User login

Melanoma In Situ Within a Port-Wine Stain

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

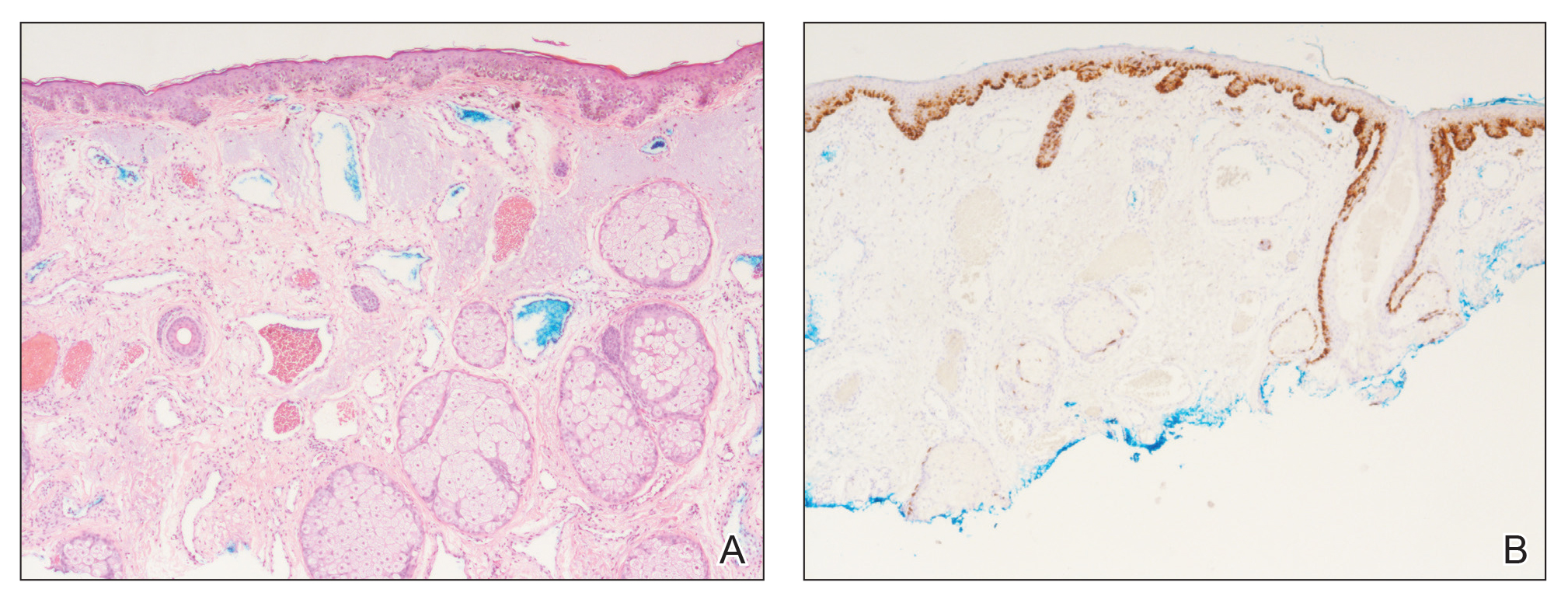

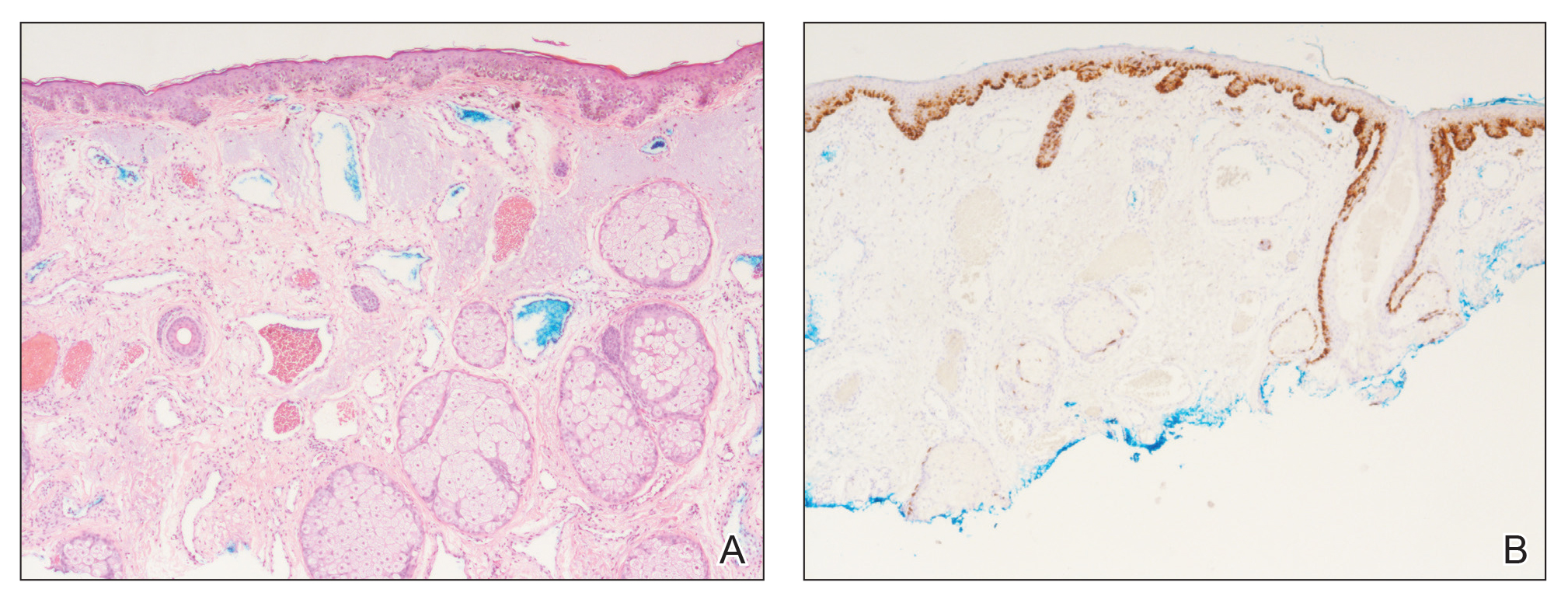

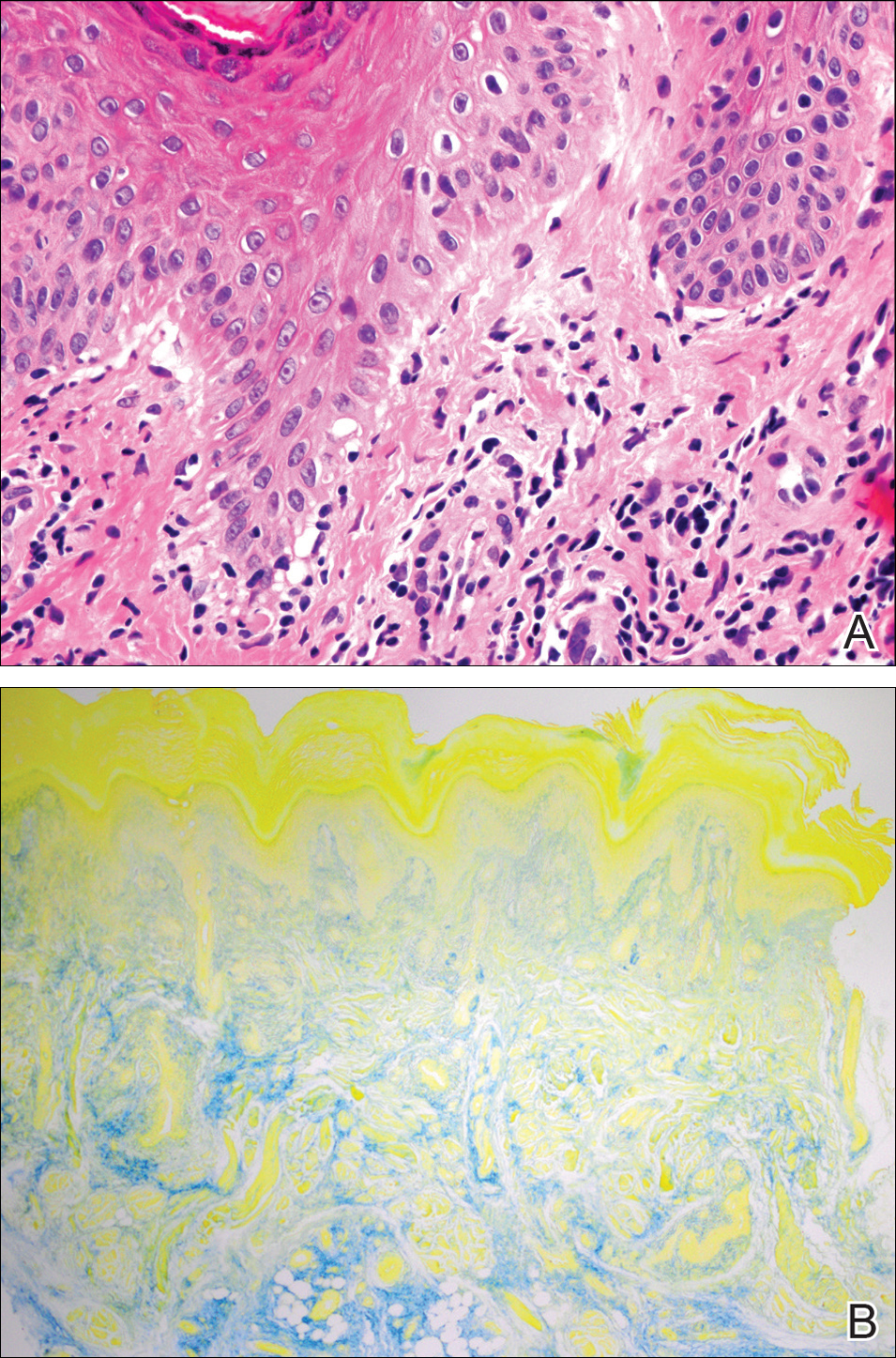

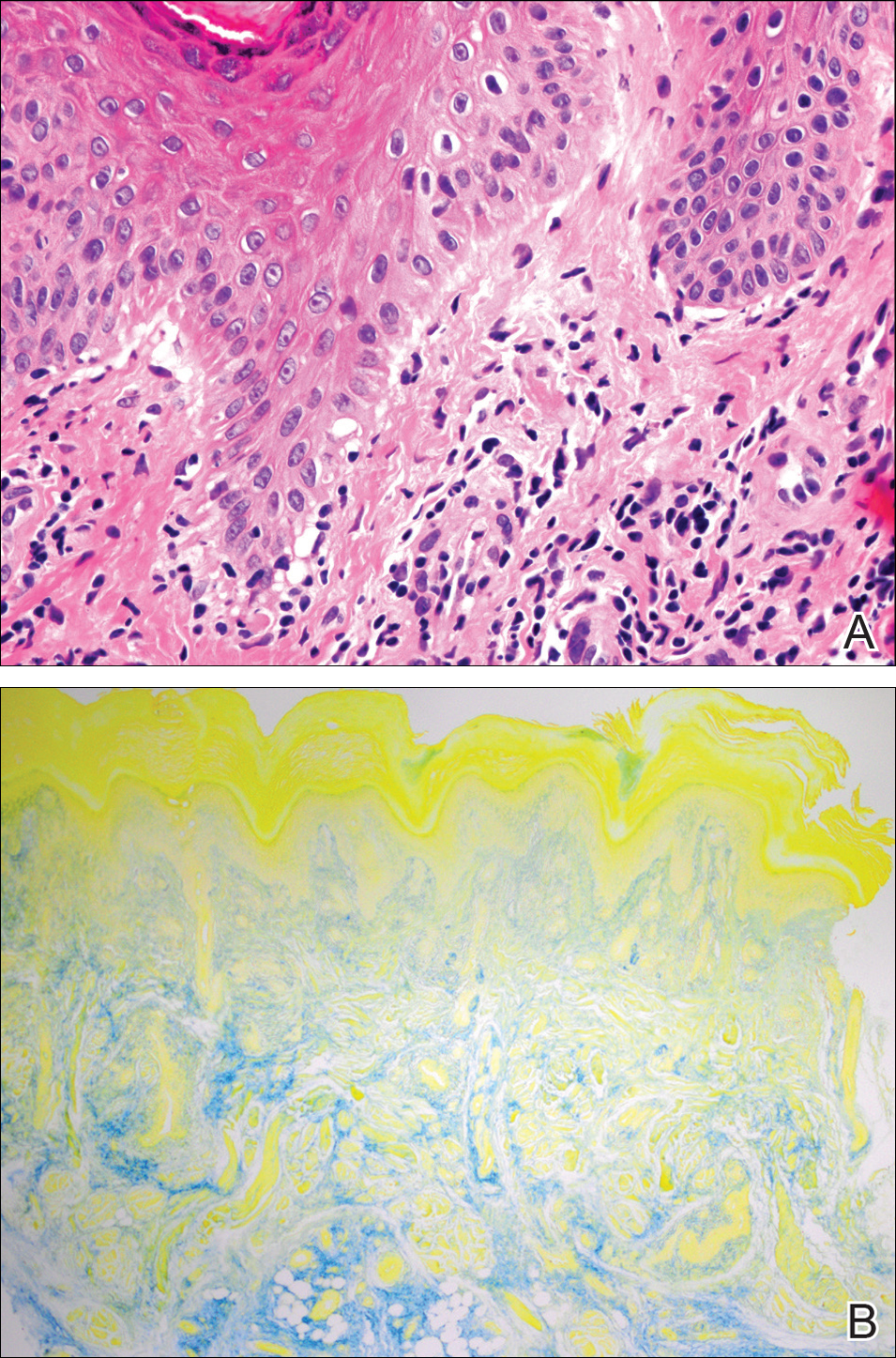

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

Practice Points

- Nonmelanoma skin cancer is known to develop in port-wine stains, most commonly basal cell carcinoma.

- The range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations can be expanded to include melanoma in situ.

- It is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations for new lesions.

Chilblain Lupus Erythematosus Presenting With Bilateral Hemorrhagic Bullae of Distal Halluces

To the Editor:

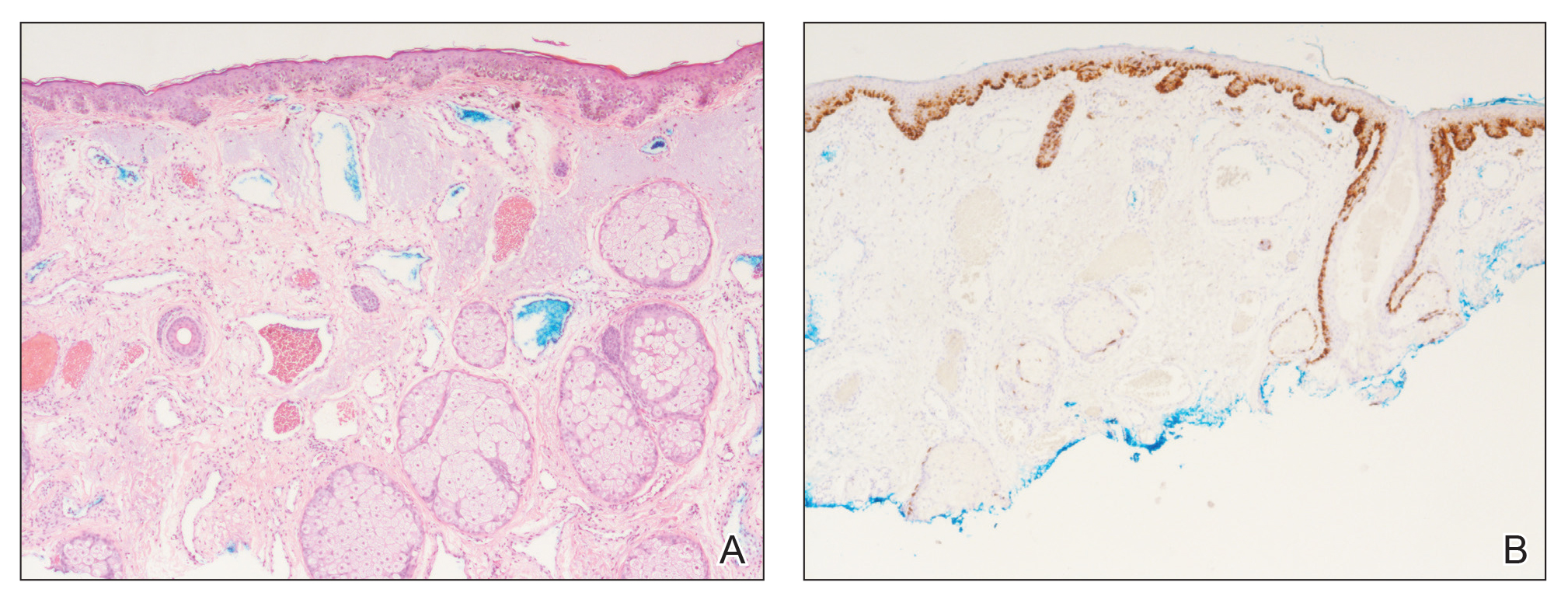

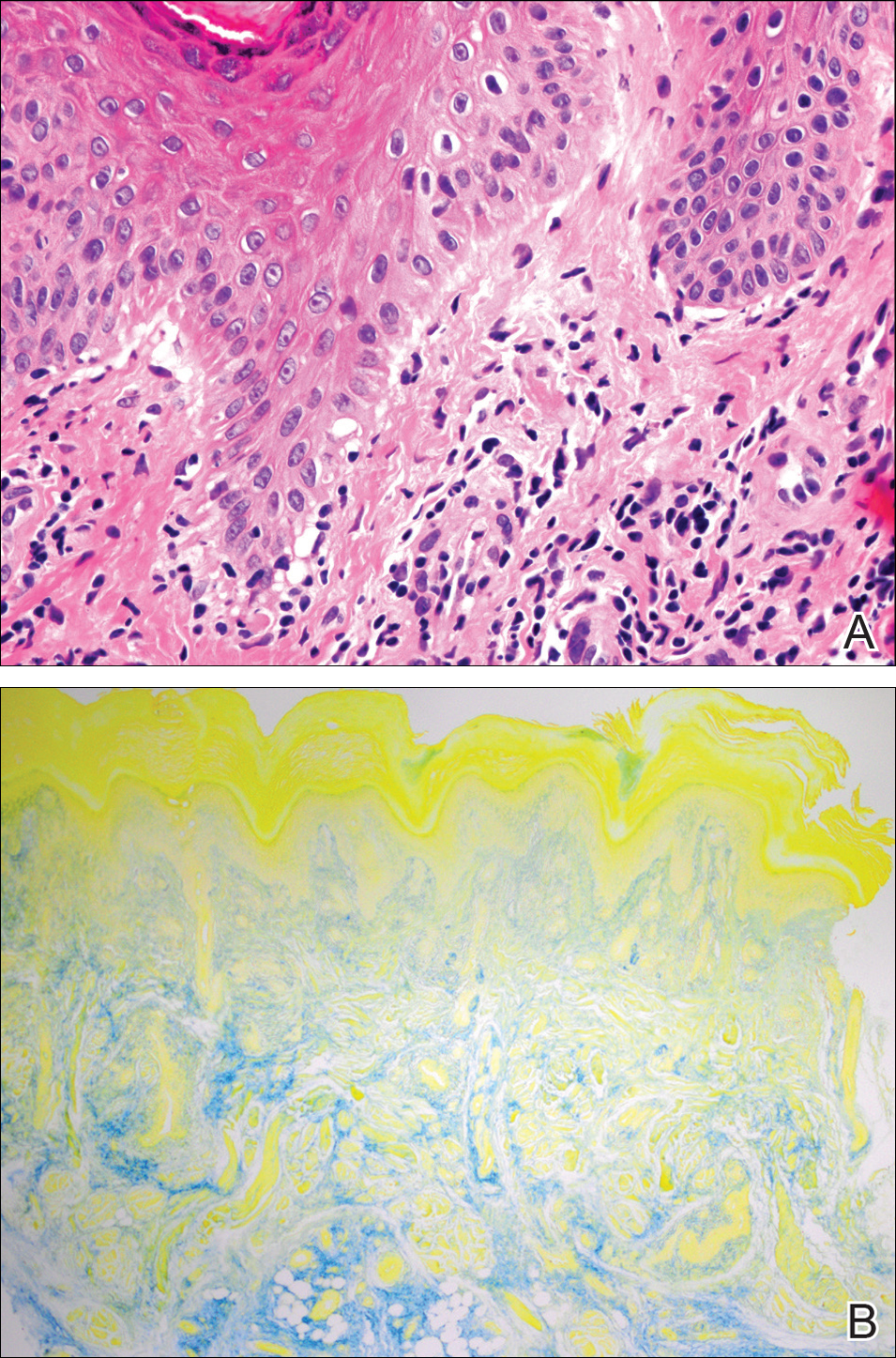

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

To the Editor:

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

To the Editor:

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

Practice Points

- Up to 20% of patients with chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) will develop systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), necessitating close long-term follow-up.

- Medications such as antihypertensives, antifungals, chemotherapeutic agents, and tumor necrosis factor 11α inhibitors have been reported to trigger CHLE.

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus is less responsive to traditional antimalarial agents commonly used to treat SLE.

- Management of CHLE includes physical protection from cold environments, calcium channel blockers, topical and systemic steroids, and pentoxifylline, among other treatment modalities.