User login

Pink Papules on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

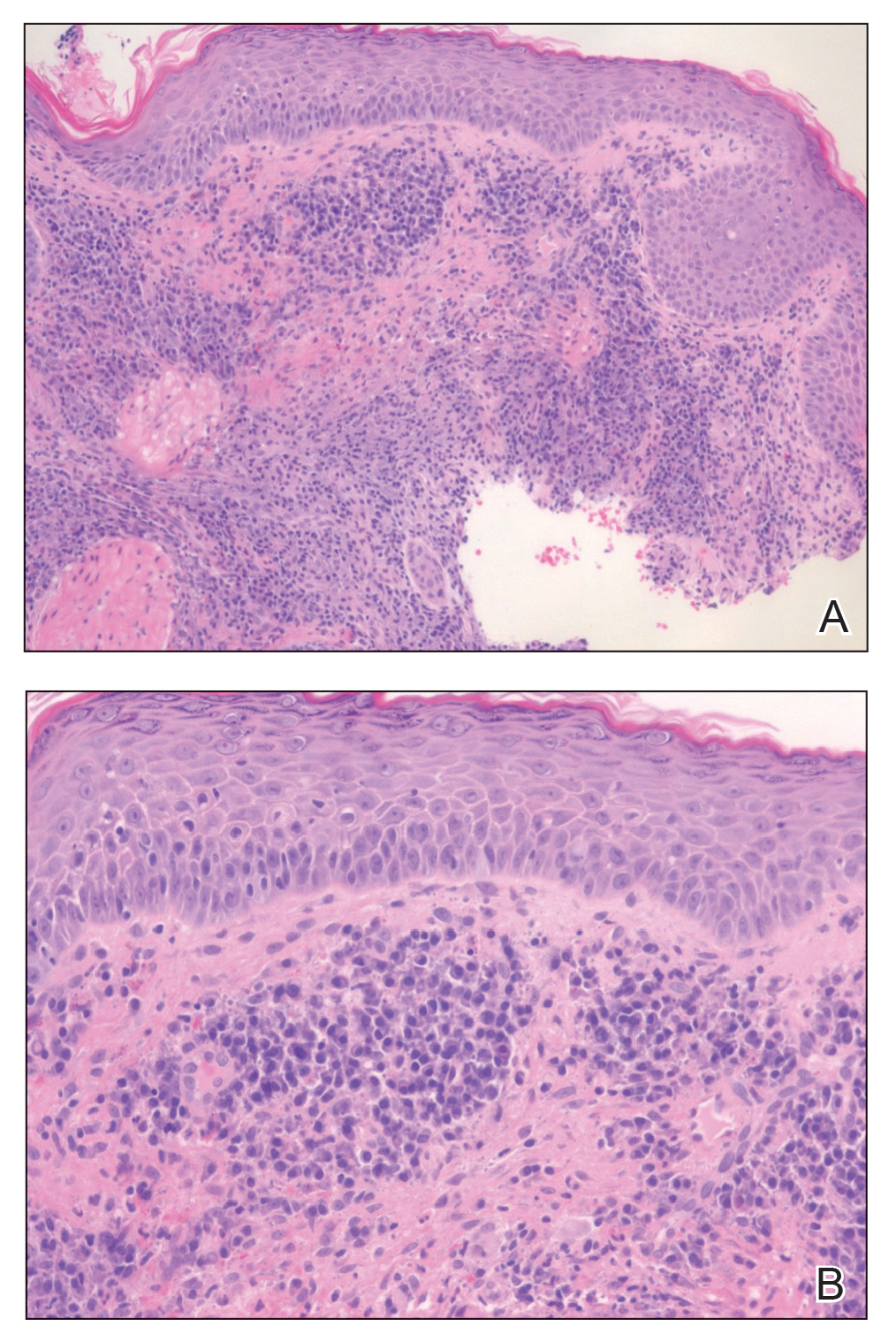

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

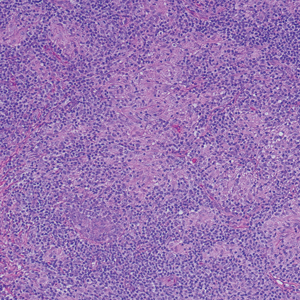

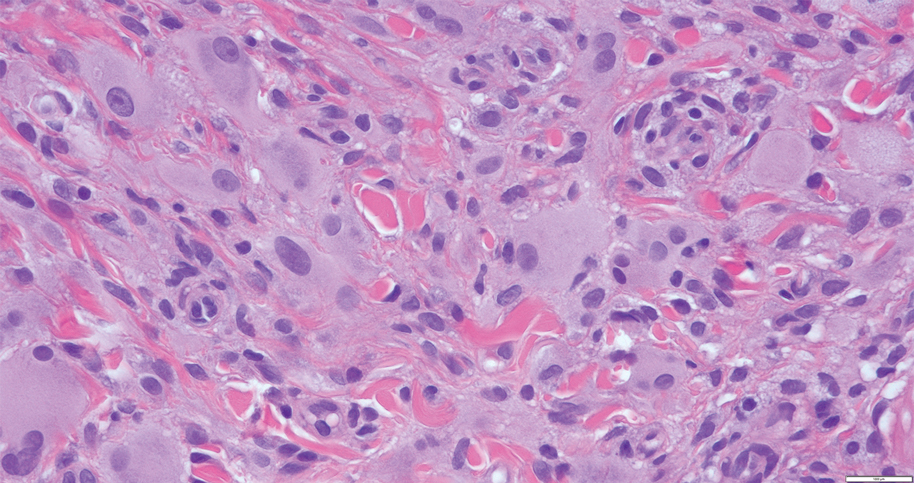

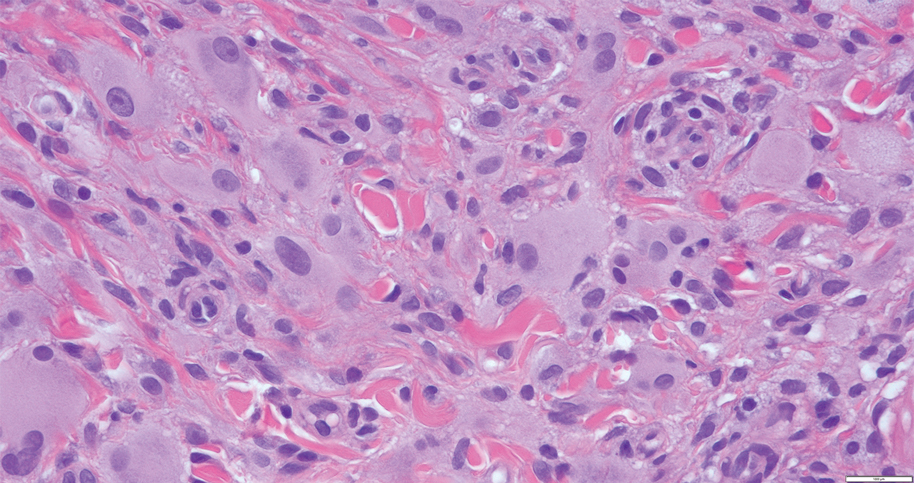

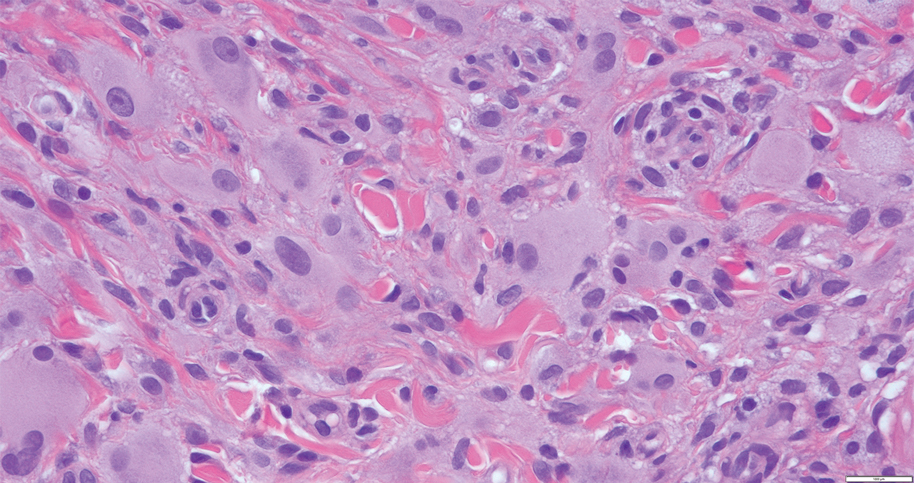

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

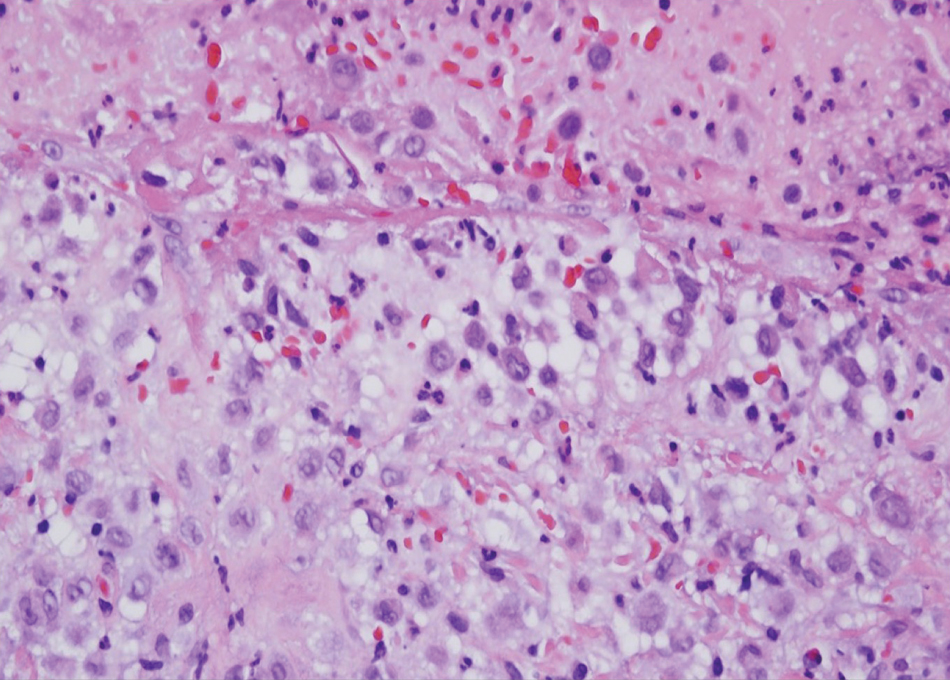

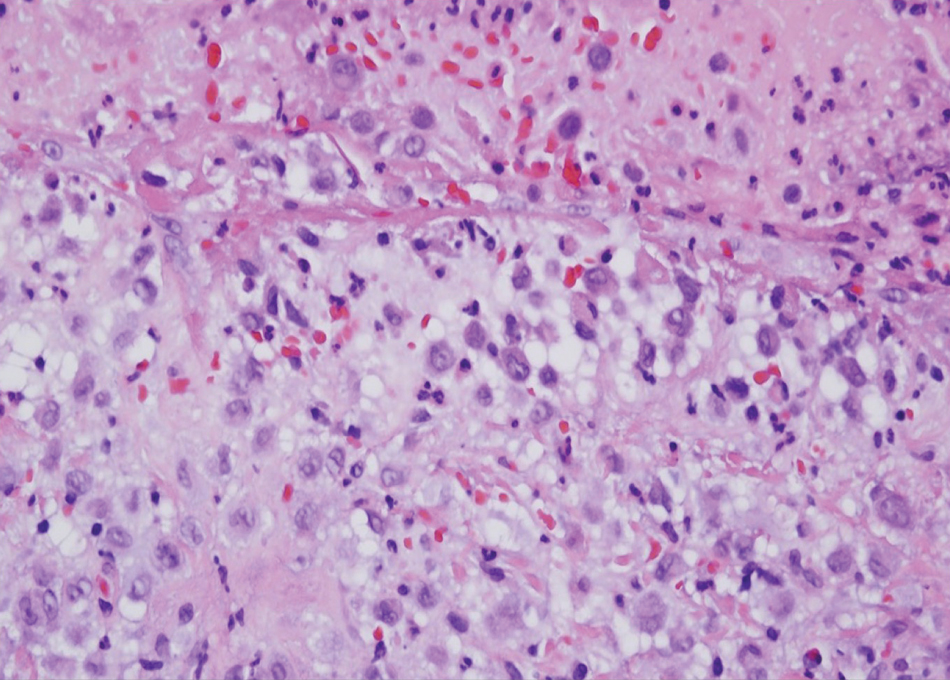

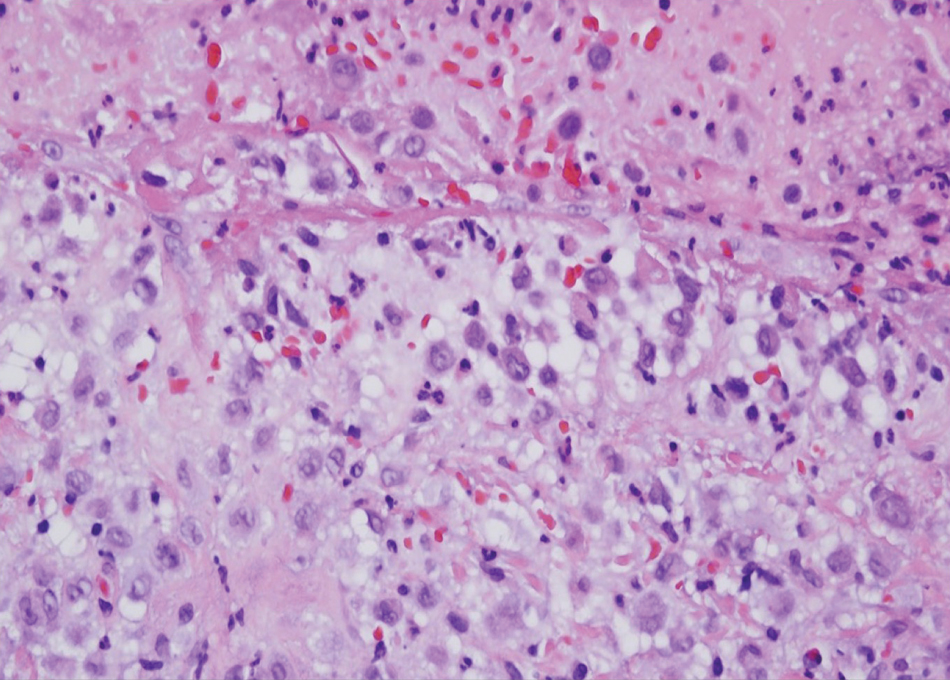

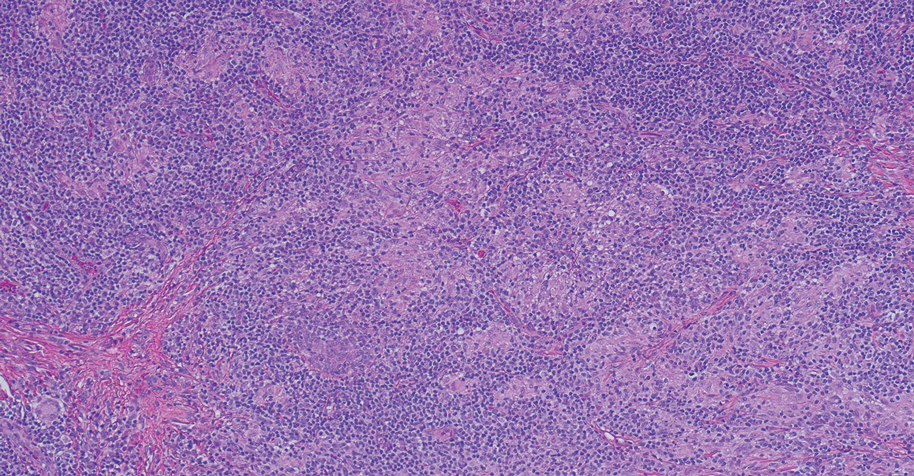

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

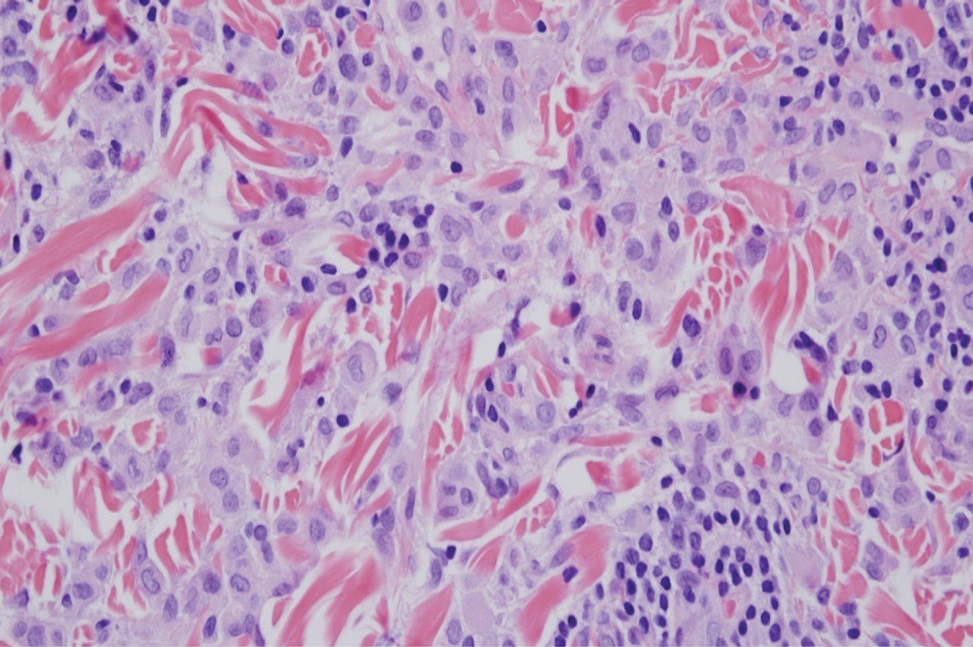

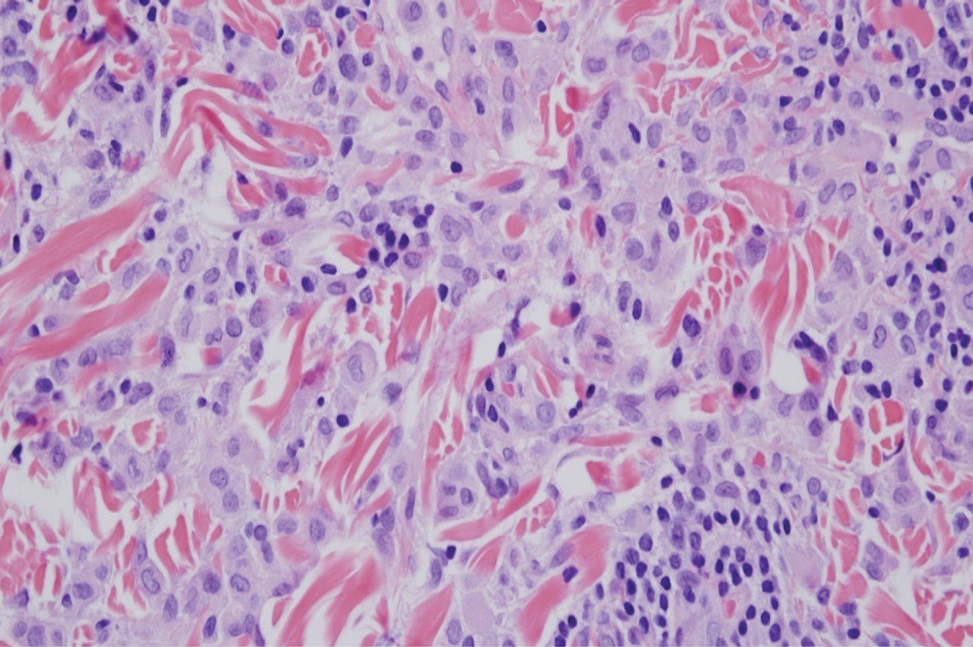

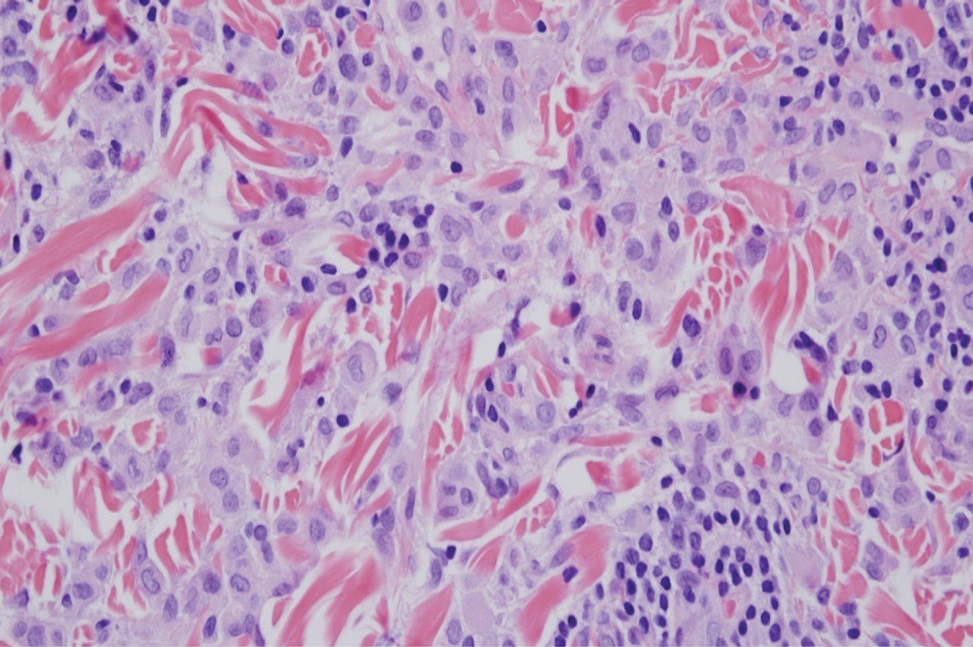

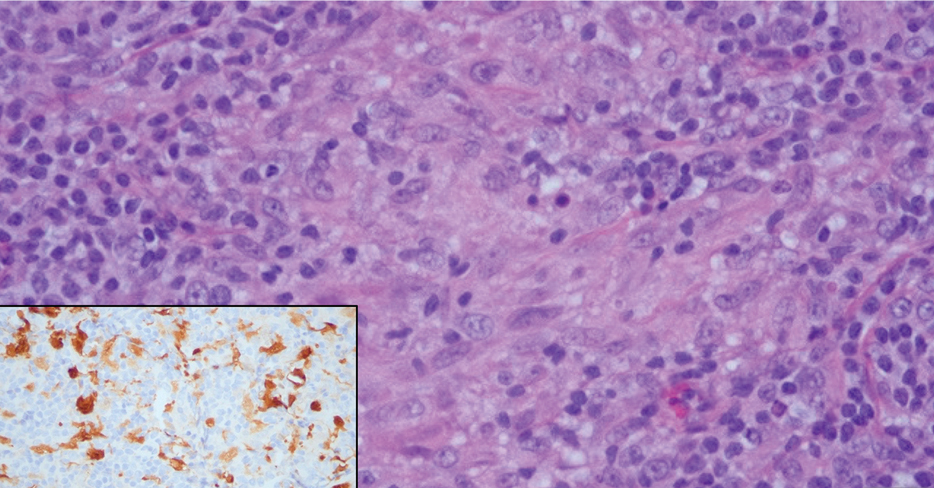

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

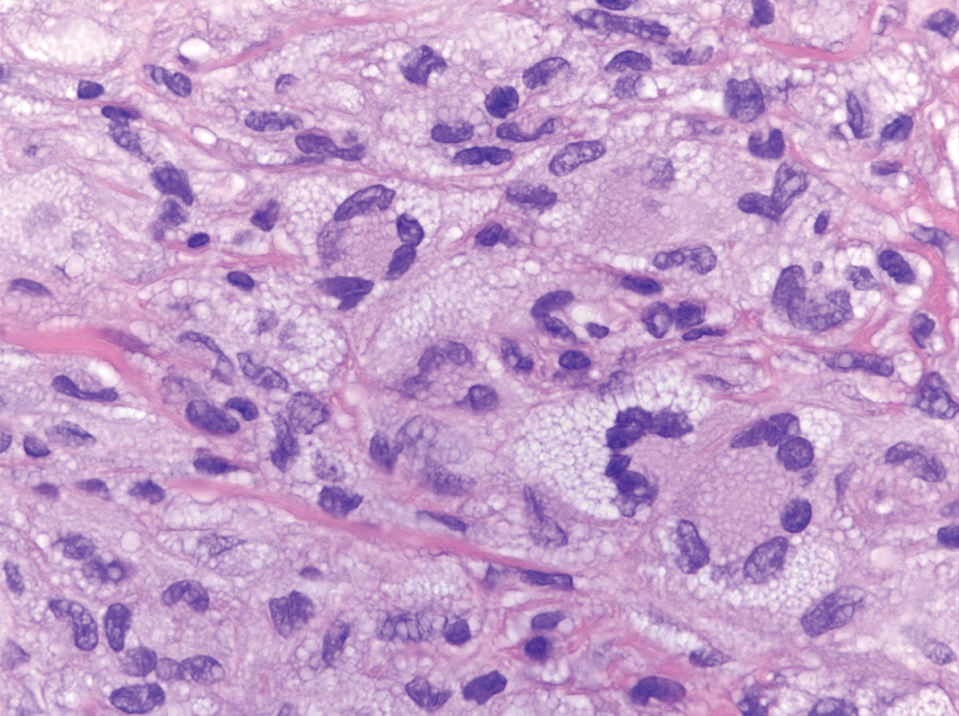

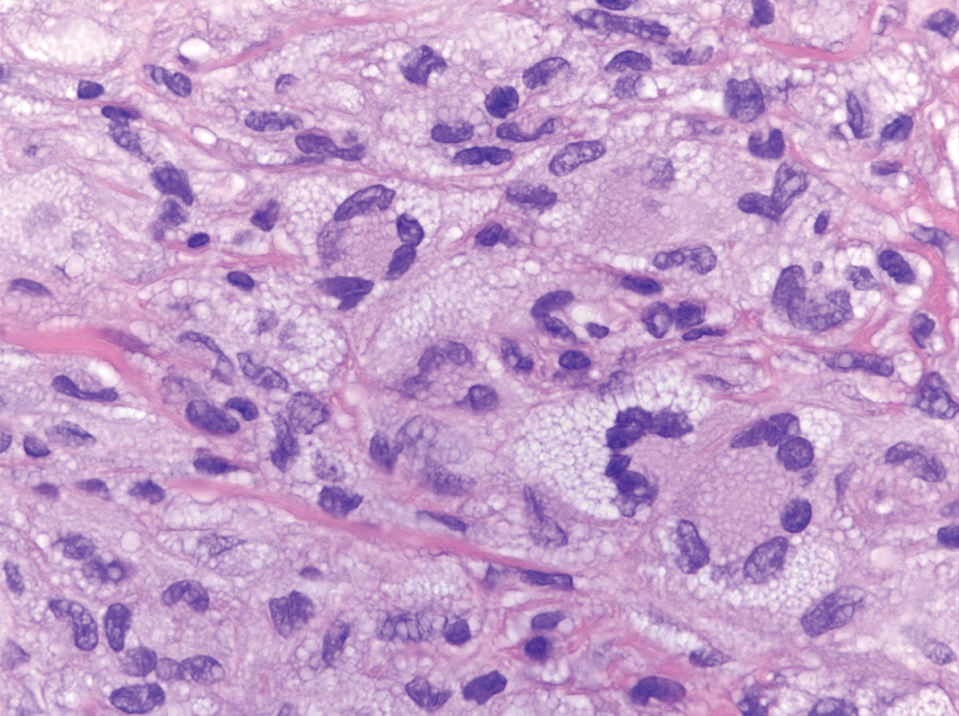

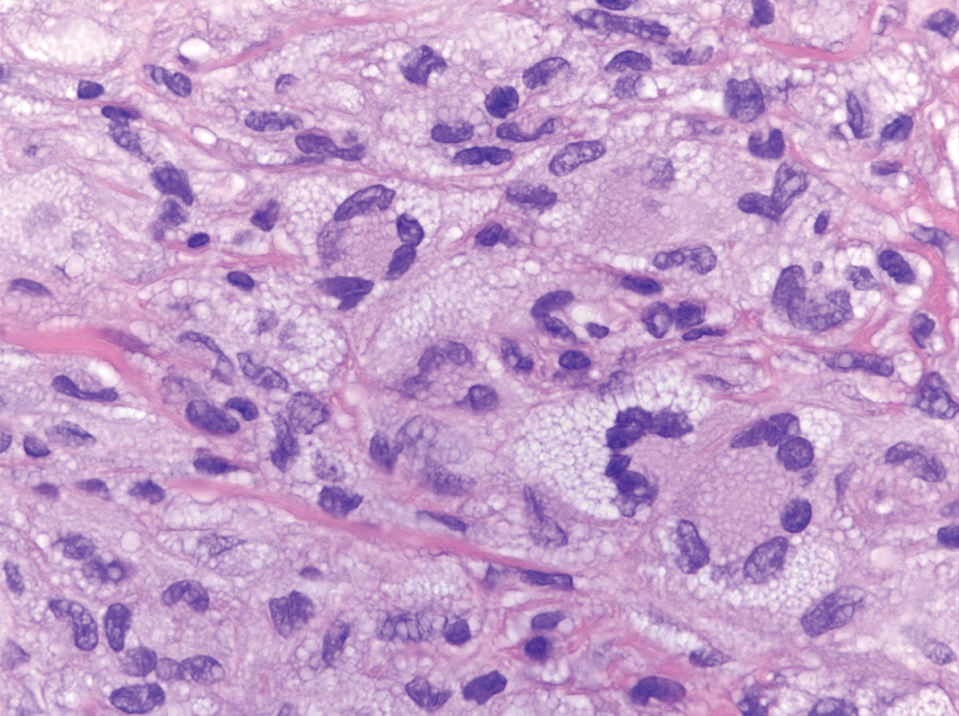

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

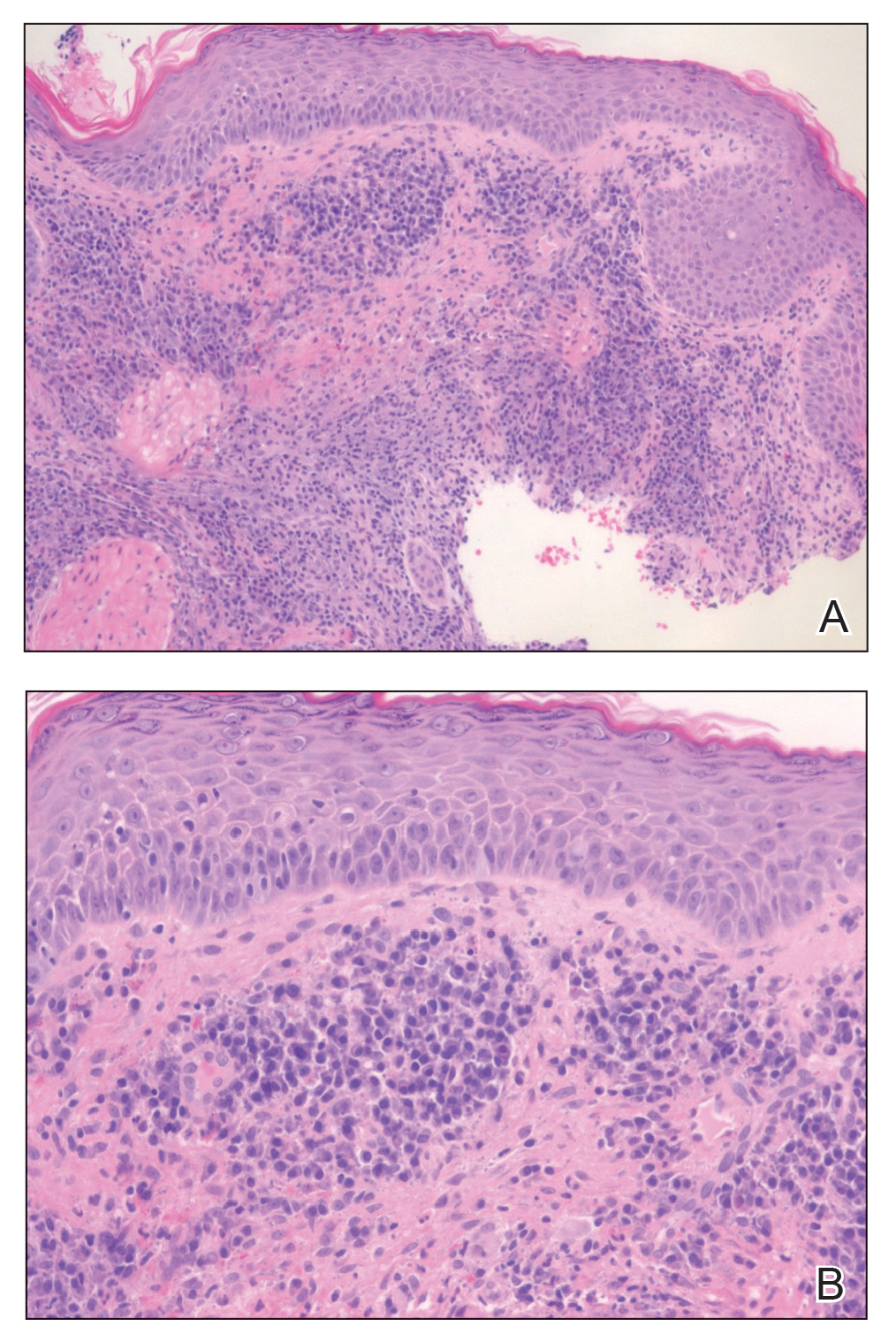

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

A 31-year-old woman presented with a slow-growing, tender, pruritic lesion on the right cheek of 4 to 5 months’ duration. She had been applying petroleum jelly and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% without any improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1×5-mm, pearly pink, erythematous, crusted papule with arborizing vessels surrounded by scattered pink papules with white dots within. No cervical lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination, and the patient denied any other systemic symptoms. Shave and punch biopsies of the lesion were performed; stains for microorganisms were negative. The biopsy showed a dense reticular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of a mixture of histiocytes (top), lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells that assumed a diffuse growth pattern within the dermis. The histiocytes exhibited abundant watery cytoplasms with ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes; intact leukocytes were found within the cytoplasms. The histiocytes demonstrated a unique phenotype characterized by S-100 (bottom) and CD68 positivity.

Nonhealing Ulcer in a Patient With Crohn Disease

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

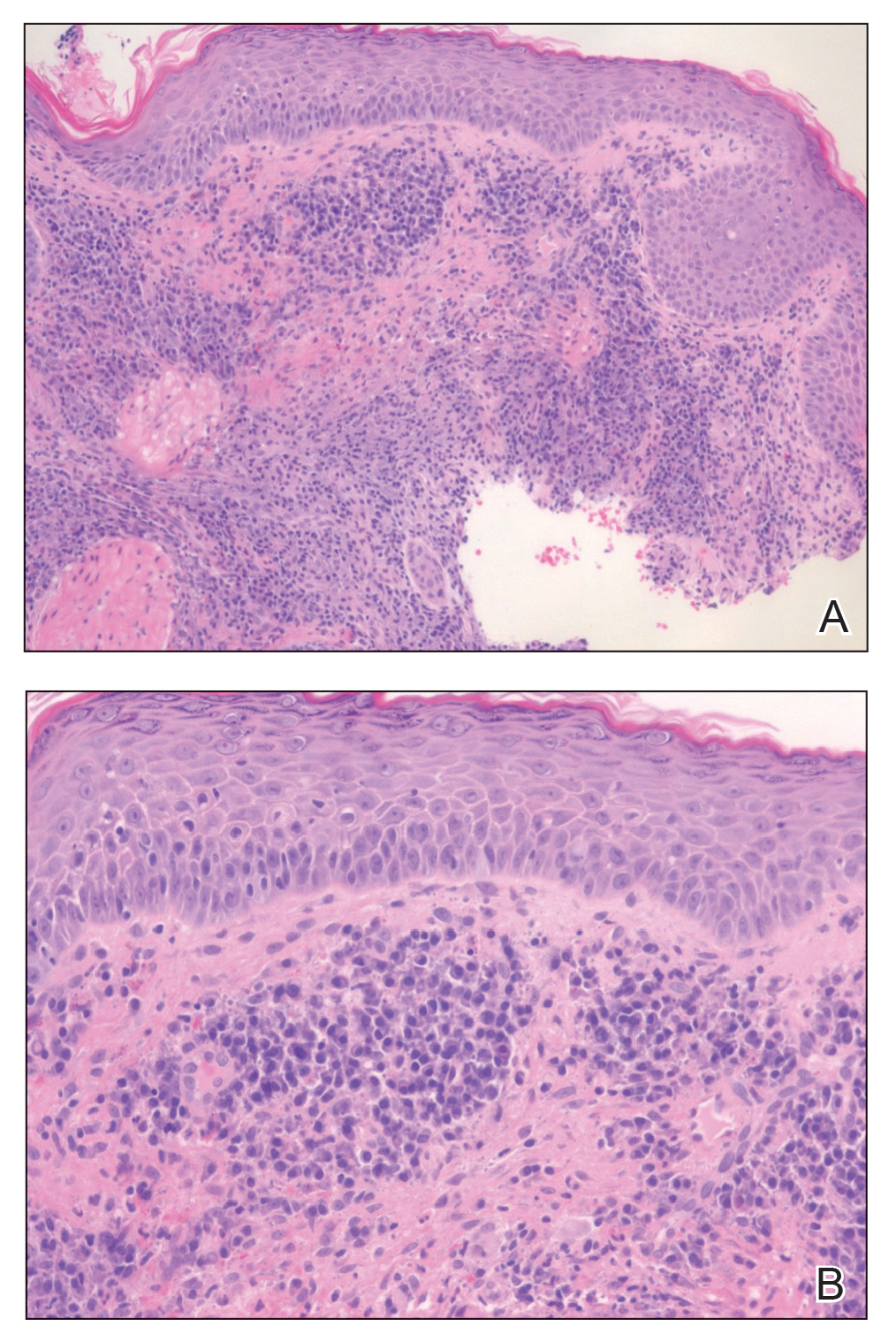

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

A 24-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful lesion on the right buccal cheek of 4 months’ duration that had not changed in size or appearance. He had a history of Crohn disease that was being treated with 6-mercaptopurine and infliximab. He underwent jaw surgery 7 years prior for correction of an underbite, followed by subsequent surgery to remove the hardware 1 year after the initial procedure. He experienced recurring skin abscesses following the initial jaw surgery roughly once a year that were treated with bedside incision and drainage procedures in the emergency department followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole with complete resolution; however, treatment with mupirocin ointment 2%, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin did not provide symptomatic relief or resolution for the current lesion. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm ulceration with actively draining serosanguineous discharge. Two punch biopsies were performed; 48-hour bacterial and fungal cultures, as well as Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, and periodic acid–Schiff staining were negative.