User login

A Review of Online Search Tools to Identify Funded Dermatology Away Rotations for Underrepresented Medical Students

A Review of Online Search Tools to Identify Funded Dermatology Away Rotations for Underrepresented Medical Students

Most medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States will participate in an away rotation at an outside institution. Prior to COVID-19–related restrictions, 86.7% of dermatology applicants from the class of 2020 reported completing one or more away rotations for their application cycle.1,2 This requirement can be considerably costly, especially since most programs do not offer financial support for travel, living expenses, or housing during these visiting experiences.3 Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) students may be particularly disadvantaged with regard to the financial obligations that come with away rotations.4,5 Visiting scholarships for URiM students can mitigate these challenges, creating opportunities for increasing diversity in dermatology. When medical students begin the residency application process, the Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) program of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) is the most widely used third-party service for submitting applications. For many URiM students, an unforeseen challenge when applying to dermatology residency programs is the lack of an easily accessible and up-to-date search tool to find programs that offer funding, resulting in more time spent searching and thereby complicating the application process. The VSLO released the Visiting Scholars Resources Database, a search tool that aims to compile opportunities for additional support—academic professional, and/or financial—to address this issue. Additionally, the Funded Away Rotations for Minority Medical Students (FARMS) database is an independent directory of programs that offer stipends to URiM students. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the VLSO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database search tool and the FARMS database in identifying funded dermatology rotations for URiM students.

Overview of Online Search Tools

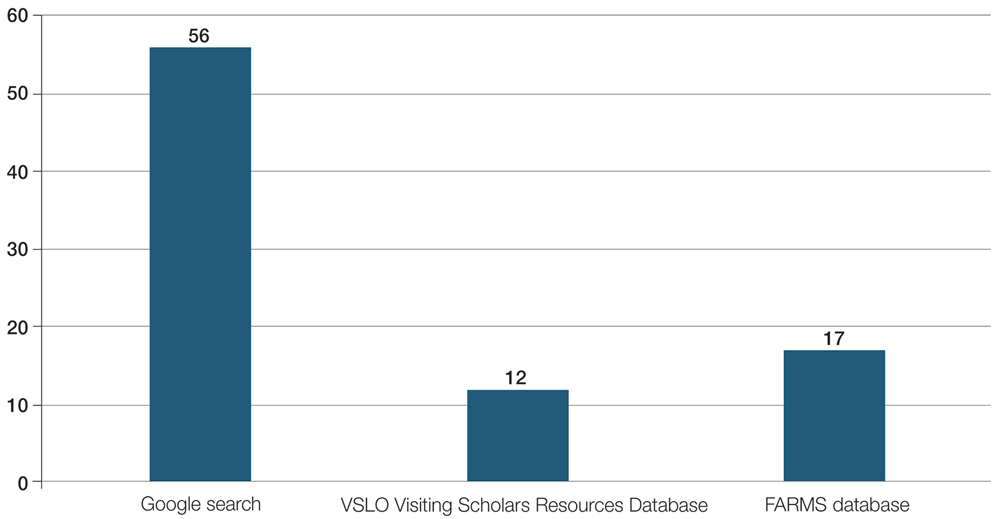

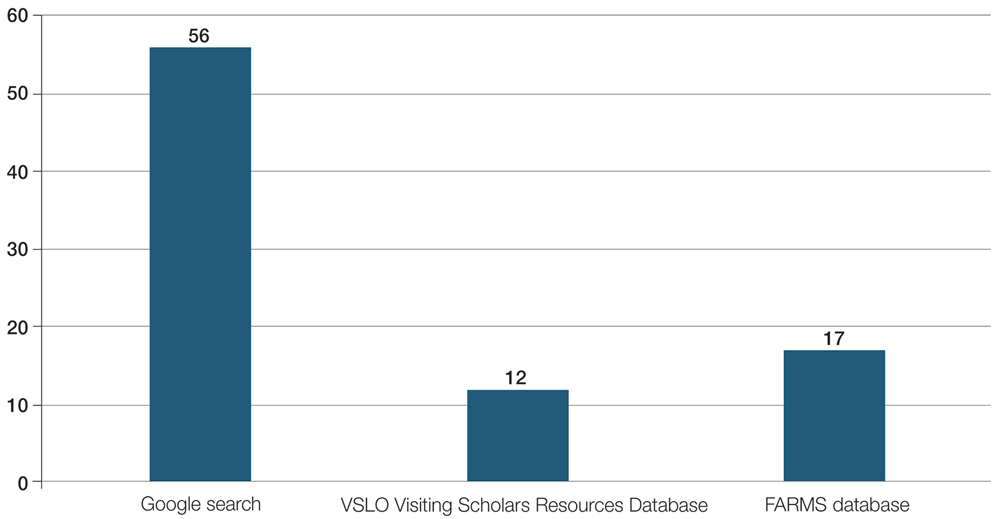

We used the AAMC’s Electronic Residency Application Service Directory to identify 141 programs offering dermatology residency positions. We then conducted a Google search using each program name with the phrase underrepresented in medicine dermatology away rotation to identify any opportunities noted in the Google results offering scholarship funding for URiM students. If there were no Google results for a webpage discussing URiM away rotation opportunities for a certain program, the individual program’s website search box was queried using the terms URiM, scholarship, and funding. If there were no relevant results, the webpages associated with the dermatology department, away rotations, and diversity and inclusion on the respective institution’s website were reviewed to confirm no indication of funded URiM opportunities. Of the 141 dermatology programs we evaluated, we identified 56 (39.7%) that offered funded away rotations for URiM students.

For comparison, we conducted a search of the VSLO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database to identify programs that listed dermatology, all (specialties), or any (specialties) under the Specialty column that also had a financial resource for URiM students. Our search of the VSLO database yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we identified via our initial Google and program website search. Program listings tagged for dermatology also were retrieved from the FARMS database, of which only 17 (30.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we previously identified were included. All queries were performed from October 24 to October 26, 2024 (Figure).

Comment

The 2023-2024 AAMC Report on Residents indicated that 54.9% (800/1455) of active US dermatology medical residents identified as White, 27.5% (400/1455) identified as Asian, 8.9% (129/1455) identified as Hispanic, and 8.7% (126/1455) identified as Black or African American.6 By comparison, 19.5% of the general US population identifies as Hispanic and 13.7% identifies as Black.7 Within the field of dermatology, the proportion of Black dermatology academic faculty in the US is estimated to comprise only 18.7% of all active Black dermatologists.8,9 With a growing population of minority US citizens, the dermatology workforce is lagging in representation across all minority populations, especially when it comes to Hispanic and Black individuals. To increase the diversity of the US dermatology workforce, residency programs must prioritize recruitment of URiM students and support their retention as future faculty.

Reports in the literature suggest that clinical grades, US Medical Licensing Examination scores, letters of recommendation/ networking, and the risk of not matching are among the primary concerns that URiM students face as potential barriers to applying for dermatology residency.4 Meanwhile, dermatology program directors ranked diversity characteristics, perceived interest in the program, personal prior knowledge of an applicant, and audition rotation in their department as important considerations for interviewing applicants.10 As a result, URiM students may have the diverse characteristics that program directors are looking for, but obtaining away rotations and establishing mentors at other institutions may be challenging due to the burden of accruing additional costs for visiting rotations.2,10,11 Other reports have indicated that expanding funded dermatology visiting rotations and promoting national programs such as the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/awards/diversity) or the Skin of Color Society Observership Grant (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/what-we-do/mentorship/observership-grant) can be alternative routes for mentorship and networking.3

Our review demonstrated that, of the 141 dermatology residency programs we identified, only around 40% offer funded rotations for URiM students; however, the current databases that applicants use to find these opportunities do not adequately present the number of available options. A search of the VSLO database—the most widely used third-party database for applying to dermatology away rotations—yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the rotations that we identified in our initial Google search. Similarly, a search of the FARMS database yielded only 17 (30.4%) of the dermatology rotations we previously identified. Aside from missing more than half of the available funded dermatology away rotations, the search process was further complicated by the reliance of the 2 databases on user input rather than presenting all programs offering funded opportunities for dermatology applicants without the need to enter additional information. As of October 26, 2024, there were only 22 inputs for Visiting Scholars Resources across all specialties and programs in the VLSO system.

Our findings indicate a clear need for a reliable and accurate database that captures all funded dermatology rotations for prospective URiM applicants because of the strong emphasis on visiting rotations for application success. Our team created a Google spreadsheet compiling dermatology visiting student health equity and inclusion scholarships from inputs we found in our search. We shared this resource via the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve so program members could verify the opportunities we compiled to create an accurate and updated resource for finding funded dermatology rotations. The program verification process was conducted by having residency program directors or their respective program coordinators mark “yes” on the spreadsheet to confirm the funded rotation is being offered by their program. Our spreadsheet will continue to be updated yearly through cooperation with participating programs to verify their funded electives and through partnership with the AAMC to include our database in their Visiting Students Resources Database that will be released each year within VLSO as applications open for the following season.

The main limitation of our review is that we presume the information provided in the VSLO and FARMS databases has not changed or been updated to include more programs since our initial search period. Additionally, the information available on dermatology residency program websites limits the data on the total programs obtained, as some website links may not be updated or may be invalid for online web user access. The benefit to creating and continually updating our Dermatology Visiting Student Health Equity and Inclusion Scholarship Database spreadsheet will be to ensure that programs regularly verify their offered funded electives and capture the true total of funded rotations offered for URiM students across the country. We also acknowledge that we did not investigate how URiM student attendance at funded rotations affected their outcomes in matching dermatology programs for residency; however, given the importance of away rotations, which positively influence the ability of URiM students to receive interviews, it is understood that these opportunities are viewed as widely beneficial.

Final Thoughts

The current online search tools that URiM students can use to find funded away rotations in dermatology exclude many of the available opportunities. We aimed to provide an updated and centralized resource for students via the shared spreadsheet we created for residency program directors, but further measures to centralize the most up-to-date information on visiting programs offering scholarships to URiM students would be beneficial.

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.05.001

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88: 941-943. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.018

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants —turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.4683

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B5. Number of active MD residents, by race/ethnicity (alone or in combination) and GME specialty. 2023-24 active residents. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2024/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. population estimates, July 1, 2024 (V2024). Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Gonzalez S, Syder N, Mckenzie SA, et al. Racial diversity in academic dermatology: a cross-sectional analysis of Black academic dermatology faculty in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:182-184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.027

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2021 NRMP Program Director Survey, 2021. August 2021. Accessed March 9, 2025. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186 /s12909-016-0805-z

Most medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States will participate in an away rotation at an outside institution. Prior to COVID-19–related restrictions, 86.7% of dermatology applicants from the class of 2020 reported completing one or more away rotations for their application cycle.1,2 This requirement can be considerably costly, especially since most programs do not offer financial support for travel, living expenses, or housing during these visiting experiences.3 Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) students may be particularly disadvantaged with regard to the financial obligations that come with away rotations.4,5 Visiting scholarships for URiM students can mitigate these challenges, creating opportunities for increasing diversity in dermatology. When medical students begin the residency application process, the Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) program of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) is the most widely used third-party service for submitting applications. For many URiM students, an unforeseen challenge when applying to dermatology residency programs is the lack of an easily accessible and up-to-date search tool to find programs that offer funding, resulting in more time spent searching and thereby complicating the application process. The VSLO released the Visiting Scholars Resources Database, a search tool that aims to compile opportunities for additional support—academic professional, and/or financial—to address this issue. Additionally, the Funded Away Rotations for Minority Medical Students (FARMS) database is an independent directory of programs that offer stipends to URiM students. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the VLSO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database search tool and the FARMS database in identifying funded dermatology rotations for URiM students.

Overview of Online Search Tools

We used the AAMC’s Electronic Residency Application Service Directory to identify 141 programs offering dermatology residency positions. We then conducted a Google search using each program name with the phrase underrepresented in medicine dermatology away rotation to identify any opportunities noted in the Google results offering scholarship funding for URiM students. If there were no Google results for a webpage discussing URiM away rotation opportunities for a certain program, the individual program’s website search box was queried using the terms URiM, scholarship, and funding. If there were no relevant results, the webpages associated with the dermatology department, away rotations, and diversity and inclusion on the respective institution’s website were reviewed to confirm no indication of funded URiM opportunities. Of the 141 dermatology programs we evaluated, we identified 56 (39.7%) that offered funded away rotations for URiM students.

For comparison, we conducted a search of the VSLO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database to identify programs that listed dermatology, all (specialties), or any (specialties) under the Specialty column that also had a financial resource for URiM students. Our search of the VSLO database yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we identified via our initial Google and program website search. Program listings tagged for dermatology also were retrieved from the FARMS database, of which only 17 (30.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we previously identified were included. All queries were performed from October 24 to October 26, 2024 (Figure).

Comment

The 2023-2024 AAMC Report on Residents indicated that 54.9% (800/1455) of active US dermatology medical residents identified as White, 27.5% (400/1455) identified as Asian, 8.9% (129/1455) identified as Hispanic, and 8.7% (126/1455) identified as Black or African American.6 By comparison, 19.5% of the general US population identifies as Hispanic and 13.7% identifies as Black.7 Within the field of dermatology, the proportion of Black dermatology academic faculty in the US is estimated to comprise only 18.7% of all active Black dermatologists.8,9 With a growing population of minority US citizens, the dermatology workforce is lagging in representation across all minority populations, especially when it comes to Hispanic and Black individuals. To increase the diversity of the US dermatology workforce, residency programs must prioritize recruitment of URiM students and support their retention as future faculty.

Reports in the literature suggest that clinical grades, US Medical Licensing Examination scores, letters of recommendation/ networking, and the risk of not matching are among the primary concerns that URiM students face as potential barriers to applying for dermatology residency.4 Meanwhile, dermatology program directors ranked diversity characteristics, perceived interest in the program, personal prior knowledge of an applicant, and audition rotation in their department as important considerations for interviewing applicants.10 As a result, URiM students may have the diverse characteristics that program directors are looking for, but obtaining away rotations and establishing mentors at other institutions may be challenging due to the burden of accruing additional costs for visiting rotations.2,10,11 Other reports have indicated that expanding funded dermatology visiting rotations and promoting national programs such as the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/awards/diversity) or the Skin of Color Society Observership Grant (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/what-we-do/mentorship/observership-grant) can be alternative routes for mentorship and networking.3

Our review demonstrated that, of the 141 dermatology residency programs we identified, only around 40% offer funded rotations for URiM students; however, the current databases that applicants use to find these opportunities do not adequately present the number of available options. A search of the VSLO database—the most widely used third-party database for applying to dermatology away rotations—yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the rotations that we identified in our initial Google search. Similarly, a search of the FARMS database yielded only 17 (30.4%) of the dermatology rotations we previously identified. Aside from missing more than half of the available funded dermatology away rotations, the search process was further complicated by the reliance of the 2 databases on user input rather than presenting all programs offering funded opportunities for dermatology applicants without the need to enter additional information. As of October 26, 2024, there were only 22 inputs for Visiting Scholars Resources across all specialties and programs in the VLSO system.

Our findings indicate a clear need for a reliable and accurate database that captures all funded dermatology rotations for prospective URiM applicants because of the strong emphasis on visiting rotations for application success. Our team created a Google spreadsheet compiling dermatology visiting student health equity and inclusion scholarships from inputs we found in our search. We shared this resource via the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve so program members could verify the opportunities we compiled to create an accurate and updated resource for finding funded dermatology rotations. The program verification process was conducted by having residency program directors or their respective program coordinators mark “yes” on the spreadsheet to confirm the funded rotation is being offered by their program. Our spreadsheet will continue to be updated yearly through cooperation with participating programs to verify their funded electives and through partnership with the AAMC to include our database in their Visiting Students Resources Database that will be released each year within VLSO as applications open for the following season.

The main limitation of our review is that we presume the information provided in the VSLO and FARMS databases has not changed or been updated to include more programs since our initial search period. Additionally, the information available on dermatology residency program websites limits the data on the total programs obtained, as some website links may not be updated or may be invalid for online web user access. The benefit to creating and continually updating our Dermatology Visiting Student Health Equity and Inclusion Scholarship Database spreadsheet will be to ensure that programs regularly verify their offered funded electives and capture the true total of funded rotations offered for URiM students across the country. We also acknowledge that we did not investigate how URiM student attendance at funded rotations affected their outcomes in matching dermatology programs for residency; however, given the importance of away rotations, which positively influence the ability of URiM students to receive interviews, it is understood that these opportunities are viewed as widely beneficial.

Final Thoughts

The current online search tools that URiM students can use to find funded away rotations in dermatology exclude many of the available opportunities. We aimed to provide an updated and centralized resource for students via the shared spreadsheet we created for residency program directors, but further measures to centralize the most up-to-date information on visiting programs offering scholarships to URiM students would be beneficial.

Most medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States will participate in an away rotation at an outside institution. Prior to COVID-19–related restrictions, 86.7% of dermatology applicants from the class of 2020 reported completing one or more away rotations for their application cycle.1,2 This requirement can be considerably costly, especially since most programs do not offer financial support for travel, living expenses, or housing during these visiting experiences.3 Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) students may be particularly disadvantaged with regard to the financial obligations that come with away rotations.4,5 Visiting scholarships for URiM students can mitigate these challenges, creating opportunities for increasing diversity in dermatology. When medical students begin the residency application process, the Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) program of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) is the most widely used third-party service for submitting applications. For many URiM students, an unforeseen challenge when applying to dermatology residency programs is the lack of an easily accessible and up-to-date search tool to find programs that offer funding, resulting in more time spent searching and thereby complicating the application process. The VSLO released the Visiting Scholars Resources Database, a search tool that aims to compile opportunities for additional support—academic professional, and/or financial—to address this issue. Additionally, the Funded Away Rotations for Minority Medical Students (FARMS) database is an independent directory of programs that offer stipends to URiM students. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the VLSO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database search tool and the FARMS database in identifying funded dermatology rotations for URiM students.

Overview of Online Search Tools

We used the AAMC’s Electronic Residency Application Service Directory to identify 141 programs offering dermatology residency positions. We then conducted a Google search using each program name with the phrase underrepresented in medicine dermatology away rotation to identify any opportunities noted in the Google results offering scholarship funding for URiM students. If there were no Google results for a webpage discussing URiM away rotation opportunities for a certain program, the individual program’s website search box was queried using the terms URiM, scholarship, and funding. If there were no relevant results, the webpages associated with the dermatology department, away rotations, and diversity and inclusion on the respective institution’s website were reviewed to confirm no indication of funded URiM opportunities. Of the 141 dermatology programs we evaluated, we identified 56 (39.7%) that offered funded away rotations for URiM students.

For comparison, we conducted a search of the VSLO’s Visiting Scholars Resources Database to identify programs that listed dermatology, all (specialties), or any (specialties) under the Specialty column that also had a financial resource for URiM students. Our search of the VSLO database yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we identified via our initial Google and program website search. Program listings tagged for dermatology also were retrieved from the FARMS database, of which only 17 (30.4%) of the 56 funded away rotations we previously identified were included. All queries were performed from October 24 to October 26, 2024 (Figure).

Comment

The 2023-2024 AAMC Report on Residents indicated that 54.9% (800/1455) of active US dermatology medical residents identified as White, 27.5% (400/1455) identified as Asian, 8.9% (129/1455) identified as Hispanic, and 8.7% (126/1455) identified as Black or African American.6 By comparison, 19.5% of the general US population identifies as Hispanic and 13.7% identifies as Black.7 Within the field of dermatology, the proportion of Black dermatology academic faculty in the US is estimated to comprise only 18.7% of all active Black dermatologists.8,9 With a growing population of minority US citizens, the dermatology workforce is lagging in representation across all minority populations, especially when it comes to Hispanic and Black individuals. To increase the diversity of the US dermatology workforce, residency programs must prioritize recruitment of URiM students and support their retention as future faculty.

Reports in the literature suggest that clinical grades, US Medical Licensing Examination scores, letters of recommendation/ networking, and the risk of not matching are among the primary concerns that URiM students face as potential barriers to applying for dermatology residency.4 Meanwhile, dermatology program directors ranked diversity characteristics, perceived interest in the program, personal prior knowledge of an applicant, and audition rotation in their department as important considerations for interviewing applicants.10 As a result, URiM students may have the diverse characteristics that program directors are looking for, but obtaining away rotations and establishing mentors at other institutions may be challenging due to the burden of accruing additional costs for visiting rotations.2,10,11 Other reports have indicated that expanding funded dermatology visiting rotations and promoting national programs such as the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Mentorship Program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/awards/diversity) or the Skin of Color Society Observership Grant (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/what-we-do/mentorship/observership-grant) can be alternative routes for mentorship and networking.3

Our review demonstrated that, of the 141 dermatology residency programs we identified, only around 40% offer funded rotations for URiM students; however, the current databases that applicants use to find these opportunities do not adequately present the number of available options. A search of the VSLO database—the most widely used third-party database for applying to dermatology away rotations—yielded only 12 (21.4%) of the rotations that we identified in our initial Google search. Similarly, a search of the FARMS database yielded only 17 (30.4%) of the dermatology rotations we previously identified. Aside from missing more than half of the available funded dermatology away rotations, the search process was further complicated by the reliance of the 2 databases on user input rather than presenting all programs offering funded opportunities for dermatology applicants without the need to enter additional information. As of October 26, 2024, there were only 22 inputs for Visiting Scholars Resources across all specialties and programs in the VLSO system.

Our findings indicate a clear need for a reliable and accurate database that captures all funded dermatology rotations for prospective URiM applicants because of the strong emphasis on visiting rotations for application success. Our team created a Google spreadsheet compiling dermatology visiting student health equity and inclusion scholarships from inputs we found in our search. We shared this resource via the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve so program members could verify the opportunities we compiled to create an accurate and updated resource for finding funded dermatology rotations. The program verification process was conducted by having residency program directors or their respective program coordinators mark “yes” on the spreadsheet to confirm the funded rotation is being offered by their program. Our spreadsheet will continue to be updated yearly through cooperation with participating programs to verify their funded electives and through partnership with the AAMC to include our database in their Visiting Students Resources Database that will be released each year within VLSO as applications open for the following season.

The main limitation of our review is that we presume the information provided in the VSLO and FARMS databases has not changed or been updated to include more programs since our initial search period. Additionally, the information available on dermatology residency program websites limits the data on the total programs obtained, as some website links may not be updated or may be invalid for online web user access. The benefit to creating and continually updating our Dermatology Visiting Student Health Equity and Inclusion Scholarship Database spreadsheet will be to ensure that programs regularly verify their offered funded electives and capture the true total of funded rotations offered for URiM students across the country. We also acknowledge that we did not investigate how URiM student attendance at funded rotations affected their outcomes in matching dermatology programs for residency; however, given the importance of away rotations, which positively influence the ability of URiM students to receive interviews, it is understood that these opportunities are viewed as widely beneficial.

Final Thoughts

The current online search tools that URiM students can use to find funded away rotations in dermatology exclude many of the available opportunities. We aimed to provide an updated and centralized resource for students via the shared spreadsheet we created for residency program directors, but further measures to centralize the most up-to-date information on visiting programs offering scholarships to URiM students would be beneficial.

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.05.001

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88: 941-943. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.018

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants —turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.4683

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B5. Number of active MD residents, by race/ethnicity (alone or in combination) and GME specialty. 2023-24 active residents. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2024/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. population estimates, July 1, 2024 (V2024). Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Gonzalez S, Syder N, Mckenzie SA, et al. Racial diversity in academic dermatology: a cross-sectional analysis of Black academic dermatology faculty in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:182-184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.027

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2021 NRMP Program Director Survey, 2021. August 2021. Accessed March 9, 2025. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186 /s12909-016-0805-z

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.05.001

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88: 941-943. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.018

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants —turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.4683

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B5. Number of active MD residents, by race/ethnicity (alone or in combination) and GME specialty. 2023-24 active residents. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2024/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. population estimates, July 1, 2024 (V2024). Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Gonzalez S, Syder N, Mckenzie SA, et al. Racial diversity in academic dermatology: a cross-sectional analysis of Black academic dermatology faculty in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:182-184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.027

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2021 NRMP Program Director Survey, 2021. August 2021. Accessed March 9, 2025. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186 /s12909-016-0805-z

A Review of Online Search Tools to Identify Funded Dermatology Away Rotations for Underrepresented Medical Students

A Review of Online Search Tools to Identify Funded Dermatology Away Rotations for Underrepresented Medical Students

PRACTICE POINTS

- Many funded away rotations are not listed on the most widely used databases for applying to dermatology residency programs.

- Underrepresented in medicine students who are seeking funded dermatology away rotations would benefit from a centralized, comprehensive, and well-organized database to improve equity of opportunity in the dermatology rotation application search process and further diversify the specialty.

- There are limited data assessing outcomes associated with participation in funded rotation and residency match outcomes.

Gottron Papules Mimicking Dermatomyositis: An Unusual Manifestation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

Practice Points

- Gottron-like papules can be a dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- When present along with other findings of lupus erythematosus without any clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis, Gottron-like papules can be thought of as a manifestation of lupus erythematosus rather than dermatomyositis.