User login

You can observe a lot by watching

"I have trained myself to see what others overlook."

—Sherlock Holmes1

The article by Grandjean and Huber in this issue2 is a timely reminder of the importance of skilled observation in medical care. Osler3 considered observation to represent “the whole art of medicine,” but warned that “for some men it is quite as difficult to record an observation in brief and plain language.” This insight captures not only the never-ending feud between written and visual communication, but also the higher efficiency of images. Leonardo da Vinci, a visual thinker with a touch of dyslexia,4 often boasted in colorful terms about the superiority of the visual. Next to his amazing rendition of a bovine heart he scribbled, “[Writer] how could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book? So, don’t bother with words unless you are speaking to the blind…you will always be overruled by the painter.”5

See related article and editorial

Ironically, physicians have often preferred the written over the visual. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., professor of anatomy at Harvard Medical School and renowned essayist, once wrote a scathing review of a new anatomy textbook that, according to him, had just too many pictures. “Let a student have illustrations,” he thundered “and just so surely will he use them at the expense of the text.”6 The book was Gray’s Anatomy, but Holmes’ tirade exemplifies the conundrum of our profession: to become physicians we must read (and memorize) lots of written text, with little emphasis on how much more efficiently information might be conveyed through a single picture.

This trend is probably worsening. When I first came to the United States 43 years ago, I was amazed at how many of my professors immediately grabbed a sheet of paper and started drawing their explanations to my questions. But I have not seen much of this lately, and that is a pity, since pictures are undoubtedly a better way of communicating.

OBSERVING A PATIENT WITH COPD

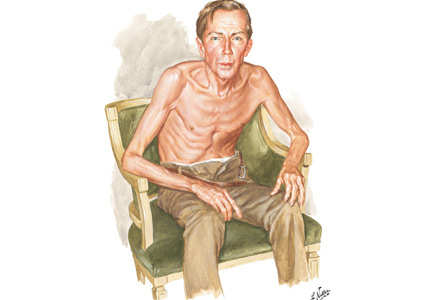

Netter’s patient is also exhaling through pursed lips. This reduces the respiratory rate and carbon dioxide level, while improving distribution of ventilation,9,10 oxygen saturation, tidal volume, inspiratory muscle strength, and diaphragmatic efficiency.11,12 Since less inspiratory force is required for each breath, dyspnea is also improved.13,14 Diagnostically, pursed‑lip breathing increases the probability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with a likelihood ratio of 5.05.15

The man in The Pink Puffer is using accessory respiratory muscles, which not only represents one of the earliest signs of airway obstruction, but also reflects severe disease. In fact, use of accessory respiratory muscles occurs in more than 90% of COPD patients admitted for acute exacerbations.7

Lastly, Netter’s patient exhibits inspiratory retraction of supraclavicular fossae and interspaces (tirage), which indicates increased airway resistance and reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).16,17 A clavicular “lift” of more than 5 mm correlates with an FEV1 of 0.6 L.18

But what is odd about this patient is what Netter did not portray: clubbing. This goes against the conventional wisdom of the time but is actually correct, since we now know that clubbing is more a feature of chronic bronchitis than emphysema.19 In fact, if present in a “pink puffer,” it should suggest an underlying malignancy. Hence, Netter reminds us that we should never convince ourselves that we see something simply because we know it should be there. Instead, we should always rely on what we see. This is, after all, how Vesalius debunked Galen’s anatomic errors: by seeing for himself. Tom McCrae, Osler’s right-hand man at Johns Hopkins, used to warn his students that one misses more by not seeing than by not knowing. Leonardo put it simply: “Wisdom is the daughter of [visual] experience.”20 In the end, Netter’s drawing reminds us that a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

TEACHING STUDENTS TO OBSERVE

Unfortunately, detecting detail is difficult. It is also very difficult to teach. For the past few months I’ve been asking astute clinicians how they observe, and most of them seem befuddled, as if I had asked which muscles they contract in order to walk. They just walk. And they just observe.

So, how can we rekindle this important but underappreciated component of the physician’s skill set? First of all, by becoming cognizant of its fundamental role in medicine. Second, by accepting that this is something that cannot be easily tested by single-best- answer, black-and-white, multiple-choice exams. Recognizing the complexity of clinical skills reminds us that not all that counts in medicine can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts. Yet it also provides a hurdle, since testing typically drives curriculum. If we cannot assess observation, how can we reincorporate it in the curriculum? Lastly, we need to regain ownership of the teaching of this skill. No art instructor can properly identify and interpret clinical findings. Hence, physicians ought to teach it. In the end, learning how to properly observe is a personal and lifelong effort. As Osler put it, “There is no more difficult art to acquire than the art of observation.”21

Leonardo used to quip that “There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, and those who do not see.”22 Yet this time Leonardo might have been wrong. There are really only two kinds of people: those who have been taught how to observe and those who have not. Leonardo was lucky enough to have been apprenticed to an artist whose nickname was Verrocchio, which resembles the Italian words vero occhio, a “fine eye.” Without Verrocchio, even Leonardo might not have become such a skilled observer. How many Verrocchios are around today?

- Doyle AC. A case of identity. In: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London, UK: George Newnes; 1892.

- Grandjean R, Huber LC. Thinker’s sign. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(7):439. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.19036

- Osler W. The natural method of teaching the subject of medicine. JAMA 1901; 36(24):1673–1679. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470240001001

- Mangione S, Del Maestro R. Was Leonardo da Vinci dyslexic? Am J Med 2019 Mar 7; pii:S0002-9343(19)30214-1. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.019

- Leonardo Da Vinci. Studies of the Heart of an Ox, Great Vessels and Bronchial Tree (c. 1513); pen and ink on blue paper, Windsor, London, UK Royal Library (19071r).

- Holmes OW Sr. Gray’s Anatomy. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1859; 60(25):489–496.

- O’Neill S, McCarthy DS. Postural relief of dyspnoea in severe chronic airflow limitation: relationship to respiratory muscle strength. Thorax 1983; 38(8):595–600. pmid:6612651

- Banzett RB, Topulos GP, Leith DE, Nations CS. Bracing arms increases the capacity for sustained hyperpnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138(1):106–109. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/138.1.106

- Mueller RE, Petty TL, Filley GF. Ventilation and arterial blood gas changes induced by pursed lips breathing. J Appl Physiol 1970; 28(6):784–789. doi:10.1152/jappl.1970.28.6.784

- Thoman RL, Stoker GL, Ross JC. The efficacy of pursed-lips breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1966; 93(1):100–106.

- Breslin EH. The pattern of respiratory muscle recruitment during pursed-lip breathing. Chest 1992; 101(1):75–78. pmid:1729114

- Jones AY, Dean E, Chow CC. Comparison of the oxygen cost of breathing exercises and spontaneous breathing in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther 2003; 83(5):424–431. pmid:12718708

- el-Manshawi A, Killian KJ, Summers E, Jones NL. Breathlessness during exercise with and without resistive loading. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986; 61(3):896–905. doi:10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.896

- Nield MA, Soo Hoo GW, Roper JM, Santiago S. Efficacy of pursed-lips breathing: a breathing pattern retraining strategy for dyspnea reduction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2007; 27(4):237–244. doi:10.1097/01.HCR.0000281770.82652.cb

- Mattos WL, Signori LG, Borges FK, Bergamin JA, Machado V. Accuracy of clinical examination findings in the diagnosis of COPD. J Bras Pneumol 2009; 35(5):404–408. pmid:19547847

- Stubbing DG. Physical signs in the evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pract Cardiol 1984;10:114–120.

- Godfrey S, Edwards RH, Campbell EJ, Newton-Howes J. Clinical and physiological associations of some physical signs observed in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1970; 25(3):285–287. pmid:5452279

- Anderson CL, Shankar PS, Scott JH. Physiological significance of sternomastoid muscle contraction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 1980; 25(9):937–939.

- Myers KA, Farquhar DR. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have clubbing? JAMA 2001; 286(3):341–347. pmid:11466101

- Richter JP. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. New York: Dover Books; 1970.

- Osler W. On the educational value of the medical society. Yale Medical Journal 1903; 9(10):325.

- Goodreads. Leonardo da Vinci Quotable Quote. http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/243423-there-are-three-classes-of-people-those-whosee-those. Accessed April 15, 2019.

"I have trained myself to see what others overlook."

—Sherlock Holmes1

The article by Grandjean and Huber in this issue2 is a timely reminder of the importance of skilled observation in medical care. Osler3 considered observation to represent “the whole art of medicine,” but warned that “for some men it is quite as difficult to record an observation in brief and plain language.” This insight captures not only the never-ending feud between written and visual communication, but also the higher efficiency of images. Leonardo da Vinci, a visual thinker with a touch of dyslexia,4 often boasted in colorful terms about the superiority of the visual. Next to his amazing rendition of a bovine heart he scribbled, “[Writer] how could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book? So, don’t bother with words unless you are speaking to the blind…you will always be overruled by the painter.”5

See related article and editorial

Ironically, physicians have often preferred the written over the visual. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., professor of anatomy at Harvard Medical School and renowned essayist, once wrote a scathing review of a new anatomy textbook that, according to him, had just too many pictures. “Let a student have illustrations,” he thundered “and just so surely will he use them at the expense of the text.”6 The book was Gray’s Anatomy, but Holmes’ tirade exemplifies the conundrum of our profession: to become physicians we must read (and memorize) lots of written text, with little emphasis on how much more efficiently information might be conveyed through a single picture.

This trend is probably worsening. When I first came to the United States 43 years ago, I was amazed at how many of my professors immediately grabbed a sheet of paper and started drawing their explanations to my questions. But I have not seen much of this lately, and that is a pity, since pictures are undoubtedly a better way of communicating.

OBSERVING A PATIENT WITH COPD

Netter’s patient is also exhaling through pursed lips. This reduces the respiratory rate and carbon dioxide level, while improving distribution of ventilation,9,10 oxygen saturation, tidal volume, inspiratory muscle strength, and diaphragmatic efficiency.11,12 Since less inspiratory force is required for each breath, dyspnea is also improved.13,14 Diagnostically, pursed‑lip breathing increases the probability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with a likelihood ratio of 5.05.15

The man in The Pink Puffer is using accessory respiratory muscles, which not only represents one of the earliest signs of airway obstruction, but also reflects severe disease. In fact, use of accessory respiratory muscles occurs in more than 90% of COPD patients admitted for acute exacerbations.7

Lastly, Netter’s patient exhibits inspiratory retraction of supraclavicular fossae and interspaces (tirage), which indicates increased airway resistance and reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).16,17 A clavicular “lift” of more than 5 mm correlates with an FEV1 of 0.6 L.18

But what is odd about this patient is what Netter did not portray: clubbing. This goes against the conventional wisdom of the time but is actually correct, since we now know that clubbing is more a feature of chronic bronchitis than emphysema.19 In fact, if present in a “pink puffer,” it should suggest an underlying malignancy. Hence, Netter reminds us that we should never convince ourselves that we see something simply because we know it should be there. Instead, we should always rely on what we see. This is, after all, how Vesalius debunked Galen’s anatomic errors: by seeing for himself. Tom McCrae, Osler’s right-hand man at Johns Hopkins, used to warn his students that one misses more by not seeing than by not knowing. Leonardo put it simply: “Wisdom is the daughter of [visual] experience.”20 In the end, Netter’s drawing reminds us that a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

TEACHING STUDENTS TO OBSERVE

Unfortunately, detecting detail is difficult. It is also very difficult to teach. For the past few months I’ve been asking astute clinicians how they observe, and most of them seem befuddled, as if I had asked which muscles they contract in order to walk. They just walk. And they just observe.

So, how can we rekindle this important but underappreciated component of the physician’s skill set? First of all, by becoming cognizant of its fundamental role in medicine. Second, by accepting that this is something that cannot be easily tested by single-best- answer, black-and-white, multiple-choice exams. Recognizing the complexity of clinical skills reminds us that not all that counts in medicine can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts. Yet it also provides a hurdle, since testing typically drives curriculum. If we cannot assess observation, how can we reincorporate it in the curriculum? Lastly, we need to regain ownership of the teaching of this skill. No art instructor can properly identify and interpret clinical findings. Hence, physicians ought to teach it. In the end, learning how to properly observe is a personal and lifelong effort. As Osler put it, “There is no more difficult art to acquire than the art of observation.”21

Leonardo used to quip that “There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, and those who do not see.”22 Yet this time Leonardo might have been wrong. There are really only two kinds of people: those who have been taught how to observe and those who have not. Leonardo was lucky enough to have been apprenticed to an artist whose nickname was Verrocchio, which resembles the Italian words vero occhio, a “fine eye.” Without Verrocchio, even Leonardo might not have become such a skilled observer. How many Verrocchios are around today?

"I have trained myself to see what others overlook."

—Sherlock Holmes1

The article by Grandjean and Huber in this issue2 is a timely reminder of the importance of skilled observation in medical care. Osler3 considered observation to represent “the whole art of medicine,” but warned that “for some men it is quite as difficult to record an observation in brief and plain language.” This insight captures not only the never-ending feud between written and visual communication, but also the higher efficiency of images. Leonardo da Vinci, a visual thinker with a touch of dyslexia,4 often boasted in colorful terms about the superiority of the visual. Next to his amazing rendition of a bovine heart he scribbled, “[Writer] how could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book? So, don’t bother with words unless you are speaking to the blind…you will always be overruled by the painter.”5

See related article and editorial

Ironically, physicians have often preferred the written over the visual. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., professor of anatomy at Harvard Medical School and renowned essayist, once wrote a scathing review of a new anatomy textbook that, according to him, had just too many pictures. “Let a student have illustrations,” he thundered “and just so surely will he use them at the expense of the text.”6 The book was Gray’s Anatomy, but Holmes’ tirade exemplifies the conundrum of our profession: to become physicians we must read (and memorize) lots of written text, with little emphasis on how much more efficiently information might be conveyed through a single picture.

This trend is probably worsening. When I first came to the United States 43 years ago, I was amazed at how many of my professors immediately grabbed a sheet of paper and started drawing their explanations to my questions. But I have not seen much of this lately, and that is a pity, since pictures are undoubtedly a better way of communicating.

OBSERVING A PATIENT WITH COPD

Netter’s patient is also exhaling through pursed lips. This reduces the respiratory rate and carbon dioxide level, while improving distribution of ventilation,9,10 oxygen saturation, tidal volume, inspiratory muscle strength, and diaphragmatic efficiency.11,12 Since less inspiratory force is required for each breath, dyspnea is also improved.13,14 Diagnostically, pursed‑lip breathing increases the probability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with a likelihood ratio of 5.05.15

The man in The Pink Puffer is using accessory respiratory muscles, which not only represents one of the earliest signs of airway obstruction, but also reflects severe disease. In fact, use of accessory respiratory muscles occurs in more than 90% of COPD patients admitted for acute exacerbations.7

Lastly, Netter’s patient exhibits inspiratory retraction of supraclavicular fossae and interspaces (tirage), which indicates increased airway resistance and reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).16,17 A clavicular “lift” of more than 5 mm correlates with an FEV1 of 0.6 L.18

But what is odd about this patient is what Netter did not portray: clubbing. This goes against the conventional wisdom of the time but is actually correct, since we now know that clubbing is more a feature of chronic bronchitis than emphysema.19 In fact, if present in a “pink puffer,” it should suggest an underlying malignancy. Hence, Netter reminds us that we should never convince ourselves that we see something simply because we know it should be there. Instead, we should always rely on what we see. This is, after all, how Vesalius debunked Galen’s anatomic errors: by seeing for himself. Tom McCrae, Osler’s right-hand man at Johns Hopkins, used to warn his students that one misses more by not seeing than by not knowing. Leonardo put it simply: “Wisdom is the daughter of [visual] experience.”20 In the end, Netter’s drawing reminds us that a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

TEACHING STUDENTS TO OBSERVE

Unfortunately, detecting detail is difficult. It is also very difficult to teach. For the past few months I’ve been asking astute clinicians how they observe, and most of them seem befuddled, as if I had asked which muscles they contract in order to walk. They just walk. And they just observe.

So, how can we rekindle this important but underappreciated component of the physician’s skill set? First of all, by becoming cognizant of its fundamental role in medicine. Second, by accepting that this is something that cannot be easily tested by single-best- answer, black-and-white, multiple-choice exams. Recognizing the complexity of clinical skills reminds us that not all that counts in medicine can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts. Yet it also provides a hurdle, since testing typically drives curriculum. If we cannot assess observation, how can we reincorporate it in the curriculum? Lastly, we need to regain ownership of the teaching of this skill. No art instructor can properly identify and interpret clinical findings. Hence, physicians ought to teach it. In the end, learning how to properly observe is a personal and lifelong effort. As Osler put it, “There is no more difficult art to acquire than the art of observation.”21

Leonardo used to quip that “There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, and those who do not see.”22 Yet this time Leonardo might have been wrong. There are really only two kinds of people: those who have been taught how to observe and those who have not. Leonardo was lucky enough to have been apprenticed to an artist whose nickname was Verrocchio, which resembles the Italian words vero occhio, a “fine eye.” Without Verrocchio, even Leonardo might not have become such a skilled observer. How many Verrocchios are around today?

- Doyle AC. A case of identity. In: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London, UK: George Newnes; 1892.

- Grandjean R, Huber LC. Thinker’s sign. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(7):439. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.19036

- Osler W. The natural method of teaching the subject of medicine. JAMA 1901; 36(24):1673–1679. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470240001001

- Mangione S, Del Maestro R. Was Leonardo da Vinci dyslexic? Am J Med 2019 Mar 7; pii:S0002-9343(19)30214-1. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.019

- Leonardo Da Vinci. Studies of the Heart of an Ox, Great Vessels and Bronchial Tree (c. 1513); pen and ink on blue paper, Windsor, London, UK Royal Library (19071r).

- Holmes OW Sr. Gray’s Anatomy. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1859; 60(25):489–496.

- O’Neill S, McCarthy DS. Postural relief of dyspnoea in severe chronic airflow limitation: relationship to respiratory muscle strength. Thorax 1983; 38(8):595–600. pmid:6612651

- Banzett RB, Topulos GP, Leith DE, Nations CS. Bracing arms increases the capacity for sustained hyperpnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138(1):106–109. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/138.1.106

- Mueller RE, Petty TL, Filley GF. Ventilation and arterial blood gas changes induced by pursed lips breathing. J Appl Physiol 1970; 28(6):784–789. doi:10.1152/jappl.1970.28.6.784

- Thoman RL, Stoker GL, Ross JC. The efficacy of pursed-lips breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1966; 93(1):100–106.

- Breslin EH. The pattern of respiratory muscle recruitment during pursed-lip breathing. Chest 1992; 101(1):75–78. pmid:1729114

- Jones AY, Dean E, Chow CC. Comparison of the oxygen cost of breathing exercises and spontaneous breathing in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther 2003; 83(5):424–431. pmid:12718708

- el-Manshawi A, Killian KJ, Summers E, Jones NL. Breathlessness during exercise with and without resistive loading. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986; 61(3):896–905. doi:10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.896

- Nield MA, Soo Hoo GW, Roper JM, Santiago S. Efficacy of pursed-lips breathing: a breathing pattern retraining strategy for dyspnea reduction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2007; 27(4):237–244. doi:10.1097/01.HCR.0000281770.82652.cb

- Mattos WL, Signori LG, Borges FK, Bergamin JA, Machado V. Accuracy of clinical examination findings in the diagnosis of COPD. J Bras Pneumol 2009; 35(5):404–408. pmid:19547847

- Stubbing DG. Physical signs in the evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pract Cardiol 1984;10:114–120.

- Godfrey S, Edwards RH, Campbell EJ, Newton-Howes J. Clinical and physiological associations of some physical signs observed in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1970; 25(3):285–287. pmid:5452279

- Anderson CL, Shankar PS, Scott JH. Physiological significance of sternomastoid muscle contraction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 1980; 25(9):937–939.

- Myers KA, Farquhar DR. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have clubbing? JAMA 2001; 286(3):341–347. pmid:11466101

- Richter JP. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. New York: Dover Books; 1970.

- Osler W. On the educational value of the medical society. Yale Medical Journal 1903; 9(10):325.

- Goodreads. Leonardo da Vinci Quotable Quote. http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/243423-there-are-three-classes-of-people-those-whosee-those. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Doyle AC. A case of identity. In: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London, UK: George Newnes; 1892.

- Grandjean R, Huber LC. Thinker’s sign. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(7):439. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.19036

- Osler W. The natural method of teaching the subject of medicine. JAMA 1901; 36(24):1673–1679. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470240001001

- Mangione S, Del Maestro R. Was Leonardo da Vinci dyslexic? Am J Med 2019 Mar 7; pii:S0002-9343(19)30214-1. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.019

- Leonardo Da Vinci. Studies of the Heart of an Ox, Great Vessels and Bronchial Tree (c. 1513); pen and ink on blue paper, Windsor, London, UK Royal Library (19071r).

- Holmes OW Sr. Gray’s Anatomy. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1859; 60(25):489–496.

- O’Neill S, McCarthy DS. Postural relief of dyspnoea in severe chronic airflow limitation: relationship to respiratory muscle strength. Thorax 1983; 38(8):595–600. pmid:6612651

- Banzett RB, Topulos GP, Leith DE, Nations CS. Bracing arms increases the capacity for sustained hyperpnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138(1):106–109. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/138.1.106

- Mueller RE, Petty TL, Filley GF. Ventilation and arterial blood gas changes induced by pursed lips breathing. J Appl Physiol 1970; 28(6):784–789. doi:10.1152/jappl.1970.28.6.784

- Thoman RL, Stoker GL, Ross JC. The efficacy of pursed-lips breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1966; 93(1):100–106.

- Breslin EH. The pattern of respiratory muscle recruitment during pursed-lip breathing. Chest 1992; 101(1):75–78. pmid:1729114

- Jones AY, Dean E, Chow CC. Comparison of the oxygen cost of breathing exercises and spontaneous breathing in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther 2003; 83(5):424–431. pmid:12718708

- el-Manshawi A, Killian KJ, Summers E, Jones NL. Breathlessness during exercise with and without resistive loading. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986; 61(3):896–905. doi:10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.896

- Nield MA, Soo Hoo GW, Roper JM, Santiago S. Efficacy of pursed-lips breathing: a breathing pattern retraining strategy for dyspnea reduction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2007; 27(4):237–244. doi:10.1097/01.HCR.0000281770.82652.cb

- Mattos WL, Signori LG, Borges FK, Bergamin JA, Machado V. Accuracy of clinical examination findings in the diagnosis of COPD. J Bras Pneumol 2009; 35(5):404–408. pmid:19547847

- Stubbing DG. Physical signs in the evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pract Cardiol 1984;10:114–120.

- Godfrey S, Edwards RH, Campbell EJ, Newton-Howes J. Clinical and physiological associations of some physical signs observed in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1970; 25(3):285–287. pmid:5452279

- Anderson CL, Shankar PS, Scott JH. Physiological significance of sternomastoid muscle contraction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 1980; 25(9):937–939.

- Myers KA, Farquhar DR. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have clubbing? JAMA 2001; 286(3):341–347. pmid:11466101

- Richter JP. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. New York: Dover Books; 1970.

- Osler W. On the educational value of the medical society. Yale Medical Journal 1903; 9(10):325.

- Goodreads. Leonardo da Vinci Quotable Quote. http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/243423-there-are-three-classes-of-people-those-whosee-those. Accessed April 15, 2019.

The old humanities and the new science at 100: Osler’s enduring message

“Twin berries on one stem, grievous damage has been done to both in regarding the Humanities and Science in any other light than complemental.”

—Sir William Osler1

The year 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of Sir William Osler’s last public speech. Still reeling from the death of his only son in World War I, he had been asked to give the presidential inaugural address of the Classical Association at Oxford. It was the first time a physician had received the honor, and Osler took the assignment very seriously. He chose to speak about “The old humanities and the new science,” and to call for a reunification of the two fields. “Humanists have not enough Science” he warned, “and Science sadly lacks the Humanities…this unhappy divorce…should never have taken place.”1 Later, he said that it was the speech to which he had given the greatest thought and preparation. It was in fact Osler’s personal legacy: 2 months later he turned 70, and 7 months later he was dead.

Revisiting the address today, what can Osler teach the high-tech physician of today, when doctors have become “providers” and patients “consumers”? Is Osler’s message still relevant to our craft, or has he simply become an icon of professional nostalgia with little value for our times?

THE NEED FOR THE HUMANITIES IN MEDICINE

Medicine has certainly grown both powerful and successful. Yet it is also confronting hurdles that would have been unimaginable in Osler’s time. Physicians are now the professionals with the highest suicide rate,2 a burnout rate as high as 70%,3,4 rampant depression,5 dwindling empathy,6 a predominantly negative perception by the public,7,8 and a disturbing propensity to quit.9 These, of course, may just be symptoms of an increasingly meaningless environment wherein doctors have become small cogs in a medical-industrial complex they can’t control or even understand. Still, is it possible that something more personal may have been lost in the way we now select and educate physicians? Could this, in turn, make us less resilient?

In this regard, Osler’s last public speech serves as an enduring reminder of the need for the humanities in medicine. Osler not only believed it, but throughout his life never missed a chance to express in words, writings, and deeds that the humanities are indeed “the hormones” of the profession. In 1919 he warned against the risk of separating our humanistic tradition from the sciences, and urged us “to infect [anyone] with the spirit of the Humanities,” since to him that was “the greatest single gift in education.”1

Unfortunately, the humanities are slippery, not easily quantifiable, hard to define, and seemingly incompatible with an evidence-based approach. Quite understandably, today’s data-obsessed medicine views them with suspicion. But besides reminding us that in medicine not all that counts can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts, the humanities are in fact a fundamental component of the physician’s skill set.

In a multicenter survey of 5 medical schools,10 there was indeed a correlation between students’ exposure to the humanities and many of the personal qualities whose absence we lament in today’s medicine: empathy, tolerance for ambiguity, emotional intelligence, and prevention of burnout. Most significant was a strong correlation with wisdom, as measured by the 21-item Brief Wisdom Screening Scale.11 That all these traits may correlate with humanities exposure is intuitive, since the humanities not only teach tolerance and compassion, but also capture the collective experience of those who came before us. Hence, they teach us wisdom. Wisdom is not an ACGME competency, but it’s undoubtedly a prerequisite for the art of healing.12 In fact, wisdom may very well be the fundamental trait that characterizes a well-rounded physician, since it encompasses empathy, resilience, comfort with ambiguity, and the capacity to learn from the past. Not surprisingly, wisdom in the world was Osler’s closing wish in 1919.

The humanities can also nurture the very personal qualities we desire in physicians. For example, observing drama fosters empathy,13 as does taking an elective in medical humanities.14 Drawing enhances the reading of faces,15 and observing art improves the art of clinical observation.16 Reading good literature prompts better detection of emotions,17 and reflective writing improves students’ well-being.18 Playing a musical instrument reduces burnout.19 And an undergraduate major in the humanities correlates with greater tolerance for ambiguity,20 a highly desirable trait in physicians, since it means openness to new ideas and the capacity to better cope with difficult situations.21

In fact, some of the qualities fostered by the humanities even translate into better patient care. For instance, tolerance for ambiguity correlates with more positive attitudes towards patients who have frustrating complaints,22 with lower use of resources,23 and with a career choice in direct patient care.24 Hence, it has been suggested that it should be a prerequisite for medical school admission.25 Physicians’ empathy is also beneficial, since it correlates with a lower rate of complications and better outcomes in the care of diabetic patients.26 This should not come as a surprise. As Hippocrates put it 2,500 years ago, “some patients, though conscious that their condition is perilous, recover their health simply through their contentment with the goodness of the physician.”27

Lastly, studying the humanities may provide crucial antibodies against the pain and suffering that are unavoidable staples of the human condition. To paraphrase Osler, the humanities might vaccinate us against the difficulties of our profession. Hippocrates himself had suggested that “it is well to superintend the sick to make them well, to care for the healthy to keep them well, but also to care for one’s self…”27 That is why many institutions now require medical students to take humanities courses.28

MEDICINE: AN ART BASED ON SCIENCE

Yet this effort may amount to a rearguard action that arrives too late and provides too little. The humanities should probably be taught before medical school.29 After all, if it’s possible to make a scientist out of a humanist (Osler was living proof), the experience of the past decades seems to suggest that it’s considerably harder to make a humanist out of a scientist—hence the need to revisit undergraduate curricula and admission criteria to medical school, so that students can receive an adequate foundation in both arenas. Ironically, students express positive attitudes toward a liberal education and think it would actually help them as physicians.30 Yet they also understand that the selection process remains tilted towards the sciences.30–32

For Osler, scientific evidence was important but not a substitute for a humanistic approach. As he reminded students, “The practice of medicine is an art based on science,”33 whose main goals are to prevent disease, relieve suffering, and heal the sick. To do so, one ought to care more “for the individual patient than for the special features of the disease.”34 But he warned them, “It is much harder to acquire the art than the science.”35 In fact, “The practice of medicine is a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.”33 Hence the need to “cultivate equally well hearts and heads.”34 Almost foreseeing our infatuation with guidelines, he also warned against turning medicine into assembly-line work. There are “two great types of practitioners—the routinist and the rationalist,” he said in 1900, and “into the clutches of the demon routine the majority of us ultimately come.”36

Like most great people, Osler was a man of lights, shadows, and contradictions, probably not quite the saint we wish to believe. Yet he provides insights that are as valid today as they were for his own times, and possibly even more so. His 1919 speech is a paean to the humanities, but also a potential eulogy. As a Victorian physician, Osler was a blend of the new science and the old humanities. He knew that “the old art cannot possibly be replaced by, but must be absorbed in, the new science.”35 Yet he could also see the upcoming split between the two cultures, and he tried to warn us. He could in fact foresee the end of an entire way of life. As he said in his address, “there must be a very different civilization or there will be no civilization at all.”1

The crisis we face in medicine today may indeed be a symptom of a much larger cultural shift. As Osler himself put it, “The philosophies of one age have become the absurdities of the next, and the foolishness of yesterday has become the wisdom of tomorrow.”33 Like Osler, we live in times of transition that require us to act. If in 1910 Flexner gave us science,37 Osler in 1919 reminded us that medicine also needs the humanities. We ought to heed his message and reconcile the two fields. The alternative is a future full of tricorders and burned-out technicians, but sorely lacking in healers.

- Osler W. The old humanities and the new science: the presidential address delivered before the Classical Association at Oxford, May, 1919. Br Med J 1919; 2(3053):1–7. pmid:20769536

- Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med 2007; 37(8):1131–1140. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000487

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(12):1600–1613. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(5):334–341. pmid:18765703

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015; 314(22):2373–2383. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ 2004; 38(9):934–941. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x

- Flores G. Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: the portrayal of physicians in the movies. J Natl Med Assoc 2002; 94(7):635–658. pmid:12126293

- Imber JB. Trusting Doctors: The Decline of Moral Authority in American Medicine. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2008.

- Krauthammer, C. Why doctors quit. The Washington Post. May 28, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-doctors-quit/2015/05/28/1e9d8e6e-056f-11e5-a428-c984eb077d4e_story.html?utm_term=.aa8804a518db. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Mangione S, Chakraborti C, Staltari G, et al. Medical students' exposure to the humanities correlates with positive personal qualities and reduced burnout: a multi-institutional US survey. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33(5):628–634. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4275-8

- Glück J, König S, Naschenweng K, et al. How to measure wisdom: content, reliability, and validity of five measures. Front Psychol 2013; 4:405. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00405

- Papagiannis A. Eliot’s triad: information, knowledge and wisdom in medicine. Hektoen International. Spring 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/01/29/eliots-triad-information-knowledge-and-wisdom-in-medicine. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach 2013; 35(12):996–1001. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.802300

- Graham J, Benson LM, Swanson J, Potyk D, Daratha K, Roberts K. Medical humanities coursework is associated with greater measured empathy in medical students. Am J Med 2016; 129(12):1334–1337. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.005

- Brechet C, Baldy R, Picard D. How does Sam feel? Children's labelling and drawing of basic emotions. Br J Dev Psychol 2009; 27(Pt 3):587–606. pmid:19994570

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23(7):991–997. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0

- Kidd DC, Castano E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 2013; 342(6156):377–380. doi:10.1126/science.1239918

- Shapiro J, Kasman D, Shafer A. Words and wards: a model of reflective writing and its uses in medical education. J Med Humanit 2006; 27(4):231–244. doi:10.1007/s10912-006-9020-y

- Bittman BB, Snyder C, Bruhn KT, et al. Recreational music-making: an integrative group intervention for reducing burnout and improving mood states in first year associate degree nursing students: insights and economic impact. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2004;1:Article12. doi:10.2202/1548-923x.1044

- DeForge BR, Sobal J. Intolerance of ambiguity in students entering medical school. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28(8):869–874. pmid:2705020

- Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India 2004; 52:739–742. pmid:15839454

- Merrill JM, Camacho Z, Laux LF, Thornby JI, Vallbona C. How medical school shapes students’ orientation to patients’ psychological problems. Acad Med 1991; 66(9 suppl):S4–S6. pmid:1930523

- Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, Gerrity MS, Orav EJ, Centor R. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Making 1998; 18(3):320–329. doi:10.1177/0272989X9801800310

- Gerrity MS, Earp JAL, DeVilles RF, DW Light. Uncertainty and professional work: perceptions of physicians in clinical practice. Am J Sociol 1992; 97(4):1022–1051. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2781505. Accessed March 6, 2019.

- Geller G. Tolerance for ambiguity: an ethics-based criterion for medical student selection. Acad Med 2013; 88(5):581–584. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828a4b8e

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med 2011; 86(3):359–364. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1

- Hippocrates. Precepts. Section 8, Part VI. Perseus Digital Library. http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekFeb2011&getid=1&query=Hipp.%20Praec.%208. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Kidd MG, Connor JT. Striving to do good things: teaching humanities in Canadian medical schools. J Med Humanit 2008; 29(1):45–54. doi:10.1007/s10912-007-9049-6

- Thomas L. Notes of a biology-watcher. How to fix the premedical curriculum. N Engl J Med 1978; 298(21):1180–1181. doi:10.1056/NEJM197805252982106

- Simmons A. Beyond the premedical syndrome: premedical student attitudes toward liberal education and implications for advising. NACADA Journal 2005; 25(1):64–73.

- Kumar B, Swee ML and Suneja M. The premedical curriculum: we can do better for future physicians. South Med J 2017; 110(8):538–539. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000683

- Gunderman RB, Kanter SL. Perspective: “how to fix the premedical curriculum” revisited. Acad Med 2008; 83(12):1158–1161. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c6515

- Osler W. Aequanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Blakiston; 1904.

- Osler W. Address to the students of the Albany Medical College. Albany Med Ann 1899; 20:307–309.

- Osler W. The reserves of life. St Mary’s Hosp Gaz 1907; 13:95–98.

- Osler W. An address on the importance of post-graduate study. Delivered at the opening of the Museums of the Medical Graduates College and Polyclinic, July 4th, 1900. Br Med J 1900; 2(2063):73–75. pmid:20759107

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York, The Carnegie Foundation 1910.

“Twin berries on one stem, grievous damage has been done to both in regarding the Humanities and Science in any other light than complemental.”

—Sir William Osler1

The year 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of Sir William Osler’s last public speech. Still reeling from the death of his only son in World War I, he had been asked to give the presidential inaugural address of the Classical Association at Oxford. It was the first time a physician had received the honor, and Osler took the assignment very seriously. He chose to speak about “The old humanities and the new science,” and to call for a reunification of the two fields. “Humanists have not enough Science” he warned, “and Science sadly lacks the Humanities…this unhappy divorce…should never have taken place.”1 Later, he said that it was the speech to which he had given the greatest thought and preparation. It was in fact Osler’s personal legacy: 2 months later he turned 70, and 7 months later he was dead.

Revisiting the address today, what can Osler teach the high-tech physician of today, when doctors have become “providers” and patients “consumers”? Is Osler’s message still relevant to our craft, or has he simply become an icon of professional nostalgia with little value for our times?

THE NEED FOR THE HUMANITIES IN MEDICINE

Medicine has certainly grown both powerful and successful. Yet it is also confronting hurdles that would have been unimaginable in Osler’s time. Physicians are now the professionals with the highest suicide rate,2 a burnout rate as high as 70%,3,4 rampant depression,5 dwindling empathy,6 a predominantly negative perception by the public,7,8 and a disturbing propensity to quit.9 These, of course, may just be symptoms of an increasingly meaningless environment wherein doctors have become small cogs in a medical-industrial complex they can’t control or even understand. Still, is it possible that something more personal may have been lost in the way we now select and educate physicians? Could this, in turn, make us less resilient?

In this regard, Osler’s last public speech serves as an enduring reminder of the need for the humanities in medicine. Osler not only believed it, but throughout his life never missed a chance to express in words, writings, and deeds that the humanities are indeed “the hormones” of the profession. In 1919 he warned against the risk of separating our humanistic tradition from the sciences, and urged us “to infect [anyone] with the spirit of the Humanities,” since to him that was “the greatest single gift in education.”1

Unfortunately, the humanities are slippery, not easily quantifiable, hard to define, and seemingly incompatible with an evidence-based approach. Quite understandably, today’s data-obsessed medicine views them with suspicion. But besides reminding us that in medicine not all that counts can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts, the humanities are in fact a fundamental component of the physician’s skill set.

In a multicenter survey of 5 medical schools,10 there was indeed a correlation between students’ exposure to the humanities and many of the personal qualities whose absence we lament in today’s medicine: empathy, tolerance for ambiguity, emotional intelligence, and prevention of burnout. Most significant was a strong correlation with wisdom, as measured by the 21-item Brief Wisdom Screening Scale.11 That all these traits may correlate with humanities exposure is intuitive, since the humanities not only teach tolerance and compassion, but also capture the collective experience of those who came before us. Hence, they teach us wisdom. Wisdom is not an ACGME competency, but it’s undoubtedly a prerequisite for the art of healing.12 In fact, wisdom may very well be the fundamental trait that characterizes a well-rounded physician, since it encompasses empathy, resilience, comfort with ambiguity, and the capacity to learn from the past. Not surprisingly, wisdom in the world was Osler’s closing wish in 1919.

The humanities can also nurture the very personal qualities we desire in physicians. For example, observing drama fosters empathy,13 as does taking an elective in medical humanities.14 Drawing enhances the reading of faces,15 and observing art improves the art of clinical observation.16 Reading good literature prompts better detection of emotions,17 and reflective writing improves students’ well-being.18 Playing a musical instrument reduces burnout.19 And an undergraduate major in the humanities correlates with greater tolerance for ambiguity,20 a highly desirable trait in physicians, since it means openness to new ideas and the capacity to better cope with difficult situations.21

In fact, some of the qualities fostered by the humanities even translate into better patient care. For instance, tolerance for ambiguity correlates with more positive attitudes towards patients who have frustrating complaints,22 with lower use of resources,23 and with a career choice in direct patient care.24 Hence, it has been suggested that it should be a prerequisite for medical school admission.25 Physicians’ empathy is also beneficial, since it correlates with a lower rate of complications and better outcomes in the care of diabetic patients.26 This should not come as a surprise. As Hippocrates put it 2,500 years ago, “some patients, though conscious that their condition is perilous, recover their health simply through their contentment with the goodness of the physician.”27

Lastly, studying the humanities may provide crucial antibodies against the pain and suffering that are unavoidable staples of the human condition. To paraphrase Osler, the humanities might vaccinate us against the difficulties of our profession. Hippocrates himself had suggested that “it is well to superintend the sick to make them well, to care for the healthy to keep them well, but also to care for one’s self…”27 That is why many institutions now require medical students to take humanities courses.28

MEDICINE: AN ART BASED ON SCIENCE

Yet this effort may amount to a rearguard action that arrives too late and provides too little. The humanities should probably be taught before medical school.29 After all, if it’s possible to make a scientist out of a humanist (Osler was living proof), the experience of the past decades seems to suggest that it’s considerably harder to make a humanist out of a scientist—hence the need to revisit undergraduate curricula and admission criteria to medical school, so that students can receive an adequate foundation in both arenas. Ironically, students express positive attitudes toward a liberal education and think it would actually help them as physicians.30 Yet they also understand that the selection process remains tilted towards the sciences.30–32

For Osler, scientific evidence was important but not a substitute for a humanistic approach. As he reminded students, “The practice of medicine is an art based on science,”33 whose main goals are to prevent disease, relieve suffering, and heal the sick. To do so, one ought to care more “for the individual patient than for the special features of the disease.”34 But he warned them, “It is much harder to acquire the art than the science.”35 In fact, “The practice of medicine is a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.”33 Hence the need to “cultivate equally well hearts and heads.”34 Almost foreseeing our infatuation with guidelines, he also warned against turning medicine into assembly-line work. There are “two great types of practitioners—the routinist and the rationalist,” he said in 1900, and “into the clutches of the demon routine the majority of us ultimately come.”36

Like most great people, Osler was a man of lights, shadows, and contradictions, probably not quite the saint we wish to believe. Yet he provides insights that are as valid today as they were for his own times, and possibly even more so. His 1919 speech is a paean to the humanities, but also a potential eulogy. As a Victorian physician, Osler was a blend of the new science and the old humanities. He knew that “the old art cannot possibly be replaced by, but must be absorbed in, the new science.”35 Yet he could also see the upcoming split between the two cultures, and he tried to warn us. He could in fact foresee the end of an entire way of life. As he said in his address, “there must be a very different civilization or there will be no civilization at all.”1

The crisis we face in medicine today may indeed be a symptom of a much larger cultural shift. As Osler himself put it, “The philosophies of one age have become the absurdities of the next, and the foolishness of yesterday has become the wisdom of tomorrow.”33 Like Osler, we live in times of transition that require us to act. If in 1910 Flexner gave us science,37 Osler in 1919 reminded us that medicine also needs the humanities. We ought to heed his message and reconcile the two fields. The alternative is a future full of tricorders and burned-out technicians, but sorely lacking in healers.

“Twin berries on one stem, grievous damage has been done to both in regarding the Humanities and Science in any other light than complemental.”

—Sir William Osler1

The year 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of Sir William Osler’s last public speech. Still reeling from the death of his only son in World War I, he had been asked to give the presidential inaugural address of the Classical Association at Oxford. It was the first time a physician had received the honor, and Osler took the assignment very seriously. He chose to speak about “The old humanities and the new science,” and to call for a reunification of the two fields. “Humanists have not enough Science” he warned, “and Science sadly lacks the Humanities…this unhappy divorce…should never have taken place.”1 Later, he said that it was the speech to which he had given the greatest thought and preparation. It was in fact Osler’s personal legacy: 2 months later he turned 70, and 7 months later he was dead.

Revisiting the address today, what can Osler teach the high-tech physician of today, when doctors have become “providers” and patients “consumers”? Is Osler’s message still relevant to our craft, or has he simply become an icon of professional nostalgia with little value for our times?

THE NEED FOR THE HUMANITIES IN MEDICINE

Medicine has certainly grown both powerful and successful. Yet it is also confronting hurdles that would have been unimaginable in Osler’s time. Physicians are now the professionals with the highest suicide rate,2 a burnout rate as high as 70%,3,4 rampant depression,5 dwindling empathy,6 a predominantly negative perception by the public,7,8 and a disturbing propensity to quit.9 These, of course, may just be symptoms of an increasingly meaningless environment wherein doctors have become small cogs in a medical-industrial complex they can’t control or even understand. Still, is it possible that something more personal may have been lost in the way we now select and educate physicians? Could this, in turn, make us less resilient?

In this regard, Osler’s last public speech serves as an enduring reminder of the need for the humanities in medicine. Osler not only believed it, but throughout his life never missed a chance to express in words, writings, and deeds that the humanities are indeed “the hormones” of the profession. In 1919 he warned against the risk of separating our humanistic tradition from the sciences, and urged us “to infect [anyone] with the spirit of the Humanities,” since to him that was “the greatest single gift in education.”1

Unfortunately, the humanities are slippery, not easily quantifiable, hard to define, and seemingly incompatible with an evidence-based approach. Quite understandably, today’s data-obsessed medicine views them with suspicion. But besides reminding us that in medicine not all that counts can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts, the humanities are in fact a fundamental component of the physician’s skill set.

In a multicenter survey of 5 medical schools,10 there was indeed a correlation between students’ exposure to the humanities and many of the personal qualities whose absence we lament in today’s medicine: empathy, tolerance for ambiguity, emotional intelligence, and prevention of burnout. Most significant was a strong correlation with wisdom, as measured by the 21-item Brief Wisdom Screening Scale.11 That all these traits may correlate with humanities exposure is intuitive, since the humanities not only teach tolerance and compassion, but also capture the collective experience of those who came before us. Hence, they teach us wisdom. Wisdom is not an ACGME competency, but it’s undoubtedly a prerequisite for the art of healing.12 In fact, wisdom may very well be the fundamental trait that characterizes a well-rounded physician, since it encompasses empathy, resilience, comfort with ambiguity, and the capacity to learn from the past. Not surprisingly, wisdom in the world was Osler’s closing wish in 1919.

The humanities can also nurture the very personal qualities we desire in physicians. For example, observing drama fosters empathy,13 as does taking an elective in medical humanities.14 Drawing enhances the reading of faces,15 and observing art improves the art of clinical observation.16 Reading good literature prompts better detection of emotions,17 and reflective writing improves students’ well-being.18 Playing a musical instrument reduces burnout.19 And an undergraduate major in the humanities correlates with greater tolerance for ambiguity,20 a highly desirable trait in physicians, since it means openness to new ideas and the capacity to better cope with difficult situations.21

In fact, some of the qualities fostered by the humanities even translate into better patient care. For instance, tolerance for ambiguity correlates with more positive attitudes towards patients who have frustrating complaints,22 with lower use of resources,23 and with a career choice in direct patient care.24 Hence, it has been suggested that it should be a prerequisite for medical school admission.25 Physicians’ empathy is also beneficial, since it correlates with a lower rate of complications and better outcomes in the care of diabetic patients.26 This should not come as a surprise. As Hippocrates put it 2,500 years ago, “some patients, though conscious that their condition is perilous, recover their health simply through their contentment with the goodness of the physician.”27

Lastly, studying the humanities may provide crucial antibodies against the pain and suffering that are unavoidable staples of the human condition. To paraphrase Osler, the humanities might vaccinate us against the difficulties of our profession. Hippocrates himself had suggested that “it is well to superintend the sick to make them well, to care for the healthy to keep them well, but also to care for one’s self…”27 That is why many institutions now require medical students to take humanities courses.28

MEDICINE: AN ART BASED ON SCIENCE

Yet this effort may amount to a rearguard action that arrives too late and provides too little. The humanities should probably be taught before medical school.29 After all, if it’s possible to make a scientist out of a humanist (Osler was living proof), the experience of the past decades seems to suggest that it’s considerably harder to make a humanist out of a scientist—hence the need to revisit undergraduate curricula and admission criteria to medical school, so that students can receive an adequate foundation in both arenas. Ironically, students express positive attitudes toward a liberal education and think it would actually help them as physicians.30 Yet they also understand that the selection process remains tilted towards the sciences.30–32

For Osler, scientific evidence was important but not a substitute for a humanistic approach. As he reminded students, “The practice of medicine is an art based on science,”33 whose main goals are to prevent disease, relieve suffering, and heal the sick. To do so, one ought to care more “for the individual patient than for the special features of the disease.”34 But he warned them, “It is much harder to acquire the art than the science.”35 In fact, “The practice of medicine is a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.”33 Hence the need to “cultivate equally well hearts and heads.”34 Almost foreseeing our infatuation with guidelines, he also warned against turning medicine into assembly-line work. There are “two great types of practitioners—the routinist and the rationalist,” he said in 1900, and “into the clutches of the demon routine the majority of us ultimately come.”36

Like most great people, Osler was a man of lights, shadows, and contradictions, probably not quite the saint we wish to believe. Yet he provides insights that are as valid today as they were for his own times, and possibly even more so. His 1919 speech is a paean to the humanities, but also a potential eulogy. As a Victorian physician, Osler was a blend of the new science and the old humanities. He knew that “the old art cannot possibly be replaced by, but must be absorbed in, the new science.”35 Yet he could also see the upcoming split between the two cultures, and he tried to warn us. He could in fact foresee the end of an entire way of life. As he said in his address, “there must be a very different civilization or there will be no civilization at all.”1

The crisis we face in medicine today may indeed be a symptom of a much larger cultural shift. As Osler himself put it, “The philosophies of one age have become the absurdities of the next, and the foolishness of yesterday has become the wisdom of tomorrow.”33 Like Osler, we live in times of transition that require us to act. If in 1910 Flexner gave us science,37 Osler in 1919 reminded us that medicine also needs the humanities. We ought to heed his message and reconcile the two fields. The alternative is a future full of tricorders and burned-out technicians, but sorely lacking in healers.

- Osler W. The old humanities and the new science: the presidential address delivered before the Classical Association at Oxford, May, 1919. Br Med J 1919; 2(3053):1–7. pmid:20769536

- Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med 2007; 37(8):1131–1140. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000487

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(12):1600–1613. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(5):334–341. pmid:18765703

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015; 314(22):2373–2383. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ 2004; 38(9):934–941. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x

- Flores G. Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: the portrayal of physicians in the movies. J Natl Med Assoc 2002; 94(7):635–658. pmid:12126293

- Imber JB. Trusting Doctors: The Decline of Moral Authority in American Medicine. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2008.

- Krauthammer, C. Why doctors quit. The Washington Post. May 28, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-doctors-quit/2015/05/28/1e9d8e6e-056f-11e5-a428-c984eb077d4e_story.html?utm_term=.aa8804a518db. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Mangione S, Chakraborti C, Staltari G, et al. Medical students' exposure to the humanities correlates with positive personal qualities and reduced burnout: a multi-institutional US survey. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33(5):628–634. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4275-8

- Glück J, König S, Naschenweng K, et al. How to measure wisdom: content, reliability, and validity of five measures. Front Psychol 2013; 4:405. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00405

- Papagiannis A. Eliot’s triad: information, knowledge and wisdom in medicine. Hektoen International. Spring 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/01/29/eliots-triad-information-knowledge-and-wisdom-in-medicine. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach 2013; 35(12):996–1001. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.802300

- Graham J, Benson LM, Swanson J, Potyk D, Daratha K, Roberts K. Medical humanities coursework is associated with greater measured empathy in medical students. Am J Med 2016; 129(12):1334–1337. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.005

- Brechet C, Baldy R, Picard D. How does Sam feel? Children's labelling and drawing of basic emotions. Br J Dev Psychol 2009; 27(Pt 3):587–606. pmid:19994570

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23(7):991–997. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0

- Kidd DC, Castano E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 2013; 342(6156):377–380. doi:10.1126/science.1239918

- Shapiro J, Kasman D, Shafer A. Words and wards: a model of reflective writing and its uses in medical education. J Med Humanit 2006; 27(4):231–244. doi:10.1007/s10912-006-9020-y

- Bittman BB, Snyder C, Bruhn KT, et al. Recreational music-making: an integrative group intervention for reducing burnout and improving mood states in first year associate degree nursing students: insights and economic impact. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2004;1:Article12. doi:10.2202/1548-923x.1044

- DeForge BR, Sobal J. Intolerance of ambiguity in students entering medical school. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28(8):869–874. pmid:2705020

- Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India 2004; 52:739–742. pmid:15839454

- Merrill JM, Camacho Z, Laux LF, Thornby JI, Vallbona C. How medical school shapes students’ orientation to patients’ psychological problems. Acad Med 1991; 66(9 suppl):S4–S6. pmid:1930523

- Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, Gerrity MS, Orav EJ, Centor R. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Making 1998; 18(3):320–329. doi:10.1177/0272989X9801800310

- Gerrity MS, Earp JAL, DeVilles RF, DW Light. Uncertainty and professional work: perceptions of physicians in clinical practice. Am J Sociol 1992; 97(4):1022–1051. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2781505. Accessed March 6, 2019.

- Geller G. Tolerance for ambiguity: an ethics-based criterion for medical student selection. Acad Med 2013; 88(5):581–584. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828a4b8e

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med 2011; 86(3):359–364. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1

- Hippocrates. Precepts. Section 8, Part VI. Perseus Digital Library. http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekFeb2011&getid=1&query=Hipp.%20Praec.%208. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Kidd MG, Connor JT. Striving to do good things: teaching humanities in Canadian medical schools. J Med Humanit 2008; 29(1):45–54. doi:10.1007/s10912-007-9049-6

- Thomas L. Notes of a biology-watcher. How to fix the premedical curriculum. N Engl J Med 1978; 298(21):1180–1181. doi:10.1056/NEJM197805252982106

- Simmons A. Beyond the premedical syndrome: premedical student attitudes toward liberal education and implications for advising. NACADA Journal 2005; 25(1):64–73.

- Kumar B, Swee ML and Suneja M. The premedical curriculum: we can do better for future physicians. South Med J 2017; 110(8):538–539. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000683

- Gunderman RB, Kanter SL. Perspective: “how to fix the premedical curriculum” revisited. Acad Med 2008; 83(12):1158–1161. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c6515

- Osler W. Aequanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Blakiston; 1904.

- Osler W. Address to the students of the Albany Medical College. Albany Med Ann 1899; 20:307–309.

- Osler W. The reserves of life. St Mary’s Hosp Gaz 1907; 13:95–98.

- Osler W. An address on the importance of post-graduate study. Delivered at the opening of the Museums of the Medical Graduates College and Polyclinic, July 4th, 1900. Br Med J 1900; 2(2063):73–75. pmid:20759107

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York, The Carnegie Foundation 1910.

- Osler W. The old humanities and the new science: the presidential address delivered before the Classical Association at Oxford, May, 1919. Br Med J 1919; 2(3053):1–7. pmid:20769536

- Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med 2007; 37(8):1131–1140. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000487

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(12):1600–1613. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(5):334–341. pmid:18765703

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015; 314(22):2373–2383. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ 2004; 38(9):934–941. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x

- Flores G. Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: the portrayal of physicians in the movies. J Natl Med Assoc 2002; 94(7):635–658. pmid:12126293

- Imber JB. Trusting Doctors: The Decline of Moral Authority in American Medicine. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2008.

- Krauthammer, C. Why doctors quit. The Washington Post. May 28, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-doctors-quit/2015/05/28/1e9d8e6e-056f-11e5-a428-c984eb077d4e_story.html?utm_term=.aa8804a518db. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Mangione S, Chakraborti C, Staltari G, et al. Medical students' exposure to the humanities correlates with positive personal qualities and reduced burnout: a multi-institutional US survey. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33(5):628–634. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4275-8

- Glück J, König S, Naschenweng K, et al. How to measure wisdom: content, reliability, and validity of five measures. Front Psychol 2013; 4:405. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00405

- Papagiannis A. Eliot’s triad: information, knowledge and wisdom in medicine. Hektoen International. Spring 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/01/29/eliots-triad-information-knowledge-and-wisdom-in-medicine. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach 2013; 35(12):996–1001. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.802300

- Graham J, Benson LM, Swanson J, Potyk D, Daratha K, Roberts K. Medical humanities coursework is associated with greater measured empathy in medical students. Am J Med 2016; 129(12):1334–1337. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.005

- Brechet C, Baldy R, Picard D. How does Sam feel? Children's labelling and drawing of basic emotions. Br J Dev Psychol 2009; 27(Pt 3):587–606. pmid:19994570

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23(7):991–997. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0667-0

- Kidd DC, Castano E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science 2013; 342(6156):377–380. doi:10.1126/science.1239918

- Shapiro J, Kasman D, Shafer A. Words and wards: a model of reflective writing and its uses in medical education. J Med Humanit 2006; 27(4):231–244. doi:10.1007/s10912-006-9020-y

- Bittman BB, Snyder C, Bruhn KT, et al. Recreational music-making: an integrative group intervention for reducing burnout and improving mood states in first year associate degree nursing students: insights and economic impact. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2004;1:Article12. doi:10.2202/1548-923x.1044

- DeForge BR, Sobal J. Intolerance of ambiguity in students entering medical school. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28(8):869–874. pmid:2705020

- Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India 2004; 52:739–742. pmid:15839454

- Merrill JM, Camacho Z, Laux LF, Thornby JI, Vallbona C. How medical school shapes students’ orientation to patients’ psychological problems. Acad Med 1991; 66(9 suppl):S4–S6. pmid:1930523

- Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, Gerrity MS, Orav EJ, Centor R. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Making 1998; 18(3):320–329. doi:10.1177/0272989X9801800310

- Gerrity MS, Earp JAL, DeVilles RF, DW Light. Uncertainty and professional work: perceptions of physicians in clinical practice. Am J Sociol 1992; 97(4):1022–1051. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2781505. Accessed March 6, 2019.

- Geller G. Tolerance for ambiguity: an ethics-based criterion for medical student selection. Acad Med 2013; 88(5):581–584. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828a4b8e

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med 2011; 86(3):359–364. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1

- Hippocrates. Precepts. Section 8, Part VI. Perseus Digital Library. http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekFeb2011&getid=1&query=Hipp.%20Praec.%208. Accessed March 4, 2019.

- Kidd MG, Connor JT. Striving to do good things: teaching humanities in Canadian medical schools. J Med Humanit 2008; 29(1):45–54. doi:10.1007/s10912-007-9049-6

- Thomas L. Notes of a biology-watcher. How to fix the premedical curriculum. N Engl J Med 1978; 298(21):1180–1181. doi:10.1056/NEJM197805252982106

- Simmons A. Beyond the premedical syndrome: premedical student attitudes toward liberal education and implications for advising. NACADA Journal 2005; 25(1):64–73.

- Kumar B, Swee ML and Suneja M. The premedical curriculum: we can do better for future physicians. South Med J 2017; 110(8):538–539. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000683

- Gunderman RB, Kanter SL. Perspective: “how to fix the premedical curriculum” revisited. Acad Med 2008; 83(12):1158–1161. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c6515

- Osler W. Aequanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Blakiston; 1904.

- Osler W. Address to the students of the Albany Medical College. Albany Med Ann 1899; 20:307–309.

- Osler W. The reserves of life. St Mary’s Hosp Gaz 1907; 13:95–98.

- Osler W. An address on the importance of post-graduate study. Delivered at the opening of the Museums of the Medical Graduates College and Polyclinic, July 4th, 1900. Br Med J 1900; 2(2063):73–75. pmid:20759107

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York, The Carnegie Foundation 1910.

When the tail wags the dog: Clinical skills in the age of technology

“... with the rapid extension of laboratory tests of greater accuracy, there is a tendency for some clinicians and hence for some students in reaching a diagnosis to rely more on laboratory reports and less on the history of the illness, the examination and behavior of the patient and clinical judgment. While in many cases laboratory findings are invaluable for reaching correct conclusions, the student should never be allowed to forget that it takes a man, not a machine, to understand a man.”

—Raymond B. Allen, MD, PhD, 19461

From Hippocrates onward, accurate diagnosis has always been the prerequisite for prognosis and treatment. Physicians typically diagnosed through astute interviewing, deductive reasoning, and skillful use of observation and touch. Then, in the past 250 years they added 2 more tools to their diagnostic skill set: percussion and auscultation, the dual foundation of bedside assessment. Intriguingly, both these skills were first envisioned by multifaceted minds: percussion by Leopold Auenbrugger, an Austrian music-lover who even wrote librettos for operas; and stethoscopy by René Laennec, a Breton flutist, poet, and dancer—not exactly the kind of doctors we tend to produce today.

Still, the point of this preamble is not to say that eclecticism may help creativity (it does), but to remind ourselves that it has only been for a century or so that physicians have been able to rely on laboratory and radiologic studies. In fact, the now ubiquitous and almost obligatory imaging tests (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron-emission tomography, and ultrasonography) have been available to practitioners for only threescore years or less. Yet tests have become so dominant in our culture that it is hard to imagine a time when physicians could count only on their wit and senses.

CLINICAL SKILLS ARE STILL RELEVANT

Ironically, many studies tell us that history and bedside examination can still deliver most diagnoses.2,3 In fact, clinical skills can solve even the most perplexing dilemmas. In an automated analysis of the clinicopathologic conference cases presented in the New England Journal of Medicine,4 history and physical examination still yielded a correct diagnosis in 64% of those very challenging patients.

Bedside examination may be especially important in the hospital. In a study of inpatients,5 physical examination detected crucial findings in one-fourth of the cases and prompted management changes in many others. As the authors concluded, sick patients need careful examination, the more skilled the better.

Unfortunately, errors in physical examination are common. In a recent review of 208 cases, 63% of oversights were due to failure to perform an examination, while 25% were either missed or misinterpreted findings.6 These errors interfered with diagnosis in three-fourths of the cases, and with treatment in half.

Which brings us to the interesting observation by Kondo et al,7 who in this issue of the Journal report how the lowly physical examination proved more helpful than expensive magnetic resonance imaging in evaluating a perplexing case of refractory shoulder pain.