User login

Blistering Disease During the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C With Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir (FULL)

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most common type of porphyria. The accumulation of porphyrin in various organ systems results from a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD).1-3 Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes a hepatic decrease in hepcidin production, resulting in increased iron absorption. Iron loading and increased oxidative stress in the liver leads to nonporphyrin inhibition of UROD production and to oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins.4 This in turn leads to accumulation of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites that can be detected in urine.4

Signs of PCT include blisters, vesicles, and possibly milia developing on sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, forearms, and dorsal hands.4 Case reports have demonstrated a resolution of PCT in patients with chronic HCV with treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), such as ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.1,3 However, here we present 2 cases of patients who developed blistering diseases during treatment of chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Neither demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms during the treatment regimen.

Cases

Patient 1

A 63-year-old white male with a history of chronic HCV (genotype 1a), bipolar disorder, hyperlipidemia, tobacco dependence, and cirrhosis (F4 by elastography) presented with minimally to moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands that had developed around weeks 8 to 9 of treatment with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The patient reported that no new blisters had appeared following completion of 12 weeks of treatment and that his current blisters were in various stages of healing. He reported alcohol use of 1 to 2 twelve-ounce beers daily and no history of dioxin exposure. His medications included doxepin, hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide, quetiapine, folic acid, and thiamine. His hepatitis C viral load was 440,000 IU/mL prior to treatment. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron level was 135 µg/dL, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) was 323 µg/dL, and ferritin was 299.0 ng/mL. His HFE

A physical examination on presentation revealed erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral dorsal hands (Figure).

At the 4-month follow-up, the patient reported no new blister formations. A physical examination revealed well-healed scars and several clustered milia on bilateral dorsal hands with no active vesicles or bullae noted.

Patient 2

An African American male aged 63 years presented with a 1-month history of moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands during treatment of chronic HCV (genotype 1a) with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. His medical history included gout, tobacco and alcohol addiction, osteoarthritis, and hepatic fibrosis (F3 by elastography). The patient’s medications included allopurinol, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide. He reported no history of dioxin exposure. On the day of presentation, he was on week 9 of the 12-week treatment ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimen. Laboratory results included an initial HCV viral load of 1,618,605 IU/mL. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron was 191 µg/dL, TIBC 388 µg/dL, and ferritin 459.0 ng/mL. After 4 weeks of treatment, the patient’s hepatitis C viral load was undetectable.

A physical examination revealed several resolving erosions to his bilateral dorsal hands, some of which had overlying crusting along with one small hemorrhagic vesicle on the right dorsal hand. A punch biopsy of the hemorrhagic vesicle was performed and demonstrated a cell-poor subepidermal blister with festooning of the dermal papilla. A direct immunofluorescence study showed immunoglobulin (Ig) G fluorescence along the dermal-epidermal junction and within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. Weak IgM and C3 fluorescence also was noted within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. All of the patient findings and history were consistent with PCT, although pseudo-PCT also was a consideration. A 24-hour urine sample yielded negative results for porphobilinogen. Urine porphyrin test results were not available, leading to a presumptive histological diagnosis of PCT.

The patient completed 11 of the prescribed 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The blisters resolved shortly thereafter.

Discussion

PCT has a well-established association with chronic HCV infection.4 We present 2 cases of a blistering disease clinically and histologically compatible with PCT that developed in patients only after initiation of treatment for chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. One case was confirmed as PCT on the basis of compatible histopathologic findings and a urine porphyrin assay that showed elevated levels of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites. The second case was clinically and histologically suggestive of PCT but not confirmed by urine porphyrin testing. In both patients, after 8 to 9 weeks of a 12-week course of antiviral therapy, the blistering lesions were noted but appeared to be resolving, and no new lesions were noted after discontinuation of therapy. It appeared that the antiviral treatment temporally triggered the initiation of the blistering skin disease, and as the chronic HCV infection cleared after treatment, the blistering lesions also began to resolve.

Mechanistically, it is known that the virally-induced hepatic damage leads to inhibition of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, and the subsequent oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins. Cofactors such as HIV infection also may contribute to development of PCT.5

De novo PCT has been documented during therapy using interferon and ribavirin.6 The hemolytic anemia and increased hepatic iron were implicated as potential etiologies.6 Patients with HCV and PCT treated with the newer direct-acting antiviral therapies have been described to have experienced improvement in PCT symptoms.3

Although there were rare reports of deterioration in renal and liver function,7 reactivation of HBV infection,8 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome9 with antiviral therapy, these complications were not observed in these patients. Both patients also had successful resolution of HCV infection, and by completion of the antiviral therapy, the blistering also resolved.

Conclusion

PCT is an extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection. Health care providers should be aware of the association of chronic HCV infection with PCT. The findings of PCT should not result in the delay or discontinuation of antiviral therapy.

1. Combalia A, To-Figueras J, Laguno M, Martinez-Rebollar M, Aguilera P. Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus induce a rapid clinical and biochemical remission of porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):e183-e184.

2. Younossi Z, Park H, Henry L, Adeyemi A, Stepanova M. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C: a meta-analysis of prevalence, quality of life, and economic burden. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1599-1608.

3. Tong Y, Song YK, Tyring S. Resolution of porphyria cutanea tarda in patients with hepatitis C following ledipasvir/sofosbuvir combination therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1393-1395.

4. Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky H. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int. 2012;32(6):880-893.

5. Quansah R, Cooper CJ, Said S, Bizet J, Paez D, Hernandez GT. Hepatitis C- and HIV-induced porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:35-40.

6. Azim J, McCurdy H, Moseley RH. Porphyria cutanea tarda as a complication of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(38):5913-5915.

7. Ahmed M. Harvoni-induced deterioration of renal and liver function. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2017;2(3):555588.

8. De Monte A, Courion J, Anty R, et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in adults infected with hepatitis C virus: reactivation of hepatitis B virus coinfection as a further challenge. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:27-30.

9. Verma N, Singh S, Sawatkar G, Singh V. Sofosbuvir induced Steven Johnson Syndrome in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2017;2(1):16-20.

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most common type of porphyria. The accumulation of porphyrin in various organ systems results from a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD).1-3 Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes a hepatic decrease in hepcidin production, resulting in increased iron absorption. Iron loading and increased oxidative stress in the liver leads to nonporphyrin inhibition of UROD production and to oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins.4 This in turn leads to accumulation of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites that can be detected in urine.4

Signs of PCT include blisters, vesicles, and possibly milia developing on sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, forearms, and dorsal hands.4 Case reports have demonstrated a resolution of PCT in patients with chronic HCV with treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), such as ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.1,3 However, here we present 2 cases of patients who developed blistering diseases during treatment of chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Neither demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms during the treatment regimen.

Cases

Patient 1

A 63-year-old white male with a history of chronic HCV (genotype 1a), bipolar disorder, hyperlipidemia, tobacco dependence, and cirrhosis (F4 by elastography) presented with minimally to moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands that had developed around weeks 8 to 9 of treatment with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The patient reported that no new blisters had appeared following completion of 12 weeks of treatment and that his current blisters were in various stages of healing. He reported alcohol use of 1 to 2 twelve-ounce beers daily and no history of dioxin exposure. His medications included doxepin, hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide, quetiapine, folic acid, and thiamine. His hepatitis C viral load was 440,000 IU/mL prior to treatment. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron level was 135 µg/dL, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) was 323 µg/dL, and ferritin was 299.0 ng/mL. His HFE

A physical examination on presentation revealed erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral dorsal hands (Figure).

At the 4-month follow-up, the patient reported no new blister formations. A physical examination revealed well-healed scars and several clustered milia on bilateral dorsal hands with no active vesicles or bullae noted.

Patient 2

An African American male aged 63 years presented with a 1-month history of moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands during treatment of chronic HCV (genotype 1a) with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. His medical history included gout, tobacco and alcohol addiction, osteoarthritis, and hepatic fibrosis (F3 by elastography). The patient’s medications included allopurinol, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide. He reported no history of dioxin exposure. On the day of presentation, he was on week 9 of the 12-week treatment ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimen. Laboratory results included an initial HCV viral load of 1,618,605 IU/mL. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron was 191 µg/dL, TIBC 388 µg/dL, and ferritin 459.0 ng/mL. After 4 weeks of treatment, the patient’s hepatitis C viral load was undetectable.

A physical examination revealed several resolving erosions to his bilateral dorsal hands, some of which had overlying crusting along with one small hemorrhagic vesicle on the right dorsal hand. A punch biopsy of the hemorrhagic vesicle was performed and demonstrated a cell-poor subepidermal blister with festooning of the dermal papilla. A direct immunofluorescence study showed immunoglobulin (Ig) G fluorescence along the dermal-epidermal junction and within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. Weak IgM and C3 fluorescence also was noted within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. All of the patient findings and history were consistent with PCT, although pseudo-PCT also was a consideration. A 24-hour urine sample yielded negative results for porphobilinogen. Urine porphyrin test results were not available, leading to a presumptive histological diagnosis of PCT.

The patient completed 11 of the prescribed 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The blisters resolved shortly thereafter.

Discussion

PCT has a well-established association with chronic HCV infection.4 We present 2 cases of a blistering disease clinically and histologically compatible with PCT that developed in patients only after initiation of treatment for chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. One case was confirmed as PCT on the basis of compatible histopathologic findings and a urine porphyrin assay that showed elevated levels of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites. The second case was clinically and histologically suggestive of PCT but not confirmed by urine porphyrin testing. In both patients, after 8 to 9 weeks of a 12-week course of antiviral therapy, the blistering lesions were noted but appeared to be resolving, and no new lesions were noted after discontinuation of therapy. It appeared that the antiviral treatment temporally triggered the initiation of the blistering skin disease, and as the chronic HCV infection cleared after treatment, the blistering lesions also began to resolve.

Mechanistically, it is known that the virally-induced hepatic damage leads to inhibition of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, and the subsequent oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins. Cofactors such as HIV infection also may contribute to development of PCT.5

De novo PCT has been documented during therapy using interferon and ribavirin.6 The hemolytic anemia and increased hepatic iron were implicated as potential etiologies.6 Patients with HCV and PCT treated with the newer direct-acting antiviral therapies have been described to have experienced improvement in PCT symptoms.3

Although there were rare reports of deterioration in renal and liver function,7 reactivation of HBV infection,8 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome9 with antiviral therapy, these complications were not observed in these patients. Both patients also had successful resolution of HCV infection, and by completion of the antiviral therapy, the blistering also resolved.

Conclusion

PCT is an extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection. Health care providers should be aware of the association of chronic HCV infection with PCT. The findings of PCT should not result in the delay or discontinuation of antiviral therapy.

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most common type of porphyria. The accumulation of porphyrin in various organ systems results from a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD).1-3 Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes a hepatic decrease in hepcidin production, resulting in increased iron absorption. Iron loading and increased oxidative stress in the liver leads to nonporphyrin inhibition of UROD production and to oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins.4 This in turn leads to accumulation of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites that can be detected in urine.4

Signs of PCT include blisters, vesicles, and possibly milia developing on sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, forearms, and dorsal hands.4 Case reports have demonstrated a resolution of PCT in patients with chronic HCV with treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), such as ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.1,3 However, here we present 2 cases of patients who developed blistering diseases during treatment of chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Neither demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms during the treatment regimen.

Cases

Patient 1

A 63-year-old white male with a history of chronic HCV (genotype 1a), bipolar disorder, hyperlipidemia, tobacco dependence, and cirrhosis (F4 by elastography) presented with minimally to moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands that had developed around weeks 8 to 9 of treatment with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The patient reported that no new blisters had appeared following completion of 12 weeks of treatment and that his current blisters were in various stages of healing. He reported alcohol use of 1 to 2 twelve-ounce beers daily and no history of dioxin exposure. His medications included doxepin, hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide, quetiapine, folic acid, and thiamine. His hepatitis C viral load was 440,000 IU/mL prior to treatment. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron level was 135 µg/dL, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) was 323 µg/dL, and ferritin was 299.0 ng/mL. His HFE

A physical examination on presentation revealed erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral dorsal hands (Figure).

At the 4-month follow-up, the patient reported no new blister formations. A physical examination revealed well-healed scars and several clustered milia on bilateral dorsal hands with no active vesicles or bullae noted.

Patient 2

An African American male aged 63 years presented with a 1-month history of moderately painful blisters on his bilateral dorsal hands during treatment of chronic HCV (genotype 1a) with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. His medical history included gout, tobacco and alcohol addiction, osteoarthritis, and hepatic fibrosis (F3 by elastography). The patient’s medications included allopurinol, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide. He reported no history of dioxin exposure. On the day of presentation, he was on week 9 of the 12-week treatment ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimen. Laboratory results included an initial HCV viral load of 1,618,605 IU/mL. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen and HIV antibodies were negative. His iron was 191 µg/dL, TIBC 388 µg/dL, and ferritin 459.0 ng/mL. After 4 weeks of treatment, the patient’s hepatitis C viral load was undetectable.

A physical examination revealed several resolving erosions to his bilateral dorsal hands, some of which had overlying crusting along with one small hemorrhagic vesicle on the right dorsal hand. A punch biopsy of the hemorrhagic vesicle was performed and demonstrated a cell-poor subepidermal blister with festooning of the dermal papilla. A direct immunofluorescence study showed immunoglobulin (Ig) G fluorescence along the dermal-epidermal junction and within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. Weak IgM and C3 fluorescence also was noted within vessel walls in the superficial dermis. All of the patient findings and history were consistent with PCT, although pseudo-PCT also was a consideration. A 24-hour urine sample yielded negative results for porphobilinogen. Urine porphyrin test results were not available, leading to a presumptive histological diagnosis of PCT.

The patient completed 11 of the prescribed 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. The blisters resolved shortly thereafter.

Discussion

PCT has a well-established association with chronic HCV infection.4 We present 2 cases of a blistering disease clinically and histologically compatible with PCT that developed in patients only after initiation of treatment for chronic HCV with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. One case was confirmed as PCT on the basis of compatible histopathologic findings and a urine porphyrin assay that showed elevated levels of uroporphyrins and carboxylated metabolites. The second case was clinically and histologically suggestive of PCT but not confirmed by urine porphyrin testing. In both patients, after 8 to 9 weeks of a 12-week course of antiviral therapy, the blistering lesions were noted but appeared to be resolving, and no new lesions were noted after discontinuation of therapy. It appeared that the antiviral treatment temporally triggered the initiation of the blistering skin disease, and as the chronic HCV infection cleared after treatment, the blistering lesions also began to resolve.

Mechanistically, it is known that the virally-induced hepatic damage leads to inhibition of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, and the subsequent oxidation of porphyrinogens to porphyrins. Cofactors such as HIV infection also may contribute to development of PCT.5

De novo PCT has been documented during therapy using interferon and ribavirin.6 The hemolytic anemia and increased hepatic iron were implicated as potential etiologies.6 Patients with HCV and PCT treated with the newer direct-acting antiviral therapies have been described to have experienced improvement in PCT symptoms.3

Although there were rare reports of deterioration in renal and liver function,7 reactivation of HBV infection,8 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome9 with antiviral therapy, these complications were not observed in these patients. Both patients also had successful resolution of HCV infection, and by completion of the antiviral therapy, the blistering also resolved.

Conclusion

PCT is an extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection. Health care providers should be aware of the association of chronic HCV infection with PCT. The findings of PCT should not result in the delay or discontinuation of antiviral therapy.

1. Combalia A, To-Figueras J, Laguno M, Martinez-Rebollar M, Aguilera P. Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus induce a rapid clinical and biochemical remission of porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):e183-e184.

2. Younossi Z, Park H, Henry L, Adeyemi A, Stepanova M. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C: a meta-analysis of prevalence, quality of life, and economic burden. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1599-1608.

3. Tong Y, Song YK, Tyring S. Resolution of porphyria cutanea tarda in patients with hepatitis C following ledipasvir/sofosbuvir combination therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1393-1395.

4. Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky H. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int. 2012;32(6):880-893.

5. Quansah R, Cooper CJ, Said S, Bizet J, Paez D, Hernandez GT. Hepatitis C- and HIV-induced porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:35-40.

6. Azim J, McCurdy H, Moseley RH. Porphyria cutanea tarda as a complication of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(38):5913-5915.

7. Ahmed M. Harvoni-induced deterioration of renal and liver function. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2017;2(3):555588.

8. De Monte A, Courion J, Anty R, et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in adults infected with hepatitis C virus: reactivation of hepatitis B virus coinfection as a further challenge. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:27-30.

9. Verma N, Singh S, Sawatkar G, Singh V. Sofosbuvir induced Steven Johnson Syndrome in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2017;2(1):16-20.

1. Combalia A, To-Figueras J, Laguno M, Martinez-Rebollar M, Aguilera P. Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus induce a rapid clinical and biochemical remission of porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):e183-e184.

2. Younossi Z, Park H, Henry L, Adeyemi A, Stepanova M. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C: a meta-analysis of prevalence, quality of life, and economic burden. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1599-1608.

3. Tong Y, Song YK, Tyring S. Resolution of porphyria cutanea tarda in patients with hepatitis C following ledipasvir/sofosbuvir combination therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1393-1395.

4. Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky H. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int. 2012;32(6):880-893.

5. Quansah R, Cooper CJ, Said S, Bizet J, Paez D, Hernandez GT. Hepatitis C- and HIV-induced porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:35-40.

6. Azim J, McCurdy H, Moseley RH. Porphyria cutanea tarda as a complication of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(38):5913-5915.

7. Ahmed M. Harvoni-induced deterioration of renal and liver function. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2017;2(3):555588.

8. De Monte A, Courion J, Anty R, et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in adults infected with hepatitis C virus: reactivation of hepatitis B virus coinfection as a further challenge. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:27-30.

9. Verma N, Singh S, Sawatkar G, Singh V. Sofosbuvir induced Steven Johnson Syndrome in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2017;2(1):16-20.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Mycosis Fungoides

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

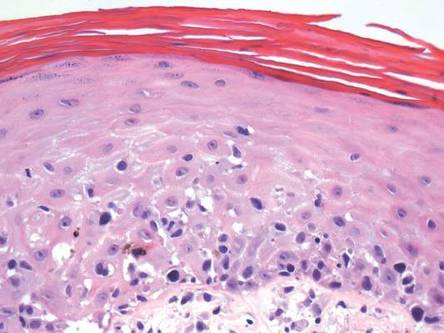

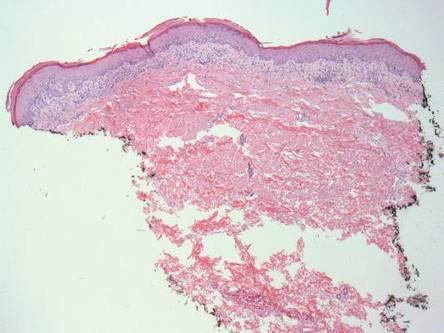

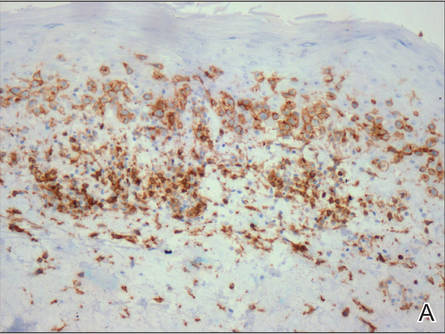

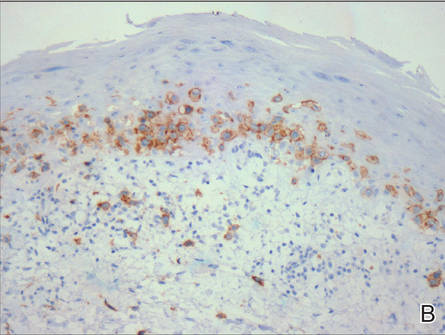

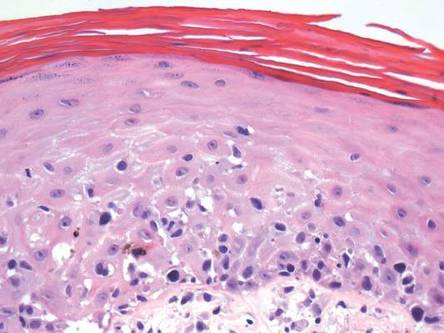

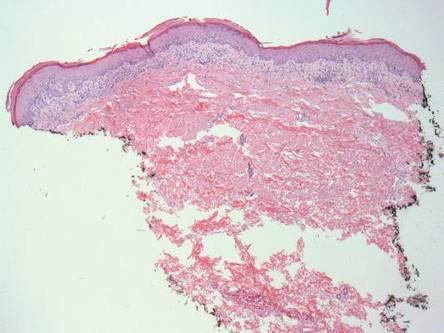

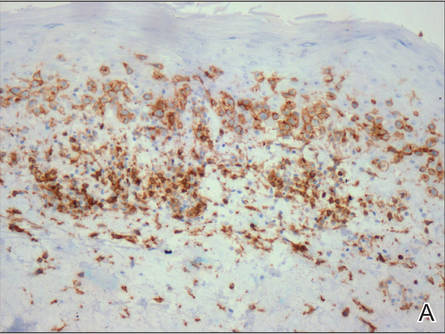

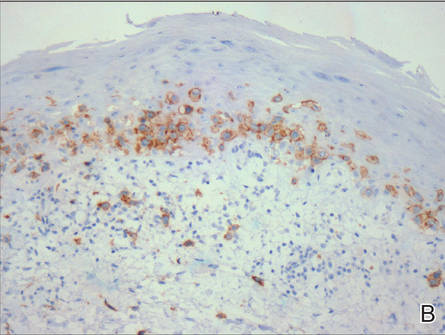

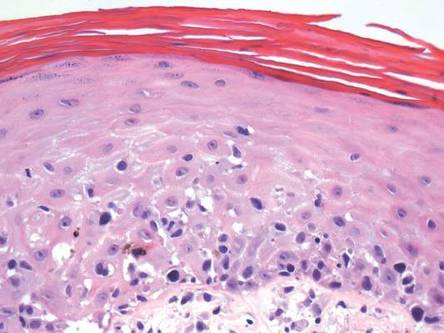

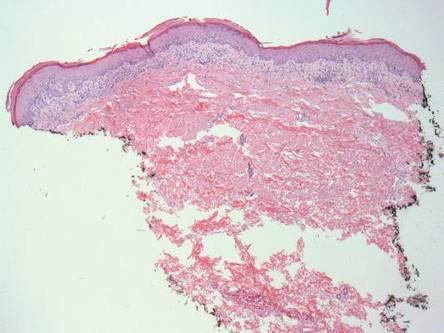

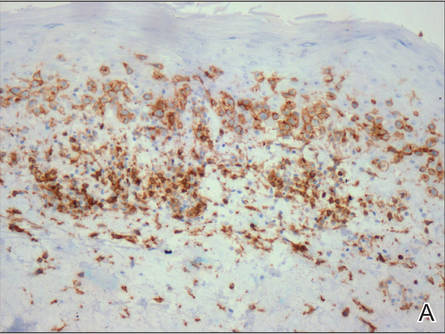

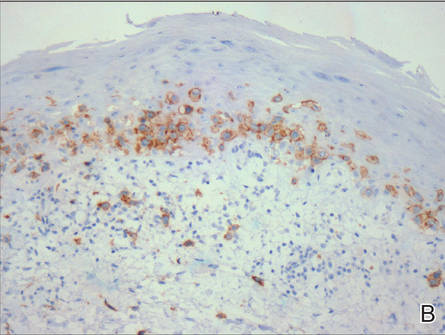

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

An otherwise healthy 62-year-old man presented for evaluation of multiple scaly erythematous plaques on the right upper arm and shoulder of 10 years’ duration. The patient reported a burning sensation but no exacerbation of the lesions upon sun exposure. He previously had been treated for a presumed clinical diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum but experienced only modest improvement with topical corticosteroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Previous trials of systemic antifungals also yielded minimal benefit.