User login

Changing terminology in LGBTQ+ spaces: How to keep up with the lingo

For those of us who see adolescent patients on a regular basis, it seems that they use new vocabulary almost every day. While you may not need to know what “lit” means, you probably do need to understand terms used to describe your patients’ identities. At times it feels like we, as providers, have to be on TikTok to keep up with our patients, and while this may be an amusing way to educate ourselves, a judicious Google search can be much more helpful. The interesting part about LGBTQ+ terminology is that it stems from the community and thus is frequently updated to reflect our evolving understanding of gender, sexuality, and identity. That being said, it can make it difficult for those who are not plugged in to the community to keep up to date. While we have learned in medicine to use accurate terminology and appropriate three-letter acronyms (or “TLAs” as one of my residents referenced them when I was a medical student) to describe medical conditions, the LGBTQ+ community has its own set of terms and acronyms. These new words may seem daunting, but they are often based in Latin roots or prefixes such as a-, demi-, poly-, and pan-, which may be familiar to those of us who use plenty of other Latin-based terms in medicine and our everyday lives. By paying attention to how people define and use terminology, we can better recognize their true identities and become better providers.

The first, and perhaps most important, piece of advice is to maintain cultural humility. Know when to admit you don’t recognize a term and politely ask the definition. For example, the first time I heard the term “demiboy” I said “I’m not familiar with that word. Can you explain what it means to you?” Phrasing the question as such is also helpful in that it gives the individuals a chance to really define their identity. In addition, some words may be used differently by various individuals and by asking what the word means to them, you can have a better understanding of how they are using the terminology. In this particular instance, the patient felt more masculine, but not 100%, partway between agender (meaning having no gender identity) and being “all male.” By embracing cultural humility, we place the patients in the role of expert on their own identity and orientation. According to Maria Ruud, DNP, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, cultural humility is the “ongoing self-reflection and education …[seeking] to gain an awareness of their own assumptions and biases that may contribute to health disparities.”1

Another reason it is important to keep up on the language is that some adolescents, particularly younger adolescents, may not be using the terminology correctly. It can be very helpful to know the difference between polyamorous and pansexual when a 12-year-old describes themselves as polyamorous (having consenting, nonmonogamous relationships) but provides the definition for pansexual (being attracted to all gender identities). Yes, this has happened to me, and yes, my resident was appropriately confused. Correcting someone else’s vocabulary can be tricky and even inappropriate or condescending; therefore, tread cautiously. It may be appropriate, however, to correct colleagues’ or even patients’ family members’ language if they are using terms that may be hurtful to your patients. I do not allow slurs in my clinic, and when parents are using incorrect pronouns on purpose, I will often let them know that it is my job to respect their child’s identity where it is in the moment and that they have asked me to use specific pronouns, so I will continue to refer to their child with those pronouns. Reflecting the language of the patient can be a powerful statement providing them with the autonomy that they deserve as burgeoning adults navigating the complicated journey of identity.

As providers who often have to defend ourselves against “Dr. Google,” we may be leery of just searching randomly for the definition of a new word and hoping a site is credible. One site that I have used repeatedly is www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com by Sam Killermann,2 a gender and sexuality educator.

Mr. Killermann has also produced an E-book that is regularly updated to reflect changing terminology, which can be obtained for a small donation. As Mr. Killermann explains, “New language can be intimidating, and the language of gender and sexuality is often that.”3 In reality, the definitions aren’t scary and often the words can describe something you already know exists but didn’t recognize had a specific term. Not everyone can know every term and its definition; in fact, many members of the LGBTQ+ community don’t know or even understand every term. Below is a shortened list with some of the more common terms you may encounter; however, individuals may use them differently so it is never out of place to clarify your understanding of the term’s definition.

With these resources, along with cultural humility and reflection of others’ language, we can all start to have more meaningful conversations with our patients around their identity and relationships with others.

Dr. Lawlis is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ruud M. Nursing for women’s health. 2018;22(3):255-63.

2. Killermann S. It’s Pronounced Metrosexual. 2020.

3. Killermann S. Defining LGBTQ+: A guide to gender and sexuality terminology. 2019, Feb 25.

4. The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. Oak Brook, Ill. 2011.

5. LGBT health disparities. American Psychiatric Association Public Interest Government Relations Office. 2013 May.

6. Lawlis S et al. Health services for LGBTQ+ patients. Psychiatr Ann. 2019;49(10):426-35.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, department of family and community medicine, UCSF. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2016 Jun 17.

For those of us who see adolescent patients on a regular basis, it seems that they use new vocabulary almost every day. While you may not need to know what “lit” means, you probably do need to understand terms used to describe your patients’ identities. At times it feels like we, as providers, have to be on TikTok to keep up with our patients, and while this may be an amusing way to educate ourselves, a judicious Google search can be much more helpful. The interesting part about LGBTQ+ terminology is that it stems from the community and thus is frequently updated to reflect our evolving understanding of gender, sexuality, and identity. That being said, it can make it difficult for those who are not plugged in to the community to keep up to date. While we have learned in medicine to use accurate terminology and appropriate three-letter acronyms (or “TLAs” as one of my residents referenced them when I was a medical student) to describe medical conditions, the LGBTQ+ community has its own set of terms and acronyms. These new words may seem daunting, but they are often based in Latin roots or prefixes such as a-, demi-, poly-, and pan-, which may be familiar to those of us who use plenty of other Latin-based terms in medicine and our everyday lives. By paying attention to how people define and use terminology, we can better recognize their true identities and become better providers.

The first, and perhaps most important, piece of advice is to maintain cultural humility. Know when to admit you don’t recognize a term and politely ask the definition. For example, the first time I heard the term “demiboy” I said “I’m not familiar with that word. Can you explain what it means to you?” Phrasing the question as such is also helpful in that it gives the individuals a chance to really define their identity. In addition, some words may be used differently by various individuals and by asking what the word means to them, you can have a better understanding of how they are using the terminology. In this particular instance, the patient felt more masculine, but not 100%, partway between agender (meaning having no gender identity) and being “all male.” By embracing cultural humility, we place the patients in the role of expert on their own identity and orientation. According to Maria Ruud, DNP, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, cultural humility is the “ongoing self-reflection and education …[seeking] to gain an awareness of their own assumptions and biases that may contribute to health disparities.”1

Another reason it is important to keep up on the language is that some adolescents, particularly younger adolescents, may not be using the terminology correctly. It can be very helpful to know the difference between polyamorous and pansexual when a 12-year-old describes themselves as polyamorous (having consenting, nonmonogamous relationships) but provides the definition for pansexual (being attracted to all gender identities). Yes, this has happened to me, and yes, my resident was appropriately confused. Correcting someone else’s vocabulary can be tricky and even inappropriate or condescending; therefore, tread cautiously. It may be appropriate, however, to correct colleagues’ or even patients’ family members’ language if they are using terms that may be hurtful to your patients. I do not allow slurs in my clinic, and when parents are using incorrect pronouns on purpose, I will often let them know that it is my job to respect their child’s identity where it is in the moment and that they have asked me to use specific pronouns, so I will continue to refer to their child with those pronouns. Reflecting the language of the patient can be a powerful statement providing them with the autonomy that they deserve as burgeoning adults navigating the complicated journey of identity.

As providers who often have to defend ourselves against “Dr. Google,” we may be leery of just searching randomly for the definition of a new word and hoping a site is credible. One site that I have used repeatedly is www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com by Sam Killermann,2 a gender and sexuality educator.

Mr. Killermann has also produced an E-book that is regularly updated to reflect changing terminology, which can be obtained for a small donation. As Mr. Killermann explains, “New language can be intimidating, and the language of gender and sexuality is often that.”3 In reality, the definitions aren’t scary and often the words can describe something you already know exists but didn’t recognize had a specific term. Not everyone can know every term and its definition; in fact, many members of the LGBTQ+ community don’t know or even understand every term. Below is a shortened list with some of the more common terms you may encounter; however, individuals may use them differently so it is never out of place to clarify your understanding of the term’s definition.

With these resources, along with cultural humility and reflection of others’ language, we can all start to have more meaningful conversations with our patients around their identity and relationships with others.

Dr. Lawlis is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ruud M. Nursing for women’s health. 2018;22(3):255-63.

2. Killermann S. It’s Pronounced Metrosexual. 2020.

3. Killermann S. Defining LGBTQ+: A guide to gender and sexuality terminology. 2019, Feb 25.

4. The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. Oak Brook, Ill. 2011.

5. LGBT health disparities. American Psychiatric Association Public Interest Government Relations Office. 2013 May.

6. Lawlis S et al. Health services for LGBTQ+ patients. Psychiatr Ann. 2019;49(10):426-35.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, department of family and community medicine, UCSF. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2016 Jun 17.

For those of us who see adolescent patients on a regular basis, it seems that they use new vocabulary almost every day. While you may not need to know what “lit” means, you probably do need to understand terms used to describe your patients’ identities. At times it feels like we, as providers, have to be on TikTok to keep up with our patients, and while this may be an amusing way to educate ourselves, a judicious Google search can be much more helpful. The interesting part about LGBTQ+ terminology is that it stems from the community and thus is frequently updated to reflect our evolving understanding of gender, sexuality, and identity. That being said, it can make it difficult for those who are not plugged in to the community to keep up to date. While we have learned in medicine to use accurate terminology and appropriate three-letter acronyms (or “TLAs” as one of my residents referenced them when I was a medical student) to describe medical conditions, the LGBTQ+ community has its own set of terms and acronyms. These new words may seem daunting, but they are often based in Latin roots or prefixes such as a-, demi-, poly-, and pan-, which may be familiar to those of us who use plenty of other Latin-based terms in medicine and our everyday lives. By paying attention to how people define and use terminology, we can better recognize their true identities and become better providers.

The first, and perhaps most important, piece of advice is to maintain cultural humility. Know when to admit you don’t recognize a term and politely ask the definition. For example, the first time I heard the term “demiboy” I said “I’m not familiar with that word. Can you explain what it means to you?” Phrasing the question as such is also helpful in that it gives the individuals a chance to really define their identity. In addition, some words may be used differently by various individuals and by asking what the word means to them, you can have a better understanding of how they are using the terminology. In this particular instance, the patient felt more masculine, but not 100%, partway between agender (meaning having no gender identity) and being “all male.” By embracing cultural humility, we place the patients in the role of expert on their own identity and orientation. According to Maria Ruud, DNP, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, cultural humility is the “ongoing self-reflection and education …[seeking] to gain an awareness of their own assumptions and biases that may contribute to health disparities.”1

Another reason it is important to keep up on the language is that some adolescents, particularly younger adolescents, may not be using the terminology correctly. It can be very helpful to know the difference between polyamorous and pansexual when a 12-year-old describes themselves as polyamorous (having consenting, nonmonogamous relationships) but provides the definition for pansexual (being attracted to all gender identities). Yes, this has happened to me, and yes, my resident was appropriately confused. Correcting someone else’s vocabulary can be tricky and even inappropriate or condescending; therefore, tread cautiously. It may be appropriate, however, to correct colleagues’ or even patients’ family members’ language if they are using terms that may be hurtful to your patients. I do not allow slurs in my clinic, and when parents are using incorrect pronouns on purpose, I will often let them know that it is my job to respect their child’s identity where it is in the moment and that they have asked me to use specific pronouns, so I will continue to refer to their child with those pronouns. Reflecting the language of the patient can be a powerful statement providing them with the autonomy that they deserve as burgeoning adults navigating the complicated journey of identity.

As providers who often have to defend ourselves against “Dr. Google,” we may be leery of just searching randomly for the definition of a new word and hoping a site is credible. One site that I have used repeatedly is www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com by Sam Killermann,2 a gender and sexuality educator.

Mr. Killermann has also produced an E-book that is regularly updated to reflect changing terminology, which can be obtained for a small donation. As Mr. Killermann explains, “New language can be intimidating, and the language of gender and sexuality is often that.”3 In reality, the definitions aren’t scary and often the words can describe something you already know exists but didn’t recognize had a specific term. Not everyone can know every term and its definition; in fact, many members of the LGBTQ+ community don’t know or even understand every term. Below is a shortened list with some of the more common terms you may encounter; however, individuals may use them differently so it is never out of place to clarify your understanding of the term’s definition.

With these resources, along with cultural humility and reflection of others’ language, we can all start to have more meaningful conversations with our patients around their identity and relationships with others.

Dr. Lawlis is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ruud M. Nursing for women’s health. 2018;22(3):255-63.

2. Killermann S. It’s Pronounced Metrosexual. 2020.

3. Killermann S. Defining LGBTQ+: A guide to gender and sexuality terminology. 2019, Feb 25.

4. The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. Oak Brook, Ill. 2011.

5. LGBT health disparities. American Psychiatric Association Public Interest Government Relations Office. 2013 May.

6. Lawlis S et al. Health services for LGBTQ+ patients. Psychiatr Ann. 2019;49(10):426-35.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, department of family and community medicine, UCSF. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2016 Jun 17.

Trans youth in sports

Over the last several years, the United States has seen a substantial increase in proposed legislation directed toward transgender individuals, particularly youth.1 One type of this legislation aims to prevent participation of transgender girls on female sports teams. While at first glance these bills may seem like common sense protections, in reality they are based on little evidence and serve to further marginalize an already-vulnerable population.

The majority of the population, and thus the majority of athletes, are cisgender.2 According a limited data set from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, only 1.8% of high school students identify as transgender.3,4 Overall, this is a very small percentage and it is unlikely that all of them, or even a majority, participate in athletics. In fact, many transgender individuals avoid athletics as it worsens their dysphoria. Winners are no more likely to be transgender than cisgender.

While proponents of this legislation say that trans women have an unfair advantage because of elevated testosterone levels (and thus theoretically increased muscle mass), there is no clear relationship between higher testosterone levels in athletes and improved athletic performance.2 In fact, there are plenty of sports in which a smaller physique may be beneficial, such as gymnastics. A systematic review showed “no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals ... have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition.”5 Furthermore, trans women are not the only women with elevated testosterone levels. Many cisgender women who have polycystic ovary syndrome or a disorder of sexual differentiation can have higher levels of testosterone and theoretically may have higher muscle mass. Who is to decide which team would be most appropriate for them? Is the plan to require a karyotype, other genetic testing, or an invasive physical exam for every young athlete? Even if the concern is with regards to testosterone levels and muscle mass, this ignores that fact that appropriate medical intervention for transgender adolescents will alter these attributes. If a transgender girl began gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists early in puberty, she is unlikely to have increased muscle mass or a higher testosterone level than a cisgender girl. Those trans girls who take estradiol also experience a decrease in muscle mass. Additionally, adolescents grow and develop at different rates – surely there is already significant variability among hormone levels, muscle mass, sexual maturity ratings, and ability among individual athletes, regardless of gender identity? The argument that trans women should be excluded based on a theoretical genetic advantage is reminiscent of the argument that Black athletes should be excluded because of genetic advantage. Just as with cisgender athletes, transgender athletes will naturally vary in ability.6

In addition, there are many places and organizations that already have trans-inclusive policies in place for sports, yet we have not seen transgender individuals dominate their peers. In the 8 years since implementation of a trans-inclusive sports policy in California, a trans woman has never dominated a sport.7 The same is true for Canada since the institution of their policy 2 years ago. While transgender people can participate in the Olympics, this year marks the first time a trans woman has ever qualified (Laurel Hubbard, New Zealand, women’s weightlifting). The lack of transgender Olympians may be in part because of problematic requirements (such as duration of hormone therapy and surgery requirements) for transgender individuals, which may be so onerous that they are functionally excluded.2,5

In reality, athletes are improving over time and the performance gap between genders is shrinking. For example, in 1970 Mark Spitz swam the 100-meter freestyle in 51.94 seconds, a time that has now been surpassed by both men and women, such as Sarah Sjöström (women’s world record holder at 51.71 seconds). Athletes’ physical attributes are often less important than their training and dedication to their sport.

More importantly, this discussion raises the philosophical question of the purpose of athletics for youth and young adults. Winning and good performance can – though rarely – lead to college scholarships and professional careers, the biggest benefit of athletics comes from participation. We encourage youth to play sports not to win, but to learn about leadership, dedication, and collegiality, as well as for the health benefits of exercise. Inclusion in sports and other extracurricular activities improves depression, anxiety, and suicide rates. In fact, participation in sports has been associated with improved grades, greater homework completion, higher educational and occupational aspirations, and improved self-esteem.8-12 Excluding a population that already experiences such drastic marginalization will cause more damage. Values of nondiscrimination and inclusion should be promoted among all student athletes, rather than “other-ism.”

Forcing trans women to compete with men will worsen their dysphoria and further ostracize the most vulnerable, giving credence to those that believe they are not “real women.” Allowing transgender individuals to play on the team consistent with their gender identity is appropriate, not only for scientific reasons but also for humanitarian ones. Such laws are based not on evidence, but on discrimination. Not only do trans women not do better than cisgender women in sports, but such proposed legislation also ignores the normal variability among individuals as well as the intense training and dedication involved in becoming a top athlete. Limiting trans women’s participation in sports does not raise up cisgender women, but rather brings us all down. Please advocate for your patients to participate in athletics in accordance with their gender identity to promote both their physical and emotional well-being.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cooper MB. Pediatric News. 2020 Dec 11, 2020.

2. Turban J. Scientific American. 2021 May 21.

3. Redfield RR et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(8):1-11.

4. Johns MM et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67-71.

5. Jones BA et al. Sports Med (Auckland, New Zealand). 2017;47(4):701-16.

6. Strangio C et al. ACLU News. 2020 Apr 30.

7. Strauss L. USA Today. 2021 Apr 9.

8. Darling N et al. J Leisure Res. 2005;37(1):51-76.

9. Fredricks JA et al. Dev Psych. 2006;42(4):698-713.

10. Marsh HW et al. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2003;25(2):205.

11. Nelson MC et al. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1281-90.

12. Ortega FB et al. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1-11.

Over the last several years, the United States has seen a substantial increase in proposed legislation directed toward transgender individuals, particularly youth.1 One type of this legislation aims to prevent participation of transgender girls on female sports teams. While at first glance these bills may seem like common sense protections, in reality they are based on little evidence and serve to further marginalize an already-vulnerable population.

The majority of the population, and thus the majority of athletes, are cisgender.2 According a limited data set from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, only 1.8% of high school students identify as transgender.3,4 Overall, this is a very small percentage and it is unlikely that all of them, or even a majority, participate in athletics. In fact, many transgender individuals avoid athletics as it worsens their dysphoria. Winners are no more likely to be transgender than cisgender.

While proponents of this legislation say that trans women have an unfair advantage because of elevated testosterone levels (and thus theoretically increased muscle mass), there is no clear relationship between higher testosterone levels in athletes and improved athletic performance.2 In fact, there are plenty of sports in which a smaller physique may be beneficial, such as gymnastics. A systematic review showed “no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals ... have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition.”5 Furthermore, trans women are not the only women with elevated testosterone levels. Many cisgender women who have polycystic ovary syndrome or a disorder of sexual differentiation can have higher levels of testosterone and theoretically may have higher muscle mass. Who is to decide which team would be most appropriate for them? Is the plan to require a karyotype, other genetic testing, or an invasive physical exam for every young athlete? Even if the concern is with regards to testosterone levels and muscle mass, this ignores that fact that appropriate medical intervention for transgender adolescents will alter these attributes. If a transgender girl began gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists early in puberty, she is unlikely to have increased muscle mass or a higher testosterone level than a cisgender girl. Those trans girls who take estradiol also experience a decrease in muscle mass. Additionally, adolescents grow and develop at different rates – surely there is already significant variability among hormone levels, muscle mass, sexual maturity ratings, and ability among individual athletes, regardless of gender identity? The argument that trans women should be excluded based on a theoretical genetic advantage is reminiscent of the argument that Black athletes should be excluded because of genetic advantage. Just as with cisgender athletes, transgender athletes will naturally vary in ability.6

In addition, there are many places and organizations that already have trans-inclusive policies in place for sports, yet we have not seen transgender individuals dominate their peers. In the 8 years since implementation of a trans-inclusive sports policy in California, a trans woman has never dominated a sport.7 The same is true for Canada since the institution of their policy 2 years ago. While transgender people can participate in the Olympics, this year marks the first time a trans woman has ever qualified (Laurel Hubbard, New Zealand, women’s weightlifting). The lack of transgender Olympians may be in part because of problematic requirements (such as duration of hormone therapy and surgery requirements) for transgender individuals, which may be so onerous that they are functionally excluded.2,5

In reality, athletes are improving over time and the performance gap between genders is shrinking. For example, in 1970 Mark Spitz swam the 100-meter freestyle in 51.94 seconds, a time that has now been surpassed by both men and women, such as Sarah Sjöström (women’s world record holder at 51.71 seconds). Athletes’ physical attributes are often less important than their training and dedication to their sport.

More importantly, this discussion raises the philosophical question of the purpose of athletics for youth and young adults. Winning and good performance can – though rarely – lead to college scholarships and professional careers, the biggest benefit of athletics comes from participation. We encourage youth to play sports not to win, but to learn about leadership, dedication, and collegiality, as well as for the health benefits of exercise. Inclusion in sports and other extracurricular activities improves depression, anxiety, and suicide rates. In fact, participation in sports has been associated with improved grades, greater homework completion, higher educational and occupational aspirations, and improved self-esteem.8-12 Excluding a population that already experiences such drastic marginalization will cause more damage. Values of nondiscrimination and inclusion should be promoted among all student athletes, rather than “other-ism.”

Forcing trans women to compete with men will worsen their dysphoria and further ostracize the most vulnerable, giving credence to those that believe they are not “real women.” Allowing transgender individuals to play on the team consistent with their gender identity is appropriate, not only for scientific reasons but also for humanitarian ones. Such laws are based not on evidence, but on discrimination. Not only do trans women not do better than cisgender women in sports, but such proposed legislation also ignores the normal variability among individuals as well as the intense training and dedication involved in becoming a top athlete. Limiting trans women’s participation in sports does not raise up cisgender women, but rather brings us all down. Please advocate for your patients to participate in athletics in accordance with their gender identity to promote both their physical and emotional well-being.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cooper MB. Pediatric News. 2020 Dec 11, 2020.

2. Turban J. Scientific American. 2021 May 21.

3. Redfield RR et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(8):1-11.

4. Johns MM et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67-71.

5. Jones BA et al. Sports Med (Auckland, New Zealand). 2017;47(4):701-16.

6. Strangio C et al. ACLU News. 2020 Apr 30.

7. Strauss L. USA Today. 2021 Apr 9.

8. Darling N et al. J Leisure Res. 2005;37(1):51-76.

9. Fredricks JA et al. Dev Psych. 2006;42(4):698-713.

10. Marsh HW et al. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2003;25(2):205.

11. Nelson MC et al. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1281-90.

12. Ortega FB et al. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1-11.

Over the last several years, the United States has seen a substantial increase in proposed legislation directed toward transgender individuals, particularly youth.1 One type of this legislation aims to prevent participation of transgender girls on female sports teams. While at first glance these bills may seem like common sense protections, in reality they are based on little evidence and serve to further marginalize an already-vulnerable population.

The majority of the population, and thus the majority of athletes, are cisgender.2 According a limited data set from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, only 1.8% of high school students identify as transgender.3,4 Overall, this is a very small percentage and it is unlikely that all of them, or even a majority, participate in athletics. In fact, many transgender individuals avoid athletics as it worsens their dysphoria. Winners are no more likely to be transgender than cisgender.

While proponents of this legislation say that trans women have an unfair advantage because of elevated testosterone levels (and thus theoretically increased muscle mass), there is no clear relationship between higher testosterone levels in athletes and improved athletic performance.2 In fact, there are plenty of sports in which a smaller physique may be beneficial, such as gymnastics. A systematic review showed “no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals ... have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition.”5 Furthermore, trans women are not the only women with elevated testosterone levels. Many cisgender women who have polycystic ovary syndrome or a disorder of sexual differentiation can have higher levels of testosterone and theoretically may have higher muscle mass. Who is to decide which team would be most appropriate for them? Is the plan to require a karyotype, other genetic testing, or an invasive physical exam for every young athlete? Even if the concern is with regards to testosterone levels and muscle mass, this ignores that fact that appropriate medical intervention for transgender adolescents will alter these attributes. If a transgender girl began gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists early in puberty, she is unlikely to have increased muscle mass or a higher testosterone level than a cisgender girl. Those trans girls who take estradiol also experience a decrease in muscle mass. Additionally, adolescents grow and develop at different rates – surely there is already significant variability among hormone levels, muscle mass, sexual maturity ratings, and ability among individual athletes, regardless of gender identity? The argument that trans women should be excluded based on a theoretical genetic advantage is reminiscent of the argument that Black athletes should be excluded because of genetic advantage. Just as with cisgender athletes, transgender athletes will naturally vary in ability.6

In addition, there are many places and organizations that already have trans-inclusive policies in place for sports, yet we have not seen transgender individuals dominate their peers. In the 8 years since implementation of a trans-inclusive sports policy in California, a trans woman has never dominated a sport.7 The same is true for Canada since the institution of their policy 2 years ago. While transgender people can participate in the Olympics, this year marks the first time a trans woman has ever qualified (Laurel Hubbard, New Zealand, women’s weightlifting). The lack of transgender Olympians may be in part because of problematic requirements (such as duration of hormone therapy and surgery requirements) for transgender individuals, which may be so onerous that they are functionally excluded.2,5

In reality, athletes are improving over time and the performance gap between genders is shrinking. For example, in 1970 Mark Spitz swam the 100-meter freestyle in 51.94 seconds, a time that has now been surpassed by both men and women, such as Sarah Sjöström (women’s world record holder at 51.71 seconds). Athletes’ physical attributes are often less important than their training and dedication to their sport.

More importantly, this discussion raises the philosophical question of the purpose of athletics for youth and young adults. Winning and good performance can – though rarely – lead to college scholarships and professional careers, the biggest benefit of athletics comes from participation. We encourage youth to play sports not to win, but to learn about leadership, dedication, and collegiality, as well as for the health benefits of exercise. Inclusion in sports and other extracurricular activities improves depression, anxiety, and suicide rates. In fact, participation in sports has been associated with improved grades, greater homework completion, higher educational and occupational aspirations, and improved self-esteem.8-12 Excluding a population that already experiences such drastic marginalization will cause more damage. Values of nondiscrimination and inclusion should be promoted among all student athletes, rather than “other-ism.”

Forcing trans women to compete with men will worsen their dysphoria and further ostracize the most vulnerable, giving credence to those that believe they are not “real women.” Allowing transgender individuals to play on the team consistent with their gender identity is appropriate, not only for scientific reasons but also for humanitarian ones. Such laws are based not on evidence, but on discrimination. Not only do trans women not do better than cisgender women in sports, but such proposed legislation also ignores the normal variability among individuals as well as the intense training and dedication involved in becoming a top athlete. Limiting trans women’s participation in sports does not raise up cisgender women, but rather brings us all down. Please advocate for your patients to participate in athletics in accordance with their gender identity to promote both their physical and emotional well-being.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cooper MB. Pediatric News. 2020 Dec 11, 2020.

2. Turban J. Scientific American. 2021 May 21.

3. Redfield RR et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(8):1-11.

4. Johns MM et al. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67-71.

5. Jones BA et al. Sports Med (Auckland, New Zealand). 2017;47(4):701-16.

6. Strangio C et al. ACLU News. 2020 Apr 30.

7. Strauss L. USA Today. 2021 Apr 9.

8. Darling N et al. J Leisure Res. 2005;37(1):51-76.

9. Fredricks JA et al. Dev Psych. 2006;42(4):698-713.

10. Marsh HW et al. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2003;25(2):205.

11. Nelson MC et al. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1281-90.

12. Ortega FB et al. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1-11.

The importance of family acceptance for LGBTQ youth

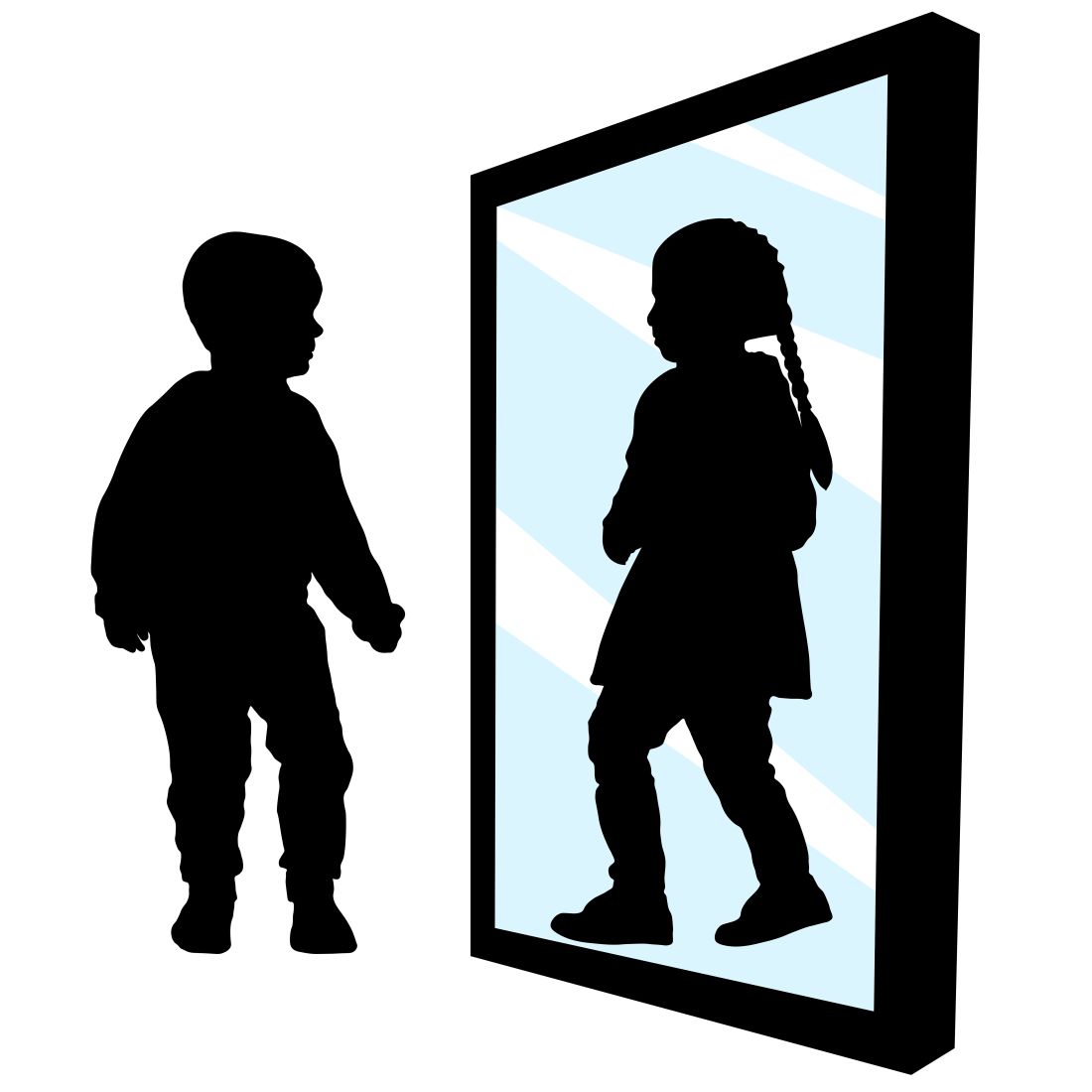

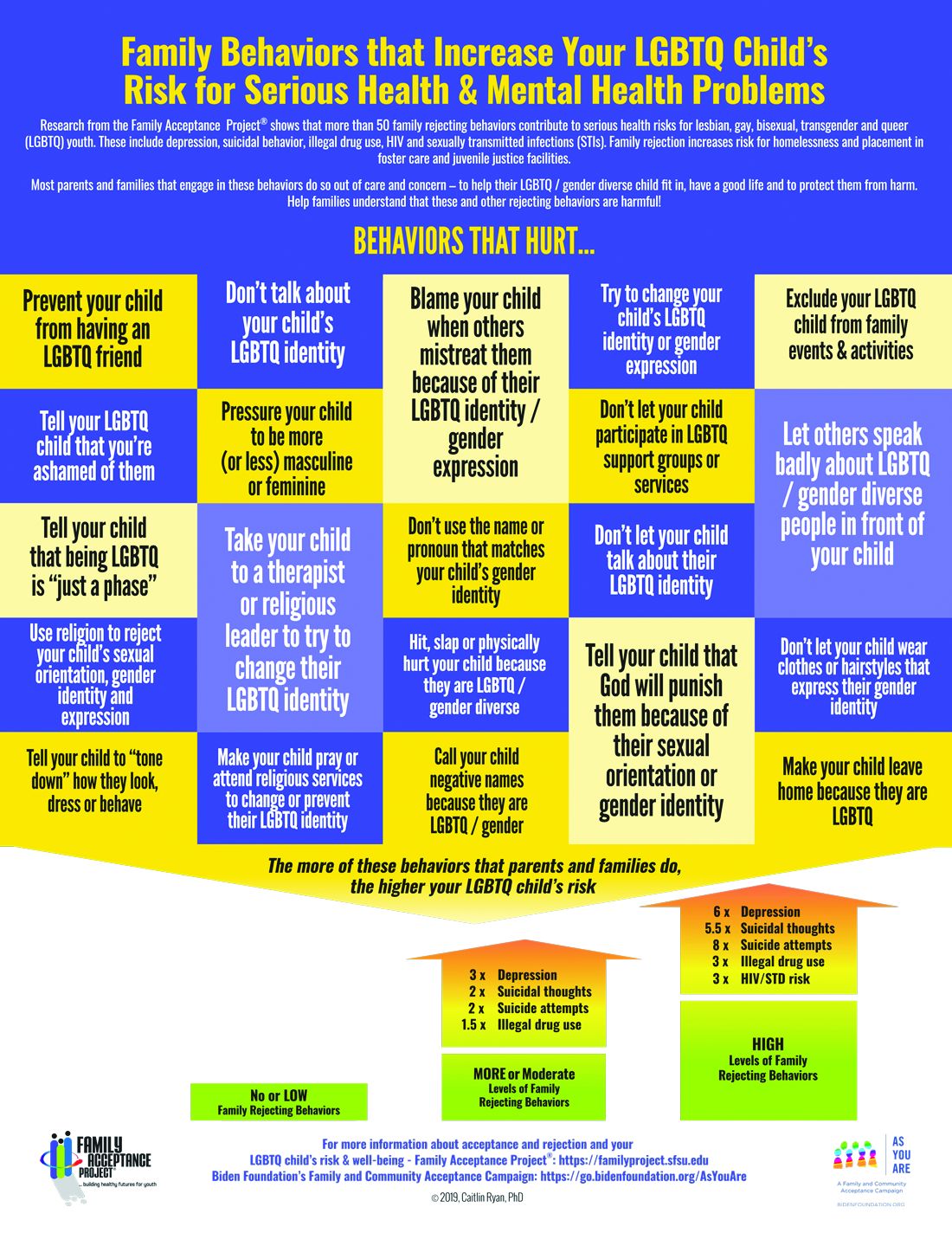

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

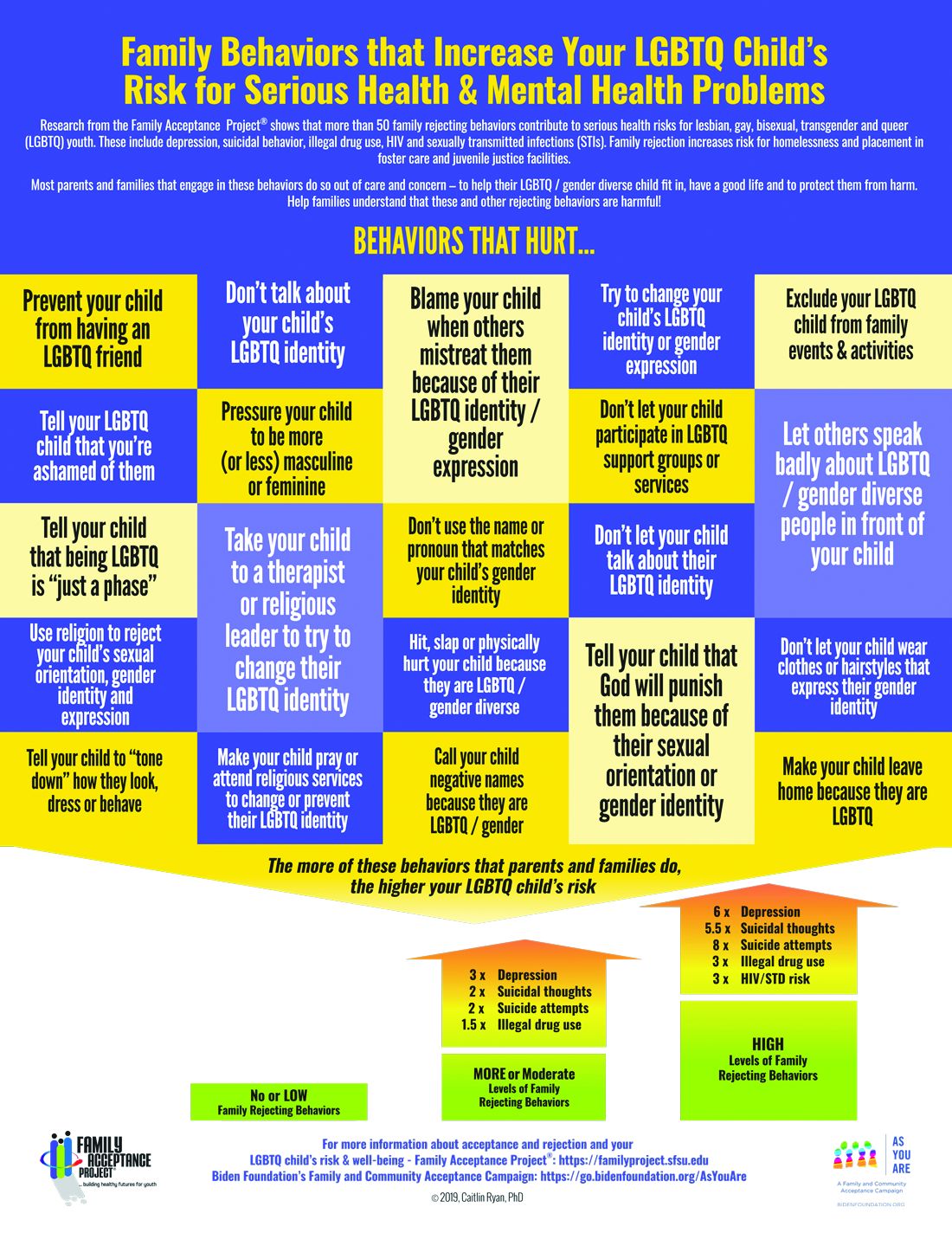

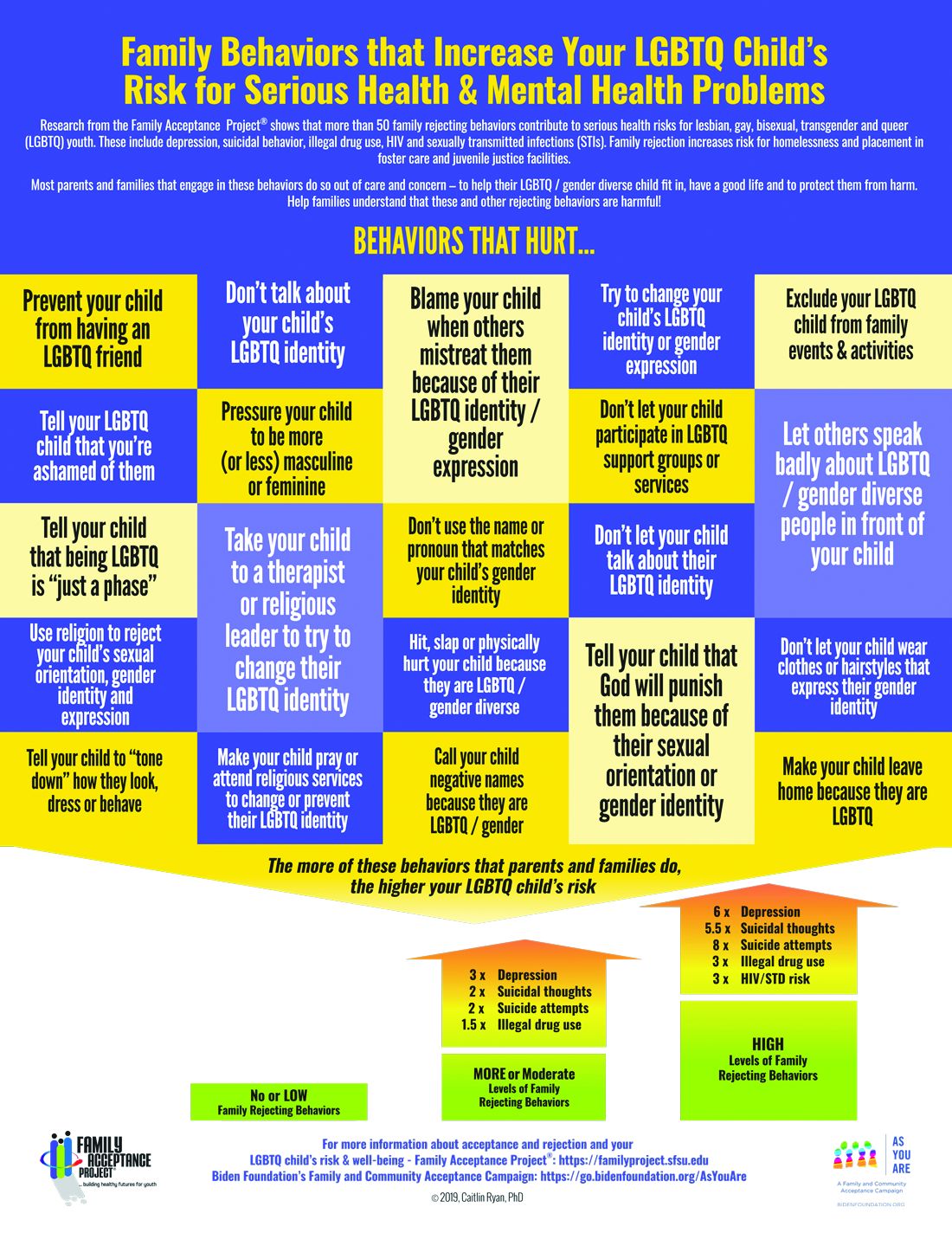

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

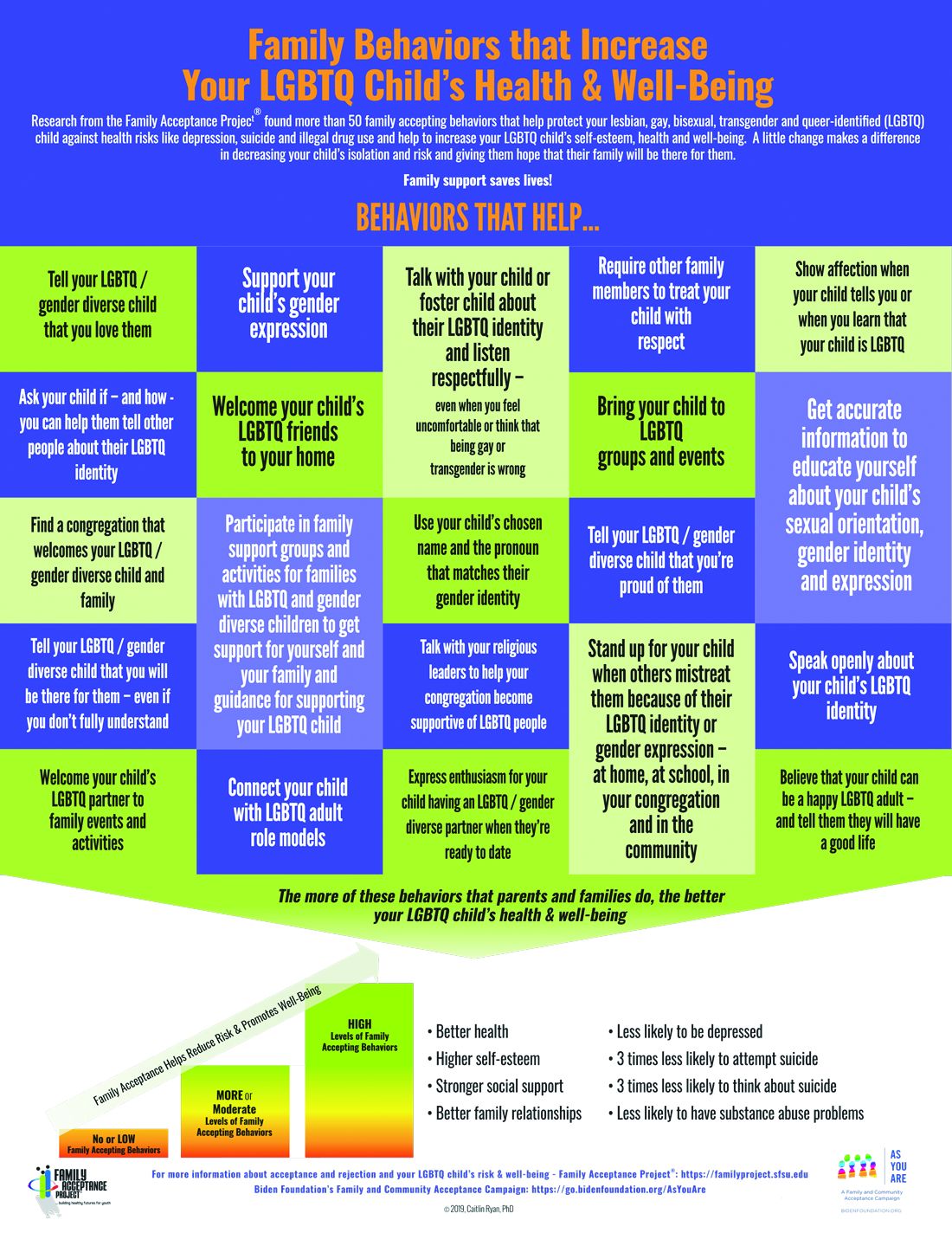

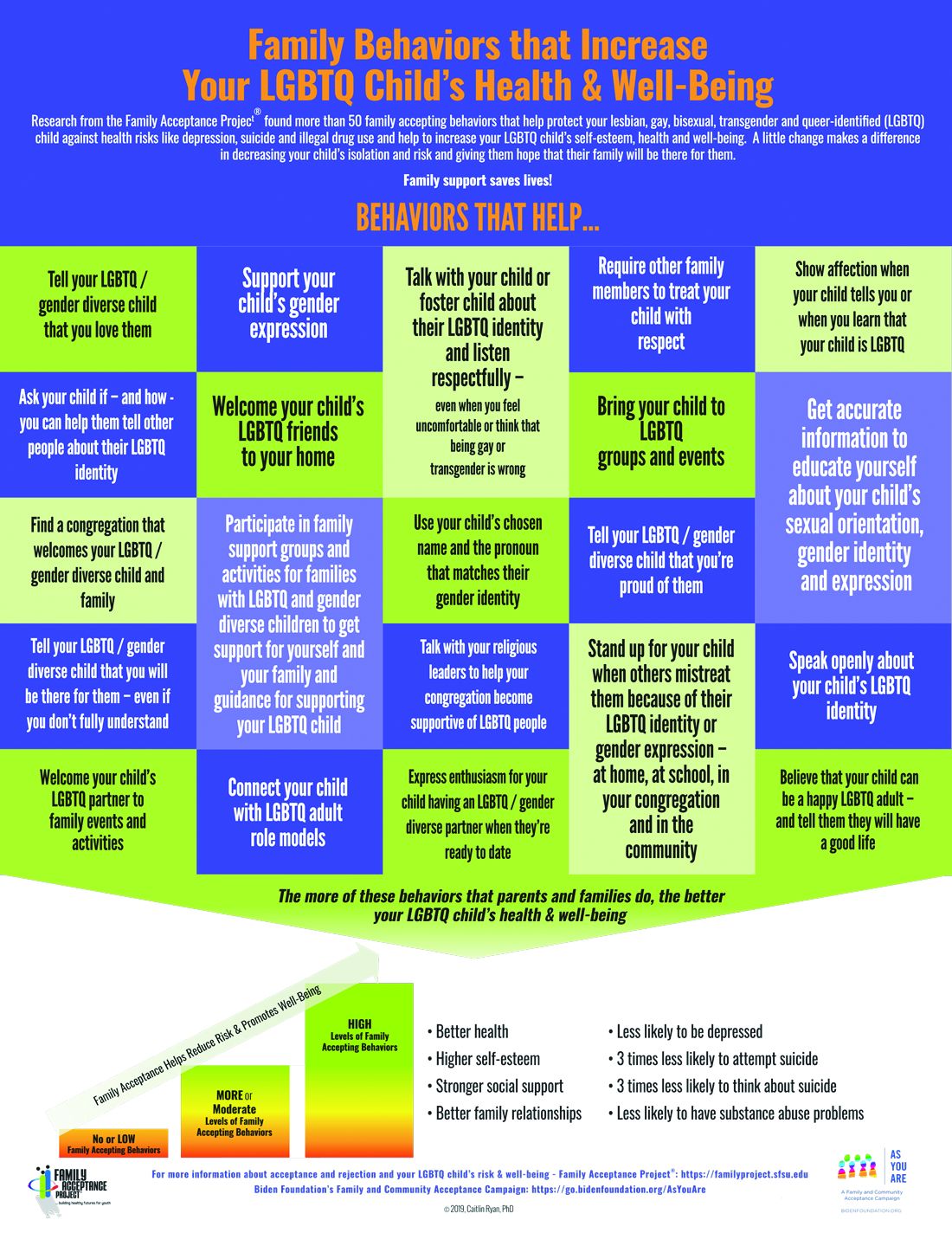

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

All about puberty blockers!

While many transgender individuals develop their gender identity early on in life, medically there may not be any intervention until they hit puberty. For prepubertal children, providing a supportive environment and letting them explore gender expression with haircut, clothing, toys, name, and pronouns may be the main “interventions.” Ensure a safe bathroom and safe spaces at school (and home), and perhaps find an experienced therapist comfortable navigating gender concerns. Supporting the family supports the child and can make all the difference in the world. Often clinics specializing in gender care will see young children to provide this support and follow the child into puberty.

Once puberty starts, however, medical interventions can be discussed and puberty blockers are a great place to start, given their reversibility. Having an understanding of how puberty blockers work, the side effects, and timing of blocker use is important to the average pediatric provider as you may see some of these children and be able to intervene by sending them to a specialist early!

How do puberty blockers work?

One of the first hormonal signals of puberty is the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. GnRH stimulates the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary. LH and FSH then stimulate sex steroidogenesis (production of estradiol or testosterone) and gametogenesis in the gonads. The most common choice for puberty blockers are GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide (a series of shots) or histrelin (an implantable rod), which have been studied extensively for the treatment of children with central precocious puberty, and more recently gender dysphoria. Interestingly, these medicines actually stimulate gonadotropin release and the overproduction makes the gonadotropin receptors less sensitive.1 Gradually the production of sex steroids decreases. allowing one to proceed with natal puberty if one so desires. Gender specialists always start with the most reversible intervention, especially at such a young age. Puberty blockers are like a pause button that gives everyone – patient, clinicians, therapists – time to process, explore, and ensure transition is the right path.

Sexual development should stop on puberty blockers. For those born with ovaries, breasts will not continue to develop and menses will not start if premenarchal or stop soon if postmenarchal. For those born with testicles, testicular and penile enlargement will not proceed, the voice will not deepen, hands will not grow in size, and an “Adam’s apple” will not develop. Preventing these changes may not only prevent future surgeries (mastectomy, tracheal shaving, etc.) but may also be lifesaving given the lack of development as secondary sex characteristics may not develop, thus avoiding telltale signs that one has transitioned physically, particularly for transwomen.

What are the side effects of puberty blockers?

Whenever an adolescent is started on puberty blockers, it is important to discuss both the main effects (i.e., cessation of puberty and sexual development) as well as the side effects. There are four main side effect areas that are important to cover: bone health and height, brain development, fertility, and surgical implications.

- Bone health & height. Adolescence is an important time for growth. During adolescence, bones grow both in length, which determines an individual’s height, and in density, which can affect risk of osteoporosis later on in life. Sex steroids are an important factor for both of these issues. Estradiol is responsible for closure of the growth plates and, in general, those born with ovaries enter puberty earlier than those born with testicles, therefore they see higher rates of estradiol earlier, which causes cessation of growth, hence why females are typically shorter than males. Delaying these high levels of estrogen may give transmales (female to male individuals) more time to grow. Conversely, decreasing release of testosterone in transfemales (male to female individuals) and then introducing estradiol at higher levels earlier than they would experience with their natal puberty may stop transfemales from growing much taller than the average cisgender woman. Bone density also is a major concern as the sex steroids are very important for bone mass accretion.1,2 Studies in transgender individuals using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry show that, for transmale patients, z scores do decrease but they tend to catch up once gender-affirming hormones are started. For transfemale patients, the z scores don’t decrease as much but also don’t increase as much once estrogen is started.1,3 It is for these reasons that the Endocrine Society guidelines recommend monitoring bone density both before and while on puberty blockers.4,5

- Brain development. Adolescence also is an important time for brain development, particularly the areas that focus on executive function. Studies comparing transgender patients on GnRH agonists noted no detrimental effects on higher-order cognitive process associated with a specific task meant to test executive function.6 Although not performed on transgender individuals, a study examining girls with central precocious puberty on GnRH agonists found no difference with the control group on auditory and visual memory, response inhibition, spatial ability, behavioral problems, or social competence.7

- Fertility. Suspending puberty at an early Sexual Maturity Rating (such as stage 2 or 3) may make it difficult to harvest mature oocytes or spermatozoa, thus compromising long-term fertility, especially once they start on gender-affirming hormones. While some patients may choose to delay starting puberty blockers for the sake of cryopreservation, others may be in too much distress at their pubertal changes to wait. Fertility counseling is thus an important aspect of the discussion with transgender patients considering puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones.

- Surgical implications. The most common “bottom surgery” performed in transfemales is called penile inversion vaginoplasty, which uses the penile and scrotal skin to create a neovagina.8 However, one has to have enough penile and scrotal development for this surgery to be successful, which may mean waiting until a patient has reached Sexual Maturity Rating stage 4 before starting blockers. There are alternative surgical options, but one must discuss the risks and benefits of waiting to start blockers with the patient and family.

When can puberty blockers be started?

Patients must meet criteria for gender dysphoria with emergence or worsening with puberty.9 Any coexisting conditions (psychological, medical, social) that could interfere with treatment have to be addressed, and both the patient and their guardian must undergo informed consent for treatment.4,5,10 Puberty blockers cannot be used until after puberty has started, so at least Sexual Maturity Rating stage 2. In the early stages of puberty, hormonally one will see LH rise followed by rise in estradiol and/or testosterone. Consideration for both the development of secondary sex characteristics and associated increased distress or dysphoria as well as surgical implications must be weighed in each individual case. The bottom line is that these medications can be life saving and are reversible, so if a patient and/or family decides to stop them, the effects will wear off and natal puberty will resume.

Dr. Lawlis is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30099-2.

2. Bone. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.005.

3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Feb. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2439.

4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0345.

5. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01658.

6. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.03.007.

7. Front Psychol. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01053.

8. Sex Med Rev. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.08.001.

9. “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” 5th ed. (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

10. Int J Transgend. 2012. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873.

While many transgender individuals develop their gender identity early on in life, medically there may not be any intervention until they hit puberty. For prepubertal children, providing a supportive environment and letting them explore gender expression with haircut, clothing, toys, name, and pronouns may be the main “interventions.” Ensure a safe bathroom and safe spaces at school (and home), and perhaps find an experienced therapist comfortable navigating gender concerns. Supporting the family supports the child and can make all the difference in the world. Often clinics specializing in gender care will see young children to provide this support and follow the child into puberty.

Once puberty starts, however, medical interventions can be discussed and puberty blockers are a great place to start, given their reversibility. Having an understanding of how puberty blockers work, the side effects, and timing of blocker use is important to the average pediatric provider as you may see some of these children and be able to intervene by sending them to a specialist early!

How do puberty blockers work?

One of the first hormonal signals of puberty is the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. GnRH stimulates the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary. LH and FSH then stimulate sex steroidogenesis (production of estradiol or testosterone) and gametogenesis in the gonads. The most common choice for puberty blockers are GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide (a series of shots) or histrelin (an implantable rod), which have been studied extensively for the treatment of children with central precocious puberty, and more recently gender dysphoria. Interestingly, these medicines actually stimulate gonadotropin release and the overproduction makes the gonadotropin receptors less sensitive.1 Gradually the production of sex steroids decreases. allowing one to proceed with natal puberty if one so desires. Gender specialists always start with the most reversible intervention, especially at such a young age. Puberty blockers are like a pause button that gives everyone – patient, clinicians, therapists – time to process, explore, and ensure transition is the right path.

Sexual development should stop on puberty blockers. For those born with ovaries, breasts will not continue to develop and menses will not start if premenarchal or stop soon if postmenarchal. For those born with testicles, testicular and penile enlargement will not proceed, the voice will not deepen, hands will not grow in size, and an “Adam’s apple” will not develop. Preventing these changes may not only prevent future surgeries (mastectomy, tracheal shaving, etc.) but may also be lifesaving given the lack of development as secondary sex characteristics may not develop, thus avoiding telltale signs that one has transitioned physically, particularly for transwomen.

What are the side effects of puberty blockers?

Whenever an adolescent is started on puberty blockers, it is important to discuss both the main effects (i.e., cessation of puberty and sexual development) as well as the side effects. There are four main side effect areas that are important to cover: bone health and height, brain development, fertility, and surgical implications.