User login

Telescoping Stents to Maintain a 3-Way Patency of the Airway

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

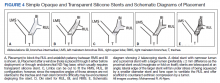

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

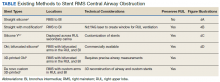

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

There are several malignant and nonmalignant conditions that can lead to central airway obstruction (CAO) resulting in lobar collapse. The clinical consequences range from significant dyspnea to respiratory failure. Airway stenting has been used to maintain patency of obstructed airways and relieve symptoms. Before lung cancer screening became more common, approximately 10% of lung cancers at presentation had evidence of CAO.1

On occasion, an endobronchial malignancy involves the right mainstem (RMS) bronchus near the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL).2 Such strategically located lesions pose a challenge to relieve the RMS obstruction through stenting, securing airway patency into the bronchus intermedius (BI) while avoiding obstruction of the RUL bronchus. The use of endobronchial silicone stents, hybrid covered stents, as well as self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is an established mode of relieving CAO due to malignant disease.3 We reviewed the literature for approaches that were available before and after the date of the index case reported here.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old veteran with a history of smoking presented to a US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in 2011, with hemoptysis of 2-week duration. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a 5.3 × 4.2 × 6.5 cm right mediastinal mass and a 3.0 × 2.8 × 3 cm right hilar mass. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed > 80% occlusion of the RMS and BI due to a medially located mass sparing the RUL orifice, which was patent (Figure 1). Airways distal to the BI were free of disease. Endobronchial biopsies revealed poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. The patient was referred to the interventional pulmonary service for further airway management.

Under general anesthesia and through a size-9 endotracheal tube, piecemeal debulking of the mass using a cryoprobe was performed. Argon photocoagulation (APC) was used to control bleeding. Balloon bronchoplasty was performed next with pulmonary Boston Scientific CRE balloon at the BI and the RMS bronchus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 12 × 30 mm self-expanding hybrid Merit Medical AERO stent was placed distally into the BI. Next, a 14 × 30 mm AERO stent was placed proximally in the RMS bronchus with its distal end telescoped into the smaller distal stent for a distance of 3 to 4 mm at a slanted angle. The overlap was deliberately performed at the level of RUL takeoff. Forcing the distal end of the proximal larger stent into a smaller stent created mechanical stress. The angled alignment channeled this mechanical stress so that the distal end of the proximal stent flared open laterally into the RUL orifice to allow for ventilation (Figure 2). On follow-up 6 months later, all 3 airways remained patent with stents in place (Figure 3).

The patient returned to the VAMC and underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel cycles that were completed in May 2012, as well as completing 6300 centigray (cGy) of radiation to the area. This led to regression of the tumor permitting removal of the proximal stent in October 2012. Unfortunately, upon follow-up in July 2013, a hypermetabolic lesion in the right upper posterior chest was noted to be eroding the third rib. Biopsy proved it to be poorly differentiated non-small cell lung cancer. Palliative external beam radiation was used to treat this lesion with a total of 3780 cGy completed by the end of August 2013.

Sadly, the patient was admitted later in 2013 with worsening cough and shortness of breath. Chest and abdominal CTs showed an increase in the size of the right apical mass, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, as well as innumerable nodules in the left lung. The mass had recurred and extended distal to the stent into the lower and middle lobes. New liver nodule and lytic lesion within left ischial tuberosity, T12, L1, and S1 vertebral bodies were noted. The pulmonary service reached out to us via email and we recommended either additional chemoradiotherapy or palliative care. At that point the tumor was widespread and resistant to therapy. It extended beyond the central airways making airway debulking futile. Stents are palliative in nature and we believed that the initial stenting allowed the patient to get chemoradiation by improving functional status through preventing collapse of the right lung. As a result, the patient had about 19 months of a remission period with quality of life. The patient ultimately died under the care of palliative care in inpatient hospice setting.

Literature Review

A literature review revealed multiple approaches to preserving a 3-way patent airway at the takeoff of the RUL (Table). One approach to alleviating such an obstruction favors placing a straight silicone stent from the RMS into the BI, closing off the orifice of the RUL (Figure 4A).4 However, this entails sacrificing ventilation of the RUL. An alternative suggested by Peled and colleagues was carried out successfully in 3 patients. After placing a stent to relieve the obstruction, a Nd:YAG laser is used to create a window in the stent in proximity to the RUL orifice, which allows preservation or ventilations to the RUL (Figure 4B).5

A third effective approach utilizes silicone Y stents, which are usually employed for relief of obstruction at the level of the main carina.6,7 Instead of deploying them at the main carina, they would be deployed at the secondary carina, which the RUL makes with the BI, often with customized cutting for adjustment of the stent limbs to the appropriate size of the RUL and BI (Figure 4C). This approach has been successfully used to maintain RUL ventilation.2

A fourth technique involves using an Oki stent, a dedicated bifurcated silicone stent, which was first described in 2013. It is designed for the RMS bronchus around the RUL and BI bifurcation, enabling the stent to maintain airway patency in the right lung without affecting the trachea and carina (Figure 4D). The arm located in the RUL prevents migration.8 A fifth technique involves deploying a precisely selected Oki stent specially modified based on a printed 3-dimensional (3D) model of the airways after computer-aided simulation.9A sixth technique employs de novo custom printing stents based on 3D models of the tracheobronchial tree constructed based on CT imaging. This approach creates more accurately fitting stents.1

Discussion

The RUL contributes roughly 5 to 10% of the total oxygenation capacity of the lung.10 In patients with lung cancer and limited pulmonary reserve, preserving ventilation to the RUL can be clinically important. The chosen method to relieve endobronchial obstruction depends on several variables, including expertise, ability of the patient to undergo general anesthesia for rigid or flexible bronchoscopy, stent availability, and airway anatomy.

This case illustrates a new method to deal with lesions close to the RUL orifice. This maneuver may not be possible with all types of stents. AERO stents are fully covered (Figure 4E). In contrast, stents that are uncovered at both distal ends, such as a Boston Scientific Ultraflex stent, may not be adequate for such a maneuver. Intercalating uncovered ends of SEMS may allow for tumor in-growth through the uncovered metal mesh near the RUL orifice and may paradoxically compromise both the RUL and BI. The diameter of AERO stents is slightly larger at its ends.11 This helps prevent migration, which in this case maintained the crucial overlap of the stents. On the other hand, use of AERO stents may be associated with a higher risk of infection.12 Precise measurements of the airway diameter are essential given the difference in internal and external stent diameter with silicone stents.

Silicone stents migrate more readily than SEMS and may not be well suited for the procedure we performed. In our case, we wished to maintain ventilation for the RUL; hence, we elected not to bypass it with a silicone stent. We did not have access to a YAG. Moreover, laser carries more energy than APC. Nd:YAG laser has been reported to cause airway fire when used with silicone stents.13 Several authors have reported the use of silicone Y stents at the primary or secondary carina to preserve luminal patency.6,7 Airway anatomy and the angle of the Y may require modification of these stents prior to their use. Cutting stents may compromise their integrity. The bifurcating limb prevents migration which can be a significant concern with the tubular silicone stents. An important consideration for patients in advanced stages of malignancy is that placement of such stent requires undergoing general anesthesia and rigid bronchoscopy, unlike with AERO and metal stents that can be deployed with fiberoptic bronchoscopy under moderate sedation. As such, we did not elect to use a silicone Y stent. Accumulation of secretions or formation of granulation tissue at the orifices can result in recurrence of obstruction.14

Advances in 3D printing seem to be the future of customized airway stenting. This could help clinicians overcome the challenges of improperly sized stents and distorted airway anatomy. Cases have reported successful use of 3D-printed patient-specific airway prostheses.15,16 However, their use is not common practice, as there is a limited amount of materials that are flexible, biocompatible, and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical use. Infection control is another layer of consideration in such stents. Standardization of materials and regulation of personalized devices and their cleansing protocols is neccesary.17 At the time of this case, Oki stents and 3D printing were not available in the market. This report provides a viable alternative to use AERO stents for this maneuver.

Conclusions

Patients presenting with malignant CAO near the RUL require a personalized approach to treatment, considering their overall health, functional status, nature and location of CAO, and degree of symptoms. Once a decision is made to stent the airway, careful assessment of airway anatomy, delineation of obstruction, available expertise, and types of stents available needs to be made to preserve ventilation to the nondiseased RUL. Airway stents are expensive and need to be used wisely for palliation and allowing for a quality life while the patient receives more definitive targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Jenny Kim, who referred the patient to the interventional service and helped obtain consent for publishing the case.

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

1. Criner GJ, Eberhardt R, Fernandez-Bussy S, et al. Interventional bronchoscopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):29-50. doi:10.1164/rccm.201907-1292SO

2. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, Kogure Y. Silicone y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):971-974. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.049

3. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, Mehta AC. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(12):1278-1297. doi:10.1164/rccm.200210-1181SO

4. Liu Y-H, Wu Y-C, Hsieh M-J, Ko P-J. Straight bronchial stent placement across the right upper lobe bronchus: A simple alternative for the management of airway obstruction around the carina and right main bronchus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):303-305.e1.doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.015

5. Peled N, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Kramer MR. Right upper lobe ‘window’ in right main bronchus stenting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(4):680-682. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.020

6. Dumon J-F, Dumon MC. Dumon-Novatech Y-stents: a four-year experience with 50 tracheobronchial tumors involving the carina. J Bronchol. 2000;7(1):26-32 doi:10.1097/00128594-200007000-00005

7. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, Seijo L. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126(3):951-958. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.951

8. Dalar L, Abul Y. Safety and efficacy of Oki stenting used to treat obstructions in the right mainstem bronchus. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25(3):212-217. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000486

9. Guibert N, Moreno B, Plat G, Didier A, Mazieres J, Hermant C. Stenting of complex malignant central-airway obstruction guided by a three-dimensional printed model of the airways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):e357-e359. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.082

10. Win T, Tasker AD, Groves AM, et al. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy to predict postoperative pulmonary function in lung cancer patients undergoing pneumonectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1260-1265. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1973

11. Mehta AC. AERO self-expanding hybrid stent for airway stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(5):553-557. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.5.553

12. Ost DE, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Respiratory infections increase the risk of granulation tissue formation following airway stenting in patients with malignant airway obstruction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1473-1481. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2005

13. Scherer TA. Nd-YAG laser ignition of silicone endobronchial stents. Chest. 2000;117(5):1449-1454. doi:10.1378/chest.117.5.1449

14. Folch E, Keyes C. Airway stents. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):273-283. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.03.08

15. Cheng GZ, Folch E, Brik R, et al. Three-dimensional modeled T-tube design and insertion in a patient with tracheal dehiscence. Chest. 2015;148(4):e106-e108. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0240

16. Tam MD, Laycock SD, Jayne D, Babar J, Noble B. 3-D printouts of the tracheobronchial tree generated from CT images as an aid to management in a case of tracheobronchial chondromalacia caused by relapsing polychondritis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(8):34-43. Published 2013 Aug 1. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v7i8.1390

17. Alraiyes AH, Avasarala SK, Machuzak MS, Gildea TR. 3D printing for airway disease. AME Med J. 2019;4:14. doi:10.21037/amj.2019.01.05

Right Ventricle Dilation Detected on Point-of-Care Ultrasound Is a Predictor of Poor Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is increasingly being used by critical care physicians to augment the physical examination and guide clinical decision making, and several protocols have been established to standardize the POCUS evaluation.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, POCUS has been a valuable tool as standard imaging techniques were used judiciously to minimize exposure of personnel and use of personal protective equipment (PPE).2

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS) intensive care unit (ICU) on initial clinical examination included POCUS, which was helpful to examine deep vein thromboses, cardiac function, and the presence and extent of pneumonia. An international expert consensus on the use of POCUS for COVID-19 published in December 2020 called for further studies defining the role of lung and cardiac ultrasound in risk stratification, outcomes, and clinical management.3

The objective of this study was to review POCUS findings and correlate them with severity of illness and 30-day outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

The study was submitted to and reviewed by the VANYHHS Research and Development committee and study approval and informed consent waiver was granted. The study was a retrospective chart review of patients admitted to the VANYHHS ICU between March and April 2020, a tertiary health care center designated as a COVID-19 hospital.

Patients admitted to the ICU aged > 18 years with a diagnosis of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, diagnosis of COVID-19, and documentation of POCUS findings in the chart were included in the study. A patient was considered to have a COVID-19 diagnosis following a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test documented in the electronic health record (EHR). Acute respiratory failure was defined as hypoxemia < 94% and the need for either supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula > 2 L/min, high flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, or mechanical ventilation.

To minimize personnel exposure, initial patient evaluations and POCUS examinations were performed by the most senior personnel (ie, fellowship trained, board-certified pulmonary critical care attending physicians or pulmonary and critical care fellowship trainees). Three members of the team had certification in advanced critical care echocardiography by the National Board of Echocardiography and oversaw POCUS imaging. POCUS examinations were performed with a GE Heathcare Venue POCUS or handheld unit. After use, ultrasound probes and ultrasound units were disinfected with wipes designated by the manufacturer and US Environmental Protection Agency for use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The POCUS protocol used by members of the team was as follows: POCUS lung—at least 2 anterior fields and 1 posterior/lateral field looking at the costophrenic angle on each hemithorax with a phased array or curvilinear probe. A linear probe was used to look for subpleural changes per physician discretion.4,5 Lung ultrasound findings in anterior lung fields were documented as A lines, B lines (as defined by the bedside lung ultrasound in emergency [BLUE] protocol)anterior pleural abnormalities or consolidations.4,5 The costophrenic point findings were documented as presence of consolidation or pleural effusion.

The POCUS cardiac examination consisted of parasternal long and short axis views, apical 4 chamber view, subcostal and inferior vena cava (IVC) view. Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was visually estimated as reduced or normal. Right ventricular (RV) dilation was considered present if RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view. RV dysfunction was considered present if in addition there was flattening of interventricular septum, RV free wall hypokinesis or reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE).6 IVC was documented as collapsible or plethoric by size and respirophasic variability (2 cm and 50%). Other POCUS examinations including venous compression were done at the discretion of the treating physician.7 POCUS was also used for the placement of central and arterial lines and to guide fluid management.8

The VA EHR and Venue image local archives were reviewed for patient demographics, laboratory findings, imaging studies and outcomes. All ICU attending physician and fellow notes were reviewed for POCUS lung, cardiac and vascular findings. The chart was also reviewed for management changes as a result of POCUS findings. Patients who had at minimum a POCUS lung or cardiac examination documented in the EHR were included in the study. For patients with serial POCUS the most severe findings were included.

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on 30-day outcome: discharge home vs mortality for comparison. POCUS findings were also compared by need for mechanical ventilation. Patients still hospitalized or transferred to other facilities were excluded from the analysis. A Student t test was used for comparison between the groups for continuous normally distributed variables. Linear and stepwise regression models were used to evaluate univariate and multivariate associations of baseline characteristics, biomarker, and ultrasound findings with patient outcomes. Analyses were performed using R 4.0.2 statistical software.

Results

Eighty-two patients were admitted to the VANYHHS ICU in March and April 2020, including 12 nonveterans. Sixty-four had COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure. POCUS findings were documented in 43 (67%) patients. Thirty-nine patients had documented lung examinations, and 25 patients had documented cardiac examinations. Patients were divided into 2 groups by 30-day outcome (discharge home vs mortality) for statistical analysis. Five patients who were either still hospitalized or had been transferred to another facility were excluded.

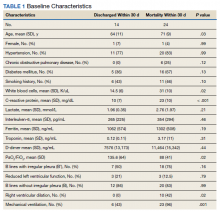

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the study stratified by 30-day outcomes are shown in Table 1. The study group was predominantly male (95%). Patients with poor 30-day outcomes were older, had higher white blood cell counts, more severe hypoxemia, higher rates of mechanical ventilation and RV dilation (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). RV dilation was an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio [OR], 12.0; P = .048).

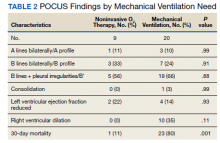

Serial POCUS documented development or progression of RV dilation and dysfunction from the time of ICU admission in 4 of the patients. The presence of B lines with irregular pleura was predictive of a lower arterial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) by a value of 71 compared with those without B lines with irregular pleura (P = .005, adjusted R2 = 0.238). All patients with RV dilation had bilateral B lines with pleural irregularities on lung ultrasound. Vascular POCUS detected 4 deep vein thromboses (DVT).7 An arterial thrombus was also detected on focused examination. There was a higher mortality in patients who required mechanical ventilation; however, there was no difference in POCUS characteristics between the groups (Table 2).

Two severely hypoxemic patients received systemic tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) after findings of massive RV dilation with signs of volume and pressure overload and clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism (PE). One of these patients also had a popliteal DVT. Both patients were too unstable to transport for additional imaging or therapies. Therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated on 4 patients with positive DVT examinations. In a fifth case an arterial thrombectomy and anticoagulation was required after diminished pulses led to the finding of an occlusive brachial artery thrombus on vascular POCUS.

Discussion

POCUS identified both lung and cardiac features that were associated with worse outcomes. While lung ultrasound abnormalities were very prevalent and associated with worse PaO2 to FiO2 ratios, the presence of RV dilation was associated most clearly with mortality and poor 30-day outcomes in the critical care setting.

Lung ultrasound abnormalities were pervasive in patients with acute respiratory failure and COVID-19. On linear regression we found that presence with bilateral B lines and pleural thickening was predictive of a lower PaO2/FiO2 (coefficient, -70; P = .005). Our study found that B lines with pleural irregularities, otherwise known as a B’ profile per the BLUE protocol, was seen in patients with severe COVID-19. Thus severe acute respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 has similar lung ultrasound findings as non-COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).4,5 Based on prior lung ultrasound studies in ARDS, lung ultrasound findings can be used as an alternate to chest radiography for the diagnosis of ARDS in COVID-19 and predict the severity of ARDS.9 This has particular implications in overwhelmed and resource poor health care settings.

We found no difference in 30-day mortality based on lung ultrasound findings or profile, probably because of small sample size or because the findings were tabulated as profiles and not differentiated further with lung ultrasound scores.10,11 However, there was a significant difference in RV dilation between the 2 groups by 30 days and its presence was found to be a predictor of mortality even when controlled for hypertension and diabetes mellitus (P = .048) with an OR of 12. RV dysfunction in patients with ARDS on mechanical ventilation ranges from 22 to 25% and is typically associated with high driving pressures.12-14 The mechanism is thought to be multifactorial including hypoxemic vasoconstriction in the pulmonary vasculature in addition to the increased transpulmonary pressure.15 While all of the above are at play in COVID-19 infection, there is reported damage to the pulmonary vascular endothelium and resultant hypercoagulability and thrombosis that further increases the RV afterload.16

While RV strain and dysfunction indices done by an echocardiographer would be ideal, given the surge in infections and hospitalizations and strain on health care resources, POCUS by the treating or examining clinician was considered the only feasible way to screen a large number of patients.17 Identification of RV dilation could influence clinical management including workup for venous thromboembolic disease and optimization of lung protective strategies. Further studies are needed to understand the particular etiology and pathophysiology of COVID-19 associated RV dilation. Given increased thrombosis events in COVID-19 infection we believe a POCUS vascular examination should be included as part of evaluation especially in the presence of increased D-dimers and has been discussed above for its important role in working up RV dilation.18

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. It was retrospective in nature and involved a small group of individuals. There was some variation in POCUS examinations done at the discretion of the examining physician. We did not have a blinded observer independently review all images. Since RV dilation was documented only when RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view representing moderate or severe dilation, we may be underreporting the prevalence in critically ill patients.

Conclusions

POCUS is an invaluable adjunct to clinical evaluation and procedures in patients with severe COVID-19 with the ability to identity patients at risk for worse outcomes. B lines with pleural thickening is a sign of severe ARDS and RV dilatation is predictive of mortality. POCUS should be made available to the treating physician for monitoring and risk stratification and can be incorporated into management algorithms.

Additional point-of-care ultrasound videos.

Acknowledgments

We thank frontline healthcare workers and intensive care unit staff of the US Department of Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System (NYHHS) for their dedication to the care of veterans and civilians during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. The authors acknowledge the NYHHS research and development committee and administration for their support.

1. Cardenas-Garcia J, Mayo PH. Bedside ultrasonography for the intensivist. Crit Care Clin. 2015;31(1):43-66. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2014.08.003

2. Vetrugno L, Baciarello M, Bignami E, et al. The “pandemic” increase in lung ultrasound use in response to Covid-19: can we complement computed tomography findings? A narrative review. Ultrasound J. 2020;12(1):39. Published 2020 Aug 17. doi:10.1186/s13089-020-00185-4

3. Hussain A, Via G, Melniker L, et al. Multi-organ point-of-care ultrasound for COVID-19 (PoCUS4COVID): international expert consensus. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):702. Published 2020 Dec 24. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-03369-5

4. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol [published correction appears in Chest. 2013 Aug;144(2):721]. Chest. 2008;134(1):117-125. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2800

5. Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(4):577-591. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4

6. Narasimhan M, Koenig SJ, Mayo PH. Advanced echocardiography for the critical care physician: part 1. Chest. 2014;145(1):129-134. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2441

7. Kory PD, Pellecchia CM, Shiloh AL, Mayo PH, DiBello C, Koenig S. Accuracy of ultrasonography performed by critical care physicians for the diagnosis of DVT. Chest. 2011;139(3):538-542. doi:10.1378/chest.10-1479

8. Bentzer P, Griesdale DE, Boyd J, MacLean K, Sirounis D, Ayas NT. Will this hemodynamically unstable patient respond to a bolus of intravenous fluids? JAMA. 2016;316(12):1298-1309. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12310

9. See KC, Ong V, Tan YL, Sahagun J, Taculod J. Chest radiography versus lung ultrasound for identification of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective observational study. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):203. Published 2018 Aug 18. doi:10.1186/s13054-018-2105-y

10. Deng Q, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. Semiquantitative lung ultrasound scores in the evaluation and follow-up of critically ill patients with COVID-19: a single-center study. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(10):1363-1372. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2020.07.002

11. Brahier T, Meuwly JY, Pantet O, et al. Lung ultrasonography for risk stratification in patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 17]. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1408. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1408

12. Vieillard-Baron A, Schmitt JM, Augarde R, et al. Acute cor pulmonale in acute respiratory distress syndrome submitted to protective ventilation: incidence, clinical implications, and prognosis [published correction appears in Crit Care Med. 2002 Mar;30(3):726]. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(8):1551-1555. doi:10.1097/00003246-200108000-00009

13. Boissier F, Katsahian S, Razazi K, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(10):1725-1733. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2941-9

14. Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Is there a safe plateau pressure in ARDS? The right heart only knows. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(3):444-447. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0552-z

15. Repessé X, Vieillard-Baron A. Right heart function during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med 2017;5(14):295. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.06.66

16. Abou-Ismail MY, Diamond A, Kapoor S, Arafah Y, Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: Incidence, pathophysiology, and management [published correction appears in Thromb Res. 2020 Nov 26]. Thromb Res. 2020;194:101-115. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.029

17. Kim J, Volodarskiy A, Sultana R, et al. Prognostic utility of right ventricular remodeling over conventional risk stratification in patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(17):1965-1977. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.066

18. Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489-500. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006520

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is increasingly being used by critical care physicians to augment the physical examination and guide clinical decision making, and several protocols have been established to standardize the POCUS evaluation.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, POCUS has been a valuable tool as standard imaging techniques were used judiciously to minimize exposure of personnel and use of personal protective equipment (PPE).2

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS) intensive care unit (ICU) on initial clinical examination included POCUS, which was helpful to examine deep vein thromboses, cardiac function, and the presence and extent of pneumonia. An international expert consensus on the use of POCUS for COVID-19 published in December 2020 called for further studies defining the role of lung and cardiac ultrasound in risk stratification, outcomes, and clinical management.3

The objective of this study was to review POCUS findings and correlate them with severity of illness and 30-day outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

The study was submitted to and reviewed by the VANYHHS Research and Development committee and study approval and informed consent waiver was granted. The study was a retrospective chart review of patients admitted to the VANYHHS ICU between March and April 2020, a tertiary health care center designated as a COVID-19 hospital.

Patients admitted to the ICU aged > 18 years with a diagnosis of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, diagnosis of COVID-19, and documentation of POCUS findings in the chart were included in the study. A patient was considered to have a COVID-19 diagnosis following a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test documented in the electronic health record (EHR). Acute respiratory failure was defined as hypoxemia < 94% and the need for either supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula > 2 L/min, high flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, or mechanical ventilation.

To minimize personnel exposure, initial patient evaluations and POCUS examinations were performed by the most senior personnel (ie, fellowship trained, board-certified pulmonary critical care attending physicians or pulmonary and critical care fellowship trainees). Three members of the team had certification in advanced critical care echocardiography by the National Board of Echocardiography and oversaw POCUS imaging. POCUS examinations were performed with a GE Heathcare Venue POCUS or handheld unit. After use, ultrasound probes and ultrasound units were disinfected with wipes designated by the manufacturer and US Environmental Protection Agency for use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The POCUS protocol used by members of the team was as follows: POCUS lung—at least 2 anterior fields and 1 posterior/lateral field looking at the costophrenic angle on each hemithorax with a phased array or curvilinear probe. A linear probe was used to look for subpleural changes per physician discretion.4,5 Lung ultrasound findings in anterior lung fields were documented as A lines, B lines (as defined by the bedside lung ultrasound in emergency [BLUE] protocol)anterior pleural abnormalities or consolidations.4,5 The costophrenic point findings were documented as presence of consolidation or pleural effusion.

The POCUS cardiac examination consisted of parasternal long and short axis views, apical 4 chamber view, subcostal and inferior vena cava (IVC) view. Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was visually estimated as reduced or normal. Right ventricular (RV) dilation was considered present if RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view. RV dysfunction was considered present if in addition there was flattening of interventricular septum, RV free wall hypokinesis or reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE).6 IVC was documented as collapsible or plethoric by size and respirophasic variability (2 cm and 50%). Other POCUS examinations including venous compression were done at the discretion of the treating physician.7 POCUS was also used for the placement of central and arterial lines and to guide fluid management.8

The VA EHR and Venue image local archives were reviewed for patient demographics, laboratory findings, imaging studies and outcomes. All ICU attending physician and fellow notes were reviewed for POCUS lung, cardiac and vascular findings. The chart was also reviewed for management changes as a result of POCUS findings. Patients who had at minimum a POCUS lung or cardiac examination documented in the EHR were included in the study. For patients with serial POCUS the most severe findings were included.

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on 30-day outcome: discharge home vs mortality for comparison. POCUS findings were also compared by need for mechanical ventilation. Patients still hospitalized or transferred to other facilities were excluded from the analysis. A Student t test was used for comparison between the groups for continuous normally distributed variables. Linear and stepwise regression models were used to evaluate univariate and multivariate associations of baseline characteristics, biomarker, and ultrasound findings with patient outcomes. Analyses were performed using R 4.0.2 statistical software.

Results

Eighty-two patients were admitted to the VANYHHS ICU in March and April 2020, including 12 nonveterans. Sixty-four had COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure. POCUS findings were documented in 43 (67%) patients. Thirty-nine patients had documented lung examinations, and 25 patients had documented cardiac examinations. Patients were divided into 2 groups by 30-day outcome (discharge home vs mortality) for statistical analysis. Five patients who were either still hospitalized or had been transferred to another facility were excluded.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the study stratified by 30-day outcomes are shown in Table 1. The study group was predominantly male (95%). Patients with poor 30-day outcomes were older, had higher white blood cell counts, more severe hypoxemia, higher rates of mechanical ventilation and RV dilation (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). RV dilation was an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio [OR], 12.0; P = .048).

Serial POCUS documented development or progression of RV dilation and dysfunction from the time of ICU admission in 4 of the patients. The presence of B lines with irregular pleura was predictive of a lower arterial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) by a value of 71 compared with those without B lines with irregular pleura (P = .005, adjusted R2 = 0.238). All patients with RV dilation had bilateral B lines with pleural irregularities on lung ultrasound. Vascular POCUS detected 4 deep vein thromboses (DVT).7 An arterial thrombus was also detected on focused examination. There was a higher mortality in patients who required mechanical ventilation; however, there was no difference in POCUS characteristics between the groups (Table 2).

Two severely hypoxemic patients received systemic tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) after findings of massive RV dilation with signs of volume and pressure overload and clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism (PE). One of these patients also had a popliteal DVT. Both patients were too unstable to transport for additional imaging or therapies. Therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated on 4 patients with positive DVT examinations. In a fifth case an arterial thrombectomy and anticoagulation was required after diminished pulses led to the finding of an occlusive brachial artery thrombus on vascular POCUS.

Discussion

POCUS identified both lung and cardiac features that were associated with worse outcomes. While lung ultrasound abnormalities were very prevalent and associated with worse PaO2 to FiO2 ratios, the presence of RV dilation was associated most clearly with mortality and poor 30-day outcomes in the critical care setting.

Lung ultrasound abnormalities were pervasive in patients with acute respiratory failure and COVID-19. On linear regression we found that presence with bilateral B lines and pleural thickening was predictive of a lower PaO2/FiO2 (coefficient, -70; P = .005). Our study found that B lines with pleural irregularities, otherwise known as a B’ profile per the BLUE protocol, was seen in patients with severe COVID-19. Thus severe acute respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 has similar lung ultrasound findings as non-COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).4,5 Based on prior lung ultrasound studies in ARDS, lung ultrasound findings can be used as an alternate to chest radiography for the diagnosis of ARDS in COVID-19 and predict the severity of ARDS.9 This has particular implications in overwhelmed and resource poor health care settings.

We found no difference in 30-day mortality based on lung ultrasound findings or profile, probably because of small sample size or because the findings were tabulated as profiles and not differentiated further with lung ultrasound scores.10,11 However, there was a significant difference in RV dilation between the 2 groups by 30 days and its presence was found to be a predictor of mortality even when controlled for hypertension and diabetes mellitus (P = .048) with an OR of 12. RV dysfunction in patients with ARDS on mechanical ventilation ranges from 22 to 25% and is typically associated with high driving pressures.12-14 The mechanism is thought to be multifactorial including hypoxemic vasoconstriction in the pulmonary vasculature in addition to the increased transpulmonary pressure.15 While all of the above are at play in COVID-19 infection, there is reported damage to the pulmonary vascular endothelium and resultant hypercoagulability and thrombosis that further increases the RV afterload.16

While RV strain and dysfunction indices done by an echocardiographer would be ideal, given the surge in infections and hospitalizations and strain on health care resources, POCUS by the treating or examining clinician was considered the only feasible way to screen a large number of patients.17 Identification of RV dilation could influence clinical management including workup for venous thromboembolic disease and optimization of lung protective strategies. Further studies are needed to understand the particular etiology and pathophysiology of COVID-19 associated RV dilation. Given increased thrombosis events in COVID-19 infection we believe a POCUS vascular examination should be included as part of evaluation especially in the presence of increased D-dimers and has been discussed above for its important role in working up RV dilation.18

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. It was retrospective in nature and involved a small group of individuals. There was some variation in POCUS examinations done at the discretion of the examining physician. We did not have a blinded observer independently review all images. Since RV dilation was documented only when RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view representing moderate or severe dilation, we may be underreporting the prevalence in critically ill patients.

Conclusions

POCUS is an invaluable adjunct to clinical evaluation and procedures in patients with severe COVID-19 with the ability to identity patients at risk for worse outcomes. B lines with pleural thickening is a sign of severe ARDS and RV dilatation is predictive of mortality. POCUS should be made available to the treating physician for monitoring and risk stratification and can be incorporated into management algorithms.

Additional point-of-care ultrasound videos.

Acknowledgments

We thank frontline healthcare workers and intensive care unit staff of the US Department of Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System (NYHHS) for their dedication to the care of veterans and civilians during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. The authors acknowledge the NYHHS research and development committee and administration for their support.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is increasingly being used by critical care physicians to augment the physical examination and guide clinical decision making, and several protocols have been established to standardize the POCUS evaluation.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, POCUS has been a valuable tool as standard imaging techniques were used judiciously to minimize exposure of personnel and use of personal protective equipment (PPE).2

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS) intensive care unit (ICU) on initial clinical examination included POCUS, which was helpful to examine deep vein thromboses, cardiac function, and the presence and extent of pneumonia. An international expert consensus on the use of POCUS for COVID-19 published in December 2020 called for further studies defining the role of lung and cardiac ultrasound in risk stratification, outcomes, and clinical management.3

The objective of this study was to review POCUS findings and correlate them with severity of illness and 30-day outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

The study was submitted to and reviewed by the VANYHHS Research and Development committee and study approval and informed consent waiver was granted. The study was a retrospective chart review of patients admitted to the VANYHHS ICU between March and April 2020, a tertiary health care center designated as a COVID-19 hospital.

Patients admitted to the ICU aged > 18 years with a diagnosis of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, diagnosis of COVID-19, and documentation of POCUS findings in the chart were included in the study. A patient was considered to have a COVID-19 diagnosis following a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test documented in the electronic health record (EHR). Acute respiratory failure was defined as hypoxemia < 94% and the need for either supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula > 2 L/min, high flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, or mechanical ventilation.

To minimize personnel exposure, initial patient evaluations and POCUS examinations were performed by the most senior personnel (ie, fellowship trained, board-certified pulmonary critical care attending physicians or pulmonary and critical care fellowship trainees). Three members of the team had certification in advanced critical care echocardiography by the National Board of Echocardiography and oversaw POCUS imaging. POCUS examinations were performed with a GE Heathcare Venue POCUS or handheld unit. After use, ultrasound probes and ultrasound units were disinfected with wipes designated by the manufacturer and US Environmental Protection Agency for use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The POCUS protocol used by members of the team was as follows: POCUS lung—at least 2 anterior fields and 1 posterior/lateral field looking at the costophrenic angle on each hemithorax with a phased array or curvilinear probe. A linear probe was used to look for subpleural changes per physician discretion.4,5 Lung ultrasound findings in anterior lung fields were documented as A lines, B lines (as defined by the bedside lung ultrasound in emergency [BLUE] protocol)anterior pleural abnormalities or consolidations.4,5 The costophrenic point findings were documented as presence of consolidation or pleural effusion.

The POCUS cardiac examination consisted of parasternal long and short axis views, apical 4 chamber view, subcostal and inferior vena cava (IVC) view. Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was visually estimated as reduced or normal. Right ventricular (RV) dilation was considered present if RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view. RV dysfunction was considered present if in addition there was flattening of interventricular septum, RV free wall hypokinesis or reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE).6 IVC was documented as collapsible or plethoric by size and respirophasic variability (2 cm and 50%). Other POCUS examinations including venous compression were done at the discretion of the treating physician.7 POCUS was also used for the placement of central and arterial lines and to guide fluid management.8

The VA EHR and Venue image local archives were reviewed for patient demographics, laboratory findings, imaging studies and outcomes. All ICU attending physician and fellow notes were reviewed for POCUS lung, cardiac and vascular findings. The chart was also reviewed for management changes as a result of POCUS findings. Patients who had at minimum a POCUS lung or cardiac examination documented in the EHR were included in the study. For patients with serial POCUS the most severe findings were included.

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on 30-day outcome: discharge home vs mortality for comparison. POCUS findings were also compared by need for mechanical ventilation. Patients still hospitalized or transferred to other facilities were excluded from the analysis. A Student t test was used for comparison between the groups for continuous normally distributed variables. Linear and stepwise regression models were used to evaluate univariate and multivariate associations of baseline characteristics, biomarker, and ultrasound findings with patient outcomes. Analyses were performed using R 4.0.2 statistical software.

Results

Eighty-two patients were admitted to the VANYHHS ICU in March and April 2020, including 12 nonveterans. Sixty-four had COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure. POCUS findings were documented in 43 (67%) patients. Thirty-nine patients had documented lung examinations, and 25 patients had documented cardiac examinations. Patients were divided into 2 groups by 30-day outcome (discharge home vs mortality) for statistical analysis. Five patients who were either still hospitalized or had been transferred to another facility were excluded.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the study stratified by 30-day outcomes are shown in Table 1. The study group was predominantly male (95%). Patients with poor 30-day outcomes were older, had higher white blood cell counts, more severe hypoxemia, higher rates of mechanical ventilation and RV dilation (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). RV dilation was an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio [OR], 12.0; P = .048).

Serial POCUS documented development or progression of RV dilation and dysfunction from the time of ICU admission in 4 of the patients. The presence of B lines with irregular pleura was predictive of a lower arterial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) by a value of 71 compared with those without B lines with irregular pleura (P = .005, adjusted R2 = 0.238). All patients with RV dilation had bilateral B lines with pleural irregularities on lung ultrasound. Vascular POCUS detected 4 deep vein thromboses (DVT).7 An arterial thrombus was also detected on focused examination. There was a higher mortality in patients who required mechanical ventilation; however, there was no difference in POCUS characteristics between the groups (Table 2).

Two severely hypoxemic patients received systemic tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) after findings of massive RV dilation with signs of volume and pressure overload and clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism (PE). One of these patients also had a popliteal DVT. Both patients were too unstable to transport for additional imaging or therapies. Therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated on 4 patients with positive DVT examinations. In a fifth case an arterial thrombectomy and anticoagulation was required after diminished pulses led to the finding of an occlusive brachial artery thrombus on vascular POCUS.

Discussion

POCUS identified both lung and cardiac features that were associated with worse outcomes. While lung ultrasound abnormalities were very prevalent and associated with worse PaO2 to FiO2 ratios, the presence of RV dilation was associated most clearly with mortality and poor 30-day outcomes in the critical care setting.