User login

Isotretinoin-Induced Skin Fragility in an Aerialist

Isotretinoin was introduced more than 3 decades ago and marked a major advancement in the treatment of severe refractory cystic acne. The most common adverse effects linked to isotretinoin usage are mucocutaneous in nature, manifesting as xerosis and cheilitis.1 Skin fragility and poor wound healing also have been reported.2-6 Current recommendations for avoiding these adverse effects include refraining from waxing, laser procedures, and other elective cutaneous procedures for at least 6 months.7 We present a case of isotretinoin-induced cutaneous fragility resulting in blistering and erosions on the palms of a competitive aerial trapeze artist.

Case Report

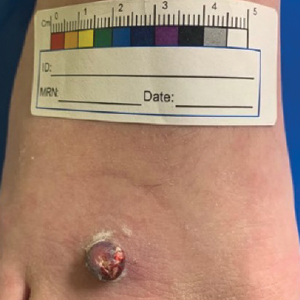

A 25-year-old woman presented for follow-up during week 12 of isotretinoin therapy (40 mg twice daily) prescribed for acne. She reported peeling of the skin on the palms following intense aerial acrobatic workouts. She had been a performing aerialist for many years and had never sustained a similar injury. The wounds were painful and led to decreased activity. She had no notable medical history. Physical examination of the palms revealed erosions in a distribution that corresponded to horizontal bar contact and friction (Figure). The patient was advised on proper wound care, application of emollients, and minimizing friction. She completed the course of isotretinoin and has continued aerialist activity without recurrence of skin fragility.

Comment

Skin fragility is a well-known adverse effect of isotretinoin therapy.8 Pavlis and Lieblich9 reported skin fragility in a young wrestler who experienced similar skin erosions due to isotretinoin therapy. The proposed mechanism of isotretinoin-induced skin fragility is multifactorial. It involves an apoptotic effect on sebocytes,5 which results in reduced stratum corneum hydration and an associated increase in transepidermal water loss.6,10,11 Retinoids also are known to cause thinning of the skin, likely due to the disadhesion of both the epidermis and the stratum corneum, which was demonstrated by the easy removal of cornified cells through tape stripping in hairless mice treated with isotretinoin.12 In further investigations, human patients and hairless mice treated with isotretinoin readily developed friction blisters through pencil eraser abrasion.13 Examination of the friction blisters using light and electron microscopy revealed fraying or loss of the stratum corneum and viable epidermis as well as loss of desmosomes and tonofilaments. Additionally, intracellular and intercellular deposits of an unidentified amorphous material were noted.13

Overall, the origin of skin fragility induced by isotretinoin is supported by its effect on sebocytes, increased transepidermal water loss, and profound disruption of the integrity of the epidermis, resulting in an elevated risk for inadvertent skin damage. Patients were encouraged to avoid cosmetic procedures in prior case reports,14-16 and because our case demonstrates the risk for cutaneous injury in athletes due to isotretinoin-induced skin fragility, we propose an extension of these warnings to encompass athletes receiving isotretinoin treatment. Offering early guidance on wound prevention is of paramount importance in maintaining athletic performance and minimizing painful injuries.

- Rajput I, Anjankar VP. Side effects of treating acne vulgaris with isotretinoin: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024;16:E55946. doi:10.7759/cureus.55946

- Hatami P, Balighi K, Asl HN, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: clinical implications and practical points. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:2146-2149. doi:10.1111/jocd.15874

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Alavi A. A systematic review on oral isotretinoin therapy and clinically observable wound healing in acne patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:325-333. doi:10.1177/1203475417701419

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169. doi:10.4161/derm.1.3.9364

- Zouboulis CC. Isotretinoin revisited: pluripotent effects on human sebaceous gland cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2154-2156. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700418

- Kmiec´ ML, Pajor A, Broniarczyk-Dyła G. Evaluation of biophysical skin parameters and assessment of hair growth in patients with acne treated with isotretinoin. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:343-349. doi:10.5114/pdia.2013.39432

- Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, et al. ASDS Guidelines Task Force: Consensus recommendations regarding the safety of lasers, dermabrasion, chemical peels, energy devices, and skin surgery during and after isotretinoin use. Dermatolog Surg. 2017;43:1249-1262. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001166

- Aksoy H, Aksoy B, Calikoglu E. Systemic retinoids and scar dehiscence. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:68. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_148_18

- Pavlis MB, Lieblich L. Isotretinoin-induced skin fragility in a teenaged athlete: a case report. Cutis. 2013;92:33-34.

- Herane MI, Fuenzalida H, Zegpi E, et al. Specific gel-cream as adjuvant to oral isotretinoin improved hydration and prevented TEWL increase—a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:181-185. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00455.x

- Park KY, Ko EJ, Kim IS, et al. The effect of evening primrose oil for the prevention of xerotic cheilitis in acne patients being treated with isotretinoin: a pilot study. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:706-712. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.706

- Elias PM, Fritsch PO, Lampe M, et al. Retinoid effects on epidermal structure, differentiation, and permeability. Lab Invest. 1981;44:531-540.

- Williams ML, Elias PM. Nature of skin fragility in patients receiving retinoids for systemic effect. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:611-619.

- Rubenstein R, Roenigk HH, Stegman SJ, et al. Atypical keloids after dermabrasion of patients taking isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:280-285. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70167-9

- Zachariae H. Delayed wound healing and keloid formation following argon laser treatment or dermabrasion during isotretinoin treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:703-706. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02574.x

- Katz BE, Mac Farlane DF. Atypical facial scarring after isotretinoin therapy in a patient with previous dermabrasion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:852-853. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70096-6

Isotretinoin was introduced more than 3 decades ago and marked a major advancement in the treatment of severe refractory cystic acne. The most common adverse effects linked to isotretinoin usage are mucocutaneous in nature, manifesting as xerosis and cheilitis.1 Skin fragility and poor wound healing also have been reported.2-6 Current recommendations for avoiding these adverse effects include refraining from waxing, laser procedures, and other elective cutaneous procedures for at least 6 months.7 We present a case of isotretinoin-induced cutaneous fragility resulting in blistering and erosions on the palms of a competitive aerial trapeze artist.

Case Report

A 25-year-old woman presented for follow-up during week 12 of isotretinoin therapy (40 mg twice daily) prescribed for acne. She reported peeling of the skin on the palms following intense aerial acrobatic workouts. She had been a performing aerialist for many years and had never sustained a similar injury. The wounds were painful and led to decreased activity. She had no notable medical history. Physical examination of the palms revealed erosions in a distribution that corresponded to horizontal bar contact and friction (Figure). The patient was advised on proper wound care, application of emollients, and minimizing friction. She completed the course of isotretinoin and has continued aerialist activity without recurrence of skin fragility.

Comment

Skin fragility is a well-known adverse effect of isotretinoin therapy.8 Pavlis and Lieblich9 reported skin fragility in a young wrestler who experienced similar skin erosions due to isotretinoin therapy. The proposed mechanism of isotretinoin-induced skin fragility is multifactorial. It involves an apoptotic effect on sebocytes,5 which results in reduced stratum corneum hydration and an associated increase in transepidermal water loss.6,10,11 Retinoids also are known to cause thinning of the skin, likely due to the disadhesion of both the epidermis and the stratum corneum, which was demonstrated by the easy removal of cornified cells through tape stripping in hairless mice treated with isotretinoin.12 In further investigations, human patients and hairless mice treated with isotretinoin readily developed friction blisters through pencil eraser abrasion.13 Examination of the friction blisters using light and electron microscopy revealed fraying or loss of the stratum corneum and viable epidermis as well as loss of desmosomes and tonofilaments. Additionally, intracellular and intercellular deposits of an unidentified amorphous material were noted.13

Overall, the origin of skin fragility induced by isotretinoin is supported by its effect on sebocytes, increased transepidermal water loss, and profound disruption of the integrity of the epidermis, resulting in an elevated risk for inadvertent skin damage. Patients were encouraged to avoid cosmetic procedures in prior case reports,14-16 and because our case demonstrates the risk for cutaneous injury in athletes due to isotretinoin-induced skin fragility, we propose an extension of these warnings to encompass athletes receiving isotretinoin treatment. Offering early guidance on wound prevention is of paramount importance in maintaining athletic performance and minimizing painful injuries.

Isotretinoin was introduced more than 3 decades ago and marked a major advancement in the treatment of severe refractory cystic acne. The most common adverse effects linked to isotretinoin usage are mucocutaneous in nature, manifesting as xerosis and cheilitis.1 Skin fragility and poor wound healing also have been reported.2-6 Current recommendations for avoiding these adverse effects include refraining from waxing, laser procedures, and other elective cutaneous procedures for at least 6 months.7 We present a case of isotretinoin-induced cutaneous fragility resulting in blistering and erosions on the palms of a competitive aerial trapeze artist.

Case Report

A 25-year-old woman presented for follow-up during week 12 of isotretinoin therapy (40 mg twice daily) prescribed for acne. She reported peeling of the skin on the palms following intense aerial acrobatic workouts. She had been a performing aerialist for many years and had never sustained a similar injury. The wounds were painful and led to decreased activity. She had no notable medical history. Physical examination of the palms revealed erosions in a distribution that corresponded to horizontal bar contact and friction (Figure). The patient was advised on proper wound care, application of emollients, and minimizing friction. She completed the course of isotretinoin and has continued aerialist activity without recurrence of skin fragility.

Comment

Skin fragility is a well-known adverse effect of isotretinoin therapy.8 Pavlis and Lieblich9 reported skin fragility in a young wrestler who experienced similar skin erosions due to isotretinoin therapy. The proposed mechanism of isotretinoin-induced skin fragility is multifactorial. It involves an apoptotic effect on sebocytes,5 which results in reduced stratum corneum hydration and an associated increase in transepidermal water loss.6,10,11 Retinoids also are known to cause thinning of the skin, likely due to the disadhesion of both the epidermis and the stratum corneum, which was demonstrated by the easy removal of cornified cells through tape stripping in hairless mice treated with isotretinoin.12 In further investigations, human patients and hairless mice treated with isotretinoin readily developed friction blisters through pencil eraser abrasion.13 Examination of the friction blisters using light and electron microscopy revealed fraying or loss of the stratum corneum and viable epidermis as well as loss of desmosomes and tonofilaments. Additionally, intracellular and intercellular deposits of an unidentified amorphous material were noted.13

Overall, the origin of skin fragility induced by isotretinoin is supported by its effect on sebocytes, increased transepidermal water loss, and profound disruption of the integrity of the epidermis, resulting in an elevated risk for inadvertent skin damage. Patients were encouraged to avoid cosmetic procedures in prior case reports,14-16 and because our case demonstrates the risk for cutaneous injury in athletes due to isotretinoin-induced skin fragility, we propose an extension of these warnings to encompass athletes receiving isotretinoin treatment. Offering early guidance on wound prevention is of paramount importance in maintaining athletic performance and minimizing painful injuries.

- Rajput I, Anjankar VP. Side effects of treating acne vulgaris with isotretinoin: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024;16:E55946. doi:10.7759/cureus.55946

- Hatami P, Balighi K, Asl HN, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: clinical implications and practical points. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:2146-2149. doi:10.1111/jocd.15874

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Alavi A. A systematic review on oral isotretinoin therapy and clinically observable wound healing in acne patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:325-333. doi:10.1177/1203475417701419

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169. doi:10.4161/derm.1.3.9364

- Zouboulis CC. Isotretinoin revisited: pluripotent effects on human sebaceous gland cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2154-2156. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700418

- Kmiec´ ML, Pajor A, Broniarczyk-Dyła G. Evaluation of biophysical skin parameters and assessment of hair growth in patients with acne treated with isotretinoin. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:343-349. doi:10.5114/pdia.2013.39432

- Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, et al. ASDS Guidelines Task Force: Consensus recommendations regarding the safety of lasers, dermabrasion, chemical peels, energy devices, and skin surgery during and after isotretinoin use. Dermatolog Surg. 2017;43:1249-1262. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001166

- Aksoy H, Aksoy B, Calikoglu E. Systemic retinoids and scar dehiscence. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:68. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_148_18

- Pavlis MB, Lieblich L. Isotretinoin-induced skin fragility in a teenaged athlete: a case report. Cutis. 2013;92:33-34.

- Herane MI, Fuenzalida H, Zegpi E, et al. Specific gel-cream as adjuvant to oral isotretinoin improved hydration and prevented TEWL increase—a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:181-185. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00455.x

- Park KY, Ko EJ, Kim IS, et al. The effect of evening primrose oil for the prevention of xerotic cheilitis in acne patients being treated with isotretinoin: a pilot study. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:706-712. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.706

- Elias PM, Fritsch PO, Lampe M, et al. Retinoid effects on epidermal structure, differentiation, and permeability. Lab Invest. 1981;44:531-540.

- Williams ML, Elias PM. Nature of skin fragility in patients receiving retinoids for systemic effect. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:611-619.

- Rubenstein R, Roenigk HH, Stegman SJ, et al. Atypical keloids after dermabrasion of patients taking isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:280-285. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70167-9

- Zachariae H. Delayed wound healing and keloid formation following argon laser treatment or dermabrasion during isotretinoin treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:703-706. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02574.x

- Katz BE, Mac Farlane DF. Atypical facial scarring after isotretinoin therapy in a patient with previous dermabrasion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:852-853. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70096-6

- Rajput I, Anjankar VP. Side effects of treating acne vulgaris with isotretinoin: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024;16:E55946. doi:10.7759/cureus.55946

- Hatami P, Balighi K, Asl HN, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: clinical implications and practical points. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:2146-2149. doi:10.1111/jocd.15874

- McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Alavi A. A systematic review on oral isotretinoin therapy and clinically observable wound healing in acne patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:325-333. doi:10.1177/1203475417701419

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169. doi:10.4161/derm.1.3.9364

- Zouboulis CC. Isotretinoin revisited: pluripotent effects on human sebaceous gland cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2154-2156. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700418

- Kmiec´ ML, Pajor A, Broniarczyk-Dyła G. Evaluation of biophysical skin parameters and assessment of hair growth in patients with acne treated with isotretinoin. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:343-349. doi:10.5114/pdia.2013.39432

- Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, et al. ASDS Guidelines Task Force: Consensus recommendations regarding the safety of lasers, dermabrasion, chemical peels, energy devices, and skin surgery during and after isotretinoin use. Dermatolog Surg. 2017;43:1249-1262. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001166

- Aksoy H, Aksoy B, Calikoglu E. Systemic retinoids and scar dehiscence. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:68. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_148_18

- Pavlis MB, Lieblich L. Isotretinoin-induced skin fragility in a teenaged athlete: a case report. Cutis. 2013;92:33-34.

- Herane MI, Fuenzalida H, Zegpi E, et al. Specific gel-cream as adjuvant to oral isotretinoin improved hydration and prevented TEWL increase—a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:181-185. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00455.x

- Park KY, Ko EJ, Kim IS, et al. The effect of evening primrose oil for the prevention of xerotic cheilitis in acne patients being treated with isotretinoin: a pilot study. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:706-712. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.706

- Elias PM, Fritsch PO, Lampe M, et al. Retinoid effects on epidermal structure, differentiation, and permeability. Lab Invest. 1981;44:531-540.

- Williams ML, Elias PM. Nature of skin fragility in patients receiving retinoids for systemic effect. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:611-619.

- Rubenstein R, Roenigk HH, Stegman SJ, et al. Atypical keloids after dermabrasion of patients taking isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:280-285. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70167-9

- Zachariae H. Delayed wound healing and keloid formation following argon laser treatment or dermabrasion during isotretinoin treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:703-706. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02574.x

- Katz BE, Mac Farlane DF. Atypical facial scarring after isotretinoin therapy in a patient with previous dermabrasion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:852-853. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70096-6

Practice Points

- Isotretinoin is used to treat severe nodulocystic acne but can cause adverse effects such as skin fragility, xerosis, and poor wound healing.

- Dermatologists should inform athletes of heightened skin vulnerability while undergoing isotretinoin treatment.

- Isotretinoin-induced skin fragility involves the effects of isotretinoin on sebocytes, transepidermal water loss, and disruption of the integrity of the epidermis.

Erythematous Pedunculated Plaque on the Dorsal Aspect of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

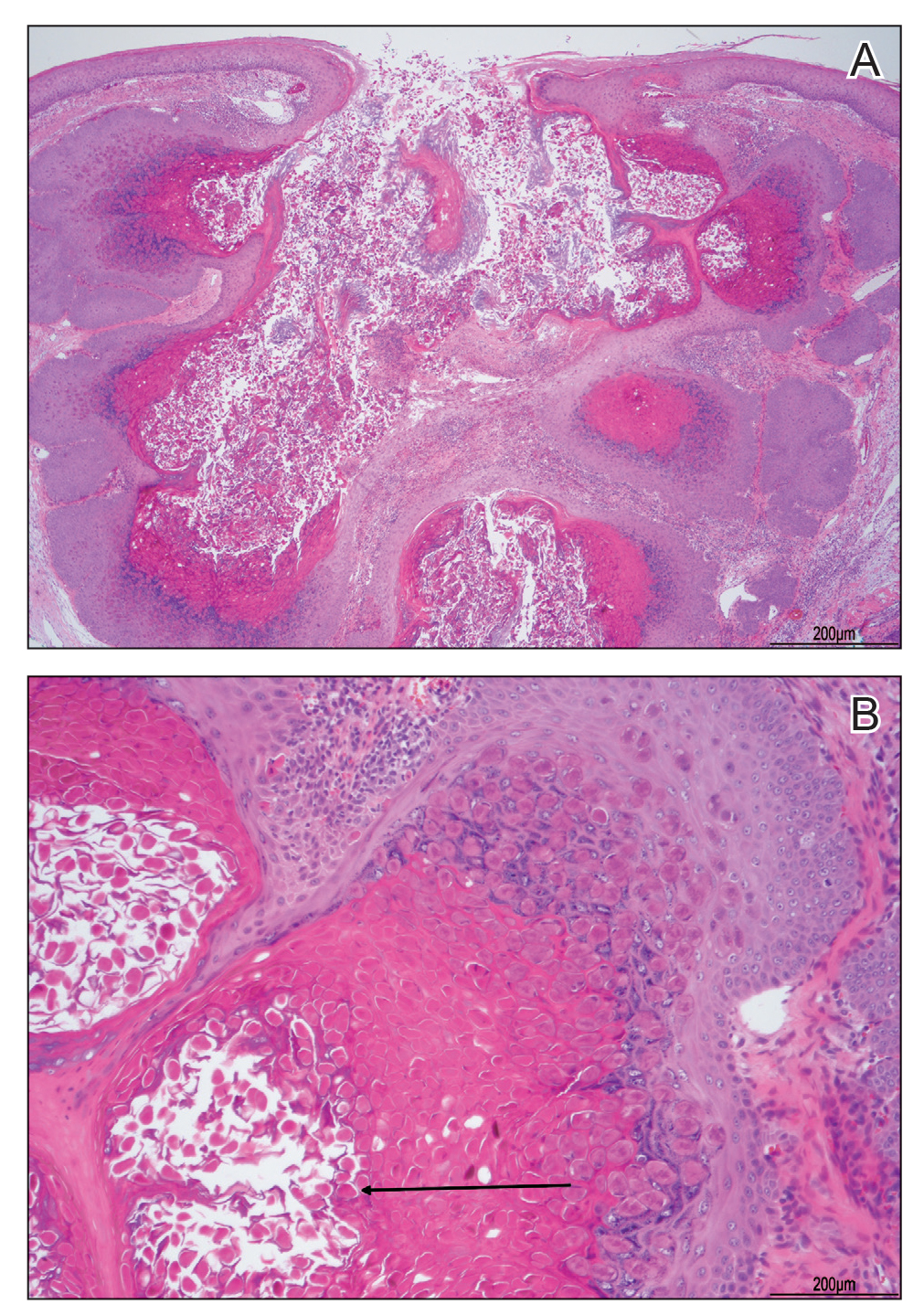

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

A 13-year-old adolescent girl presented for evaluation of a lesion on the dorsal aspect of the right foot of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of acne vulgaris and seasonal allergic rhinitis. She previously had noticed a persistent, small, flesh-colored bump of unknown chronicity in the same location, which had been diagnosed as a skin tag at an outside clinic. She denied any prior treatment in this area. Approximately a week prior to presentation, the lesion became painful, larger, and darkened in color before draining yellowish fluid. Due to concern for superinfection, the patient was prescribed cephalexin by her pediatrician. Dermatologic examination revealed a 1-cm, violaceous, pedunculated plaque with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of the right foot with surrounding erythema and tenderness.