User login

Narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Pelvic organ prolapse: Effective treatments

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

When to consider external cephalic version

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material often tested on board exams. In February 2016, ACOG issued a revised Practice Bulletin (#161) on external cephalic version outlining clinical considerations and recommendations and providing an algorithm for patient management.1 We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: According to the Practice Bulletin, which of the following is TRUE about external cephalic version (ECV)?

A. Success rate is lower in women with a previous cesarean delivery.

B. Placental location affects the success rate.

C. External cephalic version should be stopped after 15 minutes.

D. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are preferred candidates.

E. Tocolysis decreases success rate.

The correct answer is D.

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV because spontaneous version would likely have already occurred by this time and the risk of spontaneous reversion is lower. Answers A-C and E are incorrect statements.

Key points

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV.

The overall pooled success rate for ECV is 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate.

The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

Literature summary

ECV is a procedure designed to turn a fetus into vertex presentation by applying external pressure to a woman’s abdomen. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates. At this gestational age, spontaneous version is most likely to have occurred, and there is decreased risk of spontaneous reversion after the ECV. All patients who are near term and found to have a fetus in a nonvertex presentation should be offered an ECV as long as there are no contraindications to the procedure. ECV is not appropriate for women who have a contraindication to a vaginal delivery.

There are limited studies of ECV in women who undergo the procedure in early labor and in those who have had a previous uterine surgery. ECV success rates are not affected by a previous cesarean delivery, though the risks of uterine rupture are not clear. The procedure should be attempted only in settings where cesarean delivery services are immediately available.

The success rates of ECV have been reported to be anywhere from 16% to 100%, with an overall pooled success of 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate. Some studies have documented higher success rates with higher parity and a transverse or oblique fetal lie. However, placental location, maternal weight, and amniotic fluid volume have not been consistently found to be predictive of ECV success. The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

ECV should be stopped in the face of a prolonged or significant fetal bradycardia or if the patient is experiencing intolerable levels of discomfort. However, there are no guidelines to recommend the total time limit of the procedure. After the ECV, there should be fetal heart rate monitoring for at least 30 minutes and anti-D immune globulin should be administered to those women who are Rh-negative if delivery is not anticipated in the next 72 hours.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material often tested on board exams. In February 2016, ACOG issued a revised Practice Bulletin (#161) on external cephalic version outlining clinical considerations and recommendations and providing an algorithm for patient management.1 We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: According to the Practice Bulletin, which of the following is TRUE about external cephalic version (ECV)?

A. Success rate is lower in women with a previous cesarean delivery.

B. Placental location affects the success rate.

C. External cephalic version should be stopped after 15 minutes.

D. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are preferred candidates.

E. Tocolysis decreases success rate.

The correct answer is D.

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV because spontaneous version would likely have already occurred by this time and the risk of spontaneous reversion is lower. Answers A-C and E are incorrect statements.

Key points

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV.

The overall pooled success rate for ECV is 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate.

The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

Literature summary

ECV is a procedure designed to turn a fetus into vertex presentation by applying external pressure to a woman’s abdomen. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates. At this gestational age, spontaneous version is most likely to have occurred, and there is decreased risk of spontaneous reversion after the ECV. All patients who are near term and found to have a fetus in a nonvertex presentation should be offered an ECV as long as there are no contraindications to the procedure. ECV is not appropriate for women who have a contraindication to a vaginal delivery.

There are limited studies of ECV in women who undergo the procedure in early labor and in those who have had a previous uterine surgery. ECV success rates are not affected by a previous cesarean delivery, though the risks of uterine rupture are not clear. The procedure should be attempted only in settings where cesarean delivery services are immediately available.

The success rates of ECV have been reported to be anywhere from 16% to 100%, with an overall pooled success of 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate. Some studies have documented higher success rates with higher parity and a transverse or oblique fetal lie. However, placental location, maternal weight, and amniotic fluid volume have not been consistently found to be predictive of ECV success. The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

ECV should be stopped in the face of a prolonged or significant fetal bradycardia or if the patient is experiencing intolerable levels of discomfort. However, there are no guidelines to recommend the total time limit of the procedure. After the ECV, there should be fetal heart rate monitoring for at least 30 minutes and anti-D immune globulin should be administered to those women who are Rh-negative if delivery is not anticipated in the next 72 hours.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material often tested on board exams. In February 2016, ACOG issued a revised Practice Bulletin (#161) on external cephalic version outlining clinical considerations and recommendations and providing an algorithm for patient management.1 We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: According to the Practice Bulletin, which of the following is TRUE about external cephalic version (ECV)?

A. Success rate is lower in women with a previous cesarean delivery.

B. Placental location affects the success rate.

C. External cephalic version should be stopped after 15 minutes.

D. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are preferred candidates.

E. Tocolysis decreases success rate.

The correct answer is D.

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV because spontaneous version would likely have already occurred by this time and the risk of spontaneous reversion is lower. Answers A-C and E are incorrect statements.

Key points

Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates for an ECV.

The overall pooled success rate for ECV is 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate.

The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

Literature summary

ECV is a procedure designed to turn a fetus into vertex presentation by applying external pressure to a woman’s abdomen. Women at 37 weeks’ gestation are the preferred candidates. At this gestational age, spontaneous version is most likely to have occurred, and there is decreased risk of spontaneous reversion after the ECV. All patients who are near term and found to have a fetus in a nonvertex presentation should be offered an ECV as long as there are no contraindications to the procedure. ECV is not appropriate for women who have a contraindication to a vaginal delivery.

There are limited studies of ECV in women who undergo the procedure in early labor and in those who have had a previous uterine surgery. ECV success rates are not affected by a previous cesarean delivery, though the risks of uterine rupture are not clear. The procedure should be attempted only in settings where cesarean delivery services are immediately available.

The success rates of ECV have been reported to be anywhere from 16% to 100%, with an overall pooled success of 58% with a 6% pooled complication rate. Some studies have documented higher success rates with higher parity and a transverse or oblique fetal lie. However, placental location, maternal weight, and amniotic fluid volume have not been consistently found to be predictive of ECV success. The use of parenteral tocolysis has been associated with increased success rates of ECV, though there are not enough data to make a recommendation regarding use of regional anesthesia with the procedure.

ECV should be stopped in the face of a prolonged or significant fetal bradycardia or if the patient is experiencing intolerable levels of discomfort. However, there are no guidelines to recommend the total time limit of the procedure. After the ECV, there should be fetal heart rate monitoring for at least 30 minutes and anti-D immune globulin should be administered to those women who are Rh-negative if delivery is not anticipated in the next 72 hours.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Treating gonococcal infections

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a six-part monthly series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

Management of sexually transmitted infections will always be tested on any ob.gyn. examination. Since the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued two new committee opinions in 2015 focusing on the dual treatment for gonococcal infections and expedited partner therapy in the management of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection, it is wise to review this topic.1,2

A. Ciprofloxacin

B. Ciprofloxacin plus azithromycin

C. Cefixime plus azithromycin

D. Doxycycline plus azithromycin

E. Gentamicin plus azithromycin

The correct answer is E.

Dual therapy with gentamicin (240 mg single-intramuscular dose) and azithromycin (2 grams single-oral dose) is the treatment of choice for pregnant patients with severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Gentamicin is safe during pregnancy. An alternative regimen is a single dose of azithromycin, if the patient is allergic to gentamicin and cephalosporin. For this patient, the physician needs to perform a test-of-cure 1 week after treatment.

Answer A is incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Answer B and C are incorrect because the patient is allergic to cephalosporin (ceftriaxone and cefixime).

Answer D in incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

- Ceftriaxone and azithromycin must be started on the same day.

- In patients with HIV, the treatment is same: Ceftriaxone 250-mg single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g single-oral dose.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments will periodically update the most current information on gonococcal susceptibility.

- Despite nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) being negative for Chlamydia trachomatis, dual treatment with a cephalosporin plus either azithromycin or doxycycline is recommended by ACOG to prevent resistance to cephalosporins.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of pregnant patients.

- ACOG recommends test-of-cure for pharyngeal gonorrhea only if the patient received an alternative regimen treatment after 14 days.

- ACOG accepts both culture or NAAT as a test-of-cure.

- Cefixime is not a first-line regimen treatment for gonorrhea and dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only recommended first-line regimen.

Literature summary

The guidelines from the ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice outline recommended antibiotic treatment regimens, considerations when treating special populations, and advice for expedited therapy for sexual partners.

- The first-line regimen is ceftriaxone 250-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- The second-line regimen takes into account allergies and shortages. In the case of a severe penicillin allergy, use gemifloxacin 320-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. Another option is gentamicin, 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. When ceftriaxone is not available, ACOG recommends cefixime, 400-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- In pregnancy, ACOG recommends the same treatment, with no need for test-of-cure if treated properly. For severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy in pregnancy, use gentamicin 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. For allergy to gentamicin and cephalosporins, use azithromycin 2-g single-oral dose and send a test-of-cure in 1 week. Do not use doxycycline or quinolones during pregnancy.

- In HIV infection, use the general recommended treatment regimen and there is no need for a test-of-cure if treated properly.

- For sex partners, ACOG recommends evaluation and treatment for partners in the last 60 days. They should abstain from sex for 7 days after treatment. Expedited partner therapy with cefixime and azithromycin is recommended, but review the legal the status of expedited partner therapy in your state before prescribing.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;126(5):e95-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;125(6):1526-8.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a six-part monthly series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

Management of sexually transmitted infections will always be tested on any ob.gyn. examination. Since the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued two new committee opinions in 2015 focusing on the dual treatment for gonococcal infections and expedited partner therapy in the management of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection, it is wise to review this topic.1,2

A. Ciprofloxacin

B. Ciprofloxacin plus azithromycin

C. Cefixime plus azithromycin

D. Doxycycline plus azithromycin

E. Gentamicin plus azithromycin

The correct answer is E.

Dual therapy with gentamicin (240 mg single-intramuscular dose) and azithromycin (2 grams single-oral dose) is the treatment of choice for pregnant patients with severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Gentamicin is safe during pregnancy. An alternative regimen is a single dose of azithromycin, if the patient is allergic to gentamicin and cephalosporin. For this patient, the physician needs to perform a test-of-cure 1 week after treatment.

Answer A is incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Answer B and C are incorrect because the patient is allergic to cephalosporin (ceftriaxone and cefixime).

Answer D in incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

- Ceftriaxone and azithromycin must be started on the same day.

- In patients with HIV, the treatment is same: Ceftriaxone 250-mg single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g single-oral dose.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments will periodically update the most current information on gonococcal susceptibility.

- Despite nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) being negative for Chlamydia trachomatis, dual treatment with a cephalosporin plus either azithromycin or doxycycline is recommended by ACOG to prevent resistance to cephalosporins.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of pregnant patients.

- ACOG recommends test-of-cure for pharyngeal gonorrhea only if the patient received an alternative regimen treatment after 14 days.

- ACOG accepts both culture or NAAT as a test-of-cure.

- Cefixime is not a first-line regimen treatment for gonorrhea and dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only recommended first-line regimen.

Literature summary

The guidelines from the ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice outline recommended antibiotic treatment regimens, considerations when treating special populations, and advice for expedited therapy for sexual partners.

- The first-line regimen is ceftriaxone 250-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- The second-line regimen takes into account allergies and shortages. In the case of a severe penicillin allergy, use gemifloxacin 320-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. Another option is gentamicin, 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. When ceftriaxone is not available, ACOG recommends cefixime, 400-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- In pregnancy, ACOG recommends the same treatment, with no need for test-of-cure if treated properly. For severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy in pregnancy, use gentamicin 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. For allergy to gentamicin and cephalosporins, use azithromycin 2-g single-oral dose and send a test-of-cure in 1 week. Do not use doxycycline or quinolones during pregnancy.

- In HIV infection, use the general recommended treatment regimen and there is no need for a test-of-cure if treated properly.

- For sex partners, ACOG recommends evaluation and treatment for partners in the last 60 days. They should abstain from sex for 7 days after treatment. Expedited partner therapy with cefixime and azithromycin is recommended, but review the legal the status of expedited partner therapy in your state before prescribing.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;126(5):e95-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;125(6):1526-8.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a six-part monthly series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips.

Management of sexually transmitted infections will always be tested on any ob.gyn. examination. Since the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued two new committee opinions in 2015 focusing on the dual treatment for gonococcal infections and expedited partner therapy in the management of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection, it is wise to review this topic.1,2

A. Ciprofloxacin

B. Ciprofloxacin plus azithromycin

C. Cefixime plus azithromycin

D. Doxycycline plus azithromycin

E. Gentamicin plus azithromycin

The correct answer is E.

Dual therapy with gentamicin (240 mg single-intramuscular dose) and azithromycin (2 grams single-oral dose) is the treatment of choice for pregnant patients with severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Gentamicin is safe during pregnancy. An alternative regimen is a single dose of azithromycin, if the patient is allergic to gentamicin and cephalosporin. For this patient, the physician needs to perform a test-of-cure 1 week after treatment.

Answer A is incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Answer B and C are incorrect because the patient is allergic to cephalosporin (ceftriaxone and cefixime).

Answer D in incorrect because neither doxycycline nor quinolones are recommended during pregnancy.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

- Ceftriaxone and azithromycin must be started on the same day.

- In patients with HIV, the treatment is same: Ceftriaxone 250-mg single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g single-oral dose.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments will periodically update the most current information on gonococcal susceptibility.

- Despite nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) being negative for Chlamydia trachomatis, dual treatment with a cephalosporin plus either azithromycin or doxycycline is recommended by ACOG to prevent resistance to cephalosporins.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea.

- ACOG does not recommend test-of-cure after treatment of pregnant patients.

- ACOG recommends test-of-cure for pharyngeal gonorrhea only if the patient received an alternative regimen treatment after 14 days.

- ACOG accepts both culture or NAAT as a test-of-cure.

- Cefixime is not a first-line regimen treatment for gonorrhea and dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only recommended first-line regimen.

Literature summary

The guidelines from the ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice outline recommended antibiotic treatment regimens, considerations when treating special populations, and advice for expedited therapy for sexual partners.

- The first-line regimen is ceftriaxone 250-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- The second-line regimen takes into account allergies and shortages. In the case of a severe penicillin allergy, use gemifloxacin 320-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. Another option is gentamicin, 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. When ceftriaxone is not available, ACOG recommends cefixime, 400-mg, single-oral dose plus azithromycin 1-g, single-oral dose.

- In pregnancy, ACOG recommends the same treatment, with no need for test-of-cure if treated properly. For severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy in pregnancy, use gentamicin 240-mg, single-intramuscular dose plus azithromycin 2-g, single-oral dose. For allergy to gentamicin and cephalosporins, use azithromycin 2-g single-oral dose and send a test-of-cure in 1 week. Do not use doxycycline or quinolones during pregnancy.

- In HIV infection, use the general recommended treatment regimen and there is no need for a test-of-cure if treated properly.

- For sex partners, ACOG recommends evaluation and treatment for partners in the last 60 days. They should abstain from sex for 7 days after treatment. Expedited partner therapy with cefixime and azithromycin is recommended, but review the legal the status of expedited partner therapy in your state before prescribing.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;126(5):e95-9.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;125(6):1526-8.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Zika virus in pregnancy

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on Zika virus.

In 2016, The American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists assigned four maintenance of certification (MOC) articles dealing with Zika virus:

Zika Virus and Pregnancy: What Obstetric Health Care Providers Need to Know1

Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Caring for Women of Reproductive Age with Possible Zika Virus Exposure – United States, 20163

Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak – United States, 20164

The diagnosis and management of Zika virus in pregnancy is a hot topic that should be reviewed before any Obstetrics and Gynecology board exam. This month’s Board Corner will review the key elements for ob.gyns.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following is LEAST LIKELY to be associated with congenital Zika virus infection?

A. Omphalocele

B. Microcephaly

C. Ventriculomegaly

D. Cataract

E. Intracranial calcifications

The correct answer is A.

Omphalocele has not been observed to be associated with Zika virus infection. Answers B-E are incorrect because reported fetal and neonatal abnormalities associated with Zika virus include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

Transmission of Zika virus to humans most commonly occurs from the bite of an infected mosquito. Other modes of transmission have been reported, such as sexual transmission, maternal-fetal transmission, and transmission through blood transfusion.

Infection with Zika virus and maternal-fetal transmission have been documented in all trimesters of pregnancy. Reported fetal and neonatal sequelae include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness. For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation.

Literature summary

Zika virus is a mosquito-borne virus that is most commonly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. This species of mosquito is also known to transmit dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya viruses. Initial data suggest that the incubation period for Zika virus is a few days up to 2 weeks. Acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia are the most common symptoms of Zika infection. Symptoms generally only last up to 7 days and are typically mild. Only about 20% of people infected with the virus become ill. There is currently no specific antiviral treatment available for Zika virus disease.

Testing for Zika virus can include detection of viral RNA, Zika antigen, or antibodies. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be performed on serum, amniotic fluid, and tissue (such as placenta). It is recommended that RT-PCR testing of serum be performed within 7 days of the onset of symptoms. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness.

Though fetal microcephaly can be detected ultrasonographically at 18-20 weeks gestation, the diagnosis can be challenging because there is no standard definition of fetal microcephaly. Because other intracranial abnormalities have been detected in association with congenital Zika infection, a complete ultrasound examination should be performed to assess the fetal neuroanatomy.

For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation. RT-PCR can be used to test for the presence of Zika virus RNA in the amniotic fluid. Patients should be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist for serial ultrasounds to assess fetal anatomy and monitor fetal growth every 3-4 weeks.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Apr;127(4):642-8.

2. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:311-4.

3. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:315-22.

4. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:30-3.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on Zika virus.

In 2016, The American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists assigned four maintenance of certification (MOC) articles dealing with Zika virus:

Zika Virus and Pregnancy: What Obstetric Health Care Providers Need to Know1

Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Caring for Women of Reproductive Age with Possible Zika Virus Exposure – United States, 20163

Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak – United States, 20164

The diagnosis and management of Zika virus in pregnancy is a hot topic that should be reviewed before any Obstetrics and Gynecology board exam. This month’s Board Corner will review the key elements for ob.gyns.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following is LEAST LIKELY to be associated with congenital Zika virus infection?

A. Omphalocele

B. Microcephaly

C. Ventriculomegaly

D. Cataract

E. Intracranial calcifications

The correct answer is A.

Omphalocele has not been observed to be associated with Zika virus infection. Answers B-E are incorrect because reported fetal and neonatal abnormalities associated with Zika virus include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

Transmission of Zika virus to humans most commonly occurs from the bite of an infected mosquito. Other modes of transmission have been reported, such as sexual transmission, maternal-fetal transmission, and transmission through blood transfusion.

Infection with Zika virus and maternal-fetal transmission have been documented in all trimesters of pregnancy. Reported fetal and neonatal sequelae include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness. For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation.

Literature summary

Zika virus is a mosquito-borne virus that is most commonly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. This species of mosquito is also known to transmit dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya viruses. Initial data suggest that the incubation period for Zika virus is a few days up to 2 weeks. Acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia are the most common symptoms of Zika infection. Symptoms generally only last up to 7 days and are typically mild. Only about 20% of people infected with the virus become ill. There is currently no specific antiviral treatment available for Zika virus disease.

Testing for Zika virus can include detection of viral RNA, Zika antigen, or antibodies. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be performed on serum, amniotic fluid, and tissue (such as placenta). It is recommended that RT-PCR testing of serum be performed within 7 days of the onset of symptoms. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness.

Though fetal microcephaly can be detected ultrasonographically at 18-20 weeks gestation, the diagnosis can be challenging because there is no standard definition of fetal microcephaly. Because other intracranial abnormalities have been detected in association with congenital Zika infection, a complete ultrasound examination should be performed to assess the fetal neuroanatomy.

For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation. RT-PCR can be used to test for the presence of Zika virus RNA in the amniotic fluid. Patients should be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist for serial ultrasounds to assess fetal anatomy and monitor fetal growth every 3-4 weeks.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Apr;127(4):642-8.

2. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:311-4.

3. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:315-22.

4. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:30-3.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover issues in reproductive endocrinology and infertility, maternal-fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, and female pelvic medicine, as well as general test-taking and study tips. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on Zika virus.

In 2016, The American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists assigned four maintenance of certification (MOC) articles dealing with Zika virus:

Zika Virus and Pregnancy: What Obstetric Health Care Providers Need to Know1

Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Caring for Women of Reproductive Age with Possible Zika Virus Exposure – United States, 20163

Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak – United States, 20164

The diagnosis and management of Zika virus in pregnancy is a hot topic that should be reviewed before any Obstetrics and Gynecology board exam. This month’s Board Corner will review the key elements for ob.gyns.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following is LEAST LIKELY to be associated with congenital Zika virus infection?

A. Omphalocele

B. Microcephaly

C. Ventriculomegaly

D. Cataract

E. Intracranial calcifications

The correct answer is A.

Omphalocele has not been observed to be associated with Zika virus infection. Answers B-E are incorrect because reported fetal and neonatal abnormalities associated with Zika virus include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Key points

The key points to remember are:

Transmission of Zika virus to humans most commonly occurs from the bite of an infected mosquito. Other modes of transmission have been reported, such as sexual transmission, maternal-fetal transmission, and transmission through blood transfusion.

Infection with Zika virus and maternal-fetal transmission have been documented in all trimesters of pregnancy. Reported fetal and neonatal sequelae include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, intracranial calcifications, brain atrophy, and cataracts.

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness. For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation.

Literature summary

Zika virus is a mosquito-borne virus that is most commonly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. This species of mosquito is also known to transmit dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya viruses. Initial data suggest that the incubation period for Zika virus is a few days up to 2 weeks. Acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia are the most common symptoms of Zika infection. Symptoms generally only last up to 7 days and are typically mild. Only about 20% of people infected with the virus become ill. There is currently no specific antiviral treatment available for Zika virus disease.

Testing for Zika virus can include detection of viral RNA, Zika antigen, or antibodies. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be performed on serum, amniotic fluid, and tissue (such as placenta). It is recommended that RT-PCR testing of serum be performed within 7 days of the onset of symptoms. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) can also be detected as early as 4 days after the onset of illness.

Though fetal microcephaly can be detected ultrasonographically at 18-20 weeks gestation, the diagnosis can be challenging because there is no standard definition of fetal microcephaly. Because other intracranial abnormalities have been detected in association with congenital Zika infection, a complete ultrasound examination should be performed to assess the fetal neuroanatomy.

For those women who have laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection during pregnancy, amniocentesis should be offered after 15 weeks gestation. RT-PCR can be used to test for the presence of Zika virus RNA in the amniotic fluid. Patients should be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist for serial ultrasounds to assess fetal anatomy and monitor fetal growth every 3-4 weeks.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Apr;127(4):642-8.

2. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:311-4.

3. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:315-22.

4. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:30-3.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

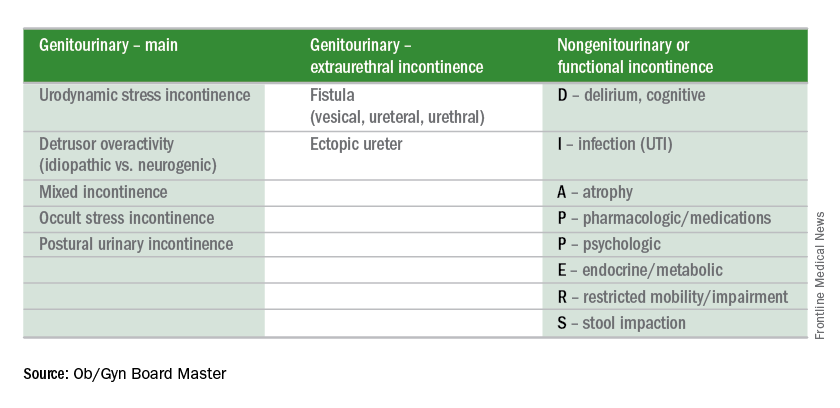

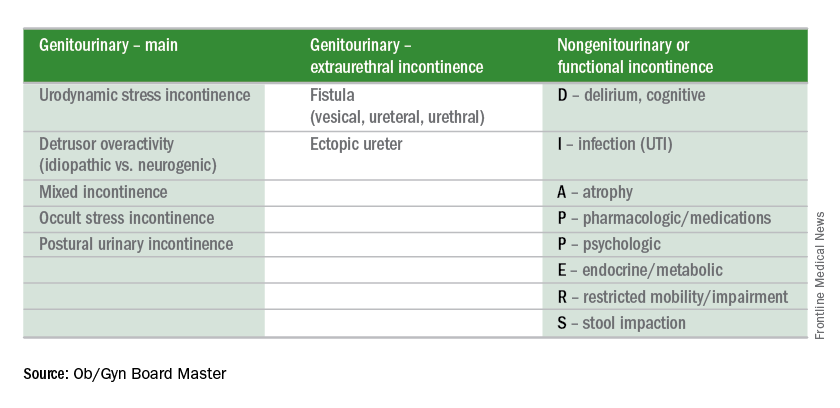

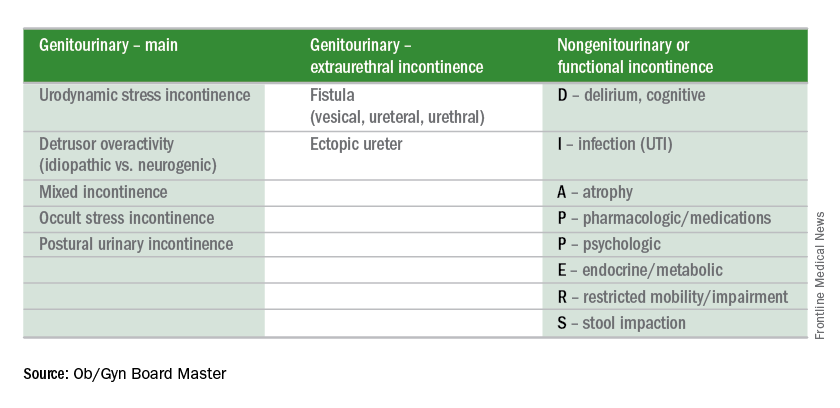

Urinary incontinence

Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte Inc. The series will cover key topics across the specialty, as well as general test-taking and study tips. This month’s edition of the Board Exam Corner focuses on urinary incontinence.

The literature