User login

Functional heartburn: An underrecognized cause of PPI-refractory symptoms

A 44-year-old woman presents with an 8-year history of intermittent heartburn, and in the past year she has been experiencing her symptoms daily. She says the heartburn is constant and is worse immediately after eating spicy or acidic foods. She says she has had no dysphagia, weight loss, or vomiting. Her symptoms have persisted despite taking a histamine (H)2-receptor antagonist twice daily plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) before breakfast and dinner for more than 3 months.

She has undergone upper endoscopy 3 times in the past 8 years. Each time, the esophagus was normal with a regular Z-line and normal biopsy results from the proximal and distal esophagus.

The patient believes she has severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and asks if she is a candidate for fundoplication surgery.

HEARTBURN IS A SYMPTOM; GERD IS A CONDITION

A distinction should be made between heartburn—the symptom of persistent retrosternal burning and discomfort—and gastroesophageal reflux disease—the condition in which reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications.1 While many clinicians initially diagnose patients who have heartburn as having GERD, there are many other potential causes of their symptoms.

For patients with persistent heartburn, an empiric trial of a once-daily PPI is usually effective, but one-third of patients continue to have heartburn.2,3 The most common cause of this PPI-refractory heartburn is functional heartburn, a functional or hypersensitivity disorder of the esophagus.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY IS POORLY UNDERSTOOD

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Clinicians have several tests available for diagnosing these conditions.

Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is recommended for patients with heartburn that does not respond to a 3-month trial of a PPI.9 Endoscopy is also indicated in any patient who has any of the following “alarm symptoms” that could be due to malignancy or peptic ulcer:

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss or anemia

- Signs of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Anorexia

- New onset of dyspepsia in a patient over age 60.

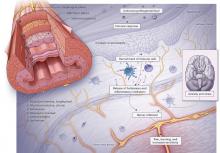

During upper endoscopy, the esophagus is evaluated for reflux esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and other inflammatory disorders such as infectious esophagitis. But even if the esophageal mucosa appears normal, the proximal and distal esophagus should be biopsied to rule out an inflammatory disorder such as eosinophilic or lymphocytic esophagitis.

Esophageal manometry

If endoscopic and esophageal biopsy results are inconclusive, a workup for an esophageal motility disorder is the next step. Dysphagia is the most common symptom of these disorders, although the initial presenting symptom may be heartburn or regurgitation that persists despite PPI therapy.

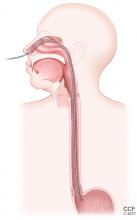

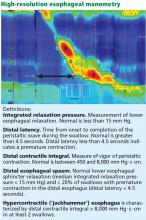

Manometry is used to test for motility disorders such as achalasia and esophageal spasm.10 After applying a local anesthetic inside the nares, the clinician inserts a flexible catheter (about 4 mm in diameter) with 36 pressure sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals into the nares and passes it through the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter. The patient then swallows liquid, and the sensors relay the esophageal response, creating a topographic plot that shows esophageal peristalsis and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

Achalasia is identified by incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation combined with 100% failed peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. Esophageal spasms are identified by a shortened distal latency, which corresponds to premature contraction of the esophagus during peristalsis.11

Esophageal pH testing

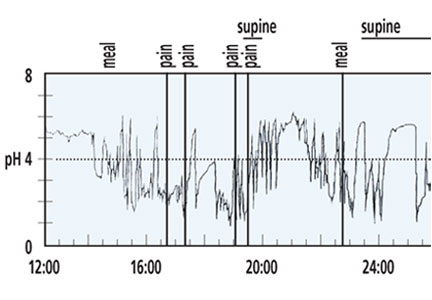

Measuring esophageal pH levels is an important step to quantify gastroesophageal reflux and determine if symptoms occur during reflux events. According to the updated Porto GERD consensus group recommendations,12 a pH test is positive if the acid exposure time is greater than 6% of the testing period. Testing the pH differentiates between GERD (abnormal acid exposure), reflux hypersensitivity (normal acid exposure, strong correlation between symptoms and reflux events), and functional heartburn (normal acid exposure, negative correlation between reflux events and symptoms).5 For this test, a pH probe is placed in the esophagus transnasally or endoscopically. The probe records esophageal pH levels for 24 to 96 hours in an outpatient setting. Antisecretory therapy needs to be withheld for 7 to 10 days before the test.

Transnasal pH probe. For this approach, a thin catheter is inserted through the nares and advanced until the tip is 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. (The placement is guided by the results of esophageal manometry, which is done immediately before pH catheter placement.) The tube is secured with clear tape on the side of the patient’s face, and the end is connected to a portable recorder that compiles the data. The patient pushes a button on the recorder when experiencing heartburn symptoms. (A nurse instructs the patient on proper procedure.) After 24 hours, the patient either removes the catheter or has the clinic remove it. The pH and symptom data are downloaded and analyzed.

Transnasal pH testing can be combined with impedance measurement, which can detect nonacid reflux or weakly acid reflux. However, the clinical significance of this measurement is unclear, as multiple studies have found total acid exposure time to be a better predictor of response to therapy than weakly acid or nonacid reflux.12

Wireless pH probe. This method uses a disposable, catheter-free, capsule device to measure esophageal pH. The capsule, about the size of a gel capsule or pencil eraser, is attached to the patient’s esophageal lining, usually during upper endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels in the lower esophagus for 48 to 96 hours and transmits the data wirelessly to a receiver the patient wears. The patient pushes buttons on the receiver to record symptom-specific data when experiencing heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, or cough. The capsule detaches from the esophagus spontaneously, generally within 7 days, and is passed out of the body through a bowel movement.

Diagnosing functional heartburn

CASE CONTINUED: NORMAL RESULTS ON TESTING

Based on these results, her condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn, consistent with the Rome IV criteria.5

TREATMENT

Patient education is key

Patient education about the pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment options is the most important aspect of treating any functional gastrointestinal disorder. This includes the “brain-gut connection” and potential mechanisms of dysregulation. Patient education along with assessment of symptoms should be part of every visit, especially before discussing treatment options.

Patients whose condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn need reassurance that the condition is benign and, in particular, that the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is minimal in the absence of Barrett esophagus.13 Also important to point out is that the disorder may spontaneously resolve: resolution rates of up to 40% have been reported for other functional gastrointestinal disorders.14

Antisecretory medications may work for some

A PPI or H2-receptor antagonist is the most common first-line treatment for heartburn symptoms. Although most patients with functional heartburn experience no improvement in symptoms with an antisecretory agent, a small number report some relief, which suggests that acid-suppression therapy may have an indirect impact on pain modulation in the esophagus.15 In patients who report symptom relief with an antisecretory agent, we suggest continuing the medication tapered to the lowest effective dose, with repeated reassurance that the medication can be discontinued safely at any time.

Antireflux surgery should be avoided

Antireflux surgery should be avoided in patients with normal pH testing and no objective finding of reflux, as this is associated with worse subjective outcomes than in patients with abnormal pH test results.16

Neuromodulators

It is important to discuss with patients the concept of neuromodulation, including the fact that antidepressants are often used because of their effects on serotonin and norepinephrine, which decrease visceral hypersensitivity.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram has been shown to reduce esophageal hypersensitivity,17 and a tricyclic antidepressant has been shown to improve quality of life.18 These results have led experts to recommend a trial of a low dose of either type of medication.19 The dose of tricyclic antidepressant often needs to be increased sequentially every 2 to 4 weeks.

Interestingly, melatonin 6 mg at bedtime has also shown efficacy for functional heartburn, potentially due to its antinociceptive properties.20

Alternative and complementary therapies

Many esophageal centers use cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy as first-line treatment for functional esophageal disorders. Here again, it is important for the patient to understand the rationale of therapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders, given the stigma in the general population regarding psychotherapy.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been used for functional gastrointestinal disorders for many years, as it has been shown to modulate visceral perception.21 Although published studies are limited, research regarding other functional esophageal disorders suggests that patients who commit to long-term behavioral therapy have had a significant improvement in symptoms.22

The goal of esophageal-directed behavioral therapy is to promote focused relaxation using deep breathing techniques, which can help patients manage esophageal hypervigilance, especially if symptoms continue despite neuromodulator therapy. Specifically, hypnotherapy has been shown to modulate functional chest pain through the visceral sensory pathway and also to suppress gastric acid secretion.21,23 A study of a 7-week hypnotherapy program reported significant benefits in heartburn relief and improved quality of life in patients with functional heartburn.24 The data support the use of behavioral therapies as first-line therapy or as adjunctive therapy for patients already taking a neuromodulator.

CASE FOLLOW-UP: IMPROVEMENT WITH TREATMENT

During a follow-up visit, the patient is given several printed resources, including the Rome Foundation article on functional heartburn.5 We again emphasize the benign nature of functional heartburn, noting the minimal risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, as she had no evidence of Barrett esophagus on endoscopy. And we discuss the natural course of functional heartburn, including the spontaneous resolution rate of about 40%.

For treatment, we present her the rationale for using neuromodulators and reassure her that these medications are for treatment of visceral hypersensitivity, not for anxiety or depression. After the discussion, the patient opts to start amitriptyline therapy at 10 mg every night at bedtime, increasing the dose by 10 mg every 2 weeks until symptoms improve, up to 75–100 mg every day.

After 3 months, the patient reports a 90% improvement in symptoms while on amitriptyline 30 mg every night. She is also able to taper her antisecretory medications once symptoms are controlled. We plan to continue amitriptyline at the current dose for 6 to 12 months, then discuss a slow taper to see if her symptoms spontaneously resolve.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101(8):1900–1920.

- Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2(8):656–664. pmid:15290657

- Hachem C, Shaheen NJ. Diagnosis and management of functional heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):53–61. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.376

- Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut 2009; 58(2):295–309. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.145581

- Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6):1368-1379. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012

- Kondo T, Miwa H. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional heartburn. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(7):571–578. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000885

- Farmer AD, Ruffle JK, Aziz Q. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional esophageal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(2):91–99. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000757

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut 2006; 55(10):1398–1402. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.087668

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):308–328. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.444

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27(2):160–174. doi:10.1111/nmo.12477

- Kichler AJ, Gabbard S. A man with progressive dysphagia. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84(6):443–449. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.16055

- Roman S, Gyawali CP, Savarino E, et al; GERD consensus group. Ambulatory reflux monitoring for diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: update of the Porto consensus and recommendations from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 29(10):1–15. doi:10.1111/nmo.13067

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):30–50. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.322

- Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(3):799–807. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010

- Park EY, Choi MG, Baeg M, et al. The value of early wireless esophageal pH monitoring in diagnosing functional heartburn in refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):2933–2939. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2728-4

- Khajanchee YS, Hong D, Hansen PD, Swanström LL. Outcomes of antireflux surgery in patients with normal preoperative 24-hour pH test results. Am J Surg 2004; 187(5):599–603. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.01.010

- Viazis N, Keyoglou A, Kanellopoulos AK, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of hypersensitive esophagus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11):1662–1667. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.179

- Limsrivilai J, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Pausawasdi N, Leelakusolvong S. Imipramine for treatment of esophageal hypersensitivity and functional heartburn: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):217–224. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.413

- Keefer L, Kahrilas PJ. Low-dose tricyclics for esophageal hypersensitivity: is it all placebo effect? Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):225–227. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.13

- Basu PP, Hempole H, Krishnaswamy N, Shah NJ, Aloysius, M. The effect of melatonin in functional heartburn: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Open J Gastroenterol 2014; 4(2):56–61. doi:10.4236/ojgas.2014.42010

- Watanabe S, Hattori T, Kanazawa M, Kano M, Fukudo S. Role of histaminergic neurons in hypnotic modulation of brain processing of visceral perception. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19(10):831–838. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00959.x

- Riehl ME, Kinsinger S, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Keefer L. Role of a health psychologist in the management of functional esophageal complaints. Dis Esophagus 2015; 28(5):428–436. doi:10.1111/dote.12219

- Klein KB, Spiegel D. Modulation of gastric acid secretion by hypnosis. Gastroenterology 1989; 96(6):1383–1387. pmid:2714570

- Riehl ME, Pandolfino JE, Palsson OS, Keefer L. Feasibility and acceptability of esophageal-directed hypnotherapy for functional heartburn. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29(5):490–496. doi:10.1111/dote.12353

A 44-year-old woman presents with an 8-year history of intermittent heartburn, and in the past year she has been experiencing her symptoms daily. She says the heartburn is constant and is worse immediately after eating spicy or acidic foods. She says she has had no dysphagia, weight loss, or vomiting. Her symptoms have persisted despite taking a histamine (H)2-receptor antagonist twice daily plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) before breakfast and dinner for more than 3 months.

She has undergone upper endoscopy 3 times in the past 8 years. Each time, the esophagus was normal with a regular Z-line and normal biopsy results from the proximal and distal esophagus.

The patient believes she has severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and asks if she is a candidate for fundoplication surgery.

HEARTBURN IS A SYMPTOM; GERD IS A CONDITION

A distinction should be made between heartburn—the symptom of persistent retrosternal burning and discomfort—and gastroesophageal reflux disease—the condition in which reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications.1 While many clinicians initially diagnose patients who have heartburn as having GERD, there are many other potential causes of their symptoms.

For patients with persistent heartburn, an empiric trial of a once-daily PPI is usually effective, but one-third of patients continue to have heartburn.2,3 The most common cause of this PPI-refractory heartburn is functional heartburn, a functional or hypersensitivity disorder of the esophagus.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY IS POORLY UNDERSTOOD

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Clinicians have several tests available for diagnosing these conditions.

Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is recommended for patients with heartburn that does not respond to a 3-month trial of a PPI.9 Endoscopy is also indicated in any patient who has any of the following “alarm symptoms” that could be due to malignancy or peptic ulcer:

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss or anemia

- Signs of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Anorexia

- New onset of dyspepsia in a patient over age 60.

During upper endoscopy, the esophagus is evaluated for reflux esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and other inflammatory disorders such as infectious esophagitis. But even if the esophageal mucosa appears normal, the proximal and distal esophagus should be biopsied to rule out an inflammatory disorder such as eosinophilic or lymphocytic esophagitis.

Esophageal manometry

If endoscopic and esophageal biopsy results are inconclusive, a workup for an esophageal motility disorder is the next step. Dysphagia is the most common symptom of these disorders, although the initial presenting symptom may be heartburn or regurgitation that persists despite PPI therapy.

Manometry is used to test for motility disorders such as achalasia and esophageal spasm.10 After applying a local anesthetic inside the nares, the clinician inserts a flexible catheter (about 4 mm in diameter) with 36 pressure sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals into the nares and passes it through the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter. The patient then swallows liquid, and the sensors relay the esophageal response, creating a topographic plot that shows esophageal peristalsis and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

Achalasia is identified by incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation combined with 100% failed peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. Esophageal spasms are identified by a shortened distal latency, which corresponds to premature contraction of the esophagus during peristalsis.11

Esophageal pH testing

Measuring esophageal pH levels is an important step to quantify gastroesophageal reflux and determine if symptoms occur during reflux events. According to the updated Porto GERD consensus group recommendations,12 a pH test is positive if the acid exposure time is greater than 6% of the testing period. Testing the pH differentiates between GERD (abnormal acid exposure), reflux hypersensitivity (normal acid exposure, strong correlation between symptoms and reflux events), and functional heartburn (normal acid exposure, negative correlation between reflux events and symptoms).5 For this test, a pH probe is placed in the esophagus transnasally or endoscopically. The probe records esophageal pH levels for 24 to 96 hours in an outpatient setting. Antisecretory therapy needs to be withheld for 7 to 10 days before the test.

Transnasal pH probe. For this approach, a thin catheter is inserted through the nares and advanced until the tip is 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. (The placement is guided by the results of esophageal manometry, which is done immediately before pH catheter placement.) The tube is secured with clear tape on the side of the patient’s face, and the end is connected to a portable recorder that compiles the data. The patient pushes a button on the recorder when experiencing heartburn symptoms. (A nurse instructs the patient on proper procedure.) After 24 hours, the patient either removes the catheter or has the clinic remove it. The pH and symptom data are downloaded and analyzed.

Transnasal pH testing can be combined with impedance measurement, which can detect nonacid reflux or weakly acid reflux. However, the clinical significance of this measurement is unclear, as multiple studies have found total acid exposure time to be a better predictor of response to therapy than weakly acid or nonacid reflux.12

Wireless pH probe. This method uses a disposable, catheter-free, capsule device to measure esophageal pH. The capsule, about the size of a gel capsule or pencil eraser, is attached to the patient’s esophageal lining, usually during upper endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels in the lower esophagus for 48 to 96 hours and transmits the data wirelessly to a receiver the patient wears. The patient pushes buttons on the receiver to record symptom-specific data when experiencing heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, or cough. The capsule detaches from the esophagus spontaneously, generally within 7 days, and is passed out of the body through a bowel movement.

Diagnosing functional heartburn

CASE CONTINUED: NORMAL RESULTS ON TESTING

Based on these results, her condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn, consistent with the Rome IV criteria.5

TREATMENT

Patient education is key

Patient education about the pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment options is the most important aspect of treating any functional gastrointestinal disorder. This includes the “brain-gut connection” and potential mechanisms of dysregulation. Patient education along with assessment of symptoms should be part of every visit, especially before discussing treatment options.

Patients whose condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn need reassurance that the condition is benign and, in particular, that the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is minimal in the absence of Barrett esophagus.13 Also important to point out is that the disorder may spontaneously resolve: resolution rates of up to 40% have been reported for other functional gastrointestinal disorders.14

Antisecretory medications may work for some

A PPI or H2-receptor antagonist is the most common first-line treatment for heartburn symptoms. Although most patients with functional heartburn experience no improvement in symptoms with an antisecretory agent, a small number report some relief, which suggests that acid-suppression therapy may have an indirect impact on pain modulation in the esophagus.15 In patients who report symptom relief with an antisecretory agent, we suggest continuing the medication tapered to the lowest effective dose, with repeated reassurance that the medication can be discontinued safely at any time.

Antireflux surgery should be avoided

Antireflux surgery should be avoided in patients with normal pH testing and no objective finding of reflux, as this is associated with worse subjective outcomes than in patients with abnormal pH test results.16

Neuromodulators

It is important to discuss with patients the concept of neuromodulation, including the fact that antidepressants are often used because of their effects on serotonin and norepinephrine, which decrease visceral hypersensitivity.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram has been shown to reduce esophageal hypersensitivity,17 and a tricyclic antidepressant has been shown to improve quality of life.18 These results have led experts to recommend a trial of a low dose of either type of medication.19 The dose of tricyclic antidepressant often needs to be increased sequentially every 2 to 4 weeks.

Interestingly, melatonin 6 mg at bedtime has also shown efficacy for functional heartburn, potentially due to its antinociceptive properties.20

Alternative and complementary therapies

Many esophageal centers use cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy as first-line treatment for functional esophageal disorders. Here again, it is important for the patient to understand the rationale of therapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders, given the stigma in the general population regarding psychotherapy.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been used for functional gastrointestinal disorders for many years, as it has been shown to modulate visceral perception.21 Although published studies are limited, research regarding other functional esophageal disorders suggests that patients who commit to long-term behavioral therapy have had a significant improvement in symptoms.22

The goal of esophageal-directed behavioral therapy is to promote focused relaxation using deep breathing techniques, which can help patients manage esophageal hypervigilance, especially if symptoms continue despite neuromodulator therapy. Specifically, hypnotherapy has been shown to modulate functional chest pain through the visceral sensory pathway and also to suppress gastric acid secretion.21,23 A study of a 7-week hypnotherapy program reported significant benefits in heartburn relief and improved quality of life in patients with functional heartburn.24 The data support the use of behavioral therapies as first-line therapy or as adjunctive therapy for patients already taking a neuromodulator.

CASE FOLLOW-UP: IMPROVEMENT WITH TREATMENT

During a follow-up visit, the patient is given several printed resources, including the Rome Foundation article on functional heartburn.5 We again emphasize the benign nature of functional heartburn, noting the minimal risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, as she had no evidence of Barrett esophagus on endoscopy. And we discuss the natural course of functional heartburn, including the spontaneous resolution rate of about 40%.

For treatment, we present her the rationale for using neuromodulators and reassure her that these medications are for treatment of visceral hypersensitivity, not for anxiety or depression. After the discussion, the patient opts to start amitriptyline therapy at 10 mg every night at bedtime, increasing the dose by 10 mg every 2 weeks until symptoms improve, up to 75–100 mg every day.

After 3 months, the patient reports a 90% improvement in symptoms while on amitriptyline 30 mg every night. She is also able to taper her antisecretory medications once symptoms are controlled. We plan to continue amitriptyline at the current dose for 6 to 12 months, then discuss a slow taper to see if her symptoms spontaneously resolve.

A 44-year-old woman presents with an 8-year history of intermittent heartburn, and in the past year she has been experiencing her symptoms daily. She says the heartburn is constant and is worse immediately after eating spicy or acidic foods. She says she has had no dysphagia, weight loss, or vomiting. Her symptoms have persisted despite taking a histamine (H)2-receptor antagonist twice daily plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) before breakfast and dinner for more than 3 months.

She has undergone upper endoscopy 3 times in the past 8 years. Each time, the esophagus was normal with a regular Z-line and normal biopsy results from the proximal and distal esophagus.

The patient believes she has severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and asks if she is a candidate for fundoplication surgery.

HEARTBURN IS A SYMPTOM; GERD IS A CONDITION

A distinction should be made between heartburn—the symptom of persistent retrosternal burning and discomfort—and gastroesophageal reflux disease—the condition in which reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications.1 While many clinicians initially diagnose patients who have heartburn as having GERD, there are many other potential causes of their symptoms.

For patients with persistent heartburn, an empiric trial of a once-daily PPI is usually effective, but one-third of patients continue to have heartburn.2,3 The most common cause of this PPI-refractory heartburn is functional heartburn, a functional or hypersensitivity disorder of the esophagus.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY IS POORLY UNDERSTOOD

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Clinicians have several tests available for diagnosing these conditions.

Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is recommended for patients with heartburn that does not respond to a 3-month trial of a PPI.9 Endoscopy is also indicated in any patient who has any of the following “alarm symptoms” that could be due to malignancy or peptic ulcer:

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss or anemia

- Signs of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Anorexia

- New onset of dyspepsia in a patient over age 60.

During upper endoscopy, the esophagus is evaluated for reflux esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and other inflammatory disorders such as infectious esophagitis. But even if the esophageal mucosa appears normal, the proximal and distal esophagus should be biopsied to rule out an inflammatory disorder such as eosinophilic or lymphocytic esophagitis.

Esophageal manometry

If endoscopic and esophageal biopsy results are inconclusive, a workup for an esophageal motility disorder is the next step. Dysphagia is the most common symptom of these disorders, although the initial presenting symptom may be heartburn or regurgitation that persists despite PPI therapy.

Manometry is used to test for motility disorders such as achalasia and esophageal spasm.10 After applying a local anesthetic inside the nares, the clinician inserts a flexible catheter (about 4 mm in diameter) with 36 pressure sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals into the nares and passes it through the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter. The patient then swallows liquid, and the sensors relay the esophageal response, creating a topographic plot that shows esophageal peristalsis and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

Achalasia is identified by incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation combined with 100% failed peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. Esophageal spasms are identified by a shortened distal latency, which corresponds to premature contraction of the esophagus during peristalsis.11

Esophageal pH testing

Measuring esophageal pH levels is an important step to quantify gastroesophageal reflux and determine if symptoms occur during reflux events. According to the updated Porto GERD consensus group recommendations,12 a pH test is positive if the acid exposure time is greater than 6% of the testing period. Testing the pH differentiates between GERD (abnormal acid exposure), reflux hypersensitivity (normal acid exposure, strong correlation between symptoms and reflux events), and functional heartburn (normal acid exposure, negative correlation between reflux events and symptoms).5 For this test, a pH probe is placed in the esophagus transnasally or endoscopically. The probe records esophageal pH levels for 24 to 96 hours in an outpatient setting. Antisecretory therapy needs to be withheld for 7 to 10 days before the test.

Transnasal pH probe. For this approach, a thin catheter is inserted through the nares and advanced until the tip is 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. (The placement is guided by the results of esophageal manometry, which is done immediately before pH catheter placement.) The tube is secured with clear tape on the side of the patient’s face, and the end is connected to a portable recorder that compiles the data. The patient pushes a button on the recorder when experiencing heartburn symptoms. (A nurse instructs the patient on proper procedure.) After 24 hours, the patient either removes the catheter or has the clinic remove it. The pH and symptom data are downloaded and analyzed.

Transnasal pH testing can be combined with impedance measurement, which can detect nonacid reflux or weakly acid reflux. However, the clinical significance of this measurement is unclear, as multiple studies have found total acid exposure time to be a better predictor of response to therapy than weakly acid or nonacid reflux.12

Wireless pH probe. This method uses a disposable, catheter-free, capsule device to measure esophageal pH. The capsule, about the size of a gel capsule or pencil eraser, is attached to the patient’s esophageal lining, usually during upper endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels in the lower esophagus for 48 to 96 hours and transmits the data wirelessly to a receiver the patient wears. The patient pushes buttons on the receiver to record symptom-specific data when experiencing heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, or cough. The capsule detaches from the esophagus spontaneously, generally within 7 days, and is passed out of the body through a bowel movement.

Diagnosing functional heartburn

CASE CONTINUED: NORMAL RESULTS ON TESTING

Based on these results, her condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn, consistent with the Rome IV criteria.5

TREATMENT

Patient education is key

Patient education about the pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment options is the most important aspect of treating any functional gastrointestinal disorder. This includes the “brain-gut connection” and potential mechanisms of dysregulation. Patient education along with assessment of symptoms should be part of every visit, especially before discussing treatment options.

Patients whose condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn need reassurance that the condition is benign and, in particular, that the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is minimal in the absence of Barrett esophagus.13 Also important to point out is that the disorder may spontaneously resolve: resolution rates of up to 40% have been reported for other functional gastrointestinal disorders.14

Antisecretory medications may work for some

A PPI or H2-receptor antagonist is the most common first-line treatment for heartburn symptoms. Although most patients with functional heartburn experience no improvement in symptoms with an antisecretory agent, a small number report some relief, which suggests that acid-suppression therapy may have an indirect impact on pain modulation in the esophagus.15 In patients who report symptom relief with an antisecretory agent, we suggest continuing the medication tapered to the lowest effective dose, with repeated reassurance that the medication can be discontinued safely at any time.

Antireflux surgery should be avoided

Antireflux surgery should be avoided in patients with normal pH testing and no objective finding of reflux, as this is associated with worse subjective outcomes than in patients with abnormal pH test results.16

Neuromodulators

It is important to discuss with patients the concept of neuromodulation, including the fact that antidepressants are often used because of their effects on serotonin and norepinephrine, which decrease visceral hypersensitivity.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram has been shown to reduce esophageal hypersensitivity,17 and a tricyclic antidepressant has been shown to improve quality of life.18 These results have led experts to recommend a trial of a low dose of either type of medication.19 The dose of tricyclic antidepressant often needs to be increased sequentially every 2 to 4 weeks.

Interestingly, melatonin 6 mg at bedtime has also shown efficacy for functional heartburn, potentially due to its antinociceptive properties.20

Alternative and complementary therapies

Many esophageal centers use cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy as first-line treatment for functional esophageal disorders. Here again, it is important for the patient to understand the rationale of therapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders, given the stigma in the general population regarding psychotherapy.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been used for functional gastrointestinal disorders for many years, as it has been shown to modulate visceral perception.21 Although published studies are limited, research regarding other functional esophageal disorders suggests that patients who commit to long-term behavioral therapy have had a significant improvement in symptoms.22

The goal of esophageal-directed behavioral therapy is to promote focused relaxation using deep breathing techniques, which can help patients manage esophageal hypervigilance, especially if symptoms continue despite neuromodulator therapy. Specifically, hypnotherapy has been shown to modulate functional chest pain through the visceral sensory pathway and also to suppress gastric acid secretion.21,23 A study of a 7-week hypnotherapy program reported significant benefits in heartburn relief and improved quality of life in patients with functional heartburn.24 The data support the use of behavioral therapies as first-line therapy or as adjunctive therapy for patients already taking a neuromodulator.

CASE FOLLOW-UP: IMPROVEMENT WITH TREATMENT

During a follow-up visit, the patient is given several printed resources, including the Rome Foundation article on functional heartburn.5 We again emphasize the benign nature of functional heartburn, noting the minimal risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, as she had no evidence of Barrett esophagus on endoscopy. And we discuss the natural course of functional heartburn, including the spontaneous resolution rate of about 40%.

For treatment, we present her the rationale for using neuromodulators and reassure her that these medications are for treatment of visceral hypersensitivity, not for anxiety or depression. After the discussion, the patient opts to start amitriptyline therapy at 10 mg every night at bedtime, increasing the dose by 10 mg every 2 weeks until symptoms improve, up to 75–100 mg every day.

After 3 months, the patient reports a 90% improvement in symptoms while on amitriptyline 30 mg every night. She is also able to taper her antisecretory medications once symptoms are controlled. We plan to continue amitriptyline at the current dose for 6 to 12 months, then discuss a slow taper to see if her symptoms spontaneously resolve.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101(8):1900–1920.

- Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2(8):656–664. pmid:15290657

- Hachem C, Shaheen NJ. Diagnosis and management of functional heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):53–61. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.376

- Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut 2009; 58(2):295–309. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.145581

- Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6):1368-1379. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012

- Kondo T, Miwa H. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional heartburn. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(7):571–578. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000885

- Farmer AD, Ruffle JK, Aziz Q. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional esophageal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(2):91–99. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000757

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut 2006; 55(10):1398–1402. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.087668

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):308–328. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.444

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27(2):160–174. doi:10.1111/nmo.12477

- Kichler AJ, Gabbard S. A man with progressive dysphagia. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84(6):443–449. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.16055

- Roman S, Gyawali CP, Savarino E, et al; GERD consensus group. Ambulatory reflux monitoring for diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: update of the Porto consensus and recommendations from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 29(10):1–15. doi:10.1111/nmo.13067

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):30–50. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.322

- Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(3):799–807. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010

- Park EY, Choi MG, Baeg M, et al. The value of early wireless esophageal pH monitoring in diagnosing functional heartburn in refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):2933–2939. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2728-4

- Khajanchee YS, Hong D, Hansen PD, Swanström LL. Outcomes of antireflux surgery in patients with normal preoperative 24-hour pH test results. Am J Surg 2004; 187(5):599–603. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.01.010

- Viazis N, Keyoglou A, Kanellopoulos AK, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of hypersensitive esophagus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11):1662–1667. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.179

- Limsrivilai J, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Pausawasdi N, Leelakusolvong S. Imipramine for treatment of esophageal hypersensitivity and functional heartburn: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):217–224. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.413

- Keefer L, Kahrilas PJ. Low-dose tricyclics for esophageal hypersensitivity: is it all placebo effect? Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):225–227. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.13

- Basu PP, Hempole H, Krishnaswamy N, Shah NJ, Aloysius, M. The effect of melatonin in functional heartburn: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Open J Gastroenterol 2014; 4(2):56–61. doi:10.4236/ojgas.2014.42010

- Watanabe S, Hattori T, Kanazawa M, Kano M, Fukudo S. Role of histaminergic neurons in hypnotic modulation of brain processing of visceral perception. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19(10):831–838. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00959.x

- Riehl ME, Kinsinger S, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Keefer L. Role of a health psychologist in the management of functional esophageal complaints. Dis Esophagus 2015; 28(5):428–436. doi:10.1111/dote.12219

- Klein KB, Spiegel D. Modulation of gastric acid secretion by hypnosis. Gastroenterology 1989; 96(6):1383–1387. pmid:2714570

- Riehl ME, Pandolfino JE, Palsson OS, Keefer L. Feasibility and acceptability of esophageal-directed hypnotherapy for functional heartburn. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29(5):490–496. doi:10.1111/dote.12353

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101(8):1900–1920.

- Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2(8):656–664. pmid:15290657

- Hachem C, Shaheen NJ. Diagnosis and management of functional heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):53–61. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.376

- Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut 2009; 58(2):295–309. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.145581

- Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6):1368-1379. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012

- Kondo T, Miwa H. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional heartburn. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(7):571–578. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000885

- Farmer AD, Ruffle JK, Aziz Q. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional esophageal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(2):91–99. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000757

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut 2006; 55(10):1398–1402. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.087668

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):308–328. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.444

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27(2):160–174. doi:10.1111/nmo.12477

- Kichler AJ, Gabbard S. A man with progressive dysphagia. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84(6):443–449. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.16055

- Roman S, Gyawali CP, Savarino E, et al; GERD consensus group. Ambulatory reflux monitoring for diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: update of the Porto consensus and recommendations from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 29(10):1–15. doi:10.1111/nmo.13067

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(1):30–50. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.322

- Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(3):799–807. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010

- Park EY, Choi MG, Baeg M, et al. The value of early wireless esophageal pH monitoring in diagnosing functional heartburn in refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):2933–2939. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2728-4

- Khajanchee YS, Hong D, Hansen PD, Swanström LL. Outcomes of antireflux surgery in patients with normal preoperative 24-hour pH test results. Am J Surg 2004; 187(5):599–603. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.01.010

- Viazis N, Keyoglou A, Kanellopoulos AK, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of hypersensitive esophagus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11):1662–1667. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.179

- Limsrivilai J, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Pausawasdi N, Leelakusolvong S. Imipramine for treatment of esophageal hypersensitivity and functional heartburn: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):217–224. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.413

- Keefer L, Kahrilas PJ. Low-dose tricyclics for esophageal hypersensitivity: is it all placebo effect? Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111(2):225–227. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.13

- Basu PP, Hempole H, Krishnaswamy N, Shah NJ, Aloysius, M. The effect of melatonin in functional heartburn: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Open J Gastroenterol 2014; 4(2):56–61. doi:10.4236/ojgas.2014.42010

- Watanabe S, Hattori T, Kanazawa M, Kano M, Fukudo S. Role of histaminergic neurons in hypnotic modulation of brain processing of visceral perception. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19(10):831–838. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00959.x

- Riehl ME, Kinsinger S, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Keefer L. Role of a health psychologist in the management of functional esophageal complaints. Dis Esophagus 2015; 28(5):428–436. doi:10.1111/dote.12219

- Klein KB, Spiegel D. Modulation of gastric acid secretion by hypnosis. Gastroenterology 1989; 96(6):1383–1387. pmid:2714570

- Riehl ME, Pandolfino JE, Palsson OS, Keefer L. Feasibility and acceptability of esophageal-directed hypnotherapy for functional heartburn. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29(5):490–496. doi:10.1111/dote.12353

KEY POINTS

- Functional heartburn accounts for more than half of all referrals for PPI-refractory GERD.

- Diagnostic criteria require at least 3 months of symptoms in the 6 months before presentation.

- Results of upper endoscopy with biopsy, esophageal manometry, and esophageal pH monitoring must be normal.

- Patient education is key, with reassurance that the risk of progression to malignancy is low in the absence of Barrett esophagus, and that the condition remits spontaneously in up to 40% of cases.

- Neuromodulators to reduce pain perception are the mainstay of treatment for functional gastrointestinal disorders such as functional heartburn. Cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy are also used as first-line treatment.

A man with progressive dysphagia

A 71-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of 9 months of progressive swallowing difficulties associated with epigastric and chest discomfort.

He was a previous smoker (17 pack-years), with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and cervical spinal stenosis requiring decompressive laminectomy with a postoperative course complicated by episodes of aspiration.

DYSPHAGIA: OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be caused by problems in the oropharynx or in the esophagus. Difficulty initiating a swallow can be thought of as oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas the intermittent sensation of food stuck in the neck or chest is considered esophageal dysphagia.

Focused questioning can help differentiate oropharyngeal symptoms from esophageal symptoms. For example, difficulty clearing secretions or passing the food bolus beyond the mouth or frequent coughing spells while eating is consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia and suggests a neurologic cause. Our patient, however, presented with a constellation of symptoms more suggestive of esophageal dysphagia.

When eliciting a history of esophageal symptoms, it is crucial to determine the progression of swallowing difficulty, as well as how it directly relates to eating solids or liquids, or both. Difficulty swallowing solid foods that has progressed over time to include liquids would raise concern for an obstruction such as a stricture, ring, or malignancy. On the other hand, abrupt onset of intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids would raise concern for a motility disorder of the esophagus. This patient presented with an abrupt onset of intermittent symptoms to both solids and liquids that was associated with substernal chest pain.

Once coronary disease was ruled out by cardiac biomarker testing, electrocardiography, and a pharmacologic stress test, our patient underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a normal esophageal mucosa without masses or obstruction and no evidence of peptic ulcer disease.

WHAT IS THE NEXT STEP?

When upper endoscopy is negative and cardiac causes and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been ruled out, an esophageal motility disorder should be considered.

1. After obstruction has been ruled out with upper endoscopy, which should be the next step in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia?

- A 24-hour pH recording

- Barium esophagography

- Modified barium swallow

- Computed tomography of the chest

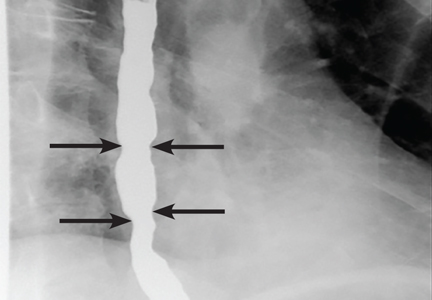

Barium esophagography is the optimal fluoroscopic study to evaluate the esophageal phase of the swallow. This study requires the patient to swallow a thick barium solution and a 13-mm barium pill under video analysis. It is useful early in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia because it can potentially reveal areas of esophageal luminal narrowing not detected endoscopically, as well as detail the rate of esophageal emptying.1

The modified barium swallow, which is performed with the assistance of a speech pathologist, is similar but only shows the oropharynx as far as the cervical esophagus. Therefore, it would be the best fluoroscopic test to assess patients with possible aspiration or oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas barium esophagography would be the test of choice in evaluating esophageal dysmotility or mechanical obstruction.

pH testing may be helpful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease but is less helpful in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Computed tomography of the chest may be useful to evaluate for extrinsic compression of the esophagus, but it is not the best next step in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Our patient underwent barium esophagography, which revealed tertiary contractions in the mid and distal esophagus with slight narrowing of the lower cervical esophagus (Figure 1). (Primary contractions are elicited when initiating a swallow that propels the food bolus through the esophagus, while secondary contractions follow in response to esophageal distention to move all remaining esophageal contents from the thoracic esophagus. Tertiary contractions are abnormal, nonpropulsive, spontaneous contractions of the esophageal body that are initiated without swallowing.2)

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Histologic study of biopsies of the mid and distal esophagus from our patient’s upper endoscopy revealed 5 eosinophils per high-power field.

2. Does this patient meet the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis?

- Yes

- No

No. Having eosinophils in the esophagus is not enough to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis, as eosinophils are also common in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined as a chronic immune-mediated esophageal disease with histologically eosinophil-predominant inflammation (with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field). The diagnosis is additionally based on symptoms and endoscopic appearance.3 When investigating possible eosinophilic esophagitis, it is recommended that 2 to 4 samples be obtained from at least 2 different locations in the esophagus (eg, proximal and distal), because the inflammatory changes can be patchy.

WHAT DOES THE PATIENT HAVE?

3. What is the likely cause of this patient’s dysphagia?

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Achalasia

- Esophageal spasm

- Extrinsic compression

- Esophageal malignancy

Eosinophilic esophagitis causes characteristic symptoms that include difficulty swallowing, chest pain that does not respond to antisecretory therapy, and regurgitation of undigested food. As we discussed above, this patient has only 5 eosinophils per high-power field and does not meet the histologic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Achalasia has a characteristic “bird’s beak” appearance on esophagography that results from distal tapering of the esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction,1 and this is not apparent on our patient’s study.

Review of this patient’s esophagogram also does not reveal any extrinsic compression, esophageal malignancy, or distal tapering suggesting achalasia. In light of the abrupt onset of symptoms related to both solids and liquids associated with atypical chest pain, the primary concern should be for esophageal spasm.

ONE MORE TEST

4. What study would you order next to better elucidate the cause of this patient’s esophageal disorder?

- High-resolution esophageal manometry

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography

- 24-hour pH and impedance testing

- Wireless motility capsule

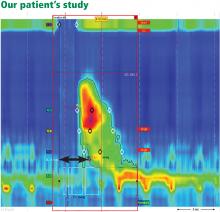

Esophageal manometry (Figure 2) is used to evaluate the function and coordination of the muscles of the esophagus, as in disorders of esophageal motility.

High-resolution manometry is the gold standard for evaluation of esophageal motility. It is appropriate in evaluating dysphagia or noncardiac chest pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction, ulceration, or inflammation.4,5

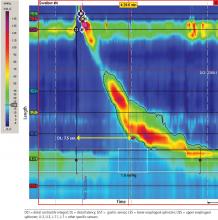

High-resolution manometry differs from conventional manometry in that the catheter has more sensors to measure intraluminal pressure (36 rather than the usual 7 to 12). The data are translated into pressure topography plots (Figure 3).6,7

Updated guidelines on how to interpret the findings of high-resolution manometry are known as the Chicago 3.0 criteria.4 According to this system, esophageal motility disorders are grouped on the basis of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then further subdivided based on the character of peristalsis.

EGD with endoscopic ultrasonography would not be appropriate at this time because there is little suspicion of an extraluminal mass that needs to be investigated.

A 24-hour pH and impedance study is helpful in determining the presence of esophageal acid exposure in patients presenting with gastroesophageal reflux disease. This patient does not have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation; therefore, this investigation would not be of value.

A wireless motility capsule would help in investigating gastric and small-bowel motility and may be useful in the future for this patient, but at this point it would provide little additional utility.

ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

Our patient underwent high-resolution esophageal manometry. The results (Figure 4) revealed a normal resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and complete relaxation in all swallows. The body of the esophagus demonstrated premature contractions in 90% of swallows. Overall, these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm.

TREATMENTS FOR ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

In addition to incorporating data obtained from endoscopy, esophagography, and manometry, it is crucial to identify the patient’s predominant symptom when planning treatment. For example, is the prevailing symptom dysphagia or chest pain? Additional consideration must be given to medical, surgical, and psychiatric comorbidities.

5. Which of the following is appropriate medical therapy for esophageal spasm?

- Calcium channel blockers

- Nitrates

- Hydralazine

- Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors

- All of the above

All of these have been used to treat distal esophageal spasm as well as other hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders.8–20

Calcium channel blockers have proven to be effective in randomized controlled trials. Diltiazem has been shown to be beneficial at doses ranging from 60 to 90 mg, as has nifedipine 10 to 20 mg 3 times daily. Although different drugs of this class tend to relax the lower esophageal sphincter to different degrees, when choosing among them in patients with hypercontractile disorders there is little concern for potentially precipitating reflux.8–13

Nitrates, hydralazine, and PDE5 inhibitors have been effective in uncontrolled studies but have not been studied in randomized trials.14–17

Other treatments. Patients may also benefit from neuromodulators such as trazodone and imipramine for chest pain and optimization of antisecretory therapy if they have concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease.18–20

Patients who have documented esophageal hypercontractility along with reflux disease confirmed by an abnormal pH study show significant improvement in their chest pain symptoms with high doses of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). As our patient presented with chest pain and dysphagia, a dedicated pH study was not needed, and we could progress straight to manometry and a trial of a PPI.

Our patient was started on a PPI and nifedipine but developed a pruritic rash. As rash does not preclude using another medication in the same class, his treatment was changed to diltiazem 30 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and his dysphagia improved. However, he continued to experience intermittent chest pain with swallowing. After discussion of neuromodulator therapy, he declined additional pharmacologic therapy.

A NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT?

6. Which of the following would you offer this patient as a nonpharmacologic alternative for his esophageal pain?

- St. John’s wort

- Ginkgo biloba

- Ginseng

- Peppermint extract

- Eucalyptus oil

In a small, open-label study in patients with esophageal spasm, the use of 5 drops of commercially available 11% peppermint extract in 10 mL of water significantly decreased simultaneous contractions and resolved chest pain.21 Esophageal manometry was performed 10 minutes after the peppermint solution was consumed, and the results showed improvement in esophageal spasm. While the authors of this study did not make any formal recommendations, the findings suggest that peppermint extract should be given 10 minutes before meals.

There is no evidence for or against the use of the other nonpharmacologic treatments mentioned here.

PAIN RELIEF

7. If a pharmacologic approach were chosen, which would be the best option for pain relief in this patient?

- Oxycodone 5 mg every 8 hours

- Acetaminophen 650 mg every 8 hours

- Ibuprofen 400 mg every evening at bedtime

- Trazodone 100 mg every evening at bedtime

- Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime

- Aripiprazole 5 mg by mouth every day

Trazodone would be the most appropriate of these options. Doses of 100 mg to 150 mg every evening at bedtime have been shown to significantly improve global assessment scores of pain at 6 weeks.18

Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime would be another option and also has been shown to reduce chest pain.19

Even though these were the doses that were investigated, in clinical practice it is common to start at lower doses (trazodone 50 mg or imipramine 10 mg) and to then titrate every 4 weeks based on the patient’s response.

Opiates (eg, oxycodone) should be avoided, as they can cause esophageal motility disorders such as spasm or achalasia.22

Acetaminophen and aripiprazole have not been studied exclusively for their effect on chest pain related to esophageal spasm.

RECURRENT SYMPTOMS

The patient’s dysphagia initially decreased while he was taking diltiazem 30 mg 3 times a day, but it recurred after 6 months. The dosage was increased to 60 mg 3 times a day over the course of the next year, with minimal response. (The maximum dose is 90 mg 4 times a day, but because of side effects of lightheadedness and dizziness, out patient could not tolerate more than 60 mg 3 times a day).

ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

8. What endoscopic therapies are appropriate for patients with esophageal spasm that does not respond to medication?

- Bougie dilation

- Balloon dilation

- Onabotulinum toxin injection

- Expandable mesh stent placement

- Mucosal sclerotherapy

Onabotulinum toxin injections have been shown to improve dysphagia when given in a linear pattern.23

Endoscopic dilation has not been shown to be beneficial in this setting, as a study found no difference in efficacy between therapeutic (54-French) and sham (24-French) bougie dilation.24

Our patient received 100 units of onabotulinum toxin (10 units every centimeter in the distal 10 cm of the esophagus). Afterward, he experienced resolution of dysphagia, with only mild intermittent chest pain, which was controlled by taking peppermint extract as needed. The symptoms returned approximately 1 year later but responded to repeat endoscopy with onabotulinum toxin injections.23,25

Peroral endoscopic myotomy

Another relatively new endoscopic treatment for esophageal motility disorders is peroral endoscopic myotomy (Figure 5). During this procedure a tiny incision is made in the esophageal mucosa, permitting the endoscope to tunnel within the lining. The smooth muscle of the distal esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter is then cut, thereby freeing either the spastic muscle (in distal esophageal spasm) or the hyperactive lower esophageal sphincter (in achalasia).26,27

In an open trial, after undergoing peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal spasm and hypercontractile esophagus, 89% of patients had complete relief of dysphagia, and 92% had palliation of chest pain.28 Of note, the rate of relief of dysphagia was higher for patients with achalasia (98%) than for nonachalasia patients (71%).

- Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:1238–1249;

- Hellemans J, Vantrappen G. Physiology. In: Vantrappen G, Hellemans J, eds. Diseases of the esophagus. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg; 1974:40–102.

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:679–692.

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27:160–174.

- Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ; American Gastroenterological Association. AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology 2005; 128:209–224.

- Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Zhang Q, Jarosz A, Shah N, Kahrilas PJ. Quantifying esophageal peristalsis with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006; 290:G988–G997.

- Kahrilas PJ, Sifrim D. High-resolution manometry and impedance-pH/manometry: valuable tools in clinical and investigational esophagology. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:756–769.

- Cattau EL Jr, Castell DO, Johnson DA, et al. Diltiazem therapy for symptoms associated with nutcracker esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86:272–276.

- Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology 1987; 93:21–28.

- Drenth JP, Bos LP, Engels LG. Efficacy of diltiazem in the treatment of diffuse oesophageal spasm. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1990; 4:411–416.

- Thomas E, Witt P, Willis M, Morse J. Nifedipine therapy for diffuse esophageal spasm. South Med J 1986; 79:847–849.

- Davies HA, Lewis MJ, Rhodes J, Henderson AH. Trial of nifedipine for prevention of oesophageal spasm. Digestion 1987; 36:81–83.

- Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology 1987; 93:21–28.

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Gasbarrini G. Transdermal slow-release long-acting isosorbide dinitrate for ‘nutcracker’ oesophagus: an open study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12:1061–1062.

- Mellow MH. Effect of isosorbide and hydralazine in painful primary esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1982; 83:364–370.

- Fox M, Sweis R, Wong T, Anggiansah A. Sildenafil relieves symptoms and normalizes motility in patients with oesophageal spasm: a report of two cases. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19:798–803.

- Orlando RC, Bozymski EM. Clinical and manometric effects of nitroglycerin in diffuse esophageal spasm. N Engl J Med 1973; 289:23–25.

- Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Eckert TC, Ferney DM, Griffith LS. Low-dose trazodone for symptomatic patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1987; 92:1027–1036.

- Cannon RO 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1411–1417.

- Achem SR, Kolts BE, Wears R, Burton L, Richter JE. Chest pain associated with nutcracker esophagus: a preliminary study of the role of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:187–192.

- Pimentel M, Bonorris GG, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Peppermint oil improves the manometric findings in diffuse esophageal spasm. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33:27–31.

- Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:601–606.

- Storr M, Allescher HD, Rösch T, Born P, Weigert N, Classen M. Treatment of symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm by endoscopic injections of botulinum toxin: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54:754–759.

- Winters C, Artnak EJ, Benjamin SB, Castell DO. Esophageal bougienage in symptomatic patients with the nutcracker esophagus. A primary esophageal motility disorder. JAMA 1984; 252:363–366.

- Vanuytsel T, Bisschops R, Farré R, et al. Botulinum toxin reduces dysphagia in patients with nonachalasia primary esophageal motility disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11:1115–1121.e2.

- Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Onimaru M, et al. International multicenter experience with peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of spastic esophageal disorders refractory to medical therapy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:1170–1177.

- Leconte M, Douard R, Gaudric M, Dumontier I, Chaussade S, Dousset B. Functional results after extended myotomy for diffuse oesophageal spasm. Br J Surg 2007; 94:1113–1118.

- Sharata AM, Dunst CM, Pescarus R, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal primary motility disorders: analysis of 100 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19:161–170.

A 71-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of 9 months of progressive swallowing difficulties associated with epigastric and chest discomfort.

He was a previous smoker (17 pack-years), with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and cervical spinal stenosis requiring decompressive laminectomy with a postoperative course complicated by episodes of aspiration.

DYSPHAGIA: OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be caused by problems in the oropharynx or in the esophagus. Difficulty initiating a swallow can be thought of as oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas the intermittent sensation of food stuck in the neck or chest is considered esophageal dysphagia.

Focused questioning can help differentiate oropharyngeal symptoms from esophageal symptoms. For example, difficulty clearing secretions or passing the food bolus beyond the mouth or frequent coughing spells while eating is consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia and suggests a neurologic cause. Our patient, however, presented with a constellation of symptoms more suggestive of esophageal dysphagia.

When eliciting a history of esophageal symptoms, it is crucial to determine the progression of swallowing difficulty, as well as how it directly relates to eating solids or liquids, or both. Difficulty swallowing solid foods that has progressed over time to include liquids would raise concern for an obstruction such as a stricture, ring, or malignancy. On the other hand, abrupt onset of intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids would raise concern for a motility disorder of the esophagus. This patient presented with an abrupt onset of intermittent symptoms to both solids and liquids that was associated with substernal chest pain.

Once coronary disease was ruled out by cardiac biomarker testing, electrocardiography, and a pharmacologic stress test, our patient underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a normal esophageal mucosa without masses or obstruction and no evidence of peptic ulcer disease.

WHAT IS THE NEXT STEP?

When upper endoscopy is negative and cardiac causes and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been ruled out, an esophageal motility disorder should be considered.

1. After obstruction has been ruled out with upper endoscopy, which should be the next step in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia?

- A 24-hour pH recording

- Barium esophagography

- Modified barium swallow

- Computed tomography of the chest

Barium esophagography is the optimal fluoroscopic study to evaluate the esophageal phase of the swallow. This study requires the patient to swallow a thick barium solution and a 13-mm barium pill under video analysis. It is useful early in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia because it can potentially reveal areas of esophageal luminal narrowing not detected endoscopically, as well as detail the rate of esophageal emptying.1

The modified barium swallow, which is performed with the assistance of a speech pathologist, is similar but only shows the oropharynx as far as the cervical esophagus. Therefore, it would be the best fluoroscopic test to assess patients with possible aspiration or oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas barium esophagography would be the test of choice in evaluating esophageal dysmotility or mechanical obstruction.

pH testing may be helpful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease but is less helpful in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Computed tomography of the chest may be useful to evaluate for extrinsic compression of the esophagus, but it is not the best next step in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Our patient underwent barium esophagography, which revealed tertiary contractions in the mid and distal esophagus with slight narrowing of the lower cervical esophagus (Figure 1). (Primary contractions are elicited when initiating a swallow that propels the food bolus through the esophagus, while secondary contractions follow in response to esophageal distention to move all remaining esophageal contents from the thoracic esophagus. Tertiary contractions are abnormal, nonpropulsive, spontaneous contractions of the esophageal body that are initiated without swallowing.2)

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Histologic study of biopsies of the mid and distal esophagus from our patient’s upper endoscopy revealed 5 eosinophils per high-power field.

2. Does this patient meet the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis?

- Yes

- No

No. Having eosinophils in the esophagus is not enough to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis, as eosinophils are also common in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined as a chronic immune-mediated esophageal disease with histologically eosinophil-predominant inflammation (with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field). The diagnosis is additionally based on symptoms and endoscopic appearance.3 When investigating possible eosinophilic esophagitis, it is recommended that 2 to 4 samples be obtained from at least 2 different locations in the esophagus (eg, proximal and distal), because the inflammatory changes can be patchy.

WHAT DOES THE PATIENT HAVE?

3. What is the likely cause of this patient’s dysphagia?

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Achalasia

- Esophageal spasm

- Extrinsic compression

- Esophageal malignancy

Eosinophilic esophagitis causes characteristic symptoms that include difficulty swallowing, chest pain that does not respond to antisecretory therapy, and regurgitation of undigested food. As we discussed above, this patient has only 5 eosinophils per high-power field and does not meet the histologic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Achalasia has a characteristic “bird’s beak” appearance on esophagography that results from distal tapering of the esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction,1 and this is not apparent on our patient’s study.

Review of this patient’s esophagogram also does not reveal any extrinsic compression, esophageal malignancy, or distal tapering suggesting achalasia. In light of the abrupt onset of symptoms related to both solids and liquids associated with atypical chest pain, the primary concern should be for esophageal spasm.

ONE MORE TEST

4. What study would you order next to better elucidate the cause of this patient’s esophageal disorder?

- High-resolution esophageal manometry

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography

- 24-hour pH and impedance testing

- Wireless motility capsule

Esophageal manometry (Figure 2) is used to evaluate the function and coordination of the muscles of the esophagus, as in disorders of esophageal motility.

High-resolution manometry is the gold standard for evaluation of esophageal motility. It is appropriate in evaluating dysphagia or noncardiac chest pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction, ulceration, or inflammation.4,5

High-resolution manometry differs from conventional manometry in that the catheter has more sensors to measure intraluminal pressure (36 rather than the usual 7 to 12). The data are translated into pressure topography plots (Figure 3).6,7

Updated guidelines on how to interpret the findings of high-resolution manometry are known as the Chicago 3.0 criteria.4 According to this system, esophageal motility disorders are grouped on the basis of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then further subdivided based on the character of peristalsis.

EGD with endoscopic ultrasonography would not be appropriate at this time because there is little suspicion of an extraluminal mass that needs to be investigated.