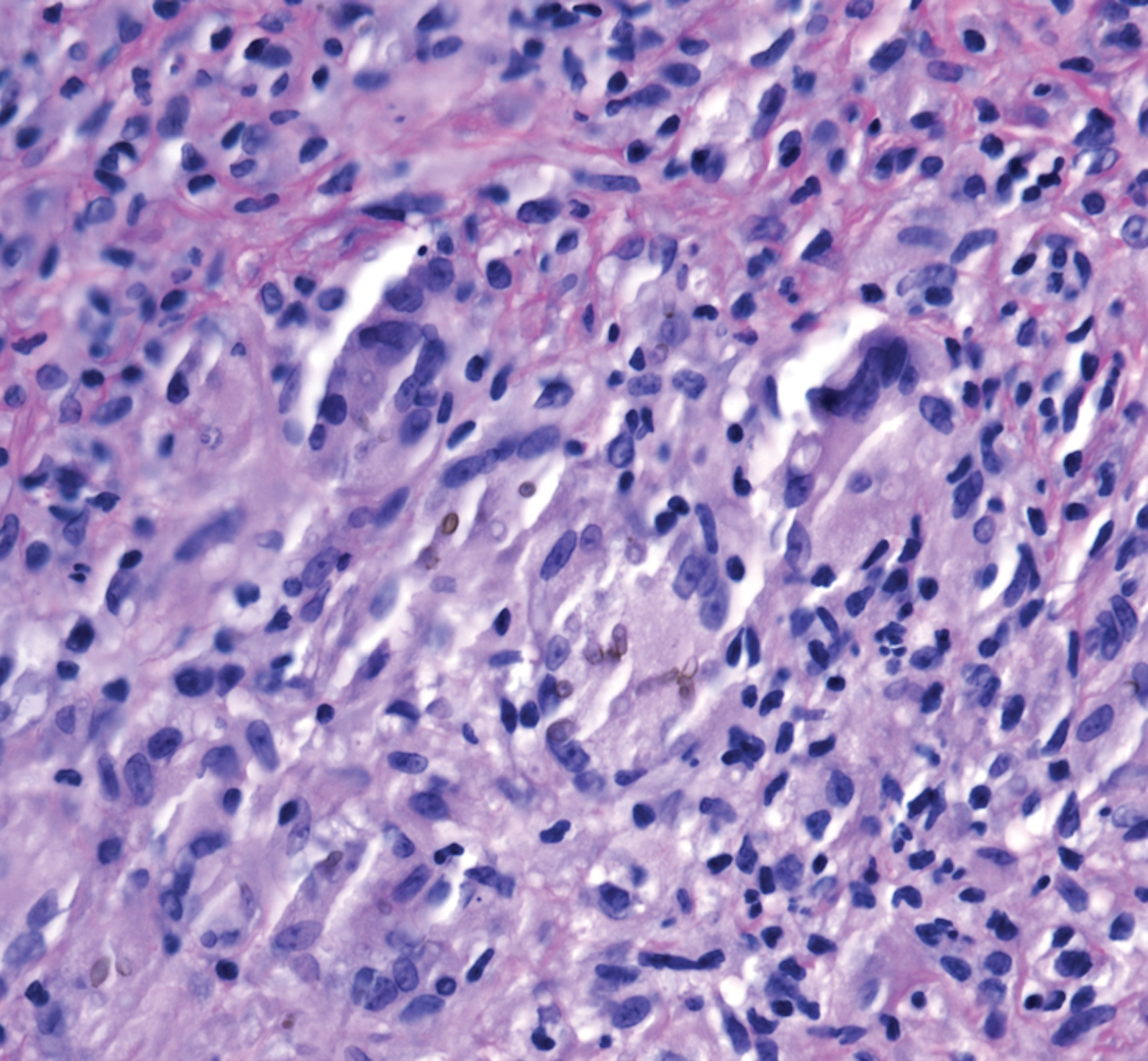

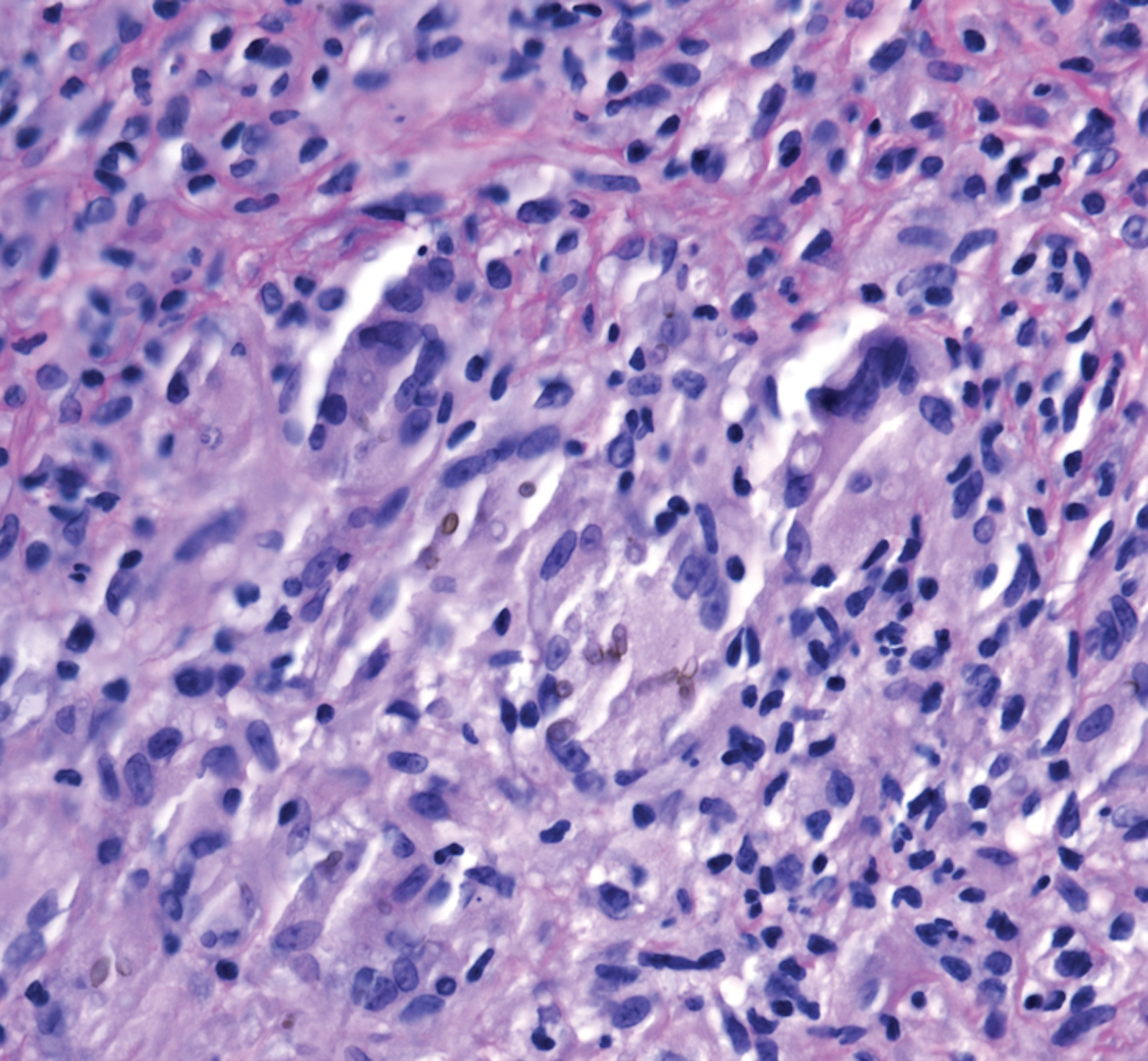

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

Practice Points

- Phaeohyphomycosis is an infection with dematiaceous fungi that most commonly affects immunosuppressed patients.

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis may present with nodulocystic lesions that recur over the course of years.

- Tissue fungal culture should be obtained when the diagnosis is suspected, as the risk for dissemination is related to the culprit organism.

- Surgical excision with close follow-up may be an appropriate management strategy for patients on immunosuppressive medications to avoid interactions with azole therapy.