User login

Light Brown and Pink Macule on the Upper Arm

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

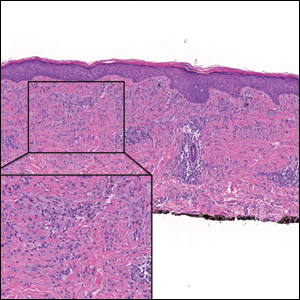

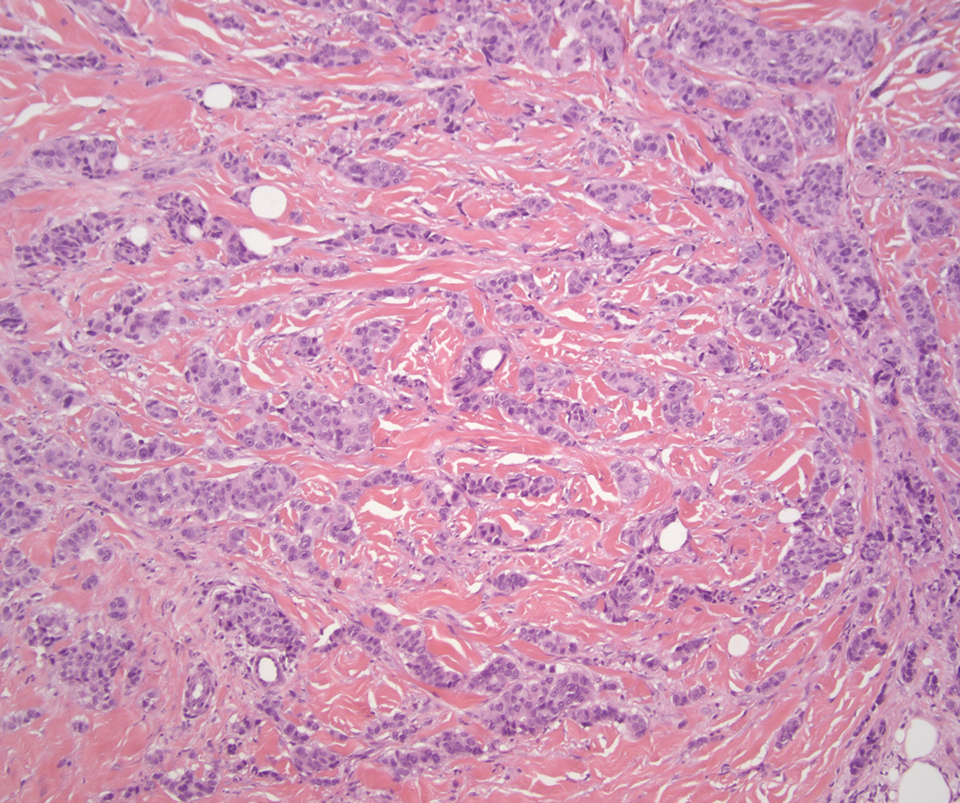

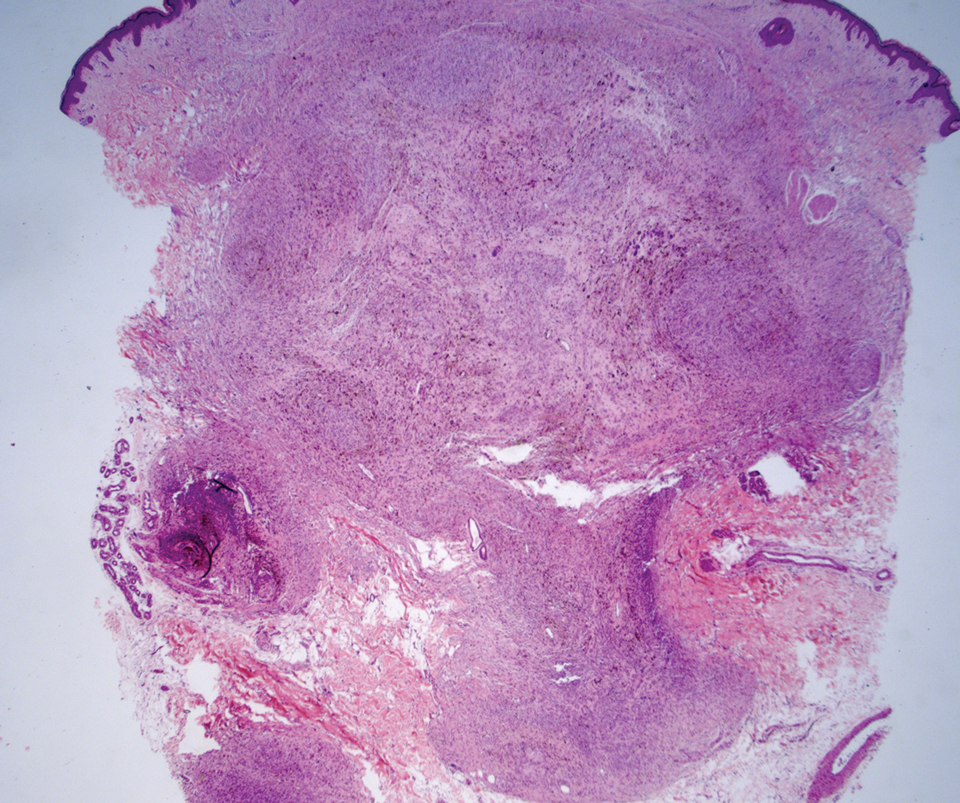

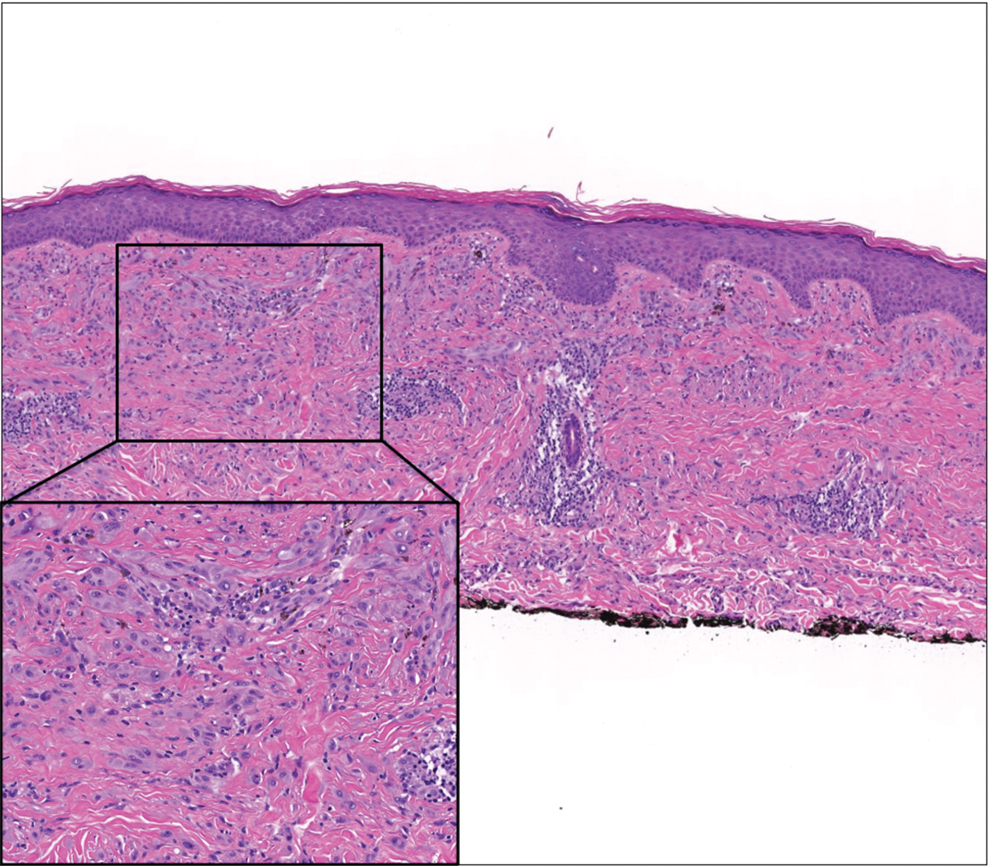

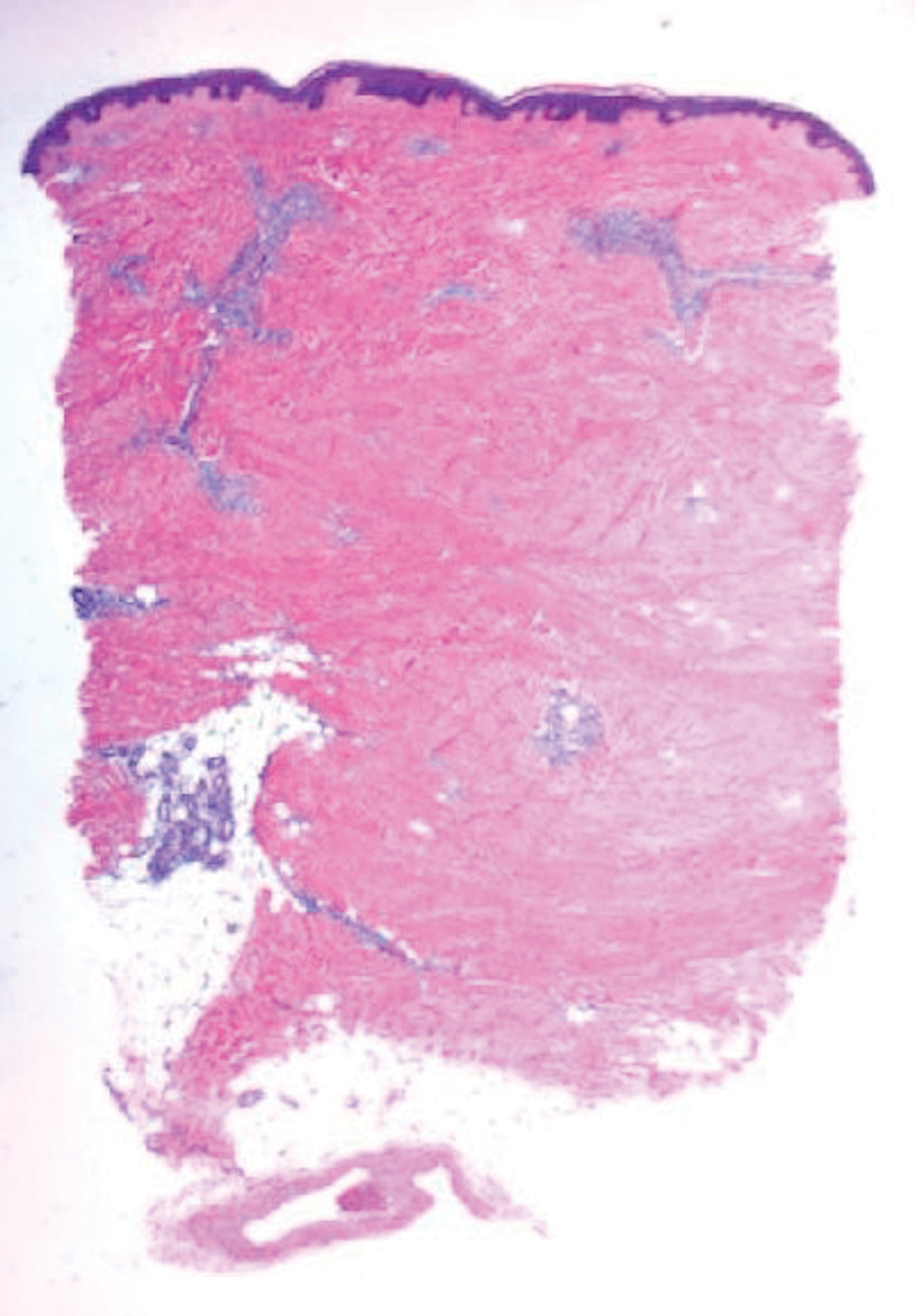

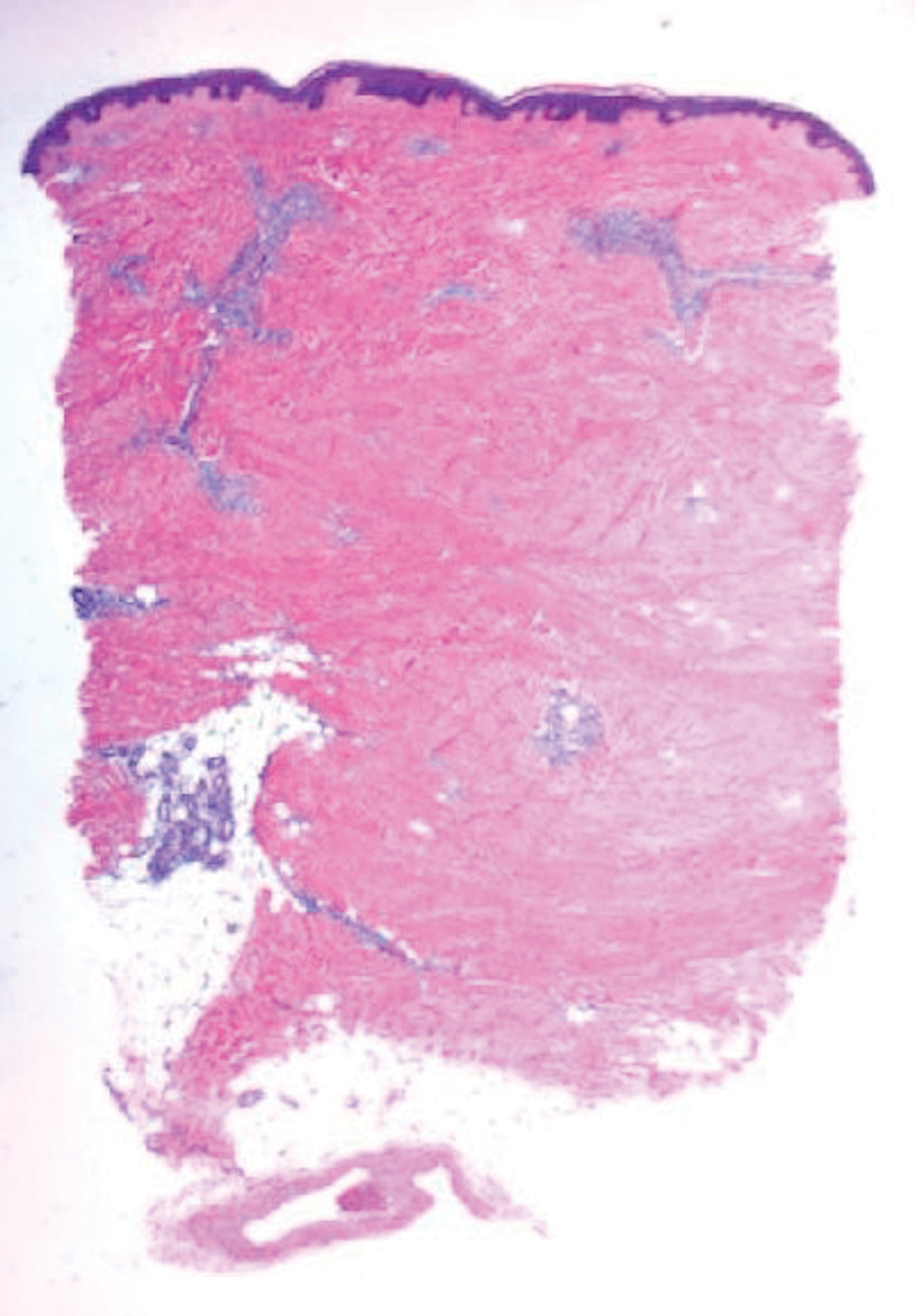

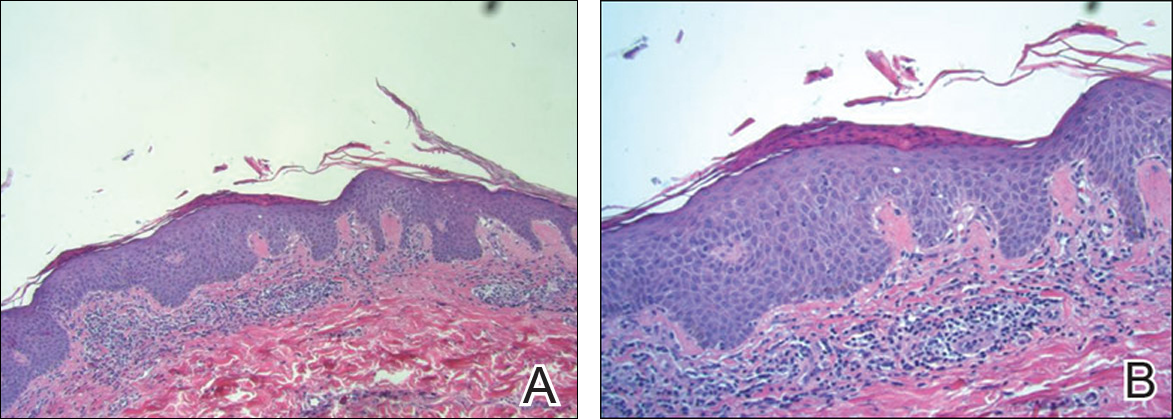

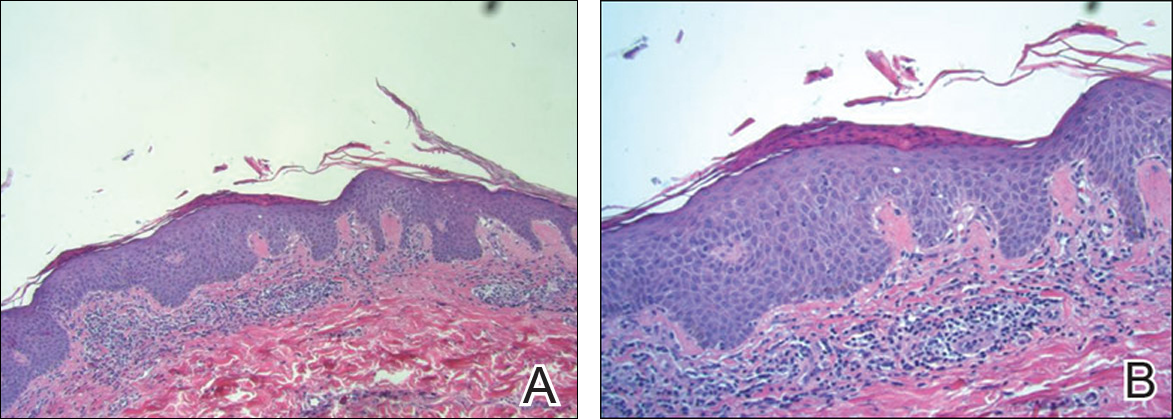

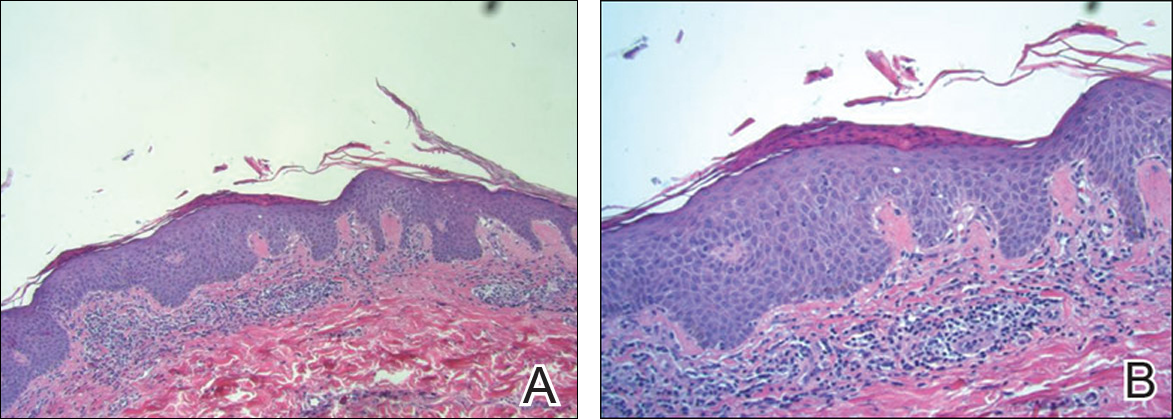

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

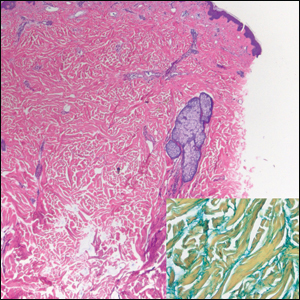

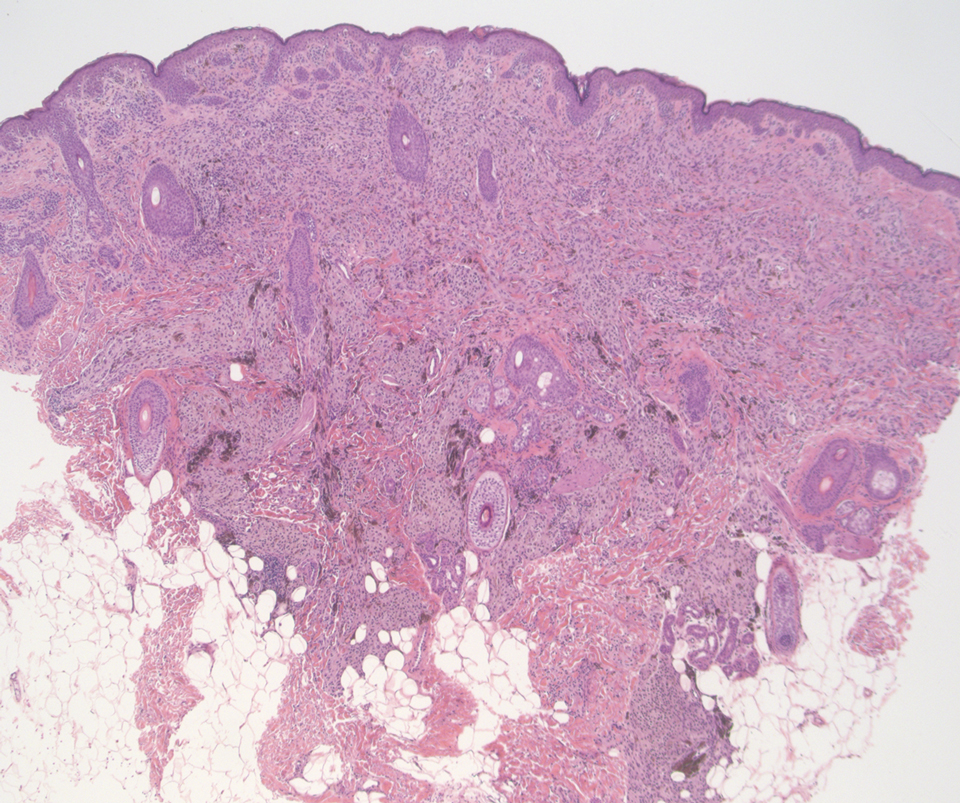

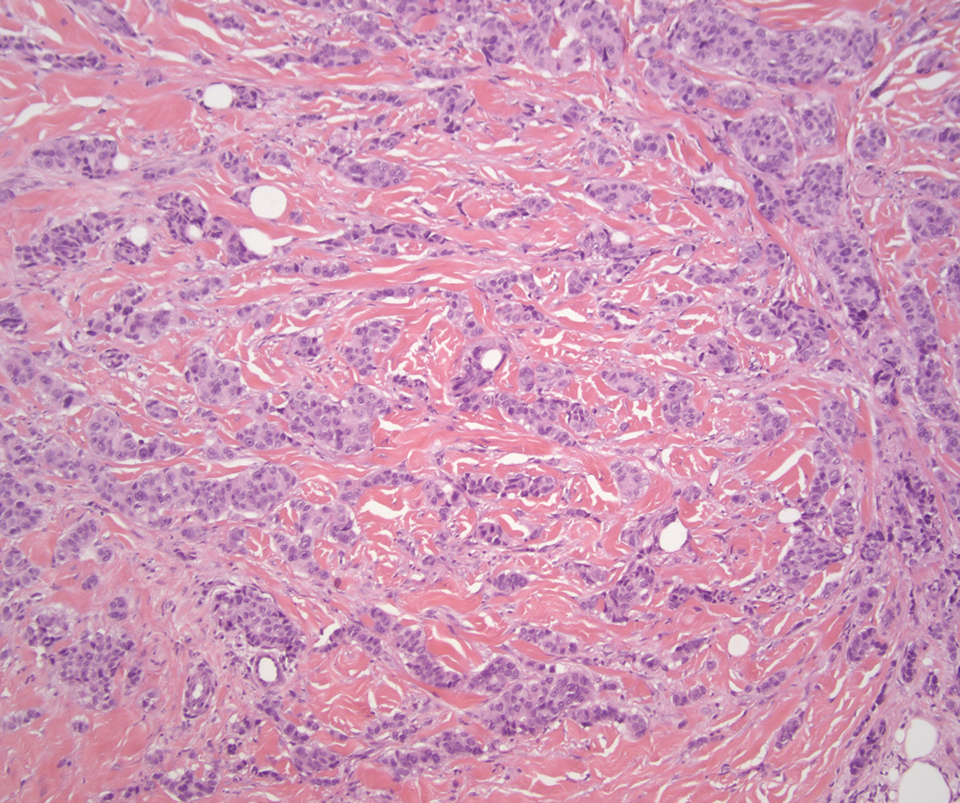

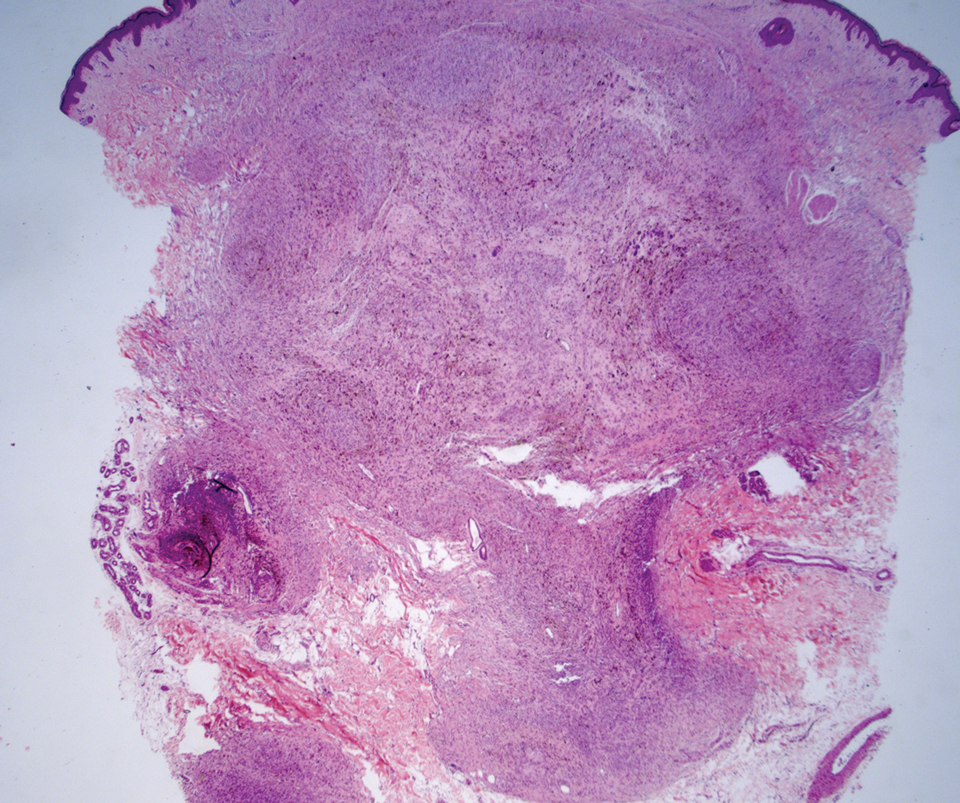

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

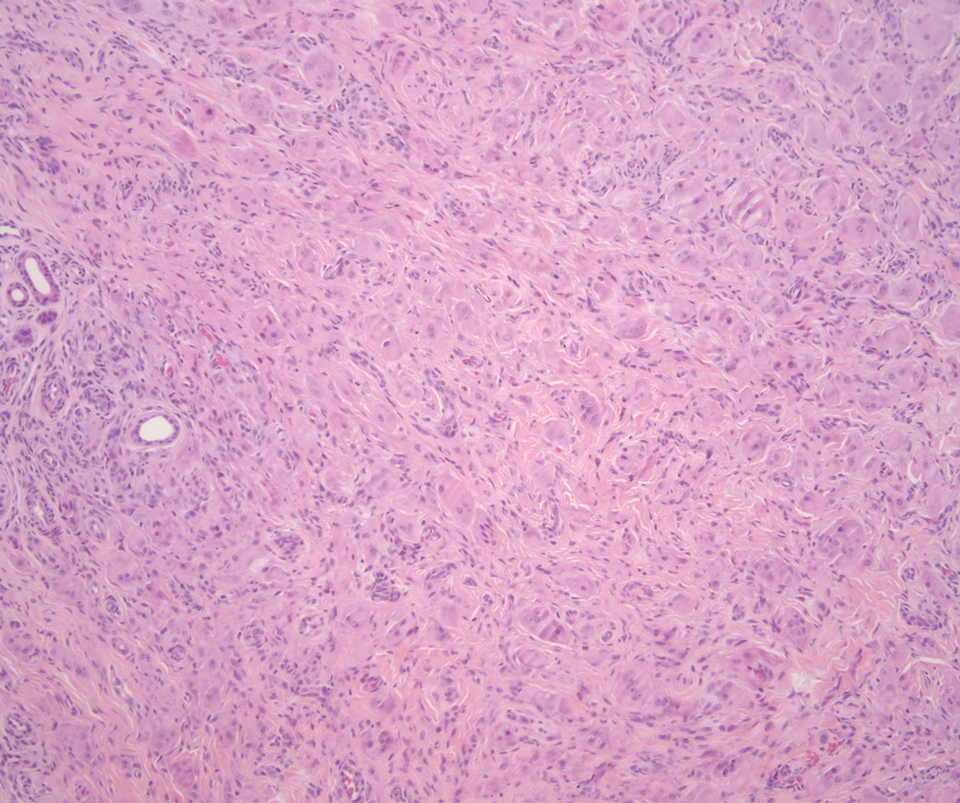

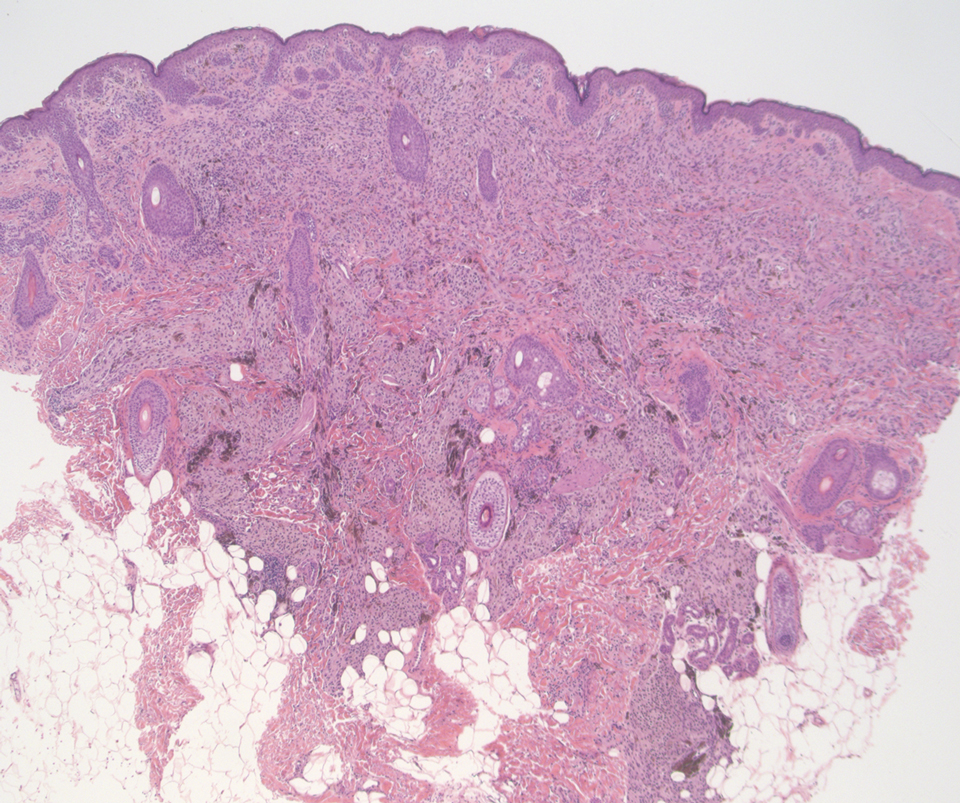

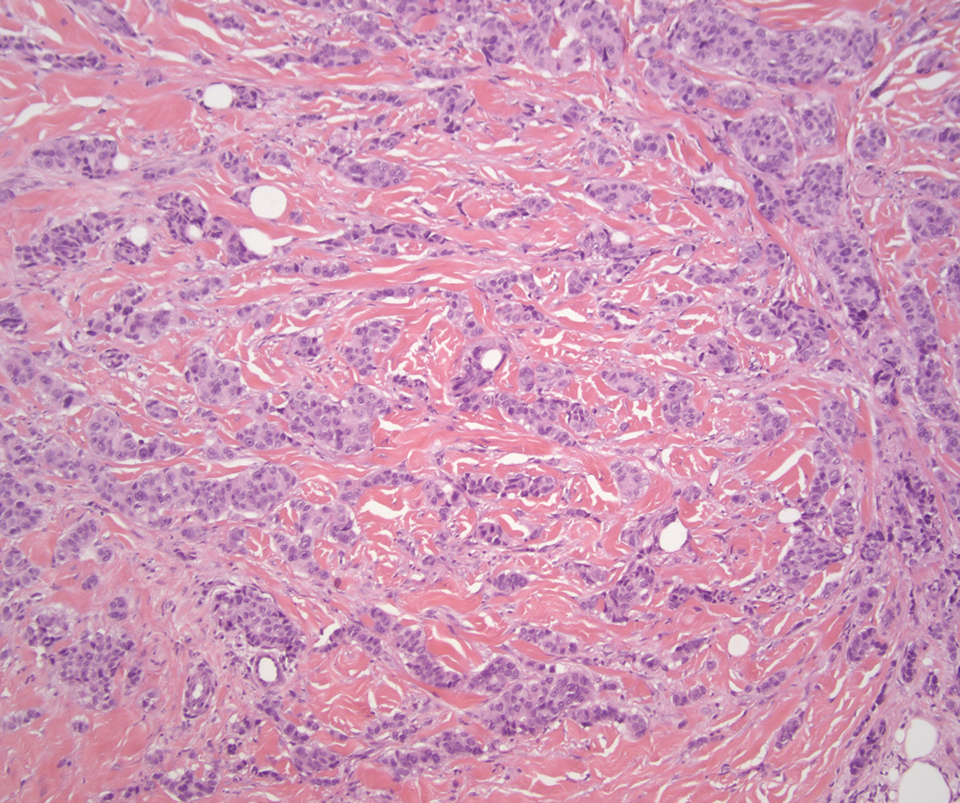

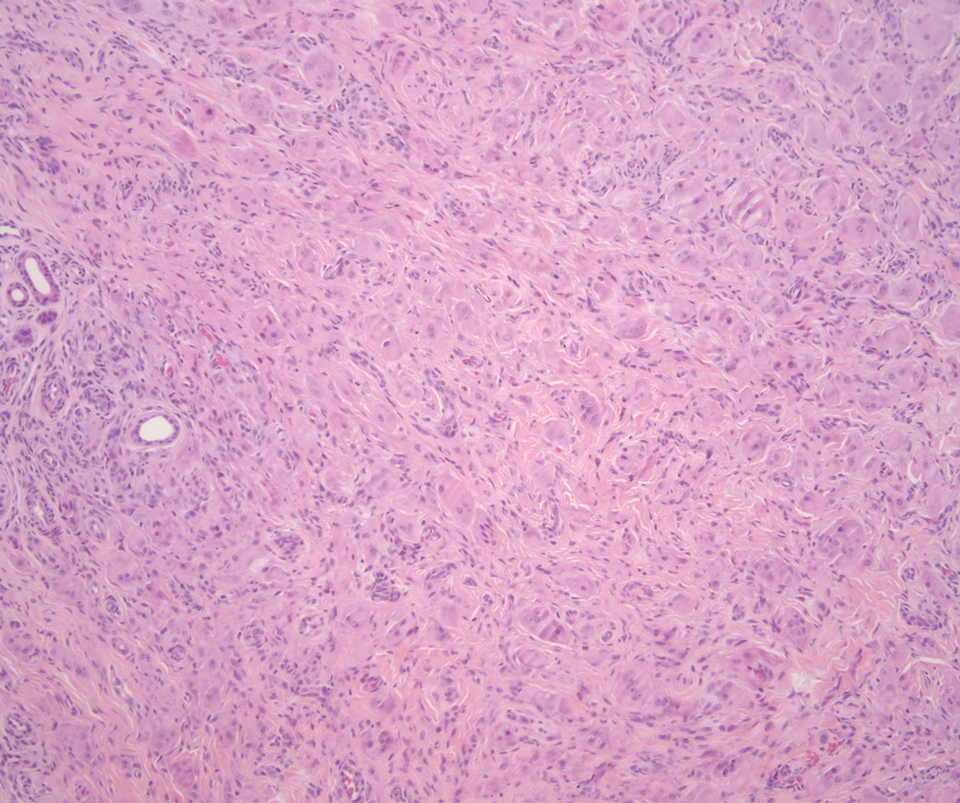

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

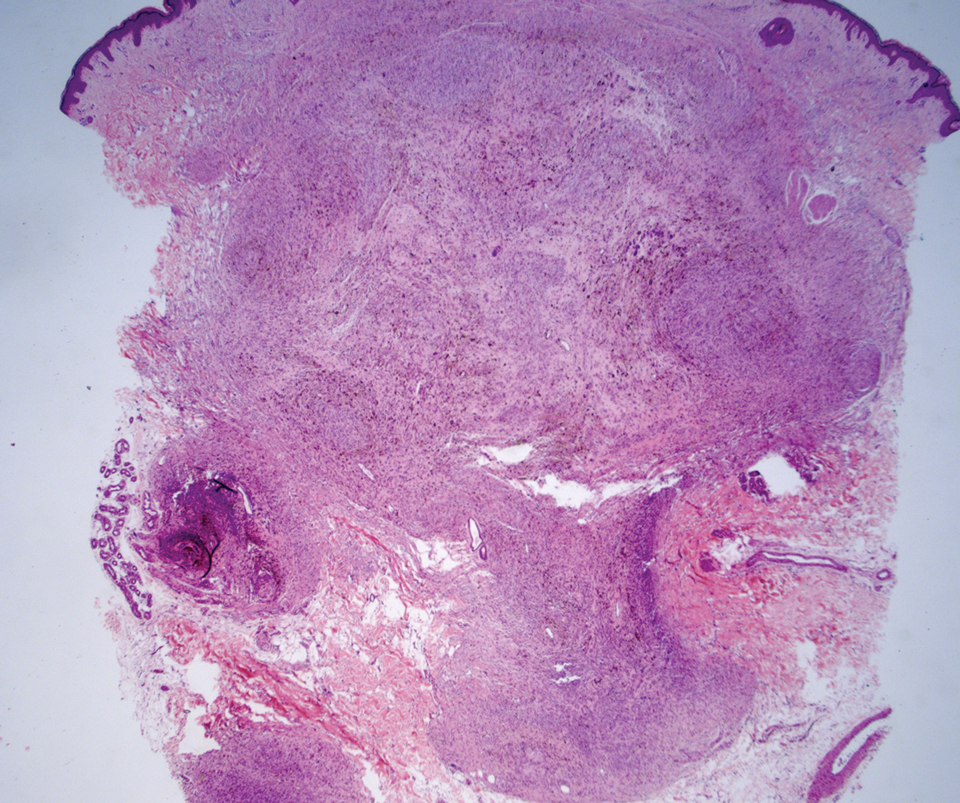

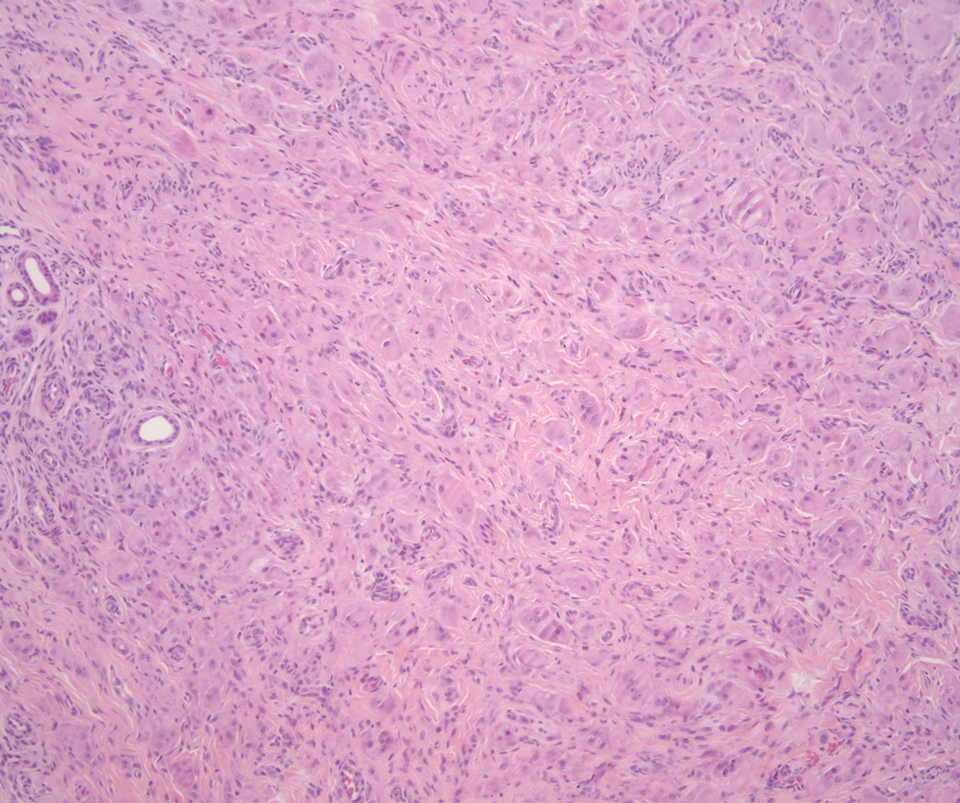

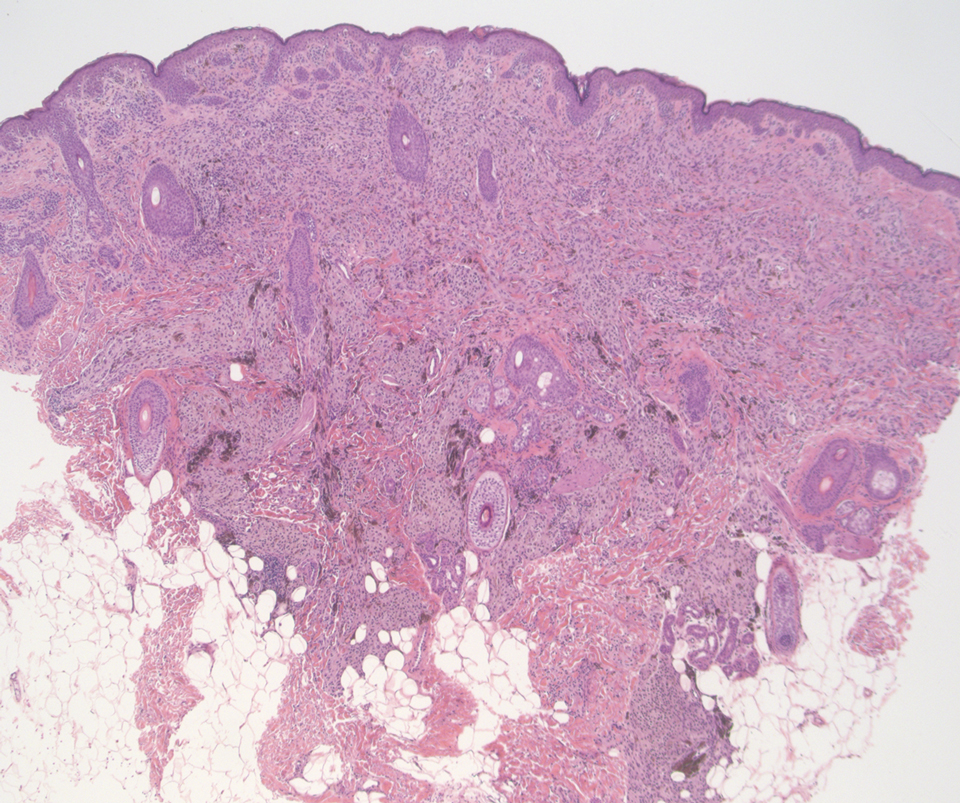

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

A 37-year-old woman with a history of fibrocystic breast disease and a family history of breast cancer presented with a light brown macule on the right upper arm of 10 years’ duration. The patient first noticed this macule 10 years prior; however, within the last 4 months she noticed a small amount of homogenous darkening and occasional pruritus. Physical examination revealed a 4.0-mm, light brown and pink macule on the right upper arm. Dermoscopy showed a homogenous pigment network with reticular lines and branched streaks centrally. No crystalline structures, milky red globules, or pseudopods were appreciated. A tangential shave biopsy was obtained and submitted for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Woody Erythematous Induration on the Posterior Neck

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

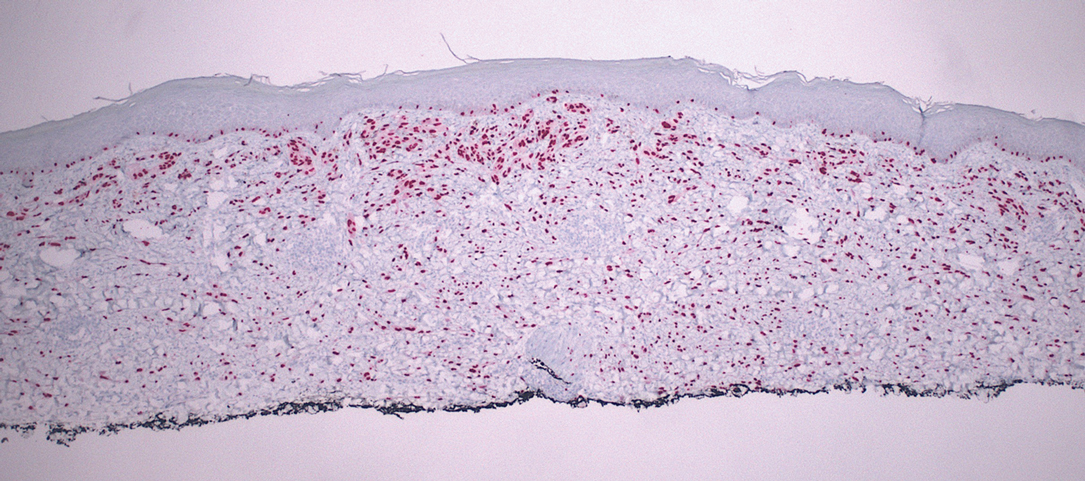

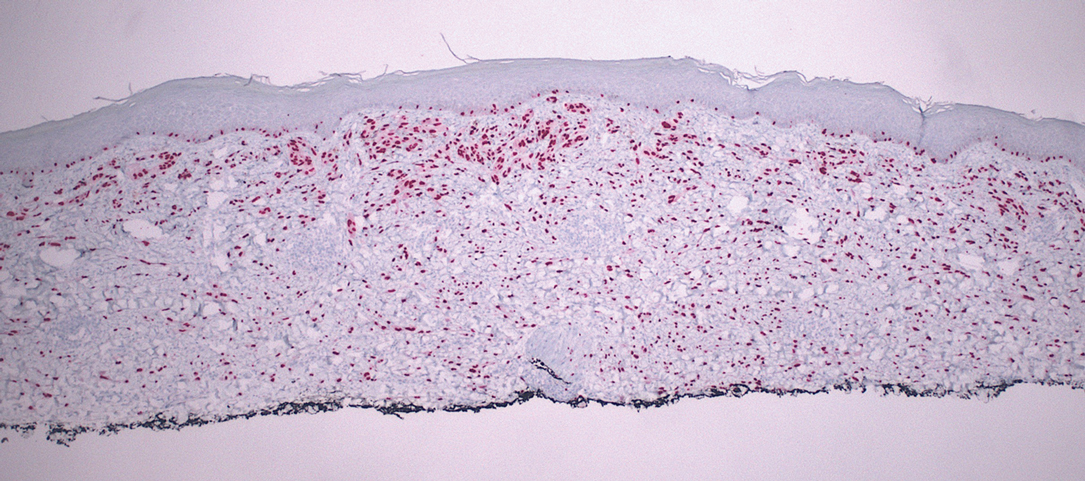

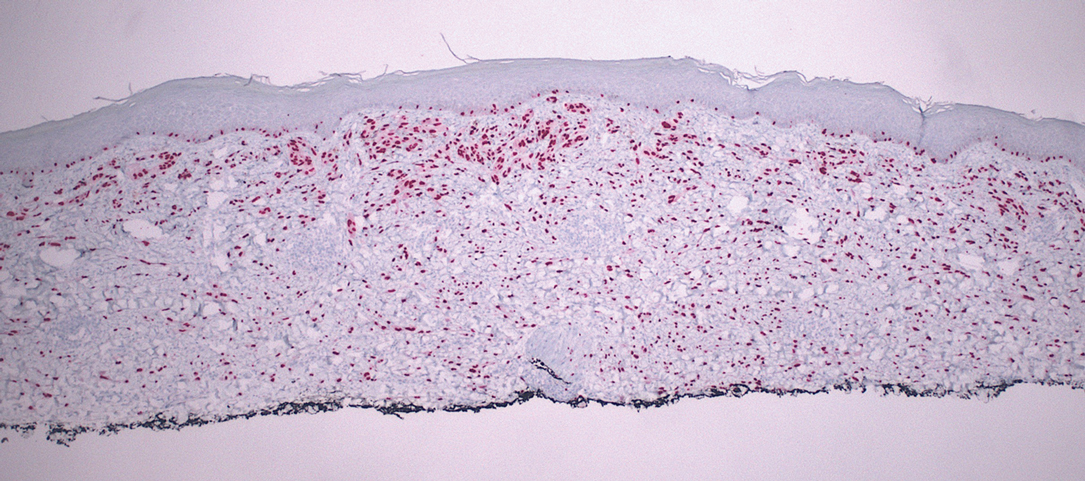

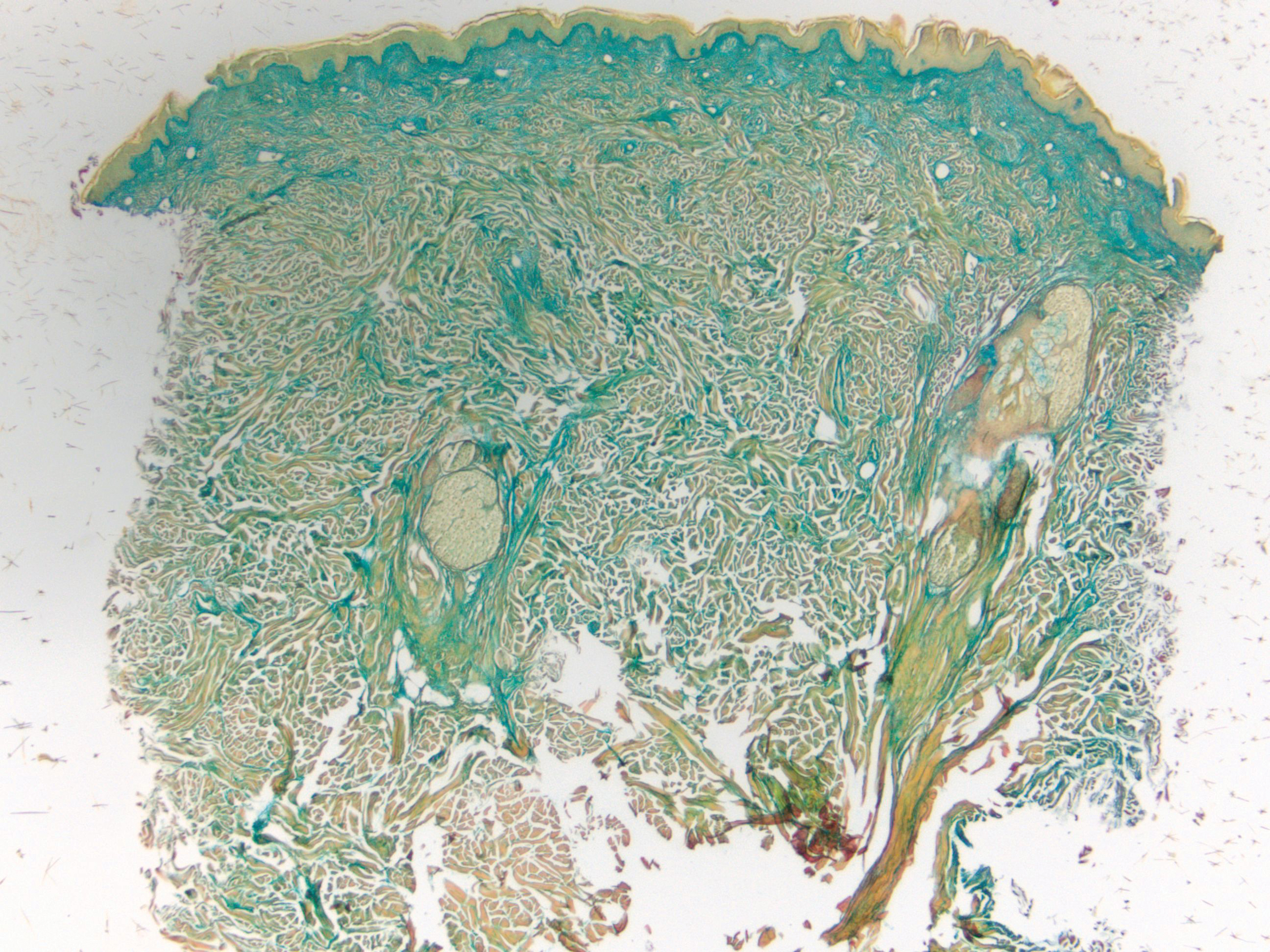

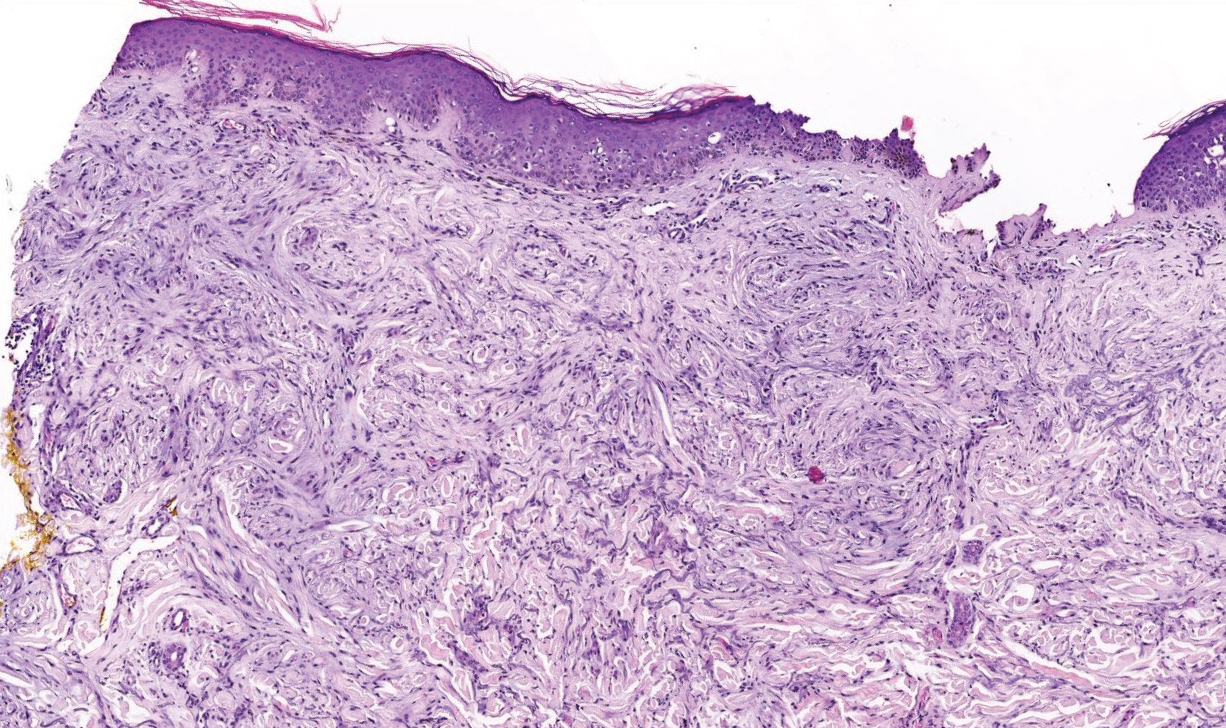

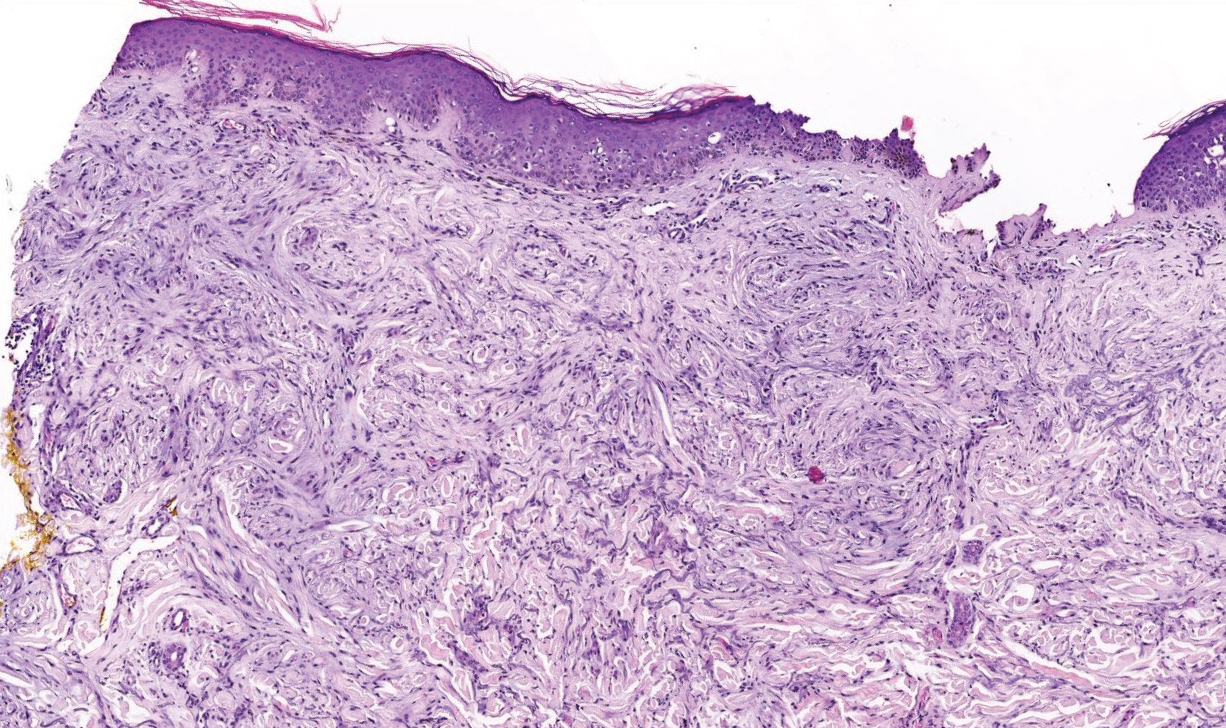

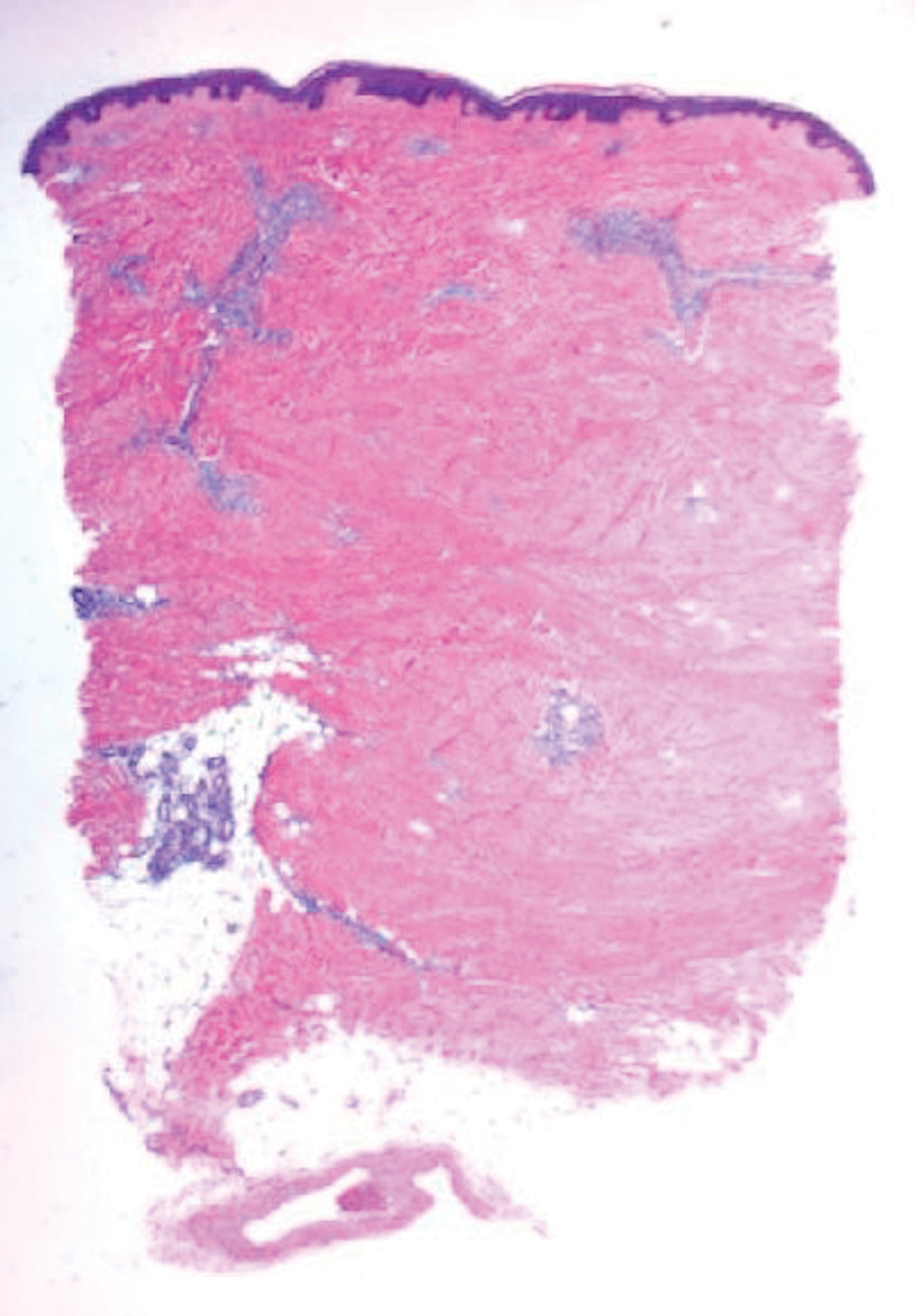

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

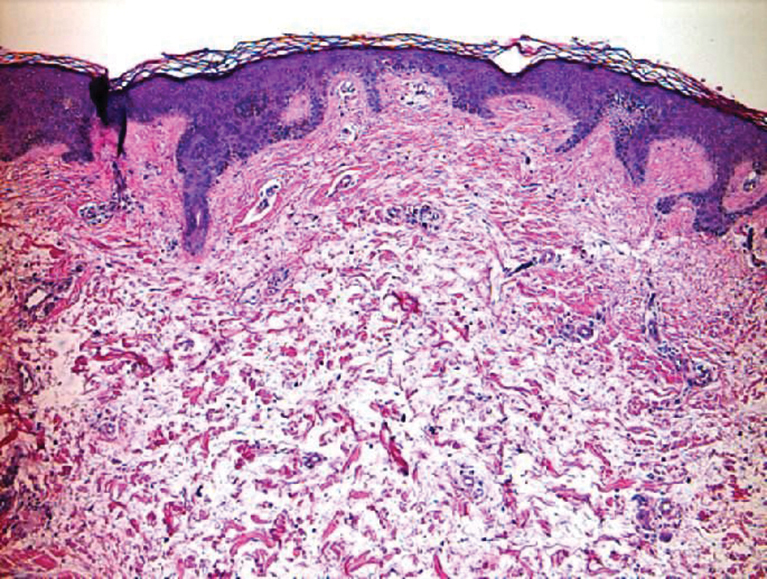

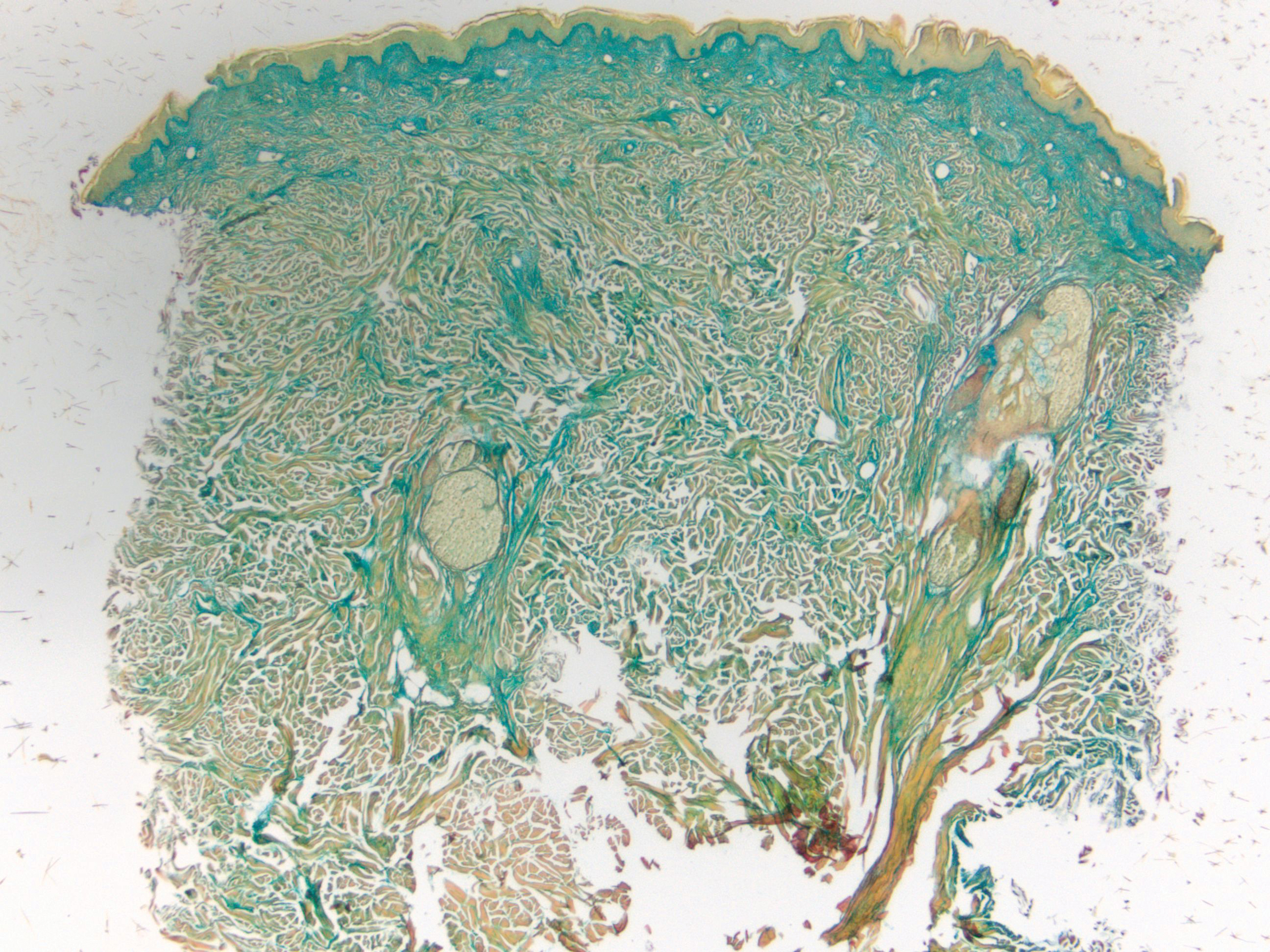

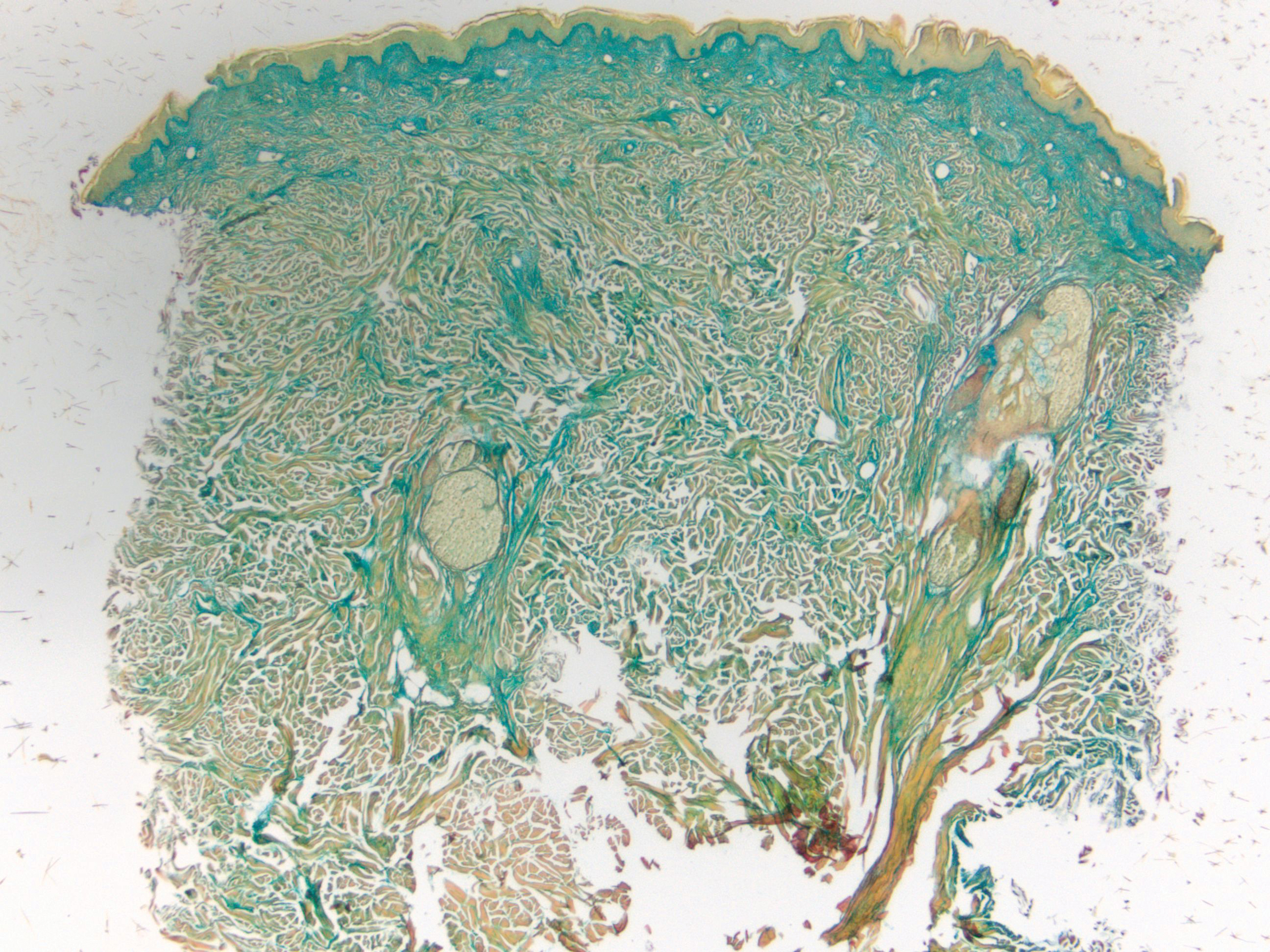

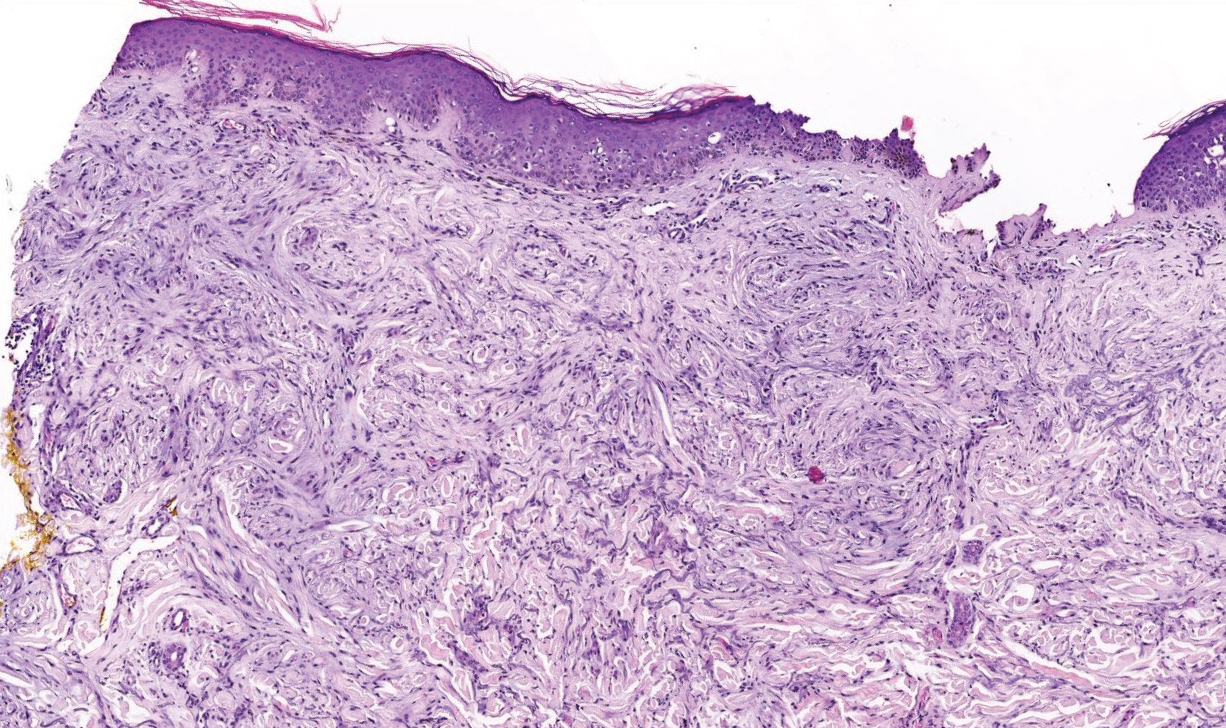

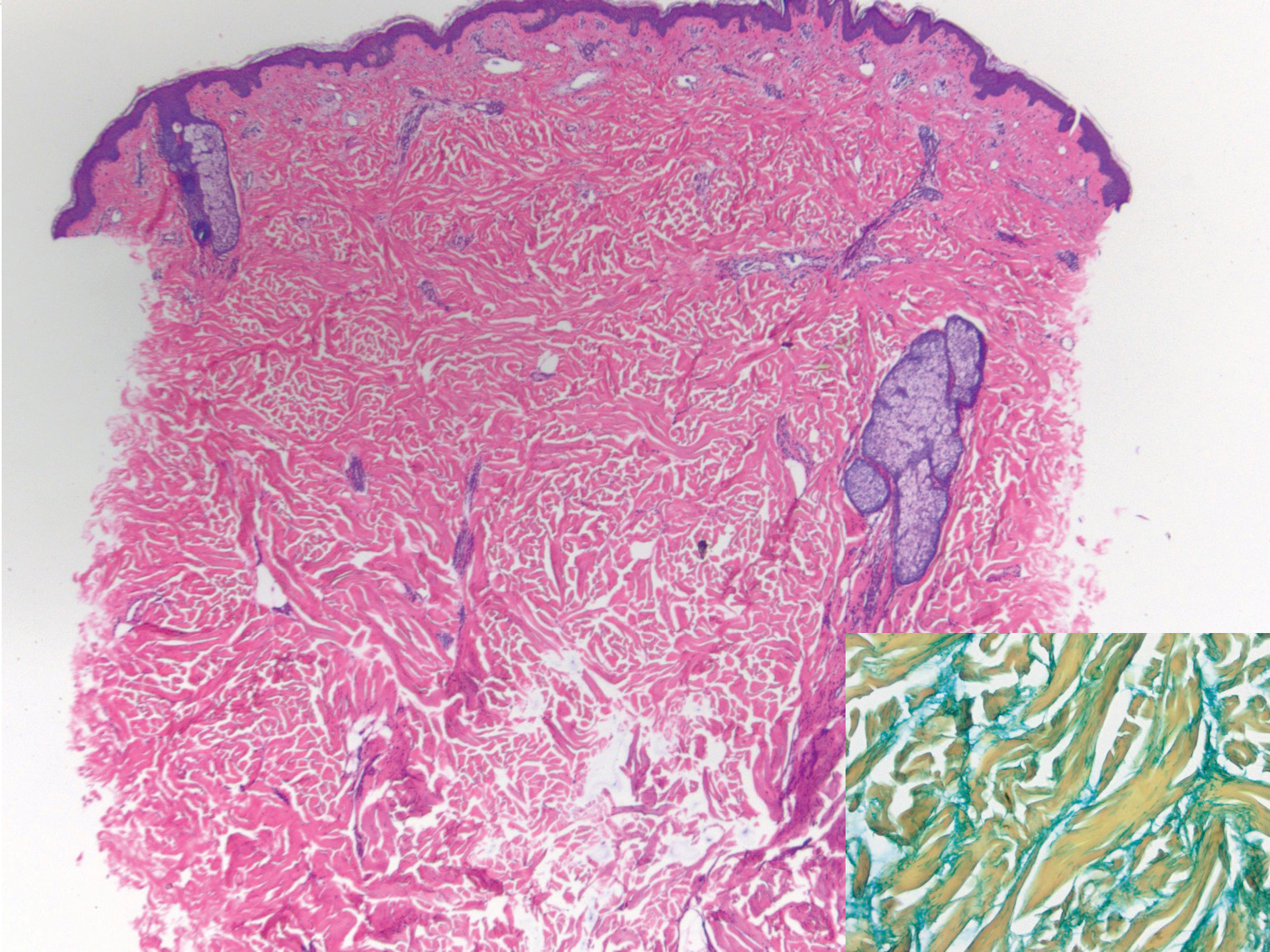

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

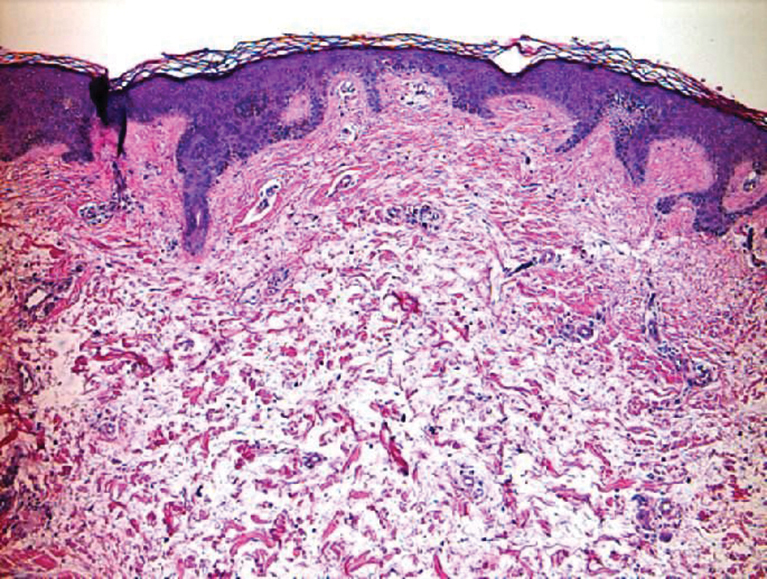

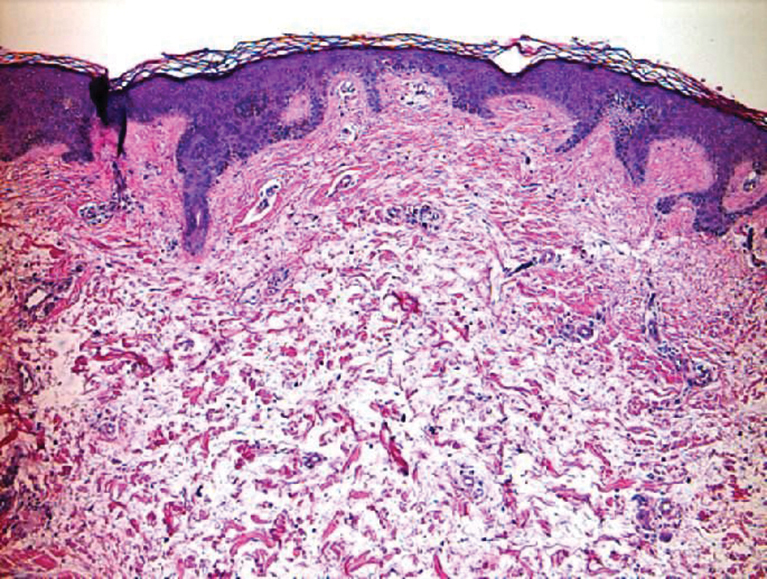

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

A 39-year-old white woman with a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis presented to the dermatology clinic with pain and thickened skin on the posterior neck of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient noted stiffness in the neck and shoulders but denied any pain, pruritus, fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, dysphagia, weight loss, or change in appetite. Physical examination revealed a woody indurated plaque with slight erythema that was present diffusely on the posterior neck and upper back. The patient reported that a recent complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel performed by her primary care physician were within reference range. Hemoglobin A1C was 8.6% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7%). A punch biopsy was performed.

Violaceous Patches on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

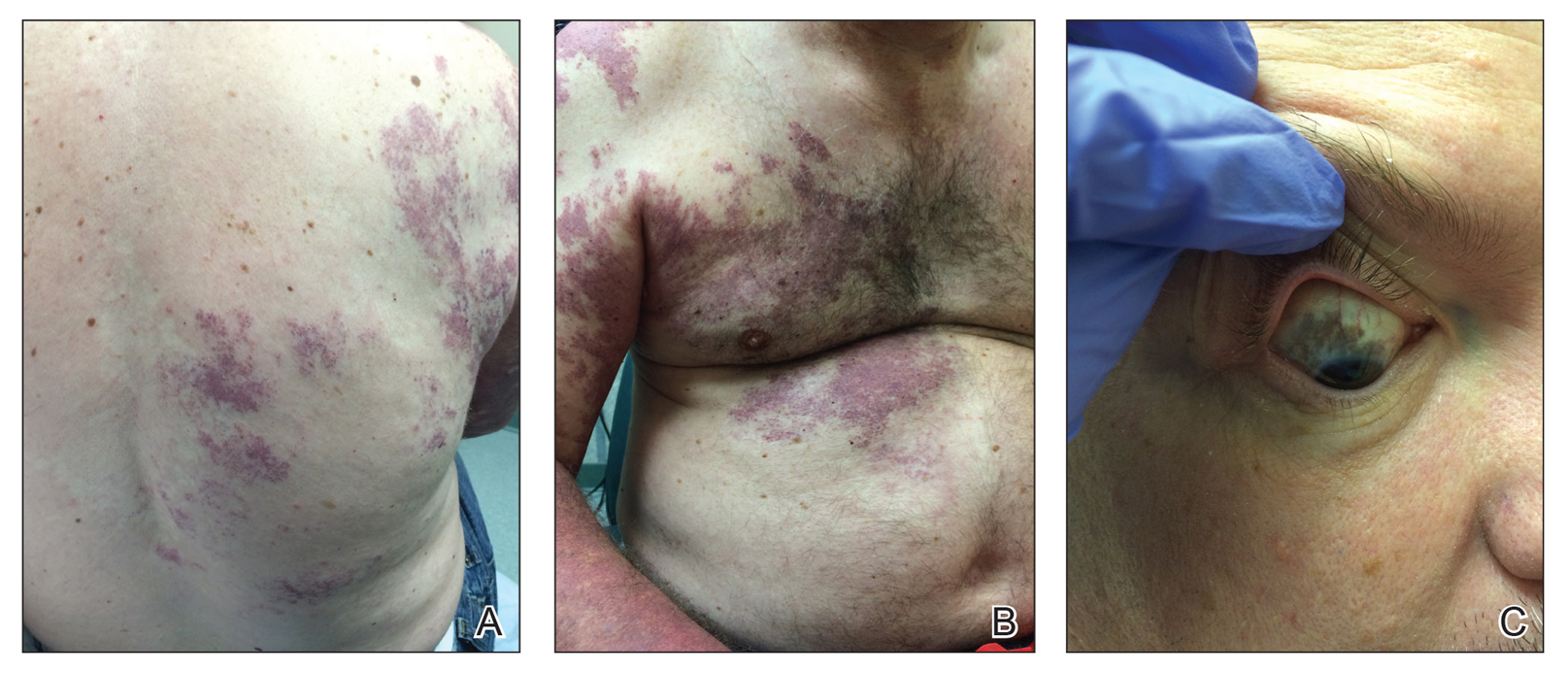

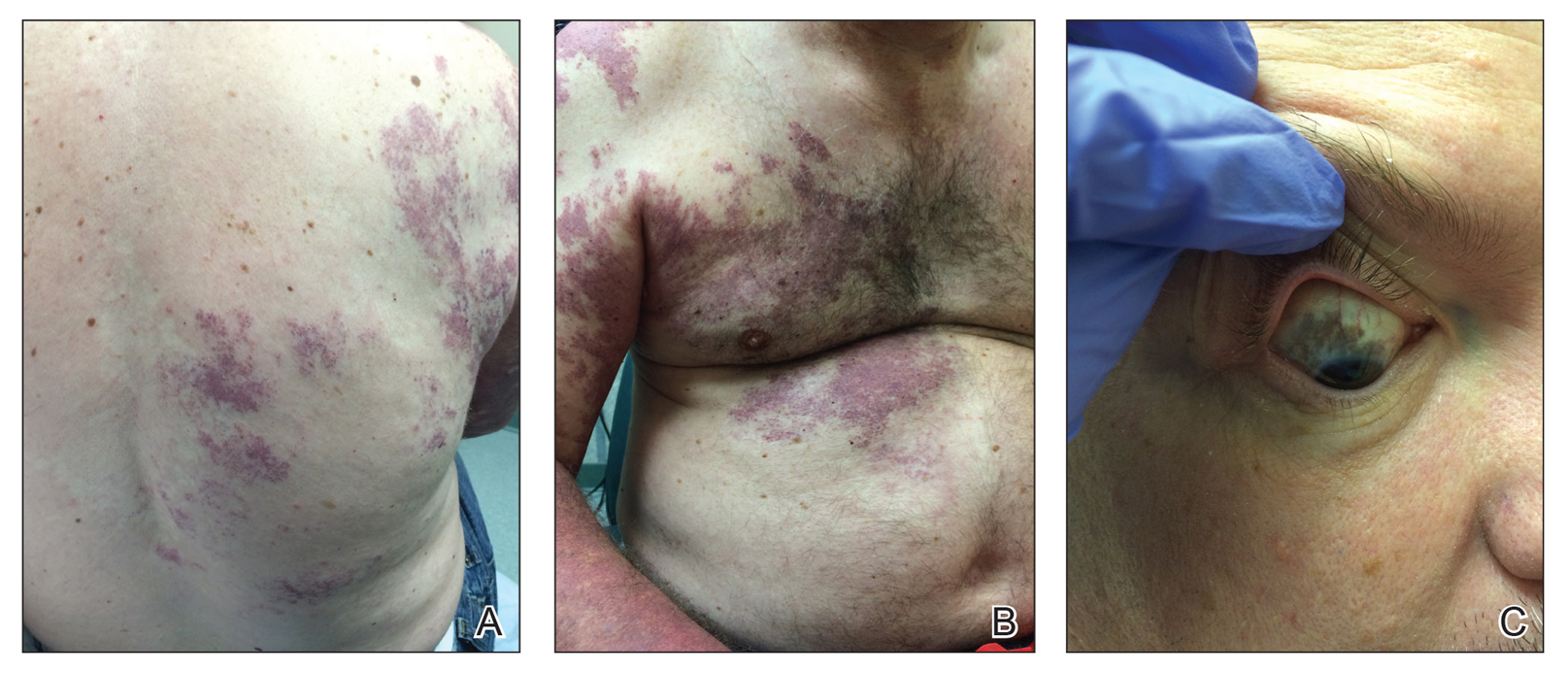

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

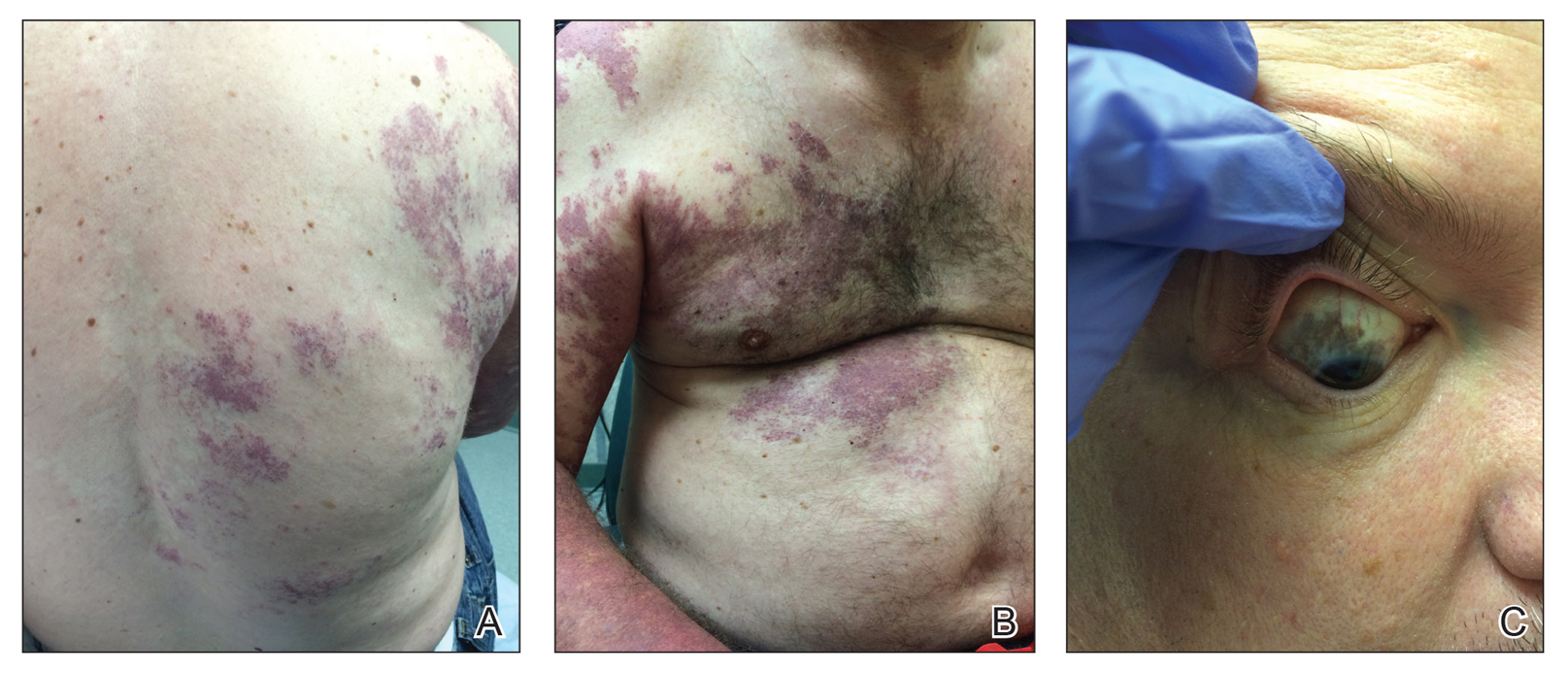

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

A 55-year-old man presented with red-violet patches on the right arm and chest that had been present since birth. The patches were asymptomatic and stable in size and shape. He denied any personal or family history of glaucoma or epilepsy. Physical examination demonstrated nonblanchable, violaceous to red patches on the right arm, back, and chest. No thrills or bruits were appreciable, and the right and left arms were of equal circumference and length. Further examination revealed hyperpigmented patches on the bilateral conjunctivae.

Pityriasis Lichenoides Chronica Presenting With Bilateral Palmoplantar Involvement

Pityriasis lichenoides is an uncommon, acquired, idiopathic, self-limiting skin disease that poses a challenge to patients and clinicians to diagnose and treat. Several variants exist including pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), and febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. Precise classification can be difficult due to an overlap of clinical and histologic features. The spectrum of this inflammatory skin disorder is characterized by recurrent crops of spontaneously regressing papulosquamous, polymorphic, and ulceronecrotic papules affecting the trunk and extremities. Pityriasis lichenoides is a monoclonal T-cell disorder that needs careful follow-up because it can progress, though rarely, to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In this case report we describe a patient with a rare presentation of PLC exhibiting bilateral palmoplantar involvement and mimicking psoriasis. We review the literature and discuss the clinical course, pathogenesis, and current treatment modalities of PLC.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented with a recurrent itchy rash on the legs, feet, hands, and trunk of several months’ duration. Her medical history included Helicobacter pylori–associated peptic ulcer disease and hypertension. She was not taking any prescription medications. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use or any personal or family history of skin disease. For many years she had lived part-time in Hong Kong, and she was concerned that her skin condition might be infectious or allergic in nature because she had observed similar skin lesions in Hong Kong natives who attributed the outbreaks of rash to “bad water.”

Physical examination revealed reddish brown crusted papules and plaques scattered bilaterally over the legs and feet (Figure 1); serpiginous scaly patches on the hips, thighs, and back; and thick hyperkeratotic psoriasiform plaques with yellow scale and crust on the palms and soles (Figure 2). The nails and oral mucosa were unaffected. Histopathologic evaluation of the lesions obtained from the superior aspect of the thigh showed parakeratotic scale and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis consistent with PLC (Figure 3).

The patient was started on tetracycline 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and on narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) therapy at 350 J/cm2 with incremental increases of 60 J/cm2 at each treatment for a maximum dose of 770 J/cm2. She received 9 treatments in total over 1 month and noted some improvement in overall appearance of the lesions, mostly over the trunk and extremities. Palmoplantar lesions were resistant to treatment. Therapy with NB-UVB was discontinued, as the patient had to return to Hong Kong. Given the brief course of NB-UVB therapy, it was hard to assess why the palmoplantar lesions failed to respond to treatment.

Comment

Subtypes

Pityriasis lichenoides is a unique inflammatory disorder that usually presents with guttate papules in various stages of evolution ranging from acute hemorrhagic, vesicular, or ulcerated lesions to chronic pink papules with adherent micalike scale. Two ends of the spectrum are PLEVA and PLC. Papule distribution often is diffuse, affecting both the trunk and extremities, but involvement can be confined to the trunk producing a central distribution or restricted to the extremities giving a peripheral pattern. A purely acral localization is uncommon and rarely has been documented in the literature.1

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta typically presents with an acute polymorphous eruption of 2- to 3-mm erythematous macules that evolve into papules with a fine, micaceous, centrally attached scale. The center of the papule then undergoes hemorrhagic necrosis, becomes ulcerated with reddish brown crust, and may heal with a varioliform scar. Symptoms may include a burning sensation and pruritus. Successive crops may persist for weeks, months, and sometimes years.2

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is an acute and severe generalized eruption of ulceronecrotic plaques. Extensive painful necrosis of the skin may follow and there is an increased risk for secondary infection.2 Systemic symptoms may include fever, sore throat, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease has a mortality rate of 25% and should be treated as a dermatologic emergency.2

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica has a more gradual presentation and indolent course than PLEVA. It most commonly presents as small asymptomatic polymorphous red-brown maculopapules with micaceous scale.3 Papules spontaneously flatten over a few weeks. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation may persist once the lesions resolve. Similar to PLEVA, PLC has a relapsing course but with longer periods of remission. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica usually involves the trunk and proximal extremities, but acral distributions, as in our case, have been described. This rare variant of pityriasis lichenoides may be underrecognized and underdiagnosed due to its resemblance to psoriasis.1

The prevalence and incidence of PLC in the general population is unknown. There appears to be no predominance based on gender, ethnicity, or geographical location, and it occurs in both children and adults. One study showed the average age to be 29 years.2

Etiology

The cause of pityriasis lichenoides is unknown, but there are 3 popular theories regarding its pathogenesis: a hypersensitivity response due to an infectious agent, an inflammatory response to a T-cell dyscrasia, or an immune complex–mediated hypersensitivity vasculitis.2 The theory of an infectious cause has been proposed due to reports of disease clustering in families and communities.2,3 Elevated titers of certain pathogens and clearing of the disease after pathogen-specific treatment also have been reported. Possible triggers cited in the literature include the Epstein-Barr virus, Toxoplasma gondii, parvovirus B19, adenovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, freeze-dried live attenuated measles vaccine, Staphylococcus aureus, and group A β-hemolytic streptococci.2,3

Some reported cases of pityriasis lichenoides have demonstrated T-cell clonality. Weinberg et al4 found a significantly higher number of clonal T cells in PLEVA than in PLC (P=.008) and hypothesized that PLEVA is actually a benign clonal T-cell disorder arising from a specific subset of T cells in PLC. Malignant transformation of pityriasis lichenoides has been reported but is rare.3

Differential Diagnosis

Historically, pityriasis lichenoides has been confused with many other dermatoses. With palmoplantar involvement, consider other papulosquamous disorders such as palmoplantar psoriasis, lichen planus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, vasculitis, and secondary syphilis. Rule out alternative diagnoses with histologic examination; assessments of nails, oral mucosa, joints, and constitutional symptoms; and laboratory testing.

Histopathology

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and PLC are similar with subtle and gradually evolving differences, supporting the notion that these disorders are polar ends of the same disease spectrum.2 Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta typically produces a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate composed of CD8+ T cells and histiocytes most concentrated along the basal layer with lymphocytic exocytosis into the epidermis and perivascular inflammation. The epidermis also demonstrates spongiosis, necrosis and apoptosis of keratinocytes, neutrophilic inclusions, vacuolar degeneration, intraepidermal vesicles and ulceration, and focal parakeratosis with scale and crust. In contrast, PLC is less exaggerated than PLEVA with a superficial bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in which CD4+ T cells predominate with minimal perivascular involvement. Immunohistochemical studies reveal that CD8+ cells predominate in PLEVA, while CD4+ cells predominate in PLC. Staining for HLA-DR–positive keratinocytes yields stronger and more diffuse findings in PLEVA than in PLC and is considered a marker for the former.2

Treatment

There is no standard treatment of pityriasis lichenoides. However, combination therapy is considered the best approach. To date, phototherapy has been the most effective modality and is considered a first-line treatment of PLC. Variants of phototherapy include UVB, NB-UVB, psoralen plus UVA, and UVA1.5 One study showed UVA1 (340–400 nm) treatment to be effective and well tolerated at a medium dose of 60 J/cm2.6 Narrowband UVB has become a well-used phototherapy for a variety of skin conditions including pityriasis lichenoides. In a study by Aydogan et al,5 NB-UVB was safe and effective for the management of PLEVA and PLC. The authors also argue that it has added advantages over other phototherapies, including a more immunosuppressive effect on lymphoproliferation that causes a greater depletion of T cells in skin lesions, possibly due to its deeper dermal penetration compared with broadband UVB. Narrowband UVB also is safe in children.5 Tapering of phototherapy has been recommended to prevent relapses.3