User login

Lipoma of the Tendon Sheath in the Fourth Extensor Compartment of the Hand

Lipomas are relatively common benign tumors composed primarily of adipose tissue. They can occur anywhere on the body and are seen often in the hands and forearm. Typically localized to the subcutaneous fat layer, a lipoma is rarely associated with a tendon sheath or tendon compartment.1,2 When this uncommon event occurs, the lipoma is appropriately labeled lipoma of the tendon sheath.

While there are numerous case reports of lipomas of the tendon sheath occurring in association with tendons in the lower extremity, there are no reports, to our knowledge, of their occurrence in the extensor compartments of the hand.1 We report a rare case of lipoma of the tendon sheath localized to the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand, which was successfully treated with surgical excision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 33-year-old right hand–dominant waitress presented with a chief complaint of a painful, slowly enlarging right dorsal hand mass of 5 years’ duration. The mass was particularly bothersome with activities involving grip and finger extension. Physical examination revealed a mobile, rubbery mass on the dorsum of the hand that moved slightly with fist formation. There were no signs of neurovascular compromise. She had normal hand and wrist range of motion.

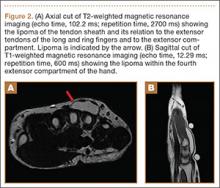

Plain radiographs were unremarkable (Figures 1A, 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast revealed a 4×2-cm mass consistent with a diagnosis of lipoma. However, it was unique in that it appeared to extend from the long- and ring-finger extensor tendon sheaths in the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand (Figures 2A, 2B) and was deemed a lipoma of the tendon sheath. Representative MRI also showed the lipoma to be present within the fourth extensor compartment of the hand (Figure 2B). Because of the mass’s increasing size and interference with hand function, the patient elected to have the mass excised.

Surgical Technique

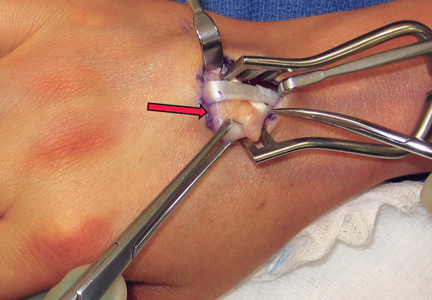

A 3-cm longitudinal incision was made over the dorsum of the hand centered directly over the mass. Dissection was carried through the subcutaneous tissue to the distal margin of the extensor retinaculum. The fourth dorsal compartment was entered and the tendons of the fourth extensor compartment were identified. Immediately beneath the extensor tendons to the long and ring fingers was a yellow, rubbery mass consistent with lipoma (Figure 3). This mass was strongly adherent to the underlying tendons and had to be dissected carefully with tenotomy scissors. Fortunately, the mass could be excised as a single unit (Figure 4). It was sent to the pathology department for histologic examination, which revealed mature adipose tissue and confirmed the diagnosis of lipoma. The wound was closed with absorbable suture, and a soft, sterile dressing was applied.

Postoperative Care

The patient was seen in follow-up 2 weeks later for routine evaluation. She had an intact wound with minimal hand pain, and full wrist and hand range of motion. She returned to work as a waitress approximately 3 weeks after surgery without difficulty. At her 6-week postoperative mark, she had a pain-free wrist with a well-healed incision and no signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Tendon sheath lipomas, whether in the upper or lower extremities, are exceedingly rare entities. Further, lipomas of an individual extensor compartment of the hand (as in our case) have yet to be described, in contrast to lipomas of flexor tendon sheaths.3 There are only a handful of case reports in the literature of lipomas of the tendon sheath, and none to our knowledge of their existence in the extensor compartments of the hand. Nevertheless, it is important for the treating surgeon to be aware of their existence and know some basics about them and their treatment.

There are 2 types of tendon sheath lipomas: discrete solid masses of adipose tissue (which we encountered) and adipose tissue coupled with hypertrophic synovial villi (or, lipoma arborescens).4,5 Of note, the latter is significantly more common than the former, which makes our case even more uncommon. Although both types of lipoma of the tendon sheath are benign, they can cause symptoms such as pain, finger stiffness, and nerve compression.6 Thus, they frequently merit surgical removal, as in our case.

The appropriate workup for lipoma of the tendon sheath generally includes thorough history, physical examination, and advanced imaging, such as MRI. MRI is usually diagnostic of such a lesion and can aid in surgical planning.1 Regarding their overall prognosis, all lipomas (even large ones) are benign by definition but can transform into liposarcomas in rare cases.4 Lipomas are typically treated surgically by simple excision, and lipoma of the tendon sheath is no different. As long as complete excision of a tendon sheath lipoma is performed, recurrence rates are less than 5%.2,3

Surgeons should also be aware that, with long-standing lipomas of the tendon sheath, weakening of a tendon secondary to irritation from the mass is a possibility, especially in the lower extremities. All tendons should be inspected carefully at the time of surgery to ensure that other procedures, such as tendon grafting or side-to-side tenodesis, are not required. Although lipomas of the tendon sheath and extensor compartments are quite rare, all surgeons evaluating masses for possible surgical excision should be aware of their existence and know how to manage them appropriately.

1. Khan AZ, Shafafy M, Latimer MD, Crosby J. A lipoma within the Achilles tendon sheath. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(1):e16-e17.

2. Bryan RS, Dahlin DC, Sullivan CR. Lipoma of the tendon sheath. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38(6):1275-1280.

3. Kremchek TE, Kremchek EJ. Carpal tunnel syndrome caused by flexor tendon sheath lipoma. Orthop Rev. 1998;17(11):1083-1085.

4. Murphey MD, Caroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1433-1466.

5. Chronopoulous E, Nicholas P, Karanikas C, et al. Patient presenting with lipoma of the index finger: a case report. Cases J. 2010;3:20.

6. Elbardouni A, Kharmaz M, Salah Berrada M, Mahfoud M, Eylaacoubi M. Well-circumscribed deep-seated lesions of the upper extremity. A report of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2011;97(2):152-158.

Lipomas are relatively common benign tumors composed primarily of adipose tissue. They can occur anywhere on the body and are seen often in the hands and forearm. Typically localized to the subcutaneous fat layer, a lipoma is rarely associated with a tendon sheath or tendon compartment.1,2 When this uncommon event occurs, the lipoma is appropriately labeled lipoma of the tendon sheath.

While there are numerous case reports of lipomas of the tendon sheath occurring in association with tendons in the lower extremity, there are no reports, to our knowledge, of their occurrence in the extensor compartments of the hand.1 We report a rare case of lipoma of the tendon sheath localized to the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand, which was successfully treated with surgical excision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 33-year-old right hand–dominant waitress presented with a chief complaint of a painful, slowly enlarging right dorsal hand mass of 5 years’ duration. The mass was particularly bothersome with activities involving grip and finger extension. Physical examination revealed a mobile, rubbery mass on the dorsum of the hand that moved slightly with fist formation. There were no signs of neurovascular compromise. She had normal hand and wrist range of motion.

Plain radiographs were unremarkable (Figures 1A, 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast revealed a 4×2-cm mass consistent with a diagnosis of lipoma. However, it was unique in that it appeared to extend from the long- and ring-finger extensor tendon sheaths in the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand (Figures 2A, 2B) and was deemed a lipoma of the tendon sheath. Representative MRI also showed the lipoma to be present within the fourth extensor compartment of the hand (Figure 2B). Because of the mass’s increasing size and interference with hand function, the patient elected to have the mass excised.

Surgical Technique

A 3-cm longitudinal incision was made over the dorsum of the hand centered directly over the mass. Dissection was carried through the subcutaneous tissue to the distal margin of the extensor retinaculum. The fourth dorsal compartment was entered and the tendons of the fourth extensor compartment were identified. Immediately beneath the extensor tendons to the long and ring fingers was a yellow, rubbery mass consistent with lipoma (Figure 3). This mass was strongly adherent to the underlying tendons and had to be dissected carefully with tenotomy scissors. Fortunately, the mass could be excised as a single unit (Figure 4). It was sent to the pathology department for histologic examination, which revealed mature adipose tissue and confirmed the diagnosis of lipoma. The wound was closed with absorbable suture, and a soft, sterile dressing was applied.

Postoperative Care

The patient was seen in follow-up 2 weeks later for routine evaluation. She had an intact wound with minimal hand pain, and full wrist and hand range of motion. She returned to work as a waitress approximately 3 weeks after surgery without difficulty. At her 6-week postoperative mark, she had a pain-free wrist with a well-healed incision and no signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Tendon sheath lipomas, whether in the upper or lower extremities, are exceedingly rare entities. Further, lipomas of an individual extensor compartment of the hand (as in our case) have yet to be described, in contrast to lipomas of flexor tendon sheaths.3 There are only a handful of case reports in the literature of lipomas of the tendon sheath, and none to our knowledge of their existence in the extensor compartments of the hand. Nevertheless, it is important for the treating surgeon to be aware of their existence and know some basics about them and their treatment.

There are 2 types of tendon sheath lipomas: discrete solid masses of adipose tissue (which we encountered) and adipose tissue coupled with hypertrophic synovial villi (or, lipoma arborescens).4,5 Of note, the latter is significantly more common than the former, which makes our case even more uncommon. Although both types of lipoma of the tendon sheath are benign, they can cause symptoms such as pain, finger stiffness, and nerve compression.6 Thus, they frequently merit surgical removal, as in our case.

The appropriate workup for lipoma of the tendon sheath generally includes thorough history, physical examination, and advanced imaging, such as MRI. MRI is usually diagnostic of such a lesion and can aid in surgical planning.1 Regarding their overall prognosis, all lipomas (even large ones) are benign by definition but can transform into liposarcomas in rare cases.4 Lipomas are typically treated surgically by simple excision, and lipoma of the tendon sheath is no different. As long as complete excision of a tendon sheath lipoma is performed, recurrence rates are less than 5%.2,3

Surgeons should also be aware that, with long-standing lipomas of the tendon sheath, weakening of a tendon secondary to irritation from the mass is a possibility, especially in the lower extremities. All tendons should be inspected carefully at the time of surgery to ensure that other procedures, such as tendon grafting or side-to-side tenodesis, are not required. Although lipomas of the tendon sheath and extensor compartments are quite rare, all surgeons evaluating masses for possible surgical excision should be aware of their existence and know how to manage them appropriately.

Lipomas are relatively common benign tumors composed primarily of adipose tissue. They can occur anywhere on the body and are seen often in the hands and forearm. Typically localized to the subcutaneous fat layer, a lipoma is rarely associated with a tendon sheath or tendon compartment.1,2 When this uncommon event occurs, the lipoma is appropriately labeled lipoma of the tendon sheath.

While there are numerous case reports of lipomas of the tendon sheath occurring in association with tendons in the lower extremity, there are no reports, to our knowledge, of their occurrence in the extensor compartments of the hand.1 We report a rare case of lipoma of the tendon sheath localized to the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand, which was successfully treated with surgical excision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 33-year-old right hand–dominant waitress presented with a chief complaint of a painful, slowly enlarging right dorsal hand mass of 5 years’ duration. The mass was particularly bothersome with activities involving grip and finger extension. Physical examination revealed a mobile, rubbery mass on the dorsum of the hand that moved slightly with fist formation. There were no signs of neurovascular compromise. She had normal hand and wrist range of motion.

Plain radiographs were unremarkable (Figures 1A, 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast revealed a 4×2-cm mass consistent with a diagnosis of lipoma. However, it was unique in that it appeared to extend from the long- and ring-finger extensor tendon sheaths in the fourth dorsal compartment of the hand (Figures 2A, 2B) and was deemed a lipoma of the tendon sheath. Representative MRI also showed the lipoma to be present within the fourth extensor compartment of the hand (Figure 2B). Because of the mass’s increasing size and interference with hand function, the patient elected to have the mass excised.

Surgical Technique

A 3-cm longitudinal incision was made over the dorsum of the hand centered directly over the mass. Dissection was carried through the subcutaneous tissue to the distal margin of the extensor retinaculum. The fourth dorsal compartment was entered and the tendons of the fourth extensor compartment were identified. Immediately beneath the extensor tendons to the long and ring fingers was a yellow, rubbery mass consistent with lipoma (Figure 3). This mass was strongly adherent to the underlying tendons and had to be dissected carefully with tenotomy scissors. Fortunately, the mass could be excised as a single unit (Figure 4). It was sent to the pathology department for histologic examination, which revealed mature adipose tissue and confirmed the diagnosis of lipoma. The wound was closed with absorbable suture, and a soft, sterile dressing was applied.

Postoperative Care

The patient was seen in follow-up 2 weeks later for routine evaluation. She had an intact wound with minimal hand pain, and full wrist and hand range of motion. She returned to work as a waitress approximately 3 weeks after surgery without difficulty. At her 6-week postoperative mark, she had a pain-free wrist with a well-healed incision and no signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Tendon sheath lipomas, whether in the upper or lower extremities, are exceedingly rare entities. Further, lipomas of an individual extensor compartment of the hand (as in our case) have yet to be described, in contrast to lipomas of flexor tendon sheaths.3 There are only a handful of case reports in the literature of lipomas of the tendon sheath, and none to our knowledge of their existence in the extensor compartments of the hand. Nevertheless, it is important for the treating surgeon to be aware of their existence and know some basics about them and their treatment.

There are 2 types of tendon sheath lipomas: discrete solid masses of adipose tissue (which we encountered) and adipose tissue coupled with hypertrophic synovial villi (or, lipoma arborescens).4,5 Of note, the latter is significantly more common than the former, which makes our case even more uncommon. Although both types of lipoma of the tendon sheath are benign, they can cause symptoms such as pain, finger stiffness, and nerve compression.6 Thus, they frequently merit surgical removal, as in our case.

The appropriate workup for lipoma of the tendon sheath generally includes thorough history, physical examination, and advanced imaging, such as MRI. MRI is usually diagnostic of such a lesion and can aid in surgical planning.1 Regarding their overall prognosis, all lipomas (even large ones) are benign by definition but can transform into liposarcomas in rare cases.4 Lipomas are typically treated surgically by simple excision, and lipoma of the tendon sheath is no different. As long as complete excision of a tendon sheath lipoma is performed, recurrence rates are less than 5%.2,3

Surgeons should also be aware that, with long-standing lipomas of the tendon sheath, weakening of a tendon secondary to irritation from the mass is a possibility, especially in the lower extremities. All tendons should be inspected carefully at the time of surgery to ensure that other procedures, such as tendon grafting or side-to-side tenodesis, are not required. Although lipomas of the tendon sheath and extensor compartments are quite rare, all surgeons evaluating masses for possible surgical excision should be aware of their existence and know how to manage them appropriately.

1. Khan AZ, Shafafy M, Latimer MD, Crosby J. A lipoma within the Achilles tendon sheath. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(1):e16-e17.

2. Bryan RS, Dahlin DC, Sullivan CR. Lipoma of the tendon sheath. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38(6):1275-1280.

3. Kremchek TE, Kremchek EJ. Carpal tunnel syndrome caused by flexor tendon sheath lipoma. Orthop Rev. 1998;17(11):1083-1085.

4. Murphey MD, Caroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1433-1466.

5. Chronopoulous E, Nicholas P, Karanikas C, et al. Patient presenting with lipoma of the index finger: a case report. Cases J. 2010;3:20.

6. Elbardouni A, Kharmaz M, Salah Berrada M, Mahfoud M, Eylaacoubi M. Well-circumscribed deep-seated lesions of the upper extremity. A report of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2011;97(2):152-158.

1. Khan AZ, Shafafy M, Latimer MD, Crosby J. A lipoma within the Achilles tendon sheath. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(1):e16-e17.

2. Bryan RS, Dahlin DC, Sullivan CR. Lipoma of the tendon sheath. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38(6):1275-1280.

3. Kremchek TE, Kremchek EJ. Carpal tunnel syndrome caused by flexor tendon sheath lipoma. Orthop Rev. 1998;17(11):1083-1085.

4. Murphey MD, Caroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1433-1466.

5. Chronopoulous E, Nicholas P, Karanikas C, et al. Patient presenting with lipoma of the index finger: a case report. Cases J. 2010;3:20.

6. Elbardouni A, Kharmaz M, Salah Berrada M, Mahfoud M, Eylaacoubi M. Well-circumscribed deep-seated lesions of the upper extremity. A report of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res. 2011;97(2):152-158.

Perilunate Injuries

Perilunate injuries typically stem from a high-energy insult to the carpus. Because of their relative infrequency and often subtle radiographic and physical examination findings, these injuries are often undetected in the emergency department setting.1 Early anatomic reduction of any carpal malalignment is essential. Even with optimal treatment, complications such as generalized wrist stiffness, diminished grip strength, and posttraumatic arthritis, commonly develop; however, recent studies suggest these issues are often well tolerated.1-5 In this article, the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes after perilunate injuries are examined.

History and Physical Examination

Perilunate injuries result from high-energy trauma to the carpus. Patients with these injuries often present with vague wrist pain and loss of wrist motion. Their fingers are frequently held in slight flexion. The patient may complain of numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution. An acute carpal tunnel syndrome can rapidly develop. The general belief is that acute carpal tunnel syndrome occurs more commonly in pure volar lunate dislocations than in dorsal perilunate dislocations. However, no studies compare the incidence of acute carpal tunnel syndrome in lunate versus perilunate dislocations.

Radiographic Evaluation

Standard radiographic evaluation of a potential perilunate injury includes posteroanterior (PA), lateral, and oblique views of the wrist (Figure 1). A scaphoid view (ie, PA view with the wrist in ulnar deviation) may also be helpful. The PA view is particularly helpful because it enables assessment of Gilula lines, which are imaginary lines drawn across the proximal and distal aspects of the proximal carpal row and the proximal aspect of the distal carpal row. These lines should appear as 3 smooth arcs running nearly parallel to each other.6 Any disruption in these lines suggests carpal incongruity. It may be possible to note a triangular-shaped lunate on the PA view, which is a sign of lunate dislocation.7

While the PA view is certainly useful, the lateral view is the most important in diagnosing a perilunate injury. The lateral view allows assessment of the collinearity of radius, lunate, and capitate. Any disruption in this collinearity strongly suggests a perilunate dislocation.7,8

Classification

Mayfield and colleagues9,10 described 4 stages of perilunate instability proceeding from a radial to an ulnar direction around the lunate. Stage I involves disruption of the scapholunate joint, while stage II involves both the scapholunate and capitolunate joints. In stage III, the scapholunate, capitolunate, and lunotriquetral ligaments are disrupted, and the result is a perilunate dislocation, usually dorsal. Finally, in stage IV, all the ligaments surrounding the lunate are disrupted and the lunate dislocates, most often volarly.

Lastly, perilunate injuries can be classified as greater-arc injuries if concomitant fracture of the carpus occurs, lesser-arc injuries if the injury is purely ligamentous, or inferior-arc injuries if there is an associated fracture of the volar rim of the distal radius.8

Treatment

Closed Reduction

All acute perilunate dislocations should be managed initially with an attempted closed reduction.11 If the injury is older than 72 hours, such an attempt may be futile. For any closed reduction performed in the emergency department setting, intravenous sedation is generally advised for muscle relaxation. Gentle traction with finger traps can also be used prior to the reduction attempt. For a dorsal perilunate dislocation, longitudinal traction followed by volar flexion of the wrist with volar pressure on the lunate and dorsal pressure on the capitate (ie, Tavernier’s maneuver) is required. Once reduction is complete, PA and lateral views of the wrist should be obtained to assess carpal alignment. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction is required, although the timing of said procedure is an area of debate, which we will discuss later.1,3 Restoration of anatomic carpal alignment is essential to optimizing outcome, although it does not guarantee a good overall result.

Open Reduction

If successful closed reduction is achieved, the patient can be immobilized temporarily in a short-arm plaster splint. However, open reduction and either pinning or internal fixation will be required to maintain this alignment. The exact timing of open reduction and fixation is debatable and often dictated by the absence or presence of median nerve symptoms.1,3 If a patient with no median nerve symptoms undergoes a successful closed reduction, he or she may be stabilized surgically within 3 to 5 days (or longer) with either pins or headless screws. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction should be done within 2 to 3 days. However, if the patient has progressive numbness in the median nerve distribution upon presentation that fails to improve or worsens despite a successful closed reduction, an urgent open reduction (within 24 hours) and carpal tunnel release should be performed to prevent permanent damage to the median nerve.

Once open reduction is undertaken, a dorsal, volar, and combined approach can be used.2-4 In most cases the dorsal approach is selected first. A longitudinal incision is made over the dorsum of the wrist, centered on the Lister tubercle. Dissection occurs between the third and fourth dorsal compartments. After the capsule is exposed, reduction of the lunate to the capitate is confirmed. If any fractures are present in the carpus (eg, scaphoid), they are internally fixed. The scapholunate articulation is then addressed. In general, the scapholunate ligament is not disrupted with a transscaphoid perilunate dislocation. However, if the scapholunate ligament is disrupted, the joint should be reduced and pinned. Repair or reconstruction of the scapholunate ligament is performed. Finally, the lunotriquetral articulation is reduced and stabilized with pins. There are no studies that specifically suggest direct repair of the lunotriquetral ligament versus pinning of the lunotriquetral articulation, but the lunotriquetral ligament could be repaired in similar fashion to the scapholunate ligament at the surgeon’s discretion.

As an alternative to percutaneous pinning, intercarpal screw fixation can be used to stabilize the carpus. A 2007 study by Souer and colleagues12 showed no substantial difference in outcome between the 2 methods of fixation. However, a second procedure is required to remove the screws.

The volar approach, if selected, is typically done second and performed via an extended carpal tunnel incision. It allows decompression of the carpal tunnel and enables repair of volar capsular ligaments (ie, long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament), which increases overall carpal stability. Currently, many surgeons favor a combined dorsal-volar approach for its efficacy.2,3 Some use a dorsal approach in all patients and perform a volar procedure only if the patient has median nerve symptoms.4 However, Başar and colleagues13 report use of only the volar approach for treatment of perilunate injuries. The authors repaired the long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament. They reported reasonably good outcomes, which are equivalent to those reported in similar studies using dorsal or combined dorsal-volar approaches. However, no studies in the literature directly compare any of the different approaches with each other.

Postoperatively, patients are placed in a long-arm thumb-spica cast for 4 weeks, and then in a short-arm cast for 4 to 8 weeks (Figure 2). If present, pins are removed in 3 to 12 weeks, with most authors recommending removal at 8 weeks.2,14

Lastly, carpal tunnel symptoms can develop late and even after a successful reduction and surgical stabilization. One theory is that a significant perilunate injury can create slightly higher baseline carpal tunnel pressures, which can compromise the blood flow to the median nerve and cause carpal tunnel symptoms. Additionally, it is possible that direct median nerve contusion and/or traction injury via a displaced lunate can also cause these symptoms. Whatever the inciting cause of median-nerve irritation, a delayed carpal tunnel release is sometimes required.

Conclusion

Outcomes after either perilunate or lunate dislocation are fair to good at best but can be optimized with prompt, appropriate treatment. Closed reduction and casting as definitive treatment has been abandoned because of frequent loss of reduction.12 Early open reduction (ie, less than 3 days after injury) has been shown to be beneficial.1,2 However, even those treated early and with anatomic restoration of carpal alignment can expect a loss of grip strength and a range of motion of approximately 70% compared with the contralateral side.2-5 A recent study has suggested that lesser-arc injures generally have a poorer overall outcome than their greater-arc counterparts.15

More than half of all patients with perilunate injuries will develop radiographic signs of osteoarthritis, and some will require additional salvage procedures.3-5 Kremer and colleagues4 showed that overall results after perilunate injuries deteriorate with time. However, according to a paper by Forli and colleagues5 in which patients were followed a minimum of 10 years after their injuries, the authors found that, despite radiographic progression of arthritis, most patients maintained reasonable hand function.

1. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: a multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18(5):768-779.

2. Sotereanos DG, Mitsionis GJ, Giannakopoulos PN, Tomaino MM, Herndon JH. Perilunate dislocation and fracture dislocation: a critical analysis of the volar-dorsal approach. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):49-56.

3. Hildebrand KA, Ross DC, Patterson SD, Roth JH, MacDermid JC, King GJ. Dorsal perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: questionnaire, clinical, and radiographic evaluation. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(6):1069-1079.

4. Kremer T, Wendt M, Riedel K, Sauerbier M, Germann G, Bickert B. Open reduction for perilunate injuries--clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(10):1599-1606.

5. Forli A, Courvoisier A, Wimsey S, Corcella D, Moutet F. Perilunate dislocations and transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations: a retrospective study with minimum ten-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(1):62-68.

6. Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133(3):503-517.

7. Kozin SH. Perilunate injuries: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(2):114-120.

8. Graham TJ. The inferior arc injury: an addition to the family of complex carpal fracture-dislocation patterns. Am J Orthop. 2003;32(9 suppl):10-19.

9. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5(3):226-241.

10. Mayfield JK. Mechanism of carpal injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;149:45-54.

11. Adkison JW, Chapman MW. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;164:199-207.

12. Souer JS, Rutgers M, Andermahr J, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist: comparison of temporary screw versus K-wire fixation. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(3):318-325.

13. Başar H, Başar B, Erol B, Tetik C. Isolated volar surgical approach for the treatment of perilunate and lunate dislocations. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(3):301-315.

14. Komurcu M, Kürklü M, Ozturan KE, Mahirogullari M, Basbozkurt M. Early and delayed treatment of dorsal transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:535-540.

15. Massoud AH, Naam NH. Functional outcome of open reduction of chronic perilunate injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1852-1860.

Perilunate injuries typically stem from a high-energy insult to the carpus. Because of their relative infrequency and often subtle radiographic and physical examination findings, these injuries are often undetected in the emergency department setting.1 Early anatomic reduction of any carpal malalignment is essential. Even with optimal treatment, complications such as generalized wrist stiffness, diminished grip strength, and posttraumatic arthritis, commonly develop; however, recent studies suggest these issues are often well tolerated.1-5 In this article, the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes after perilunate injuries are examined.

History and Physical Examination

Perilunate injuries result from high-energy trauma to the carpus. Patients with these injuries often present with vague wrist pain and loss of wrist motion. Their fingers are frequently held in slight flexion. The patient may complain of numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution. An acute carpal tunnel syndrome can rapidly develop. The general belief is that acute carpal tunnel syndrome occurs more commonly in pure volar lunate dislocations than in dorsal perilunate dislocations. However, no studies compare the incidence of acute carpal tunnel syndrome in lunate versus perilunate dislocations.

Radiographic Evaluation

Standard radiographic evaluation of a potential perilunate injury includes posteroanterior (PA), lateral, and oblique views of the wrist (Figure 1). A scaphoid view (ie, PA view with the wrist in ulnar deviation) may also be helpful. The PA view is particularly helpful because it enables assessment of Gilula lines, which are imaginary lines drawn across the proximal and distal aspects of the proximal carpal row and the proximal aspect of the distal carpal row. These lines should appear as 3 smooth arcs running nearly parallel to each other.6 Any disruption in these lines suggests carpal incongruity. It may be possible to note a triangular-shaped lunate on the PA view, which is a sign of lunate dislocation.7

While the PA view is certainly useful, the lateral view is the most important in diagnosing a perilunate injury. The lateral view allows assessment of the collinearity of radius, lunate, and capitate. Any disruption in this collinearity strongly suggests a perilunate dislocation.7,8

Classification

Mayfield and colleagues9,10 described 4 stages of perilunate instability proceeding from a radial to an ulnar direction around the lunate. Stage I involves disruption of the scapholunate joint, while stage II involves both the scapholunate and capitolunate joints. In stage III, the scapholunate, capitolunate, and lunotriquetral ligaments are disrupted, and the result is a perilunate dislocation, usually dorsal. Finally, in stage IV, all the ligaments surrounding the lunate are disrupted and the lunate dislocates, most often volarly.

Lastly, perilunate injuries can be classified as greater-arc injuries if concomitant fracture of the carpus occurs, lesser-arc injuries if the injury is purely ligamentous, or inferior-arc injuries if there is an associated fracture of the volar rim of the distal radius.8

Treatment

Closed Reduction

All acute perilunate dislocations should be managed initially with an attempted closed reduction.11 If the injury is older than 72 hours, such an attempt may be futile. For any closed reduction performed in the emergency department setting, intravenous sedation is generally advised for muscle relaxation. Gentle traction with finger traps can also be used prior to the reduction attempt. For a dorsal perilunate dislocation, longitudinal traction followed by volar flexion of the wrist with volar pressure on the lunate and dorsal pressure on the capitate (ie, Tavernier’s maneuver) is required. Once reduction is complete, PA and lateral views of the wrist should be obtained to assess carpal alignment. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction is required, although the timing of said procedure is an area of debate, which we will discuss later.1,3 Restoration of anatomic carpal alignment is essential to optimizing outcome, although it does not guarantee a good overall result.

Open Reduction

If successful closed reduction is achieved, the patient can be immobilized temporarily in a short-arm plaster splint. However, open reduction and either pinning or internal fixation will be required to maintain this alignment. The exact timing of open reduction and fixation is debatable and often dictated by the absence or presence of median nerve symptoms.1,3 If a patient with no median nerve symptoms undergoes a successful closed reduction, he or she may be stabilized surgically within 3 to 5 days (or longer) with either pins or headless screws. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction should be done within 2 to 3 days. However, if the patient has progressive numbness in the median nerve distribution upon presentation that fails to improve or worsens despite a successful closed reduction, an urgent open reduction (within 24 hours) and carpal tunnel release should be performed to prevent permanent damage to the median nerve.

Once open reduction is undertaken, a dorsal, volar, and combined approach can be used.2-4 In most cases the dorsal approach is selected first. A longitudinal incision is made over the dorsum of the wrist, centered on the Lister tubercle. Dissection occurs between the third and fourth dorsal compartments. After the capsule is exposed, reduction of the lunate to the capitate is confirmed. If any fractures are present in the carpus (eg, scaphoid), they are internally fixed. The scapholunate articulation is then addressed. In general, the scapholunate ligament is not disrupted with a transscaphoid perilunate dislocation. However, if the scapholunate ligament is disrupted, the joint should be reduced and pinned. Repair or reconstruction of the scapholunate ligament is performed. Finally, the lunotriquetral articulation is reduced and stabilized with pins. There are no studies that specifically suggest direct repair of the lunotriquetral ligament versus pinning of the lunotriquetral articulation, but the lunotriquetral ligament could be repaired in similar fashion to the scapholunate ligament at the surgeon’s discretion.

As an alternative to percutaneous pinning, intercarpal screw fixation can be used to stabilize the carpus. A 2007 study by Souer and colleagues12 showed no substantial difference in outcome between the 2 methods of fixation. However, a second procedure is required to remove the screws.

The volar approach, if selected, is typically done second and performed via an extended carpal tunnel incision. It allows decompression of the carpal tunnel and enables repair of volar capsular ligaments (ie, long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament), which increases overall carpal stability. Currently, many surgeons favor a combined dorsal-volar approach for its efficacy.2,3 Some use a dorsal approach in all patients and perform a volar procedure only if the patient has median nerve symptoms.4 However, Başar and colleagues13 report use of only the volar approach for treatment of perilunate injuries. The authors repaired the long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament. They reported reasonably good outcomes, which are equivalent to those reported in similar studies using dorsal or combined dorsal-volar approaches. However, no studies in the literature directly compare any of the different approaches with each other.

Postoperatively, patients are placed in a long-arm thumb-spica cast for 4 weeks, and then in a short-arm cast for 4 to 8 weeks (Figure 2). If present, pins are removed in 3 to 12 weeks, with most authors recommending removal at 8 weeks.2,14

Lastly, carpal tunnel symptoms can develop late and even after a successful reduction and surgical stabilization. One theory is that a significant perilunate injury can create slightly higher baseline carpal tunnel pressures, which can compromise the blood flow to the median nerve and cause carpal tunnel symptoms. Additionally, it is possible that direct median nerve contusion and/or traction injury via a displaced lunate can also cause these symptoms. Whatever the inciting cause of median-nerve irritation, a delayed carpal tunnel release is sometimes required.

Conclusion

Outcomes after either perilunate or lunate dislocation are fair to good at best but can be optimized with prompt, appropriate treatment. Closed reduction and casting as definitive treatment has been abandoned because of frequent loss of reduction.12 Early open reduction (ie, less than 3 days after injury) has been shown to be beneficial.1,2 However, even those treated early and with anatomic restoration of carpal alignment can expect a loss of grip strength and a range of motion of approximately 70% compared with the contralateral side.2-5 A recent study has suggested that lesser-arc injures generally have a poorer overall outcome than their greater-arc counterparts.15

More than half of all patients with perilunate injuries will develop radiographic signs of osteoarthritis, and some will require additional salvage procedures.3-5 Kremer and colleagues4 showed that overall results after perilunate injuries deteriorate with time. However, according to a paper by Forli and colleagues5 in which patients were followed a minimum of 10 years after their injuries, the authors found that, despite radiographic progression of arthritis, most patients maintained reasonable hand function.

Perilunate injuries typically stem from a high-energy insult to the carpus. Because of their relative infrequency and often subtle radiographic and physical examination findings, these injuries are often undetected in the emergency department setting.1 Early anatomic reduction of any carpal malalignment is essential. Even with optimal treatment, complications such as generalized wrist stiffness, diminished grip strength, and posttraumatic arthritis, commonly develop; however, recent studies suggest these issues are often well tolerated.1-5 In this article, the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes after perilunate injuries are examined.

History and Physical Examination

Perilunate injuries result from high-energy trauma to the carpus. Patients with these injuries often present with vague wrist pain and loss of wrist motion. Their fingers are frequently held in slight flexion. The patient may complain of numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution. An acute carpal tunnel syndrome can rapidly develop. The general belief is that acute carpal tunnel syndrome occurs more commonly in pure volar lunate dislocations than in dorsal perilunate dislocations. However, no studies compare the incidence of acute carpal tunnel syndrome in lunate versus perilunate dislocations.

Radiographic Evaluation

Standard radiographic evaluation of a potential perilunate injury includes posteroanterior (PA), lateral, and oblique views of the wrist (Figure 1). A scaphoid view (ie, PA view with the wrist in ulnar deviation) may also be helpful. The PA view is particularly helpful because it enables assessment of Gilula lines, which are imaginary lines drawn across the proximal and distal aspects of the proximal carpal row and the proximal aspect of the distal carpal row. These lines should appear as 3 smooth arcs running nearly parallel to each other.6 Any disruption in these lines suggests carpal incongruity. It may be possible to note a triangular-shaped lunate on the PA view, which is a sign of lunate dislocation.7

While the PA view is certainly useful, the lateral view is the most important in diagnosing a perilunate injury. The lateral view allows assessment of the collinearity of radius, lunate, and capitate. Any disruption in this collinearity strongly suggests a perilunate dislocation.7,8

Classification

Mayfield and colleagues9,10 described 4 stages of perilunate instability proceeding from a radial to an ulnar direction around the lunate. Stage I involves disruption of the scapholunate joint, while stage II involves both the scapholunate and capitolunate joints. In stage III, the scapholunate, capitolunate, and lunotriquetral ligaments are disrupted, and the result is a perilunate dislocation, usually dorsal. Finally, in stage IV, all the ligaments surrounding the lunate are disrupted and the lunate dislocates, most often volarly.

Lastly, perilunate injuries can be classified as greater-arc injuries if concomitant fracture of the carpus occurs, lesser-arc injuries if the injury is purely ligamentous, or inferior-arc injuries if there is an associated fracture of the volar rim of the distal radius.8

Treatment

Closed Reduction

All acute perilunate dislocations should be managed initially with an attempted closed reduction.11 If the injury is older than 72 hours, such an attempt may be futile. For any closed reduction performed in the emergency department setting, intravenous sedation is generally advised for muscle relaxation. Gentle traction with finger traps can also be used prior to the reduction attempt. For a dorsal perilunate dislocation, longitudinal traction followed by volar flexion of the wrist with volar pressure on the lunate and dorsal pressure on the capitate (ie, Tavernier’s maneuver) is required. Once reduction is complete, PA and lateral views of the wrist should be obtained to assess carpal alignment. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction is required, although the timing of said procedure is an area of debate, which we will discuss later.1,3 Restoration of anatomic carpal alignment is essential to optimizing outcome, although it does not guarantee a good overall result.

Open Reduction

If successful closed reduction is achieved, the patient can be immobilized temporarily in a short-arm plaster splint. However, open reduction and either pinning or internal fixation will be required to maintain this alignment. The exact timing of open reduction and fixation is debatable and often dictated by the absence or presence of median nerve symptoms.1,3 If a patient with no median nerve symptoms undergoes a successful closed reduction, he or she may be stabilized surgically within 3 to 5 days (or longer) with either pins or headless screws. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, an open reduction should be done within 2 to 3 days. However, if the patient has progressive numbness in the median nerve distribution upon presentation that fails to improve or worsens despite a successful closed reduction, an urgent open reduction (within 24 hours) and carpal tunnel release should be performed to prevent permanent damage to the median nerve.

Once open reduction is undertaken, a dorsal, volar, and combined approach can be used.2-4 In most cases the dorsal approach is selected first. A longitudinal incision is made over the dorsum of the wrist, centered on the Lister tubercle. Dissection occurs between the third and fourth dorsal compartments. After the capsule is exposed, reduction of the lunate to the capitate is confirmed. If any fractures are present in the carpus (eg, scaphoid), they are internally fixed. The scapholunate articulation is then addressed. In general, the scapholunate ligament is not disrupted with a transscaphoid perilunate dislocation. However, if the scapholunate ligament is disrupted, the joint should be reduced and pinned. Repair or reconstruction of the scapholunate ligament is performed. Finally, the lunotriquetral articulation is reduced and stabilized with pins. There are no studies that specifically suggest direct repair of the lunotriquetral ligament versus pinning of the lunotriquetral articulation, but the lunotriquetral ligament could be repaired in similar fashion to the scapholunate ligament at the surgeon’s discretion.

As an alternative to percutaneous pinning, intercarpal screw fixation can be used to stabilize the carpus. A 2007 study by Souer and colleagues12 showed no substantial difference in outcome between the 2 methods of fixation. However, a second procedure is required to remove the screws.

The volar approach, if selected, is typically done second and performed via an extended carpal tunnel incision. It allows decompression of the carpal tunnel and enables repair of volar capsular ligaments (ie, long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament), which increases overall carpal stability. Currently, many surgeons favor a combined dorsal-volar approach for its efficacy.2,3 Some use a dorsal approach in all patients and perform a volar procedure only if the patient has median nerve symptoms.4 However, Başar and colleagues13 report use of only the volar approach for treatment of perilunate injuries. The authors repaired the long and short radiolunate ligaments, volar scapholunate ligament, and volar lunotriquetral ligament. They reported reasonably good outcomes, which are equivalent to those reported in similar studies using dorsal or combined dorsal-volar approaches. However, no studies in the literature directly compare any of the different approaches with each other.

Postoperatively, patients are placed in a long-arm thumb-spica cast for 4 weeks, and then in a short-arm cast for 4 to 8 weeks (Figure 2). If present, pins are removed in 3 to 12 weeks, with most authors recommending removal at 8 weeks.2,14

Lastly, carpal tunnel symptoms can develop late and even after a successful reduction and surgical stabilization. One theory is that a significant perilunate injury can create slightly higher baseline carpal tunnel pressures, which can compromise the blood flow to the median nerve and cause carpal tunnel symptoms. Additionally, it is possible that direct median nerve contusion and/or traction injury via a displaced lunate can also cause these symptoms. Whatever the inciting cause of median-nerve irritation, a delayed carpal tunnel release is sometimes required.

Conclusion

Outcomes after either perilunate or lunate dislocation are fair to good at best but can be optimized with prompt, appropriate treatment. Closed reduction and casting as definitive treatment has been abandoned because of frequent loss of reduction.12 Early open reduction (ie, less than 3 days after injury) has been shown to be beneficial.1,2 However, even those treated early and with anatomic restoration of carpal alignment can expect a loss of grip strength and a range of motion of approximately 70% compared with the contralateral side.2-5 A recent study has suggested that lesser-arc injures generally have a poorer overall outcome than their greater-arc counterparts.15

More than half of all patients with perilunate injuries will develop radiographic signs of osteoarthritis, and some will require additional salvage procedures.3-5 Kremer and colleagues4 showed that overall results after perilunate injuries deteriorate with time. However, according to a paper by Forli and colleagues5 in which patients were followed a minimum of 10 years after their injuries, the authors found that, despite radiographic progression of arthritis, most patients maintained reasonable hand function.

1. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: a multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18(5):768-779.

2. Sotereanos DG, Mitsionis GJ, Giannakopoulos PN, Tomaino MM, Herndon JH. Perilunate dislocation and fracture dislocation: a critical analysis of the volar-dorsal approach. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):49-56.

3. Hildebrand KA, Ross DC, Patterson SD, Roth JH, MacDermid JC, King GJ. Dorsal perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: questionnaire, clinical, and radiographic evaluation. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(6):1069-1079.

4. Kremer T, Wendt M, Riedel K, Sauerbier M, Germann G, Bickert B. Open reduction for perilunate injuries--clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(10):1599-1606.

5. Forli A, Courvoisier A, Wimsey S, Corcella D, Moutet F. Perilunate dislocations and transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations: a retrospective study with minimum ten-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(1):62-68.

6. Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133(3):503-517.

7. Kozin SH. Perilunate injuries: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(2):114-120.

8. Graham TJ. The inferior arc injury: an addition to the family of complex carpal fracture-dislocation patterns. Am J Orthop. 2003;32(9 suppl):10-19.

9. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5(3):226-241.

10. Mayfield JK. Mechanism of carpal injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;149:45-54.

11. Adkison JW, Chapman MW. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;164:199-207.

12. Souer JS, Rutgers M, Andermahr J, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist: comparison of temporary screw versus K-wire fixation. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(3):318-325.

13. Başar H, Başar B, Erol B, Tetik C. Isolated volar surgical approach for the treatment of perilunate and lunate dislocations. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(3):301-315.

14. Komurcu M, Kürklü M, Ozturan KE, Mahirogullari M, Basbozkurt M. Early and delayed treatment of dorsal transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:535-540.

15. Massoud AH, Naam NH. Functional outcome of open reduction of chronic perilunate injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1852-1860.

1. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: a multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18(5):768-779.

2. Sotereanos DG, Mitsionis GJ, Giannakopoulos PN, Tomaino MM, Herndon JH. Perilunate dislocation and fracture dislocation: a critical analysis of the volar-dorsal approach. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):49-56.

3. Hildebrand KA, Ross DC, Patterson SD, Roth JH, MacDermid JC, King GJ. Dorsal perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: questionnaire, clinical, and radiographic evaluation. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(6):1069-1079.

4. Kremer T, Wendt M, Riedel K, Sauerbier M, Germann G, Bickert B. Open reduction for perilunate injuries--clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(10):1599-1606.

5. Forli A, Courvoisier A, Wimsey S, Corcella D, Moutet F. Perilunate dislocations and transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations: a retrospective study with minimum ten-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(1):62-68.

6. Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133(3):503-517.

7. Kozin SH. Perilunate injuries: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(2):114-120.

8. Graham TJ. The inferior arc injury: an addition to the family of complex carpal fracture-dislocation patterns. Am J Orthop. 2003;32(9 suppl):10-19.

9. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5(3):226-241.

10. Mayfield JK. Mechanism of carpal injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;149:45-54.

11. Adkison JW, Chapman MW. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;164:199-207.

12. Souer JS, Rutgers M, Andermahr J, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist: comparison of temporary screw versus K-wire fixation. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(3):318-325.

13. Başar H, Başar B, Erol B, Tetik C. Isolated volar surgical approach for the treatment of perilunate and lunate dislocations. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(3):301-315.

14. Komurcu M, Kürklü M, Ozturan KE, Mahirogullari M, Basbozkurt M. Early and delayed treatment of dorsal transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:535-540.

15. Massoud AH, Naam NH. Functional outcome of open reduction of chronic perilunate injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1852-1860.