User login

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

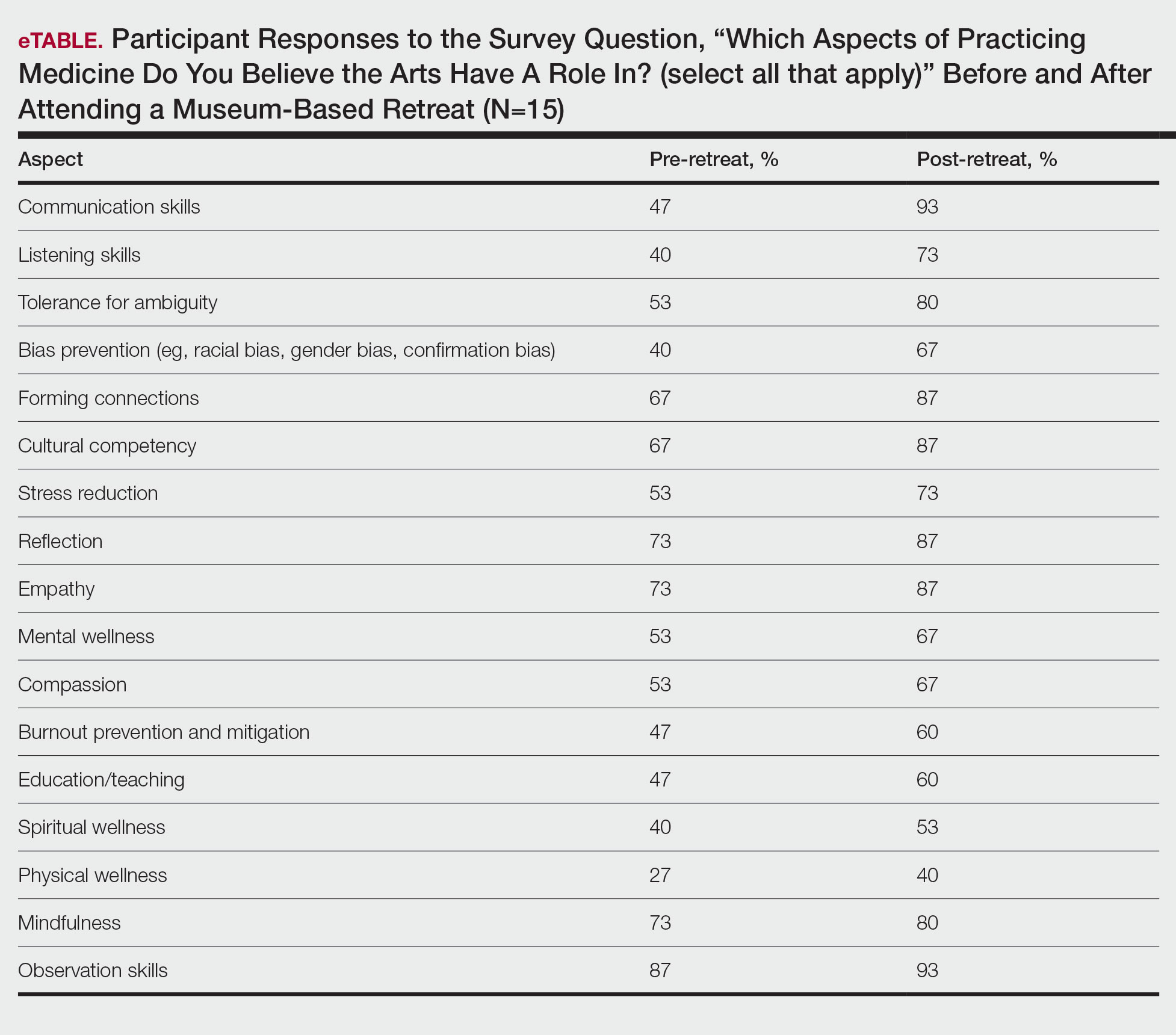

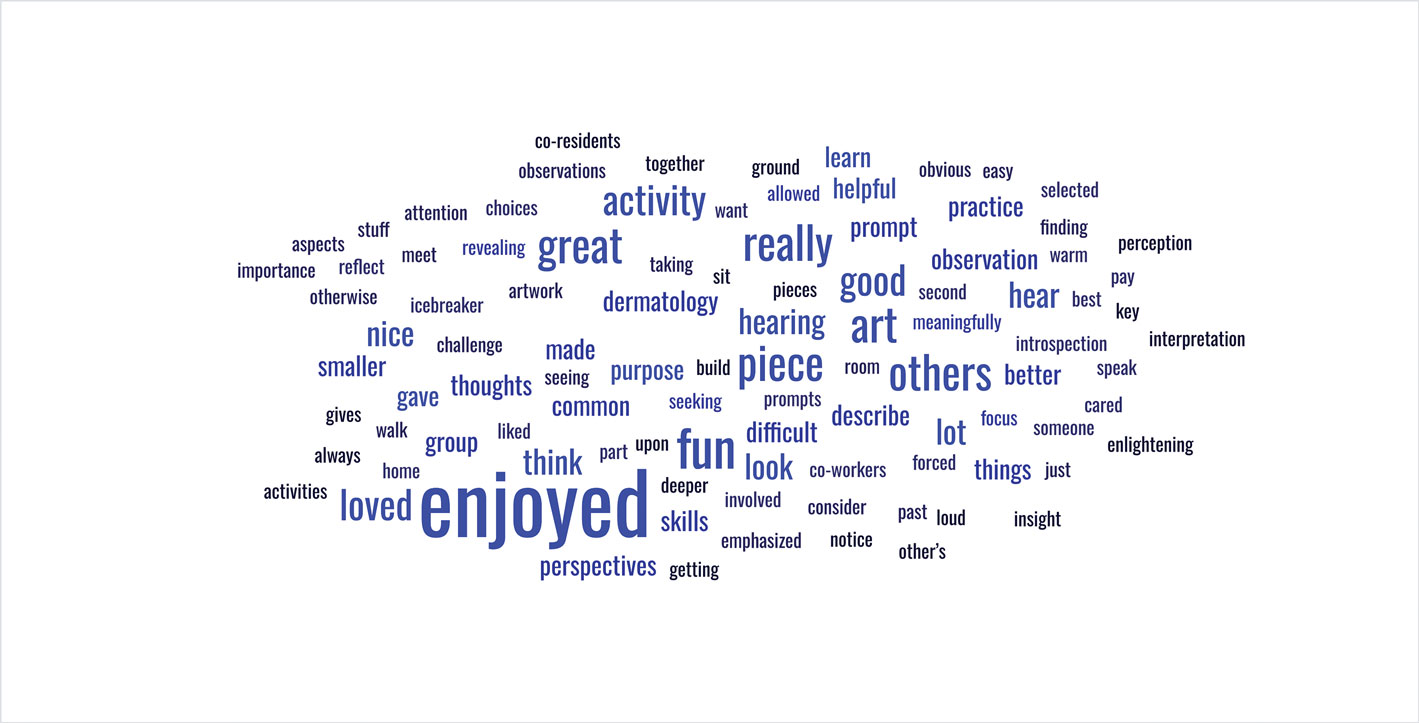

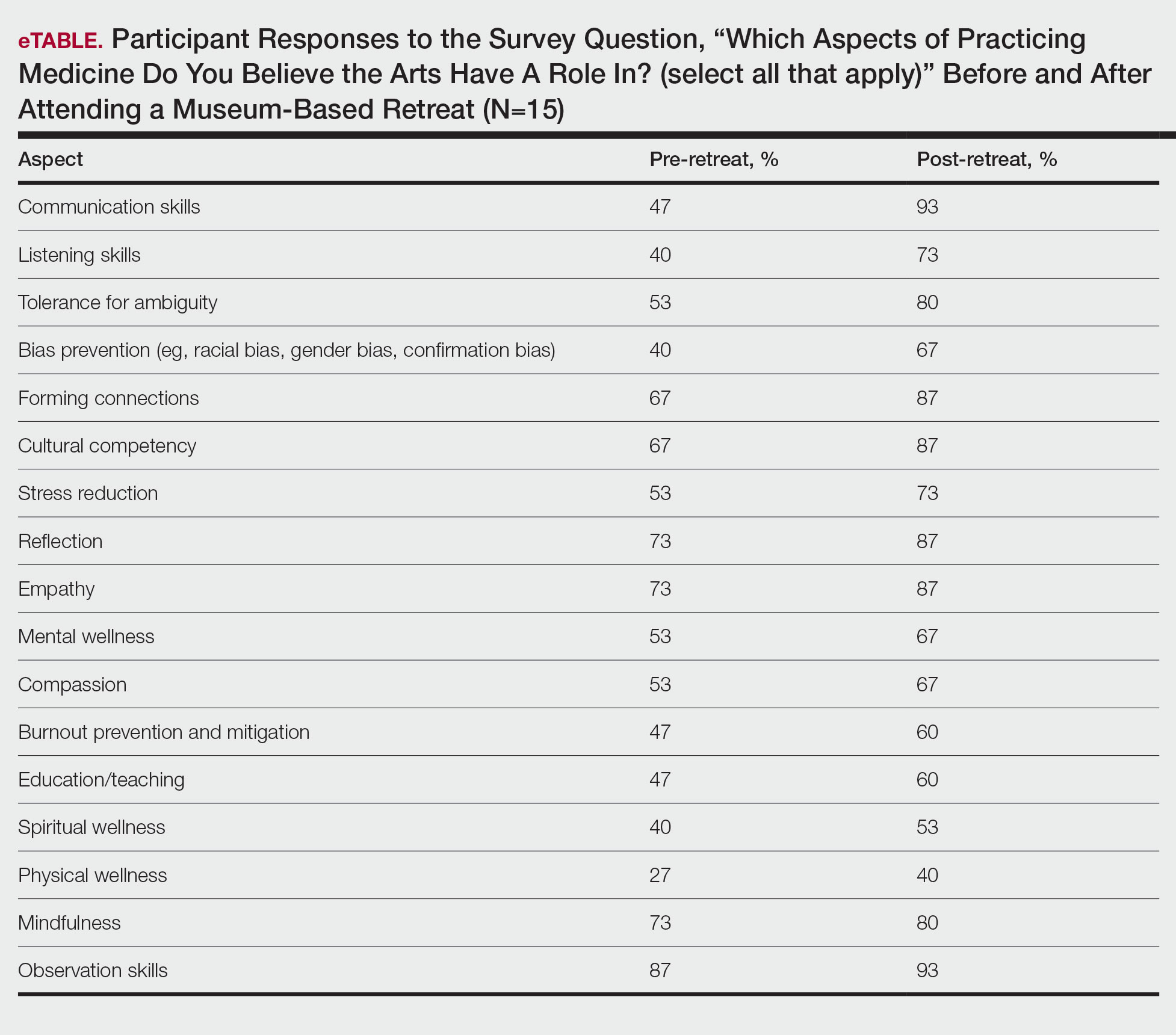

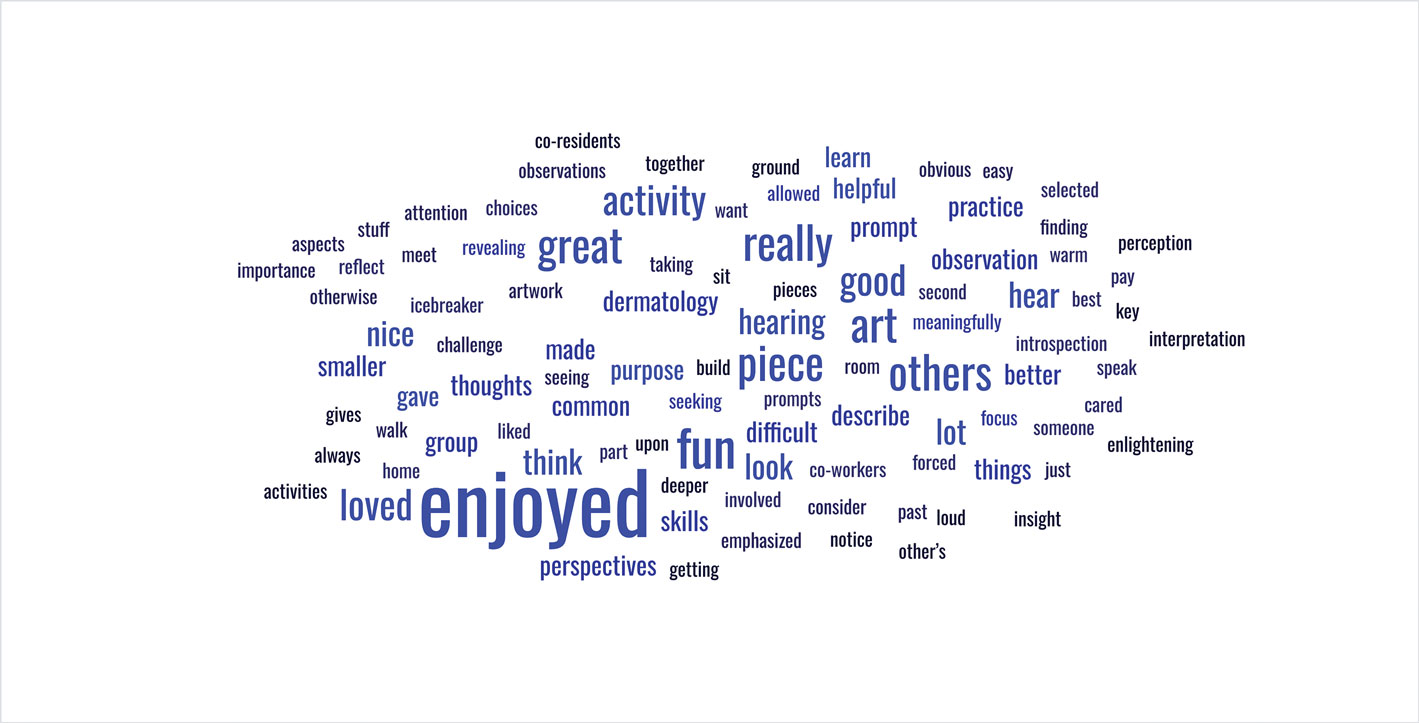

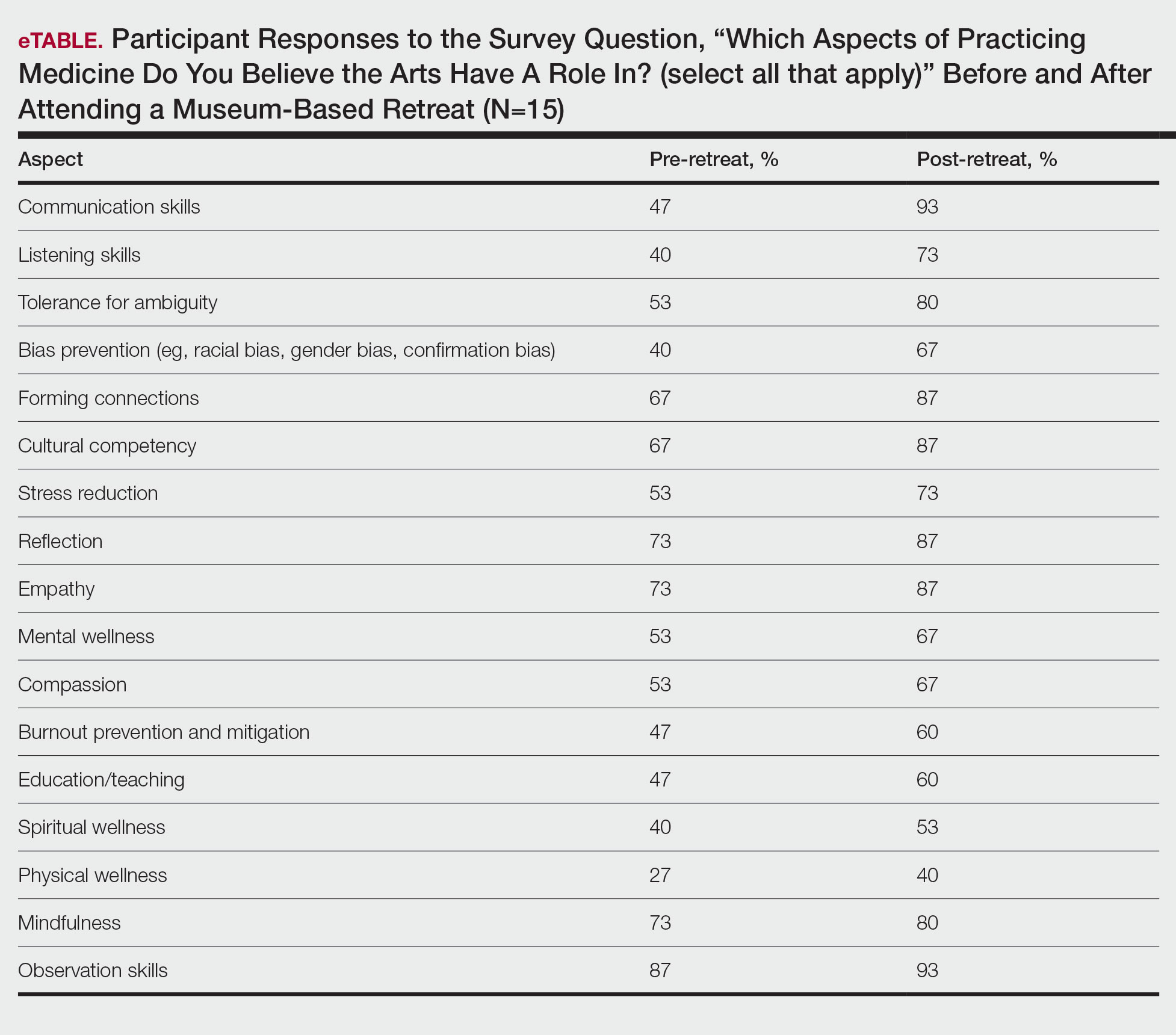

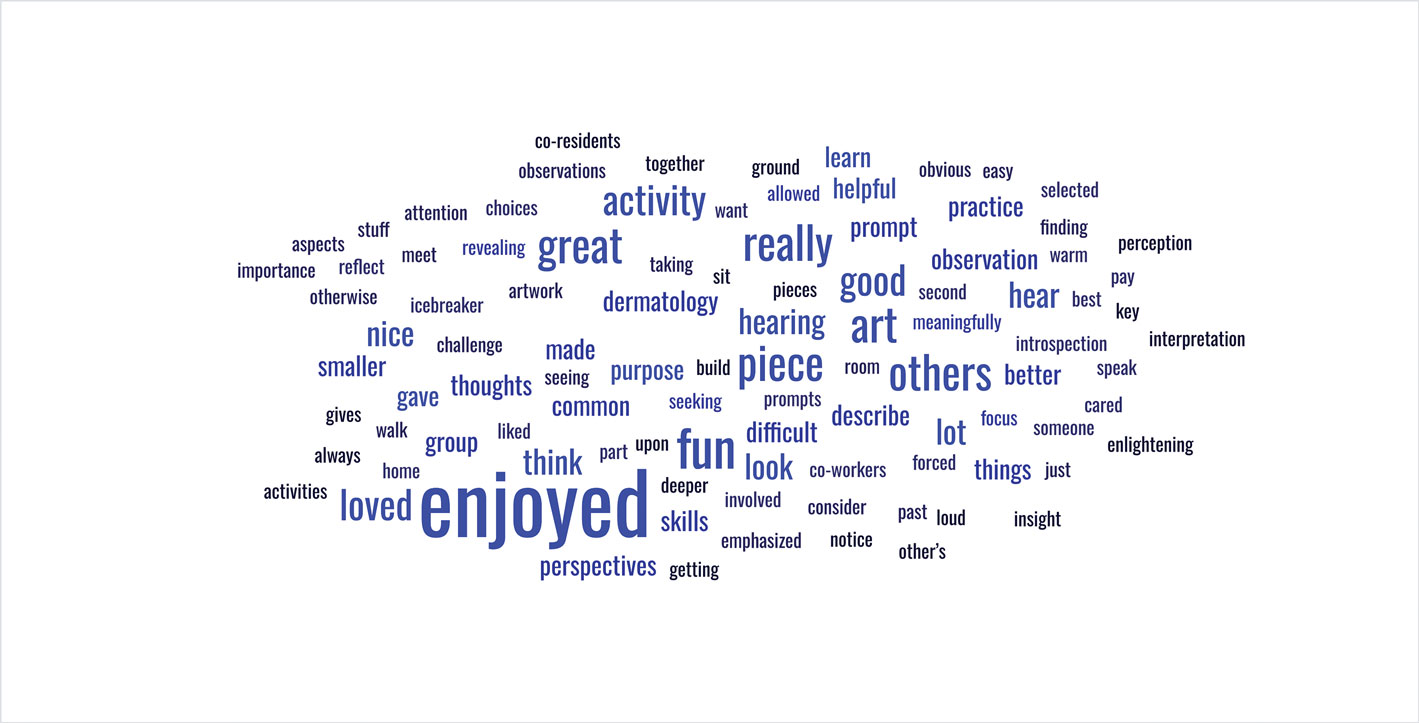

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Practice Points

- Arts-based programming positively impacts resident competencies that are important to the practice of medicine.

- Incorporating arts-based programming in the dermatology residency curriculum can enhance resident well-being and the ability to be better clinicians.

How Increasing Research Demands Threaten Equity in Dermatology Residency Selection and Strategies for Reform

How Increasing Research Demands Threaten Equity in Dermatology Residency Selection and Strategies for Reform

As one of the most competitive specialties in medicine, dermatology presents unique challenges for residency applicants, especially following the shift in United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 scoring to a pass/fail format.1,2 Historically, USMLE Step 1 served as a major screening metric for residency programs, with 90% of program directors in 2020 using USMLE Step 1 scores as a primary factor when deciding whether to invite applicants for interviews.1 However, the recent transition to pass/fail has made it much harder for program directors to objectively compare applicants, particularly in dermatology. In a 2020 survey, Patrinely Jr et al2 found that 77.2% of dermatology program directors agreed that this change would make it more difficult to assess candidates objectively. Consequently, research productivity has taken on greater importance as programs seek new ways to distinguish top applicants.1,2

In response to this increased emphasis on research, dermatology applicants have substantially boosted their scholarly output over the past several years. The 2022 and 2024 results from the National Residency Matching Program’s Charting Outcomes survey demonstrated a steady rise in research metrics among applicants across various specialties, with dermatology showing one of the largest increases.3,4 For instance, the average number of abstracts, presentations, and publications for matched allopathic dermatology applicants was 5.7 in 2007.5 This average increased to 20.9 in 20223 and to 27.7 in 2024,4 marking an astonishing 485% increase in 17 years. Interestingly, unmatched dermatology applicants had an average of 19.0 research products in 2024, which was similar to the average of successfully matched applicants just 2 years earlier.3,4

Engaging in research offers benefits beyond building a strong residency application. Specifically, it enhances critical thinking skills and provides hands-on experience in scientific inquiry.6 It allows students to explore dermatology topics of interest and address existing knowledge gaps within the specialty.6 Additionally, it creates opportunities to build meaningful relationships with experienced dermatologists who can guide and support students throughout their careers.7 Despite these benefits, the pursuit of research may be landscaped with obstacles, and the fervent race to obtain high research outputs may overshadow developmental advantages.8 These challenges and demands also could contribute to inequities in the residency selection process, particularly if barriers are influenced by socioeconomic and demographic disparities. As dermatology already ranks as the second least diverse specialty in medicine,9 research requirements that disproportionately disadvantage certain demographic groups risk further widening these concerning representation gaps rather than creating opportunities to address them.

Given these trends in research requirements and their potential impact on applicant success, understanding specific barriers to research engagement is essential for creating equitable opportunities in dermatology. In this study, we aimed to identify barriers to research engagement among dermatology applicants, analyze their relationship with demographic factors, assess their impact on specialty choice and research productivity, and provide actionable solutions to address these obstacles.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted targeting medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States in the 2025 or 2026 match cycles as well as residents who applied to dermatology residency in the 2021 to 2024 match cycles. The 23-item survey was developed by adapting questions from several validated studies examining research barriers and experiences in medical education.6,7,10,11 Specifically, the survey included questions on demographics and background; research productivity; general research barriers; conference participation accessibility; mentorship access; and quality, career impact, and support needs. Socioeconomic background was measured via a single self-reported item asking participants to select the income class that best reflected their background growing up (low-income, lower-middle, upper-middle, or high-income); no income ranges were provided.

The survey was distributed electronically via Qualtrics between November 11, 2024, and December 30, 2024, through listserves of the Dermatology Interest Group Association (sent directly to medical students) and the Association of Professors of Dermatology (forwarded to residents by program directors). There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants and residents reached through either listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional review board (IRB-300013671).

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio (Posit, PBC; version 2024.12.0+467). Descriptive statistics characterized participant demographics and quantified barrier scores using frequencies and proportions. We performed regression analyses to examine relationships between demographic factors and barriers using linear regression; the relationship between barriers and research productivity correlation; and the prediction of specialty change consideration using logistic regression. For all analyses, barrier scores were rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=not a barrier, 1=minor barrier, 2=moderate barrier, 3=major barrier); R² values were reported to indicate strength of associations, and statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

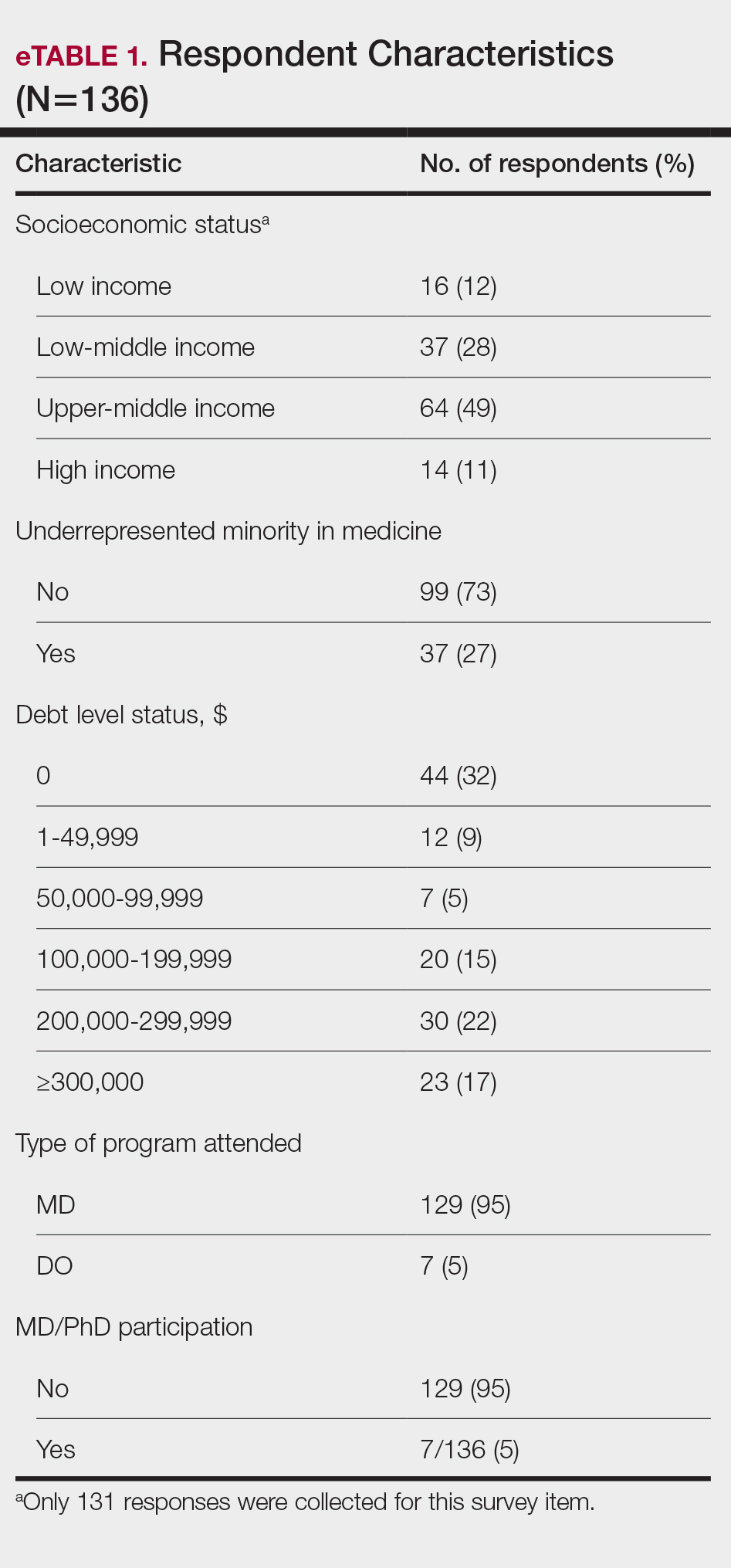

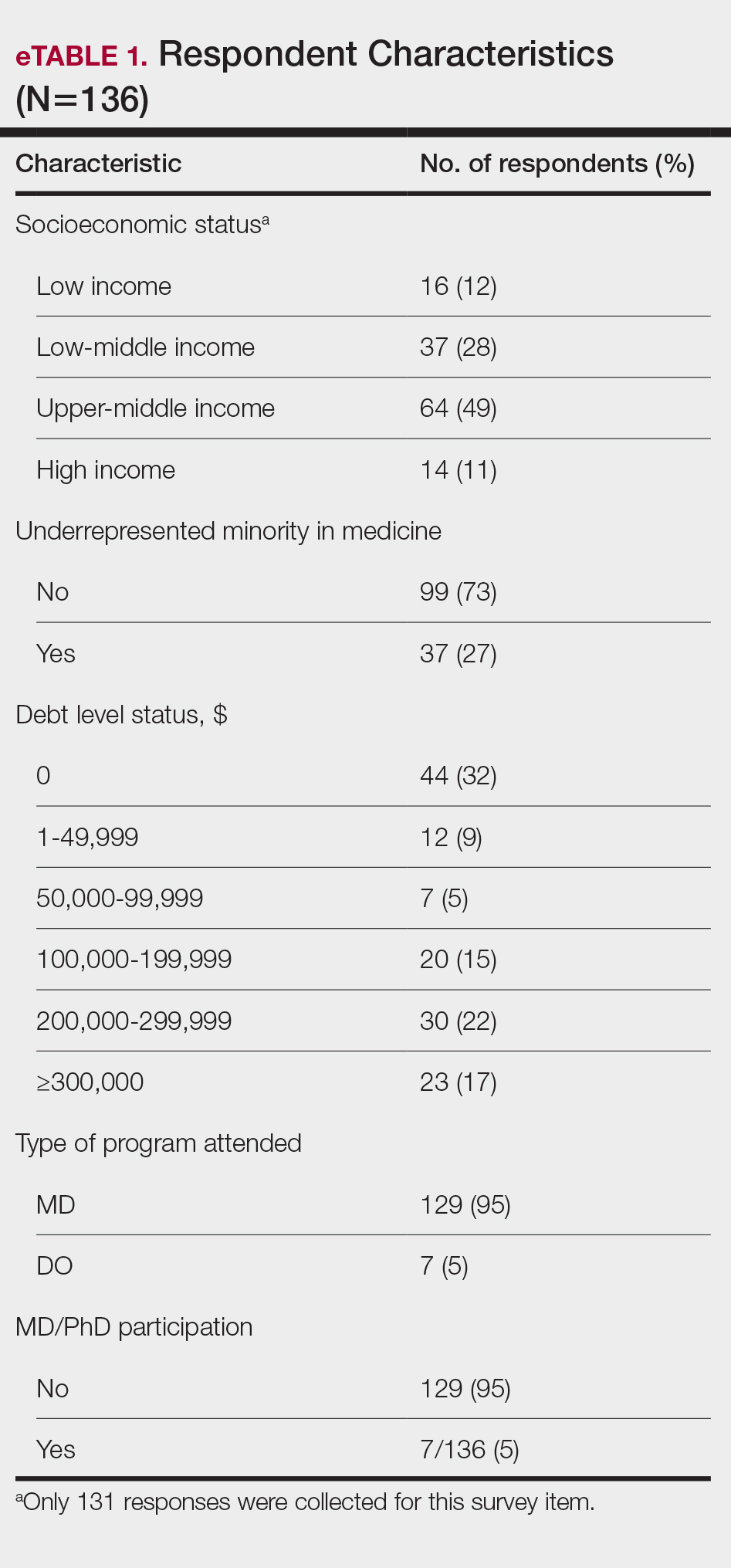

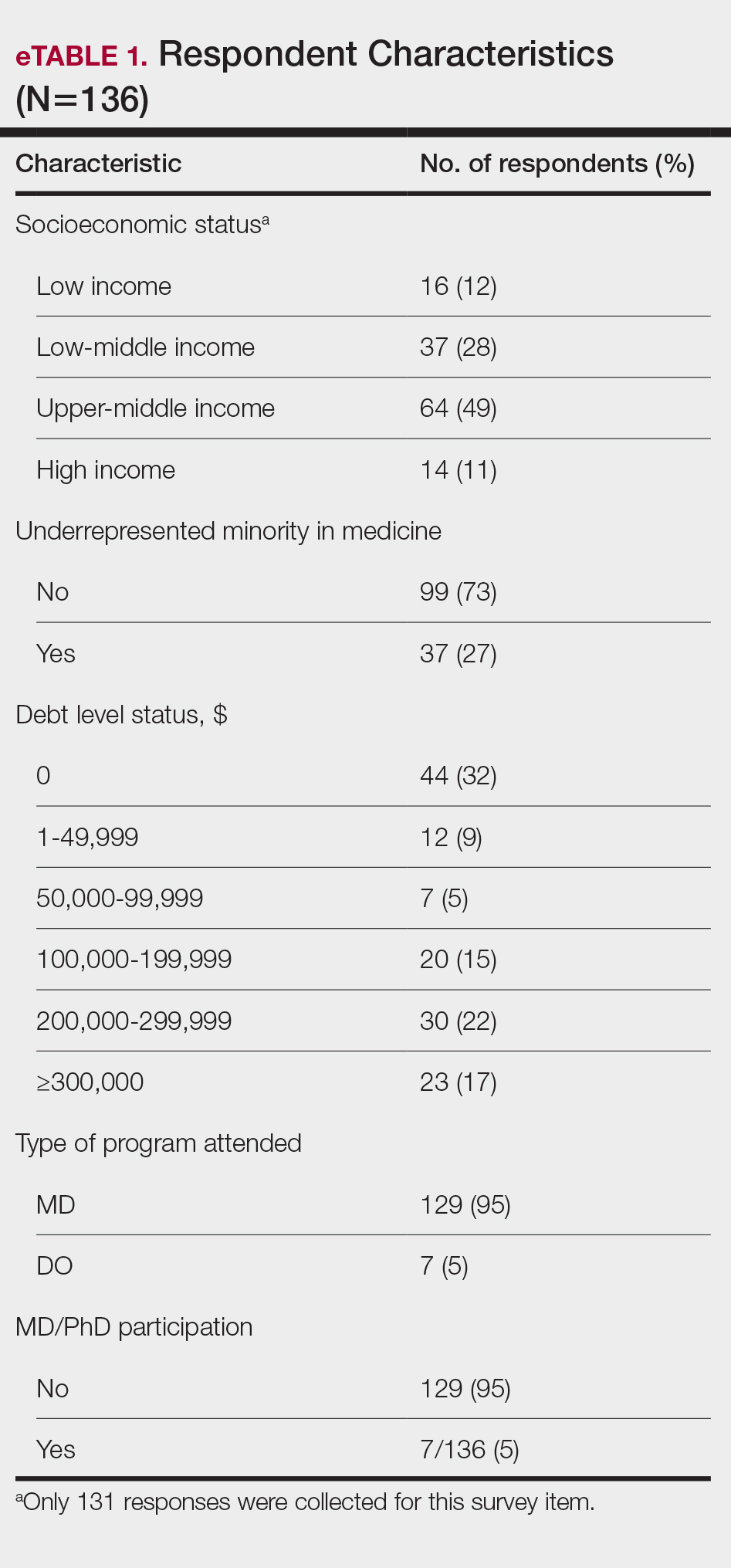

Participant Demographics—A total of 136 participants completed the survey. Among the respondents, 12% identified as from a background of low-income class, 28% lower-middle class, 49% upper-middle class, and 11% high-income class. Additionally, 27% of respondents identified as underrepresented in medicine (URiM). Regarding debt levels (or expected debt levels) upon graduation from medical school, 32% reported no debt, 9% reported $1000 to $49,000 in debt, 5% reported $50,000 to $99,000 in debt, 15% reported $100,000 to $199,000 in debt, 22% reported $200,000 to $299,000 in debt, and 17% reported $300,000 in debt or higher. The majority of respondents (95%) were MD candidates, and the remaining 5% were DO candidates; additionally, 5% were participants in an MD/PhD program (eTable 1).

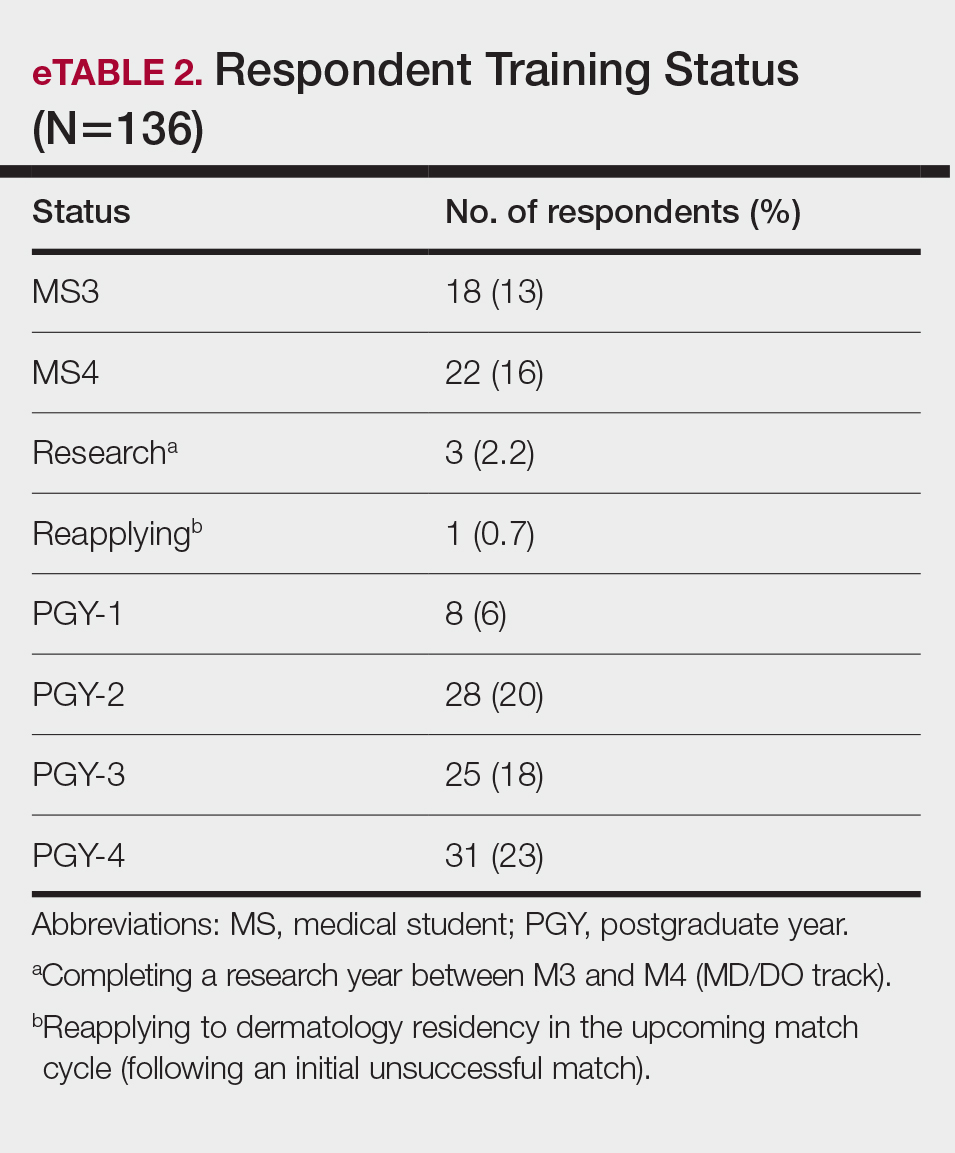

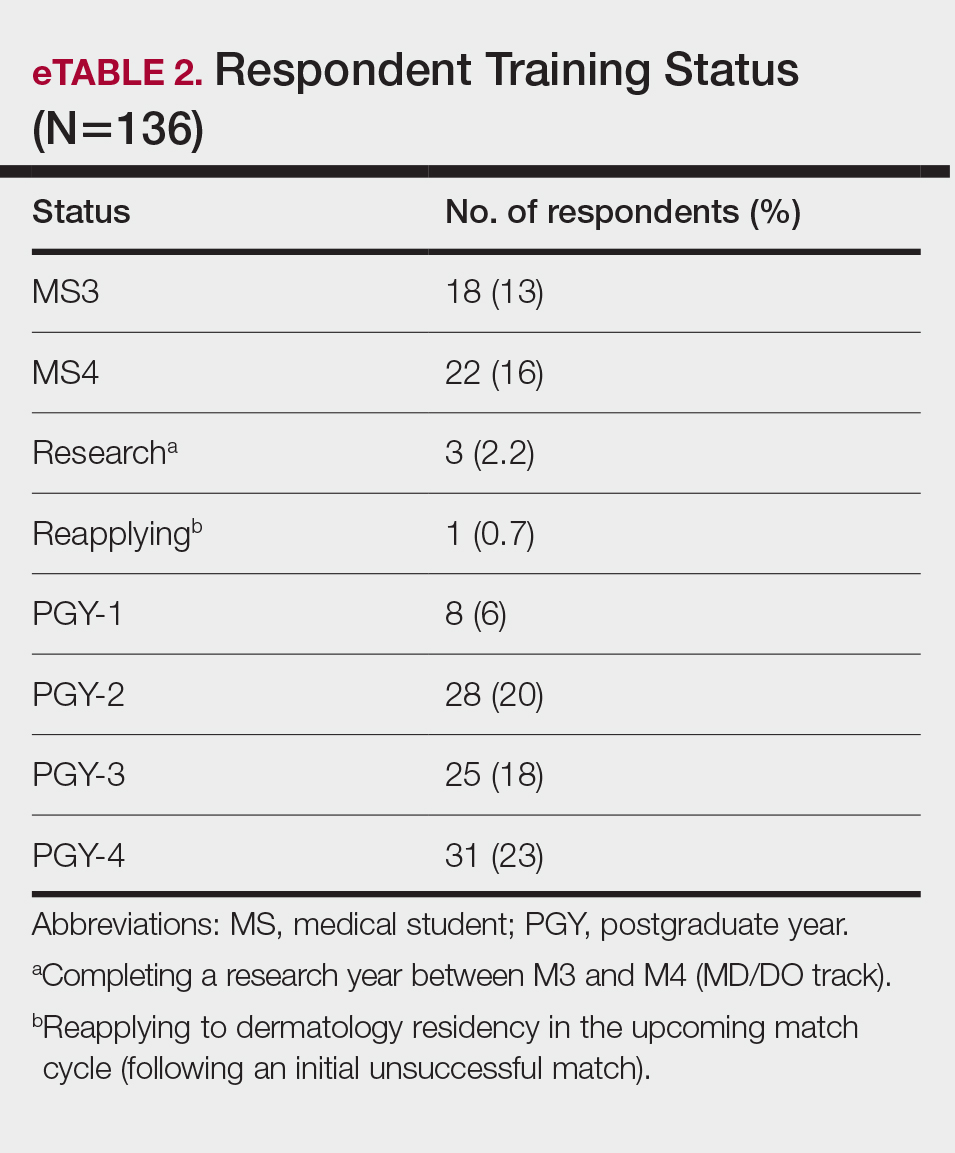

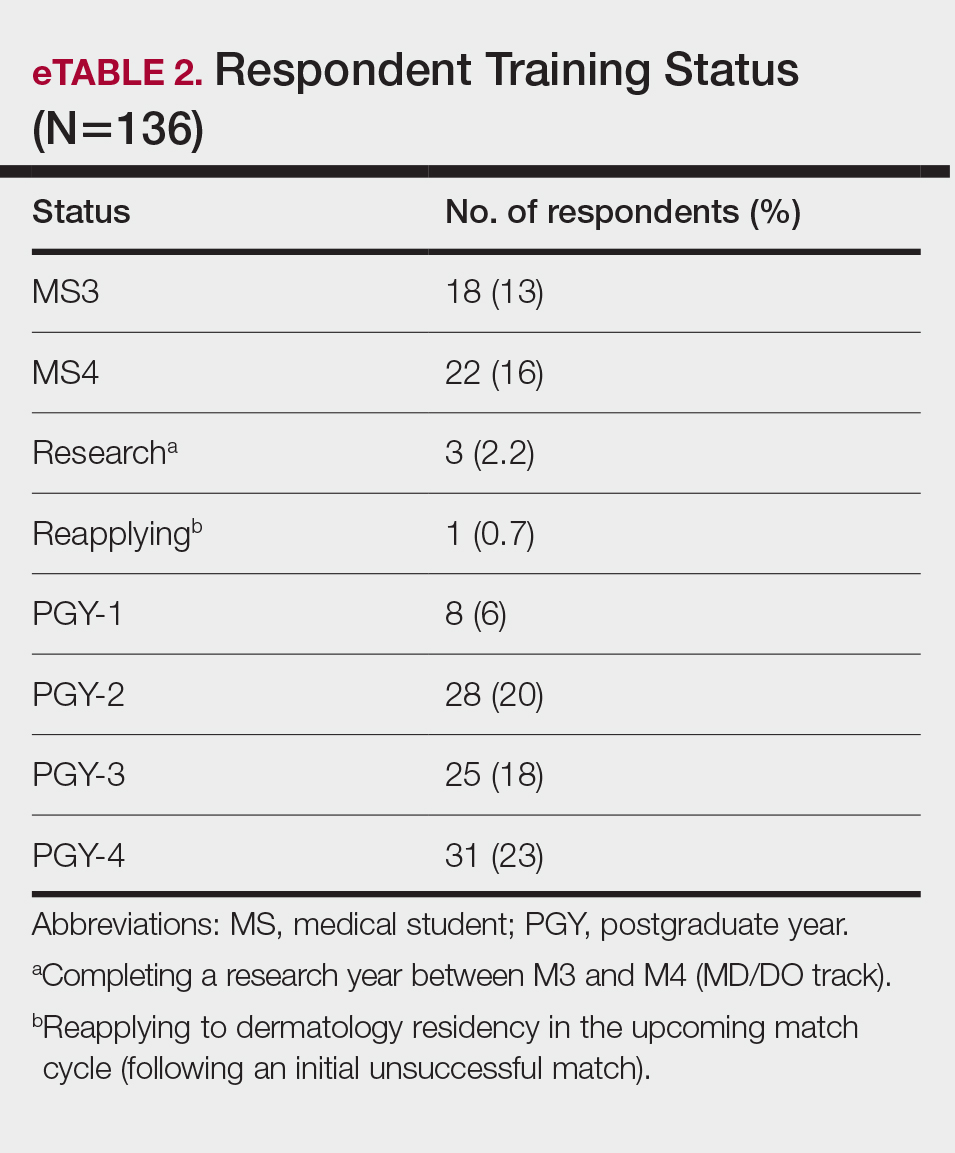

Respondents represented various stages of training: 13.2% and 16.2% were third- and fourth-year medical students, respectively, while 6.0%, 20.1%, 18.4%, and 22.8% were postgraduate year (PGY) 1, PGY-2, PGY-3, and PGY-4, respectively. A few respondents (2.9%) were participating in a research year or reapplying to dermatology residency (eTable 2).

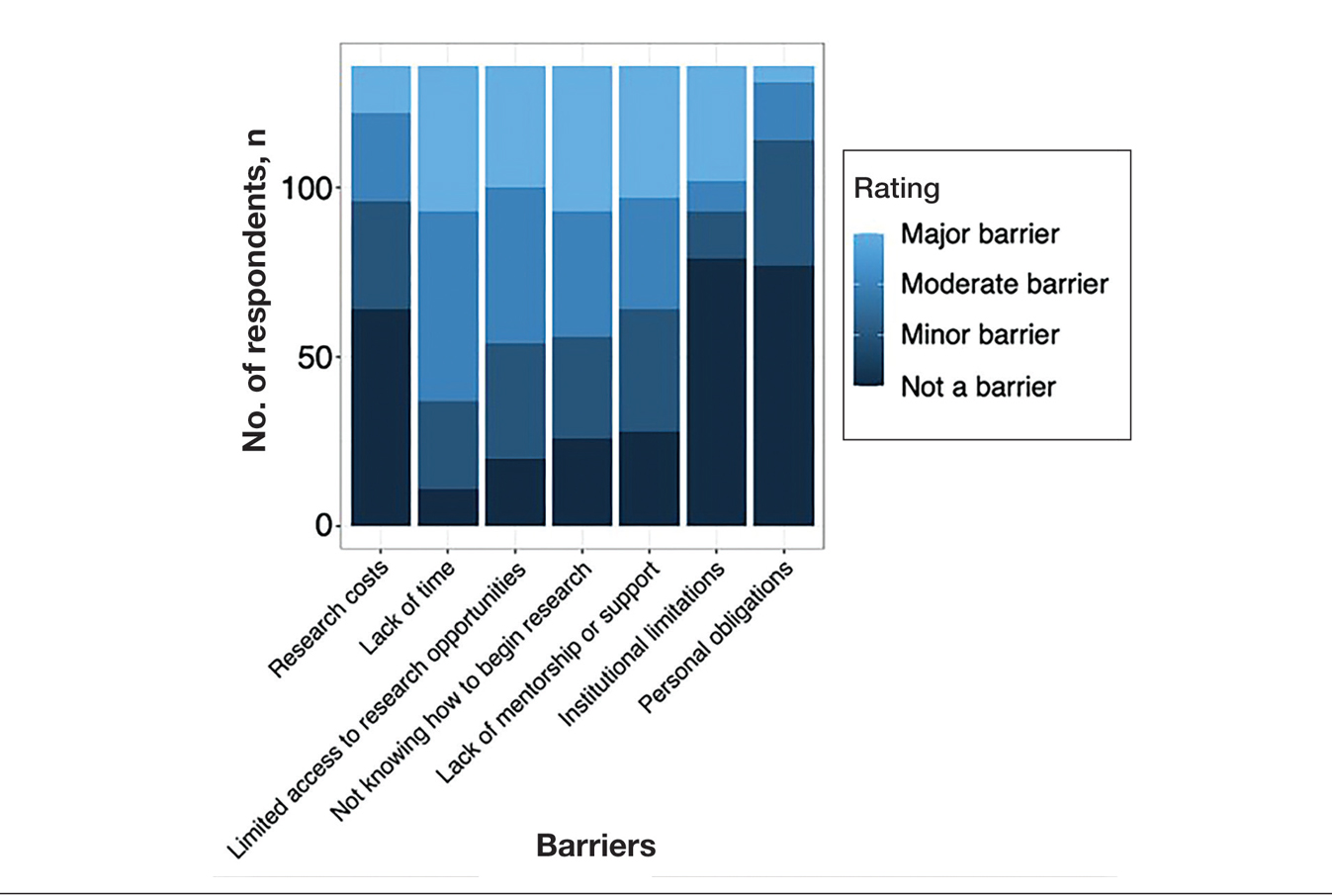

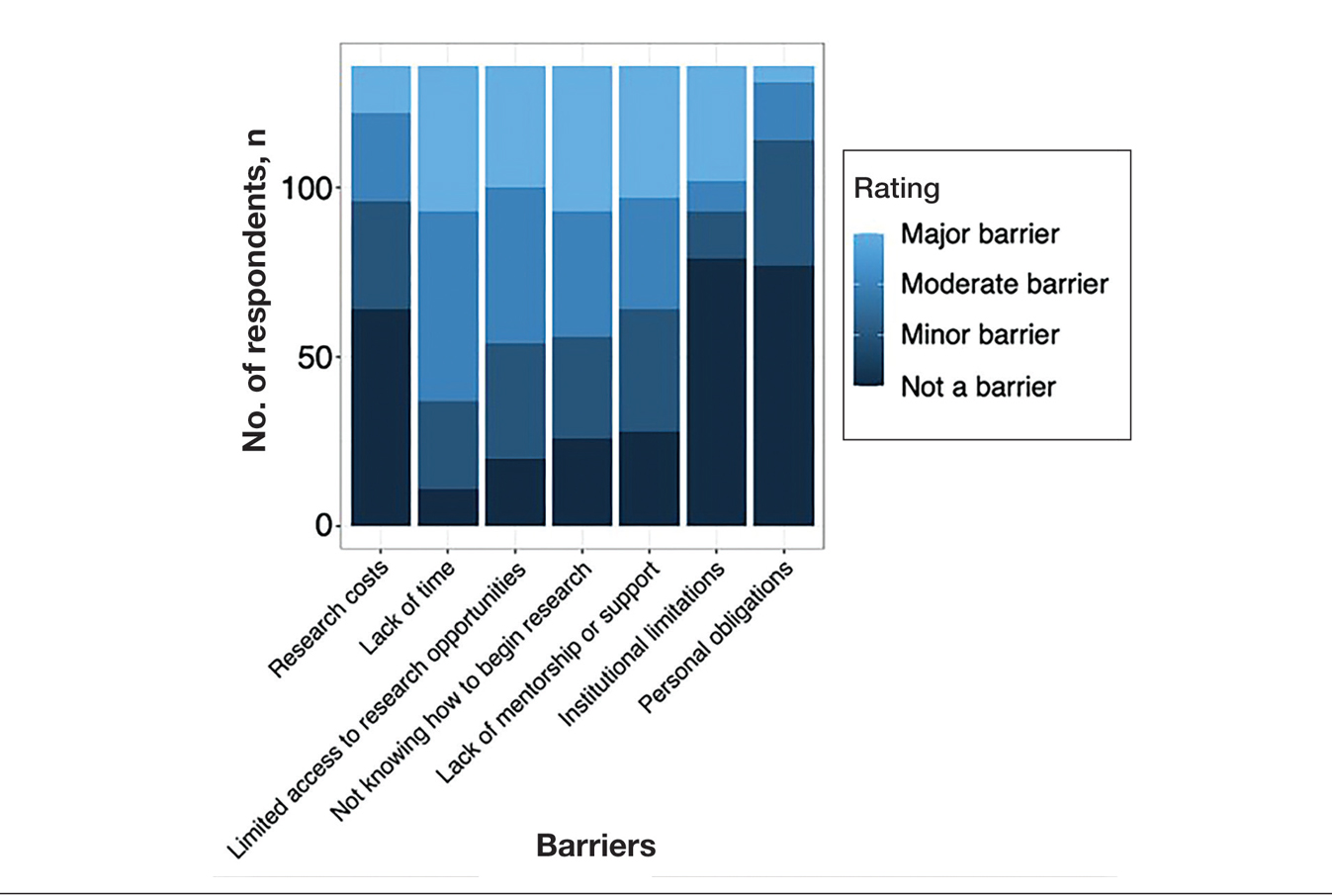

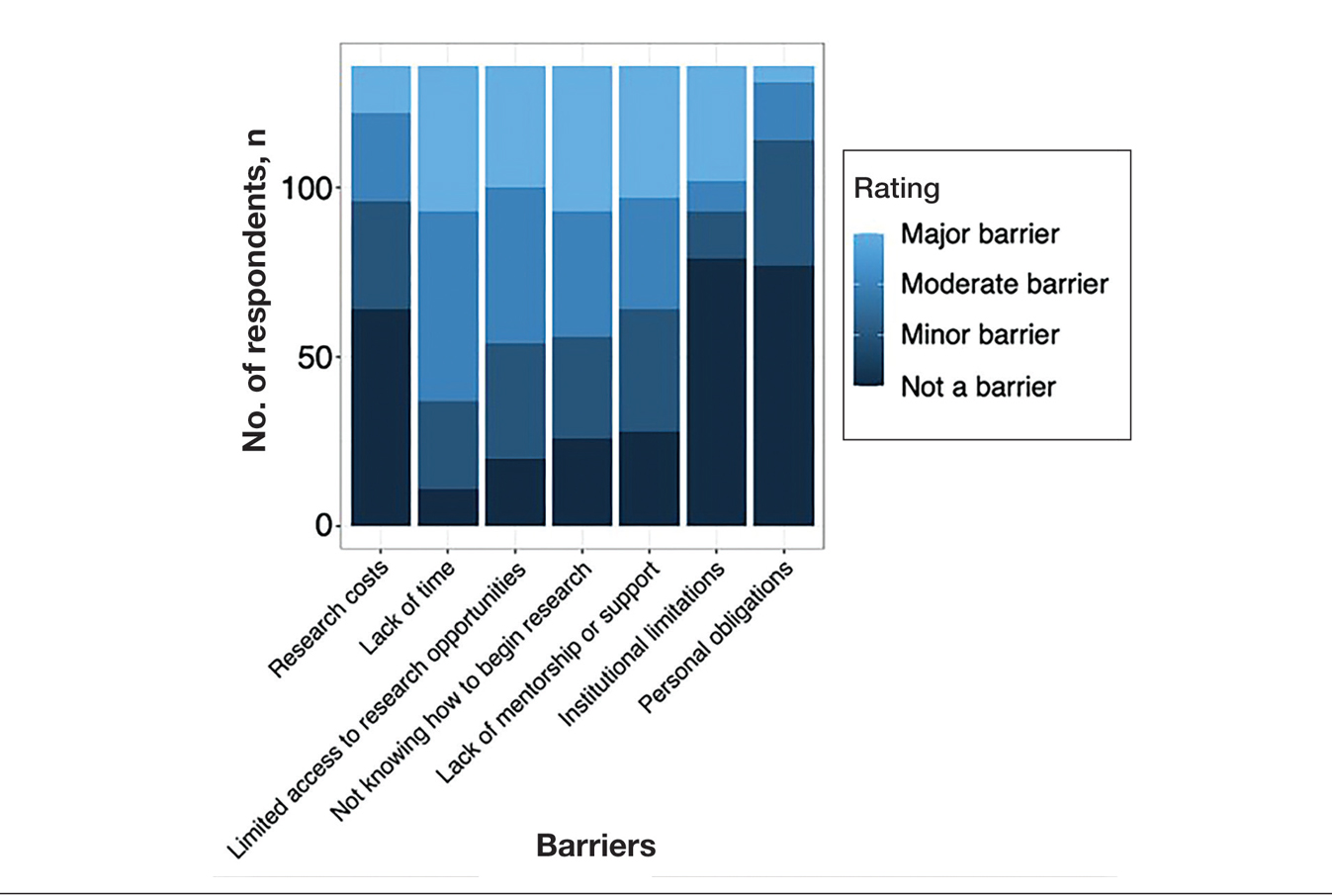

Research Barriers and Productivity—Respondents were presented with a list of potential barriers and asked to rate each as not a barrier, a minor barrier, a moderate barrier, or a major barrier. The most common barriers (ie, those with >50% of respondents rating them as a moderate or major) included lack of time, limited access to research opportunities, not knowing how to begin research, and lack of mentorship or support. Lack of time and not knowing where to begin research were reported most frequently as major barriers, with 32% of participants identifying them as such. In contrast, barriers such as financial costs and personal obligations were less frequently rated as major barriers (10% and 4%, respectively), although they still were identified as obstacles by many respondents. Interestingly, most respondents (58%) indicated that institutional limitations were not a barrier, but a separate and sizeable proportion (25%) of respondents considered it to be a major barrier (eFigure 1).

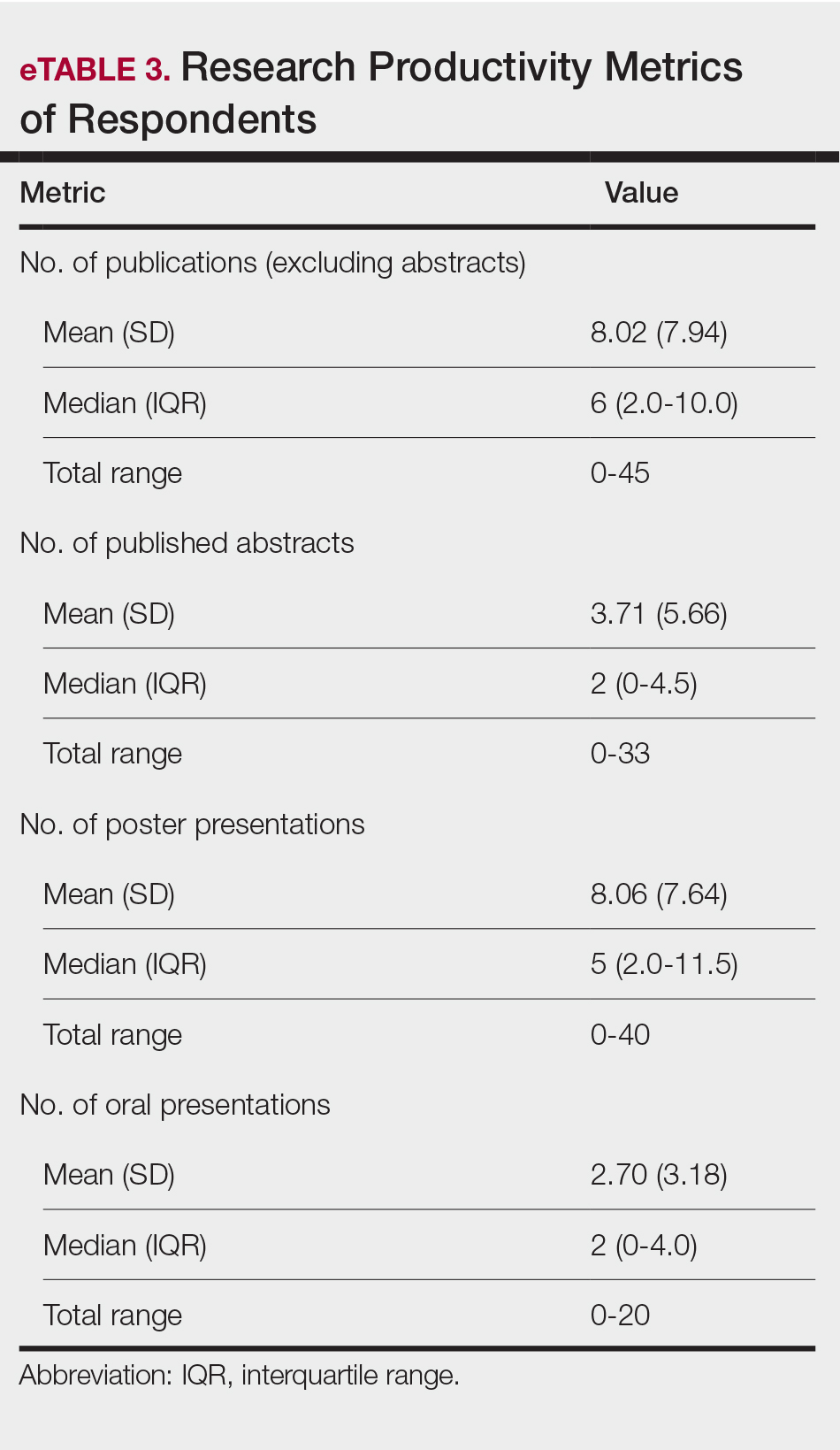

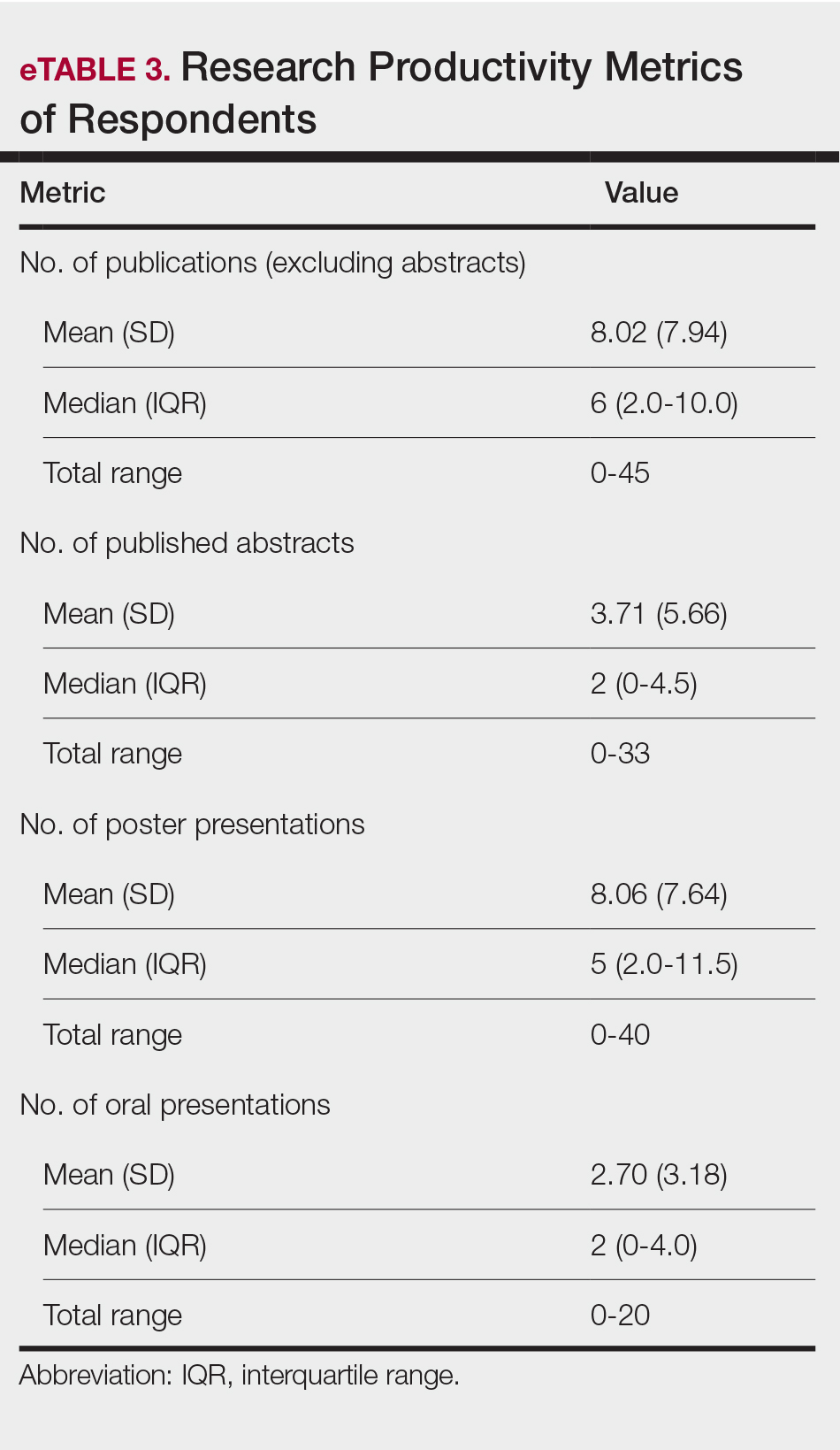

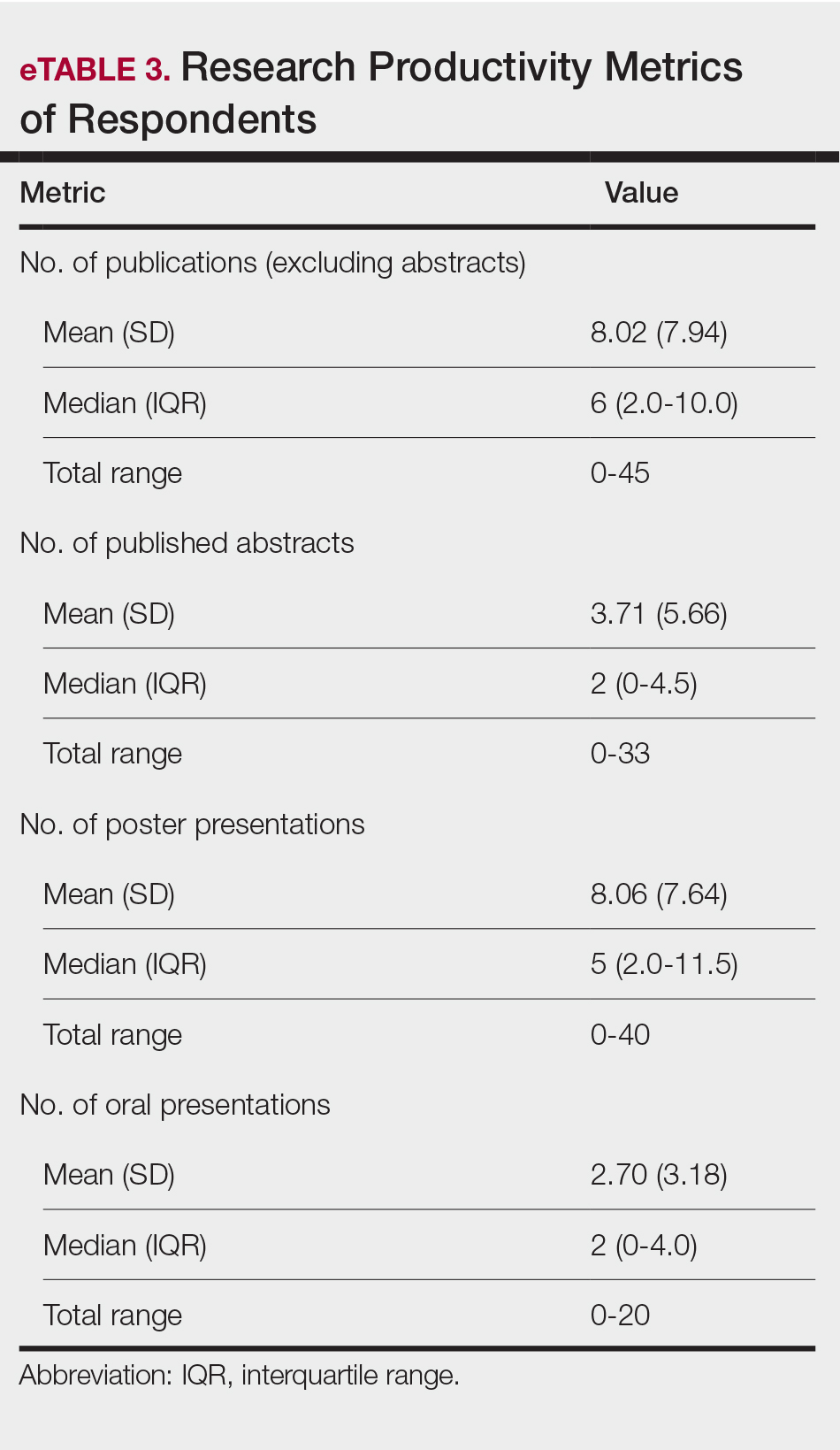

The distributions for all research metrics were right-skewed. The total range was 0 to 45 (median, 6) for number of publications (excluding abstracts), 0 to 33 (median, 2) for published abstracts, 0 to 40 (median, 5) for poster publications, and 0 to 20 (median, 2) for oral presentations (eTable 3).

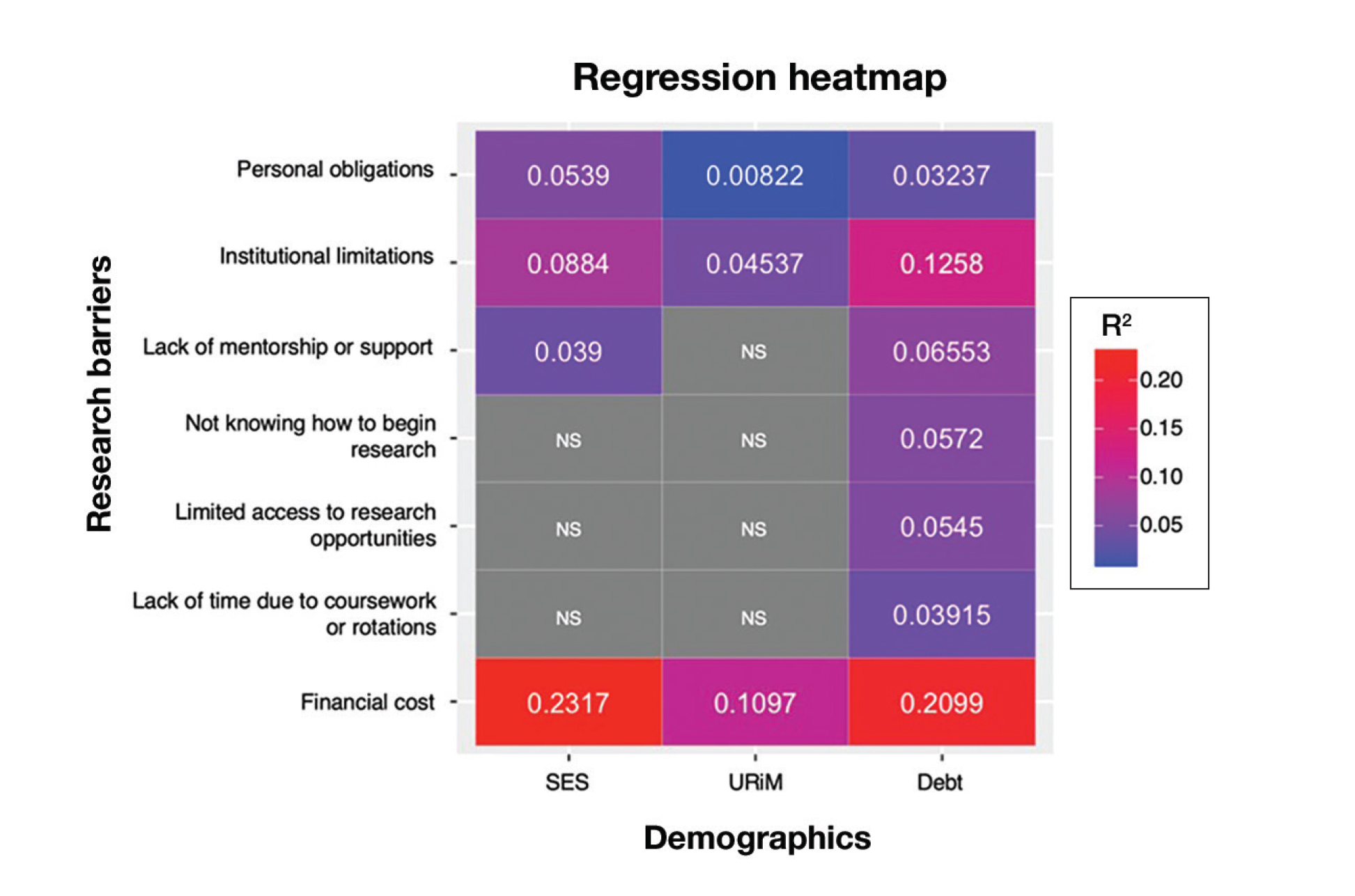

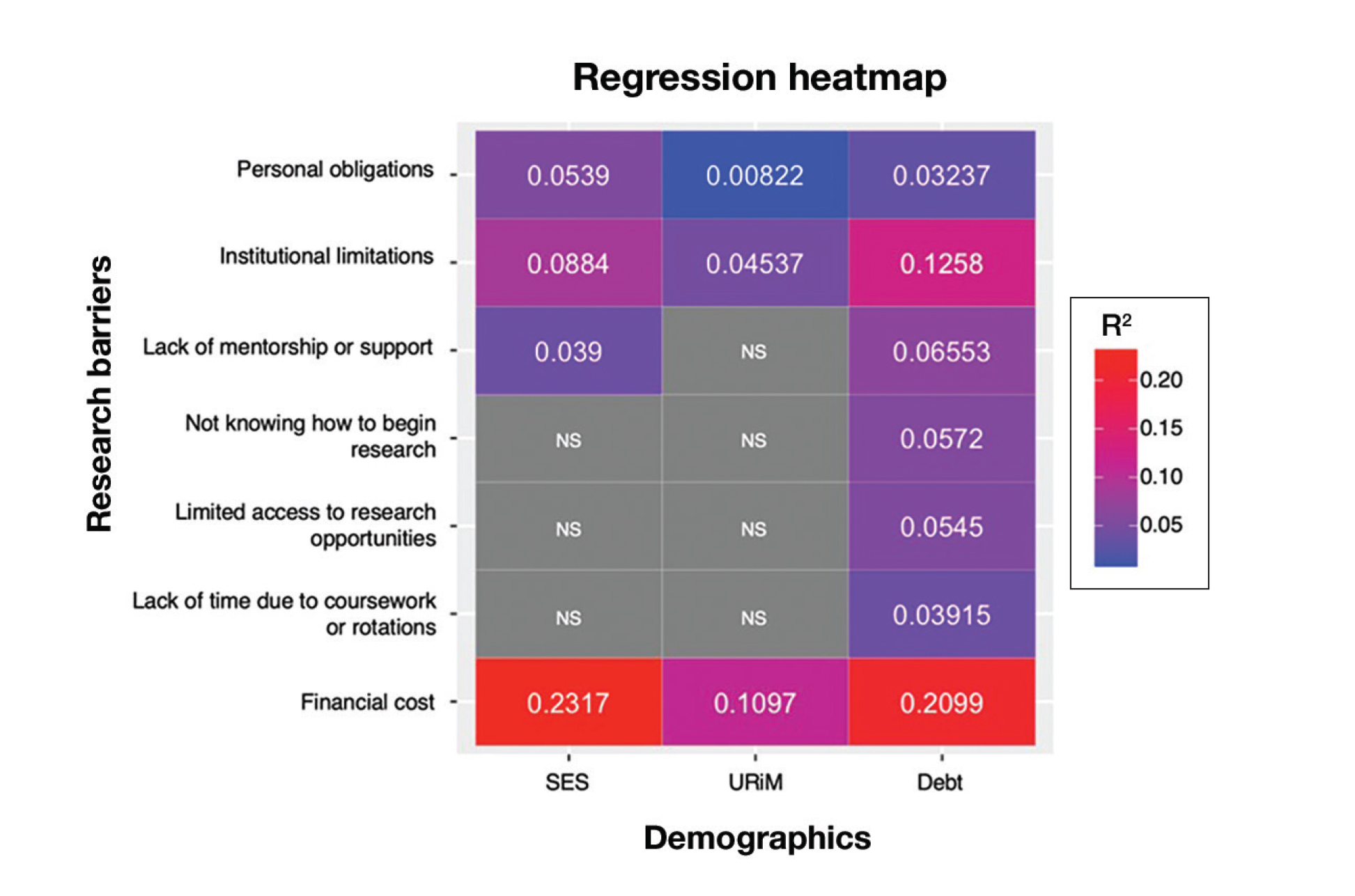

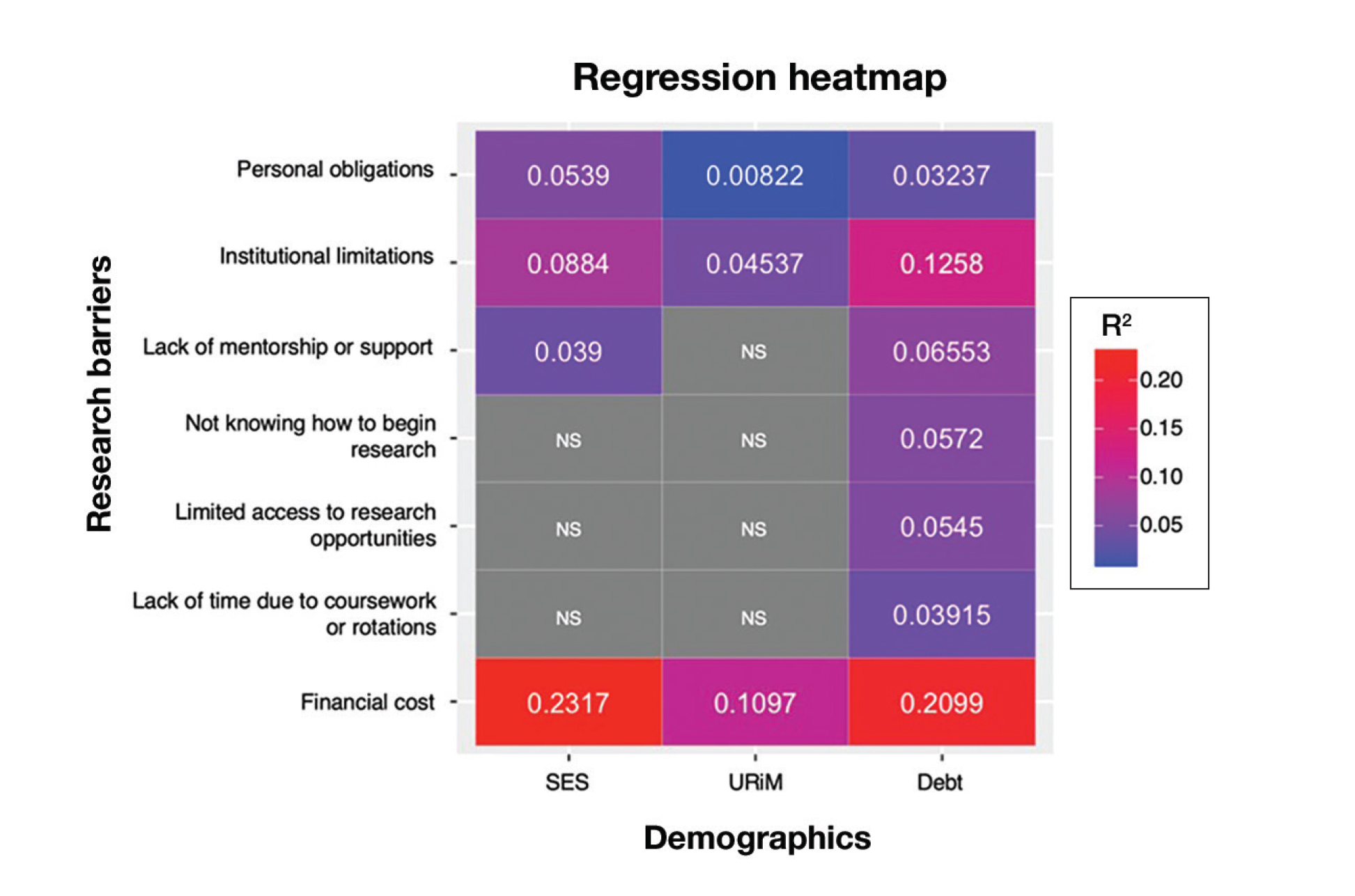

Regression Analysis—Linear regression analysis identified significant relationships between demographic variables (socioeconomic status [SES], URiM status, and debt level) and individual research barriers. The heatmap in eFigure 2 illustrates the strength of these relationships. Higher SES was predictive of lower reported financial barriers (R²=.2317; P<.0001) and lower reported institutional limitations (R²=.0884; P=.0006). A URiM status predicted higher reported financial barriers (R²=.1097; P<.0001) and institutional limitations (R²=.04537; P=.013). Also, higher debt level predicted increased financial barriers (R²=.2099; P<.0001), institutional limitations (R2=.1258; P<.0001), and lack of mentorship (R²=.06553; P=.003).

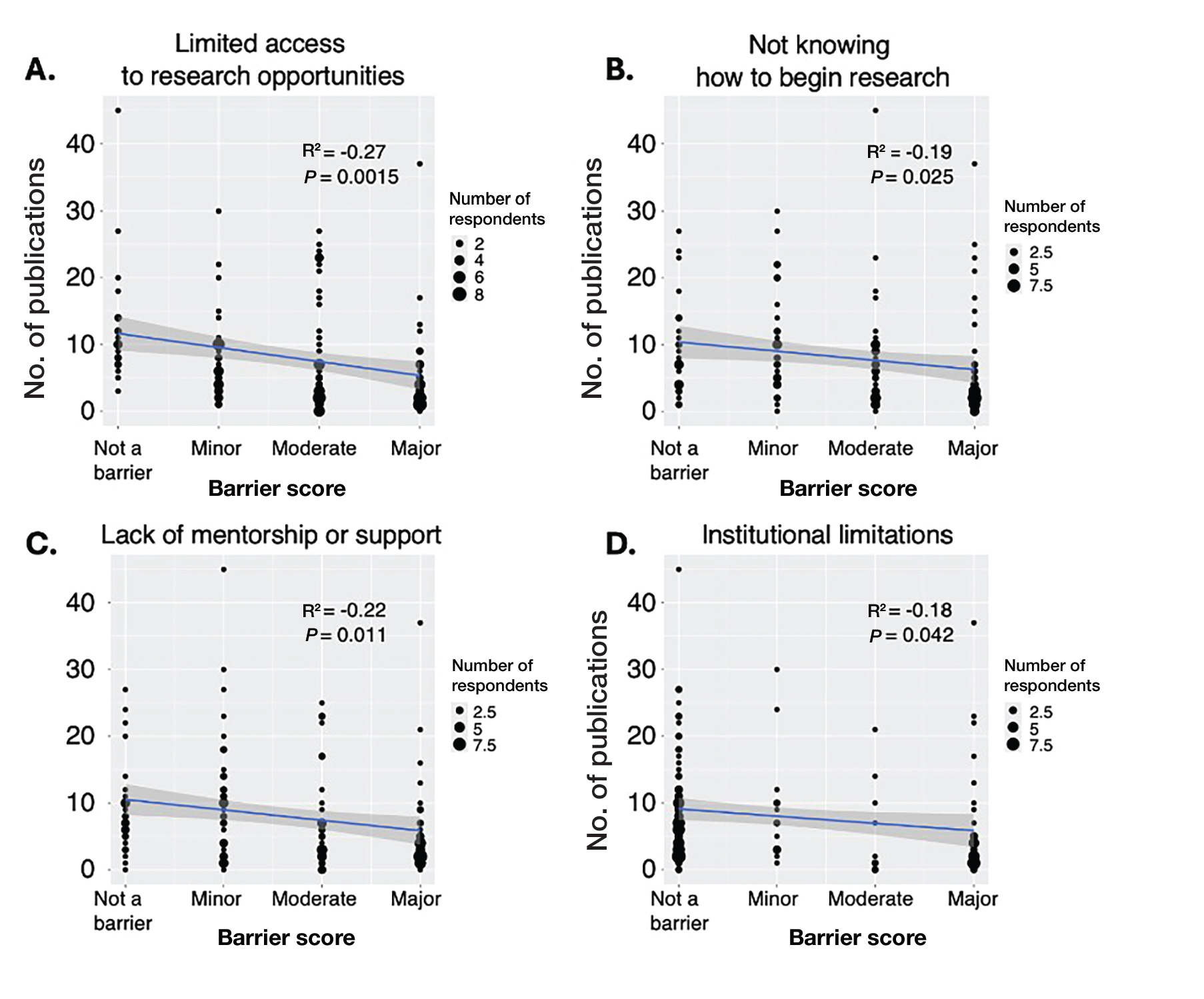

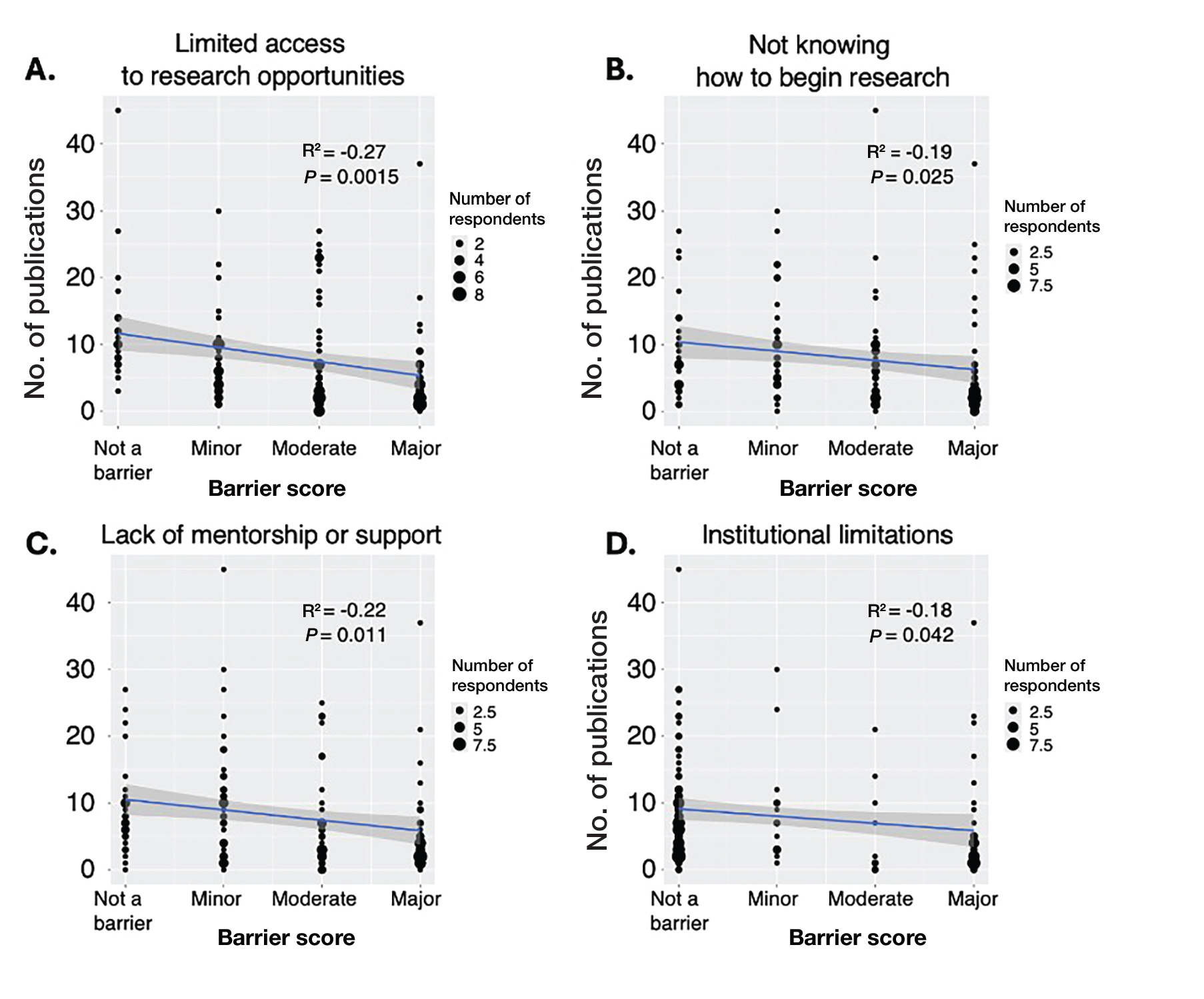

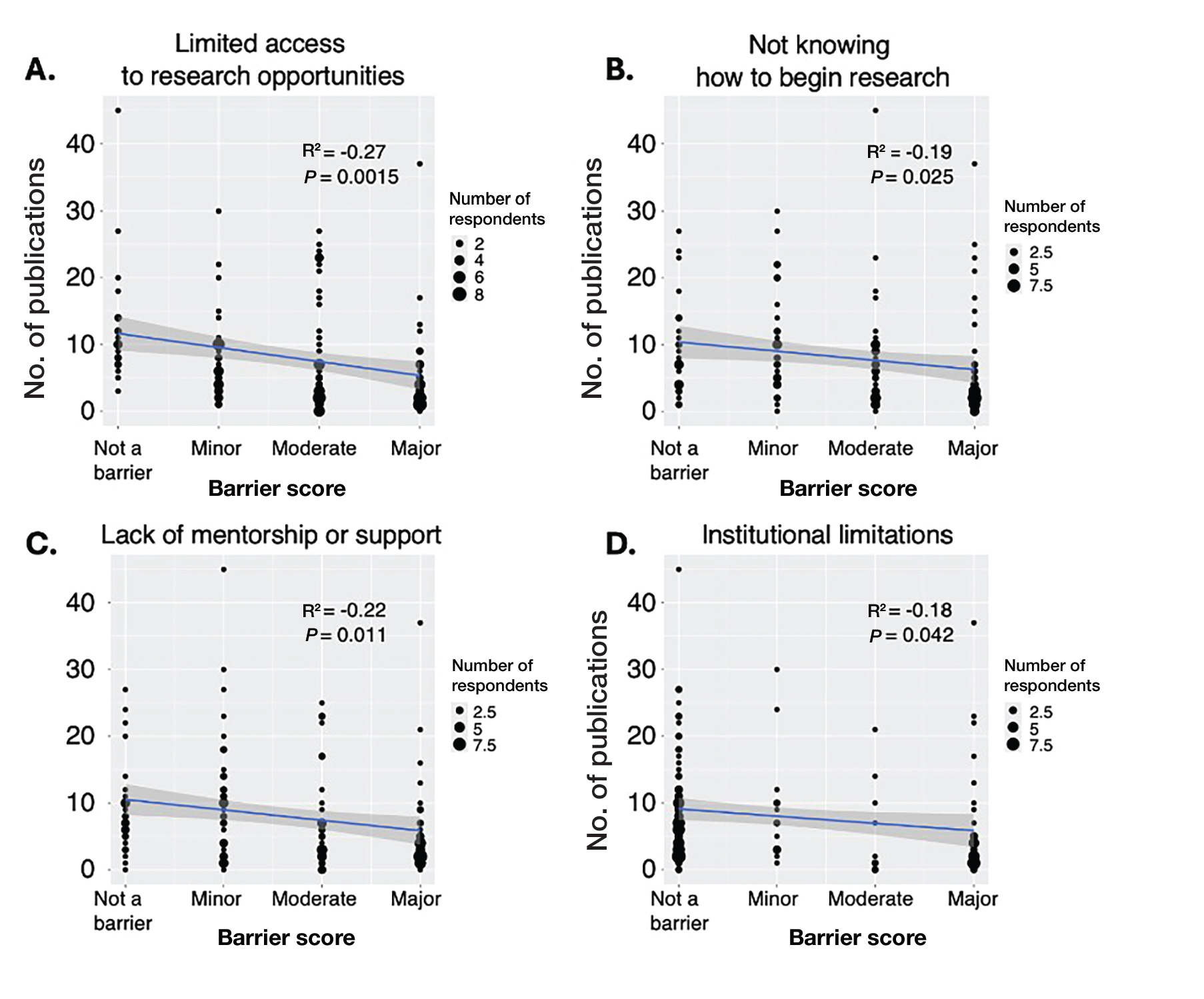

Next, the data were evaluated for correlative relationships between individual research barriers and research productivity metrics including number of publications, published abstracts and presentations (oral and poster) and total research output. While correlations were weak or nonsignificant between barriers and most research productivity metrics (published abstracts, oral and poster presentations, and total research output), the number of publications was significantly correlated with several research barriers, including limited access to research opportunities (P=.002), not knowing how to begin research (P=.025), lack of mentorship or support (P=.011), and institutional limitations (P=.042). Higher ratings for limited access to research opportunities, not knowing where to begin research, lack of mentorship or support, and institutional limitations all were negatively correlated with total number of publications (R2=−.27, –.19, −.22, and –.18, respectively)(eFigure 3).

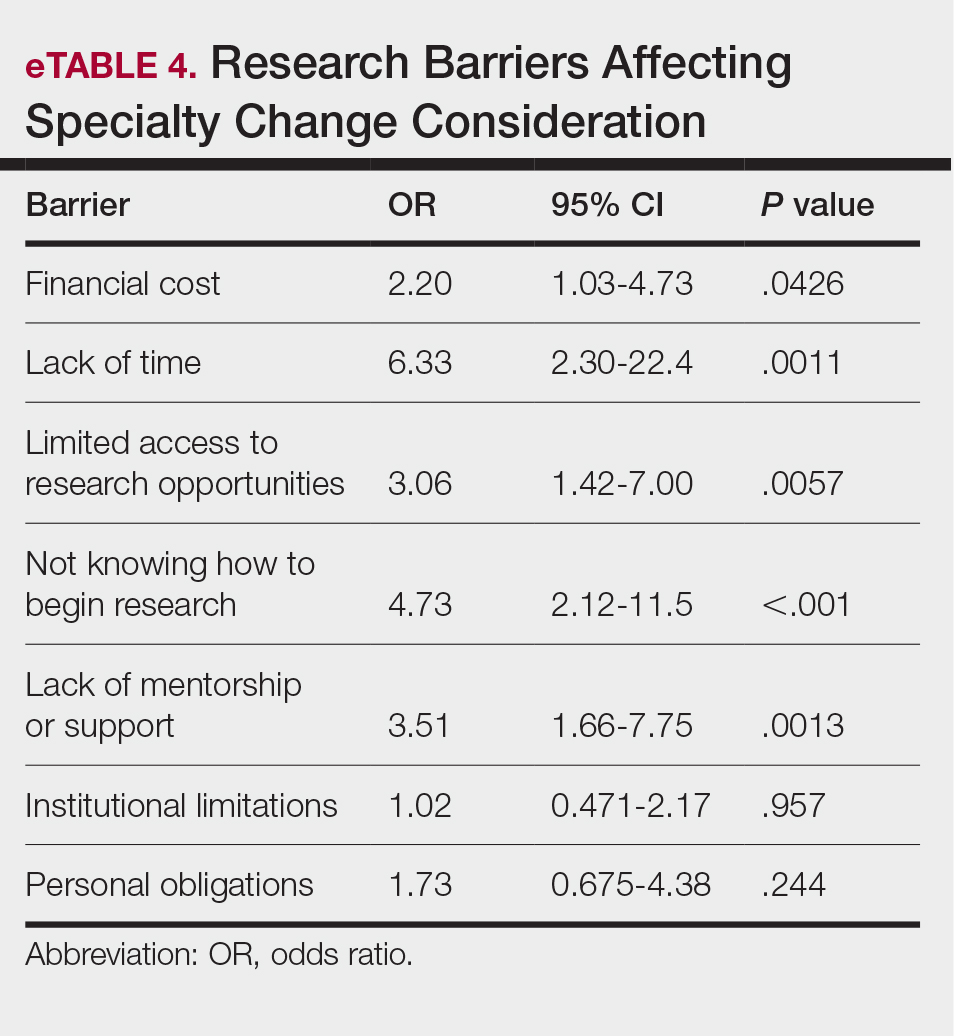

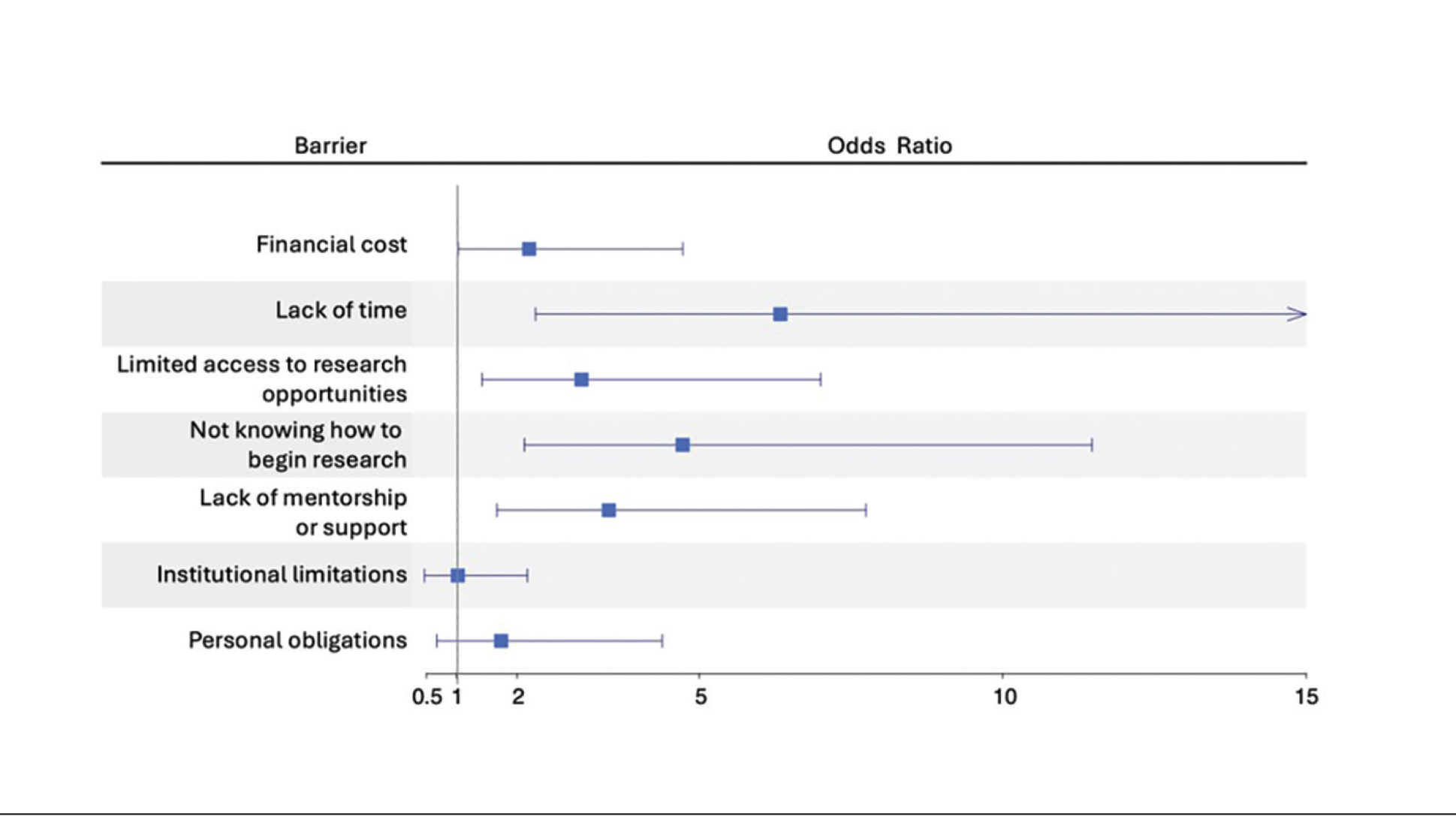

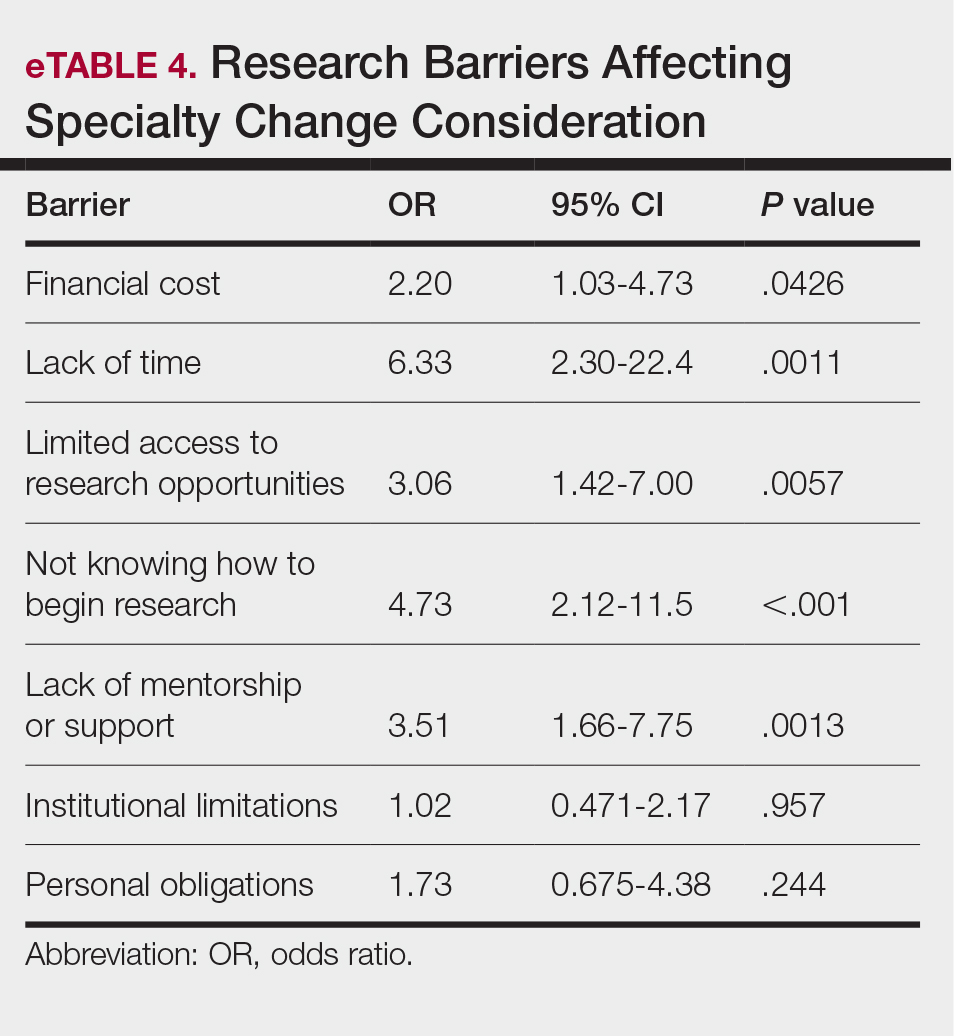

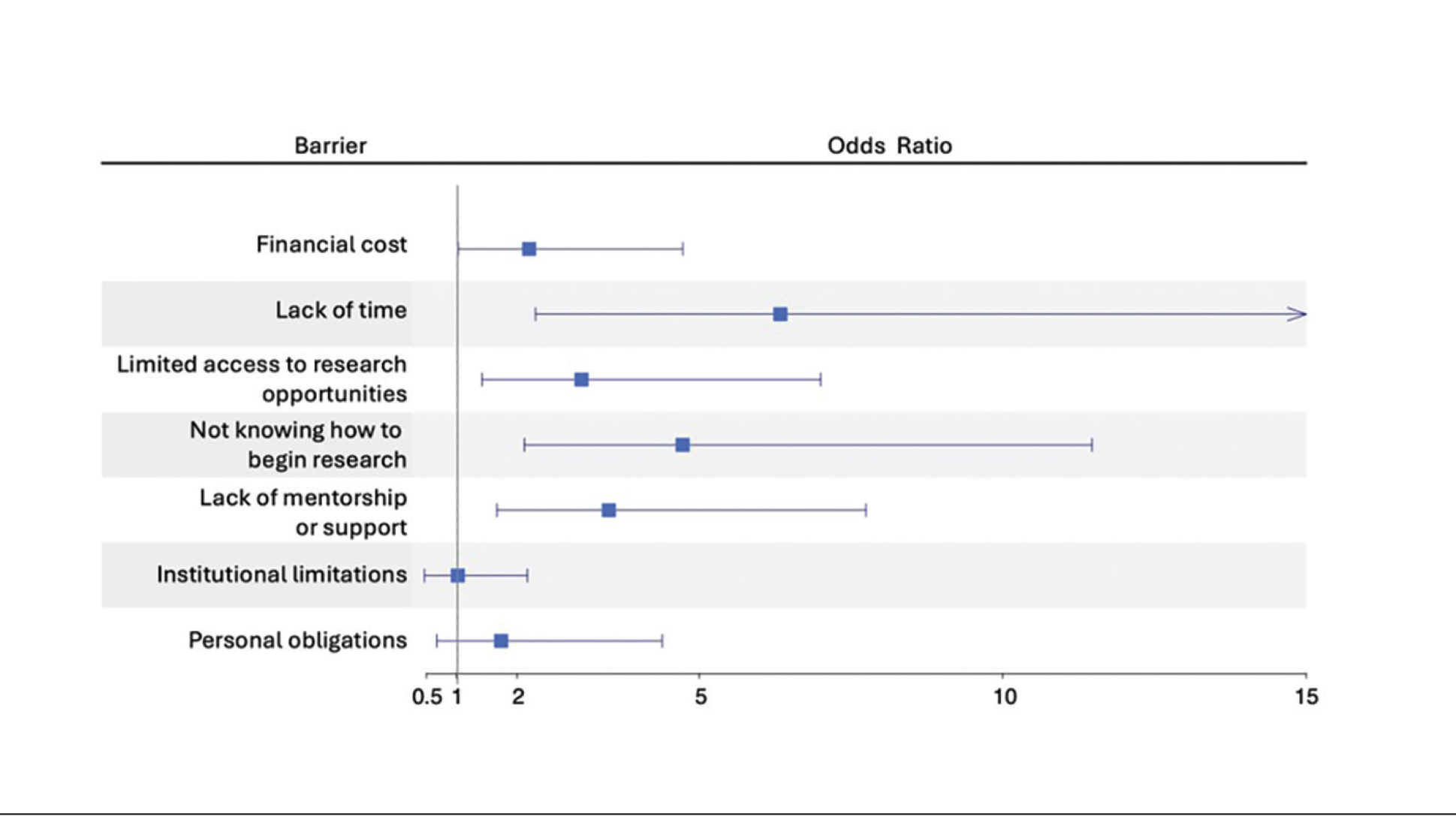

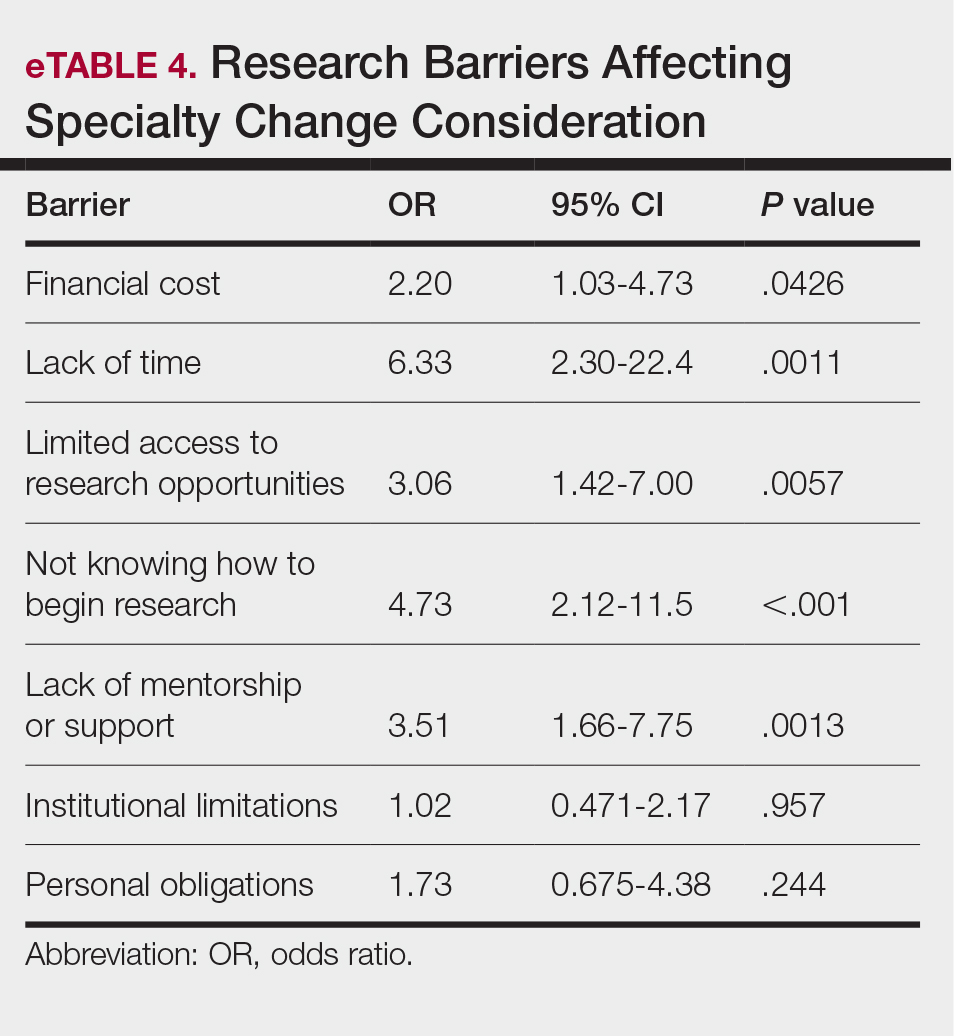

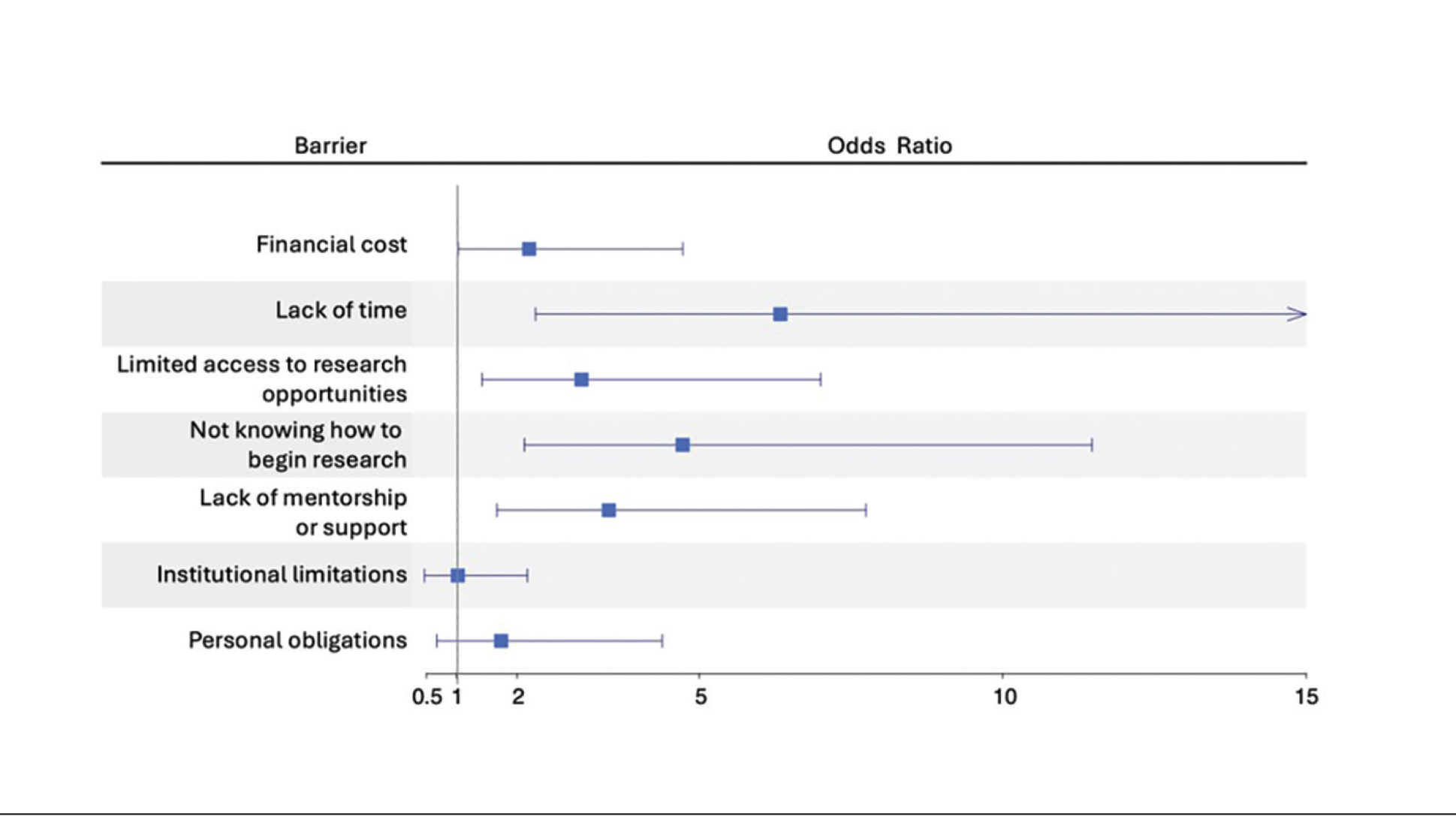

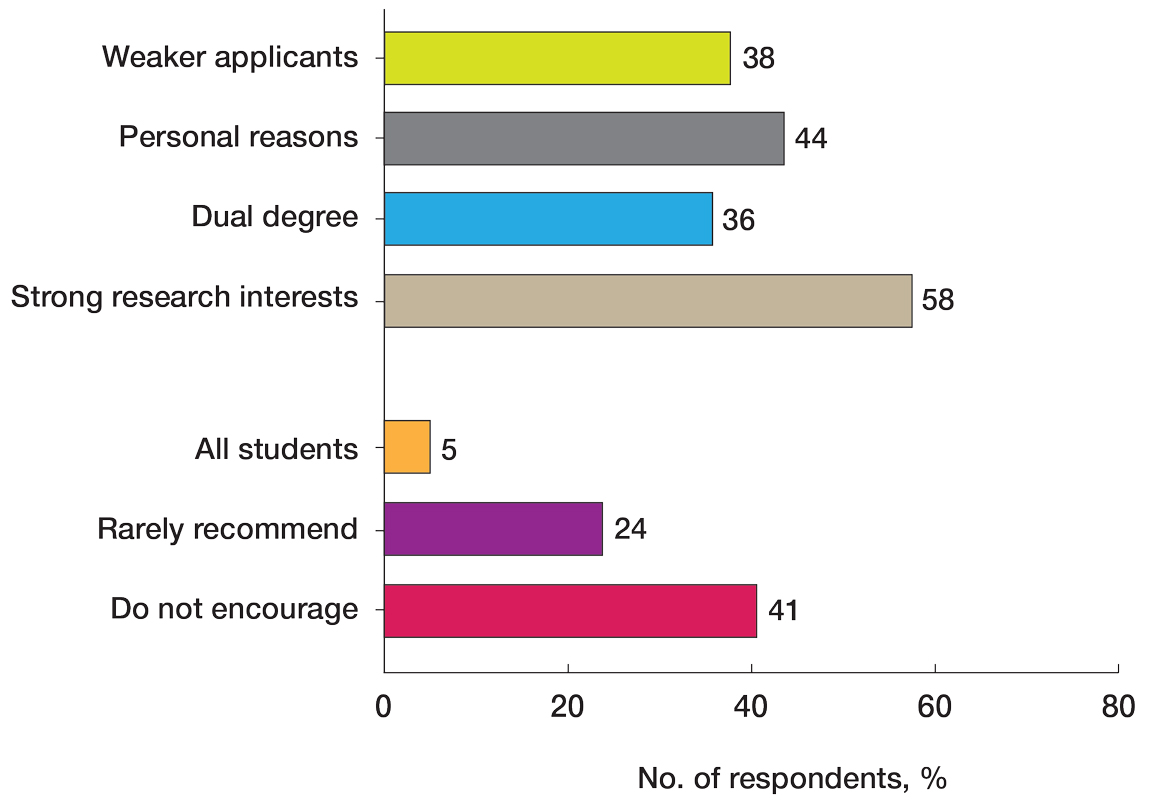

Logistic regression analysis examined the impact of research barriers on the likelihood of specialty change consideration. The results, presented in a forest plot, include odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% CIs and P values. Lack of time (P=.001) and not knowing where to begin research (P<.001) were the strongest predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 6.3 and 4.7, respectively). Financial cost (P=.043), limited access to research opportunities (P=.006), and lack of mentorship or support (P=.001) also were significant predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 2.2, 3.1, and 3.5, respectively). Institutional limitations and personal obligations did not predict specialty change consideration (eTable 4 and eFigure 4).

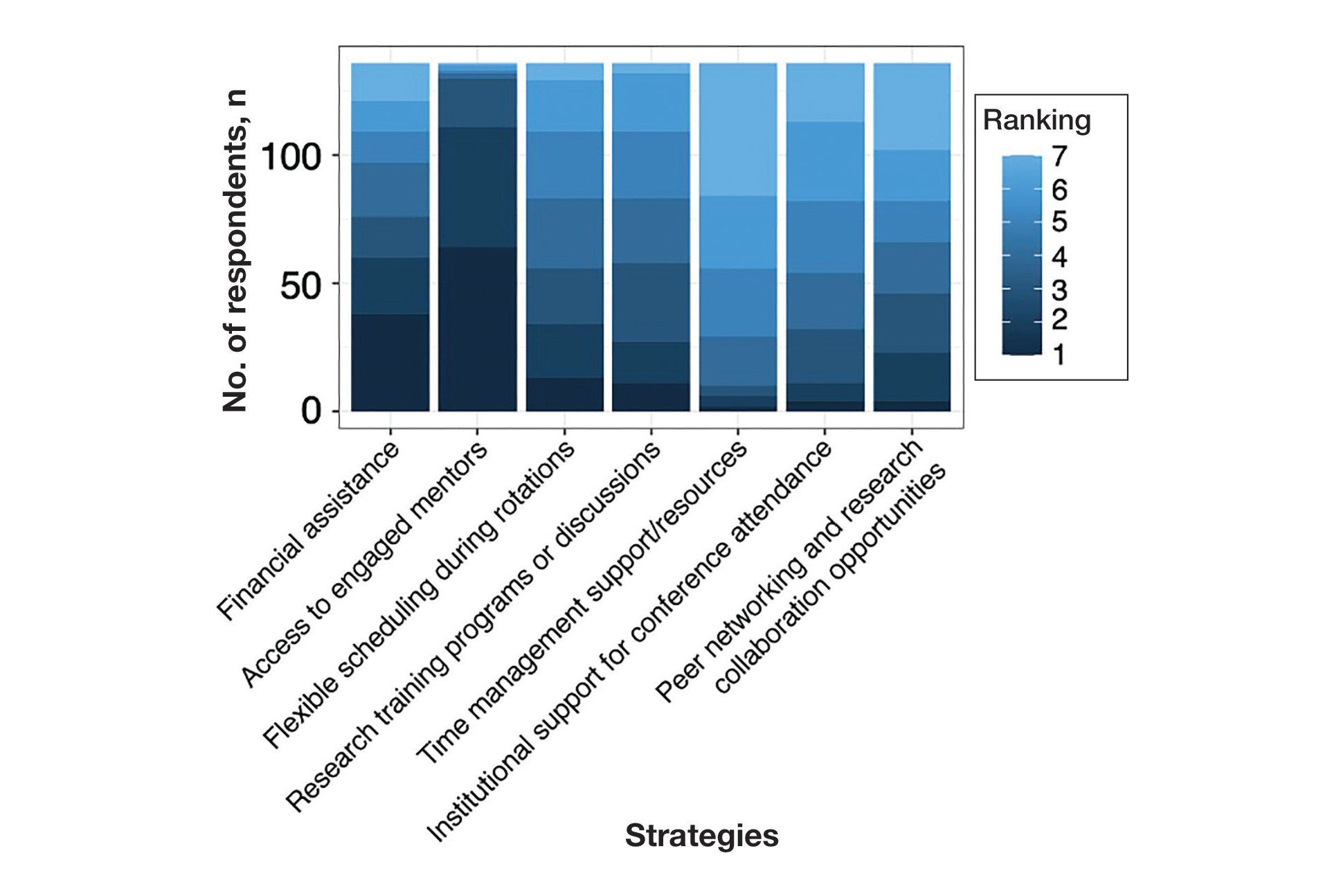

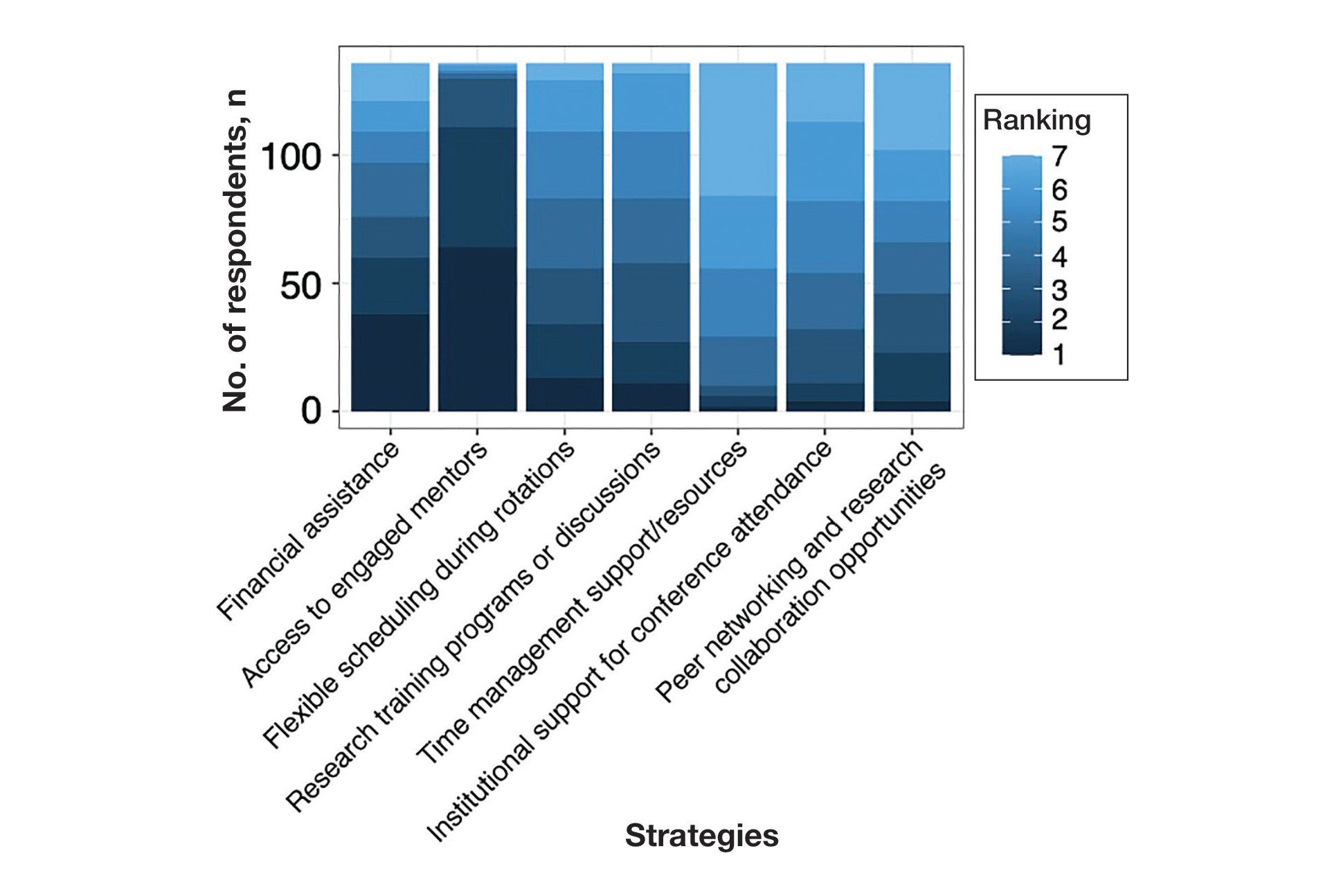

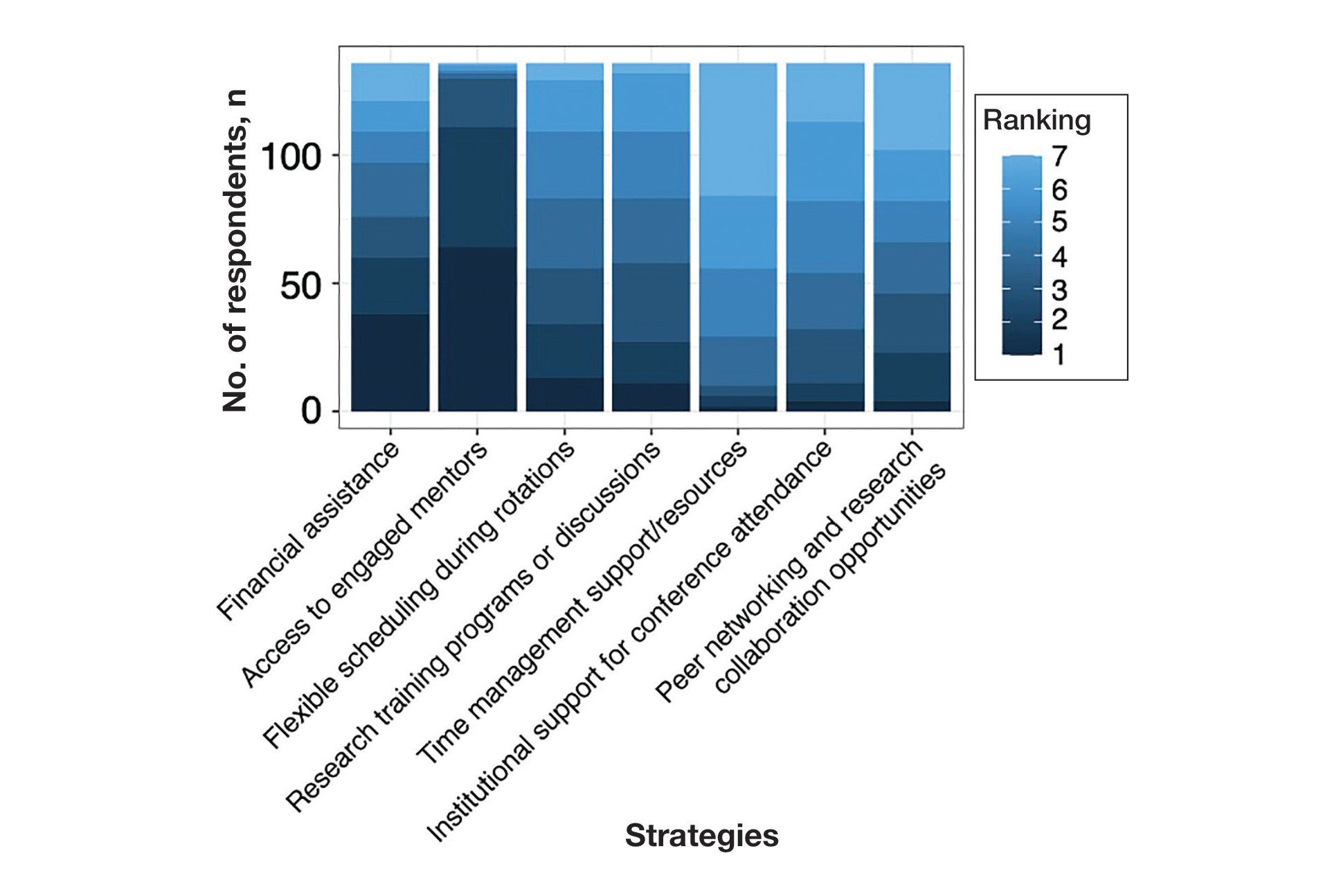

Mitigation Strategies—Mitigation strategies were ranked by respondents based on their perceived importance on a scale of 1 to 7 (1=most important, 7=least important)(eFigure 5). Respondents considered access to engaged mentors to be the most important mitigation strategy by far, with 95% ranking it in the top 3 (47% of respondents ranked it as the top most important mitigation strategy). Financial assistance was the mitigation strategy with the second highest number of respondents (28%) ranking it as the top strategy. Flexible scheduling during rotations, research training programs or discussions, and peer networking and research collaboration opportunities also were considered by respondents to be important mitigation strategies. Time management support/resources frequently was viewed as the least important mitigation strategy, with 38% of respondents ranking it last.

Comment

Our study revealed notable disparities in research barriers among dermatology applicants, with several demonstrating consistent patterns of association with SES, URiM status, and debt burden. Furthermore, the strong relationship between these barriers and decreased research productivity and specialty change consideration suggests that capable candidates may be deterred from pursuing dermatology due to surmountable obstacles rather than lack of interest or ability.

Impact of Demographic Factors on Research Barriers—All 7 general research barriers surveyed were correlated with distinct demographic predictors. Regression analyses indicated that the barrier of financial cost was significantly predicted by lower SES (R²=.2317; P<.001), URiM status (R²=.1097; P<.001), and higher debt levels (R²=.2099; P<.001)(eFigure 2). These findings are particularly concerning given the trend of dermatology applicants pursuing 1-year research fellowships, many of which are unpaid.12 In fact, Jacobson et al11 found that 71.7% (43/60) of dermatology applicants who pursued a year-long research fellowship experienced financial strain during their fellowship, with many requiring additional loans or drawing from personal savings despite already carrying substantial medical school debt of $200,000 or more. Our findings showcase how financial barriers to research disproportionately affect students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, those who identify as URiM, and those with higher debt, creating systemic inequities in research access at a time when research productivity is increasingly vital for matching into dermatology. To address these financial barriers, institutions may consider establishing more funded research fellowships or expanding grant programs targeting students from economically disadvantaged and/or underrepresented backgrounds.

Institutional limitations (eg, the absence of a dermatology department) also was a notable barrier that was significantly predicted by lower SES (R²=.0884; P<.001) and URiM status (R²=.04537; P=.013)(eFigure 2). Students at institutions lacking dermatology programs face restricted access to mentorship and research opportunities,13 with our results demonstrating that these barriers disproportionately affect students from underresourced and minority groups. These limitations compound disparities in building competitive residency applications.14 The Women’s Dermatologic Society (WDS) has developed a model for addressing these institutional barriers through its summer research fellowship program for medical students who identify as URiM. By pairing students with WDS mentors who guide them through summer research projects, this initiative addresses access and mentorship gaps for students lacking dermatology departments at their home institution.15 The WDS program serves as a model for other organizations to adopt and expand, with particular attention to including students who identify as URiM as well as those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Our results identified time constraints and lack of experience as notable research barriers. Higher debt levels significantly predicted both lack of time (R²=.03915; P=.021) and not knowing how to begin research (R²=.0572; P=.005)(eFigure 2). These statistical relationships may be explained by students with higher debt levels needing to prioritize paid work over unpaid research opportunities, limiting their engagement in research due to the scarcity of funded positions.12 The data further revealed that personal obligations, particularly family care responsibilities, were significantly predicted by both lower SES (R²=.0539; P=.008) and higher debt level (R²=.03237; P=.036)(eFigure 2). These findings demonstrate how students managing academic demands alongside financial and familial responsibilities may face compounded barriers to research engagement. To address these disparities, medical schools may consider implementing protected research time within their curricula; for example, the Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta, Georgia) has implemented a Discovery Phase program that provides students with 5 months of protected faculty-mentored research time away from academic demands between their third and fourth years of medical school.16 Integrating similarly structured research periods across medical school curricula could help ensure equitable research opportunities for all students pursuing competitive specialties such as dermatology.8

Access to mentorship is a critical determinant of research engagement and productivity, as mentors provide valuable guidance on navigating research processes and professional development.17 Our analysis revealed that lack of mentorship was predicted by both lower SES (R²=.039; P=.023) and higher debt level (R²=.06553; P=.003)(eFigure 2). Several organizations have developed programs to address these mentorship gaps. The Skin of Color Society pairs medical students with skin of color experts while advancing its mission of increasing diversity in dermatology.18 Similarly, the American Academy of Dermatology founded a diversity mentorship program that connects students who identify as URiM with dermatologist mentors for summer research experiences.19 Notably, the Skin of Color Society’s program allows residents to serve as mentors for medical students. Involving residents and community dermatologists as potential dermatology mentors for medical students not only distributes mentorship demands more sustainably but also increases overall access to dermatology mentors. Our findings indicate that similar programs could be expanded to include more residents and community dermatologists as mentors and to target students from disadvantaged backgrounds, those facing financial constraints, and students who identify as URiM.

Impact of Research Barriers on Career Trajectories—Among survey participants, 35% reported considering changing their specialty choice due to research-related barriers. This substantial percentage likely stems from the escalating pressure to achieve increasingly high research output amidst a lack of sufficient support, time, or tools, as our results suggest. The specific barriers that most notably predicted specialty change consideration were lack of time and not knowing how to begin research (P=.001 and P<.001, respectively). Remarkably, our findings revealed that respondents who rated these as moderate or major barriers were 6.3 and 4.7 times more likely to consider changing their specialty choice, respectively. Respondents reporting financial cost (P=.043), limited access to research opportunities (P=.006), and lack of mentorship or support (P=.001) as at least moderate barriers also were 2.2 to 3.5 times more likely to consider a specialty change (eTable 4 and eFigure 4). Additionally, barriers such as limited access to research opportunities (R²=−.27; P=.002), lack of mentorship (R2=−.22; P=.011), not knowing how to begin research (R2=−.19; P=.025), and institutional limitations (R2=−.18; P=.042) all were associated with lower publication output according to our data (eFigure 3). These findings are especially concerning given current match statistics, where the trajectory of research productivity required for a successful dermatology match continues to rise sharply.3,4

Alarmingly, many of the barriers we identified—linked to both reduced research output and specialty change consideration—are associated with several demographic factors. Higher debt levels predicted greater likelihood of experiencing lack of time, insufficient mentorship, and uncertainty about initiating research, while lower SES was associated with lack of mentorship. These relationships suggest that structural barriers, rather than lack of interest or ability, may create cumulative disadvantages that deter capable candidates from pursuing dermatology or impact their success in the application process.

One potential solution to address the disproportionate emphasis on research quantity would be implementing caps on reportable research products in residency applications (eg, limiting applications to a certain number of publications, abstracts, and presentations). This change could shift applicant focus toward substantive scientific contributions rather than rapid output accumulation.8 The need for such caps was evident in our dataset, which revealed a stark contrast: some respondents reported 30 to 40 publications, while MD/PhD respondents—who dedicate 3 to 5 years to performing quality research—averaged only 7.4 publications. Implementing a research output ceiling could help alleviate barriers for applicants facing institutional and demographic disadvantages while simultaneously boosting the scientific rigor of dermatology research.8

Mitigation Strategies From Applicant Feedback—Our findings emphasize the multifaceted relationship between structural barriers and demographics in dermatology research engagement. While our statistical interpretations have outlined several potential interventions, the applicants’ perspectives on mitigation strategies offer qualitative insight. Although participants did not consistently mark financial cost and lack of mentorship as major barriers (eFigure 1), financial assistance and access to engaged mentors were among the highest-ranked mitigation strategies (eFigure 5), suggesting these resources may be fundamental to overcoming multiple structural challenges. To address these needs comprehensively, we propose a multilevel approach: at the institutional level, dermatology interest groups could establish centralized databases of research opportunities, mentorship programs, and funding sources. At the national level, dermatology organizations could consider expanding grant programs, developing virtual mentorship networks, and creating opportunities for external students through remote research projects or short-term research rotations. These interventions, informed by both our statistical analyses and applicant feedback, could help create more equitable access to research opportunities in dermatology.

Limitations

A major limitation of this study was that potential dermatology candidates who were deterred by barriers and later decided on a different specialty would not be captured in our data. As these candidates may have faced substantial barriers that caused them to choose a different path, their absence from the current data may indicate that the reported results underpredict the effect size of the true population. Another limitation is the absence of a control group, such as applicants to less competitive specialties, which would provide valuable context for whether the barriers identified are unique to dermatology.

Conclusion

Our study provides compelling evidence that research barriers in dermatology residency applications intersect with demographic factors to influence research engagement and career trajectories. Our findings suggest that without targeted intervention, increasing emphasis on research productivity may exacerbate existing disparities in dermatology. Moving forward, a coordinated effort among institutions, dermatology associations, and dermatology residency programs will be fundamental to ensure that research requirements enhance rather than impede the development of a diverse, qualified dermatology workforce.

- Ozair A, Bhat V, Detchou DKE. The US residency selection process after the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 pass/fail change: overview for applicants and educators. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:E37069. doi:10.2196/37069

- Patrinely JR Jr, Zakria D, Drolet BC. USMLE Step 1 changes: dermatology program director perspectives and implications. Cutis. 2021;107:293-294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0277

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: US MD seniors, 2022. July 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Charting-Outcomes-MD-Seniors-2022_Final.pdf

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: US MD seniors, 2024. August 2024. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/08/charting-outcomes-characteristics-of-u-s-md-seniors-who-matched-to-their-preferred-specialty-2024-main-residency-match/

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: characteristics of applicants who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2007 main residency match. July 2021. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/chartingoutcomes2007.pdf

- Sanabria-de la Torre R, Quiñones-Vico MI, Ubago-Rodríguez A, et al. Medical students’ interest in research: changing trends during university training. Front Med. 2023;10. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1257574

- Alikhan A, Sivamani RK, Mutizwa MM, et al. Advice for medical students interested in dermatology: perspectives from fourth year students who matched. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7. doi:10.5070/D398p8q1m5

- Elliott B, Carmody JB. Publish or perish: the research arms race in residency selection. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15:524-527. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-23-00262.1

- Akhiyat S, Cardwell L, Sokumbi O. Why dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine: how did we get here? Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:310-315. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.005

- Orebi HA, Shahin MR, Awad Allah MT, et al. Medical students’ perceptions, experiences, and barriers towards research implementation at the faculty of medicine, Tanta University. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:902. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04884-z

- Jacobsen A, Kabbur G, Freese RL, et al. Socioeconomic factors and financial burdens of research “gap years” for dermatology residency applicants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2023;9:e099. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000099

- Jung J, Stoff BK, Orenstein LAV. Unpaid research fellowships among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1230-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.027

- Rehman R, Shareef SJ, Mohammad TF, et al. Applying to dermatology residency without a home program: advice to medical students in the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:513-515. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.01.003

- Villa NM, Shi VY, Hsiao JL. An underrecognized barrier to the dermatology residency match: lack of a home program. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:512-513. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.02.011

- Sekyere NAN, Grimes PE, Roberts WE, et al. Turning the tide: how the Women’s Dermatologic Society leads in diversifying dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:135-136. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.12.012

- Emory School of Medicine. Four phases in four years. Accessed January 17, 2025. https://med.emory.edu/education/programs/md/curriculum/4phases/index.html

- Bhatnagar V, Diaz S, Bucur PA. The need for more mentorship in medical school. Cureus. 2020;12:E7984. doi:10.7759/cureus.7984

- Skin of Color Society. Mentorship. Accessed January 17, 2025. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/what-we-do/mentorship

- American Academy of Dermatology. Diversity Mentorship Program: information for medical students. Accessed January 17, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/career/awards/diversity

As one of the most competitive specialties in medicine, dermatology presents unique challenges for residency applicants, especially following the shift in United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 scoring to a pass/fail format.1,2 Historically, USMLE Step 1 served as a major screening metric for residency programs, with 90% of program directors in 2020 using USMLE Step 1 scores as a primary factor when deciding whether to invite applicants for interviews.1 However, the recent transition to pass/fail has made it much harder for program directors to objectively compare applicants, particularly in dermatology. In a 2020 survey, Patrinely Jr et al2 found that 77.2% of dermatology program directors agreed that this change would make it more difficult to assess candidates objectively. Consequently, research productivity has taken on greater importance as programs seek new ways to distinguish top applicants.1,2

In response to this increased emphasis on research, dermatology applicants have substantially boosted their scholarly output over the past several years. The 2022 and 2024 results from the National Residency Matching Program’s Charting Outcomes survey demonstrated a steady rise in research metrics among applicants across various specialties, with dermatology showing one of the largest increases.3,4 For instance, the average number of abstracts, presentations, and publications for matched allopathic dermatology applicants was 5.7 in 2007.5 This average increased to 20.9 in 20223 and to 27.7 in 2024,4 marking an astonishing 485% increase in 17 years. Interestingly, unmatched dermatology applicants had an average of 19.0 research products in 2024, which was similar to the average of successfully matched applicants just 2 years earlier.3,4

Engaging in research offers benefits beyond building a strong residency application. Specifically, it enhances critical thinking skills and provides hands-on experience in scientific inquiry.6 It allows students to explore dermatology topics of interest and address existing knowledge gaps within the specialty.6 Additionally, it creates opportunities to build meaningful relationships with experienced dermatologists who can guide and support students throughout their careers.7 Despite these benefits, the pursuit of research may be landscaped with obstacles, and the fervent race to obtain high research outputs may overshadow developmental advantages.8 These challenges and demands also could contribute to inequities in the residency selection process, particularly if barriers are influenced by socioeconomic and demographic disparities. As dermatology already ranks as the second least diverse specialty in medicine,9 research requirements that disproportionately disadvantage certain demographic groups risk further widening these concerning representation gaps rather than creating opportunities to address them.

Given these trends in research requirements and their potential impact on applicant success, understanding specific barriers to research engagement is essential for creating equitable opportunities in dermatology. In this study, we aimed to identify barriers to research engagement among dermatology applicants, analyze their relationship with demographic factors, assess their impact on specialty choice and research productivity, and provide actionable solutions to address these obstacles.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted targeting medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States in the 2025 or 2026 match cycles as well as residents who applied to dermatology residency in the 2021 to 2024 match cycles. The 23-item survey was developed by adapting questions from several validated studies examining research barriers and experiences in medical education.6,7,10,11 Specifically, the survey included questions on demographics and background; research productivity; general research barriers; conference participation accessibility; mentorship access; and quality, career impact, and support needs. Socioeconomic background was measured via a single self-reported item asking participants to select the income class that best reflected their background growing up (low-income, lower-middle, upper-middle, or high-income); no income ranges were provided.

The survey was distributed electronically via Qualtrics between November 11, 2024, and December 30, 2024, through listserves of the Dermatology Interest Group Association (sent directly to medical students) and the Association of Professors of Dermatology (forwarded to residents by program directors). There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants and residents reached through either listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional review board (IRB-300013671).

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio (Posit, PBC; version 2024.12.0+467). Descriptive statistics characterized participant demographics and quantified barrier scores using frequencies and proportions. We performed regression analyses to examine relationships between demographic factors and barriers using linear regression; the relationship between barriers and research productivity correlation; and the prediction of specialty change consideration using logistic regression. For all analyses, barrier scores were rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=not a barrier, 1=minor barrier, 2=moderate barrier, 3=major barrier); R² values were reported to indicate strength of associations, and statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Participant Demographics—A total of 136 participants completed the survey. Among the respondents, 12% identified as from a background of low-income class, 28% lower-middle class, 49% upper-middle class, and 11% high-income class. Additionally, 27% of respondents identified as underrepresented in medicine (URiM). Regarding debt levels (or expected debt levels) upon graduation from medical school, 32% reported no debt, 9% reported $1000 to $49,000 in debt, 5% reported $50,000 to $99,000 in debt, 15% reported $100,000 to $199,000 in debt, 22% reported $200,000 to $299,000 in debt, and 17% reported $300,000 in debt or higher. The majority of respondents (95%) were MD candidates, and the remaining 5% were DO candidates; additionally, 5% were participants in an MD/PhD program (eTable 1).

Respondents represented various stages of training: 13.2% and 16.2% were third- and fourth-year medical students, respectively, while 6.0%, 20.1%, 18.4%, and 22.8% were postgraduate year (PGY) 1, PGY-2, PGY-3, and PGY-4, respectively. A few respondents (2.9%) were participating in a research year or reapplying to dermatology residency (eTable 2).

Research Barriers and Productivity—Respondents were presented with a list of potential barriers and asked to rate each as not a barrier, a minor barrier, a moderate barrier, or a major barrier. The most common barriers (ie, those with >50% of respondents rating them as a moderate or major) included lack of time, limited access to research opportunities, not knowing how to begin research, and lack of mentorship or support. Lack of time and not knowing where to begin research were reported most frequently as major barriers, with 32% of participants identifying them as such. In contrast, barriers such as financial costs and personal obligations were less frequently rated as major barriers (10% and 4%, respectively), although they still were identified as obstacles by many respondents. Interestingly, most respondents (58%) indicated that institutional limitations were not a barrier, but a separate and sizeable proportion (25%) of respondents considered it to be a major barrier (eFigure 1).

The distributions for all research metrics were right-skewed. The total range was 0 to 45 (median, 6) for number of publications (excluding abstracts), 0 to 33 (median, 2) for published abstracts, 0 to 40 (median, 5) for poster publications, and 0 to 20 (median, 2) for oral presentations (eTable 3).

Regression Analysis—Linear regression analysis identified significant relationships between demographic variables (socioeconomic status [SES], URiM status, and debt level) and individual research barriers. The heatmap in eFigure 2 illustrates the strength of these relationships. Higher SES was predictive of lower reported financial barriers (R²=.2317; P<.0001) and lower reported institutional limitations (R²=.0884; P=.0006). A URiM status predicted higher reported financial barriers (R²=.1097; P<.0001) and institutional limitations (R²=.04537; P=.013). Also, higher debt level predicted increased financial barriers (R²=.2099; P<.0001), institutional limitations (R2=.1258; P<.0001), and lack of mentorship (R²=.06553; P=.003).

Next, the data were evaluated for correlative relationships between individual research barriers and research productivity metrics including number of publications, published abstracts and presentations (oral and poster) and total research output. While correlations were weak or nonsignificant between barriers and most research productivity metrics (published abstracts, oral and poster presentations, and total research output), the number of publications was significantly correlated with several research barriers, including limited access to research opportunities (P=.002), not knowing how to begin research (P=.025), lack of mentorship or support (P=.011), and institutional limitations (P=.042). Higher ratings for limited access to research opportunities, not knowing where to begin research, lack of mentorship or support, and institutional limitations all were negatively correlated with total number of publications (R2=−.27, –.19, −.22, and –.18, respectively)(eFigure 3).

Logistic regression analysis examined the impact of research barriers on the likelihood of specialty change consideration. The results, presented in a forest plot, include odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% CIs and P values. Lack of time (P=.001) and not knowing where to begin research (P<.001) were the strongest predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 6.3 and 4.7, respectively). Financial cost (P=.043), limited access to research opportunities (P=.006), and lack of mentorship or support (P=.001) also were significant predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 2.2, 3.1, and 3.5, respectively). Institutional limitations and personal obligations did not predict specialty change consideration (eTable 4 and eFigure 4).

Mitigation Strategies—Mitigation strategies were ranked by respondents based on their perceived importance on a scale of 1 to 7 (1=most important, 7=least important)(eFigure 5). Respondents considered access to engaged mentors to be the most important mitigation strategy by far, with 95% ranking it in the top 3 (47% of respondents ranked it as the top most important mitigation strategy). Financial assistance was the mitigation strategy with the second highest number of respondents (28%) ranking it as the top strategy. Flexible scheduling during rotations, research training programs or discussions, and peer networking and research collaboration opportunities also were considered by respondents to be important mitigation strategies. Time management support/resources frequently was viewed as the least important mitigation strategy, with 38% of respondents ranking it last.

Comment

Our study revealed notable disparities in research barriers among dermatology applicants, with several demonstrating consistent patterns of association with SES, URiM status, and debt burden. Furthermore, the strong relationship between these barriers and decreased research productivity and specialty change consideration suggests that capable candidates may be deterred from pursuing dermatology due to surmountable obstacles rather than lack of interest or ability.

Impact of Demographic Factors on Research Barriers—All 7 general research barriers surveyed were correlated with distinct demographic predictors. Regression analyses indicated that the barrier of financial cost was significantly predicted by lower SES (R²=.2317; P<.001), URiM status (R²=.1097; P<.001), and higher debt levels (R²=.2099; P<.001)(eFigure 2). These findings are particularly concerning given the trend of dermatology applicants pursuing 1-year research fellowships, many of which are unpaid.12 In fact, Jacobson et al11 found that 71.7% (43/60) of dermatology applicants who pursued a year-long research fellowship experienced financial strain during their fellowship, with many requiring additional loans or drawing from personal savings despite already carrying substantial medical school debt of $200,000 or more. Our findings showcase how financial barriers to research disproportionately affect students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, those who identify as URiM, and those with higher debt, creating systemic inequities in research access at a time when research productivity is increasingly vital for matching into dermatology. To address these financial barriers, institutions may consider establishing more funded research fellowships or expanding grant programs targeting students from economically disadvantaged and/or underrepresented backgrounds.

Institutional limitations (eg, the absence of a dermatology department) also was a notable barrier that was significantly predicted by lower SES (R²=.0884; P<.001) and URiM status (R²=.04537; P=.013)(eFigure 2). Students at institutions lacking dermatology programs face restricted access to mentorship and research opportunities,13 with our results demonstrating that these barriers disproportionately affect students from underresourced and minority groups. These limitations compound disparities in building competitive residency applications.14 The Women’s Dermatologic Society (WDS) has developed a model for addressing these institutional barriers through its summer research fellowship program for medical students who identify as URiM. By pairing students with WDS mentors who guide them through summer research projects, this initiative addresses access and mentorship gaps for students lacking dermatology departments at their home institution.15 The WDS program serves as a model for other organizations to adopt and expand, with particular attention to including students who identify as URiM as well as those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Our results identified time constraints and lack of experience as notable research barriers. Higher debt levels significantly predicted both lack of time (R²=.03915; P=.021) and not knowing how to begin research (R²=.0572; P=.005)(eFigure 2). These statistical relationships may be explained by students with higher debt levels needing to prioritize paid work over unpaid research opportunities, limiting their engagement in research due to the scarcity of funded positions.12 The data further revealed that personal obligations, particularly family care responsibilities, were significantly predicted by both lower SES (R²=.0539; P=.008) and higher debt level (R²=.03237; P=.036)(eFigure 2). These findings demonstrate how students managing academic demands alongside financial and familial responsibilities may face compounded barriers to research engagement. To address these disparities, medical schools may consider implementing protected research time within their curricula; for example, the Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta, Georgia) has implemented a Discovery Phase program that provides students with 5 months of protected faculty-mentored research time away from academic demands between their third and fourth years of medical school.16 Integrating similarly structured research periods across medical school curricula could help ensure equitable research opportunities for all students pursuing competitive specialties such as dermatology.8

Access to mentorship is a critical determinant of research engagement and productivity, as mentors provide valuable guidance on navigating research processes and professional development.17 Our analysis revealed that lack of mentorship was predicted by both lower SES (R²=.039; P=.023) and higher debt level (R²=.06553; P=.003)(eFigure 2). Several organizations have developed programs to address these mentorship gaps. The Skin of Color Society pairs medical students with skin of color experts while advancing its mission of increasing diversity in dermatology.18 Similarly, the American Academy of Dermatology founded a diversity mentorship program that connects students who identify as URiM with dermatologist mentors for summer research experiences.19 Notably, the Skin of Color Society’s program allows residents to serve as mentors for medical students. Involving residents and community dermatologists as potential dermatology mentors for medical students not only distributes mentorship demands more sustainably but also increases overall access to dermatology mentors. Our findings indicate that similar programs could be expanded to include more residents and community dermatologists as mentors and to target students from disadvantaged backgrounds, those facing financial constraints, and students who identify as URiM.

Impact of Research Barriers on Career Trajectories—Among survey participants, 35% reported considering changing their specialty choice due to research-related barriers. This substantial percentage likely stems from the escalating pressure to achieve increasingly high research output amidst a lack of sufficient support, time, or tools, as our results suggest. The specific barriers that most notably predicted specialty change consideration were lack of time and not knowing how to begin research (P=.001 and P<.001, respectively). Remarkably, our findings revealed that respondents who rated these as moderate or major barriers were 6.3 and 4.7 times more likely to consider changing their specialty choice, respectively. Respondents reporting financial cost (P=.043), limited access to research opportunities (P=.006), and lack of mentorship or support (P=.001) as at least moderate barriers also were 2.2 to 3.5 times more likely to consider a specialty change (eTable 4 and eFigure 4). Additionally, barriers such as limited access to research opportunities (R²=−.27; P=.002), lack of mentorship (R2=−.22; P=.011), not knowing how to begin research (R2=−.19; P=.025), and institutional limitations (R2=−.18; P=.042) all were associated with lower publication output according to our data (eFigure 3). These findings are especially concerning given current match statistics, where the trajectory of research productivity required for a successful dermatology match continues to rise sharply.3,4

Alarmingly, many of the barriers we identified—linked to both reduced research output and specialty change consideration—are associated with several demographic factors. Higher debt levels predicted greater likelihood of experiencing lack of time, insufficient mentorship, and uncertainty about initiating research, while lower SES was associated with lack of mentorship. These relationships suggest that structural barriers, rather than lack of interest or ability, may create cumulative disadvantages that deter capable candidates from pursuing dermatology or impact their success in the application process.

One potential solution to address the disproportionate emphasis on research quantity would be implementing caps on reportable research products in residency applications (eg, limiting applications to a certain number of publications, abstracts, and presentations). This change could shift applicant focus toward substantive scientific contributions rather than rapid output accumulation.8 The need for such caps was evident in our dataset, which revealed a stark contrast: some respondents reported 30 to 40 publications, while MD/PhD respondents—who dedicate 3 to 5 years to performing quality research—averaged only 7.4 publications. Implementing a research output ceiling could help alleviate barriers for applicants facing institutional and demographic disadvantages while simultaneously boosting the scientific rigor of dermatology research.8

Mitigation Strategies From Applicant Feedback—Our findings emphasize the multifaceted relationship between structural barriers and demographics in dermatology research engagement. While our statistical interpretations have outlined several potential interventions, the applicants’ perspectives on mitigation strategies offer qualitative insight. Although participants did not consistently mark financial cost and lack of mentorship as major barriers (eFigure 1), financial assistance and access to engaged mentors were among the highest-ranked mitigation strategies (eFigure 5), suggesting these resources may be fundamental to overcoming multiple structural challenges. To address these needs comprehensively, we propose a multilevel approach: at the institutional level, dermatology interest groups could establish centralized databases of research opportunities, mentorship programs, and funding sources. At the national level, dermatology organizations could consider expanding grant programs, developing virtual mentorship networks, and creating opportunities for external students through remote research projects or short-term research rotations. These interventions, informed by both our statistical analyses and applicant feedback, could help create more equitable access to research opportunities in dermatology.

Limitations

A major limitation of this study was that potential dermatology candidates who were deterred by barriers and later decided on a different specialty would not be captured in our data. As these candidates may have faced substantial barriers that caused them to choose a different path, their absence from the current data may indicate that the reported results underpredict the effect size of the true population. Another limitation is the absence of a control group, such as applicants to less competitive specialties, which would provide valuable context for whether the barriers identified are unique to dermatology.

Conclusion

Our study provides compelling evidence that research barriers in dermatology residency applications intersect with demographic factors to influence research engagement and career trajectories. Our findings suggest that without targeted intervention, increasing emphasis on research productivity may exacerbate existing disparities in dermatology. Moving forward, a coordinated effort among institutions, dermatology associations, and dermatology residency programs will be fundamental to ensure that research requirements enhance rather than impede the development of a diverse, qualified dermatology workforce.

As one of the most competitive specialties in medicine, dermatology presents unique challenges for residency applicants, especially following the shift in United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 scoring to a pass/fail format.1,2 Historically, USMLE Step 1 served as a major screening metric for residency programs, with 90% of program directors in 2020 using USMLE Step 1 scores as a primary factor when deciding whether to invite applicants for interviews.1 However, the recent transition to pass/fail has made it much harder for program directors to objectively compare applicants, particularly in dermatology. In a 2020 survey, Patrinely Jr et al2 found that 77.2% of dermatology program directors agreed that this change would make it more difficult to assess candidates objectively. Consequently, research productivity has taken on greater importance as programs seek new ways to distinguish top applicants.1,2

In response to this increased emphasis on research, dermatology applicants have substantially boosted their scholarly output over the past several years. The 2022 and 2024 results from the National Residency Matching Program’s Charting Outcomes survey demonstrated a steady rise in research metrics among applicants across various specialties, with dermatology showing one of the largest increases.3,4 For instance, the average number of abstracts, presentations, and publications for matched allopathic dermatology applicants was 5.7 in 2007.5 This average increased to 20.9 in 20223 and to 27.7 in 2024,4 marking an astonishing 485% increase in 17 years. Interestingly, unmatched dermatology applicants had an average of 19.0 research products in 2024, which was similar to the average of successfully matched applicants just 2 years earlier.3,4

Engaging in research offers benefits beyond building a strong residency application. Specifically, it enhances critical thinking skills and provides hands-on experience in scientific inquiry.6 It allows students to explore dermatology topics of interest and address existing knowledge gaps within the specialty.6 Additionally, it creates opportunities to build meaningful relationships with experienced dermatologists who can guide and support students throughout their careers.7 Despite these benefits, the pursuit of research may be landscaped with obstacles, and the fervent race to obtain high research outputs may overshadow developmental advantages.8 These challenges and demands also could contribute to inequities in the residency selection process, particularly if barriers are influenced by socioeconomic and demographic disparities. As dermatology already ranks as the second least diverse specialty in medicine,9 research requirements that disproportionately disadvantage certain demographic groups risk further widening these concerning representation gaps rather than creating opportunities to address them.

Given these trends in research requirements and their potential impact on applicant success, understanding specific barriers to research engagement is essential for creating equitable opportunities in dermatology. In this study, we aimed to identify barriers to research engagement among dermatology applicants, analyze their relationship with demographic factors, assess their impact on specialty choice and research productivity, and provide actionable solutions to address these obstacles.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted targeting medical students applying to dermatology residency programs in the United States in the 2025 or 2026 match cycles as well as residents who applied to dermatology residency in the 2021 to 2024 match cycles. The 23-item survey was developed by adapting questions from several validated studies examining research barriers and experiences in medical education.6,7,10,11 Specifically, the survey included questions on demographics and background; research productivity; general research barriers; conference participation accessibility; mentorship access; and quality, career impact, and support needs. Socioeconomic background was measured via a single self-reported item asking participants to select the income class that best reflected their background growing up (low-income, lower-middle, upper-middle, or high-income); no income ranges were provided.

The survey was distributed electronically via Qualtrics between November 11, 2024, and December 30, 2024, through listserves of the Dermatology Interest Group Association (sent directly to medical students) and the Association of Professors of Dermatology (forwarded to residents by program directors). There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants and residents reached through either listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional review board (IRB-300013671).

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio (Posit, PBC; version 2024.12.0+467). Descriptive statistics characterized participant demographics and quantified barrier scores using frequencies and proportions. We performed regression analyses to examine relationships between demographic factors and barriers using linear regression; the relationship between barriers and research productivity correlation; and the prediction of specialty change consideration using logistic regression. For all analyses, barrier scores were rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=not a barrier, 1=minor barrier, 2=moderate barrier, 3=major barrier); R² values were reported to indicate strength of associations, and statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Participant Demographics—A total of 136 participants completed the survey. Among the respondents, 12% identified as from a background of low-income class, 28% lower-middle class, 49% upper-middle class, and 11% high-income class. Additionally, 27% of respondents identified as underrepresented in medicine (URiM). Regarding debt levels (or expected debt levels) upon graduation from medical school, 32% reported no debt, 9% reported $1000 to $49,000 in debt, 5% reported $50,000 to $99,000 in debt, 15% reported $100,000 to $199,000 in debt, 22% reported $200,000 to $299,000 in debt, and 17% reported $300,000 in debt or higher. The majority of respondents (95%) were MD candidates, and the remaining 5% were DO candidates; additionally, 5% were participants in an MD/PhD program (eTable 1).

Respondents represented various stages of training: 13.2% and 16.2% were third- and fourth-year medical students, respectively, while 6.0%, 20.1%, 18.4%, and 22.8% were postgraduate year (PGY) 1, PGY-2, PGY-3, and PGY-4, respectively. A few respondents (2.9%) were participating in a research year or reapplying to dermatology residency (eTable 2).

Research Barriers and Productivity—Respondents were presented with a list of potential barriers and asked to rate each as not a barrier, a minor barrier, a moderate barrier, or a major barrier. The most common barriers (ie, those with >50% of respondents rating them as a moderate or major) included lack of time, limited access to research opportunities, not knowing how to begin research, and lack of mentorship or support. Lack of time and not knowing where to begin research were reported most frequently as major barriers, with 32% of participants identifying them as such. In contrast, barriers such as financial costs and personal obligations were less frequently rated as major barriers (10% and 4%, respectively), although they still were identified as obstacles by many respondents. Interestingly, most respondents (58%) indicated that institutional limitations were not a barrier, but a separate and sizeable proportion (25%) of respondents considered it to be a major barrier (eFigure 1).

The distributions for all research metrics were right-skewed. The total range was 0 to 45 (median, 6) for number of publications (excluding abstracts), 0 to 33 (median, 2) for published abstracts, 0 to 40 (median, 5) for poster publications, and 0 to 20 (median, 2) for oral presentations (eTable 3).

Regression Analysis—Linear regression analysis identified significant relationships between demographic variables (socioeconomic status [SES], URiM status, and debt level) and individual research barriers. The heatmap in eFigure 2 illustrates the strength of these relationships. Higher SES was predictive of lower reported financial barriers (R²=.2317; P<.0001) and lower reported institutional limitations (R²=.0884; P=.0006). A URiM status predicted higher reported financial barriers (R²=.1097; P<.0001) and institutional limitations (R²=.04537; P=.013). Also, higher debt level predicted increased financial barriers (R²=.2099; P<.0001), institutional limitations (R2=.1258; P<.0001), and lack of mentorship (R²=.06553; P=.003).

Next, the data were evaluated for correlative relationships between individual research barriers and research productivity metrics including number of publications, published abstracts and presentations (oral and poster) and total research output. While correlations were weak or nonsignificant between barriers and most research productivity metrics (published abstracts, oral and poster presentations, and total research output), the number of publications was significantly correlated with several research barriers, including limited access to research opportunities (P=.002), not knowing how to begin research (P=.025), lack of mentorship or support (P=.011), and institutional limitations (P=.042). Higher ratings for limited access to research opportunities, not knowing where to begin research, lack of mentorship or support, and institutional limitations all were negatively correlated with total number of publications (R2=−.27, –.19, −.22, and –.18, respectively)(eFigure 3).

Logistic regression analysis examined the impact of research barriers on the likelihood of specialty change consideration. The results, presented in a forest plot, include odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% CIs and P values. Lack of time (P=.001) and not knowing where to begin research (P<.001) were the strongest predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 6.3 and 4.7, respectively). Financial cost (P=.043), limited access to research opportunities (P=.006), and lack of mentorship or support (P=.001) also were significant predictors of specialty change consideration (OR, 2.2, 3.1, and 3.5, respectively). Institutional limitations and personal obligations did not predict specialty change consideration (eTable 4 and eFigure 4).

Mitigation Strategies—Mitigation strategies were ranked by respondents based on their perceived importance on a scale of 1 to 7 (1=most important, 7=least important)(eFigure 5). Respondents considered access to engaged mentors to be the most important mitigation strategy by far, with 95% ranking it in the top 3 (47% of respondents ranked it as the top most important mitigation strategy). Financial assistance was the mitigation strategy with the second highest number of respondents (28%) ranking it as the top strategy. Flexible scheduling during rotations, research training programs or discussions, and peer networking and research collaboration opportunities also were considered by respondents to be important mitigation strategies. Time management support/resources frequently was viewed as the least important mitigation strategy, with 38% of respondents ranking it last.

Comment

Our study revealed notable disparities in research barriers among dermatology applicants, with several demonstrating consistent patterns of association with SES, URiM status, and debt burden. Furthermore, the strong relationship between these barriers and decreased research productivity and specialty change consideration suggests that capable candidates may be deterred from pursuing dermatology due to surmountable obstacles rather than lack of interest or ability.