User login

Chronic Retiform Purpura of the Abdomen and Thighs: A Fatal Case of Intravascular Large Cell Lymphoma

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

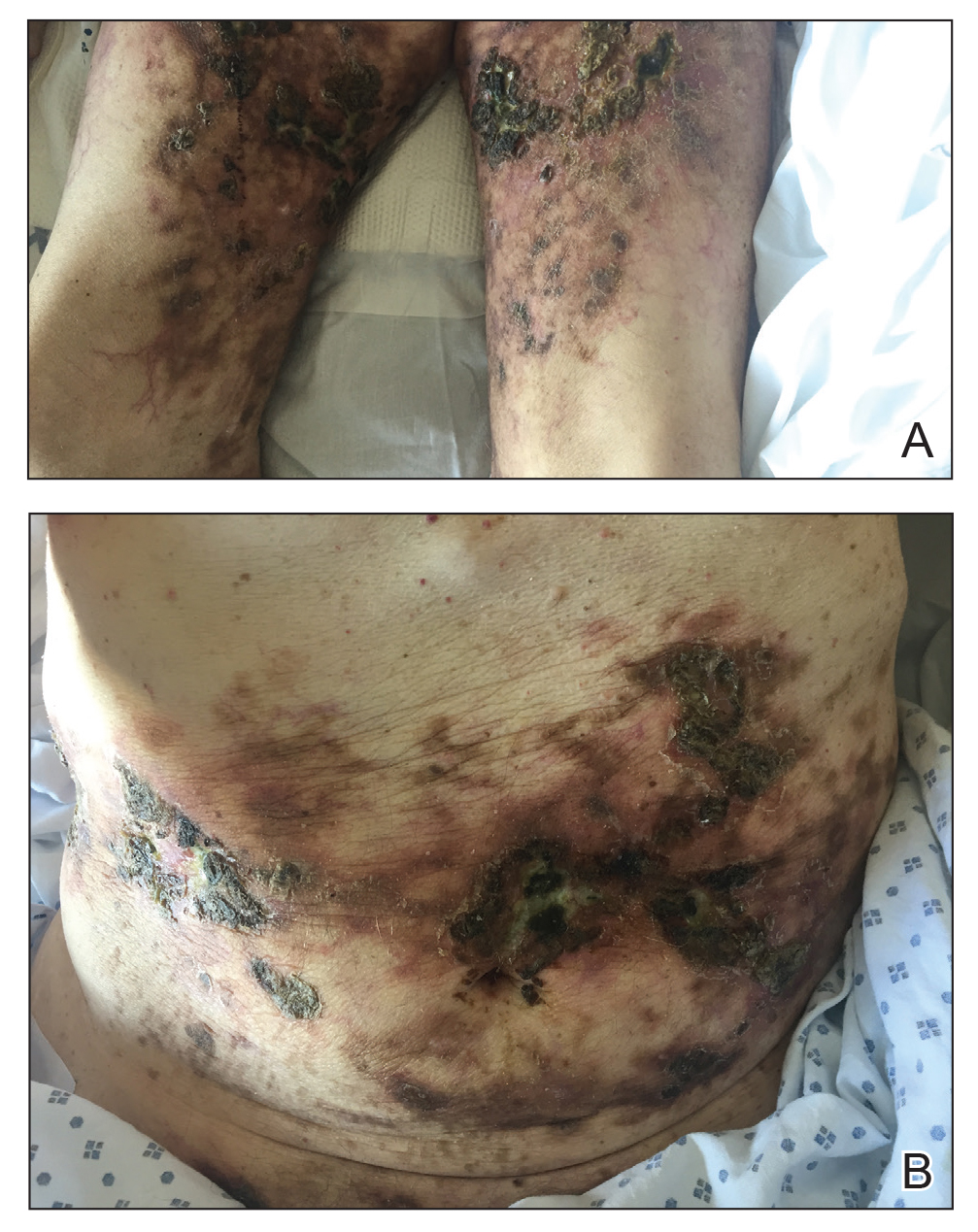

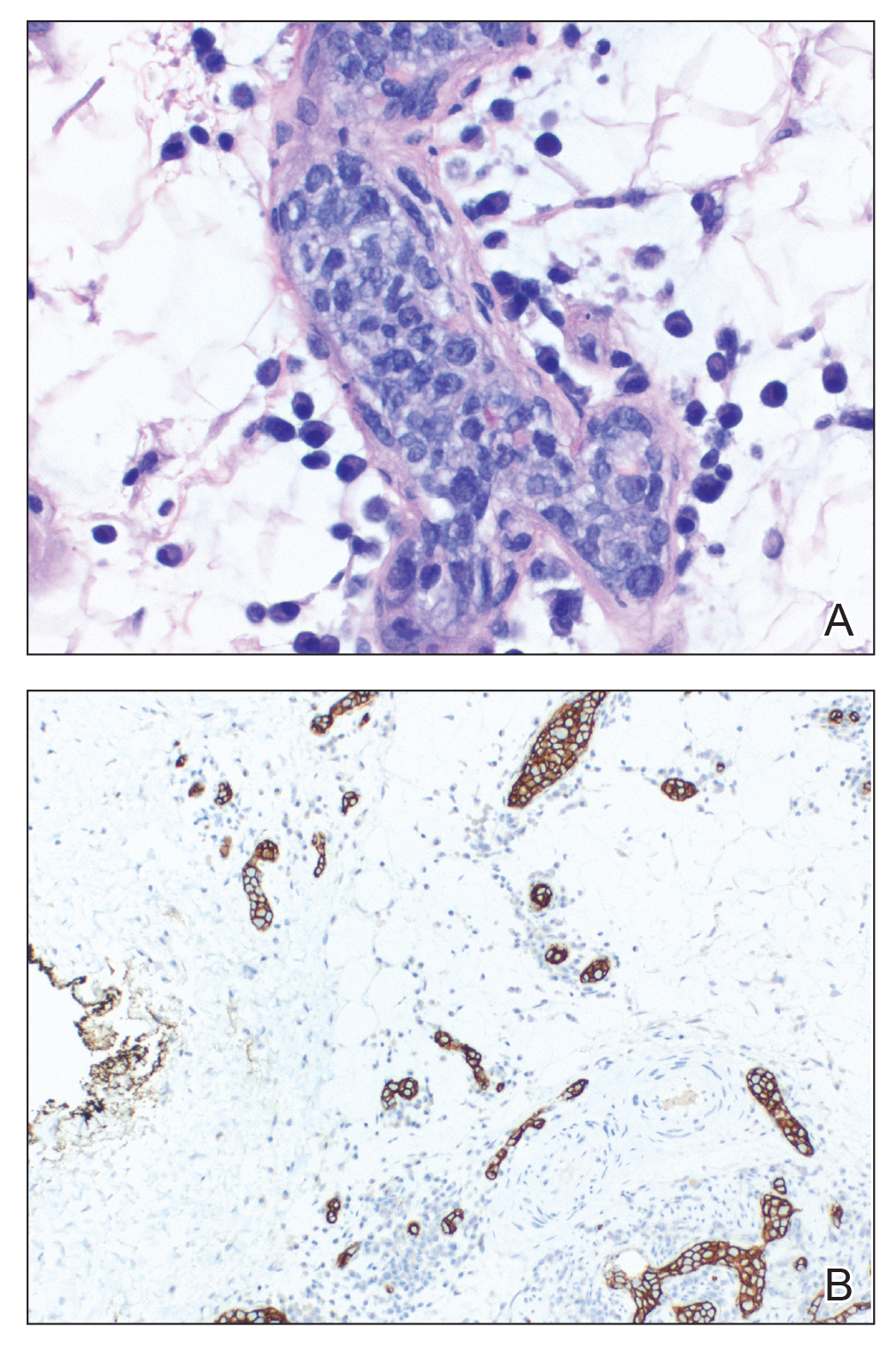

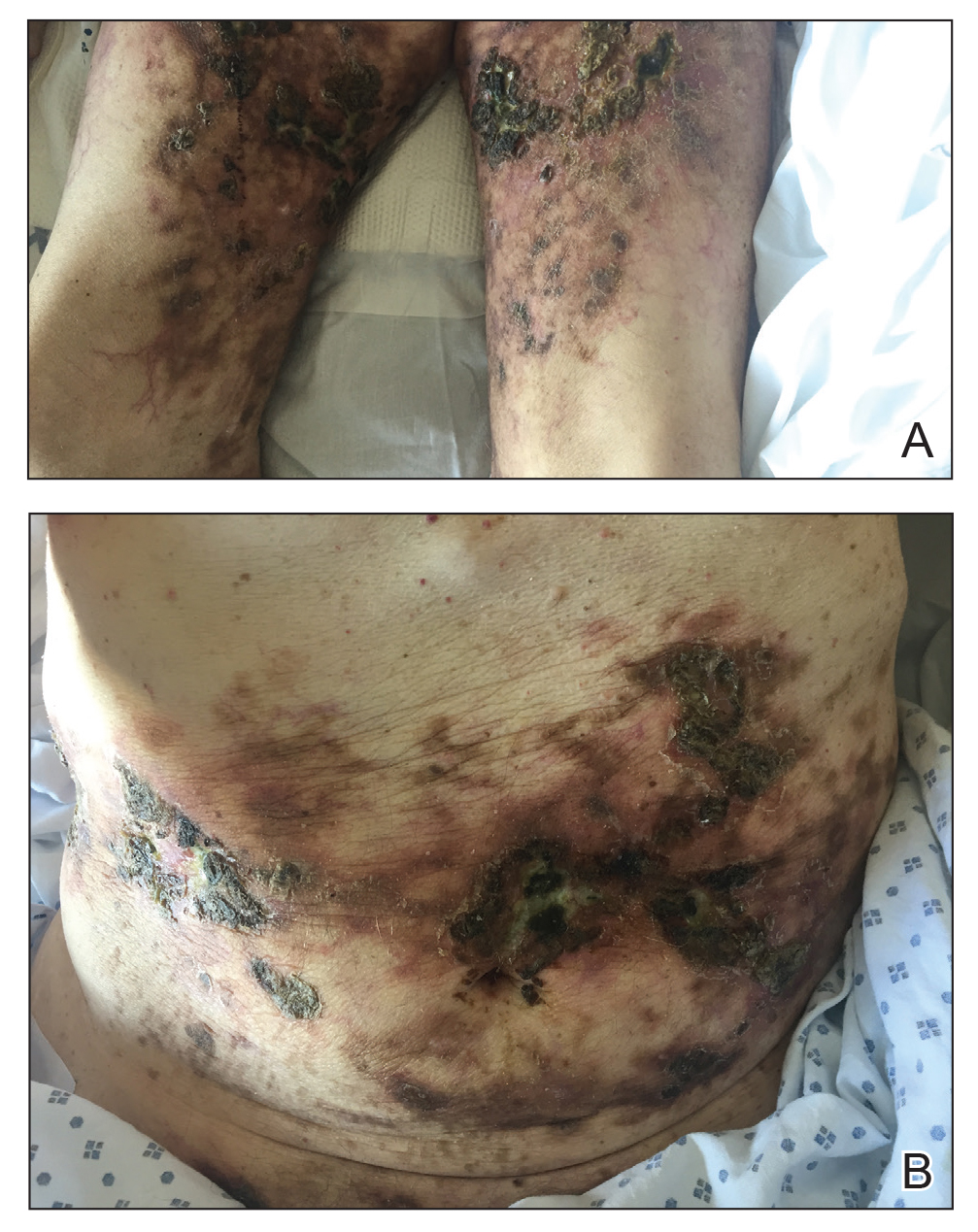

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

Practice Points

- Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a life-threatening malignancy that can present with retiform purpura and other symptoms of vascular occlusion.

- The diagnosis of ILCL can be challenging because of the presence of distractors, and multiple biopsies may be required to establish pathology.

Purpuric Lesions of the Scalp, Axillae, and Groin of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

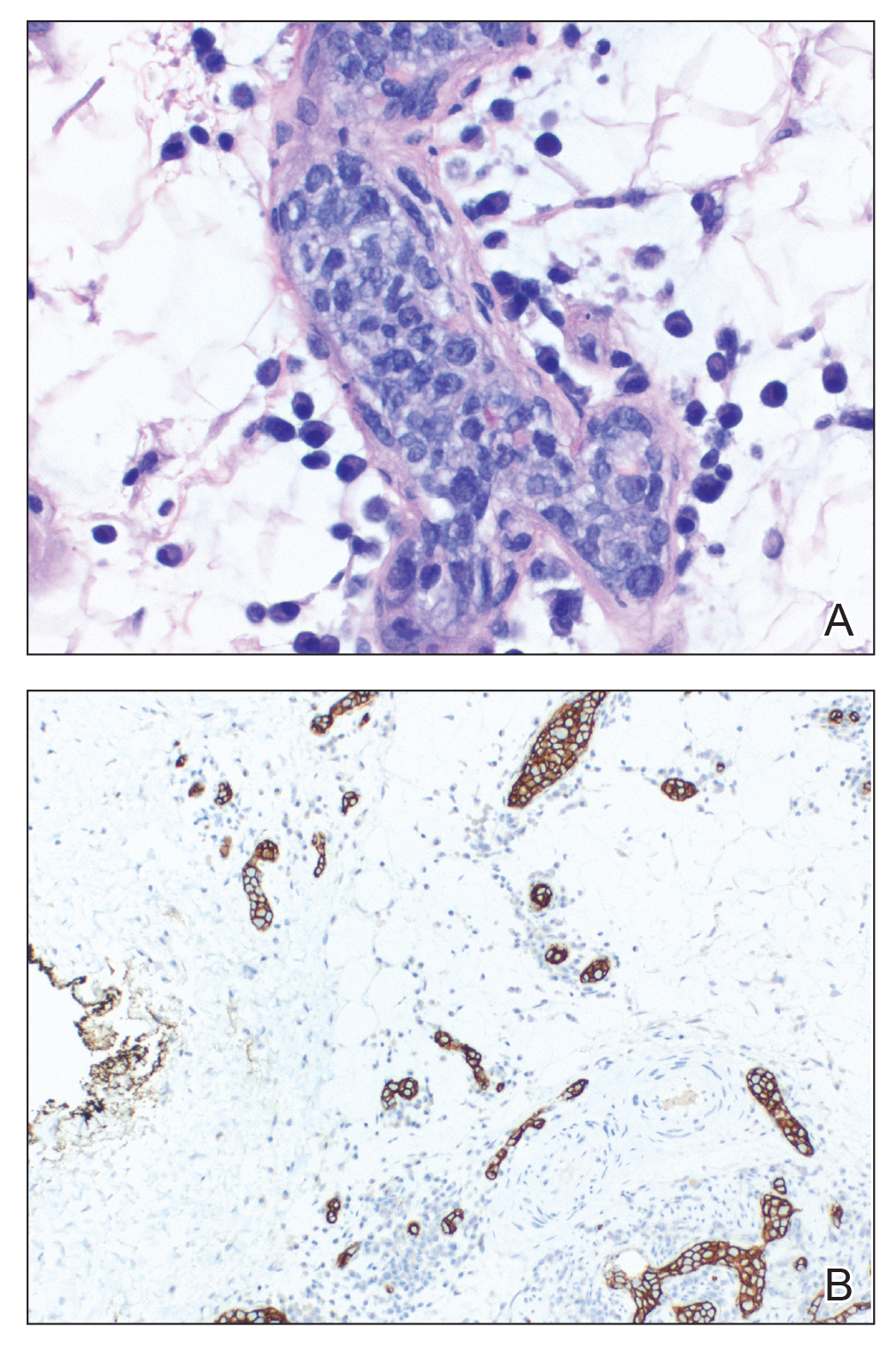

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

The Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can affect any organ, most commonly the skin and bones. It typically develops in children aged 1 to 3 years, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.1 Skin manifestations include purpuric papules, pustules, vesicles, erosions, and fissuring distributed predominantly on the scalp and flexural sites. Mucosal sites, particularly the oral mucosa, may be involved and usually present as erosions associated with underlying bone lesions.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recalcitrant diaper dermatitis in an infant, especially when there is purpura and erosions, as seen in our patient. Common conditions in infants such as cutaneous candidiasis (intense erythema with superficial erosions, peripheral scale and satellite pustules on flexural areas, potassium hydroxide microscopy revealing yeast forms and pseudohyphae) and seborrheic dermatitis (well-defined pink to red, moist, and often scaly patches favoring the folds) may be distinguished clinically from Hailey-Hailey disease (malodorous plaques with fissures and erosions favoring the folds), which is rare in infancy, and acrodermatitis enteropathica (erythema and erosions with scale-crust and desquamation on periorificial, acral, and intertriginous skin).

Histopathologic evaluation is instrumental in diagnosing the skin lesions of LCH. Further evaluation for systemic involvement is necessary once the diagnosis is made. Skin biopsy of the scalp and right inguinal fold revealed a wedge-shaped infiltrate of histiocytes with slightly folded nuclear contours in our patient (Figure 1). CD1a (Figure 2) and S-100 stains were markedly positive, which is characteristic of LCH. Complete blood cell count, renal function, liver function, urinalysis, and flow cytometry results were within reference range. A skeletal survey and echocardiogram were unremarkable; however, mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal ultrasonography.

Treatment of LCH varies based on the extent of organ involvement. For isolated cutaneous disease, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, phototherapy, and thalidomide may be employed.2 Multisystem disease requires chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastine and prednisone.2,3 Because more than half of patients with LCH have oncogenic BRAF V600E mutations,4 vemurafenib may have a therapeutic role in treatment. Rare case reports have documented disease response in patients with LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease.5,6

Prognosis varies based on age and extent of systemic involvement. Children younger than 2 years with multiorgan involvement have a poor prognosis (35%-55% mortality rate) compared to older children without hematopoietic, hepatosplenic, or lung involvement (100% survival rate). Additionally, response to treatment affects prognosis, as there is a 66% mortality rate in those who do not respond to treatment after 6 weeks.3 Long-term sequelae of LCH include endocrine dysfunction (ie, diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiencies), hearing impairment, orthopedic impairment, and neuropsychological disease; thus, multidisciplinary care often is neccessary.7

Given the multisystem involvement in our patient, he was treated with vinblastine, 6-mercaptopurine, and prednisolone with only partial and transient disease response. He was then treated with clofarabine with dramatic resolution of the mediastinal mass on follow-up positron emission tomography. The cutaneous lesions persisted and were managed with topical corticosteroids.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years [published online October 25, 2012]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Gadner H, Grois N, Arico M, et al; Histiocyte Society. A randomized trial of treatment for multisystem Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:728-734.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923.

- Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495-1500.

- Charles J, Beani JC, Fiandrino G, et al. Major response to vemurafenib in patient with severe cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring BRAF V600E mutation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E97-E99.

- Martin A, Macmillan S, Murphy D, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 23 years' paediatric experience highlights severe long-term sequelae. Scott Med J. 2014;59:149-157.

A 7-month-old boy admitted to the hospital with new-onset respiratory stridor was found to have a rash of the scalp, axillae, and groin of 1 month's duration that was unresponsive to treatment with mineral oil. Bronchoscopy revealed tracheal compression, and urgent magnetic resonance imaging of the chest demonstrated an anterior mediastinal mass. Prior to presentation, the patient was otherwise healthy with normal growth and development. On physical examination, scattered red-brown and purpuric papules with hemorrhagic crust were noted on the scalp. There were well-defined pink erosive patches and purpuric papules in the inguinal folds bilaterally and similar erosive patches in the axillae. Numerous punched out ulcerations were noted on the lower gingiva. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. The hands, feet, penis, scrotum, and perianal area were spared. Biopsies of the skin and mediastinal mass were performed.